- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

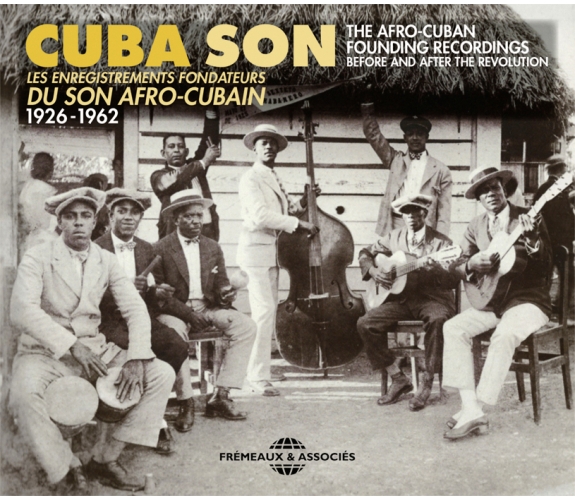

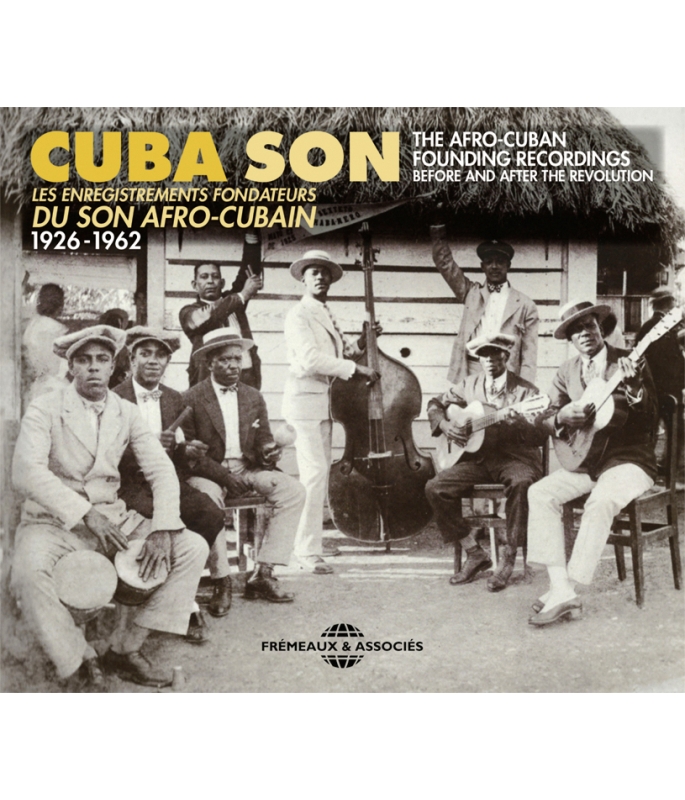

THE AFRO-CUBAN FOUNDING RECORDINGS BEFORE AND AFTER THE REVOLUTION

Ref.: FA5752

EAN : 3561302575223

Artistic Direction : BRUNO BLUM

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Total duration of the pack : 3 hours 34 minutes

Nbre. CD : 3

THE AFRO-CUBAN FOUNDING RECORDINGS BEFORE AND AFTER THE REVOLUTION

THE AFRO-CUBAN FOUNDING RECORDINGS BEFORE AND AFTER THE REVOLUTION

A mix of West African and Spanish influences, Cuban son was brought back to light by the Buenavista Social Club. However, it had gone through its original magic phase before the 1959 revolution when, like rumba, it was long repressed because it embodied Afro Cuban expression. Bruno Blum tells its story, resilience and evolution towards salsa. It was remarkably well recorded and outstanding groups such as La Sonora Matancera fusioned the fabulous son with various essential styles. A Spanish-speaking equivalent to soul music with a trance twist, it was the most popular genre on the island. Discover here some of the founding, often hard to find recordings of genuine son — Cuba’s very best. Patrick FRÉMEAUX

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Quiereme, CamagueyanaSexteto BolanaAlfredo Bolona00:03:112019

-

2Eres Mi Lira ArmoniosaSexteto HabaneroGuillermo Castillo00:03:352019

-

3El TomateroSepteto HabaneroGraciano Gomez00:03:172019

-

4Bruca ManiguaOrquesta Casino De La PlayaArsenio Rodriguez00:03:102019

-

5Sacale Brillo al Piso TeresaChano PozoArsenio Rodriguez00:02:332019

-

6Ay! NicolasConjunto CasinoAlberto Armenteros00:03:102019

-

7AdivinaloArsenio RodríguezJosé L. Forest00:03:112019

-

8No Me Llores MasArsenio RodríguezLuis Martinez Grinan00:03:202019

-

9Llevatelo TodoArsenio RodríguezLuis Martinez Grinan00:03:242019

-

10El VelorioBienvenido GrandaEscobar Ruben00:02:532019

-

11El CumbancheroCelia CruzRafael Hernandez00:02:472019

-

12Yo Canto en el LlanoDuo Los CompadresCompay Segundo00:03:042019

-

13Que Corto Es el AmorMyrta SilvaMyrta Silva00:02:532019

-

14Mentiras CriollasConjunto ChapottinFelix Chapottin00:03:012019

-

15BurundangaCelia CruzFelix Chapottin00:02:402019

-

16Alto SongoConjunto CasinoLuis Martinez Grinan00:03:072019

-

17El HuerfanitoConjunto Tipico HabaneroMiguel Matamoros00:02:442019

-

18Galan GalanConjunto Tipico HabaneroCastillo00:02:432019

-

19Elena la CumbancheraSexteto Tipico HabaneroGerardo Martinez00:02:502019

-

20Echale SalsitaIgnacio PiñeiroIgnacio Pineiro00:04:012019

-

21Esas No Son CubanosIgnacio PiñeiroIgnacio Pineiro00:03:242019

-

22Caramelo a KiloCelia CruzRoberto Puentes00:02:422019

-

23Ella y YoMaria Teresa VeraOscar Hernandez00:02:422019

-

24Que Es el AmorBienvenido GrandaSeverino Ramos00:02:512019

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Nuevo Ritmo OmelenkoCelia CruzEduardo Angulo00:03:022019

-

2BailarasBienvenido GrandaJesus Martinez Leonard00:02:592019

-

3Cancaneito CanLaito SuredaGaston Palmer00:02:542019

-

4Juancito TrucupeyCelia CruzLuis Kalaff00:02:432019

-

5Mama, Son de la LomaTrío MatamorosMiguel Matamoros00:03:382019

-

6Mi SoncitoCelia CruzIsabel Valdes00:02:412019

-

7SandungueateCelia CruzSenen Suarez00:02:422019

-

8El Manisero (The Peanut Vendor)Abelardo BarrosoMoises Simons00:03:092019

-

9Canta la VueltabajeraIgnacio PiñeiroIgnacio Pineiro00:04:222019

-

10Sixto el CarameleroNelson PinedoHumberto Juama00:02:462019

-

11Saca la LenguaOrquesta SublimeJulia Perez00:02:432019

-

12Gueita CaimanFantasmitaJuan Zayas Lastra00:02:322019

-

13La QuijaConjunto CasinoJorge Zamora00:03:112019

-

14FelicidadesJoe ValleNoro Morales00:02:502019

-

15Que No Muera el SonConjunto MarquettiJose Marquetti00:02:392019

-

16Por Que Me Siento CubanoConjunto MarquettiOdrezia Madrazo00:02:452019

-

17Goza Mi Son MontunoConjunto CasinoMiguel Roman00:02:512019

-

18Mulata LindaOrquesta Rey Diaz CalvetRamon Cabrera00:03:132019

-

19San LuiseraGrupo Campay SegundoManuel Proveda00:02:472019

-

20Voy Pa' MayariGrupo Campay SegundoCompay Segundo00:03:062019

-

21Aprietala en el RinconConjunto MarquettiWalfrido Guevara00:02:492019

-

22Eso Se HinchaBienvenido GrandaPablo Cairo00:02:542019

-

23Echale GrasaOrquesta NovedadesAgustin Ribot00:02:432019

-

24Mentiras CriollasChapottin Y Sus EstrellasFelix Chapottin00:02:592019

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Amor SilvestreLos CompadresReynaldo Hierrezuelo00:03:082019

-

2Linda SobediaLos CompadresLorenzo Hierrezuelo00:02:042019

-

3Guajira GuantanameraEl Indio NaboriJose Orta Ruiz00:03:222019

-

4El Diablo Tun TunMiguelito CuniBienvenido Julian Gutierrez00:02:462019

-

5Nico CadenonChapottin Y Sus EstrellasFelix Chapottin00:03:022019

-

6Mariquitas y ChicharronesChapottin Y Sus EstrellasFelix Chapottin00:02:512019

-

7SoneroCheo MarquettiAgustin Ribot00:02:552019

-

8El CongoCelia CruzCalixto Gallava00:02:342019

-

9Ven BernabeCelia CruzLara Agustin00:02:522019

-

10Pescadores de CamaronPío LeyvaJuan Arrondo00:02:542019

-

11Resurge el OmelenkoCelia CruzJavier Vasquez00:02:492019

-

12A Comer ChicharronPío LeyvaAngel Romero00:03:132019

-

13El Pio MentirosoPío LeyvaWilfredo Pascual00:03:072019

-

14A la Loma de BelenSepteto Cubano de Ayer y de HoyBienvenido Julian Gutierrez00:02:302019

-

15Carinoso Si Mentiroso NoPío LeyvaWilfredo Pascual00:03:042019

-

16La MalangaRoberto EspiRosendo Rosell00:03:012019

-

17Juntitos Tu y YoCelia CruzFelo Bergaza00:02:442019

-

18Dime Adios CarmelinaPío LeyvaInconnu00:02:222019

-

19Oye Como SuenaPío LeyvaPio Leyva00:02:132019

-

20La Botijuela de JuanConjunto Sones de OrienteMartin Valiente00:02:152019

-

21Mayeya No Juegues Con los SantosIgnacio PiñeiroIgnacio Pineiro00:02:592019

-

22SuavecitoIgnacio PiñeiroIgnacio Pineiro00:04:102019

-

23Me Gusta Mas el SonBeny MoreEnrique Benitez00:03:032019

-

24Tres Lindas CubanasCachao y su ComboAntonio Maria Romeu00:04:302019

FA5752 Cuba Son

Cuba SON

LES enregistrements fondateurs

du son AFRO-cubain

1926-1962

The Afro-Cuban founding recordings

Before and after the Revolution

Cuba - Son 1926-1962

Son, Son Afro, Son Habanero, Son Montuno, Montuno Chá, Montuno Afro, Capricho Son, Guajira Son, Guaracha Son, Pregón Son, Bolero Son, Son Maracaibo, Montuno Pachanga, Omelenko, Descarga

par Bruno Blum

Distinct du son mexicain bien différent, le son cubain est dérivé du changüí, un style créé vers 1860 lors de fêtes paysannes dans l’est de l’île, les cumbanchas (écouter El Cumbanchero et Elena la Cumbanchera, qui en évoquent les participants). Les musiciens de changüí étaient d’origine bantoue et utilisaient un tres (guitare à trois cordes doublées à l’octave, soit six cordes), une marimbula (lamellophone, sanza ou kalimba, que l’on retrouve dans le mento jamaïcain sous le nom de rumba box), des maracas et un güiro (rape à légumes en métal frotté avec une baguette, que l’on retrouve dans le merengue de République Dominicaine). Le son est apparu dans ce qui fut l’une des six régions de l’île, l’Oriente montagneux, situé à l’extrême est, pas loin des côtes de Jamaïque et de Haïti. Mais comme pour le blues du delta du Mississippi et le mento jamaïcain analogues, on ne retrouve pas véritablement de trace du son avant la fin du XIXe siècle.

Le son est à l’origine de différentes danses cubaines et de la salsa, qui en est dérivée. La salsa est née à New York dans les années 1960 en mélangeant différents styles nés d’une part à Cuba, et d’autre part sur l’île hispanophone de Porto Rico dont les musiques locales se mélangeaient souvent aux musiques cubaines. En évoluant plusieurs types de son sont nés, notamment le son montuno, où la frénésie s’empare souvent de l’orchestre à la fin de la chanson et où, comme dans le passage final jaleo du merengue dominicain, les improvisations, les chants en appel-réponse et les phrases répétitives d’instruments à vent deviennent obsédantes, comme pour inciter à la transe (écouter Sandungueate). Le son est une musique dont les tambours hérités des rites animistes de la santería étaient joués par des Afro-cubains mélangés à des Blancs et des métis.

Le son, musique noire interdite

Le son s’est développé dans les années qui ont suivi l’abolition de l’esclavage (1886) à l’est de Cuba (vers Santiago). C’est là que les forces luttant pour l’indépendance du pays avaient rapproché de grandes familles blanches de planteurs, des mulâtres et des esclaves émancipés et libérés. Dans ces montagnes de la Sierra Maestra se cachaient aussi les esclaves enfuis, les cimarrones, terme signifiant « bétail » (nèg’ marrons en créole français). Un réseau de familles rurales et urbaines se réunissait et faisait la fête en jouant du son, un genre fusionnant des éléments afro-hispaniques. Le son est ainsi apparu dans ce contexte indépendantiste particulier : après les deux guerres d’indépendance contre l’Espagne et avant la guerre d’indépendance finale, où les États-Unis sont intervenus et ont occupé l’île (1901) avant de la coloniser et de la contrôler jusqu’à la révolution communiste de 1959.

C’est en 1909 que, apporté de l’autre bout de l’île par des militaires, le son a laissé une première trace à La Havane. Il était jusque-là pratiquement clandestin car lié à l’état d’esprit de la lutte pour l’abolition de l’esclavage, puis de l’intégration et de la libération du joug colonial. Il était bien différent des traditions musicales coloniales, où toute influence africaine était méprisée. Pourtant la tradition espagnole formait nombre de musiciens afro-cubains, qui interprétaient à merveille le danzón comme le boléro très marqués par l’Espagne. Soutenu par les intellectuels, dans les années 1920 le son était associé à l’expression populaire cubaine, à la contestation étudiante contre la politique de droite, contre la ségrégation raciale, le racisme institutionnel et le colonialisme états-unien1.

Le son est une musique créole, c’est à dire une fusion entre des traditions musicales espagnoles (la chanson ou canción, les gammes andalouses, les mélodies et la langue) et africaines (mélodies, rythmes, percussions et langues dont un sabir et un pidgin). On y retrouve des éléments de guitare, de mélodies et de poésie espagnole (écouter la contribution du célèbre poète El Indio Naborí) accompagnés par des rythmes spécifiques. Après une longue domination du style danzón institutionnel dérivé de la contradanza habana (elle-même dérivée du quadrille/contredanse français hérité des country dance d’Angleterre), des petites formations appelées charangas ont dépoussiéré les orchestres de danzón à la fin du XIXe siècle. Les nouveaux charangas utilisaient le plus souvent un violon, une flûte à cinq trous en ébène, parfois un piano et toujours des percussions. Elles empruntaient des mélodies à la musique classique, au danzón, à l’opérette, aux chansons de théâtre (zarzuelas), aux chansons populaires et mélangeaient un peu tout. Comme les orchestres de danzón, les charangas étaient dominés par des musiciens afro-cubains éduqués à la musique selon une longue tradition cubaine en cours bien avant l’abolition tardive de l’esclavage. Ils restaient dans la tradition de la bonne société et renouvelaient simplement le danzón.

Les disques Victor ont fait connaître de premières musiques locales en réalisant des enregistrements de terrain avec du matériel portatif. Ils ont initialement gravé des disques de danzón, de puntó guajiro, d’artistes de théâtre, de troubadours et d’artistes lyriques, une direction artistique assez conservatrice. Musique populaire créole, comme le blues sur le continent le son était méprisé par les élites du pays et comme le blues, il n’a pas été enregistré à Cuba avant les années 19202 (jazz et blues : respectivement 1917 et 1920 à New York).

La libération du son

Alors que les rites afro-cubains, leurs chants, leurs tambours, leurs transes et leurs esprits, les orishas, étaient célébrés dans toute l’île et soutenus par les intellectuels de gauche, la popularité grandissante du son, une musique plus rythmée, en phase avec l’héritage africain (percussions de rites de la santería), a fait un bond avec l’élection le 20 mai 1925 du président Gerardo Machado qui est resté au pouvoir jusqu’en août 1933. D’origine modeste, Machado appréciait le son et l’a plus ou moins soutenu bien que son administration ait réprimé les tambours afro-cubains — et commis un grand nombre de meurtres contre contestataires et opposants.

Les congas, tambours et danses libres ont été interdits au carnaval de Santiago dès juillet 1925 mais, le 23 mai 1925, trois jours après son élection, le premier concours national de son a été autorisé et gagné par le Sexteto Habanero qui devint vite le groupe le plus populaire de l’île avec son joueur de tres. C’est avec ce sextuor dirigé par le contrebassiste et chanteur Gerardo Martínez que sont apparus les premiers succès tangibles du disque à Cuba comme Eres Mi Lira Harmoniosa. Avec ses voix harmonisées, comme celles accompagnant la grande vedette Abelardo Barroso, le son était chaud et irrésistible. D’autres formations comme le Sexteto Boloña et le Trío Matamoros ont participé à populariser ce style de son, bien différent de celui des orchestres à venir.

L’un des rythmes caractéristiques du son est joué au tibois (deux bâtonnets de bois frappés l’un contre l’autre, clave en espagnol). On le retrouve dans la biguine martiniquaise et guadeloupéenne comme dans le mento jamaïcain (ce qui suggère une source africaine commune ou une influence du son sur le reste des Caraïbes, ou l’inverse) ou encore « limbo » (un style de la Trinité) joué à la guitare rythmique par l’influent Bo Diddley à Chicago. Ce rythme était présent dès Quiereme, Camagueyana en 1926.

Ce style décontracté contrastait avec le danzón hispano-cubain, bien plus formel et heurté. Le 21 mars 1927, le Sexteto Habanero a été rejoint par Enrique Hernández au cornet, qui fut remplacé par le légendaire trompettiste Félix Chapottín jusqu’en février 1928. Le Septeto Habanero était né et avec son instrument de cuivre (écouter El Tomatero) il devint aussi moderne que le jazz de la proche Nouvelle-Orléans, où le soliste était également un nouveau phémomène. D’autres charangas avec trompette sont apparus, comme le Sexteto puis Septeto Nacional d’Ignacio Piñeiro.

Piñeiro était un Abakuá (incarnation cubaine d’une société secrète née au Calabar, dans l’est du Nigeria actuel : voir Cuba - Santería 1939-1962 dans cette collection). Il connaissait les traditions afro-cubaines. Son orchestre fut très longtemps l’un des meilleurs. À l’est de l’île, l’Oriente, Miguel Matamoros enregistra son premier succès en 1928. Ce grand parolier et compositeur alliait le style son avec la tradition des troubadours (la trova, également représentée ici par El Indio Naborí et Los Compadres avec et sans Compay Segundo, futur vedette du Buenavista Social Club), qui contrastait avec les orchestres « conjuntos » plus cossus. Matamoros sophistiqua le son avec son jeu de guitare punteado (finger picking avec la corde grave jouée par le pouce) et des harmonies vocales raffinées. Il connut un succès international avec son Trío Matamoros. Son célèbre Mamá, Son de la Loma (ici dans une version de 1955) chante que le son est venu des montagnes de l’Oriente à la plaine, jusqu’à la capitale. Comme tous les musiciens de son, il était très marqué par la rumba.

Le danzón était populaire dans les clubs privés, les sociedades où différentes communautés de la société cubaine se retrouvaient. À Cuba les membres se définissaient par leur appartenance ethnique, professionnelle et leur niveau de revenus. Les clubs noirs eux-mêmes rejetaient le son mais la popularité du Septeto Habanero et du Trío Matamoros a ouvert la voie jusque dans les sociedades les plus huppées. Dans de nombreuses soirées privées alcoolisées (y compris celles offertes par certains membres du gouvernement et par le président Machado lui-même) fréquentées par des femmes vénales, dans les académies de danse, les bordels, le son venu de la société afro-cubaine correspondait mieux que le danzón à l’état d’esprit des clients venus s’encanailler. Comme le jazz le faisait aux États-Unis à la même époque, il a progressivement percé dans la société. Détesté, le président Machado cherchait à s’attirer les faveurs des Noirs tandis que sa police les réprimait cruellement. Alors que les musiciens qui osaient jouer des bongós en public continuaient à être emprisonnés, le son est devenu à la fin des années 1920 la principale forme de musique cubaine. Son succès fut aussi lié à l’essor de la radio, qui le diffusa dans tout le territoire pendant la décennie suivante. Les tambours congas (tumbao), associés aux carnavals interdits et aux Noirs des bidonvilles sont restés prohibés dans les années 1930 (sauf les « congas de salon » utilisés dans les spectacles scéniques blancs). Armés de leur seule guitare, les troubadours assuraient des heures de diffusion radio et la guitare classique était très à la mode.

Le son, musique issue du peuple, donc par nature contre la ségrégation raciale, était soutenu par les contestataires, les étudiants.

La crise économique de 1929 a très durement touché l’île, très dépendante du tourisme américain et de l’export du sucre aux États-Unis. Une première révolution a fait chuter Machado en 1933 et a mené à une année d’anarchie puis à un coup d’état du sergent Fulgencio Batista. Entre 1930 et 1936 presque rien n’a été enregistré à Cuba mais les émissions de radio CMQ diffusaient du son au ton révolutionnaire qui contrastait avec les dizaines de stations plus conventionnelles (qui diffusaient des feuilletons, de la musique classique, du danzón et sa variante radiophonique le danzonete). Puis, en 1937, la mafia américaine a mis la main sur les casinos cubains en promettant à Batista son pourcentage.

Son Montuno

En 1938, le succès du « Begin the Beguine » de Cole Porter par Artie Shaw, une biguine analogue au boléro-son cubain, contribua à populariser la musique caribéenne aux États-Unis. Le chanteur Miguelito Valdés fut l’un des premiers cubains blancs à incorporer le son, la rumba et autres rythmes afro dans un orchestre de jazz, Orquesta Casino de la Playa. La voie était ouverte : le son authentique s’est alors développé sous une nouvelle forme, celle des orchestres. Nourri de culture « congo » (son grand-père était un esclave bantou), l’Abakuá Arsenio Rodríguez était noir, aveugle, illettré, venu d’une famille pauvre de paysans de la canne à sucre qui déménagea de Güines à La Havane. Il maîtrisa le tres et se passionna pour le son, musique populaire méprisée, mais un peu moins dédaignée que l’exécrée rumba. RCA avait recommencé à enregistrer en 1937 ; les musiciens afro-cubains étaient interdits dans les grandes salles et c’est Casino de la Playa, un orchestre blanc, qui a osé graver plusieurs morceaux innovants dont Bruca Maniguá, une composition d’Arsenio Rodríguez sur un rythme rumba-son, chantant ouvertement son identité « carabali » (Calabar) « de la nation noire », l’esclavage, la violence, une complainte énoncée en langue bozal (celle des Africains nouvellement arrivés, celle de son grand-père) — une première à Cuba. Le tout sur un rythme joué au tibois. Les tambours congas n’étaient plus passibles de prison : le dictateur Batista les avait libérés et les défilés de carnaval avaient repris au son des tambours. Le compositeur et maître tambour Chano Pozo, un dur, un cireur de chaussures abakuá venu des mêmes quartiers qu’Arsenio, avait lui aussi commencé à enregistrer en petite formation. Il migra vite à New York où il enregistra avec Dizzy Gillespie mais grava auparavant des perles de son montuno comme Sacale Brillo Al Piso Teresa avec le tres caractéristique du son authentique. Les arpèges de piano typiques de la musique cubaine faisaient surface, imitant la partie de tres du son, elle-même héritée de la sanza centrafricaine (Ay! Nicolas par le Conjunto Casino).

Le légendaire Arsenio, premier maître du son montuno interprété par une formation conjunto (orchestre cubain), bouleversa la musique du pays en 1949. Après le départ d’Arsenio aux États-Unis en 1952 son groupe devint celui du trompettiste émérite Félix Chapottín.

L’Âge d’Or du Son

Le tourisme états-unien était présent à Cuba avant la Deuxième Guerre Mondiale. Mais après 1945, le niveau de vie sur le continent a connu une accélération et les touristes affluèrent à Cuba, qui était présenté comme un terrain de jeux ensoleillé et attrayant où les casinos, les hôtels, les cabarets, les lieux de spectacles musicaux, les filles — et l’alcool — abondaient. Parallèlement aux troubadours, les orchestres « conjunto » de dimensions respectables avec tres, trompettes, piano, percussions et chœurs fleurissaient : Conjunto Tipico Habanero, Conjunto Casino, Septeto Nacional d’Ignacio Piñeiro, Conjunto Marquetti. De grandes formations comme celle de Beny Moré, Orquesta Sublime, Orquesta Rey Diaz Calvet, Chapottín y sus Estrellas, Orquesta Kubavana, Orquesta Sabor de Cuba et bien d’autres atteignaient des sommets — ce fut le grand âge d’or de la musique cubaine, où le son régnait.

RCA Victor et Columbia avaient jusque-là été les seuls à enregistrer la musique cubaine. Les enregistrements cubains d’après-guerre ont été dominés par la marque indépendante Panart de Ramón Sabat, fondée en 1943, qui a ouvert un studio à La Havane : plus besoin de matériel portatif ni de louer le studio de la station de radio. D’autres sociétés de production de disques sont venues concurrencer le succès de Panart dans les années 1950, parmi lesquelles Kubaney, Puchito, Velvet, Fama, Maype, Gema, Suaritos, et toujours RCA qui fonda sa marque locale Discuba in 1959. Le groupe vedette de Panart, La Sonora Matancera, a engagé les meilleurs chanteurs, Bienvenido Granda puis l’excellente Myrta Silva, remplacée en 1950 par Celia Cruz, la future « reine de la salsa » qui brilla aussitôt avec de grands succès comme Burundanga en 1954. Leur style ouvertement noir, le son montuno (« le son des montagnes »), symbole d’authenticité locale afro régnait dans les orchestres de Cuba tandis que le mambo, puis le cha cha chá trouvaient le succès à l’étranger où ils étaient copiés partout, par des orchestres professionnels comme celui de Xavier Cugat ou Tito Puente. Des styles cubains proches, rumba, pregón, afro, guaracha, guajira, mambo, bolero, pachanga etc. se mêlèrent souvent dans les orchestres de son. Après la version américaine à succès de El Manisero (« The Peanut Vendor ») par Don Azpiazú en 1930, l’impact de la musique cubaine aux États-Unis et dans le monde fut significatif. Il est documenté dans un autre volume de cette série3. Quelques exemples : Ignacio Piñeiro rencontra George Gerschwin en 1932 ; l’Américain lui emprunta une partie de Echale Salsita (où l’on trouve la première mention du mot « salsa » dans un morceau cubain) pour sa « Cuban Overture » ; El Cumbanchero devint un classique du reggae jamaïcain, « Rockfort Rock » ; et la partie de basse du montuno pachanga Pescadores de Camaron du Conjunto Marquetti est identique à celle du célèbre Natural Mystic de Bob Marley & the Wailers.

L’île dépendait presque à 100 % de l’exportation de son sucre vers les États-Unis. Mais les revenus de la canne à sucre ne profitaient pas au peuple ; presque tout était importé, y compris des marchandises qui étaient déjà produites à Cuba et souffraient de concurrence déloyale. Les prix de ces produits étaient très élevés pour une population démunie qui avait rarement accès aux orchestres luxuriants, d’une qualité inouïe. Rien n’était investi dans l’éducation, l’agriculture et les infrastructures, ce qui motiva bientôt une révolution. Fidel Castro et ses hommes arrivèrent à La Havane le 31 décembre 1958. La nationalisation complète de l’industrie musicale prit place le 29 mai 1961, provoquant l’exode de nombreux musiciens, dont Celia Cruz, et de producteurs comme Sabat. La musique cubaine n’a plus jamais été la même depuis.

Bruno Blum, janvier 2019

Merci à Crocodisc, Patrick Dalmace (www.montunocubano.com), Franck Jacques, Bernard Loupias et Pascal Olivese.

© Frémeaux & Associés 2019

1. Ned Sublette, Cuba and its Music, From the First Drums to the Mambo (Chicago Review Press, 2004).

2. Maya Roy, Cuban Music (Latin American Bureau, Londres, 2002).

3. Lire le livret et écouter Cuba in America 1939-1962 dans cette collection.

Cuba - Son 1926-1962

Son, Son Montuno, Montuno Chá, Montuno Afro, Montuno Pachanga, Capricho Son, Guajira Son, Guaracha Son, Pregón Son, Bolero Son, Son Maracaibo, Omelenko, Descarga

by Bruno Blum

Not to be confused with Mexican son, which is quite different, Cuban son is derived from changüí, a style created around 1860 in eastern Cuba at countryside parties called cumbanchas (its participants are mentioned here in El Cumbanchero and Elena la Cumbanchera). Changüí musicians were of Bantu origin. They used a tres (a three string guitar, each string being doubled with high string at the octave, making it a six-string guitar), a marimbula (sanza or kalimba, also found in Jamaican mento under the name rumba box), maracas and güiro (a metal vegetable grater scraped with a stick, also found in Dominican Republic merengue).

Son first appeared in what once was one of the six regions on the island, the mountainous Oriente at the far east end, not so far from the shores of Jamaica and Haiti. But as for the similar Mississippi delta blues and Jamaican mento, no trace of the son was found until the end of the 19th century.

Son is at the root of various Cuban dances and salsa, which is derived from it. Salsa was born in New York in the 1960s by mixing different styles from Cuba, on the one hand, and from the Spanish-speaking island of Puerto Rico, where local music often merged with Cuban music, on the other hand.

As Son grew, several different types appeared, most notably the son montuno, where a kind of frenzy often takes over at the end of the song and where, pretty much like in Dominican merengue’s final part, called jaleo, call-and-response chants and repetitive wind instrument riffs get obsessive, as if to incite a trance (hear Sandungueate). Son is a music where drums derived from santería animist rituals were played by Afro-Cubans, mixed with mulattos and Whites.

Son, a forbidden Black music

Son expanded in eastern Cuba (near Santiago) in the years that followed the abolition of slavery in 1886. This was where the force struggling for the country’s independence brought together big families of White planters, mulattos and emancipated, freed slaves. In those Sierra Maestra mountains were also found runaway slaves. These were called “cimmarrones”, a term meaning ‘cattle,’ (maroons in Jamaican patois). A network of rural and urban families got together and partied to the sound of son, a genre combining African and Hispanic elements. It is in this particular, separatist context that son was born: right after two wars of independence against Spain, and before the third and final war, where the United States intervened and occupied the island (1901), then colonised and controlled it until the 1959 communist revolution.

It is in 1909 that, brought over to the other end of the island by the military, son left its first mark in Havana. It was then literally clandestine, as it was linked to the spirit of the abolition of slavery, and later of integration and freedom from colonial yoke. It was way different from colonial music traditions, in which any African influence was scorned. However, many Afro-Cuban musicians were musically educated in the Spanish tradition, and performed the Spanish-influenced danzón and bolero marvelously.

In the 1920s son was instead associated with the people’s forms of expression. These topics included students protesting against right-wing politics, racial segregation, institutional racism and U.S. colonialism. Son is a Creole music; this means a fusion between traditions from Spain (song or canción, Andalusian scales, melodies and language) and from Africa (melodies, rhythms, percussion and languages, including sabir and pidgin). One can find melodies and guitar elements as well as Spanish poetry (hear the famous poet El Indio Naborí here) backed by specific rhythms.

After a long domination of the institutional danzón style derived from the contradanza habana (itself stemming from the French quadrille/contredanse inherited from England’s country dance), small combos called charangas dusted off the style of the danzón orchestras at the end of the 19th century. The new charangas most often used violin, five-finger-hole fifes made out of ebony, sometimes a piano and percussion always. They borrowed melodies from classical music, from danzón, operetta, theater songs (zarzuelas) and popular songs, and mixed all of this together.

As with danzón orchestras, charangas were dominated by Afro-Cuban musicians who had learned music formally, following a Cuban tradition going way back, from before the belated abolition of slavery. These musicians simply reinvented danzón and remained accepted by society. Using portable equipment, the RCA Victor recording company gave local music its first break with field recordings. They cut danzón records at first, and puntó guajiro, theater artists, troubadours and classical singing, maintaining a rather conservative direction. Son was a Creole music; it was scorned by the country’s elite and, like jazz and blues, it was not recorded in Cuba until the 1920s (jazz and blues: 1917 and 1920, respectively, in New York).

The Liberation of son

Afro-Cuban rituals, with their chantings, drums, trances and spirits, the orishas, were celebrated across the island and were supported by left-wing intellectuals. The son was rhythm music in phase with the African legacy, including percussion from santería rituals. Its growing popularity suddenly changed pace on May 20, 1925, when President Gerardo Machado was elected, staying in power until August, 1933. Of humble origins, Machado appreciated son and more or less supported it, although his administration repressed Afro-Cuban drums — and had many opponents and protesters murdered.

Congas, drums and free dancing were banned from the Santiago carnival in July, 1925, but on May 23, just three days after his election, the first national son contest was permitted and won by the Sexteto Habanero, which soon became the most popular group on the island, and featured a tres player. It was with this six-piece band, conducted by double bass player and singer Gerardo Martínez, that the first truly popular records, such as Eres Mi Lira Harmoniosa, surfaced in Cuba.

With vocal harmonies, including those heard with Habanero’s big star of the day, Abelardo Barroso, the son was warm and compelling. Others, like the Sexteto Boloña and the Trío Matamoros contributed to popularizing this son style, which was different from what was to come.

One of the typical son rhythms is played on claves (two wooden blocks hit against one another). It is also found in biguine from Martinique and Guadeloupe, as well as in Jamaican mento (which suggests a common African source or an influence of the son on the rest of the Caribbean — or the other way around). This rhythm was also to be found in the limbo (a Trinidadian genre), which was also played on the rhythm guitar by the influential Bo Diddley in Chicago. This rhythm is played here on the clave on Quiereme, Camagueyana (1926).

The relaxed son style contrasted with Spanish-Cuban danzón, which was more formal and jerky. On March 21, 1927, the Sexteto Habanero was joined by Enrique Hernández on cornet, soon replaced until February, 1928, by the legendary trumpet player Félix Chapottín. The Septeto Habanero was born, and with its copper instrument (listen to El Tomatero) it became as modern as nearby New Orleans jazz, where soloists were also a new phenomenon. Other charangas including a trumpet appeared, such as Ignacio Piñeiro’s Sexteto, then Septeto Nacional.

Piñeiro was an Abakuá (the Cuban incarnation of a secret society from Calabar in modern-day Nigeria) and he knew Afro-Cuban traditions. His orchestra was to remain one of the best. In eastern Cuba, Oriente, Miguel Matamoros had his first hit record in 1928. This great composer and lyric writer brought together the son style and the troubadour tradition, the trova (some of which are also found here, performed by El Indio Naborí and Los Compadres, with and without Compay Segundo), which contrasted with the conjunto orchestras.

He who would one day star in the Buenavista Social Club. Matamoros played a sophisticated form of son using punteado guitar (finger picking where the bottom string is played with the thumb) and refined vocal harmonies. He reached international success with Trío Matamoros. His famous Mamá, Son de la Loma (in a 1955 version here) tells that son had come all the way from the Oriente mountains down to the plains and to the capital city. As it did on all son musicians, rumba had left a deep mark on him.

Danzón was popular in private clubs, the sociedades, where various communities of Cuban society defined themselves through their ethnicity, their trade and their income. Even Black clubs rejected son, but as Septeto Habanero and Trío Matamoros became popular they opened the doors of even the most posh sociedades.

In several private parties where alcohol flowed (including some attended by members of the governement and President Machado himself), where venal women flocked, and in dance academies and brothels, son music from the Afro-Cuban society suited the spirit of clients who’d come to slum it better than danzón did. As jazz did in the USA around the same time, it broke through more and more. President Machado was loathed by his citizens, and he tried to get the Black vote — the very Blacks his police cruelly oppressed.

Musicians who dared to play bongos in public were jailed without mercy, but by the end of the 1920s son had become mainstream Cuban music. Its success was also thanks to the radio then on the rise, which broadcast it all over the country during the following decade. Conga drums (tumbao) were related to banned carnivals and Black slums, and they remained prohibited until the 1930s (except for ‘lounge’ congas used in White shows). Armed with their guitars only, troubadours managed hours of live radio broadcast, and classical guitar was trendy. Son, the music of the people, stood against racial segregation and was supported by protesters and students.

The 1929 depression hit the island hard, as it depended a lot on American tourism and sugarcane exports. The first revolution overthrew Machado in 1933, leading to a year of anarchy, followed a coup by Fulgiencio Batista. Almost nothing was recorded between 1930 and 1936 but radio shows did broadcast son, in a revolutionary tone that contrasted with that of many conventional radio stations (which aired serials, classical music, danzón and its radio variante, the danzonete).

And, by 1937, the U.S. mafia had got its hands on Cuban casinos by promising Batista he would get his cut.

Son Montuno

In 1938, Artie Shaw’s rendition of Cole Porter’s ‘Begin the Beguine,’ a beguine similar to Cuban bolero-son, helped in popularizing Caribbean music in the United States. Miguelito Valdés was one of the first Whites to sing son, rumba and other ‘Afro’ rhythms with his jazz orchestra, Orquesta Casino de la Playa. The coast was clear: genuine son then thrived in a new form — the orchestra.

Fed ‘Congo’ culture (his grandfather had been a Bantu slave), Arsenio Rodríguez was a Black, blind, illiterate Abakuá from a poor sugarcane-farming family who had moved from Güines to Havana. He mastered the tres guitar and fell in love with son, the scorned Creole music that was slightly less disdained than rumba.

RCA had started recording again in 1937; Afro-Cuban bands were banned from theaters and it was Casino de la Playa who dared to cut several innovative tunes, including Arsenio Rodríguez’ ‘Bruca Maniguá,’ which openly sported its ‘carabali’ (Calabar) ‘Black nation’ slave identity, and violence. This was a complaint delivered in bozal language, a sabir used by African newcomers, and that had been spoken by Arsenio’s grandfather — a first in Cuba.

The whole thing was played with a clave rhythm; piano arpeggios typical of Cuban music had surfaced, copying the part normally played on the tres guitar, itself copying the Central Africa sanza. Conga drums were not outlawed anymore, dictator Batista had freed them and Carnival parades were now marching to the sound of drums.

The legendary Arsenio was the first master of son montuno leading a conjunto (Cuban style orchestra); he disrupted the music of his country in 1949. After Arsenio’s departure to the USA in 1952, he passed his band on to skilled trumpeter Félix Chapottín. Composer and master drummer Chano Pozo, a tough shoe-shine Abakuá boy from the same rough neighbourhood as Arsenio, had also started recording. He’d soon migrated to New York where he recorded with Dizzy Gillespie.

The Golden Age of Son

U.S. tourism was happening in Cuba before WWII. But after 1945, the standard of living on the continent reached new heights and tourists flocked to Cuba, which was presented as an attractive, sunny playground where casinos, hotels, cabarets, musical shows, girls — and alcohol — abounded. Besides the troubadours, full ‘conjunto’ orchestras featuring tres, trumpets, piano, percussion and vocal choruses were blooming: Conjunto Tipico Habanero, Conjunto Casino, Ignacio Piñeiro’s Septeto Nacional, Conjunto Marquetti.

Big bands, such as Beny Moré’s, Orquesta Sublime, Orquesta Rey Diaz Calvet, Chapottín y sus Estrellas, Orquesta Kubavana, Orquesta Sabor de Cuba and many others were hitting their stride — this was the great golden age of Cuban music, where son ruled.

RCA Victor and Columbia had so far been the only labels recording Cuban music. Post-war Cuban recordings were dominated by an independent brand named Panart, founded in 1943 and owned by Ramón Sabat. He had opened a recording studio in Havana and there was no more need for portable gear or renting radio station studio time.

Soon more record production companies challenged Panart in the 1950s, including Kubaney, Puchito, Velvet, Fama, Maype, Gema, Suaritos, and still RCA, which created its local branch, Discuba in 1959.

Panart’s top group was La Sonora Matancera, who hired the best singers, such as Bienvenido Granda, then the excellent Myrta Silva, replaced in 1950 by Celia Cruz. Cruz later went on to become the ‘Undisputed Queen of Salsa’ and piled up major hits like Burundanga in 1954. Their style, the openly Black son montuno (‘son from the mountains’), was emblematic of local Afro authenticity and ruled Cuban orchestras as mambo and soon cha cha chá became trends abroad, where many orchestras, like Xavier Cugat’s, had started copying them.

By then similar Cuban styles, including rumba, pregón, afro, guaracha, guarija, mambo, bolero, pachanga and more, were often merged in son orchestras (see details in the discography). After Don Azpiazú’s 1930 U.S. version of El Manisero (‘The Peanut Vendor’), the impact of Cuban music in the USA and the world became very significant. This is documented in another set in this series.

For example, Ignacio Piñeiro met George Gerschwin in 1932, which led the American composer to borrow part of Echale Salsita (where the first mention of the word ‘salsa’ in Cuban music can be found) on his Cuban Overture. El Cumbanchero became the reggae classic Rockfort Rock. And the bass line on the montuno pachanga Pescadores de Camaron by Conjunto Marquetti sounds much like Bob Marley & the Wailers’ famous ‘Natural Mystic.’

The island depended almost completely on sugar exports to the U.S., but the sugarcane earnings did not benefit the people; almost everything was being imported, including goods also produced in Cuba, which suffered unfair competition. The prices of these goods were very high for the wretched population, who could rarely afford access to those amazing, lush orchestras. Nothing was being invested in education, agriculture and infrastructure, which motivated a revolution.

Fidel Castro and his men arrived in Havana on December 31, 1958. The entire music industry was nationalised on May 29, 1961, triggering the exodus of many musicians, including Celia Cruz and producers like Sabat. Cuban music was never the same again.

Bruno Blum, January, 2019.

With thanks to Chris Carter for proofreading.

© Frémeaux & Associés 2019

. Ned Sublette, Cuba and Its Music, From the First Drums to the Mambo (Chicago Review Press, 2004).

. Also read the booklets and listen to Roots of Funk 1947-1962 and Haiti - Meringue & Konpa 1952-1962 in this series..

. Maya Roy, Cuban Music (Latin American Bureau, London, 2002).

. Read the booklet and listen to Cuba in America 1939-1962 in this series.

DISC 1 Aluminium and acetate recordings - Classic Son 1926-1952

1. QUIERÉME, CAMAGUEYANA- Sexteto Boloña

(Alfredo Boloña)

Abelardo Barroso-lead v, claves; Jesús “Tata” Gutiérrez -maracas, v; José Vega Chacón-g, v; Alfredo Boloña-tres, leader; “Tabito”-string b; Jose Manuel Incharte aka El Chino-bongos. Brunswick 40158. New York City, October 21, 1926 [son].

2. ERES MI LIRA ARMONIOSA - Sexteto Habanero

(Guillermo Castillo)

José Jimenez aka Cheo-lead v, claves; Felipe Neri Cabrera Urrutia-maracas-v; Guillermo Castillo García-g, v; Carlos Godínez Facenda-tres, v; possibly Miguel Garcia-v; Gerardo Martínez Rivero-string b, v, leader; Andrés Sotolongo or Agustín Gutiérrez aka Mañana-bongos. His Master’s Voice G.V. 22 (England). New York City, October 21, 1927 [son].

3. EL TOMATERO - Septeto Habanero

(Graciano Gómez)

Same as above, probably Jose Intérián-cornet, tp. Victor XVE 67192-2. New York City, February 22, 1931 [son].

4. BRUCA MANIGUA - Orquesta Casino de la Playa

(Arsenio Rodríguez)

Miguelito Valdés-v; Anselmo Sacasas-leader. RCA Victor 82114-A (U.S.), 1937. Havana, June 1937 [son afro].

5. SACALE BRILLO AL PISO TERESA - Chano Pozo Y Su Orquesta Con El Mago Del Tres

(Arsenio Rodríguez)

Marcelino Guerra-v, claves; Mario Cora-tp; Arsenio Rodríguez-tres; Frank Gilberto Ayala-p; Panchito Riset, George Alonso aka Candy Store-v; Bilingüe-bongos; Chano Pozo-congas. Coda 5061. New York City, February 12, 1947 [son montuno].

6. AY! NICOLAS - Conjunto Casino

(Alberto Armenteros)

Roberto Faz, Agustín Ribot, Roberto Espí-v; musicians include: Alberto Armenteros-tp; José Gudín or Miguel Román-tp; Roberto Alvarez-p; Orlando Guzmán-bongos; Carlos Valdés aka Patato-congas. Havana, Cuba, circa 1941-1946 [son montuno].

7. ADIVINALO - Conjunto Arsenio Rodríguez

Arsenio Rodríguez

(José L. Forest)

Estela Rodríguez, René Scull-lead v; Félix Chapottín-tp; Carmelo Alvarez or Alfredo Armenteros aka Chocolate-tp; Arsenio Rodriguez-tres; Carlos Ramirez-harmony v, g; Luis Martínez Griñan aka Lili-p; Lázaro Prieto-string b; Anatolín Suárez aka Papa Kila-bongos; Félix Alfonso-Congas. Havana, 1948 [son montuno].

8. NO ME LLORES MAS - Conjunto Arsenio Rodríguez

(Luís Martínez Griñan)

Estela Rodríguez, René Scull-lead v; Félix Chapottín-tp; Carmelo Alvarez or Alfredo Armenteros aka Chocolate-tp; Arsenio Rodriguez-tres; Carlos Ramirez-harmony v, g; Luis Martínez Griñan aka Lili-p; Lázaro Prieto-string b; Anatolín Suárez aka Papa Kila-bongos; Félix Alfonso-Congas.

Havana, January 12, 1949 [son montuno].

9. LLÉVATELO TODO - Conjunto Arsenio Rodríguez

(Luís Martínez Griñan)

Same as above. Havana, February 19, 1949 [son montuno].

10. EL VELORIO - Bienvenido Granda W/Sonora Matancera

(Rubén Escobar)

Bienvenido Granda-lead and background v; Conjunto La Sonora Matancera: Calixto Leicea-tp; Pedro Knight -tp; Ezequiel Frías aka Lino: p; Carlos Pablo Vázquez Gobín aka Bubú -string b; Carlos Manuel Diaz Alonso aka Caíto-maracas, background v; Rogelio Martínez Díaz-g, background v, leader; Angel Alfonso Furias aka Yiyo-congas. Seeco SSD-1001-A (U.S). Havana, circa 1950 [guaracha son].

11. EL CUMBANCHERO [Rockfort Rock]- Celia Cruz W/Sonora Matancera

(Rafael Hernandez)

Same as above except Celia Cruz-v; Leonard Melody, arr. Ansonia SALP-1605 (U.S.). Havana, circa 1950 [guaracha afro son].

12. YO CANTO EN EL LLANO - Duo Los Compadres [W/Compay Segundo]

(Francisco Repilado aka Compay Segundo, Lorenzo Hierrezuelo)

Lorenzo Hierrezuelo-g, lead v; Máximo Francisco Repilado Muñoz Telles aka Compay Segundo-armónico (seven string guitar), harmony v. Sonoro 110-A, 1953. Havana, circa 1951 [trova, son].

13. QUE CORTO ES EL AMOR - Myrta Silva W/Sonora Matancera

(Myrta Silva)

Conjunto La Sonora Matancera, same as 11 except Myrta Silva-lead v. Havana, April 4, 1952 [son montuno].

Tape Recordings - Classic Son 1951-1957

14. MENTIRAS CRIOLLAS - Conjunto Chapottín

(Félix Chapottín)

Miguelito Cuní-v; Félix Chapottín-tp; Armendo Armenteros-tp; 5scar Velazco aka Florecita-tp; Luis Martínez Griñan-p; possibly Alberto Abreu-bongos; possibly Humberto Fuentes-congas; maracas, vocal chorus. Panart LP 2051 (Cuba). Havana, circa 1952 [son montuno].

15. BURUNDANGA - Celia Cruz W/Sonora Matancera

(Félix Chapottín, Óscar Muñoz Bouffartique)

La Sonora Matancera: possibly same as 11 except Celia Cruz-v; Elpidio Vázquez-string b. Seeco SCLP 54 (U.S.), 1954. Havana, 1954 [montuno afro].

16. ALTO SONGO - Conjunto Casino

(Luis Martínez Griñan)

Possibly Alberto Beltrán-v; possibly Ildefonso Salinas-tp; possibly Rolando Baro-p; possibly Bárbaro Jabuco-congas; bongos, vocal chorus. Panart LP-2051 (Cuba), 1957. Havana, circa 1956 [guajira son].

17. EL HUÉRFANITO - Conjunto Típico Habanero

(Miguel Matamoros)

Manolo Furé-harmony v; string b, leader; vocal chorus, tp, bongos, congas. Guantanamera L.P. 5006 (Venezuela). Havana, circa 1955 [son].

18. GALAN GALAN - Conjunto Típico Habanero

(C. Castillo)

Manuelito Furés-lead v; possibly Félix Chapottin-tp; tres, string b, vocal chorus, bongos, congas. Guantanamera 5045-A [Venezuela]. Havana, circa 1955 [son].

19. ELENA LA CUMBANCHERA - Sexteto Típico Habanero

(Gerardo Martínez)

Same as 16. Coleccion de Oro CDO 1202 (Cuba). Havana, circa 1955 [son].

20. ECHALE SALSITA - Ignacio Piñeiro W/Septeto Nacional

(Ignacio Piñeiro)

Ignacio Piñeiro-v; Rafel Ortiz aka Mañungo-harmony; harmony v, tp, bongos, congas. Jagua 201-A (Cuba), circa 1957. Havana, circa 1957 [pregón son].

21. ESAS NO SON CUBANOS - Ignacio Piñeiro W/Septeto Nacional

(Ignacio Piñeiro)

Ignacio Piñeiro-v; Rafel Ortiz aka Mañungo-harmony; harmony v, tp, bongos, congas. Sierra Maestra SMLD-P1 [Cuba 1962]. Havana, circa 1957 [son capricho].

22. CARAMELO A KILO - Celia Cruz W/La Sonora Matancera

(Roberto Puentes)

Possibly same as 15. Havana, circa 1955 [son montuno].

23. ELLA Y YO - María Teresa Vera y su Conjunto

(Óscar Hernández, Ulrico Ablanedo)

María Teresa Vera-v; Lorenzo Hierrezuelo-g; v, tres, tp, bongos, congas. Musicians unknown. [trova, bolero son]. Guantanamera 5045-A [Venezuela]. Havana, date unknown [son].

24. QUE ES EL AMOR? - Bienvenido Granda, Caíto, Rogelio

(Severino Ramos)

Probably same as 11, except for Bienvenido Granda-v, Carlos Manuel Diaz aka Caíto-v; Rogelio Martínez-g, v, leader. Seeco SSD 1001. Havana, ca. 1954 [son montuno].

Disc 2 - Classic son 1953-1958

1. NUEVO RITMO OMELENKO - Celia Cruz W/Sonora Matancera

(Eduardo Angulo)

Probably same as disc 1, 15 except for Celia Cruz-v. Seeco SLP-54. Havana, 1954 [son montuno].

2. BAILARÁS - Bienvenido Granda W/Sonora Matancera

(Jesús Martínez Leonard)

Arranged by Severino Ramos; Rogelio Martínez-Leader. Probably same as CD 1, 9, except for Bienvenido Granda-v. Seeco 45-7364 (U.S.). Havana, 1953.

3. CANCANEITO CAN - Laito Sureda W/Sonora Matancera

(Gastón Palmer)

Probably same as disc 1, 15, except Laito Sureda-v. Seeco SSD 10010. Havana, circa 1954 [guaracha son].

4. JUANCITO TRUCUPEY - Celia Cruz W/Sonora Matancera

(Luis Kalaff)

Probably same as disc 1, 15 except for Celia Cruz-v. Seeco 45-7507. Havana, circa 1954 [son montuno].

5. MAMA, SON DE LA LOMA - Trío Matamoros

(Miguel Matamoros)

Miguel Matamoros-g, v; Rafael Cueto-v, g; Siro Rodríguez-v, claves.

Kubaney MT-116 (Cuba), 1955. Havana, 1955 [trova, son].

6. MI SONCITO - Celia Cruz & Nelson Pinedo W/Sonora Matancera

(Isabel Valdés) [aka “My Tune”]

Probably same as disc 1, 15 except Celia Cruz, Nelson Pinedo-lead v. Seeco 7586 (Cuba). Havana, 1955 [son montuno].

7. SANDUNGUEATE - Celia Cruz W/Sonora Matancera

(Senen Suarez)

Probably same as disc 1, 15 except for Celia Cruz-lead v. Seeco SCLP 9067 (U.S.). Havana, 1956 [son montuno].

8. EL MANISERO [aka “The Peanut Vendor”] - Abelardo Barroso y Orquesta Sensación

(Moisés Simóns)

Abelardo Barroso-lead v; Orchestra. Puchito 262 (Cuba), 1958. Havana, 1956 [pregón son].

9. CANTA LA VUELTABAJERA - Ignacio Piñeiro W/Septeto Nacional

(Ignacio Piñeiro)

Ignacio Piñeiro-v; Rafel Ortiz aka Mañungo-harmony; harmony v, tp, bongos, congas. Sierra Maestra SMLD-P1 [Cuba 1962]. Havana, circa 1957 [guajira son].

10. SIXTO EL CARAMELERO - Nelson Pinedo W/Sonora Matancera

(Humberto Juama)

Probably same as disc 1, 15 except for Nelson Pinedo-lead v. Seeco SCLP 9104 (U.S.). Havana, 1957 [son montuno].

11. SACA LA LENGUA - Orquesta Sublime

(Julia Perez)

Melquiades Fundora-flute; lead v, vocal chorus, p, string b, maracas, bongos, congas. Panart LP-2051 (Cuba), 1957. Havana, 1957 [son montuno].

12. GÜEITA CAIMAN - Fantasmita W/Carlos Barberia & Orquesta Kubavana

(Juan Zayas Lastra)

Fantasmita-v; Carlos Berberia-leader. Panart 2034 (Cuba) 1957. Havana, 1957 [son montuno].

13. LA QUIJA - Conjunto Casino

(José Zamora Montalvo aka Jorge Zamora aka Zamorita)

Agustín Ribot or Roberto Faz-lead v, Carmen Delia Dipiní-v; vocal chorus; Miguel Roman-tp; Roberto Espi-leader; Agustín Ribot-perc; tp, p, maracas, bongos, congas. Panart LP-2006 (Cuba), 1957 [son descarga].

14. FELICIDADES - Joe Valle y su Orquesta

(Noro Morales)

José Elias Valle Marrero as Joe Valle-lead v, leader; vocal chorus, orchestra. Seeco SCLP 9104 (U.S.), 1957. New York, 1957 [son montuno, descarga].

15. QUE NO MUERA EL SON - Conjunto Marquetti

(José Marquetti, Walfrido Guevara)

José Marquetti as Cheo Marquetti-lead v; lead v (duet), tp, tp, p, string b; bongos, congas. Panart LP-2051 (Cuba), 1957. Havana, 1957 [son montuno].

16. POR QUE ME SIENTO CUBANO - Conjunto Marquetti

(Odrezia Madrazo)

Same as above.

17. GOZA MI SON MONTUNO - Conjunto Casino

(Miguel Roman)

Roberto Espi, Niño Rivera-lead v. Panart LP-2051 (Cuba), 1957. Havana, 1957 [son montuno].

18. MULATA LINDA - Orquesta Rey Diaz Calvet

(Ramón Cabrera)

Lead v; male chorus, tp, tp, tp, string b, bongos, congas. Panart LP-2051 (Cuba), 1957. Havana, 1957 [son montuno].

19. SAN LUISERA - Grupo Compay Segundo

(Manuel Proveda)

Francisco Repilado aka Compay Segundo-armónico [seven string g], v; Amparo Repilado-v; g; string b; guira; bongos, congas. Panart 45, 1957. Havana, circa 1957 [son].

20. VOY PA’ MAYARI - Grupo Compay Segundo

(Francisco Repilado aka Compay Segundo)

Francisco Repilado aka Compay Segundo-armónico [seven string g], v; harmony v, g, tp, string b; guira bongos, congas. Panart LP-2051 (Cuba), 1957. Havana, 1957 [pregón son].

21. APRIETALA EN EL RINCON - Conjunto Marquetti

(Walfrido Guevara)

José Marquetti as Cheo Marquetti-lead v; vocal chorus, tres, tp, p, string b; bongos, congas. Panart LP-2051 (Cuba), 1957. Havana, 1957 [guajira son].

22. ESO SE HINCHA - Bienvenito Granda W/La Sonora Matancera

(Pablo Cairo)

Bienvenito Granda lead v; Severino Ramos-arr. La Sonora Matancera: probably same as disc 1, 15. Seeco SCLP 9120 A (U.S.), 1957 [son montuno].

23. ECHALE GRASA - Orquesta Novedades

(Agustín Ribot)

Possibly Agustín Ribot-v; possibly Melquiades Fundora-flute; vocal chorus, g, p, string b, strings, maracas, bongos, congas. Panart LP-2051 (Cuba), 1957. Havana, circa 1957 [descarga son].

24. MENTIRAS CRIOLLAS - Chapottín y sus Estrellas

(Félix Chapottín)

Miguelito Cuní-v; Félix Chapottín-tp; possibly Aquilino Valdés or Cecilio Serviz-tp; Luis Martínez Griñan aka Lili-p; Alberto Abreu-bongos; Humberto Fuentes-congas. Panart LP-2051 [son montuno]. Havana, circa 1957.

DISC 3 - Classic Son 1958-1962

1. AMOR SILVESTRE - Los Compadres

(Reynaldo Hierrezuelo)

Lorenzo Hierrezuelo, v, g; Reynaldo Hierrezuelo aka Rey Caney-v, tres; string b; maracas, bongos, congas. Seeco-Vogue LD. 375-30 (France), 1958. Havana, 1958 [son maracaibo].

2. LINDA SOBEDIA - Los Compadres

(Lorenzo Hierrezuelo)

Same as above [capricho son].

3. GUAJIRA GUANTANAMERA - El Indio Naborí y su Grupo Guajiro de Guitarras

(José Fernández Díaz aka Joseito Fernández, added lyrics by Jesús Orta Ruiz)

Jesús Orta Ruiz aka El Indio Naborí-v, g; Huerta, Menendez, Aguilar, Rodriguez-g, backing v. Panart LP-2052 (Cuba), circa 1958. Havana, circa 1958 [guajira son].

4. EL DIABLO TUN TUN - Miguelito Cuní y Septeto

(Bienvenido Julian Gutiérrez)

Miguelito Cuní-lead v; Félix Chapottín-tp; lead v (duet), tres, string b, bongos, congas, vocal chorus. Gema LPG-1108 [Cuba], 1958. Havana, 1958 [son].

5. NICO CADENON - Chapottín y sus Estrellas

Miguelito Cuní-lead v; Conrado Cepero-v; René Álvarez-v; Arturo Harvey aka Alambre Dulce-tres; Udalberto Fresneda aka Chicho-g, v; Carlos Ramírez-g, v; Félix Chapottín-tp; Pepín Vaillant-tp; Aquilino Valdés-tp; Cecilio Cerviz-tp; Luis Martínez Griñan aka Lilí-p, arr.; Sabino Peñalver-b; Félix Alfonso aka Chocolate-congas; Antolín Suárez aka Papa Kila-bongos. Produced by Ernesto R. Duarte Brito. Duher DHS 1606 (Spain). Estudios Radio Progreso de la Habana, Havana, April 1958.

6. MARIQUITAS Y CHICHARRONES - Chapottín y sus Estrellas

Same as above [son montuno].

7. SONERO - Cheo Marquetti y su Orquesta

(Agustín Ribot)

José Marquetti as Cheo Marquetti-lead v; chorus, tres, tp, p, string b; bongos, congas. Panart 45-2081-A (Cuba). Havana, circa 1958 [son].

8. EL CONGO - Celia Cruz W/Sonora Matancera

Javier Vazquez Lauzurica-arr. La Sonora Matancera: possibly same as disc 1, 15 except Celia Cruz-v; Elpidio Vázquez-string b; Rogelio Martínez-g, chorus v, leader; Pedro Knight-tp; Elpidio Vásquez-b; Simon Domingo Esquijarroza-perc. Seeco CELP-432 (U.S.), 1959. Havana, 1959.

9. VEN BERNABÉ - Celia Cruz W/Sonora Matancera

(Agustín Lara, Santiago Ortega)

La Sonora Matancera: possibly same as disc 1, 11 except Celia Cruz-v; Elpidio Vázquez-string b. Fuentes - Seeco 314080 (U.S.), 1959. Musidisc 30 CV 94 (France), 1960. Havana, 1959 [son montuno].

10. PESCADORES DE CAMARÓN - Pío Leyva

(Juan Arrondo, Wilfredo Pascual aka Pío Leyva)

Pío Leyva-lead v; vocal chorus; tres; string b; bongos, congas. Suaritos S-117 [Cuba]. Havana, circa 1960 [montuno pachanga].

11. RESURGE EL OMELENKO - Celia Cruz W/Sonora Matancera

(Javier Vasquez)

Same as disc 3, 8. Seeco SCLP 919920 (U.S.), 1960. Havana, 1960 [guaracha son].

12. A COMER CHICHARRON - Pío Leyva

(Angel Romero)

Wilfredo Pascual aka Pío Leyva-v; vocal chorus, orchestra. RRAS 1012 (Cuba), date unknown. Havana, circa 1961 [son montuno].

13. EL PIO MENTIROSO - Pío Leyva

(Wilfredo Pascual aka Pío Leyva)

Wilfredo Pascual aka Pío Leyva-v; Orquesta Sabor de Cuba: Ramon Valdés aka Bebo-p; Jorge Varona-tp; Alejandro Vivar aka El Negro-tp; Alfredo Armenteros aka Chocolate-tp; Emilio Penalver, Santiago Penalver-saxophone; string b; Eddy Esric, Óscar Valdés Sr., Roberto Garcia-percussion; Blas Egues or Emilo del Monte-timbales. Maype US-131 (U.S.), 1960. Havana, circa 1960 [guajira son montuno].

14. A LA LOMA DE BELEN - Septeto Cubano de Ayer y de Hoy

(Bienvenido J. Gutiérrez)

Vocal chorus, tp, tres, maracas, bongos, congas. Guantanamera 5002 (Venezuela). Havana, circa 1960 [son montuno].

15. CARIÑOSO SI, MENTIROSO NO - Pío Leyva

(Wilfredo Pascual aka Pío Leyva)

Same as CD 3, 10. Maype US-131 (U.S.), 1960. Havana, circa 1960 [son montuno].

16. LA MALANGA - Roberto Espí W/Conjunto Casino

(Rosendo Hernández Padrón aka Rosendo Rosell)

Roberto Espí or Niño Rivera-v; Alberto Diaz-v; Fernando Álvarez-v; Felo Martinez-v; Reinaldo Godinez, Miguel Román, Miguel Sanchez, Ildefonso Salinas-tp; Roland Baró-p; Óscar Hernandez-string b; Rogelio Iglesias-bongos; José Hernandez-congas. Velvet - VE-1700 (Cuba), 1960. Havana, circa 1960 [montuno pachanga].

17. JUNTITOS TÚ Y YO - Celia Cruz con La Sonora Matancera

Same as disc 1, 15. Seeco SCLP 91920 (U.S.), 1960. Havana, circa 1960 [guapacha-son montuno].

18. DIME ADIOS CARMELINA - Pío Leyva

(unknown)

Same as disc 3, 10. Maype US-131 (U.S.), 1960. Havana, circa 1960 [son montuno].

19. OYE COMO SUENA - Pío Leyva

(Wilfredo Pascual aka Pío Leyva)

Same as disc 3, 10. Maype US-131 (U.S.), 1960. Havana, circa 1960 [guajira son montuno].

20. LA BOTIJUELA DE JUAN - Conjunto Sones de Oriente

(Martin Valiente)

Concepción López Serrano, Pablo Correa, Francisco Corrales y Martin Valiente-v; Pablo Correa-leader. Orchestra. Areito - LDA-3371 (Cuba), circa 1962. Havana, circa 1962 [son].

21. MAYEYA, NO JUEGUES CON LOS SANTOS - Septeto Nacional Ignacio Piñeiro

(Ignacio Piñeiro Martínez)

Bienvenido León or Joseito Nuñez, Carlos Embale-v; Lázaro Herrera, Manolito Saenz-tp; Rafael Ortíz aka Mañung-g, v; Antonio Sanchez aka Musiquita-p; Alejandro Abreu Oviedo-string b; Marino Gonzales aka El Principe-bongos; Leonardo Bernabé-congas; Ignacio Piñeiro-leader. Sierra Maestra SMLD-P1 (Cuba), 1962. Havana, circa 1962 [son habanero].

22. SUAVECITO - Septeto Nacional Ignacio Piñeiro

(Ignacio Piñeiro Martínez)

Same as above.

23. ME GUSTA MAS EL SON - Beny Moré

(Enrique Benítez)

Bartolomé Maximiliano Moré Gutiérrez aka Beny Moré-v; orchestra. Discuba 45-1141 A; Havana, circa 1961 [son montuno].

24. TRES LINDAS CUBANAS - Cachao y su Combo

(Antonio María Romeu Marrero aka Antonio María Romeu)

Possibly Alejandro Vivar aka El Negro, Armendo Armenteros-tp; Emilio Peñalver-soprano saxophone; possibly Orestes Lopéz Valdés-p; Israel López Valdés aka Cachao-string b, leader; Federico Arístides Soto Alejo

aka Tata Güines or Ricardo Abreu aka Los Papines-congas; guiro. Maype US-168 (U.S.). Havana, circa 1961 [descarga].

Mélange d’influences ouest-africaines et espagnoles, le son cubain a été remis en lumière par le Buenavista Social Club. Mais il a connu sa période de magie originelle avant la révolution de 1959 où, comme la rumba, il fut longtemps réprimé car il représentait l’expression afro-cubaine. Bruno Blum évoque ici son histoire, sa résilience et son évolution vers la salsa. Remarquablement bien enregistrés, des groupes exceptionnels comme la Sonora Matancera fusionnèrent le fabuleux son avec différents styles essentiels. Équivalent hispanophone de la soul avec un penchant pour la transe, il était le genre le plus populaire de l’île. Découvrez ici des enregistrements souvent introuvables, fondateurs du son authentique — ce que Cuba a donné de meilleur. Patrick FRÉMEAUX

A mix of West African and Spanish influences, Cuban son was brought back to light by the Buenavista Social Club. However, it had gone through its original magic phase before the 1959 revolution when, like rumba, it was long repressed because it embodied Afro-Cuban expression. Bruno Blum tells its story, resilience and evolution towards salsa. It was remarkably well recorded and outstanding groups such as La Sonora Matancera fusioned the fabulous son with various essential styles. A Spanish-speaking equivalent to soul music with a trance twist, it was the most popular genre on the island. Discover here some of the founding, often hard to find recordings of genuine son — Cuba’s very best. Patrick FRÉMEAUX

Mélange d’influences ouest-africaines et espagnoles, le son cubain a été remis en lumière par le Buenavista Social Club. Mais il a connu sa période de magie originelle avant la révolution de 1959 où, comme la rumba, il fut longtemps réprimé car il représentait l’expression afro-cubaine. Bruno Blum évoque ici son histoire, sa résilience et son évolution vers la salsa. Remarquablement bien enregistrés, des groupes exceptionnels comme la Sonora Matancera fusionnèrent le fabuleux son avec différents styles essentiels. Équivalent hispanophone de la soul avec un penchant pour la transe, il était le genre le plus populaire de l’île. Découvrez ici des enregistrements souvent introuvables, fondateurs du son authentique — ce que Cuba a donné de meilleur. Patrick FRÉMEAUX

A mix of West African and Spanish influences, Cuban son was brought back to light by the Buenavista Social Club. However, it had gone through its original magic phase before the 1959 revolution when, like rumba, it was long repressed because it embodied Afro-Cuban expression. Bruno Blum tells its story, resilience and evolution towards salsa. It was remarkably well recorded and outstanding groups such as La Sonora Matancera fusioned the fabulous son with various essential styles. A Spanish-speaking equivalent to soul music with a trance twist, it was the most popular genre on the island. Discover here some of the founding, often hard to find recordings of genuine son — Cuba’s very best.

Patrick FRÉMEAUX