- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

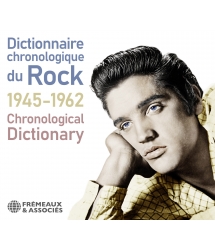

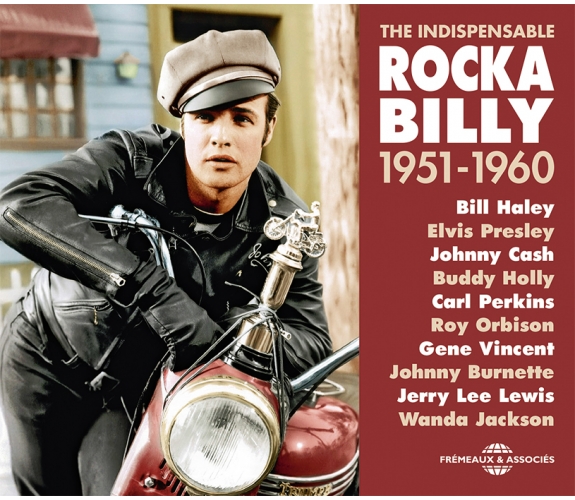

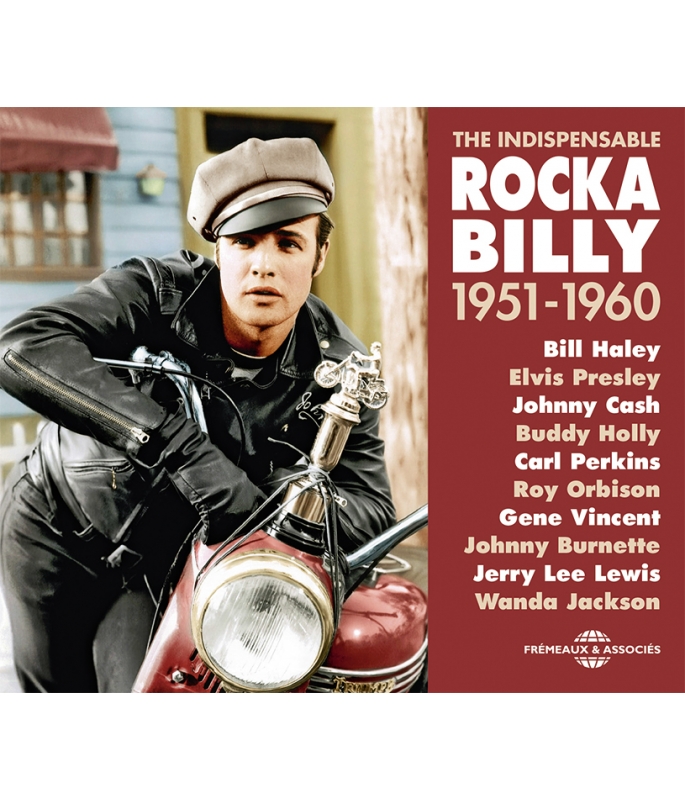

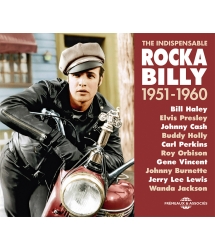

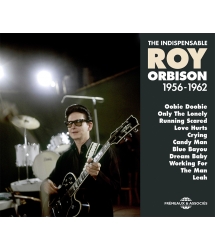

ELVIS PRESLEY, BILL HALEY, ROY ORBISON, GENE VINCENT,…

Ref.: FA5423

Artistic Direction : BRUNO BLUM

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Total duration of the pack : 3 hours 11 minutes

Nbre. CD : 3

ELVIS PRESLEY, BILL HALEY, ROY ORBISON, GENE VINCENT,…

ELVIS PRESLEY, BILL HALEY, ROY ORBISON, GENE VINCENT,…

Rockabilly derives from bluegrass, country boogie and the African-American rock ‘n’ roll genre, borrowing much from the latter. Its rise coincided with rock’s early popularity with a mass audience. Intense, incomparable and spirited, rockabilly is a style apart, defined by an aesthetic of great purity that is both simple and efficient. It was an emblem in 1950s America and the legendary recordings forming its foundations had exceptional quality. They were so influential that they led to several resurrections. Compiled and annotated by Bruno Blum, this set’s recordings represent the cream of original rockabilly in an essential anthology. Patrick FRÉMEAUX

ROCK COUNTRY JAZZ BLUES R&B (1935-1962)

EDDY MITCHELL, JOHNNY HALLYDAY, DICK RIVERS…

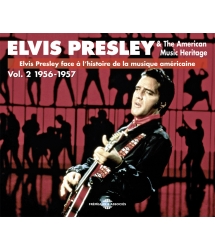

ELVIS PRESLEY & THE AMERICAN MUSIC HERITAGE...

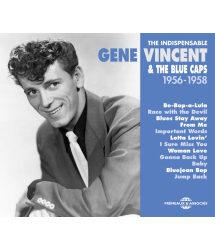

THE INDISPENSABLE 1956-1958

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Rocket 88Bill Haley And The SaddlemenJackie Brenston00:02:331951

-

2Rock The JointBill Haley And The SaddlemenCrafton00:02:151952

-

3Hound DogBill Haley And The SaddlemenJerry Leiber00:02:221953

-

4That's All RightElvis PresleyArthur Crudup00:01:591954

-

5Just BecauseElvis PresleySidney Robin00:02:361954

-

6Good Mornin' TonightElvis PresleyRoy Brown00:02:161954

-

7Drinkin' Wine Po Dee O DeeMalcom YelvingtonHenry Mcghee00:02:521954

-

8Baby Let's Play HouseElvis PresleyArthur Gunter00:02:191954

-

9Cry! Cry! Cry!Johnny CashJonnhy Cash00:02:301955

-

10Mystery TrainElvis PresleyHerman Parker00:02:311955

-

11Folsom Prison BluesJohnny CashJonnhy Cash00:02:501955

-

12Everybody Needs A Little LovinMerle KilgoreDorothy Lee Salley00:02:071955

-

13Whole Lotta Shakin Goin' OnRoy HallMabel Smith00:03:001955

-

14Rockin' And Rollin'Sonny FischerSonny Fischer00:02:041955

-

15Love MeBuddy HollySue Parrish00:02:081955

-

16Blue Suede ShoesCarl PerkinsCarl Perkins00:02:201955

-

17Honey Don'tCarl PerkinsCarl Perkins00:02:521955

-

18Sleepy Time BluesJess HooperJess Hooper00:02:211955

-

19Mama's Little BabyJunior ThompsonQuinton Claunch00:02:221956

-

20Raw DealJunior ThompsonQuinton Claunch00:02:141956

-

21Midnight ShiftBuddy HollyJimmy Ainsworth00:02:131956

-

22Blue Days Black NightsBuddy HollyBen Hall00:02:061956

-

23Blue Suede ShoesElvis PresleyCarl Perkins00:02:031956

-

24Mr BluesMarvin RainwaterMarvin Rainwater00:02:281956

-

25Oobie DoobieRoy OrbisonAllen Richard Penner00:02:131956

-

26Go! Go! Go! Down The LineRoy OrbisonRoy Orbison00:02:101956

-

27Boppin' The BluesCarl PerkinsCarl Perkins00:02:511956

-

28Get RhythmJonnhy CashJonnhy Cash00:02:131955

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Rockin' Rollin StoneAndy StarFrank Delano Gulledge00:02:511956

-

2Rongue Ried JillCharlie FeathersCharlie Feathers00:01:591956

-

3Ping Peg SlacksEddie CochranEddie Cochran00:02:111956

-

4Duck TailJoe ClayRudy Grayzell00:02:311956

-

5Slipping Out And Sneaking inJoe ClayWes Williams00:02:111956

-

6Doggone ItJoe ClayWes Williams00:02:231956

-

7Sixteen ChicksJoe ClayL. Davis00:02:001956

-

8Read Headed WomanSonny BurgessAlbert Burgess00:02:101956

-

9Race With The DevilGene VincentGene Vincent00:02:081956

-

10Be Bop A LulaGene VincentGene Vincent00:02:381956

-

11Tear It UpJohnny BurnetteJonnhy Burnette00:01:561956

-

12Watchin' The 7:10 Roll ByBuck GriffinBuck Griffin00:02:371956

-

13Hot DogBuck Owens00:02:181956

-

14You Look That Good To MeJoe ClayClyde Otis00:01:371956

-

15Dixie FriedCarl PerkinsCarl Perkins00:02:281955

-

16Gonna Back Up BabyGene VincentDanny Wolf00:02:291956

-

17Twenty Flight RockEddie CochranEddie Cochran00:01:461956

-

18Train Kept A RollinJohnny BurnetteMyron C. Bradshaw00:02:171956

-

19All By MyselfJohnny BurnetteDave Bartholomew00:02:021956

-

20Honey HushJohnny BurnetteBig Joe Turner00:02:041956

-

21Lonesome TrainJohnny BurnetteGlenn Moore00:02:041956

-

22Rock Billy BoogieJohnny BurnetteDorsey Burnette00:02:351956

-

23I'm Changin' All This ChangesBuddy HollyBuddy Holly00:02:151956

-

24One Hand LooseCharlie FeathersCharlie Feathers00:02:231956

-

25Honey BopWanda JacksonMae Boren Axton00:02:141956

-

26CentipedeLew WilliamsL. Williams00:02:061956

-

27Ubangui StompWarren SmithCharles Underwood00:02:011956

-

28Latch OnRon HargraveRay Stanley00:02:011956

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Bop Bop Ba Doo BopLew WilliamsL. Williams00:02:091956

-

2Double Talkin' BabyGene VincentDanny Wolf00:02:171956

-

3I'm Coming HomeJohnny HortonJohnny Horton00:02:081956

-

4Rock ItGeorge JonesGeorge Jones00:02:151956

-

5Rock Around With Ollie VeeBuddy HollyBuddy Holly00:02:201956

-

6Rockin' DaddyEddie BondSonny Fischer00:02:021956

-

7Flying Saucer Rock And RollBilly Lee RileyR. Scott00:02:031956

-

8MatchboxCarl PerkinsCarl Perkins00:02:111957

-

9Put Your Cat Clothes OnCarl PerkinsCarl Perkins00:02:531957

-

10Pink Pedal PushersCarl PerkinsCarl Perkins00:02:291957

-

11Red HotBob LumanWilliam Robert Emerson00:02:041957

-

12It Will Be MeJerry Lee LewisJack Clement00:02:541957

-

13Teenage CutieEddie CochranEddie Cochran00:01:361957

-

14Your Baby Blue EyesJohnny BurnetteDorsey Burnette00:02:091957

-

15Rock And Roll FeverCecil CampbellCampbell00:02:291957

-

16Lewis BoogieJerry Lee LewisJerry Lee Lewis00:02:021957

-

17Worried About You BabyMaylon HumphriesArthur Crudup00:02:501957

-

18Rit It UpThe Everly BrothersRichard Penniman00:02:161957

-

19My Bucket's Got A Hole in ItRicky NelsonHank Williams00:02:031958

-

20High School ConfidentialJerry Lee LewisR. Hargrave00:02:321958

-

21Wild OneJerry Lee LewisJohn Greenham00:01:541958

-

22Lobo JonesJackie GotroeJacques Gautreaux00:01:581958

-

23Rockin' By MyselfSammy GowansSamuel Gowans00:01:541958

-

24My BabeDale HawkinsW. Dixon00:02:291958

-

25Love MeThe PhantomJerry Lott00:01:311958

-

26The Way I WalkJack ScottJack Scott00:02:401959

-

27Dancing DollArt AdamsArt Adams00:01:571960

-

28Long Black TrainConway TwittyHarold Jenkins00:02:461960

Rockabilly FA5423

THE INDISPENSABLE

ROCKABILLY

1951-1960

Bill Haley, Elvis Presley, Johnny Cash, Buddy Holly, Carl Perkins, Roy Orbison, Gene Vincent, Johnny Burnette, Jerry Lee Lewis, Wanda Jackson

ROCKABILLY 1951-1960

Par Bruno BLUM

Le rockabilly est un genre de rock déterminant. Il fut la première branche du rock véritablement et largement interprétée par des artistes blancs. Lancé par l’immense succès d’Elvis Presley qui cristallisa ce style en 1954, il représente avant tout le triomphe d’une fusion entre les musiques populaires noires et blanches aux États-Unis. La vogue du rockabilly, dont le pic se situe en 1956, favorisa une cruciale intégration raciale. Cette mixité musicale contribua beaucoup au scandale provoqué par l’irruption du rock ‘n’ roll à la télévision et sur certaines radios blanches. En effet en pleine ségrégation raciale, c’est en bonne partie grâce à la popularité de quelques titres de rockabilly que le grand public américain a adopté le rock, une musique jusque-là essentiellement confinée à une frange marginale de la communauté afro-américaine.

L’impact du rockabilly

Après l’impact majeur de Bill Haley et d’Elvis Presley en 1954-1956, le rock au sens large devint immensément populaire — ce qui a aussi favorisé le développement de la carrière de plusieurs artistes afro-américains. Au cours des décennies 1950, 1960, 1970 la musique rock est devenue un médium, un miroir sociologique et un vecteur central dans l’importante évolution des mentalités de la deuxième moitié du XXème siècle. L’intense rockabilly, forme musicale originale — où, schématiquement, des guitares country ont été greffées sur du « rock noir » chanté par des Blancs — a été extrêmement influent. Il a ouvert la porte à nombre de sous-genres et de styles qui lui ont succédé, des Shadows1 aux Beatles, des Stray Cats aux Cramps, de Crazy Cavan à Robert Gordon jusqu’au psychobilly des Meteors2. Les Beatles ont enregistré pas moins de sept titres de Carl Perkins, dont les versions originelles de Honey Don’t, Matchbox et Blue Suede Shoes sont incluses ici (la fameuse intro «one for the money, two for the show» de Perkins a été empruntée au «Rock Around the Clock» de Hal Singer paru en 1950). Les Beatles ont aussi été profondément marqués par Elvis Presley, Buddy Holly et les Everly Brothers. Après les tournées triomphales d’Eddie Cochran et Gene Vincent sur son territoire en 1960, la Grande-Bretagne a longtemps entretenu un culte du rock and roll des années 1950, incarné par les teddyboys et des groupes nos-talgiques comme Crazy Cavan and the Rhythm Rockers, Matchbox, Whirlwind et bien d’autres.

Quand les Stray Cats venus de Long Island (New York) ont mené leur fulgurant renouveau du rockabilly en 1980-1983, ils ont enregistré plusieurs titres dont les versions originales sont incluses dans cette anthologie : Ubangi Stomp de Warren Smith et Double Talkin’ Baby de Gene Vincent figurent sur leur premier album, et Your Baby Blue Eyes de Johnny Burnette sur leur deuxième. On reconnaitra aussi leur plagiat du Bop Bop Ba Doo Bop de Lew Williams, qui devint « Fishnet Stockings », sans oublier le Pink Pedal Pushers de Carl Perkins qui inspira la mélodie et les accords de leur grand succès de 1981, « Stray Cat Strut ». Les Rolling Stones les ont appréciés et invités sur leur tournée américaine de 1981, puis ont enregistré le Twenty Flight Rock d’Eddie Cochran en 1982. Soutenue par les disques Big Beat, une vague renouvelant le rockabilly a touché la France dans le sillage des Stray Cats avec des artistes comme les Alligators ou l’Anglais Vince Taylor. Quant aux Cramps, ils ont enregistré The Way I Walk de Jack Scott et ont été très marqués par le rockabilly, qui continue à influencer le rock depuis. Différentes formes de rock ‘n’ roll sont apparues dans les années 1950. Les artistes présents ici ont le plus souvent subi différentes influences et mélangé différents styles au cours de leur carrière. Mais cette anthologie s’attache à montrer le rockabilly dans sa forme la plus pure, dans son esthétique originelle.

Scandale

Dans le contexte obsolète de l’impitoyable ségrégation raciale qui asphyxiait l’Amérique des années 1950, le rockabilly n’a pas été le premier style de musique populaire à opérer un rapprochement racial majeur sur le plan culturel. La mode du swing lancée en 1935 par l’orchestre de Benny Goodman, un clarinettiste blanc, avait déjà accompli un impact d’intégration raciale perçu par le grand public. La variété « jazz » de Bing Crosby et Frank Sinatra qui en découla a suivi, puis ce fut la « dance music » instrumentale de Glenn Miller, le boogie et le calypso des Andrew Sisters. Citons aussi le western swing, le country boogie et le jazz moderne interprété par des Blancs comme Chet Baker ou Stan Getz… Ces musiques étaient significativement influencée par les fantastiques musiques afro-américaines, qui insufflaient peu à peu rythme et inspiration à toute l’Amérique.

Mais avec l’irruption du rockabilly au milieu des années 1950, l’émergence du rock ‘n’ roll auprès du grand public blanc fut un choc de générations, un clash racial, une confrontation où il fallait choisir son camp. Après un quart de siècle de récession sévère et de guerres, l’Amérique en proie à une croissance record s’était embourbée dans une mentalité réactionnaire que les progrès techniques et sociaux ne parvenaient pas à dépoussiérer. L’intensité, l’érotisme et l’arrogance de certains classiques brûlants entendus ici, comme la version de The Train Kept-a-Rollin’ par Johnny Burnette en disent plus long que tous les discours. L’hymne rockabilly Blue Suede Shoes (chaussures en daim bleu) de Carl Perkins, repris par Elvis Presley défie quiconque de lui marcher sur les pieds (la célèbre intro du morceau a été plagiée sur « Wat’cha Gonna Do » de Bill Haley and the Comets). Sur le même principe, le Duck Tail (queue de canard) de Joe Clay fait référence à sa houppe, qu’il ne faut pas abimer. Excitant, insolent, chargé de fierté masculine et de sexualité, le rockabilly surgissait de sa boîte de Pandore et bousculait l’Amérique conservatrice et pudibonde du général Eisenhower. Il dérangeait tout autant les contestataires de gauche épris de folk et les beatniks amateurs de jazz, qui le méprisaient. Les musiciens de rockabilly étaient souvent perçus comme des fauteurs de trouble venus du sud, grossiers, ruraux, vulgaires et dénués de talent. Ils furent abondamment et injustement critiqués et brocardés. L’histoire de la chasse aux sorcières qui devint la plaie d’Elvis Presley et du rock à partir de 1956 est détaillée dans le livret du volume 2 d’Elvis Presley face à l’histoire de la musique américaine 1956-1958 (FA5383) où les versions originales (souvent des compositions d’afro-américains) sont juxtaposées à ses propres enregistrements. Le rock, à commencer par sa matérialisation sous forme de rockabilly sera littéralement mis au pilori et progressivement écarté des circuits radiophoniques en 1956-57. Il ne refera surface que dans une version édulcorée avec la mode du twist en 1960-1962, qui précéda « l’invasion britannique » rock menée par les Beatles aux États-Unis en 1964.

Alors que la nouvelle génération succombait avec candeur à l’excitation propagée par Elvis Presley et ses suiveurs, d’autres considéraient cette musique comme un dévoiement qui appelait à un rejet sans équivoque. Émoustillant les femmes, et jugés suggestifs à juste titre, les mouvements d’Elvis Presley sur scène ont déclenché un anathème dès ses premières apparitions télévisées (et en particulier sa version de Hound Dog au Milton Berle Show en juin 1956). Les stéréotypes d’une musique et d’une danse trop libres associaient depuis longtemps les musiques afro-américaines à la luxure, à la vulgarité — et à une supposée infériorité sur laquelle on fermait les yeux tant qu’elle restait cantonnée aux ghettos noirs misérables. Mais que des Blancs y succombent faisait scandale. Dans un contexte aussi lourd il n’est pas étonnant que des sommets comme Race With the Devil qui évoque une course poursuite avec le diable, ou le sauvage Love Me de The Phantom exultant le désir sexuel (le disque ne sortira qu’en 1960) aient pu être appréciés comme des menaces à l’ordre paternaliste, tartuffe, dévot, consumériste et puritain d’un président Eisenhower très à droite. À cela s’ajoutait le mouvement pour les droits civiques des Afro-américains, qui sous l’impulsion de Rosa Parks puis du pasteur Martin Luther King prit beaucoup d’ampleur au fil de l’année 1956 (l’année phare du rockabilly), ce qui exacerbait les passions ségrégationnistes — et anti ségrégationnistes.

Musique du sud, le rockabilly était sulfureux à plusieurs titres. Le racisme était une cause entendue, profondément inscrite dans l’identité du sud où le dédain des personnes « de couleur » et de leur culture était extrêmement répandu. Le rock était considéré par beaucoup de Blancs comme une musique noire dégénérée et inconvenante qui dévergondait la jeunesse. En conséquence, ceux qui l’adoptaient en osant y injecter un style spécifiquement country (guitare et guitare steel notamment) commettaient un double sacrilège puisqu’ils insultaient, en plus, la tradition populaire blanche. Le rockabilly était interprété par des chanteurs de country comme Elvis Presley ou George Jones mais en raison de son pacte avec le diable afro-américain, il ne pouvait classé dans la country music.

Si certains comme Gene Vincent ou Eddie Cochran ont adopté et assumé leur étiquette «rock» sans trop de retenue, nombre de chanteurs de country avaient mauvaise conscience d’enregistrer dans le style rockabilly. En outre, ils craignaient à juste titre qu’une fois la mode passée leur réputation de rocker ne freine leur carrière. Au désespoir des amateurs de rockabilly le fantastique Johnny Burnette se métamorphosera vite en crooner à succès. George Jones a enregistré Rock It incognito sous le pseudonyme de Thumper Jones, et retournera vite à sa carrière country naissante — qui fera de lui une énorme vedette. Le géant de la country music évoquera plus tard cet écart comme un bon moment mais fera son mea culpa en le décrivant comme « l’une de ses plus mauvaises idées ». Plus tard, certains disc jockeys refuseront effectivement de diffuser les disques de country de Conway Twitty parce qu’il était connu comme chanteur de rock. Jimmie Logsdon enregistra sous le pseudonyme de Jimmy Lloyd ; et Buck Owens a sorti Hot Dog sous le nom de Corky Jones. Ce fut aussi le cas d’Hank Cochran, qui faisait ses débuts sous le nom des Cochran Brothers en duo avec son homonyme Eddie Cochran3. À l’été 1956, accompagné par son ami Eddie il a préféré sortir « Let’s Coast a While » sous le nom de Bo Davis4. En revanche d’autres, comme Johnny Horton (musicien conteur réputé pour ses sagas de l’ouest) et Johnny Cash n’ont pas été affectés par l’image rockabilly car leur musique, moins tonique, a été classée dans la country.

Hillbilly

Avant la Première Guerre Mondiale dans le sud des États-Unis, les musiques populaires appréciées par la majorité blanche étaient enracinées dans les cultures venues d’Europe : chanson irlandaise, anglaise, reel écossais, habanera hispanique, tarantelle italienne, sardane catalane, quadrille français devenu « square dance », lieders allemands, yodel tyrolien, mazurka, polka, etc. Dans le magma du chaudron culturel américain, le folklore des cultures britanniques (galloises, écossaises, irlandaises et anglaises) avec violon, instruments à vent, piano et autres se mêlaient progressivement. Ces musiques traditionnelles adoptaient différents instruments venus du continent européen, comme l’accordéon ou la guitare. Johnny Cash a par exemple été significativement marqué par la chanson irlandaise. Cette grande diversité euro-américaine était concentrée et mélangée sous diverses formes dans les musiques populaires rurales. On l’appelait souvent le hillbilly, qui fut le parent de la country music née entre les deux guerres5. Le hillbilly comprend différents styles folkloriques, notamment le bluegrass des Appalaches, où le banjo sans doute dérivé du ngoni malien est très présent — et diverses musiques folk dont la chanson contestataire, notamment représentée par Woody Guthrie6.

Au début du XXe siècle si l’on excepte la décisive région de Louisiane où les mélanges africains, caribéens, espagnols, anglais et français cajun7 ont modelé des styles à part, et sans ignorer l’influence mariachi mexicaine dans le sud-ouest, la musique populaire des États-Unis était dominée par l’influence des cultures anglo-saxonnes. Très riches, elles comprenaient les chansons populaires, les musiques militaires, la musique classique, les berceuses, le music hall et l’omniprésent « country » gospel blanc protestant8. Elvis Presley, Johnny Cash et Jack Scott enregistrèrent d’ailleurs quantité de gospel dans les années qui ont suivi leur période rockabilly initiale. De la rumba au calypso9, les musiques caribéennes10 exercèrent aussi une influence importante dans le développement des musiques du continent nord-américain. Quant à la musique hawaïenne et ses guitares slide très particulières11, elles influencèrent très significativement le hillbilly et la country music qui lui succèda12, comme on peut l’écouter ici avec les guitares pedal steel sur Drinkin’ Wine Spo-Dee-O-Dee par Malcolm Yelvington and the Star Rhythm Boys, Hound Dog par Jack Turner & his Granger County Gang, Rock the Joint de Bill Haley and the Saddlemen ou encore Rock and Roll Fever de Cecil Campbell.

Country & Western

Originaire du Mississippi, c’est dans les années 1920 que Jimmie Rogers fonda la country music proprement dite. Il incorpora notamment à son style le yodel du Tyrol allemand et fut l’un des premiers Blancs à adopter un style nettement influencé par le blues. Notre anthologie Hillbilly Blues13 met en évidence que, comme le jazz afro-américain, dès les années 1920 le blues a profondément marqué des musiciens blancs qui en avaient adopté les styles et idiomes ruraux, et les chantaient en s’accompagnant à la guitare sèche. Mais en intégrant les suites d’accords blues à trois degrés dans sa musique hillbilly, Jimmie Rodgers a fondé un nouveau genre à part : la country music. Il enregistra carrément avec des musiciens noirs — dont Louis Armstrong (« Blue Yodel #9 », 1930), un fait exceptionnel pour un chanteur blanc du sud à cette époque. Monstre sacré de la country music, Hank Williams (1923-1953) avait adopté un style de chant très marqué par le blues. Avec ses compositions et ses interprétations remarquables, Hank Williams fut l’un des pères du rockabilly. Ricky Nelson, une des grandes stars du rock de la fin des années 1950, reprend ici son My Bucket’s Got a Hole in It, dont les paroles sont dérivées d’une chanson pour enfants, « There’s a Hole in my Bucket » (la mélodie est un plagiat d’un negro spiritual, « Midnight Special »). James Burton y brille à la guitare.

Dans les années 1940, une autre branche de la musique country, le bluegrass rural des Appalaches dont le champion incontesté reste Bill Monroe était souvent plus énergique que le hillbilly et chanté sur des tempos plus rapides, avec violon et banjo. Bill Monroe et ses Bluegrass Boys ont précédé le rockabilly auquel leur style est apparenté. Mais le véritable précurseur du rockabilly fut le boogie woogie. Musique afro-américaine par excellence, le piano boogie était apprécié par le grand public dès les années 193014. Il a été incorporé à tous les styles possibles : le jazz, le blues, le swing (variété sans improvisations) jusqu’à la musique du far west : le western swing des Blancs comme Bob Wills and his Texas Playboys oscillant entre country, jazz et blues dans les bals populaires du Texas fréquentés par les ouvriers des puits de pétrole15. Le boogie a considérablement influencé la country music, inspirant d’irrésistibles morceaux sautillants à des artistes de country plus souvent enclins à la mélancolie. Les perles de country boogie qui en résultèrent sont les plus évidents précurseurs du rockabilly. Citons le « Play my Boogie » de Bill Mack (1953) et le « Guitar Boogie » d’Arthur Smith (1948)16. Ils constituent un style distinct, mais nettement apparenté au rockabilly, où les guitares jouent un rôle particulièrement délicieux17. La country & western a été très marquée par la guitare électrique, dont les géants incontestables sont Merle Travis et Chet Atkins, au style de finger picking difficile à maîtriser. Leur influence sur le rockabilly ne peut être sous-estimée. Les meilleurs guitaristes de rockabilly, comme Scotty Moore (avec Elvis Presley), Cliff Gallup (avec Gene Vincent), Carroll Dills (avec Cecil Campbell), James Burton (ici avec Bob Luman, Ricky Nelson, et plus tard Elvis Presley) ou Hal Harris (avec Joe Clay) ont tous écouté et émulé leurs styles18 de guitare au son clair. Chet Atkins en personne est d’ailleurs présent sur un titre très country des Everly Brothers et celui de Jack Turner. Et tandis que les Blancs de l’après-guerre dansaient au son du country boogie dans le sud du pays, le versant afro-américain de la musique de danse s’appelait le jump blues. Ou, selon les disc jockeys, il était nommé « rhythm and blues » et, à partir de 1950, « rock and roll ».

Rock Afro-Américain

Les rocks originels d’artistes afro-américains comme Roy Brown, Tiny Bradshaw ou Wynonie Harris étaient appréciés par une part grandissante du public blanc. À la charnière des années 1940 et1950, des titres comme leurs « Good Rockin’ Tonight », All She Wants to Do Is Rock » ou « Rockin’ at Home19 » étaient de plus en plus largement appréciés. Succédant aux musiciens de country boogie, des chanteurs blancs jusque-là confinés à la country « honky tonk »20, nettement plus détendue, ont été tentés d’enregistrer à leur tour ces morceaux énergiques en studio. Ce fut le cas du fabuleux Hound Dog de Big Mama Thornton, repris ici par Jack Turner (avec une basse électrique) dans une tentative pionnière de fusion rock et hillbilly. En 1956, la reprise d’Elvis sera un succès majeur du rock n’ roll. D’autres précurseurs ont ciselé l’esthétique rockabilly. La version originale du titre qui ouvre cet album a la réputation d’être le «premier morceau de l’histoire du rock»21. En réalité ce morceau a cette renommée car il a été enregistré par Bill Haley, un des premiers artistes blancs à enregistrer une composition de rock — un cas d’autant plus atypique qu’il vivait dans le nord du pays. Et c’est en ce sens qu’il est un précurseur du rockabilly, un genre où l’influence afro-américaine est au cœur du style. Inspiré par le Cadillac Boogie de Jimmy Liggins, le légendaire Rocket 88 est une composition du saxophoniste Jackie Brenston qui fut initialement enregistrée avec le groupe d’Ike Turner, les Kings of Rhythm ; elle est typique du rock afro-américain d’après-guerre. Ce succès célèbre les vertus de l’Oldsmobile 88, un modèle de 1949 rapide et solide mis à jour chaque année. L’arrangement du groupe de Bill Haley, les Saddlemen (avec leur contrebasse « slap » inspirée par le country boogie des Maddox Brothers and Rose) apporta un son et un swing nouveau à cette composition22. Et quand ce n’était pas des reprises de succès noirs par des Blancs, c’était le style de chant imprégné de pathos blues qui s’imposait dans le rockabilly.

En adoptant des compositions et une forte influence afro-américaine, traduite dans un langage et un format accessibles au grand public blanc, ces artistes de country reconnaissaient implicitement leur respect pour ces musiciens d’origine africaine. Une avancée spectaculaire — et souvent très mal appréciée dans le sud du pays où le scandale brisa nombre de carrières en 1956-60. Les États-Unis et le monde attendaient pourtant cette cruciale intégration depuis un siècle, depuis la victoire des Nordistes sur les Sudistes, qui en 1865 avait arraché l’abolition de l’esclavage promulguée quelques jours avant l’assassinat du président abolitionniste Abraham Lincoln. Le succès de Bill Haley et le phénomène Elvis Presley ont été les premiers catalyseurs de ce rockabilly charnière sociologique. Avide de liberté, la jeunesse a basculé au son d’Elvis et de son scandale. Les interactions entre musiques afro-américaines et euro-américaines ont toujours été très présentes aux Amériques et sont à l’origine de la richesse du rock ‘n’ roll23. Mais la sulfureuse synthèse rockabilly a véritablement ouvert une brèche dans laquelle s’engouffrèrent dès les années 1950 nombre de musiciens afro-américains essentiels comme Ray Charles24, Bo Diddley25, Little Richard26, Chuck Berry27 ou James Brown28. Il a participé à tourner peu à peu la page d’une effroyable ségrégation — et insufflé à la nouvelle génération un vent d’anticonformisme, de liberté inédit.

Le Rockabilly

Le rockabilly a connu quelques titres annonciateurs de Bill Haley et d’autres, mais il est véritablement né sous l’impulsion créative de Sam Phillips, producteur visionnaire s’il en fut (et qui appelait ce style « rock ‘n’ roll » et trouvait péjoratif le terme « rockabilly » imposé en 1956 par le magazine du nord, le Billboard). Phillips découvrit et lança Malcolm Yelvington, Roy Orbison, Sonny Fisher, Jerry Lee Lewis, Carl Perkins, Johnny Cash et Elvis Presley — entre autres. Après une série rockabilly enregistrée au studio Sun, et quelques précurseurs dont Carl Perkins, le succès démentiel d’Elvis en 1956 a instantanément créé une demande en jeunes rockers blancs. Cette année-là, des centaines de jeunes artistes impressionnés par le phénomène Elvis et ses innovations stylistiques ont répondu à la demande du marché, parmi lesquels Gene Vincent, Eddie Cochran, Buddy Holly, Marvin Rainwater ou Jess Hooper. Nourris de musique country conventionnelle qui leur semblait maintenant quelque peu appartenir à une autre génération, ils se tournaient peu à peu vers le rock noir si excitant et si extraordinairement riche, qu’ils assimilèrent. Une foison de disques est parue, souvent sur de petites marques locales. Certains artistes comme Ron Hargrave, auteur de Latch On et High School Confidential, composèrent quelques hymnes pour cet âge nouveau qui commençait. Notre anthologie réunit d’incontournables classiques du rockabilly comme Mystery Train, Blue Suede Shoes, Be-Bop-a-Lula, Rock Billy Boogie ou Folsom Prison Blues. Mais cette indispensable sélection est largement complétée par des 45 tours aussi lumineux qu’obscurs, enregistrés spontanément avec des musiciens aussi talentueux qu’oubliés, comme les guitaristes Grady Martin, Paul Burlison, Terry Thompson ou Roy Buchanan. Espérons que cet album contribuera à ce que les perles de Joe Clay, Lew Williams, Andy Starr, Sonny Fisher, Charlie Feathers, Buck Griffin, Junior Thompson ou l’hystérique Sonny Burgess et leurs accompagnateurs ne soient pas totalement effacées de l’histoire. La version originale de Whole Lotta Shakin’ Goin’ On, qui rendra plus tard Jerry Lee Lewis célèbre, a été composée et enregistrée le 21 mars 1955 par Big Maybelle (Mabel Smith). Elle est ici plagiée par Roy Hall, qui s’en est attribué la paternité alors qu’il ne l’a enregistrée que six mois plus tard, créant ainsi un titre de rockabilly. En découvrant les titres méconnus de Johnny Horton, Buck Owens, Eddie Bond ou Merle Kilgore on comprend que le réservoir du rockabilly originel est très vaste. Sélectionné rigoureusement autour de critères de qualité, cet album est également référencé avec soin. Il fournit ainsi un faisceau de pistes à suivre, qui vise à diffuser les clés pour découvrir et mieux apprécier ce son particulier, authentique et excitant, fruit d’une fusion musicale unique en son genre, témoignage d’une époque.

Fusion du « rock » noir et du « billy » blanc chanté dans Rock Billy Boogie, l’esthétique rockabilly peut être définie par quelques critères simples : rythmique swing entre country et boogie woogie, une tendance déjà annoncée par des artistes de country d’après-guerre comme Tennessee Ernie Ford, Moon Mullican ou les Delmore Brothers, plus une guitare au son clair caractéristique de la country music, dérivé des maîtres blancs Chet Atkins, Joe Maphis, Grady Martin ou Merle Travis. Le style de guitare y est essentiel. Car s’il en a subi l’influence, le rockabilly est bien distinct du rock afro-américain de Big Joe Turner, Jimmy McCracklin, Lloyd Price, Johnny Otis, Little Richard ou Jackie Brenston qui employaient beaucoup d’instruments à vent. Il est également distinct de guitaristes rockers noirs comme Junior Parker avec Pat Hare (dont le « Love Me Baby » de 1953 a néanmoins marqué le rockabilly), Johnny « Guitar » Watson ou Chuck Berry, dont le style de guitare était essentiellement hérité du blues29. Mais c’est avant tout la façon de chanter très sentie, souvent éraillée et expulsée avec force et le répertoire du rockabilly qui ont été empruntés au rock noir. Beaucoup de compositions incluses ici étaient déjà des classiques avant d’être réarrangées en rockabilly : on retrouve sur ce florilège les compositeurs afro-américains Jackie Brenston, Arthur Crudup, Roy Brown, Arthur Gunter, Junior Parker, Ivory Joe Hunter, Tiny Bradshaw, Fats Domino, Little Richard et Willie Dixon — sans oublier Jerry Leiber et Mike Stoller, deux Blancs qui écrivaient dans le style et pour des artistes afro-américains (et compteront en 1956 parmi les compositeurs attitrés d’Elvis Presley). On trouve en revanche une forte influence country dans l’image et les costumes des chanteurs (Elvis, lui, n’hésitait pas à s’habiller chez Lansky’s, une boutique de Memphis fréquentée par les Noirs). Ce rock noir chanté par des Blancs véhiculait une aura, une arrogance et un son bien particulier qui faisait vibrer les adolescent(e)s. Cette influence country dans le rock marquera à son tour plusieurs artistes noirs dans les années 1950. Mickey Baker, géant des séances Atlantic de la décennie, joue d’ailleurs ici sur un titre de Joe Clay. Ce sera aussi une grande force de Chuck Berry que d’avoir intégré cette influence dans son œuvre dès 1955. Il sera suivi en ce sens par Roy Brown chez Imperial en 1956, Bo Diddley dans sa période Gunslinger (1960), Ray Sharpe et d’autres.

La contrebasse parfois « slap » (aux cordes claquées) caractéristique du rockabilly (où Bill Haley l’a introduite) est sans doute héritée du country boogie des Maddox Brothers, mais c’est le contrebassiste de Louisiane Wellman Braud, père de la très influente « walking bass », qui avait lancé ce style des années plus tôt dans l’orchestre jazz de Duke Ellington. La fameuse banane (duck tail, ou « queue de canard ») lancée par Elvis tranchait avec la coupe propre et très courte des artistes de country qui n’hésitaient pas à s’affubler de chapeaux de cow-boys. Les meilleurs représentants du rockabilly étaient souvent d’origine humble et rurale comme Charlie Feathers, Warren Smith (Mississippi), Carl Perkins (Tennessee), Billy Lee Riley (Arkansas), Jerry Lee Lewis ou le méconnu Joe Clay (Louisiane). Ils étaient capables d’interprétations plus brutes, rudes et senties qui correspond à l’esprit du rock originel nourri de gospel noir de Tiny Bradshaw, Roy Brown ou Little Richard. Les cris d’excitation des musiciens (entendus ici chez Billy Lee Riley, Gene Vincent, Johnny Burnette, etc.) ajoutaient un cachet vraiment particulier. Issus d’un milieu urbain, Elvis Presley, ses voisins Johnny Burnette et son frère Dorsey n’en étaient pas moins des prolétaires à Memphis ; spontanés et peu instruits, il appartiennent eux aussi à cette catégorie capable d’interpré-tations « brutes » très senties. Inversement, les Everly Brothers, Buddy Holly ou Lew Williams (ici avec le géant de la guitare jazz Barney Kessel parachuté dans cette séance rock) issus d’un milieu urbain chantaient avec plus de sophistication et de douceur. Quant à Eddie Cochran, il vivait à Los Angeles et a vite révélé une forte personnalité de chanteur. Il n’avait que dix-sept ans quand il a gravé Pink Pegged Slacks30.

La pureté esthétique du rockabilly n’a duré que trois ans environ, de 1954 à 1957. Comme le fit Elvis Presley, Eddie Cochran, Buddy Holly ou Ricky Nelson évoluèrent vite vers de nouvelles influences dès 1956, ouvrant de nouveaux horizons pour le rock ‘n’ roll. Comme Roy Orbison qui enregistrera par la suite de véritables prouesses vocales, Johnny Cash et le pianiste Jerry Lee Lewis sont à l’origine de leur propres styles, de véritables écoles. Mais à l’exception de Jerry Lee « The Killer », aucun d’entre eux ne persévèrera dans la voie du rockabilly originel, comme le confirment les volumes 2 des coffrets consacrés à Elvis Presley, Eddie Cochran et Gene Vincent dans cette collection. Leurs styles évolueront, le plus souvent dans une direction plus présentable. Face à l’opprobre et au scandale, beaucoup d’artistes, parmi lesquels Wanda Jackson, Ricky Nelson, Johnny Burnette, Elvis Presley, Gene Vincent ou Conway Twitty, n’auront d’autre choix que de s’éloigner du précieux son sauvage que l’on entend ici avec Maylon Humphries ou Sammy Gowans.

Bruno Blum, 2013

Merci à Muriel Blum, Yannick Blum, Yves Calvez, Jacky Chalard, Gilles Conte, Guillaume Gilles, Christophe Hénault, Youri Lenquette, Slim Jim Phantom, Patrick Renassia (Rock Paradise), Lee Rocker, Brian Setzer et Marc Zermati.

© FRÉMEAUX & ASSOCIÉS 2014

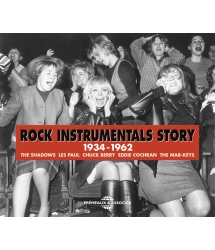

1. Retrouvez les Shadows sur Rock Instrumentals Story 1934-1962 (FA5426) dans cette collection.

2. Lire le livret et écouter Roots of Punk Rock 1926-1962 (FA5415) dans cette collection.

3. Écouter The Indispensable Eddie Cochran 1955-1960 (FA5425) dans cette collection.

4. Écouter «Let’s Coast a While» d’Hank Cochran alias Bo Davis avec Eddie Cochran à la guitare sur notre anthologie Road Songs - Car Tune Classics 1942-1962 (FA5401).

5. Lire le livret et écouter Country - Nashville-Dallas-Hollywood 1927-1942 (FA015) dans cette collection.

6. Lire le livret et écouter Protest Songs (à paraître) dans cette collection.

7. Lire le livret et écouter Cajun - Louisiane 1928-1939 (FA019) dans cette collection.

8. Lire le livret et écouter Country Gospel 1926-1946 (FA055) dans cette collection.

9. Écouter l’influence internationale du calypso dans Calypso 1944-1958 (coffret Anthologie des Musiques de Danse du Monde FA5342) dans cette collection.

10. Lire le livret et écouter Trinidad - Calypso 1939-1959 (FA5348), Bahamas Gombey & Calypso 1935-1960 (FA5374), Bahamas Goombay 1951-1959 (FA5302), Jamaica - Mento 1956-1961 (FA5358) et Virgin Islands 1956-1960 (FA5403).

11. Lire le livret et écouter Electric Guitar Story - Country, Jazz, Blues, R&B, Rock 1935-1962 (FA5421) dans cette collection.

12. Lire le livret et écouter Hawaiian Music 1927-1944 (FA035) et Hawaiians in Paris 1916-1926 (FA066) dans cette collection.

13. Lire le livret et écouter Hillbilly Blues 1928-1946 (FA065) dans cette collection.

14. Lire les livrets et écouter notre série de trois albums Boogie Woogie Piano (FA036, FA5164, FA5226) dans cette collection.

15. Lire le livret et écouter Western Swing - Texas 1928-1944 (FA032) et Bob Wills & his Texas Playboys 1932-1947 (FA164) dans cette collection.

16. Retrouvez Arthur Smith sur Rock Instrumentals 1934-1962 (FA5426, qui inclut « Guitar Boogie ») dans cette collection et sur Guitare Country - From Old Time to Jazz Times 1926-1950 (FA5007).

17. Lire le livret et écouter Country Boogie 1939-1947 (FA160) dans cette collection.

18. Lire le livret et écouter Electric Guitar Story 1935-1962 (FA5421) et Guitare Country - From Old Time to Jazz Times 1926-1950 (FA5007) dans cette collection.

19. Écouter « Rockin’ at Home » par Floyd Dixon sur Roots of Ska - USA-Jamaica rhythm and blues shuffle 1942-1962 (FA5396) dans cette collection.

20. Lire le livret et écouter Honky Tonk Country Music 1945-1953 (FA 5087) dans cette collection.

21. La version originale de Rocket 88 par Jackie Brenston est incluse sur Road Songs - Classic Car Tunes 1942-1962 (FA5401). Les deux versions sont disponibles dans le volume Rock n’ Roll 1951 dans cette collection (FA357).

22. Lire le livret et écouter The Indispensable Bill Haley 1948-1961 (FA5465) dans cette collection.

23. Lire les livrets et écouter notre série d’anthologies Rock n’ Roll : Volume 1 1927-1938 (FA 351), Volume 2 1938-1946 (FA352), Volume 3 1947 (FA353), Volume 4 1948 (FA354), Volume 5 1949 (FA355), Volume 6 1950 (FA356), Volume 7 1951 (FA357) et Volume 8 1952 (FA359)

24. Lire le livret et écouter Ray Charles - Brother Ray: The Genius 1949-1960 (FA5350) dans cette collection.

25. Lire le livret et écouter The Indispensable Bo Diddley 1955-1960 (FA5376) et 1959-1962 (FA5406).

26. Lire le livret et écouter The Indispensable Little Richard 1955-1958 à paraître dans cette collection.

27. Lire le livret et écouter The Indispensable Chuck Berry 1954-1961 (FA5409) dans cette collection.

28. Lire le livret et écouter The Indispensable James Brown 1956-1961 (FA5378) dans cette collection.

29. Retrouvez Johnny « Guitar » Watson, Chuck Berry et Junior Parker avec Pat Hare sur Electric Guitar Story - Country, Jazz, Blues, R&B, Rock 1935-1962 (FA5421) dans cette collection.

30. Lire le livret et écouter The Indispensable Eddie Cochran 1955-1960 (FA5425) dans cette collection.

ROCKABILLY 1951-1960

By Bruno Blum

Rockabilly is a defining genre. In being the first of rock ’n’ roll branches to be played by white artists en masse, it critically inflected rock’s course. Launched by the immense success of Elvis Presley, who crystallized the style in 1954, rockabilly was above all the triumph of the black- and white-style fusion in American popular music. It reached the peak of its popularity in 1956 and helped shaping crucial racial integration. Its musical mix contributed to the scandal caused when TV screens — and some white radio stations — where invaded by rock ‘n’ roll: coming in the midst of segregation, a few rockabilly titles were largely successful enough for American mass audiences to adopt rock music, previously confined essentially to a fringe-audience in the Afro-American community.

The impact of rockabilly

After Presley’s major impact in 1954-1956, rock in the larger sense became immensely popular, furthering the careers of several Afro-American artists along the way. In the Fifties to the Seventies, rock music became a medium: it was a sociological mirror and a central vector of the major evolution in mentality which took place in the second half of the 20th century. Rockabilly was an intense, original music-form — broadly speaking, “country” guitars were grafted onto “black rock’” sung by white artists — and it opened doors to a number of sub-genres and subsequent styles played by groups from The Shadows1 to The Beatles, and from The Stray Cats, Cramps, Crazy Cavan and Robert Gordon to the “psychobilly” of The Meteors2. The Beatles recorded no fewer than seven Carl Perkins titles, and here you can find the original versions of his Honey Don’t, Matchbox and Blue Suede Shoes (the famous “one for the money, two for the show” intro of the latter was borrowed from Hal Singer’s 1950 “Rock Around the Clock”). The Beatles were also deeply marked by Presley, Buddy Holly and the Everly Brothers. After triumphant British tours by Eddie Cochran and Gene Vincent in 1960, the U.K. saw the birth of a 1950s rock ‘n’ roll cult, as exemplified by teddy-boys and nostalgia-bands like Crazy Cavan and the Rhythm Rockers, Matchbox, Whirlwind and many others.

When The Stray Cats (from Long Island, New York) led their lightning rockabilly revival in 1980-1983, they recorded several titles whose original versions appear in this set: Ubangi Stomp by Warren Smith and Double Talkin’ Baby by Gene Vincent appeared on their first album and Your Baby Blue Eyes by Johnny Burnette on their second. You’ll also recognize Bop Bop Ba Doo Bop by Lew Williams, which they plagiarized as “Fishnet Stockings”, and the Carl Perkins song Pink Pedal Pushers which inspired the melody and chords of their great 1981 hit “Stray Cat Strut”. The Rolling Stones were fans and invited them on their 1981 American tour, and then they recorded Twenty Flight Rock by Eddie Cochran in 1982. Backed by Big Beat Records, a new rockabilly wave swept France in the wake of The Stray Cats with artists like The Alligators or the English singer Vince Taylor. As for The Cramps, they recorded The Way I Walk by Jack Scott and were strongly influenced by rockabilly (which has continued to mark rock ever since).

Different forms of rock ‘n’ roll appeared in the Fifties, and the artists featured here were most often subjected to various influences, mixing different styles in the course of their careers. The aim of this anthology, however, is to present rockabilly in its purest form and in its original aesthetic.

Scandal

In the obsolete context of the merciless racial segregation which asphyxiated America in the Fifties, rockabilly wasn’t the first popular music style to operate a major racial reconciliation on a cultural level. The swing craze laun-ched in 1935 by White clarinetist Benny Goodman’s orchestra had already made a visible impact on racial integration perceived by the mass audience. Bing Crosby and Frank Sinatra’s “jazz” pop followed, and there was also Glenn Miller’s instrumental “dance music” as well as The Andrews Sister’s boogie and calypso. Western swing can also be mentioned, and the country boogie and modern jazz played by white artists like Chet Baker or Stan Getz… These genres were significantly influenced by fantastic Afro-American music styles which gradually breathed rhythm and inspiration into music across the whole of America.

When rockabilly broke through in the mid-Fifties, however, rock ‘n’ roll awareness among the mass white audience coincided with the clash between generations — the shock was also racial — and people had to choose sides in this confrontation. After a quarter-century of war and severe recession, America, now prey to a record growth in population, was bogged down in a reactionary mentality which tried to resist all kinds of social and technical progress. The intensity, eroticism and arrogance in some red-hot classics contained in this set, like the version of The Train Kept-a-Rollin’ by Johnny Burnette, speak louder than any political discourse. The rockabilly anthem Blue Suede Shoes from Carl Perkins, covered by Elvis Presley, is a challenge to anyone who might step on his toes. The same applies to Duck Tail by Joe Clay, which refers to his haircut: his hair wasn’t to be messed with. Exciting, insolent, and loaded with male pride and sexuality, rockabilly sprang out of its Pandora’s Box and bowled over General Eisenhower’s conservative, prudish America. It was just as upsetting for left-wing agitators who liked folk and beatnik jazz-fans who scorned it. Rockabilly musicians were often seen as Southern trouble-makers: crude and vulgar hicks who lacked talent. They were abundantly — and unfairly — criticized, and taunted constantly. The story of the witch-hunt which plagued Presley (and indeed rock) from 1956 onwards is explained in detail in the booklet enclosed with Vol. 2 of Elvis Presley & the American Music Heritage 1956-1958 (FA5383), a set where original versions of songs (often composed by Afro-Americans) appear alongside Elvis’ own recordings of them. Rock, in its rockabilly incarnation, was sent to the pillory: slowly, between 1956 and ‘57, radio networks began keeping it at a distance, and it only resurfaced, watered down, in 1960-62 with the twist craze preceding the Brit-rock “invasion” of the USA led by The Beatles in 1964.

While the new generation succumbed with candour to the excitement propagated by Presley and those who followed later, others perceived the music as corrupt, and unequivocally called for its rejection. Presley’s stage behaviour titillated girls and was correctly deemed suggestive; his first television appearances were anathema to most, particularly his Hound Dog performance on the Milton Berle Show in June 1960. Music and dance stereotypes that were too “free” had associated Afro-American music with lewdness and vulgarity for a long time — not to mention a supposed inferio-rity to which people closed their eyes (as long as it remained contained inside the wretched ghettoes where black folk lived…). But the fact that Whites were succumbing to it was seen as scandalous. In such an oppressive context, it’s not surprising that such fantastic titles as Race with the Devil or the wild Love Me by The Phantom — exulting sexual desire, the record didn’t come out until 1960 — were perceived as threats to the paternalist, hypocritical, devoutly Puritan and consumerist order of society extolled by a right-wing President such as Eisenhower. To that could be added the Civil Rights movement which, spurred on by Rosa Parks and then the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr., took on major importance in the course of 1956 — a glorious year for rockabilly — and exacerbated passions in both camps: those for segregation and those against it.

Rockabilly was music from the South, and it reeked of sulphur for several reasons. Racism was an accepted cause, deeply written into a southern identity marked by widespread disdain for “coloureds” and their culture. Many Whites considered rock as unsuitable: it was “degenerate” Black music which led young people to debauchery. And consequently those who adopted it and dared to inject it with a specifically country style (notably with guitars and steel guitars) were committing a double sacrilege because they were also insulting a White popular tradition: it’s true that rockabilly was performed by country singers like Elvis or George Jones, but they had supposedly sealed a pact with the Afro-American devil, and so it didn’t qualify as country music.

If some singers like Gene Vincent or Eddie Cochran were quite easy with their “rock” label and adopted it without too much restraint, many country singers were very uncomfortable about recording in the rockabilly style. In addition, they (rightly) feared that, once the fad disappeared, their reputation as rockers would put their careers on hold. To the great despair of rockabilly fans, the fantastic Johnny Burnette quickly metamorphosed into a successful crooner. George Jones recorded Rock It incognito under the pseudonym Thumper Jones, and quickly returned to his nascent country career to become a huge star. This giant of country music would later refer to his “sidestep” as a good period… while making his confession at the same time: he said it was one of his “worst ideas”. Later, some disc-jockeys actually refused to play country records by Conway Twitty because he was known as a rock singer. Jimmie Logsdon would record as Jimmy Lloyd, and Buck Owens released Hot Dog under the pseudonym Corky Jones. Another was Hank Cochran: he started out as The Cochran Brothers, singing duets with his namesake Eddie Cochran3, but in the summer of 1956, accompanied by his friend Eddie, he preferred to release “Let’s Coast a While” under the name Bo Davis.4 Others, however, like Johnny Horton (a musician known for his tales of western sagas), or Johnny Cash, weren’t affected by the rockabilly image because their music, less invigorating, was classified as “Country”.

Hillbilly

In southern U.S. states before World War II, the music appreciated by the white majority had roots in European culture: Irish and English songs, Scottish reels, habaneras from Spain, Italian tarantellas, Catalan sardanas, the French quadrille which became the square dance, Germany’s “Lieder”, yodelling from the Tyrol, mazurkas, polkas, etc. In the melting-pot of American culture, folk music originating in the British Isles (from Wales & Ireland to England via Scotland) found its violins slowly mixing with pianos, wind instruments and others from the European mainland, like the accordion and the guitar. Irish songs made a deep impression on Johnny Cash, for example. This Euro-American diversity was mixed and concentrated under various forms in rural popular music, and it was often called hillbilly, the parent of the country music born between the wars. 5 Hillbilly contains different folk styles, notably Appalachian bluegrass music where the banjo, perhaps derived from the ngoni of Mali, is a mainstay, and other folk music including the protest songs represented by the like of Woody Guthrie.6

Early in the 20th century, apart from the importance of the Louisiana area where a mixture of African, Caribbean, Spanish, English and French Cajun7 influences modelled separate styles (not forgetting the Mexican mariachi influence in the northwest), popular music in The United States was dominated by rich Anglo-Saxon cultures: these included popular songs, military and classical music, lullabies, music-hall and the omnipresent “country” gospel of white Protestants.8 Elvis Presley, Johnny Cash and Jack Scott incidentally recorded many gospels in the years following their initial rockabilly period. From rumba to calypso,9 Caribbean music also wielded major influence over the development of music across the North American continent. As for the music of Hawaii and its very special slide guitars,10 it had a significant impact on hillbilly and the country music which succeeded it,11 as you can see here from the pedal steel guitars on Drinkin’ Wine Spo-Dee-O-Dee by Malcolm Yelvington and the Star Rhythm Boys, Hound Dog by Jack Turner & his Granger County Gang, Rock the Joint by Bill Haley and the Saddlemen or again Rock and Roll Fever by Cecil Campbell.

Country & Western

Country music proper was founded in the 1920s by Jimmie Rodgers, who was originally from Mississippi. He incorporated the yodelling of the German Tyrol into his style, and was one of the first Whites to adopt a style with a clear blues influence. Our anthology Hillbilly Blues12 shows how the blues, like Afro-American jazz, deeply marked white musicians in that period; they adopted the styles and rural idioms of blues and jazz in their own songs, accompanying themselves on acoustic guitars. But when Jimmie Rodgers integrated three degrees blues chord progressions in his hillbilly music, he founded a new, distinct style: country music. Rodgers even recorded with black musicians — among them Louis Armstrong (“Blue Yodel #9”, 1930) — which was an exceptional feat for a White southern singer in that period. Another country-music great, Hank Williams (1923-1953), had adopted a song-style that carried a deep blues imprint; his remarkable compositions and performances made Hank one of the fathers of rockabilly. Ricky Nelson, one of rock’s great stars at the end of the Fifties, here picks up his song My Bucket’s Got a Hole in It, with lyrics derived from the children’s song “There’s a Hole in my Bucket” (its melody plagiarizes the Negro spiritual “Midnight Special”.) James Burton is the brilliant guitarist on this one.

In the 1940s, the rural bluegrass style of the Appalachians was another branch of country music with Bill Monroe as its uncontested champion. It often had a more energetic sound than hillbilly music and was sung over quick tempos with violins and banjos. Bill Monroe and his Bluegrass Boys came before rockabilly and their styles were related; but rockabilly’s real precursor was boogie woogie. As Afro-American music par excellence, piano boogie was appreciated by audiences as early as the Thirties13 and has been incorporated into any number of styles: jazz, blues, swing (popular music without improvisations) and even the music of the far west; the western swing of White bands like Bob Wills and his Texas Playboys oscillated between country, jazz and blues in the Texas dance-halls where oil-workers used to let off steam.14 Boogie had a major influ-ence on country music, and inspired some compelling danceable numbers to country artists more often given to melancholy… The country boogie gems which resulted are rockabilly’s most obvious precursors: there was “Play my Boogie” by Bill Mack (1953) for example, and Arthur Smith’s “Guitar Boogie” in 1948.15 These formed a distinct style even though it bore an obvious relation to rockabilly with the guitars playing a particularly delicious role.16

Country & Western was marked by the electric guitar, whose undisputed aces were Merle Travis and Chet Atkins. They played a finger-picking style that was extremely difficult to master. Their influence on rockabilly is not to be underestimated. The best rockabilly guitarists like Scotty Moore (with Elvis Presley), Cliff Gallup (with Gene Vincent), Carroll Dills (with Cecil Campbell), James Burton (here with Bob Luman, Ricky Nelson, and later Elvis Presley) or Hal Harris (with Joe Clay) all listened closely and emulated their clean-sound guitar styles.17 Incidentally, Chet Atkins in person plays here on one very “country” title by the Everly Brothers and on the Jack Turner title. Finally, while Whites of the post-war years were dancing in the South to the sounds of country boogie, the Afro-American dance-equivalent was known as jump blues or, depen-ding on which disc jockey you were listening to, “rhythm and blues” (and from 1950 onwards, “rock and roll”).

Afro-American Rock

The seminal rock songs of African-American artists like Roy Brown, Tiny Bradshaw or Wynonie Harris were liked by an increasingly large white audience, and when the 1940s moved into the 1950s, tunes such as “Good Rockin’ Tonight”, “All She Wants to Do Is Rock” or “Rockin’ at Home”18 found many new fans. Coming after country boogie musicians, white singers who had until then confined themselves to “honky tonk”19 country music, which was much more relaxed, were tempted in turn to record these energetic pieces in the studios. This was the case with the fabulous Hound Dog title by Big Mama Thornton, here picked up by Jack Turner (with an electric bass) in a pioneering attempt at a fusion of rock and hillbilly. Presley’s 1956 version would be a major rock n’ roll hit. Other precursors put finishing touches to the rockabilly style: the original version of the track opening this set has the reputation of being “the first piece of rock history”,20 but in reality it owes its fame to the fact that it was recorded by Bill Haley — one of the first white artists to record a rock composition — whose situation was all the more atypical because Haley lived in the north of the country. And it’s in this sense that he was a precursor of rockabilly: the genre had Afro-American influences at its heart. Inspired by Jimmy Liggins’ Cadillac Boogie, the legendary Rocket 88 was written by saxophonist Jackie Brenston, who recorded it with Ike Turner’s band The Kings of Rhythm. “Rocket 88” is typical of the African-American rock of the post-war era, and became a hit as a celebration of the virtues of the Oldsmobile 88, a 1949-model automobile which was fast and reliable, with new versions leaving the factory every year. The arrangement played by Haley’s band The Saddlemen (with their “slap” bass inspired by the country boogie of The Maddox Brothers and Rose) brought an inspired sound with a new swing to the song21. And when Whites weren’t covering Black hits, it was the song-style, impregnated with the pathos of the blues, which imposed itself in rockabilly.

In adopting compositions and a strong Afro-American influence, and in translating them into a language and format which could reach a mass white audience, these country artists were implicitly recognizing their respect for musicians of African descent. It was spectacular progress… and often very badly received in the South, where scandal destroyed many careers between 1956 and 1960. Even so, the USA (and the rest of the world) had been waiting over a century for this crucial integration to become reality, in fact ever since the Confederate defeat in 1865 which preserved the abolition of slavery promulgated a few days before the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln. Bill Haley and the Elvis Presley phenomenon were the first catalysts in this rockabilly which represented the change in society. Eager for freedom, young people fell under its sway to the sound of Elvis and the scandal surrounding him. Interaction between Afro-American and Euro-American music styles has always been present in the Americas, and lies at the origin of the richness of rock ‘n’ roll.22 But this quasi-heretical rockabilly synthesis genuinely opened a breach, and into it jumped a number of essential African-American musicians of the 1950s: Ray Charles23, Bo Diddley24, Little Richard25, Chuck Berry26 and James Brown.27 Little by little, it contributed to put an end to appalling segregation — and caused a brand-new wind of nonconformist liberty to blow over the new generation.

Rockabilly

If rockabilly was announced by a few titles from Bill Haley and others, its genuine birth came under the creative impetus of Sam Phillips, a visionary producer if ever there was : Phillips discovered and launched Malcolm Yelvington, Roy Orbison, Sonny Fisher, Jerry Lee Lewis, Carl Perkins, Johnny Cash and, of course, Elvis Presley — and there were others. After a series of rockabilly titles recorded at Phillips’ Sun Studio, and a few precursors like Carl Perkins, the wild success of Elvis in 1956 created instant demand for more young white rockers. That year, literally hundreds of young artists impressed by the Elvis phenomenon (and his innovations in style), sprang up in answer to the demand, and among them were Gene Vincent, Eddie Cochran, Buddy Holly, Marvin Rainwater and Jess Hooper. Raised on the conventional forms of country music which now seemed to belong to another generation altogether, these artists gradually turned to the black rock music which was so exciting and rich; they all assimilated it. A flood of records came out, often released by little local labels; and from artists like Ron Hargrave, the author of Latch On and High School Confidential, came hymns for the dawning of this new age.

This anthology contains many indispensable rockabilly classics, like Mystery Train, Blue Suede Shoes, Be-Bop-a-Lula, Rock Billy Boogie or Folsom Prison Blues; but it is handsomely complemented by many 45rpm singles which are as illuminating as they are obscure, spontaneously recorded with musicians whose talents make their own relative obscurity all the more regrettable, like Grady Martin, Paul Burlison, Terry Thompson or Roy Buchanan, to name only the guitarists. So we hope this set will be useful in ensuring that these pearls by Joe Clay, Lew Williams, Andy Starr, Sonny Fisher, Charlie Feathers, Buck Griffin, Junior Thompson and the hysterical Sonny Burgess — and their companions — are not totally erased from the history books. The original version of Whole Lotta Shakin’ Goin’ On - the title which later made Jerry Lee Lewis a celebrity - was written and first recorded on March 21, 1955 by Big Maybelle aka Mabel Smith then plagiarized by Roy Hall, whose rendition is heard here. When you discover the little-known efforts of Johnny Horton, Buck Owens, Eddie Bond or Merle Kilgore, you realize that original rockabilly had an immense reservoir on which to draw. The recording quality of these pieces was just one criterion in their selection, and great care was taken in referencing them for this set; the result is a myriad of trails to follow, and each trail provides a key to the discovery of that special sound, authentic and exciting, which came from a musical fusion that was unique in its genre: it witnessed a whole era.

The rockabilly aesthetic — the fusion of black “rock” and white “billy” sung in Rock Billy Boogie — can be defined according to a few simple criteria: swing rhythms coming from country and boogie woogie (a trend already heralded by post-war country artists like Tennessee Ernie Ford, Moon Mullican or The Delmore Brothers), plus a guitar with the clear sound that characterizes country music and is derived from some white Masters: Chet Atkins, Joe Maphis, Grady Martin and Merle Travis. The guitar style is essential, because even though rockabilly was subjected to its influence, it still remains distinct from the Afro-American rock of Big Joe Turner, Jimmy McCra-cklin, Lloyd Price, Johnny Otis, Little Richard or Jackie Brenston, who used many wind instruments. The sound is also distinct from that of guitarists who were black rockers, like Junior Parker with Pat Hare (even if his 1953 title “Love Me Baby” had a definite influence on rockabilly), or Johnny “Guitar” Watson and Chuck Berry, whose guitar style was essentially inherited from the blues.28

But the main borrowings from black rock were the vocal styles, full of feeling, often rasping and forcefully expressed, and the repertoire. Many compositions included here were already classics before they were rearranged as rockabilly titles: the works of Afro-American composers like Jackie Brenston, for example, along with Arthur Crudup, Roy Brown, Arthur Gunter, Junior Parker, Ivory Joe Hunter, Tiny Bradshaw, Fats Domino, Little Richard or Willie Dixon; and let’s not forget Jerry Leiber & Mike Stoller — two Whites who wrote in Black styles (mainly for African-American artists) — and turned out to compose hits for Elvis in 1956. On the other hand, you can find a strong country influence in the singers’ image and dress (whereas Elvis used to wear clothes from Lansky’s, a Memphis boutique where Blacks were regular customers). This “Black rock sung by Whites” conveyed a special aura, a particular “attitude” and sound which had vibrating affinities with teens of both sexes. Several black artists were also marked by this country influence on Fifties rock: Mickey Baker, for example, a giant on Atlantic sessions in that decade, plays here on a title by Joe Clay. And one of Chuck Berry’s great strengths was to have integrated this influence in his work as early as 1955. He was followed in this direction by Roy Brown at Imperial in 1956, Bo Diddley in his Gunslinger period (1960), Ray Sharpe et al.

The double bass (sometimes played “slap bass”, i.e. by smacking the strings) was a characteristic of rockabilly perhaps inherited from the country boogie of The Maddox Brothers (and introduced in Rockabilly by Bill Haley), but it was a Lousiana bassist named Wellman Braud — the father of the highly influential “walking bass” — who had launched this style years earlier in the jazz orchestra led by Duke Ellington. The famous duck tail worn by Elvis was very much at odds with the short, clean haircut of country artists, who didn’t give a second thought to wearing a Stetson. The best rockabilly artists often came from humble, rural backgrounds, like Charlie Feathers, Warren Smith (Mississippi), Carl Perkins (Tennessee), Billy Lee Riley (Arkansas), Jerry Lee Lewis or the lesser--known Joe Clay (Louisiana). They were capable of performances that were much rougher, raw and emotional deliveries in tune with the seminal black gospel-nourished rock spirit of Tiny Bradshaw, Roy Brown or Little Richard; and excited cries coming from the musicians (as heard here from those accompanying Billy Lee Riley, Gene Vincent, Johnny Burnette etc.) added extra character. Those who came from an urban milieu — Presley and his neighbours, the brothers Dorsey and Johnny Burnette — were still Memphis proletarians: spontaneous, and little-educated, they also belonged to the same category, i.e. artists who could give raw, well-felt performances. Conversely, from the same milieu came the Everly Brothers, Buddy Holly or Lew Williams (here alongside jazz guitar giant Barney Kessel, who’d been dropped out of the sky into a rock session), and they were more urbane, singing softly and with more sophistication. As for Eddie Cochran, he used to live in Los Angeles and quickly showed his strong singing personality: he was only seventeen when he recorded Pink Pegged Slacks.29

The stylistic purity of rockabilly lasted only three years, from 1954 to 1957. As Elvis Presley did, Eddie Cochran, Buddy Holly or Ricky Nelson quickly evolved towards new influences as early as 1956, opening new horizons for rock ‘n’ roll. Like Roy Orbison, who went on to show genuine vocal prowess, Johnny Cash and pianist Jerry Lee Lewis created their own styles (and they became schools). None of them, however (with the exception of Jerry Lee “The Killer”) would persevere and follow the original rockabilly road, as confirmed by the music heard in the second volumes of the sets devoted to Elvis Presley, Eddie Cochran and Gene Vincent in this series. Their styles would evolve, most often in a much more “presentable” direction. Faced with shame and scandal, many artists, among them Wanda Jackson, Ricky Nelson, Johnny Burnette, Elvis Presley, Gene Vincent and Conway Twitty, would have no choice but to distance themselves from the precious, wild sound you can hear in Maylon Humphries or Sammy Gowans.

Bruno BLUM

Adapted into English by Martin DAVIES

Thanks to Muriel Blum, Yannick Blum, Yves Calvez, Jacky Chalard, Gilles Conte, Guillaume Gilles, Christophe Hénault, Youri Lenquette, Slim Jim Phantom, Patrick Renassia (Rock Paradise), Lee Rocker, Brian Setzer and Marc Zermati.

© FRÉMEAUX & ASSOCIÉS 2014

1. The Shadows feature in Rock Instrumentals Story 1934-1962 (FA5426).

2. Cf. Roots of Punk Rock 1926-1962 (FA5415).

3. Cf. The Indispensable Eddie Cochran 1955-1960 (FA5425).

4. Cf. “Let’s Coast a While” by Hank Cochran as Bo Davis, with Eddie Cochran on guitar, in Road Songs - Car Tune Classics 1942-1962 (FA5401).

5. Cf. Country - Nashville-Dallas-Hollywood 1927-1942 (FA015).

6. Cf. Protest Songs (to be released).

7. Cf. Cajun - Louisiane 1928-1939 (FA019.

8. Cf. Country Gospel 1926-1946 (FA055).

9. The international influence is apparent in the volume Calypso 1944-1958 (boxed set Anthologie des Musiques de Danse du Monde, FA5342).

10. Cf. Electric Guitar Story - Country, Jazz, Blues, R&B, Rock 1935-1962 (FA5421).

11. Cf. Hawaiian Music 1927-1944 (FA035) and Hawaiians in Paris 1916-1926 (FA066).

12. Cf. Hillbilly Blues 1928-1946 (FA065).

13. Cf. the three albums Boogie Woogie Piano (FA036, FA5164, FA5226).

14. Cf. Western Swing - Texas 1928-1944 (FA032) and Bob Wills & his Texas Playboys 1932-1947 (FA164).

15. Listen to Arthur Smith on Rock Instrumentals 1934-1962 (FA5426) which includes “Guitar Boogie”, and on Guitare Country - From Old Time to Jazz Times 1926-1950 (FA5007).

16. Cf. Country Boogie 1939-1947 (FA160).

17. Cf. Electric Guitar Story 1935-1962 (FA5421) and Guitare Country - From Old Time to Jazz Times 1926-1950 (FA5007)

18. “Rockin’ at Home” by Floyd Dixon is included in Roots of Ska - USA-Jamaica rhythm and blues shuffle 1942-1962 (FA5396).

19. Cf. Honky Tonk Country Music 1945-1953 (FA5087).

20. The original version of Rocket 88 by Jackie Brenston is included in Road Songs - Classic Car Tunes 1942-1962 (FA5401). Both versions appear in Rock n’ Roll 1951 (FA357).

21. Cf. The Indispensable Bill Haley 1948-1961 (FA5465).

22. Cf. Rock n’ Roll : Volume 1 1927-1938 (FA351), Volume 2 1938-1946 (FA352), Volume 3 1947 (FA353), Volume 4 1948 (FA354), Volume 5 1949 (FA355), Volume 6 1950 (FA356), Volume 7 1951 (FA357) & Volume 8 1952 (FA359).

23. Cf. Ray Charles - Brother Ray: The Genius 1949-1960 (FA5350).

24. Cf. The Indispensable Bo Diddley 1955-1960 (FA5376) et 1959-1962 (FA5406).

25. Cf. The Indispensable Little Richard 1955-1958 (future release).

26. Cf. The Indispensable Chuck Berry 1954-1961 (FA5409).

27. Cf. The Indispensable James Brown 1956-1961 (FA5378).

28. Johnny “Guitar” Watson, Chuck Berry and Junior Parker with Pat Hare appear in Electric Guitar Story - Country, Jazz, Blues, R&B, Rock 1935-1962 (FA5421).

29. Cf. The Indispensable Eddie Cochran 1955-1960 (FA5425).

Disc 1 : 1951-1956

1. Rocket 88 - Bill Haley and the Saddlemen

(Jackie Brenston)

William John Clifton Haley as Bill Haley-v, g; Danny Cedrone-lead g; Billy Williamson-steel g; Johnny Grande-p; Al Rex-b. WVCH Radio Station Studio, Chester, Pennsylvania, June 14, 1951.

2. Rock the Joint - Bill Haley and the Saddlemen

(Harry Crafton, Wendell Keane aka Don Keane, Harry Bagby aka Doc Bagby)

William John Clifton Haley as Bill Haley-v, g; Billy Williamson-steel g; Johnny Grande-p; Marshall Lytle-b. Produced by Dave Miller. WVCH Radio Station Studio, Chester, Pennsylvania, April 1952.

3. Hound Dog - Jack Turner and his Granger County Gang

(Jerry Leiber, Mike Stoller)

Henry Doyle Haynes Jr. aka Henry Haynes aka Homer-v, g; Chester Burton Atkins as Chet Atkins-g; Kenneth Charles Burns aka Jethro-mandolin; Charles Green-electric bass; RCA Victor 47-5267, April 18, 1953. Probably WBAM Radio, Montgomery, Alabama circa March 1953.

Note: Jack Turner and his Granger County Gang is a pseudonym for Homer and Jethro.

4. That’s All Right - Elvis Presley

(Arthur Crudup)

The Blue Moon Boys: Elvis Aaron Presley aka Elvis Presley-v, g; Winfield Scott Moore II aka Scotty Moore-g; William Patton Black aka Bill Black-b. Produced by Sam Philips. Sun Studio, Memphis, Tennessee, July 5, 1954.

5. Just Because - Elvis Presley

(Sydney Robin, Joe Shelton, Bob Shelton)

The Blue Moon Boys: Elvis Aaron Presley aka Elvis Presley-v, g; Winfield Scott Moore II aka Scotty Moore-g; William Patton Black aka Bill Black-b. Produced by Sam Philips. Sun Studio, Memphis, Tennessee, September 10, 1954.

6. Good Rockin’ Tonight - Elvis Presley

(Roy Brown)

Same as above.

7. Drinkin’ Wine Spo-Dee-O-Dee - Malcolm Yelvington and the Star Rhythm Boys

(Granville Henry McGhee aka Sticks McGhee, Jay Mayo Williams aka Ink Williams)

Malcolm Yelvington-v, g; Gordon Washburn-g; Reece Fleming-p; Miles Winn aka Bubba-steel g; Jack Ryles-b. Produced by Sam Philips. Sun Studio, Memphis, Tennessee, November 11, 1954.

8. Baby, Let’s Play House - Elvis Presley

(Arthur Gunter)

The Blue Moon Boys: Elvis Presley-v, g/Winfield Scott Moore II aka Scotty Moore-g/William Patton Black aka Bill Black-b. Produced by Sam Philips. Recorded at Sun Studio, Memphis, Tennessee, February 5, 1955.

9. Cry! Cry! Cry! - Johnny Cash

(J. R. Cash aka Johnny Cash)

J. R. Cash as Johnny Cash-v, g; Luther Perkins-g; Marshall Grant-b. Produced by Sam Philips. Sun Studio, Memphis, Tennessee, May 1955.

10. Mystery Train - Elvis Presley

(Herman Parker aka Junior Parker, Julius Jeramiah Bihari as Jules Taub)

Same as 4. The Blue Moon Boys: Elvis Presley-v, g/Winfield Scott Moore II aka Scotty Moore-g/ William Patton Black aka Bill Black-b/unknown-p/Johnny Bernero-d. Produced by Sam Philips. Sun Studio8, Memphis, Tennessee, July 11, 1955.

11. Folsom Prison Blues - Johnny Cash

(J. R. Cash aka Johnny Cash)

J. R. Cash as Johnny Cash-v, g; Luther Perkins-g; Marshall Grant-b. Produced by Sam Philips. Sun Studio, Memphis, Tennessee, July 30, 1955.

12. Everybody Needs a Little Lovin’ - Merle Kilgore

(Dorothy Lee Salley, L.F. Fowler)

Wyatt Merle Kilgore as Merle Kilgore-v; Jim Landry-g; Sony James-fiddle; unknown b, d. Produced by Lew Chudd. Jim Beck Studio, 1914 Forest Ave., Dallas, August 31, 1955.

13. Whole Lotta Shakin’ Goin’ On - Roy Hall

(Mabel Smith aka Big Maybelle. However, the song was later credited to James Faye Hall aka Roy Hall aka Sunny David, Dave Williams aka Curlee Williams)

James Faye Hall as Roy Hall-v, p; Thomas Grady Martin as Grady Martin-el. g; possibly Walter L. Garland aka Hank aka Sugarfoot-el. g; Floyd T. Chance aka Lightnin’-b; Murrey M. Harman, Jr. aka Buddy Harman-d. Owen Bradley’s Bradley Film and Recording Studio, Nashville, 804 16th Avenue South, Nashville, September 15, 1955.

14. Rockin’ and Rollin’ - Sonny Fisher

(Sonny Fisher)

Sonny Fisher-v, g; Joey Long-lead g; unknown b, d. Gold Star Studio, 5628 Brock St., Houston, circa October, 1955.

15. Love Me - Buddy Holly

(Sue Parrish, Charles Hardin Holley aka Buddy Holly)

Charles Hardin Holley as Buddy Holly-v; Sonny Curtis-lead g; Don Guess-b; Jerry Allison-d. Wichita Falls, December 7, 1955.

16. Blue Suede Shoes - Carl Perkins

(Carl Perkins)

Carl Perkins-v, g; Jay Perkins-rhythm g; Clayton Perkins-b; W.S. Holland-d. Produced by Sam Philips. Sun Studio, 706 Union Ave., Memphis, December 17, 1955.

17. Honey Don’t - Carl Perkins

(Carl Perkins)

Same as above.

18. Sleepy Time Blues - Jess Hooper and the Daydreamers

(Jess Hooper, Lester Louis Bihari)

Doug Cox-lead g; Jess Hooper-v; Clyde Rush-g; Tommy Sealey-fiddle; Millard Yow-steel g; Bill Torrence aka Shorty-b. Meteor Studio, 1794 Chelsea Avenue, Memphis, 1955.

19. Mama’s Little Baby - Junior Thompson with the Meteors

(Quinton Claunch)

Junior Thompson-v; Terry Thompson-lead g; Raymond Lovelace-lead g; Quinton Claunch-g; Don Moore-g; Monty Olive-p; Jimmy Lovelace-b; Johnny Bernero-d. Produced by Lester Bihari. Meteor Studio, 1794 Chelsea Avenue, Memphis, circa January 5, 1956.

20. Raw Deal - Junior Thompson with the Meteors

(Quinton Claunch, William Cantrell)

Same as above.

21. Midnight Shift - Buddy Holly

(Jimmy Ainsworth, Earl Lee)