- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

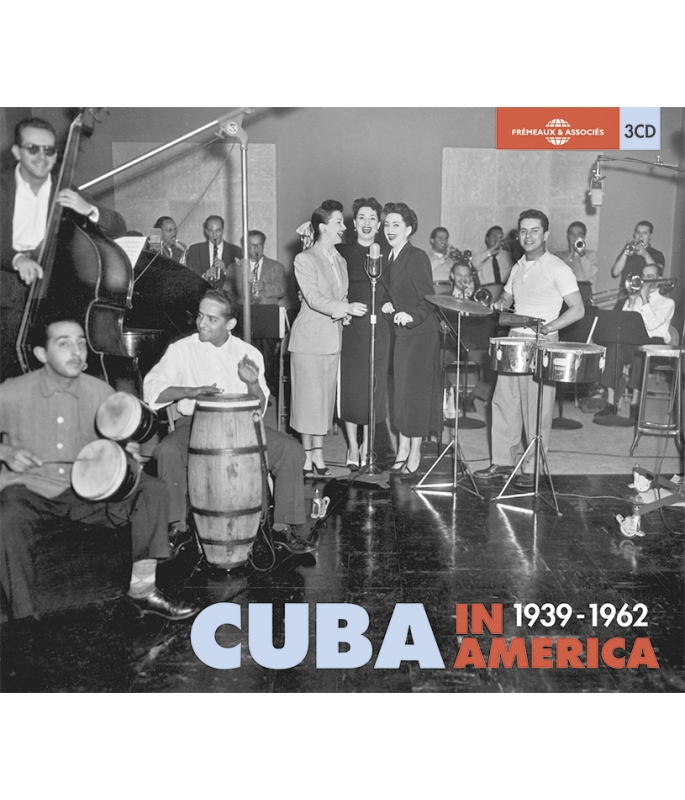

DIZZY GILLESPIE • TITO PUENTE • CAL TJADER • MACHITO • PROFESSOR LONGHAIR…

Ref.: FA5648

Artistic Direction : BRUNO BLUM

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Total duration of the pack : 3 hours 27 minutes

Nbre. CD : 3

DIZZY GILLESPIE • TITO PUENTE • CAL TJADER • MACHITO • PROFESSOR LONGHAIR…

DIZZY GILLESPIE • TITO PUENTE • CAL TJADER • MACHITO • PROFESSOR LONGHAIR…

For over a century, American musicians were exposed to Cuban rhythms and melodies. In assimilating them they created a very infl uential, new Latin-American sound. This compendium shows how blues, rock and jazz were deeply affected by the golden age of the rumba, son, bolero and mambo styles, which were all in vogue in North America before the Cuban revolution — when people could still freely circulate between the two countries. The USA also left its mark on Cuban musicians of the diaspora, many of which are included here. Bruno Blum has hand-picked these American recordings and explains in detail this compelling, founding Cuba/USA musical fusion in a 28-page booklet. Patrick FRÉMEAUX

CUBA 1929-1937

NEW-YORK, LOS ANGELES, MEXICO CITY, LA HAVANE

ROCK JAZZ & CALYPSO 1920 - 1962

ANTHOLOGIE 1923 - 1995

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Conga BravaDuke Ellington00:03:021940

-

2Elube ChangoXavier CugatAlberto Rivera00:03:221940

-

3Moon Over CubaDuke Ellington00:03:131941

-

4De Laff's On YouLouis JordanW. Wilson00:02:531942

-

5The Peanut VendorStan KentonSimons Moises00:04:361947

-

6Rhumba AzulNat King ColeNat King Cole00:02:351947

-

7Rumba en SwingChano PozoChano Pozo00:02:391947

-

8MantecaDizzy GillespieChano Pozo00:03:091947

-

9Mango MangueCharlie ParkerChucho Valdes00:02:581948

-

10St. Louis BluesMachito00:02:451949

-

11Push-Ka-Pee She PieLouis JordanWilloughby00:02:361949

-

12Longhair's Blues-RhumbaProfessor LonghairProfessor Longhair00:03:231949

-

13Bongo CitoSlim GaillardSlim Gaillard00:02:491949

-

14Tin Tin DeoDizzy GillespieChano Pozo00:02:441951

-

15Yo Yo YoSlim GaillardSlim Gaillard00:02:491951

-

16EstrellitaCharlie ParkerA. Venosa00:02:491952

-

17My Baby's GoneThe Ray-O-VacsB.B. King00:02:181951

-

18Cuban NightingaleBilly TaylorRogelio Martinez00:03:031952

-

19I Come From JamaicaChris PowellChris Powell00:02:391952

-

20Jock-A-Mo Iko IkoJames CrawfordJames Crawford00:02:311953

-

21Mishugana MamboSlim GaillardSlim Gaillard00:02:231953

-

22Woke Up This MorningB.B. KingB.B. King00:02:561952

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1BabaluSlim GaillardSlim Gaillard00:03:381951

-

2Soony-RoonySlim GaillardSlim Gaillard00:02:071951

-

3Mambo BoogieJohnny OtisJohnny Otis00:02:441951

-

4Mambo BounceSonny RollinsSonny Rollins00:02:251951

-

5TitoroBilly TaylorBilly Taylor00:03:051952

-

6Eee Ooo VoodooRed CallenderInconnu00:02:401954

-

7Hound DogBig Mama ThorntonJerry Leiber00:02:521952

-

8Mambo GarnerErroll GarnerErroll Garner00:06:361954

-

9Mambocito MioIllinois JacquetIllinois Jacquet00:02:551954

-

10Mambo HopOscar SaldanaO. Valle00:02:161954

-

11She Wants To MamboThe ChantersG. Ford00:02:531954

-

12Ran Kan KanTito PuenteTito Puente00:03:121955

-

13Stranded In The JungleThe JayhawksJimmy Johnson00:02:581956

-

14Cubano ChantArt Blakey Percussion EnsembleRay Bryant00:03:591957

-

15Mambo At The MCal TjaderLuis Kant00:04:421957

-

16For You My LovePaul GaytenPaul Gayten00:02:281957

-

17Dearest DarlingBo DiddleyBo Diddley00:02:531958

-

18TequilaChuck RioChuck Rio00:02:141957

-

19Arabian Love CallArt NevilleAlonzo White00:02:261958

-

20Peanut Vendor 2Red TylerMoises Simons00:02:051959

-

21Mambo de CucoMongo SanramariaNicholas Martinez00:03:551959

-

22What'D I SayRay CharlesRay Charles00:06:291959

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1The CraveJelly Roll MortonJelly Roll Morton00:03:121939

-

2Early In The MorningLouis JordanL. Hickman00:03:231947

-

3FiestaCharlie ParkerTraditionnel00:02:531951

-

4Cu-BlueBilly TaylorBilly Taylor00:02:491951

-

5Un Poquito De Tu AmorCharlie ParkerTraditionnel00:02:441951

-

6Cuba DollLloyd GlennGlenn Lloyd00:02:341952

-

7SummertimeRed SaundersGeorge Gershwin00:02:361953

-

8Fool BurroMabel ScottD. Williams Jr00:02:521953

-

9Relax And MamboMachitoMachito00:03:131953

-

10It Ain'T Necessarily SoCal TjaderGeorge Gerschwin00:02:061956

-

11South Parkway MamboBop A LoosCollins00:02:441955

-

12Why Don'T You Do RightJoe LocoJoe Mccoy00:02:391954

-

13Old Devil MoonMickey BakerLane Burton00:02:291955

-

14Spanish GuitarBo DiddleyBo Diddley00:04:141955

-

15Havana MoonChuck BerryChuck Berry00:03:081956

-

16La Guera BailaStan KentonJohnny Richards00:05:091956

-

17Quiet VillageMartin DennyDenny Martin00:03:411956

-

18I'Ve Waited So LongEddie CochranLordan Jeremiah Patrick00:02:411958

-

19Out Of NowhereCal TjaderJohnny Green00:03:291958

-

20Summertime 2Gene VincentHeyward Dubose00:03:001960

-

21BluesongoSonny RollinsSonny Rollins00:04:441962

-

22Dem TambourinesDon WilkersonDon Wilkerson00:05:351962

Cuba in America FA5648

Cuba in America

1939-1962

Pendant plus d’un siècle, les musiciens américains ont été exposés aux mélodies et rythmes cubains. En les assimilant ils ont créé un son latino-américain nouveau et très influent. Ce florilège montre comment le blues, le rock et le jazz ont été profondément marqués par l’âge d’or des styles rumba, son, boléro et mambo en vogue en Amérique du Nord, avant la révolution cubaine — quand les populations circulaient encore librement entre les deux pays. Des Cubains de la diaspora marqués par les États-Unis sont aussi représentés ici. Bruno Blum a réuni ces irrésistibles enregistrements américains et détaille cette fusion musicale Cuba/USA fondatrice dans un livret de 28 pages.

Patrick FRÉMEAUX

For over a century, American musicians were exposed to Cuban rhythms and melodies. In assimilating them they created a very influential, new Latin-American sound. This compendium shows how blues, rock and jazz were deeply affected by the golden age of the rumba, son, bolero and mambo styles, which were all in vogue in North America before the Cuban revolution — when people could still freely circulate between the two countries. The USA also left its mark on Cuban musicians of the diaspora, many of which are included here. Bruno Blum has hand-picked these American recordings and explains in detail this compelling, founding Cuba/USA musical fusion in a 28-page booklet.

Patrick FRÉMEAUX

Disc 1 - RUMBA IN SWING 1940-1953

1. CONGA BRAVA - Duke Ellington 3’00

2. ELUBE CHANGO - Xavier Cugat 3’20

3. MOON OVER CUBA - Duke Ellington 3’11

4. DE LAFF’S ON YOU - Louis Jordan 2’51

5. THE PEANUT VENDOR - Stan Kenton 4’35

6. RHUMBA AZUL - Nat “King” Cole 2’33

7. RUMBA EN SWING - Chano Pozo 2’38

8. MANTECA - Dizzy Gillespie 3’07

9. MANGO MANGUE - Charlie Parker 2’57

10. ST. LOUIS BLUES - Machito 2’43

11. PUSH-KA-PEE SHE PIE - Louis Jordan 2’34

12. LONGHAIR’S BLUES-RHUMBA - Professor Longhair 3’21

13. BONGO CITO - Slim Gaillard 2’47

14. TIN TIN DEO - Dizzy Gillespie 2’43

15. YO YO YO - Slim Gaillard 2’47

16. ESTRELLITA - Charlie Parker 2’48

17. MY BABY’S GONE - The Ray-O-Vacs 2’16

18. CUBAN NIGHTINGALE - Billy Taylor 3’01

19. I COME FROM JAMAICA - Chris Powell 2’37

20. JOCK-A-MO [Iko Iko]Sugar Boy Crawford 2’29

21. MISHUGANA MAMBO - Slim Gaillard 2’22

22. WOKE UP THIS MORNING - B. B. King 2’57

Disc 2 - MAMBO IN AMERICA [uptempo] 1951-1959

1. BABALU - Slim Gaillard 3’36

2. SOONY-ROONY - Slim Gaillard 2’06

3. MAMBO BOOGIE - Johnny Otis 2’42

4. MAMBO BOUNCE - Sonny Rollins 2’24

5. TITORO - Billy Taylor 3’03

6. EEE OOO VOODOO - Red Callender 2’38

7. HOUND DOG - Big Mama Thornton 2’50

8. MAMBO GARNER - Errol Garner 6’34

9. MAMBOCITO MIO - Illinois Jacquet 2’54

10. MAMBO HOP - Oscar Saldana 2’15

11. SHE WANTS TO MAMBO - The Chanters 2’51

12. RAN KAN KAN - Tito Puente 3’11

13. STRANDED IN THE JUNGLE - The Jayhawks 2’56

14. CUBANO CHANT - Art Blakey Percussion Ensemble 3’57

15. MAMBO AT THE M - Cal Tjader 4’41

16. FOR YOU MY LOVE - Paul Gayten 2’26

17. DEAREST DARLING - Bo Diddley 2’51

18. TEQUILA - The Champs 2’12

19. ARABIAN LOVE CALL - Art Neville 2’24

20. PEANUT VENDOR - Alvin “Red” Tyler & the Gyros 2’04

21. MAMBO DE CUCO - Mongo Santamaría 3’53

22. WHAT’D I SAY - Ray Charles 6’30

Disc 3 - SUMMERTIME IN HAVANA-

ON-THE-HUDSON [mid and slow tempo] 1939-1962

1. THE CRAVE - Jelly Roll Morton 3’11

2. EARLY IN THE MORNING - Louis Jordan 3’22

3. FIESTA - Charlie Parker 2’51

4. CU-BLUE - Billy Taylor 2’47

5. UN POQUITO DE TU AMOR - Charlie Parker 2’42

6. CUBA DOLL - Lloyd Glenn 2’33

7. SUMMERTIME - Red Saunders 2’34

8. FOOL BURRO - Mable Scott 2’50

9. RELAX AND MAMBO - Machito 3’11

10. IT AIN’T NECESSARILY SO - Cal Tjader 2’04

11. SOUTH PARKWAY MAMBO - Bop-A-Loos 2’42

12. WHY DON’T YOU DO RIGHT - Joe Loco 2’37

13. OLD DEVIL MOON - Mickey Baker 2’27

14. SPANISH GUITAR - Bo Diddley 4’13

15. HAVANA MOON - Chuck Berry 3’06

16. LA GUERA BAILA - Stan Kenton 5’07

17. QUIET VILLAGE - Martin Denny 3’39

18. I’VE WAITED SO LONG - Eddie Cochran 2’39

19. OUT OF NOWHERE - Cal Tjader 3’27

20. SUMMERTIME - Gene Vincent 2’58

21. BLUESONGO - Sonny Rollins 4’43

22. DEM TAMBOURINES - Don Wilkerson 5’35

Cuba in America

Blues, Habanera, Swing, Rumba, Rock, Mambo & Jazz 1939-1962

Par Bruno Blum

Autour de la Seconde Guerre Mondiale le développement de l’industrie du disque et de la radio a permis, pour la première fois, d’avoir accès à des musiques provenant de pays différents. Dès les années 1930, des enregistrements cubains ont circulé et marqué les musiciens d’Amérique et d’ailleurs. Ils contenaient des rythmes appelés habanera, boléro, rumba, son et d’autre encore. Ces créations caribéennes plongeaient leurs racines en Afrique et étaient parfois issues de musiques rituelles animistes cubaines dont Mongo Santamaría et Chano Pozo, qui s’installèrent à New York dans l’après-guerre, étaient des maîtres. Ces musiques avaient connu un grand succès à la fin du dix-neuvième siècle. On retrouve la habanera de jadis à la racine de nombreuses musiques caribéennes dominantes et cubaines en particulier. Un aperçu des meilleurs disques anciens est disponible dans Cuba 1923-1995 et Cuba - Bal à La Havane 1926-1937 dans cette collection. Située en plein milieu du XXe siècle, la période 1939-1962 présentée ici correspond à ce que l’on pourrait appeler la naissance du concept de « world music » à une époque où l’ouverture aux cultures et musiques étrangères — particulièrement du sud — était encore marginale. Fondamentalement, l’intégration des musiques cubaines aux États-Unis s’est d’abord faite par le biais du jazz. Les musiciens afro-américains sentaient et comprenaient que leur culture partageait une proximité, une fraternité, une créolité essentielle avec celle de la rumba, du son, puis du mambo, etc.

Cuba a été l’un des premiers pays dont les disques ont marqué directement et profondément la musique du continent nord-américain. Ils se sont ajoutés à l’influence ancestrale des cultures bantoues du bassin du Congo, des musiques d’Afrique de l’Ouest, d’Europe occidentale (Portugal, Espagne, France, Grande-Bretagne, Irlande, musiques juives, etc.), des musiques créoles de Haïti, de la Jamaïque, des musiciens du Mexique, de Hawaï1 et Trinité-et-Tobago2. L’influence cubaine a été considérable. On la retrouve dans le jazz hot « New Orleans » des années 1920, puis dans le swing, le jazz moderne, différentes formes de blues, mais aussi dans le mento et le jazz jamaïcain3, le calypso trinidadien et le rock. Des artistes aussi importants et divers que Charlie Parker, Eddie Cochran, Professor Longhair, Errol Garner, Art Neville, Gene Vincent, Dizzy Gillespie ou Ray Charles ont enregistré des rythmes cubains. Des classiques de la musique américaine aussi variés que St. Louis Blues par Louis Armstrong (1929), The Crave de Jelly Roll Morton (1939) ou « Twenty Flight Rock » d’Eddie Cochran (1959) sont basés sur un rythme habanera ; Le « Apache » des Shadows (Angleterre) est un boléro cubain (distinct du boléro espagnol dérivé de la habanera), tout comme What’d I Say, l’un des plus grand succès de Ray Charles, et le classique Hound Dog de Big Mama Thornton. « Hound Dog » est un blues très dansant ; de façon caractéristique, il était une tentative de capter un public sensible à la mode cubaine d’actualité en 1953. Il n’en est pas moins devenu l’un des morceaux fondateurs du rock.

Les musiques caribéennes syncopées — et cubaines en particulier — sont aussi à la racine du funk, comme le montre l’anthologie Roots of Funk 1947-1962 dans cette collection. Cette sélection Cuba in America 1939-1962 donne ici une idée d’une large influence des musiques cubaines sur les musiciens enregistrés aux États-Unis au crucial milieu du vingtième siècle. Le premier disque fait un tour d’horizon de la période de la guerre à l’après-guerre ; le disque 2 couvre les années 1950 sur un tempo rapide ; le disque 3 installe une ambiance détendue, plus tranquille — évoquant un été dans le quartier cubain de New York. La prise du pouvoir par Fidel Castro en 1959 a provoqué la fuite vers les États-Unis d’un grand nombre de musiciens cubains, dont la vedette Celia Cruz et une enfant nommée Gloria Estefan ; de nouvelles musiques fécondes allaient surgir de la diaspora cubaine des États-Unis, influençant par exemple Sonny Rollins, dont la création Bluesongo de 1962 basée sur un boléro emporte déjà l’auditeur vers une musique au rythme hybride nouveau. Mais l’histoire de la fusion musicale Cuba-USA avait commencé bien plus tôt.

NEW ORLEANS

Cuba est la plus grande île des Caraïbes, située à cent quarante kilomètres au sud des côtes américaines de Floride (Keys). Découverte par Christophe Colomb en 1492, Cuba était au dix-neuvième siècle une colonie espagnole produisant de grandes quantités de canne à sucre. Nombre d’Africains avaient été capturés, déportés et forcés à travailler sur les plantations jusqu’à l’abolition de l’esclavage, intervenue tardivement en 1886 (colonies anglaises : 1838; françaises, 1848). L’histoire de l’émigration cubaine vers le continent a commencé dès 1565 avec une colonie de soldats hispano-cubains fondée à St. Augustine en Floride. Les apports cubains dans la culture américaine n’ont plus cessé depuis. À partir de 1800 environ un nombre conséquent de planteurs cubains a émigré sur le continent avec ses esclaves. La musique des captifs n’était pas autant réprimée dans les colonies catholiques comme Cuba et Haïti (de nombreux esclaves haïtiens avaient d’ailleurs été emmenés travailler à Cuba) que sur le continent. Ceci a permis une transmission musicale afro-créole significative de Haïti et Cuba à la Nouvelle-Orléans, grand port d’accès au Mississippi et enclave catholique franco-espagnole sur le continent. La Havane est à 1078 km de la Nouvelle-Orléans ; Beaucoup d’Afro-cubains se sont intégrés en Louisiane même, où ils ont répandu le danzón, les rythmes habanera et rumba que leurs ancêtres ont certainement joués le dimanche à Congo Square4. Leurs aïeux y avaient aussi diffusé la culture animiste évoquée ici par Xavier Cugat dans Elube Changó (Changó est le dieu du tonnerre des Yorubas), sorti en face B de « Zombie », et par Red Callender dans Eee Ooo Voodoo. La reprise délirante de Babalú, un classique cubain adapté ici en scat/glossolalie par Slim Gaillard, est une invocation à la divinité de la santería Babalu Ayé. La présence du vaudou et des rites animistes caribéens dans les musiques populaires nord-américaines est l’objet d’un coffret dans cette collection, Voodoo in America 1926-1961. C’est principalement à partir de la Louisiane et du Mississippi qu’une diffusion de ces cultures caribéennes a eu lieu vers le nord.

L’Espagne a perdu sa colonie cubaine au terme d’une longue guerre d’indépendance — et ce largement à la suite d’une intervention militaire des États-Unis. Une fois débarrassés des Espagnols en 1899, les Américains ont fait de Cuba un protectorat, un satellite, une colonie avec laquelle existaient d’importants liens commerciaux : sucre, tabac, nickel… dès lors, la présence ancestrale de mélodies et rythmes cubains a plus encore marqué le grand port de la Nouvelle Orléans, comme en attestent plusieurs enregistrements de jazz importants et influents; Enregistré par des Cubains dès 19315, le grand classique de W.C. Handy « St. Louis Blues » n’est pas le seul à avoir été basé sur un rythme habanera. La version incluse ici est une interprétation du Cubain new yorkais Machito, qui dirigeait le meilleur orchestre cubain des États-Unis dans l’après-guerre. Les grands musiciens de la Nouvelle-Orléans Jelly Roll Morton (The Crave, 1939), Professor Longhair (Longhair’s Blues-Rhumba, 1949) et Art Neville (Arabian Love Call, 1958) montrent ici que cette influence fondamentale est restée constante jusqu’à la fin des années 1950 (elle a continué ensuite). Les rythmes et arrangements cubains syncopés ont d’ailleurs influencé les musiciens fondateurs du funk comme les Meters d’Art Neville6. Dans les années 1950, le mambo marquera à son tour la Nouvelle Orléans (Paul Gayten, For You my Love). Cuba a aussi influencé le rock de Louisiane, comme par exemple Fats Domino ou ici Sugar Boy Crawford, auteur du classique Jock-o-Mo basé sur un mystérieux vocabulaire de bonne année entendu dans les carnavals de la ville.

DE LA RUMBA DANS LE SWING

Tout au long du vingtième siècle, la misère a accablé les populations rurales cubaines majoritairement noires, qui étaient souvent exploitées par les descendants des Espagnols et leurs partenaires américains. Grâce au commerce avec l’étranger, une partie des villes connaissait néanmoins un développement record pour une région des Caraïbes : santé, éducation, automobile, etc. La musique tenait une place importante dans la vie quotidienne. Distinct de la habanera, le rythme de la rumba est souvent identifiable par son rythme de tibois (la clave, deux morceaux de bois frappés l’un contre l’autre comme dans l’intro de Arabian Love Call d’Art Neville, le titre de Professor Longhair, ou deux de Louis Jordan : Early in the Morning et le calypso arrangé en rumba Push-Ka-Pee She Pie). En jouant à la guitare ce rythme habituellement interprété sur les percussions du tibois, Bo Diddley a créé son style à Chicago, l’influent Bo Diddley beat (ici dans une variation improvisée, Spanish Guitar) en 19557.

Les différentes formes de musique populaire cubaine appartenaient à une riche tradition (danzón, charanga, guaracha, son, son montuno, rumba, boléro, etc). Les percussions rituelles (santería, abakuà, orishas yorubas et une présence animiste bantoue, akan, etc.) se superposaient aux chants d’église catholiques, aux influences espagnole, mexicaine, dominicaines, haïtiennes, portoricaines, sud et nord-américaines. Dans les années 1930, les orchestres de jazz proliféraient dans l’île. Ils jouaient initialement des rythmes américains puis ont incorporé des rythmes locaux tout en conservant la sophistication des arrangements à l’américaine. L’orchestre de Hermanos Castro a été fondé en 1929. Citons aussi ceux de Hermanos Palao, René Touzet, Armando Romeu et Casino de la Playa avec la voix de Miguelito Valdés en 19378.

Des disques de variété rumba et d’autres musiques des Caraïbes ont commencé à être diffusés aux États-Unis dans les années 1930, inspirant des artistes américains. Après les enregistrements pionniers du genre par Duke Ellington en 1931-359, des adaptations ont eu lieu en Europe. La rumba évoquait alors l’exotisme, la fête, la chaleur, la séduction et donna lieu à des chansons françaises osées (écouter l’exquis Amour, bananes et ananas 1932-1950 dans cette collection). Dans un des premiers films parlants en 1936, on pouvait admirer la grande vedette Tino Rossi chanter les vertus de la rumba, style exotique — donc supposé propice à la romance —, au son d’un rythme rumba noyé dans les violons de son grand succès « Marinella ». La rumba cubaine est ainsi parvenue en Afrique francophone (son rythme revenait à sa source dans la région du Congo Brazzaville) où elle a inspiré un nouveau style, la rumba congolaise. Arrivés ensuite, les véritables enregistrements cubains du Trio Matamoros et Septeno Habanera ont décuplé cette influente fusion musicale qui a fait danser tout le continent à partir des années 1940 (pour se métamorphoser finalement en soukous et en ndombolo congolais, encore plus populaires). Avec les indispensables Cab Calloway et Louis Jordan, et notamment influencé par son tromboniste portoricain Juan Tizol (compositeur de « Caravan »), Duke Ellington a été l’un des premiers à assimiler une influence rumba dans son génial orchestre de jazz (« The Peanut Vendor » dès 1931 et ici Conga Brava et Moon Over Cuba, co-signés avec Tizol en 1940-41). Parallèlement, la demande d’exotisme a permis le développement de grands orchestres de variété comme celui de Xavier Cugat, un Américain blanc d’origine espagnole et cubaine dont le répertoire dansant mélangeait des succès de différentes musiques afro-latines. Comme le faisait Glenn Miller dans le style swing à la même époque, le son de Cugat utilisait les arrangements sophistiqués d’un orchestre cossu, conçu pour la danse et laissant peu de place à l’improvisation. C’est sa version de la chanson mexicaine « Perfidia » qui l’a rendu célèbre en 1940 — année de la sortie de son Elube Changó.

À partir de la fin de la Seconde Guerre Mondiale, le tourisme a commencé à se développer à Cuba comme dans le reste des îles voisines : Îles Vierges, Jamaïque, Saint Domingue, Porto Rico, Haïti, Trinité-et-Tobago, Bermudes, Bahamas, etc. Les touristes aimaient acheter des disques de musique locale, qu’ils rapportaient chez eux en souvenir et l’industrie du disque s’est intéressée aux Caraïbes10. Les grandes villes cubaines — et La Havane en particulier — ont été comparées à Las Vegas : casinos, prostitution, alcool, orchestres de qualité et bourgeoisie cohabitaient avec une pauvreté endémique. Les mouvements révolutionnaires s’organisaient ; et de plus en plus de Cubains tentaient leur chance à Miami et New York.

CUBOP

Dans l’après-guerre, la radio a décuplé l’attrait des nouvelles musiques cubaines enregistrées. Les disques provenaient surtout de la marque cubaine indépendante Panart qui dominait le marché du disque local. Le chanteur et joueur de maracas Machito avait grandi à Cuba puis fondé son orchestre à New York en 1940, vite rejoint par son beau-frère l’influent trompettiste Mario Bauza, avec qui il entreprit la fusion jazz/musiques cubaines avec la rigueur des orchestres américains. Leur « Tanga » fondateur de 1948 peut être écouté sur Mambo Big Bands 1946-1957, The Beat Generation 1936-1962 et Roots of Funk 1947-1962 dans cette collection. Machito était très marqué par le jazz, qu’il influença à son tour. Puis le jazz afro-cubain influencera fortement la naissance du mambo en 1949. Mais c’est le succès d’une version de Peanut Vendor (1947), un son interpété par l’orchestre éclectique de Stan Kenton qui a véritablement donné le signal de départ de la mode cubaine. Dès lors, les enregistrements américains marqués par Cuba se sont multipliés, tels le Rhumba Azul de Nat « King » Cole (1947) et le « Ah Cubanas » (1950) de Dave Bartholomew à la Nouvelle Orléans. Quelques grands joueurs de congas cubains exilés à New York, dont Chano Pozo (écouter son boléro Rumba en swing) et bientôt Mongo Santamaría ont alors initié des jazzmen de la nouvelle génération d’après-guerre aux rythmes de leur pays. Le jazz moderne be bop commençait à connaître un certain succès. Un de ses fers de lance, le trompettiste virtuose Dizzy Gillespie avait compris sous l’influence de Mario Bauza (qui lui avait obtenu un des ses premiers jobs chez Cab Calloway en 1939) que Cuba détenait un héritage musical proche de l’Afrique : une identité en phase avec la quête des boppers. Dizzy a soudain fondé avec Chano Pozo un orchestre de jazz afro-cubain unique en son genre (Manteca, 1947) qui enregistra jusqu’en 1949 et concurrençait les orchestres cubains de ses amis Machito et du New Yorkais d’origine portoricaine Tito Puente. Le chanteur, guitariste et pianiste excentrique Slim Gaillard adopta les rythmes cubains dès 1949, gravant Bongo Cito, suivi par Babalú, Yo Yo Yo et Soony-Roony en 1951, puis Mishugana Mambo. Une fois la mode mambo installée en 49, leurs amis Sonny Rollins (Mambo Bounce) et Charlie Parker (Fiesta, Un Poquito de Tu Amor, Estrellita) ont eux aussi gravé des disques afro-cubains ; à partir de 1950 Bird a enregistré directement avec l’excellent orchestre new-yorkais de Machito (ici Mango Mangue) dont les disques comptent parmi les meilleurs du genre. Collaborateur oublié de Dizzy Gillespie, Stan Getz et Ben Webster, le pianiste Billy Taylor brille ici avec ses titres Cu-Blue, Cuban Nightingale et Titoro de 1951-1952. Après le meurtre de Chano Pozo le 3 décembre 1948, Gillespie a continué à interpréter des compositions cubaines, comme ici le Tin Tin Deo de Pozo. Cette histoire ne faisait que commencer.

MAMBO IN AMERICA

Le mambo tire son nom du mot « mère » (nana) et « esprit » (bo) en langue fon (Bénin actuel), soit littéralement « mère des esprits ». À Haïti, pays voisin de Cuba, les grandes prêtresses du vaudou et guérisseuses portent le nom de mambo (les grands prêtres sont appelés houngans, dont l’étymologie est également fon). À Cuba, « mambo » signifiait initialement la deuxième partie d’un morceau de danse, où la frénésie musicale combinait des motifs répétitifs entraînants (vents), propices à insuffler un état qui — proche de la transe des rites animistes locaux où l’on retrouvait les mêmes rythmes — permettait le contact avec les esprits des ancêtres. La séquence « mambo » succédait à un chant ou une improvisation (première partie) précédés par une introduction. Cette structure est analogue à celle du merengue dominicain hispanophone voisin, où la « deuxième partie » frénétique s’appelait le jaleo (raffut). Le merengue a connu le succès aux États-Unis à partir de 1950. Le merengue dominicain s’est mélangé au jazz dans le même esprit que les musiques afro-cubaines ; complémentaire au volume Haiti - Meringue & Konpa 1952-1962, le coffret Dominican Republic - Merengue 1949-1962 lui est consacré dans cette collection. Quand ses rythmes spécifiques ont fusionné avec le mambo aux États-Unis en 1960, le merengue est devenu la pachanga, un nouveau style dont Mambo de Cuco de Mongo Santamaría donne un aperçu virtuose. Ces musiques évolueront ensuite vers la salsa, musique de la communauté latine de New York.

Aux États-Unis le terme générique « rumba » désignait souvent l’ensemble des musiques latines de l’époque. Comme pour le blues, le jazz, le rock et autres musiques noires « de rythme », les noms des styles et des rythmes différents étaient mélangés et indistincts11. Ils ont été considérés plus ou moins interchangeables jusqu’à l’irruption en 1949 du nouveau genre mambo, qui lança instantanément une mode cubaine de grande envergure. Cette musique dansante, moderne et efficace, créée par Pérez Prado, un Cubain installé à Mexico, était marquée par les innovations et le professionnalisme des grands orchestres de jazz américains (héritage de Duke Ellingon, Cab Calloway, Dizzy Gillespie, Machito, Stan Kenton, etc.). Apportant un son nouveau, la vague mambo a achevé d’imposer la présence cubaine dans les musiques occidentales. Des orchestres cubains comme La Sonora Matancera accompagnaient différents artistes talentueux, qui répondaient à la demande d’une clientèle urbaine aisée à La Havane. Ils se déplaçaient en tournée dans les pays latins et leurs disques avaient du succès. La chanteuse Celia Cruz les a rejoints en 1950 et a encore élargi leur impact. Le percussionniste new-yorkais d’origine portoricaine Tito Puente a été l’un des premiers à former un orchestre de mambo aux États-Unis, publiant ses premiers succès en 49. Son Ran Kan Kan de 1958 reste un sommet du genre — bien qu’il fût joué par un groupe new-yorkais. D’autres musiciens d’origine latine ont enregistré des disques dans des styles cubains ; parmi eux, le pianiste d’origine portoricaine de Machito, Joe Loco (Why Don’t You Do Right) et Don Tosti, qui était d’origine mexicaine. Mongo Santamaría, un maître cubain des congas, est arrivé à New York en 1950. Il a participé à plusieurs enregistrements inclus ici, notamment avec Cal Tjader, un vibraphoniste américain blanc souvent accompagné par des musiciens cubains de premier plan (Mambo at the M, It Ain’t Necessarily So, Out of Nowhere). Avec ses versions cubaines de compositions américaines Tjader a réussi plusieurs splendides albums qui firent de lui la plus grande vedette non-latine de la musique cubaine. Mongo Santamaría est aussi représenté ici par sa fabuleuse pachanga Mambo de Chuco, où figure un violon (héritage des groupes traditionnels charanga).

CU-BLUE

Comme on l’a vu plus haut, des artistes de jazz comme Louis Jordan avaient incorporé des rythmes cubains dans leurs arrangements. Certains de ces titres jazz étaient de simples blues, comme le splendide Cu-Blue de Billy Taylor, Rhumba Azul de Nat « King » Cole ou le délicieux Mambo Garner, un festin pianistique du grand Errol Garner. Des artistes de blues comme Professor Longhair à la Nouvelle-Orléans ou le saxophoniste « honk » Illinois Jacquet (Mambocito Mio) ont aussi enregistré des rythmes cubains ; à Los Angeles Lloyd Glenn (pianiste de T-Bone Walker et Lowell Fulson, ici sur son propre Cuba Doll) et bien d’autres comme la chanteuse Camille Howard (« Shrinking Up Fast » et « Within This Heart of Mine ») ont gravé des blues en mode cubain.

Idem pour le sextet du grand contrebassiste Red Callender avec l’envoûtant Eee Ooo Voodoo12 dont la rythmique (basse et batterie) ressemble à celle de Hound Dog, le célèbre morceau de Big Mama Thornton dont Elvis Presley ferait l’un de ses plus grands succès rock quelques années plus tard en utilisant un riff habanera de base. Avec la brûlante partie de guitare de Pete Lewis et la voix ‘shout’ de Big Mama, « Hound Dog » reste un sommet de la fusion blues/rumba. Johnny Otis, dont le fameux orchestre a enregistré l’exquis Mambo Boogie inclus ici, joue de la batterie sur « Hound Dog », qu’il a aussi arrangé, co-écrit et produit (avant de perdre ses droits dans un litige l’opposant aux compositeurs Mike Leiber et Jerry Leiber). À la suite de ce succès majeur, d’autres chanteuses ont sorti des disques de « blues cubain », dont Mable Scott avec Fool Burro ou Gloria Irving avec « I Need a Man ». Les Chanters ont enregistré She Wants to Mambo en 1954 avec la voix suggestive de la chanteuse Ethel Brown. Le géant du blues B. B. King, qui commençait à toucher un large public en 1953, a comme T-Bone Walker en 1947 (« Plain Old Down Home Blues ») adopté l’alternance de rythmes habanera/boléro et rock pour son Woke Up This Morning. Ce morceau de B. B. King est sans doute à l’origine d’un classique du rock basé sur un boléro, le « Susie Q » de Dale Hawkins avec James Burton à la guitare, dont la partie de guitare lui ressemble beaucoup13. Le South Parkway Mambo de Bop-A-Loos est encore un blues, mais avec cette forte présence du rythme boléro très proche de la habanera ancestrale — avec en plus la cloche sur tous les temps, un trait caractéristique du cha cha chá cubain à la mode en 1955. Ce disque a eu du succès en Jamaïque, où il a contribué à la vague de blues local14. D’autres musiciens de la sphère blues et rock comme Bo Diddley à Chicago (Spanish Guitar) et à New York le grand guitariste Mickey Baker (Old Devil Moon) ex-Mickey & Sylvia, ont réussi à faire le lien entre la grande tradition de la guitare espagnole, le nouveau son de la guitare électrique de l’époque et les rythmes afro-cubains.

CUBA ROCKS

Comme le montre Mambo Boogie de Johnny Otis en 1951, le rock s’est nourri très tôt des musiques cubaines. En 1952, Chris Powell enregistrait I Come From Jamaica sur une base de habanera suractivée, paru sur l’étiquette Spanish Town. Le grand trompettiste de hard bop Clifford Brown y emmène le groupe dans les hauteurs d’un instant de grâce avec un fulgurant solo, son tout premier enregistrement. Le Dearest Darling (1958) de Bo Diddley est dérivé du mambo ; on retrouve la pulsion rythmique particulière de ce tempo rapide dans For You my Love de Paul Gayten (1957) à la Nouvelle Orléans. Ce rythme s’imposera l’année suivante dans Tequila, le numéro un américain des Champs, un groupe de rock blanc. Comme T-Bone Walker et B. B. King, les Jayhawks alternaient couplet habanera et refrain rock, comme ici dans la version originale de Stranded in the Jungle (un futur succès des Cadets et plus tard des New York Dolls). À la Nouvelle-Orléans, Sugar Boy Crawford mélangea avec naturel le rock originel et le boléro dans son mystique Jock-O-Mo qui monterait au n°20 en 1965 sous le nom de « Iko Iko » par les Dixie Cups15. Tandis que les cadors de la guitare rock comme Mickey Baker et Bo Diddley s’essayaient aux improvisations hispanisantes, le géant du rock Chuck Berry enregistrait le tranquille boléro Havana Moon (dérivé du « Calypso Blues » de Nat « King » Cole), un bijou atypique qui révélait une forte présence latine chez lui, déjà esquissée par son tout premier enregistrement en tant que guitariste pour un disque obscur de Joe Alexander and The Cubans16. Eddie Cochran, un autre rockeur célèbre, choisit lui aussi un boléro pour crooner I’ve Waited So Long dans la tradition des chanteurs de charme latins, tout comme son ami Gene Vincent dans une version exceptionnelle du Summertime de George Gerschwin17. Ces trois derniers titres figurent sur le disque 3, plus calme. Avec son intro de tibois (clave) rumba, Arabian Love Call par Art Neville est une autre perle du genre rock afro-cubain, interprétée ici par l’un des futurs fondateurs du funk (une décennie plus tard). Mais le plus célèbre classique du rock propulsé par un rythme cubain (un boléro caractéristique, où la partie de congas est jouée sur une batterie) est sans doute le What’d I Say de Ray Charles, un blues accéléré enregistré en 1959, peu après la révolution, au moment où des milliers de Cubains rejoignaient les États-Unis pour éviter d’être spoliés par le nouvel état communiste soutenu par l’U. R. S. S.

SUMMERTIME IN HAVANA ON THE HUDSON

D’autres musiques latines encore avaient percé dans le paysage musical américain au début des années 1950 : la samba brésilienne, le merengue dominicain18, la plena portoricaine, quelques succès mexicains, etc. Mais les rythmes et mélodies cubaines ont eu un impact sans égal, qui a pénétré le répertoire des plus grands artistes des États-Unis. À partir du milieu de la décennie la mode du cha cha chá 19, un dérivé du mambo, a encore élargi le succès de la musique cubaine. En 1958-59 l’émigration due à la révolution est devenue une hémorragie. La communauté cubaine de New York était implantée à Hudson County, face à Manhattan, sur la rive ouest de l’Hudson. Situé près du tunnel Lincoln qui relia Manhattan au New Jersey en 1937, on appelait ce quartier Havana on the Hudson. On pouvait y acheter des disques cubains pour l’été, parler espagnol et trouver des produits des Caraïbes. Loin de l’agitation des pistes de danse, le disque 3 de cette anthologie évoque la nonchalance ensoleillée, la douceur « lounge » et l’érotisme que cette musique pouvait également porter.

Cette fantaisie tropicale — ou peut-être ce fantasme — s’est matérialisé avec l’album évocateur Exotica de Martin Denny, qui fonda le courant « exotica » en 1957. Denny jouait initialement dans les bars du circuit touristique de Honolulu où l’on pouvait entendre les grenouilles-taureaux réagir à la musique. Les musiciens imitaient aussi les cris d’oiseau et cette couleur sauvage animalière a été incorporée à leur son nouveau, une musique d’ambiance détendue proche de la musique de film. Avant de devenir l’autre grand nom du style exotica visant à capter l’atmosphère de Hawaï, Arthur Lyman joua du vibraphone sur cet album fondateur sans prétention ethnologique, puisqu’en dépit d’une image tournée vers Honolulu c’est bien une sorte de habanera cubaine mutante qui rythme Quiet Village, un des grands succès américains de 1957. Avec des pochettes de disques fantasmagoriques mettant en scène le mannequin Sandy Warner, Martin Denny et Arthur Lyman ont créé un univers, une bande son où l’esthétique, le climat propice à l’érotisme tranchait avec le puritanisme des années Eisenhower. Conçue comme un décor musical de carton-pâte, cette musique était très évocatrice. Elle était aussi inspirée par des enregistrements plus authentiques, comme ceux de Cal Tjader, qui employait de grands musiciens cubains. Cal Tjader a réussi quelques chefs-d’œuvre du genre, comme ici Mambo at the M sur un tempo rapide ; mais l’essence de son style est sans doute à chercher du côté de ses interprétations très détendues de classiques américains arrangés sur un rythme habanera. Avec son vibraphone envoûtant (et la contribution du grand saxophoniste José « Chombo » Silva sur Out of Nowhere), un titre comme It Ain’t Necessarily So n’a rien à envier à la magie des plus grands enregistrements cubains. Il n’en est pas moins américain. L’influence cubaine était installée et, comme d’autres sources venues des Caraïbes, elle imprègne fortement la musique des États-Unis dont elle fait désormais entièrement partie, comme l’explicite ici Dem Tambourines de Don Wilkerson en 1962.

Bruno Blum, février 2016

Merci à Stéphane Colin, Christophe Hénault, Gilles Riberolles, Maya Roy, Frédéric Saffar & Ned Sublette.

© FRÉMEAUX & ASSOCIÉS 2016

1. Lire les livrets et écouter Hawaiians in Paris 1916-1926 (FA 066) et Hawaiian Music 1927-1944 (FA 035) dans cette collection.

2. Lire le livret et écouter Trinidad - Calypso 1939-1959 (FA 5348) et, pour le calypso étranger à la Trinité, Anthologie des Musiques de Danse du Monde, volume Calypso (FA 5342).

3. Lire le livret et écouter Jamaica Jazz 1931-1962 (FA 5636) et Jamaica - Mento 1951-1958 (FA 5275) dans cette collection.

4. Ned Sublette, The World That Made New Orleans, From Spanish Silver to Congo Square (Chicago, Lawrence Hill Books, 2008) et Freddi Williams Evans, Congo Square (New Orleans, University of Louisiana at Lafayette Press, 2010. Édition française : Paris, La Tour Verte, 2012).

5. Lire le livret et écouter Roots of Mambo 1930-1950 (FA 5128) dans cette collection.

6. Lire le livret et écouter Roots of Funk 1947-1962 (FA 5498) dans cette collection.

7. Lire le livret et écouter The Indispensable Bo Diddley 1955-1960 (FA 5376) et Volume 2 1959-1962 (FA 5406) dans cette collection.

8. Maya Roy, Musiques Cubaines, Actes Sud/Cité de la Musique, 1998. Édition anglaise : Cuban Music (Latin America Bureau, Londres, 2002).

9. Lire le livret et écouter Roots of Mambo 1930-1950 (FA 5128) dans cette collection.

10. Lire les livrets et écouter Virgin Islands 1956-1960 (FA 5403), Jamaica - Mento 1951-1958 (FA 5175), Haiti - Meringue & Konpa 1952-1962 (FA 5615), Dominican Republic - Merengue 1949-1962 (FA 5450), Trinidad - Calypso 1939- 1959 (FA 5348), Bermuda - Gombey & Calypso 1953-1960 (FA 5374) et Bahamas - Goombay 1951-1959 (FA 5302) dans cette collection.

11. Lire le livret et écouter Race Records - Black Rock Music Forbidden on U.S. Radio 1942-1955 (FA 5600) dans cette collection.

12. Retrouvez d’autres titres de vaudou et hoodoo américains sur Voodoo in America 1926-1961 (FA 5375) dans cette collection.

13. Lire le livret et écouter Electric Guitar Story 1935-1962 (FA 5421) dans cette collection.

14. Lire le livret et écouter Jamaica - Rhythm and Blues 1956-1961 (FA 5358) dans cette collection.

15. Écouter aussi Ayiko Ayiko par Art Blakey & the Afro-Drum Ensemble, inclus dans Africa in America 1920-1962 (FA 5397) dans cette collection.

16. Un titre de Chuck Berry accompagnant Joe Alexander and the Cubans, extrait du single I Hope These Words Will Find You Well/Oh Maria (1954) est inclus dans The Indispensable Chuck Berry 1954-1961 (FA 5461) dans cette collection.

17. Écouter aussi The Indispensable Eddie Cochran 1955-1960 (FA 5425) The Indispensable Gene Vincent 1956-1958 (FA 5402) et vol. 2 1958-1962 (FA 5422) dans cette collection.

18. Lire le livret et écouter Dominican Republic Merengue 1949-1962 (FA 5450) dans cette collection.

19. Lire le livret et écouter Cha-Cha-Cha 1953-1958 (FA 5342) dans la série Anthologie des Musiques de Danse du Monde.

Cuba in America

Blues, Habanera, Swing, Rumba, Rock, Mambo & Jazz 1939-1962

By Bruno Blum

Around World War II, the development of the record industry and the radio gave access, for the first time, to musics coming from various countries. As early as the 1930s, Cuban recordings circulated and influenced musicians from North America and elsewhere. They contained rhythms called habanera, bolero, rumba, son and others. These Caribbean creations traced their roots from Africa. They were also sometimes derived from Cuban animist musics, mastered by Mongo Santamaría and Chano Pozo, who moved to New York in the post-war years. Cuban music had been very successful at the end of the Nineteenth Century. Old time habanera can be found at the root of many dominant Caribbean musics — and Cuban ones in particular. For a good insight into these early recordings, some of the best ones are available on Cuba 1923-1995 and Cuba - Bal à La Havane 1926-1937, in this series. The 1939-1962 period presented here is from the core, the middle period of the Twentieth Century. It coincides with what could be called the birth of “world music,” a new concept for a time when open-mindedness towards foreign cultures and musics was still marginal. Fundamentally, the integration of Cuban musics in the United States first happened through jazz. African-American musicians felt and understood that their culture shared a closeness, a brotherhood and an essential creole dimension with that of the rumba, son, and later the mambo, etc.

Cuban records were among the first foreign ones to have a direct impact and leave a deep mark on North American music. They added to the ancestral influence of Bantu cultures from the Congo basin, West Africa and western Europe (Portugal, Spain, France, Great Britain, Ireland, Jewish music, etc.), creole music from Haiti, Jamaica and musicians from Mexico and Hawaii1, as well as Trinidad-and-Tobago2.

The Cuban influence was considerable. It can be traced all the way back to 1920s New Orleans hot jazz, followed by swing, modern jazz and various forms of blues, as well as Jamaican mento and jazz3, Trinidadian calypso, and rock.

Important and diverse artists such as Charlie Parker, Eddie Cochran, Professor Longhair, Errol Garner, Art Neville, Gene Vincent, Dizzy Gillespie and Ray Charles all recorded Cuban rhythms. Classic American tunes as varied as Louis Armstrong’s version of St. Louis Blues (1929), Jelly Roll Morton’s The Crave (1939) or Eddie Cochran’s “Twenty Flight Rock” (1959) are based on a habanera rhythm. The Shadows’ “Apache” (England) is a Cuban bolero (distinct from Spanish bolero, which was derived from habanera), and so were Ray Charles’ great What’d I Say hit and Big Mama Thornton’s classic Hound Dog. “Hound Dog” is a very danceable blues; it was a typical attempt to reach a Cuba-loving audience, as Cuban music was fashionable in 1953. It nevertheless remains one major, founding rock and roll song.

Syncopated Caribbean musics — especially Cuban ones — are also found at the true root of funk, as shown in our Roots of Funk 1947-1962 anthology in this series. This selection here, Cuba in America 1939-1962, shows a wide scope of Cuban musical influence on U. S. recordings made in the crucial mid-Twentieth Century. The first disc gives an overview of the World War II and postwar periods. Disc two covers the 1950s, at a fast tempo; Disc three instils a more relaxed mood, reminiscent of what summertime in New York’s Cuban neighborhood might have sounded like at the time.

When Fidel Castro took power in 1959, a great number of Cuban musicians fled to the United States, including star Celia Cruz and a child named Gloria Estefan. New, fecund music would surge out of the Cuban diaspora in the USA, influencing the likes of Sonny Rollins, whose bolero-based Bluesongo, 1962 creation was already leading the listener towards a new, hybrid, creative rhythm music. But the story of the Cuba-USA musical fusion had started way before this.

NEW ORLEANS

Cuba is the biggest island in the Caribbean, some eighty-six miles south of US shores (the Florida Keys archipelago). Cuba was discovered by Christopher Columbus in 1492, before it became a Spanish colony producing great quan‑tities of sugarcane. A great number of Africans had been captured, deported from their African homelands and forced to work on plantations, up until the belated abolition of slavery in 1886 (British colonies: 1838; French: 1848).

The history of Cubans migrating to the American continent had started as early as 1565, when a colony of Spanish-Cuban soldiers was founded in St. Augustine, Florida; Cuban input in American culture has not ceased ever since. As from around 1800, a sizeable amount of Cuban planters migrated to the continent with their slaves. Unlike the prevailing ways on the continent, the captives’ music was not as harshly repressed in Catholic colonies such as Cuba and Haiti (many Haitian slaves had also been taken to Cuba to work there). This enabled a significant afro-creole musical transmission from Haiti and Cuba to the great port of New Orleans, the gateway to the Mississippi and a French/Spanish, catholic enclave on the continent.

Havana is only 670 miles away from New Orleans and many Afro-Cubans integrated in Louisiana. Their ancestors very likely played danzón, habanera and rumba rhythms at Sunday gatherings on Congo Square in New Orleans, where they became part of the culture4. Their forebears had also spread animist culture, alluded to here by Xavier Cugat on Elube Changó (Changó is the Yoruba God of Thunder), which was released with a tune called “Zombie” on the B-side, and by Red Callender on Eee Ooo Voodoo. The delirious version of Cuban classic Babalú, adapted here in scat/speaking in tongues style by Slim Gaillard, is an invocation to santería divinity Babalu Ayé.

The presence of Voodoo and Caribbean animist rites in North-American pop music is the subject of the Voodoo in America 1926-1961 set in this series; Caribbean cultures spread out northbound, mainly from Louisiana and the Mississippi delta.

Spain lost its Cuban colony at the end of a long war of independance — largely thanks to a US military intervention. Once rid of the Spanish in 1899, the USA turned Cuba into a protectorate, a satellite, a colony used for trade: sugar, tobacco and nickel.

The ancestral presence of Cuban melodies and rhythms left an even deeper mark on the port of New Orleans, as several important, influential jazz recordings show. W. C. Handy’s great “St. Louis Blues” classic is not the only one based on a habanera rhythm. The rendition included here is by New York’s own Machito, who led the best Cuban orchestra in the USA in the postwar years.

Fine New Orleans musicians such as Jelly Roll Morton (The Crave, 1939), Professor Longhair (Longhair’s Blues-Rumba, 1949) and Art Neville (Arabian Love Call, 1958) show that until the end of the 1950s, this fundamental influence remained a steady contributor. It carried on afterwards. Syncopated Cuban rhythms and arrangements, by the way, also influenced funk founders, such as Art Neville’s Meters5. In the 1950s, mambo also hit New Orleans (Paul Gayten’s For You My Love). Cuba left its mark on Louisiana’s rock musicians as well, including Fats Domino and Sugar Boy Crawford, who penned his Jock-o-Mo classic using some mysterious new year celebrations vocabulary heard in local carnivals.

RUMBA IN SWING

All through the Twentieth Century, poverty plagued the country dwellers, who were mostly Black — and were still often exploited by Spanish descendants and their American partners. Thanks to foreign trade, some parts of the cities nevertheless thrived on a record-breaking development for the Caribbean: health care, education, cars, etc. Music played an important part in everyday life.

Distinct from habanera, the rumba rhythm is often easy to spot, with its clave sound (two bits of wood banged against one another) as in Art Neville’s Arabian Love Call, Professor Longhair’s tune here and two more by Louis Jordan: Early in the Morning and a calypso with a rumba arrangement, Push-Ka-Pee She Pie. By playing this clave percussion rhythm on the guitar, Bo Diddley created his own style in Chicago, the influential Bo Diddley beat (heard here in an improvised variation named Spanish Guitar) in 19556.

Different forms of popular local musics belonged to a rich tradition (danzón, charanga, guaracha, son, son montuno, rumba, bolero, etc). Ritual percussions (santería, abakuà, yoruba orishas, Akan and Bantu animist presence, etc.) were superimposed on Catholic church songs, along with Spanish, Mexican, Dominican, Haitian, Puerto Rican, South and North American influences. By the 1930s, jazz orchestras proliferated on the island. They initially played US rhythms, then incorporated local rhythms while keeping the sophistication of American arrangements. Hermanos Castro’s orchestra was founded in 1929. Mention can also be made of Hermanos Palao, René Touzet, Armando Romeu and, by 1937, Casino de la Playa with the voice of Miguelito Valdés7.

In the 1930s, commercial rumba records and other Caribbean musics began to circulate in the United States, inspiring American artists. After a few landmark recordings by Duke Ellington were released in 1931-358, some European musicians also began adapting Cuban rhythms. Rumba was synonymous with exoticism, a party atmosphere, heat and seduction. It gave rise to risqué French songs (listen to the exquisite Amour, bananes et ananas 1932-1950 set in this series). In one of the first talking films of 1936, one could admire French star Tino Rossi singing the virtues of rumba, an exotic style — therefore favourable to romance — to the sound of a rumba rhythm drowned in schmaltzy violins, resulting in his big “Marinella” hit record.

Cuban rumba thus reached French-speaking Africa (its rhythm was returning to square one in the Congo Brazzaville area) where it inspired a new style, the Congolese rumba. Soon true Cuban recordings by Trio Matamoros and Septeno Habanera reached Congo, increasing an influential musical fusion that had the entire continent dancing by the 1940s (and which finally metamorphosed into the even more popular Congolese sukus and ndombolo).

Along with the indispensable Cab Calloway and Louis Jordan, Duke Ellington’s brilliant, creative jazz orchestra was one of the first to assimilate the rumba influence, with the help of his Puerto Rican trombone player, Juan Tizol (who wrote “Caravan”), recording “The Peanut Vendor” as early as 1931, then Conga Brava and Moon Over Cuba in 1940-41, both of which were co-authored with Tizol and are included here.

Simultaneously, the demand for exoticism allowed commercial orchestras such as Xavier Cugat’s — a White American of Spanish and Cuban origins — to thrive on a hodgepodge of Latin-American hits. As Glenn Miller did with the swing style around the same time, Cugat’s sound used sophisticated arrangements in a well-heeled orchestra that was conceived for dancing and left little room for improvisation. His version of the Mexican song “Perfidia” rose him to fame in 1940 — the same year as Elube Changó, which is included here.

Tourism started developing after World War II. It grew in Cuba, as it did in nearby islands: Jamaica, the Dominican Republic, Virgin Islands, Puerto Rico, Haiti, Trinidad-and-Tobago, Bermuda, Bahamas, etc. Tourists liked buying local music records, which they took home as souvenirs. The record industry suddenly got interested in Caribbean music9. Great Cuban cities — Havana in particular — were compared to Las Vegas: casinos, prostitution, alcohol, quality orchestras and wealthy people coexisted with endemic poverty.

Meanwhile, revolutionary movements were getting organised; and more and more Cubans were emigrating and trying their luck in Miami and New York.

CUBOP

In the post-war years, radio helped in building the attraction and popularity of these new, recorded Cuban musics. Records mostly came from the independent Cuban label Panart, which dominated the local market.

Singer and maracas player Machito had grown up in Cuba. He moved to New York City in 1940 and founded his own orchestra, soon to be joined by the influential trombonist Mario Bauza, who was also his brother-in-law. Together they set about creating a jazz/Cuban music fusion, using the rigor of a professional American orchestra. Their founding “Tanga” from 1948 can be found on Mambo Big Bands 1946-1957 as well as The Beat Generation 1936-1962 and Roots of Funk 1947-1962 in this series.

Machito was very much influenced by jazz, which he influenced in turn. This Afro-Cuban jazz would then strongly influence the birth of mambo in 1949. However, Cuban music fashion really started with the success of yet another Peanut Vendor version, a son recorded in 1947 by Stan Kenton’s eclectic orchestra. Cuba-influenced American recordings such as Nat “King” Cole’s Rhumba Azul or Dave Bartholomew’s “Ah Cubanas” in New Orleans then multiplied. A few great Cuban conga players had become exiled in New York, among them Chano Pozo (hear his Rumba en Swing bolero) and Mongo Santamaría. They turned jazzmen of the new, post-war generation onto their homeland’s rhythms.

Be bop/modern jazz was just taking off then. Under the influence of Mario Bauza, trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie (Bauza had gotten him his first break in Cab Calloway’s orchestra back in 1939), one of its spearheads, understood that Cuba possessed a musical legacy close to that of Africa, an identity in tune with the boppers’ quest. Dizzy suddenly formed a one-of-a-kind Afro-Cuban orchestra with Chano Pozo (Manteca, 1947), which recorded until late 1948.

By so doing he began competing with his friends Machito and New Yorker of Puerto Rican origin Tito Puente. In turn, eccentric singer, piano and guitar player Slim Gaillard adopted Cuban rhythms as early as 1949, cutting Bongo Cito, then Babalú, Yo Yo Yo and Soony-Roony in 1951, then Mishugana Mambo.

Once the mambo trend hit its stride in 1949, their friends Sonny Rollins (Mambo Bounce) and Charlie Parker (Fiesta, Un Poquito de Tu Amor, Estrellita) started recording Afro-Cuban music, too. As from 1950, Bird recorded directly with Machito’s excellent orchestra (represented here with Mango Mangue), issuing some of the best records of the kind. A forgotten, former Dizzy Gillespie, Stan Getz and Ben Webster band-mate, pianist Billy Taylor shines on with his Cu-Blue, Cuban Nightingale et Titoro solo efforts from 1951-1952. Following the murder of Chano Pozo on December 3, 1948, Gillespie kept playing Cuban compositions, such as Pozo’s Tin Tin Deo. The story had just begun.

MAMBO IN AMERICA

Mambo took its name from the fon words “mother” (nana) and “spirit” (bo), literally meaning “mother of the spirits” (in present day Benin). In Cuba’s nearest neighbour, Haiti, vodou high priestesses and healers are called mambos (and high priests are called houngans, which has a fon etymology as well). In Cuba, ‘mambo’ also meant the second part of a dance number, where musical frenzy combined with compelling, repetitive riffs (horns) likely to induce a state of body and soul similar to local animist ritual trances, where the same rhythms could be heard, and where the spirits of the ancestors could contact and ‘ride’ the chosen, practicing believers.

The ‘mambo’ part came after a vocal section (part one), itself preceded by a short introduction. This structure is analogous to nearby Dominican merengue’s, which was also sung in Spanish, and where the exciting ‘part two’ trance-like section was called jaleo (racket). As from 1950, and at the same time as mambo, Dominican merengue became popular in the United States.

It fused with jazz in pretty much the same way and same spirit as Afro-Cuban musics, as shown in the Dominican Republic - Merengue 1949-1962 set and the complementary Haiti - Meringue & Konpa 1952-1962 set, both available in this series. The specific merengue rhythms would eventually fuse with mambo in 1960, thus creating a new style called pachanga, as heard in Mongo Santamaría’s virtuoso Mambo de Cuco. These musics later evolved towards salsa, the latin community music in New York City.

Quite often, in the United States the generic term ‘rumba’ was really used to mean just any latin music. As for jazz, blues, rock and other Black ‘rhythm’ musics, different rhythms and style names were easily mixed up and hard to differentiate10. They were all pretty much interchangeable until mambo emerged in 1949, instantly launching a major Cuban trend.

This modern, danceable, efficient music was created by Pérez Prado, a Cuban musician who set up in Mexico City. Prado was influenced by the innovative music and professionalism of the great American jazz orchestras (the legacy of Duke Ellington, Cab Calloway, Dizzy Gillespie, Machito, Stan Kenton, etc.). The mambo wave brought along a new sound, and fully complemented the Cuban presence in the Western hemisphere.

Cuban orchestras, such as the Sonora Matancera, backed talented artists marketed for Havana’s urban, affluent patrons. They toured latin countries and their records sold well enough. Singer Celia Cruz joined them in 1950 and further widened their impact. A New York percussionist of Puerto Rican origin, Tito Puente was one of the first musicians to form a mambo orchestra in the United States, releasing his earliest hits in 1949. Although played by a New York group, his 1958 hit Ran Kan Kan will forever remain a peak in mambo history.

Other musicians of latin origin recorded Cuban-styled music. Among them, Machito’s pianist Joe Loco (Why Don’t You Do Right) who was of Puerto Rican origin, and Don Tosti, of Mexican descent. Emigrating to New York in 1950, Mongo Santamaría was a Cuban conga master who contributed to several recordings here, including Mambo at the M, It Ain’t Necessarily So and Out of Nowhere by Cal Tjader, a White American vibes player who often set up sessions with top Cuban musicians. Tjader specialised in Cuban-styled arrangements of American compositions and succeeded in putting together several fine, popular albums that made him the biggest non-Cuban star in Cuban music. Mongo Santamaría can also be heard here on his own Mambo de Chuco, where the violin legacy of traditional charanga groups is featured.

CU-BLUE

As seen above, jazz artists such as Louis Jordan blended Cuban rhythms in their arrangements. Some of those jazz tunes were simply blues, i. e. Billy Taylor’s splendid Cu-Blue, Nat “King” Cole’s Rhumba Azul and the exquisite piano feast Mambo Garner by one of the all-time greats, Errol Garner. Blues artists such as Professor Longhair in New Orleans and “honk” sax player Illinois Jacquet (Mambocito Mio) also recorded Cuban rhythms. In Los Angeles, Lloyd Glenn (T-Bone Walker and Lowell Fulson’s piano player, represented here on Cuba Doll) and many others, including singer Camille Howard (“Shrinking Up Fast” and “Within This Heart of Mine”) cut some blues in the Cuban fashion.

The same goes with master acoustic bass player Red Callender’s spellbinding Eee Ooo Voodoo11, where the rhythm arrangement sounds similar to Big Mama Thornton’s famous Hound Dog. Elvis Presley would turn “Hound Dog” into one of his greatest rock hits a few years later, using a basic habanera beat. With Pete Lewis’ smoking hot guitar part and Big Mama’s ‘shout’ vocals, “Hound Dog” remains the ultimate blues/rumba fusion classic. Johnny Otis’ famous orchestra had recorded the exquisite Mambo Boogie included here; Otis also played the drums on “Hound Dog,” which he arranged, co-wrote and produced (before he lost his rights in a court case against composers Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller). Following this major success, other female blues singers had a go at Cuban blues, including Mable Scott, represented here on Fool Burro, and Gloria Irving with “I Need a Man.”

The Chanters recorded I Want to Mambo in 1954, featuring Ethel Brown’s suggestive voice. Blues giant B. B. King was just hitting his stride in 1953, and like T-Bone Walker before him (“Plain Old Down Home Blues,”1947), he chose to alternate the habanera/bolero rhythm and a rock beat on Woke Up This Morning. It is likely that this B. B. King tune was the template for another rock classic, Dale Hawkins’ “Susie Q,” on which James Burton’s guitar part sounds very similar to King’s12.

Bop-A-Loos’ South Parkway Mambo is yet another blues, this time emphasizing a bolero rhythm close to ancestral habanera — this time with a bell on every beat, a classic feature of Cuban cha cha chá, which had become fashionable in 1955. This record was successful in Jamaica, where it contributed to the local blues wave13. Musicians from the blues and rock scene also managed to link Afro-Cuban rhythms, the Spanish guitar tradition and the electric guitar, which was quite a new instrument then. These include Bo Diddley in Chicago (Spanish Guitar) and New York’s own, ex-Mickey & Sylvia’s fine guitar player, Mickey Baker (Old Devil Moon).

CUBA ROCKS

As Johnny Otis’ 1951 Mambo Boogie shows, rock fed itself with Cuban music at an early stage. In 1952, Chris Powell released the sped up, high-powered habanera of I Come From Jamaica on the Spanish Town label, with a contribution from legendary hard bop trumpet player Clifford Brown, who takes the group to unknown heights for a few seconds here — his first ever recording. Bo Diddley’s Dearest Darling (1958) is derived from mambo; the peculiar rhythmic pulse of his fast tempo can also be found on For You my Love by Paul Gayten (1957). This same rhythm would upsurge the following year on Tequila, a US number one for The Champs — a White rock group.

As T-Bone Walker and B. B. King had done before them, the Jayhawks alternated a habanera verse and a rock chorus on the original version of Stranded in the Jungle (later a hit song for The Cadets and The New York Dolls). In New Orleans, Sugar Boy Crawford spontaneously mixed original rock and bolero for his mystical Jock-O-Mo, which would eventually become a #20 hit for the Dixie Cups as “Iko Iko” in 196514.

While rock guitar experts like Mickey Baker and Bo Diddley attempted hispanic-styled improvisations, rock giant Chuck Berry recorded the sweet bolero Havana Moon (derived from Nat “King” Cole’s “Calypso Blues”), an atypical gem showing his ever-present taste for latin music, as previously outlined in his first ever recording as a session guitar player for an obscure record by Joe Alexander and The Cubans15.

Another famous rocker, Eddie Cochran, also chose to croon in the latin bolero tradition, resulting in I’ve Waited So Long. So did Cochran’s friend, Gene Vincent, in an exceptional rendition of George Gershwin’s Summertime16. These last three tracks are found on the quieter disc three.

With its rumba clave intro, Art Neville’s Arabian Love Call is another rock tune arranged in the Afro-Cuban style, this time sung by one of the founders (a decade later) of funk. However, the most famous of all Cuban rhythm-powered rock classics (here a typical bolero, with the conga part played on the drums) is no doubt Ray Charles’ classic What’d I Say. This sped-up blues was recorded in 1959 shortly after the Cuban revolution, at a time when thousands of Cubans fled to the United States to avoid dispossession by the new, Soviet-supported communist state.

SUMMERTIME IN HAVANA ON THE HUDSON

Other latin musics got a break in the US musical landscape of the early 1950s: Brazilian samba, Dominican merengue17, Puerto Rican plena, as well as a few Mexican hits, etc. But Cuban rhythms and melodies had a peerless impact when it came to penetrating some of the greatest US artists’ repertoires.

Breaking in the mid-1950s, the mambo-derived cha cha chá 18 opened up new markets. By 1958-1959, emigration due to the growing revolution became a haemorrhage. The New York Cuban community was based in Hudson County, facing Manhattan on the West bank of the Hudson River. Located near the Lincoln Tunnel, which linked Manhattan to New Jersey in 1937, this neighbourhood was called Havana-on-the-Hudson then. You could speak Spanish there, shop for some Cuban records for the summer and get hold of many Caribbean products. Far away from the dance hall needs, disc three of this anthology evokes the sunny “lounge” nonchalance, sweetness and eroticism that this music could also carry.

This tropical fantasia — or perhaps this fantasy — materialised with Martin Denny’s evocative Exotica album, which founded the “exotica” wave, in 1957. Denny initially played in the tourist circuit bars of Honolulu, where bull-frogs could be heard reacting to the music. The musicians also imitated bird calls and this wildlife flavour was incorporated in their new sound: a relaxed mood music analogous to film soundtrack. Before he became the other big name in the exotica genre, which aimed at capturing the Hawaii ambiance, Arthur Lyman played vibes on this founding album. One of the top-selling US albums of 1957, the record had no ethnologic pretention, because in spite of an image geared towards Honolulu, a sort of twisted Cuban bolero was used on Quiet Village.

Martin Denny and Arthur Lyman used phantasmagorical pictures, with model Sandy Warner, thus creating an artistic world, a soundtrack where aesthetics and an erotic climate offset the Eisenhower years’ puritanism. Conceived as some sort of a musical cardboard-cutout background, this music is quite evocative; it was also inspired by more authentic recordings, such as Cal Tjader’s, who used the best Cuban musicians available.

Tjader managed a few masterpieces of the genre, as heard here at a fast tempo on Mambo at the M. But the very essence of his style owes perhaps more to the relaxed renditions of certain American classics arranged on a habanera/bolero beat. With his enchanting vibraphone (and a contribution by great sax player José “Chombo” Silva on Out of Nowhere), the magic of his arrangement on It Ain’t Necessarily So sounds every bit as good as any first-class Cuban recording. The Cuban influence had come to stay, as for other Caribbean sources also, which strongly pervaded United States music and has ever since been an integral part of it, as heard explicitely on Don Wilkerson’s Dem Tambourines from 1962.

Bruno Blum, February, 2016

Thanks to Chris Carter for proofreading, Stéphane Colin, Christophe Hénault, Gilles Riberolles, Maya Roy, Frédéric Saffar & Ned Sublette.

© FRÉMEAUX & ASSOCIÉS 2016

1. Cf. Hawaiians in Paris 1916-1926 (FA 066) and Hawaiian Music 1927-1944 (FA 035).

2. Cf. Trinidad - Calypso 1939-1959 (FA 5348) in this series. For calypso foreign to Trinidad, cf. Anthologie des Musiques de Danse du Monde, volume Calypso (FA 5342).

3. Cf. Jamaica Jazz 1931-1962 (FA 5636) and Jamaica - Mento 1951-1958 (FA 5275) in this series.

4. Ned Sublette, The World That Made New Orleans, From Spanish Silver to Congo Square (Chicago, Lawrence Hill Books, 2008) and Freddi Williams Evans, Congo Square (New Orleans, University of Louisiana at Lafayette Press, 2010).

5. Cf. Roots of Funk 1947-1962 (FA 5498) in this series.

6. Cf. The Indispensable Bo Diddley 1955-1960 (FA 5376) and Volume 2 1959-1962 (FA 5406) in this series.

7. Maya Roy, Cuban Music (Latin America Bureau, London, 2002).

8. Cf. Roots of Mambo 1930-1950 (FA 5128) in this series.

9. Cf. Virgin Islands 1956-1960 (FA 5403), Jamaica - Mento 1951-1958 (FA 5175), Haiti - Meringue & Konpa 1952-1962 (FA 5615), Dominican Republic - Merengue 1949-1962 (FA 5450), Trinidad - Calypso 1939- 1959 (FA 5348), Bermuda - Goombey & Calypso 1953-1960 (FA 5374) and Bahamas - Goombay 1951-1959 (FA 5302) in this series.

10. Cf. Race Records - Black Rock Music Forbidden on U.S. Radio 1942-1955 (FA 5600) in this series.

11. Find more American voodoo and hoodoo songs on Voodoo in America 1926-1961 (FA 5375) in this series.

12. Cf. Electric Guitar Story 1935-1962 (FA 5421) in this series.

13. Cf. Jamaica - Rhythm and Blues 1956-1961 (FA 5358) in this series.

14. Listen also to Ayiko Ayiko by Art Blakey & the Afro-Drum Ensemble, on the Africa in America 1920-1962 (FA 5397) anthology in this series.

15. A 1954 song by Joe Alexander and the Cubans feat. Chuck Berry, taken from the single I Hope These Words Will Find You Well/Oh Maria, is available on The Indispensable Chuck Berry 1954-1961 (FA 5461) in this series.

16. Cf. The Indispensable Eddie Cochran 1955-1960 (FA 5425), The Indispensable Gene Vincent 1956-1958 (FA 5402) and vol. 2 1958-1962 (FA 5422) in this series.

17. Cf. Dominican Republic Merengue 1949-1962 (FA 5450) in this series.

18. Cf. Cha-Cha-Cha 1953-1958 (FA 5342) in the Anthologie des Musiques de Danse du Monde series.

Cuba in America

Blues, Habanera, Swing, Rumba, Rock, Mambo & Jazz 1939-1962

Disc 1 - RUMBA IN SWING 1940-1953

“That four-note habanera/tango rhythm is the signature Antillean beat to this day. It’s a simple figure that can generate a thousand dances all by itself […]. It’s the accompaniement figure to W. C. Handy’s “St. Louis Blues”, and you hear it from brass bands at a second line in New Orleans today. At half speed, with timpani or a drum set, it was the signature of Brill Building songwriters, and it was the basic template of clean-studio 1980s corporate rock.”

— Ned Sublette, The World That Made New Orleans, 2008, p. 124.

1. CONGA BRAVA - Duke Ellington and his Famous Orchestra

(Edward Kennedy Ellington aka Duke Ellington, Juan Tizol)

Rex William Stewart-cornet; Wallace Jones, Charles Melvin Williams as Cootie Williams-tp; Joe Nanton, Lawrence Brown-tb; Juan Tizol-vtb; Barney Bigard-cl; Johnny Hodges-as, ss, cl; Oto Hardwick-as, bs; Ben Webster-ts; Harry Carney-cl, as, bs; Edward Kennedy Ellington as Duke Ellington-p; Jimmy Blanton-b; Sonny Greer-d. Chicago, March 15, 1940.

2. ELUBE CHANGO - Xavier Cugat and his Waldorf-Astoria Orchestra

(Alberto Rivera)

Miguelito Valdés-v; Francisco de Asís Javier Cugat as Xavier Cugat-violin, leader; orchestra. Victor 26735B, matrix 55546. New York, August 27, 1940.

3. MOON OVER CUBA - Duke Ellington and his Famous Orchestra

(Edward Kennedy Ellington aka Duke Ellington, Juan Tizol)

Ivie Anderson, Herb Jeffries-v; Wallace Jones, Ray Willis Nance, Rex William Stewart-tp; Lawrence Brown, Joe Nanton aka Tricky Sam-tb; Juan Tizol-valve tb; Otto Hardwicke-cl, as; Johnny Hodges-as; Ben Webster-ts; Harry Carney, bs, as, cl; Barney Bigard-cl, ts; Edward Kennedy Ellington as Duke Ellington-p; Fred Guy-g; Jimmy Blanton-b; William Greer as Sonny Greer-d. RCA-Victor Vi 27587. Los Angeles, July 2, 1941.

4. DE LAFF’S ON YOU - Louis Jordan and his Tympany Five

(Wesley Wilson)

Louis Thomas Jordan as Louis Jordan -v, as, dir.; Eddie Roane-tp; Arnold Thomas-p; Dallas Bartley-sb; Walter Martin-d. Decca, 71134-A. New York, July 21, 1942.

5. THE PEANUT VENDOR [El Manisero] - Stan Kenton and his Orchestra

(Moisés Simón Rodríguez as Moisés Simons)

Milt Bernhart (solo), Bart Varsalon a, Eddie Bert, Harry Betts, Harry Forbes-tb; Stanley Newcomb Kenton as Stan Kenton-p, arr, dir; Laurindo Almeida-g; Eddie Safranski-b; Sheldon Manne as Shelly Manne-d; Frank Grillo aka Machito-mar; José Luis Mangual, Vidal Bolado-perc.; Jack Costanzo-bongos. Capitol CL 1306, CAP 2668. Hollywood, December 6, 1947.

6. RHUMBA AZUL - The King Cole Trio

(Nathaniel Adams Cole aka Nat “King” Cole)

Nathaniel Adams Cole as Nat “King” Cole-v, p; Oscar Moore-g; Johnny Miller-b. Capitol 10103. Radio Recorders, Hollywood, August 6, 1947.

7. RUMBA EN SWING - Chano Pozo

(Luciano Pozo Gonzales aka Chano Pozo)

Tito Rodriguez-v; The Machito Orchestra: Mario Bauza, Frank Davila as Paquito Davila, Jorge Lopez-tp; Jose Madera aka Pin-ts; Eugene Johnson-as; Ignacio Arsenio Travieso Scull as Arseno Rodríguez-tres (guitar); René Hernandez-p, arr.; Julio Andino-b; Luciano Pozo Gonzales as Chano Pozo-congas, vocal chorus; Carlo Vidalen-tumbadora (congas); José Mangual, Sr.-bongos; Ubaldo Nieto-timbales; others-vocal chorus. New York, February 7, 1947.

8. MANTECA - Dizzy Gillespie and his Orchestra

(John Birks Gillespie aka Dizzy Gillespie, Luciano Pozo Gonzales aka Chano Pozo)

Dizzy Gillespie-v, tp; Dave Burns, Benny Bailey, Elmon Wright, Lammar Wright, Jr.-tp; Ted Kelly, Bill Shepherd-tb; John Brown, Howard Johnson-as; Joe Gayles, George Nicholas aka Big Nick-ts; Cecil Payne-bs; John Collins-g; John Lewis-p; Al McKibbon-b; Kenny Clarke-d; Luciano Pozo Gonzales as Chano Pozo-congas. RCA Victor 20-3023 (D7-VB-3090-1). New York, December 30, 1947.

9. MANGO MANGUE - Charlie Parker and Machito and his Orchestra

(Jesús Valdés Rodríguez aka Chucho Valdés)

Mario Bauza, Frank Davila as Paquito Davila, Bobby Woodlen-tp; Charlie Parker-as; Gene Johnson, Freddie Skerritt-as; Jose Madera-ts; Leslie Johnakins-bs; René Hernandez-p; Roberto Rodriguez-b; José Manguel-bongos; Luis Miranda-congas; Ubaldo Nieto-timbales; Frank Grillo as Machito-maracas. Possibly Mercury Studios, New York, December 20, 1948.

10. ST. LOUIS BLUES - Machito and his Afro-Cuban Orchestra

(William Christopher Handy)

Personnel includes: Mario Bauza, Frank Davila as Paquito Davila, Bobby Woodlen-tp; Eugene Johnson, Freddie Skerritt-as; Jose Madera-ts; Leslie Johnakins-bs; René Hernandez-p, arr.; Julio Andino-b; Frank Raul Grillo as Machito-congas, director; Carlo Vidalen-tumbadora (congas); José Mangual, Sr.-bongos; Ubaldo Nieto-timbales. New York, late 1948 or early 1949.

11. PUSH-KA-PEE SHE PIE - Louis Jordan

(Joe Willoughby- Walter Merrick- Louis Thomas Jordan)

Louis Thomas Jordan as Louis Jordan-v, ts; vocal chorus; Aaron Izenhall, Bob Mitchell, Harold Mitchell-tp; Josh Jackson-ts; Bill Doggett-p; James Jackson aka Ham-g; Billy Hadnott-b; Joseph Christopher Columbus Morris aka Crazy Chris Columbo as Joe Morris-d. Decca 24877. New York, April 12, 1949.

12. LONGHAIR’S BLUES-RHUMBA - Professor Longhair and his New Orleans Boys

(Henry Roeland Byrd aka Roy Byrd aka Professor Longhair aka Fess)

Henry Roeland Byrd aka Roy Byrd aka Fess as Professor Longhair-v, p; Robert Parker-ts; Charles Burbank-ts; possibly John Boudreaux-clave. Atlantic SD7225. New Orleans, circa December, 1949.

13. BONGO CITO - Slim Gaillard Sextet

(Bulee Gaillard aka Slim Gaillard)

Bulee Gaillard as Slim Gaillard-v; ts; Cyril Haynes-p; bongos; Armando Peraza-congas. MGM 10938 (49-S-390-4). New York, November 7, 1949.

14. TIN TIN DEO - Dizzy Gillespie

(Luciano Pozo Gonzáles aka Chano Pozo, Walter Gilbert Fuller aka Gil Fuller)

John Birks Gillespie as Dizzy Gillespie-tp; John Coltrane-ts; Milt Jackson-vibraphone; Kenny Burrel-g; Percy Heath-b; Carl Donnell Fields aka Kansas Fields-d. Savoy MG 12047. Detroit, March 1, 1951.