- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

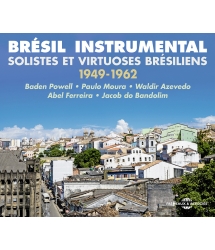

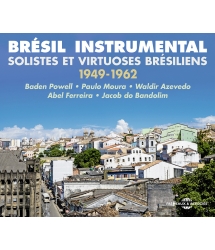

BADEN POWELL • PAULO MOURA • WALDIR AZEVEDO • ABEL FERREIRA • JACOB DO BANDOLIM…

Ref.: FA5624

Artistic Direction : TECA CALAZANS ET PHILIPPE LESAGE

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Total duration of the pack : 3 hours 13 minutes

Nbre. CD : 3

BADEN POWELL • PAULO MOURA • WALDIR AZEVEDO • ABEL FERREIRA • JACOB DO BANDOLIM…

BADEN POWELL • PAULO MOURA • WALDIR AZEVEDO • ABEL FERREIRA • JACOB DO BANDOLIM…

In Brazil, instrumental music went through many changes from the early Fifties to the Sixties, a vital period in which the last fl ashes of certain virtuosos mingled with innovations from musicians who went on to seduce the whole world, among them Jacob do Bandolim, Baden Powell or Paulo Moura. Here, in a certain fashion, the singers launching the theme’s development were replaced by solo instruments, with improvisations that took place in a very different manner from the rules of jazz. Teca CALAZANS et Philippe LESAGE

LUIZ GONZAGA • SIVUCA • CHIQUINHO DO ACCORDEON •...

THE FREMEAUX & ASSOCIES RECORDINGS 1994 -1996

CATALOGUE KUARUP 1977 - 2004

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Migalhas De AmorJacob do BandolimJacob do Bandolim00:03:081952

-

2Forro De GalaJacob do BandolimJacob do Bandolim00:02:291952

-

3BrasileirinhoWaldir AzevedoWaldir Azevedo00:02:331949

-

4Pedacinho Do CeuWaldir AzevedoWaldir Azevedo00:03:211951

-

5Do Jeito Que A Gente QuerBaden PowellEd Lincoln00:02:361961

-

6InsoniaBaden PowellBaden Powell00:02:551961

-

7Luar De AgostoBaden PowellBaden Powell00:03:151961

-

8Valsa TristeMoura PauloRadames Gnattali00:04:471959

-

9PenumbraMoura PauloRadames Gnattali00:05:551959

-

10CariocaMoura PauloRadames Gnattali00:03:351959

-

11Espinha De BacalhauSeverino Araujo e sua Orquestra TabajaraSeverino Araujo00:03:171959

-

12Doce MelodiaAbel FerreiraAbel Ferreira00:02:091962

-

13Doce MentiraAbel FerreiraAbel Ferreira00:02:321962

-

14TernuraAbel FerreiraLyrio Panicali00:02:231962

-

15AcariciandoAbel FerreiraAbel Ferreira00:02:591962

-

16AlvoradaRadames com seu SextetoJacob Bittencourt00:03:081960

-

17Na Cadencia Do BaiaoRadames com seu SextetoLuiz Bittencourt00:02:461960

-

18O Apito No SambaRadames com seu SextetoLuiz Bandeira00:02:581960

-

19Um Chorinho Em SerestaLuiz AmericanoPaulo Patricio00:02:541960

-

20Ve Se GostasWaldir AzevedoWaldir Azevedo00:03:261950

-

21Doce De CocoJacob do BandolimJacob do Bandolim00:02:581951

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Chorando BaixinhoAbel FerreiraAbel Ferreira00:02:401962

-

2Saxofone Porque ChorasAbel FerreiraRatinho00:03:231962

-

3E Do Que HaAbel FerreiraLuis Americano00:03:011962

-

4MonotoniaMoura PauloRadames Gnattali00:03:591959

-

5RomanceMoura PauloRadames Gnattali00:04:141959

-

6CarioquinhaWaldir AzevedoWaldir Azevedo00:02:551949

-

7De Papo Pro ArJose MenezesJoubert De Carvalho00:02:161950

-

8GraunaJacob do BandolimJoao Pernambuco00:02:521950

-

9OdeonJacob do BandolimErnesto Nazareth00:02:311952

-

10Primeiro AmorRadames com seu SextetoHernani Silva00:02:071960

-

11BatuqueRadames com seu Sexteto e EduEdu00:02:071960

-

12Foi A NoiteRadames GnattaliAntonio Carlos Jobim00:03:111960

-

13Minha PalhocaBaden PowellJota Cascata00:02:031961

-

14Preludio Ao CoracaoBaden PowellBaden Powell00:01:141961

-

15Luz NegraBaden PowellNelson Cavaquinho00:02:331961

-

16Improviso Bossa NovaBaden PowellBaden Powell00:02:061961

-

17Luzes Do RioLuiz BonfaLuiz Bonfa00:02:281959

-

18MafuaJose MenezesArmandinho00:02:241957

-

19Abismo De RosasDilermando ReisJacomino Americo00:03:581961

-

20MelancoliaLuiz AmericanoHenriqueta Ribeiro00:03:181960

-

21DinoraAltamiro CarrilhoBenedito Lacerda00:02:181959

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Choro TypicoLaurindo AlmeidaHeitor Villa Lobos00:05:471959

-

2Prelude n°5Laurindo AlmeidaHeitor Villa Lobos00:03:331959

-

3Schottisch ChoroLaurindo AlmeidaHeitor Villa Lobos00:04:381959

-

4Sons De CarrilhoesDilermando ReisJoao Pernambuco00:02:481961

-

5Noite De LuaDilermando ReisDilermando Reis00:03:141961

-

6MagoadoDilermando ReisDilermando Reis00:02:421961

-

7Despertar Da MontanhaJacob do BandolimEduardo Souto00:02:571949

-

8AtlanticoJacob do BandolimErnesto Nazareth00:02:591952

-

9SimplicidadeJacob do BandolimJacob do Bandolim00:02:451950

-

10DevaneioPaulo MouraRadames Gnattali00:04:371959

-

11NostalgiaPaulo MouraRadames Gnattali00:03:581959

-

12Sempre A SonharPaulo MouraRadames Gnattali00:03:431959

-

13SedutorAbel FerreiraOswaldo Lyra00:02:051962

-

14Fluido Da SaudadePowell BadenBaden Powell00:04:001961

-

15Dum Dum DumPowell BadenBaden Powell00:01:191961

-

16EncabuladoJose MenezesJose Menezes00:02:351957

-

17DelicadoWaldir AzevedoWaldir Azevedo00:02:331950

-

18Capricho NortistaRadames com seu SextetoHumberto Teixeira00:04:491960

-

19Antigamente Era AssimLuiz AmericanoLuis Americano00:03:071960

-

20Luiz Americano Em BrasiliaLuiz AmericanoLuis Americano00:02:241960

-

21De Passagem Pela ArabiaLuiz AmericanoLuis Americano00:03:251960

Bresil Instrumental FA5624

BRÉSIL INSTRUMENTAL

SOLISTES ET VIRTUOSES BRÉSILIENS

1949-1962

Baden Powell • Paulo Moura • Waldir Azevedo

Abel Ferreira • Jacob do Bandolim

La musique instrumentale brésilienne est si belle qu’elle méritait d’être illustrée dans ses composantes des années 1950. Cette anthologie est donc complémentaire aux deux travaux déjà réalisées pour les Editions Frémeaux : le premier exercice couvrait les fondations du premier cinquantenaire du XXe siècle, le second travail intitulé « Choro Contemporain » puisait dans les archives des années 1980/2000 du label carioca Kuarup. Cette fois-ci, l’angle du regard est mis sur la virtuosité instrumentale et l’improvisation en une acceptation différente de celle développée dans le jazz.

Petit rappel : l’identité musicale du pays s’est forgée de la rencontre, plus ou moins fusionnelle, des rythmes africains, des mélopées du Nordeste - où percent les influences indiennes et lusitaniennes - avec les emprunts mélodiques et harmoniques européens. C’est de cette mixture que naitra la musique instrumentale brésilienne souvent assimilée à juste titre au choro. Lorsqu’elle est mal interprétée, cette musique devient insipide, surannée, sans corps ni âme alors qu’en vérité elle n’est que raffinement et sensualité.

Musique instrumentale brésilienne : le Choro

Né vers 1870, essentiellement à Rio, il s’est forgé au fil du temps, en assimilant les danses de salon européennes (valse, polka, mazurka, quadrille…) ainsi que la habanera qui nourrissait à l’époque toute l’Amérique Latine. Certains disent que le choro est la première véritable expression musicale née au Brésil parce qu’il est la matrice qui donne ses caractéristiques à la musique de ce pays : syncope « flottante », fusion des inflexions mélodiques et harmoniques européennes et des accents rythmiques africains. Les grandes figures tutélaires en furent, au détour du XXe siècle, Joaquim Callado, Chiquinha Gonzaga et Ernesto Nazareth mais c’est Pixinguinha puis le « regional » de Benedito Lacerda qui fixeront, dans les années trente, son équilibre délicat. Une révolution s’est alors opérée : la guitare remplace le piano dans les circonvolutions mentales. La beauté du choro tient à ses nuances, ses modulations et sa dynamique qui ne peuvent être portées que par des stylistes à l’image des instrumentistes à la forte personnalité qui illustrent cette anthologie.

Une autre esthétique

Les petits fonctionnaires et employés dans de grandes villes comme Rio ou São Paulo comme les « violeiros » du Nordeste étaient le plus souvent des musiciens autodidactes mais ils ne manquaient ni d’intelligence musicale ni de dextérité technique. Il n’est toutefois pas surprenant que les instruments valorisés, du moins dans le genre choro, soient, dans les premiers temps, parce qu’ils répondent bien à trois critères essentiels de musicalité, de coût et de manipulation, la flûte - instrument mélodique - la guitare - instrument rythmique et mélodique - et le cavaquinho - chargé de « centrer » le rythme. Mais assez rapidement tous les instruments, qu’ils soient à vent ou à cordes, s’imposent dans le paysage aux côtés des petites percussions et tous les instruments sont susceptibles de répondre à de courtes improvisations sur les grilles harmoniques… mais le choro ne valorise pas cette démarche de l’improvisation solitaire si caractéristique du jazz son esthétique étant autre : l’instrument qui prend en charge le leadership sans le lâcher est la voix soliste qui propulse la mélodie en l’enrichissant de modulations et d’ornementations ; on pourrait aller jusqu’à affirmer que l’instrument soliste se substitue au chanteur absent, à preuve, les disques de Jacob do Bandolim exemplaires à cet égard.

La posture du soliste

Pour être reconnu comme soliste, bien sûr, il faut du talent, de la maîtrise technique et des idées mais être soliste, se projeter comme soliste, est une posture psychologique avant tout. D’une certaine manière, on pourrait aller jusqu’à énoncer que le soliste est programmé pour l’être dès le plus jeune âge avant même de maîtriser le doigté instrumental et le discours musical. S’il est bien vrai que certains instruments mélodiques comme la flûte, la clarinette, le bandolim favorisent la prise de rôle du soliste, il n’en reste pas moins que les caractéristiques de la personnalité du musicien joue un rôle primordial. Comment expliquer alors que le compositeur Waldir Azevedo ait hissé son instrument, le cavaquinho, au rang d’instrument soliste déroulant avec une virtuosité confondante la mélodie si ce n’est par son tempérament alors qu’à l’opposé, le comportement pudique de Meira, cet excellent guitariste et compositeur qui fut le professeur de Baden Powell, de Rafael Rabello et de Mauricio Carrilho, le maintient volontairement dans l’ombre du soliste comme guitariste en charge du soutien rythmique et mélodique ?

Les Maîtres du passé

Une précédente anthologie (Choro-FA166), qui esquissait les évolutions du choro de sa naissance vers 1870 aux années 1940, livrait des enregistrements historiques. En s’y reportant, il est possible de mesurer ce que furent le talent et la créativité d’instrumentistes comme Pattápio Silva, Pixinguinha, Benedito Lacerda, Luperce Miranda, Americo Jacomino « Canhoto » ou João Pernambuco. Leurs prestations insensiblement firent évoluer la gestation d’un genre, inscrivant dans le marbre certains codes et finissant par donner une identité propre à la musique brésilienne. Il est donc utile de revenir rapidement sur leur parcours afin de mesurer l’apport personnel de chacun en sachant que le système d’enregistrement mécanique des années 1920 favorise la captation des cuivres et des instruments à anches au détriment des instruments à cordes pincées et des percussions mais que les choses se corrigent au profit des guitares, du bandolim et du cavaquinho après les années 1930. Le son, qui s’améliore au fil des évolutions technologiques, est dans l’ensemble suffisamment clair et présent pour prendre avec plaisir la température de l’époque et pour s’enchanter à l’écoute des solos de flûte de Pixinguinha en ces années là.

Petites Biographies de quelques anciens

Si quelques virtuoses ont marqué leur temps, la figure centrale de la première moitié du XXe siècle n’en reste pas moins Pxinguinha qui signe des thèmes inoubliables, des solos de flûte épous-touflants tout en instillant une forme de classicisme délicat.

Pattápio Silva (1880-1907)

Ce musicien né dans une famille modeste de Rio et qui a commencé par être barbier, fut un tel flûtiste virtuose qu’il prendra la succession de Joaquim Callado à l’Instituto Nacional de Musica, qu’il se présentera devant le président de la République tout en ayant conquis par ailleurs le cœur du grand public. Ses enregistrements pour Casa Edison dévoilent un jeu fluide au service de thèmes balançant entre musique classique et populaire. Que serait-il advenu si la diphtérie ne l’avait pas emporté en cinq jours à l’âge de 26 ans ?

Américo Jacomino « Canhoto » (1889-1928)

Les exécutions en quartet ou en solo de ce fils d’émigrants italiens, pauliste de naissance, musi-cien autodidacte, guitariste gaucher qui n’avait pas interverti les cordes en acier (son surnom de « canhoto » veut dire gaucher) sont d’une modernité inouïe ; pour s’en convaincre, il suffit d’écouter l’enregistrement qu’il a réalisé de Abismo de Rosas. Il fut d’ailleurs le premier à enregistrer en solo total en un jeu plein de vibratos. La valse Abismo de Rosas (le titre initialement choisi était Acordes de Violão), popularisée par la version de Dilermando Reis que l’on peut découvrir dans cette anthologie, est devenue un standard du répertoire des guitaristes du monde entier.

João Pernambuco (1883-1947)

Après avoir acquis son savoir auprès des « violeiros » et « cantadores » du sertão du Nordeste, avoir vécu un temps à Recife, il débarque à Rio en 1904, compose Luar do Sertão, la valse Sonho de Magia, le choro Magoado ainsi que Cabocla do Caxanga qui sera le grand succès du car-naval de 1914. João Pernambuco, qui était un autodidacte humblement orgueilleux, ne sut malheureusement pas valoriser son talent singulier auprès des compagnies discogra-phiques alors que sa musique, qui emprunte à plusieurs genres et pas seulement au choro, est d’une densité à fendre l’âme. Guitariste et compositeur d’une importance primordiale, il fut oublié dans les dernières décades de sa vie bien qu’étant un ami proche de Villa-Lobos qui lui sera d’un soutien constant.

Benedito Lacerda (1903-1958)

Ce fils d’immigrants italiens fut un flûtiste passionnant et un bon compositeur de valses et de sambas qui marqueront les esprits de son époque. Son rôle fut aussi primordial dans la géométrie sonore de ce qui sera appelé un « regional » (flûte, saxophone, guitare 6 cordes, guitare 7 cordes, cavaquinho et pandeiro). Il se sera entouré de musiciens exceptionnels et il aura été la cheville ouvrière de la relance de la carrière de Pixinguinha avec l’enregistrement de 34 plages fastueuses de la plume du Maître, entre 1946 et 1950, où ce dernier déploie des contrechants novateurs au saxophone ténor.

Pixinguinha (1898-1973)

S’il est un virtuose dans la musique brésilienne, c’est bien Pixinguinha, s’il est un compositeur qui précède le talent d’un Antonio Carlos Jobim, c’est bien Pixinguinha et les deux hommes qui surent s’apprécier avaient la réputation d’être la bonté même. Celui que sa grand-mère aimait appeler « Pizindim » (enfant bon et doux en dialecte africain) était né Alfredo da Rocha Viana Junior au sein d’une fratrie de quatorze enfants. Flûtiste amateur éclairé, son père collectionnait les partitions et était entouré de musiciens- toutes races confondues - très introduits dans le monde du choro naissant. Il n’est donc pas surprenant que Pixinguinha ait embrassé dès l’âge de 15 ans la carrière de musicien professionnel (cas non rarissime à l’époque). Il sera « tutoré » par son frère China et par Irineu de Almeida / « Batina » (il ne portait que des soutanes) et rejoindra vite Os Batutas, un groupe à géométrie variable essentiel dans l’éclosion du choro. C’est dans cet environnement favorable que les talents de flûtiste et de compositeur de Pixinguinha s’épanouissent avant l’apogée des années 1930 (de cette époque, nous reste des compositions comme Rosa, « 1X0 », Sofre Porque Queres ainsi que des enregistrements de solos de flûte à l’architecture parfaite). Alors qu’il avait baigné, enfant et adolescent, dans la matrice africaine (il ne faut pas oublier que la fin de l’esclavage, au Brésil, ne date que de 1888 et que les mères de ses copains Donga et Heitor dos Prazeres étaient des bahianaises, prêtresses du candomble) et qu’il aimait s’y ressourcer, Pixinguinha établit, sans le savoir ni le vouloir consciemment, les codes du classicisme du choro, codes dont se revendiquera Jacob do Bandolim. Les derniers feux de Pixinguinha se font au sein du « regional » de Benedito Lacerda où Pixinguinha improvise de merveilleux contre chants au saxophone ténor ainsi qu’au sein de « A Velha Guarda » emmenée par Almirante. En plus de ses talents de flûtiste virtuose et de compositeur, il était également un arrangeur recherché par tous les chanteurs en vogue.

Luperce Miranda (1904-1977)

Ce musicien nordestin marque l’histoire musicale de son pays en devenant le premier bandoliniste soliste à être enregistré. La caractéristique de son jeu : un style napolitain virtuose tout en ornementation.

Radamés Gnattali (1906 -1988)

Même si on le retrouve actif et impactant jusque dans les années 1980 auprès de la jeune génération, Radamés Gnattali doit être impérativement men-tionné dans le flux des virtuoses et solistes des années 1930 à 1960. Lui aussi fils d’émigrés italiens mais né à Porto Alegre, dans ce sud du Brésil qui jouxte l’Argentine et l’Uruguay, il sera tant fasciné par Ernesto Nazareth qu’il entend jouer au cinéma Odéon lorsqu’il monte à Rio la fin des années vingt qu’il va, lui le pianiste concertiste classique, dériver vers la musique d’essence populaire. Il sera un arrangeur autant recherché (il est le signataire de la version princeps d’Aquarela do Brasil) que Pixinguinha et un compositeur fécond d’œuvres de facture classique (Concerto N° 1 pour guitare et orchestre qui sera donné par Laurindo Almeida, Suite Retratos offerte à Jacob do Bandolim, Cantata Maria – Jesus dos Anjos …) ou populaire (Valsa Triste, Amargura par exemple). Dans cette anthologie, on pourra découvrir les versions du saxophoniste Paulo Moura, alors âgé de 28 ans, qui signe son premier disque sous son nom en interprétant huit des compositions de Radamés. Avec le batteur Luciano Perrone et le clarinettiste Luiz Americano, Radamés avait monté Trio Carioca à l’image du trio de Benny Goodman (le thème Cabuloso reste gravé dans le répertoire national) puis un Quintet avec, entre autre, Chiquinho do Acordeon et José Menezes.

A propos des virtuoses de notre anthologie

Les années 50 et le début des années 60 sont une époque charnière où s’entremêlent les derniers feux de certains virtuoses comme Luiz Americano, Dilermando Reis voire Abel Ferreira aux innovations de jeunes pousses. Le disque de Paulo Moura est d’ailleurs intéressant à ce titre puisqu’il associe la génération des « vieux lions » Radamés Gnattali (à la fois auteur de tous les titres et pianiste des sessions), Trinca (batterie) et Vidal (contrebasse) à la génération montante (Baden a juste 21 ans et Paulo Moura à peine 28 ans). Commençons nos petits portraits par les musiciens les plus représentatifs d’une génération qui va, peu à peu, s’éteindre :

Luiz Americano (1900 -1960)

Ce clarinettiste et saxophoniste nordestin laisse aussi quelques compositions qui sont loin d’être négligeables. Son jeu très expressif le pousse parfois aux lisières des musiques de cirque. Il avait été membre du Trio Carioca fondé par Radamés Gnattali, avait fait partie de la Velha Guarda emmenée par Donga et Pixinguinha et enregistré Tocando pra vôcé, en 1940, lors des sessions sur le navire Uruguai organisées par le chef d’orchestre Leopold Stokovski sur les recommandations de Villa Lobos pour Columbia.

Severino Araujo (1917-2012)

Clarinettiste originaire du nordeste, il avait monté l’Orquestra Tabajara qui fit les beaux jours des « gafieiras » (dancings) pendant plus d’une cinquantaine d’années sur le modèle des big bands américains. Il a laissé deux magnifiques compositions devenues des standards incontournables : Um Chorinho em aldeia et Espinha de Bacalhau.

José Menezes (1921-2013)

Comme tous les nordestins, il vient à Rio de Janeiro pour donner une réelle envergure à sa carrière. Il imite ses confrères en se produisant dans les émissions publiques des principales radios et il jouera même en duo, un temps, avec Garoto, un autre poly-instrumentiste talentueux. Lui-même jouait aussi bien de la guitare acoustique, de la guitare électrique que du bandolim ou du cavaquinho. Il a longtemps été un membre essentiel du Quinteto de Radames Gnattali et certaines de ses compositions (Nova Ilusão, Comigo é assim) ont connu un succès qui ne se démentit pas.

Dilermando Reis (1916-1977)

Il avait transmis son savoir acquis auprès du guitariste aveugle Levino da Conceição à Bola Sete et même au Président Jucelino Kubitschek. Il restera attaché à Radio Nacional pendant près de vingt ans et enregistrera de très nombreux LP chez Continental dont le fameux Abismo de Rosas (quatre titres présents dans cette anthologie en sont extraits). Il laisse aussi des compositions comme Magoado ou Noite de Lua ainsi que de très belles interprétations de thèmes venus du monde de la musique classique.

Luis Bonfá (1922-2001)

Sa notoriété vient de deux de ses compositions incluses dans le film Orfeu Negro : Manhã de Carnaval et samba de Orfeu qui font qu’on le catalogue comme un des créateurs de la bossa nova, ce qu’il n’était pas, ne serait-ce que pour être d’une génération largement antérieure. C’est d’avoir été le guitariste de la pièce Orfeu da Conceição de Antonio Carlos Jobim et Vinicius de Moraes, en 1956, qui lui avait permis d’être le guitariste de la BO du film Orfeu Negro, en 1958 et d’y voir inclus, malgré les réserves du réalisateur Marcel Camus, les deux thèmes mentionnés plus haut. Il a longtemps vécu et enregistré aux USA mais sa production artistique est souvent assez médiocre.

Abel Ferreira (1915-1980)

Venu de l’Etat du Minas Gerais, il enregistre en 1942, pour Columbia Chorando Baixinho, un thème fétiche qui restera sa signature. Clarinettiste et saxophoniste (alto et ténor), il aura été très recherché par toutes les « étoiles » de la chanson populaire. Ce digne héritier de Luiz Americano se retire progressivement au début des années 70. C’est un des représentants les plus dignes du choro.

Waldir Azevedo (1923-1980)

Il a donné ses lettres de noblesse au cavaquinho en tant que soliste, ce qui est, non pas une hérésie, mais une rareté. Il se sera formé aux côtés de Dilermando Reis avant de monter son propre groupe en 1947. Auteur de thèmes enjoués qui connaitront un succès phénoménal au Brésil et à l’étranger, dans les années 50, il aura enregistré plus de cinquante 78 tours et une vingtaine de LP. Brasileirinho, Delicado, ses deux plus grands succès ne peuvent vous être inconnus ; même Dr. John a enregistré Delicado en piano solo !

Laurindo Almeida (1917-1995)

Originaire de São Paulo, il s’éteindra à Los Angeles où il vécut dès les années 1940. Guitariste classique de formation et concertiste, il s’adonne aussi à la musique populaire, joue dans les « cassinos » et se produit dans les émissions de radio ainsi qu’aux sessions enregistrées par Columbia sur le « navire Uruguai » en 1940. Alors qu’il est invité pour une tournée de concerts classiques aux USA, il rejoint l’orchestre de Stan Kenton, enregistre plusieurs LP avec Bud Shank, Le Modern Jazz Quartet et Stan Getz. Il est aussi un compositeur reconnu de films et de series TV comme le Fugitif.

Jacob do Bandolim (1918-1969)

Comme si il y avait symbiose entre lui et son instrument de prédilection, Jacob Pick Bittencourt finit par devenir Jacob do Bandolim. Perfectionniste obsessionnel, imposant répétitions sur répétitions à ses musiciens, Jacob était reconnu pour être un personnage intransigeant et caustique. Il ne révérait qu’une seule personne : Pixinguinha, il est vrai un homme délicieux et un géant de la musique. Elevé dans le quartier populaire de Lapa, fils d’un petit pharmacien brésilien et d’une mère polonaise, il s’est toujours considéré comme un amateur (« je n’ai jamais vécu une minute uniquement de musique » disait-il ; il était par ailleurs auxiliaire de justice). Il professait que le choro doit être improvisé, ce qui selon lui, impliquait que l’instrumentiste apprenne parfaitement le thème pour être en mesure de le développer.

Lorsque Jacob déboule en 1947, avec sa fraicheur, sa spontanéité et son sens inné de la simplicité mélodique, les rides du temps accusent l’âge de Luperce Miranda. C’est que Jacob transfigure la manière de jouer de cet instrument au son ingrat. D’une précision rythmique inouïe, il est plus portugais et moins napolitain dans le son (il avait dans les années 1930 accompagné un chanteur portugais et s’était longuement frotté au fado). Comme l’écrit Pedro Amorim, bandoliniste né dans les années 1960, « il est la référence, l’école, le styliste incontestable ». Le 13 août 1969, il succombe à un second infarctus devant sa résidence, au retour d’une visite à Pixinguinha, avec qui il définissait le répertoire d’un disque en préparation autour des œuvres de son vénéré ami.

Paulo Moura (1932-2010)

Paulo Moura est un des rares « souffleurs » brésiliens à avoir acquis une certaine notoriété à l’étranger. Pauliste de naissance, fils d’un clarinettiste et chef d’orchestre, il rejoint à 27 ans l’Orchestre Symphonique du Théâtre Municipal de Rio de Janeiro. Dès cette époque, il se frotte parallèlement, à Cannonball Adderley et Herbie Mann car il est membre du sextet du pianiste Sergio Mendes et il participera même au fameux concert « Bossa Nova » du Carnegie Hall en 1962. Après un premier album sous son nom, en 1959, sur un répertoire de chansons de Radames Gnattali, il lance de belles productions dans les années 1960 et 1970 : Paulo Moura Hepteto, Paulo Moura Quarteto, Fibra et il dirige l’orchestre qui accompagne Milton Nascimento lors des concerts Milagre dos Peixes – Ao Vivo. Ayant composé une œuvre en hommage au centenaire de la fin de l’esclavage, il la dirigera en 1988 face à l’Orchestre Symphonique de Brasilia. En 1989, avec Confusão urbana, sububarna e rural, il donne un de ses meilleurs albums et il revint plus explicitement au choro avec Mistura e Manda. Il enregistrera aussi en duo avec Rafael Rabello Dois Irmãos, en 1992 et avec Yamandu Costa El Negro del Blanco. Indéniablement, Paulo Moura - qui ne manquait pas de magnétisme personnel ni d’un certain narcissisme - est une des références de la clarinette de son pays.

Baden Powell (1937-2000)

Roberto Baden Powell de Aquino (Baden Powell en hommage au fondateur du scoutisme; il est de coutume, au Brésil, d’affubler les enfants de prénoms de personnages historiques) est une figure majeure de la musique brésilienne de tous les temps et un des guitaristes essentiels de la musique populaire aux côtés de musiciens comme Django Reinhardt, Joe Pass, Jim Hall, Paco de Lucia, John Mac Laughlin.

Dans Deve Ser Amor, enregistrement réalisé à Rio de Janeiro par le flûtiste de jazz américain Herbie Mann en 1960, la personnalité du tout jeune Baden Powell explose au grand jour : le jeu du pouce impose une hypertrophie rythmique époustouflante et les cordes chantent. Alors que João Gilberto venait déjà de bouleverser le paysage sonore, Baden Powell ajoutait un nouveau saut qualitatif à la guitare brésilienne. Il allait vite s’imposer comme virtuose, comme compositeur et bien qu’il fut petit et sec comme une trique, il n’en imposait pas moins sa personnalité lors de ses prestations scéniques (il emportait toujours l’adhésion du public sur Samba da benção). Le milieu familial lui avait permis de baigner dans le monde du choro et du samba et dès l’âge de huit ans, il prenait de cours de guitare avec Jayme Florence « Meira », musicien du « regional » de Benedito Lacerda (lors de rencontres privées, j’ai pu mesurer le respect quasiment filial qu’il portait à son maître). Devenu musicien professionnel à seize ans, il compose Samba Triste (paroles de Billy Blanco) en 1956, chanson qui sera divulguée par Lucio Alves, une des voix majeures de l’époque. Dans la partie féconde de sa carrière, seulement deux paroliers – et pas des moindres - poseront leur poésie sur ses musiques : Vinicius de Moraes, (Os Afro-Sambas, Berimbau, Samba em preludio, Consolação…) et Paulo César Pinheiro (Lapinha, É de Lei, Refem da solidão). Il passe l’essentiel des années 1970 en Allemagne et en France, participe au spectacle de Claude Nougaro à l’Olympia et lors d’une longue et mémorable tournée. De santé fragile, il se produit moins les dernières années mais il offre, avec Rio das Valsas, un joli disque en 1994, qui d’une certaine manière le replonge dans le monde du choro de son enfance. Brésilien jusqu’au bout des ongles, il était impossible de le cataloguer comme faisant partie du mouvement de la bossa nova ou comme sambiste pur et dur ou comme guitariste éminent du choro même s’il était un peu tout cela à la fois, c’est-à-dire un peu noir, un peu blanc européanisé, moderne et en même temps enraciné dans la tradition. Il était avant tout un créateur porteur d’un monde personnel auquel le public restera fidèle jusqu’à la fin. Après son décès, la municipalité de Rio donnera son nom à une belle salle dans le quartier de Copacabana.

A propos des thèmes de notre anthologie :

Ils ne firent jamais partie des « people » dont les médias faisaient leurs choux gras mais les solistes virtuoses furent les artisans de l’identité de la musique du Brésil et ceux des années 1950 et 1960 contribuèrent largement à l’édification de l’édifice. Dans cette anthologie, l’angle du regard est mis sur la virtuosité instrumentale et l’improvisation en une acceptation différente de celle développée dans le jazz. C’est ce regard oblique qui nous amène à présenter les prestations de l’harmoniciste Edú da Gaita (Edú Kruni) et de Chiquinho do Acordeon d’autant que ces deux musiciens exceptionnels illustrent dans cette anthologie les facettes plutôt méconnues des musiques du nordeste. Une large place est laissée aux guitaristes qui plus que virtuoses sont des solistes à part entière dans la mesure où ils s’expriment souvent en solitaire. Il est utile toutefois de rappeler que la guitare fut longtemps perçue au Brésil comme un instrument sans noblesse plutôt synonyme de vagabondages et d’asociabilité. Il fut un temps où il n’était pas bon d’être noir, de se promener avec une guitare en bandoulière et de croiser la police. Le fait que Heitor Villa-Lobos ait aimé cet instrument au point de composer des Études et des Choros est à saluer d’autant que cela souligne bien son adhésion aux musiques populaires (il montait fréquemment au Morro da Mangueira pour rencontrer le compo-siteur Cartola et il recevait chez lui tous les dimanches João Pernambuco qui était alors bien oublié). Les versions que donne Laurindo Almeida des compositions de Villa Lobos sont passionnantes parce qu’elles n’ont pas la rigidité des versions des guitaristes du monde classique mais elles préservent la qualité du « son propre » inhérent au jeu classique que ne savent pas toujours valoriser les guitaristes populaires. Dilermando Reis était aussi un musicien à cheval sur l’interprétation d’œuvres de musique classique et de chansons populaires qu’il savait ennoblir par une virtuosité sans égale. De son côté, comme nous le soulignions dans la notule le présentant, Baden Powell projetait le jeu des cordes vers une autre synthèse qui marquera la fin du siècle à l’égal de celle d’un Jacob sur son bandolim. Ce dernier avait beau toujours faire référence au classicisme de Pixinguinha et du « regional » de Benedito Lacerda, il n’en ouvrait pas moins de nouveaux horizons. Au cours de trois « caravanes » en Europe autour de 1960 (c’est comme cela qu’on avait appelé ces tournées), Radamés et son Sexteto brossent un bon panorama de la musique brésilienne de l’époque. On notera au passage la modernité du jeu de Radamés tant dans ses phases en solo qu’en posture d’accompagnateur ainsi que la versatilité de José Menezes qui passe sans souci de la guitare électrique au cavaquinho ; le Sexteto de Radamés était vraiment une belle institution malheureusement trop méconnue en Europe.

Teca Calazans et Philippe LESAGE

© 2016 Frémeaux & Associés

INSTRUMENTAL BRAZIL

(1949-1962)

Soloists and Virtuosos of Brazil

Brazilian instrumental music is so beautiful that it fully deserved an illustration of its components in the Fifties. So this anthology complements the two sets already compiled for Frémeaux & Associés: the first covered the foundations of the 50th anniversary of the 20th century, while the second, entitled “Choro Contemporain”, drew music from the archives of the Rio de Janeiro label Kuarup in the years 1980-2000. This present set provides a perspective based on instrumental virtuosity and improvisation in a different sense from that developed in jazz. A brief reminder: the musical identity of the country was forged from the more or less intense, close encounter between African rhythms and songs of the Nordeste (engrained with their Indian and Lusitanian influences), and European borrowings in melody and harmony. It was this mixture which gave birth to the Brazilian instrumental music that is often likened (with good reason) to the choro. When badly performed, this music can become insipid, out-dated, and without body or soul, whereas in reality it is pure refinement and sensuality.

Brazilian instrumental music: the Choro

After appearing towards 1870, essentially in Rio, the choro was forged over time with the assimilation of salon dances from Europe (waltz, polka, mazurka, quadrille…) together with the habaneras that irrigated all of Latin America during that period. It is said that the choro was the first authentic musical expression born in Brazil, because it was the matrix that gave the music of that country its characteristics: “floating” syncopation, the fusion of European inflexions in melody and harmony, and African rhythmical accents. At the turn of the 20th century its great tutelary figures were Joaquim Callado, Chiquinha Gonzaga and Ernesto Nazareth, but, beginning in the Thirties, it was first Pixinguinha, then the “regional” of Benedito Lacerda, who fixed its delicate balance. Then a revolution occurred: the guitar replaced the piano in mental circumvolutions. The beauty of the choro lies in its nuances, in the modulations and dynamics that could only be carried by stylists such as the instrumentalists of great character who illustrate this anthology.

A new aesthetic

The minor civil servants and employees who were musicians in the immense cities of Rio or Sao Paulo, like the “violeiros” of the Nordeste, were most often self-taught, but lacked neither musical intelligence nor technical dexterity. But it is still no surprise that at first, the instruments that were preferred, at least where the choro genre is concerned, came to the fore because they answered three essential criteria in musicality, cost and manipulation: the flute (for melody), the guitar (for melody and rhythm), and the cavaquinho, which was charged with “focussing” rhythm. Rather quickly however, all the above, winds or strings, established themselves alongside small percussion; every instrument was capable of short, chord-based improvisations… but the choro had another aesthetic, and did not enhance this “solo improvisation” approach that characterizes jazz: the instrument that took charge of this leadership and didn’t let go was the solo voice, which propelled the melody by enriching it with modulations and ornamentation; one can even go so far as to say that the solo instrument was the substitute for an absent vocalist, and the records of Jacob do Bandolim provide exemplary proof of this.

The soloist’s pose

Being recognized as a soloist, of course, implies talent, technical mastery and ideas, but being a soloist, projecting oneself as a soloist, is above all a psychological pose. In some ways you could even go so far as to say that the soloist is programmed to be a soloist right from the beginning, before he or she even masters fingering and the musical discourse. While it is quite true that some melody instruments, like the flute, clarinet or bandolim [a Portuguese mandolin variant] favour the soloist-role, the character of the musician nevertheless remains crucial. How else can one explain that composer Waldir Azevedo elevated his cavaquinho to the rank of a solo instrument capable of deploying a melody with stunning virtuosity, through nothing more than his own temperament? Or that at the other extreme, the discretion and modesty of Meira — that excellent guitarist and composer who was the teacher of Baden Powell, Rafael Rabello and Mauricio Carrilho — deliberately kept him in the soloist’s shadows as a rhythm and melody guitarist?

The Masters of the past

A previous anthology entitled Choro (reference FA166) outlines the evolution of the genre from its birth in around 1870 up until the Forties; it draws on historic choro recordings, and listening to that set makes it possible to measure the talent and creativity displayed by such instrumentalists as Pattápio Silva, Pixinguinha, Benedito Lacerda, Luperce Miranda, Americo Jacomino “Canhoto” or João Pernambuco. Their performances imperceptibly caused the genre’s gestation to progress, indelibly engraving certain codes and finally giving it an identity proper to Brazilian music. So it may be useful to provide a quick reminder of the careers of the above so as to measure their personal contributions, in light of the fact that mechanical recording-systems in the 1920’s favoured brass- and wind-instrument sound-takes to the detriment of percussion and plucked-string instruments; this, however, righted itself to the advantage of guitars, the bandolim and the cavaquinho in the Thirties. The sound, which gradually improved as technology progressed, is sufficiently clear and present for us to take the temperature of the period with pleasure, and be enchanted by Pixinguinha’s flute solos in those years.

Short biographies of some early performers

Some virtuosos marked their era, but the pivotal figure in the first half of the 20th century was Pixinguinha, whose unforgettable melodies and stunning flute solos instilled a form of delicate classicism.

Pattápio Silva (1880-1907)

This musician born into a modest family in Rio began as a barber. He was such a virtuoso flautist that he succeeded Joaquim Callado at the Instituto Nacional de Musica, and also appeared before the President of the Republic after conquering the hearts of the public. His recordings for Casa Edison reveal fluid playing that served themes that swung between classical and popular music. But what would he have become if diphtheria hadn’t carried him away in only five days at age twenty-six?

Américo Jacomino “Canhoto” (1889-1928)

This son of Italian immigrants, born in Sao Paulo, was a self-taught left-handed guitarist who didn’t reverse the strings of his instrument. He was nicknamed “canhoto” (meaning “the left-hander”), and his performances whether solo or in quartet were unbelievably modern; to be convinced, one only has to listen to his recording of Abismo de Rosas. Incidentally he was also the first to record totally solo, and his playing was filled with vibrato. The waltz Abismo de Rosas (the title initially chosen was Acordes de Violão), made popular by the Dilermando Reis version you can discover elsewhere in this anthology, has become a standard in the repertoire of guitarists the world over.

João Pernambuco (1883-1947)

After acquiring his knowledge in the company of “violeiros” and “cantadores” in the Sertão region of the Nordeste, he lived for a time in Recife before landing in Rio in 1904. He was the composer of Luar do Sertão, the waltz Sonho de Magia and the choro Magoado as well as Cabocla do Caxanga, which would be the great hit of the 1914 Carnival. Pernambuco was self-taught and a humble, proud man who unfortunately never succeeded in attracting attention from record-companies, even though his music (which borrows from several genres and not just the choro) has a density guaranteed to tear the soul. He was a guitarist and composer of major importance, but he was forgotten in his final decades despite being a close friend of Villa-Lobos, who consistently supported him.

Benedito Lacerda (1903-1958)

Another son of Italian immigrants, Lacerda was a thrilling flautist as well as a good composer of waltzes and sambas that left their mark on people in their day. His role was also essential in the sound-geometry of what came to be called a “regional”, i.e. an ensemble featuring flute, saxophone, 6-string guitar, 7-string guitar, cavaquinho and pandeiro. He was accompanied by exceptional musicians and played a crucial role in reviving the career of Pixinguinha when, between 1946 and 1950, he recorded 34 sumptuous titles penned by the Master, who by then was abandoning himself to playing innovative descants on a tenor saxophone.

Pixinguinha (1898-1973)

If there could be only one virtuoso in the music of Brazil it would have to be Pixinguinha; and if there is one composer whose talent takes precedence over an Antonio Carlos Jobim, then that would be Pixinguinha also… And both men — who appreciated each other, incidentally — had reputations of being “goodness” personified. The man whose grandmother liked to call him “Pizindim” — the word comes from African dialect and means a “kind and good-tempered child” — was born Alfredo da Rocha Viana Junior, and he was one of fourteen children. His father, an enlightened amateur flautist, collected music scores; he was surrounded by musicians (of all races) versed in the choro genre. So it’s not surprising that at the age of fifteen, Pixinguinha embraced a professional music career (the case was not rare at the time). He would be “tutored” by his brother China and also by Irineu de Almeida, who was known as “Batina” (the Portuguese word for “cassock”) because he wouldn’t wear anything else. Pixinguinha rapidly became a member of Os Batutas, a group of varying size that played an essential role in choro’s development. It was a very favourable environment and his talents as a flautist and composer bloomed, reaching their apogee in the Thirties. Compositions that remain from that period include Rosa, 1X0 and Sofre Porque Queres, as well as solo flute recordings that display perfect architecture. While he bathed in an African matrix as a child and in adolescence, and loved to return to those origins for renewed inspiration — (remember that slavery didn’t end in Brazil until 1888, and that the mothers of his friends Donga and Heitor dos Prazeres were both candomble priestesses from Bahia…) — Pixinguinha, quite unconsciously, became the man who established the choro’s codes of classicism, the same codes that would be claimed by Jacob do Bandolim. The last fires in Pixinguinha blazed when he played with Benedito Lacerda’s “regional” (improvising wonderful counterpoint on his tenor saxophone) and with the “A Velha Guarda” ensemble led by Almirante. In addition to his virtuoso talents as flautist and composer, he was also much sought-after as an arranger, and worked with all the singers then in fashion.

Luperce Miranda (1904-1977)

This Nordeste musician went down in music history as the first solo bandolim player to be recorded. A virtuoso, he played in a characteristic Neapolitan style filled with ornamentation.

Radamés Gnattali (1906 -1988)

Gnattali is an imperative mention in the flux of soloists and virtuosos from 1930 to 1960 even if he remained active up until the 1980s (and continued to have an impact on the young generation). His parents were also Italian immigrants, but he was born in Porto Alegre, in the south of Brazil bordering Argentina and Uruguay. A classical concert-pianist, he went to live in Rio at the end of the Twenties and was so fascinated by Ernesto Nazareth — he heard him playing at the Odeon cinema — that he would stray into music that was essentially popular, rather than classical. He turned to arranging and was as much in demand as Pixinguinha (the seminal version of Aquarela do Brasil is Gnattali’s work), yet found time to become a prolific composer of classical pieces, writing the Concerto N° 1 for Guitar and Orchestra which Laurindo Almeida presented, Suite Retratos (which he offered to Jacob do Bandolim), Cantata Maria – Jesus dos Anjos etc.), and also popular works such as Valsa Triste and Amargura for example. In this anthology you can discover the versions by the saxophonist Paulo Moura, then aged 28, who was making his first record under his own name with eight compositions by Radamés. With the drummer Luciano Perrone and clarinettist Luiz Americano, Radamés formed the Trio Carioca based on the Benny Goodman trio (the theme Cabuloso is still in the nation’s repertoire) and then his Quintet with, among others, Chiquinho do Acordeon and José Menezes.

Notes on the virtuosos in this anthology

The Fifties and early Sixties constituted a turning point which saw the last sparks of some virtuosos — Luiz Americano, Dilermando Reis, even Abel Ferreira — mingling with the innovations of young newcomers. The record by Paulo Moura is interesting in this respect by the way, for it associates the “old lion” generation of Radamés Gnattali (the pianist on the sessions, who also wrote all the titles), Trinca (drums) and Vidal (double bass), with the up and coming generation represented by Moura (barely 28) and Baden (who was only 21). These short portraits begin with the musicians who were most representative of a generation which was slowly dying out.

Luiz Americano (1900 -1960)

This clarinettist and saxophonist from the Nordeste also left a few compositions that are far from being negligible, and his highly expressive playing would sometimes push him to the edge… almost to circus music. He was a member of the Trio Carioca founded by Radamés Gnattali, and also the Velha Guarda carried by Donga and Pixinguinha. He recorded Tocando pra vôcé in 1940 in the sessions that took place on the steamer Uruguai (organized for Columbia by conductor Leopold Stokowski, who was recommended by Villa Lobos.)

Severino Araujo (1917-2012)

A clarinettist from the Nordeste, Araujo founded the Orquestra Tabajara, basing it on the American big-band model, and it became a glorious staple in the “gafieiras” (dance halls) for more than five decades. He left two magnificent compositions, unarguably standards today: Um Chorinho em aldeia and Espinha de Bacalhau.

José Menezes (1921-2013)

Like all musicians from the Nordeste, Menezes came to Rio de Janeiro in search of a real dimension for his career. He copied his peers, playing on the popular shows of the principal radio stations, and even appeared as a duo for a time, with Garoto, another talented multi-instrumentalist (Menezes played acoustic and electric guitars as well as he played the bandolim and cavaquinho.) He was a vital member of the Quinteto led by Radames Gnattali, and some of his compositions (Nova Ilusão, Comigo é assim) became hits that have remained popular to this day.

Dilermando Reis (1916-1977)

Reis was taught by the blind guitarist Levino da Conceição, and handed on his knowledge to Bola Sete and even President Juscelino Kubitschek. He was linked with Radio Nacional for almost twenty years and recorded countless LPs for Continental, including the famous Abismo de Rosas (four excerpts of which appear here). He also left compositions like Magoado or Noite de Lua as well as some beautiful performances of themes from the world of classical music.

Luis Bonfá (1922-2001)

Bonfá owes his fame to his two compositions featured in the film Orfeu Negro: Manhã de Carnaval and Samba de Orfeu are so famous that as a result he was catalogued as one of the creators of Bossa Nova — which he wasn’t at all (if only because he was from a much earlier generation). He played guitar on the soundtrack of Orfeu Negro (1958) due to the fact that he’d been the guitarist in the play Orfeu da Conceição (written two years previously by Antonio Carlos Jobim and Vinicius de Moraes); another result was that despite director Marcel Camus’ reservations, both titles mentioned above remained in the film. He was an American resident and recorded there for years, but his artistic output was often less than satisfying.

Abel Ferreira (1915-1980)

Born in the State of Minas Gerais, Ferreira recorded Chorando Baixinho for Columbia in 1942, and it became his signature and lucky-mascot theme. A clarinettist and saxophonist (he played alto and tenor), he was a favourite with all the popular song-stars; a worthy heir to Luiz Americano, he gradually went into retirement in the course of the Seventies, but he remains one of the worthiest representatives of the choro.

Waldir Azevedo (1923-1980)

As a soloist, Azevedo was responsible for making the cavaquinho a noble instrument, which is not a heresy but a rarity. He served his apprenticeship alongside Dilermando Reis before he set up his own group in 1947. He created lively compositions that enjoyed phenomenal both in Brazil and abroad during the Fifties, and made more than fifty 78rpm records in addition to some twenty LPs. Brasileirinho and Delicado were just two of his greatest hits, and everyone must have heard them by now (even Dr John recorded Delicado as a piano solo!)

Laurindo Almeida (1917-1995)

He was born in São Paulo but went to live in Los Angeles as early as the Forties. A classically trained guitarist and concert performer, he also contributed to popular music, playing in “cassinos” and on radio as well as on sessions recorded by Columbia on the “Uruguai” steamer in 1940. While appearing on a tour playing classical concerts in the USA, he was invited to join the orchestra of Stan Kenton, and went on to record several LPs with Bud Shank, the Modern Jazz Quartet and also Stan Getz. He also became a recognized film-composer, working also in television on series such as The Fugitive.

Jacob do Bandolim (1918-1969)

As if there was a symbiosis between him and his instrument, Jacob Pick Bittencourt finally became “Jacob do Bandolim”. He was obsessed with perfection, imposing rehearsal after rehearsal on his musicians, and he was renowned for his intransigence and caustic temperament. He revered only one person, Pixinguinha, admittedly a delicious man and musical giant… Born in the popular Lapa quarter, this son of a little Brazilian chemist (his mother was from Poland) always considered himself an amateur: “I’ve never lived a minute just from music,” he used to say (and he actually worked as a scribe in the Justice Department). According to Jacob, the choro had to be an improvisation, which in his opinion implied that the instrumentalist had to learn a piece by heart if he was to develop it.

When Jacob swept onto the scene in 1947, together with his freshness, spontaneity and innate sense of melodic simplicity, obviously Luperce Miranda suddenly started to show signs of wear… Because Jacob transfigured the way in which his chosen instrument — born with an ungrateful sound — was played. His rhythmical precision was stunning, and his sound was more Portuguese than Neapolitan (he’d accompanied a Portuguese singer in fado during the 1930’s). Pedro Amorim, also a bandolim player but born in the Sixties, wrote: “He was the reference, the school, the undeniable stylist.” Jacob died from a second heart attack on August 13th 1969, in front of his own house, on his return from a visit to see Pixinguinha; he and his old friend had been choosing material for a record they were preparing of the latter’s works.

Paulo Moura (1932-2010)

Paulo Moura is one of the rare Brazilian “horns” to have acquired a certain celebrity abroad. He was born in Sao Paulo and his father was a clarinettist and conductor; Paulo himself joined the Municipal Theatre Symphony Orchestra in Rio when he was 27. In the same period (early 60’s) he joined the sextet led by pianist Sergio Mendes, and regularly rubbed shoulders with the likes of Cannonball Adderley and Herbie Mann, even taking part in the famous “Bossa Nova” concert at Carnegie Hall in 1962. After a first album as a leader (1959) that featured songs by Radames Gnattali, he went on to launch some fine productions in the Sixties and Seventies — Paulo Moura Hepteto, Paulo Moura Quarteto, Fibra — and conducted the orchestra accompanying Milton Nascimento for the concerts Milagre dos Peixes – Ao Vivo. He composed an opus celebrating the centenary of the abolition of slavery and conducted it in 1988 with the Brasilia Symphony Orchestra. In 1989, with Confusão urbana, sububarna e rural, he published one of his best albums, and then returned more explicitly to the choro with Mistura e Manda. He would also make duo records with Rafael Rabello (Dois Irmãos, 1992) and Yamandu Costa (El Negro del Blanco.) Paulo Moura — a man with a magnetic personality (although not without a certain narcissism) — was undeniably one of the greatest clarinets Brazil ever produced.

Baden Powell (1937-2000)

Roberto Baden Powell de Aquino was known simply as Baden Powell in tribute to the founder of the Scout Movement, following the Brazilian custom of nicknaming their children after historical figures). He remains a major figure in Brazilian music of all time, and was one of the essential guitarists in popular music, playing with such musicians as Django Reinhardt, Joe Pass, Jim Hall, Paco de Lucia, or John McLaughlin.

On Deve Ser Amor, recorded in Rio by American jazz flautist Herbie Mann in 1960, Baden Powell’s personality burst into broad daylight when he was twenty-three: he used his thumb in a way that gave the music a staggering rhythmical imprint, and the chords really sang. João Gilberto had already turned the soundscape upside down, and now Baden Powell added a new leap in quality to Brazilian guitar. He quickly established his virtuosity as a guitarist and composer, and even though he was physically of small build, his personality shone when he was onstage (audiences would always love to hear him play Samba da benção). Born into a family where he was surrounded by choros and sambas, when he was eight he took guitar lessons from Jayme Florence “Meira”, who played with Benedito Lacerda and his “regional” (I was privileged to be present at private occasions where I could see the almost “father & son” respect which tied the pupil and his master). Baden turned professional at sixteen, composing Samba Triste (with lyrics by Billy Blanco) in 1956; the song was first made known by Lucio Alves, one of the period’s major voices. In the most fertile part of Powell’s career, only two lyricists — no doubt two of the greatest — would set their texts to his music: Vinicius de Moraes, (Os Afro-Sambas, Berimbau, Samba em preludio, Consolação…) and Paulo César Pinheiro (Lapinha, É de Lei, Refem da solidão). Baden spent most of the Seventies in Germany and in France where he did a long and memorable tour (notably appearing with Claude Nougaro at the Olympia). His health became fragile and in his later years he gave fewer concerts; he did however publish Rio das Valsas in 1994, a very nice record which in a way marked a return to the choro and the world of his childhood. A Brazilian to his fingertips, he couldn’t be categorized as belonging to bossa, nor as a pure sambista, nor even as an eminent choro guitarist, even if he was a little bit of each at the same time, i.e. a bit Black, a bit “Europeanized-White”, modern and yet rooted in tradition. Above all, he was a creator, the bearer of a personal universe to which audiences would remain loyal until the end. After his passing, the city of Rio de Janeiro gave his name to a venue in Copacabana.

Notes on the music in this anthology

They never appeared in the “People” pages or became media-personalities, but virtuoso soloists were the artisans of the musical identity of Brazil, and the instrumentalists of the Fifties and Sixties largely contributed to construct its edifice. This anthology examines instrumental virtuosity and improvisation from a perspective that is different from the jazz understanding, and it is from this oblique angle that we present performances by harmonica-player Edú da Gaita (Edú Kruni) and Chiquinho do Acordeon, two exceptional musicians whose presence additionally illustrates some rather little known facets of the music styles of the Nordeste. A good deal of space is left to guitarists who, more than virtuosos, were fully-fledged soloists in the sense that they often expressed themselves unaccompanied. Yet it may be useful to remind listeners that for a long time in Brazil, the guitar was perceived not as a noble instrument at all, but as an asocial symbol like a vagabond. There was a time when being Black was as dangerous as taking a walk with a guitar slung over one’s shoulder or encountering police. It is quite worth noting that Heitor Villa-Lobos loved this instrument so much that he composed Études and Choros especially for it; it underlined his affection for popular music-forms, too (he often went up to meet composer Cartola on the Morro da Mangueira, and every Sunday at his own home he played host to João Pernambuco, who had been quite forgotten by then). Laurindo Almeida’s versions of the compositions of Villa Lobos are thrilling precisely because they have none of the rigidity of the versions by guitarists from the classical world, but they preserve every quality of the “clean sound” inherent in classical playing, which is something that popular guitarists are not always capable of showing. Dilermando Reis was also a musician spanning performances of classical works and popular songs, both of which he made noble by his peerless virtuosity. As for Baden Powell, as already emphasized elsewhere, he projected the manner in which the strings were played in another synthesis that marked the end of his century, like Jacob had done with his bandolim. The latter, however much he referred to the classicism of Pixinguinha and the “regional” of Benedito Lacerda, still opened up many new horizons. And in the course of their three “caravans” in Europe in around 1960, (as those tours were called then), Radamés and his Sexteto provided a clear panorama of period Brazilian music. In passing, you can note the modernity of Radamés in his playing, not only in his solo phases but also as an accompanist, and the versatility of José Menezes, who moved from the electric guitar to the cavaquinho with equal facility. In Europe, at least, Radamés and his Sexteto were decidedly a beautiful, if sadly under-exposed, institution.

Adapted by Martin Davies

from the French Text

by Teca Calazans and Philippe LESAGE

© 2016 Frémeaux & Associés

Discographie - CD1

1. MIGALHAS DE AMOR (Jacob do Bandolim) 3’08

Jacob do Bandolim, Guitare tenor com Regional do Canhoto. RCA Victor 80.0969, 1952

2. FORRÓ DE GALA (Jacob do Bandolim) 2’29

Jacob do Bandolim com Regional do Canhoto. RCA Victor -80.0987, 1952

3. BRASILEIRINHO (Waldir Azevedo) 2’33

Waldir Azevedo e seu Conjunto Regional. Continental, 16.050 B, 1949

4. PEDACINHO DO CÉU (Waldir Azevedo) 3’21

Waldir Azevedo e seu Conjunto Regional. Continental, 16.369 B, 1951

5. DO JEITO QUE A GENTE QUER (Ed Lincoln) 2’36

Baden Powell. Philips, P 630.445 L, 1961

6. INSONIA (Baden Powell) 2’55

Baden Powell. Philips, P 630.445 L, 1961

7. LUAR DE AGOSTO (Baden Powell / Nilo Queiroz) 3’15

Baden Powell. Philips, P 630.445 L, 1961

8. VALSA TRISTE (Radamés Gnattali) 4’47

Paulo Moura Interpreta Radamés Gnattali. Continental, LPP 3078, 1959

9. PENUMBRA (Radamés Gnattali) 5’55

Paulo Moura Interpreta Radamés Gnattali. Continental, LPP 3078, 1959

10. CARIOCA (Radamés Gnattali) 3’35

Paulo Moura Interpreta Radamés Gnattali. Continental, LPP 3078, 1959

11. ESPINHA DE BACALHAU (Severino Araújo) 3’17

Severino Araújo e Orquestra Tabajara. Continental, 17703, 1959

12. DOCE MELODIA (Abel Ferreira) 2’09

Abel Ferreira e seu Conjunto. EMI ODEON 034-422524, 1962

13. DOCE MENTIRA (Abel Ferreira) 2’32

Abel Ferreira e seu Conjunto. EMI ODEON, 034-422524, 1962

14. TERNURA (Lyrio Panicali / Amaral Gurgel) 2’23

Abel Ferreira e seu Conjunto. EMI ODEON, 034-422524, 1962

15. ACARICIANDO (Abel Ferreira / Lourival Faissal) 2’59

Abel Ferreira e seu Conjunto. EMI ODEON, 034-422524, 1962

16. ALVORADA (Jacob Bittencourt) 3’08

Radamés na Europa com seu Sexteto e Edú. ODEON MOFB, 3.172, 1960

17. NA CADÊNCIA DO BAIÃO : Pot-pourri A) NÃO INTERESSA NÃO (Luiz Bittencourt / José Menezes) B) BAIÃO DA GARÔA (Luiz Gonzaga / Hervê Cordovil) Radamés na Europa com seu Sexteto e Edú. ODEON MOFB, 3.172, 1960 2’46

18. O APITO NO SAMBA (Luiz Bandeira / Luiz Antonio) 2’58

Radamés na Europa com seu Sexteto e Edú. ODEON MOFB, 3.172, 1960

19 - UM CHORINHO EM SERESTA (Paulo Patricio) 2’54

Luiz Americano e seu Conjunto. RCA Victor, BBL-1049, 1960

20. VÊ SE GOSTAS (Waldir Azevedo / Otaviano Pitanga) 3’26

Waldir Azevedo e seu Conjunto Regional. Continental, 16.314 - B, 1950

21. DOCE DE COCO (Jacob do Bandolim) 2’58

Jacob do Bandolim e Regional do Canhoto. RCA Victor, 80.0745, 1951

Discographie - CD2

1. CHORANDO BAIXINHO (Abel Ferreira) 2’40

Abel Ferreira e seu Conjunto. EMI ODEON, 034-422524, 1962

2. SAXOFONE PORQUE CHORAS (Ratinho) 3’23

Abel Ferreira e seu Conjunto. EMI ODEON, 034-422524, 1962

3. É DO QUE HÁ (Luiz Americano) 3’01

Abel Ferreira e seu Conjunto. EMI ODEON, 034-422524, 1962

4. MONOTONIA (Radamés Gnattali) 3’59

Paulo Moura Interpreta Radamés Gnattali. Continental, LPP 3078, 1959

5. ROMANCE (Radamés Gnattali) 4’14

Paulo Moura Interpreta Radamés Gnattali. Continental, LPP 3078, 1959

6. CARIOQUINHA (Waldir Azevedo) 2’55

Waldir Azevedo e seu Conjunto Regional. Continental, 16.050 A, 1949

7. DE PAPO PRO AR (Joubert de Carvalho / Olegário Mariano) 2’16

José Menezes e seu Conjunto. SINTER 053B, Matriz S-108, 1950

8. GRAUNA (João Pernambuco) 2’52

Jacob do Bandolim c/ César Faria e seu Conjunto. RCA Victor, 80.0702, 1950

9. ODEON (Ernesto Nazareth) 2’31

Jacob do Bandolim - RCA Victor, 80.0900, 1952

10. PRIMEIRO AMOR (Hernani Silva) 2’07

Radamés na Europa com seu Sexteto e Edú. ODEON MOFB, 3.172, 1960

11. BATUQUE (Edú) 3’11

Radamés na Europa com seu Sexteto e Edú. ODEON MOFB, 3.172, 1960

12. FOI A NOITE

(Antonio Carlos Jobim / Newton Mendonça) 2’38

Radamés na Europa com seu Sexteto e Edú. ODEON MOFB, 3.172, 1960

13. MINHA PALHOÇA (Jota Cascata) 2’03

Baden Powell. Philips, P 630.445 L, 1961

14. PRELUDIO AO CORAÇÃO (Baden Powell) 1’14

Baden Powell. Philips, P 630.445 L, 1961

15. LUZ NEGRA

(Nelson Cavaquinho / Irani Barros) 2’33

Baden Powell. Philips, P 630.445 L, 1961

16. IMPROVISO BOSSA NOVA (Baden Powell) 2’06

Baden Powell. Philips, P 630.445 L, 1961

17. LUZES DO RIO (Luiz Bonfá) 2’28

Luiz Bonfá. Cook, 1134, 1959

18. MAFUÁ (Armandinho) 2’24

José Menezes. Sinter, SLP 1103, 1957

19. ABISMO DE ROSAS

(Américo Jacomino « Canhoto ») 3’58

Dilermano Reis. Continental, 1-01-405-005B, 1961

20. MELANCOLIA (Henriqueta Ribeiro) 3’18

Luiz Americano e seu Conjunto. RCA Victor, I BBL-1049, 1960

21. DINORÁ

(Benedito Lacerda / José Ferreira Ramos) 2’18

Com Altamiro Carrilho e seu Regional. Copacabana, LP 11008, 1959

Discographie - CD3

1. CHORO TYPICO (Heitor Villa Lobos) 5’47

Laurindo Almeida. Capitol Records, SP 8497, 1959

2. PRELUDE N° 5 (Heitor Villa Lobos) 3’33

Laurindo Almeida. Capitol Records, SP 8497, 1959

3. SCHOTTISCH CHORO (Heitor Villa Lobos) 4’38

Laurindo Almeida. Capitol Records, SP 8497, 1959

4. SONS DE CARRILHÕES (João Pernambuco) 2’48

Dilermando Reis. Continental, 1-01-405-005-A, 1961

5. NOITE DE LUA (Dilermando Reis) 3’14

Dilermando Reis. Continental, 1-01-405-005-A, 1961

6. MAGOADO (Dilermando Reis) 2’42

Dilermando Reis. Continental, 1-01-405-005-A, 1961

7. DESPERTAR DA MONTANHA (Eduardo Souto) 2’57

Jacob do Bandolim c/ César Faria, guitare, Fernando Ribeiro, guitare 7 cordes. RCA Victor, 80.0602, 1949

8. ATLÂNTICO (Ernesto Nazareth) 2’59

Jacob do Bandolim com Regional do Canhoto. RCA Victor, BP1 80. 0901, 1952

9. SIMPLICIDADE (Jacob do Bandolim) 2’45

Jacob do Bandolim com Regional, do Canhoto. RCA Victor, 80.0680, 1950

10. DEVANEIO (Radamés Gnattali) 4’37

Paulo Moura interpreta Radamés Gnattali. Continental, LPP 3078, 1959

11. NOSTALGIA (Radamés Gnattali) 3’58

Paulo Moura Interpreta Radamés Gnattali. Continental, LPP 3078, 1959

12. SEMPRE A SONHAR (Radamés Gnattali) 3’43

Paulo Moura Interpreta Radamés Gnattali. Continental, LPP 3078, 1959

13. SEDUTOR (Oswaldo Lyra / Carlito) 2’05

Abel Ferreira e seu Conjunto. EMI ODEON, 034-422524, 1962

14. FLUIDO DA SAUDADE (Baden Powell) 4’00

Baden Powell. Philips, P 630.445 L, 1961

15. DUM… DUM… DUM…

(Baden Powell / Luiz Bittencourt) 1’19

Baden Powell. Philips, P 630.445 L, 1961

16. ENCABULADO

(José Menezes / Luiz Bittencourt) 2’35

José Menezes e seu Quarteto. Sinter, SLP 1094, 1957

17. DELICADO (Waldir Azevedo) 2’33

Waldir Azevedo e seu Conjunto Regional. Continental, 16.314-A, 1950

18. CAPRICHO NORTISTA, POT POURRI : BAIÃO, ASA BRANCA, NO MEU PÉ DE SERRA, MANGARATIBA, JUAZEIRO, SIRIDÓ, (Humberto Teixeira / Luiz Gonzaga) Radamés na Europa com seu Sexteto e Edú. ODEON MOFB, 3.172, 1960 4’49

19. ANTIGAMENTE ERA ASSIM

(Luiz Americano / Rogerio Lucas) 3’07

Luiz Americano e seu Conjunto. RCA Victor, BBL-1049, 1960

20. LUIZ AMERICANO EM BRASILIA

(Luiz Americano / Rogerio Lucas) 2’24

Luiz Americano e seu Conjunto. RCA Victor, BBL-1049, 1960

21. DE PASSAGEM PELA ARABIA (Luiz Americano) 3’25

Luiz Americano e seu Conjunto. RCA Victor, BBL-1049, 1960

Du début des années cinquante jusque dans les années soixante, la musique instrumentale brésilienne vit une époque charnière où s’entremêlent les derniers feux de certains virtuoses aux innovations de musiciens qui séduiront le monde entier comme Jacob do Bandolim, Baden Powell ou Paulo Moura. Ici, d’une certaine manière, l’instrument soliste se substitue au chanteur pour se lancer dans le développement du thème en une improvisation très différente de ce qui est la règle dans le jazz.

Teca Calazans et Philippe Lesage

In Brazil, instrumental music went through many changes from the early Fifties to the Sixties, a vital period in which the last flashes of certain virtuosos mingled with innovations from musicians who went on to seduce the whole world, among them Jacob do Bandolim, Baden Powell or Paulo Moura. Here, in a certain fashion, the singers launching the theme’s development were replaced by solo instruments, with improvisations that took place in a very different manner from the rules of jazz.

Teca Calazans et Philippe Lesage

CD1

1. MIGALHAS DE AMOR (Jacob do Bandolim) 3’08

2. FORRÓ DE GALA (Jacob do Bandolim) 2’29

3. BRASILEIRINHO (Waldir Azevedo) 2’33

4. PEDACINHO DO CÉU (Waldir Azevedo) 3’21

5. DO JEITO QUE A GENTE QUER (Baden Powell) 2’36

6. INSONIA (Baden Powell) 2’55

7. LUAR DE AGOSTO (Baden Powell) 3’15

8. VALSA TRISTE (Paulo Moura) 4’47

9. PENUMBRA (Paulo Moura) 5’55

10. CARIOCA (Paulo Moura) 3’35

11. ESPINHA DE BACALHAU (Severino Araújo e Orquestra Tabajara) 3’17

12. DOCE MELODIA (Abel Ferreira) 2’09

13. DOCE MENTIRA (Abel Ferreira) 2’32

14. TERNURA (Abel Ferreira) 2’23

15. ACARICIANDO (Abel Ferreira) 2’59

16. ALVORADA (Radamés c/ seu Sexteto) 3’08

17. NA CADÊNCIA DO BAIÃO (Pot-pourri) (Radamés com seu Sexteto) 2’46

18. O APITO NO SAMBA (Radamés com seu Sexteto) 2’58

19. UM CHORINHO EM SERESTA (Luiz Americano) 2’54

20. VÊ SE GOSTAS (Waldir Azevedo) 3’26

21. DOCE DE COCO (Jacob do Bandolim) 2’58

CD2

1. CHORANDO BAIXINHO (Abel Ferreira) 2’40

2. SAXOFONE PORQUE CHORAS (Abel Ferreira) 3’23

3. É DO QUE HÁ (Abel Ferreira) 3’01

4. MONOTONIA (Paulo Moura) 3’59

5. ROMANCE (Paulo Moura) 4’14

6. CARIOQUINHA (Waldir Azevedo) 2’55

7. DE PAPO PRO AR (José Menezes) 2’16

8. GRAUNA (Jacob do Bandolim) 2’52

9. ODEON (Jacob do Bandolim) 2’31

10. PRIMEIRO AMOR (Radamés com seu Sexteto) 2’07

11. BATUQUE (Radamés com seu Sexteto e Edú) 3’11

12. FOI A NOITE (Radamés Gnattali) 2’38

13. MINHA PALHOÇA (Baden Powell) 2’03

14. PRELUDIO AO CORAÇÃO (Baden Powell) 1’14

15. LUZ NEGRA (Baden Powell) 2’33

16. IMPROVISO BOSSA NOVA (Baden Powell) 2’06

17. LUZES DO RIO (Luiz Bonfá) 2’28

18. MAFUÁ (José Menezes) 2’24

19. ABISMO DE ROSAS (Dilermando Reis) 3’58

20. MELANCOLIA (Luiz Americano) 3’18

21. DINORÁ (Altamiro Carrilho) 2’18

CD3

1. CHORO TYPICO (Laurindo Almeida) 5’47

2. PRELUDE N° 5 (Laurindo Almeida) 3’33

3. SCHOTTISCH CHORO (Laurindo Almeida) 4’38

4. SONS DE CARRILHÕES (Dilermando Reis) 2’48

5. NOITE DE LUA (Dilermando Reis) 3’14

6. MAGOADO (Dilermando Reis) 2’42

7. DESPERTAR DA MONTANHA (Jacob do Bandolim) 2’57

8. ATLÂNTICO (Jacob do Bandolim) 2’59

9. SIMPLICIDADE (Jacob do Bandolim) 2’45

10. DEVANEIO (Paulo Moura) 4’37

11. NOSTALGIA (Paulo Moura) 3’58

12. SEMPRE A SONHAR (Paulo Moura) 3’43

13. SEDUTOR (Abel Ferreira) 2’05

14. FLUIDO DA SAUDADE (Baden Powell) 4’00

15. DUM… DUM… DUM… (Baden Powell) 1’19

16. ENCABULADO (José Menezes) 2’35

17. DELICADO (Waldir Azevedo) 2’33

18. CAPRICHO NORTISTA (Pot Pourri)(Radamés com seu Sexteto) 4’49

19. ANTIGAMENTE ERA ASSIM (Luiz Americano) 3’07

20. LUIZ AMERICANO EM BRASILIA (Luiz Americano) 2’24

21. DE PASSAGEM PELA ARABIA (Luiz Americano) 3’25