- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

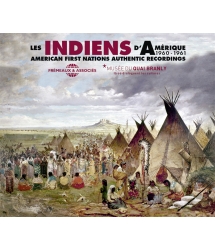

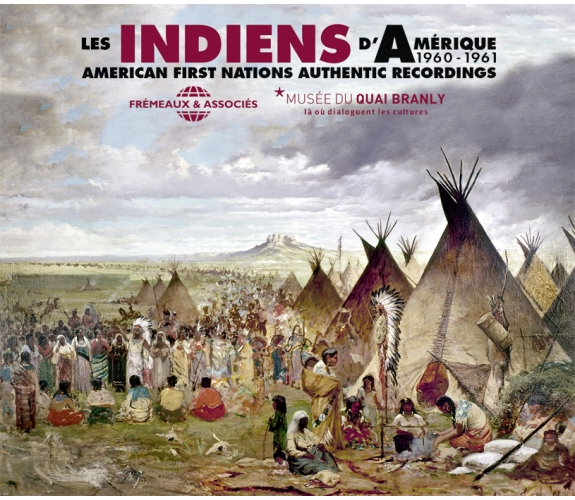

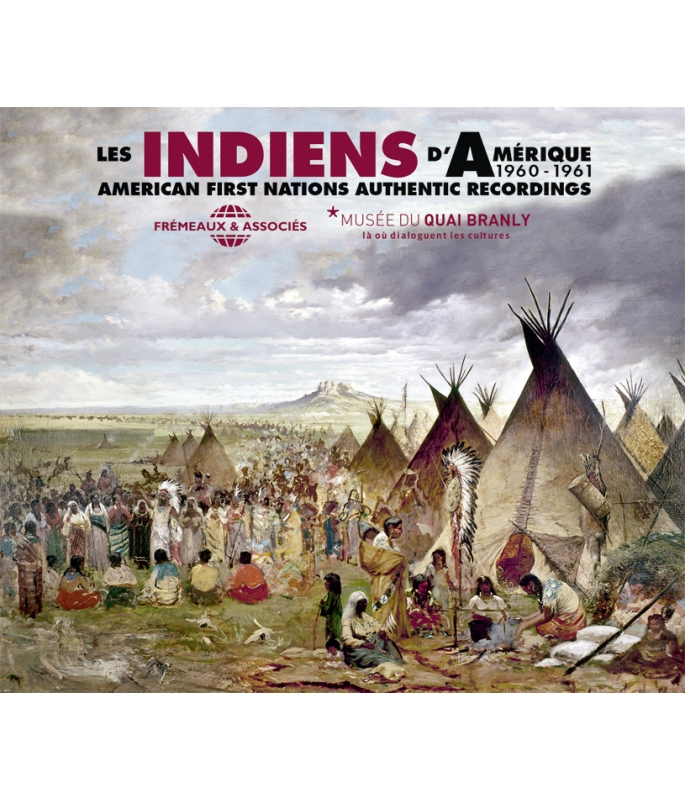

AMERICAN FIRST NATIONS AUTHENTIC RECORDINGS 1960-1961

LOLA CAUL-FUTY FREMEAUX

Ref.: FA5454

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Total duration of the pack : 1 hours 34 minutes

Nbre. CD : 2

AMERICAN FIRST NATIONS AUTHENTIC RECORDINGS 1960-1961

AMERICAN FIRST NATIONS AUTHENTIC RECORDINGS 1960-1961

Symbol of a dedication to uphold their culture and resist the expanding hegemony of Western settlers, Native American songs have acquired a mythical aura, branded in our collective imagination by the movie industry. They are the tribal expression and intangible heritage of the First Peoples in American history. Healing rituals, praises of the warrior’s bravery, celebrations of spirits or stars, they are living proof that singing is a collective act of sharing. This set offers an anthropological perspective on the diversity of Native American great cultures, Cheyennes, Poncas, Sioux, Apaches, Utes or Crows… presented with historical recordings dating from before the contemporary accultu ration process and an extensive ethnological booklet. This anthology, sound illustration of the Parisian exhibit Les Indiens des Plaines presented by the Musée du Quai Branly, takes the auditor to the most authentic and fascinating cultures in North America. Lola CAUL-FUTY FRÉMEAUX

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Fast Cheyenne War DanceCheyenne Dave GroupTraditionnel00:02:051960

-

2Ponca Helushka DanceChief Spotted Back HamiltonTraditionnel00:02:531960

-

3Fast Sioux War DanceOglala Sioux SingersTraditionnel00:02:061960

-

4Arikara War DanceWhite Shield Singers Of North DakotaTraditionnel00:01:431960

-

5My Enemy, I Come After Your Good White Horse (Arikara)White Shield Singers Of North DakotaTraditionnel00:01:231960

-

6Fast Cheyenne War DanceMorris MedecineTraditionnel00:02:391960

-

7Omaha HelushkaChief Spotted Back HamiltonTraditionnel00:02:191960

-

8Ponca War DanceChief Spotted Back HamiltonTraditionnel00:01:461960

-

9New Taos War Dance SongAdam Trujillo & The Taos SingersTraditionnel00:02:361960

-

10Kiowa Slow War DanceDavid Apakaun & The Kiowa SingersTraditionnel00:02:411960

-

11Kiowa Fast War DanceWm. Koosma & The Kiowa SingersTraditionnel00:01:241960

-

12Bloody Knife's Warrior Song (Arikara)White Shield Singers Of North DakotaTraditionnel00:01:351960

-

13Chief's Honoring Song (Sioux)Oglala Sioux SingersTraditionnel00:02:491960

-

14The Old Glory Raising On Iwo Jima (Navajo)Reg BegayTraditionnel00:02:301960

-

15Korea Memorial Song (Sioux)Oglala Sioux SingersTraditionnel00:01:441960

-

16Navajo Hoop Dance SongRoger McCabeTraditionnel00:02:191960

-

17I'M In Love With A Navajo BoyPatsy CassadoreTraditionnel00:02:121960

-

18Navajo Gift Dance SongJoe Lee Of Lukachuchai With GroupTraditionnel00:01:411960

-

19Crow Push Dance SongDonald DeernoseTraditionnel00:02:361960

-

20Pawnee Hand Game SongLaurence Good Fox & Laurence MurieTraditionnel00:01:211960

-

21Shawnee Stomp DanceLittle Axe SingersTraditionnel00:02:391960

-

2249 Dance Song (Plains)Rough Arrow & The Phoenix Plains SingersTraditionnel00:02:341960

-

23The Prisoner's Song TewaLeo And Valentino LecapaTraditionnel00:03:011960

-

24Girl Who If Afraid Of Boys (Apache)Philip CassadoreTraditionnel00:01:531960

-

25The Bear Dance UteBert Red, Mrs Bert Red, Eddie Box & James MillsTraditionnel00:03:061960

-

26Mountain By The Sea PimaDan Thomas & Paul MartinTraditionnel00:03:141960

-

27The Mescalero Train (Apache)Patsy Cassadore & Murray CassaTraditionnel00:02:081960

-

28Montana Grass SongFt. Peck Sioux SingersTraditionnel00:02:431960

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Apache Mountain Spirit SongC. Hoffman & The San Carlos ApachesTraditionnel00:03:121961

-

2Lighting Song (Apache)Dick Young & The San Carlos ApachesTraditionnel00:02:221961

-

3Sun Dance Song (Cheyenne)Northern Cheyenne SingersTraditionnel00:02:311961

-

4Sun Dance Song (Arapahoe)Northern Arapahoe SingersTraditionnel00:02:501961

-

5Ute Sun DanceBert Red, Mrs Bert Red, Eddie Box & James MillsTraditionnel00:02:121961

-

6Song Of The Black Mountain (Papago-O'odham)Big Fields VillagersTraditionnel00:01:521961

-

7Song Of The Green Rainbow (Papago O'odham)Big Fields VillagersTraditionnel00:01:341961

-

8Navajo Yei Be Chai (Chant)Mesa Verde Group SingersTraditionnel00:02:591961

-

9Zuni Buffalo DanceL. Shebaba, Mallon & R. GasperTraditionnel00:03:301961

-

10Hopi Basket DanceHopi Singers from 2nd MesaTraditionnel00:02:061961

-

11Our Father's Thoughts Are Shining Down (Paiute)Wilbur JackTraditionnel00:02:411961

-

12Ceremonial Song (Paiute)Johnny BuffaloTraditionnel00:03:161961

CLICK TO DOWNLOAD THE BOOKLET

Les Indiens d'Amérique FA5454

LES INDIENS D’AMÉRIQUE

AMERICAN FIRST NATIONS AUTHENTIC RECORDINGS

1960-1961

Par Lola Caul-Futy Frémeaux

Le Nouveau Monde s’est peuplé lentement, par l’afflux intermittent de groupes effectuant la traversée entre la Sibérie et l’Alaska sur une période de 15 000 ans. Sur quelques sites, principalement dans le sud-ouest des États-Unis, les traces archéologiques des premiers arrivants ont été mises à jour. On y a retrouvé divers outils faits de silex, d’os et de bois, ainsi que les restes de leurs feux de camp, avec les os des animaux qu’ils chassaient.

Les peuples qui arrivaient de Sibérie étaient dans des situations difficiles. La pointe de la Sibérie est une région hostile, extrémité vers laquelle se trouvaient repoussées les tribus trop faibles pour forcer leur chemin vers des terres plus hospitalières. Lorsqu’une découverte était faite, que ce soit en Europe, en Chine, en Inde, en Asie mineure ou au sud de la Méditerranée, le nouveau savoir se généralisait sur une période d’environ mille ans. Cependant l’arrivée de telles découvertes en Sibérie était particulièrement longue, voire inexistante. Déserts, grandes étendues et chaines de montagnes tenaient ses habitants isolés.

La traversée vers le Nouveau Monde de la majorité de sa future population s’est faite avant toutes les découvertes majeures. Certains ont traversé avant même la domestication du chien. La technique de datation au carbone 14 de restes de charbon indique que de premiers Indiens avaient atteint le Nouveau Mexique il y a 20 000 ans ; bien avant que l’humanité ne soit sortie de la première phase de l’Age de pierre, le paléolithique. Comme tous les hommes de leur temps, ils n’avaient ni poterie, ni vannerie ; dans un premier temps, ils n’avaient pas même d’arcs et de flèches. Ils chassaient avec des lances, des fléchettes ou des javelots. Cependant, en progressant vers le Sud, les territoires se faisaient de plus en plus riches en gibier et avec leurs armes simples, ils pouvaient abattre des paresseux aussi gros que des ours, mais aussi des éléphants, des mammouths et des bisons à la taille bien supérieure à celle des bisons de nos jours.

Tous les immigrants ne se ressemblaient pas. Leurs tailles et la morphologie de leurs crânes étaient variables. On retrouve également chez les Indiens d’Amérique d’aujourd’hui des colorations de peau plus ou moins sombres, ce qui laisse supposer que leurs ancêtres étaient d’origines ethniques diverses. La majorité venait cependant d’Extrême-Orient, et l’héritage de traits physiques se rapprochant de ceux des Mongoles constitue une unité des peuples amérindiens.

On trouve la preuve qu’au cours de 15 000 ans, de nombreux et différents peuples sont parvenus jusqu’au Nouveau Monde dans la structure des langages. Les langues parlées pas les Amérindiens aujourd’hui appartiennent à des familles totalement différentes, aussi différentes que le Français l’est du Tibétain ou du Zoulou. Demander à quelqu’un «Parlez-vous Indien ? » est aussi ridicule que de demander « Parlez-vous européen?». L’Amérique du Nord et du Sud se sont peuplées. Dans le reste du monde, de nombreuses découvertes ont été faites et partagées, mais elles n’ont pas pu atteindre le Nouveau Monde. Les Amérindiens ont dû tout créer, et ce face à une nature qui n’était pas à leur avantage. En Amérique, très peu d’animaux peuvent être domestiqués (comme vous le confirmera tout cowboy qui a tenté de diriger un troupeau de bisons !). Les seuls animaux à avoir une taille décente sont les lamas du Pérou, assez gros pour porter de légers fardeaux mais trop petits pour tirer un attelage dans les régions montagneuses. Ailleurs dans le monde, il y avait des chevaux, des bovins, des éléphants domptables en Asie, des chameaux, des chèvres, des moutons et des porcs, mais aussi des poulets, des canards et des oies. Les Amérindiens sont parvenus à élever et domestiquer les dindes, mais les oiseaux ne sont guère utiles au travail. Comme les éléphants d’Afrique, les grands animaux d’Amérique n’étaient pas domesticables.

De même, ailleurs existaient de nombreuses sortes de céréales dont il suffisait de semer les graines en terre fertile, comme le blé, le seigle, l’avoine, l’orge ou le millet. En Amérique, seul le maïs existe. Or, le maïs ne peut pas être semé à la volée, il faut placer chaque graine dans son petit trou. Il fallut bien des siècles d’expérimentation pour développer une plante nouvelle, pour transformer une herbe folle en une plante capable de produire une récolte convenable. Il serait même possible que le maïs soit le résultat du croisement de deux plantes sauvages, aucune n’ayant à la base le potentiel d’être cultivée. Ainsi, le développement du maïs actuel est le résultat d’une recherche intelligente et collective des Amérindiens.

Aux Amériques, l’histoire des civilisations ressemble à toute autre : de grands centres de culture se sont créés dans les régions centrales. Incas, Toltèques ou Mayas en sont pour nous les noms les plus connus aujourd’hui. Ils conçurent des cités à l’architecture travaillée, aux arts délicats ; ils développèrent des formes d’écriture, les mathématiques et l’astronomie. Bien que ces civilisations utilisent des outils de pierre, elles sont extrêmement loin de ce que l’on pourrait appeler l’Âge de pierre. Elles étaient proches du transfert vert le maniement du métal et travaillaient déjà l’or, l’argent et le cuivre, mais dans l’art ornemental principalement.

Partout, que ce soit en Europe, en Afrique ou en Asie, des vagues successives de barbares attaquaient les centres de civilisation, les conquéraient, devenaient civilisées à leur tour et continuaient la lignée du progrès. Le même processus est intervenu aux Amériques. Par exemple, un peuple barbare au langage Uto-aztèque est descendu du Nord pour envahir les cités du Mexique central. Ils ont conquis les anciens Toltèques (ce qui signifie « maîtres bâtisseurs ») et se sont approprié leur civilisation pour devenir les Aztèques.

L’influence des centres de civilisation s’est étendue progressivement, ce qui lui a permis d’atteindre les États-Unis d’aujourd’hui par deux portes d’entrée principales : le sud-est et le sud-ouest.

Le Sud-ouest Américain

Le « Sud-ouest » signifie pour les spécialistes d’histoire amérindienne l’Arizona et le Nouveau Mexique, avec quelques bandes étroites des territoires alentours appartenant aujourd’hui au nord du Mexique et au sud du Colorado et de l’Utah. Plusieurs milliers de kilomètres de désert aride et de terrain montagneux séparent cette zone des villes du sud, situées au Mexique central, mais le commerce parvenait à les connecter, bien qu’indirectement. Les échanges se faisaient successivement, de tribu en tribu, et passaient par de nombreuses étapes pour lier ces deux centres d’activité. Les peuples civilisés achetaient de la turquoise et revendaient notamment des plumes de perroquet et des graines. Mais plus important encore, les idées circulaient ; l’idée de cultiver la terre, de tresser des paniers, de faire de la poterie, de porter des masques pour symboliser les êtres sacrés.

L’histoire du Sud-ouest dans les temps anciens nous est bien mieux connue que celle des autres parties des États-Unis pour deux raisons principales. Il y a 2 000 ans, le sud-est était déjà défini par un climat sec, bien que pas aussi aride que celui d’aujourd’hui ; les traces laissées par les peuples sont donc restées bien mieux conservées mais aussi bien mieux repérables, grâce à une végétation peu abondante. Il est facile pour les archéologues de savoir où entreprendre leurs fouilles. De plus, bien des tribus qui vivent dans le Sud-ouest aujourd’hui sont les descendants directs de ceux qui y vivaient il y a plus de 1000 ans. Oraibi, un village Hopi, est resté constamment habité depuis l’an 1100. Les indiens modernes y pratiquent encore de nombreuses coutumes ancestrales et peuvent nous transmettre un éclairage unique sur leurs traditions et leur histoire.

Dès que les conditions le leur permettaient, les peuples du sud-ouest entreprenaient de cultiver la terre, d’abord avec des haricots locaux, puis avec du maïs venu du sud. Beaucoup ont développé l’irrigation, d’autres se sont spécialisés dans la culture sur sol sec. Ils maîtrisaient la vannerie, plantaient et tissaient le coton et façonnaient de la magnifique poterie. Ils sculptaient aussi de beaux bijoux en turquoise ou en coquillages et ornaient de motifs taillés les petits objets en pierre du quotidien.

De grandes différences culturelles séparaient les peuples des cultivateurs du Sud-ouest tels que les Pueblos, les Hohokams, les Mimbres et les Mogollons (prononcé : «mogoïonnes »). Les plus connus sont les Pueblos, de par leurs spectaculaires ruines mais aussi parce que leur culture reste particulièrement bien préservée par leurs descendant Hopis et Pueblos. La branche principale des Pueblos est originaire de la frontière entre le Colorado et l’Utah. Ils se sont ensuite déplacés vers le sud et ont construit des villages aux maisons de pierres cimentées par de l’adobe, une argile locale. Chaque village détenait une ou plusieurs kivas, pièces spéciales servant de centres pour les réunions et les cérémonies religieuses. Leur forme de base était dérivée des premiers habitats amérindiens antérieurs à la découverte de la maçonnerie, c’est à dire d’une seule pièce circulaire et enterrée, disposant d’un toit arrondi avec une ouverture en son milieu qui tenait lieu de porte. Leur architecture a largement évolué au cours des siècles jusqu’à ne plus ressembler au bâtiment d’origine ; sur les périodes les plus tardives, les murs étaient ornés de représentations artistiques et stylisées de thèmes rituels.

Le Sud-ouest dispose de peu de collines, on y trouve cependant de nombreuses mesas, formations rocheuses aux plateaux élevés et aux versants très abrupts. Lorsque de larges portions de ces versants s’érodent et s’éboulent, des surfaces planes se libèrent dans les flancs de la falaise. Il y a 2 000 ans, les indiens du Sud-ouest s’installaient souvent sur ces saillies, et se protégeaient ainsi efficacement des éléments. De véritables villes s’y sont même développées, bien que cela implique pour les femmes de longs trajets quotidiens sur des terrains escarpés et rocailleux pour aller chercher l’eau, les récoltes et toutes les matières premières. Ces villes, très photogéniques, n’étaient pas des plus pratiques.

C’est sans doute en raison de l’arrivée de tribus moins établies, entre le IXème et le XIème siècle, que s’est produit l’installation dans ces lieux défendables. Parmi les nouveaux arrivants se trouvaient les Apaches et les Navajos, tribus encore très connues aujourd’hui. Ils s’étaient séparés de tribus sédentarisées en Alaska et au Canada et se présentaient pauvres et sans savoirs pratiques, mais armés d’arcs de type arctique et d’origine asiatique dont la puissance était supérieure à celle des arcs traditionnels du Sud-ouest ; ce seul fait leur donnant l’avantage militaire. Les nouveaux arrivants ne déclarèrent pas une guerre régulière contre les Pueblos, ils faisaient du commerce, apprenaient l’artisanat, et organisaient de temps à autre des raids rapides sur un village. Ils constituaient une nuisance suffisante pour encourager les Pueblos à s’installer de manière plus regroupée sur des hauteurs défendables.

Plus tard, lorsqu’ils se sont déplacés vers d’autres régions, ils ont conservé l’habitude de construire leurs villes sur des hauteurs ou concevaient l’alignement des maisons pour qu’elles forment elles-mêmes un mur de défense et d’enceinte.

La culture du Sud-ouest était essentiellement pacifique et démocratique. Nous n’avons retrouvé que peu de traces de combats malgré les soucis causés par les tribus nomades et plus primitives qui s’invitaient dans la région. Nous ne retrouvons pas de tombeaux élaborés ou mises en terre distinctes qui indiqueraient une forte séparation de rangs au sein de la société. Il n’y a pas non plus de maisons particulièrement grandes ou ornementées. Les indiens Pueblos d’aujourd’hui forment toujours une communauté pacifique et démocratique. Le travail nécessaire à la construction des kivas est fourni collectivement et entrepris par volontariat.

Dans les temps anciens, le gouvernement était de type théocratique, c’est à dire que les prêtres et les représentants religieux exerçaient le pouvoir. Mais ce pouvoir était librement consenti pas les gouvernés : leurs vies se centraient principalement sur la religion. Les témoignages des premiers espagnols à les avoir rencontrés indiquent leur appréciation pour l’architecture, l’agriculture et les arts, mais surtout leur admiration des magnifiques cérémonies religieuses des Pueblos.

La culture du Sud-ouest ne se s’est jamais beaucoup étendue au-delà de l’Arizona, du Nouveau-Mexique et des parties sud du Colorado et de l’Utah. Tous les alentours sont en effet constitués de hautes montagnes ou de déserts qui n’étaient pas cultivables avec les équipements de l’époque. Quand vos meilleurs outils sont faits de bois durci et d’os, il est difficile d’irriguer le Grand Désert américain. A l’est, les Hautes Plaines étaient également mal adaptées à la culture pour un outillage primitif. Et comme certains cultivateurs aventureux le découvrent aujourd’hui, elles sont simplement mal adaptées à la culture, même avec un outillage technologique.

Le Sud-est Américain

L’autre région de développement de la culture Amérindienne, située au Sud-est, est extrêmement différente. En raison de l’erreur initiale de Christophe Colomb qui croyait avoir découvert les Indes, nous avons placé tous les habitants d’un continent sous le terme générique « indiens ». Parce que ce terme est le même pour tous, il est facile de penser qu’ils se ressemblent tous. En réalité, les peuples du Sud-ouest et les peuples du Sud-est sont aussi différents que peuvent l’être deux populations partageant un vaste continent.

Nous ne connaissons pas en aussi grand détail l’histoire des peuples du Sud-est, et nous ne pouvons pas la remonter sur une très longue période. Nous savons qu’il y a un millénaire, une culture remarquable s’est étendue du Golf du Mexique, le long de la vallée du Mississippi et presque jusqu’aux Grands Lacs. Il s’agissait également d’une culture basée sur l’agriculture. Nous l’appelons la culture des « Mound Builders », ce qui signifie «bâtisseurs de tumulus», car les tumulus, ou tertres constituent la partie la plus visible de l’héritage qu’ils nous ont laissé.

On peut clairement distinguer une influence centre-américaine directe dans cette culture. Ses caractéristiques, comme la confection de manteaux de plumes ou la stricte définition d’une aristocratie, se retrouvent dans les grandes civilisations du Mexique. L’un des points les plus frappants vient tout simplement des tertres eux-mêmes.

Les Toltèques, les Aztèques et les Mayas bâtissaient des pyramides à sommet plat sur lesquelles ils plaçaient leurs temples et parfois leurs palais. Ils construisaient avec de la pierre, du mortier, et une forme de ciment. Les pyramides et les bâtiments à usage administratif ou religieux étaient arrangés de manière impressionnante pour les habitants des alentours. Les peuples le long du Mississippi suivaient une logique similaire, bien que le style et l’architecture ne soient pas parvenus au même degré de raffinement. Les tertres, formés de rocailles couvertes de terre, et les bâtiments faits de bois et d’osier, reprenaient avec les techniques de construction disponibles, mais les formes et silhouettes des bâtiments du Mexique.

Au nord, une architecture indépendante de tertres s’est développée, en prenant des formes d’animaux à la symbolique particulière. Soit les tertres eux-mêmes prenaient la forme de leur effigie, soit une sculpture de terre la représentant était placée au sommet du tertre traditionnel.

Les populations vivaient dans des villages relativement permanents, dans des maisons construites autour d’un pilier central avec des murs et des toits faits de chaume tressé. Ils pratiquaient l’agriculture extensive ; la population totale des États-Unis ne comptait pas plus d’un million d’habitants avant l’arrivée des colons occidentaux et personne ne manquait de place. Une large partie de l’alimentation venait de la chasse et de la pêche dans un environnement d’abondance. Le temps des habitants était donc divisé entre ces différentes activités. L’art, très présent, s’exprimait principalement par la sculpture.

La vallée du Mississippi, avec sa nature hospitalière et sa population peu dense, était une cible bien tentante pour les peuples moins établis des régions avoisinantes. On pense les Mound Builders ont été conquis quelques siècles avant l’arrivée des colons et bien que la nouvelle culture issue de cette conquête ait conservé l’influence mexicaine sur bien des aspects culturels, la construction de grands édifices s’est interrompue.

Les Natchez semblent cependant avoir survécu à la conquête ; ils descendraient directement des Mound Builders. Ce peuple, unique parmi les indiens d’Amérique du Nord, avait un monarque absolu. Le roi, appelé «Le Grand Soleil », était si sacré qu’il ne devait pas se souiller en touchant terre ; il était porté en permanence en litière. Il était habillé d’un impressionnant manteau de plumes et couronné de grandes plumes multicolores. Des volontaires se faisaient ses serviteurs et acceptaient de se faire exécuter lors de la mort du Grand Soleil, afin de l’accompagner dans l’Au-delà. Il détenait un pouvoir absolu sur tout son peuple.

Le peuple Natchez se divisait en deux catégories : les aristocrates et les roturiers. L’aristocratie était subdivisée en trois classes d’importance décroissante, les Soleils, les Nobles et les Honorables. Le reste du petit peuple était communément appelé les Puants. Cette organisation particulière voulait que le simple peuple puisse se marier sans contrainte, mais que chaque membre de l’aristocratie soit dans l’obligation de s’allier à un membre des Puants. Quand un homme aristocrate épousait une roturière, leurs enfants appartenaient à la caste au-dessous de celle de l’aristocrate ; ainsi les enfants d’un homme Honorable étaient des roturiers. Quand une femme aristocrate épousait un Puant, leurs enfants conservaient le titre de leur mère. En conséquence, le Grand Soleil lui-même était le fils d’un Puant.

Trop souvent la singularité des peuples amérindiens est oubliée. Les conquêtes, les migrations, le commerce et toutes les interactions entre les cultures formaient un terreau fertile aux nouvelles découvertes et au développement de grandes civilisations. L’arrivée des conquistadors, dont la supériorité se résumait à quelques avantages clés tels que les chevaux, l’acier et la poudre à canon, ont réduit en un siècle des centaines de cultures à néant. Cultures dont il est aujourd’hui difficile de retrouver l’histoire.

Spiritualité

Héritage de visions de personnalités inspirées ou d’usages dont nous avons perdu la trace, au sein de nombreuses tribus les reliques sacrées sont fondamentales, comme les flèches sacrées de Cheyennes, ou plus simplement ce que l’on a appelé les « paquets médicinaux. » Les noms sont défaillants. Bien des possessions indiennes ont été nommées par des Blancs méprisants ou ignorants, voire les deux à la fois.

Ils ont vu des indiens combiner la religion et les soins médicaux, comme nous le faisions en Europe jusqu’il y a peu ; ils ont donc appelé les représentants de la religion «guérisseurs ». Ils ont vu les indiens emballer des objets qu’ils considéraient sacrés dans différents petits paquets, souvent savamment décorés, mais quand ils furent autorisés à voir ce qu’ils contenaient, ils réagirent avec dédain. Ils constatèrent que ces paquets, ou leur contenu, étaient parfois utilisés pour la guérison des malades alors ils les ont appelés « paquets médicinaux ».

Il serait aussi erroné de nommer la croix chrétienne « bâton guérisseur » en voyant au XVème siècle les hommes de Cabeza de Vaca poser un croix sur leurs malades en priant pour leur rétablissement.

Nous nous en tenons donc au nom de « paquets sacrés », pour représenter «tlaquimilolli,» ce qui signifie « chose enveloppée dans un tissu » en nahuatl, langue de la famille uto-aztèque.

Nombre de ces paquets étaient détenus individuellement, passés de générations en génération ou enterrés avec leur propriétaire. D’autres appartenaient à tout le clan pour un usage lors des cérémonies majeures. Chez les Algonquiens, à part chez les Cheyennes, les paquets appartenaient plutôt au clan et les grandes cérémonies pour les moissons se faisaient de manière collective. Le propriétaire d’un paquet enseignait à son successeur le déroulement du rituel avec les chants et les prières nécessaires. Lui seul pouvait alors mener à bien la cérémonie, ce qui en faisait, selon nos définitions, des prêtres.

Les tribus du nord, à l’est et à l’ouest du Mississippi, accordait un rôle spécifique au calumet, ou pipe sacrée. Les pipes étaient portées lors de certaines danses, utilisées comme passeport par les messagers et trouvaient leur place dans de nombreux rituels. Une pipe ornée de plumes rouges signifiait la guerre, quand des plumes blanches signifiaient la paix.

Le foyer de la pipe était fait d’une pierre spéciale, la catlinite, que l’on trouve au Minnesota, sur les terres des Sioux, peuple étranger à l’agriculture. Cette pierre a la particularité d’être très malléable lorsqu’elle vient d’être extraite du sol, et de durcir rapidement ensuite. Le foyer donnait sur une tige particulièrement longue et très ornementée. Certaines pipes pouvaient être fumées pour le simple plaisir, il n’était alors pas nécessaire d’utiliser le tabac cultivé selon les rites prescrits. D’autres pipes étaient réservées aux cérémonies. Souvent, le fait de fumer était réservé aux individus ayant atteint un certain rang dans la tribu.

Dans le Sud-est, le chemin vers la gloire et l’ascension sociale passait par les exploits de guerre, ce qui menait souvent les jeunes hommes à la recherche de la violence ; les trophées, tels que les scalps ou autres parties du corps de l’ennemi, venant prouver les faits. Ramener un prisonnier au village à des fins de torture était aussi une preuve de force. Pour les peuples du Sud-ouest, la torture ne tenait pas cette place. La bravoure étant la valeur suprême, le plus grand exploit était en toute logique de s’attaquer à main nues à un homme armé et entouré de ses camarades. Les embuscades n’étaient pas une source d’honneur et l’objectif principal n’était donc pas de tuer, sauf dans les quelques rares occasions de réelles guerres entre tribus.

Scalper les ennemis vaincus se faisait régulièrement mais ne constituait pas le cœur de l’objectif pour le guerrier. Avant de partir pour un raid ou une bataille, afin de se mettre en condition, ou lors du retour pour célébrer la victoire, les hommes dansaient. La danse de la victoire est généralement dite la « danse du scalp » puisque les trophées rapportés y sont exhibés. Les guerriers mettent en scène de manière stylisée toutes les étapes du combat, depuis le début de la traque – se penchant en avant pour pister l’ennemi, les sauts de l’attaque, ou les parades de défense – jusqu’à la victoire. Le jeu de jambes est léger et rapide, en rythme avec les chansons joyeuses, toujours jolies et parfois d’une grande beauté, accompagnées de tambours. Des danses semblables étaient également organisées simplement pour le divertissement. La danse étant individuelle et laissant une large part à l’improvisation, elle se fait sans répétition, dans l’énergie et l’écoute collective. Les chants et danses populaires des Premiers Peuples d’aujourd’hui sont des évolutions de ces danses de guerre originelles.

La fanfaronnade était partie intégrante de l’exercice guerrier. Au cours d’évènements organisés dans ce but, le guerrier faisait face au public pour réciter ses exploits sans modestie aucune, mais dans les limites de la vérité. Chacun savait ce dont pouvait se vanter un guerrier et s’il tentait d’usurper la gloire d’un autre ou de s’en inventer une, il était hué et disgracié. Les colons blancs adoptèrent rapidement cette coutume, qu’ils arrangèrent et épicèrent d’une forte consommation de whiskey, et créèrent leur propre tradition de fanfaronnades, les « brags » des frontaliers.

Le combat relevait du sport et s’organisait selon les initiatives individuelles. La chasse était bien plus sérieuse. Les parties de chasse étaient souvent organisées avec soin. Dans la plupart des cas, les chasseurs n’étaient pas autorisés à partir sans l’autorisation des chefs afin que personne ne risque de disperser le gibier par sa précipitation. Ce contrôle était particulièrement strict concernant la chasse au bison. Le tipi fut probablement inventé en Arctique pour se prémunir du froid, mais permet également de se protéger de la chaleur, quand nos tentes, exposées au soleil, deviennent rapidement d’une chaleur intolérable.

Les peuples cultivateurs utilisaient leurs tipis principalement pour la période de la chasse au bison, qu’ils organisaient annuellement lors du passage vers leurs terres des troupeaux en migration. La chasse au bison était un exercice difficile. Pour un homme à pied simplement armé de flèches aux pointes de pierre taillée, faire face à des animaux au cuir épais et prompts à défendre leurs femelles et leurs petits, constituait un danger réel.

La principale technique de chasse passait donc par l’organisation de la débandade du troupeau en mettant le feu aux hautes herbes de leurs pâturages pour les pousser, soit vers un précipice, soit vers une rangée d’archers. La quantité de bisons tués se limitait à ce que les chasseurs pouvaient sécher ou fumer et rapporter au village, ce qui équivalait à ce que les femmes pouvaient porter sur leur dos et aux petites quantités ajoutées aux fardeaux déjà traînés par les chiens. En effet, ils ne disposaient ni de la roue, ni de chariots et se servaient donc de travois : deux perches d’armature de tipi, entre lesquelles était disposée la charge, s’attachaient au harnais du chien et trainaient pas terre à leur autre extrémité. En hiver, grâce à des luges, les tribus du nord pouvaient transporter de plus lourdes charges, mais l’hiver ne correspond pas à la période de la chasse au bison.

Dans toute la région, on peut constater des signes d’interactions avec le Sud-est. Dans la plupart des tribus, comme les Natchez, les Creeks ou les Iroquois, les clans viennent diviser une tribu, souvent en deux mais parfois en plus de sous-groupes. Par défaut les membres d’un même clan se considéraient comme appartenant à la même famille, et pouvaient compter sur l’aide et la coopération d’autrui. En raison de cet esprit de famille, certains clans, exogames, interdisaient les mariages de deux personnes issues d’un même clan. Les enfants s’identifiant plutôt au clan de leur mère.

Les chefs de tribus étaient clairement identifiés, dans leur rôle et leurs prérogatives. Nommés à vie, ils transmettaient parfois leur fonction de manière héréditaire. Beaucoup de tribus, surtout dans le nord, faisaient cohabiter les « chefs de guerre », organisateurs de raids et les « chefs de paix », administrateurs de la vie quotidienne. Lorsque Tecumseh a organisé l’alliance des tribus algonquines contre les États-Unis, il a fait savoir que « les chefs », c’est à dire les administrateurs, cédaient le pas au chef de guerre.

Les jeunes hommes partaient à la recherche de visions, souvent au cours de périodes d’isolement dans la nature. Les visions, manifestations de la visite d’un être surnaturel, indiquaient à chaque homme des éléments de son futur. Par exemple, les Iroquois mesuraient ainsi leur niveau d’orenda, cette force accordée par l’invisible mais omniprésent dieu des algonquins. Grâce à des visions intenses, un homme pouvait devenir shaman, et donc lire l’avenir, donner des nouvelles d’être chers partis au loin, ou encore diagnostiquer les maladies – bien qu’il laisse généralement aux spécialistes le soin de la réalité du traitement médical. Remettre des os fracturés ou préparer des herbes médicinales faisaient souvent partie de leurs compétences, mais ils recourraient également à des tours dans le but d’impressionner.

Lors de grandes cérémonies, seuls les shamans pouvaient officier. Atteindre le rôle de shaman pouvait se faire de manière plus ou moins formelle selon les tribus, à la suite d’une période d’apprentissage à la durée variable. Chez les Pawnees, l’entraînement de nouveaux shamans pouvait s’apparenter à la formation de prêtres, qui héritaient leur charge de leur père. Parmi eux, cinq prêtres, dont le plus important était associé à l’étoile du soir, étaient de fait plus puissants que les chefs. Les Pawnees pratiquaient le culte du soleil ainsi que des étoiles ; ce qui incluait la Cérémonie de l’Étoile du Matin. Lors de cette cérémonie, une jeune fille capturée au cours de l’année était sacrifiée. Pendant sa période de captivité, plus ou moins longue, elle était bien traitée, laissée libre de ses mouvements dans le village, et tenue ignorante de son sort. Trois jours avant la date fatidique, elle était déshabillée et peinte sur tout le corps, puis considérée comme une personne sacrée par tout le village.

Le quatrième jour, avant le lever de l’étoile du matin, la jeune fille était conduite à un échafaud. Il était de bon augure qu’elle y monte volontairement, car toujours ignorante de son tragique destin. Elle était attachée, et les prêtres symbolisaient la torture qu’ils lui infligeaient, mais sans réellement lui faire de mal. Simultanément au lever de l’étoile du matin, un homme lui tirait une flèche en plein cœur alors qu’un autre lui assenait un coup de gourdin sur la nuque. La mort était instantanée. Son cœur était extrait comme sacrifice à l’étoile, puis tous les hommes de la tribu tiraient à leur tour une flèche dans le corps de l’infortunée.

Au début du XIXème siècle, un jeune guerrier Pawnee de bonne réputation s’est rebellé contre cette tradition. Au moment de porter le coup fatal, il a détaché la jeune fille et s’est enfui à cheval avec elle, pour la libérer en sécurité près de son village. A son retour, il n’a pas été puni ; il a été admiré pour son courage et sa force de détermination. Les membres de la tribu, apparemment soulagés de mettre fin à une pratique cruelle, n’ont plus jamais organisé de sacrifice.

La torture symbolique est une inspiration directe des coutumes du Sud-est, largement améliorée par l’absence de réelle souffrance physique. Le fait de traiter la victime comme sacrée, d’officier la cérémonie annuellement au lever d’une étoile, d’extraire le cœur et encore de nombreux autres détails reprennent fidèlement les coutumes aztèques – à l’exception du fait que chez les aztèques la victime aurait été un homme.

Les interactions entre les membres d’une même famille étaient dans la plupart des tribus largement codifiées. Avec certaines personnes, on pouvait rire et plaisanter, avec d’autres le respect se devait d’être absolu. La relation entre frères et sœurs, jugée très importante, faisait souvent l’objet d’une attention particulière. Les frères se sentaient responsables de leurs sœurs qui, en retour, rendaient de nombreux services à leurs frères, comme leur confectionner de beaux mocassins. Arrivés à l’âge adulte, une forme de relation de respect extrême se mettait en place, selon laquelle il leur devenait quasiment impossible de se parler. Mais cela n’impliquait aucune froideur, simplement la profondeur et la singularité de leurs sentiments l’un pour l’autre.

Les « sociétés » des Plaines, que l’on retrouve également chez les cultivateurs à l’ouest du Mississippi, sont très particulières. Certaines tribus offraient la possibilité à des femmes de créer leurs sociétés, mais la plupart du temps elles étaient réservées aux hommes. La Crow Tobacco Society, par exemple, n’existait que dans le but religieux de faire pousser le tabac sacré et de tenir des cérémonies destinées au bien-être de la tribu. Les Dog societies des Mandans et d’autres tribus se centraient sur des intérêts militaires, agrémentés de quelques considérations religieuses. Les membres de ces sociétés, parfois mentionnés en tant que « Dog soldiers », recherchait l’héroïsme guerrier, ils pouvaient également tenir le rôle de police au sein des tribus.

A leur âge d’or, les sociétés régentaient toutes les aspirations de la tribu. Les jeunes guerriers, désireux de trouver leur place et de gagner leur statut, s’adressaient aux membres plus âgés d’une société afin de tenter d’acheter insigne, chants, rituels et privilèges. Après de longues négociations, le jeune pouvait entrer dans la société et prendre la place d’un membre sortant, lui-même en demande d’une évolution de statut par son changement de société. Seuls les hommes les plus âgés se soustrayaient à la mécanique des sociétés, une fois leurs parcours de vie accomplis.

Les possessions immatérielles, comme l’appartenance à une société, étaient de loin les plus fondamentales. La générosité concernant les biens physiques se pratiquait naturellement puisqu’elle rendait honneur au donneur. Des chefs de tribus, en distribuant leurs biens, se réduisaient souvent à la pauvreté selon nos standards, mais pas selon les leurs. Les chants puissants, les paquets sacrés, les modèles de rites constituaient leur conception de la richesse. Lorsque son propre père où sa propre mère détenait la connaissance et les objets nécessaires pour officier un rite, il restait indispensable de les compenser, par des chevaux, des vêtements ou autres, pour les convaincre de transmettre cet héritage.

Les visions

La religion, comme pour les cultivateurs de l’ouest, comportait une forte dimension shamanique, avec de nombreux rituels, grands et petits, nécessitant un entraînement particulier. Les visions étaient importantes, non seulement pour les indiens de la vallée du Mississippi, mais aussi pour les Iroquois et de nombreuses autres tribus. Les indiens des Plaines et leurs voisins de l’est ont raffiné l’art de la vision. Les pouvoirs magico-religieux et les pouvoirs de guérison ou encore l’autorité pour créer un paquet sacré venaient des visions. L’organisation d’un raid pouvait trouver toute sa justification dans une vision. Les femmes pouvaient également avoir des visions mais de manière moins attendue et ritualisée.

Un homme pouvait difficilement mener sa vie à bien sans l’intervention de visions. Vers la fin de l’adolescence, les jeunes hommes partaient à la recherche de leur visions, jeûnant seuls dans la forêt, allant jusqu’à se mutiler – souvent en se coupant une extrémité de doigt – pour s’offrir en sacrifice et attirer la sympathie de esprits. Après avoir entendu tant de descriptions de visions, d’histoires et de mythes sur le comportement des esprits, la faim, la douleur, la solitude et l’intense attente permettaient généralement à chacun d’obtenir une vision acceptable par les normes de la tribu.

L’esprit fournissait quelques prières et désignait quels objets placer dans le paquet sacré pour obtenir sa protection et assurer une bonne vie. Une vision de forte intensité ou une série de visions pouvait inciter un homme à se dédier plus particulièrement à la religion et à créer un nouveau rite. Un homme incapable d’obtenir la bénédiction d’une vision pouvait acheter l’utilisation de celle de quelqu’un plus chanceux et ainsi obtenir le droit de copier ses prières et son paquet sacré.

Il existe une cérémonie populaire au cours de laquelle les hommes et les femmes dansent en cercle autour d’un arbre, en rythme avec des chants sur des thèmes d’animaux. La coutume de faire danser les hommes et les femmes ensemble vient probablement des peuples Basins, qui ont influencé à la fois le Sud-ouest et les Plaines. Il semble qu’ils soient également à l’origine de la peur des morts, qui rend nécessaire de brûler la maison d’un homme décédé, de ne plus dire son nom et de tout faire pour empêcher son fantôme de revenir vivre auprès de ses amis et de sa famille. Cette forme de peur est particulièrement puissante chez les Navajos et les Apaches.

Tous les Pueblos possédaient des cérémonies étudiées et formelles basées sur un large corpus de mythes sacrés. La majorité de leurs danses sont des prières mises en scène selon un arrangement très strict. Chaque pas, chaque geste est soigneusement répété ; le but n’est pas de briller individuellement mais d’être en harmonie totale avec le groupe. La musique se compose de voix, accompagnées de tambours avec de nombreuses et complexes variations de rythmes qui s’entrecroisent. La qualité du spectacle ainsi produit attire aujourd’hui de nombreux spectateurs et artistes lors de l’organisation de festivals.

Les visions, par leur caractère unique et inspiré de la psyché de chacun, ont institué un mode de religion laissant une grande place à l’individualité. Les rituels pouvaient être tenus seuls, en famille ou en société.

De plus, les rituels publics destinés à toute la tribu étaient associés à des célébrations plus légères et divertissantes. Les danses de guerre et les danses du scalp ou les cérémonies pour attirer le bison réunissaient toute la tribu. Un des rituels majeurs observé par toutes les tribus des Plaines est appelé la Danse du Soleil, bien que sans rapport direct avec la célébration du soleil. Pour certaines tribus, la danse intervient chaque année à date fixe ; pour d’autres, comme pour les Crows, elle n’est célébrée que rarement. Elle était généralement tenue et financée par une ou quelques personnes en remerciement d’une aide surnaturelle. C’était un moyen d’obtenir de puissantes vision et de rassembler toute la tribu.

Le cœur de la cérémonie se tenait dans un espace fermé, autour d’un arbre abattu rituellement faisant office de pilier central ; la danse était grave et sobre, comme dans la plupart des rituels des indiens des Plaines. Les danseurs, qui ne buvaient ni mangeaient de toute la durée de la cérémonie, entraient fréquemment en transe. Dans certaines tribus, dont les Sioux, ils démontraient leur courage et leur dévouement par des épreuves de douleur. Un bâton était placé sous la peau, entre deux incisions pratiquées pour le faire entrer et relié par chacune de ses extrémités au pilier central. Le danseur continuait de tirer jusqu’à ce que la peau cède et libère le bâton. D’autres tribus pratiquant assidument la Danse du Soleil, comme les Kiowas, n’ont jamais mis ces jeux de torture en place.

Cette cérémonie est devenue le rituel principal pour les Utes, un peuple des montagnes fortement influencé par la culture des plaines. Ils l’ont reprise et y ont ajouté quelques particularités, comme la danse en ligne et face à face des hommes et des femmes.

Soi-disant dans le but d’empêcher la pratique des automutilations, la Danse du soleil a été interdite aux États-Unis par le Bureau des Affaires Indiennes en 1910. A l’époque, au mépris de la Constitution, le Bureau s’est appliqué à faire disparaître toute forme de religion amérindienne. La Danse du Soleil a donc été interdite, sans distinction, pour la totalité des tribus. Le droit à la liberté religieuse pour les peuples indiens a finalement été reconnu en 1934.

Les indiens qui ont conservé une partie de leur organisation tribale et de leur coutumes traditionnelles se trouvent dans les groupes répertoriés au niveau fédéral. Les grands centres de population indienne se trouvent en Oklahoma, avec 110 000 personnes, en Arizona, avec 75 000 personnes et au Nouveau Mexique, avec 50 000 personnes. Les tribus d’Arizona et du Nouveau Mexique en sont originaires, mais la majorité des indiens d’Oklahoma y ont été déplacés lors de la politique de concentration des tribus dans un « Territoire indien » sur des terres pensées sans valeur. Depuis, l’or noir a été découvert et a changé la vision de la situation.

Dans le nord, 6 000 Iroquois se trouvent dans l’État de New York, les régions aux alentours du Dakota rassemblent 20 000 Sioux.

Jusqu’aux années 1870, le gouvernement américain considérait les tribus comme de petites nations dont la souveraineté était subordonnée à celle des États-Unis. Les accords se faisaient donc sous forme de traités, remis en cause dès que le gouvernement fédéral en voyant la nécessité. Finalement, le Congrès a interdit la ratification de traités et les indiens sont donc passés sous la juridiction commune, bien qu’ils ne soient généralement pas reconnus comme des citoyens. Quoique relatif, ce fut un léger progrès dans l’égalité des droits.

Aujourd’hui, le réserves indiennes sont protégées et les autorités fédérales se doivent de respecter les droits des indiens sur leurs terres, un respect renforcé par les capacités nouvelles des amérindiens à faire valoir leurs droits en justice, les cours fédérales leur étant les plus favorable.

Le partage de la juridiction entre les autorités fédérales et les autorités tribales sur les terres indiennes remonte aux origines de l’histoire juridique des États-Unis. La Cour Suprême a toujours maintenu ce principe. Cependant, ce résultat de l’histoire peut à tout moment être révoqué par le Congrès, ce qui inquiète fortement les communautés de «Native Americans ».

Pourquoi leur accorder ce traitement spécial ? Pourquoi s’embarrasser de complications juridiques ? Ne pouvons-nous pas être tous égaux dans un même état, sous les mêmes lois ? Les dures réalités persistent aujourd’hui. Bien sûr les exemples positifs existent, malheureusement le racisme est toujours présent et d’autant plus intense pour les populations qui vivent à proximité des réserves.

Les réformes, principalement en faveur de l’éducation et dans le simple but du respect de la dignité humaine, ont commencé sous Hoover (1929-1933) et se sont accélérées sous Roosevelt (1933-1945). En 1934, le Indian Reorganization Act, passé par le Congrès, permet aux indiens de contrôler leur propre gouvernement local, de créer des entreprises et d’acheter des terrains.

Le Indian Recognition Act, qui garantit l’indépendance sur bien des domaines aux First Nations, est régulièrement attaqué, mais semble tenir dans la durée.

Un travail de redéfinition des termes a aussi été entrepris. « First Nations » ou « Native Americans » sont d’utilisation relativement récente mais permettent à des peuples qui ont subi la colonisation au dernier degré de se réapproprier leur histoire et leur identité.

La plupart des amérindiens sont chrétiens. La plus grande communauté non-chrétienne se trouve au sud-ouest, bien qu’il y en ait d’autres, chez les Iroquois notamment. Beaucoup de tribus perpétuent leurs danses et autres activités traditionnelles car sont porteuses de sens et d’héritage, mais aussi car elles permettent de se réunir et de se divertir. En territoire Sioux, il est encore possible de trouver une fête avec des chants traditionnels à l’extérieur et les derniers tubes musicaux à l’intérieur, avec des gens faisant l’aller-retour entre les deux. Enfin, d’autres tribus mettent en scène leurs chants et danses traditionnels et profitent de leur rentabilité au niveau touristique autant que de l’opportunité de se retrouver dans une joie festive.

Lola CAUL-FUTY FRÉMEAUX

© FRÉMEAUX & ASSOCIÉS 2014

AMERICAN FIRST NATIONS AUTHENTIC RECORDINGS

1960-1961

By Lola Caul-Futy Frémeaux

The New World was settled slowly, by driblets of people crossing from Siberia into Alaska from time to time over a period of fifteen thousand years or more. Here and there, mostly in the Southwest of the United States, archaeologists have found traces of the early comers. They have found flint, bone and wooden tools, traces of their campfires, and bones of the animals they hunted.

The people who came over from Siberia were primitive. The Tip of Siberia is an end place, one of those regions occupied by tribes too weak to force their way into more favored lands. If a discovery was made in the central part of the Old World, in China, India, Asia Minor, or around the Mediterranean, the news of it spread all through in a thousand years or less. So the knowledge spread of how to plant grain, how to make bread and beer, and how to work metal. The news of such discoveries was very slow in reaching such a place as Siberia, or never got there at all. Deserts, vast distances, mountain ranges, cut the people off.

Most of the people who were to become Indians crossed over into the New World before any of the inventions or discoveries that changed the story of the Old World had been made. Some came over even before men had domesticated the dog. The latest finds, tested by what is called the radio-carbon method, which tells the age of charcoal by measuring its remaining radioactivity, indicate that men of Indian type had reached New Mexico 20,000 years ago, long before mankind anywhere had emerged from the Old Stone Age. They were Stone Age people. They had no pottery, probably no basketry. The earlier one had no bows or arrows; they hunted with spears and darts or javelins. As they moved south, they came into lands where the hunting was rich indeed. With their simple weapons they killed huge creatures, a giant sloth as big as a bear, elephants, mammoths, and a giant species of bison much larger than the bison of today.

The immigrants were not all alike. Some were tall, some short; some had long heads, some had round heads. Some modern American Indians are much darker than others, so we know their ancestors must have varied in colors also. As we should expect of people coming out of the Far East, a Mongoloid heritage was common among them. Mongoloid features are what unite today’s Indian racially. On the whole, they have very slight beards, their hair is black and straight, their eyes longish and often slightly slanted. Their cheekbones are high and their faces usually rather broad. Their typical skin color is a yellowish ivory which tans to a strong brown.

The fact that in the course of fifteen thousand years many different people came into the New World is shown also by the Indian languages. Modern Indians speak languages of many different families. These families are no more like each other than English, Tibetan and Zulu. People often ask white men who live among Indians, “Do you speak Indian?” It is a foolish question, like asking “Do you speak European?”

North and South America were populated. Back in the heart of the Old World, many discoveries were made, but these never reached across to the New. The early Americans had to make their own discoveries. They were up against some real handicaps. There were few animals that could be tamed (ask any cowboy who has tried to herd buffaloes!). The only large ones were the llamas of Peru, big enough to carry light packs but too small to pull wagons across mountain country. The Old World had horses, cattle, tamable elephants in Asia, camels, sheep, goats, and pigs, as well as chickens, ducks, and geese. The Indians learned to tame and raise turkeys, but birds cannot be used to do work. Like the elephants in Africa, the big animals could not be tamed.

So also, in the Old World there were many kinds of grain that could be planted by scattering the seeds in fertile ground, such as wheat, rye, oats, barley, and millet. In the New World, there was only one, “maize”, which most of us call “corn”. Anyone who has ever planted it knows that you can’t sow it broadcast; you have to set each grain in a hole. It took a lot of experimenting and centuries of time to develop the original, wild grass into a plant that would yield a decent crop. In fact, there is reason to believe that maize is the result of a cross between two wild plants, neither of which yielded very much. All in all, we can see that the people who developed our American corn were intelligent, and overcame many obstacles.

The Americas began to repeat the history of the Old World. Centers of real civilization grew up in the middle part. The creators or elaborators of civilization whose names are best known to us are the Incas, the Toltecs, and the Mayas. There were cities, handsome architectures, fine arts, forms of writing, mathematics, and astronomy. These civilizations still used stone tools, although they were nothing like what we think of when we say “stone age”. They were on the edge of the change to metals. They worked gold, silver, and copper, but as yet mostly for ornaments.

In the Old World, time and again the barbarians attacked the centers of civilization, conquered them, became civilized themselves and carried on the line of progress. The same thing happened in the Americas. Notably, barbarous people speaking a language of the Uto-Aztecan family came down from the north to invade the cities of central Mexico. There they conquered the ancient Toltecs, acquired their civilization, and became the Aztecs.

The influence of the civilized centers constantly spread outward, as it did on the Old World. The influence came into what is now the United States through two principal entrance areas, the Southeast and the Southwest.

By the “Southwest”, students of Indian history mean Arizona and New Mexico and narrowish strips of the neighboring territories on all sides, especially a strip of northern Mexico and of southern Colorado and Utah. A thousand miles of harsh desert and mountain country lay between this area and the cities to the south, but trade went on across it, not directly between the Southwesterners and the central Mexicans, but indirectly. Goods passed each way from tribe to tribe in a long series of exchanges. The civilized people got turquoise from the north; the northerners received, among other things, parrot feathers and seeds. Equally important, ideas were passed on along with the goods – the idea of farming, of weaving, of making pottery, of putting on masks so as to represent sacred beings.

We know a good deal more about the very early history of the Southwest than we do about other parts of the country, for two reasons. Even two thousand years ago, the Southwest was fairly dry, although not as arid as it is now. In dry country, the remains that people leave behind them last much longer in the ground, and in dry country, where vegetation is sparse, it is easy for the archeologists to spot the right places to dig in. Also, many of the tribes living in the Southwest today are the direct descendants of those that were there more than a thousand years ago. Oraibi, a Hopi village, has been continuously inhabited since 1100 A.D. The modern Indians retain their languages and a great deal of ways of their ancestors, as well as many traditions about them.

Wherever conditions allowed in the Southwest, the people went in heavily for farming, beginning with native beans and corn from the south. Many of them learned to irrigate, others became expert dry farmers. They made fine basketry, raised and wove cotton, and made truly beautiful pottery. They made fine jewelry of turquoise and shell and carved small objects of various local stones.

There was a good deal of difference between the cultures of various of the Southwestern farmers, such as the Pueblo, the Hohokam, the Mimbres, and the Mogollon. The most famous are the Pueblo people, not only because of their spectacular ruins, but because their culture is so well continued by the modern Hopi and Pueblo Indians. The main line of the Pueblos started along the Colorado and Utah border, then later moved southward. They built villages of stone houses cemented with adobe, a local clay. In each village were one or more kivas, which were men’s clubs and also centers of religious ceremonial. Kivas were built entirely or partly underground and were entered through a hole in the roof. Their basic form derived from an early type of “pit house”, built before the Southwesterners had learned to be masons, but later they were elaborated beyond any resemblance to those early structures. In late times, some of them were decorated with stylized but handsome murals of ritual subjects.

In the Southwest there are few hills; instead there are mesas. These are hills with perpendicular sides of rock and flat tops. Big sections of these sides scale off, leaving deep ledges overhung by the upper parts of the cliffs. In early times, 2,000 years ago, the Southwestern Indians often built their houses on these ledges for shelter from the weather. Later, they built their towns in them, although often that meant that the women had to climb up and down the steep cliffs every day to carry water and all the crops and other food had to be dragged or carried up. Towns placed on such ledges are known as “cliff dwellings”. They are picturesque, but they must have been mighty inconvenient.

The reason for moving into such places was probably that, between 1,000 and 1,200 A.D., savage tribes began drifting into the Southwest. Among these were the ancestors of the Navahos and Apaches, who later became so famous. These people, who had broken off from tribes settled in northern Canada and Alaska, were primitive and poor, but they had an Arctic-type bow, originally of Asiatic origin, that was stronger that any bow known in the Southwest. This gave them a military advantage. The newcomers did not make regular war upon the Pueblo people. They traded with them, they learned from them, they stole them, and from time to time they raided them. They were enough of a nuisance to make the Pueblos want to have their settlements strong and defensible.

Later, when they moved out of the section in which their culture first developed, they built their towns on high places, or arranged so that the houses themselves made a defensive wall.

The Southwestern culture was essentially peaceful and democratic. Few indications of fighting have been found, for all the trouble the semi-civilized people may have had with the nomadic, primitive bands that had seeped into the country. We do not find the elaborate, special burials of a few individuals that occur where there is much distinction of rank, nor are there special houses finer than others. The modern Pueblo Indians, too, are peaceful and democratic. The labor they put into building their kivas is a community effort, undertaken voluntarily.

In ancient times, they were governed by a theocracy, that is, by their priests and religious officials, but the governors’ powers derived from the consent of the governed. Their lives centered around their religion. When the Spaniards first came among them, they were greatly impressed by their houses, their farms, and their arts. They were also impressed by their magnificent ceremonies.

The Southwestern culture never spread far beyond Arizona, New Mexico, and the southernmost parts of Colorado and Utah. Beyond, in most directions, were high mountains or deserts which could not be farmed with primitive equipment. When your best tools are a pointed stick and a hoe made by tying a deer’s shoulder-blade to a handle, you cannot irrigate the Great American Desert. To the eastward lay the High Plains, which were also unsuitable to primitive farming. As we are learning now the hard way, they are not suited to modern farming either.

The other area where the influence of the growing American civilization reached, the Southeast, was utterly different. Because Columbus thought that the islands he discovered were part of India, we call all the aboriginal settlers of the Americas “Indians”. Because we give them all the same name, we think they were all alike. As a matter of fact, the people of the Southwest and of the Southeast were about as different as the Englishmen are from Arabs.

We do not as yet know the Southeastern story in as great detail as we do the Southwestern, nor can we carry it as far back. What we do know is that a thousand years ago a remarkable culture had spread from the Gulf Coast up the Mississippi Valley almost to the Great Lakes. It, too, was a culture based on farming. We call it the “Mound Builder” culture because the people went in for building mounds in a large way.

Direct Mexican influences can clearly be seen in this culture. Trait after trait, from weaving feather cloaks to a highly organized aristocracy, comes from the civilized great cities. One of the most striking evidences of the influence is in the very matter of mounds.

The Toltecs, Aztecs, and Mayas built flat-topped pyramids on which they placed their temples and sometimes their palaces. They built with stone, mortar, and a form of concrete. Pyramids and buildings were arranged in impressive groups that served as religious and civic centers for the humble farmers who lived roundabout. The people along the Mississippi Valley built similar centers in a cruder style. The mounds were made of rubble covered with earth. The temples and other buildings were made of wood and thatch. Nonetheless, the form is the same.

In the north, the people developed a mound pattern of their own, building what are called “effigy mounds”. These are figures of birds and animals, made of raised earth, often themselves placed on top of ordinary mounds.

The people lived in fairly permanent villages or towns, their houses usually made with pole or wattled walls and thatched roofs, or covered with mats. They were extensive farmers. Nowhere in the United States did people rely solely on farming. The whole population of the country before the white men came was not over a million souls. There was plenty of room, and the hunting and fishing were wonderful. Naturally, farming was balanced by the pursuit of fish and game. The Mound Builders developed the finest art, especially in their modeling and carving, that ever existed among the North American Indians.

The Mississippi Valley, with its relatively civilized settlements and its rich booty, was very tempting to the more primitive, hardy tribes that surrounded it. It was bound to be invaded, and it seems to have been almost completely overrun a few centuries before the white men came there.

There was one nation, the Natchez, surviving in historic times, that may well have descended directly from the older people. Its center was near the great Emerald Mound in Mississippi. Alone among all the historic North American Indian tribes and nations, it had an absolute monarch. The king, called “The Sun”, was so sacred that he could not defile himself by setting his foot to the ground, so he was carried about on a litter. He wore a feather crown and elaborate feather cloak. Volunteers became his servants, and of their own accord had themselves killed when The Sun died, so that they might accompany him in the after life. He had absolute power over all his people.

The Natchez were divided into two halves, the aristocracy and the common people. The aristocracy was subdivided into three classes, Suns, or royalty, Nobles, and Honorables. The common people were all lumped together in a single group and called Stinkers.

The catch to this was that the common people could marry as they pleased, but the aristocrats were forbidden to marry within their own half. Therefore, all of them had to marry Stinkers. When a male aristocrat married a common woman, his children were rated one level lower than himself, so the children of a male Honorable became ordinary Stinkers. When an aristocrat woman married a Stinker man, her children inherited her rank. Thus even The Sun himself was half Stinker on his father’s side.

Much too often, the singularity of each Native American people is forgotten. The interactions between cultures, very different from one another, were leading to discoveries and were in the process of building great civilizations when white men landed with horses, steel and gunpowder and destroyed with savage strength entire nations.

Sacred bundles

Partly through the visions of inspired individuals, partly by ways now lost in the mist of antiquity, among these tribes there sprang up a collection of sacred objects, such as the sacred arrows or the Cheyennes, or more often, what are called “medicine bundles”. Both names are poor. So many Indian things were named by white men by ignorance, contempt, or both. They saw that Indians combined healing with religion – as we did until not so long ago – so they called the Indian religious practitioners “medicine men” regardless. They saw that the Indians wrapped objects they considered sacred in various kinds of packages, often beautifully decorated. When white men were allowed to see what those objects were, they did not think much of them, any more than an Indian would think much of our sacred symbols. They saw that these packages, or their contents, were sometimes used to heal the sick, just as, in the 1500’s, Cabeza de Vaca treated sick Indians by touching them with a cross, so they called them “medicine bundles”. This is much as if Indians seeing Christians pray for health, were to call our cross “medicine stick”, and about as accurate.

The best name we have for those packages is “sacred bundle”, and it will have to do. Many were personal property, handed from father to son, or buried with the owner. Others became clan or tribal property. They were the centers of major rituals. Among the Algonquians, other than the Cheyennes, bundles were usually clan property, so that the great ceremonies related to farming were performed by clans. The owner of the bundle was instructed by the man from whom he inherited it in the prayers and rites that went with it. He alone could lead them; thus he was a priest.

The northern tribes, both east and west of the Mississippi, gave reverence to the calumet, or sacred pipe. Pipes were carried in special dances, they served as passports for messengers, and were used in many rituals. A pipe dressed with red feathers signified war; one with white feathers meant peace.

The bowl of a true calumet was made from a stone, catlinite, found Minnesota, in the country of the non-farming Sioux. This stone is soft and easy to work when first dug out of the ground, then it hardens. The bowls were fitted with long stems which were decorated with great elaboration. Some pipes could be smoked for pleasure, in which case they did not used the tobacco raised with special rituals. Others were smoked only on ceremonial occasions. Many tribes permitted smoking only by persons who had attained some rank.

In the Southeast, war achievement was the common man’s road to fame and rank. With them it was a murderous business of killing everyone possible and bringing back gory samples as evidence, with the alternative of bringing a strong man to torture. Among the Western farmers, except in the Southern part were Southern influence was strongest, torture was not a requirement. The main thing was for a man to prove his courage, and these tribes came to the logical conclusion that the greatest courage a ma could show was to lay his bare hands upon an armed enemy, preferably one who was surrounded by his comrades. Killing from ambush was not honored; killing of any kind, in fact, was secondary to bravery, except in those rare occasions when two tribes found it necessary to engage in serious war with each other.

Scalps were taken as a regular thing, but they were not essential, and a man was not judged by the number of his scalps. Before going on a war party, to get into the spirit of the thing and acquire power, or after it, to celebrate a victory, the men danced. The dance after a

successful raid is generally called a “scalp dance”, since any scalps taken were featured. In these dances, each warrior dramatized in stylized form what he would do or had done, bending low to track the enemy, leaping to the attack, going through the motions of combat. The footwork was light and fast, in time to fast, cheerful songs almost always pretty and sometimes beautiful, and to the rapid beat of a high-toed drum. It was a fine mean of showing off. Similar dances were performed for pure fun. As each individual danced as he pleased, no rehearsal was necessary; one needed only to know how to dance, and know the tune. It is from these performances that the “war dances” evolved to what is now part of the common, commercial stock of Indians all over the United States.

Boasting was an important part of the war complex. On appropriate occasions, warrior stood up to the public in turn to recite their brave deeds. The performance was far from modest, but it had to be accurate; everyone kept careful track and knew just what any man had a right to claim. If he claimed any act that was not his due, he would be hooted down and disgraced. White frontiersmen were quick to adopt this trait. They mixed it with whiskey and imagination, to produce the famous “brags” of the early frontier.

Fighting was a good deal of a sporting proposition, carried on by individual initiative. Hunting was a more serious business. Hunting parties were often carefully organized, and under many circumstances hunter were not allowed to go out without the permission of the chiefs, in order that no hasty individual might frighten the game. This control was especially tight in regard with the buffalo hunts.

The tepee was probably invented in the Arctic to keep out cold, but it is also a good tent in hot weather, while our tents, under direct sun, become intolerable.

The farming tribes used their tepees mostly when they went out after the buffalo, which usually was an annual affair, when the great herds, in their migration, came nearest to their territories. The buffalo hunt was a difficult business. A man on foot, armed with a stone-tipped lance and stone-tipped arrows, ran real danger when he went to kill one of these big, aggressive, thick-hided beasts – the more so since they were almost always in herds, the bulls quick to attack in defense of their females and young.

Much of their hunting was done by stampeding the animals; for instance, by setting fire to the grass and driving them either over a cliff or past a line of archers who picked off as many as they could. Their kill was limited by what they could use plus what they could dry, or “jerk”, and carry back for later use; and the amount they could carry back was what the women could take on their backs, including the hides, or what could be added – not much – to the burdens already dragged by the dogs. They had no wheels, no wagons. They made a contraption known as a travois. Two tepee poles were tied to the shoulders of a dog, the free ends dragging on the ground, and across these the load was placed. In winter, the northern tribes had toboggans, on which much more could be hauled, but in winter the buffalo were in the south.

Throughout the area we find the signs of relationship with the Southeast. Most tribes had clans, some of which counted descent through the mother, some through the father. Many were divided into halves and moieties, like the Iroquois, the Creeks, and the Natchez; some grouped their clans into several larger groups instead of only two. The common thing, as usual, was to regard all the members of the clan, even though they came from different villages and were total strangers to each other, as relatives, who helped each other and, as relatives, could not marry. Such clans are called “exogamous”, meaning “outward marrying”. Some were “endogamous”, that is, although all fellow clansmen felt bound to one another, they also married within the clan.

Chieftainships were well defined. Among some tribes, chiefs were appointed for life, among some they were partly hereditary. Many tribes, especially in the northeastern group, had both war and peace chiefs, the peace chiefs being the real governors, the war chiefs leaders of war parties. When Tecumseh formed the great Algonquian alliance against the United States, he stressed the fact that “the chiefs”, meaning the peaceful governors, were no longer in charge.

Young men went in search of visions, usually going off by themselves and praying for a supernatural visitor. The vision a man might receive was an indication of the extent to which he had what the Iroquois called orenda, special strength from the all-pervading, unseeable god the Algonkians called by names related to Manitou the Siouans by names similar to Wakonda. Very strong visions led a man to become a shaman, in which case he read the future, gave news of people at a distance, and diagnosed sicknesses but often left their treatment to specialists in actual medicine. The medical treatment ranged from setting bones and administering healing herbs to such tricks as sucking stones, thorns, and small animals out of the patient’s body.

These shamans did spectacular tricks. There were large-scale ceremonies also, that could be conducted only by men with something on the line of priestly training. Among many tribes the shamans, who received this training, were on the way to being priests; among others there were true priests. The Pawnee shamans trained their disciples after the manner of priests. There was also a true priesthood that was strictly hereditary; among these, five, of whom the highest was associated with the evening star, were in fact more powerful than the chiefs. The Pawees had a definite sun worship and related star cult, including an annual Morning Star Ceremony. At this ceremony, a captured maiden was sacrificed. The captive might have been taken at any time of the year. She was well treated, and told nothing of her fate. Three days before the great day, she was stripped of her clothing, painted all over, and treated as a sacred person. Every attempt was made to keep her from divining what was coming.

Before the morning star rose on the fourth morning, she was led to a raised scaffold. It was considered a lucky sign if, in her innocence, the girl mounted the scaffold without resistance. Then she was tied. Priests symbolized torture of her, but did not actually hurt her. Then a man shot her through the body from the front, just as the morning star rose, and at the same moment another man struck her over the head with a club. Death was instantaneous. Her heart was cut out as a sacrifice to the star, and every male in the tribe shot an arrow into her body, older relatives doing it in the name of boys too young to draw a bow themselves.

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, a young Pawnee warrior of high reputation rebelled against this rite. At the critical moment he cut the girl free from the scaffold, threw her on his horse, and ran off with her. He set her free near her own tribe. When he returned, he was not punished, but admired for his courage. The people seem to have been relieved to drop a cruel practice, and it ended there.

The symbolized torture clearly derives from the Southeast, with great improvement. Treating the victim as holy, holding the rite when a certain star appears at a certain time of year, cutting out the heart, and many other details, seem pure Aztec – except that then Aztecs would have sacrificed a man. Certainly the Pawnees show up as a lot more likeable than many of the tribes further east.