- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

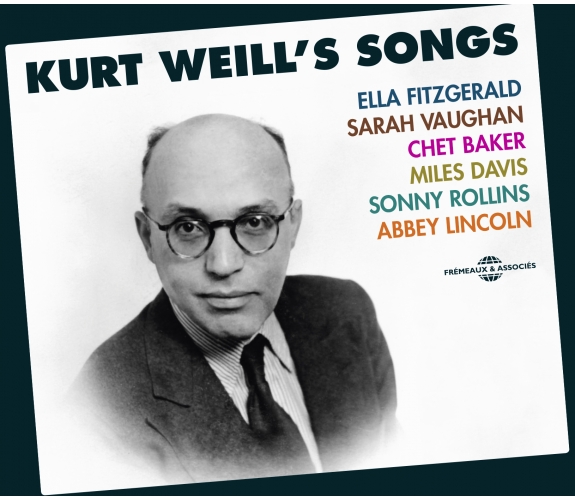

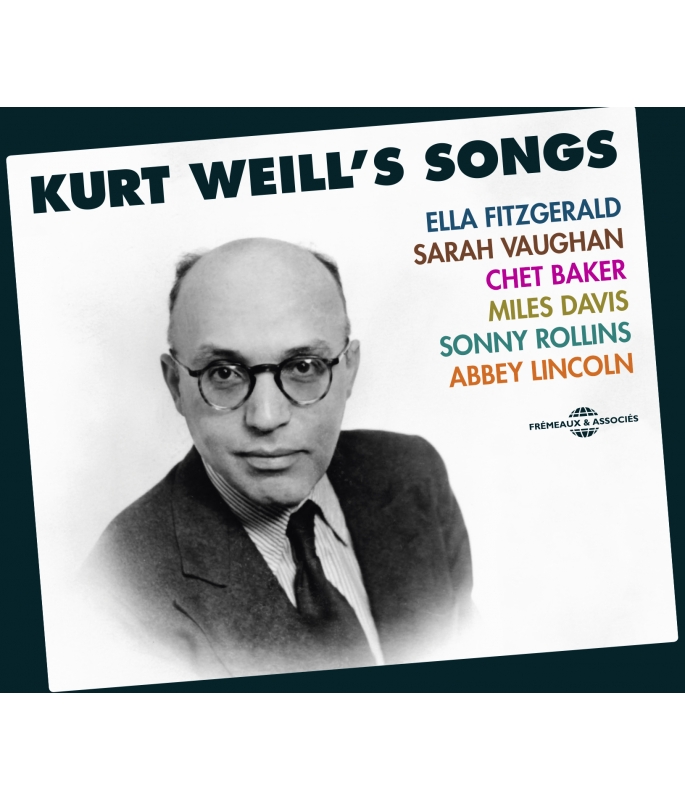

ELLA FITZGERALD • SARAH VAUGHAN • CHET BAKER • MILES DAVIS • SONNY ROLLINS • ABBEY LINCOLN…

KURT WEILL

Ref.: FA5695

Artistic Direction : TECA CALAZANS ET PHILIPPE LESAGE

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Total duration of the pack : 3 hours 24 minutes

Nbre. CD : 3

ELLA FITZGERALD • SARAH VAUGHAN • CHET BAKER • MILES DAVIS • SONNY ROLLINS • ABBEY LINCOLN…

ELLA FITZGERALD • SARAH VAUGHAN • CHET BAKER • MILES DAVIS • SONNY ROLLINS • ABBEY LINCOLN…

During the Fifties, American artists from the world of jazz and songs turned to Kurt Weill and the melodies that came from his music for the theatre, notably the future Broadway hits that he created in the USA. Thanks to those artists, Weill’s songs went straight into the Great American Songbook for good, writing a new chapter that erased the Berlin/Brecht imagery usually linked to the German composer of the world-famous Threepenny Opera. Teca Calazans & Philippe Lesage

JULIAN BREAM • LAURINDO ALMEIDA • VICTORIA DE LOS...

ANTHOLOGIE DES BANDES ORIGINALES 1960-1998

FROM GLENN MILLER STORY TO THE PINK PANTHER...

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Lost In The StarsAbbey Lincoln00:04:101959

-

2Speak LowLena Horne00:03:281958

-

3MoritatSonny Rollins, Max Roach00:10:041956

-

4September SongNat King Cole00:02:591961

-

5Mack The KnifeElla Fitzgerald00:04:461960

-

6My ShipMiles Davis, Lee Konitz, Paul Chambers00:04:251957

-

7Moon-Faced And Starry-EyedJohnny Mercer, Benny Goodman00:03:021947

-

8Speak Low 2Billie Holiday, Ben Webster00:04:271956

-

9Mack The KnifeLouis Armstrong00:03:541956

-

10September Song 2Red Norvo, Charles Mingus00:03:311956

-

11Speak Low 3Anita O'Day00:02:351962

-

12Mack The KnifeAnita O'Day00:03:081959

-

13My ShipErnestine Anderson00:03:401958

-

14September Song 3Django Reinhardt, Maurice Vander, Pierre Michelot00:02:331953

-

15September Song 4Joe Loco00:03:041961

-

16Speak Low 4Henri Salvador, Pierre Michelot00:04:281956

-

17Moon–Faced And Starry-EyedMax Roach00:02:531959

-

18Speak Low 5Max Roach00:02:501959

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Speak Low 6Ervin Booker00:06:591961

-

2Mack The Knife 3Erroll Garner00:04:281962

-

3My Ship 3Anita O'Day00:02:421962

-

4Here I Ll StayGerry Mulligan00:04:591962

-

5September Song 5Frank Sinatra00:03:071946

-

6Mack The Knife 5Bing Crosby00:03:541957

-

7September SongArt Tatum00:03:221952

-

8Bilbao SongGil Evans, Elvin Jones, Ron Carter00:04:121961

-

9Lost In The StarsTony Bennett00:03:591958

-

10Speak LowChris Connor00:02:341958

-

11Lonely HouseAbbey Lincoln00:03:401959

-

12September SongWalter Huston00:02:531938

-

13Speak LowDick Hyman00:01:531953

-

14It Never Was YouDick Hyman00:03:011953

-

15Foolish HeartDick Hyman00:02:121953

-

16Speak LowChristiane Legrand, Stéphane Grappelli00:02:371960

-

17September SongFranck Aussman00:02:511960

-

18Mack The KnifeDick Hyman00:02:161956

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Speak LowSarah Vaughan, Roy Haynes00:04:501958

-

2September SongSarah Vaughan, Roy Haynes00:05:471958

-

3Wie Man Sich BettetAndré Prévin00:06:071961

-

4Speak LowChet Baker, Gerry Mulligan00:02:091953

-

5September SongChet Baker, Paul Chambers00:03:031958

-

6My ShipJerry Southern00:03:551956

-

7Mack The KnifeBobby Darin00:03:081958

-

8Speak LowChico Hamilton, Eric Dolphy00:02:281959

-

9September SongChico Hamilton00:03:351959

-

10OvertureAndré Prévin00:05:021961

-

11Bilbao SongAndré Prévin00:04:041961

-

12BarbaraAndré Prévin00:06:051961

-

13Seerauber JennyAndré Prévin00:04:201961

-

14Mack The KnifeAndré Prévin00:04:521961

-

15Surabaya JohnnyAndré Prévin00:04:141961

-

16UnzulanglichhkeitAndré Prévin00:04:521961

-

17September SongBetty Roché00:02:111961

-

18Moon-Faced And Starry-EyedDick Hyman00:02:191953

Kurt Weill FA5695

KURT WEILL’S SONGS

ELLA FITZGERALD

SARAH VAUGHAN

CHET BAKER

MILES DAVIS

SONNY ROLLINS

ABBEY LINCOLN

KURT WEILL’S SONGS

(Mack The Knife, Speak Low, September song, My Ship, Lost In The Stars and other songs)

Vers le grand public

L’Amérique chantait Kurt Weill lors de la décade 1950. Ce fut comme une vague qui submerge. Alors qu’ils faisaient jusque-là peu de cas de son répertoire, les artistes du monde du jazz et de la chanson s’emparèrent des airs qui illuminaient son théâtre musical. Les « songs » quittaient les scènes de Broadway pour aller vers le grand public, le rêve de toujours de Kurt Weill, il est vrai. C’est autre chose, c’est une autre respiration, un regard différent, c’est dévoiler un monde bien éloigné de l’Europe en général et du Berlin que les nazis jugeaient décadent. Que font-ils de si particulier, ces artistes ? Ils capturent, transgressent, détournent, digèrent les « songs ». Ils se les accaparent et les habillent de leur propre subjectivité. Les voix blanches : (Anita O’Day, Jerry Southern, Bobby Darin, Bing Crosby, Frank Sinatra…), les voix noires : (Sarah Vaughan, Ella Fitzgerald, Betty Roché, Ernestine Anderson, Abbey Lincoln, Nat King Cole, Louis Armstrong…), les saxophones tout en puissance (Sonny Rollins, Booker Ervin…), les trombones agiles (Jay Jay Johnson), la sonorité aérienne de Miles Davis ou ronde de Clifford Brown, les écrins de cordes et l’intelligence des arrangements (Gil Evans, André Previn, Ralph Burns…) démontrent, s’il en était encore besoin, que sa musique plus audacieuse qu’il n’y parait de prime abord occupait bien une place privilégiée dans le great american songbook aux côtés de George Gershwin, d’Irving Berlin ou de Cole Porter. Pour toujours et sans étape en purgatoire.

Quelle identité ?

Kurt Weill s’est éteint le 15 mars 1950, à New York. Il était né à Dessau, en Allemagne orientale le 2 mars 1900. Cette vie brève vécue intensément se partage musicalement en deux périodes : une première étape européenne marquée par les fécondes années berlinoises qui fondent sa renommée et un parcours américain, imposé par l’émigration en 1935, jalonné de succès sur les scènes théâtrales de Broadway. Comme sa compagne Lotte Lenya, avec qui il eut une vie sentimentale agitée, il obtiendra la nationalité américaine qu’il désirait tant il ne se reconnaissait plus dans les errements de son pays natal. En réponse à un journaliste qui le qualifiait de compositeur allemand, en un demi-sourire, il avait répondu : « Irving Berlin que l’on considère comme le plus grand compositeur américain était un juif d’origine russe ; moi, je suis un compositeur américain d’origine juive allemande ». Dont acte.

Cette assertion tient un rôle non négligeable dans l’orientation donnée à notre anthologie. Alors qu’en un premier temps s’imposait l’idée de couvrir autant les œuvres majeures composées lors des années berlinoises (en particulier les reprises réalisées à la fin des années cinquante par Wilhem Brückner - Rüggenberg) et les contributions des artistes français (les adaptations de Boris Vian, les disques de Catherine Sauvage, entre autres), une inflexion s’est assez vite dégagée pour ne retenir au final que le versant des lectures américaines.

Du répertoire

Cette anthologie se focalise donc en priorité sur les compositions conçues aux USA même par Kurt Weill sans négliger pour autant d’arpenter quelques thèmes « allemands » tirés de « L’Opera de Quat’ Sous », de « Grandeur et décadence de la ville de Mahagonny » et de « Happy End » mais dans leur relecture typiquement yankee fort éloignée de ce qu’en donnent les artistes européens qui, eux, restent marqués au fer rouge par l’expressionnisme du théâtre berlinois. On se régalera des différentes versions de Mack The Knife toutes régies par un swing impérial mais dont aucune ne plagie l’autre (Louis Armstrong, Ella Fitzgerald, Bobby Darin, Erroll Garner, Anita O’Day, Bing Crosby, Dick Hyman, Sonny Rollins…). On se délectera aussi des interprétations anguleuses, acerbes, impertinentes, fidèles à l’esprit initial plus qu’à la lettre, délivrées par le pianiste André Previn et le tromboniste Jay Jay Johnson qui emportent une adhésion aussi passionnément violente que les versions princeps de 1930 telles que les 78 t de l’époque nous les restituent. Pour l’essentiel, le parcours musical chemine dans les partitions du « théâtre musical », (formulation qu’affectionnait Kurt Weill) réalisées aux Etats-Unis : « Knickerbocker Holiday », « Lady In The Dark », « One Touch Of Venus », « Street Scene », « Love Life », « Lost In The Stars ». C’est à cette source qui coule lors des années 1940 que les artistes américains puisent l’essentiel des « songs » alors que les européens en général et les français en particulier valorisent le répertoire marqué du sceau brechtien. Les titres les plus communément repris : September Song, Speak Low, My Ship , Lost In The Stars, Lonely House, Moon-faced and Starry-eyed. Chaque artiste apporte sa pierre à l’édifice. Du piano-bastringue de Dick Hyman à celui d’André Previn, innervé de musique classique européenne zébrée de colorations de la Seconde Ecole de Vienne, du grain de voix d’Armstrong au scat d’Ella Fitzgerald, du phrasé de Sarah Vaughan à la sombre raucité d’Abbey Lincoln, c’est tout un monde qui se profile en une désarmante sincérité. Malgré la réitération fréquente des thèmes, il n’est pas une version qui ne soit personnelle dans le timbre, dans le phrasé, dans la pulsation rythmique, dans l’appropriation du sens profond des paroles… Le talent musical des artistes américains se révèle une fois encore d’un niveau exceptionnel !

Une image ambigüe

Le succès phénoménal rencontré dès sa création par la chanson Mack The Knife (Moritat Vom Mackie Meisser en allemand ; La complainte de Mackie en français) ne serait-il pas un poison venimeux qui oblitère le reste de l’œuvre ? L’écrire n’est pas porter atteinte à la mémoire de Kurt Weill. Le compositeur n’est pas reconnu à sa juste valeur par les ayatollahs du gout. Son image reste trouble. Est-il un compositeur de facture classique ou un compositeur de Broadway de la trempe de George Gershwin ? Est-il d’ailleurs impératif de trancher ? Il suffit de noter qu’il est toujours resté fidèle à ses idéaux, à l’esprit subversif, à l’impertinence, qu’il a toujours cherché à aller vers plus de limpidité et de simplicité dans le cadre d’un théâtre musical qui parle à tous.

Si le succès à Berlin s’explique en partie par le contexte politico-économique ainsi que par l’effervescence artistique de l’époque, par son écriture audacieuse, par l’ouverture aux complaintes populaires, aux accents du jazz naissant et des danses d’Amérique latine à la mode ainsi qu’à la déconstruction systématique de l’opéra bourgeois ou de l’opérette viennoise, le succès rapide rencontré aux USA trouve ses fondations dans ses facultés d’adaptation à l’American way of life et à sa rapide maîtrise de l’anglais. Il aimait le rythme et l’humour des lyrics des revues de Broadway sur lesquels sa musique s’enchâssait avec aisance. Il relevait avant tout l’absence d’une tradition opératique bourgeoise offrant l’opportunité d’écrire un « opéra américain » ouvert aux problématiques sociales et porté par une aération rythmique, harmonique et formelle.

Les Années Berlinoises avec Bertold Brecht

Les noms de Brecht et de Weill sont indissociables, à juste titre. Pendant quelques années, grosso - modo de 1927 à 1933, ils partagèrent une belle complicité avant que naissent des dissensions liées à des personnalités bien affirmées et à des approches esthétiques divergentes. Tout laisse penser que Kurt Weill était un homme affable alors que Bertold Brecht avait une personnalité complexe et qu’il était enclin à tout ramener à lui et à ne considérer Weill que comme son collaborateur. On pourrait rajouter qu’il est de notoriété publique que Lotte Lenya ne faisait nullement confiance au dramaturge. Il n’en reste pas moins que Brecht (1898-1956) fut le grand théoricien de l’avant-garde théâtrale de son temps. Ses textes à la fois sombres, féroces, facétieux, jouant sur des formules lapidaires et les sonorités ont déteint de manière décisive sur la musique du jeune Weill qui, en juste retour des choses, offrait une écriture harmonique audacieuse et une dimension mélodique largement accessible à un public populaire.

Notre anthologie propose nombre d’airs de nos deux compères dont l’inévitable Mack The Knife repris par Dick Hyman, Anita O ‘Day, Louis Armstrong, Erroll Garner, Ella Fitzgerald, Bing Crosby et Bobby Darin. Composée au dernier moment, lors des répétitions, à la manière d’une ouverture d’opéra classique, la chanson originelle se présente sous forme d’une structure de ballade de rue et sa mélodie lancinante doit être interprétée avec une sorte de cynisme narquois pour distiller l’acidité du texte. Moritat Vom Mackie Meisser restera à jamais l’emblème de « Die Drei Groschenoper » (L’Opéra de Quat’Sous en Français, The Threepenny Opéra en anglais). On sait que la pièce s’inspire du « Beggars Opera » (opéra des gueux) des anglais John Gay – qui était le librettiste de Haendel – et John Pepush. Dans « l’Opéra de Quat’Sous », la situation se passe toujours en Angleterre mais au temps du règne de la reine Victoria, à la fin du 19è siècle. Macheath aka Mackie Meisser, un voyou jouisseur, chef de bande et surineur, est connu pour narrer ses exploits. La morale de l’histoire répond aux idéaux brechtiens: la société bourgeoise fait exactement le contraire de ce qu’elle préconise. C’est l’orchestre de Lewis Ruth sous la baguette de Theo Mackeben qui se produisit le 31 janvier 1928 pour la « première » de cette œuvre qui connut un immense succès immédiat. Le rôle de Jenny avait été confié finalement à Lotte Lenya. Louis Armstrong, lorsque ses producteurs lui firent découvrir le sens de la chanson, aurait déclaré : « à la Nouvelle Orléans, j’ai connu des types comme ça qui jouaient du couteau ». Le quartet où officient le pianiste André Previn et le tromboniste Jay Jay Johnson propose également une relecture époustouflante d’airs tirés de « L’Opéra de Quat’Sous » : Mack The Knife, Barbara Song, Seeraüber-Jenny et Unzuulaylichkeit. On trouvera également un surprenant Bilbao Song par le Gil Evans Orchestra ainsi que par le quartet Previn/ Johnson. Comme Surabaya - Johnny, cette chanson est tirée de « Happy End », une œuvre de 1929 qui fut un four total. Sur une histoire de guerre fratricide de gangs, cette pièce démontrait une répulsion pour l’Amérique comme le fera d’ailleurs « Grandeur et décadence de la ville de Mahagonny » (Mahagonny est une ville imaginaire qui ne peut qu’être située aux USA d’autant que Alabama Song est chantée en anglais perdues au sein d’airs en allemand). De cette pièce, le quartet Previn /Johnson reprend également Wie Man Sich Bettet (Mein heren, mein mutter pragte)

Les librettistes et paroliers américains

Plus qu’à Paris, court séjour qui lui laisse un fond d’amertume et d’inachevé, Kurt Weill trouve en Amérique, une terre propice à l’expression de son talent d’autant qu’il adopte, contrairement à Bertold Brecht et à Hanns Eisler, autre compositeur allemand émigré, une attitude positive et constructive envers l’american way of life et les possibilités de la machinerie culturelle de ce pays. Il se lie vite d’amitiés avec les membres du Group Theatre et des intellectuels sensibles aux causes sociales. Le premier d’entre aux sera Paul Green (1894 -1981) avec qui il écrit « Johnny Johnson », l’histoire d’un simple soldat qui hait la guerre. Mais c’est avec Maxwell Anderson (1898-1959) que l’entente sera la plus sincère, la plus profonde autant dans l’expression artistique que dans la vie quotidienne. Journaliste, scénariste et dramaturge, Maxwell Anderson avait obtenu le prix Pulitzer en 1933 pour sa pièce « Both Your Houses » et son récit autobiographique écrit sous pseudonyme (« Morning, winter & night ») où il évoque l’inceste et le sadomasochisme à la ferme de sa grand-mère avait connu un immense retentissement. Il participera aussi aux scénarios des films « Key Largo » (1939), « Faux Coupable » (1956) et « Ben Hur » (1959). Il est donc un auteur d’envergure aux sensibilités sociales prononcées. Leur tandem se noue, en 1938, avec « Knickerbocker Holiday », une pièce qui aborde de front le mythe américain avec une histoire autour de la fondation de New Amsterdam en 1647. Le personnage central Peter Stuyvesant est un dictateur vieillissant qui peut faire songer, en filigrane et dans le monde moderne, à Mussolini. La chanson phare September song est une jolie prouesse sur l’expression du temps qui passe. Elle est amendée spécialement, lors des répétitions, pour que Walter Huston, excellent comédien mais piètre chanteur, puisse la fredonner (cet immense comédien est le père du cinéaste John Huston pour qui il tournera « Le Trésor de la Sierra Madre » aux côtés de Humphrey Bogart).

Les deux compères se retrouveront, en 1949, autour d’un sujet concernant l’apartheid sud-africain et qui ne pouvait laisser insensible la communauté afro-américaine. « Lost In The Stars » s’inspire du livre d’Alan Paton : « Cry, Beloved Country ». La partition s’imprègne de magnifiques chants zoulous. Les titres qui marquent sont Trouble Man, Stay Well et bien sûr Lost In The Stars. On ne s’étonnera pas que la merveilleuse Abbey Lincoln ait traduit cette chanson en un cri bouleversant (« il dit que nous vivons tous sur la même planète, suspendue dans l’univers et que nous sommes tous perdus dans les étoiles »)

Kurt Weill, qui avait rencontré les frères Gershwin à Berlin et qui ne cachait pas son admiration pour « Porgy & Bess », conseillera au librettiste Moss Hart de faire appel à Ira Gershwin, dont il admirait les subtilités d’écriture et l’humour, pour les « lyrics » « de Lady In The Dark » en 1940. Copains comme cochons, Ira Gershwin et Weill composent d’ailleurs ensemble, l’un au clavier, l’autre adossé au piano, un crayon en main. Premier succès d’envergure de Weill aux USA, la pièce aborde la psychanalyse et le statut de la femme. Chacun des trois rêves est un petit opéra en soi où la musique autant que les paroles portent l’histoire. La mélodie de la délicieuse chanson My Ship incarne l’identité du personnage (on apprend qu’elle fut chantée pour la première fois par Liza à l’âge de trois ans dans un contexte de rejet parental). Autres titres significatifs de l’ouvrage : Saga Of Jenny, This Is New et One life to live.

Chanson - phare de la pièce « One Touch Of Venus » (Perlmann et Ogden Nash), Speak Low va devenir la signature de Weill à Broadway en 1943. Une fois encore, l’ouvrage porte sur le statut de la femme dans le cadre d’une satire sur les valeurs de la banlieue, les dérives sexuelles, les manques artistiques des classes de la bourgeoisie moyenne. Sarah Vaughan et Lena Horne en donnent des lectures chargées d’émotion.

Pour « Street Scene », en 1946, Weill travaille sur un livret d’Elmer Rice et des lyrics du poète noir Langston Hughes. Langston Hughes (1902-1967), docteur en littérature, correspondant pendant la guerre civile en Espagne, a contribué à la Harlem Renaissance et il reste une des plus grandes plumes poétiques de la communauté noire (« The Weary Blues », « The Negro speaks rivers »). Weill considérait cette pièce comme la synthèse de son expérience américaine. Il s’agit d’un hymne au cosmopolitisme dans l’espace symbolique d’un drugstore. Langston Hughes, qui valorisera une poésie simple, avait trainé Weill dans divers lieux et espaces représentatifs (églises, clubs, librairies) de New York. La résultante se note dans l’écriture jazz plus marquée et naturelle que d’ordinaire, dans l’influence reçue du blues et des spirituals. Les titres : le délirant Moon-faced and strarry-eyed, Lonely House, There,‘I’ll be Trouble, A Boy Like You. La version que donne l’inénarrable Johnny Mercer de Moon-faced and starry-eyed » avec l’orchestre de Benny Goodman est un petit bijou de fantaisie.

Dans notre anthologie, on trouvera « Here, I’ll Stay » par le Gerry Mulligan Quintet. Cette chanson est empruntée à la pièce « Love Life » d’Alan-Jay Lerner, composée en 1947/48. Alan-Jay Lerner (1918-1986), diplômé de Harvard et de la Juilliard School, est connu pour avoir participé à « Brigadoon, à « An American In Paris » et à « Gigi » de Vicente Minelli ainsi qu’à « My Fair Lady ».« Love Life » est l’histoire d’amour d’un couple qui se délite jusqu’au divorce. Autre titre souvent enregistré : Green Up Time. Avant « Lost In The Stars », Weill compose en 1948 « Down In The Valley » sur un livret d’Arnold Sundgaard, jeune dramaturge / enseignant féru de folk music. Peu connue en nos contrées européennes, cette pièce pensée au départ pour la radio et à destination d’amateurs a déjà connu plus de 6000 représentations aux USA.

Une présence constante

Kurt Weill n’a pas connu le purgatoire infligé à certains de ses contemporains. Après l’accaparement des « songs » par les jazzmen lors de la décade des années 1950, sa musique a été reprise au disque et à la scène dans le monde entier jusqu’à ces dernières années. Il est impossible de tout citer mais relevons comme faits marquants les deux albums de Lotte Lenya, l’un pour le marché européen sous la direction de l’ami des années berlinoises Roger Bean ; l’autre pour le marché américain sous la houlette de Maurice Levine ; la reprise de l’opéra de Quat’sous par Bob Wilson et la troupe du Berliner Ensemble (les représentations en 2016 au Théâtre des Champs Elysées firent salle comble) ; les disques de Catherine Sauvage, de Pia Colombo, les adaptations de Boris Vian ; le coffret Berlin Theatre Songs de Wilhem Brückner-Rüggenberg, avec la présence de Lotte Lenya dans la distribution ; l’album du Sextet Of USA Orchestra initié par Mike Zwerin avec Eric Dolphy, Jerome Richardson et John Lewis ; la localisation au Brésil effectué par Chico Buarque avec Opera do Malandro (Opéra du voyou) et l’album-concept novateur Lost In The Stars qui, outre l’ appel à des musiciens de jazz comme Carla Bley, Phil Woods, Charlie Haden et John Zorn, ouvre le champ à des voix essentielles de la scène rock comme Lou Reed, Tom Waits, Sting et Marianne Faithfull.

Teca Calazans – Philippe Lesage

© 2018 FRÉMEAUX & ASSOCIÉS

Notes : Nous avons largement puisé nos informations dans l’excellent livre de Pascal Huynh : « Kurt Weill ou la conquête des masses » (Actes Sud). Les deux disques de Lotte Lenya mentionnés dans la présentation sont : « Septembrer Song And Other American Theater Songs Of Kurt Weill » (Columbia Records, 1957, direction Maurice Levine) et « Lotte Lenya Singt Kurt Weill » (Philips, 1955, With Roger Bean & His Orchestra). On peut également se procurer « Die Drei Groschenoper Berlin 1930 » (Telefunken Legacy) ; Lotte Lenya & Weill avec « The Seven Deadly Sins et Happy End » (Orchestra & Chorus Wilhem Brückner – Rüggeberg (CBS Masterworks Portrait ; 1957). Le coffret CBS Masterworks paru en 1958, propose les mêmes artistes dans une version nouvelle de L’Opéra de Quat’ Sous ainsi que des chansons issues de Grandeur et Décadence de la Ville de Mahagonny, Happy End, Das Berliner Requiem, Der Silbersee. Le disque-concept Lost In The Stars avec Sting, Lou Reed, Tom Waits, Carla Bley est paru chez A&M Records en 1985

Remerciements à Daniel Nevers et Alain Tercinet.

KURT WEILL’S SONGS

(Mack The Knife, Speak Low, September Song, My Ship, Lost In The Stars and other songs)

Towards mass audiences

All of America was singing Kurt Weill in the decade beginning in 1950. It was as if a wave had submerged the country. Up until then, artists from the worlds of jazz and song had paid little attention to his work, but now they grabbed the songs that illuminated his “musical theater”. Songs started to move away from the stages of Broadway and out to the general public (Kurt Weill’s dream, in fact.) These were something else: another breath of air, a different outlook, a manner of revealing a world quite distant from Europe in general and from that Berlin which the Nazis judged decadent. What were those artists doing that was so special? They captured, transgressed, deviated and digested Weill’s songs, taking hold of them and clothing them in their own subjectivity. There were white voices (Anita O’Day, Jeri Southern, Bobby Darin, Bing Crosby, Frank Sinatra…) and black voices (Sarah Vaughan, Ella Fitzgerald, Betty Roché, Ernestine Anderson, Abbey Lincoln, Nat King Cole, Louis Armstrong…), powerful saxophones (Sonny Rollins, Booker Ervin…), nimble trombones (Jay Jay Johnson), the ethereal sound of Miles Davis or the rounded tones of Clifford Brown… together with the intelligence in the string settings of arrangers such as Gil Evans, André Previn or Ralph Burns, they all demonstrated, if need be, that his music, more daring than it appeared on the surface, indeed deserved a privileged place in the Great American Songbook, alongside George Gershwin, Irving Berlin and Cole Porter: a permanent seat with no transit through purgatory.

What identity?

Kurt Weill was born with the century (March 2, 1900) in Dessau, East Germany, and passed away in New York aged 50 (March 15, 1950). His life was short but intense, and musically it divides into two parts: a first period in Europe, marked by the prolific Berlin years that founded his reputation, and an American career imposed by his immigration in 1935, a shorter period that was studded by hits in Broadway theatres. Like his partner Lotte Lenya, with whom he had an agitated love life, he was granted the American nationality he very much desired, so little did he recognize himself in the errors of his native country. When a journalist referred to him as a German composer, his answer, half-smilingly, was, “Irving Berlin, whom people consider the greatest American composer, was a Jew of Russian origin; I’m an American composer of German Jewish origin.” Duly noted.

That assertion plays a role that has its importance in the orientation of the present anthology. While its first concept was to cover equally the major compositions of his Berlin years (in particular, the reprises made at the end of the Fifties by Wilhem Brückner-Rüggenberg) and contributions by French artists (among them, adaptations by Boris Vian, recordings by Catherine Sauvage, etc.) we quickly revised our opinion and finally retained only the American aspects of his work.

Repertory

This anthology therefore focuses in priority on the compositions conceived inside the USA by Kurt Weill, complete with a look at a few “German” themes (taken from his “Threepenny Opera”, “Little Mahagonny” and “Happy End” works), but in typically “Yankee” readings, quite distant from the versions sung by European performers, which remain branded, as if with a red-hot iron, by the expressionist theatre of Berlin. You can delight in the different versions of Mack The Knife, all of them governed by an imperial swing, but none of which resembles another (Louis Armstrong, Ella Fitzgerald, Bobby Darin, Erroll Garner, Anita O’Day, Bing Crosby, Dick Hyman, Sonny Rollins…). Just as tasty are the angular performances, caustic and impertinent (and faithful more to the spirit of the original than to the letter), delivered by pianist André Previn and trombonist Jay Jay Johnson, which were admired with as much violent passion as the editio princeps versions of 1930 as reproduced on period 78rpm records. Essentially, this musical trajectory winds its way through the scores for “musical theater” (to use Weill’s favourite term) that were created in The United States: “Knickerbocker Holiday”, “Lady In The Dark”, “One Touch Of Venus”, “Street Scene”, “Love Life” and “Lost In The Stars”.

It was from that source flowing through the Forties that American artists drew their songs for the most part, whereas Europeans in general, and the French in particular, would highlight the repertoire that bore the stamp of Brecht. The most commonly reprised titles were: September Song, Speak Low, My Ship, Lost In The Stars, Lonely House, Moon-faced and Starry-eyed. Each artist would add his stone to the edifice constructed: from the barrelhouse piano of Dick Hyman to that of André Previn, innervated with European classical music striped in the colours of the second Vienna School, from the grainy voice of Armstrong to the scat of Ella, from the phrasing of Sarah Vaughan to the sombre raucousness of Abbey Lincoln… a whole world takes shape with a sincerity that is disarming. Despite the frequent reiteration of these themes, not a single version fails to be totally personal in timbre, phrasing, rhythmic pulse, or the appropriation of the deep meaning of the lyrics… Once again, the musical talent of these American artists reveals itself to be nothing short of exceptional.

An ambiguous image

Could it be possible that the phenomenal success instantly met by the song Mack the Knife (Die Moritat von Mackie Messer in German)—as soon as it was first performed, in fact, was a deadly poison that obliterated the rest of Weill’s opus? To say so does not leave a stain on Kurt Weill’s memory, far from it. The composer has not been recognized by the ayatollahs of good taste as much as he deserves. His image remains blurred. Was he a composer in the classical vein, or was he a Broadway writer of the calibre of George Gershwin? And while on the subject, is it even vital to make a decision? It is enough to note that Weill always remained faithful to his ideals, to the subversive spirit, to impertinence, and that he always sought the path to clarity and simplicity in the context of a “musical theatre” that spoke to everyone.

If his success in Berlin can be explained in part by the socio-political context, the artistic effervescence of the period, his bold writing, his open mind regarding the laments of the people, the nascent accents of jazz and the dances of Latin America then in fashion (as well as the systematic deconstruction of bourgeois opera or Viennese operetta), his rapid rise to fame in the USA had its foundations in his capacity to adapt to the American Way of Life, and the speed with which he mastered the English language. He loved the rhythm and humour in the lyrics of Broadway revues, into which his music fitted exactly and with ease. Above all, he reacted to the absence of a bourgeois opera tradition, offering the opportunity to write an “American opera” that was open to social issues and carried by an airiness that was ventilated in rhythm, harmony and form.

The Berlin years with Bertolt Brecht

The names of Brecht and Weill are inseparable, and rightly so. For a few years, roughly between 1927 and 1933, they enjoyed a mutual complicity before they began to disagree due to differences in character (they both had strong temperaments) and divergent aesthetic approaches. All the indications are that Kurt Weill was an affable man while Brecht’s character was more complex; he was inclined to take all the credit and consider Weill as his collaborator. Moreover, it was common knowledge that Lotte Lenya didn’t trust the playwright at all. Even so, Brecht (1898-1956) was the great theoretician of the theatre’s avant-garde during his time. His texts were at once sombre and fierce, and he played facetiously on lapidary formulas and sounds; his style rubbed off on the music of the young Weill in a decisive manner, and the composer replied by proposing music with harmonic daring in a melodic dimension that was amply within the reach of a popular audience.

Our anthology contains a number of themes by the pair of them, including the inevitable Mack The Knife in versions by Dick Hyman, Anita O’Day, Louis Armstrong, Erroll Garner, Ella Fitzgerald, Bing Crosby or again Bobby Darin. Composed at the last moment during rehearsals, in the manner of an overture for a classical opera, the original song takes the form of a street ballad, and its haunting melody has to be performed with a sort of mocking cynicism in order to distil the acidity of the text. Die Moritat von Mackie Messer will remain forever the symbol for The Threepenny Opera, inspired by The Beggars Opera written by two Englishmen, John Gay (Handel’s librettist) and John Pepush. In The Threepenny Opera the action still takes place in England, but in Queen Victoria’s reign at the end of the 19th century. Macheath aka Mackie Messer is a sensual rascal, a gang-leader quick with a knife, and is known for recounting his exploits. The moral of the tale is a reply to Brecht’s ideals: bourgeois society does exactly the opposite of what it recommends. On January 31, 1928, it was the orchestra of Lewis Ruth under the baton of Theo Mackeben who performed at the work’s premiere, and its success was immediate, with the role of Jenny finally given to Lotte Lenya. When Louis Armstrong’s producers told him the meaning of the song, the trumpeter allegedly said, “I knew cats like that in New Orleans. They’d stick a knife in you as fast as say hello.”

The quartet featuring pianist André Previn and trombonist Jay Jay Johnson also proposes a breath-taking reading of tunes taken from “The Threepenny Opera”: Mack The Knife, Barbara Song, Seeraüber-Jenny and Unzulaenglichkeit. There is also a surprising Bilbao Song by the Gil Evans Orchestra as well as that by the Previn/Johnson quartet. Like Surabaya Johnny, the song is taken from “Happy End”, a 1929 work that was a complete flop. Around the story of a fratricidal gang war, this play showed repulsion, as would the later work “Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny” (Mahagonny being an imaginary city which can only be found in the USA, all the more since Alabama Song, sung in English, is lost in the midst of airs in German.) From this play, the quartet of Previn and Johnson also take up Wie Man Sich Bettet (Meine Herren, meine Mutter prägte).

The American librettists and lyricists

More than in Paris, where Weill’s short stay left him with a bitter taste and a feeling of incompleteness, in America the composer found more auspicious surroundings to express his talents, especially after adopting—contrary to Bertolt Brecht and Hanns Eisler, another immigrant German composer—a positive, constructive attitude towards America’s way of life and the possibilities of that country’s cultural machine. He became friends with the members of the Group Theatre and intellectuals sensitive to social causes.

The first of the latter would be Paul Green (1894 -1981), with whom he wrote “Johnny Johnson”, the story of a simple soldier who detests war. But it was with Maxwell Anderson (1898-1959) that the understanding would be the most sincere, and the deepest, as much in artistic expression as in daily life. Anderson, a journalist, screenwriter and playwright, had obtained the Pulitzer Prize in 1933 for his play “Both Your Houses”, and his autobiographical story—written under a pseudonym—entitled “Morning, winter & night”, in which he evoked the incest and sado-masochism on his grandmother’s farm had had immense repercussions. Anderson would also participate in the scenarios of the films “Key Largo” (1939), “The Wrong Man” (1956) and “Ben Hur” (1959). He was therefore an author of some standing, and a man of pronounced social awareness.

The tandem came together in 1938 with “Knicker-bocker Holiday”, a play that frontally tackled the American myth with a story based on New Amsterdam’s foundation in 1647. The central character, Peter Stuyvesant, is an ageing dictator who, in filigree and in the modern world, is reminiscent of Mussolini. The leading title (September song) is a little marvel in its expression of passing time. At rehearsals it was specially modified so that actor Walter Huston, an excellent co-star but a very poor singer, could hum it… Walter was the father of filmmaker John Huston and acted in “The Treasure of the Sierra Madre” for him alongside Humphrey Bogart.

They met up again in 1949, for a film dealing with apartheid in South Africa that was bound to find interest among Afro-Americans, “Lost In The Stars”, inspired by Alan Paton’s book “Cry, Beloved Country.” The score is impregnated with magnificent Zulu chants, and the titles that stand out are Trouble Man, Stay Well and, of course, Lost In The Stars. It’s no surprise that the wonderful Abbey Lincoln translated this song into an overwhelming cry, saying that we all live on the same planet, suspended in the universe, and we are all “lost in the stars.”

Kurt Weill, who had met the Gershwin brothers in Berlin and showed great admiration for “Porgy & Bess”, advised the librettist Moss Hart to ask Ira Gershwin, whose subtle writing and humour he also appreciated, to write the lyrics for “Lady In The Dark” in 1940. Ira Gershwin and Weill became as thick as thieves: together, the one at the keyboard and the other leaning on the piano holding a pencil, they composed Weill’s first major success in America. The play broached the subjects of psychoanalysis and a woman’s place in society. Each of the three dreams in the piece is a little opera in itself where the story is carried as much by the music as by the lyrics. The melody of the delicious song My Ship incarnates the identity of the character (we learn that it was sung for the first time by Liza at the age of three in a context of parental rejection.) Other significant titles in the work are Saga Of Jenny, This Is New and One life to live. Here again, the subject deals with woman’s condition in the framework of a satire on suburban values, sexual deviance and artistic absences in the middle class bourgeoisie. Sarah Vaughan and Lena Horne provide versions charged with emotion.

For “Street Scene” in 1946, Weill worked with a libretto by Elmer Rice and lyrics by black poet Langston Hughes (1902-1967), a war correspondent in the Spanish Civil War with a doctorate in literature. He was a contributor to the Harlem Renaissance and remains to this day one of the greatest poetic writers of the Black community, with “The Weary Blues” and “The Negro speaks rivers.” Weill considered “Street Scene” to be the synthesis of his American experience, and the work is a hymn to cosmopolitanism in the symbolic space of the drugstore. Hughes, who added value to simple poems, had drawn Weill into various representative places and spaces—churches, clubs, bookshops—in New York, and the outcome can be seen in scores that are markedly more ‘jazz’ and in the influence of blues and Negro spirituals (cf. titles such as the crazy Moon-faced and Starry-eyed, Lonely House, There‘ll be Trouble, A Boy Like You. The hilarious Johnny Mercer version of Moon-faced and starry-eyed with Benny Goodman and his orchestra is a sparkling little gem.

Our anthology also has the Gerry Mulligan Quintet’s version of Here, I’ll Stay, a song (borrowed from Alan-Jay Lerner’s play “Love Life”) that was composed in 1947/48. Alan-Jay Lerner (1918-1986), a graduate of both Harvard and the Juilliard School, is known for his work on “Brigadoon”, “An American In Paris” and “Gigi” by Vicente Minelli, as well as “My Fair Lady”. The play “Love Life” tells the story of a couple’s love declining to the point of divorce. Another title often recorded: Green Up Time. Before “Lost In The Stars” Weill composed “Down In The Valley” (1948) with a libretto by Arnold Sundgaard, a young playwright and teacher who was a great fan of folk music. Little-known in Europe, this play initially conceived for radio and aimed at theatre lovers has already enjoyed over 6,000 performances in the USA.

A constant presence

Kurt Weill never went through the purgatory inflicted on some of his contemporaries. After jazzmen picked up his “songs” in the Fifties, his music found its way onto record and was played on stages worldwide until only recently. It is impossible to list them all, but the two albums recorded by Lotte Lenya deserve special mention (one for the European market under the aegis of a friend during her Berlin years, Roger Bean; the other for America under Maurice Levine) as do the following: the reprise of The Threepenny Opera by Bob Wilson and the Berliner Ensemble troupe (its 2016 performances at the Théâtre des Champs Elysées in Paris were sold out); the records by Catherine Sauvage and Pia Colombo; the adaptations written by Boris Vian; the boxed set Berlin Theatre Songs by Wilhem Brückner-Rüggenberg, with a cast including Lotte Lenya; the album by the Sextet Of USA Orchestra initiated by Mike Zwerin with Eric Dolphy, Jerome Richardson and John Lewis; the Brazilian localisation by Chico Buarque with his Opera do Malandro, and the innovating concept-album Lost In The Stars which, apart from reaching out to jazz musicians such as Carla Bley, Phil Woods, Charlie Haden and John Zorn, opened the field to such essential voices on the rock scene as Lou Reed, Tom Waits, Sting and Marianne Faithfull.

Adapted by Martin Davies from the French text of Teca Calazans and Philippe Lesage

© 2018 FRÉMEAUX & ASSOCIÉS

Notes: We owe much of our information to the excellent book by Pascal Huynh, “Kurt Weill ou la conquête des masses” (Actes Sud). The two records by Lotte Lenya mentioned above are “September Song And Other American Theater Songs Of Kurt Weill” (Columbia Records, 1957, cond. Maurice Levine) and “Lotte Lenya Singt Kurt Weill” (Philips, 1955, with Roger Bean & His Orchestra). Also to be consulted are “Die Drei Groschenoper Berlin 1930” (Telefunken Legacy), Lotte Lenya & Weill, “The Seven Deadly Sins & Happy End”, Orchestra & chorus Wilhem Brückner–Rüggeberg, (CBS Masterworks Portrait, 1957). The CBS Masterworks boxed-set issued in 1958 has the same artists in a new version of the Threepenny Opera in addition to songs from Mahagonny, Happy End, Das Berliner Requiem, Der Silbersee. The concept album Lost In The Stars (with Sting, Lou Reed, Tom Waits and Carla Bley) was released by A&M Records in 1985.

Thanks to Daniel Nevers and Alain Tercinet.

DISCOGRAPHIE - CD1

1 – Lost In The Stars (Maxwell Anderson / Kurt Weill)

Abbey Lincoln (vocal), Kenny Dorham (tp), Phil Wright (p), Les Spann (g), Sam Jones (b), Philly Joe Jones (dr) - LP Abbey Is Blue, 1959 - Riverside RLP 12 – 308

2 – Speak Low (Ogden Nash / Kurt Weill)

Lena Horne (vocal) with Lenny Hayton and his orchestra - LP Give The Lady What She Wants, Septembre, 1958 RCA Victor – LPM 1879

3 – Moritat (Bertold Brecht / Kurt Weill)

Sonny Rollins (ts), Tommy Flanagan (p), Doug Watkins (b), Max Roach (dr) - LP Saxophone Colossus, New York 22 juin 1956 - Prestige 7079

4 – September Song (Maxwell Anderson / Kurt Weill)

Nat King Cole (vocal), George Shearing (p) with Quintet and string choir, arr : Raph Carmichael - LP Nat King Cole sings George Shearing plays - Enregistré décembre 1961- Capitol, EMS 1113

5 – Mack The Knife (Bertold Brecht / Kurt Weill)

Ella Fitzgerald (vocal), Jim Hall (g), Wilfred Middlebrooks (b), Gus Johnson (dr) - LP Ella In Berlin, 13 février 1960 - Verve MGV – 64041

6 – My Ship (Ira Gershwin / Kurt Weill)

Miles Davis (fgh), Gil Evans (arr, dir), Trumpet : Ernie Royal, Bernie Glow, John Carisi, Louis Mucci, Taft Jordan ; cor : Willie Ruff, Tony Miranda, Trombone : Jimmy Cleveland, Frank Rehak, Joe Bennett ; tuba : Bill Barber, Alto sax : Lee Konitz , bass-clarinet : Danny Bank, flûte et clarinette : Romeo Penque, Sid Cooper, basse : Paul Chambers, Drums : Art Taylor - LP Miles Ahead, enregistré le 10 mai 1957 - Columbia CL 1041

7 – Moon-Faced and Starry-Eyed (Langston Hughes / Kurt Weill) Johnny Mercer (vocal) with Benny Goodman orchestra - Enregistré le 30 février 1947 - Capitol 376

8 – Speak Low (Ogden Nash / Kurt Weill)

Billie Holiday (vocal) and His Orchestra : Bille Holiday (voc), Harry Edison (tp), Ben Webster (ts), Jimmy Rowles (p), Barney Kessel (g), Joe Mondragon (b), Alvin Stoller (dr) - LP All Or Nothing At all, 1956 - Verve VE - 2529

9 – Mack The Knife (Bertold Brecht / Kurt Weill)

Louis Armstrong and His All Stars / Louis Armstrong (tp, voc), James Orsbone Trummy Young (Tb), Edmund Hall (cl), William Orsbone “Billy Kyle” (p), Arvell Shaw (b), Barett Deems (dr) - Carnegie Hall, 17 Mars 1956, Columbia CL 1077

10 – September Song (Maxwell Anderson / Kurt Weill)

Red Norvo Trio ; Red Norvo (vibes), Tal Farlow (g), Charles Mingus (b) - LP Move, 1956 - Savoy Records MG – 12088

11 – Speak Low (Ogden Nash / Kurt Weill)

Anita O’Day (vocal) with Larry Russell Orch - LP The Lady Is A Tramp, Juillet 1962 - Verve Records AG V 2048

12 – Mack The Knife (Bertold Brecht / Kurt Weill)

Anita O’Day, Jimmy Giuffre - arr, dir and orchestra - LP Cool Heat, 1959 - Verve Records MGV 8312

13 – My Ship (Ira Gershwin / Kurt Weill)

Ernestine Anderson (voc), Pete Rugolo (dir), Bud Shank (as), strings and choir - LP The Toast Of The Nation’s Critics, 1958 - Mercury MG – 20400

14 – September Song (Maxwell Anderson / Kurt Weill)

Django Reinhardt (g), Maurice Vander (p), Pierre Michelot (b), Jean-louis Viale (dr) - LP Django et Ses Rythmes, Mars 1953 - Blue Star BLP 6830

15 – September Song (Maxwell Anderson / Kurt Weill)

Joe Loco (p), José Lozano (fl), Felix “puppi” Garetta, Gonzalo Martinez (violons), Nicolas Martinez (guiro), Mongo Santamaria (conga, dr), Willie Bobo (timbales), Victor Venegas (b), Bayardo Velarde, Rudy Calzado (vocals) - LP Locomotion, 1961 - Fantasy 8064

16 – Speak Low (Ogden Nash / Kurt Weill)

Henri Salvador (el-g), Pierre Michelot (b), Baptiste Mac “Kak” Reilles (dr) - 18 avril 1956 - Fontana Test

17 – Moon-Faced and Starry-Eyed (Langston Hughes / Kurt Weill)

Max Roach (dr), Ray Bryant (p), Bobby Boswell (b) - LP “Max Roach + 4 ; Moon-Faced and Starry-Eyed”, 9 & 10 octobre 1959 - Mercury MG – 20539

18 – Speak Low (Ogden Nash / Kurt Weill)

Max Roach (dr), Ray Bryant (p), Bobby Boswell (b) - LP “Max Roach + 4 ; Moon- Faced and Starry-Eyed”, 10 octobre 1959 - Mercury MG – 20539

DISCOGRAPHIE - CD2

1 – Speak Low (Ogden Nash / Kurt Weill)

Booker Ervin (ts), George Tucker (b), Felix Krull (p), Al Harewood (dr) - LP “That’s It”, 6 janvier 1961 - Candid 9014

2 – Mack The Knife (Bertold Brecht / Kurt Weill)

Erroll Garner Trio ; Erroll Garner (p), Eddie Calhoun (b), Kelly Martin (dr) - Enregistré en août 1962 à Seattle - Reprise 9 6080

3 – My Ship (Ira Gershwin / Kurt Weill)

Anita O’Day (vocal), Gene Harris (p), Andrew Simpkins (b), Bill Dowdy (dr) - LP Anita O’Day & The Three sounds, 1962 - Verve Records, V6 – 8472

4 – Here, I’ll Stay (Alan-Jay Lerner / Kurt Weill)

Gerry Mulligan (bs), Tommy Flanagan (p), Julian Priester (tb), Ben Tucker (b), Dave Bailey (dr), Alec Dorsey (conga) - LP Jeru, 1962 - Columbia BPG 62134

5 – September Song (Maxwell Anderson / Kurt Weill)

Frank Sinatra with orchestra, directed by Alex Stordhal - 30 juillet 1946 - Columbia

6 – Mack The Knife (Bertold Brecht / Kurt Weill)

Bing Crosby (vocal), Bob Scooley (tp, leader), and His Frisco Jazz Band avec Ralph Sutton (tp), Red Callender (b), Nick Fatool (dr) - LP Bing with Beat, 20 février 1957 - RCA Victor LPM 1473

7 – September Song (Maxwell Anderson / Kurt Weill)

Art Tatum Trio : Art Tatum (p), Everet Barksdale (g), Slam Stewart (b) - 1952 - Capitol Records H – 408

8 – Bilbao Song (Bertold Brecht / Kurt Weill)

Gil Evans orchestra, Keg Johnson (tb), Jimmy Knepper (tb),Tony Studd ( bass tb), Bill Barber (tuba), Charlie Persip et Elvin Jones (percussions), John Coles (tp), Phil Dunkel (tp), Ray Beckenstein (as, fl, piccolo), Budd Johnson (ts, ss), Bob Tricarico (bassoon, fl , piccolo), Ray Crawford (g), Ron Carter (b), Gil Evans (p) - LP Out Of The Cool, 1961 - Impulse ! AS – 4

9 – Lost In The Stars (Maxwell Anderson / Kurt Weill)

Tony Bennett (vocal) & Basie Orchestra : trompette : Thad Jones, Wendell Culley, Snooky Young, Joe Newman : trombone : Henry Cocker, Benny Powell, Al Grey ; Marshall Royal (as, cl), Frank Wess (as, ts, fl), Billy Mitchell et Frank Foster (ts), Charlie Fowlkes (bs), Ralph Sharon (p, arr), Freddie Green (g), Eddie Jones (b), Sonny Payne (dr), Count Basie (conductor) - LP In Person, 22 décembre 1958 - Columbia CL – 1294

10 – Speak Low (Ogden Nash / Kurt Weill)

Chris Connor (vocal), Mundell Lowe (g), George Duvivier (b), Ed Shaughnesy (dr), Stan Free (p, sans doute le pseudonyme d’un pianiste connu) - LP Chris Craft - 195 Atlantic 1290

11 – Lonely House (Maxwell Anderson / Kurt Weill)

Abbey Lincoln (vocal), Kenny Dorham (tp), Wynton Kelly (p), Les Spann ( g), Sam Jones (b), Philly Joe Jones (dr), LP Abbey Is Blue, 1959 - Riverside RLP 12 - 308

12 – September Song (Maxwell Anderson / Kurt Weill)

Walter Huston, orchestra conducted by Maurice Abravanel - 24 novembre 1938 - Brunswick 8272

13 – Speak Low (Ogden Nash / Kurt Weill)

Dick Hyman (p) - LP September Song, Dick Hyman plays the music of Kurt Weill, 1953 - Proscenium CE 4001

14 – It Never Was you (Maxwell Anderson / Kurt Weill)

Dick Hyman (p) - LP September Song, Dick Hyman plays the music of Kurt Weill, 1953 - Proscenium CE 4001

15 – Foolish Heart (Ogden Nash / Kurt Weill)

Dick Hyman (p) - LP September Song, Dick Hyman plays the music of Kurt Weill, 1953 - Proscenium CE 4001

16 – Speak Low (Ogden Nash / Kurt Weill)

Christiane Legrand (vocal) et Frank Aussman (aka, Jean- Michel Defaye) et son orchestre ; Stéphane Grappelli (solo violon) - LP Chansons de Kurt Weill, de l’Opéra de Quat’Sous à September Song, 1960 - Philips Réalités / Philips V 4

17 – September Song (Maxwell Anderson / Kurt Weill)

Jean-Michel Defaye (aka Frank Aussman) et son orchestre, Stéphane Grappelli ( solo violon) - LP Chansons de Kurt Weill, de l’Opéra de Qat’ Sous à September Song, 1960 - Philips Réalités / Philips V4

18 – Mack The Knife / Moritat (Bertold Brecht / Kurt Weill)

Dick Hyman Trio - LP Moritat, 1956 - MGM SP 1164

DISCOGRAPHIE - CD3

1 – Speak Low (Ogden Nash / Kurt Weill)

Sarah Vaughan (vocal), Ronnell Bright (p), Richard Davis (b), Roy Haynes ( dr) - LP After Hours at the London House, 1958 - Mercury MG 20383

2 – September Song (Maxwell Anderson / Kurt Weill)

Sarah Vaughan (vocal), Clifford Brown (tp), Paul Quinichette (ts), Herbie Mann (fl), Jimmy Jones (p), Joe Benjamin (b), Roy Haynes (dr) - LP Sarah Vaughan - Emarcy 6372 478

3 – Wie Man Sich Bettet ( Bertold Brecht / Kurt Weill)

Andre Previn (p), Jay Jay Johnson (tb), Red Mitchell (b), Frank Capp (dr) - LP Andre Previn and J.J. Johnson play Weill’s Mack The Knife and Bilbao Song and other music from Three Penny Opera, Happy End and The Rise and Fall of City of Mahagonny, 31 Décembre 1961 - Columbia Records CL 1741

4 – Speak Low (Ogden Nash / Kurt Weill)

Chet Baker (tp), Gerry Mulligan (bs), Carson Smith (b), Larry Bunker (dr) - 7 mai 1953 - Riverside

5 – September Song (Maxwell Anderson / Kurt Weill)

Chet Baker ( tp), Kenny Burrell( g), Paul Chambers (b), Connie Kay (dr) - LP Chet, 30 décembre 1958 ou 19 janvier 1959 - Riverside RLP 1135

6 – My Ship (Ira Gershwin / Kurt Weill)

Jerry Southern (vocal), orchestra directed by Camarata, 6 juillet 1956 - Decca DL 8394

7 - Mack The Knife (Bertold Brecht / Kurt Weill)

Bobby Darin (vocal) - LP That’s All, London, 1958 - Records HA - E 2172

8 – Speak Low (Ogden Nash /Kurt Weill)

Chico Hamilton (dr), Eric Dolphy (as , fl), Dennis Budimir (g), Nate Gershman (cello), Wyatt Ruther (b) + strings orchestra conducted by Fred Katz - LP Chico Hamilton Quintet with strings, 1959 - Warner Bros 1245

9 – September Song (Maxwell Anderson / Kurt Weill)

Chico Hamilton (dr), Paul Horn ( as, ts, fl, cl), John Pisano (g), Fred Katz (cello), Carson smith (b) - LP Chico Hamilton Quintet, Pacific Jazz 1225 - octobre 1956

10 - Overture (Bertold Brecht / Kurt Weill)

Andre Prévin (p), J.J. Johnson ( tb), Red Mitchell (b), Frank Capp (dr) - 31 Décembre 1961 - Columbia Records CL 1741

11 – Bilbao Song ( Bertold Brecht / Kurt Weill)

Andre Previn (p), J.J. Johnson ( tb), Red Mitchell (b), Frank Capp (dr) - 31 Décembre 1961 - Columbia Records CL 1741

12 – Barbara Song ( Bertold Brecht / Kurt Weill)

Andre Prévin (p), J.J. Johnson (tb), Red Mitchell ( b), Frank Capp (dr) - 31 Décembre 1961 - Columbia Records CL 1741

13 – Seeraüber Jenny ( Bertold Brecht / Kurt Weill)

Andre Previn (p), J.J. Johnson (tb), Red Mitchell (b), Frank Capp (dr) - 31 Décembre 1961 - Columbia Records CL 1741

14 – Mack The Knife ( Bertold Brecht / Kurt Weill)

Andre Previn (p), J.J. Johnson (tb), Red Mitchell ( b), Frank Capp (dr) - 31 Décembre 1961 - Columbia Records CL 1741

15 – Surabaya Johnny (Bertold Brecht / Kurt Weill)

Andre Previn (p), J.J. Johnson (tb), Red Mitchell (b), Frank Capp (dr) - 31 Décembre 1961 - Columbia Records CL 1741

16 – Unzulanglichkeit (Bertold Brecht / Kurt Weill)

Andre Previn (p), J.J. Johnson (tb), Red Mitchell (b), Frank Capp (dr) - 31 Décembre 1961 - Columbia Records CL 1741

17 – September Song (Maxwell Anderson / Kurt Weill)

Betty Roché (vocal), Jimmy Forest (ts), Jack Mc Duff (org), Bill Jennings (g), Wendell Marshall(b), Roy Haynes (dr) - LP Singin’ & Swingin, 1960 - Prestige PRLP 7187 B

18 – Moon-Faced and Starry-Eyed (Langston Hughes / Kurt Weill)

Dick Hyman (p) - LP September Song, Dick Hyman plays the music of Kurt Weill, 1953 - Proscenium CE 4001

Lors des années 1950, les artistes américains des mondes du jazz et de la chanson s’emparèrent des airs de Kurt Weill issus des pièces de son théâtre musical conçues aux USA et montées avec succès à Broadway. Ils les inscrivirent définitivement dans le Great American Songbook ; gommant ainsi l’imagerie berlinoise et brechtienne habituellement attachée à l’œuvre du compositeur allemand du célébrissime Opéra de Quat’ Sous.

Teca Calazans et Philippe Lesage

During the Fifties, American artists from the world of jazz and songs turned to Kurt Weill and the melodies that came from his music for the theatre, notably the future Broadway hits that he created in the USA. Thanks to those artists, Weill’s songs went straight into the Great American Songbook for good, writing a new chapter that erased the Berlin/Brecht imagery usually linked to the German composer of the world-famous Threepenny Opera.

Teca Calazans et Philippe Lesage

CD1

1) LOST IN THE STARS (Abbey Lincoln) 4’10

2) SPEAK LOW (Lena Horne) 3’28

3) MORITAT (Sonny Rollins) 10’04

4) SEPTEMBER SONG (Nat King Cole & G. Shearing) 2’59

5) MACK THE KNIFE (Ella Fitzgerald) 4.46

6) MY SHIP (Miles Davis) 4’25

7) MOON-FACED AND STARRY-EYED (Johnny Mercer) 3’02

8) SPEAK LOW (Billie Holiday) 4’27

9) MACK THE KNIFE (Louis Armstrong) 3’54

10) SEPTEMBER SONG (Red Norvo Trio) 3’31

11) SPEAK LOW (Anita O’Day) 2’35

12) MACK THE KNIFE (Anita O’Day) 3’08

13) MY SHIP (Ernestine Anderson) 3’40

14) SEPTEMBER SONG (Django Reinhardt) 2’33

15) SEPTEMBER SONG (Joe Loco) 3’04

16) SPEAK LOW (Henri Salvador) 4’28

17) MOON–FACED AND STARRY-EYED (Max Roach) 2’53

18) SPEAK LOW (Max Roach) 2’50

CD 2

1) SPEAK LOW (Booker Ervin) 6’59

2) MACK THE KNIFE (Erroll Garner) 4’28

3) MY SHIP (Anita O’Day) 2’42

4) HERE, I’LL STAY (Gerry Mulligan) 4’59

5) SEPTEMBER SONG (Frank Sinatra) 3’07

6) MACK THE KNIFE (Bing Crosby) 3’54

7) SEPTEMBER SONG (Art Tatum) 3’22

8) BILBAO SONG (Gil Evans Orchestra) 4’12

9) LOST IN THE STARS (Tony Bennett & Count Basie Orch) 3’59

10) SPEAK LOW (Chris Connor) 2’34

11) LONELY HOUSE (Abbey Lincoln) 3’40

12) SEPTEMBER SONG (Walter Huston) 2’53

13) SPEAK LOW (Dick Hyman) 1’53

14) IT NEVER WAS YOU (Dick Hyman) 3’01

15) FOOLISH HEART (Dick Hyman) 2’12

16) SPEAK LOW (Christiane Legrand) 2’37

17) SEPTEMBER SONG (Jean-Michel Defaye) 2’51

18) MACK THE KNIFE (Dick Hyman Trio) 2’16

CD3

1) SPEAK LOW (Sarah Vaughan) 4’50

2) SEPTEMBER SONG (Sarah Vaughan) 5’47

3) WIE MAN SICH BETTET (Andre Previn / J.J. Johnson) 6’07

4) SPEAK LOW (Chet Baker) 2’09

5) SEPTEMBER SONG (Chet Baker) 3’03

6) MY SHIP (Jerry Southern) 3’55

7) MACK THE KNIFE (Bobby Darin) 3’08

8) SPEAK LOW (Chico Hamilton) 2’28

9) SEPTEMBER SONG (Chico Hamilton) 3’35

10) OVERTURE (Andre Previn / J.J. Johnson) 5’02

11) BILBAO SONG (Andre Previn / J.J. Johnson) 4’04

12) BARBARA (Andre Previn / J.J. Johnson) 6’05

13) SEERAÜBER JENNY (Andre Previn /J.J. Johnson) 4’20

14) MACK THE KNIFE (Andre Previn / J.J. Johnson) 4’52

15) SURABAYA JOHNNY (Andre Previn / J.J. Johnson) 4’14

16) UNZULANGLICHHKEIT (Andre Previn / J.J. Johnson) 4’52

17) SEPTEMBER SONG (Betty Roché) 2’11

18) MOON-FACED AND STARRY-EYED (Dick Hyman) 2’19