- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

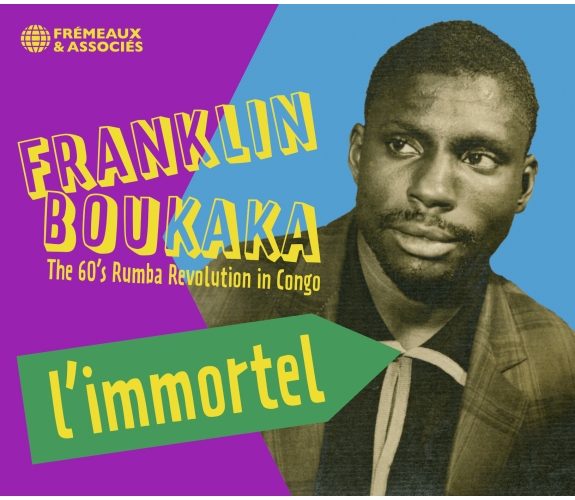

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

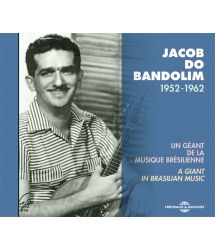

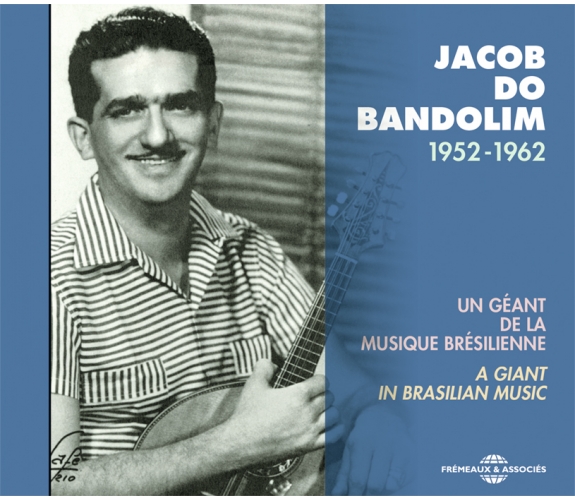

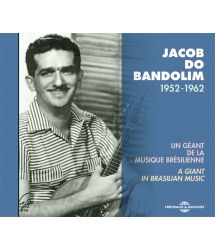

UN GÉANT DE LA MUSIQUE BRÉSILIENNE, 1952-1962

JACOB DO BANDOLIM

Ref.: FA5741

Artistic Direction : TECA CALAZANS ET PHILIPPE LESAGE

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Total duration of the pack : 1 hours 17 minutes

Nbre. CD : 1

UN GÉANT DE LA MUSIQUE BRÉSILIENNE, 1952-1962

UN GÉANT DE LA MUSIQUE BRÉSILIENNE, 1952-1962

This anthology marks the Centenary of the birth of Jacob do Bandolim (February 1918 – August 1969) and contains the bonus of the first-ever release of a archive from a radio programme featuring him with his guests Pixinguinha and Benedito Lacerda. The set perfectly illustrates how this brilliant musician revitalized the choro. Teca CALAZANS et Philippe LESAGE

ANTONIO CARLOS JOBIM - VINICIUS DE MORAES - JOÃO...

CHEGA DE SAUDADE 1959 - O AMOR, O SORRISO E A FLOR...

CHORO CONTEMPORAIN 1978 - 1999

ANTHOLOGIE 1906 - 1947

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1ConfidenciasJacob Do BandolimErnesto Nazareth00:03:162019

-

2FaceiraJacob Do BandolimErnesto Nazareth00:03:122019

-

3O Despertar da MontanhaJacob Do BandolimEduardo Souto00:03:002019

-

4A Ginga do ManeJacob Do BandolimJacob Do Bandolim00:03:042019

-

5AssanhadoJacob Do BandolimJacob Do Bandolim00:03:062019

-

6GraunaJacob Do BandolimJoao Pernambuco00:02:552019

-

7Noites CariocasJacob Do BandolimJacob Do Bandolim00:03:082019

-

8OdeonJacob Do BandolimErnesto Nazareth00:02:342019

-

9TenebrosoJacob Do BandolimErnesto Nazareth00:03:142019

-

10AtlanticoJacob Do BandolimErnesto Nazareth00:03:012019

-

11SimplicidadeJacob Do BandolimJacob Do Bandolim00:02:482019

-

12Migalhas de AmorJacob Do BandolimJacob Do Bandolim00:03:102019

-

13O Voo da MoscaJacob Do BandolimJacob Do Bandolim00:03:322019

-

14Andre de Sapato NovoJacob Do BandolimAndre-Victor Correia00:03:062019

-

15Bola PretaJacob Do BandolimJacob Do Bandolim00:03:222019

-

16Flor de AbacateJacob Do BandolimAlvaro Sandim00:03:132019

-

17AmapaJacob Do BandolimJuca Storoni00:02:572019

-

18AlvoradaJacob Do BandolimJacob Do Bandolim00:03:152019

-

19CochichandoJacob Do BandolimPixinguinha00:02:482019

-

20ChorandoJacob Do BandolimAry Barroso00:03:282019

-

21Proezas do SolonJacob Do BandolimPixinguinha00:02:362019

-

22Rapaziada do BrazJacob Do BandolimAlberto Marino00:02:482019

-

23Aguenta Seu FulgencioJacob Do BandolimLourenco Lamartine00:02:472019

-

24Isso e NossoJacob Do BandolimJacob Do Bandolim00:02:242019

-

25GostosinhoJacob Do BandolimJacob Do Bandolim00:02:332019

-

26Treme TremeJacob Do BandolimJacob Do Bandolim00:02:212019

fa5741 Do Bandolim

JACOB

DO BANDOLIM

1952-1962

UN GÉANT

DE LA MUSIQUE BRÉSILIENNE

A GIANT

IN BRASILIAN MUSIC

Cette anthologie marque le centenaire de la naissance de Jacob do Bandolim ( février 1918) et le cinquantenaire de sa disparition (août 1969) et illustre comment il a revitalisé le choro. Ce coffret présente une archive inédite d’une émission de radio où Pixinguinha et Benedito Lacerda sont ses invités.

Téca Calazans et Philippe Lesage

This anthology marks the Centenary of the birth of Jacob do Bandolim (February 1918 – August 1969) and contains the bonus of the first-ever release of a archive from a radio programme featuring him with his guests Pixinguinha and Benedito Lacerda. The set perfectly illustrates how this brilliant musician revitalized the choro.

Téca Calazans et Philippe Lesage

JACOB DO BANDOLIM

2018 : année du centenaire de la naissance

Comme s’il y avait symbiose entre lui et son instrument de prédilection, Jacob Pick Bittencourt finit par devenir Jacob do bandolim ; ou plus affectueusement encore Jacó. Il nous a quittés le 13 août 1969, suite à un infarctus. Sa vie fut finalement fort courte : cinquante et un ans ; mais elle fut si intense et si riche en réalisations phonographiques qu’il n’a jamais connu le purgatoire. Sa renommée, en son pays natal mais aussi auprès de tous les amateurs de musique brésilienne, est telle comme illustre représentant du choro qu’il nous a semblé, en cette année 2018, date anniversaire du centenaire de sa naissance, impératif de lui dédier une anthologie qui illustrerait aussi bien sa virtuosité d’instrumentiste que sa plume de mélodiste.

Fils unique du pharmacien Francisco Gomes Bittencourt et de Rachel Pick, une polonaise émigrée à la fin de la première guerre mondiale, Jacob Pick Bittencourt est né le 14 février 1918 à Rio de Janeiro. Il passera son enfance et son adolescence à Lapa, dans le centre de la ville qui est alors la capitale fédérale, un quartier populaire plein de bonnes vibrations dans un cadre encore aux allures architecturales coloniales. Au début de son mariage, il vit à Engenho Novo puis, à partir de 1949, à Jacarepagua, une grande maison, avec vérandas immenses, gazons et hauts murs. Il y lance les fameux « saraus de Jacob » où il reçoit amis et invités illustres. Il enregistre tout, note tout, classe tout ; ce qui nous permet aujourd’hui d’avoir accès à ses archives (partitions rares de l’histoire de la musique populaire, bandes d’enregistrement de répétitions, d’émissions de radio, des rodas de choro…) et de découvrir des documents sonores inédits qui dévoilent, s’il en était besoin, ses dons d’improvisateur.

Parcours de vie

En autodidacte, il touche à la guitare, à l’harmonica, au cavaquinho avant de se dédier au bandolim, le nom que les brésiliens donnent à la mandoline. Tout au long de sa vie, il se passionnera pour la lutherie et fera évoluer la forme de son instrument ; il ira même jusqu’à créer un instrument à cordes électrifié au son bizarre : le vibraflex.

A 16 ans, il accompagne Antonio Rodrigues (guitarra portuguesa) et les chanteurs Romario d’Oliveira et Esmeralda Ferreira dans le programme « Horas Luso-brasileira » de Radio Educativa ; ce qui ne manquera pas d’influencer son approche du bandolim. Peu de temps après, ayant monté son propre groupe : lui au bandolim, deux guitares, cavaquinho, pandeiro et petites percussions (« ritmos » dans la lexicographie brésilienne), il gagne un concours face à 27 concurrents, devant un jury constitué, entre autres, du parolier Orestes Barbosa, du chanteur Francisco Alves et du compositeur / flûtiste Benedito Lacerda.

Au début des années 1940, alors qu’il accompagne dans les émissions publiques de la radio des chanteurs, sur les conseils de Donga, le sambiste créateur de Pelo Telefone, il passe un concours d’auxiliaire de justice (greffier). Il se considèrera dès lors comme un amateur non encarté professionnellement. Souvent, il participe comme musicien de studio à des enregistrements ; certains resteront dans l’histoire comme Ai que saudade da Amélia du sambiste Ataulfo Alves (1942 ; il joue du cavaquinho) et Marina (1947, disque de Nelson Gonçalves, chanson de Dorival Caymmi ; il joue du bandolim).

En 1947, il enregistre un premier 78t en soliste, avec une de ses compositions Treme Treme et une de Bonfiglio de Oliveira, Gloria ; succès aidant, six enregistrements s’ensuivront en 1948 et 1949 : Flamengo de Bonfiglio, Flor Amorosa de Joaquim Callado, et de sa plume, Remeleixo, Cabuloso, Salões Imperiais et Feia. Il prouve alors qu’il est un très bon compositeur et un instrumentiste si exceptionnel qu’il devient vite le créateur d’une école du bandolim. Ses compositions : Noites Cariocas, Doce de Coco, Vibrações, Nosso Romance, Santa Morena, Vôo da Mosca, s’imposeront comme des standards toujours repris dans les rodas de choro. Il est inspiré, original ; de la stature de ses maîtres : Ernesto Nazareth et Pixinguinha.

En Mai 1949, insatisfait de la maison de disque Continental, il passe chez RCA Victor, où il enregistrera jusqu’à la fin de sa vie ; soit 48 disques 78 t et 10 LPs, soit 60 compositions propres et 150 d’autres compositeurs en des versions réadaptées et arrangées pour le bandolim. On doit marquer d’une pierre blanche, dans sa discographie quelques albums comme Ao Vivo : Elizeth Cardoso, Zimbo Trio, Jacob do bandolim e Época de Ouro enregistré en le 19 février 1968, au Teatro João Caetano ou Retratos, suite para bandolim, orquestra de cordas e conjunto regional, une œuvre de Radames Gnattali qui portraiture musicalement quatre grands pionniers de la musique brésilienne, en 1964. Il faut relever également qu’il sera le maître d’œuvre du show intitulé Pixinguinha 70 (un disque en restitue la captation) donné en l’honneur de l’anniversaire du maître qu’il vénérait tant et qui disparaitra cinq ans après lui.

Le personnage :

Jacob do bandolim ne laissait personne indifférent tant il était un personnage exigeant, caustique, à la griffe cruelle. Il est de notoriété publique qu’il était un perfectionniste obsessionnel, imposant répétitions sur répétitions à ses musiciens. Il défendait bec et ongles la musique issue du peuple et, en bon brésilien, adorait le football (A Ginga do Mané dit en musique les dribbles facétieux de Mané Garrincha, le petit diable à la jambe tordue, équipier de Pelé). Fumeur invétéré, il succombe à 51 ans, le 13 août 1969, à un second infarctus devant sa résidence, au retour d’une visite à son ami Pixinguinha, avec qui il définissait le répertoire d’un disque autour des œuvres de ce dernier. Mais au fond, tout le monde reconnait que ce donneur de leçon un peu vaniteux et réellement cabochard n’était pas un mauvais bougre.

Le choro :

Pour bien saisir l’espace dans lequel s’inscrit Jacob do bandolim, il n’est pas inutile de revenir sur la gestation du choro en soulignant d’entrée de jeu que l’identité musicale du Brésil s’est forgée dans la rencontre plus ou moins fusionnelle des rythmes africains, des mélodies du Nordeste - où percent les influences amérindiennes et lusitaniennes - et les emprunts mélodiques et harmoniques d’Europe (Portugal, Espagne, Italie, Europe Centrale...). C’est de cette mixture que naitra, dès le milieu du 19e siècle, la musique instrumentale brésilienne qui sera plus tard assimilée, à juste titre, au choro. Lorsqu’elle est mal interprétée, cette musique devient insipide, sans corps ni âme alors qu’en vérité sa beauté tient à ses nuances, à ses modulations et à sa dynamique.

L’instrument et l’instrumentiste

Le bandolim est un instrument dérivé de la mandoline, possédant quatre cordes doubles accordées en quintes. Il y a deux écoles du bandolim : celle du nordestin Luperce Miranda (né en 1904 à Recife; décédé en 1977) et celle de Jacob ; c’est ce dernier qui fait réellement sortir le bandolim du rôle d’accompagnateur pour le hisser au statut de soliste.

Comment expliquer cette évolution ? C’est qu’il transfigure la manière de jouer de cet instrument au son ingrat avec sa fraicheur, sa spontanéité et son sens inné de la simplicité mélodique. Les atouts de Jacob : une précision rythmique inouïe, un son plus portugais que napolitain et par la même plus agréable à l’ouïe. Comme le précise le bandoliniste Pedro Amorim (né au début des années 60) : « il est la référence, l’école, le styliste incontestable. Il est plus proche des guitaristes de jazz actuels dans sa manière d’improviser et plus marqué par l’influence de la guitarra portuguesa dans le son. Luperce est plus napolitain, plus technique et plus virtuose, il a une grande facilité d’ornementation, mais moins de raffinement d’expression ; il n’en reste pas moins que Jacob confessait l’admirer ».

De son côté, Pedro Aragão, bandoliniste quarente ans et docteur en musicologie, enseignant à l’Université Fédérale de Rio de Janeiro, intime de la famille du musicien, confirme les assertions sus-mentionnées : « Oui, c’est vrai, Jacob est un des responsables de la mutation du format de l’instrument. Une bonne observation de la forme du bandolim brésilien démontre qu’il a celle d’une guitarra portuguesa en miniature. Il ne faut pas oublier que Jacob a commencé sa trajectoire musicale en jouant de la guitare dans un groupe de fado et en accompagnant des guitarristas portugais. Sa manière de jouer a été influencée par cette sonorité. Elle fait que le bandolim « chante » d’une manière très proche de la « guitarra portuguesa » et évite au maximum le son sautillant (« som picotado ») caractéristique de la mandoline napolitaine ». Il ajoute pour renforcer le teneur de son discours : « Jacob est le créateur de la sonorité brésilienne, de la manière de jouer du bandolim. Sa manière diffère des interprètes antérieurs, de Luperce Miranda, par exemple, qui était un très grand virtuose mais qui n’avait pas la qualité du son que Jacob émettait (tirava) de son instrument ». L’important est de noter les apports personnels de Jacob que relève Pedro Aragão : « il innove en plusieurs choses : il essaie toujours d’émettre un son legato d’un instrument qui normalement a une sonorité sautillante (picotado) ; il crée des ornements très caractéristiques du choro (appoggiatures, glissandos, portamentos) ; il établit une référence (padrão) dans le trémolo qui est totalement différent de l’italien : le trémolo de Jacob est beaucoup plus expressif, parce qu’il combine des vélocités différentes du médiator. En conclusion, il a un soin plus grand dans le phrasé de la sonorité et dans l’expression ». Dont acte. Ce sont toutes ces particularités qui font que l’auditeur d’aujourd’hui reste fasciné par les enregistrements de Jacob.

L’improvisation :

Pour la critique musicale du monde du jazz, il manque au choro une dimension essentielle, quasiment existentielle, celle de l’improvisation. Ce jugement, peut-être péremptoire et qui ne manque de déclasser à leurs yeux le genre, mérite d’être commenté car Jacob professait que le choro doit être improvisé ; ce qui, selon lui, impliquait que l’instrumentiste apprenne parfaitement le thème pour être en mesure de le développer. L’instrument qui prend en charge le leadership sans le lâcher est la voix soliste qui propulse la mélodie en l’enrichissant de modulations et d’ornementations ; on pourrait aller jusqu’à affirmer que l’instrument soliste se substitue au chanteur absent ; les disques de Jacob sont exemplaires à cet égard. Ajoutons, en passant, que tous les instruments d’un « Regional » (la formation de base d’un Regional est : guitare 6 cordes, Guitare 7 cordes, cavaquinho, bandolim, pandeiro ; auxquels peuvent s’adjoindre flûte, clarinette, saxophones, trombone, accordéon…) sont susceptibles de répondre à de courtes improvisations sur les grilles harmoniques.

Prolongeons cette thématique de l’improvisation avec le professeur Pedro Aragão : « En vérité, le concept d’improvisation est quelque chose de bien large, et est souvent utilisé de manière différente selon les cultures des pays; mais avec la prédominance du jazz, le terme est employé désormais dans la conception que les jazzmen définissent comme improvisation. C’est clair, dans la majeure partie des enregistrements de choro jusqu’à la décade de 1950, il est difficile de trouver des improvisations au sens du jazz ; ce que l’on rencontre sont réellement des variations ( variações ). Il y a des exceptions : Pixinguinha, par exemple, improvisant dans Urubu Malandro. Mais dans la plus grande partie des choros enregistrés par Pixinguinha et par Jacob, de fait, ce sont plus des variations mélodiques que l’on entend. Il faut aussi noter que ce concept d’improvisation peut aussi être étendu à d’autres aspects qui ne sont pas la mélodie : la guitare 7 cordes (violão 7 cordas) improvise des « basses », le cavaquinho improvise les « levadas », etc. Ceci tient au style du « choro ». Et d’ajouter : « oui, les improvisations mélodiques sont beaucoup plus basées sur le concept de variation sur le thème. Ceci ne veut pas dire que l’improvisation n’existe pas dans le choro. Je pense que souvent pour des questions techniques d’enregistrement (temps limité à trois minutes sur les 78 t et chaque face limitée à 36 mn sur les LPs), le soliste n’improvise pas. Mais les enregistrements fait à la maison (« caseiros ») que nous possédons de Jacob dans les rodas de choro montrent Jacob improvisant de belle manière dans le sens défini par les jazzmen, mais toujours en s’inscrivant dans le langage du choro. L’enregistrement qu’il a réalisé de Chega de saudade avec le Zimbo Trio est également impressionnant en ce sens ; il est très proche de ce que réaliserait un improvisateur de jazz ». Pour enrichir sa réflexion, l’auditeur pourra aussi se reporter à l’archive inédite de1952 que nous incluons comme dernière plage de l’album : Pixinguinha improvise des contre-chants au saxophone ténor, Benedito Lacerda improvise à la flûte et Jacob leur répond au bandolim.

Le compositeur

Continuons le dialogue engagé avec le bandoliniste Pedro Aragão, cette fois, sur le thème de l’écriture. « Comme compositeur, explique ce dernier, Jacob allie deux choses importantes : la connaissance parfaite des formes du choro traditionnel et l’attention portée aux innovations des décades 1940/1950. Il savait parfaitement composer en utilisant les formes et styles traditionnels comme les polcas (Mimosa, Saracoteando), le choro (Reminiscencias), le schottish (Heroica) tout en restant attentif aux transformations et influences du choro des décades de 1940/50. Dans les innovations qu’il importe, on peut relever plusieurs dimensions : l’incorporation des influences du boléro et du samba-canção. (Falta-me você, Magoas, Entre mil…você, etc) celles du samba, car Jacob va être un des maîtres du genre choro-sambado aux 32 mesures, contrairement aux 16 mesures de la forme traditionnelle (Bole Bole, Bola Preta, Gostosinho, etc) ; enfin, il se montre sensible aux nouvelles formules harmoniques des compositeurs pré-bossa nova comme Garoto ou Radames Gnattali (on voit cela dans des œuvres comme Assanhado, Doce de Coco, Primas et

Bordões, etc.).

Les commémorations du centenaire

On émet le souhait que les archives laissées par la fille de Jacob soient exploitées le plus rapidement possible dans leur intégralité : elles recèlent des moments où Jacob s’exprime en toute liberté, comme ses enregistrements réalisés à Brasilia, en 1967.

Remerciements : Pedro Aragão, Pedro Amorim, Claire Luzi et Cristobal Soto.

Teca Calazans et Philippe Lesage

© 2018 Frémeaux & Associés

JACOB DO BANDOLIM

2018 — Centenary Year

As if in symbiosis with his favourite instrument, Jacob Pick Bittencourt finally became Jacob do bandolim. Or even more affectionately, Jacó. He passed away on August 13, 1969 after a heart attack, and in the end his life had been very short, merely fifty-one years, but so intense, so rich in recordings, that Jacob never knew purgatory. His fame, not only in his native country but also wherever there are lovers of Brazilian music --- he was among the most illustrious representatives of the choro --- is such that in 2018, the centenary of his birth, it would seem inconceivable not to have devoted to him an anthology that illustrates his virtuosity as an instrumentalist as well as his gifts as a composer of melodies.

The only son of Francisco Gomes Bittencourt, a pharmacist, and Rachel Pick, a Polish immigrant (she left Poland at the end of the Great War), Jacob Pick Bittencourt was born in Rio de Janeiro on February 14, 1918. He spent his childhood and adolescence in Lapa, the centre of the city that was then the federal capital, a popular neighbourhood filled with good vibrations in a setting whose architecture still maintained a colonial appearance. As a newlywed he lived in Engenho Novo and then from 1949 onwards in Jacarepagua, a large house with immense verandas, lawns and high walls. There he started the famous “saraus de Jacob” he hosted for friends and illustrious guests. He recorded everything, noting and filing away every detail… a fact which today allows us to gain access to his archives (rare scores in the history of popular music, magnetic tapes made at rehearsals, at radio shows or in the gatherings of the choro circles known as rodas… hence these newly discovered sounds which unveil the proof, if necessary, of his gifts as an improviser.

Career

He was self-taught, taking up the guitar, the harmonica and the cavaquinho before devoting himself to the bandolim, the name by which the mandolin was known to Brazil. Throughout his life he had a passion for stringed instruments and caused the shape of the mandolin to evolve, even creating a strange-sounding amplified string instrument that he called the vibraflex.

At 16 he accompanied Antonio Rodrigues (who played the Portuguese guitar) and singers Romario d’Oliveira and Esmeralda Ferreira in the radio programme “Horas Luso-brasileira” on Radio Educativa. The experience would certainly influence his approach to the bandolim. Shortly after that he set up his own group — himself on mandolin, two guitars, a cavaquinho, pandeiro, and ritmos (the Brazilian term covering small percussion instruments) — and they won first prize against 27 other competitors facing a jury composed of, among others, the lyricist Orestes Barbosa, singer Francisco Alves and composer/flautist Benedito Lacerda.

Early in the Forties, while accompanying singers in live radio shows, he took the advice of Donga (the sambista who created Pelo Telefone) and took the entrance examination to become a clerk of the court. At the time, Jacob still considered himself to be an amateur without a professional musician’s card, and he often took part in studio recording sessions. Some of them went down in history, like the one that produced Ai que saudade da Amélia by the samba musician Ataulfo Alves (1942), on which he played the cavaquinho, or Marina (1947), a recording by Nelson Gonçalves of a Dorival Caymmi song on which Jacob played the mandolin.

Also in 1947, he recorded a first 78rpm record as a soloist, with one of his own compositions Treme Treme and one by Bonfiglio de Oliveira called Gloria. They were successful and six more recordings followed between 1948 and 1949: Flamengo by Bonfiglio, Flor Amorosa by Joaquim Callado, and four he wrote himself, Remeleixo, Cabuloso, Salões Imperiais and Feia. They proved Jacob was a very good composer, and he was also such an exceptional instrumentalist that soon he founded his own bandolim school. Personal compositions such as Noites Cariocas, Doce de Coco, Vibrações, Nosso Romance, Santa Morena and Vôo da Mosca would become unavoidable standards, and they were almost always featured in choro circles. Jacob was an original, inspired composer with nothing to envy his masters Ernesto Nazareth and Pixinguinha.

By May 1949 Jacob had tired of his record label Continental and moved to RCA Victor, where he would remain until the end of his life. In all, he recorded forty-eight 78rpm records and ten LPs, with a total of 60 compositions of his own plus 150 by other composers in versions that had been readapted and arranged for the bandolim. A few albums in his discography deserve a special mention, like Ao Vivo: Elizeth Cardoso, Zimbo Trio, Jacob Do Bandolim e Época de Ouro, which was recorded on February 19, 1968 at the Teatro João Caetano, or Retratos, suite para bandolim, orquestra de cordas e conjunto regional, a suite that had been written by Radames Gnattali in the form of musical portraits of four great pioneers in Brazilian music (1964.) One can also note that he was behind the show entitled Pixinguinha 70 — a recording of the sound exists — held as a tribute on the anniversary of the master whom Jacob so admired (and who survived Jacob by only five years.)

His personality

Jacob Do Bandolim never left anyone indifferent, such were the rigours of his personality, caustic to the point of cruelty. It was common knowledge that Jacob was obsessive and a perfectionist, which led him to impose rehearsals one after another on all his musicians. He defended the cause of his people’s music like a tiger, and, like the true Brazilian he was, he adored football (A Ginga do Mané tells the story in music of the clowning dribbles of Mané Garrincha, a devil of a player with a twisted leg who was on the same team as Pelé). Jacob was also a chronic smoker, and he died at the age of 51 on August 13, 1969, after a second heart attack struck him down outside his house after a visit to his friend Pixinguinha. They had been discussing the repertoire of a planned recording of the latter’s music. But everyone who knew Jacob recognized that while he was rather vain and used to lecture other people all the time, beneath his stubborn exterior he wasn’t really such a bad fellow after all.

The choro

To fully understand the context surrounding Jacob it can be interesting to take another look at the gestation of the choro by emphasizing at once that the musical identity of Brazil was forged in a more or less intensely close encounter between African rhythms, the melodies of the Nordeste — pierced by Amerindian and Portuguese influences — and borrowings of melody and harmony from Europe (not only Portugal but also Spain, Italy and Central Europe). As early as the mid-nineteenth century, it was from this melting pot that Brazilian instrumental music was born, music forms that were later assimilated, precisely, into the choro. When it is not well performed, this music becomes insipid, i.e. lacking in body and soul, whereas in reality its beauty is dependent on its nuances, modulations and dynamics.

Instrument and instrumentalist

The bandolim is an instrument derived from the mandolin, with four double strings tuned in fifths. There are two schools of bandolim playing: that of Luperce Miranda from the Nordeste (he was born in Recife in 1904 and died in 1977), and that of Jacob Pick Bittencourt. And the latter really took the bandolim away from its accompanying role and turned it into a soloist’s instrument. How can that evolution be explained? Jacob transfigured the way to play this instrument with an ungrateful sound, and he did so with freshness, spontaneity, and an innate feeling for melodic simplicity. Jacob’s trump cards: staggering precision in rhythm, and a sound that was more Portuguese than Neapolitan, which consequently made for more pleasant listening. As pointed out by the bandolim player Pedro Amorim, who was born in the early Sixties: “[Jacob] is the reference, the school, the unarguable stylist. He is closer to the contemporary jazz guitarists in his manner of improvisation, and more marked by the influence of the Portuguese guitarra in sound. Luperce is more Neapolitan; he is more technical and more of a virtuoso, showing great facility for ornamentation, but less refinement of expression. Nevertheless, Jacob confessed his admiration for him.”

As for Pedro Aragão, a bandolim player for forty years — the holder of a doctorate in musicology and a professor at Federal University in Rio de Janeiro, as well as being close to Jacob’s family — he confirms Amorim’s statement by saying, “Yes, it’s true, Jacob is one of those responsible for the mutation in the instrument’s format. Close observation of the form of the Brazilian bandolim shows that it has the shape of a “guitarra portuguesa” in miniature. One shouldn’t forget that Jacob began his career as a musician by playing guitar with a fado group, and by accompanying Portuguese ‘guitarristas’. The way he played was influenced by that sound. The result was that his bandolim “sang” in a way very close to that of the ‘guitarra portuguesa” and it avoided as much as possible the jumpy, hopping sound (‘som picotado’) that was a characteristic of the Neapolitan mandolin.” To add strength to his argument he adds, “Jacob was the creator of the Brazilian sound, of the way the bandolim was played. His way was different from earlier performers, from Luperce Miranda, for example, a very great virtuoso, but his sound didn’t have the quality that Jacob could pull from his instrument.” The personal touches that Pedro Aragão notes in Jacob are important: “He innovated in several things. He always tried to make a legato sound come from an instrument whose normal sound was jerky (‘picotado’); he created embellishments that characterized the choro (appoggiatura, glissando, portamento); and he established a reference (padrão) in the tremolo that was totally different from the Italian: Jacob’s tremolo was much more expressive, because it combined the different speeds with which he used the plectrum. In conclusion, he took greater care in the phrasing of the sound and its expression.” And that was that. All those particularities go to make sure that today’s listener remains fascinated by Jacob’s recordings.

Improvisation

For the music critics of the jazz world the choro lacks an essential, almost existential, dimension: improvisation. The judgement, perhaps peremptory yet one that doesn’t fail to downgrade the genre in their view, deserves a comment because Jacob professed that the choro had to be improvised: in his eyes, this meant that the instrumentalist had to learn the melody of a piece to perfection in order to be capable of developing it. The instrument that takes charge of the leadership without letting go is the solo voice that propels the melody by enhancing it with modulations and embellishments; one could even go so far as to state that the solo instrument is substituted for the absent vocalist; and in this regard, Jacob’s recordings are exemplary. One can add in passing that all the instruments present in a “regional” ensemble — six-string guitar, seven-string guitar, cavaquinho, bandolim and pandeiro, plus flute, clarinet, saxophone, trombone, accordion — are prone to short improvisations over a harmonic sequence.

Let’s go back to Professor Pedro Aragão on this notion of improvisation: “To be truthful, the concept of improvisation is something very broad, and it is often used differently depending on a country’s culture; but with the predominance of jazz, the term has now come to be used in the conception that jazzmen define as improvisation. Clearly, in most choro recordings until the Fifties, it is difficult to find improvisations in the jazz sense; what one encounters are really variations (variações). There are exceptions: Pixinguinha, for example, improvising in ‘Urubu Malandro’. But in most of the choros recorded by both Pixinguinha and Jacob, what you hear are mainly melodic variations. You also have to note that this concept of improvisation can also be extended to other aspects that are not to do with melody: the seven-string guitar (violão 7 cordas) improvises “bass lines”, the cavaquinho improvises “levadas”, etc. This is part of the choro style.” He goes on to add, “Yes, the melodic improvisations are to a much larger extent based on the concept of variations on a theme; this doesn’t mean that improvisation doesn’t exist in the choro. I think that a soloist often doesn’t improvise for technical reasons that have to do with recording limits: a 78rpm record has a duration of three minutes, while the sides of an LP are limited to 36 minutes. But the “home recordings” (caseiros) that we have of Jacob in choro “rodas” show him improvising beautifully according to the jazz definition of the word. But his expression is always in the language of the choro. The record he made of “Chega de saudade” with the Zimbo Trio is also very striking in this sense. It’s very close to what a jazz improviser might play.” Listeners here can find more food for thought in the previously-unreleased take which closes this album, and which dates from 1952: Pixinguinha improvises descants on the tenor saxophone, while Benedito Lacerda improvises on flute and Jacob replies with his bandolim.

The composer

Let’s continue the conversation with bandolim player Pedro Aragão, this time on the subject of composing for the instrument. “As a composer,” he explains, “Jacob combined two important things: a perfect knowledge of the forms of traditional choro, and the attention he paid to the innovations of the Forties and Fifties. He knew perfectly well how to compose using traditional forms and styles like the polkas (Mimosa, Saracoteando), the choro (Reminiscencias) and the schottische (Heroica) while at the same time taking heed of the transformations and influences of the choro in those two decades. You can note several dimensions in the innovations he imported: the incorporation of bolero and samba-canção influences (Falta-me você, Magoas, Entre mil… você, etc.), and those of the samba, as Jacob would become a maestro of the choro-sambado genre in 32 bars, contrary to the 16 bars of the traditional form (Bole Bole, Bola Preta, Gostosinho, etc.) And finally he showed how sensitive he was to the new harmonic forms of pre-bossa nova composers like Garoto or Radames Gnattali (as seen in works like Assanhado, Doce de Coco, Primas and Bordões, etc.)”

Centenary celebrations

It was unthinkable that there would be no commemoration to pay homage to the man who revitalized the choro entirely over the two decades from 1950 to the late Sixties. The Casa do Choro located on the Rua da Carioca in Rio de Janeiro is organizing a week of concerts with several generations of chorões (the Brazilian term for musicians who play the choro.) São Paulo, Brasilia and Recife also have plans for concerts in keeping with the importance of the event. There is the hope that the sound archives donated by Jacob’s daughter will be exploited in their entirety as quickly as possible: they contain moments in which Jacob do Bandolim expressed himself with total freedom, notably in the recordings he made in Brasilia in 1967.

Adapted by Martin Davies from the French text of Teca Calazans and Philippe Lesage

Thanks to Pedro Aragão, Pedro Amorim, Claire Luzi and Cristobal Soto.

© 2018 Frémeaux & Associés

DISCOGRAPHIE JACOB DO BANDOLIM

1 - CONFIDÊNCIAS (Ernesto Nazareth) Jacob do Bandolim com Dino (violão 7 cordas) et Meira (violão 6 cordas). RCA Victor – S-093124 - 1952

2 - FACEIRA (Ernesto Nazareth), Jacob do Bandolim, com Dino ((violão 7 cordas), Meira (violão 6 cordas)- RCA Victor, S-0931221952

3 - DESPERTAR DA MONTANHA (Eduardo Souto) Jacob do Bandolim c/ César Faria, (violão), Fernando Ribeiro (violão 7 cordas) – RCA Victor 80.0602 ; 1949

4 - A GINGA DO MANÉ (Jacob do Bandolim) Jacob e seus Chorões : Jacob ( violinha), Dino (Violão 7 cordas), César, ( violão) Carlinhos ( cavaquinho), Jonas et Gilberto ( ritmos) - RCA LP Primas e Bordões BBL 1190 ; 1962

5 - ASSANHADO (Jacob do Bandolim) Jacob e seu Regional : Dino, César, Carlinhos, Jonas e Gilberto -LP Chorinhos e chorões, RCA BBL.1138, 1961

6 - GRAÚNA (João Pernambuco) Jacob do Bandolim c/ César Faria e seu Conjunto :

César (violão), Fernando Ribeiro, (violão 7 cordas), Pinguim (cavaquinho), Luna (ritmos) – RCA Victor, 80.0702; 1950

7 - NOITES CARIOCAS (Jacob do Bandolim) Jacob e seus chorões (Regional do Canhoto e Metais) – RCA Victor BBL1072- 1960

8 - ODEON (Ernesto Nazareth) Jacob do Bandolim – LP Jacob revive musicas de Ernesto Nazareth ; Jacob, Dino (violão 7 cordas), Meira (violão), Canhoto (cavaquinho), Gilson (pandeiro) RCA Victor BPL 3001 - 1952

9 - TENEBROSO (Ernesto Nazareth) Jacob do Bandolim, Dino (violão 7 cordas) Meira (violão), Canhoto (cavaquinho), Gilson (pandeiro) – RCA VICTOR S-093121 -1952

10 - ATLÂNTICO (Ernesto Nazareth) Jacob do Bandolim com Regional do Canhoto – RCA Victor BP1- 8010901 -1952

11 - SIMPLICIDADE (Jacob do Bandolim) Jacob, Dino (Violão 7 cordas), Meira (violão), Canhoto (cavaquinho), Galhardo filho (contrabaixo), Gilson (pandeiro.) RCA 80.0680 – 1950

12 - MIGALHAS DE AMOR (Jacob do Bandolim) Jacob do Bandolim (violinha), Dino (violão 7 cordas), Meira, (violão) Canhoto (cavaquinho,) Bill (contrabaixo), Gilson (pandeiro), Pingo (reco-reco), RCA Victor, 80.0969 - 1952

13 – O VÔO DA MOSCA (Jacob do Bandolim) Jacob et seus chorões : Dino (violão 7 cordas), César (violão), Carlinhos (cavaquinho), Jonas e Gilberto (ritmos) – LP Primas e Bordões - RCA BBL 1190 -1962

14 - ANDRÉ DE SAPATO NOVO (André Victor Correia) - Jacob do Bandolim e Regional - 78 RPM RCA - 801667 - 1956

15 - BOLA PRETA (Jacob do Bandolim) Jacob et seu Regional : Dino (violão 7 cordas), César (violão), Carlinhos (cavaquinho), Jonas e Gilberto (ritmos) – RCA Victor BBL1138 -1961

16 - FLOR DE ABACATE (Alvaro Sandim) Jacob do Bandolim e seus Chorões (com Regional de Canhoto e metais, Raul de Barros : trombone) – RCA Victor LP Na Roda de Choro RCA BBL.1072 ; 1960

17 - AMAPÁ (Juca Storoni) Jacob e seus chorões (Regional do Canhoto, metais, Raul de Barros : trombone.) LP Na Roda de Choro - RCA BBL1072 -1960

18 - ALVORADA (Jacob do Bandolim) Jacob com Dino (violão 7 cordas) e Meira (violão), Canhoto (cavaquinho), Orlando Silveira (acordeon), Taranto (contrabaixo,) Jorge Silva (pandeiro) e Nelson (reco-Reco) ; RCA Victor 80.1418-1955

19 - COCHICHANDO (Pixinguinha) -Jacob do Bandolim e Regional -78 RPM RCA 80.1845 ; 1957

20 - CHORANDO (Ary Barroso), Jacob do Bandolim e seus Chorões (Regional do Canhoto et metais ) – LP Na Roda de Choro – RCA BBL -1072 ; 1960

21 - PROEZAS DO SOLON (Pixinguinha / Benedito Lacerda) Jacob do Bandolim com seu Regional : Dino (violão 7 cordas), Carlinhos, (violão), Jonas e Gilberto (ritmos) RCA BBL 1138 -1961

22 - RAPAZIADA DO BRAZ (Alberto Marino) Jacob do Bandolim, Canhoto (cavaquinho), Dino (violão 7 cordas), Meira (violão), Orlando Silveira (acordeon), Jorginho (pandeiro), Taranto (contrabaixo.) - RCA Victor BE3 VB-0236, 1953

23 - AGÜENTA SEU FULGÊNCIO (Lourenço Lamartine) Jacob e Seu Regional - RCA 80. 1638 ; 1956

24 - ISSO É NOSSO (Jacob do Bandolim) Jacob com Dino (violão 7 cordas), Meira (violão), Canhoto (cavaquinho), Orlando Silveira (acordeon), Bill (contrabaixo), Jorge Silva (pandeiro) e Barão (afochê) RCA 80.1799 - 1957

25 - GOSTOSINHO (Jacob do Bandolim) Jacob do Bandolim et seus Chorões. (Regional do Canhoto et metais) - LP Na Roda de Choro RCA BBL 1072 – Março1960

26 - TREME TREME (archive inédite ; émission Radio Bandeirantes 1952) Com Jacob do Bandolim et invités : Pixinguinha (saxophone ténor) et Benedito Lacerda (flûte)

JACOB DO BANDOLIM

1 - CONFIDÊNCIAS 3’14

2 - FACEIRA 3’11

3 - O DESPERTAR DA MONTANHA 2’59

4 - A GINGA DO MANÉ 3’03

5 - ASSANHADO 3’05

6 - GRAÚNA 2’53

7 - NOITES CARIOCAS 3’06

8 - ODEON 2’32

9 - TENEBROSO 3’13

10 - ATLÂNTICO 2’60

11 - SIMPLICIDADE 2’46

12 - MIGALHAS DE AMOR 3’08

13 - O VÔO DA MOSCA 3’31

14 - ANDRÉ DE SAPATO NOVO 3’05

15 - BOLA PRETA 3’20

16 - FLOR DE ABACATE 3’12

16 - AMAPÁ 2’56

17 - ALVORADA 3’14

18 - COCHICHANDO 2’46

19 - CHORANDO 3’26

20 - PROEZAS DO SOLON 2’35

21 - RAPAZIADA DO BRAZ 2’47

22 - AGÜENTA SEU FULGÊNCIO 2’45

23 - ISSO É NOSSO 2’23

24 - GOSTOSINHO 2’32

26 - TREME TREME - ARCHIVE INÉDITE AVEC PIXINGUINHA ET BENEDITO LACERDA 2’21