- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

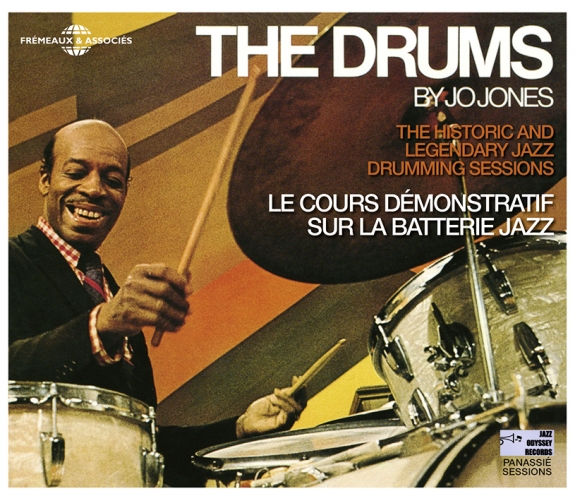

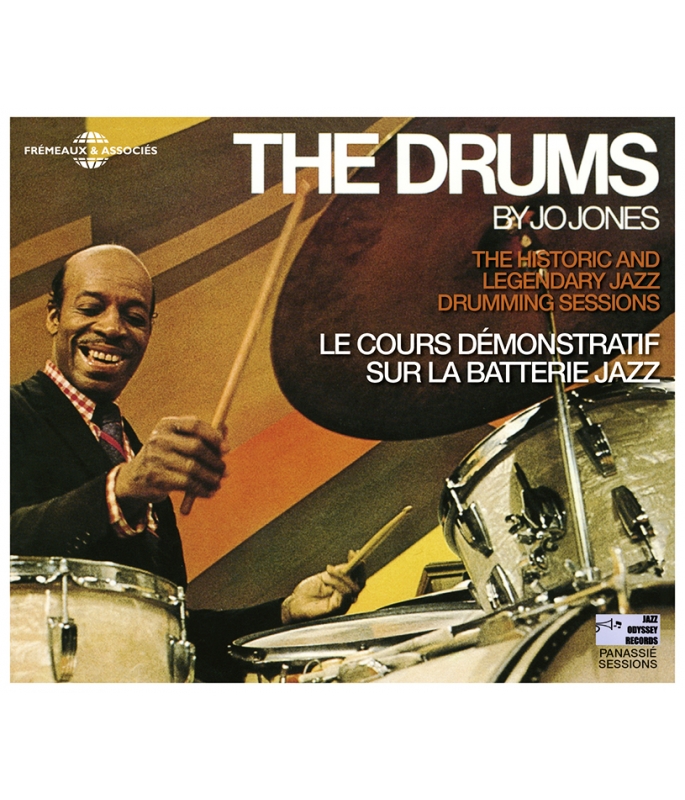

THE PRACTICE CLASS OF DRUM JAZZ

JO JONES

Ref.: FA5672

Artistic Direction : LAURENT VERDEAUX

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Total duration of the pack : 1 hours 50 minutes

Nbre. CD : 2

THE PRACTICE CLASS OF DRUM JAZZ

- - GRAND PRIX RÉÉDITION DU HOT CLUB DE FRANCE

THE PRACTICE CLASS OF DRUM JAZZ

This is one of the most “cult” experimental records in the entire history of jazz. Jo Jones, an immense drummer—a pioneering reformer with peerless technique—here gives us a complete demonstration of his art. CD 1 is devoted to drumming technique while CD 2 focuses on the great historical drummers in classical jazz.

First released as two separate vinyl records in 1974, these titles were digitized, restored and reassembled in 2002 by Laurent Verdeaux, who also proposed extended versions.

This is a vital set: it improves the quality of the listening-experience and increases the historic experimental value while enhancing the quality of the music. Drum-records, of course, but not just for drummers, whether they are amateurs or experts: this set is just as much for musicians, jazz fans, music historians and beat makers of all kinds.

Augustin BONDOUX & Patrick FRÉMEAUX, 2017

THE QUINTESSENCE (NEW YORK CITY - STOCKHOLM)...

NEW YORK - PARIS (1949-1960)

NEW-YORK - PARIS 1947-1959

NEW YORK - TORONTO - NEWPORT 1951-1960

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Warm Up SoloJo JonesJo Jones00:01:361973

-

2Basics-Gadgets-EffectsJo JonesJo Jones00:07:351973

-

3Rudiments Drum Roll-Flams-Single StrokeJo JonesJo Jones00:04:431973

-

4Rim Shots - Tom TomJo JonesJo Jones00:05:311973

-

5Home PractisJo JonesJo Jones00:01:081973

-

6Two Beat - Four Beat - Three BeatJo JonesJo Jones00:05:561973

-

7Drum Solo N °1Jo JonesJo Jones00:03:051973

-

8AccompanimentJo JonesJo Jones00:04:231973

-

9Latin RhythmsJo JonesJo Jones00:01:361973

-

10Rock N'Roll RhythmsJo JonesJo Jones00:02:081973

-

11Making ChangesJo JonesJo Jones00:04:111973

-

12Drum Solo N°3Jo JonesJo Jones00:06:111973

-

13ColoursJo JonesJo Jones00:07:581973

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Drum Solo N°2Jo JonesJo Jones00:05:411973

-

2Drummers I MetJo JonesJo Jones00:01:261973

-

3Baby DoddsJo JonesJo Jones00:01:061973

-

4JoshJo JonesJo Jones00:01:061973

-

5Unnamed Drumer From Saint-LouisJo JonesJo Jones00:02:031973

-

6Alvin BurroughJo JonesJo Jones00:02:121973

-

7A.G. GodleyJo JonesJo Jones00:02:061973

-

8Gene KrupaJo JonesJo Jones00:01:241973

-

9Big Sid CatlettJo JonesJo Jones00:01:181973

-

10Unnamed And Unplaced DrummerJo JonesJo Jones00:00:341973

-

11Walter JohnsonJo JonesJo Jones00:01:171973

-

12Sonny GreerJo JonesJo Jones00:03:011973

-

13Billy GladstoneJo JonesJo Jones00:03:071973

-

14Manzie CampbellJo JonesJo Jones00:01:381973

-

15Chick WebbJo JonesJo Jones00:02:071973

-

16Baby LovettJo JonesJo Jones00:02:341973

-

17Jo Jones Personal ContributionJo JonesJo Jones00:01:121973

-

18Dancers I MetJo JonesJo Jones00:01:211973

-

19Pete NugentJo JonesJo Jones00:01:591973

-

20Eddie RectorJo JonesJo Jones00:03:251973

-

21Baby LaurenceJo JonesJo Jones00:03:091973

-

22Bill « Bojangles » RobinsonJo JonesJo Jones00:02:501973

-

23CaravanJo JonesDuke Ellington00:07:341969

Fa5672 Jo Jones

THE DRUMS BY JO JONES

LE COURS DÉMONSTRATIF

SUR LA BATTERIE JAZZ

THE HISTORIC AND

LEGENDARY JAZZ

DRUMMING SESSIONS

LISTE DES TITRES

CD 1 : Total time 56’01

Jo Jones, dms. Prob.début février 1973, New York

1 WARM UP SOLO 1’36

2 BASICS-GADGETS-EFFECTS 7’35

3 RUDIMENTS Drum roll-Flams-Single stroke 4’43

4 RIM SHOTS - TOM TOM 5’31

5 HOME PRACTIS 1’08

6 TWO BEAT - FOUR BEAT - THREE BEAT 5’56

7 DRUM SOLO N° 1 3’05

8 ACCOMPANIMENT 4’23

9 LATIN RHYTHMS 1’36

10 ROCK n’ ROLL RHYTHMS 2’08

11 MAKING CHANGES 4’11

12 DRUM SOLO N° 3 6’11

13 COLOURS 7’58

CD 2 : Total time 53’36

Jo Jones, dms. Prob.début février 1973, New York

1 DRUM SOLO N° 2 5’41

2 DRUMMERS I MET : 1’26

3 Baby Dodds 1’06

4 Josh 1’06

5 Unnamed drumer from Saint-Louis 2’03

6 Alvin Burroughs 2’12

7 A.G.Godley 2’06

8 Gene Krupa 1’24

9 Big Sid Catlett 1’18

10 Unnamed and unplaced drummer 0’34

11 Walter Johnson 1’17

12 Sonny Greer 3’01

13 Billy Gladstone 3’07

14 Manzie Campbell 1’38

15 Chick Webb 2’07

16 Baby Lovett 2’34

17 Jo Jones’ personal contribution 1’12

18 DANCERS I MET : 1’21

19 Pete Nugent 1’59

20 Eddie Rector 3’25

21 Baby Laurence 3’09

22 Bill "Bojangles" Robinson 2’50

Milt Buckner, org, Jo Jones, dms. Prob. fin juillet 1969, Biarritz, France

23 CARAVAN (Ellington, Tizol). 7’34

Réalisation : Louis et Claudine Panassié, 1973

Montage, mixage, editing, pré-mastering : DIP MUSIC

Couverture : reproduction de la maquette de Pierre Baulig des 33 t originaux de 1973.

Fabrication et distribution : Frémeaux & Associés

www.fremeaux.com

Direction de collection : Laurent Verdeaux

Direction éditoriale : Augustin Bondoux

Conception éditoriale : Patrick Frémeaux et Claude Colombini

P 1969-1974 – 2001 Jazz Odyssey Records - Frémeaux & Associés cessionnaire 2016

© 2017 Groupe Frémeaux Colombini

THE DRUMS BY JO JONES

La collaboration étroite et jazzistique entre Hugues Panassié et son fils Louis, entre le musicologue-es-jazz et le cinéaste-explorateur, naquit d’une idée de ce dernier et dura cinq ans, de 1969 à la disparition d’Hugues Panassié, fin 1974. Il en sortit d’abord un film extraordinaire, « L’Aventure du Jazz », puis la concrétisation d’un certain nombre de projets d’enregistrement, qui furent publiés en des temps vinyliques, sous le label JAZZ ODYSSEY.

JAZZ ODYSSEY RECORDS se propose de rééditer sous la forme d’albums CD ce catalogue tout à fait hors normes. Les deux premières productions, parues en 2002 sous les références JOCD 01 et JOCD 02, sont consacrées à la bande sonore du film « L’AVENTURE DU JAZZ ».

Le présent double album, première réédition des séances organisées en studio par Louis Panassié, est consacré à ce monument musical que représente l’art de la batterie raconté et illustré par Jo Jones, un des plus grands maîtres en la matière.

Il sera naturellement suivi d’autres publications tirées du même catalogue.

Nous avons intégré dans le présent double album les passages restés inédits (faute de place sur les LP de l’époque) et conservé la formule bilingue du double LP original, selon un livret qui permet de suivre pas à pas les propos du grand drummer.

Quant à la présentation générale de l’ouvrage, elle revenait naturellement, comme en 1973, à Hugues Panassié lui-même, sans qui tout ceci n’aurait jamais pu voir le jour.

Laurent Verdeaux

THE DRUMS BY JO JONES

Ces deux disques ne ressemblent à aucun de ceux qui ont été enregistrés jusqu’à présent : ils présentent un artiste livrant avec autant de générosité que de finesse et de savoir le mécanisme de son métier en même temps que sa personnalité d’homme.

Jo Jones est, dans l’histoire du jazz, l’un des batteurs les plus éminents, les plus sensibles, les plus racés. En plus d’une technique de la batterie absolument parfaite, il connaît comme peu de musiciens de jazz la connaissent, l’histoire de sa musique. Non qu’il l’ait étudiée dans des livres mais, cette histoire, il l’a vécue et, chose plus rare, il a su l’observer. Partout où jouaient des musiciens de valeur, on pouvait voir Jo ones écouter avec la plus grande attention. Partout où avaient lieu des jam sessions, Jo Jones était présent, soit tenant la batterie, soit étudiant minutieusement le jeu de ses collègues. Il a été aux quatre coins des Etats-Unis, s’est familiarisé, depuis son adolescence, avec le style, la personnalité des musiciens les plus divers. Il a tenu la batterie dans toutes sortes d’orchestres, grands et petits, accompagnant chanteurs, danseurs, revues, spectacles de toutes sortes. Sa dizaine d’années dans l’orchestre Count Basie l’ont rendu célèbre. Il est devenu le point de mire d’une foule de batteurs, a influencé, depuis 1937, la plupart d’entre eux. Il a tenu à faire bénéficier les jeunes de son immense expérience et a formé plus qu’aucun autre de nombreux batteurs de talent.

Aussi n’est-il pas étonnant qu’il ait plu à Jo Jones, sur une proposition de Louis Panassié, d’enregistrer tout un album de démonstrations d’un art qu’il possède à fond et dont il a appris le mécanisme, non dans des méthodes, mais d’une manière qui, de nos jours, se perd : la manière artisanale, basée par conséquent sur la tradition.

A présent, on apprend à peu près tout dans des livres, qu’ils soient épais ou minces, illustrés de préférence. En fait, on se coupe de la vie, on se sépare des autres, de ses « semblables », lesquels deviennent de plus en plus dissemblables. C’est aussi, aujourd’hui, le règne du singularisme de l’individu.

Le jazz est à l’opposé d’un tel état d’esprit. C’est essentiellement une musique collective, exigeant par conséquent de la discipline, de l’ordre et de la générosité de la part de chacun. Etant traditionnelle par essence, cette musique a également des règles, non écrites, certes, mais qui n’en existent pas moins. C’est à partir de ces règles que chaque individualité crée à son tour, apportant ainsi sa pierre à l’édifice. Comme le dit Jo Jones, il s’agit moins de jouer for the people que with the people.

Cet enregistrement, chose étonnante, est aussi intéressant pour les profanes que pour les connaisseurs. Car Jo Jones y explique avec une grande clarté ce qui est la base du jeu de batterie mais, d’autre part, il exécute tout exemple de quelque étendue avec un tel swing, une technique si admirable, tirant de ses caisses, de ses cymbales, de ses toms une sonorité si délectable que l’audition de ces enregistrements est un régal pour les connaisseurs.

Ses nombreuses évocations des batteurs aux styles les plus divers, son imitation de quatre des plus grands tap dancers, tout en dénotant les exceptionnels dons d’assimilation de Jo Jones, apportent une grande variété à ces albums. Et sa façon de raconter, son ton, sa voix, font passer chez l’auditeur une vérité qu’on n’a aucune envie de contester. Jo Jones mène son affaire avec souplesse, et la sensibilité de son esprit chasse tout ce qu’une telle démonstration pourrait avoir de sec, faite par un autre que lui.

C’est la vie même qui circule tout au long de ces albums. Jo Jones était probablement le seul batteur à pouvoir mener « l’expérience » à bien.

Hugues Panassié, 1973.

THE DRUM BY JO JONES CD N° 1

Plage 1 : SOLO WARM UP

Mesdames et messieurs, cet enregistrement est une expérience. C’en a été une pour moi et j’espère que c’en sera une pour vous.

Il a toujours régné un certain mystère autour du tambour. Il se trouve que c’est lui le père de tout ce qui est percussions. Il y a beaucoup d’éléments dans les percussions.

Nous commencerons par les bases.

Plage 2 : BASES – ACCESSOIRES - BRUITAGES

Nous avons d’abord la caisse claire (# 1).

De là, nous passons à la grosse caisse (# 2).

De la grosse caisse, nous passons au tom (# 3).

Et, après le tom, nous avons la cymbale (# 4).

Mélangeons le tout et nous obtenons à peu près ceci (# 5) :

Tout dépend du moment et de la façon dont on mélange les sons. Maintenant, nous pouvons y aller et nous enfermer dans la chambre noire : il en sortira quelque chose dans ce genre (# 6).

Mais nous avons également quelques accessoires qui, au fil des années, ont été ajoutés aux instruments de percussion proprement dits. A l’époque du muet, par exemple – je veux parler du cinéma muet -, il fallait jouer les bruitages, savoir imiter le rugissement du lion, le pas des chevaux, le bruit des grillons, les cris d’un enfant, le chant des oiseaux, et j’en passe… J’ai là quelques accessoires, à vous de faire marcher votre imagination… Voilà le camion des pompiers, du temps des chevaux, avec la sirène qui précède la cloche d’alerte : il fallait donc une sirène, mais celle que nous connaissions le mieux était celle que l’on entendait lorsque Black Maria était de sortie.

Comme chacun sait, Black Maria était le panier à salade (#7) ; et juste après, on entendait crier « au voleur » (# 8).

Et quand vous rentriez chez vous tard dans la nuit, bien ennuyé et bien éméché, comment réagissait votre femme ? Elle vous flanquait un bon coup de rouleau à pâtisserie sur le crâne (# 9). Ca, c’était un effet comique (slap stick) très courant et le nom est resté à l’accessoire qui évoque le coup de rouleau à pâtisserie.

Il y avait un tas d’accessoires de ce genre. Celui-ci, que tout le monde connaît sous le nom de woodblock, permettait d’imiter le pas des chevaux (# 10).

Tout ça pour le bruitage.

Un peu d’imagination, maintenant. Imaginez que vous êtes ici dans un night-club où vous entendez ce genre de choses (# 11) : vous vous croirez en Espagne voyez-vous, parce que là-bas ils ont… Allez ! … C’était il y a bien longtemps.

Vous savez comment c’est avec vos habits… vous aviez sur l’écran un type qui déchirait son pantalon – ou un gag du même tonneau –vous utilisiez alors une sorte de crécelle (rachet), à vous de savoir (# 12) suivre le type en train de se baisser (# 13), de faire craquer son pantalon (# 14), de le faire craquer encore (# 15) ; et ça y était, avec une belle fente.

Repartons. Figurez-vous qu’un beau jour, on s’est avisé que, dans état nommé Texas, il y avait quelques vaches : il vous faut naturellement une cloche de vache (cow bell), vous savez bien, celle qui mène le troupeau (# 16) ; bon, pour relever un peu le niveau, voilà comment nous nous en servons (# 17).

Laissons maintenant les bruitages de côté.

J’ai dans la main une paire de baguettes, et vous pouvez vous rendre compte à l’enregistrement que ce sont des baguettes (# 18) à cause de leur son.

Maintenant, je tiens des mailloches, et vous les reconnaissez à leur son (# 19).

Maintenant, j’ai pris des balais, et vous pouvez reconnaître que ce sont des balais (# 20) par leur son. Les balais servent à de nombreux effets (# 21), pour imiter le train, par exemple (# 22), etc.

Pour jouer un air en mineur, vous utiliserez les mailloches (# 23).

Assez sur ce sujet, revenons aux baguettes et voyons comment, avec tous ces outils, nous allons pouvoir installer un bon petit tempo, pas trop difficile à jouer (# 24).

J’oubliais ! On m’a accusé de quelque chose dont je ne pense pas être responsable : avant que d’autres innovations voient le jour, il existait une chose du nom de sock cymbal (cymbale à pied ou cymbale charleston), qui sonne comme ceci, et je serais inexcusable de ne pas faire entendre ma marque de fabrique (# 25). Mélangeons maintenant tout cela (# 26). Bien !

Une chose importante : nous ne sommes pas tous bâtis sur le même modèle et n’avons pas tous la même façon de voir les choses, les uns étant naturellement doués et les autres devant travailler pour faire fructifier leurs dons, tout en conservant leur personnalité propre.

On s’est donc mis d’accord depuis longtemps pour établir ce qu’on a appelé les éléments de base de la batterie.

Plage 3 : RUDIMENTS : Roulement – Flams – Single stroke

Le premier des éléments de base est, comme vous le savez, le roulement de tambour ; de là, vous passez au flam ; et du flam, au single stroke. Ce sont là les trois éléments essentiels, aussi importants que les horaires des chemins de fer !

La première chose est donc d’essayer de faire un roulement de tambour, j’ai bien dit : essayer (# 27). Maintenant, essayer d’exécuter le flam : le flam doit sonner comme si vous disiez « plum » (# 28), chaque baguette frappant alternativement la caisse juste une fraction de seconde avant l’autre. Passons maintenant au single stroke, c’est-à-dire un seul coup par l’une ou l’autre main en alternance : vous commencez par votre main gauche et passez à la droite, et puis vous alternez (# 29).

Je reprends au début : les premières tentatives de single stroke ne ressemblent à rien ; mais à partir du moment où vous l’avez en main et commencez à bien l’exécuter, ça finit par prendre toute sa valeur, voyez plutôt (#30).

Même chose pour le flam, c’est très facile (#31).

Même chose avec le roulement. Les termes varient, mais il n’y a qu’un seul roulement de tambour, choisissez les mots que vous voudrez, quitte en fin de compte à appeler ça un roulement de tambour. Je démarre sur l’extérieur (# 32) : tout dépend de la pression que vous exercez, du tempo que vous sentez et de votre propre maîtrise.

Voilà donc les trois choses essentielles. Mettons maintenant tout ça ensemble, autant que possible (# 33). Bien ! Ça va ! Mais vous devez apprendre à garder en permanence le contrôle de tout cela. Je vais commencer par une pulsation simple, sur la cymbale, la caisse claire, la charleston et la grosse caisse, comme ceci (# 34).

Plage 4 : RIM SHOTS – TOM

Vous avez entendu parler des rim shots.

Eh bien il y a plusieurs manières d’exécuter un rim shot. Vous pouvez le faire comme ceci (# 35) ; vous pouvez aussi le faire comme cela (# 36), mais ce n’est plus alors à proprement parler un rim shot ; il s’agit des baguettes tenues l’une au-dessus de l’autre. Il est possible que vous manquiez de technique (# 37) pour exécuter ceci (# 38), ou que la musique aille trop vite et échappe à votre contrôle (# 39) ; mais si vous apprenez à poser votre baguette au plus près de celle qui doit être normalement dans votre main gauche (# 40), vous obtenez un son qui vient d’un autre son. Le son que vous entendez là (# 41) n’est pas le même que celui-ci (# 42) parce que, dans ce cas, la caisse peut résonner. Autrement, en faisant pression sur la baguette, (# 43) le son sort amorti.

Voyons maintenant ce qu’on peut faire avec le tom.

Le tom est un instrument bien à part. Nous utiliserons un battement simple, ce genre de chose que tout un chacun peut suivre, inutile de faire des fantaisies comme ceci (# 44). Vous remarquerez que j’ai essayé de faire le single stroke, que j’ai essayé de rouler sur le tom, que j’ai essayé de faire le flam sur le tom, comme (# 45) je le fais (# 46) ici, mais vous observerez que la qualité du son change et donne autre chose au fur et à mesure.

Voyons maintenant ce que nous pouvons faire en mélangeant tout cela. Je vais penser à un morceau imaginaire et voir comment faire mon mélange en passant de la caisse claire au tom et en me servant de la cymbale (# 47). Je me suis permis une petite fantaisie à la fin (# 48) parce que je pensais à un tas de choses à la fois, à des gens que j’avais connus, et c’est venu machinalement. L’expérience vous apprendra que ce sont les gens que vous rencontrez qui vous font jouer. Vous êtes comme une éponge, vous vous imbibez de tout ce qui vous entoure, mais, une fois que vous possédez bien les bases vous permettant de connaître les choses à fond, alors vous pouvez faire tout ce que vous voulez, en toute liberté, comme ceci (# 49).

Voici ce que je viens de faire : j’ai joué sur le petit tom et sur le grand tom pour obtenir des effets sonores différents. Mais vous pouvez conserver la pulsation de base pour n’importe quelle structure dans laquelle vous êtes parti, par exemple, je peux démarrer sur le petit tom en jouant ceci (# 50). Vous remarquerez qu’à la fin, j’étais sur la caisse claire : si vous jouez sur les toms et que vous voulez passer sur la caisse claire, il faut apprendre à le faire (# 51) ; impossible à faire avec le timbre de la caisse claire, il faut le neutraliser (# 52) et elle prendra une sonorité de tom ; en d’autres termes, ça ne sonnera pas (# 53) aussi profond qu’avec votre tom de droite (# 54), ni aussi profond qu’avec celui qui est devant vous, mais ce sera cohérent ; par exemple (# 55) et en mélangeant (# 56) ; vous découvrirez ainsi les ressources sonores de la batterie.

Plage 5 : TRAVAILLER CHEZ SOI

Maintenant, il ne faut pas qu’on vous raconte des blagues : la batterie est bien plus musicale que n’importe quel autre instrument parce qu’on peut faire un tas de choses avec, et il faut absolument apprendre à jouer tous les bruitages.

Quand on a fait ses classes avec un bon professeur (et d’habitude tous ceux qui donnent des cours sauront vous apprendre à jouer), c’est un vrai plaisir, même si on ne joue pas pour gagner sa vie. On se procure une batterie, on s’installe dans une petite chambre insonorisée parce qu’il ne faut pas faire peur aux voisins, on met un disque et on joue un accompagnement, ou bien on invite quelqu’un de la famille qui connaît la musique, ou des amis, et c’est un vrai bonheur, une détente, de pouvoir s’asseoir en rentrant du travail, après un bon dîner, un peu de repos, et on commence à jouer quelque chose comme ça (# 57).

Tout le monde peut parvenir à ce niveau, et vous pouvez vous mettre à jouer vos propres lignes mélodiques.

Plage 6 : DEUX TEMPS – QUATRE TEMPS – TROIS TEMPS

Voici maintenant quelque chose de très simple qu’il faut toujours garder en mémoire.

Il y a trois pulsations… trois mesures de base. On les appelle le C-barré qui est en 4/4 ou plutôt le C devrais-je dire car le C-barré est en 2/4. Et il y a le 3/4, mais comme j’ai déjà dit, avec ces trois là, quand on les démultiplie, qu’on en rajoute, qu’on en retranche, on peut arriver à 9/8, 9/3, 6/2, que sais-je ?… à du 7/4 et à un tas de rythmes différents, mais il nous faut bien commencer par les rythmes de base.

Commençons par les coups simples 1, 2, 3, 4, des coups aussi simples que ceci : (# 58).

Même principe maintenant, seul le nom change. On va jouer en C-barré, c’est-à-dire en 2/4, et c’est très simple : (# 59).

Passons maintenant à autre chose de très simple : la valse. Trois coups à la mesure, très simple, et d’un abord très facile, en frappant un coup sur la grosse caisse et deux coups sur la caisse claire. Comme ceci : (# 59).

On peut très bien ne pas en rester là et faire (# 60) On n’est pas obligé de le faire comme cela, mais aussi comme ceci : (# 61) en tenant un tempo régulier à la grosse caisse.

On peut peut-être y rajouter la cymbale charleston, en accentuant le coup sur la grosse caisse comme ceci (# 62) :

Maintenant avec les trois pulsations dont je viens de parler, voyez comme c’est facile de marquer un tempo régulier à la grosse caisse : on peut jouer l’une aussi bien que les autres, et j’ai dit 4/4, 2/4 et 3/4, n’est-ce pas ?

On joue le 4/4 : (# 63), le 2/4 : (# 64), et la grosse caisse continue régulièrement.

Ce n’est pas très difficile de jouer à différents tempos, et on peut accélérer le mouvement, ou le ralentir. En un mot, c’est une question de vitesse dont vous avez toujours la maîtrise.

Maintenant passons aux différentes valses que je dois évoquer, car vous avez différentes sortes de valses, vous avez la valse viennoise, comme ceci : (# 65).

A un stade plus avancé de vos études vous en arriverez à l’utiliser, et vous découvrirez alors qu’en jouant : (# 66), vous devriez plutôt jouer : (# 67).

Je vais maintenant jouer la même chose : je vais jouer cette valse, mais d’une main seulement : c’est la main gauche que vous entendrez (# 68) :

Tout cela est très simple. Plus tard, je vous montrerai comment on peut combiner tous ces éléments pour les jouer en même temps, et vous aurez le choix de votre tempo, de votre allure, mais ces trois éléments de base sont ceux qu’il vous faudra assimiler si vous voulez jouer dans l’esprit de l’orchestre de danse.

Plage 7 : Maintenant une chose très facile à jouer SOLO DE BATTERIE N°1

Plage 8 : ACCOMPAGNER

Ce chapitre est l’un des plus difficiles à illustrer, mais je vais essayer. Les choses changent selon qu’il s’agit de la trompette ou du saxophone.

Très simple et très facile : je ne vais pas m’étendre sur cet élément en particulier, mais vous allez voir comment ça marche.

Ça semble tout bête : c’est une ligne mélodique et tout le monde pense s’y reconnaître, dans des rythmes variés qu’on appelle « latino-américains », ou encore « afro-cubains », ou encore autrement.

Dans ce qui va venir, je vais essayer de donner une illustration, même si je joue d’habitude en grand orchestre, plutôt qu’en trio, quartette, quintette ou sextet.

Les choses varient beaucoup en fonction des différents instruments ou des différents musiciens en présence, et il vous faut apprendre à utiliser votre matériel selon les différents partenaires avec qui vous jouez, parce qu’on ne peut pas jouer, comme je vais essayer de vous le montrer, on ne peut pas jouer de cette cymbale en accompagnant un saxo comme on le ferait en accompagnant un trombone ou une trompette. Je vais frapper la cymbale à nouveau (# 69), et là le son est différent. Tout dépend de votre façon de le jouer. Je vais frapper ces trois mêmes cymbales, je vais les frapper une fois (# 70). Maintenant je les frappe à nouveau (# 71), mais j’utilise une technique différente : une autre méthode pour frapper ces cymbales, dans le but d’avoir un son différent. On intègre des effets particuliers dans la percussion parce qu’on joue pour trois individus différents, et c’est une chose très importante à savoir. Quand on accompagne, il faut toujours avoir en tête qu’il s’agit ici d’un saxophoniste, ou là d’un trompettiste, ou encore là d’un tromboniste.

Tout dépend de la personne pour qui vous jouez, et il vous faut apprendre à découvrir si vous ferez mieux de jouer ceci (# 72), ou cela (# 73), ou encore quelque chose de différent, parce que le trompettiste préfèrerait entendre ceci (# 74), ou plutôt cela (# 75).

S’il s’agit du saxophoniste, il aimerait peut-être entendre ceci (# 76) plutôt que ce coup de cymbale (# 77). C’est à vous d’en faire votre affaire. Et maintenant, voilà ce qu’on va avoir à faire : on vous dira peut-être : « Donne moi un rythme latino-américain, comme ceci ! » (# 78) ou bien comme ça (# 79). Et vous, vous allez le jouer comme ceci (# 80), ou comme cela (# 81) : tout dépend des circonstances et u contexte. Tout dépend de l’ambiance créée par le morceau, ou du tempo, ou de l’individu avec qui vous jouez. Vous pouvez jouer pour l’auditoire, mais il vous faut tenir compte des musiciens qui sont sur scène.

Plage 9 : RYTHMES LATINS

Pour mémoire, je vais essayer… je vais tenter de jouer quelques rythmes de base, des rythmes qu’on appelle « rumba », que nous appelons « afro-cubains », et autres.

On a tendance à donner un nom à tous ces trucs différents, mais sans aller voir sur place, on ne peut pas connaître les vraies appellations. Par erreur, on les baptise de travers. Alors on dit… par exemple, commençons par le rythme de base de la bossa-nova (# 82) …mais je ne vais pas commencer comme ça. Je vais commencer par le fondement : (# 83). OK ? Allez, voilà qui est fait. Fondamentalement, c’est comme ça.

Plage 10 : RYTHME ROCK AND ROLL

Bon, on me dit : “Que pensez-vous du rock’n’roll ?” et je réponds : « Je n’en sais rien ». Il y a des choses qui… qu’on appelait autrement. Je vais essayer de donner les éléments de base. Au commencement, on recherchait un contretemps : (# 84). Voilà ce qu’on a fait : (# 85). Puis on a enjolivé : (# 86). Ensuite… ensuite on a joué rapide : (# 87). Bon, tout ce qu’il y avait à faire, c’était : (# 88). On fait des petites fioritures parce que, voyez-vous, quelqu’un veut qu’elles soient jouées (# 89). Alors pour essayer de les placer, avec les différents arrangements de chaque groupe, on tâche de mettre ce genre de truc noir sur blanc, parce que ça ne correspond pas aux phrases habituelles de 32, ou 36, ou 12 mesures, ou à la forme du blues ou à quelque chose de semblable : on y met des ajouts, ou des arrêts prolongés ou n’importe quoi. Quand c’est écrit, vous pouvez les jouer.

Plage 11 : CHANGEMENTS DE MAIN

Plus tôt, j’ai parlé des baguettes, des mailloches et des balais.

Beaucoup de batteurs, beaucoup d’entre nous, avons ce problème du passage des baguettes (# 90) aux mailloches (# 91) et aux balais (# 92). Je vais essayer de vous montrer comment on fait. Sans trop me préoccuper du rythme que je choisis, je vais essayer de ne pas changer l’ambiance du tempo dans lequel je joue.

Je vais donc essayer d’interpréter un air imaginaire, et vous verrez que je ferai tous les changements en essayant de garder le tempo immuable dans la mesure de mes moyens (# 93).

Plage 12 :

Je vais maintenant essayer de jouer des extraits de trois solos de batterie différents, tout en suivant la ligne mélodique SOLO DE BATTERIE N°3.

.

Plage 13 : COULEURS

Une fois qu’on a appris la batterie, le plus difficile n’est pas de jouer pour les gens, mais de jouer avec les gens. Ayant eu l’expérience du grand orchestre, je vais d’abord jouer quelque chose en imaginant que j’accompagne tel arrangement parmi ceux que je jouais, et ce sera ainsi très simple (# 94). Comme vous l’avez peut-être deviné, i s’agit d’un passage de morceau genre Jumpin’ at the Woodside, où j’ai strictement conservé le tempo, tout en participant aux ensembles et en accompagnant les solistes ; et, pour aller d’un solo à l’autre, qu’il s’agisse du trombone, de la trompette ou du saxophone, il faut avoir la notion de relation. Les rapports de relation s’établissent selon ce que vous sentez et jouez. Par exemple, vous battez le tempo régulier pour un morceau déterminé : lorsque vous passez d’une partie à une autre, il vous faut savoir mettre la couleur appropriée. En d’autres termes, si vous jouez derrière la trompette comme ceci : (# 95), et que, subitement arrive un saxophone, vous allez dans l’instant adapter votre jeu pour le saxophone (# 96). C’est ce qu’on appelle donner la couleur

Puis le saxo laisse la place au trombone : même chose.

Je vais commencer par la trompette, puis le saxophone, puis le trombone, et à chaque fois vous observerez un jeu individualisé, comme ceci : (# 97).

Vous remarquerez que j’utilise trois cymbales : en voilà une (# 98), une autre (# 99), une autre encore (# 100). Maintenant, notez bien qu’ici, c’est la trompette (# 101), ici le saxophone (# 102). Là, du saxophone au trombone (# 103), et vous remarquerez que chacune de ces cymbales possède un son différent (# 104, # 105). Et nous en arrivons à l’ensemble, où on est amené à incorporer toutes ces formes, ce qui donne ceci (# 106).

Et nous voilà avec tous ces rythmes entremêlés, mais nous commencerons par quelque chose de simple, la pulsation de base ; commencez toujours par les fondamentaux et vous ne vous tromperez jamais, parce que c’est à partir de là qu’on peut enrichir, comme ceci (# 107). Je vais donc commencer par le 4/4 régulier et de là j’irai à différentes figures rythmiques, et vous pourrez suivre au fur et à mesure (# 108).

Evidemment, tout ça sonne un peu comme de l’hébreu, mais ces petites choses simples une fois réunies et bien analysées, le privilège vous reviendra de les embellir. Alors, saisissez-vous-en et allez-y pour votre propre compte ; partagez votre créativité et votre imagination avec ceux qui jouent avec vous, servez-vous de tous ces rythmes de base que vous aurez étudiés à fond, ayez bien le contrôle de votre instrument et vous pourrez faire tout ce que vous souhaitez faire.

Et peu importe comment on appellera ça : VOUS JOUEZ !

THE DRUMS BY JO JONES CD N° 2

7 : SOLO DE BATTERIE N°2

Plage 2 : LES BATTEURS QUE J’AI RENCONTRES

Je vais maintenant essayer d’esquisser le portrait des batteurs que j’ai rencontrés au cours de ma vie, et, pour commencer, j’évoquerai des batteurs dont vous n’avez jamais entendu parler, d’autres que vous connaissez, et ainsi de suite.

Je commencerai par Manzie Campbell, A.G.Godley, Big Sid Catlett, je parlerai aussi de Mr Billy Gladstone, je parlerai aussi d’un certain Josh, enfin il y en a trop pour les citer tous. Au fur et à mesure, je ferai de mon mieux pour reproduire les traits les plus caractéristiques de chacun, ceux qui ont fait leur réputation.

Au premier rang, Mr Manzie Campbell, qui faisait partie des Spectacles Silas Green et était sans aucun doute, dans un contexte particulier, le plus grand batteur du monde. Puis j’évoquerai Mr A.G.Godley, puis Alvin Burroughs, puis un certain Mr Billy Gladstone.

Plage 3 : Baby Dodds

Je n’oublierai pas Baby Dodds. Je pense que le mieux est de commencer le parcours par une chose qu’on appelait le shimmy. Voici donc le shimmy de Baby Dodds (# 109).

Plage 4 : Josh

Josh était un batteur de Kansas City qui jouait uniquement sur la caisse claire. Il était de toutes nos jam sessions avec Hot Lips Page, Herschel Evans… Lester Young… Walter Page, Basie… Pete Johnson… aucune importance, il vous faisait swinguer ! Voici comment il s’y prenait (# 110) … voici Josh, observez …

Plage 5 : Un batteur anonyme

Il y avait un autre batteur, à Saint Louis (Jo Jones n’a pas voulu révéler sa véritable identité) qui jouait comme ceci et vous swinguait tout l’orchestre de cette manière (# 111). C’est un petit échantillon de baguettes croisées, une variation en baguettes croisées, c’est très facile. Je vais vous montrer comment il développait là-dessus, il faut dire qu’il n’avait pas de charleston – à l’époque, j’étais le seul traîne-lattes à en avoir une – et comme il faisait tout sur la caisse claire, je vais ôter mon pied de la caisse claire (lapsus : Jo Jones a voulu dire « cymbale charleston » et non « caisse claire ») et essayer de vous montrer le mieux possible comment, juste avec la caisse claire, il était capable de jammer ou de tenir sa place, comme ceci, dans un orchestre de quatorze musiciens, et avec douze chorus girls devant par dessus le marché (# 112) :

Plage 6 : Alvin Burroughs

Avant de passer à A.G.Godley, qui savait tout faire, voici Alvin Burroughs, spécialiste du tom – en tout cas c’est ce que je croyais !

Mais en fait, Alvin Burroughs était l’homme de la cymbale. Le mieux est que je vous dise comment il s’y prenait : il plaçait une pièce de monnaie dans sa main, et la cymbale sonnait comme ceci (# 113). Malheureusement, là je me suis servi d’une baguette, laissez moi un instant et je vais vous faire voir : voici (# 114).

C’est tout simple quand vous avez la technique qu’il faut, mais il avait, pour faire ça, une manière très intrigante de cacher cette pièce entre le pouce et l’index ; résultat, personne n’y comprenait rien mais tout le monde recherchait ce son-là. C’est comme ça qu’on s’est mis à utiliser la cymbale cloutée, pour retrouver le son d’Alvin Burroughs. Lui il pouvait faire ça même avec une baguette (# 115).

Et Alvin Burroughs m’a demandé : « As-tu déjà brûlé le dur ? » - « Qu’est-ce que ça peut bien avoir à faire avec la batterie ? » - Il dit : « Il te faut apprendre à faire le train !». Je lui demandai : « C’est quoi, le train ? ».

Alors il s’est assis à sa batterie et m’a dit : « Viens par là, jeune homme, que je te fasse voir ce que c’est que le train ».

Plage 7 : A.G. Godley

Mr A.G.Godley fit exactement la même chose et prit le temps de me montrer comment faire le train. C’était du temps des locomotives à vapeur. Bref, le train disait à peu près ceci (# 116) :

Je crois que j’peux - Je crois que j’peux - Je crois que j’peux

Je crois que j’peux - Je crois que j’peux - Je crois que j’peux

Je crois que j’peux - Je crois que j’peux - Je crois que j’peux

J’ai donc bien vu la chose, mais il avait sa manière bien à lui : je vais vous montrer comment Mr Godley faisait (# 117). Pendant qu’on y est, je vais vous montrer comment ça se passait, je ne veux pas dire qu’il jouait des deux, quatre ou huit mesures, l’orchestre était bien là (# 118) ; et quelque part dans le développement, je vais de nouveau partir sur ce rythme et montrer comment A.G.Godley l’intégrait (# 119), s’orientant de sorte de coller à ce qui se passait et toujours en prenant sa place dans l’arrangement, et tout se mettait à tanguer. Et, au moment de la pause, pendant le quart d’heure de repos de l’orchestre, c’est le premier batteur que j’ai jamais vu rester sur scène, au concert comme au dancing, tout seul avec sa batteri, et jouer tout simplement ceci (# 120).

Plage 8 : Gene Krupa

Nous arrivons maintenant aux temps modernes, et il y avait dans le secteur un type qui avait étudié pour devenir prêtre. Il ne jouait qu’une sorte de rythme, un rythme très simple ; vous le connaissez, c’est Gene Krupa. Il ne faisait que ceci (# 121) ; par la suite, quand il est entré dans l’orchestre de Benny Goodman, c’est devenu un morceau intitulé Sing Sing Sing.

Il avait joué auparavant dans plusieurs groupes qui étaient fous de ce boum-boum-boum, mais maintenant, il était chez Benny Goodman avec un arrangement rien que pour lui, et quelle intensité dans cette pulsation continue et massive… et en plus, il ne vous étouffait pas avec, il se contentait de jouer (# 122).

C’est très simple, comme rythme, il ne compliquait pas, non pas que je le soupçonne de ne pas savoir faire des choses compliquées, mais nous recherchons toujours la simplicité, et ça, vous l’avez remarqué à travers les différents batteurs dont j’ai parlé.

Plage 9 : Big Sid Catlett

Voilà maintenant mon cher ami Sid Catlett. Voici ce qu’il faisait avec les mailloches. C’est très difficile, les mailloches, personnellement, je n’ai jamais pu m’en servir comme lui, parce que je les tiens d’une manière très orthodoxe, et il faut que je change tout ça pour essayer de jouer comme Mr Sid Catlett (# 123). Là, je ne suis allé que de la caisse claire au petit tom, mais on peut améliorer les choses : en conservant la même structure, je vais recommencer, toujours en partant de la caisse claire (# 124).

Plage 10 : Un batteur anonyme et atypique

Au passage, voici un type (Jo Jones n’a pas voulu révéler sa véritable identité) qui n’a jamais pris un seul solo, qui n’a jamais fait autre chose que de jouer le tempo régulier – et on pouvait se reposer sur lui.

Voici comment il jouait, juste le tempo, comme ceci (# 125) ; mais il pouvait swinguer à en rendre tout un orchestre malade !

Plage 11 : Walter Johnson

J’en arrive maintenant à Monsieur Drums, qui, heureusement, vit toujours (nous sommes en 1973, NdT). Il utilisait à la fois un balai et une baguette dans la main : Mr Walter Johnson. Je l’appelle le Guy Lombardo de la batterie. Les choses qu’il faisait avec une baguette et un balai (# 126) !

Non qu’il ne fût capable d’enjoliver cela, mais pour certains ensembles quand il était chez Fletcher Henderson, il faisait ça, avec un balai et une baguette ; et il m’intriguait beaucoup, parce que tout ce qui touchait à la batterie m’intéressait, alors je l’observais, je continue d’ailleurs à le faire et je l’appelle Monsieur Drums. La façon dont il fait ça (# 127) !

Plage 12 : Sonny Greer

Après Monsieur Drums, le seul styliste de la batterie était un jeune type qui, pour moi, était l’Empire State Building – un monument ! Il avait une approche de la batterie fort peu orthodoxe, c’était une autre époque en matière d’effets, et une conception particulière des cymbales. J’ai nommé Mr Sonny Greer.

Je vais vous montrer, avec les cymbales dont je dispose et en les frappant une première fois, puis je les frapperai à la manière de Mr Greer (# 128) ; maintenant, voilà le son qu’obtenait Mr Greer (#129) ; ce sont les trois mêmes cymbales, mais le son est différent.

Il jouait aussi de manière orthodoxe, du fait de ce qu’il avait à faire chez Mr Ellington, où on innovait, où on jouait de la musique créative. Et une façon de vivre ça, aussi, quand il jouait ce genre de chose, on le reconnaissait tout de suite, c’est sa marque de fabrique, à Mr « Empire State Building » Sonny Greer (# 130) ; pour me faire bien comprendre, je vais essayer de jouer le contexte et de vous montrer ce qui en sort, comme ceci. Voici ce qu’il joue (# 131).

Vous remarquerez en passant que les batteurs de rock actuels essayent de jouer de cette façon (# 132) : Je suis incapable de comprendre pourquoi ils présentent comme une nouveauté ce qui se faisait bien avant eux !

Enfin, ce n’est de ma part qu’une hypothèse : expliquez l’alphabet à un enfant et il s’imaginera qu’il a été inventé juste pour lui ! N’oubliez pas qu’il n’y a rien de nouveau sous le soleil.

Plage 13 : Billy Gladstone

Nous abordons maintenant un domaine très peu connu, du fait que très peu de gens ont pris la peine de s’intéresser à Mr Billy Gladstone.

Il faut vous dire qu’une des choses les plus difficiles à faire est ce qu’on appelle le « four stroke roll », c’est à dire : (# 133). Voilà, c’est bien (# 134) ! Maintenant, faisons la même chose d’une main (# 135), puis des deux mains (# 136). Je ne sais pas si vous pouvez vous rendre compte si je joue avec une main ou les deux.

Je vais jouer ce rythme complexe que tous les percussionnistes d’orchestres symphonique du monde ont tant de mal à exécuter depuis qu’on a essayé d’y introduire le tambour. Ca a commencé en Allemagne : on a fini par y intégrer les timbales, puis le tambour, alors qu’ils n’y avaient pas leur place : on les utilisait pour les parades ou les musiques de ce genre (# 137).

Maintenant, je vais jouer avec une seule baguette (# 138); en d’autres termes, vous voilà en train de jouer dans une parade (# 139).

Mr Billy Gladstone était un très grand musicien, et sans lui, Radio-City, dont il faisait répéter l’orchestre, n’aurait pas existé. Question percussions, il connaissait tout. Plus tard dans sa vie, il est devenu capable de réparer n’importe quoi, il a même fabriqué un piano de ses mains !

Sur le tard, il travaillait avec « My Fair Lady » et l’élément plus marquant de la troupe était Mr Billy Gladstone, le plus grand des batteurs… les spectacles avaient de l’allure et n’importe où, à Boston ou à Saint Louis, tout le monde cherchait d’abord à rencontrer Billy Gladstone, les autres vedettes passaient après, il n’y avait rien à faire, tout le monde voulait voir Billy. Etait-il en ville, on n’invitait pas les stars ou tous ces gens fabuleux à sortir : on voulait Billy Gladstone. Mais lui était occupé ailleurs à réparer des pianos ou à bricoler…

C’était le plus honoré des hommes, et je me suis dit que jamais je n’arriverai à jouer de la batterie comme ça, alors j’ai laissé tomber.

Plage 14 : Manzie Campbell

Tout ça m’amène à Mr Manzie Campbell qui, avec une seule baguette, pouvait rouler sur un simple tambour pendant des kilomètres. A l’époque, j’en étais encore à m’essayer sur un tambour comme un chien gratte par terre (# 140), et mon plus beau roulement (# 141) ne valait même pas un rouleau de printemps au restaurant chinois.

Cet homme-là, quand il roulait, c’était comme du papier de soie (# 142). Dommage que vous ne puissiez pas voir sur le disque ce que je faisais : en prévision de ce roulement, je levais une main à la hauteur de l’autre ; je recommence (# 143).

Lorsque vous êtes capable de partir de l’une ou l’autre baguette, gauche ou droite, et de maintenir un roulement régulier et constant, sans un accroc, alors là, vous y êtes. Là, je n’y arrive pas trop bien parce que je manque de pratique, mais, en gros, c’est ça.

Plage 15 : Chick Webb

J’ai connu Mr Chick Webb et, les gens étant ce qu’ils sont, on m’a souvent demandé d’essayer de l’évoquer ; eh bien, tout ce que je peux faire pour entrer dans son jeu est une petite chose… je suis limité, parce que je ne suis pas équipé pour ça, mais je me souviens comment il prenait un solo, comme dans Harlem Congo si vous avez le disque, il jouait comme ceci, je vais essayer : (# 144); et il faisait quelque chose que personne n’est encore parvenu à attraper, quelque chose comme ceci (# 145) ; et alors, il terminait par un trait tout simple, c’est ce qu’il disait (# 146) ; bon, c’est une manière de conclure qui a l’air toute simple, mais j’aurais bien voulu vous y voir…

Cet homme-là était bossu, mais il a dominé ce handicap et l’a retourné à son avantage. Sur le terrain musical, on rencontre beaucoup de gens qui ont eu des problèmes physiques qu’ils ont su dominer, voyez Art Tatum, George Shearing ou Harry Bloom, etc.

Plage 16 : Baby Lovett

Je voudrais maintenant essayer d’évoquer un batteur que personne n’est parvenu à capter. J’y tiens car, parmi tous les batteurs dont j’ai parlé jusqu’ici, il est de ceux qui vivent encore. Il s’appelle Baby Lovett, il vit à Kansas City et il est en pleine activité (nous sommes en 1973, NdT). J’espère bien après cet enregistrement prendre quelques jours pour aller lui rendre visite.

Mr Baby Lovett est le seul bel homme que j’ai jamais vu derrière une batterie. Mais il peut faire un tas de choses avec, il peut expliquer, il peut vous jouer tous les rythmes qui vous passent par la tête, il peut enseigner, il sait tout faire.

Tout ça sans jamais se servir de la cymbale charleston : simplement, il est là, derrière ses caisses, pour une petite chose très simple, et il est un peu là, et cette petite chose-là, on l’appelle press roll (roulement très serré et prolongé). Quand il part dans le press roll, c’est à en perdre la raison, quelque chose comme ceci (# 147).

Mais pour jouer comme Baby Lovett, il faut l’avoir vu faire : il joue d’un côté puis de l’autre, il joue sur le devant puis sur l’arrière, en d’autres termes, quand il joue ceci (# 148) il va depuis le fond de la caisse sur le devant, puis sur la droite, puis sur la gauche, et alors il fait tout exploser, ses caisses, ses baguettes, tout son corps, et sans bouger plus que ça, juste les épaules (# 149); et tout ça en conservant la même pulsation (# 150) : vous voyez, ça, c’est fondamental, il y a un moreau et un tempo, et c’est relativement facile pour nous d’y arriver.

Plage 17 : Jo Jones en personne

Je me vois maintenant obligé d’ajouter quelques mots et de parler de moi-même. J’ai ma propre marque de fabrique, et j’utilise un tom sur ma gauche et un sur ma droite. Maintenant, que je joue sur ma droite ou sur ma gauche (# 151), que je croise les mains (# 152) ce n’est qu’un battement symphonique comme on en faisait déjà en 1909, et c’est très bien comme ça. Quoi que je joue (# 153), l’exécution doit être conforme à ce qu’elle représente.

Je vais juste encore ajouter ceci (# 154), qui représente mon apport personnel à la musique pour ce qui est de la batterie. Quand vous aurez mis bout à bout tous ceux dont j’ai parlé plus tous ceux dont je n’ai pas parlé, alors vous réaliserez combien est vaste le terrain à labourer – si vous êtes un vrai cultivateur.

Plage 18 : LES DANSEURS QUE J’AI RENCONTRES

Je vais essayer maintenant de faire entrer ma vie personnelle en ligne de compte, pour cette bonne raison qu’on a dit de moi bien à tort que j’étais un tap dancer. Dans ce bas monde, nous subissons l’influence d’un tas de choses et d’un tas de gens. Comme je l’ai déjà dit, nous sommes influencés par notre entourage, par les gens que nous fréquentons. Il nous faut aussi avoir une imagination fertile, mais jamais l’imagination ne remplacera l’expérience, l’expérience est fondée sur des erreurs et pour ma part, j’en ai fait un paquet. Parlons des influences : j’ai été influencé par les danseurs que je voyais dans les carnavals et les manifestations du même genre. Quelques-uns sortaient du lot et c’est à ce moment-là, pendant une période assez courte de ma vie, que j’ai fréquenté des danseurs dont quelques-uns me viennent à l’esprit, comme Pete The Tapper, c’est-à-dire Pete Nugent ; je crois qu’on peut ajouter Mr Eddie Rector, je crois qu’on peut parler de Mr Baby Laurence, et, au-dessus de tous, de Mr Bill « Bojangles » Robinson.

Plage 19 : Pete The Tapper

D’abord, Pete The Tapper (# 155). Voilà pour Pete (Le surnom de Pete Nugent lui vient du manipulateur des télégraphistes, et du bruit que faisait son utilisation, NdT).

Plage 20 : Eddie Rector

Mr Eddie Rector. On s’est aperçu des années plus tard qu’avant d’entrer en scène, il répandait du sel sur le plancher. C’étaient de vieux parquets, très glissants et dangereux, à cette époque-là.

Et c’est ainsi qu’il inventa une danse appelée « Le Sable ». Il tomba malade et perdit la vue quelque temps, et beaucoup de gens firent leur profit de cette danse. Mais Mr Eddie Rector guérit, revint sur scène et mit tout le monde d’accord. Voici comment Mr Eddie Rector dansait « Le Sable ». Je vais faire une petite introduction et je tâcherai de me souvenir d’une partie de son numéro (# 156).

Plage 21 : Baby Laurence

Voici maintenant un chanteur : Baby Laurence. Celui-là, personne ne se doutait qu’il savait danser, et puis le voilà qui s’amène avec des idées toutes neuves, si neuves qu’au début, personne ne comprenait bien ce qu’il faisait. Mais il a percé, et je vais vous imiter Mr Baby Laurence et ses pas subtils. J’ai une introduction à faire d’abord (# 157).

Mr Baby Laurence fut un grand innovateur et a élevé le niveau de la danse par une imagination et une façon de la vivre que personne n’a jamais surpassé.

Plage 22 : Bill “Bojangles” Robinson

Venons-en maintenant au Maitre. Le maître de ce qu’on a appelé le « buck and wing », la danse à claquettes. Il s’agit d’un type du nom de Mr Bojangles, communément mais respectueusement connu sous le nom de Mr Bill « Bojangles » Robinson.

Je vais essayer de refaire ce que j’ai joué pour l’accompagner au Carnegie Hall. Et comme je savais qu’il avait son revolver sur lui, j’ai vraiment tâché de faire de mon mieux (# 158) !

Plage 23 : Caravan

THE DRUMS BY JO JONES

This double album is unlike anything that was ever been recorded up to present: it shows an artist presenting the mechanics of his art with great generosity, subtlety and skill and, at the same time, his own personality as a man.

In the history of jazz, Jo Jones is one of the most outstanding drummers, full of sensitivity and style. In addition of a absolutely perfect drumming technique, he really knows, as very few others musicians do, the history of his music.

It’s not that he studied it from books – he lived it, and what’s even more rare, he knew how observe it. Everywhere that jazz musicians played, you could see Jo Jones listening most attentively. Everywhere there were jam sessions, Jo Jones was there playing drums or observing with great care how the others drummers were playing. He went all over the States and, as a young man, made himself familiar with the style and character of most varied types of musicians. He played drums in all sorts of bands, big or small, accompanied vocalists, dancers, shows and vaudevilles of all kinds. It was his ten years with the Count Basie orchestra that made him famous; and then, thousands of drummers started listening to him and studying his style; and since 1937 most of them have been influenced by him. He saved to it that young musicians benefited from his great experience and probably no none else has helped so many talented musicians to develop.

So, it’s not really surprising that Jo Jones willingly accepted Louis Panassié’s proposal to record a whole album on the art of playing drums – and art over which he has complete mastery, the mechanics of which he learnt not from books but in a way which is being lost nowadays: the way an artisan learns from others – a way therefore based on tradition.

Nowadays, one learns almost everything from books, whether they are fat tomes or slim volumes, preferably illustrated. In fact, in this way we are cutting ourselves off from life, separating ourselves from our fellow men, who getting further and further apart from each other. And so it is that today is the era of the individualist.

Jazz is entirely opposed to this way of thinking. It is essentially collective music and therefore it demands discipline, order and a generous participation from everyone. Because it’s traditional music by nature, it has rules, which are of course unwritten ones but which exist all the same. Out of these rules, each individual creates in turn, thus bringing his party of the whole. As Jo Jones puts it, it’s less a question of playing for the people than with the people.

The surprising thing about these albums is that it is just as interesting for the layman as it is for the connoisseur. For Jo Jones explains very clearly the basics of drum playing but, on the other hand, when is giving examples, whether long or short, he plays with such swing and technical perfection, drawing from his drums, cymbals and tom toms such beautiful sounds that the recordings are a delight for the connoisseur too.

The many portrayals of drummers and their different styles, the imitations of four of the greatest tap dancers not only shows Jo Jones extraordinary talent for evoking the musical personality of a musician but also give variety to these albums.

And the way Jo explains things, the tone of his voice impart to the listener a truth which he would not even think of contesting. The smoothness and delicacy of this touch banish any stiffness which there could have easily been present in a demonstration of this kind.

These albums are full of life themselves. Jo Jones is probably the only drummer who could have made such a success of the experience.

Hugues Panassié, 1973.

THE DRUMS BY JO JONES CD N° 1

Track 1: WARM UP SOLO

Track 2: Ladies and gentlemen, this is an experimental record. It’s an experimental for me, and I hope it’ll be experimental for you. There’s always been a mystery about the drum. The drum happens to be the father of the percussion section. There are a whole lot of parts to the percussions. First we go with the basics.

BASICS – GADGETS - EFFECTS

First we take the snare drum (# 1).

Next, we go to the bass drum (# 2).

And from the bass drum we go to the tom tom (#3).

And from the tom tom we go to the cymbal (# 4).

Then we put them all together and we have some sounds that go, say…(# 5).

It depends on how and when one mixes the sounds up. Now we can get fancy and lock ourselves up in dark room and it’ll come out something like this (# 6).

But also we have a few gadgets that throughout the years have been added to the percussions. Well, in the silent days – silent movies that is – you had to play effects. You had to play for the sound of the lion’s roar, you had to play for the horses’ hoofs, you had to play also crickets, you had to play baby cries, bird whistles and so forth. I have a few gadgets here, and you can imagine… If there was a fire engine, when they had the horses they always had a siren before the clinging bell ; and you’d always get a siren. But the siren that you’re most familiar with is when they came out with Black Maria.

Black Maria, as everybody knows, was the police wagon (#7) ; and right after that you heard the cry « stop thief » (# 8).

And when you came home late at night and you was wrong and you was drunk, what did your wife do? She slapped you across the head with a rolling pin (# 9). This is commonly known as a slap stick that’s how it got it’s name, from the rolling pin; and so they attached a gadget on to it and they called it a slap stick. There were a lot of things; this is commonly known as a woodblock, and you can imagine, to make the horses’ hoof you had (# 10).

All for the effects.

Just imagine now. Imagine you’re on a night club scene and you always heard this (# 11). You could have been in Spain, you know, because they would down there have pretty… oh! A long time ago.

Now, whenever you tore your clothes, you know, you see somebody that rip their trousers on the screen – or something of that humorous nature – you had a thing called a ratchet, and you must learn (# 12) that he is bending over (# 13), he’s tearing his clothes (# 14), he’s tearing his clothes (# 15); now he’s got a good rip.

Now, here you go again. They finally found out that there was a state called Texas so what did they do? They had some cows there, so, naturally, you had to have a cow bell, you know what I mean, so you had a lead cow (# 16); but to bring that down to a better level we played like this (# 17).

Now forget about the effects.

In my hand I’m holding a pair of sticks; and you can see through the record that these are sticks (# 18) because of the sound.

Now in my hand I’m holding mallets and you can see by the sound (# 19).

Now in my hand I’m holding wire brushes and you can see that these are wire brushes (# 20) by the sound. Because the wire brushes can be used with so many different effects (# 21), because if you want to make a train you can make it (# 22), and so forth.

And then when you want to play in a minor strain you use the mallets (# 23).

So much for that. Now, back to the sticks: now let’s get along with this and try and get all this together and see can we start out with a nice little tempo that’s not too difficult for anybody to play (# 24).

I forgot: I’m being accused of something that I don’t think I’m guilty off: before these other innovations came in, there was a thing that’s known as sock cymbal, it goes something like this, I’d better play my trade mark, else nobody would forgive me (# 25). Now we add them together (# 26). Nice!

It’s very essential because some of us do not have the same physical features, some of us do not have the same mental outlook, some we have natural ability, some we have to embellish that natural ability but yet retain our natural selves.

So, years ago peoples get together to try to get a thing called drum rudiments.

Track 3: RUDIMENTS: Drum roll – Flams – Single stroke

The first basic rudiment as you would know what be a drum roll; and from the drum roll you had flams; and from flams you had single stroke. Now those are the three essentials, and it’s like the time tables.

The first thing you start out with is to try and play a drum roll, try to play it I mean (# 27). Now try to play the flams: the flams should come out as though you’re saying « plum » (# 28), one stick alternately striking the drum just a fraction of a second before the others. Now we go into the single stroke, that means one stroke with each and either hand, you alternate: you start first with your left and go to right, and then you alternate (# 29).

I will start backward: in order to play a single stroke when you first start playing it does not make sense; but as soon you get it in your grasp and you begin to break it up it begins to make sense, like this (#30).

Same with the flam, very easy (#31).

Same with the roll. They have various names but there is but one drum roll, so you can start with any of the names they give it to ‘till you eventually get to the drum roll. I’ll start on the outside (# 32): it depends on what pressure, it depends on the tempo you feel and how much control.

Now, those are the three basics. Now let’s get all these things together if we can (# 33). Nice! To do that! but you must learn at all times you must have control of that. I’ll start out just with a simple beat, I’ll start with the cymbal, the snare, the sock cymbal and the bass drum, like this (# 34).

Track 4: RIM SHOTS – TOM TOM

You have heard people say the rim shots.

Well, you have several ways to do a rim shot. You can do the rim shot thusly (# 35) ; you can also do the rim shot like this (# 36), but it’s not a rim shot : that is commonly known as a stick upon top of a stick. But should you not have the qualifications (# 37) to make that (# 38), and the music is travelling too fast for your control (# 39) ; but also if you learn how to lay your stick down near at which would be in your left hand normally (# 40), you get that sound out of a sound. But the sound that you hear now (# 41) is not like (# 42) because this way you allow the drum to ring. Otherwise than that, when you put pressure on the stick (# 43) it comes out like a thud.

Now what we’ll do now is we’ll see what we can do with the tom tom.

The tom tom is a special instrument within itself too. We’ll use common beats, and the common beats is something that anybody can follow, you don’t have to get fancy with them, like this (# 44). You’ll notice that I tried to play single stroke, I tried to roll on the tom tom, I tried to put flam on the tom tom, the same (# 45) as I did (# 46) here, but you’ll notice how the tone quality changes and it gives you another thing.

Now let’s see what we can do with it and put all these things together; I will play an imaginary piece of something and then I will see what I can mix it up from the snare drum to the tom tom and using the cymbal (# 47). I got a little fancy on the end there (# 48) because there were a lot of things that I was thinking about, people I’ve met would make me do that automatically, and you’ll find out in your experience it’s the people you meet who’s going to make you play : you’re like a sponge, you’re going to absorb these things, but when you get to the basis to know these things, then you have liberty to do whatever you wish with them, like this (# 49).

Now, what I was doing: I was playing my small tom tom and I was playing my large tom tom in order to get these different effects. But you still can use the basic beat of whatever the pattern you started out on, for instance I can start on my small tom tom playing like so (# 50). You will notice that when I played the last time, I was playing on the snare drum : when you have a snare drum and when you’re playing on the tom toms, it is better that you learn how (# 51) ; not with the snares on, throw your snare off, you will get (# 52) a tom tom sound ; in other words, it will not be (# 53) as deep as the one to your right (# 54), it will not be a deep as the one in front of you, but you will strike harmony ; for instance (# 55) and you can mix up (# 56) ; and you’ll find out that’s the tone quality of the drum.

Track 5: HOME PRACTICE

Now, and don’t let anybody kid you, it is far more musical than any instrument that you have, because you have the capacity to put all these things, and that’s really why you must learn how to play with the effects.

Now when you have studied with a competent teacher, because most of the teachers you’d usually study with, they will teach you how to play, and it’s a lot of fun even if you don’t play professional, you just get a set of drums, to sit down if you have a nice little padded room, you can sit down and you don’t want to scare the neighbors, you can play with your own records or you can have somebody musical in your family, you can have friends to come over and you can find out you can have lots of fun, good relaxation just being able to just sit down when you come home from work, and you have a nice dinner and you relax and you start out playing like this (# 57).

Anybody can move to that, and you can strike up your own melodic lines.

Track 6: TWO BEAT – FOUR BEAT – THREE BEAT

Now we have something very simple to always remember.

We have three times… basic three times. They call it cut-time which will be in 4/4, or in common time I should say, and cut-time would be in 2/4. Then you have 3/4, but as I said before, from these three, when you begin to multiply, multiply… and add and distract, I mean subtract, you find out that you’ll run into later on 9/8, 9/3, 6/2 or whatever… 7/4 and all various rhythms, but we’ll start out with the basic rhythms first.

We start out with thumps that come on 1, 2, 3, 4, that goes… thus as simple as (# 58).

Now, same principle, but with another name, we will now play cut-time which is 2/4, it’s very very simple (# 59).

Now we will go into a very simple thing called the waltz: three beats to the measure, very very simple, and it’s very easy to start out, with one beat on the bass drum and two beats on the snare. Thusly: (# 59).

You don’t have to stay there because you can do (# 60) and you don’t have to do it thusly. You can do thusly, (# 61) by keeping a steady beat on your bass drum.

Perhaps rather you can add the sock cymbal in, to make the one beat accent with your bass drum like: (# 62).

Now the three basic beats that I have just said then, watch and see how simple it is to keep just a straight beat on the bass drum and you can play all those beats in the same way you play one and I say 4/4, 2/4 and 3/4, all right? We play 4/4: (# 63), 2/4 : (# 64), and the bass drum still can go right straight ahead.

So it isn’t too difficult for you to play all the different tempos at the time because you can increase your tempo, or you can decrease it, in other words, that goes with your speed, whatever you control.

Now, there are different kinds of waltzes I must tell you because you have a sort of waltz, you have a Viennese waltz like so (# 65).

If you study long enough and when you get round, you’ll find out that you can use that. And you’ll find out when you go down and say (# 66), you must (# 67).

Now I will play the same thing, I ‘ll play the waltz, but now I will play the waltz just with one hand, with my left hand you’ll hear (# 68).

That’s very simple. And later on, I wanna show you how you can take all these things together and play all of them at once, and you name your own tempo, you name your own time step, but the three basics are the ones that you will, after you get them, you will enknowledge, and that’s when you get dance band spirit.

Track 7: Now a very simple thing to do - DRUM SOLO N°1

Track 8: ACCOMPANIMENT

This segment is one of the most difficult segments that I will try to attempt to show you, and it goes something like this, whether it’d be the trumpet, or whether it’d be the saxophone.

Very simple, very easy. It won’t go in that particular sequence but you’ll find out it will go like that.

Now, that is very simple and it’s a melodic line but now, now we’re going to go into something everybody is prone to know, in the various rhythms, which is known as the latin rhythms, or they call it “Afro-Cuban”, or they call it this, that or the other.

I shall attempt, in the next segment, to go into that, but before I get out of this, I must say since I am in the big band territory rather than trio, rather than quartet, rather than five pieces, rather than six pieces, there is a difference because you have different instrumentation, you have different personalities, and you must learn how, with the equipment that you have, how to play, under the various partners that you’re playing with, because you would not play, as I’ll try to show you, you would not play behind the saxophone on this cymbal like you would with the trombone on this cymbal, or the trumpet on this cymbal. And I will strike them again (# 69). They have a different sound. It depends how you play them. I’m going to strike these same three cymbals, I will strike them once (# 70).

Now, I’ll strike them again (# 71), but I use a different process, I led a different approach of how I strike these cymbals to get a different sound so that you can get the percussion sound to play in the effects because you’re playing for three different individuals and that is a very important thing to know, and when we do these things we must remember this: that just because he’s a saxophone player, he’s a trumpet player, he’s a trombone player, it depends on which of whom you are playing with, and you have to learn how to find out whether you’re gonna play (# 72) over here, or whether to play (# 73) over there, or whether you’re going to play over here, because if he is a trumpet player he might like to hear this (# 74) he might like to hear this (# 75), if he’s a saxophone player he might want to hear this (# 76) as opposed (# 77) to you playing that cymbal. That’s for you to find out.

Now, what we do is this: as when we go round with these things, some might… they might ask you, say: “Play me a latin beat, play me this!” (# 78) as opposed to: (# 79). And you can play it (# 80), or you can play it (# 81). It depends upon the circumstances and conditions. It depends on what mood the tune’s in. It depends on the tempo, and the type of individual you’re playing for, so that you can play for the people, and you’re playing with the people on the bandstand.

Track 9: LATIN RHYTHMS

To keep the record straight I will try to attempt to play a few basic rhythms, we have rhythms they call “rumba”, we call “afro-cuban” and different ones, different things.

Everybody has a tendency to name these different things, have not… they visit these various countries, haven’t got the authentic things of these countries.

Erroneously they name the things wrong. So you say… for instance let’s start out with a basic bossa-nova beat (# 82) …but I won’t start it out that way. I will start it out basely: (# 83). OK? So much for that.

Basically, they were played that way.

Track 10: ROCK AND ROLL RHYTHM

“Well, what do you think about rock’n’roll ?”. I say: “I don’t know!”, but I say: “now here’s some things that… that we used to call something else”.

So I will go into something as a basic thing.

When they first started out, they wanted a backbeat (# 84). And then they go: (# 85). Then they embellish: (# 86). Well… then they’d get fast: (# 87). Well… all you had to do was, say: (# 88). You make your little curlicues because see, somebody in it says (# 89).

So to really try to write it with the different arrangements that the different groups have, you try to write this segment along because it doesn’t go like the standard 32 bars or 36 bar phrases or a 12 bar phrase or a blues course or something like that because they had extenuations, because they had some things that go with a long pause or whatever have you, so you play those things.

Track11: MAKING CHANGES

Earlier I spoke of the sticks, the mallets, the wire brushes.

Now: a lot of drummers, a lot of us, we all have the difficulty of making changes from the stick (# 90) to the mallet (# 91) to the brushes (# 92). Now I shall attempt to show you how to make changes. Regardless to what I start out in, I will attempt to not change the mood of the tempo that I’m playing.

So for now, I will try to play an imaginary tune and you will notice that I’m going to make all these changes and still try to keep a steady beat as much as I possibly can (# 93).

Now I shall attempt to play excerpts from three different drum solos, and I must follow the melody (Drum solo N° 3).

Track 12:

Now I shall attempt to play excerpts from three different drum solos, and I must follow the melody DRUM SOLO N°3.

Track 13: COLOURS

The most difficult thing is after you learn how to play, it’s not to play for people, it’s to play with people. And having had experience of playing with a big band, I’ll start out first playing from imaginary sense with some of the arrangements that I’ve to play and I will think of an arrangement and it will come out very simple (# 94). As you would perhaps guess, that would be a takeoff on something like Jumpin’ at the Woodside and in that I tried to play and keep strict rhythm and play the brass figures and also to try to play under the soloist; and, coming out of one segment into other, whether it be the trombone, the trumpet or the saxophone, you have certain things known as a connection, and the connection can go anyway that you can feel of whatever you do.

For instance, you’d be playing straight with any particular tune and you’re coming out of one into another: you’ll have to know the colours that you put into, in other words: if you play behind the trumpet like this (# 95), then now all at once you have a saxophone comin’in, now I will come out and go and make a transfer into the saxophone (# 96). That’s known as colouring.

Now, I can leave from the saxophone and go right to the trombone: same thing.

I’ll start with the trumpet, go to the saxophone and I’ll go to the trombone; and each time you will notice the individual beats: thusly (# 97).

You will notice I use three cymbals: one (# 98), next (# 99), next (# 100). Now you notice I say the trumpet (# 101), I say the saxophone (# 102). If I say from the saxophone to the trombone (# 103), you will notice that each one of these cymbals have a different sound (# 104, # 105). Now, we go to the ensemble; and you got to bring all these figures in and you go like this (# 106).

Now, here we go with intricate rhythms, in other words we’ll start out playing a very simple beat, the basic beat, always start basic and you’ll never go wrong because you can leave from your basic and embellish, like this (# 107). Now, I’m gonna start out with a straight four and I’m going to go into different rhythm patterns and you’ll follow them as I go along (# 108).

Well, it sounds like a bunch of mish-mash but when you put all together and when you dissect it, these little simple common things you’re allowed the privilege of embellishment on that ; so you can take these things and go for yourself ; and as you create and have your imagination with whom you’re playing with, you can take all the basic beats after you’ve had a study and what have you, and have control of your instrument, you can do whatever you wish.

And regardless to whatever they name it: YOU PLAY.

THE DRUMS BY JO JONES CD N° 2

Track 1: DRUM SOLO N°2

Track 2: DRUMMERS I MET

I shall attempt portray drummers I met over a period of my life time, and I should start from drummers you never heard about, drummers you’ve heard about and then so forth.

I shall start from Manzie Campbell; A.G.Godley, Big Sid Catlett, I must go to Mr Billy Gladstone, I must also go to a Josh, I must also, well too many people to mention. And as I go along and outline this, I will try to do the best I can and duplicate some of the characteristic things that they were famous for.

The first drummer, I will say Mr Manzie Campbell, who was with the Silas Green show, who was without a doubt the world’s greatest drummer, and was at a different context. And then I’ll lie on Mr A.G.Godley, then Alvin Burroughs and then a Mr Billy Gladstone.

Track 3: Baby Dodds

I will not forget Baby Dodds, I think it’s best that I start out and give you a thing called the shimmy. This is Baby Dodds’ shimmy (# 109).

Track 4: Josh

Josh was a drummer in Kansas City that he never played nothing but just the snare drum. And he used to always play and swing any jam sessions we had with Hot Lips Page, Herschel Evans, Lester Young, Walter Page, Basie, Pete Johnson, it didn’t matter, he played this way, he could swing you! I will start out this way (# 110) … now Josh, you will notice…

Track 5: Unnamed drummer

Then there was another drummer in Saint Louis (Jo Jones didn’t want to give his real name) and he played thusly and he could swing the band like this (# 111). Now, here is a short brochure of cross sticking, a variation of the cross sticking is very easy to do ; I will show you how he would elaborate on that, because he did not have a sock cymbal – because I was the only bum out here with a sock cymbal – but he would just take the snare drum, so I’m going to release my foot of the snare drum (slip on the tongue: Jo Jones says «snare drum» for «sock cymbal») and try to show as best as I can as how he used to just play just with the snare drum and would be jamming, or he could sit in a fourteen piece band and swing the whole band and twelve chorus girls like this (# 112) :

Track 6: Alvin Burroughs

A.G.Godley was an all round man but before I get to A.G.Godley, Alvin Burroughs was a tom tom man, I thought !

But Alvin Burroughs was a cymbal man. Now, the best way I can tell you how he used to play the cymbal, he would take a quarter and put on in his hand and the