- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

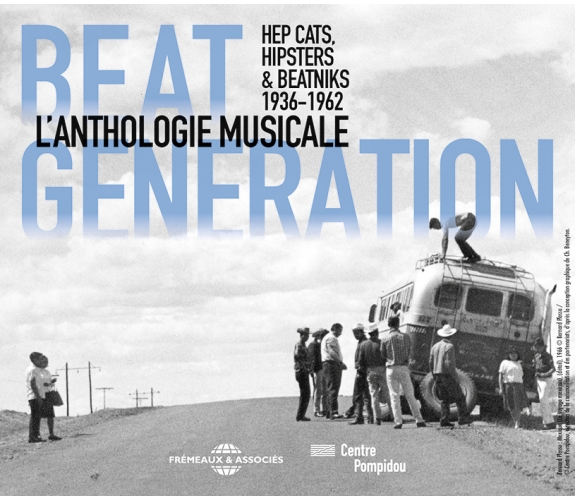

HEP CATS, HIPSTERS & BEATNIKS 1936-1962 - EXPOSITION AU CENTRE POMPIDOU DU 22 JUIN AU 3 OCTOBRE 2016

Expo Centre Pompidou

Ref.: FA5644

Artistic Direction : BRUNO BLUM

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Total duration of the pack : 3 hours 39 minutes

Nbre. CD : 3

HEP CATS, HIPSTERS & BEATNIKS 1936-1962 - EXPOSITION AU CENTRE POMPIDOU DU 22 JUIN AU 3 OCTOBRE 2016

HEP CATS, HIPSTERS & BEATNIKS 1936-1962 - EXPOSITION AU CENTRE POMPIDOU DU 22 JUIN AU 3 OCTOBRE 2016

This literary movement built itself around underground jazz culture, which expressed liberation of body and soul. Inspired by jazzmen and hep cats, the Beat Generation hipsters rejected traditional values, embraced African-American musics, travelling, drugs, a free sex lifestyle as well as spirituality. Allen Ginsberg, William Burroughs and On the Road author Jack Kerouac launched the radical American counterculture that thrived in the 1960s and 1970s, leaving a tremendous mark on lifestyles, and on the world of arts and opinions — hippies and punks alike. In partnership with the Centre Pompidou on the occasion of the “Beat Generation” exhibition in Paris, the story of the Beat Generation is told by Bruno Blum in a 32-page booklet. PATRICK FRÉMEAUX

RACE RECORDS

PUNK ROCK (THE ROOTS OF) 1926-1962

LES RACINES DES MUSIQUES NOIRES. EXPOSITION À LA CITÉ...

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1You'se A ViperStuff Smith and his Onyx Club BoysS. Smith00:03:161936

-

2A Sailboat In The MoonlightBillie Holiday and her OrchestraC. Lombardo00:02:501937

-

3Swing Is HereGene Krupa's Swing Band00:02:561936

-

4Heckler's HopRoy Eldridge and his Orchestra00:02:381937

-

5Killin' JiveThe Cats And The Fiddle00:02:541939

-

6(Hep Hep) The Jumpin' JiveCab Calloway And His OrchestraCab Calloway00:02:511939

-

7Your Red WagonCount Basie QuartetDon Raye00:02:561939

-

8Swing To BopCharlie ChristianEddie Durham00:03:271941

-

9How High Am ILouis Jordan And His Tympany FiveLouis Jordan00:02:561944

-

10Be-Baba-LebaHelen Humes with Bill Dodgett OctetHelen Humes00:02:461944

-

11(Get Your Kicks On) Route 66Nat King ColeBobby Troup00:03:031946

-

12Slim's JamSlim Gaillard And His OrchestraS. Gaillard00:03:191945

-

13Popity PopSlim Gaillard And His OrchestraS. Gaillard00:02:591945

-

14Groovin' HighDizzy Gilespie Sextet00:02:451945

-

15Song Of The VagabondsArt TatumHooker00:02:181945

-

16Dexter's Minor MadDexter GordonDexter Gordon00:02:431945

-

17Crazy WorldJulia Lee And Her Boy FriendsR. Burns00:03:011947

-

18Lop PowBabs Gonzales - Bab'sThree Bips And A BopGonzales00:02:421947

-

19Scrapple From The AppleCharlie Parker QuintetCharlie Parker00:02:581947

-

20MantecaDizzy Gillespie And His OrchestraDizzy Gillespie00:03:091947

-

21Tanga (Part 1)Machito And His Afro Cuban OrchestraMario Bauza00:03:571948

-

22Rock And RollWild Bill MooreWild Bill Moore00:02:531948

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Gator TailCootie Williams And His OrchestraJackson00:02:491949

-

2Tempus Fugue-ItBud PowellBud Powell00:02:281949

-

3Four And One MooreStan Getz Four Brothers Bop Tenor Sax StarsGerry Mulligan00:03:471949

-

4Sound LeeLee Konitz QuintetLee Konitz00:04:081949

-

5BoplicityMiles Davis00:03:011949

-

6Soft ShoeGerry Mulligan QuartetMulligan Gerry00:02:401952

-

7Little Rootie TootieThelonious Monk Trio00:03:071952

-

8The NazzLord BuckleyLord Buckley00:11:481951

-

9I Fall In Love Too EasilyChet Baker QuartetJ. Styne00:03:211951

-

10The Rocket Ship ShowJocko HendersonJocko Henderson00:00:351953

-

11Shulie A BopSarah Vaughan And Her TrioGeorge Treadwell00:02:411953

-

12Bones For ZootZoot Sims Quartet00:04:241954

-

13(Get Your Kicks On) Route 66Bobby TroupBobby Troup00:02:271955

-

14Zajj's DreamDuke Ellington And His OrchestraD. Ellington00:03:061956

-

15Say ManBo DiddleyBo Diddley00:03:001958

-

16American HaikusJack KerouacKerouac Jack00:09:581958

-

17Dat DereOscar Brown JrOscar Brown Jr00:02:551960

-

18KaddishAllen GinsbergGinsberg Allen00:11:031959

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1The Beat GenerationBob McFadden And DoorRodney McKuen00:02:061958

-

2High School DragPhilippa FallonPhilippa Fallon00:02:161958

-

3Winin BoyDave Van RonkJelly Roll Morton00:02:381959

-

4AireginLambert, Hendricks, RossLambert David Alden00:03:321959

-

5Kookie's Mad PadEdd ByrnesRalke00:02:061959

-

6Psychopathia SexualisLenny BruceLenny Bruce00:02:271958

-

7But I Was CoolOscar Brown JrOscar Brown Jr00:02:561960

-

8CoolDel Close & John BrentDel Close00:03:531961

-

9UncoolDel Close & John BrentDel Close00:01:011961

-

10Talkin' New YorkBob DylanRobert Zimmerman00:03:191961

-

11So WhatEddie JeffersonEddie Jefferson00:03:301961

-

12Scrapple From The AppleLes Double SixJeanine Perrin00:02:531962

-

13Readings From “On The Road” And “Visions Of Cody”Jack Kerouac & Steve AllenJack Kerouac00:03:311959

-

14Is There A Beat GenerationJack KerouacJack Kerouac00:12:351958

-

15The Last Hotel and Some Of DharmaJack Kerouac with Al Cohn and Zoot SomsJack Kerouac00:03:511958

-

16HowlAllen GinsbergAllen Ginsberg00:21:481959

-

17I Sing Of OlafRoger SteffensE.E. Cummings00:02:111962

Beat generation FA5644

L’anthologie musicale

Beat Generation

Hep Cats,

Hipsters & Beatniks

1936-1962

Ce mouvement littéraire s’est construit autour de la culture jazz souterraine, qui exprimait la libération des corps et des esprits. Inspirés par les jazzmen et autres hep cats, les hipsters de la Beat Generation ont rejeté les valeurs traditionnelles de la société, adoptant les musiques afro-américaines, les voyages, les drogues, une sexualité libre et la spiritualité. Allen Ginsberg, William Burroughs et Jack Kerouac l’auteur de Sur la route ont lancé la contreculture américaine radicale qui se développerait dans les années 1960 et 1970, marquant considérablement les mœurs et le monde des arts, des idées — des hippies aux punks. En partenariat avec le Centre Pompidou à l’occasion de l’exposition « Beat Generation », l’histoire de la Beat Generation est évoquée par Bruno Blum dans un livret de 32 pages.

Patrick FRÉMEAUX

This literary movement built itself around underground jazz culture, which expressed liberation of body and soul. Inspired by jazzmen and hep cats, the Beat Generation hipsters rejected traditional values, embraced African-American musics, travelling, drugs, a free sex lifestyle as well as spirituality. Allen Ginsberg, William Burroughs and On the Road author Jack Kerouac launched the radical American counterculture that thrived in the 1960s and 1970s, leaving a tremendous mark on lifestyles, and on the world of arts and opinions — hippies and punks alike. In partnership with the Centre Pompidou on the occasion of the “Beat Generation” exhibition in Paris, the story of the Beat Generation is told by Bruno Blum in a 32-page booklet.

Patrick FRÉMEAUX

DISC 1 - HEP CATS 1936-1948

1. YOU’SE A VIPER - Stuff Smith 3’14

2. A SAILBOAT IN THE MOONLIGHT - Billie Holiday 2’48

3. SWING IS HERE - Gene Krupa 2’55

4. HECKLER’S HOP - Roy Eldridge 2’37

5. KILLIN’ JIVE - The Cats and the Fiddle 2’52

6. (HEP HEP) THE JUMPIN’ JIVE - Cab Calloway 2’49

7. YOUR RED WAGON - Count Basie 2’54

8. SWING TO BOP [Topsy] - Charlie Christian 3’25

9. HOW HIGH AM I? - Louis Jordan 2’54

10. BE-BABA-LEBA - Helen Humes 2’44

11. ROUTE 66 - Nat ‘King’ Cole 3’02

12. SLIM’S JAM - Slim Gaillard 3’18

13. POPITY POP - Slim Gaillard 2’57

14. GROOVIN’ HIGH - Dizzy Gillespie 2’43

15. SONG OF THE VAGABONDS - Art Tatum 2’17

16. DEXTER’S MINOR MAD - Dexter Gordon 2’42

17. CRAZY WORLD - Julia Lee 2’59

18. LOP POW - Babs Gonzales 2’40

19. SCRAPPLE FROM THE APPLE - Charlie Parker 2’57

20. MANTECA - Dizzy Gillespie 3’07

21. TANGA - Machito 3’55

22. ROCK AND ROLL - Wild Bill Moore 2’53

DISC 2 - HIPSTERS 1949-1960

1. GATOR TAIL [Part 2] - Cootie Williams 2’47

2. TEMPUS FUGUE-IT - Bud Powell 2’26

3. FOUR AND ONE MOORE - Stan Getz 3’46

4. SOUND LEE - Lee Konitz Quintet 4’06

5. BOPLICITY - Miles Davis 3’00

6. SOFT SHOE - Gerry Mulligan Quartet 2‘38

7. LITTLE ROOTIE TOOTIE - Thelonious Monk 3’05

8. THE NAZZ - Lord Buckley 11’47

9. I FALL IN LOVE TOO EASILY - Chet Baker 3’20

10. THE ROCKET SHIP SHOW - Jocko Henderson 0’34

11. SHULIE A BOP - Sarah Vaughan 2’40

12. BONES FOR ZOOT - Zoot Sims Quartet 4’22

13. ROUTE 66 - Bobby Troup 2’25

14. ZAJJ’S DREAM - Duke Ellington 3’05

15. SAY MAN - Bo Diddley 2’58

16. AMERICAN HAIKUS - Jack Kerouac/Al Cohn 9’56

17. DAT DERE - Oscar Brown, Jr. 2’53

18. KADDISH - Allen Ginsberg 11’03

DISC 3 - BEATNIKS 1958-1962

1. THE BEAT GENERATION - Bob McFadden and Dor 2’04

2. HIGH SCHOOL DRAG - Phillipa Fallon 2’14

3. WININ’ BOY - Dave Van Ronk 2’36

4. AIREGIN - Lambert, Hendricks & Ross 3’30

5. KOOKIE’S MAD PAD - Edd Byrnes 2’04

6. PSYCHOPATHIA SEXUALIS - Lenny Bruce 2’25

7. BUT I WAS COOL - Oscar Brown, Jr. 2’54

8. COOL - Del Close & John Brent 3’51

9. UNCOOL - Del Close & John Brent 0’59

10. TALKIN’ NEW YORK - Bob Dylan 3’18

11. SO WHAT - Eddie Jefferson 3’28

12. SCRAPPLE FROM THE APPLE - [À bâtons rompus] - Les Double Six 2’51

13. READINGS FROM “ON THE ROAD” AND “VISIONS OF CODY” - Jack Kerouac/Steve Allen 3’29

14. IS THERE A BEAT GENERATION? - Jack Kerouac 12’33

15. THE LAST HOTEL & SOME OF DHARMA - Jack Kerouac 3’49

16. HOWL - Allen Ginsberg 21’47

17. I SING OF OLAF [e. e. cummings] - Roger Steffens 2’11

Beat Generation

Hep Cats, Hipsters and Beatniks 1936-1962

par Bruno Blum

Les folies sont les seules choses qu’on ne regrette jamais.

— Oscar Wilde

La « Beat Generation » est un mouvement littéraire américain lié au jazz et à sa culture souterraine, celle des hep cats (« connaisseurs ») afro-américains originels. De grands musiciens comme Cab Calloway, Lester Young, Roy Eldridge, Louis Jordan, Slim Gaillard, Charlie Parker ou Dizzy Gillespie étaient emblématiques de l’état d’esprit de ces hep cats, ensuite appelés les hepsters ou hipsters pendant la guerre1. En ces temps de ségrégation raciale des années 1940, leur musique et leur mode de vie libre fascinaient quelques Blancs ouverts d’esprit qui fréquentaient les dance halls et boîtes de jazz de New York. Adoptant des éléments de cette contreculture afro-américaine radicale, ils sont devenus à leur tour des « hipsters ». Ces Blancs ouverts à la culture des jazzmen y ont apporté leur contribution, notamment par le biais de poèmes et d’essais où le jazz et ses mystères étaient valorisés. De grands musiciens blancs, eux aussi des hipsters, comme Gene Krupa, Dodo Marmarosa, Gerry Mulligan ou Chet Baker (et incluant de nombreux Juifs, notamment les précurseurs Benny Goodman, Artie Shaw et Mezz Mezzrow, puis Buddy Rich, Doc Pomus, Stan Getz, Barney Kessel, Zoot Sims, Al Cohn, Lee Konitz…) jouaient avec des Noirs et ont participé à affirmer cette culture libertaire, qui récusait le racisme. Appelée la Beat Generation dès le début des années 1950, la tendance littéraire marginale imprégnée de cet univers allait devenir très influente à partir de la publication du livre On the Road de Jack Kerouac, qui fit sensation en septembre 1957. Kerouac y conte des voyages d’aventures avec une appro-che inédite, proche de l’autobiographie, utilisant un style de rédaction spontané, direct, que leur auteur rapprochait des improvisations du jazz. Dès sa sortie, les médias américains ont brusquement vulgarisé la subversive Beat Generation, à laquelle participaient des écrivains aussi différents que Ginsberg, Kerouac et Burroughs. Les stéréotypes du mode de vie beat ont alors été mis en avant et parfois moqués : les mœurs libres, le laisser-aller, l’insouciance, le pacifisme et la liberté de ton y tranchaient avec le puritanisme et le conformisme des années Eisenhower — où l’antisémitisme et le racisme étaient des constantes. Cette notoriété soudaine donna aussi un nouveau nom, pour ne pas dire une étiquette, aux jeunes marginaux urbains de l’époque : les beatniks. La culture des beatniks se propagera et se métamorphosera de 1957 aux années 1970, marquant fortement le monde des arts et des idées de cette période, donnant le ton des beatniks aux freaks, puis des hippies aux punks. La Beat Generation a profondément marqué la littérature, le cinéma avec avec L’Homme au bras d’or (Otto Preminger, 1955, avec Frank Sinatra), A Bucket of Blood (Roger Corman 1959) ou The Flower Thief (Ron Rice 1960) ; et la culture rock américaine, notamment dans son approche de la rédaction de paroles chez Bob Dylan, le Velvet Underground ou les Doors.

HEP CATS,

SWING & ROCK & ROLL

— Ben Hecht : J’ai remarqué une chose dans vos écrits et ceux de vos copains, et de Monsieur Ginsberg en particulier : c’est votre affinité avec les nègres, serait-ce que le nègre est un beat authentique, automatique, sans avoir à en porter le titre ?

— Jack Kerouac : Oui, il est le beat originel. Il est plein de joie. Ils s’amusent bien, vous avez remarqué que les nègres s’amusent bien. — Interview with Jack Kerouac, 1958

Dans son essai Le Nègre Blanc2, le double Prix Pulitzer Norman Mailer expliqua que la prise de conscience des atrocités commises pendant la guerre avait mené à une attitude nouvelle. En dépit du racisme ambiant, des hipsters blancs se sont ainsi familiarisés avec la culture des hep cats afro-américains. Face à l’ironie de leur existence d’opprimés, ces artistes noirs avaient forgé une attitude hédoniste particulière, qui attirait certains jeunes décomplexés. Le sens du mouvement beat tel qu’il a été exprimé par Kerouac et Ginsberg était une célébration de l’esprit du jazz et du blues : romantisme du mode de vie des musiciens, des artistes itinérants, nomades, bo-‑

hême, danse libre, sexualité libre, expression libre et spontanée… La culture des hep cats incluait la consommation d’alcool (Louis Jordan, How High Am I?, 1944) et fumer le reefer. Elle avait été popularisée avant-guerre par des vedettes comme l’excentrique Cab Calloway et ses évocations d’une jungle urbaine où évoluaient des Noirs attrayants, séduisants, décontractés et valorisés évoqués dans des chansons comme ses « Tarzan of Harlem » ou (Hep Hep) The Jumpin’ Jive de 1939. Count Basie et son orchestre (avec Lester Young et Roy Eldridge, que Kerouac admirait) comptaient parmi les têtes d’affiche de l’époque. Leur chanteuse fut un temps Helen Humes, qui interprète ici le rock Be-Baba-Leba en 1945 (dans le style rock « jump blues » au titre proche du futur « Be-Bop-A-Lula » de Gene Vincent en 1956). Leur détachement, leur humour, leur désinvolture, leur valorisation des Noirs et leur hédonisme sarcastique séduisaient ces jeunes en quête de sens et de liberté. En vivant l’instant présent de l’improvisation musicale, en appréciant ce mode d’expression spontané et en faisant corps avec le balancement du swing, cette nouvelle génération trouvait une réponse à une mort peut-être imminente ; elle se nourrissait de cette pulsion musicale de vie, qui donnait un sens à leur existence, un hommage à la vie elle-même — et un mode de vie de bohême. Cette anthologie plonge au cœur de l’esprit des hipsters. Les musiques de rythme des années 1936-1962 furent la bande son de la génération beat, sa raison d’être originelle et une inspiration centrale dans la littérature beat.

La période d’après-guerre correspond aussi à la naissance du rock and roll originel, à la mode en 1949-1951, qui était initialement un dérivé du jazz de la période swing, une mutation explicitée dans le coffret Race Records - Black Rock ‘n Roll Forbidden on U.S. Radio 1942-1955 dans cette collection (on y retrouve l’un des premiers DJ de radio noirs, Jocko Henderson, qui s’exprimait toujours à l’antenne avec des rimes humoristiques d’une grande poésie). Une partie de l’attrait de ce nouveau genre excitant était dans le saxophone ténor « honk » (klaxon), un style outré rendu célèbre par son fondateur Illinois Jacquet, le flamboyant Big Jay McNeely ou le populaire Gator Tail, un morceau de l’orchestre de Cootie Williams avec le saxophoniste Willis « Gator » Jackson. En argot, un gator (alligator) était un passionné de musique de rythme. Dans ses notes préparatoires à On the Road3, Jack Kerouac commentait ainsi Gator Tail (1949):

« Je me fous de ce que les gens disent… des trucs sauvages comme ça, ça m’arrache de mes chaussures — c’est du whisky pur. On ne veut plus entendre parler des critiques de jazz et de ceux qui osent des questions sur le bop — j’aime mon whisky sauvage, j’aime que la fête du samedi soir soit folle, j’aime quand le sax ténor est rendu fou par une femme, j’aime que les choses BOUGENT, que ça balance, que je sois retourné, je veux être défoncé si je dois l’être, j’aime m’éclater avec la musique des rues ».

JAZZ MODERNE

La Beat Generation est fondamentalement issue de la rencontre entre trois écrivains et poètes inspirés par le monde souterrain du jazz et la littérature. William Burroughs et Allen Ginsberg s’étaient rencontrés en 1943 ; Jack Kerouac fréquentait l’université Columbia de New York, où il a rencontré Ginsberg en 1944 avant de faire connaissance avec Burroughs. Neal Cassady (un des amants de Ginsberg), Herbert Huncke et d’autres ont été d’importants auteurs. Gregory Corso et Peter Orlovsky (concubin de Ginsberg) ont rejoint ce courant beat. Déjà marqués par le jazz, ils plongeaient aussi leurs racines dans les courants artistiques romantiques, le surréalisme français, le modernisme et divers auteurs anglophones audacieux. En 1945-1947 ils ont adopté le nouveau jazz moderne virtuose qui surgissait en phase avec leur propre génération : Charlie Parker et Dizzy Gillespie étaient les fondateurs et les emblèmes du be bop marginal et très controversé. Alcoolique, héroïnomane, Parker brûlait la chandelle par les deux bouts comme le firent à leur tour Kerouac (alcool) et Burroughs (opiacés). Les beats expérimentaient toutes les drogues et Ginsberg n’était pas en reste.

Dans les années 1940 Seymour Wyse partageait une passion pour le jazz avec son ami proche Kerouac. Il fréquentait Minton’s Playhouse, club clé du be bop ; il a produit et enregistré quelques disques dans l’après-guerre avec son propre matériel et fait découvrir à l’écrivain nombre d’artistes, qu’ils allaient voir jouer ensemble à New York après des séances de cinéma. Ginsberg avait lui aussi un goût prononcé pour le be bop, un style qui remettait complètement en question le jazz. Très influent à partir de 1947, le bop était engagé dans la valorisation de ces musiques en tant qu’œuvres artistiques (et non plus une simple musique de danse)4. Les amis se rendirent à des concerts des boppers Parker et Gillespie, Thelonious Monk, Bud Powell — entre autres artistes inclus ici — qui les ont fortement marqués. D’autres excentriques ont laissé une profonde empreinte sur la scène des hipsters : entre scat, poésie, sketch et surréalisme, les personnages cultes Slim Gaillard et Babs Gonzales jouaient eux aussi avec les mots. Dans son chef-d’œuvre Howl (1955), Allen Ginsberg fait largement allusion au jazz moderne qui constituait un exemple d’expression de résistance, d’originalité, de liberté qui l’inspirait et faisait reculer les barrières esthétiques et raciales.

Le be bop et l’esprit libre véhiculé par le jazz sont évoqués par Duke Ellington qui, à travers son personnage de Madam Zajj (« jazz » à l’envers), rend hommage à une danseuse de Congo Square à la Nouvelle-Orléans. Cette diva y est amoureuse de Caribbee Joe, un Antillais représentant les valeurs viriles et séduisantes héritées d’une Afrique fantasmée. En narrant lui même ses poèmes mis en musique, dès 1956 le géant Ellington s’inscrivait nettement dans le courant beat. Son génial album A Drum Is a Woman apportait un point de vue neuf, analogue à celui exprimé par Ginsberg dans Howl, paru la même année. Il inventait la forme que, trois ans plus tard, Kerouac utiliserait dans ses enregistrements avec Steve Allen au piano : poésie parlée sur un accompagnement jazz. Dans Zajj’s Dream, Duke évoque le bop et ses attributs (dont le stéréotype du béret de Dizzy), la vie urbaine dans une mégapole, une soucoupe volante et le départ vers l’aventure : « Tu peux retirer le garçon d’une ville, mais tu ne peux pas retirer la ville d’un garçon ». Il y incorpore même un violon évoquant les musiques juives d’Europe de l’est, suggérant peut-être de façon fantasmagorique la présence de poètes comme Ginsberg.

HIPSTERS

Norman Mailer commença son essai The White Negro par ces mots :

« Nous ne serons sans doute jamais capables de déterminer les dégâts que les camps de concentration et la bombe atomique ont faits dans l’inconscient de presque tous les vivants durant ces années. »

Selon lui, non seulement de nouvelles shoahs et de futures guerres atomiques étaient des menaces bien réelles, mais « une mort lente par conformisme, où tout instinct rebelle et créatif est asphyxié » n’était pas une réponse valable à la situation. Il ajouta : « C’est dans ce contexte lugubre qu’un phénomène est apparu : l’existentialiste américain — le hipster ».

Mezz Mezzrow, un clarinettiste juif de Chicago passionné par le blues et le jazz de la Nouvelle-Orléans, fut l’archétype des premiers hipsters écrivains blancs, qu’il inspira. Admirateur de Sidney Bechet émigré à New York dans les années 1920, Mezz s’était marié à une femme noire en pleine ségrégation et était le fournisseur en marihuana attitré de Louis Armstrong. Condamné plusieurs fois, il avait appris la musique en prison dans les bâtiments réservés aux Noirs où il demanda à être incarcéré. Son classique de la littérature entièrement écrit en argot jive, l’autobiographie Really the Blues (La Rage de Vivre) parue en 1946 a pour la première fois raconté la culture marginale des Afro-américains urbains et le monde souterrain du jazz. Ce livre essentiel participa au renouveau du jazz traditionnel New Orleans d’après-guerre5 et a largement contribué à fasciner, à donner identité, direction et vocabulaire jive à la Beat Generation. Norman Mailer expliquait que le jive (jargon du jazz/argot noir) permettait d’exprimer des sentiments et sensations inconnus des « squares » (conformistes). Le lexique jive est ici utilisé par Slim Gaillard sur Slim’s Jam (1945).

J’ai lu Really the Blues au comptoir de la librairie de l’université Columbia au milieu des années 40. Il a été pour moi le premier signal dans la culture blanche du monde noir souterrain branché qui avait préexisté avant ma propre génération. — Allen Ginsberg

Mailer estimait dans son essai que la seule « bague de mariage » capable de rapprocher les Blancs du mode de vie des jazzmen afro-américains était la consommation de marihuana qui mettait les vipers (fumeurs) « à l’aise » (mellow). Illégale à partir de 1937 dans tous les États-Unis, elle était fumée sous forme de reefer (feuille de chanvre roulée). Le « jive » (« baratin ») au sens multiple d’arnaque, de culture, de bagout et de chanvre, est chanté ici par Cab Calloway dans (Hep Hep) The Jumpin’ Jive (1939) où figure aussi le terme « hep » (« branché ») orthographié « hip » par les hipsters d’après-guerre. Les vipers (référence au sifflement produit par l’inhalation de la fumée acre d’un reefer) sont évoqués ici dans le classique You’se a Viper de Stuff Smith6 et, deux ans après la prohibition du chanvre, par The Cats and the Fiddle dans Killin’ Jive.

Déplorant la lâcheté ordinaire, Mailer jugeait que le vrai courage consistait à refuser le conformisme, et que « la seule réponse qui donnait la vie » était d’accepter la mort, le danger, de divorcer de la société, d’exister sans racines et de partir en voyage vers les « impératifs rebelles du soi ». Mailer était dans la suite logique de la pensée des zazous parisiens fous de « swing » pendant l’occupation, comme dans celle de D. H. Lawrence, qui dans les années 1920 avait dénoncé le puritanisme, la censure et la déshumanisation provoquée par la société moderne industrielle. Sous ses différentes formes (de Kierkegaard à Dostoïevski, Nietzche jusqu’à Sartre), le courant philosophique existentialiste en vogue dans l’après-guerre rejoignait à bien des égards la philosophie afro-américaine telle qu’elle s’exprimait dans le jazz : elle suggérait de vivre libre, indépendant, de façon passionnée et authentique. Antithèse du consumérisme ambiant et de la soumission aux valeurs traditionnelles, cette approche se retrouvait à New York, alors capitale du jazz, en Californie mais aussi à Londres et à Paris où des célébrités du jazz avaient déménagé, notamment Bechet, le batteur héroïnomane Kenny Clarke et parfois Miles Davis. les boîtes de jazz de Saint-Germain-des-Prés étaient fréquentées par Simone de Beauvoir, Juliette Greco, Boris Vian, Serge Gainsbourg et le groupe vocal des Double Six, qui enregistreraient bientôt avec Dizzy Gillespie.

« J’ai vu les meilleurs esprits de ma génération détruits par la folie, affamés hystériques nus, se traînant à travers les rues nègres à l’aube, en colère à la recherche d’une dose, des hipsters aux têtes d’anges brûlant pour l’ancienne connexion paradisiaque avec la dynamo étoilée dans la machinerie de la nuit, qui pauvres en lambeaux les yeux vides défoncés sont assis fumant dans l’obscurité supernaturelle d’appartements sans eau chaude, flottant à travers les hauteurs de villes, contemplant le jazz […] » — Allen Ginsberg, Howl7

SEXE

Dans les années 1930, le grand écrivain Henry Miller (interdit aux États-Unis jusqu’en 1961) avait utilisé un langage explicite dans ses critiques sociales radicales. La « révolution sexuelle » de l’Autrichien Wilhelm Reich, pour qui l’orgasme était une réponse individuelle aux démons de l’humanité, suggérait elle aussi un hédonisme sexuel en phase avec les aspirations d’une partie de la jeunesse. Toujours pour Norman Mailer dans The White Negro, la conscience permanente de l’épée de Damoclès du lynchage avait conduit les Afro-américains à adopter les plaisirs « physiques » fondamentaux (essentiellement le sexe). En 1947 dans sa chanson Crazy World, Julia Lee résumait cette philosophie deux ans après Hiroshi-ma avec son « baiser atomique » précurseur du futur slogan « faites l’amour pas la guerre » (de hipster à hippie ?) :

La paix est si facile/Il suffit de regarder pour la voir/Allons tous vers la romance/Et on sera trop occupés pour se battre/Voilà maintenant vous avez la réponse/L’amour fait tourner ce monde fou/Toutes les paroles de guerre seront oubliées quand le baiser atomique sera découvert

Le jargon noir était basé sur la métaphore et la litote. Pratiquer le sexe se disait « rock and roll » — représenté ici par le Rock and Roll de Wild Bill Moore (1948). Il va sans dire qu’avec son langage « rock and roll » explicite, son goût pour l’alcool (légalisé une décennie plus tôt) et le chanvre récemment interdit, le jazz/rock noir de la décennie d’après-guerre était un concentré des cauchemars de l’Amérique8. Sans parler de l’homosexualité/bisexualité de Kerouac, Ginsberg et Burroughs. Kerouac et ses amis vivaient à San Francisco, ville aux mœurs très libres, à la fin des années 1950. En Californie Gerry Mulligan et Chet Baker y alimentaient le jazz moderne avec un son original, le cool jazz. Dans American Haikus, Kerouac cherche à mettre ses poèmes sur le même plan que les improvisations des musiciens. Il y alterne ses paroles a capella avec les phrases de saxophone ; Pour lui, les idées de mots écrits avaient jailli spontanément et sont analogues aux improvisations des musiciens.

BEAT

Le terme « beat » (« battu ») est issu de l’argot du cirque et du carnaval. Il renvoyait aux conditions de vie des forains, qui devaient se soumettre à des règles contraignantes. C’est en discutant avec l’écrivain John Clellon Holmes que Kerouac a suggéré « on pourrait dire que nous sommes une beat generation » (« une génération battue »). Avoir perdu une bataille signifiait pour lui la condition préalable à une prise de conscience menant à une nouvelle et meilleure approche de la vie. Pour ensuite prendre un nouveau départ.

Le terme beat signifie aussi « rythme ». Il a été utilisé en ce sens par Kerouac dans l’un de ses enregistrements les plus significatifs, où il rapproche le sens « battu » du sens « rythme » et de « béatitude » :

Tout est pour les battus

C’est la génération battue

C’est BÉ-AT

C’est ce rythme qu’il faut garder

Le rythme du cœur

C’est être battu

Et dans le monde ici-bas

Comme une bassesse record

Comme une ancienne civilisation

Les esclaves ramaient au son du beat

Et les serviteurs faisaient tourner la poterie au son du beat

— Jack Kerouac, San Francisco Scene

(The Beat Generation), 1960

Louis, le père d’Allen Ginsberg était un poète juif qui enseignait l’anglais au collège ; Naomi la mère d’Allen souffrait de crises de paranoïa aigüe causant un déséquilibre important dans la famille. Comme on peut le comprendre, le pacte germano-soviétique de 1939 avait exacerbé l’anticommunisme aux États-Unis, qui s’apprêtaient à entrer en guerre contre le Japon (Pearl Harbor, décembre 1941) et leurs alliés l’Allemagne, l’Italie et implicitement l’Union Soviétique (attaquée à son tour par Hitler en juin 1941, l’URSS devint ensuite l’alliée objective des États-Unis). Naomi Ginsberg fréquentait néanmoins différentes réunions d’extrême-gauche, y compris celles du Parti Communiste Américain où elle emmena parfois son fils adolescent pendant la guerre, une activité pour le moins très subversive à cette époque. Elle passa près de quinze ans dans un hôpital psychiatrique, une épreuve pour son fils qui en fera le sujet de Kaddish, un de ses plus célèbres poèmes. Le mouvement beat était en gestation quand le Japon capitula en août 1945 après les bombes atomiques d’Hiroshima et Nagasaki — tandis que l’URSS conquérait l’Europe de l’est. La Beat Generation a germé pendant la guerre froide États-Unis/URSS qui a suivi. Elle s’est développée pendant la guerre de Corée (juin 1950-juillet 1953), un pays convoité et armé par la Chine communiste de Mao et l’URSS, comme le serait également le Viêt Nam à partir de 1955.

À la suite des années de reconstruction d’après-guerre menées par le président Harry Truman, le nationalisme, la religion et le conservatisme ont prospéré au cours de la présidence du général Dwight Eisenhower (1953-1961). Après plus de vingt ans de désastre économique, de guerre mondiale et de privations, une fois les guerres terminées la jeunesse américaine enfin débarrassée de ses obligations militaires aspirait à une libération des mœurs et des esprits, qui semblait hors de portée dans les années 1950. C’est dans un contexte consumériste et réactionnaire que, rejetant les valeurs traditionnelles, les pionniers de la Beat Generation ont créé dans leur appartement de la 11e rue dans le quartier de Greenwich Village à New York une culture marginale, radicale, antimilitariste. Aux États-Unis cette période fut entachée par le racisme, l’antisémitisme et une répression anticommuniste marquée par un cortège de pratiques illégales, comme d’iniques listes noires (la période du mccarthysme, 1950-1957). En signe de protestation, des artistes comme Orson Welles, Charlie Chaplin et Bertolt Brecht quittèrent les États-Unis.

SUR LA ROUTE

En 1945 la chanson Route 66 par Nat « King » Cole était un succès (la rare version de son compositeur Bobby Troup est aussi incluse ici). Il était annonciateur de la popularité du futur livre On the Road (« Sur la route »). De retour d’un long périple initiatique à travers les États-Unis avec son amant Neal Cassady, c’est en avril 1951 que Kerouac a rédigé la nouvelle qui le rendrait célèbre. Écrit sous l’effet de la benzédrine, le livre a été refusé par plusieurs éditeurs en raison de son style décousu et de son contenu risqué. C’est Malcolm Crowley, un écrivain et éditeur de Faulkner et Hemingway (et popularisateur du terme « lost generation » introduit par Gertrude Stein se référant à la génération de la Première Guerre Mondiale), qui le publia six ans plus tard. Ginsberg, Burroughs, Corso et Huncke avaient déjà publié des textes controversés, évoquant la marge de la société de façon explicite, quand Jack Kerouac, un catholique convaincu de descendance française, connut une improbable célébrité à la suite de la publication de On the Road le 5 septembre 1957. Cette nouvelle largement autobiographique évoque le long voyage à travers les États-Unis de deux amis (un seul des deux y est décrit comme homosexuel) libertins et amateurs de drogues à la recherche de Dieu. Ginsberg et Cassady y sont largement évoqués, ainsi que Kerouac lui-même, sous des pseudonymes9. Jack Kerouac fut alors brusquement célébré comme le chef de file d’un nouveau mouvement littéraire. Ses amis poètes et écrivains bénéficièrent eux aussi de la charge d’une popularité aussi soudaine qu’inattendue. Au moment précis où commençait la conquête spatiale avec un voyage d’un autre genre — celui du spoutnik mis en orbite le 4 octobre 1957 —, surgissait la Beat Generation. Son impact fut immense sur l’Amérique. Simultanément avec le renouveau de la musique folklorique (représentée ici par Dave Van Ronk et Bob Dylan) et en phase avec la fulgurante mode pour le rock dans le grand public blanc (ici dans Kookie’s Mad Pad, une satire des beatniks de 1959), elle fit partie des bouleversements culturels qui à l’aube des années 1960 surgissaient déjà dans le monde entier. Ce coffret vise à fournir une référence sonore couvrant les différents aspects de ce mouvement important : poésie, prise de parole (les loufoques Lord Buckley, ici dans un portrait délirant de Jésus Christ, et Lenny Bruce. Leurs deux carrières ont été brisées par l’ordre établi), musiques et commentaires, comme ceux de Jack Kerouac ici dans Is There a Beat Generation?.

LITTÉRATURE

L’humilité signifie bien être battu, une vertu obligatoire que nul n’exhibe à moins d’y être obligé.

— William Burroughs

En 1944, plus âgé que les autres et lecteur de Jean Cocteau, Burroughs a offert A Vision de Yeats à Ginsberg et The Decline of the West d’Oswald Spengler à Kerouac. La nouvelle de Spengler les a particulièrement marqués. L’auteur y décrit un monde occidental détruit où une nouvelle culture humaniste, une philosophie utopiste où l’art, non censuré, jouait un grand rôle politique.

Pendant les douze années qui ont précédé le succès de Kerouac, les trois principaux écrivains de la Beat Generation avaient rédigé des poèmes et des nouvelles suggérant une libération sans bornes, incluant la liberté sexuelle, y compris homosexuelle et inter-raciale, dans un pays où la ségrégation raciale, la pudibonderie et l’hétérosexisme étaient la règle. Le mccarthysme combattait violemment l’homosexualité (illégale), ce qui donnait lieu à des suicides, etc. Effectuant une psychanalyse avec un collègue de Sigmund Freud, Burroughs envisageait de devenir lui-même psychanalyste et exerçait ses talents sur Kerouac et Ginsberg. Imperméable aux valeurs et au mode de vie conformiste, il s’était aussi accroché à la morphine que lui avait fait découvrir Herbert Huncke en 1945. Ancien détective privé qui avait fréquenté la pègre, il collectionnait et utilisait obsessionnellement les armes à feu. En 1946 Burroughs emménagea sur la 115e rue ouest de New York avec sa future épouse Joan, qu’il tua accidentellement en 1951 en jouant à Guillaume Tell. Les Beats décrivaient des expériences aux drogues dures, y compris l’héroïne qui était illégale (William Burroughs, Junkie, 1953), l’alcool et les amphétamines (alors légaux). Ces expériences étaient également vécues par nombre de musiciens de jazz et de blues comme Ray Charles ou Charlie Parker.

Intéressés par les cultures étrangères, Ginsberg et Kerouac ont bientôt fait état d’un intérêt pour les spiritualités asiatiques. Ils continuaient à pratiquer assidûment le voyage et devinrent bouddhistes en 1954 — en bref ils exprimaient leurs penchants pour la transgression, l’aventure et cherchaient à vivre des expériences sans barrières, comme leurs prédécesseurs de l’avant-garde l’avaient suggéré avant eux. Arthur Rimbaud, Paul Verlaine, Oscar Wilde et Walt Whitman étaient aussi homos ou bisexuels, tout comme Burroughs, Kerouac, Ginsberg, Cassady et Orlovsky. Les Beats étaient aussi marqués par James Joyce et sa technique d’écriture spontanée expérimentée dans Ulysses, ainsi que par des poètes d’avant-garde comme William Carlos Williams (le mentor de Ginsberg venait lui aussi de Paterson, New Jersey), Emily Dickinson, W. H. Auden, e. e. cummings et Walt Whitman ; ils avaient lu William Blake (adoré par Ginsberg), Thomas Mann, Thomas Wolfe, John Dos Passos, Jack Black, Ezra Pound, Marcel Proust, Albert Camus, André Gide, Louis-Ferdinand Céline, André Breton et Franz Kafka.

Après plusieurs déconvenues et une cure de désintoxication, Burroughs s’installa en 1954 à Tanger (Maroc). C’est là qu’il écrit Le Festin nu (Naked Lunch, 1959) pendant quatre ans sous l’influence du haschisch, d’opiacés et de son ami Bryon Gysin qui l’introduit à la technique du découpage/collages au hasard. Le livre fut achevé au « Beat Hotel », un hotel à bas prix situé 9 rue Gît-le-Cœur dans le quartier latin de Paris, où Ginsberg écrit une partie de son œuvre majeure Kaddish et Corso son poème « Bomb ». Le collage de rimes au hasard est une technique dont le surréaliste Tristan Tzara fut le pionnier et que Burroughs rendit célèbre (David Bowie rédigea par exemple des paroles de chansons assemblées par collage au début des années 1970). Cette technique fut aussi utilisée par Ginsberg dans « Kaddish ». La littérature de la Beat Generation a exploré et marqué la culture américaine en rejetant les modes de narration classiques ; à la manière d’André Breton avant eux, Kerouac, Cassady et Ginsberg ont par exemple utilisé des mé-‑thodes de rédaction privilégiant la spontanéité, résumé dans leur motto « première pensée, meilleure pensée ». Cette appro-che a été utilisée par la suite par Bob Dylan ou John Lennon, dont les chansons ont bouleversé le monde.

BEATNIKS

À la parution de On the Road en 1957, le succès de Jack Kerouac a été instantané grâce à un excellent article dans le New York Times. Ses amis de la Beat Generation représentaient soudain un nouveau mouvement littéraire et les éditeurs se disputaient leurs écrits. Après une longue période de marginalité, de misère, de controverses, de procès pour obscénité (Howl) et autres atteintes à l’ordre moral, le succès de la Beat Generation a marqué le départ d’une campagne de presse présentant Kerouac comme le porte-parole de sa génération. L’Amérique découvrait la contreculture et les stéréotypes beat ont aussitôt été mis en avant et moqués dans les médias. Clichés vestimentaires (collants et chaussons pour les dames, barbe, sandales et béret pour les messieurs) et expressions « jeunes » accrochaient : crazy (fou), goof (gaffe), dig (idée à creuser), pad (piaule), square (conformiste), hip (branché), hipster (personne branchée), cool (frais, plaisant, bien), a drag (ennu-yeux), visions (visions, rêves), knockin’ some z’s (dormir). D’autres pastiches et sarcasmes en résultèrent, comme ici l’irrésistible High School Drag de Phillipa Fallon (sur l’ennui), The Beat Generation (pertinemment plagié par le rockeur punk Richard Hell qui en fit «The Blank Generation» en 1977) et Kookie’s Mad Pad. Être ou ne pas être « cool » était devenu une question beat, tournée ici en dérision dans But I Was Cool par l’auteur et chanteur Oscar Brown, Jr. et les humoristes Del Close et John Brent (qui était aussi un poète beat) dans Cool et Uncool (1959).

Mais sept ans après la rédaction de son livre, Kerouac avait beaucoup mûri. À trente-cinq ans, il était passé à autre chose depuis longtemps et a mal supporté ce succès en décalage avec sa réalité. Passionné comme Ginsberg par le bouddhisme, auquel l’écrivain philosophe Alan Watts avait consacré un premier livre précurseur en 1957, il décrivait cette mode soudaine avec humour, autodérision et détachement. Questionné sur l’homosexualité alors tabou, Kerouac niait catégoriquement être gay. Son livre à succès Dharma Bums de 1958 a contribué à faire connaître la spiritualité indienne en occident. Pourtant peu après son triomphe, Kerouac fut très durement passé à tabac à New York par des hétérosexistes et craint ensuite toute apparition en public. Il se réfugia à San Francisco, ville réputée moins dangereuse pour les homos, et la première localité du monde où se construisait ouvertement une culture LGBT. C’est aussi là que Ginsberg rencontra son compagnon Orlovsky. On se rendait en Californie, symbole de la liberté et d’auto-stop, en empruntant la Route 66 pour qui Bobby Troup avait composé sa célèbre chanson du même nom. La publi-cation controversée de On the Road s’est produite en parallèle avec la pharaonique construction d’un gigantesque réseau d’autoroutes reliant les états (Interstate) lancée par Eisenhower en 1956. La civilisation automobile en marche produisait des représentations et désirs de liberté suggérés par le thème du voyage dans l’air du temps. Elle a inspiré nombre de films et de chansons : autostop, grosses motos, courses de hot rods, nouveaux modèles de voitures attirantes, extravagantes, etc. Cet essor gigantesque de l’industrie automobile est l’objet d’un coffret dans cette collection consacré à ces Road Songs (idéales pour être écouté en voiture !)10.

Le départ de Kerouac pour San Francisco a déplacé le centre de gravité du mouvement de la côte est à la côte ouest. D’autres auteurs, dont Gary Snyder, l’éditeur Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Philip Whalen, Carl Solomon, Kenneth Rexroth, Michael McClure, Lew Welch, Bob Kaufman, Amiri Baraka (Leroi Jones) et d’autres sont considérés être des contributeurs de la tendance beat. Plusieurs femmes ont activement participé à ce mouvement, à commencer par les épouses et concubines de Burroughs et Kerouac, bien que le sexisme propre à l’époque ait considérablement limité leur rôle.

INFLUENCE DE LA BEAT GENERATION

Alors que le terme « beatnik » (adhérent au mouvement beat) entrait dans le vocabulaire américain fin 1957, la notoriété de Kerouac coïncidait avec l’essor du mouvement pour les Droits Civiques des Afro-Américains. La contestation pour le désarmement et contre la bombe atomique se développaient. Le renouveau folk lié aux idées de la nouvelle gauche (portée par des intellectuels comme Herbert Marcuse) qui porterait le progressiste Kennedy au pouvoir en janvier 1961 attirait un public ouvert aux protest songs contestataires11 et à la lutte contre le racisme. Cette ouverture correspondait à une période charnière, à la fin de la période maccarthyste, survenue en 1957 avec la chute du sénateur McCarthy. Alors que la musique country était un pur produit du sud profond, peu apprécié dans les centres urbains du nord, l’Amérique blanche progressiste s’était ouverte aux negro spirituals de Mahalia Jackson, au folk blues, au gospel noir et aux musiques populaires caribéennes comme le merengue dominicain (et les musiques cubaines : rumba, mambo, cha cha chá, etc.) dont l’énorme succès de Harry Belafonte Calypso en 1956 fut l’un des chevaux de Troie12. Bientôt, ce serait au tour des musiques brésiliennes (bossa nova, etc.). La popularité des intellectuels de la Beat Generation s’est aussi produite simultanément au succès foudroyant du rock and roll à la mode en 1956-195713, qui fut aussi un bouleversement majeur pour les mentalités américaines. Adoptés par la jeunesse pendant cette période et bien que différent du mouvement beat tourné vers le jazz, le rock et le folk de cette période ont eux aussi accompagné le mouvement des Droits Civiques, lancé en 1955 par un acte de résistance de Rosa Parks. Jazz, rock, folk et d’autres courants artistiques (cinéma et bande dessinée beatnik, de Peanuts à Gaston Lagaffe jusqu’au Grand Duduche) portant les prises de conscience et le progrès au sein de la société ont été marqués de près ou de loin par ces nouveaux poètes aux idées osées, choquantes. À leur manière libertaire leur quête spirituelle, leur rejet du matérialisme, leurs descriptions de la condition humaine et leurs attitudes aventureuses ont précédé, annoncé et inspiré le grand mouvement d’émancipation et de libération de la jeunesse des années 1960. S’il est vrai que des artistes comme Bo Diddley (ici dans un morceau de « signifying », un héritage des joutes verbales traditionnelles de la jeunesse), Billie Holiday, Chuck Berry et bien d’autres avaient déjà chanté des thèmes adultes aux paroles d’une grande force, le style Beat a fortement influencé des géants comme Leonard Cohen, les Beatles (Paul McCartney jouera même sur un disque d’Allen Ginsberg), les Rolling Stones, ou encore Jim Morrison au sein des Doors, qui comme Lou Reed et Dylan comptent parmi les premiers à avoir apporté une dimension littéraire sophistiquée qui a renouvelé le rock et la chanson. Par leurs publications engagées incitant à une libération des esprits, les auteurs de la Beat Generation ont ainsi considérablement marqué les mentalités de la décennie à venir, où les hipsters, amateurs de contreculture et de jazz étaient étiquetés beatniks avant que les termes « freaks » puis « hippies » ne s’imposent vers 1965. I Sing of Olaf, un poème délirant de e. e. cummings, est un cadeau de Roger Steffens, un hipster qui a passé les années 1960 sur la route à lire de la poésie.

Dès 1957, le jazz lui-même était marqué par la Beat Generation. Duke Ellington célébrait la négritude et le jazz be bop de la décennie précédente avec Madam Zajj sur la piste de Caribbee Joe ; Eddie Jefferson écrivait des paroles qu’il adaptait à la mélodie des solos des boppers et les chantait, mélange de poésie, de scat et d’excentricité surréaliste moderne. Marqué par Lambert, Hendricks and Ross il choisit lui aussi de rendre hommage au jazz moderne, ici une reprise du chef-d’œuvre de Miles Davis So What. Sa formule influença jusqu’au groupe vocal parisien des Double Six, où Mimi Perrin releva le défi et reprit la formule en français, sur un incroyable premier album contenant des classiques du jazz moderne comme ici Scrapple From the Apple, (À bâtons rompus) — encore une composition de Charlie Parker, l’ange tutélaire de tout le mouvement.

Bruno Blum, avril 2016.

© FRÉMEAUX & ASSOCIÉS 2016

Merci à Chris Carter, Pascal le Gras, Philippe-Alain Michaud, Gilles Pétard, Lou Reed, Nicolas Roche et Roger Steffens.

1. The New Cab Calloway’s Hepster Dictionary of Jive (1944).

2. Norman Mailer, The White Negro (City Lights, San Francisco, juin 1957) Édition française : à paraître aux éditions Le Castor Astral (traduction de Bruno Blum). Le Blanc-Nègre, inclus dans le Magazine Esprit n°2 (Paris, 1er février 1958).

3. Introduction de Ann Charters à l’édition Penguin (Londres, 1991), p. XV du livre On the Road de Jack Kerouac.

4. Lire le livret et écouter The Birth of Be Bop 1940-1945 (FA 046) et les œuvres complètes de Charlie Parker dans cette collection.

5. Lire le livret et écouter New Orleans Revival 1940-1954 (FA 5135) dans cette collection.

6. Une célèbre reprise de You’se a Viper par Fats Waller est parue sous le nom de « The Reefer Song ».

7. Allen Ginsberg, début de Howl, 1955 (Harper and Row, Collected Poems 1947-1980). Traduction de Bruno Blum.

8. Lire le livret et écouter Race Records - Black Rock Music Forbidden on U. S. Radio 1942-1955 (FA 5600) dans cette collection.

9. Les éditions Viking à New York ont publié en 2007 le manuscrit originel intégral, sans les coupes décrivant des scènes de sexe, et en utilisant les vrais noms.

10. Lire le livret et écouter Road Songs - Car Tune Classics 1942-1962 (FA5401).

11. Lire le livret et écouter Protest Songs, à paraître dans cette collection.

12. Lire le livret et écouter Harry Belafonte - Calypso Mento Folk 1954-1957 (FA 5234) dans cette collection.

13. Lire les livrets et écouter Race Records - Black Rock Music Forbidden on U.S. Radio 1942-1955 (FA 5600), Rock Instrumentals Story 1934-1962 (FA 5426), Roots of Punk Rock Music 1926-1962 (FA 5415) et la série The Indispensable : Bill Haley 1948-1961 (FA 5465), Little Richard 1951-1962 (FA 5607), Rockabilly 1951-1960 (FA 5423), Elvis Presley 1954-1956 (FA 5361), volume 2 1956-1957 (FA 5383), Chuck Berry 1954-1961 (FA 5409), Bo Diddley 1955-1960 (FA 5376), volume 2 1959-1962 (FA 5406), Eddie Cochran 1955-1960 (FA 5425), Gene Vincent 1956-1958 (FA 5402), volume 2 1958-1962 (FA 5422), Roy Orbison 1956-1962 (FA 5438), etc.

The Beat Generation

Hep Cats, Hipsters and Beatniks - 1936-1962

By Bruno Blum

The only thing that one never regrets are one’s eccen-tricities.

— Oscar Wilde

The “Beat Generation” is an American literary movement linked to jazz and its subculture, that of the original African-American “hep cats” (“connoisseurs”). Great musicians, including Cab Calloway, Lester Young, Roy Eldridge, Louis Jordan, Slim Gaillard, Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie, were emblematic of those hep cats’ state of mind. They were later called “hipsters”, sometime during the war1. In those days of racial segregation, their music and free-spirited lifestyle fascinated some open-minded White people who attended jazz dance halls and clubs in New York City. They soon took on various elements of this radical African-American culture, in turn becoming hipsters as well. Some of those White people embraced this jazzmen’s culture and contributed through poems and short stories, in which jazz and its mysteries were presented in an attractive way.

Great White musicians were hipsters, too. They played with Black people and included Gene Krupa, Dodo Marmarosa, Gerry Mulligan and Chet Baker (as well as numerous Jews, such as precursors Benny Goodman, Artie Shaw and Mezz Mezzrow, then Buddy Rich, Doc Pomus, Stan Getz, Barney Kessel, Zoot Sims, Al Cohn, Lee Konitz…). All were part of this libertarian culture, which rejected racism. Hipsters’ non-conformism ran through a new underground literary wave, named The Beat Generation as early as 1950, only to become very influential after the publication of Jack Kerouac’s book, On the Road, which caused a sensation in September of 1957.

In this classic novel, Kerouac told an account of his travelling adventures in a pretty much autobiographical style that was fresh, spontaneous and direct. According to its author, his style could be compared to jazz music improvisation. Right from day one of its publication, the American media suddenly publicized the subversive Beat Generation writers, who all had very different personalities, including Ginsberg, Kerouac and Burroughs. Stereotypes of the “beat way of life” were emphasized and sometimes mocked: easygoing morals, slackness, carefreeness, pacifism and an informal tone contrasted with the conformism and puritanism of the Eisenhower years — a time when antisemitism and racism prevailed.

This sudden notoriety also gave the young urban dropouts of the time a new name, or perhaps a tag: the beatniks. Beatnik culture spread around and went through a metamorphosis from 1957 and on through the 1970s, leaving a deep mark on the world of arts and opinions of the time, setting the tone for beatniks and freaks, then for hippies and punks alike. The Beat Generation has deeply influenced literature and cinema (The Man With the Golden Arm, Otto Preminger, 1955 with Frank Sinatra, A Bucket of Blood, Roger Corman, 1959 or The Flower Thief, Ron Rice, 1960), as well as American rock culture, as can be felt in the lyrics and styles of Bob Dylan, The Velvet Underground and The Doors.

HEP CATS, SWING & ROCK & ROLL

Ben Hecht: One thing I noticed in the writings of you and your pals, Mr. Ginsberg, particularly, is that you have an affinity for negroes. Is it that the negro is an authentic, automatic beat, without having to put on a title?

Jack Kerouac: Yeah, he is the original beat. He’s full of glee. Well, they have a lot of fun; you’ve noticed that negroes have a lot of fun.

— Interview with Jack Kerouac, 1958

In his essay The White Negro2, twice-Pulitzer Prize winner Norman Mailer explained that an awareness raised by World War II atrocities had lead to a new attitude. In spite of the prevailing racism, White hipsters familiarised themselves with African-American hep cat culture. Facing the irony of their oppressed existence, Black artists had forged a peculiar, hedonistic attitude which appealed to some of the most assertive youth.

The true meaning of the Beat movement, as spelled out by Kerouac and Ginsberg, was in many ways a celebration of the jazz and blues spirit: the romanticism of the musicians’ way of life, of nomadic, wandering performers, bohemian lifestyles, free dancing, free sex, free and spontaneous expression… hep cat culture included alcohol consumption (Louis Jordan, How High Am I?, 1944) and smoking marihuana.

It was popularised in pre-war days by such eccentric stars as Cab Calloway, whose evocations of an urban jungle included easygoing, attractive, seductive, developing Blacks, as sung in tunes like “Tarzan of Harlem” or the 1939 classic (Hep Hep) The Jumpin’ Jive. Count Basie and his Orchestra (featuring Lester Young and Roy Eldridge, who Kerouac admired) ranked among the main bill toppers then. Their singer was once Helen Humes, who sung her 1945 rock tune, Be-Baba-Leba (in a “jump blues” rock style, bearing a title similar to Gene Vincent’s “Be-Bop-a-Lula” in 1956).

Their detachment, humour, casualness and validation of Blacks, as well as their sarcastic hedonism seduced White people in search of meaning and freedom. When living the flashing, present moment of musical improvisation and appreciating this spontaneous means of expression, together with the rocking ebullience of swing, some of this new generation found an answer to death, which by then felt like it might be pending, imminent even. It fed on the musical pulse of life, which gave their very existence sense, a tribute to life itself, within a bohemian lifestyle.

This anthology immerses the listener in the heart of the hipsters’ spirit. The rhythm musics of the 1936-1962 years were the Beat Generation’s soundtrack, its basic raison d’être, and a central inspiration for beat literature.

The post-war years also corresponded with the birth of original rock and roll, which by 1949-1951 was a new trend, initially derived from swing-era jazz, a mutation made explicit in the compelling Race Records - Black Rock ‘n’ Roll Forbidden on U.S. Radio 1942-1955 in this series (where Jocko Henderson, one of the first Black DJs, who expressed himself with poetic, funny rimes on the air, can also be heard). Part of early rock’s attraction was thanks to the over-the-top, “honk” tenor sax style made famous by its founder Illinois Jacquet, Big Jay McNeely, as well as the popular Gator Tail, a tune by Cootie Williams’ Orchestra featuring sax player Willis “Gator” Jackson. In jive talk, a gator meant a rhythm music fanatic.

In his preliminary notes for On the Road3, Jack Kerouac commented on Gator Tail (1949):

“I don’t care what anybody says… but I’m pulled out of my shoes by wild stuff like that — pure whiskey! Let’s not hear no more about jazz critics and those who wonder about bop: — I like my whiskey wild, I like Saturday night in the shack to be crazy, I like the tenor to be woman-mad, I like things to GO and rock and be flipped, I want to be stoned if I’m going to be stoned at all, I like to be gassed by a back-alley music…”

MODERN JAZZ

Fundamentally, the Beat Generation sprung out of the encounter of three writers and poets inspired by the underground world of jazz, as well as literature. William Burroughs and Allen Ginsberg had met in 1943; Jack Kerouac attended New York’s Columbia University, where he met Ginsberg in 1944, before meeting Burroughs. Neal Cassady (an early lover of Ginsberg’s), Herbert Huncke and others were also important authors.

Gregory Corso and Peter Orlovsky (Ginsberg’s life partner) joined the beat movement. Besides jazz influences, they also had roots in romanticism, French surrealism, modernist art trends, as well as various daring writers. By 1945-1947 they had adopted the new, virtuoso modern jazz in phase with their own generation. Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie were the founders and emblems of the new, controversial, underground modern jazz named be bop. An alcoholic and heroin addict, Parker burned the candle at both ends, as did Kerouac (alcohol) and Burroughs (opiates) also. The beats experimented with all kinds of drugs and Ginsberg was far from outdone.

In the 1940s, Seymour Wyse shared with his close friend Kerouac a passion for jazz. He hung out at Minton’s Playhouse, the key be bop club and he even produced and recorded a few postwar records with his own gear. He took the writer to discover several musicians in the clubs they attended after going to the movies. Ginsberg was also well into be bop, a new style that turned the jazz world upside down. Very influential after 1947, bop was involved in the upgrading of jazz music into being regarded as pieces of art (and not just simply dance music).

The two friends attended Parker and Gillespie, The-lonious Monk and Bud Powell gigs, among other musicians also heard in this set. Other eccentric musicians also made their mark on the hipster scene, blending scat, skit, poetry and surrealism: cult heroes Slim Gaillard and Babs Gonzales also played with words. In his 1955 masterpiece, Howl, Allen Ginsberg alludes to modern jazz, which at the time was a major expression of resistance and originality, an example of artistic freedom that inspired him and pushed back aesthetic and racial boundaries.

Be bop and the free spirit carried by jazz are also brought up by Duke Ellington through his character Madam Zajj (“jazz” turned upside down), a tribute to a New Orleans’ Congo Square dancer. In this song the diva is in love with Caribbee Joe, a seductive West Indian embodying manhood, in African fantasy fashion. In narrating his own poems put to music, as early as 1956 Ellington, the jazz giant, clearly fell within a beat approach. His brillant album A Drum Is a Woman brought an analogous, fresh perspective to Ginsberg’s Howl published that same year. It was inventing the form that, three years later, Kerouac would use in his recordings with Steve Allen on the piano: spoken poetry over a jazz accompaniment. In Zajj’s Dream, the Duke alludes to bop and its clichés (including Dizzy’s French beret), urban life in a megalopolis, a flying saucer and a take off to adventure: “You can take the boy out of a city, but you can’t take the city out of the boy.” He even included a violin reminiscent of Eastern European Jewish music, perhaps phantasmagorically suggesting the presence of poets such as Ginsberg.

HIPSTERS

Norman Mailer started his essay The White Negro with these words: “Probably, we will never be able to determine the psychic havoc of the concentration camps and the atom bomb upon the unconscious mind of almost everyone alive in these years.” According to him, not only more shoahs and future atomic wars were real threats, but “a slow death by conformity, with every creative and rebellious instinct stifled” was no valid answer to this situation. He added: “It is on this bleak scene that a phenomenon has appeared: the American existentialist — the hipster.”

Chicago-based, Jewish clarinet player Mezz Mezzrow was passionate about New Orleans jazz and blues. He was the archetype of the first White hipster writers, which he inspired. A Sidney Bechet devotee, he emigrated to New York City in the 1920s, married a Black woman at a time when racial segregation was in full swing and became Louis Armstrong’s appointed marihuana dealer. Convicted several times, he learned music in the Black section of the jail, where he’d asked to be imprisoned. Fully written in jive slang, his Really the Blues autobiography (1946) told for the first time the reality of urban African-American subculture and jazz. This essential book participated in the postwar traditional jazz revival4 and has widely contributed to giving identity, fascination, direction and vocabulary to the Beat Generation. Norman Mailer explained that jive (jazz jargon/slang) allowed its users to express feelings and sensations unknown to ‘squares.’ Some of this jive lexicon is heard here on Slim Gaillard’s, Slim’s Jam (1945).

“ ‘Really the Blues,’ read at the counter of the Columbia University Bookstore in the mid-forties, was for me the first signal into white culture of the underground black, hip culture that preexisted before my own generation.”

—Allen Ginsberg

Norman Mailer reckoned that the one “wedding ring” capable of bringing White people closer to the African-American jazzmen’s lifestyle was the smoking of marihuana, which made the vipers (smokers) mellow. Made illegal in all of the USA in 1937, it was smoked in reefer form (a rolled up hemp leaf). The word jive (hot air) had multiple meanings, including rip off, culture, slang, spiel and weed. It is sung here by Cab Calloway in (Hep Hep) The Jumpin’ Jive (1939) where the word “hep” (“cool”) is also heard. Vipers were named after the noise produced by inhaling acrid reefer smoke. Vipers are also alluded to in Stuff Smith’s classic, You’se a Viper, and, two years after the prohibition of marihuana, in The Cats and the Fiddle’s hilarious Killin’ Jive.

Lamenting ordinary cowardice, Mailer felt that true courage meant refusing conformism, and that the “only answer giving life” was to accept death, danger, to divorce from society, to live without roots and to travel towards the “rebel imperatives of the self.” Mailer followed the same logic as the swing-crazy Parisian zazous during Nazi occupation. He also was in phase with D. H. Lawrence, who condemned puritanism, censorship and dehumanisation in the modern industrial society of the 1920s.

In its different forms, the postwar existentialist philosophical trend met African-American philosophy, as found in jazz: it suggested living a free, independant, passionate and authentic life. It was the antithesis of consumerism and submission to traditional values. It could be found in jazz’s capital city of New York, as well as in California, London and Paris, where several notorious jazzmen had moved. These included Bechet, heroin addict drummer Kenny Clarke and, at times, Miles Davis. Paris Saint-Germain-des-Prés jazz clubs were attended by Simone de Beauvoir, Boris Vian, Juliette Greco, Serge Gainsbourg and Mimi Perrin’s outstanding Double Six vocal group, who would soon record with Dizzy Gillespie.

SEX

In the 1930s, the great writer Henry Miller (forbidden in the USA until 1961) had used explicit language in his radical social criticism. Austrian writer Wilhelm Reich’s “sexual revolution” — to whom orgasm was the individual’s response to mankind’s demons — also suggested a sexual hedonism much of the youth craved for. To Norman Mailer in The White Negro, the ‘sword of Damocles’ of lynching had led African-Americans to rely on fundamental “physical” pleasures (essentially, sex). Two years after Hiroshima, in her 1947 Crazy World song, Julia Lee summed up this “atomic kiss” philosophy, which anticipated the “Make love, not war” slogan (from hipster to hippie?):

Peace is so easy/It’s plainly in sight/Let’s all get romantic/We’ll be too busy to fight/Now there you’ve got the answer/Love makes this crazy world go round/All talk of war will be forgotten when the atomic kiss is found

Black jargon was built around metaphors and litotes. Sex was called rock and roll, as heard in Wild Bill Moore’s Rock and Roll (1948), found here. Needless to say, with its explicit rock and roll parlance, its taste for alcohol (legalised only a decade earlier) and recently prohibited marijuana, black jazz/rock of the postwar decade was packed with America’s worst nightmares5. Not to mention Kerouac, Ginsberg and Burroughs’ homosexuality/bisexuality.

By the end of the 1950s, Kerouac and his friends lived in San Francisco, where morals were looser. In California the modern sound was fed by Gerry Mulligan and Chet Baker, who managed an original style, named “cool jazz.” Alternating words and saxophone phrases in American Haikus, Kerouac was trying to place his poems on the same level as musicians’ improvisations. To him, his words had come up spontaneously and were analogous to music improvisation.

BEAT

Referring to stallholders’ hardships, the term “beat” came from circus and carnival slang. Chatting with John Clellon Holmes, Kerouac suggested “we could say we’re a beat generation.” To him, losing a battle was necessary to qualify for a new consciousness, which then lead to a better approach to life — and making a new start. The term “beat” also means “rhythm.” Kerouac used it that way in one of his most significant recordings, drawing the “beat” meaning closer to “rhythm” as well as “beatitude” (supreme blessedness):

Everything is going to the beat

It’s the beat generation

It’s be-at [“bay-at”]

It’s the beat to keep

It’s the beat of the heart

It’s being beat

And down in the world

And like all-time low down

And like an ancient civilization

The slaves’ boatmen rowing alleys to a beat

And servants spinning pottery to a beat”

— Jack Kerouac, San Francisco Scene

(The Beat Generation), 1960

Allen Ginsberg’s father, Louis, was a Jewish poet teaching English in college; Allen’s mother, Naomi, suffered acute paranoia attacks, causing destabilisation in the family. As can be easily understood, the 1939 Soviet-Nazi pact had intensified anticommunism in the U.S., which declared war on Japan (after Pearl Harbor, December 1941), Germany, Italy and implicitly on Soviet Union. The USSR then became an ally of America, as Hitler had invaded it in June, 1941. Nevertheless, Naomi Ginsberg attended far left meetings, including of the American Communist Party, where she took her son several times during the actual war, which, to say the least, was a very subversive practice. She spent the best part of fifteen years in a mental institution, an ordeal for her son, who wrote for her Kaddish, one of his most famous poems.

The Beat movement was just elaborating when Japan surrendered in August of 1945, following the atom bomb destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki — and as the USSR conquered Eastern Europe. The Beat Generation took root in the ensuing USA - USSR cold war. It grew during the Korean war (June 1950 - July 1953), a country coveted and armed by Mao’s communist China and the USSR — just like Vietnam, which would also be embroiled in a civil war started in 1955, and lasting twenty years.

After the postwar reconstruction years, which were lead by President Harry Truman, nationalism and religion did well under General Dwight Eisenhower’s conservative presidency (1953-1961). Following over twenty years of economic disaster, world war and privation, once the wars were over American youth was finally free from its military duties and yearned for freedom of morals and the spirit, which all seemed out of reach in the 1950s.

It is in a consumerist and reactionary context that the Beat Generation pioneers rejected traditional values and created a dropout, antimilitarist, radical underground culture in their Greenwich Village, 11th Street apartment in New York. In the United States, this period was sullied by racism, antisemitism and anticommunist repression, which inclu-ded several outlawed practices, such as blacklisting (the 1950-1957 McCarthy era). As acts of protest, Orson Welles, Charlie Chaplin and Bertolt Brecht left the country.

ON THE ROAD

In 1945, Nat “King” Cole’s Route 66 was a hit song (composer Bobby Troup’s rare version is also included here). It was also a forerunner of On the Road’s success. Back from a long, initial haul through the USA along with his lover, Neal Cassady, it is in April of 1951 that Kerouac wrote the essay that would make him famous. Written on benzedrine, the book was rejected by several publishers because of its disjointed style and risqué content. It was Faulkner’s publisher, writer Malcolm Crowley, who finally published it six years later. Crowley had also popularised the term “lost generation” coined by Gertrude Stein, which referred to WWI. Ginsberg, Burroughs, Corso and Huncke had already published controversial texts dealing with society’s outcasts in an explicit way when staunch Catholic of French descent Jack Kerouac hit an unlikely, instant fame following the publication of On the Road on September 5, 1957.

Largely autobiographical, his short story narrates the long trip through the USA of two drug-loving, libertine friends (only one of them a homosexual) in search of God. Ginsberg and Cassady are widely mentioned, as well as Kerouac himself, under pseudonyms6. Jack Kerouac was abruptly celebrated as the leader of a new literary movement. His poet and writer friends also enjoyed popularity, which was as sudden as it was unexpected. Space conquest took off with a trip of another kind, the sputnik placed in orbit on October 4, 1957, at exactly the same time as the Beat Generation was aborning.

The Beats’ impact was immense all over America. They were in phase with the folk music revival (represented here by Dave Van Ronk and Bob Dylan) as well as the upward trend of rock ‘n’ roll, which finally hit its stride with a White audience (heard here in beatnik satire fashion on Kookie’s Mad Pad, from 1959). As the dawn of the 1960s found its way out of square darkness, the Beats were a driving force behind the cultural upheavals that began to be felt around the world. This set aims at supplying sound references covering the different sides of this important movement: poetry, spoken word (the oddball Lord Buckley, here in a delirious portrait of Jesus Christ, and the daring, controversial Lenny Bruce, both of whose careers were broken by the establishment), music, and comments, such as Jack Kerouac’s in Is There a Beat Generation?

LITERATURE

In 1944, Jean Cocteau reader Burroughs was the older of the three. He gave Ginsberg a copy of Yeats’ A Vision and to Kerouac he handed Oswald Spengler’s The Decline of the West. Spengler’s text left a deep mark on both; his depiction of a Western world in ruins made way for a new humanist culture, a philosophical utopia where non-censored art played a major part in politics.

For the twelve years preceding Kerouac’s success, the three main Beat Generation writers had come up with poems and novels suggesting a sense of out-of-bounds freedom, including sexual freedom and not excluding homosexual and interracial sex at a time when racial segregation, prudishness and heterosexuality were the norm. McCarthyism violently fought homosexuality, which was illegal, and which led to suicides, etc.

Burroughs was going through psychoanalysis with one of Sigmund Freud’s colleagues. He was trying to become a psychoanalyst himself and tested his skills on both Ginsberg and Kerouac. Burroughs was impervious to a conformist way of life and values. He got himself addicted to morphine, which Herbert Huncke had introduced him to in 1945. A former private detective who’d rubbed shoulders with the underworld, he collected and used firearms obsessively. In 1946 Burroughs moved to West 115th Street in New York, with his wife-to-be Joan, who he accidentally killed in 1951 while playing William Tell.

The Beats described experiencing hard drugs, including heroin, which was illegal (William Burroughs, Junkie, 1953), alcohol and amphetamine (legal then). This type of drug experience was shared by many jazz and blues musicians such as Ray Charles and Charlie Parker. Ginsberg and Kerouac were both showing interest in foreign cultures and had gotten into Asian spirituality. They still travelled a lot and turned to Buddhism in 1954. In brief they expressed their need to go through out-of-bounds experiences, as their avant-garde predecessors had done before them.

Arthur Rimbaud, Paul Verlaine, Oscar Wilde and Walt Whitman were also homosexual or bisexual, just as Burroughs, Kerouac, Ginsberg, Cassady and Orlovsky were. The Beats were also influenced by James Joyce and his spontaneous writing style, used in ‘Ulysses,’ as well as avant-garde poets, including William Carlos Williams (Ginsberg’s mentor was from Paterson, New Jersey — like Ginsberg himself), Emily Dickinson, W. H. Auden, e. e. cummings and Walt Whitman. They had read William Blake (adored by Ginsberg), Thomas Mann, Thomas Wolfe, John Dos Passos, Jack Black, Ezra Pound, Marcel Proust, Albert Camus, André Gide, Louis-Ferdinand Céline, André Breton and Franz Kafka.

After several setbacks and a detox, Burroughs moved to Tangiers (Morocco) in 1954. That is where he wrote Naked Lunch, over four years, under the influence of hashish, opiates and his friend Bryon Gysin, who introduced him to random cut up and collage techniques. The book was completed at the cheap “Beat Hotel” on 9 Rue Gît-le-Cœur in Paris’ latin quarter, where Ginsberg wrote part of his major works Kaddish and Corso wrote his poem “Bomb.” Random collage of words and rhymes was pioneered by surrealist artist Tristan Tzara and made famous by Burroughs (in the early 1970s, David Bowie wrote some songs this way). It was also used by Ginsberg in “Kaddish.”

Beat Generation literature has explored and influenced American literature by rejecting standard narration modes. Like André Breton before them, Kerouac, Cassady and Ginsberg used writing methods favouring spontaneity, as summed up in their “First thought, best thought” motto. This approach was later used by Bob Dylan and John Lennon, whose songs shook the world.

BEATNIKS

On the Road was published in 1957 and Kerouac’s success was immediate, thanks to a great review in the New York Times. His Beat Generation friends were now part of a celebrated literary movement, and publishers competed to publish their work. After years of obscurity, poverty, controversy, lawsuits for obscenity (Howl) and more infringements of moral values, the success of the Beat Generation marked the start of a press campaign presenting Kerouac as the spokesperson for his generation.

America was discovering counterculture and beat stereotypes were highlighted and mocked by the media. Clothing stereotypes (such as tights and ballet flats for ladies, beard, long hair, sandals and berets for gents) and “young” phrases caught on: “crazy”, “goof”, “dig”, “pad”, “square”, “hip”, “hipster”, “cool”, “a drag”, “visions” and “knockin’ some z’s” (sleeping). Pastiches and sarcasm resulted in humourous songs like the compelling Phillipa Fallon’s High School Drag (about boredom), The Beat Generation (fittingly plagiarized by punk rocker Richard Hell in 1977 as “The Blank Generation”) and Kookie’s Mad Pad. To be or not to be cool was now a beat matter, ridiculed in But I Was Cool by author and singer Oscar Brown, Jr. and humorists like Del Close and John Brent (who was also a beat poet) in Cool and Uncool (1959).