- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

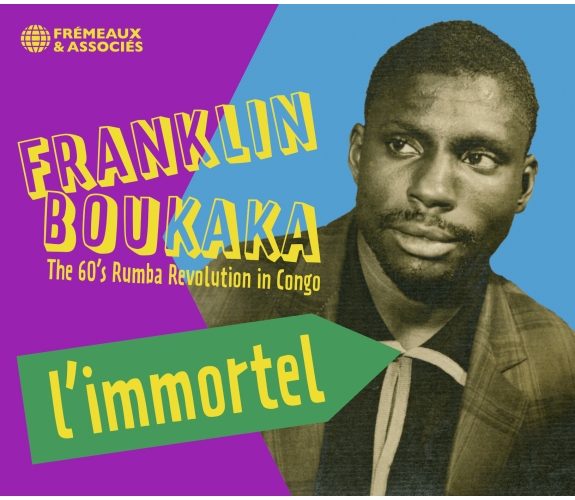

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

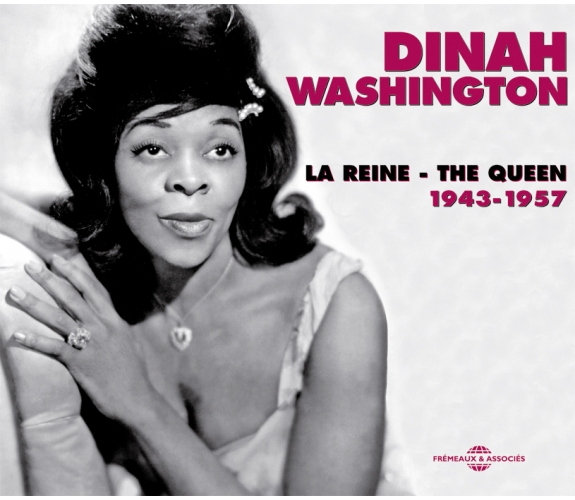

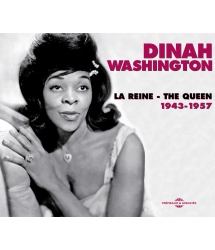

LA REINE - THE QUEEN - 1943-1957

Ref.: FA5209

Artistic Direction : JEAN BUZELIN

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Total duration of the pack : 2 hours 7 minutes

Nbre. CD : 2

LA REINE - THE QUEEN - 1943-1957

LA REINE - THE QUEEN - 1943-1957

“Dinah Washington, the “Queen of the blues”, was the most outstanding blues artist among female jazz singers and the greatest female jazz vocalist to sing the blues! She occupies a place in the history of Afro American vocal art at the summit, alongside Bessie Smith, Billie Holiday, Mahalia Jackson and Ella Fitzgerald. Jean Buzelin allows the listener to discover the amazing talent of Dinah Washington in this 42 titles double CD-set accompanied with a French and English 24 pages booklet.” Patrick Frémeaux

THE EMPRESS 1923 - 1933

INTEGRALE 1954-1955

ELLA FITZGERALD

LADY AND PRES 1937-1941

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Evil Gal BluesDinah WashingtonL. Feather00:02:552008

-

2Blow Top BluesDinah WashingtonL. Feather00:03:212008

-

3My Lovin' PapaDinah WashingtonD. Henderson00:03:092008

-

4The Man I LoveDinah WashingtonG. & I. Gershwin00:03:042008

-

5Oo We Walkie-TalkieDinah WashingtonDémetrious00:02:502008

-

6Postman BluesDinah WashingtonD. Washington00:02:592008

-

7Ain't MishbehavinDinah WashingtonT. Waller00:02:512008

-

8Resolution BluesDinah WashingtonL. Swain00:03:222008

-

9Long John BluesDinah WashingtonD. Washington00:03:142008

-

10Cool Kind PapaDinah WashingtonD. Washington00:02:132008

-

11It Isn't FairDinah WashingtonR. Himber00:02:282008

-

12Baby Get LostDinah WashingtonL. Feather00:02:422008

-

13I Wanna Be LovedDinah WashingtonE. Heyman00:03:022008

-

14Fast Movin' MamaDinah WashingtonD. Washington00:01:532008

-

15Richest Guy In The GraveyardDinah WashingtonL. Feather00:02:552008

-

16I'll Never Be FreeDinah WashingtonBenjamin00:02:502008

-

17Big DealDinah WashingtonD. Washington00:02:452008

-

18Ain't Nobody's Business, But My OwnDinah WashingtonGrisham00:03:092008

-

19I Won't Cry AnymoreDinah WashingtonA.Frish00:03:242008

-

20Wheel Of FortuneDinah WashingtonBenjamin00:02:172008

-

21Trouble In MindDinah WashingtonR.M. Jones00:02:522008

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Pillow BluesDinah WashingtonD. Cobb00:02:572008

-

2I Cried For YouDinah WashingtonFreed00:02:302008

-

3Feel Like I Wanna CryDinah WashingtonT.Kirkland00:03:222008

-

4Am I BlueDinah WashingtonC. Akst00:03:172008

-

5My Man's An UndertakerDinah WashingtonT. Kirkland00:02:332008

-

6Short JohnDinah WashingtonE. Crane00:02:552008

-

7Big Long Slidin' ThingDinah WashingtonKirkland Leroy00:03:002008

-

8I Don't Hurt AnymoreDinah WashingtonJ. Rollins00:03:132008

-

9No MoreDinah WashingtonB. Russel00:03:252008

-

10Teach Me TonightDinah WashingtonS. Cahn00:02:502008

-

11I Just Couldn't Stand It No MoreDinah WashingtonCrawford00:03:022008

-

12Make The Man Love MeDinah WashingtonD. Fields00:05:322008

-

13Blue GardeniaDinah WashingtonB. Russel00:05:182008

-

14There'll Be Some Changes MadeDinah WashingtonHiggins00:03:022008

-

15Willow Weep For MeDinah WashingtonA. Ronnell00:03:272008

-

16There'll Be A JubileeDinah WashingtonMoore00:02:092008

-

17You Let My Love Get ColdDinah WashingtonJ.M. Robinson00:02:322008

-

18You're CryingDinah WashingtonQ. Jones00:03:322008

-

19Somebody Loves MeDinah WashingtonG. Gershwin00:02:352008

-

20Blues Down HomeDinah WashingtonL. Chase00:02:492008

-

21Black And BlueDinah WashingtonT. Waller00:02:582008

Dinah Washington - La reine

Dinah Washington

La reine - The queen

1943-1957

Elle a conduit sa vie sur les chapeaux de roue. Une nuit, elle lui a échappé, brutalement, stupidement. Au petit matin, la Reine était morte. À l’âge de 39 ans dont vingt gravés sur disques. Dinah Washington n’avait pas eu le temps de regarder en arrière, pas eu le temps de faire le point, pas eu le temps de se relire. Aussi son œuvre est-elle d’une extraordinaire densité, d’une exceptionnelle vitalité, sans la moindre redite, toujours en mouvement. Tout en couleurs vives, ses chants éclatent avec le plus grand naturel et vous emplissent des pieds à la tête. Tour à tour la chanteuse exprime l’éventail complet des sentiments, de la joie à la tristesse, de l’humour à la mélancolie, de la malice à la raillerie, à la manière d’une meneuse de revue qui change de costume et apparaît, à la fois pareille et différente, dans chaque tableau devant nos yeux médusés. Dinah, The Queen, savait tout chanter et elle chantait merveilleusement. Née le 29 (ou le 22) août 1924 à Tuscaloosa (Alabama) dans le Sud ségrégationniste, Ruth Lee Jones a trois ans lorsqu’elle émigre à Chicago. Toute petite, elle baigne dans les chants sacrés que sa mère lui apprend. Celle-ci, évangéliste missionnaire, emmène sa fille avec elle lorsqu’elle fait la tournée des églises à travers le pays. Ruth ne tarde pas à s’installer derrière le piano et, dès l’âge de 11 ans, en 1935, elle accompagne les offices de la St. Luke’s Baptist Church de Chicago. Elle va même bientôt devenir chef de chœur de la youth choir de l’église. La gamine est douée et le montre : en 1939, à quinze ans, elle remporte un concours d’amateurs au Regal, le plus grand théâtre noir de Chicago, ce qui lui vaut un premier engagement au Flame Show Bar. Mais elle retrouve en 1940 le circuit du gospel après sa rencontre avec la chanteuse Sallie Martin, l’ancienne associée de Thomas A. Dorsey et pionnière du gospel moderne. À 16 ans, elle devient sa pianiste et joue également avec Willie Mae Ford Smith, une autre grande chanteuse liée à l’entreprise Dorsey. Elle tourne ensuite, comme soliste, au sein des Sallie Martin Singers, dans les états du Sud et du Midwest. Malheureusement, aucun disque ne vient témoigner de cette période. Mais l’appel des planches séculières est le plus fort et Ruth ferme pour de bon les portes du temple derrière elle. De retour à la musique profane, cette fois définitivement, elle débute professionnellement dans les cabarets de Chicago. D’abord au Rhumboogie en 1941 puis, en 1942, à la Downbeat Room du Sherman Hotel où elle se produit avec Fats Waller, au Three Deuces et au Garrick Lounge avec The Cats & The Fiddle, un quartette vocal/instrumental de jive music très populaire à l’époque, tandis qu’au même moment et au rez-de-chaussée (le Garrick Stage Bar) chante Billie Holiday, de neuf ans son aînée, que Ruth va écouter très attentivement. C’est probablement Joe Sherman, le patron du Garrick, qui lui trouve son nom de scène, Dinah Washington, à moins que ce ne soit l’impresario Joe Glaser qui l’entend et la recommande à Lionel Hampton dont le big band en plein essor pète de tous ses feux. Le vibraphoniste vient écouter cette jeune chanteuse dont on dit monts et merveilles et l’engage. Dinah a dix-huit ans et demi lorsqu’elle débute avec l’orchestre au Regal Theater en février 1943, retrouvant le lieu de ses premiers pas sur une grande scène. Et durant près de trois années, elle va accompagner la tonitruante machine à swing dans tous les dancings et théâtres du pays et sur les plus grandes scènes new-yorkaises : l’Apollo de Harlem (en 1943/44), le Strand Theater, le Capitol Theater (en 1944), etc. Malheureusement, aucune face commerciale en big band ne va entériner son séjour chez Hampton. D’abord, nous sommes en pleine grève des enregistrements, le Petrillo Ban, ensuite parce que les gens de chez Decca, la maison de disques de Lionel, ne sont intéressés que par l’orchestre seul. Deux témoignages subsistent. Le premier, Choo Choo Baby, est une transcription AFRS-Jubilee (enregistrement destiné aux stations de radio) datant de la fin novembre 1943, le second, Evil Gal Blues, sera capté au Carnegie Hall en avril 1945. Mais à la fin du mois de décembre 1943, alors que l’orchestre anime la semaine de Noël à l’Apollo de Harlem, le critique Leonard Feather réussit à organiser une séance pour le petit label Keynote (qui brave donc les interdictions du syndicat des musiciens) avec quelques-uns des solistes d’Hampton comme Joe Morris (trompette), Arnett Cobb (saxo-ténor) et le pianiste Milt Buckner. Le chef est venu sans son vibraphone mais donne accessoirement un coup de main à la batterie et au piano sur deux morceaux. Publiés sous le nom de “Lionel Hampton & His Sextet with Dinah Washington Evil Gal Blues, écrit par Feather pour Hot Lips Page, et Salty Papa Blues(1) seront parmi les succès les plus appréciés du public noir durant l’année 1944, mais il faudra pourtant attendre un an et demi avant que la chanteuse ne retrouve les studios. En mai 1945, Decca lui accorde “généreusement“ un morceau durant une séance du big band ; trois solistes dont Wendell Culley (trompette) et à nouveau le grand ténor Arnett Cobb, la section rythmique et le vibraphone du chef accompagnent la chanteuse. Blow Top Blues, un blues magistral publié sous le nom de Lionel Hampton, fera tranquillement son chemin pour entrer au hit parade... en 1947. Entre temps en 1946, Dinah avait quitté Lionel. En décembre 1945, Dinah Washington est à Los Angeles où les studios lui sont offerts durant plusieurs jours par la marque Apollo. La chanteuse est alors accompagnée par un all stars de studio dirigé par Lucky Thompson. Ce jeune saxophoniste prometteur, transfuge de l’orchestre de Count Basie, a réuni quelques jeunes loups comme Charles Mingus (qui sera le contrebassiste de Lionel Hampton en 1947 !) et Milt Jackson, lesquels ne vont pas tarder à faire parler d’eux dans des expressions issues du be bop. En cette période de remue-ménage musicaux, Dinah reste encore fidèle aux structures du blues et toutes les faces de ses trois séances appartiennent à cet idiome. Particulièrement réussies et admirablement chantées, elles mettent aussi en valeur les généreuses interventions de Thompson au ténor et la pertinence et la finesse musicales de Jackson au vibraphone (My Lovin’ Papa).

La carrière phonographique de Dinah Washington est désormais sur les rails et rien ne l’arrêtera plus. Elle signe un contrat avec Mercury et, en janvier 1946, entame avec cette jeune marque ambitieuse un bail qui s’achèvera en 1961 avec quelque chose comme 400 faces enregistrées ! Si, dès ses premiers disques sur ce label, elle élargit son répertoire en y ajoutant standards et thèmes de jazz comme The Man I Love, elle conserve un solide répertoire bluesy (Postman Blues avec l’orchestre de Tab Smith). Superbement chanté, The Man I Love ne souffre pas de la comparaison avec Billie Holiday dont elle égale l’intensité dramatique. Durant ces deux années 46 et 47, même si ses disques n’atteignent pas encore des ventes considérables, la chanteuse assoit sa réputation avec des passages sur les meilleures scènes comme à l’Apollo de Harlem, au Regal de Chicago ou au Foster’s Rainbow Room de la Nouvelle-Orléans. Au Regal, elle est accompagnée par l’orchestre de Louis Jordan. Quel chemin parcouru ! En 1948, cinq titres apparaissent coup sur coup dans les hit parades. Parmi eux une belle version du classique de Fats Waller, Ain’t Misbehavin’, où elle est simplement accompagnée par un trio “à la King Cole“, et Resolution Blues qui bénéficie du solide soutien de la formation du trompettiste Cootie Williams et de ses commentaires expressifs. Mais ce ne sont que broutilles car, en juillet 1949, Baby Get Lost entre dans les charts Rhythm & Blues de la revue Billboard et poursuit son ascension jusqu’au sommet : deux semaines à la première place sur quatorze de présence !(2) Sur la lancée de ce hit, l’autre face du disque, Long John Blues, gravé un an auparavant mais conservé au chaud, atteint le mois suivant la 12e place. L’un après l’autre, des blues (Good Daddy Blues) et surtout des ballades (I Only Know, It Isn’t Fair, I Wanna Be Loved, I’ll Never Be Free) sont classé au Top Ten R&B durant la seule année 1950(3) Aux morceaux originaux, réalisés en studio avec accompagnement d’orchestres placés en général sous la direction du batteur Teddy Stewart (l’un de ses maris), nous avons préféré des versions beaucoup plus rares. Celles que nous proposons ici ont été enregistrées live durant un “Just Jazz Concert” organisé à Los Angeles par Gene Norman et Frank Bull, sans doute durant l’été 1950. Ce formidable document donne une excellente illustration de l’ambiance survoltée qui régnait dans l’assistance, et de la façon dont le public noir enthousiaste réagissait à chacune de ses chansons en poussant la chanteuse à se dépasser. L’envergure de son expression, la justesse, le placement, la qualité de diction et la flexibilité de sa voix permettent à Dinah Washington de reprendre des pièces comme Ain’t Nobody’s Business, tiré d’un vieux standard autrefois chanté par Bessie Smith et adapté récemment par Jimmy Witherspoon qui en a fait le succès de l’année 1949(2). De même qu’elle s’adapte à merveille à tous les types d’accompagnement qu’on lui propose : les cordes dans I Won’t Cry Anymore (encore un grand succès classé n°6), les orchestres de variétés, les groupes vocaux, et bien sûr les orchestres de jazz comme celui du batteur Jimmy Cobb qui partage à cette époque la vie mouvementée de la chanteuse. Wheel Of Fortune (3) et le classique du blues Trouble In Mind sont classés respectivement n°3 et 4 au Top national R&B ; le second titre permettant au grand ténor Ben Webster de faire entendre sa voix. Aussi rare est la présence bénéfique, parmi quelques ellingtonniens, de Paul Gonsalves dans I Cried For You, pur morceau de jazz. Mais le plus régulier d’entre eux est Paul Quinichette, surnommé le “vice-président“, et qui pour Dinah, représente peut-être l’interlocuteur le plus proche, comme l’était le “président“ Lester Young avec Billie (Feel Like I Wanna Cry, Am I Blue, Make The Man Love Me…). Puis on verra apparaître Eddie Chamblee, à qui la chanteuse glissera bientôt l’une de ses bagues au doigt…

Au tournant des années 40/50, Dinah Washington, surnommée “La Reine du Blues”, est devenue la chanteuse la plus populaire auprès de la communauté de couleur(4). Entre 1945 et 1955, elle est la vedette quasi obligée de la “Harlem Variety Revue” à l’Apollo Theater chaque fois que ses incessantes tournées la ramènent à New York (en 1946, elle est soutenue par le grand orchestre du saxophoniste-chanteur Eddie Vinson). On l’entend à Detroit, Philadelphie, Los Angeles... Elle réussit là où beaucoup ont échoué : à la fois conserver ses racines, sa “base” et sa popularité auprès de sa communauté, et s’ouvrir vers d’autres formes dont le jazz. Pour cela, les meilleurs musiciens du moment vont la servir. Dans ses disques de jazz, publiés en 33 tours, les interprétations, non limitées par le temps comme sur les 45 tours, permettent à la chanteuse comme aux solistes de s’exprimer plus longuement. Dinah se montre parfaitement à l’aise au sein de ces environnements souples et modernes, même si elle demeure fidèle aux textes des chansons ; elle ne pratique pas le scat comme le feraient Ella Fitzgerald ou Sarah Vaughan dans des circonstances similaires. Ses producteurs ne craignent pas de la mettre en présence, sur une scène de Los Angeles en 1954, du quintette Clifford Brown-Max Roach auxquels se joignent quelques autres invités. Parmi cet ensemble, considéré comme l’un des plus “avancés“ de son époque, la chanteuse, sans rien renier de son style, se meut avec aisance et autorité (No More)(5). Pour la petite histoire, notons que, se précipitant au Birdland le soir même de son arrivée à New York, Marcel Zanini y découvre, impressionné… Dinah Washington qu’il ne connaissait pas !(6) Pendant ce temps, avec son répertoire plus populaire, Dinah ne quitte guère le haut du tableau en cette année 1954. Parmi ses meilleures ventes auprès de sa communauté, retenons le scandé I Don’t Hurt Anymore, bien dans la ligne du rhythm and blues (n°3), et Teach Me Tonight, belle ballade bluesy, reprise “colorée“ d’un hit des DeCastro Sisters (n°4). En mars 1955, une nouvelle séance “jazz” est organisée. Dinah est entourée de quelques-uns de ses meilleurs et plus fidèles accompagnateurs, et les arrangements, très légers, sont signés par le jeune et prometteur Quincy Jones. Il en résulte une superbe série d’interprétations dont nous avons retenu Make The Man Love Me sur un tempo médium lent, au cours de laquelle la chanteuse intègre une citation de I Got It Bad de Duke Ellington — solistes : Paul Quinichette, Clark Terry, Wynton Kelly et Jimmy Cleveland — et Blue Gardenia, considéré par Dan Morgensten entre autres, comme l’une des plus belles ballades chantées par Dinah Washington — solistes : Quinichette, Barry Galbraith et Cecil Paune. L’album qui les réunit est titré “For Those in Love”, on ne peut mieux dire. L’été de cette même année, Dinah est invitée pour la première fois au Newport Jazz Festival. Elle participe aussi à l’émission télévisée “Showtime at the Apollo” et apparaît dans plusieurs films : “Harlem Jazz Festival” et, en 1956, “Basin Street Revue” et “Rock ‘n’ Roll Revue”. Elle tourne également au sein d’un “Alan Freed R&B package show” qui présente les plus grandes vedettes noires à travers le pays. On peut aussi l’applaudir dans tout le pays : à Boston, Philadelphie, Las Vegas, Miami, New Orleans, Detroit, Washington, San Francisco, Hollywood, Chicago, Baltimore… Tout en continuant à alimenter le marché des 45 tours et les juke-boxes (cinq titres classés en 55 et 56), les producteurs de chez Mercury publient de plus en plus d’albums 33 tours en direction d’un public plus large d’amateurs (essentiellement blancs) de jazz et de grande variété (pop music). Ainsi les albums “Dinah” d’où sont extraits There’ll Be Some Changes Made et Willow Weep For Me, et “In The land of HiFi” qui comprend There’ll Be A Jubilee avec une intervention de Cannonball Adderley. Fin 1956, à nouveau sous la direction de Quincy Jones qui conduit un orchestre de rêve, Dinah Washington enregistre un You Let My Love Get Cold, orienté vers le R&B, et qui ne figure pas sur l’album “The Swinging Miss «D»” où l’on retrouve une série de thèmes de jazz. Ceux-ci vont de Somebody Loves Me, composé par Gershwin en 1924 — solos : Anthony Ortega, Jimmy Cleveland, Don Elliott — à You’re Crying, un original de Quincy Jones lui-même — solos : Lucky Thompson, Jimmy Cleveland, Charlie Shavers et Urbie Green. Suit un “Fats Waller Songbook” qui comprend notamment un superbe Black And Blue conduit par son mari du moment, Eddie Chamblee, et arrangé par Ernie Wilkins. Enregistré lors de la même séance, Blues Down Home, avec un robuste solo de Chamblee, ne figure pas dans l’album mais sur un 45 tours single. Lesquels se raréfient en même temps que les apparitions de la chanteuse dans les hit parades. C’est avec cette dernière séance que se termine notre anthologie, la loi sur le domaine public ne nous permettant pas de poursuivre plus avant pour le moment. Mais, avec déjà quinze années d’enregistrements à notre disposition, le choix s’avérait suffisamment large pour offrir le panorama le plus représentatif possible de l’art de la chanteuse.

Bien qu’elle soit désormais bien engagée dans le circuit jazz avec, notamment en 1958, un engagement au Birdland, le célèbre club new-yorkais, et une nouvelle invitation au Newport Jazz Festival, immortalisée par le film “Jazz on a Summer Day”, Dinah marque toujours son attachement à ses racines. Ce que souligne le “Bessie Smith Songbook” qui affirme la filiation naturelle qui existe entre l’“Impératrice” et la “Reine du Blues”. En 1959, Dinah Washington effectue une tournée européenne qui la conduit notamment en Angleterre, où elle chante au London Paladium devant… la Reine (l’autre). Tournée qui, hélas, évite la France sauf... le temps d’une apparition éclair et incognito à Paris au Mars Club où elle interprète quelques morceaux devant les yeux ébahis de Kurt Mohr présent dans la salle ! C’est cette même année qu’elle entre au Top Ten Pop — elle y reste 17 semaines ! — et obtient un Grammy Award avec What A Diff’rence A Day Made, chanson qui sera reprise plus tard par Sarah Vaughan et Esther Phillips, peut-être sa meilleure disciple. Son retour tonitruant dans les charts relance commercialement la carrière de la chanteuse (Unforgettable n°15 en 1959). En 1960, c’est l’apothéose de sa carrière avec trois n°1 nationaux — un record — dont deux en duo avec le chanteur Brook Benton : Baby, You’ve Got What It Takes et A Rockin’ Good Way qui encadrent This Bitter Earth. Ce passage dans le monde de la “grande variété” n’émousse en rien ses qualités et sa fraîcheur vocales même si certains accompagnements ambitieux (sic) sont parfois un peu lourds à digérer. Rançon de la gloire pour quelqu’un qui restera, même si sa couronne brille sous les feux du Carnegie Hall (1959), toujours fidèle au jazz (Birdland en 1961/62, Village Vanguard en 59), et au blues (Apollo en 61), sans compter des participations aux festivals de jazz d’Indiana (1960) et de Buffalo (1960 et 61). Après deux albums sur lesquels elle reprend, à la fin décembre 1961, quelques-uns de ses anciens succès, Dinah Washington quitte Mercury pour signer un contrat avec la compagnie Roulette. Plusieurs albums un peu “surchargés”, y compris son “Back to the Blues” qui sera son memorial posthume, sont produits et la chanteuse obtient un ultime succès en faisant entrer Tears And Laughters dans le Top Ten en février 1962. “Rires et larmes”, quel meilleur titre pourrait-on trouver pour résumer la carrière et la vie de la Reine ! En 1963, celle qui demeure The Queen of the Blues est à l’apogée de sa carrière. Elle a chanté avec Count Basie à Chicago, avec Duke Ellington à Detroit. Et c’est dans la cité de l’automobile, après une soirée un peu trop arrosée, qu’elle s’avale bêtement une dose exagérée de pilules de régime. Le mélange est explosif, le cœur n’y résiste pas(7). Dinah Washington meurt le 14 décembre 1963. Elle n’a que 39 ans !

De là à l’ajouter à la liste des femmes artistes noires victimes des dures conditions de leur situation, il y a un pas qu’il faut se garder de franchir précipitamment. Contrairement à celles de Billie Holiday, Big Maybelle, Esther Phillips, Big Mama Thornton et d’autres, la vie de Dinah Washington ne ressemble pas vraiment à un long calvaire sur fond de drogue entrecoupé de brèves “stations” lumineuses. Dinah aimait la vie d’un appétit sans mesure, collectionnant les coups de tête, les esclandres publics, les amants et les maris (au moins sept ou huit officiels) — “Je change de maris avant qu’ils ne me remplacent” disait-elle. Un tempérament ! Mais ses frasques n’ont jamais nuit à la qualité de son art. C’était une grande professionnelle, une musicienne capable de chanter, avec un égal résultat, blues, ballades, pop songs, jazz, standards de Broadway... Lorsqu’elle déclarait elle-même : “je peux chanter n’importe quoi”, “I can sing anything“ ce n’était pas par vantardise, elle savait ce qu’elle disait. Sans toutefois livrer peut-être la clef de sa pensée intime, elle avait parfaitement conscience de ses capacités. Elle pouvait tout chanter et tout bien chanter y compris un répertoire de “variété” qui, au tournant des années 50/60, ne brillait pas forcément par sa qualité musicale. Mais Dinah était une star, elle appartenait au showbiz américain et, à ce titre, lui devait quelques obligations. D’autres y sont passés et non des moindres. Mais même si elle ne semblait plus contrôler totalement sa production phonographique, elle était restée “la Reine”, celle des petites gens de son peuple comme celle des amateurs, encore qu’elle n’ait pas eu le temps de vraiment conquérir l’Europe (contrairement à Billie Holiday, Ella Fitzgerald ou Sarah Vaughan par exemple). Les possibilités vocales de la chanteuse lui permettaient sans problème de sortir du cadre harmonique du blues et, pour elle comme pour ses producteurs, aborder d’autres matériels présentait des avantages à la fois sur le plan de l’enrichissement artistique et sur celui de l’élargissement de son audience. Majoritairement noir à ses débuts, son public allait petit à petit s’éclaircir, si je puis dire, suivant en cela l’évolution du jazz. Le seul répertoire qu’en fin de compte elle négligera sur disques, est celui des chants sacrés où la chanteuse avait fait ses débuts et où ses talents s’étaient fait remarquer. Elle ne nous laissera, en 1953, que Silent Night et The Lord’s Prayer dans des versions un peu pompières destinées sans doute à marcher sur les plates-bandes de Mahalia Jackson. Dommage. Dinah Washington fut peut-être la seule chanteuse de l’histoire de la musique afro-américaine à mener aussi brillamment une double carrière. Elle avait réussi, en s’appuyant sur les racines du gospel et du blues, à combiner en un équilibre parfait la double influence de Bessie Smith et de Billie Holiday (auxquelles on peut ajouter d’un côté Ma Rainey et de l’autre Ethel Waters). À son tour elle a fortement marqué la plupart des grandes chanteuses populaires noires des années 50/60 : Ruth Brown, Etta James, Esther Phillips, Dionne Warwick, Nancy Wilson, Diana Ross, Diane Schuur, etc, sans parler de ses aînées comme Helen Humes qui infléchiront leur manière à l’écoute de sa voix acidulée. Dinah possédait une diction parfaite, un sens de la nuance tout en subtilités, et une “sophistication naturelle”, n’appuyant jamais ses effets, ne cherchant pas à travailler une voix légèrement nasillarde qui conservera toujours la fraîcheur mutine de sa jeunesse. Dinah Washington avait oublié de vieillir...

Jean BUZELIN

© 2008 Frémeaux & Associés

Notes :

1. Salty Papa Blues a été réédité dans le double CD “Women in Blues” (FA 018).

2. À noter que Billie Holiday elle-même s’empressa d’enregistrer à son tour Baby Get Lost pour Decca en août 1949 en même temps que Ain’t Nobody’s Business.

3. I’ll Never Be Free, l’un des gros tubes du moment, a fait l’objet d’une sérieuse concurrence dans les charts derrière Dinah,entre les versions d’Anisteen Allen (avec Lucky Millinder), d’Ella Fitzgerald en duo avec Louis Jordan, d’Annie Laurie (avec Paul Gayten) et de Savannah Churchill. Quant àWheel Of Fortune, également défendu par plusieurs artistes, c’est Sunny Gale qui devance Dinah et le groupe des Cardinals.

4. Si l’on additionne les hits recensés par la revue Billboard entre 1943 et 1959, Dinah Washington est la chanteuse favorite du public noir devant Ruth Brown, LaVern Baker, Ella Fitzgerald et Julia Lee… Billie Holiday se classe 14e !

5. Pour des questions de minutage, nous avons choisi l’un des seuls morceaux “courts” de cet album publié sous le titre “Dinah Jams”.

6. Voir l’interview de Marcel Zanini dans “Zanini, Rive Gauche” (FA 5082).

7. Ponctuées de périodes euphoriques auxquelles succèdent des moments de dépression, les dernières années voient la chanteuse user et abuser des boissons alcoolisées et des remèdes de toutes sortes que, soi disant pour maigrir, elle ingurgite sans discernement.

Nous remercions en particulier Alain Tomas qui nous a prêté quelques disques de sa collection. Certains passages du texte du livret ont été empruntés aux CDs “The Queen of the Blues” (EPM/Blues Collection 159152) et “The Queen Sings Jazz” (EPM/Jazz Archives 159482).

Photos et collections : Frank Driggs, Norbert Hess, James J. Kriegsmann, Jazz Magazine, Michael Ochs, Gilles Pétard, X (D.R.)

english notes

Dinah Washington burnt the candle of her all-too-short life at both ends, until the candle was suddenly extinguished when she was only thirty-nine. During her twenty-year recording career, she never had time to look back, to take stock, to listen to herself. Hence, her work is extraordinarily dense, vital, always fresh, continually on the move. He interprets her wonderfully contrasted songs with total naturalness, utterly overwhelming the listener. She expresses the full range of human emotions, from joy to sadness, from humour to melancholy, from roguishness to mockery. Dinah, The Queen, could sing anything and sing it marvellously. Born Ruth Lee Jones on 29 (or 22) August 1924 in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, she moved to Chicago at the age of three. From an early age she learnt hymns from her mother, an evangelist missionary who took her daughter along on visits to churches throughout the country. Ruth also played piano and, by the time she was eleven, she was already playing at services at St. Luke’s Baptist Church in Chicago before becoming choir leader. Her outstanding gifts soon became evident: in 1939 the thirteen-year-old won a talent contest at the Regal, Chicago’s biggest black theatre, leading to a first engagement at the Flame Show Bar. But she returned to the Gospel circuit in 1939 after meeting Sallie Martin, Tommy Dorsey’s ex-partner and pioneer of modern Gospel. At the age of sixteen she became the latter’s pianist and also played with Willie Mae Ford Smith, another great vocalist from the Dorsey stable. Then she toured the South and Mid-West as soloist with the Sallie Martin Singers but, unfortunately, there are no recordings from this period. However, the attraction of the secular stage became too strong and she closed the doors of the church behind her for good. When she returned to secular singing for good she started her professional career in Chicago clubs. First at the Rhumboogie in 1941, then the following year at the Downbeat Room in Sherman’s Hotel where she appeared with Fats Waller, at the Three Deuces and the Garrick Lounge with The Cats & The Fiddle, a popular vocal/instrumental quartet. At the same time Ruth took every opportunity to listen to Billie Holiday who was singing on the ground floor (the Garrick Stage Bar). It was probably Joe Sherman, boss of the Garrick, who chose her stage name of Dinah Washington, although it may have been impresario Joe Glaser, who recommended her to Lionel Hampton whose band was then riding the crest of the wave and enjoying enormous success. After going along to hear this young singer whom everyone was talking about, the vibraphonist hired her. Dinah was eighteen and a half when she made her debut with the orchestra at the Regal Theater in February 1943, the place where she had made her first stage appearance. She accompanied this colossal swing machine for almost three years in all the dance clubs and theatres throughout the country and on New York’s most renowned stages: the Apollo in Harlem (1943/44), the Strand Theatre, the Capitol Theater (1944) etc.

Regrettably no commercial sides were cut during her spell with Hampton. Not only was the Petrillo ban in full force but Decca, for whom Hampton recorded, was interested only in the orchestra. Just two tracks remain. The first, Choo Choo Baby, is an AFRS-Jubilee radio recording dating from late November 1943 while the second, Evil Gal Blues, was recorded at the Carnegie Hall in April 1945. However, at the end of December 1943, when the band was playing Christmas week at the Apollo in Harlem, critic Leonard Feather managed to set up a session for some of Hampton’s soloists with the smack Keynote label (which risked defying the Musicians’ Union ban) with a few of Hampton’s soloists such as Joe Morris (trumpet), Arnett Cobb (tenor sax) and pianist Milt Buckner. The leader came without his vibraphone but sat in on drums and piano on two titles. Issued under the name of “Lionel Hampton & His Sextet with Dinah Washington” Evil Gal Blues, written by Feather for Hot Lips Page, and Salty Papa Blues(1) were huge hits with black audiences during 1944 but it was a year and a half before Dinah was invited back to the studios. In May 1945 Decca “generously” allowed her a spot during a big band session. She was accompanied by three soloists, including Wendell Culley (trumpet) and again the great tenor saxophonist Arnett Cobb, a rhythm section and Hampton on vibes. The magnificent Blow Top Blues, issued under the name of Lionel Hampton, finally reached the hit parade… but not until 1947. In the meantime, Dinah had already left Hampton in 1946. In December 1945, when Dinah was in Los Angeles, Apollo offered her their studio for several days. This time she was accompanied by an all stars group, led by promising young saxophonist Lucky Thompson, ex-Basie man, who got together some up and coming musicians such as Charles Mingus (who was to become Hampton’s bass player in 1947) and Milt Jackson, both soon to make their mark on the bop scene. However, Dinah still remained faithful to the blues structure, as is evident on all the sides from these three sessions. Beautifully sung, they also leave ample space for judiciously chosen interventions from Thompson on tenor and Jackson on vibes (My Lovin’ Papa). Dinah Washington’s recording career had now really taken off and there was no stopping it. She signed up with Mercury for whom she cut some 400 sides during their association that lasted until 1961! Although, from her very first records with this label, she began to widen her range to include standards and jazz themes such as The Man I Love, she still maintained a solidly bluesy repertoire (Postman Blues with the Tab Smith orchestra). The superbly sung The Man I Love loses nothing in comparison with Billie Holiday whom she equals in dramatic intensity. Throughout 1946 and 47, even though her records were not selling in huge numbers, the singer’s reputation was growing with appearances at some of the most celebrated venues e.g. the Apollo in Harlem, the Regal in Chicago or Foster’s Rainbow Room in New Orleans. At the Regal she was backed by Louis Jordan’s orchestra. What a long way she had come! In 1948 five titles appeared one after the other in the hit parade. They included an excellent version of the Fats Waller classic Ain’t Misbehavin’, on which she is accompanied only by a King Cole-style trio and Resolution Blues that benefits from solid backing from Cootie William’s formation and some expressive comments from the leader himself. But these were only a hint of what was to come for, in July 1949, Baby Get Lost made it into Billboard’s Rhythm & Blues charts and stayed there for fourteen weeks, two of them at the top!(2) On the back of this hit, the flip side Long John Blues, recorded a year previously but kept on ice, reached twelfth place a month after. One after the other blues (Good Daddy Blues) and especially ballads (I Only Know, It Isn’t Fair, I Wanna Be Loved, I’ll Never Be Free) were classed in the in the R&B Top Ten in a single year, 1950(3). Instead of the original studio recordings accompanied by a band, generally led by drummer Teddy Stewart (one of her husbands), we have opted for much rarer versions. We have included those recorded live during a “Just Jazz Concert” organised in Los Angeles by Gene Norman and Frank Bull, almost certainly in summer 1950. They reveal the electrifying atmosphere that reigned and the way in which the enthusiastic black audience reacted to each song, urging the vocalist on to even greater heights. Her vocal range, accuracy, clear diction and flexibility enabled Dinah Washington to reprise pieces like Ain’t Nobody’s Business, based on an old standard sung earlier by Bessie Smith and recently adapted by Jimmy Witherspoon who had a hit with it in 1949(2). In the same way she could also adapt marvellously to whatever backing she was given: strings on I Won’t Cry Anymore (another hit that reached N° 6), variety bands, vocal groups and, of course, jazz orchestras such as that of drummer Jimmy Cobb who shared the singer’s eventful life. Wheel Of Fortune and the blues classic Trouble In Mind were respectively classed at N° 3 and 4 in the national Top R&B charts; the second title featuring the outstanding tenor saxophonist Ben Webster. Paul Gonslaves makes a rare appearance on I Cried For You, a pure jazz title; he was one of the few Ellingtonians to accompany Dinah Washington, the most regular being Paul Quinichette, nicknamed the “vice-president”, who probably represented for Dinah the one to whom she was closest musically, just as the “president” Lester Young was for Billie (Feel Like I Wanna Cry, Am I Blue, Make The Man Love Me …). Then Eddie Chamblee puts in an appearance, on whose finger the singer soon slipped one of her rings …

By the late 40s/early 50s Dinah Washington, now nicknamed, the “Queen of the Blues” had become the most popular singer with coloured audiences(4). From 1945 to 1955, she regularly topped the bill in the “Harlem Variety Revue” at the Apollo Theatre, whenever her touring schedule brought her to New York (in 1946 she was backed by saxophonist/vocalist Eddie Vinson’s big band). She was heard in Detroit, Philadelphia, Los Angeles… She succeeded where many had failed: both in staying close to her roots, her base and her popularity with black audiences, and in opening up to other genres including jazz. In this she was helped by the best musicians around at the time. Her jazz recordings, issued as 33rpms, enabled both the singer and musicians, unhampered by time limits, to express themselves more fully. Dinah appears perfectly at ease within these relaxed and modern surroundings while still remaining faithful to the text of her songs, never resorting to scat as Ella Fitzgerald or Sarah Vaughan did in similar circumstances. Her producers did not hesitate to put her on a Los Angeles stage in 1954, in the presence of the Clifford Brown/Max Roach Quintet, teamed with some other guest stars. She integrated this ensemble, considered one of the most “advanced” of its time, with ease and authority (No More)(5). Just for the record it’s worth mentioning that Marcel Zanini, the same evening that he arrived in New York, rushed to Birdland where he was very impressed by Dinah Washington whom he discovered for the first time!(6) At the same time, with her most popular repertoire, Dinah was rarely out of the top of the hit parade in 1954. Her best sales among her own people included I Don’t Hurt Anymore, in a rhythm and blues style (N° 3), and the beautiful bluesy ballad Teach Me Tonight, a colourful reprise of a DeCastro Sisters hit (N° 4). A further jazz session was organised in March 1955 when Dinah was surrounded by her best and most faithful accompanists with delicate arrangements from the pen of the young and upcoming Quincy Jones. A superb set of interpretations resulted from which we have included the medium tempo Make The Man Love Me, during which the singer incorporates a quotation from Duke Ellington’s I Got It Bad – soloists: Paul Quinichette, Clark Terry, Wynton Kelly and Jimmy Cleveland – and Blue Gardenia that Dan Morgenstern among others considers one of the most beautiful ballads Dinah Washington ever sang. All these titles were regrouped on an album, aptly entitled “For Those In Love”. In the summer of the same year, Dinah was invited for the first time to the Newport Jazz Festival. She also took part in a televised broadcast “Showtime at the Apollo” and appeared in several films: “Harlem Jazz Festival” and, in 1956, “Basin Street Revue” and “Rock ‘n’ Roll Revue”. She also appeared in an “Alan Freed R&B Package Show” which featured the biggest black stars in the country. Audiences were also able to applaud her throughout America: Boston, Philadelphia, Las Vegas, Miami, New Orleans, Detroit, Washington, San Francisco, Hollywood, Chicago, Baltimore… While continuing to supply the 45rpm market and juke boxes (five titles in the charts in 1955 and 56), Mercury issued more and more 33rpm LP aimed at a wider (mainly white) group of jazz and pop music fans. Hence the albums “Dinah” (There’ll Be Some Changes Made and Willow Weep For Me) and “In The Land of HiFi” which included There’ll Be A Jubilee featuring Cannonball Adderley. Late 1956, again directed by Quincy Jones leading a dream orchestra, Dinah Washington recorded You Let My Love Get Cold with a R&B slant which does not appear on the album “The Swinging Miss «D»”, comprising a series of jazz themes. These range from Somebody Loves Me composed by Gershwin in 1924 – solos: Anthony Ortega, Jimmy Cleveland, Don Elliot – to You’re Crying by Quincy Jones himself – solos: Lucky Thompson, Jimmy Cleveland, Charlie Shavers and Urbie Green. A “Fats Waller Songbook” followed with notably a superb Black And Blue fronted by her then husband Eddie Camblee (Ernie Wilkins arranger). Blues Down Home, from the same session with a strong solo from Chamblée, does not appear on the album but as a 45 single. As the latter became less frequent so did the singer’s appearances in the charts. Our anthology ends with this last session as copyright laws prevent us going further for the moment. However, with fifteen years of recordings already available to us the choice is sufficiently wide to offer a truly representative picture of the singer’s work.

Although now firmly installed on the jazz circuit, particularly with an engagement in 1958 at Birdland, the famous New York club, and another invitation to Newport Jazz Festival, immortalised in the film “Jazz On A Summer Day”, Dinah still remained close to her roots. This was evident in “Bessie Smith’s Songbook” which confirmed that the “Queen” of the blues was a natural heir to the “Empress”. In 1959, Dinah Washington embarked on a European tour which took her to England in particular where she sang at the London Palladium before the Queen (the other one!). A tour that, unfortunately, did not include France… except for a brief appearance incognito at the Mars Club in Paris where the few titles she sang completely bowled over Kurt Mohr who was in the audience. The same year she was listed in the Top Ten Pop – she stayed there 17 weeks!- and was awarded a Grammy for What A Difference A Day Made, later taken up by Sarah Vaughan and Esther Phillips, one of Dinah’s best disciples. Her resounding return to the charts relaunched her commercially (Unforgettable N° 15 in 1959). In 1960 her career peaked with three national N° 1s – a record – including two duos with Brook Benton: Baby You’ve Got What It Takes and A Rockin’ Good Way with This Bitter Earth in between. This crossover to “pop” in no way dulled the fine edge of her vocal talent, even though certain ambitious accompaniments are a little difficult to swallow. The price of fame for an artist, who in spite of appearing under the spotlights of Carnegie Hall (1959), always remained true to jazz (Birdland in 1961/62) and the blues (Apollo in 1961) not forgetting appearances at jazz festivals in Indiana (1960) and Buffalo (1960 and 61). After two albums at the end of December 1961 on which she reprised some of her old hits, Dinah Washington left Mercury to sign up with Roulette. Several somewhat overloaded albums, including her “Back to the Blues” destined to be her posthumous memorial, were issued and she had a final hit with Tears And Laughter when it reached the Top Ten in February 1962. What better title to sum up the career and life of the Queen? By 1963, The Queen of the Blues was at the height of her career. She had sung with Count Basie in Chicago, with Duke Ellington in Detroit. And it was here that she died on 14 December 1963 as a result of taking an accidental overdose of slimming pills after an evening’s drinking(7). Her heart could not cope with this explosive mix. She was only 39! But this is no reason to add her to the list of black female artistes who were victims of their tough life. Unlike Billie Holiday, Big Maybelle, Esther Phillips and Big Mama Thornton and others, Dinah Washington’s life was not one long martyrdom of drug addiction interspersed with brief periods of lucidity. Dinah loved life, embraced it to the full, collecting public scandals, lovers and husbands (at least six or seven official ones) on her way – “I change husbands before they change me,” she said. But none of this ever affected her artistic quality. She was a true professional, capable of singing anything: blues, ballads, pop songs, jazz, Broadway standards. When she declared “I can sing anything” it was not a vain boast, she knew what she was talking about. She could sing everything and sing it well including pop songs that, around the 50s and 60s, were not known for their musical brilliance. Dinah was a star; she belonged to American showbiz which implied certain constraints. Others, none the less gifted, trod the same path. Yet, even while she appeared to no longer have total control over her record output, she remained the Queen: the queen for both ordinary black Americans and for her fans, although she did not have time to really conquer Europe (unlike Billie Holiday, Ella Fitzgerald or Sarah Vaughan for example). Her vocal gifts enabled her to go beyond the harmonic confines of the blues and, backed by her producers, to tackle other musical genres. This not only enriched her as a performer but also widened her audience which was mainly black when she started out but gradually included more and more white Americans in line, so to speak, with what was happening in jazz itself. The one type of music Dinah never recorded was Gospel and yet it was her hymn singing that had first made her noticed. She has left us only two religious songs from 1953, Silent Night and The Lord’s Prayer both slightly funereal versions, probably an attempt to invade Mahalia Jackson’s territory. Dinah Washington was probably the only Afro American female singer to succeed so brilliantly in leading a double career. Her success was based on a strong reliance on her blues and Gospel roots, combined with the twofold influence of Bessie Smith and Billie Holiday (plus a hint of Ma Rainey and Ethel Waters). In turn she herself had a marked influence on the great popular black female vocalists of the 50s and 60s: Ruth Brown, Etta James, Esther Phillips, Dionne Warwick, Nancy Wilson, Diana Ross, Diane Schuur etc., not forgetting her elders such as Helen Humes who modified their style after hearing her sing. Dinah’s singing was characterised by clear enunciation, subtle contrasts and an innate sophistication. Her somewhat nasal voice never lost its youthful freshness. Dinah Washington did not have time to get old…

Adapted from the French text by Joyce WATERHOUSE

Notes:

1. Sally Papa Blues has been reissued on the double CD “Women in Blues” album (FA 018).

2. N.B. Billie Holiday herself wasted no time in recording Baby Get Lost for Decca in August 1949 at the same time as Ain’t Nobody’s Business.

3. I’ll Never Be Free, one of the big hits at the time, created serious competition in the charts behind Dinah, between versions by Anisteen Allen (with Lucky Millinder), Ella Fitzgerald in duo with Louis Jordan, Annie Laurie (with Pail Gayten) and Savannah Churchill. As for Wheel Of Fortune, also interpreted by various artists, it was Sunny Gale who beat Dinah and the Cardinals group.

4. The number of hits recorded by the Billboard magazine between 1943 and 1959 prove that Dinah Washington was the favourite singer of black audiences ahead of Ruth Brown, LaVern Baker, Ella Fitzgerald and Julia Lee … Billie Holiday came 14th!

5. For reasons of timing we have chosen one of the shortest tracks from this album issued under the title of “Dinah Jams”.

6. See the interview with Marcel Zanini in “Zanini, Rive Gauche” (FA 5082).

7. Interspersed with periods of euphoria followed by moments of depression, the singer’s final years were marked by alcohol abuse and the use of all kinds of so-called slimming pills that she took indiscriminately.

Special thanks to Alain Thomas for the loan of several records from his collection. Some parts of the text of the CD booklet have been borrowed from the CDs “The Queen of the Blues” (EPM/Blues Collection 159152) and “The Queen Sings Jazz” (EPM/Jazz Archives 159482).

Photos and collections: Frank Driggs, Norbert Hess, James J. Kriegsmann, Jazz Magazine, Michael Ochs, Gilles Pétard, X (D.R.)

DISCOGRAPHIE

CD 1

01. EVIL GAL BLUES (L. Feather) LHS-1

02. BLOW TOP BLUES (L. Feather) 72873

03. MY LOVIN’ PAPA (D. Henderson) S-1174

04. THE MAN I LOVE (G. & I. Gershwin) 393

05. OO WEE WALKIE TALKIE (Demitrious) 392

06. POSTMAN BLUES (D. Washington - T. Smith) 563-4

07. AIN’T MISBEHAVIN’ (T. Waller - A. Razaf - Harper) 1226

08. RESOLUTION BLUES (L. Swain - D. Washington) 1593-1

09. LONG JOHN BLUES (D. Washington) 1785-8

10. COOL KIND PAPA aka GOOD DADDY BLUES (D. Washington - Spencer)

11. IT ISN’T FAIR (R. Himber - F. Warshauer - S. Sprigato)

12. BABY GET LOST (L. Feather)

13. I WANNA BE LOVED (E. Heyman - J. Green - B. Rose)

14. FAST MOVIN’ MAMA D. Washington - Gladstone)

15. RICHEST GUY IN THE GRAVEYARD (L. Feather) 2999-3

16. I’LL NEVER BEE FREE (Benjamin - Weiss) 3408-4

17. BIG DEAL (D. Washington - T. Stewart) 3407-3

18. AIN’T NOBODY’S BUSINESS BUT MY OWN (Grisham) 3879-2

19. I WON’T CRY ANYMORE (A. Frish - F. Wise) 4043-1

20. WHEEL OF FORTUNE (Benjamin - Weiss) 4731-9B

21. TROUBLE IN MIND (R.M. Jones) 4733-4

Dinah Washington (vocal) acc. by :

(1) Lionel Hampton & His Sextet : Joe Morris (tp), Rudy Rutherford (cl), Arnett Cobb (ts), Milt Buckner (p), Vernon King (b), Fred Radclife (dm). New York City, December 29, 1943.

(2) Lionel Hampton & His Septet : Wendell Culley (tp), Herbie Fields (as), Arnett Cobb (ts), Johnny Mehegan (p), Billy Mackel (g), Charles Harris (b), George Jones (dm), Lionel Hampton (vib), Dinah Washington (vo). NYC, May 21, 1945.

(3) Lucky Thompson All Stars : Karl George (tp), Jewel Grant (as), Eli “Lucky” Thompson (ts), Gene Porter (cl, as, bs), Wilbert Baranco (p), Charles Mingus (b), Lee Young (dm), Milt Jackson (vib). Los Angeles, December 12, 1945.

(4-5) Gerald Wilson Orchestra : (personnel include) Gerald Wilson, Eugene “Sooky” Young (tp), Melba Liston, James Robinson (tb), Clyde Dunn, Vernon Slater (ts), Maurice Simon (bs), Jimmy Bunn (p), Henry Green (dm), René Hall (arr). Chicago, April 6, 1946.

(6) Tab Smith Orchestra : (poss. personnel) Frank Galbreath, Russell Royster (tp), Talmadge “Tab” Smith (as), Johnny Hicks (ts), Larry Belton (bs), Charles “Red“ Richards (p), Johnny Williams (b), Walter Johnson (dm). NYC, October 3, 1946.

(7) Rudy Martin Trio : Rudy Martin (p), unknown (g)(b). Chicago, November 13, 1947.

(8) Cootie Williams Orchestra : Charles “Cootie“ Williams, Robert “Bob“ Merrill (tp), Rupert Cole (as), William “Weasel“ Parker (ts), Arnold “Al“ Jarvis (p), Mundell Lowe (g), Leonard “Heavy” Swain (b), Sylvester “Vess“ Payne (dm). NYC, December 30, 1947.

(9) Unknown (cl)(p)(g)(b)(dm). July 1, 1948.

(10-14) Unknown (ts on 12, 14)(p)(g)(b)(dm) + horns ; Gene Norman (M.o.C.). Los Angeles, Just Jazz Concert, ca. Summer 1950.

(15) Teddy Stewart Orchestra : (poss. pers. incl. members of the Dizzy Gillespie Orchestra) Willie Cook or Elmon Wright (tp), Matthew Gee or Charles Greenlee (tb), Jimmy Heath, John Coltrane (as), Johnny Acea (p), Teddy Stewart (dm). NYC, September 27, 1949.

(16-17) Teddy Stewart Orchestra : (pers. include) poss. Benny Powell (tb), Ernie Wilkins (as), Cecil Payne (bs), Freddie Green (g), Ray Brown (b), Teddy Stewart (dm). NYC, May 9, 1950.

(18) Walter Buchanan Orchestra : (pers. include) Wynton Kelly (p), Walter Buchanan (b). NYC, February 27, 1951.

(19) Orchestra conducted by Jimmy Carroll with Strings. NYC, April 12, 1951.

(20-21) Jimmy Cobb Orchestra : (pers. include) Benjamin “Ben“ Webster, Wardell Gray (ts), Wynton Kelly (p), Jimmy Cobb (dm). LA, January 18, 1952.

CD 2

01. PILLOW BLUES (D. Cobb) 9220-8

02. I CRIED FOR YOU (Freed - Arnheim - Lyman) 9249-4

03. FEEL LIKE I WANNA CRY (T. Kirkland) 9793-1

04. AM I BLUE (C. Akst) 9870

05. MY MAN’S AN UNDERTAKER (L. Kirkland - M. Thomas) 10131-4

06. SHORT JOHN (E. Crane) 10242-8

07. BIG LONG SLIDIN’ THING (L. Kirkland - M. Thomas) 10654-11

08. I DON’T HURT ANYMORE (J. Rollins - D. Robertson) 10863-4

09. NO MORE (B. Russell) 10902

10. TEACH ME TONIGHT (S. Cahn - G. De Paul) 11062-16

11. I JUST COULDN’T STAND IT NO MORE (Crawford) 11063-5

12. MAKE THE MAN LOVE ME (D. Fields - A. Schwartz) 11402-8

13. BLUE GARDENIA (B. Russell - L. Lee) 11403-12

14. THERE’LL BE SOME CHANGES MADE (Higgins - Overstreet) 12401-4

15. WILLOW WEEP FOR ME (A. Ronnell) 12418-7

16. THERE’LL BE A JUBILEE (P. Moore) 12875

17. YOU LET MY LOVE GET COLD (J.M. Robinson) 14385

18. YOU’RE CRYING (Q. Jones - L. Feather) 14392

19. SOMEBODY LOVES ME (G. Gershwin - De Sylva - B. McDonald) 14386

20. BLUES DOWN HOME (L. Chase) 15955

21. BLACK AND BLUE (T. Waller - A. Razaf - H. Brooks) 15956

Dinah Washington (vocal) acc. by :

(1) Orchestra directed by Jimmy Cobb : (pers. included) poss. Paul Quinichette or unknown (ts), Wynton Kelly (p), unknown (g), William “Keter“ Betts (b), Jimmy Cobb (dm). Chicago, May 6, 1952.

(2) Orchestra directed by Jimmy Cobb : Clark Terry (tp), Russell Procope (cl, as), Paul Gonsalves (ts), Beryl Booker (p), unknown (g), Keter Betts (b), Jimmy Cobb (dm). Chicago, ca. Summer 1952.

(3) Paul Quinichette (ts), unknown (p), Jackie Davis (org), Keter Betts (b), Jimmy Cobb (dm). New York City, June 10, 1953.

(4) Paul Quinichette (ts), Junior Mance or Sleepy Anderson (p), prob. Jackie Davis (org), Keter Betts (b), Ed Thigpen (dm), Chicago, June 17, 1953.

(5) Unknown orchestra. Ca. late summer 1953.

(6) Unknown orchestra : poss. Clark Terry (tp), poss. Gus Chappell (tb), poss. Ricky Anderson (as), prob. Eddie Chamblee (ts), unknown (bs), Junior Mance or Sleepy Anderson (p), unknown (g), Keter Betts (b), Ed Thigpen (dm). Ca. February/March 1954.

(7) Unknown orchestra : (personnel include) poss. Gus Chappell (tb), Paul Quinichette (ts), Wynton Kelly (p), Barry Galbraith, George Barnes (g), Keter Betts (b), Jimmy Cobb (dm). NYC, June 1954.

(8) Orchestra directed by Hal Mooney : (pers. include) poss. Gus Chappell (tb) ; unknown vocal group. Los Angeles, August 3, 1954.

(9) Clifford Brown (tp), Junior Mance (p), Keter Betts or George Morrow (b), Max Roach (dm). LA, Live, August 14, 1954.

(10-11) Hal Mooney Orchestra. NYC, November 2 or 17, 1954.

(12-13) Clark Terry (tp), Jimmy Cleveland (tb), Paul Quinichette (ts), Cecil Payne (bs), Wynton Kelly (p), Barry Galbraith (g), Keter Betts (b), Jimmy Cobb (dm), Quincy Jones (arr). NYC, March 15, 1955.

(14) Orchestra arranged and conducted by Hal Mooney : (poss. personnel include) Maynard Ferguson, Conrad Gozzo, Manny Klein, Ray Linn (tp), Tom Pederson, Frank Rosolino, Si Zentner (tb), Herb Geller, Skeets Herfurt (as), Georgie Auld, Babe Russin (ts), Chuck Gentry (ts), Wynton Kelly (p), Al Hendrickson (g), Keter Betts (b), Jimmy Cobb (dm). LA, November 11, 1955.

(15) Same. LA, November 12, 1955.

(16) Orchestra arranged and conducted by Hal Mooney : (pers. include) Julian “Cannonball“ Adderley (as), Junior Mance (p). NYC, April 24, 1956.

(17) Quincy Jones & His Orchestra : Ernie Royal, Charlie Shavers, Clark Terry, Joe Wilder (tp), Don Elliott (mellophone), Jimmy Cleveland, Urbie Green, Quentin Jackson, Tommy Mitchell (tb), Anthony Ortega, Hal McKusick (as), Jerome Richardson, Lucky Thompson (ts), Danny Banks (bs), Sleepy Anderson (p), Barry Galbraith (g), Milt Hinton (b), James Crawford (dm). NYC, November 21, 1956.

(18) Same, but Bernie Glow, Nick Travis (tp), Osie Johnson (dm) replace Royal, Wilder and Crawford ; Don Elliott (vib), Ernie Wilkins (arr). NYC, December 5, 1956.

(19) Same as for 17 : Don Elliott (vib). NYC, December 4, 1956.

(20-21) Eddie Chamblee Orchestra : Ernie Royal, Johnny Coles, Joe Newman, Reunald Jones (tp), Melba Liston, Sonny Russo, Julian Priester, Ron Levitt (tb), Frank Wess, Sahib Shihab (as), Eddie Chamblee, Benny Golson (ts), Jerome Richardson (bs), Jack Wilson (p), Freddie Green (g), Richard Evans (b), Charlie Persip (dm), Ernie Wilkins (arr). NYC, October 4, 1957.

CD Dinah Washington La reine - The queen 1943-1957 © Frémeaux & Associés (frémeaux, frémaux, frémau, frémaud, frémault, frémo, frémont, fermeaux, fremeaux, fremaux, fremau, fremaud, fremault, fremo, fremont, CD audio, 78 tours, disques anciens, CD à acheter, écouter des vieux enregistrements, albums, rééditions, anthologies ou intégrales sont disponibles sous forme de CD et par téléchargement.)

-----------

« Un événement à ne pas manquer. Indispensable » par The Lion

Lorsque l’on parle des grandes divas du jazz, on a coutume de citer Billie Holiday, Elle Fitzgerald et Sarah Vaughan, et ce n’est que justice, mais c’est faire peu de cas d’autres voix, moins connues peut-être du grand public comme celles d’Anita O’Day, Helen Humes, Helen Merrill, Carmen Mc Rae et surtout Dinah Washington qui mérite largement une place sur le podium des grandes voix féminines du jazz. Saluons donc avec enthousiasme l’initiative de Patrick Frémeaux de nous offrir ce coffret de deux CD qui réunit les meilleurs enregistrements de « La Reine » gravés entre 1943 et 1952, présentés par Jean Buzelin. Quarante-deux chansons dont bon nombre de standards et quelques blues que Dinah Washington distille de sa voix tour à tour charmeuse et acidulée, sensuelle et puissante, ironique et émouvante, douce et mordante. Des chansons auxquelles elle insuffle son dynamisme et son swing et pour lesquelles elle bénéficie de superbes accompagnements par Lionel Hampton, Tab Smith, Cootie Williams, Jimmy Cobb, Quincy Jones, entre autres. Un événement à ne pas manquer. Indispensable.

Pierre SCHAVEY – THE LION