- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

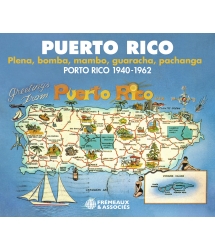

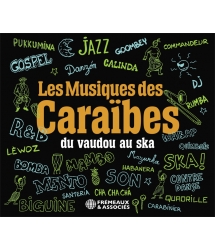

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

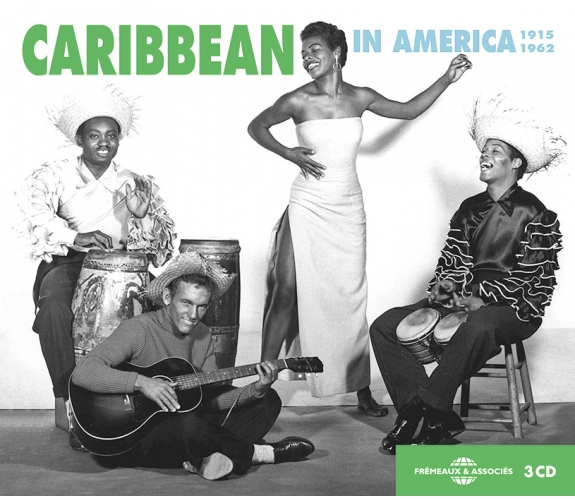

HABANERA, RUMBA, ROCK, MENTO, CALYPSO, JAZZ, MERENGUE, BOMBA, MAMBO, BLUES…

Ref.: FA5664

Artistic Direction : BRUNO BLUM & FABRICE URIAC

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Total duration of the pack : 3 hours 16 minutes

Nbre. CD : 3

HABANERA, RUMBA, ROCK, MENTO, CALYPSO, JAZZ, MERENGUE, BOMBA, MAMBO, BLUES…

HABANERA, RUMBA, ROCK, MENTO, CALYPSO, JAZZ, MERENGUE, BOMBA, MAMBO, BLUES…

The fabulous Caribbean musics — calypso, beguine, merengue and mambo —widely pervaded US music; the makers of which were fascinated by the voluptuous rhythms of their Caribbean neighbours. In search of exoticism, the greatest performers took them up and mixed in their melodies and styles. They incorporated them in extraordinary fusions with jazz, blues and rock, gathered here by Fabrice Uriac and Bruno Blum, who comments on this compelling American introduction to a myriad of Caribbean genres — an initiation to pan-American popular music. Patrick FRÉMEAUX

NEW-YORK, LOS ANGELES, MEXICO CITY, LA HAVANE

DIZZY GILLESPIE • TITO PUENTE • CAL TJADER • MACHITO...

NAT KING COLE • JON HENDRICKS • HARRY BELAFONTE •...

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Bajan GirlLionel BelascoL. Belasco00:02:551915

-

2One LoveMarcus GarveyMarcus Garvey00:00:281921

-

3Trinidad Carnival SongsMonrose's String OrchestraTraditionnel00:02:551923

-

4New Orleans BluesJelly Roll MortonJelly Roll Morton00:02:431923

-

5Sly MongooseSam ManningTraditionnel00:03:051925

-

6Stone Cold Dead In The MarketElla FitzgeraldTraditionnel00:02:451945

-

7Calypso DaddyJeanne DeMetzJohnny Alston00:03:181946

-

8Salee DameAlbert NicholasTraditionnel00:03:261946

-

9Tootie Ma Is A Big Fine ThingDanny BarkerTraditionnel00:03:081947

-

10Cubana BopDizzy Gillespie00:03:201947

-

11BarbadosCharlie Parker00:02:341948

-

12OjaiJoe Lutcher And His Orchestra00:04:081949

-

13Hey Little GirlProfessor Longhair And His New Orleans BoysProfessor Longhair00:03:041949

-

14Carnival DayDave BartholomewDave Bartholomew00:02:491950

-

15Shrinking Up FastCamille HowardFrances Gray00:02:471950

-

16El Mambo DiabloTito Puente And His OrchestraTito Puente00:03:151951

-

17Vibe MamboTito Puente And His OrchestraTito Puente00:03:041951

-

18AmoriosDoris ValladaresSosa Jose00:02:471950

-

19El GalleroDoris ValladaresJuan Pimentel00:02:571952

-

20Un Poco LocoBud Powell00:04:471951

-

21Chee-Koo BabyLloyd PriceLloyd Price00:02:131952

-

22Sly MongooseCharlie ParkerTraditionnel00:03:451952

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Make It DoSlim Gaillard And His OrchestraRay Bloch00:02:541952

-

2La PalomaCharlie ParkerSebastian Iradier00:02:431952

-

3Tell Me Pretty BabyLloyd PriceLloyd Price00:02:201952

-

4Begin The BiguineCharlie ParkerCole Porter00:03:151952

-

5Little School GirlFats DominoFats Domino00:02:401953

-

6Don't Touch Me TomatoMarie BryantTraditionnel00:03:051953

-

7Oh MariaJoe Alexander And The CubansJoe Alexander00:02:471954

-

8YesterdaysCal TjaderJerome Kern00:03:241954

-

9East Of The SunCal TjaderB. Bowman00:03:041954

-

10Don't Touch Me NylonLouis FarrakhanLouis Farrakhan00:02:531954

-

11Is She Is Or Is She Ain'TLouis FarrakhanLouis Farrakhan00:02:311954

-

12GuitaramboMickey BakerMickey Baker00:02:481955

-

13MatildaHarry BelafonteNorman Span00:03:421955

-

14Rhythm Pum Te DumDuke Ellington And His OrchestraDuke Ellington00:02:561956

-

15Trinidad E-OLuis AmandoVan Winkle00:02:031956

-

16Let's Pray For RainLloyd Prince Thomas And The Calypso TrouLloyd Thomas00:02:471956

-

17I'M Goin BackLloyd PriceLloyd Price00:02:251956

-

18St. ThomasSonny RollinsSonny Rollins00:06:491956

-

19Taking A Chance On LoveJosephine PremiceVernon Duke00:01:281957

-

20Mona (I Need You Baby)Bo DiddleyBo Diddley00:02:211957

-

21CalypsocietyHerb JeffriesHerb Jeffries00:02:371958

-

22Mama Look A Boo BooAaron CollinsLord Melody00:02:431957

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1SiestaJosephine PremiceSam Manning00:02:221956

-

2InsideHector AcostaHector Acosta00:02:581957

-

3Brandy In Me TeaRuth WallisRuth Wallis00:03:101957

-

4Magical JoeJeffries HerbHerb Jeffries00:02:341957

-

5Take Me Down To Lover S RowRobert MitchumNeville Marcana00:02:371957

-

6Talk'T MeJosephine PremiceJosephine Premice00:01:371957

-

7A Sad CalypsoWallis RuthRuth Wallis00:02:531957

-

8Run Come See JerusalemWilson StanBlind Blake00:02:481957

-

9Salty Fish, Aki RiceWallis RuthRuth Wallis00:03:031957

-

10Pound Your Plantain In The MortarWilson StanStan Wilson00:03:011957

-

11I Learn A MerengueRobert MitchumDonald Macrae Wilhoite00:03:071957

-

12Two Ladies In De Shade Of De Banana TreeJosephine PremiceH.Arlen00:01:581957

-

13De Gay Young LadJosephine PremiceH.Arlen00:03:091957

-

14Jamaica D.J.Bill HaleyBill Haley00:02:411957

-

15La MaricutanaJose Ernesto ChapuseauxAlfau Radames Reyes00:02:451958

-

16ChicoToussaint AllenToussaint Allen00:02:201959

-

17Afro-BlueCal TjaderMongo Santamaria00:06:351959

-

18Pa Tumbar La CanaCortijo Y Su ComboKito00:02:431960

-

19It Keeps RaininFats DominoFats Domino00:02:491960

-

20Jamaica FarewellSam CookeLord Burgess00:02:341960

-

21White Man's Heaven Is Black Man's Hell Part ILouis FarrakhanLouis Farrakhan00:05:411960

-

22Under The Mango TreeDiana CouplandNorman Monty00:02:241962

Caribbean in America Fa5664

Caribbean in America 1915-1962

Habanera, rumba, rock, mento, calypso, jazz,

merengue, bomba, mambo, blues…

Par Bruno Blum

Où peut-on trouver l’amour, que quelqu’un me le dise

Car la vie doit bien être quelque part

Plutôt que cette jungle de béton où la vie est la plus dure

La jungle de béton, mec, là où tu dois faire de ton mieux.

— Bob Marley, « Concrete Jungle », 1973.

Proches voisins des États-Unis, depuis la nuit des temps les Indiens Taïnos (Arawaks et Caribs) ont circulé dans la mer des Caraïbes. Après 1492 les migrations entre les îles et le continent se sont intensifiées — en particulier dans les grand ports de la Nouvelle-Orléans, Miami et New York — nourrissant les États-Unis de paroles, mélodies, harmonies, danses, musiciens et rythmes venus des Antilles. Nos albums Cuba in America 1939-1962 et Calypso 1944-1958 dans cette collection sont consacrés à l’influence internationale des musiques de Cuba et de Trinité-et-Tobago. Ils sont complémentaires à cette anthologie.

Il est utile de rappeler que la construction d’une identité créole a commencé dès les premières heures de la colonisation des Amériques avec des mélanges entre esclaves africains évadés et Indiens Taïnos des Caraïbes. En Louisiane — sorte d’enclave des Caraïbes sur le continent, un port de culture typiquement caribéenne, propice aux mélanges de populations, cernée par l’eau comme une île et située à la porte d’entrée du continent —, avec les Choctaws et les Apaches Lipan. Sans oublier les Français, les Espagnols, les Portugais et les Anglais. Également importante, la notion selon laquelle la révolution haïtienne a provoqué autour de 1800 la migration de nombreux Antillais francophones à la Trinité et en Louisiane, y apportant notamment la culture animiste haïtienne, sa cosmologie, ses chants et ses rythmes très influents, expliqués dans nos coffrets Haiti Vodou 1937-1962 et Voodoo in America 1926-1962, qui montrent la présence de cette spiritualité créole dans la musique des États-Unis. Des migrations d’esclaves cubains en nombre vers le continent (donc beaucoup de Yorubas), mais aussi de Jamaïcains d’origine ashanti et des migrants d’autres îles ont considérablement imprégné la culture américaine et celles des Afro-Américains en premier lieu. Si le Shrinking Up Fast de Camille Howard en 1950 est bien un titre anticipant le funk des années 1970, l’impact des musiques caribéennes sur la musique populaire des États-Unis ne se limite pas aux racines de ce style, mises en évidence dans notre coffret Roots of Funk1. Notre collection « Caraïbes » montre sans équivoque que l’influence culturelle au sens large, et musicale en particulier, des Antilles sur le continent nord-américain fut à la fois importante, mal comprise et largement sous-estimée, occultée par bien des Américains eux-mêmes. Des chants de travail aux negro spirituals, au jazz, et de la salsa new-yorkaise au rap né en Jamaïque2, les musiques américaines sont indéfectiblement liées à une histoire d’échanges avec les Antilles.

Musique Créole

Faisant allusion à Congo Square où, dès au moins le XVIIe siècle, les esclaves pouvaient jouer leur musique le dimanche au marché de la Nouvelle-Orléans, en 1956 Duke Ellington a consacré un album entier à la présence caribéenne aux États-Unis. Rhythm Pum Te Dum est extrait de A Drum Is a Woman, un éloge du rythme avec son personnage de chamane de la jungle Caribee Joe, dont la reine de beauté noire Madam Zajj tombe amoureuse à la Nouvelle-Orléans.

La musique rythmée était et reste l’un des symboles forts de la culture afro-américaine. Une bonne partie de cette culture s’exprimait spontanément à travers ses chants et rythmes et était donc perçue, à juste titre, comme une affirmation identitaire — donc subversive dans la société raciste des Caraïbes comme du continent. L’importance et l’influence omniprésente des musiques caribéennes aux États-Unis s’expliquent d’abord parce que les cultures africaines étaient strictement interdites et impitoyablement réprimées sur le continent nord-américain au cours de la période de l’esclavage (1492-1865). Puis dans cette même logique d’acculturation, les cultures afro-américaines ont été très dévalorisées pendant le siècle de ségrégation (1865-1964) qui a suivi l’abolition : il fallait ressembler aux Blancs, toute africanité était présumée inférieure, « sauvage » et vécue comme telle par nombre de Noirs. Devenu un complexe, ce préjugé a notamment été combattu dans les années 1910-1930 de la « Harlem Renaissance » par le grand leader noir catholique Marcus Garvey, qui visait d’abord à rendre l’estime d’eux-mêmes aux Afro-Américains (on peut l’entendre ici dans un extrait de discours aux accents de prêche, où il quitte la salle en prononçant les mots « One love », une formule jamaïcaine dont Bob Marley ferait en 1964 l’une de ses plus célèbres chansons). Les Afro-Américains ont utilisé les chants religieux, les negro spirituals, et les temples baptistes, méthodistes, pentecôtistes (etc.) comme vecteurs d’organisation, de culture, et comme façade.

En raison de la répression, l’impact des cultures africaines en provenance directe d’Afrique était réduit, caché et peu visible. Une présence culturelle africaine en Amérique du Nord n’a, en bonne partie, été rendue possible que grâce à la persistance de populations caribéennes qui parvenaient tant bien que mal à pérenniser des éléments de leurs cultures ancestrales — qu’elles ont ensuite apportés aux États-Unis (le vibraphone entendu sur les titres de Tito Puente et Cal Tjader est par exemple un héritage du balafon ouest-africain). Appelées « créoles », des fusions culturelles Afrique-Europe existaient bel et bien : l’identité créole était propre aux Amériques, un mélange nouveau, bien distinct de ses origines outre atlantiques. Si la créolité était en principe synonyme d’une culture imposée par les esclavagistes — c’est à dire éradiquant toute survivance de cultures africaines — en réalité elle laissait un espace à la négritude, elle tolérait une part de différence, un lien avec l’Afrique et ses cultures tant méprisées.

La créolité a pu mieux se développer dans des lieux comme la Jamaïque, la Martinique, Cuba, la Nouvelle-Orléans et ailleurs aux Antilles. À la Nouvelle-Orléans comme aux Caraïbes, les créoles implantés depuis le début de la traite négrière étaient souvent plus conscients de leurs racines, de leur identité à part et de la valeur de leur culture. Et surtout, ils avaient de l’expérience pour mieux la préserver. En cela, ils étaient souvent plus enclins à la résistance, à la revendication, à l’exigence éthique que les descendants d’Africains implantés plus au nord du continent et qui avaient été acculturés plus brutalement encore car la répression s’est accentuée avec le temps. Les racines créoles et l’identité caribéenne étaient aux États-Unis comme un symbole de résistance : ils étaient le fait de gens plus noirs, plus véhéments, plus proches spirituellement de l’Afrique originelle, plus subversifs, plus craints car souvent plus enclins à mettre en valeur leur culture. Leur rôle est donc crucial dans l’évolution des mentalités qui a pris place au XXe siècle, où la ségrégation raciale prévalait. Comme les Haïtiens, les Jamaïcains étaient particulièrement rétifs à l’oppression, mais cette force intérieure était répandue dans tout le bassin caribéen. La musique et la danse étaient des éléments essentiels de ces cultures : elles représentaient de rares instants de libération du corps et de l’esprit.

C’est sur un rythme caribéen qu’Albert Nicholas chantait en patois français le très créole Salee Dame en 1946, avant que cette langue symbolique de la créolité états-unienne originelle ne disparaisse presque complètement de la Louisiane dans la seconde moitié du XXe siècle. Fats Domino, la première superstar du rock, était également un fier créole francophone de Louisiane né d’une mère d’origine haïtienne (et indienne). Logiquement, l’immense popularité de sa musique était liée à la puissance culturelle intrinsèque de son art, à la synthèse créole qu’il incarnait. Or cette créolité a pu se cristalliser de façon significative dans des îles éloignées où la population d’origine africaine était très majoritaire (plus de 90%). De plus aux États-Unis, où les populations afro-américaines étaient très minoritaires (moins de 15% de la population), l’oppression et l’acculturation étaient des obsessions en raison de la peur des révoltes d’esclaves, qui pouvaient s’unir et se révolter s’ils parvenaient à structurer secrètement leur résistance (en 1811, plus de cinq cents esclaves haïtiens se révoltèrent et furent massacrés en Louisiane). Ce qu’ils firent d’ailleurs en utilisant par exemple les paroles codées des chansons de negro spirituals3.

La présence des negro spirituals, puis du gospel, le succès du ragtime puis du jazz, du blues rural, du blues urbain et du rock n’ont pour l’essentiel été rendus possibles que par des circuits noirs séparés, presque inaccessibles au grand public qui en était sciemment écarté. Ces réseaux étaient néanmoins fréquentés par des Blancs ouverts, passionnés par ces musiques afro-américaines (lire les livrets et écouter nos coffrets Beat Generation 1936-1962 et Elvis Presley face à l’histoire de la musique américaine 1954-1956 dans cette collection).

L’oppression et la ségrégation culturelle étaient obligatoires et endémiques : à quelques exceptions près, les musiques afro-américaines jugées vulgaires et subversives ont été écartées de la radio américaine jusqu’à la fin des années 1940, comme en témoigne notre coffret Race Records - Black Rock Music Forbidden on U.S. Radio 1942-1955, qui documente avec précision les véritables premières années du rock.

Protestation

À la charnière des XIXe et XXe siècle, les premiers leaders afro-américains (l’ancien esclave Booker T. Washington et le métis du nord W. E. B. Du Bois, premier « Noir » sorti de Harvard) étaient des intellectuels. Avocats de la culture et de l’éducation, ils cherchaient le compromis dans le but de libérer leur peuple. Après ces personnages historiques, ce n’est pas un hasard si le premier grand leader nationaliste noir radical des États-Unis, le très combatif Marcus Garvey (United Negro Improvement Association), un catholique actif entre les deux guerres, était jamaïcain4. Parmi ses adeptes on trouvait Elijah Muhammad, qui devint par la suite le dirigeant de la Nation of Islam (un dérivé américanisé de l’Islam où le culte de la personnalité du leader tenait une grande place), ainsi que le populaire membre de la NOI Malcolm X (dont la mère était née à la Grenade) et Louis Farrakhan (de père jamaïcain, sa mère était née aux îles Saint Kitts and Nevis et son père adoptif était originaire de la Barbade), qui rejoint la NOI en juillet 1955 avant d’en prendre la direction vingt ans plus tard. Par contraste avec ces nationalistes noirs ancrés à droite, Martin Luther King, grand artisan du Mouvement des Droits Civiques dans les années 1955-1968, était un baptiste de parents états-uniens; majoritaire, bien plus nuancé, il était au contraire consensuel et partisan de la non-violence, s’alliant à des artistes de gauche, pacifistes comme Harry Belafonte, Josh White, dont des Blancs Bob Dylan ou Joan Baez5. En revanche Farrakhan, deviendrait très controversé pour ses déclarations racistes et antisémites. Violoniste de formation, il avait aussi été un artiste de calypso en 1953-1955 sous le nom de Calypso Gene The Charmer. Ainsi, avant de devenir un acteur significatif du puritanisme américain en mode « black muslim », il avait enregistré des chansons coquines de grande qualité dans la veine calypso comme Don’t Touch Me Nylon et Is She Is, Or Is She Ain’t, une chanson homosexiste décrivant un travesti dans la ricanante tradition homophobe caribéenne6. Six ans plus tard, c’est sous le nom de Louis X qu’il enregistra A White Man’s Heaven Is A Black Man’s Hell, un 45 tours de calypso dénonçant les crimes de l’esclavage, de la colonisation — et invitant à rejoindre le mouvement d’Elijah Muhammad dont il était devenu militant.

La négritude chère aux intellectuels C. L. R. James, Édouard Glissant et Aimé Césaire comme au tribun populiste Garvey a de tous temps trouvé une expression forte aux Antilles. Aux Caraïbes mêmes, les musiques locales ont certes été marginalisées, réprimées puis longtemps boycottées par les radios locales au profit des cultures coloniales, mais elles étaient fortement implantées dans la population noire majoritaire et représentèrent finalement un atout pour l’industrie touristique naissante de l’après-guerre. Cet aspect touristique n’excluait pas l’authenticité et la qualité, ce que reflètent les disques vendus en souvenir aux touristes (lire les livrets et écouter Jamaica - Mento 1951-1958 et Bahamas - Goombay 1951-1959 dans cette collection). Ces brillantes chansons créoles, sans doute la forme d’expression la plus significative des Antillais, sont ainsi arrivées par différents moyens jusqu’au continent. Elles ont apporté avec elles leurs rythmes, comme la habanera cubano-haïtienne omniprésente dans cet album, leurs danses et leur attitude.

Calypso, Trinité et Îles Vierges anglophones

Le jazz américain, dont le lieu de naissance est attribué à la Nouvelle-Orléans, était en fait la forme états-unienne d’une musique pan-caribéenne rythmée, présente dans tout le bassin des Caraïbes à la charnière des XIXe et XXe siècle et plus tôt encore. À partir de 1917, avec les orchestres, les disques de jazz et de blues états-uniens, la musique du sud des États-Unis a marqué les Caraïbes, notamment Saint-Domingue, Porto Rico, la Jamaïque, Trinité-et-Tobago et Cuba. Des musiciens de jazz caribéen étaient présents à Cuba, à Saint-Domingue, à Kingston, à Paris, à Londres, à New York7…

« [Tricky Sam] jouait une forme très personnelle de son héritage antillais. Quand un type des Antilles vient ici et qu’on lui demande de jouer du jazz, il joue ce qu’il pense être du jazz, ou une chose qui résulte de sa volonté de se conformer à cet idiome. Tricky et son peuple étaient à fond dans le mouvement des Antilles et de Marcus Garvey. Tout un pan de musiciens antillais ont surgi et contribué à ce qu’on appelle le jazz. Ils descendaient virtuellement tous de la véritable scène africaine. C’est la même chose avec le mouvement musulman, il y a beaucoup d’Antillais qui en font partie. On y trouve beaucoup de points communs avec les projets de Marcus Garvey. Comme je l’ai déjà dit une fois, le bop est le prolongement de Marcus Garvey. »

— Duke Ellington évoquant son tromboniste « Tricky Sam » Nanton8

Inversement, des enregistrements caribéens ont été gravés très tôt et ont touché les États-Unis. Des disques de musiciens afro-caribéens de la Trinité ont été enregistrés à New York et diffusés dès 1912 (Lovey’s Trinidad String Band) : le pianiste juif sépharade issu d’un métissage avec une créole de la Trinité Lionel Belasco (ici dans Bajan Girl, une de ses compositions gravée en 1915 dans le style ragtime, évoquant une fille de la Barbade où il était né), son ami Sam Manning et le Monrose’s String Orchestra étaient des habitués des concerts à New York et y ont beaucoup enregistré. Cet échange musical constant entre continent et îles était particulièrement significatif dans le domaine des musiques afro-américaines créoles, qui mélangeaient les influences européennes et africaines. À leur tour, leurs disques caribéens ont influencé le continent. Comme dans le jazz américain de l’époque, certains de ces artistes improvisaient déjà de façon informelle, comme on peut l’écouter dans le Trinidad Carnival Songs du violoniste trinidadien Cyril Monrose enregistré à New York en 1923. Lloyd Prince Thomas était un interprète de calypso très marqué par les disques de la Trinité-et-Tobago, mais il était originaire des Îles Vierges américaines. Menés par le pianiste et compositeur des Îles Vierges Bill LaMotta, les LaMotta Brothers jouaient du calypso trinidadien qu’ils mélangeaient au style quelbe local, mais ils ont aussi enregistré du merengue, la musique voisine de Saint-Domingue (comme ici sur Let’s Pray For Rain de Lloyd Prince Thomas). Ce sont encore des musiciens des Îles Vierges, les Fabulous McClevertys, qui ont accompagné The Charmer, le futur leader de la Nation of Islam sous le nom de Louis Farrakhan (lui même de parents antillais), dans sa période de chanteur de calypso de 1953-1955. Les parents du grand saxophoniste new-yorkais Sonny Rollins étaient originaires des Îles Vierges; la composition la plus célèbre de ce géant du jazz est sans doute St. Thomas, inspirée par la plus grande de ces îles — et ses rythmes. Bien que situées au cœur des Antilles, les Îles Vierges sont un territoire américain (comme Porto Rico) qui a contribué à diffuser les musiques des Caraïbes aux États-Unis. Notre coffret Virgin Islands - Quelbe & Calypso 1956-1960, qui contient de savoureuses chansons vaudou, leur est consacré dans cette collection.

Cuba à la Nouvelle-Orléans

Une forte immigration d’esclaves haïtiens et de leurs voisins cubains a eu lieu au fil du XIXe siècle, apportant avec eux des versions dansantes, syncopées, créoles des musiques populaires françaises et espagnoles du XVIIIe siècle. Selon le grand pianiste de jazz de la Nouvelle-Orléans Jelly Roll Morton, au début du XXe siècle le jazz se déclinait en trois styles : le stomp, le blues et la Spanish tinge (« couleur espagnole »), c’est à dire le balancement syncopé de la habanera jouée à la main gauche, entendue sur un de ses blues en solo enregistré en 1923 :

« Dans l’un de mes premiers morceaux, New Orleans Blues, vous pouvez remarquer une couleur espagnole [cubaine, NDA]. Si vous n’arrivez pas à mettre ces teintes espagnoles dans vos morceaux, vous ne parviendrez pas à obtenir ce que j’appelle le bon assaisonnement pour le jazz. » — Jelly Roll Morton

En fait le musicien — dont une partie de la famille était haïtienne — faisait allusion non à l’Espagne mais aux rythmes tresillo et habanera entendus dans la contradanza cubaine, que l’on retrouve aussi dans les bases de la meringue franco-haïtienne et du merengue dominicain voisins9. En effet dès le début de l’industrie du disque, une présence cubaine/haïtienne a habité la musique de la Nouvelle-Orléans (rythme habanera sur l’intro de l’essentiel « St. Louis Blues » par Louis Armstrong en 1929 par exemple)10. La habanera est par exemple entendue distinctement jouée par la main gauche (les notes de piano grave) de Professor Longhair sur Hey Little Girl, gravé à la Nouvelle-Orléans en 1949. Comme des millions d’Africains-Américains, Jelly Roll a émigré vers le nord où l’influence musicale du sud se propageait. Le jazz des créoles noirs de Louisiane, qui était parfois encore francophone jusqu’aux années 1950, utilisait des rythmes venus de Haïti, du vaudou, des Caraïbes, comme ici la rumba cubaine de Danny Barker (Tootie Ma Is a Big Fine Thing) et d’Albert Nicholas (habanera sur Salee Dame) avec le batteur Baby Dodds, l’un des fondateurs du jazz.

Sur Carnival Day en 1950, le trompettiste et chanteur de la Nouvelle-Orléans Dave Bartholomew évoque le roi des Zoulous (Zulu King) du carnaval du Mardi-Gras, une tradition apportée aux Amériques par les Français. On y retrouve la habanera, jouée à la basse, et le rythme de tibois (la clave, deux morceaux de bois frappés l’un contre l’autre) caractéristiques de la rumba cubaine. Ce rythme de percussion joué au tibois/clave était joué à la guitare par Bo Diddley, qui le mélangeait à un chant très influencé par les negro spirituals qu’il chantait enfant. Né dans le Mississippi pas loin de la Nouvelle-Orléans, Bo Diddley a emporté avec lui cette portion de culture afro-cubaine à Chicago, où en jouant ce rythme sur une guitare il a créé un style original qui a considérablement influencé la musique américaine et mondiale, de Johnny Otis aux Doors et des Who aux Rolling Stones, qui ont enregistré une version de Mona pour leur premier album11.

Dave Bartholomew est vite devenu l’arrangeur et réalisateur artistique à succès des fondateurs du rock que furent Fats Domino, Lloyd Price et Little Richard; Le rythme habanera est tout aussi fondamental dans leurs Chee-Koo Baby, Little School Girl, Tell Me Pretty Baby et I’m Goin’ Back, enregistrés avec la même équipe et dans le même studio J&M à la Nouvelle-Orléans12. On y entend les mêmes roulements de tambour que sur le célèbre « What’d I Say » de Ray Charles : le rythme de la rumba cubaine, normalement jouée sur les congas. Dans une réminiscence des danses européennes du siècle précédent, comme transmutées, sur Chico le jeune Allen Toussaint (l’un des futurs fondateurs du funk) emprunte un groove de rumba, injecte une habanera à la basse et des triolets au piano, signature du style de Fats Domino. Des variantes expérimentales de ces rythmes cubains/haïtiens/portoricains ont été incorporées comme par magie à divers styles américains : Ojai par l’orchestre « jump blues » de Joe Lutcher, une pure habanera sur Calypso Daddy de Jeanne DeMetz, Make It Do du bopper excentrique Slim Gaillard à New York… même la danseuse et chanteuse de blues de la Nouvelle-Orléans Mary Bryant interprète Don’t Touch Me Tomato sur un rythme habanera. Ce classique pan-caribéen (jamaïcain ?) fut également enregistré par Josephine Baker et « la première chanson que [mon fils] a chanté » racontait Cedella, la mère de Bob Marley. Cette adaptabilité montre à quel point habanera et rumba sont au cœur de la culture afro-américaine pan-caribéenne, du ragtime au blues, du rock jusqu’au jazz. D’autres rythmes d’origine africaine, notamment restés présents en Jamaïque13, à Cuba et dans le vaudou haïtien, que l’on retrouve décryptés dans notre volume d’enregistrements de terrain Haiti Vodou 1937-1962, ont fait surface aux États-Unis sous différentes formes et se sont mélangés aux mazurka, polka, boléro, valse, quadrille et nombre d’autres traditions d’origine européenne. Ainsi était le processus de créolisation aux Antilles.

Jazz Cubano-Américain & Merengue

Après différents épisodes d’occupation, de colonisation et de protectorats par les États-Unis, Saint Domingue, Porto Rico, Haïti et Cuba étaient sous domination économique américaine (tourisme, commerce). Dans les années 1930, plusieurs orchestres de La Havane avaient adopté le jazz américain: citons les orchestres de Hermano Castro, formé en 1929, puis ceux de René Touzet, Armando Romeu, Hermanos Palau, Casino de la Playa avec le chanteur Miguelito Valdés, remplacé par Orlando « Cascarita » Guerra; ou encore l’Orquesta Riverside avec le célèbre Tito Gómez dans les années 195014. Le jazz américain était également répandu dans les hôtels et cabarets de Jamaïque15. Cette forte influence américaine renforçait la tendance à l’improvisation et à la sophistication des arrangements, que l’on retrouvait aussi dans la meringue haïtienne et le merengue dominicain. Elle évolua vers une approche jazzy, débridée, de la musique cubaine qui donna finalement naissance aux éblouissantes Cuba Jam Sessions improvisées sur des mélodies et rythmes strictement cubains en 195716. Puis à son tour, Cuba a marqué le jazz américain avec l’adoption de rythmes et musiciens cubains par les géants du jazz, d’abord abondamment avec Duke Ellington (ici dans Rhythm Pum Te Dum) dont deux des trombonistes, « Tricky Sam » Nanton et Juan Tizol (compositeur de « Caravan ») étaient caribéens. Stan Kenton, Dizzy Gillespie (Cubana Bop, 1947), Charlie Parker (Barbados, 1947) comptent parmi les précurseurs du recours aux arrangements caribéens dans le jazz.

Dès 1950, alors que les premiers succès rock de Fats Domino arrivaient de la Nouvelle-Orléans, un engouement pour les musiques latines cubaine, portoricaine et dominicaine a déferlé sur tout le continent et au-delà (mambo, cha cha chà, plena, merengue, bomba…). En 1950, l’orchestre dominicain de l’accordéoniste Angel Viloria, fixé à New York, connut un grand succès dans la communauté portoricaine défavorisée avec son merengue, musique de danse par excellence (Amoríos, El Gallero) où le saxophoniste Ramón E. García rivalisait de virtuosité avec les meilleurs jazzmen. À la fin de sa courte vie Charlie Parker persévéra avec des arrangements caribéens, appliqués à la chanson espagnole La Paloma, au standard de Cole Porter Begin the Beguine (la biguine est un style des Antilles françaises) en 1952 et bien d’autres titres. Le vibraphoniste américain blanc Cal Tjader adopta le mambo et arrangea des compositions américaines dans ce style (Yesterdays, East of the Sun, 1954), engageant des musiciens cubains comme Willie Bobo et Mongo Santamaría (le compositeur du classique Afro Blue). Bud Powell (Un Poco Loco, 1951), Sonny Rollins (St. Thomas, 1956) et Mickey Baker (Guitarambo, 1956) extrapolèrent avec d’indéfinissables rythmes caribéens hybrides.

Porto Rico, USA

Comme les Îles Vierges américaines toutes proches, l’île de Porto Rico est un territoire des États-Unis situé au cœur des Caraïbes, un lieu d’évasion fiscale et une destination touristique. Confinés à un statut colonial — ses citoyens ne votent pas aux élections présidentielles des États-Unis —, contrairement à beaucoup d’autres Caribéens qui rêvent de rejoindre Miami, trois millions et demi de Portoricains peuvent néanmoins circuler sur le continent (voir la comédie musicale West Side Story, qui décrit cette ambiguïté territoriale dans la communauté portoricaine de New York). Une importante population portoricaine hispanophone est ainsi implantée en métropole, principalement à New York, et constitue un public de choix pour toutes les musiques latines. Dans les années 1950 elle formait le gros des amateurs de merengue dominicain, de mambo, de son et cha cha chá cubain, etc. Porto Rico fut le cheval de Troie qui permit aux musiques latines de s’introduire sur le continent. Né à Harlem de parents portoricains, le percussioniste et vibraphoniste Tito Puente devint dès 1949 l’un des géants du mambo cubain avec de remarquables enregistrements où l’improvisation tenait une grande place (ici El Mambo Diablo et Vibe Mambo); comme le Cubain Machito avant lui, il engagea les meilleurs musiciens de la diaspora des Caraïbes latines, affirmant une présence marquée de ces musiques sur le sol du continent, où elles évoluèrent bientôt vers la salsa sous l’impulsion de musiciens portoricains comme Johnny Pacheco, et en se mélangeant au merengue dominicain. Les musiques cubaines avaient du succès dans tous les pays hispanophones du bassin, de la Colombie au Vénézuela, au Mexique et jusqu’à Miami, Los Angeles et New York. Francisco Alberto Simó Damirón, un pianiste dominicain, avait élu domicile à Porto Rico. Marqués par les arrangements sophistiqués à l’américaine et la richesse rythmique cubaine, Damirón y Chapuseaux se produisaient fréquemment sur le continent, où ils ont participé à populariser le merengue de leur pays.

Nombre de musiciens portoricains de stature internationale se sont aussi fait connaître à New York, notamment Eddie Palmieri, Tito Puente (qui après le mambo a diversifié son répertoire latin) et le légendaire Cortijo y su Combo avec Ismael Rivera au micro avec au piano Rafael Ithier, futur fondateur du célèbre groupe de salsa El Gran Combo. Rafael Cortijo était en 1955-1962 le roi de la bomba moderne (nom d’un rythme traditionnel portoricain que l’on retrouve aussi à Haïti17) dont Pa’ Tumbar la Caña est un bel exemple, et de la plena, des styles très dansants hérité des rythmes portoricains traditionnels, proches mais distincts du merengue dominicain et du konpa haïtien voisins. Il était lui aussi très influencé par le mambo cubain (arrangements de vents) et se produisait souvent sur le continent. Comme celui de Tito Puente, l’orchestre de Cortijo avait adopté les irrésistibles rythmes cubains pendant son âge d’or, qui s’est brutalement achevé en 1962 avec l’incarcération d’Ismael Rivera pour détention de drogues.

Calypso & mento jamaïcain

L’acclimatation de la chanson caribéenne « typique » avait commencé dans le jazz et la variété internationale dès les années 193018. Cette vague d’exotisme a notamment inspiré des chansons coquines aux savoureux double sens et métaphores sexuelles (les « hokum records » américains) que l’on trouvait en abondance dans le mento jamaïcain et le calypso trinidadien. Ces chansons étaient liées aux fantasmes de prostitution, de mœurs et de tenues légères qu’évoquaient alors la rumba cubaine, le merengue dominicain, les musiques latines venues de Porto Rico et les îles au climat tropical où les bases militaires américaines — et les hôtels de passe afférents — étaient répandus. En un mot, les tropiques évoquaient principalement le tourisme sexuel, le soleil et la plage; à l’exception de quelques chansons folkloriques de critique du colonialisme comme « Brown Skin Girl » et plusieurs negro spirituals, le militantisme noir libérateur des esprits, notamment des rastafariens comme Bob Marley inspirés par Marcus Garvey, n’avait pas encore pris une grande place dans la chanson populaire. White Man’s Heaven Is a Black Man’s Hell de Farrakhan est un exemple notable de chanson contestataire, mais elle provenait d’un intellectuel de Boston et non des Antilles mêmes — et n’a pas eu grand impact. Néanmoins la mélodie de Sly Mongoose, une chanson jamaïcaine d’auteur inconnu, avait été enregistrée par Lionel Belasco en 1923 mais la première version avec paroles, gravée à New York par le Trinidadien Sam Manning, date de 1925. Elle met en scène une mangouste, symbole de l’échec de la colonisation (les rusées [« sly »] mangoustes avaient été importées d’Inde par les anglais pour éradiquer les serpents en Jamaïque, mais elles dévastaient les poulaillers de toute l’île). Y faire allusion était une façon insolente de se moquer des puissants comme ici Alexander Bedward, un prédicateur très suivi au début du XXe siècle en Jamaïque, qui baptisait les gens par centaines dans une rivière. Bedward, un défenseur de la cause noire anticoloniale, fut l’un des inspirateurs du mouvement Rastafari jamaïcain né vers 1932. Sa fille est ici séduite par un journaliste (nommé « Mangouste ») qui emmène une de ses « plus grosses poules » se faire baptiser dans une autre eau bénite.

Mangouste, un reporter des journaux

A emmené Bedward [prononcer « bed with » = au lit] la fille du prédicateur

L’a baptisée dans son eau bénite

Glisse mangouste

La mangouste a été dans la cuisine de Bedward

A pris une de ses plus grosses poules

C’est pour ça qu’il a quitté la Jamaïque

La mangouste (le journaliste) fuit alors la Jamaïque pour Cuba, et arriva aux États-Unis où elle devint célèbre. Charlie Parker jouait une version instrumentale de ce mento emblématique de la Jamaïque. Un de ses concerts enregistré en 1952 le révèle (disque 1), mais il citait déjà une partie de cette mélodie dans sa version de « 52nd Street Theme » du 17 décembre 1945.

Avec le grand succès « Rum and Coca-Cola » des Andrew Sisters en 1944 (une reprise du Trinidadien Lord Invader), qui fait allusion à la prostitution, le calypso a trouvé sa place aux États-Unis. Il était en phase avec le nouvel élan touristique rendu possible par le développement de l’aviation civile et la vogue d’exotisme de l’après-guerre (écouter notre album Calypso consacré à l’internationalisation de la musique de Trinidad en 1944-195819). Dès la fin des années 1940, l’excellente chanteuse de cabaret Ruth Wallis, déjà spécialiste des chansons coquines dans ses spectacles, a adopté les musiques des îles qui correspondaient à son image de femme blanche très libérée, libertine, souvent perçue comme immorale. Femme d’affaires mûre, talentueuse et sûre d’elle, Wallis contourna les réticences des maisons de disques en créant sa propre marque avec succès, produisant des albums remarquables. Accompagnée par de grands musiciens comme Jimmy Carroll, elle a ainsi composé et interprété nombre de disques aux paroles osées et aux doubles sens sans équivoque.

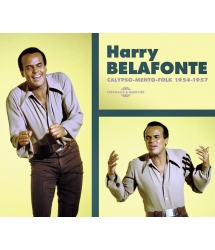

Mais c’est bien sûr le new-yorkais d’origine jamaïcaine Harry Belafonte qui a véritablement lancé la grande vogue du calypso en 1956 avec sa reprise d’une chanson du trinidadien King Radio, Matilda (dont la mélodie est la même qu’une chanson jamaïcaine traditionnelle, le mento « Sweetie Charlie »20). Paru peu après, son splendide album Calypso a été consacré premier disque d’or de l’histoire des États-Unis. Le beau et charmant chanteur de folk est instantanément devenu une vedette internationale, rivalisant de succès avec Fats Domino et Elvis Presley. Proche de Martin Luther King, il s’est aussitôt affirmé comme l’un des militants du Mouvement pour les Droits Civiques les plus en vue — et un symbole sexuel noir. L’étiquette « calypso » trinidadien était vendeuse mais son album contenait en fait des chansons traditionnelles jamaïcaines, des mentos revus et corrigés par son associé Irving Burgie (dit Lord Burgess), qui les a débarrassés de leur rugosité — et de tous leurs doubles sens graveleux, leur préférant une évocation charmante de la dignité noire. La popularité de Belafonte a déclenché un déluge de disques de « calypso ». Tous les artistes de mento jamaïcains et des dizaines de chansonniers noirs jusque-là ignorés, des Bahamas à la Trinité, ont brusquement été enregistrés par différentes marques à l’affut de succès. À New York, les disques Monogram de Manny Warner ont publié nombre de productions des Caraïbes latines et anglophones. Plusieurs artistes états-uniens se sont à leur tour essayés aux chansons caribéennes, à commencer par Ruth Wallis dont quatre extraits de l’album Saucy Calypso de 1957 sont inclus ici. Toujours avec humour et élégance, elle osait des chansons sur le désir féminin (Brandy in me Tea), l’homosexualité (De Gay Young Lad), la prostitution (Salty Fish, Aki Rice qui fait allusion au plat national jamaïcain et à la chanson traditionnelle jamaïcaine « Big Bamboo ») et l’infidélité (A Sad Calypso), des thèmes tabous dans les États-Unis puritains de Truman et Eisenhower. D’autres continentaux ont enregistré du mento, dont Luis Amando, Herb Jeffries et Hector the Ram. Sans oublier le grand chanteur de gospel et de soul Sam Cooke dans une version douce d’un grand classique de Belafonte, Jamaica Farewell (dont la version traditionnelle jamaïcaine s’appelle en fait « Iron Bar »21). Le chanteur des Cadets (« Stranded in the Jungle ») Aaron Collins a publié en 1957 un album solo intitulé Calypso USA d’où est extrait ici le traditionnel Mama Look a Boo Boo, un titre décrivant un père de famille dont les enfants disent qu’ils ne peuvent pas être leur père car il est bien trop laid. Une fois enquête menée en prenant sa femme en filature, le père réalise que le père des enfants est en fait son laid voisin. La vedette de cinéma Robert Mitchum l’a également enregistré par pour son album à succès Calypso… Is Like So la même année, d’où sont extraits Take Me Down to Lover’s Row (où il se laisse séduire par une jeune femme de la bonne société) et I Learn a Merengue. Avec un double sens caractéristique, sur Plant Your Plantain in the Mortar, une chanson sur la séduction par la bonne cuisine, le chanteur folk de San Francisco Stan Wilson fait allusion à l’infidélité et au docteur Alfred Kinsey (« Lord Kinsey ») dont les travaux sur la sexualité choquaient alors l’Amérique. Il reprend également Run Come See Jerusalem (qui relate un dramatique naufrage) de la vedette des Bahamas Blind Blake22.

Deux albums particulièrement remarquables sont apparus en 1957, magnifiquement interprétés par une Américaine ayant grandi à Haïti, la belle Josephine Premice, une actrice de Broadway dont quatre titres délicieux sont inclus ici : Siesta, Taking a Chance on Love, Talk to Me et Two Ladies in the Shade of de Banana Tree23.

Alors qu’avec Jamaican D.J. en 1960 Billy Williamson le steel guitariste de Bill Haley interprétait un rock décrivant un DJ Jamaïcain qui préférait le rock au calypso (dont la mode en 1957 était supposée détrôner le rock), Fats Domino, l’un des véritables fondateurs du rock dès 1950 et une grande vedette en Jamaïque, inspirait à nouveau les Caraïbes. Avec son shuffle de piano, son It Keeps Rainin’ de 1960 annonçait de façon troublante un son aérien caractéristique du reggae — qui ne naîtra pourtant à Kingston que des années plus tard. Terminons avec la bande originale du premier film de James Bond, Dr. No, dont les plans extérieurs ont été tournés à Oracabessa en Jamaïque, où de rares images de carnaval jamaïcain traditionnel ont par ailleurs été capturées. C’est le Jamaïcain Chris Blackwell, futur producteur de Bob Marley, qui en tant que conseiller au repérage suggéra à la production d’employer le grand guitariste jamaïcain de jazz Ernest Ranglin pour accompagner Diana Coupland, une chanteuse britannique dont le Under the Mango Tree fut entendu des millions de fois dans ce célèbre film britannique, un succès mondial des années 1960.

Bruno Blum, novembre 2016.

© FRÉMEAUX & ASSOCIÉS 2017

Merci à Francis Blum, Yves Calvez, Stéphane et Jean-Michel Colin, Christophe Hénault, Herbert Miller, Gilles Pétard, Gilles Riberolles, Frédéric Saffar, Soul Bag, Nicolas Teurnier et Fabrice Uriac.

1. Lire le livret et écouter Roots of Funk 1947-1962 (FA 5498) dans cette collection.

2. Lire Bruno Blum, Le Rap est né en Jamaïque, le Castor Astral, Paris, 2009.

3. Lire le livret et écouter Slavery in America, Redemption Songs 1914-1972, musiques issues de l’esclavage aux Amériques (FA 5498) dans cette collection.

4. Des enregistrements de la voix de Marcus Garvey sont disponibles dans Africa in America 1920-1962 (FA 5397), Slavery in America - Redemption Songs 1914-1972 (FA 5467) et The Color Line, les artistes africains américains et la ségrégation 1916-1962 (FA 5654) dans cette collection.

5. Lire le livret et écouter The Indispensable Joan Baez 1959-1962 (FA 5659) dans cette collection.

6. Une autre chanson calypso satirique sur l’homosexualité intitulée « Romeo » par Lord Kitchener figure sur le volume Trinidad and Tobago - Calypso 1939-1959 (FA 5348) dans cette collection.

7. Lire les livrets et écouter Jamaica Jazz 1931-1962 (FA 5636) et Swing Caraïbe, premiers jazzmen antillais à Paris 1929-1946 (FA 069) dans cette collection.

8. Extrait de l’autobiographie de Duke Ellington, Music Is my Mistress (Doubleday, Garden City, N.Y., 1973).

9. Lire le livret et écouter Haiti - Meringue & Konpa 1952-1962 (FA 5615) et Dominican Republic Merengue 1949-1962 (FA 5450) dans cette collection.

10. Une grande partie de l’œuvre de Louis Armstrong est disponible dans cette collection.

11. Lire le livret et écouter The Indispensable Bo Diddley 1955-1960 (FA 5376) et vol. 2 1959-1962 (FA 5406) dans cette collection.

12. Lire le livret et écouter les six disques de The Indispensable Fats Domino 1949-1962 à paraître dans cette collection.

13. Lire le livret et écouter Jamaica - Trance Folk Possession, Roots of Rastafari 1939-1961 (FA 5384) en coédition avec le Musée du Quai Branly dans cette collection.

14. Maya Roy, Musiques Cubaines, Actes Sud/Cité de la Musique, 1998. Édition anglaise : Cuban Music (Latin America Bureau, Londres, 2002).

15. Lire le livret et écouter Jamaica Jazz 1931-1962 (FA 5636) dans cette collection.

16. Cuba - Jam Sessions à paraître dans cette collection.

17. Lire le livret et écouter « Bumba Dance » sur Haiti Vodou 1937-1962 (FA 5626) dans cette collection.

18. Lire le livret et écouter Amour bananes et ananas - anthologie de la chanson exotique 1932-1950 (FA 5079) dans cette collection.

19. Lire le livret et écouter Calypso (FA 5342) dans notre coffret Anthologie des musiques de danse du monde avec les Andrew Sisters, Lord Kitchener, Josephine Premice, Robert Mitchum, Lord Flea, Blind Blake, Henri Salvador, Harry Belafonte, etc.

20. Une version de 1939 de « Sweetie Charlie » est disponible sur Jamaica - Trance Folk Possession, Roots of Rastafari, Mystic Music From Jamaica 1939-1961 (FA 5384) en coédition avec le Musée du Quai Branly dans cette collection.

21. Retrouvez les versions jamaïcaines traditionnelles des succès de Harry Belafonte sur Jamaica - Mento 1951-1958 (FA 5275) dans cette collection. Une version jazz de « Iron Bar » figure aussi sur Jamaica Jazz 1931-1962 (FA 5636).

22. Retrouvez Blind Blake sur Bahamas - Goombay 1951-1959 (FA 5302) dans cette collection.

23. Retrouvez Josephine Premice sur Calypso dans notre coffret Anthologie des musiques de danse du monde (FA 5342).

Caribbean in America - 1915-1962

Blues, habanera, rumba, rock, mento, calypso, jazz,

merengue, son, mambo…

By Bruno Blum

Where is the love to be found, oh someone tell me

‘Cause life must be somewhere to be found

Instead of concrete jungle where the living is hardest

Concrete jungle, man you’ve got to do your best.

— Bob Marley, “Concrete Jungle,” 1973.

Close neighbours of the United States, since time immemorial Taino Indians (both Arawaks and Caribs) circulated in the Caribbean Sea. Migrations between islands and the North American continent intensified in the centuries after 1492, feeding the United States — especially the great ports of New Orleans, Miami and New York City — with lyrics, melodies, harmonies, dances, musicians and rhythms from the Caribbean. Our Cuba in America 1939-1962 and Calypso 1944-1958 collections in this series are devoted to the international influence of Cuban and Trinidadian musics. They are complementary to this set.

It is useful to be reminded that the making of a creole identity started in the first hours of the colonisation of the Americas. Runaway African slaves began mixing with Caribbean, Taino Indians and, in Louisiana — which is a sort of Caribbean enclave on the continent, with a typically Caribbean culture, where populations mixed, were surrounded by water (almost like an island) and were situated at the gates of the continent —, with Choctaws and Lipan Apaches. Not to mention the French, Spanish, Portuguese and British.

An equally important notion is that the Haitian revolution triggered the migration of many French-speaking Caribbeans to Trinidad and Louisiana around 1800, bringing along Haitian animist culture, its cosmology and its very influential chants and rhythms, as shown in our Haiti Vodou 1937-1962 and Voodoo in America 1926-1962 sets, which explain how this creole spirituality took root in the music of the USA.

The migration of a number of Cuban slaves to the continent (incuding many Yorubas), as well as some Jamaican Ashantis and people from other islands deeply pervaded US culture — and first and foremost, it pervaded African-American culture.

Recorded in 1950, Camille Howard’s Shrinking Up Fast does indeed anticipate 1970s funk music; however the influence of the Caribbean on American popular music is not limited to the roots of that style, which are acknowledged in our Roots of Funk set1. Our Caribbean series show that the West Indian cultural influence, and especially the musical one, on the North American continent was not only sizeable but widely underestimated, misunderstood and concealed by many Americans. All the way from work songs to negro spirituals, to jazz and New York salsa, to rap, which was born in Jamaica2, American music is unswervingly tied to a common history with the Caribbean.

Creole Music

In an album entirely devoted to the Caribbean presence in the United States, Duke Ellington alludes to Congo Square in New Orleans, where slaves could play on Sundays as dating from at least the 17th century. Rhythm Pum Te Dum is taken from his A Drum Is a Woman album of 1956, where the Duke praises the power of rhythm through his characters Caribee Joe and black beauty queen Madam Zajj, who falls in love with him.

Rhythm music was and remains one of the strong symbols of African-American culture. Much of this culture was expressed spontaneously through chants and rhythms, which were rightly perceived as an identity assertion — and were therefore classed as subversive in the racist societies of the day in both the Caribbean and the continent. The importance and ubiquitous presence of Caribbean music in the USA needs to be explained.

Firstly, because African cultures were strictly forbidden and mercilessly cracked down on in the North American continent during the days of slavery (1492-1865). By the same logic, African-American cultures continued to be very depreciated in the century of segregation that followed the abolition of slavery (1865-1964). During this time one had to resemble the Whites; any form of African-ness was presumed inferior and “savage” and was then assumed as such, including by many Black people.

This prejudice, turned into a sociological complex, was, among others, fought in the decades from 1910-1930 by the great, black, catholic leader Marcus Garvey, who basically aimed to bring back self-esteem to African Americans. He can be heard here, in an excerpt from a preachy-sounding speech, as he leaves the room with the words “one love,” a Jamaican catchphrase which Bob Marley would turn into one his most famous songs in 1964. African Americans used religious songs, called negro spirituals, as well as baptist, methodist, pentecostal (etc.) churches as vehicles for their culture and for organising themselves — and as façades.

Repression meant that the impact of cultures coming directly from Africa was reduced, concealed, and thus became not much visible. An African cultural presence in North America was, in good part, made possible however through the persistence of Caribbean populations, who somehow managed to perpetuate some elements of their ancestral cultures — which they later brought along to the United States (for instance the vibraphone heard here on the Tito Puente and Cal Tjader tracks is a legacy of the West African balafon).

Fusions of African and European cultures therefore did exist, and are called “creole.” The creole identity was peculiar to the Americas; it was a new mix, distinct from its overseas origins. Although creole-ness was supposed to be synonymous with the slavery culture — meaning the eradication of any surviving African cultures — in truth it left some room for negritude and did tolerate at least some differences, some links with Africa and its scorned cultures.

Creole culture would grow better in places such as Jamaica, Martinique, Cuba, New Orleans and elsewhere in the Caribbean sea.

Creoles implanted in New Orleans and the Caribbean alike were often more aware of their roots, their special identity and the value of their culture. And most of all, they had practiced preserving it for a long time. As such, they were more inclined to resistance, to claiming their own identity and to ethical demands to the surrounding white culture than African descendants implanted further North, where their culture had been even more brutally suppressed as repression grew harsher over the years.

In the United States, creole roots and a Caribbean identity are like symbols of resistance; they were embodied by blacker people, more vehement, closer in spirit to their African origins, more subversive and more feared, because they were more likely to doggedly forward their culture. Therefore, they played an important part in the evolution of mentalities that surfaced in the twentieth century, when racial segregation prevailed. Haitians and Jamaicans were typically the most hostile to oppression, but this inner strength was spread around all of the Caribbean basin. Music and dance were essential elements of those cultures: they meant rare moments of freedom for both body and soul.

In 1946, it is on a Caribbean rhythm that Albert Nicholas sang the very creole Salee Dame in French patois, just before this language, which was a symbol of the original creole identity in the USA, plumetted almost completely in Louisiana, in the second part of the century. The first rock superstar, Fats Domino, was a proud, Louisiana French Creole, born to a mother of Haitian (and Indian) origin. It was logical that the immense success of his music was linked to the cultural power intrinsic to his art, to the creole synthesis he embodied.

Yet this creole edge would also grow significantly in remote islands where the population of African descent was a great majority (over 90%). Furthermore, in the United States, where African-American populations were only a small minority (less than 15%), oppression and cultural repression were obsessions because of the fear of slave uprisings (in 1811, more than five hundred Haitian slaves rioted and were killed in Louisiana).

It was feared that slaves would unite and riot, if they managed to structure resistance secretly. Which they in fact did, using, for instance, coded lyrics in negro spiritual songs3.

The continuing presence of negro spirituals, followed by gospel songs, ragtime’s success, then the emergence of, in quick succession, country blues, urban blues, jazz and rock music; all these were essentially made possible through separate networks, which were almost inaccessible to a general public deliberately kept at a distance. Those networks were, however, attended by open-minded White people who were passionate about African-American musics (see our Beat Generation 1936-1962 and Elvis Presley & the American Music Heritage 1954-1956 in this series).

Oppression and cultural segregation were mandatory and endemic: except for a very few songs, African American music was considered vulgar and subversive. It was diverted away from American radio until the end of the 1940s, as demonstrated, with some precision, by our Race Records - Black Rock Music Forbidden on U.S. Radio 1942-1955, which documents the first few years of rock music.

Protest

At the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries early African-American leaders (former slave Booker T. Washington and Northern mulatto W. E. B. Du Bois, the first “Black” Harvard alumni) were intellectuals. Advocating culture and education, they were searching for compromise in order to free their people. Following these historical figures, it is no coincidence that the first great, radical, black nationalist leader in the United States, the very combative Marcus Garvey (United Negro Improvement Association), who was active between the two World Wars, was a Jamaican4. Among his followers was Elijah Muhammad, who became the leader of The Nation of Islam (an Americanised, Islam-derived movement in which a cult of the leader’s personality is central).

There was, as well, a popular member of the NOI, Malcolm X (whose mother was born in Barbados) and Louis Farrakhan (born to a St. Kitts and Nevis mother and a Jamaican father, he had a stepfather from Barbados), who joined the NOI in July of 1955, before taking control of it twenty years later. In contrast with those right-wing Black nationalists, Martin Luther King, who crafted the Civil Rights movement in the years 1955-1968, was a baptist born to parents from the United States. Qualified and followed by a majority of African-Americans, he went for consensus and was a partisan of non-violence, allied with left-wing pacifists such as Harry Belafonte, Josh White and white ones like Bob Dylan and Joan Baez5.

On the other hand, Farrakhan, would be highly criticised for his racist and antisemitic statements. Trained as a violonist, he had also been a calypso artist in 1953-1955, as Calypso Gene The Charmer. Thus, before he became an active supporter of American puritanism in “black muslim” mode, he had recorded some saucy, quality tunes in a calypso vein, such as Don’t Touch Me Nylon and Is She Is, Or Is She Ain’t, a homosexist song describing a transvestite in the tongue-in-cheek, comic, homophobic Caribbean tradition6. Six years later, it was as Louis X that he recorded another calypso named A White Man’s Heaven Is A Black Man’s Hell, a 45 RPM single condemning the crimes of slavery, colonisation — and inviting the listener to join Elijah Muhammad’s movement, in which he had become an activist.

Negritude, dear to intellectuals such as C. L. R. James, Édouard Glissant and Aimé Césaire, as well as populist tribune Garvey, always found a stronger expression in the Caribbean. Local music was marginalised on the islands, where it was repressed and boycotted by radios to leave room for colonial culture, but it, nevertheless, was strongly rooted in the black population majority and turned out to be an asset for the blooming post-war tourist industry. This cheesy, touristic edge did not exclude authenticity and quality, as can be heard on the records sold as souvenirs to tourists (cf. Jamaica - Mento 1951-1958 and Bahamas - Goombay 1951-1959 in this series). These brilliant creole songs, which were perhaps the most significant expressions of Caribbean people, finally reached the continent through various different means. They brought along their rhythms, such as the Cuban-Haitian habanera (pervasive on all of this set), their dances and their attitude.

Calypso, Trinidad and English-speaking Virgin Islands

The birth of American jazz is attributed to New Orleans, whereas in fact jazz was always the US form taken by the pan-American rhythm music present in all of the Caribbean basin at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries. As from 1917, through orchestras as well as jazz and blues records issued in the United States, music from the Southern USA made an impact on the Caribbean, including the Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, Jamaica, Trinidad-and-Tobago and Cuba. Conversely, some Caribbean jazz musicians were present in Cuba, Santo Domingo, Kingston, Paris, London, New York7…

“What [Tricky Sam] was actually doing was playing a very highly personalized form of his West Indian heritage. When a guy comes from the West Indies and is asked to play some jazz, he plays what he thinks it is, or what comes from his applying himself to the idiom. Tricky and the people were deep in the West Indian legacy and the Marcus Garvey movement. A whole strain of West Indian musicians came up who made contributions to the so-called jazz scene, and they were all virtually descended from the true African scene. It’s the same now with the Muslim Movement, and a lot of West Indian people are involved in it. There are many resemblances to the Marcus Garvey schemes. Bop, as I once said, is the Marcus Garvey extension.”

— Duke Ellington on trombone player “Tricky Sam” Nanton8

Caribbean recordings were made at a very early stage and hit the USA. Records by Afro-Caribbean musicians from Trinidad were recorded in New York City and spread out, as early as 1912 (Lovey’s Trinidad String Band): Lionel Belasco, a Sephardic Jewish pianist born to a creole woman in Trinidad (heard here, Bajan Girl was one of his compositions, cut in 1915 in ragtime style. It alluded to a girl from Barbados, where he was born), his friend Sam Manning and Monrose’s String Orchestra were all regular performers in New York clubs, where they also extensively recorded.

This constant musical exchange between the continent and the islands was particularly significant in the field of African-American creole musics, which mixed European and Caribbean influences. Caribbean records influenced the continent; as in American jazz at the time, some of the performers improvised in an informal way, as can be heard in a 1923 New York recording of Trinidad Carnival Songs by Trinidadian violin player Cyril Monrose.

Lloyd Prince Thomas was a calypso singer much influenced by Trinidad-and-Tobago records, but he was from the American Virgin Islands. Led by Virgin Islands pianist and composer Bill LaMotta, the LaMotta Brothers played in the Trinidadian calypso style, which they mixed with local quelbe music, but they also recorded some merengue, the nearby Santo Domingo music (as heard on Lloyd Prince Thomas’s Let’s Pray For Rain). The Fabulous McClevertys were also a band from the Virgin Islands; they backed The Charmer, later to become the leader of The Nation of Islam as Louis Farrakhan (born to Caribbean parents) — heard here in his 1953-1955 early calypso phase.

The parents of great saxophone player Sonny Rollins, from New York, were also from the Virgin Islands, and his most famous composition is probably St. Thomas, a name inspired by the largest of those islands — and its rhythms.

Although situated in the heart of the Caribbean, the Virgin Islands are an American territory (like Puerto Rico) which contributed to spreading Caribbean musics in the United States. Some of their rare music was collected on our Virgin Islands - Quelbe & Calypso 1956-1960 set, which includes some tasty voodoo songs.

Cuba in New Orleans

A sizeable migration of Haitian and Cuban slaves took place throughout the 19th century, bringing along with them some danceable, syncopated, creole versions of 18th century French and Spanish popular songs. According to great New Orleans jazz pianist Jelly Roll Morton, in the early 20th century jazz was stated in three modes: the stomp, the blues and the “Spanish tinge,” meaning a syncopated habanera swing, as played on one of his solo blues recorded in 1923:

“Now in one of my earliest tunes, New Orleans Blues, you can notice the Spanish tinge. In fact, if you can’t manage to put tinges of Spanish in your tunes, you will never be able to get the right seasoning, I call it, for jazz.”

— Jelly Roll Morton

In fact, this musician — whose family was partly from Haiti — alluded not to Spain but to the tresillo and habanera heard in Cuban contradanza, which was also at the root of the French-Haitian meringue and its Dominican merengue neighbour 9. In fact there was a Cuban/Haitian presence in New Orleans music right from the dawn of the record industry (for instance a habanera rhythm is found on the introduction to Louis Armstrong’s essential, 1929 version of “St. Louis Blues”)10.

A typical habanera pattern is, for example, distinctly heard played by Professor Longhair’s left hand (the piano bass notes) on Hey Little Girl, a 1949 blues cut in New Orleans.

As millions of African-Americans also did, Jelly Roll migrated to the North, where the southern musical influence propagated. Louisiana’s black creole jazz, which up to the 1950s was sometimes still French speaking, used rhythms from Haiti, voodoo, and the Caribbean, as heard on Danny Barker’s Tootie Ma Is a Big Fine Thing and Albert Nicholas’ Salee Dame (which includes a habanera) featuring drummer Baby Dodds, one of the founders of jazz.

On Carnival Day, which was recorded in New Orleans in 1950, trumpet player and singer Dave Bartholomew sings about the Zulu King seen at Mardi-Gras carnivals, which is a tradition brought over to the Americas by the French. Again a habanera pattern is heard there, this time played on the bass guitar, along with the typical clave rhythm (two bits of wood hit against each other), a Cuban rumba characteristic.

This percussion rhythm played on the clave was played on the guitar by Bo Diddley, who mixed it with the kind of negro spiritual-influenced singing he had sung as a child. Bo Diddley was born in nearby Mississippi and took a chunk of Afro-Cuban culture with him to Chicago, where, by playing this rhythm on a guitar, he created an original style that was to have a substantial influence on American and world music, all the way from Johnny Otis to The Doors, The Who and the Rolling Stones, who recorded a version of Mona for their first album11.

Dave Bartholomew soon became a successful arranger and producer for rock music founders such as Fats Domino, Lloyd Price and Little Richard. The habanera rhythm is just as fundamental in their Chee-Koo Baby, Little School Girl, Tell Me Pretty Baby and I’m Goin’ Back, which were all recorded with the same team and in the same J&M studio in New Orleans12. On these recordings, the drum rolls are the same as on Ray Charles’ famous “What’d I Say”: it is the Cuban rumba rhythm, normally played on the congas.

On Chico, a young Allen Toussaint (who would later become one of the creators of funk) borrows a rumba groove and injects a habanera on the bass and piano triplets, which was Fats Domino’s signature style.

As if by magic, experimental variations of these Cuban/Haitian/Puerto Rican rhythms were incorporated in several American styles: Ojai by Joe Lutcher’s “jump blues” orchestra, a pure habanera on Jeanne DeMetz’s Calypso Daddy, Make It Do by eccentric bopper Slim Gaillard in New York… even New Orleans’ blues singer and dancer Marie Bryant performed Don’t Touch Me Tomato to a habanera rhythm. This pan-Caribbean (Jamaican?) classic was also recorded by Josephine Baker and was “the first song [my son] ever sang,” according to Bob Marley’s mother Cedella.

Easily adapted to many styles, from ragtime to the blues, jazz and rock, the habanera and the rumba were at the heart of much African-American, pan-Caribbean culture. More rhythms of African origin surfaced in Jamaica13, and Cuba, as well as in Haitian voodoo, as deciphered in our Haiti Vodou 1937-1962 set. All of this musical culture somehow migrated to the USA in one way or another, mixing with traditions of European origin, such as polka, mazurka, bolero, waltz, quadrille and more: just so was the creole process in the Caribbean.

Cuban-American Jazz & Merengue

Following various episodes of US occupation, colonisation and becoming protectorates, the Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, Haiti and Cuba bowed to US economic/trade domination. In the 1930s, several orchestras in Havana began playing American jazz. To mention only a few, Hermano Castro’s orchestra was formed in 1929, followed by René Touzet, Armando Romeu, Hermanos Palau and Casino de la Playa (with singer Miguelito Valdés, later replaced by Orlando “Cascarita” Guerra). There was also the Orquesta Riverside, with the famous Tito Gómez, in the 1950s14.

American jazz also spread in Jamaica’s hotels and cabarets15. This strong American influence strengthened the tendency to improvise, as well as to incorporate sophisticated arrangements, elements which were also found in Haitian meringue and Dominican merengue. This grew into a jazzy, unbridled approach to Cuban music, which eventually gave birth to the dazzling Cuba Jam Sessions, where improvisations took place around strictly Cuban melodies and rhythms, recorded in 195716.

Then, in turn, Cuba left a deep mark on American jazz, at first abundantly, with Duke Ellington, included here on Rhythm Pum Te Dum (1947); two of Duke’s trombone players were Caribbean: “Tricky Sam” Nanton and Juan Tizol, the composer of “Caravan.” Stan Kenton, Dizzy Gillespie (Cubana Bop, 1947) and Charlie Parker (Barbados, 1947) were also precursors of Caribbean arrangements in jazz.

As early as 1950, as Fats Domino’s first rock hits suddenly appeared out of New Orleans, a trend for the latin musics of Cuba, Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic surfaced on all of the continent and beyond (mambo, cha cha chà, plena, merengue, bomba…). In 1950, accordion player Angel Viloria’s Dominican merengue group was a hit in New York City, where the underpriviledged Puerto Rican community supported this dance music par excellence (Amoríos, El Gallero), and where virtuoso saxophone player Ramón E. Garcías competed with the best jazzmen.

At the end of his short life, Charlie Parker persevered in using Caribbean arrangements, which he applied to the Spanish song La Paloma, to Cole Porter’s standard Begin the Beguine (biguine is a French Antilles style) in 1952 and many other tunes. White vibraphonist Cal Tjader also soon adopted the mambo. He arranged American compositions in this style (Yesterdays, East of the Sun, 1954) and hired Cuban musicians such as Willie Bobo and Mongo Santamaría (who composed the classic Afro Blue). Bud Powell (Un Poco Loco, 1951), Sonny Rollins (St. Thomas, 1956) and Mickey Baker (Guitarambo, 1956) went into further extrapolations around hybrid, undefinable Caribbean rhythms.

Puerto Rico, USA

Just like the nearby American Virgin Islands, the island of Puerto Rico is a United States territory situated in the heart of the Caribbean, a renowned spot for tax-dodging and tourism. It is confined to a colonial status — its citizens cannot vote in US presidential elections — but unlike many other Caribbeans wishing to flee to Miami, three and a half million Puerto Ricans have freedom of movement on the continent (see the musical film West Side Story, which depicts this territorial ambiguity in the New York Puerto Rican community).

A sizeable, Spanish-speaking, Puerto Rican population is therefore implanted on the US mainland, mostly in New York — and they were a choice audience for all latin musics. In the 1950s they represented the bulk of music buffs going for Dominican merengue, Cuban mambo, son and cha cha chá, etc. Puerto Rico was thus the Trojan horse that allowed latin musics to slip inside the continent.

Born in Harlem to Puerto Rican parents, as early as 1949 percussionist and vibraphonist Tito Puente became a Cuban mambo giant, with some remarkable improvisation-filled recordings (such as El Mambo Diablo and Vibe Mambo included here). Like Cuban exile Machito before him, he hired some of the best musicians from the latin Caribbean diaspora, asserting a strong presence of these musics on the continent, where, mixing with Dominican merengue, they would soon evolve into salsa under the impulse of Puerto-Rican musicians such as Johnny Pacheco.

Cuban music became successful in all of the Spanish-speaking countries around the Caribbean basin, including Colombia, Venezuela and Mexico, as well as Miami, Los Angeles and New York. Dominican pianist Francisco Alberto Simó Damirón had moved to Puerto Rico. He loved American-styled, sophisticated arrangements and the wealth of Cuban rhythms; Damirón y Chapuseaux often came to play on the mainland, where they contributed to the success of merengue.

Many internationally famous Puerto Rican musicians got their break in New York, including Eddie Palmieri, Tito Puente (who, after mastering the mambo, diversified his latin repertoire) and the legendary Cortijo y su Combo, featuring Ismael Rivera at the mike and, on the piano, Rafael Ithier, who would later form the celebrated El Gran Combo salsa group. From 1955 to1962 Rafael Cortijo was the king of modern bomba (a traditional rhythm also found in Haiti17) as shown with Pa’ Tumbar la Caña, as well as plena, two styles inherited from traditional Puerto Rican rhythms. Bomba and plena were close to nearby Dominican merengue and Haitian konpa. He, too was influenced by Cuban mambo (wind instrument arrangements) and often played on the mainland. As with Tito Puente’s, in his golden age Cortijo’s orchestra used compelling Cuban rhythms, but this all ended abruptly in 1962, after Ismael Rivera was jailed for drug possession.

Calypso & Jamaican mento

“Typical” Caribbean songs were first incorporated into jazz and international pop music in the 1930s18. This wave of exoticism inspired some saucy songs with savoury double-entendre and sexual metaphors (called hokum records in the US) which were found in abundance in Jamaican mento and Trinidadian calypso.

These songs echoed the fantasies of prostitution, scantily-clad ladies and loose morals then evoked by Cuban rumba, Dominican merengue, latin music from Puerto Rico and tropical climate islands where US Navy bases — and pertaining short-time hotels — were widespread. In short, the tropics inspired thoughts of sexual tourism, sunshine and beaches. With the exception of some daring folk songs implicitly criticising colonialism, such as “Brown Skin Girl,” and many negro spirituals, freedom-fighting black activism (which would free many minds, notably through Marcus Garvey-inspired Rastafarians such as Bob Marley) did not yet truly take a significant place in US popular music.

Farrakhan’s White Man’s Heaven Is a Black Man’s Hell is a significant example of calypso protest song, but it was written by a Boston intellectual, did not directly come from the Caribbean and had little impact. However, the Sly Mongoose melody (a Jamaican song of unknown authorship), was first recorded by Lionel Belasco in 1923; the first version featuring lyrics was cut in 1925 by Sam Manning in New York. It features a mongoose, which to a certain extent had become a cheeky symbol of colonisation’s failure (sly mongooses were imported from India by the British to eradicate snakes in Jamaica, but they eventually devastated henhouses around the island).

Alluding to them was a way to mock the all-powerful, such as Alexander Bedward, a preacher with a big following in the early 20th century, who baptised hundreds of people in a river. Bedward was struggling against the colonial society, and was one of those who inspired the Rastafarian movement, born around 1932. In this song, his daughter is seduced by a newspaper reporter (named “Mongoose”) who takes one of Bedward’s “fattest chickens” to be baptised.

“Mongoose, a newspaper reporter

Took Bedward [pronounced ‘bed with’] the Preacher’s daughter

Baptize her in his holy water

Sly mongoose

Mongoose went into Bedward’s kitchen

Took up one of his fattest chicken

That’s the reason why he fled from Jamaica”

The mongoose (the journalist) flees from Jamaica to Cuba, then lands in the United States, where he becomes famous. As one of his concerts of 1952 reveals (disc 1), Charlie Parker played an instrumental version of this emblematic Jamaican mento song, but he was already quoting a piece of this melody in his December 17, 1945 version of “52nd Street Theme.”

Following the success of “Rum and Coca-Cola” by The Andrew Sisters in 1944 (a cover version of Trinidadian Lord Invader’s song), which alludes to prostitution, calypso found its place in the United States. It was in tune with the new momentum of tourism, made possible by the development of civil aviation and the wave of post-war exoticism (cf. our Calypso album, which shows how the music of Trinidad went international in the years 1944-195819).