- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

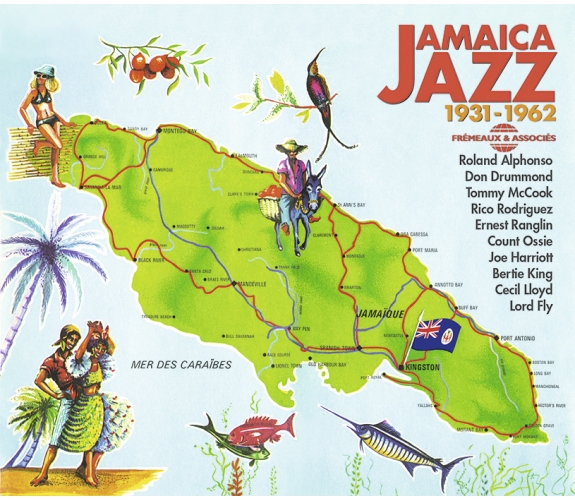

ROLAND ALPHONSO • DON DRUMMOND • TOMMY McCOOK • RICO RODRIGUEZ • ERNEST RANGLIN • COUNT OSSIE • JOE HARRIOTT • BERTIE KING • CECIL LLOYD • LORD FLY…

Ref.: FA5636

Artistic Direction : BRUNO BLUM

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Total duration of the pack : 3 hours 41 minutes

Nbre. CD : 3

ROLAND ALPHONSO • DON DRUMMOND • TOMMY McCOOK • RICO RODRIGUEZ • ERNEST RANGLIN • COUNT OSSIE • JOE HARRIOTT • BERTIE KING • CECIL LLOYD • LORD FLY…

ROLAND ALPHONSO • DON DRUMMOND • TOMMY McCOOK • RICO RODRIGUEZ • ERNEST RANGLIN • COUNT OSSIE • JOE HARRIOTT • BERTIE KING • CECIL LLOYD • LORD FLY…

The best Jamaican musicians brought a substantial, masterful contribution to jazz. Their belated recognition reveals truly original, spirited and sophisticated styles. At long last, the rare, little known albeit greatest recordings of the founders of Jamaican jazz are gathered here, fully annotated in a 32-page booklet by Bruno Blum. They include strong personalities such as Wilton Gaynair, Cecil Lloyd, Billy Cooke; Ernest Ranglin’s quirky guitar playing and groundbreaking afro-jazz by Count Ossie’s drum orchestra, as well as the legendary Joe Harriott, Roland Alphonso, Tommy McCook, Don Drummond and Rico Rodriguez. These musicians, who were about to create ska and reggae, breathe stunning life into swing, mento, blues, hard bop and soul jazz. PATRICK FRÉMEAUX

THE ROOTS OF JAMAICAN SOUL

THE KINGSTON RECORDINGS 1951-1958

RHYTHM AND BLUES SHUFFLE

CARIBBEAN JAZZ PIONEERS IN PARIS 1929 - 1946

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Tap Your FeetJack Hart00:02:561465855200

-

2Blue Light BluesBenny Carter00:03:071465855200

-

3Snakehips SwingAdrian De Haas00:02:511465855200

-

4Big Top BoogieLeslie Hutchinson00:02:581465855200

-

5Swing Low Sweet ChariotMusique Traditionnelle00:02:551465855200

-

6Donkey CityMusique Traditionnelle00:02:401465855200

-

7Swine Lane Gal Iron BarMusique Traditionnelle00:02:461465855200

-

8Brown Skin GalMusique Traditionnelle00:02:331465855200

-

9Wheel and Tun MeMusique Traditionnelle00:03:071465855200

-

10Parish GalHarold Richardson00:02:581465855200

-

11Dry Weather HouseE.F. Williams00:02:501465855200

-

12Industrial FairAlerth Bedasse00:03:011465855200

-

13Akee BluesJoe Harriott00:03:021465855200

-

14CherokeeRay Noble00:03:041465855200

-

15April in ParisE.Y.Harburg00:03:011465855200

-

16How Deep Is the OceanIrving Berlin00:02:541465855200

-

17BangDizzy Reece00:03:071465855200

-

18Fascinating RhythmGeorge Gerschwin00:02:461465855200

-

19Just Goofin'Joe Harriott00:02:031465855200

-

20Everything Happens to MeT. Adair00:04:451465855200

-

21Blues for TonyWilton Gaynair00:07:121465855200

-

22Eb PobFats Navarro00:07:281465855200

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Blues OriginalJoe Harriott00:03:391465855200

-

2ChorousDizzy Reece00:02:581465855200

-

3The GypsyBilly Reid00:03:341465855200

-

4ReservedTyler00:02:161465855200

-

5CumanaH. Spina00:02:521465855200

-

6ManhattanRichard Charles Rodgers00:02:381465855200

-

7Old Devil MoonBurton Lane00:02:591465855200

-

8The Escape and ChaseDizzy Reece00:02:481465855200

-

9I Had the Craziest DreamHarry Warren00:03:051465855200

-

10Foggy DayG. Gerschwin, I. Gerschwin00:02:091465855200

-

11Lullaby of the BirdlandGeorge Shearing00:02:391465855200

-

12VolareDomenico Modugno00:02:281465855200

-

13DeborahWilton Gaynair00:04:061465855200

-

14RhythmWilton Gaynair00:05:211465855200

-

15CaravanJuan Tizol00:05:401465855200

-

16AbstractJoe Harriott00:03:371465855200

-

17ImpressionJoe Harriott00:05:301465855200

-

18Calypso SketchesJoe Harriott00:04:431465855200

-

19Air Horn ShuffleRico Rodriguez00:03:001465855200

-

20Fire EscapeRico Rodriguez00:02:391465855200

-

21What Is This Thing Called LoveDon Drummond00:03:111465855200

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Swing for JoyEmmanuel Rodriguez00:03:111465855200

-

2I'll Remember AprilGene De Paul00:06:021465855200

-

3Green EyesAdolfo Utrera00:02:361465855200

-

4I Cover the WaterfrontJohnny Green00:04:371465855200

-

5Softly as in the Morning SunriseOscar Hammerstein00:03:451465855200

-

6Sometimes I Am HappyVincent Youmans00:03:131465855200

-

7Grooving with the BeatDon Drummond00:05:281465855200

-

8ExodusErnest Gold00:03:001465855200

-

9Calypso Jazz Iron Bar aka Jamaica FarewellTraditionnel00:03:171465855200

-

10Serenade in SoundDon Drummond00:04:211465855200

-

11Never on SundayBilly Towne00:03:061465855200

-

12Away from YouRichard Charles Rodgers00:04:251465855200

-

13Mr. PropmanDon Drummond00:02:301465855200

-

14It HappensCecil Lloyd00:06:281465855200

-

15The AnswerTommy McCook00:07:441465855200

-

16TangerineJohnny Mercer00:06:081465855200

-

17Harry FlicksHarold McNair00:05:251465855200

Jamaica Jazz FA5636

Jamaica

Jazz

1931-1962

Roland Alphonso

Don Drummond

Tommy McCook

Rico Rodriguez

Ernest Ranglin

Count Ossie

Joe Harriott

Bertie King

Cecil Lloyd

Lord Fly

Jamaica - Jazz 1931-1962

par Bruno Blum

C’était avant le temps du rock and roll. Le jazz c’était le truc. Si tu ne jouais pas de jazz, tu ne jouais rien du tout.

— « Dizzy » Johnny Moore1

La Jamaïque est proche du continent américain. Ses jazzmen sont issus d’une culture afro-américaine anglophone semblable à celle de leurs célèbres collègues états-uniens. L’exclusion des meilleurs musiciens jamaïcains de la grande histoire du jazz et du vedettariat est due à leur nombre restreint et à leur nationalité — mais pas à leur manque de talent. À Londres comme à New York, les conséquences sociales de leur exil ont accru leurs difficultés d’intégration et de reconnaissance dans le monde très dur du jazz. Si l’on excepte les fondateurs des Skatalites, qui participèrent à nombre d’enregistrements de ska et de reggae par la suite (notamment avec Bob Marley), les plus grands jazzmen jamaïcains n’ont pas connu l’appréciation qu’ils méritent. Leur œuvre est aussi méconnue qu’elle est remarquable : pour les amateurs de jazz qui la découvrent, elle souffle comme un vent de fraîcheur, une bonne surprise. Cet album vise à la réhabiliter, à lui donner la place qui devrait être la leur dans l’historiographie du jazz. Les connaisseurs ne s’y tromperont pas en écoutant la fascinante virtuosité de Joe Harriott, un bopper visionnaire pionnier du free jazz, dont même la vie difficile et irrégulière en exil explique mal comment pareil talent a pu si longtemps rester exclu du panthéon jazz. Même remarque pour le style singulier du guitariste et arrangeur Ernest Ranglin, actif depuis les années 1940 — ou pour la fulgurance de Wilton Gaynair, Cecil Lloyd ou Dizzy Reece, dont les noms mêmes restent inconnus de bien des experts.

Et que dire de l’extraordinaire ensemble de tambours rastafariens de Count Ossie, qui cristallisa pour la première fois de l’histoire du jazz une fusion profonde entre hard bop, blues et racines bantoues ? Sans oublier les jazzmen Roland Alphonso, Don Drummond et Tommy McCook qui jouèrent avec Count Ossie et comptent parmi les créateurs et monstres sacrés du ska en 1961-65, du rocksteady puis du reggae à partir de 1968. Leurs premiers enregistrements ont été réalisés dans une optique de jazz moderne, un style dont ils étaient des fanatiques comme leur célèbre producteur, le fondateur du ska Clement Seymour « Coxsone » Dodd (Studio One). Un florilège de ces disques importants et savoureux, pour la plupart introuvables ou négligés, est pour la première fois réuni ici en bon ordre.

LE JAZZ EST NÉ AUX CARAÏBES

Célébré comme une création états-unienne par une historiographie elle-même états-unienne, le jazz est plus exactement le produit d’une culture afro-créole, c’est à dire d’un mélange d’éléments africains et européens qui ont fusionné en une nouvelle culture, bien distincte des deux premières. Or ce paradigme est propre aux Caraïbes et ne se limite pas aux États-Unis. La Nouvelle-Orléans, berceau du jazz aux États-Unis, est un exemple caractéristique de cette créolité caribéenne fondamentale. À tel point que Ned Sublette l’appela « La capitale des Caraïbes »2. Cette ville isolée du continent par de vastes marais est tournée vers la mer des Antilles et le fleuve Mississippi, qui fut longtemps la principale voie d’accès vers l’intérieur du continent. C’est sur ses bateaux que le jazz et les jazzmen se propagèrent vers le nord. Grand port des Caraïbes, la Nouvelle-Orléans a une histoire de mixité sociale et raciale analogue à celle des îles alentour. Elle a en outre été considérablement marquée par les esclaves caribéens qui y furent déportés en masse au fil du XIXe siècle (bouleversements géopolitiques à Cuba, révolution haïtienne, etc.).

Cet apport caribéen (aux racines Ibo, Akan, Yoruba, Bantoues et autres) a renforcé la grande richesse des séances de musique et de danse qui prenaient place au cœur de la Nouvelle-Orléans à Congo Square. Les différentes

ethnies et cultures afro-créoles caribéennes y cohabitaient et se concurrençaient lors de ces rendez-vous musicaux uniques aux États-Unis au temps de l’esclavage. Ce fait historique met en évidence les racines profondément caribéennes et afro-créoles du jazz états-unien. On peut par exemple supposer que les rythmes ternaires (swing en anglais) caractéristiques du jazz américain, qu’Art Blakey décrivit comme étant une création états-unienne, plongent en fait leurs racines dans des rythmes venus de Jamaïque ou du vaudou haïtien et sont hérités d’une tradition bantoue bien plus ancienne3. Ces rythmes étaient souvent appliqués à des mélodies européennes4. Depuis au moins le XIXe siècle, cette créolisation de musiques européennes était la norme dans les rues des quartiers noirs de la Nouvelle-Orléans comme dans toutes les Caraïbes et n’a plus cessé5. L’histoire des influ-entes musiques populaires de Louisiane et donc du continent nord-américain sont ainsi indissociables de leur patrimoine afro-caribéen. Les musiques des Caraïbes et des États-Unis sont distinctes mais ont connu une évolution parallèle et analogue, comme en témoignent notamment les précieux enregistrements des années 1920 des Trinidadiens mulâtres juifs sépharades Sam Manning (1899-1961) qui travailla longtemps avec Amy Ashwood Garvey (la première épouse jamaïcaine du politicien Marcus Garvey) et Lionel Belasco (1881-1967).

En passant par la porte de la Louisiane les Antillais, pour la plupart cubains et haïtiens mais aussi jamaïcains, trinidadiens, etc. n’ont cessé de diffuser leur héritage musical décisif sur le continent américain où les éléments de racine africaine étaient bien plus discrets car cruellement réprimés par la loi. L’exception néo-orléanaise leur a permis d’apporter massivement sur le continent des rythmes très influents, des mélodies caribéennes, notamment calypso (Trinité et Tobago), les styles troubadour, rumba (Cuba) et mento (Jamaïque) ainsi qu’une panoplie d’éléments culturels comme l’utilisation de tambours, en principe interdits sur le continent en dehors de la Nouvelle-Orléans (si l’on excepte les tambours militaires). Les Caribéens étaient nourris par un héritage de musiques de transes animistes profondément enracinées comme le vodou (Haïti), le kumina (Jamaïque) et à Cuba la santería, la musique sacrée des orishas lucumí (yoruba), de la société secrète Abakuà des Carabalí (Calabar), etc. Ces éléments afro-créoles sont à l’origine des spirituals des esclaves, eux-mêmes à la source du gospel du XXe siècle, aux Antilles comme sur le continent. Les musiciens antillais ont toujours été présents aux États-Unis (voodoo, hoodoo6). Les racines de l’improvisation dans le jazz sont d’ailleurs à chercher dans les expressions vocales inintelligibles couramment effectuées durant ces transes (la glossolalie ou speaking in tongues inspirée par les esprits des défunts ou selon les rites, le Saint Esprit, etc.). Par la suite, la diaspora antillaise a été jusqu’à créer sur le continent des styles essentiels comme la salsa7 ou le rap, issus tous deux de matrices caribéennes8. Inversement, les musiciens américains ont circulé aux Antilles. Avec l’avènement des disques 78 tours entre les deux guerres mondiales, l’influence du jazz en particulier y est devenue importante9. En 1935 la mode du swing a décuplé l’impact inter-national du jazz.

JAMAICA IN AMERICA

La diffusion des premiers disques de calypso trinidadien (enregistré dès 1914) et de jazz américain dans les années 1920 a fortement touché les Caraïbes. Ces musiques sophistiquées étaient issues de cultures créoles comme les leurs et les Antillais souhaitaient faire partie de ce courant pan-caribéen. Certains ont choisi le jazz comme un vecteur d’exil, une raison de partir, de chercher à communier avec des icones du jazz comme Louis Armstrong10. Et surtout, comme les Haïtiens, les Dominicains ou les Cubains, les Jamaïcains ont de tous temps cherché à s’exiler pour des raisons économiques. Les proches États-Unis ont toujours été pour eux un miroir aux alouettes. La diaspora jamaïcaine s’est implantée à Miami, Toronto et New York, où était installé le grand leader politique jamaïcain Marcus Garvey (jusqu’au procès qui le brisa en 1921-1923, suivi par son expulsion en 1927). L’essentielle organisation nationaliste noire internationale de Garvey, l’United Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) contribua à la renaissance cultu-relle de Harlem entre les deux guerres. Dès le début du XXe siècle, des musiciens jamaïcains étaient présents dans le crucial développement du jazz à New York. Des tonnes de chanvre en provenance de Jamaïque étaient aussi fumées à Harlem, où elles étaient vraisemblablement diffusées par la diaspora jamaïcaine. À leur façon elles contribuèrent à donner forme au jazz joué par des musiciens friands de reefer11. Dans les années 1940-50 ce chanvre était sans doute exporté en bonne partie par l’importante communauté du Pinnacle à Sligoville (Jamaïque), qui était dirigée par le fondateur du mouvement Rastafari Leonard Howell. Howell, un aventurier jamaïcain utilisant l’herboristerie, avait longtemps vécu à Harlem et était imprégné des idées panafricanistes de l’influent Garvey12. Les musiciens new-yorkais étaient conscients de cette présence caribéenne fondamentale, comme en attestent le « St. Thomas » de Sonny Rollins (1956) ou la version du standard de mento jamaïcain « Sly Mongoose » gravée en 1952 par Charlie Parker. Elle fut d’ailleurs enregistrée pour la première fois en 1923 par le pianiste de jazz et de calypso Lionel Belasco, un Trinidadien de père juif sépharade qui se rendit plusieurs fois à New York13. En fait Belasco dirigea l’un des tout premiers groupes de jazz noir jamais enregistrés (septembre 1918) : du jazz caribéen.

Dans son autobiographie, Duke Ellington écrit ceci de son célèbre tromboniste Joe « Tricky Sam » Nanton :

« Il jouait une forme très personnelle de son héritage antillais. Quand un type des Antilles vient ici et qu’on lui demande de jouer du jazz, il joue ce qu’il pense être du jazz, ou une chose qui résulte de sa volonté de se conformer à cet idiome. Tricky et son peuple étaient à fond dans le mouvement des Antilles et de Marcus Garvey. Tout un pan de musiciens antillais a surgi et contribué à ce qu’on appelle le jazz. Ils descendaient virtuellement tous de la véritable scène africaine14. »

JAZZ BRITANNIQUE NOIR

Selon l’historien de la musique jamaïcaine Daniel Neely, des artistes américains se sont produits à Kingston dès les années 1910 au moins, notamment au Ward Theatre. Ils incluaient des spectacles de minstrels qui contenaient vraisemblablement des styles associés au jazz américain. Avant son exil aux États-Unis, Marcus Garvey organisa aussi quelques concerts. Ils firent des émules ; C’est dès 1924 que le saxophoniste alto Louis Stephenson (né en 1907), Leslie « Jiver » Hutchinson, Leslie Thompson et Joe Appleton gagnèrent à Kingston un concours dont le prix était un engagement de six semaines à Londres dans l’exposition « British Empire » à Wembley. La popularité des musiques afro-américaines n’a cessé de grandir en Jamaïque dans les quatre décennies suivantes.

Nombre de musiciens américains en visite en Jamaïque utilisaient temporairement des musiciens noirs locaux et les emmenaient parfois ensuite jusqu’en Europe. L’orchestre de swing le plus renommé de Grande-Bretagne était celui de Ken « Snakehips » Johnson, l’inventeur de la danse shimmy (analogue à la danse zépaules vodou) qui repartit chez lui en Guyane britannique en 1932. Il revint ensuite à Londres et devint danseur de claquettes à la tête d’une formation avec laquelle il voyagea sur trois continents. Le trompettiste jamaïcain Leslie Thompson était très marqué par les idées de son compatriote Marcus Garvey et rêvait comme lui d’un groupe de bal entièrement noir. Selon la vision mondialiste de Garvey, l’attrayante musique noire pouvait être implantée à Londres comme ailleurs et se passer de Blancs en ces temps de complexes raciaux — et d’apogée de l’empire colonial britannique. Leslie Thompson avait émigré en Grande-Bretagne et contribua à l’orchestre de jazz de Spike Hughes, dont on peut écouter ici Tap Your Feet enregistré en 1931. Thompson a, entre autres, accompagné Louis Armstrong en 1934. Puis il rejoint la formation de Snakehips Johnson et en devint le directeur musical. On y retrouvait plusieurs autres Jamaïcains : le trompettiste Leslie George « Jiver » Hutchinson (6 mars 1906-22 novembre 1959), York de Souza (piano), Louis Stephenson (alto sax, clarinette), Joe Appleton (sax) et la vedette Bertie King (clarinette, saxes alto et tenor). Cet orchestre noir joua au fil de la décennie dans des établissements londoniens comme le Cuba Club (le futur Ronnie Scott’s sur Gerrard Street à Soho), le Frisco et le Panama du centre-ville, qui étaient fréquentés par des cuisinières et des dockers jamaïcains venus des quartiers populaires de l’est de la ville. Les autres musiciens de Spike étaient sud-africains, caribéens ou afro-britanniques15.

En 1935 le clarinettiste et saxophoniste jamaïcain Bertie King émigra en Europe. Après différentes tournées dont une avec Coleman Hawkins il enregistra trois titres à Paris avec Django Reinhardt et l’orchestre de Benny Carter. Leur version de Blue Light Blues a été gravée avec le pianiste jamaïcain York de Souza. Albert « Bertie » King (1912-1981) était né à Panama, où de nombreux travailleurs jamaïcains participèrent à la construction du célèbre canal inauguré en 1914. Il a ensuite été élevé à Kingston en Jamaïque. Comme nombre de grands musiciens jamaïcains de premier plan — et comme ici Don Drummond, Rico Rodriguez, Dizzy Reece, Joe Harriott, Tommy McCook et Harold McNair — King avait étudié la musique à la fameuse école catholique romaine de garçons Alpha, dont la directrice Sister Ignatius collectionnait les disques de jazz. C’est avec son ami trompettiste Leslie « Jiver » Hutchinson (qui enregistrerait avec Mary Lou Williams en 1952), Louis Stephenson et York de Souza qu’il forma un groupe de bal au répertoire partagé entre jazz et mento, Bertie King and the Rhythm Aces. Débarqué en Angleterre le 19 novembre 1935, l’excellent King enre-gistra avec ses amis au cœur du milieu jazz caribéen de Londres, notamment avec les groupes de Snakehips et Jiver Hutchinson. Il rejoint ensuite la Royal Navy britannique de 1939 à 1943. En 1944, il enregistrait à nouveau avec ses compatriotes Hutchinson, York de Souza et Joe Appleton.

Ouvert en 1952 dans une cave de Coventry Street à Soho (avant de partir au 33 Wardour Street en 1957), le Flamingo Club devint l’un des principaux clubs de musiques afro-américaines et caribéennes de Londres. Des musiciens de rhythm and blues jamaïcain (le ska en gestation) et de jazz comme Joe Harriott se produisaient dans ce lieu mal famé où fermentait la future culture mod des années 1960. Billie Holiday, Ella Fitzgerald et Sarah Vaughan y chantèrent ; Le Flamingo était fréquenté par les vrais amateurs de jazz tenus de porter la cravate pour y entrer. Son influence fut immense. Il devint par la suite le rendez-vous des musiciens de rock comme les Beatles ou plus tard Jimi Hendrix. C’est ainsi qu’un soir le batteur de jazz Charlie Watts y invita le futur chanteur des Rolling Stones, qui assista à son tout premier concert :

« Ça fait des années que j’écoute du ska, en fait ! C’est même la première musique que j’ai jamais vue jouer sur scène ! Au Flamingo Club… c’était Prince Buster qui chantait avec le groupe de Georgie Fame, en 1958. […] J’ai alors commencé à rêver de devenir aussi connu que Georgie Fame16 ».

MENTO

En Jamaïque, la société coloniale britannique se nourrissait de musiques populaires européennes et américaines. Elle méprisait les musiques folkloriques afro-jamaïcaines : musiques rituelles afro-jamaïcaines (kumina, pukumina, musiques des Marrons, etc.) et chrétiennes (negro spirituals, gospel pentecôtiste, baptiste, adventiste etc.)17. Dérivé du quadrille européen que les esclaves jouaient initialement pour leurs maîtres, le mento local et ses chansons salaces (aux éternelles métaphores sexuelles : Donkey City, Iron Bar, Dry Weather House…), populaires et dansantes était considéré par la classe blanche au pouvoir comme une musique indigène vulgaire, sans grand intérêt.

Le mento était bien distinct du calypso anglophone de Trinidad18. Quelques artistes de mento urbain se produisaient dans les cabarets des villes en partie fréquentés par des Blancs, mais avec son image d’élégance et sa réputation internationale le jazz était la seule forme de musique noire qui obtenait à la fois les faveurs de la haute société et celles de la population noire défavorisée. Après avoir collaboré avec divers artistes dont le chanteur et trompettiste anglais blanc Nat Gonella, un émule de Louis Armstrong, Bertie King quitta l’Europe en 1951 et reforma un groupe de mento à Kingston. Il espérait profiter de l’intérêt grandissant du public pour les musiques caribéennes grâce à la mode du calypso trinidadien qui était copié un peu partout dans les années 1940-5019. Le tourisme commençait à se développer aux Caraïbes ; Fréquentés par des Américains et Britanniques, les grands hôtels de la côte nord et quelques cabarets de Kingston accueillaient désormais la musique mento indigène qui plaisait aux vacanciers. Bertie King fut l’un des tout premiers artistes jamaïcains à enregistrer dans l’île, dirigeant des séances dès 1951 dans le petit studio artisanal du producteur juif sépharade débutant Stanley Motta. Il accompagna à la clarinette différents artistes de mento, dont Harold Richardson & the Ticklers, Hubert Porter et les Tower Islanders retenus ici. C’est vraisemblablement lui qui a mis Stanley Motta en contact avec Emil Shalit des disques Melodisc (et bientôt Blue Beat) à Londres. Fabriqués à l’étranger (États-Unis ou Royaume Uni), les disques de mento étaient vendus aux touristes dans les hôtels de Jamaïque où jouaient les artistes du genre. Huit de ces disques microsillons 25cm de mento et jazz-mento (plus quatre ou cinq 45 tours et une cinquantaine de 78 tours) parurent en 1954-1957 chez Melodisc à Londres20. King retourna plusieurs fois dans la capitale britannique, travaillant parallèlement avec des musiciens de jazz comme Chris Barber ou Kenny Baker. Bertie King a tourné jusqu’en Asie et en Afrique avant de diriger le groupe maison de la Jamaica Broadcasting Corporation (radio JBC) auquel Ernest Ranglin participa. Il enregistra aussi avec l’orchestre de John « Dan » Williams, grand-père de la future chanteuse de reggae et disco jamaïcaine Grace Jones.

Le saxophoniste de Dan Williams and his Orchestra était Rupert Lyon, un musicien de jazz qui comme Bertie King en a eu assez de l’exil et revint vivre en Jamaïque. Rupert Lyon devint alors chanteur de mento sous le nom de Lord Fly. Le mento était très populaire avant-guerre en Jamaïque mais n’y fut enregistré qu’à partir de 1949 ou 195021. Né en 1905 à Lucea en Jamaïque dans une famille de musiciens, Rupert Lyon avait longuement joué à New York dans les années 1920, puis à Cuba dans un groupe de rumba avant de faire ses débuts de chanteur dans l’orchestre jamaïcain « calypso » de Hugh Coxe, avec lequel il se produisit pour les soldats pendant la Deuxième Guerre Mondiale. Vétéran des orchestres jamaïcains de danse, notamment celui de George Moxey, Lyon profita lui aussi de la vogue « calypso » de l’après-guerre22. Le directeur du Colony Club de Kingston le rebaptisa alors Lord Fly. Sa version instrumentale du mento Donkey City est sans doute le plus ancien enregistrement de pur jazz jamaïcain. Lord Fly y exécute un remarquable solo de saxophone ténor de plus de deux minutes. N’oublions pas non plus la contribution de Sugar Belly, qui confectionnait lui-même ses étonnants « bamboo sax » avec une tige de bambou, du carton et du scotch et joua sur de nombreux disques de mento. En dépit d’un peu de distorsion sur la voix d’Alerth Bedasse, le rarissime 78 tours Industrial Fair du Chin’s Calypso Sextet est inclus ici car il montre le style indigène particulier de Sugar Belly, qui s’inscrit dans une tradition d’instruments à vent jamaïcaine bien plus ancienne, aux vraies racines du jazz.

JOE HARRIOTT, WILTON GAYNAIR, DIZZY REECE, HAROLD McNAIR : L’EXIL

Les premiers ensembles de bal professionnels (Rhythm Raiders, King’s Rhythm Aces) avaient émergé en Jamaïque au début des années 1930 et participaient à des concours. Milton McPherson était une vedette avant-guerre. Les orchestres « swing » de Whylie Lopez, George Alberga et Ivy Graydon interprétaient le jazz à leur manière locale dans les années 1940. Ils avaient pour clients principaux la société blanche. Mais les orchestres de Sonny Bradshaw, Eric Deans et Roy Coburn Blu-Flames où jouèrent au début des années 1950 Don Drummond, Tommy McCook, Wilton Gaynair, son frère Bobby et Harold McNair jouaient aussi pour un public populaire qui les adoraient. ZQI, la seule radio jamaïcaine, ne diffusait pas de jazz et les propriétaires de récepteurs (parmi lesquels des bars) se tournaient souvent vers la radio de l’armée américaine (Armed Forces Radio Service), la BBC, les stations de la Nouvelle-Orléans, WLAC à Nashville et WINZ à Miami23, qui diffusaient parfois du rock et du jazz. L’historien Klive Walker explique24 :

« Certains musiciens des années 1940 n’avaient pas été à l’école Alpha, notamment les trompettistes Sonny Grey, Roy Burrowes et Sonny Bradshaw, le guitariste Ernest Ranglin, les saxophonistes Andy Hamilton et Roland Alphonso qui en 1964 fonderait les Skatalites. Tout comme ceux sortis d’Alpha ils étaient capables de jouer le difficile bebop, le nouveau jazz créé après-guerre par Charlie Parker et Dizzy Gillespie. Comme la génération précédente, tous ont essayé de quitter leur île pour faire mûrir leur art et avancer leur carrière. Ranglin est parti travailler aux Bahamas. »

Tommy McCook est parti jouer aux Bahamas en 1954 et n’est revenu qu’en 1962. Dans les années d’après-guerre Wilton Gaynair, Grey, Burrowes, Reece et Joe Harriott sont parvenus à quitter le pays pour de bon. Parmi les solistes exilés, le plus important est sans doute Joe Harriott, qui avait étudié chez Alpha aux côtés de Gaynair, McNair et Tommy McCook. Il a commencé sa carrière en jouant dans deux des orchestres dominants de l’après-guerre, Sonny Bradshaw et Eric Deans, puis fut invité plusieurs fois par l’organisateur Count Buckram à la fin des années 1940. Harriott a débarqué à Londres dans la formation d’Ossie DaCosta avec qui il tourna un temps avant de se fixer dans la capitale anglaise en 1951. Il y enregistra à partir de 1954, gravant sa composition Akee Blues (l’aki est le légume national jamaïcain) avec des musiciens de highlife dans un style rhythm and blues en vogue en Jamaïque à cette époque25. Comme Sonny Stitt et d’autres saxophonistes alto de cette période, Joe Harriott était imprégné par le style innovant de Charlie Parker, comme on peut le constater en écoutant son interprétation de Cherokee, sans doute la meilleure de ce morceau après les célèbres versions de Parker. Tout au long des années 1950, tant par sa technique que sa créativité l’excellent Harriott fut probablement le meilleur artiste de la scène anglaise de jazz. Il joua dans les groupes de Pete Pitterson, Ronnie Scott et Tony Kinsey et bénéficia du soutien des meilleurs musiciens anglais dont Bill LeSage et Phil Seamen. En 1959, son remarquable premier album Southern Horizons a été enregistré avec le non moins excellent bassiste jamaïcain Coleridge Goode, qui restera avec lui pendant des années — mais sans succès malgré la qualité de leur travail. Les triom-phes et tragédies de la vie de Joe Harriott sont contés dans une biographie épique26.

Surnommé Bogey (comme bogeyman, le « magicien » du sax), le saxophoniste ténor Wilton « Bra » Gaynair (11 janvier 1927, Kingston-13 février 1995, Allemagne), est une autre légende oubliée du hard bop jamaïcain. Comme son frère saxophoniste Bobby (qui a enregistré avec Clue J & the Blues Blasters), il a connu Harriott, McNair et Drummond à l’institution pour défavorisés Alpha Boys School où ils étudièrent la musique avec rigueur. Après ses débuts dans les clubs de Kingston, il a accompagné des vedettes comme George Shearing et Carmen McRae de passage dans l’île, puis s’est exilé en Allemagne en 1955 à l’occasion d’un engagement avec Dizzy Reece. Il a peu enregistré (trois albums sous son nom) en dépit de son incontestable talent. Les trois titres ici sont extraits de Blue Bogey, son lumineux premier album gravé à Londres. De retour à Kingston, Bogey a participé aux premières séances de Count Ossie pour le producteur débutant Harry A. Mudie. Au fil de sa vie Gaynair jouera avec Freddie Hubbard, Gil Evans, Shirley Bassey, Horace Parlan, Manhattan Transfer, Bob Brookmeyer, Mel Lewis…

Exilé en Europe en 1949, le trompettiste Dizzy Reece (Kingston, 5 janvier 1931) a vécu à Londres de 1954 à 1959. Les innovateurs du hard bop lui ont fait beaucoup d’ombre mais, après diverses séances de studio avec de grands musiciens anglais, il a enregistré son premier album pour Blue Note à Londres avec Donald Byrd. Salué par Miles Davis alors au sommet avec « Kind of Blue », Reece a emprunté les musiciens de Miles pour Star Bright (dont Eb Pob est extrait).

D’autres musiciens, dont Sonny Grey et Noel Gillespie, s’exilèrent. Le saxophoniste alto, ténor et flûtiste Harold McNair (Kingston, 5 novembre 1931-Maida Vale, Londres, 7 Mars 1971) dit « Little G », un autre musicien jamaïcain renommé, était un ami proche de Joe Harriott. Ils avaient étudié à l’Alpha School ensemble et joué dans le groupe de Baba Motta avec Wilton Gaynair. Après un rôle dans le film Island Women (1958), il devint chanteur de goombay-calypso sur son premier album enregistré aux Bahamas27. Il partit pour Londres en 1960 après une tournée européenne dans le groupe de Quincy Jones et quelques musiques de films à Paris. On peut aussi l’entendre jouer la première version de « Peggy’s Blue Skylight » avec le quartet de Charles Mingus dans le film All Night Long. Habitué du club Ronnie Scott’s, il y enregistra avec son groupe de hard bop (inclus ici) à l’occasion d’une double affiche avec Zoot Sims. Il retourna ensuite aux Bahamas et enregistra d’autres disques de jazz de qualité.

En 1958 Joe Harriott fut atteint d’une pneumonie et d’une pleurésie. C’est au cours de ses trois mois et demi d’hospitalisation à la fin de l’année qu’il a conçu son premier album en tant que leader, choisissant une direction plus abstraite que le hard bop. Après différents enregistrements splendides dont une version frénétique de Caravan où figure un solo de bongo de Frank Holder, Harriott était à la pointe des derniers développements du jazz américain. Il était au courant de la direction nouvelle prise par Ornette Coleman (lui aussi un émule de Charlie Parker), dont il avait lu une interview — mais pas entendu les disques. Gravé en 1960, Southern Horizons est un chef-d’œuvre qui fait de Joe Harriott l’incontestable pionnier et maître du free jazz européen (faute d’un terme plus exact). Deux extraits, Abstract et Impression, sont inclus ici.

DON DRUMMOND, CECIL LLOYD, BILLY COOKE, TOMMY McCOOK, ERNEST RANGLIN & ROLAND ALPHONSO : JAZZ EN JAMAÏQUE

En 1954 plusieurs concerts de jazz importants ont pris place au Ward Theater de Kingston. L’engouement local pour le jazz était encore renforcé par le développement des sound systems (soirées dansantes au son de dis-ques28). Plusieurs artistes émergèrent alors, dont la chanteuse Totlyn Jackson (née en 1930 à Port Maria, Jamaïque). Elle enregistra un titre en tant qu’invitée sur le premier album de Lance Hayward, un pianiste bermudien aveugle venu jouer une saison à l’hôtel Half Moon de Montego Bay29. Son Old Devil Moon figure sur cet album, le tout premier publié par Island, une nouvelle étiquette lancée par le futur grand producteur jamaïcain Chris Blackwell (Bob Marley, U2, etc.). Selon le schéma local habituel, Totlyn avait été élevée par sa mère et suivi une éducation religieuse (presbytérienne) avec son frère et ses deux sœurs. Elle pratiqua très tôt le chant gospel et découvrit le jazz avec les orchestres de Tim Barnet et Eric Deans.

La Jamaïque est un pays où, selon Robbie Shakespeare, « les gens aiment plus la musique qu’ailleurs »30. Ce pays a toujours produit des musiciens remarquables qui n’ont pas eu la carrière que méritait leur talent. Venu de Port Maria, un village isolé en bord de mer dans une région sauvage de l’île, Cecil Lloyd est l’un de ces magiciens méconnus, qualifié là-bas de « génie », que l’on venait écouter de la capitale à deux heures de route de montagne. Cecil Lloyd Knott (Spanish Town, Jamaïque, 4 mars 1936) est né de l’union d’une mère musicienne qui avait étudié à l’école Juilliard avant d’épouser le révérend A. W. Scott, lui aussi pianiste et violoniste. Leur enfant avait deux ans quand on confia à son père un temple (sans doute pentecôtiste) à Port Maria. Cecil y apprit à jouer de l’orgue à soufflerie à pédale dès l’âge de quatre ans et, passionné, se plongea bientôt corps et âme dans l’art du piano, obtenant plus tard une licence en musique.

Quelques secondes suffisent pour reconnaître la classe internationale de ce pianiste au style à part. À l’âge de dix-sept ans il dirigeait déjà un groupe de dix musiciens à l’hôtel Tower Isle, à dix minutes de chez lui—et sans la permission de sa mère. Il y a joué toutes les semaines pendant cinq ans, parfois tous les soirs, jusqu’à ce que Frank Gaylord le directeur artistique américain de l’hôtel parle de lui à Henry Onorati, producteur chez 20th Fox, qui l’a invité à enregistrer à New York. Son jeu virtuose suggère une influence d’Errol Garner et de George Shearing, de pianistes romantiques comme Franz Listz et du gospel, mais son style était aussi personnel que mûr quand il enregistra Piano Patterns (1958) à l’âge de vingt-deux ans avec son trio — augmenté du célèbre batteur américain Panama Francis. En 1962 le jeune prodige et son bassiste Lloyd Mason furent engagés à nouveau, cette fois par Clement « Coxsone » Dodd, qui construisait alors son propre studio. Coxsone voulait réunir les meilleurs talents de l’île et une rencontre exceptionnelle entre les deux Lloyd, le saxophoniste Roland Alphonso et le génial tromboniste Don Drummond — deux futures légendes — eut lieu par miracle : le premier album de jazz jamaïcain enregistré sur place.

Arrivé en Jamaïque avec sa mère jamaïcaine à l’âge de deux ans, Roland Alphonso (12 janvier 1931, La Havane-20 novembre 1998, Los Angeles) avait appris le saxophone à l’École Industrielle de Stony Hill, au nord de Kingston. Il a rejoint l’orchestre d’Eric Deans en 1948 et participé à différentes formations dans le circuit des hôtels avant d’enregistrer du mento dès 1952 pour le producteur débutant Stanley Motta31. Il a rejoint Clue J and the Blues Blasters en 1959 et gravé plusieurs disques de rhythm and blues « shuffle » populaires publiés sur la marque ND par Clement Dodd (Studio One)32. Saxophoniste n°1 du pays, Alphonso était capable de jouer des saxes alto, ténor, baryton et maîtrisait aussi la flûte. Dès 1960 il enregistra du rhythm and blues pour les producteurs Duke Reid, Lloyd Daley et King Edwards mais c’est en 1962 qu’il put enfin enregistrer du jazz pour Coxsone Dodd, un passionné de jazz comme lui.

L’album de standarts I Cover the Waterfront avec Cecil Lloyd et Don Drummond visait à réaliser le meilleur album de jazz local possible. Comme Alphonso, Don Drummond deviendrait un géant de la musique jamaïcaine. Membre fondateur des Skatalites comme lui, compositeur très inspiré et prolifique, le tromboniste enregistra un grand nombre de disques avant son enfermement à l’asile psychiatrique de Bellevue en 1965. Donald « Don » Drummond (Jubilee Hospital, Kingston, 12 mars 1932-Bellevue Asylum, Kingston, 6 mai 1969) avait commencé sa carrière dans l’orchestre de jazz d’Eric Deans vers 1949 après avoir étudié assidûment le trombone à l’Alpha School. Après son passage dans l’orchestre de Roy Coburn, Drummond fut un visionnaire à la forte personnalité, changeante et imprévisible. George Shearing le décrit comme « l’un des cinq meilleurs trombonistes au monde ». Il fut l’un des premiers musiciens professionnels à se convertir au Rastafari, bientôt rejoint par de nombreux collègues. C’est peut-être auprès du rasta Count Ossie qu’il se rapprocha de cette nouvelle culture marquée par le Jamaïcain Marcus Garvey.

RICO RODRIGUEZ, WILTON GAYNAIR, COUNT OSSIE ET LE JAHZZ

Après la destruction du Pinnacle, la communauté rasta rurale fondatrice, par la police de Bustamante en 1959, des centaines de rastafariens ont afflué vers l’ouest de Kingston, près de Trench Town où le mouvement fit tâche d’huile. Drummond et d’autres jazzmen participaient alors à des séances d’improvisation avec le groupe de tambours rastas de Count Ossie (Oswald Williams, St. Thomas, Jamaïque, 1926-18 octobre 1976). Fondée en 1948 sur la colline de Wareika dans l’est de Kingston, cette formation exceptionnelle mélangeait l’héritage du jazz moderne à des tambours aux racines bantoues utilisés dans des cultes jamaïcains anciens comme le kumina. Ce style de tambours était appelé buru en Jamaïque, puis nyabinghi par les rastas. La musique de Count Ossie a mûri dans un anonymat confiné à son modeste « centre culturel » à l’est de la capitale. Dès le début des années 1950 Ossie réunissait certains des meilleurs instru-mentistes de Kingston lors de ces rencontres musicales mystiques, réduites à de petits comités en raison de l’exclusion de la société jamaïcaine dont souffraient tous les rastas. Véritables parias, ils furent les premiers à cristalliser de façon tangible un jazz fusionnant hard bop et tambours africains — une tempête dans le verre d’eau du Landerneau jamaïcain. Leurs premiers disques ont été gravés tardivement à partir de 1959 sur des 45 tours à la distribution jamaïcaine confidentielle (marques Prince Buster et Moodisc), puis sur quelques rééditions de la marque anglaise Blue Beat d’Emil Shalit dans les années 1960. Sur le plan du concept afro-jazz, les disques pionniers des tambours de Count Ossie dans les années 1960-70 restent sans doute plus convaincants que la plupart des expériences d’Art Blakey, Randy Weston ou même Ahmed Abdul-Malik, qui allaient dans le même sens à cette époque mais où la présence musicale africaine qu’ils revendiquaient était moins substantielle33. On peut entendre ici les premiers enregistrements de Rico Rodriguez (Emmanuel Rodriguez, La Habana, Oct. 17, 1934-London, Sept. 4, 2015), un tromboniste débutant formé à l’Alpha School par Don Drummond en personne, et Wilton Gaynair de retour au bercail.

Une anthologie de jazz jamaïcain serait incomplète sans le géant Ernest Ranglin (Manchester, Jamaïque, 19 juin 1932) et le légendaire saxophoniste ténor Tommy McCook (La Havane, 3 mars 1927-Rock Dale Hospital, Conyers, Georgia, États-Unis, 4 mai 1998). Exilé aux Bahamas en 1954 après une carrière locale difficile, McCook a découvert John Coltrane à Miami et a décidé de travailler dans cette direction. Revenu à Kingston en 1962, il a refusé la proposition de Coxsone Dodd d’enregistrer du rhythm and blues. Dodd lui proposa un véritable album de jazz local, toujours avec Cecil Lloyd et son bassiste Lloyd Mason mais aussi avec le trom-pettiste Billy Cooke, Roland Alphonso, Don Drummond et l’immense guitariste Ernest Ranglin. Ranglin avait apprit les rudiments de la guitare avec deux oncles et était devenu autodidacte jusqu’à ce qu’un violoniste lui enseigne la lecture. Il rejoint l’orchestre de Val Bennett en 1947, puis celui d’Eric Deans. Il rencontra alors Monty Alexander, avec qui il s’intéressa au jazz, enregistra du rhythm and blues puis du jazz-mento34. Enregistré en 1962, le splendide album Jazz Jamaica marquait la première collaboration Drummond-Alphonso-Ranglin-McCook et Lloyd Knibb, des géants qui ne se quitteraient plus et enregistreraient peu après quantité de disques de ska pour finalement former les fantastiques Skatalites deux ans plus tard.

Bruno Blum, octobre 2015.

Merci à Olivier Albot, Clement Seymour Dodd, Mick Jagger, King Stitt, Lloyd Knibb, Chris Carter, Pascal Olivese et « Dizzy Johnny » Moore.

© FRÉMEAUX & ASSOCIÉS 2016

1. Le trompettiste des Skatalites « Dizzy » Johnny Moore à l’auteur, Kingston, 1995.

2. Ned Sublette, The World That Made New Orleans – From Spanish Silver to Congo Square (Chicago, Lawrence Hill Books, 2008).

3. Lire le livret et écouter « Po’ Drapeaux » sur Haiti - Vodou - Folk Trance Possession Rituals 1937-1962 (FA5626) ou Roots of Funk 1947-1962 (FA 5498) dans cette collection. On retrouve un rythme ternaire analogue sur les enregistrements de kumina jamaïcain « Po’ Stranger », « Bongo Man » et « Kongo Man, Delay » sur l’album Jamaican Ritual Music (Lyrichord LLST 7394).

4. Lire les livrets et écouter Haiti - Meringue & Konpa 1952-1962 (FA 5615), Dominican Republic - Merengue 1949-1962 (FA 5450), Biguine valse et mazurka créoles 1930-1943 (FA 027), Biguine, l’âge d’or des cabarets antillais de Paris 1939-1940 (FA 007), Stellio - intégrale 1929-1931 (FA 023) et Ernest Léardée - Rythmes des Antilles 1951-1954 (FA 5177) dans cette collection.

5. Lire le livret et écouter Roots of Funk 1947-1962 (FA 5498) dans cette collection.

6. Lire le livret et écouter Voodoo in America 1926-1951 (FA 5375) dans cette collection.

7. Lire le livret et écouter Dominican Republic - Merengue 1949-1962 (FA 5460) et Mambo - Big Bands 1946-1957 (FA 5210) dans cette collection.

8. Lire Bruno Blum, Le Rap est né en Jamaïque (Le Castor Astral, 2009).

9. Lire le livret et écouter Swing Caraïbe - Premiers jazzmen antillais à Paris 1929-1946 (FA 069) dans cette collection.

10. Une grande partie de l’œuvre de Louis Armstrong est disponible dans cette collection.

11. Lire Milton « Mezz » Mezzrow Really the Blues (1946), Citadel Underground, 2001 (édition française : La Rage de vivre, Buchet Chastel 2013)

12. Lire Hélène Lee, Le Premier Rasta (Flammarion, 1999).

13. Écouter « Sly Mongoose » enregistré à New York le 26 septembre 1952 dans l’Intégrale Charlie Parker publiée dans cette collection. Gravée à New York en 1923, la version de Lionel Belasco est disponible sur Goodnight Ladies and Gents (Rounder CD 1138).

14. Extrait de l’autobiographie de Duke Ellington, Music Is my Mistress (Doubleday, Garden City, N.Y., 1973, p. 108).

15. Écouter Black British Swing (Topic, 2001) et lire leur histoire dans le livret.

16. Mick Jagger à l’auteur, Londres, 1980.

17. Lire le livret et écouter Jamaica - Folk Trance Possession 1939-1961, Mystic Music From Jamaica - Roots of Rastafari (FA 5384, coédité par le musée du Quai Branly) dans cette collection.

18. Lire le livret et écouter Trinidad-Calypso 1939-1959 (FA 5348) dans cette collection.

19. Lire le livret et écouter le volume Calypso du coffret L’Anthologie des Musiques de Danse du Monde (FA5342) dans cette collection, qui réunit des enregistrements de calypso d’artistes non-trinidadiens.

20. Écouter Jamaica - Mento 1951-1958 (FA 5275) dans cette collection.

21. Retrouvez Lord Fly, Lord Flea, Harold Richardson, Hubert Porter, Bertie King, Ernest Ranglin et Wilton Gaynair sur Jamaica - Mento 1951-1958 (FA 5275) dans cette collection.

22. Des morceaux choisis de calypso « international », diffusé à l’extérieur de Trinité-et-Tobago sont réunis dans le volume Calypso du coffret L’Anthologie des Musiques de Danse du Monde (FA 5342) dans cette collection.

23. Lire les livrets et écouter Jamaica-USA Roots of Ska 1942-1962 (FA 5396) et Race Records - Black rock music forbidden on U.S. Radio 1942-1962 (FA 5600) dans cette collection.

24. Klive Walker, Dubwise: Reasoning from the Reggae Underground (London, Ontario, Canada: Insomniac Press, 2006).

25. Lire le livret et écouter USA Jamaica - Roots of Ska 1942-1962 (FA 5396) dans cette collection.

26. Lire Alan Robertson Joe Harriott - Fire in his Soul (édition révisée : Northway, Londres, 2011).

27. Écouter Bahamas - Goombay 1951-1959 (FA 5302) dans cette collection.

28. Lire le livret et écouter USA-Jamaica - Roots of Ska 1942-1962 (FA 5396) dans cette collection.

29. Retrouvez Lance Hayward sur Bermuda - Gombey & Calypso 1953-1960 (FA 5374) dans cette collection.

30. Extrait de Le Reggae par Bruno Blum (Le Castor Astral 2010).

31. Lire le livret et écouter Jamaica - Mento 1951-1958 (FA 5275) dans cette collection.

32. Lire le livret et écouter Jamaica - Rhythm and Blues 1956-1961 (FA 5358) dans cette collection.

33. Retrouvez Ahmed Abdul-Malik, Art Blakey et Count Ossie avec le saxophoniste américain Bill Barnwell (et non Harriott) dans Africa in America - Rock, Jazz & Calypso 1920-1962 (FA 5397) dans cette collection.

34. Retrouvez Ernest Ranglin sur Jamaica - Mento 1956-1958 (FA 5275) et Jamaica - Rhythm & Blues 1956-1961 (FA 5358) dans cette collection.

Jamaica - Jazz 1931-1962

by Bruno Blum

“This was before the days of rock and roll. Jazz was the thing. If you didn’t play jazz, you didn’t play anything.”

— “Dizzy” Johnny Moore1

Jamaica is situated close to the American continent and its jazzmen grew up in a very similar African-American culture to that of their more famous U. S. colleagues. However, the best Jamaican musicians did not go down in jazz history. They were excluded from stardom because of their restricted number and their nationality — not because of a lack of talent. In London and New York alike, the social consequences of their exile increased the trouble they had getting recognition and assimilating into a tough jazz world. Apart from the founders of The Skatalites, who later contributed to many ska and reggae recordings (including with Bob Marley), the greatest Jamaican jazzmen were never appreciated as much as they deserved to be. Their works are as little-known as they are remar-kable; to jazz fans who discover them, they blow like a cool breeze, a good surprise.

This set aims at their rehabilitation; at giving these musicians the long-overdue status that ought to be theirs in jazz historiography. Connoisseurs can’t go wrong when listening to Joe Harriott’s fascinating virtuosity. A visionary bopper and free jazz pioneer, even Harriott’s hard and erratic life in exile can hardly explain how such a talent could remain out of jazz’s pantheon for so long. The same goes for guitar player and arranger Ernest Ranglin’s quirky style, which has been around since the 1940s — as well as the dazzling playing by Wilton Gaynair, Cecil Lloyd or Dizzy Reece, whose very names remain mostly unknown to many jazz experts.

And what could be said of Count Ossie’s extraordinary Rastafarian drum ensemble which, for the first time in jazz history, truly crystallized a deep fusion between hard bop, blues and Bantu roots?

Not to mention jazzmen Roland Alphonso, Don Drummond and Tommy McCook, who played with Count Ossie, and stood amongst the creators and giants of ska in 1961- 65 — which soon led to rocksteady and reggae.

Their early recordings were conceived as a contribution to modern jazz, a style they fanatically loved, as did their famous producer and ska founder, Clement Seymour “Coxsone” Dodd (Studio One). Gathered here for the first time is an orderly compendium of these important and savoury records, all but a few much neglected — and hard to find.

JAZZ WAS BORN IN THE CARIBBEAN

Jazz music has always been celebrated as a U.S. creation in a historiography that is itself also from the United States. However, to be precise, jazz music is rather a product of an Afro-Creole culture; a mix of African and European elements merged into a new culture that is distinct from the other two. This paradigm is peculiar to the Caribbean and is not limited to the United States. New Orleans, the cradle of jazz in the U.S.A., is a fine example of this fundamental “creoleness”. To the point that Ned Sublette called it “The Caribbean capital city.”2 Isolated away from the continent by large swamps, the Crescent City faces the Caribbean Sea, on the Mississippi, which, for centuries, was the main access way to the vast continent inland. It was on New Orleans’ boats that jazz and jazzmen spread northward. A great Caribbean port, New Orleans has a similar social and racial background to the neighbouring islands. Caribbean slaves also left a tremendous mark on its culture, as they were massively deported there throughout the Nineteeth Century (due to geopolitical disruption in Cuba, revolution in Haiti, etc.).

This Caribbean input, with Ibo, Akan, Yoruba, Bantu and other roots, has strengthened the great wealth of music and dance sessions that took place in the heart of New Orleans, at Congo Square. Several different ethnicities and Caribbean Afro-Creole cultures shared this space and competed in what was, in slavery days, a unique musical melting pot on the American continent.

This historical fact is evidence that U.S. jazz roots are deeply Afro-Creole/Caribbean. We can then assume that swing rhythms, which are specific to American jazz, and which Art Blakey described as being a U.S. creation, really have deep roots in rhythms from Jamaica, or Haitian voodoo inherited from way older Bantu tradi-tions3. Such rhythms were often applied to European melodies4. Since at least the Nineteenth Century, “creo-lisation” of European musics was the norm in the Black ghetto streets of New Orleans, as well as all of the Caribbean, and has never ended since5. Thus the history of Louisiana’s influential popular music and certainly that of all of the North American continent cannot be separated from their Afro-Caribbean legacy.

U.S. and Caribbean musics are different but analogous, and an obvious parallel can be drawn between the two, as exemplified by precious recordings made in the 1920s by mulatto Trinidadian Sepharadic Jews, Sam Manning (1899-1961), who worked for a long time with Amy Ashwood Garvey (politician Marcus Garvey’s first Jamaican wife) and Lionel Belasco (1881-1967).

As they entered the Louisiana gate, Caribbean people — mostly Cuban and Haitian but also Jamaican, Trinidadians, etc. — never ceased to spread their decisive musical legacy over the American continent, where African-rooted elements were way more discreet, as for centuries the law had severely cracked down on them. New Orleans’ exception to this enabled them to massively import very influential rhythms onto the continent, as well as Caribbean melodies, including calypso (Trinidad and Tobago), troubadour, rumba (Cuba) and mento (Jamaica) styles. A whole set of cultural elements were taken along, including the use of drums, which, if one excepts military drums, were by law forbidden on all of the continent except New Orleans. Caribbean people were fed with a legacy of animist trances deeply rooted in voodoo (Haiti), kumina (Jamaica), and, in Cuba, santería, sacred music from the lucumí orishas (yoruba), the Abakuà secret society of the Carabalí (Calabar), etc. These Afro-Creole elements lay at the root of slave spirituals, which in turn would eventually evolve into Twentieth Century gospel songs in the Caribbean, as well as on the continent. Caribbean musicians were always there in the United States (voodoo/hoodoo6). The roots of jazz improvisation should be looked for in the unintelligible vocal expression heard during such trances (speaking in tongues was inspired by the spirits of the dead or, in some rituals, by the Holy Ghost, etc.). The Caribbean diaspora later created essential styles such as salsa7 and rap music, both descended from Caribbean matrixes8. In return, American musicians circulated in the Caribbean. With the advent of 78 rpm records between the two World Wars, the jazz influence became significant. By 1935, the swing trend had strongly increased jazz’s international impact.

JAMAICA IN AMERICA

The early spread of Trinidadian calypso (recorded as early as 1914) and American jazz records in the 1920s massively hit the Caribbean. These sophisticated musics came from Creole cultures very much like their own, and many Caribbean people felt like they wanted to belong to this pan-Caribbean wave. Some chose jazz as a vector of exile, an incentive to leave, to seek communication with jazz icons such as Louis Armstrong9. And, much like Haitians, Domi-nicans and Cubans, Jamaicans always tried to emigrate for economic reasons. The Jamaican diaspora moved to Miami, Toronto and New York, where the great Jamaican political leader Marcus Garvey dwelled (until getting deported back home in 1927). Garvey’s essential, inter-national UNIA Black nationalist organi-sation contributed to Harlem’s cultural renaissance between the two World Wars. Jamaican musicians were present in the early, crucial stages of jazz development in New York’s 1900s. Tons of hemp from Jamaica was also being smoked in Harlem.

In their own way they helped to shape jazz as played by reefer-loving musicians10. In the 1940s and 1950s much of this herb was likely being exported from the important Pinnacle community in Sligoville (Jamaica), which was led by Rastafari movement founder, Leonard Howell. An adventurer who used plant-based medicine, Howell had lived in Harlem for years, where he’d soaked in Garvey’s influential, pan-Africanist ideas. Musicians in New York were well aware of this Caribbean presence, as shown by recordings such as “St. Thomas” by Son-ny Rollins (1956) and Charlie Parker’s “Sly Mongoose” (1952), a Jamaican mento classic first recorded in 1923 by Lionel Belasco. A Trini-dadian with a Sepharadic Jewish father, jazz and calypso pianist Belasco recorded many times in New York City. In fact, that’s where he led one of the first Black jazz groups ever recorded (September, 1918) — Caribbean jazz.

In his autobiography, Duke Ellington had this to say about his famous trombone player, Joe “Tricky Sam” Nanton:

“What he was actually doing was playing a very highly personalized form of his West Indian heritage. When a guy comes from the West Indies and is asked to play some jazz, he plays what he thinks it is, or what comes from his applying himself to the idiom. Tricky and his people were deep in the West Indian legacy and the Marcus Garvey movement. A whole strain of West Indian musicians came up who made contributions to the so-called jazz scene, and they were all virtually descended from the true African scene11”.

BLACK BRITISH JAZZ

According to Jamaican historian Daniel McNeely, American artists played Kingston at least as early as the 1910s, notably at the Ward Theater. They did minstrel shows and played in styles associated with Ame-rican jazz. Before moving to the U.S.A. Marcus Garvey also organized a few gigs. This suitably impressed a few emulators, including alto sax player Louis Stephenson (born 1907), Leslie “Jiver” Hutchinson, Leslie Thom-pson and Joe Appleton.

In 1924 their band won First Prize in a competition and flew to London to play in a Wembley “British Empire Show” for six weeks. Several American musicians visiting Jamaica recruited local talent to back them and sometimes took them on tour, even as far as Europe. The most reno-wned swing orchestra in Britain was Ken “Snakehips” Johnson’s, who’d invented the shimmy dance (similar to the Haitian voodoo zépaules dance) before going home to Guyana in 1932. He came back to become a tap dancer, leading a group and travelling on three continents with it. Jamaican trumpet player Leslie Thompson was a dedicated follower of Marcus Garvey and formed an all-Black band. He’d moved to Britain, and contributed to Spike Hughes’ band, as heard here on Tap Your Feet (1931) before playing with Louis Armstrong in 1934. He then joined and led Snakehips Johnson’s group, which featured more Jamaicans: trumpet player Leslie George “Jiver” Hutchinson (March 6, 1906 - Nov. 22, 1959), York de Souza (piano), Louis Stephenson (alto sax, clarinet), Joe Appleton (sax) and local celebrity Bertie King (clarinet, alto and tenor saxes). This Black group played downtown’s Cuba Club (which was to become Ronnie Scott’s in Soho’s Gerrard Street), and the Frisco and Panama, where Jamaican cooks and dockers from the working class East End came. Spike’s other musicians were South African, Caribbean or Afro-British12.

In 1935, clarinet/sax player Bertie King moved to Europe, toured with Coleman Hawkins, then recorded three tracks with Django Reinhardt and Benny Carter in Paris. Born in Panama, Albert “Bertie” King (1912-1981) was raised in Kingston, Jamaica. Like many top players here, including Don Drummond, Rico Rodriguez, Dizzy Reece, Joe Harriott, Tommy McCook and Harold McNair, he had studied at the Roman Catholic Alpha Boy’s School where manager Sister Ignatius collected jazz records. He then formed Bertie King and the Rhythm Aces with his friends, “Jiver” Hutchinson, Louis Stephenson and York de Souza, playing a mix of mento and jazz, recording with Snakehips and Jiver’s groups before joining the Royal navy. He was back in 1944 recording with De Souza, Jiver and Joe Appleton.

The Flamingo Club opened in 1952 in a Coventry Street basement in Soho (moving to 33 Wardour St. in 1957). It soon became one of London’s foremost African-American and Caribbean music clubs. Jamaican jazz and R&B (which were to merge as ska in 1961) musicians such as Joe Harriott played in this shady club, where the upcoming 1960s mod culture was brewing. Billie Holiday, Ella Fitzgerald and Sarah Vaughan sung there; The Flamingo was attended by true jazz lovers wearing a compulsory tie. Its influence was immense. It would later become a haven for rock musicians such as The Beatles and Jimi Hendrix. One night, jazz drummer Charlie Watts took the Rolling Stones’ singer-to-be to his first ever gig:

“I’ve been listening to ska for years! It was the first music I ever saw being played onstage! At the Flamingo Club… it was Prince Buster with Georgie Fame, around 1958… […] I started dreaming I would become as famous as Georgie Fame.”13

In Jamaica the British colonial society fed itself on European and American music. It scorned Jamaican folk music (both animist rituals and Christian14). Danceable and popular, local mento included risqué tunes with sexual hints (Donkey City, Iron Bar, Dry Weather House). It was considered as vulgar and boring indigenous music by the White class in authority.

Mento was different from Trinidadian calypso15. Some urban mento artists did play partially white crowds in cabarets, but with its international reputation, American jazz was the only form of Black music reaching both high society and the Black underprivileged. After playing with various artists, including Nat Gonella (a Louis Armstrong imitator), Bertie moved to Jamaica in 1951 and formed a mento band. Trinidadian calypso was getting trendy and he hoped to get work in hotels and cabarets in the new booming tourism business. He was one of the first musicians to record on the island, leading sessions in beginner, Sepharadic Jewish producer Stanley Motta’s tiny makeshift studio. There, he backed several mento singers on the clarinet, including Harold Richardson & the Ticklers, Hubert Porter and the Tower Islanders. It is more than likely that he was the one who put Motta in touch with Emil Shalit of Melodisc (and soon Blue Beat) Records in London. Eight ten-inch vinyl mento albums and around five singles were issued there on Melodisc in 1954-57. Made in the U.S.A. or England, mento records were sold in Jamaican hotels where mento artists played16.

King returned to London several times, playing with the likes of Chris Barber and Kenny Baker. He toured Asia and Africa before leading the Jamaica Broadcasting Corporation (Radio JBC) house band, which featured Ernest Ranglin. He also recorded with John “Dan” Williams’s (reggae and disco star Grace Jones’ grandfather’s) band.

Dan Williams’ sax player was Rupert Lyon, a jazz musician who, like King, was tired of exile. Lyon became a mento singer as Lord Fly. Mento had been popular in Jamaica for at least two decades but it was only recorded as from 1949 or 1950. Born in 1905 in Lucea, Jamaica to a musical family, Lyon had worked in New York for years in the 1920s, then in a rumba group in Cuba before singing in Hugh Coxe’s urban “calypso” group in Jamaica, performing for American soldiers during WWII. A dance band veteran (he sung for George Moxey’s band, too), Lyon also surfed the calypso wave17. The Kingston Colony Club manager then dubbed him Lord Fly. His remarkable instrumental version of Donkey City is probably the oldest recording of pure Jamaican jazz. Sugar Belly, who made his own awesome “bamboo saxes” with bamboo, cardboard and cellotape, ought to be remembered, too. In spite of a bit of distortion on Alerth Bedasse’s voice, Chin’s Calypso Sextet’s ultra rare 78 rpm record is included here, displaying a much older tradition of Jamaican wind instruments at the true root of jazz.

JOE HARRIOTT, WILTON GAYNAIR, DIZZY REECE & HAROLD McNAIR IN EXILE

The first professional jazz ensembles (Rhythm Raiders, King’s Rhythm Aces) emerged in Jamaica in the early 1930s and entered competitions. Milton McPherson was a pre-war celebrity. Whylie Lopez, George Alberga and Ivy Graydon’s swing groups performed jazz mainly for White society. In the early 1950s, Don Drummond, Tommy McCook, Wilton Gaynair, his brother Bobby and Harold McNair played in Sonny Bradshaw’s and Eric Dean’s orchestras, as well as Roy Coburn’s Blue Flames, who enjoyed fame amongst Black people, too. ZQI was the only local radio and it did not play jazz.

Radio owners (including some bar owners) turned to Ame-rican radio (Armed Forces Radio Service), the BBC, New Orleans stations, WLAC in Nashville and WINZ in Miami18, which sometimes played some blues and jazz. According to historian Klive Walker:

“The ‘40s generation of jazz musicians who did not attend Alpha School included trumpet players Sonny Grey, Roy Burrowes, and Sonny Bradshaw; guitarist Ernest Ranglin; tenor saxophonists Andy Hamilton and future Skatalite Roland Alphonso. Whether they were Alpha graduates or non-Alpha alumni, they all possessed the skills to succes-sfully negotiate the difficult terrain of bebop, the new and complex, post-war jazz created by Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie. Like the previous generation of jazz musicians, these Jamaican bebop artists eventually looked beyond the island’s shores as a way to mature their artistry and advance their careers.”

Tommy McCook went to play in the Bahamas in 1954 and did not come back until 1962. In the post-war years Wilton Gaynair, Grey, Burrowes, Reece and Joe Harriott left for good. Out of those new expatriates, Harriott (who’d studied at Alpha amongst Gaynair, McNair and McCook), is probably the most important player.

He started out in two of the leading post-war Jamaican orchestras, namely Eric Deans’ and Sonny Bradshaw’s, and in the late forties was several times offered a chance to play for music promoter Count Buckram. Harriott reached London as part of Ossie DaCosta’s group, toured with him and stabilized himself in the British capital city in 1951. He started recording in 1954, cutting his composition Ackee Blues (ackee is the Jamaican national vegetable) with high-life musicians in a rhythm and blues style that was popular in Jamaica at the time19. Like Sonny Stitt and other alto sax players at the time, Harriott was steeped in Charlie Parker’s innovative style, as heard in his performance of Cherokee — probably the best one after Parker’s famous versions. All through the 1950s, the excellent Harriott’s dazzling technique and creativity made him probably the greatest jazz artist on the British scene.

He played in groups with Pete Pitterson, Ronnie Scott and Tony Kinsey and enjoyed support from some of the best British musicians, including Bill LeSage and Phil Seamen. His 1959 album, Southern Horizons, was recorded with the no less excellent Jamaican bass player Coleridge Goode, who stayed with him for years — but with little success, in spite of the quality of their work. The triumphs and tragedies of Joe Harriott’s life are told in an epic biography.20

Nicknamed Bogey (as in bogeyman, i.e. sax wizard), tenor saxman Wilton “Bra” Gaynair (Jan. 11th, 1927, Kingston - Feb. 13th, 1995, Germany), is another forgotten legend of Jamaican hard bop. Like his brother Bobby (who recorded with Clue J & the Blues Blasters) he’d met Harriott, McNair and Drummond at Alpha Boys School for the under-privileged, where music was thoroughly studied. After his debut in Kingston clubs, he played with celebrities such as George Shearing and Carmen McRae when they visited Jamaica. He then exiled himself in Germany following a tour with Dizzy Reece’s band. He seldom recorded (only three albums to his name) in spite of his indisputable talent. All three tracks here are taken from Blue Bogey, his bright first album, recorded in London. Back in Kingston, Bogey contributed to Count Ossie’s debut sessions for beginner producer Harry A. Mudie. He would eventually play with Freddie Hubbard, Gil Evans, Shirley Bassey, Horace Parlan, Manhattan Transfer, Bob Brookmeyer, Mel Lewis, and so on.

Other musicians, including Sonny Grey and Noel Gillespie, went into exile. An alto, tenor sax and flute player, Harold McNair (Kingston, Nov. 5th 1931-Maida Vale, London, March, 1971), a.k.a. “Little G”, was another Jamaican musician of repute, and a friend of Joe Harriott’s. They’d studied at Alpha together and played in Baba Motta’s group with Wilton Gaynair. After playing a part in the film Island Women (1958), he became a goombay-calypso singer for a debut album recorded in the Bahamas21. He left for London in 1960 after a European tour in Quincy Jones’ orchestra and a few film soundtrack recordings made in Paris. He can also be heard playing in the film All Night Long on the first version of “Peggy’s Blue Skylight” with the Charles Mingus quartet.

A Ronnie Scott’s club regular, he recorded some hard bop there (some of which are included here) while sharing the bill with Zoot Sims. He then returned to the Bahamas and later recorded more quality jazz.

In 1958, Joe Harriott got pneumonia and pleurisy. It was during a three and a half months’ stay in hospital at the end of the year that he conceived his first album as a leader, choosing a more abstract direction than hard bop. Following various splendid recordings (including a frantic version of Caravan featuring a bongo solo by Frank Holder) Harriott was at the cutting edge of American jazz’s latest developments. He’d read an Ornette Coleman (who was also a Charlie Parker disciple) interview and was aware of his new direction but had not heard his records. The masterpiece Southern Horizons was cut in 1960, making Joe Harriott the indisputable pioneer and master of what came to be known as European free jazz — through lack of a more accurate term. Abstract and Impression are both taken from it.

DON DRUMMOND, CECIL LLOYD, BILLY COOKE, TOMMY McCOOK, ERNEST RANGLIN & ROLAND ALPHONSO: JAZZ IN JAMAICA

In 1954, several major jazz shows took place in Kingston’s Ward Theater. Local infatuation with jazz was strengthened by the development of sound systems (dance parties to the sound of records22), which multiplied. Several new artists emerged then, including the singer Totlyn Jackson (born in 1930 in Port Maria, Jamaica). She recorded one song as a guest on the debut album by Lance Hayward, a blind pianist from the Bahamas who’d come to play a season at the Half Moon Hotel in Montego Bay23. This Old Devil Moon performance was featured on the very first album released on the Island label, a new company founded by the future great Jamaican producer Chris Blackwell (U2, Bob Marley, etc.). Following the usual local pattern,Totlyn had been raised by her mother in a religious (presbyterian) mode with her brother and two sisters. She sang gospel early on and got into jazz after hearing Tim Barnet and Eric Dean’s groups.

Jamaica is a country where, according to Robbie Shakes-peare, “People love music more than other people.” The country has produced many remarkable musicians, who never had the career their talent deserved. Coming from the isolated, seaside village of Port Maria, situated in a wild part of the island, Cecil Lloyd is one of these unknown magicians. Known locally as a ‘genius,’ people from King-ston would drive for two-hours on mountain roads to hear him. Cecil Lloyd Knott (born in Spanish Town, Jamaica, March 4th, 1936) had a musician mother who’d studied at Juillard’s school before marrying Reverend A. W. Scott, himself a pianist and a violin player. Cecil was two years old when a Port Maria temple (likely a pentecostal one) was entrusted to his father. It was there that, starting as early as four years old, Cecil learned to play a pedal wind-organ and soon passionately switched instruments, immersing himself body and soul in the art of piano, later obtaining a music degree.

Only a few seconds are needed to recognise the international league this pianist belongs to, with a style of his own. At the age of seventeen he was leading a ten-piece group at the Tower Isle Hotel, ten minutes away from his home — and without his mum’s permission. He played there for five years, sometimes every night, until the hotel’s artistic director mentioned his name to Henry Onorati, a music producer at 20th Century Fox, who invited him to record in New York City. His virtuoso playing suggests influences such as Errol Garner and George Shearing, as well as Franz Listz and gospel, but his style was as fully mature as it was original when he recorded Piano Patterns (1958) at the age of twenty-two, backed by his own trio — plus Panama Francis, a famous American drummer. By 1962, the young prodigy and his bassist Lloyd Mason were recording again, this time for Clement “Coxsone” Dodd, then building his own studio. Coxsone wanted to gather the best talents on the island and the miracle happened: an outstanding session took place with the two Lloyds, sax master Roland Alphonso and the trombone genius Don Drummond: the first ever Jamaican jazz album recorded locally.

Roland Alphonso (La Habana, Jan. 12th, 1931 - Los Angeles, November 20th, 1998) arrived in Jamaica with his Jamaican mother at the age of two. He studied the saxophone at the North Kingston Stony Hill Industrial School and joined Eric Deans’ orchestra in 1948. He played in various bands on the hotel circuit and recorded some mento for producer Stanley Motta in 1952. He then joined Clue J and the Blues Blasters in 1959, and recorded several ‘shuffle’ rhythm and blues tunes issued on Coxsone Dodd’s ND Records (Studio One). Alphonso was the number one sax player on the island. He could play alto, tenor and baritone saxes and also mastered the flute. He recorded some R&B for producers Duke Reid, Lloyd Daley and King Edwards as early as 1960, before he was able to finally cut some jazz for Coxsone Dodd, who was, like him, a jazz enthusiast.

Done with Cecil Lloyd and Don Drummond, the I Cover the Waterfront album aimed at being the best possible local jazz recording. Like Alphonso, Drummond was to become a Jamaican music giant. A Skatalites founder member like him, an inspired and prolific composer, the trombonist made many records before his internment at the Bellevue psychiatric hospital in 1965. Donald “Don” Drummond (Jubilee Hospital, Kingston, March 12th, 1932 - Bellevue Asylum, Kingston, May 6th, 1969) had started playing in Eric Deans’ orchestra around 1949 after assiduously studying the trombone at the Alpha School. After a stint in Roy Coburn’s band, Drummond became a visionary with a strong personality, moody and unpredictable. George Shearing decribed him as “one of the five finest trombone players in the world.” He was one of the first professional musicians to convert to Rastafari, soon joined by several colleagues. It is perhaps alongside rasta musician Count Ossie that he first got closer to this new culture, marked by Jamaican politician Marcus Garvey.

RICO RODRIGUEZ, WILTON GAYNAIR, COUNT OSSIE & JAHZZ

In 1959, after the destruction by Bustamante’s police of the Pinnacle, the rural, founding rasta community, hundreds of Rastafarians flocked to West Kingston, near Trench Town, from where their movement spread out. Drummond and other jazzmen participated in improvisation sessions with the Rastafarian drum ensemble led by Count Ossie (Oswald Williams, St. Thomas, Jamaica, 1926 - October 18th, 1976). Founded on the Wareika Hill in East Kingston, in 1948, this truly special group mixed the legacy of modern jazz with Bantu-rooted drums used in ancient Jamaican cults, such as the kumina. This drumming style was called buru in Jamaica, then nyabinghi by Rastafarians.

Count Ossie’s music matured in the anonymity of his modest East Kingston “cultural center.” From the early 1950s, Ossie managed to bring some of the best Kingston musicians to his mystical, musical encounters, which were limited to small attendances because of the intolerance and exclusion all Rastafarians suffered then. They were outcasts who first crystallised in a tangible way a style of jazz fusion, mixing hard bop and African drums — a storm in a glass of water, confined to the small world of the Jamaican musical underground. Their first records were recorded belatedly in 1959, on poorly distributed 45rpm singles records issued on the Moodisc and Prince Buster labels, and reissued in the 1960s on a few Blue Beat singles pressed in England by Emil Shalit. However, as an Afro-jazz concept, the pioneering 1960-70s records by Count Ossie remain perhaps more convincing efforts than most of those led by Art Blakey, Randy Weston and even Ahmed Abdul-Malik, who were all searching in the same direction at the time, but where the African musical dimension they claimed was less substantial24. Included here are the debut recordings by Rico Rodriguez (Emmanuel Rodriguez, La Habana, Oct. 17th, 1934 - London, Sept. 4th, 2015), a trombone beginner taught by Don Drummond himself at Alpha. Rico was joined in Count Ossie’s group by Wilton Gaynair, who’d just returned home.