- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

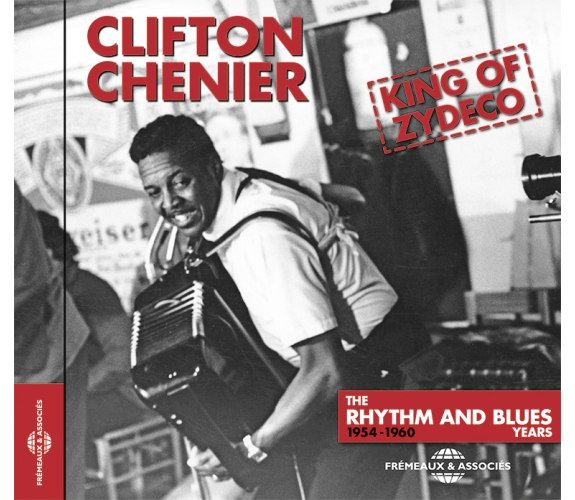

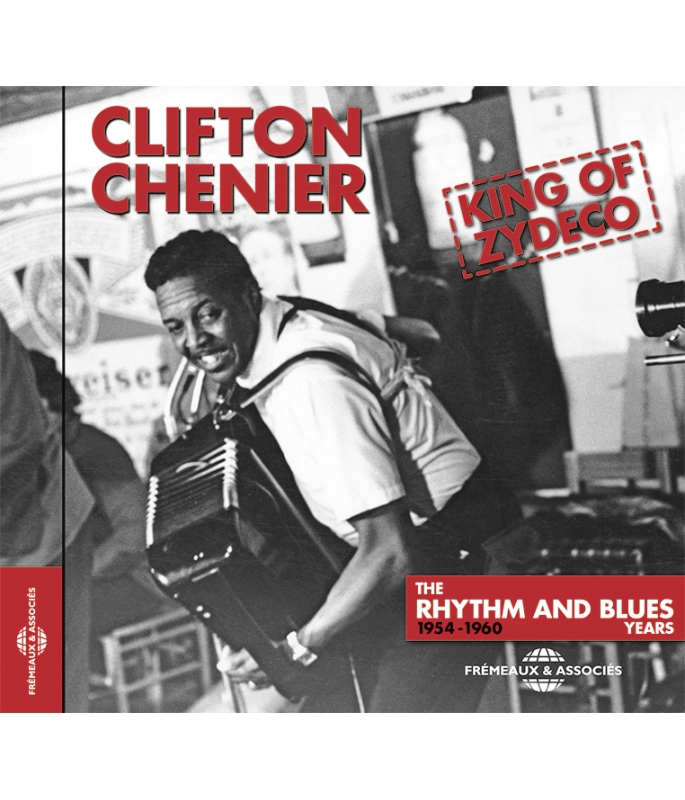

THE RHYTHM AND BLUES YEARS 1954-1960

CLIFTON CHENIER

Ref.: FA5715

Artistic Direction : JEAN BUZELIN

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Total duration of the pack : 1 hours 1 minutes

Nbre. CD : 2

THE RHYTHM AND BLUES YEARS 1954-1960

THE RHYTHM AND BLUES YEARS 1954-1960

A marvellous black American singer and accordionist, Clifton Chenier succeeded in forging a style all his own, Zydeco, and for a long time he was considered its sole representative. Born in the 30s, the music came from mixed Creole and Cajun cultures in French-speaking Louisiana; when Chenier took hold of the genre it was marginal and mocked by mainstream America, but in just a few years, with a series of hit albums, the man they called the “King of Zydeco” turned the music into an accomplished form of expression that everyone appreciated. This anthology from Jean Buzelin follows the history of this King’s coronation between 1954 and 1960. After the titles already featured in the album “Zydeco,1929-1972” (FA5616), Frémeaux & Associés is proud to highlight the work and genius of this legendary artist. Patrick FRÉMEAUX

LOUISIANE 1928-1939

BLACK CREOLE, FRENCH MUSIC & BLUES 1929-1972

UN FILM DE JEAN-PIERRE BRUNEAU - DVD + CD

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Louisiana StompClifton ChenierChenier Clifton00:02:501954

-

2Clifton's BluesClifton ChenierChenier Clifton00:03:111954

-

3Tell MeClifton ChenierChenier Clifton00:02:161954

-

4Country BredClifton ChenierFullbright J R00:02:351954

-

5Rockin' HopClifton ChenierChenier Clifton00:02:041954

-

6Eh ! Petite filleClifton ChenierChenier Clifton00:02:421955

-

7Boppin' The RockClifton ChenierChenier Clifton00:02:221955

-

8Think It OverClifton ChenierBuyem W E00:02:281955

-

9The Things I Did For YouClifton ChenierChenier Clifton00:02:511955

-

10All Night LongClifton ChenierChenier Clifton00:02:181955

-

11YesterdayClifton ChenierChenier Clifton00:02:511955

-

12Squeeze-Box BoogieClifton ChenierChenier Clifton00:01:581955

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1The Cat's Dreamin'Clifton ChenierChenier Clifton00:02:101955

-

2Baby PleaseClifton ChenierChenier Clifton00:02:281956

-

3Where Can My Baby BeClifton ChenierChenier Clifton00:02:401956

-

4The Big WheelClifton ChenierChenier Clifton00:02:501956

-

5My SoulClifton ChenierJames E.00:02:531957

-

6Bayou DriveClifton ChenierChenier Clifton00:02:551957

-

7It Happened So FastClifton ChenierChenier Clifton00:02:241958

-

8Goodbye BabyClifton ChenierChenier Clifton00:03:131958

-

9Hey Ma MaClifton ChenierChenier Clifton00:02:051959

-

10Worried Life BluesClifton ChenierMerriweather M.00:02:121959

-

11Night And Day My LoveClifton ChenierChenier Clifton00:02:441960

-

12Rockin' AccordianClifton ChenierChenier Clifton00:02:161960

Chenier FA5715

CLIFTONCHENIER

KING OF

ZYDECO

The Rhythm and Blues Years

1954-1960

CLIFTON CHENIER

KING OF ZYDECO

The Rhythm and Blues Years 1954-1960

Par Jean Buzelin

Un enfant noir des bayous

Né le 25 juin 1925 à Notelyville, au bord du Bayou Teche (près d’Opelousas, dans la paroisse de St.Landry), Clifton Chenier, d’origine noire et indienne, travaille très tôt à la petite ferme familiale avec son frère aîné Cleveland. Son père Joseph joue de l’accordéon dans les bals du samedi soir chez les voisins « les airs acadiens »1 et l’instrument intéresse beaucoup le jeune Clifton2. Mais sa vocation irréversible de musicien arrive le jour où plusieurs « gloires » locales de l’accordéon, Claude Faulk et les frères Jesse et Zo Zo Reynolds, s’arrêtent à la maison avant d’aller jouer dans le coin. Par ailleurs, d’autres champions amateurs de l’accordéon à boutons, comme son grand-oncle Peter King, son cousin Carlton King, Frank Andrus et Sidney Babineaux, habitent non loin de chez eux. Son père alors commence à le laisser jouer, « à 15 ans, moi tout seul, mon père m’a pas montré, mais moi j’écoutais »1, dans les petites fêtes campagnardes en compagnie de Cleveland, la planche à laver (rubboard) de leur mère sur ses genoux. « Ils donnaient des bals dans les maisons, raconte Cleveland, samedi au soir, dimanche après-midi, on mangeait, on commençait à danser ; tout le monde parlait français, tout mangeait ensemble là. »1Clifton abandonne le mélodéon single-notes en 1941 lorsqu’un certain Isaïe Blaza3, lors d’un bal à Opelousas, lui prête son accordéon-piano chromatique Hohner avant de lui en faire cadeau. Ce qui aura d’énormes conséquences dans l’évolution de sa musique. En 1942, alors qu’il travaillait comme ouvrier agricole à Loreauville, il rejoint son frère à Lake Charles où ils jouent avec leur jeune oncle, le guitariste et violoniste Morris “Big” Chenier4 dans les clubs et les dancings. Puis, après un crochet par New Iberia en 1945 dans les champs de canne à sucre, les deux frères abandonnent les travaux agricoles et émigrent à Port Arthur, à la frontière texane, où ils obtiennent des emplois mieux payés dans l’industrie pétrolière. « Quand j’étais en Acadie – ainsi nommait-on encore le pays cajun – précise Clifton, j’ai travaillé le corn, les patates… après j’ai travaillé à la raffinerie Gulf »1. Durant leur temps libre, ils se constituent un répertoire en prise avec l’actualité musicale (The Honeydripper de Joe Liggins, gros succès de l’époque) qu’ils présentent dans les clubs locaux comme le Blue Moon ou, les lundis et mardis, au Bon Ton Drive-In, un club tenu par Clarence Garlow5 à Beaumont, autre ville texane voisine située un peu au nord-ouest de Port Arthur. Tout en retournant le week-end à Basile ou à Lawtell, Clifton résidera avec son frère dans cette ville frontalière de 1947 à 1955. Entretemps, le chanteur-accordéoniste s’est marié avec Margaret Young.

Les grands débuts de Clifton Chenier

Désireux d’arriver à se faire un nom et une place dans le milieu musical, Clifton Chenier soigne sa présentation et ses prestations musicales, et il a formé un orchestre, le « Hot Sizzling Band » dans lequel figure un temps le guitariste Lee Baker, futur Lonnie Brooks. Et c’est à Port Arthur, en 1954, qu’iI est remarqué par J.R. Fullbright, le patron noir d’un petit label, Elko, lequel lui propose de faire un disque. Parmi les six morceaux6 gravés dans les studios de la radio KAOK à Lake Charles, Cliston Blues (sic), interprété en anglais par Cliston Chanier (re-sic sur l’étiquette) est revendu à Imperial, maison beaucoup plus importante qui l’exploite plus largement. Sans Cleveland, mais avec Big Chenier à la guitare et un batteur du nom de Robert Pete7, on peut considérer ce morceau comme le premier véritable blues de forme classique enregistré à l’accordéon. Sur ces entrefaites, Fullbright invite Clifton à venir habiter chez lui à Los Angeles ; la vie musicale sur la côte Ouest a une tout autre dimension, et le chanteur-accordéoniste se produit dans les clubs et dancings, comme le 5-4 Ballroom. Mais il rencontre toutefois des difficultés : « À Los Angeles, ça a pas trop mal marché, mais Oakland ou Frisco n’ont pas accroché. À Los Angeles, il y a toute une population que vient de Louisiane et qui connaissait cette musique. Ç’a été dur, je ne peux pas m’empêcher d’y penser. Parfois on se moquait même de moi : “Ah, il joue de ce vieil accordéon, ça vaut rien!” On allait voir les gens et on demandait à jouer une danse : “Écoutez, laissez-moi jouer ici ce soir. – Jouer quoi ? – De l’accordéon. – Non, on veut pas de ça ici. »8

Mais cela va changer l’année suivante, lorsque celui qui est rapidement surnommé le « King of the South » signe en avril 1955 avec un autre solide label indépendant, Specialty à Hollywood, et obtient immédiatement un hit régional avec Ay-Tete-Fee (Eh ‘tite fille), un french song d’une forme nouvelle qu’il interprète dans les deux langues. Clifton se révèle en effet comme un chanteur de blues/soul de grand talent, habité et persuasif, à la voix forte légèrement voilée. Parfaitement bilingue, il possède néanmoins un fort accent français, ce qui rend sa diction savoureuse et colorée. Et sa musique entrainante et roborative lui permet même d’obtenir un succès surprise sur le marché jamaïcain avec Squeeze-Box Boogie.

Après Clarence Garlow et Boozoo Chavis5, Clifton Chenier devient le troisième artiste zydeco à réaliser des disques. Mais, tandis que le premier joue essentiellement la carte blues/R&B et que le second, resté proche de la musique rurale, ne fait pas carrière, Chenier, à partir de ses racines, de ses goûts et de son vécu, va concocter un gumbo musical épicé et totalement original, une mixture de blues, de boogie-woogie, d’airs de danse à la mode et de pop songs, avec une pointe de country and western, sans oublier les ingrédients indispensables, les two-steps et les valses, le parfait mélange qui va définir le « genre zydeco » et l’orienter pour des décennies. Et il va occuper le terrain !

A partir de maintenant, l’histoire du zydeco se confond avec celle de Clifton Chenier. « J’ai commencé à jouer le zydeco, pas les danses cajun. J’ai joué les danses cajun mais j’ai apprendre le zydeco ; je continue avec le zydeco et le blues. Je connais les danses cajun mais bien plus le zydeco, c’est différent que la musique cajun comme c’est Jolie Blonde et les two-steps »1, encore que le terme n’avait pas encore d’existence “écrite”9. Pour longtemps, il sera considéré comme l’unique représentant d’un genre musical qui lui appartiendrait en plein. Ce qui n’est pas tout-à-fait faux car il n’a aucune concurrence sérieuse dans le domaine.

De retour en Louisiane, et devenu une petite star du R&B, c’est-à-dire uniquement auprès de la population noire, et précisément dans les Etats qui vont de la Louisiane à la Californie, le chanteur-accordéoniste tourne dans la région an compagnie du chanteur-guitariste Lowell Fulson, alors en pleine gloire, puis, pendant des mois d’affilée, au sein de package shows qui présentent au même programme plusieurs artistes, groupes et orchestre ; il a ainsi l’occasion de côtoyer de grandes vedettes comme Lloyd Price, Fats Domino, Chuck Berry, Jimmy Reed, Rosco Gordon, Johnny « Guitar » Watson, les Cadillacs, les Dells… Il acquiert ainsi beaucoup de métier et présente un show très professionnel à la tête d’un excellent orchestre de sept ou huit musiciens qui comprend notamment Philip Walker (de juin 53 à 57) et, plus brièvement, Lonesome Sundown, deux guitaristes de blues « Cajuns noirs » qui effectueront plus tard de belles carrières personnelles. Lorsqu’il n’est pas sur les routes du Midwest, de l’Indiana, de la côte Est, et jusqu’à New York où il apparaitra une fois sur la scène du fameux Apollo de Harlem, il truste les clubs de Houston, Dallas, Oklahoma City, Lafayette, etc. Et s’il possède un “chez lui” à Opelousas, son quartier général reste Port Arthur.

Repéré à Dallas par Chess, l’une des plus importantes maisons de disques indépendantes dans le domaine du blues et du jazz, Chenier enregistre quelques titres en octobre 1956, puis gagne Chicago l’année suivante. Mais il ne s’acclimate pas à la Cité des Vents, d’autant que la promotion de ses disques, malgré un original My Soul remarquable co-écrit avec Etta James rencontrée en tournée en 1955, n’est pas à la hauteur. Revenu au pays, il se fixe à Houston et, toujours très populaire dans la région, anime de nombreux bals et participe à plusieurs séances entre 1958 et 1960 organisées par le producteur Jay D. Miller, à Crowley. Mais là encore, seulement trois singles Zynn, dont It Happened So Fast sont publiés sans grand résultat et Chenier s’estime floué.

Les faces que nous présentons dans ce CD constituent l’essentiel de la première carrière de Clifton Chenier. Elle s’inscrit sous l’étiquette et dans le circuit commercial Rhythm & Blues et, nonobstant l’accordéon qui donne une couleur particulière et originale à sa musique – il joue aussi occasionnellement de l’harmonica –, Clifton Chenier chante essentiellement en anglais, ce qui lui assure une diffusion plus large. Cela ne l’empêche pas de glisser quelques morceaux en français lorsqu’il retrouve les siens, mais, à cette époque, la langue française n’a pas le vent en poupe au pays des bayous et semble même en voie de disparition10.

Or, les choses vont évoluer dans d’autres directions.

Le second départ de Clifton Chenier

Voilà, dans les grandes lignes, comment se dessine le « paysage zydeco » au tournant des années 50/60 lorsque Clifton Chenier revient au pays. Sa carrière marque le pas et il se retrouve un peu au creux de la vague : ses disques récents n’ont pas eu beaucoup d’écho, à cela s’ajoute un changement des genres musicaux et des goûts du public, l’ère des grandes tournées R&B est terminée.

Clifton dissout son orchestre et se réinstalle à Houston. Il était assez déprimé, se souvenait Robert St. Julien qui le rencontra à cette époque (son futur batteur jouait alors avec Rockin’ Dopsee)11. Clifton traverse une période de vaches maigres, et son frère Cleveland a repris un boulot. Enfin, une nuit de l’hiver 1963/64, tandis que l’accordéoniste se produit dans un bar de Houston en compagnie d’un batteur, entre son “beau-frère” Lightnin’ Hopkins qui le présente à Chris Strachwitz, le jeune patron des disques Arhoolie12. Le courant passe et, dès le lendemain, le 8 février 1964, Chenier est invité au studio Gold Star. Mais il arrive avec trois musiciens supplémentaires, ce que n’avait pas prévu ni souhaité le producteur ! Quelques morceaux sont mis en boîte en trio avec l’excellent pianiste texan Elmore Nixon et le batteur Robert « Bob » Murphy13. Un 45 tours sera publié, un autre morceau figurera dans une anthologie, mais ces débuts chez Arhoolie restent timides14.

Strachwitz lui suggère alors de revenir sérieusement à ses racines zydeco. Mais il fallait s’entendre, car Chris visait sa clientèle de blues fans (jeunes, étudiants, blancs), tandis que Clifton ne voulait pas se couper de son public, les danseurs noirs louisianais et texans que ne juraient que par Ray Charles et consorts. On décide de couper la poire en deux et l’on prépare soigneusement une nouvelle séance, en mai 1965, avec une moitié du répertoire en « musique française » comprenant des blues, des valses (Clifton’s Waltz5) et un Zydeco et pas salé avec simplement Cleveland au frottoir et une caisse claire (dans l’esprit des vieux jurés qu’il avait entendus à Port Barré, et comme le jouait son père), et l’autre moitié en orchestre blues/R&B avec notamment une nouvelle version de Eh ‘Tite Fille, un Hot Rod instrumental5 qui reprend, en plus rapide, les riffs de Peter Gunn d’Henry Mancini, et un superbe Louisiana Blues lent5, chanté en français. La séance est une réussite, et l’album “Louisiana Blues and Zydeco” reçoit un très bon accueil dans le sud de la Louisiane et dans l’est du Texas (le premier succès de vente du label Arhoolie !). Chris Strachwitz signe un accord avec le producteur Floyd Soileau, le patron des labels Jin et Maison de Soul, qui édite plusieurs titres en 45 tours sous étiquette Bayou. Le single Louisiana Blues/Hot Rod devient un des favoris des juke-boxes et Robert St. Julien rappelle qu’il a contribué au redémarrage de Clifton, avec des engagements dans le chitlin’ circuit de la Gulf Coast et dans les clubs de l’est du Texas, de Louisiane et de Floride.

Très intelligemment, Clifton Chenier a commencé à opérer le mélange savant, astucieux et unique qui a fait sa réputation et consiste à injecter du blues et des inflexions rhythm and blues/soul dans les chansons traditionnelles et, inversement, à jouer les airs profanes avec le parfum et le feeling low down des bayous ; Zydeco et pas salé en offre un excellent exemple. Ses qualités de musicien, instrumentiste, chanteur et homme de scène ont fait que la recette a pris au-delà des espérances et qu’elle est toujours servie cinquante ans plus tard par tous les orchestres zydeco contemporains !

Ce premier album 33 tours et sa participation au Berkeley Blues Festival en avril 1966 devant un public hippie font entrer le chanteur-accordéoniste dans le circuit du blues revival et il commence à susciter de la curiosité bien au-delà des frontières de l’Amérique francophone, et jusqu’en Europe.

Le mois suivant, en préparation d’une nouvelle séance, Clifton suggère à Chris de faire venir son oncle Big Chenier. Celui-ci arrive avec un violon rafistolé et mal accordé. Qu’à cela ne tienne, tout le monde est ravi et Black Gal/Ma Négresse est une étonnante (et dissonante !) réussite15. Les deux versions de ce blues de 8 mesures, chantées l’une en anglais, l’autre en français5, illustrent l’aisance de Chenier à s’exprimer aussi bien dans les deux langues, quel que soit le type du morceau. Le chanteur reconnait lui-même n’avoir aucune difficulté à interpréter tout type de morceau tant en anglais qu’en français creole. Black Gal, couplé avec l’instrumental Frog Legs sur un single Bayou, plaît tellement qu’il est licencié à Bell Records qui, avec une distribution nationale, en vend de 20 à 30 000 exemplaires. Ce second 33 tours, intitulé « Bon Ton Roulet » et introduit par la reprise du succès de Clarence Garlow, comprend par ailleurs une Sweet Little Doll qui rappelle un peu le Two Step de Eunice d’Amédée Ardoin16, et sa version valsée instrumentale de I Can’t Stop Loving You – clin d’œil à Ray Charles ?

Toujours est-il qu’à partir de ce moment (1967/68), Clifton Chenier écume les clubs de Houston, de Beaumont, de Lafayette (où il a son émission de télévision), de San Francisco, de Los Angeles… Clubs qui, jusqu’à une période récente, sont rarement mixtes, Clifton se produisant aussi bien dans les établissements noirs que dans les blancs.17 Notons aussi que Chenier, croyant et catholique comme la plupart des Louisianais francophones, anime souvent des fêtes au bénéfice des églises, ainsi qu’en témoigne son disque « Live at St. Mark’s » enregistré dans une salle paroissiale (mixte) de Richmond, en Californie, en novembre 1971.

Le couronnement du Roi

Même s’il fera quelques infidélités à Chris Strachwitz (avec son accord bienveillant), Clifton Chenier devient l’artiste-phare d’Arhoolie, et le restera au fur et à mesure que les albums se succéderont, même s’il ne décrochera jamais un contrat avec une major compagnie qui aurait pu lui assurer gloire et fortune18… Mais ces gloires sont souvent éphémères ! Alors que grâce ses nombreux albums, le “King of Zydeco”, comme on l’a couronné, a réussi à faire d’un genre d’expression local, marginal et même méprisé, une forme musicale reconnue et respectée partout. Un large horizon s’ouvre pour lui au-delà des frontières, avec notamment une participation à la fameuse tournée de l’American Folk Blues Festival en 196919, que suivra une retentissante prestation au Festival de Montreux en 1975 en compagnie de son formidable « Red Hot Louisiana Band »20. Il apparaît dans des films : « Dedans le Sud de la Louisiane » de Jean-Pierre Bruneau (1972), « Hot Pepper » qui lui est consacré par Les Blank (1973), des émissions de télévision ; il participe à de nombreux festivals de renom et touche de plus en plus le jeune public : Newport et Ann Arbor (1969), les cinq premiers Festivals Acadiens de Lafayette, le New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival de 1972 à 75… et effectue des tournées au Canada, en Europe et dans le monde entier. Alors qu’il n’avait pas remis les pieds à New York depuis sa brève prestation à l’Apollo il y a plus de vingt ans, Clifton Chenier fait partie d’un programme « Boogie ‘n’ Blues » au Carnegie Hall en 1979 où il attaque avec Jolie Blonde, et est comparé par le New York Times à John Lee Hooker et Lightnin’ Hopkins ! Et, signe de reconnaissance officielle pour lui et pour le zydeco, il est invité en 1984 à jouer à la Maison Blanche.

Très appréciée en France, sa musique avait été utilisée par Alain Corneau pour la bande originale de son premier film, « France Société Anonyme » en 1974. Clifton Chenier était ensuite venu en France durant deux longues périodes : trois semaines au Palace, à Paris, en décembre 1977 (plus divers concerts en banlieue, en province et à l’étranger en janvier 1978), et quinze jours au Théâtre Campagne 1e au printemps 1979.

La suite de sa carrière serait trop longue à résumer et sortirait du cadre “historique” de notre anthologie. Sa popularité sera telle qu’il éclipsera tous ses concurrents pendant deux bonnes décennies. Jusqu’à ce que, à partir de 1979, la maladie l’oblige à ralentir ses activités. Affecté par un diabète qui nécessite la dialyse, Clifton retourne au pays et se réinstalle avec sa femme Margaret. Ensemble, ils ouvrent un club, le CC Club, à Loreauville (paroisse d’Iberia). À l’exception de Cleveland bien sûr, et du fidèle Robert St. Julien, les membres du Red Hot Louisiana Band doivent le quitter ; Joseph Brouchet va jouer avec Hiram Sampy, et Paul Senegal part avec Stanley Dural qui crée son propre orchestre « Buckwheat Zydeco Ils Sont Partis », quant à John Hart, il avait déjà rejoint Rockin’ Dopsie lorsque C.J., le fils de Clifton, avait répondu à l’appel de son père en 1978.

Clayton Joseph Thompson de son vrai nom, est le fils de Clifton et de Mildred Bell. Né à Port Arthur le 28 septembre 1957, il est élevé par sa mère au Texas. Celle-ci n’appartenant pas à la communauté cajun-créole, il ne parle pas français mais apprend très tôt la musique : piano, orgue, saxophone, flûte, tuba. Lorsque son père lui demande de le rejoindre, il ne connait pas grand-chose en zydeco. Il joue d’abord du saxo-alto, puis Clifton, dont la maladie s’aggrave – il a été amputé d’un pied – lui demande d’apprendre l’accordéon pour assurer la continuité et le seconder sur scène. « Mon père a toujours souhaité que je prenne le relais un jour, mais j’étais saxophoniste de jazz. Il voulait absolument que je joue de l’accordéon, et comme avec le temps sa maladie s’aggravait, je débutais de plus en plus souvent les concerts. J’ai appris sur scène, sans prendre de leçons, je le regardais, c’est tout… ».21 Il ouvre le show, parfois avec le chanteur Gene Morris (frère de Joe Brouchet), et devient le directeur musical du nouvel orchestre que Clifton a recruté.

Les dernières années de de la vie et de la carrière de Clifton Chenier sont marquées par une large reconnaissance. Il obtient un Grammy en 1983 pour son album Here ! paru chez Alligator – ce n’est évidemment pas son meilleur mais il est bien distribué et l’on se dépêche toujours de récompenser, en fin de carrière, les gens que l’on a oublié durant leurs années les plus créatives22. Le chanteur-accordéoniste se produit encore au Chicago Blues Festival en 1984, et effectue une tournée dans le Nord-Est du pays jusqu’à Boston. Puis, admis à l’hôpital à Lafayette, il s’éteindra dans cette ville le 12 décembre 1987.

Depuis, C.J. Chenier, qui a repris le « New Red Hot Louisiana Band » et enregistré son premier disque pour Arhoolie en 1988, maintien haut et fort l’héritage et est devenu à son tour une grande vedette internationale du zydeco.

Clifton Chenier fut un grand professionnel, exigeant, tant dans la qualité musicale que dans la présentation de l’orchestre. Très sérieux dans le boulot, ses musiciens reconnaissent que c’était un bon patron – « Si on le prend au bon moment, ça va »23 – et qu’il était agréable de travailler avec lui. « Les gens me demandent comment je peux jouer quatre heures sans m’arrêter. C’est parce que j’ai toujours été un travailleur laborieux. »

La réussite du mix musical original de l’accordéoniste ne serait pas tout-à-fait complète sans l’apport de son frère Cleveland Chenier (né le 16 mai 1921), lequel est aussi un « inventeur », celui du rubboard moderne qui a largement contribué à la couleur de l’orchestre et dont aucun zydeco band actuel ne saurait désormais se passer. C’est Clifton lui-même, en 1946, qui a eu l’idée de ce gilet-frottoir métallique léger qu’un ferblantier de Port-Arthur, Willie Landry, a découpé dans un bidon. Avec un sens très affiné du rythme et un toucher très précis – il joue avec six décapsuleurs à chaque main – Cleveland est reconnu comme l’initiateur de l’instrument et son praticien le plus accompli. Sa vie musicale est restée liée à celle de son frère, même s’il n’est pas toujours présent dans les premiers disques. Il l’a accompagné dès ses débuts mais n’a pas vraiment participé aux tournées R&B. Au tournant des années 50/60 lorsque les engagements se firent rares, il jouait alors volontiers avec Lightnin’ Hopkins dans les environs de Houston. Après la mort de Clifton, il continuera à jouer avec son neveu C.J. jusqu’à son décès le 7 mai 1991.

La conclusion reviendra à Chris Strachwitz qui a tant œuvré pour faire connaître Clifton Chenier : « C’est un réel géant dans son domaine, il n’y a aucun doute là-dessus. Il suffit d’écouter ses douzaines d’imitateurs… Un géant sur son instrument, une grande voix gusty, beaucoup d’expression et d’émotion… Non seulement un artiste unique dans le monde du zydeco, mais un jazzman, un improvisateur. Il chante le blues et joue les airs cajuns mieux que quiconque… Il n’y aura jamais un autre Clifton Chenier ».

Jean BUZELIN

© Frémeaux & Associés 2017

Notes :

1) Interview en français de Clifton et Cleveland Chenier, par Jean Buzelin et Bruno Régnier, le 17 décembre 1977.

2) Son père jouait déjà Les Haricots sont pas salés. Il entend aussi des jurés, une vieille forme d’expression, à Port Barré tout près de chez lui.

3) Orthographe incertaine : Izeb Laza ? Isaie Blaza (M. Tisserand) ? Isée Lazare (G. Schoukroun) ?

4) Morris Chenier serait né en 1929, et mort fin 1977 ou début 78 ; ce qui paraît bien jeune pour se produire à 13 ans à Lake Charles avec ses deux « vieux » neveux. D’après Jean-Claude Arnaudon (Dictionnaire du Blues, Filipacchi, 1977), il aurait appris la guitare à 15 ans, et se serait installé à Lake Charles en 1949. Big Chenier enregistra quelques disques de blues dans cette ville en 1957 et 1960, et ne se serait mis au violon que tardivement. Mais d’après les témoignages des deux frères, tout laisse à penser qu’il était plus âgé. Tenancier de club et de restaurant à Lake Charles, il a toujours pratiqué la musique en amateur et vivait assez chichement. « Quand j’ai abandonné la ferme, dit Cleveland, je suis parti pour Lake Charles travailler dans le bâtiment, et là je suis tombé sur mon oncle Morris Big Chenier. Il jouait du violon avec un groupe et ils m’ont pris avec eux. » (cf. § 23).

5) Voir ZYDECO 1929-1972 (FA 5616).

6) Voici la discographie exacte, embrouillée dans la Blues Discography (Eyeball Productions, Inc., 2012) mais corrigée dans la Zydeco Discography (Eyeball Productions, Inc., 2016) :

- Louisiana Stomp (Elko 920, Imperial 5352) – instrumental ;

- Cliston (Elko 920) ou Clifton’s Blues (Imperial 5352) ;

- Tell Me (Post 2016) ;

- Country Bred (Nobody Loves Me) (Post 2010) ;

- Rockin’ The Bop (Post 2010) – variante un peu plus rapide de Louisiana Stomp ;

- Rockin’ Hop (Post 2016) – instrumental différent, et non un autre titre, de Rockin’ The Bop.

A noter que Just A Lonely Boy, présenté comme inédit sur le LP Imperial 94001 “Rural Blues” paru vers 1968, est exactement le même morceau et la même prise que Clifton’s Blues.

7) Il est peu probable qu’il s’agisse de Robert St. Julien (qu’on appelle parfois Robert Peter) comme indiqué sur les discographies ci-dessus, lequel aurait été bien jeune à l’époque.

8) Interview de Clifton Chenier, par Guy Schoukroun, le 11 décembre 1977.

9) L’instrumental Zodico Stomp, enregistré par Specialty en 1955, ne doit peut-être son titre qu’à son édition tardive sur un LP publié en 1972.

10) La tendance va commencer à s’inverser dans les années 60, avec notamment la création du CODOFIL (Conseil pour le Développement du Français en Louisiane) en 1968, qui agit pour promouvoir la culture et la langue française et va organiser le 1er festival de musique cajun en 1975.

11) Robert St. Julien avait 9 ans quand il vit jouer Chenier pour la première fois lors d’un mariage.

12) Passionné de musiques traditionnelles et folkloriques, d’origine allemande émigré aux Etats-Unis en 1947, Chris Strachwitz souhaite les collecter avant qu’elles ne disparaissent. Circulant dans le vaste territoire texan durant l’été 1960, il enregistre des anciennes « gloires » du blues en panne de carrière comme Lil’ Son Jackson et Black Ace, et fait une rencontre majeure, celle du chanteur-guitariste Mance Lipscomb, un songster exceptionnel. Chris rencontre également Lightnin’ Hopkins qui occupe une place importante dans le mouvement du blues revival, et va l’enregistrer à plusieurs reprises à partir de 1961. Celui-ci lui fait découvrir les petits clubs du french quarter de Houston et les accordéonistes francophones que l’on entend dans notre anthologie ZYDECO (cf. §4).

13) Robert Murphy, batteur texan d’origine créole, rencontra Clifton Chenier à Houston ; il jouait souvent avec lui en duo, et parfois Lightnin’ Hopkins les rejoignait pour quelque petit contrat du dimanche après-midi. Il enregistra plus tard avec le chanteur-guitariste Pete Mayes.

14) Un EP est publié : Ay Ai Ai/Why Did Did You Go Last Night ; les autres titres, dont la première version de I’m The Wonder, sortiront beaucoup plus tard en CD.

15) Il était prévu de renouveler l’opération, mais ce projet ne fut pas réalisé.

16) Voir CAJUN Louisiane 1928-1939 (FA 019).

17) « À l’époque, dans le bayou on se mélangeait pas : les Blancs d’un côté, les Noirs de l’autre. On n’allait pas dans les endroits des Blancs. On pouvait vivre porte à porte, on se mélangeait pas. C’est plus comme ça maintenant. Lorsque je joue pour les jeunes, les hippies et tout ça, je peux jouer tout mon répertoire, mais lorsque je reviens au pays et que je joue pour les vieux, il faut que ce soit strictement cajun ou mon type de zydeco, pas de rock and roll ou de musique de ce genre, ils n’aiment pas ça, ils ne danseront pas, mais si je joue des valses, des “danses gumbo” comme on dit, alors ça va. » (cf. § 8).

18) Les albums Arhoolie de Clifton Chenier, et les autres :

- 1965 : Louisiana Blues and Zydeco

- 1966 : Bon Ton Roulet ©1967

- 1967 : Bayou Soul (Crazy Cajun)

- 1967 : Black Snake Blues ©1969

- 1969 : Clifton’s Cajun Blues (Prophesy) repris par Arhoolie sous le titre Sing the Blues

- 1969/70 : King of the Bayous

- 1971 : Live at a French Creole Dance/at St. Mark’s ©1972

- 1973 : Out West ©1974

- 1975 : Cajun Swamp Music Live (Utopia/Tomato) le concert de Montreux, repris en partie par Arhoolie sous le titre Live at Montreux

- 1975 : Frenchin’ the Boogie (Blue Star) ©1976

- 1975: Bogaloosa Boogie ©1976

- 1975: Boogie and Zydeco (Maison de Soul) ©1977

- 1976 : Boogie in Black and White (Jin) avec Rod Bernard

- 1977: And His Red Hot Louisiana Band

- 1977: On Tour (Paris-Album/EPM)

- 1977/78 : New Orleans (GNP Crescendo)

- 1982 : I’m Here ! (Alligator) obtient un Grammy du « Best traditional or ethnic recording »

- 1982/83 : Live ! ©1985

- 1984 : Country Boy (Caillier)

- 1985 : King of Zydeco (Flat Town/Ace)

19) Je me souviens encore de son apparition, accordéon en bandoulière, sur la scène de la Salle Pleyel, et présentant Cleveland et Robert ainsi : « ça c’est mon frère, et ça c’est mon tambour » devant un public stupéfait.

20) Outre son frère Cleveland et son « tambour » Robert St. Julien (ou St. Judy), son Red Hot Louisiana Band était composé à l’époque de Paul Senegal (guitare), et Joseph Brouchet, dit Jumpin’ Joe Morris (basse), auxquels on ajoutera John Hart (saxo ténor) – les six enregistrent « Bogaloosa Boogie », considéré comme le meilleur album de Chenier, en octobre 1975 – et Stanley “Buckwheat” Dural (claviers) qui n’étaient pas à Montreux, mais à Paris deux ans plus tard ; cet orchestre est probablement le meilleur jamais réuni par Clifton Chenier.

21) Interview de C.J. Chenier, par Daniel Léon, le 28 mars 2014.

22) Un Grammy Award lui a été décerné, à titre posthume en 2004, pour l’ensemble de son œuvre.

23) Interview de Clifton et Cleveland Chenier, par Guy Schoukroun, le 18 janvier 1978.

Ouvrages consultés :

John Broven, South to Louisiana (Pelican Publishing Company, 1987)

Robert Sacré, Musiques Cajun, Créole et Zydeco (Que sais-je?, Presses Universitaires de France, 1995)

Ann Savoy, Cajun Music, a reflexion of a people (Bluebird Press, Inc., 1998)

Michael Tisserand, The Kingdom of Zydeco (Arcade Publishing Inc., 1998)

Articles :

Jacques Demêtre, Clifton Chenier (Jazz Hot N°292, mars 1973)

Robert Sacré, Clifton & Cleveland Chenier + Jean Buzelin & Bruno Régnier, interview (Jazz Hot N°345/46, février 1978)

Jacques Demêtre, Le Zydeco + Patrick Lobstein, Discographie de Clifton Chenier (Soul Bag N°71, 1978)

Joseph F. Lomax, Zydeco vivra ! + Guy Schoukroun, Clifton Chenier, roi du bayou, interview (Jazz Magazine N°278, septembre 1979)

Robert Sacré, Dedans le Sud-Ouest de la Louisiane + Patrick Lobstein, Clifton Chenier + Guy Schoukroun, L’interview (Soul Bag N°77, 1979)

Disques originaux : coll. Jean Buzelin, Philippe Sauret

Photos et collections : Jean-Pierre Bruneau, Jean Buzelin, Tyrone Glover, Ann Savoy, Chris Strachwitz, X (D.R.)

Remerciements particuliers à Jean-Pierre Bruneau

CLIFTON CHENIER

KING OF ZYDECO

The Rhythm and Blues Years 1954-1960

By Jean Buzelin

A black child from the bayou

Born on June 25th 1925 on the banks of the Bayou Teche in Notelyville near Opelousas, Clifton Chenier was of mixed black and Indian blood, and he was put to work at an early age on the family farm, together with his elder brother Cleveland. On Saturday nights his father Joseph would play “Acadian airs”1 on the accordion at dances held in neighbours’ homes; the young Clifton was very interested… it became an irresistible vocation in music when some local accordion “stars” — Claude Faulk, the brothers Jesse and Zo Zo Reynolds — stopped at the house one day on their way to play locally. There were also other amateur accordion champions who lived nearby, among them his great-uncle Peter King, his cousin Carlton King, Frank Andrus and Sidney Babineaux. It was then that his father began to let him play at events outside town — “When I was 15 my father didn’t show me, but me, I listened.”2 Cleveland accompanied him, with his mother’s washboard on his lap. “They held dances at their houses,” said Cleveland. “Saturday nights, Sunday afternoons, we’d eat and start to dance; everyone spoke French, and we’d all eat together over there.”1

Clifton abandoned his single-note Melodeon in 1941 when a certain Isaïe Blaza3 lent him a chromatic piano accordion at a dance in Opelousas. It was made by Hohner (Blaza later gave it to Clifton) and the consequences on the evolution of Clifton’s style were enormous.

In 1942, while working as a farm hand in Loreauville, he joined his brother in Lake Charles to play with their young uncle, Morris “Big” Chenier (a guitarist and violinist),4 in clubs and dance halls. Then in 1945, after a detour via New Iberia and its sugar cane plantations, the two brothers abandoned farm-work and emigrated to Port Arthur close to the Texas border, where they found better-paid jobs in the oil industry. “When I was in Acadie,” said Clifton, [it was the name they used then for the Cajun region], “I picked corn, potatoes… and after that I worked at the Gulf refinery.” 1 During their free time they built up their songbook with current songs (like Joe Liggins’ The Honeydripper, a big hit at the time) that they played in local clubs like the Blue Moon, or on Mondays and Tuesdays at the Bon Ton Drive-In, a club run by Clarence Garlow5 in Beaumont, Texas, a neighbouring town just northwest of Port Arthur. Clifton and his brother would live in this border town from 1947 to 1955, returning to Basile or Lawtell at weekends. In the meanwhile, Clifton married Margaret Young.

Clifton Chenier’s great debut

Clifton wanted to make a name (and a place) for himself in music, and cultivated his image and shows; he formed the “Hot Sizzling Band” with Lee Baker on guitar, the future Lonnie Brooks. He was playing in Port Arthur in 1954 when J.R. Fullbright, the black owner of the little Elko label, noticed him and offered Clifton the chance to make a record. Among the six pieces6 they recorded at radio KAOK’s Lake Charles studios was Cliston Blues (sic), sung in English by “Cliston Chanier” (as it appeared on the label), which was sold to Imperial, a much larger label that could distribute the title more widely. Without Cleveland, but with Big Chenier on guitar and a drummer by the name of Robert Pete7, the piece ranks as the first real blues with a classical form to be recorded on an accordion. Fullbright invited Clifton to live at his home in Los Angeles (music had quite another dimension out on the West Coast), and the singer-accordionist started appearing in clubs and dance halls like the 5-4 Ballroom.

But not without some difficulty: “In Los Angeles things didn’t work out too bad, but in Oakland or Frisco it didn’t take on. In Los Angeles there were a whole lot of people from Louisiana who knew that music. It was hard; I can’t stop thinking about it. Sometimes they even made fun of me, they said, ‘Ha, he’s playing that old accordion, it ain’t worth a damn’… We used to go and see people, ask if we could play at some dance, – ‘Play what?’ – ‘Accordion.’ – ‘No, we don’t want that here.’” 8

That would all change the following year. They quickly gave him the nickname “King of the South” and he signed in April ’55 with a solid independent label, Specialty in Hollywood. He immediately had a regional hit with Ay-Tete-Fee (Hey ‘tite fille), a “French” song of a new kind that he sang in both languages. Because Clifton showed people he was a blues/soul singer of great talent, sounding inhabited and persuasive, and with a voice that was slightly veiled. He spoke both languages perfectly, but his French accent was very strong, making his singing-voice deliciously colourful. His robust, entertaining music even allowed him to obtain a surprise success in Jamaica with Squeeze-Box Boogie.

After Clarence Garlow and Boozoo Chavis5, Clifton Chenier became the third Zydeco artist to make records, but whereas the first essentially played a blues/R&B hand, and the second, having stayed close to rural music, didn’t make a career of it, Chenier went back to his roots and drew on his tastes, experience and culture to concoct a spicy musical gumbo that was totally original. It was a mixture of blues, boogie-woogie, dance tunes and pop songs with a dash of country and western, plus a couple of essential ingredients: two-steps and waltzes, the perfect mix that determined the “zydeco genre” and gave it direction for decades.

And Clifton would be everywhere! From then on, the history of zydeco would be the history of Clifton Chenier, even though the word hadn’t yet been “written.”9 “I started playing zydeco, not Cajun dances. I played Cajun but I learned zydeco; I kept on with zydeco and blues. I know the Cajun dances but zydeco a lot more, it’s as different from Cajun music as Jolie Blonde and two-steps.”1 For a long time he would be considered the sole representative of the music genre that he had in fact invented. But it wasn’t that untrue, either: Clifton had no serious competition.

After his return to Louisiana he was something of a star in R&B — meaning only amongst black people, and not outside the States between Louisiana and California — and he toured with singer-guitarist Lowell Fulson, then at the height of his fame, for months on end, playing in “package shows” that had several artists, bands or orchestras on the same bill; it gave Clifton occasion to cross paths with stars like Lloyd Price, Fats Domino, Chuck Berry, Jimmy Reed, Rosco Gordon, Johnny “Guitar” Watson, The Cadillacs and The Dells... He gained a lot of professionalism, and it was reflected in his show, where he led an excellent band of seven or eight including Philip Walker (from June ’53 to 1957) and, more briefly, Lonesome Sundown. These two “black Cajun” blues guitarists would enjoy their own separate careers later. Chenier covered the Midwest, played in Indiana and as far as New York (once appearing at Harlem’s famous Apollo), and was also a familiar sight in the clubs of Houston, Dallas, Oklahoma City or Lafayette, etc. Opelousas remained “home” to him, but his headquarters remained Port Arthur.

Chess was one of the most important record companies for blues and jazz, and Chess spotted his talent in Dallas. He recorded a few titles in October ’56 and then went to Chicago in ’57. But he didn’t feel at home in the Windy City, all the more since the promotion of his records left something to be desired, despite the remarkable success of his original title My Soul, co-written with Etta James whom he met on tour in 1955. Back in Texas he settled down in Houston; he was still very popular throughout the region and found work at many dance halls, also taking part from 1958 to 1960 in numerous sessions set up by producer Jay D. Miller. But there again, only three singles were released (by Zynn), among them It Happened So Fast, and they didn’t sell. Chenier thought he’d been taken for a ride.

The sides included in this CD form the essence of Clifton’s first career. These are considered Rhythm & Blues pieces, both as a category and as part of that market for sales, notwithstanding the presence of the accordion, which gives a particularly original colour to his music. He also plays harmonica occasionally, and sings mostly in English, which ensured he was distributed on a wider basis. That didn’t stop him slipping a few French pieces into his work when he was singing in front of his own folks but, at the time, French wasn’t in vogue around the bayous, and even seemed condemned to die out.10 Things were to develop in other directions, however.

A second start for Clifton Chenier

The above is a broad portrait of the zydeco landscape at the turn of the Fifties when Clifton Chenier returned home. His career was in neutral and he found himself closer to the ebb of the wave: his recent records hadn’t met with much success; music genres (and public tastes) were changing; and the great age of R&B tours was over. Clifton disbanded and went to live in Houston. According to Robert St. Julien, who met him at the time — before becoming his drummer, Robert was playing with Rockin’ Dopsee11 — Clifton was depressed, times were lean, and to cap it all, Cleveland Chenier had found another job. One night in the winter of 1963/64, the accordionist was playing in a Houston bar, accompanied by just a drummer. Then Clifton’s “brother-in-law” Lightnin’ Hopkins came in with Chris Strachwitz, the young owner of the Arhoolie label12 and introduced him to Clifton. They got on well. The next morning (February 8th, 1964) Clifton Chenier received an invitation to Gold Star studios, but went over with three musicians; the producer hadn’t planned on this (or even wanted it!) They taped a few pieces as a trio — Clifton, the excellent Texan pianist Elmore Nixon and drummer Robert “Bob” Murphy13 —, resulting in the release of a 45rpm single; another title appeared in a compilation, but it was still a timid beginning with Arhoolie.14

Then Strachwitz suggested that Clifton should seriously consider going back to his zydeco roots, but they would have to compromise: Chris was aiming for a market of blues fans (White youngsters and students) whereas Clifton didn’t want to cut himself off from his own audience — Blacks and dancers from Louisiana and Texas who swore by Ray Charles and his kind. They decided to go halves. A new session was put together for May 1965: half the repertoire was “French music”, including blues, waltzes (Clifton’s Waltz5) and the title Zydeco et pas salé (accompanied by Cleveland’s washboard and a snare-drum, in the old a cappella juré style he’d heard in Port Barre and in which his father played); the other half of the tunes were orchestral blues/R&B, with notably a new version of Eh ‘Tite Fille, the instrumental Hot Rod 5 which picked up Henry Mancini’s Peter Gunn riffs (only faster), and the superb slow Louisiana Blues5, sung in French. The session was a great success and the album “Louisiana Blues and Zydeco” received an excellent reception in southern Louisiana and the east of Texas (it was the Arhoolie label’s first hit!) Strachwitz signed an agreement with producer Floyd Soileau; he ran the “Jin” and “Maison de Soul” labels, and he released several titles as 45s on the Bayou label. The single Louisiana Blues/Hot Rod became a jukebox hit and Robert St. Julien remembers contributing to Clifton’s new launch, with gigs on the famous chitlin’ circuit on the Gulf Coast, and in clubs in eastern Texas, Louisiana and Florida.

Clifton Chenier cleverly began applying the astute, unique mixture that earned him his reputation; he injected blues and R&B/Soul inflexions into traditional songs, but also played common tunes with a low-down feeling that smacked of the bayous. Zydeco et pas salé is an excellent example. His qualities as an instrumentalist, singer and stage-performer resulted in his recipe being a success he hadn’t even hoped for, and contemporary zydeco bands still serve it up today, fifty years later! His first album and his Berkeley Blues Festival concert in April ’66 for an audience of hippies introduced the singer/accordionist to the “blues revival” circuit, which in turn began arousing curiosity well beyond the borders of French-speaking America, and all the way to Europe.

The following month, while preparing a new session, Clifton suggested to Chris that he should ask his uncle Big Chenier to join them. The latter arrived with a beat-up violin that needed tuning… Not that it mattered: everyone was delighted and Black Gal/Ma Négresse was an astonishing (and dissonant!) success.15 Both versions of this 8-bar blues, one sung in English and the other in French,5 illustrate how easily Chenier expressed himself in the two languages, no matter what type of piece it was. As for the singer, he recognized he’d never had any difficulty with either English or Creole French. Black Gal, paired with the instrumental Frog Legs on a Bayou-label single, pleased everyone so much that it was licensed to Bell Records, which sold between twenty and thirty thousand copies thanks to its national distribution. The second 33rpm disc entitled “Bon Ton Roulet”, which was introduced by a cover of the Clarence Garlow hit, also contained a Sweet Little Doll reminiscent of the Two Step de Eunice by Amédée Ardoin;16 an how about his waltzed instrumental version of I Can’t Stop Loving You – was that a nod in Ray Charles’ direction, perhaps?

From this moment on (1967/68), Clifton Chenier spent most of his time in the clubs: Houston, Beaumont, Lafayette (where he had his own TV show), San Francisco or Los Angeles… Until recently, those clubs had rarely been “mixed”, with Clifton appearing in venues that were either White or Black.17 Also worth noting is the fact that Chenier, a religious man (and a Catholic) like most French-speakers in Louisiana, often played at Church events and celebrations, as evidenced by his record “Live at St. Mark’s” which was recorded in a (mixed) parish hall in Richmond, California, in November ’71.

The crowning of the King

Even if he was unfaithful to Chris Strachwitz now and again (but with the latter’s blessing), Clifton Chenier became Arhoolie’s leading artist and remained the label’s N°1 as and when his albums were released, even though he never secured a contract with a major company likely to ensure “fame and fortune”18… But such fame was often short-lived anyway! Thanks to his numerous albums, the “King of Zydeco”, as he was crowned, succeeded in transforming a local, marginal (and often scorned) music genre into a form that was recognized and respected everywhere. A vast horizon opened up for him that knew no borders, notably when he took part in the American Folk Blues Festival tour in 1969.19 And that was followed by an appearance with an enormous impact at the 1975 Montreux Festival, where he was accompanied by his great “Red Hot Louisiana Band”.20 He appeared in films — Jean-Pierre Bruneau’s “Dedans le Sud de la Louisiane” (1972), Les Blank’s “Hot Pepper” (1973) —, televisions shows and numerous well-known festivals that were reaching more and more young people: Newport and Ann Arbor (1969), the five first Acadian Festivals in Lafayette, the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival from 1972 to ‘75… and also toured internationally. Clifton hadn’t set foot in New York since his brief Apollo appearance in the late Fifties, and twenty years later he found himself at Carnegie Hall (1979) on the bill of “Boogie ‘n’ Blues” (he kicked off with Jolie Blonde). The New York Times compared him with John Lee Hooker and Lightnin’ Hopkins… In 1984 the White House invited him to play there; it was seen as official recognition for both him and zydeco.

He was very popular in France, too; in 1974 filmmaker Alain Corneau used his music in the soundtrack of his first film “France Société Anonyme”, and Clifton later enjoyed two extended stays in the country: a three-week residency at the Palace venue in Paris in December ’77 (with also concerts both in France and abroad in the following January), and two weeks at the Campagne 1er Theatre in the spring of ’79. The rest of his career falls outside the ‘historic” scope of this set but his popularity still eclipsed that of his competitors for a good two decades. Illness, however, obliged Clifton to reduce his schedule beginning in 1979, as he suffered from diabetes and had to undergo dialysis; he returned home and settled down with his wife Margaret again. They opened a club together, the CC in Loreauville (in the Parish of Iberia). With the exception of Cleveland, of course, and the loyal Robert St. Julien, the other members of the Red Hot Louisiana Band were to leave him; Joseph Brouchet went to play with Hiram Sampy, and Paul Senegal left with Stanley Dural, who set up his own band called “Buckwheat Zydeco Ils Sont Partis”; as for John Hart, he’d already moved to join Rockin’ Dopsie in 1978, when Clifton’s son C.J. answered his father’s call.

Clayton Joseph Thompson is the real name of the son of Clifton and Mildred Bell, born in Port Arthur on September 28th 1957. His mother came from a Cajun-Creole community and raised him in Texas, so he didn’t speak French. But he did learn music from an early age: piano, organ, saxophone, flute and tuba. When his father asked him to join him, he didn’t know much of zydeco. First he played alto saxophone, and then Clifton — whose illness had become more serious, making it necessary to amputate his foot — asked him to take up the accordion for continuity’s sake and also assist him onstage. “My father always wanted me to take over one day, but I was a jazz saxophone player. He absolutely wanted me to play accordion, and since his illness was getting worse as time went by, I was starting his concerts more and more. I learned onstage without any lessons; I just watched him, that’s all…” 21 He’d open the show, sometimes with singer Gene Morris (Joe Brouchet’s brother), and he became music director of the new band that Clifton founded.

The last years of the life and career of Clifton Chenier were marked by his widespread recognition. He won a Grammy in 1983 for his album Here! released by Alligator – it certainly wasn’t his best work, but it was well distributed and people always hurry to reward artists approaching the end of their careers, especially when those artists have been overlooked in their most creative periods.22 The singer & accordionist appeared again at the Chicago Blues Festival in 1984, and made a tour in the northeast that took in Boston. In 1987 he was admitted into hospital in Lafayette, where he died on December 12th. Since then, C.J. Chenier has taken over the “New Red Hot Louisiana Band”, making his first record for Arhoolie in 1988, and he has maintained the famous legacy; today he is an international zydeco star in his own right.

Clifton Chenier was a great professional who demanded quality from his musicians in both the music they played and in the band’s presentation. They were serious when they worked and they recognized he was a good boss — “If you catch him at the right time, that’s fine”23 – and pleasant to work with. “People ask me how I can play four hours non-stop; it’s because I’ve always been a hard worker.”

The success of the original “mix” in the accordionist’s music wouldn’t have been quite complete without the contribution of his brother Cleveland Chenier (born May 16th 1921) who was also an “inventor”: in his case the invention was the modern rub-board) that largely added to the band’s colour, and without which no zydeco band could manage today. It was Clifton himself who, in 1946, had the idea of using this light, washboard-like metal breastplate which Willie Landry, a tinsmith in Port Arthur, cut from a metal barrel. With a fine sense of rhythm and a very precise touch, Cleveland — he played with six bottle-openers in each hand — was recognized as the initiator of the instrument and its most accomplished practitioner. His life in music has remained linked with that of his brother, even though he wasn’t always present on his first recordings. He accompanied him right from the beginning, but didn’t really take part in the R&B tours. At the turn of the Fifties and Sixties when gigs were scarce, Cleveland played often with Lightnin’ Hopkins around Houston, and after Clifton died he continued to play with his nephew C.J. until his own death on May 7th 1991.

The last word goes to Chris Strachwitz, who did so much to make Clifton Chenier known: ”Clifton is a giant on his instrument – no one comes close – he has a great gutsy voice and a very expressive and emotional delivery when he feels like it (…). Clifton is not only a unique artist in the zydeco field, but a jazzman, an endless improviser. He sings the blues and he can do Cajun numbers better than anyone else (…) there will never be another Clifton Chenier.”

Jean BUZELIN

English Adaptation: Martin Davies

© Frémeaux & Associés 2017

Notes

1) From an interview (in French) with Clifton & Cleveland Chenier by Jean Buzelin and Bruno Régnier, December 17th 1977.

2) His father used to play Les Haricots sont pas sales already; he also heard jurés, an old form of expression, in Port Barré close to his home.

3) The spelling is uncertain: Izeb Laza? Isaie Blaza? (M. Tisserand). Isée Lazare? (G. Schoukroun).

4) Morris Chenier was supposedly born in 1929, with his death placed at the end of 1977 or early 1978. That would mean he was 13 when he played in Lake Charles with his two “old” nephews, which seems rather young… According to Jean-Claude Arnaudon (Dictionnaire du Blues, Filipacchi, 1977), he supposedly learned the guitar at 15 and settled in Lake Charles in 1949. Big Chenier recorded a few blues there in ’57 and ’60, only later taking up the violin. But accounts from the two brothers suggest he was older. A club and restaurant owner in Lake Charles, he always played music as an amateur and lived modestly. “When I abandoned the farm,” said Cleveland, “I went to Lake Charles to work in construction, and there I bumped into my uncle, Morris ‘Big’ Chenier. He was playing violin with a band and they took me with them.” Cf. (23)

5) Cf. “Zydeco 1929-1972” (FA 5616).

6) Here’s the precise discography (confusing in The Blues Discography, Eyeball Productions Inc., 2012 but corrected in The Zydeco discography, Eyeball Productions Inc., 2016):

- Louisiana Stomp (Elko 920, Imperial 5352) – instrumental;

- Cliston (Elko 920) or Clifton’s Blues (Imperial 5352);

- Tell Me (Post 2016);

- Country Bred (Nobody Loves Me) (Post 2010);

- Rockin’ The Bop (Post 2010) – a slightly quicker variant of Louisiana Stomp;

- Rockin’ Hop (Post 2016) – not another title but a different, instrumental Rockin’ The Bop. Note that Just A Lonely Boy, presented as previously unreleased on the Imperial LP “Rural Blues” (ref. 94001) published around 1968, is exactly the same piece, and the same take, as Clifton’s Blues.

7) It’s unlikely that this was Robert St. Julien (sometimes called Robert Peter) as indicated in the above discographies; he would have been really young at the time...

8) In an interview with Clifton Chenier by Guy Schoukroun, 11th December 1977.

9) Perhaps the instrumental Zodico Stomp, recorded by Specialty in 1955, only owes its title to its belated release on an LP published in 1972.

10) The trend was reversed beginning in the Sixties, notably with the creation of CODOFIL (Council for the Development of French in Louisiana) in 1968, whose actions promoted French culture and the language; it organized the 1st Cajun music festival in 1975.

11) Robert St. Julien was nine when he saw Chenier playing for the first time at a wedding.

12) Chris Strachwitz had a passion for traditional and folk music. He emigrated from Germany to the USA in 1947, wanting to collect these music forms before they disappeared. Travelling through Texas in the summer of 1960, Strachwitz recorded old blues “Greats” whose careers had been interrupted — Lil’ Son Jackson, Black Ace — and had a major encounter with singer-guitarist Mance Lipscomb, an exceptional songster. He also met Lightnin’ Hopkins, important in the blues revival movement, and recorded him several times starting in 1961. Hopkins introduced him to the little clubs in Houston’s French Quarter, where he discovered the French-speaking accordionists who appear in the Zydeco anthology. Cf. (4)

13) Robert Murphy, a Texan drummer of Creole origin, met Clifton Chenier in Houston; he often played with him as a duo, and sometimes Lightnin’ Hopkins joined them for a gig on Sunday afternoons. He would record later with singer-guitarist Pete Mayes.

14) One EP was released: Ay Ai Ai/Why Did You Go Last Night; the other titles, including the first version of I’m The Wonder, would be published much later on CD.

15) Another operation was planned but didn’t come to fruition.

16) Cf. Cajun Louisiane 1928-1939 (FA 019).

17) “At the time, we didn’t mix in the bayous: Whites on one side, Blacks on the other. We didn’t go to White places. We could be living door-to-door: we didn’t mix. It’s not like that anymore. When I play for young people, hippies and all that, I can play my whole repertoire, but when I come back home and play for old people, it has to be strictly Cajun or my type of zydeco, no rock and roll or music of that type, they don’t like it and they won’t dance; but if I play waltzes, “gumbo” dances like they call it, then that’s fine.” Cf. (8)

18) The Arhoolie albums by Clifton Chenier, and the others:

- 1965: Louisiana Blues and Zydeco

- 1966: Bon Ton Roulet ©1967

- 1967: Bayou Soul (Crazy Cajun)

- 1967: Black Snake Blues ©1969

- 1969: Clifton’s Cajun Blues (Prophesy) picked up by Arhoolie under the title Sing the Blues

- 1969/70: King of the Bayous

- 1971: Live at a French Creole Dance/at St. Mark’s ©1972

- 1973: Out West ©1974

- 1975: Cajun Swamp Music Live (Utopia/Tomato); the Montreux concert partially picked up by Arhoolie under the title Live at Montreux

- 1975: Frenchin’ the Boogie (Blue Star) ©1976

- 1975: Bogaloosa Boogie ©1976

- 1975: Boogie and Zydeco (Maison de Soul) ©1977

- 1976: Boogie in Black and White (Jin) with Rod Bernard

- 1977: And His Red Hot Louisiana Band

- 1977: On Tour (Paris-Album/EPM)

- 1977/78: New Orleans (GNP Crescendo)

- 1982: I’m Here! (Alligator) won the Grammy for “Best traditional or ethnic recording.”

- 1982/83: Live! ©1985

- 1984: Country Boy (Caillier)

- 1985: King of Zydeco (Flat Town/Ace)

19) I can still remember him coming onstage at Salle Pleyel with his accordion slung over his shoulder to introduce Cleveland and Robert by saying, “This one’s my brother, and this one’s my drum.” The audience was dumbstruck.

20) Apart from his brother Cleveland and his “drum” Robert St. Julien (or St. Judy), his Red Hot Louisiana Band at the time was comprised of Paul Senegal (guitar) and Joseph Brouchet, aka Jumpin’ Joe Morris (bass) plus John Hart (tenor sax) – the six of them recorded “Bogaloosa Boogie”, considered Chenier’s best album, in October 1975 – and also Stanley “Buckwheat” Dural (keyboards) who wasn’t in Montreux but was in Paris two years later; this band is probably the best that Clifton Chenier ever put together.

21) Interview with C.J. Chenier by Daniel Léon, 28th March 2014.

22) He received a posthumous Grammy Award in 2004 for his contribution to music.

23) Interview with Clifton & Cleveland Chenier by Guy Schoukroun, 18th January 1978.

Works consulted

John Broven, South to Louisiana (Pelican Publishing Company, 1987), Robert Sacré, Musiques Cajun, Créole et Zydeco (Que sais-je? Presses Universitaires de France, 1995), Ann Savoy, Cajun Music, a reflexion of a people (Bluebird Press, Inc., 1998), Michael Tisserand, The Kingdom of Zydeco (Arcade Publishing Inc., 1998)

Articles

Jacques Demêtre, Clifton Chenier (Jazz Hot N°292, March 1973), Robert Sacré, Clifton & Cleveland Chenier + Jean Buzelin & Bruno Régnier, interview (Jazz Hot N°345/46, Feb. 1978), Jacques Demêtre, Le Zydeco + Patrick Lobstein, Discographie de Clifton Chenier (Soul Bag N°71, 1978), Joseph F. Lomax, Zydeco vivra! + Guy Schoukroun, Clifton Chenier, roi du bayou, interview (Jazz Magazine N°278, September 1979), Robert Sacré, Dedans le Sud-Ouest de la Louisiane + Patrick Lobstein, Clifton Chenier + Guy Schoukroun, L’interview (Soul Bag N°77, 1979)

Original recordings: courtesy of Jean Buzelin, Philippe Sauret

Photos and collections: Jean-Pierre Bruneau, Jean Buzelin, Tyrone Glover, Ann Savoy, Chris Strachwitz, X (D.R.)

Special thanks to Jean-Pierre Bruneau

1. LOUISIANA STOMP (C. Chenier) 920A

2. CLISTON BLUES (JUST A LONELY BOY) (C. Chenier) 920B

3. TELL ME (C. Chenier) IM 870N

4. COUNTRY BRED (NOBODY LOVES ME) (J.R. Fullbright) IM 871

5. ROCKIN’ HOP (C. Chenier) IM 935N

6. AY-TE TE FEE (EH, PETITE FILLE) (C. Chenier) SP-552X

7. BOPPIN’ THE ROCK (C. Chenier) SP-552

8. THINK IT OVER (W.E. Buyem = H.D. Nelson) SP-556

9. THE THINGS I DID FOR YOU (C. Chenier) SP-556X

10. ALL NIGHT LONG (C. Chenier) SP-2139

11. YESTERDAY (I LOST MY BEST FRIEND) (C. Chenier) SP-2139

12. (CLIFTON’S) SQUEEZE-BOX BOOGIE (C. Chenier) SP-568X

13. THE CAT’S DREAMIN’ (C. Chenier) SP-568

14. BABY PLEASE (C. Chenier) 8330

15. WHERE CAN MY BABY BE (STANDING IN THE CORNER) (C. Chenier) 8331

16. THE BIG WHEEL (SQUEEZE BOX SHUFFLE) (C. Chenier) 8333

17. MY SOUL (E. James, C. Chenier) 8569

18. BAYOU DRIVE (SLOPPY) (C. Chenier) 8568

19. IT HAPPENED SO FAST (C. Chenier) Z 7452

20. GOODBYE BABY (C. Chenier) Z 7453

21. HEY MA MA (C. Chenier) Z 7477

22. WORRIED LIFE BLUES (M. Merriweather) Z 7476

23. NIGHT AND DAY MY LOVE (C. Chenier) Z 7488

24. ROCKIN’ ACCORDIAN (C. Chenier) Z 7489

(1-5) Cliston Chanier “King of the South” (1-2): Clifton Chenier (acd, vo except on 1, 5), Morris “Big” Chenier (g), Robert Pete (dm). Lake Charles, LA, 1954.

(6-9) Clifton Chenier & His Band (6-7): Clifton Chenier (acd, vo except on 7), James K. Jones (p), Philip Walker (g), Louis “Francis” Candy (b), Wilson Semien (dm), Cleveland Chenier (rbd). Los Angeles, CA, 04/1955.

(10-13) Clifton Chenier (acd, vo on 10, 11)), Lionel “Torrence” Prevost (ts), James K. Jones (p), Philip Walker, Cornelius Green “Lonesome Sundown” (g), Louis Candy (b), Wilson Semien (dm), Cleveland Chenier (rbd), ensemble vo. Los Angeles, CA, 09/09/1955.

(14-16) Clifton Chenier (acd, vo on 14, 15), Lionel Prevost, B.G. Jones (sax on 14, 15), James K. Jones (p), Philip Walker (g), Louis Candy (b), Wilson Semien (dm). Dallas, TX, ca. 10/1956.

(17-18) Same, but unknown (tb) added; Chenier (vo on 17), Etta James, Philip Walker (background vo on 17). Chicago, IL, 08/1957.

(19-20) Clifton Chenier (acd, vo), Lionel Prevost (ts), James K. Jones (p), Philip Walker (g), Louis Candy (b), Wilson Semien (dm). Crowley, LA, 1958.

(21-22) Clifton Chenier (acd, vo), Lionel Prevost (ts on 22), Travis Phillips (g), Louis Candy (b), Wilson Semien (dm). Crowley, LA, 04/05/1959.

(23-24) Same or similar; Chenier (vo on 23). Crowley, 1960.

Formidable chanteur et accordéoniste noir américain, Clifton Chenier a su forger un genre musical à part entière, le Zydeco, dont il fut pendant longtemps considéré comme l’unique représentant. Née dans les années 30, cette musique est le fruit de la rencontre entre les cultures créoles et cajuns de la Louisiane francophone. Lorsque Chenier s’en empare, c’est un genre marginal et méprisé par le mainstream américain. Quelques années plus tard, grâce à de nombreux albums et succès, le « King of Zydeco », comme on le surnomme alors, est parvenu à faire de cette musique une forme d’expression accomplie appréciée de tous. L’anthologie réalisée par Jean Buzelin propose de suivre l’histoire de ce couronnement, entre 1954 et 1960. Après avoir approché quelques titres dans l’album « Zydeco, 1929-1972 » (FA5616), Frémeaux & Associés est fier de mettre en lumière l’œuvre et le génie d’un artiste entré dans la légende.

Patrick Frémeaux

A marvellous black American singer and accordionist, Clifton Chenier succeeded in forging a style all his own, Zydeco, and for a long time he was considered its sole representative. Born in the 30s, the music came from mixed Creole and Cajun cultures in French-speaking Louisiana; when Chenier took hold of the genre it was marginal and mocked by mainstream America, but in just a few years, with a series of hit albums, the man they called the “King of Zydeco” turned the music into an accomplished form of expression that everyone appreciated. This anthology from Jean Buzelin follows the history of this King’s coronation between 1954 and 1960. After the titles already featured in the album “Zydeco, 1929-1972” (FA5616), Frémeaux & Associés is proud to highlight the work and genius of this legendary artist.

Patrick Frémeaux

1. LOUISIANA STOMP 2’50

2. CLIFTON’S BLUES 3’11

3. TELL ME 2’16

4. COUNTRY BRED 2’35

5. ROCKIN’ HOP 2’04

6. EH, PETITE FILLE 2’42

7. BOPPIN’ THE ROCK 2’22

8. THINK IT OVER 2’28

9. THE THINGS I DID FOR YOU 2’51

10. ALL NIGHT LONG 2’18

11. YESTERDAY 2’51

12. SQUEEZE-BOX BOOGIE 1’58

13. THE CAT’S DREAMIN’ 2’10

14. BABY PLEASE 2’28

15. WHERE CAN MY BABY BE 2’40

16. THE BIG WHEEL 2’50

17. MY SOUL 2’53

18. BAYOU DRIVE 2’55

19. IT HAPPENED SO FAST 2’24

20. GOODBYE BABY 3’13

21. HEY MA MA 2’05

22. WORRIED LIFE BLUES 2’12

23. NIGHT AND DAY MY LOVE 2’44

24. ROCKIN’ ACCORDIAN 2’16