- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

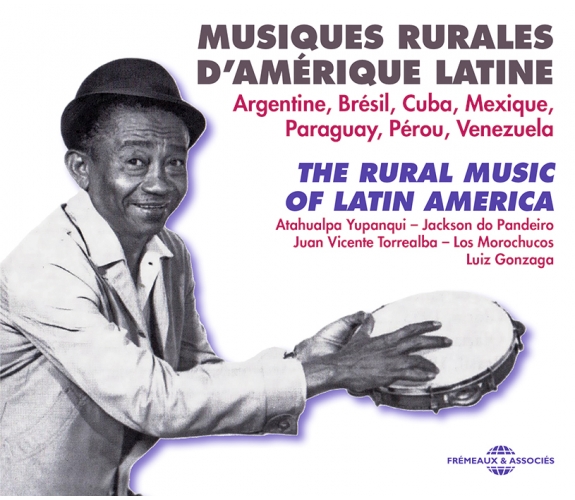

ATAHUALPA YUPANQUI • JACKSON DO PANDEIRO • VIOLETA PARRA • LOS MOROCHUCOS • LUIZ GONZAGA…

Ref.: FA5670

Artistic Direction : TECA CALAZANS ET PHILIPPE LESAGE

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Total duration of the pack : 3 hours 17 minutes

Nbre. CD : 3

ATAHUALPA YUPANQUI • JACKSON DO PANDEIRO • VIOLETA PARRA • LOS MOROCHUCOS • LUIZ GONZAGA…

ATAHUALPA YUPANQUI • JACKSON DO PANDEIRO • VIOLETA PARRA • LOS MOROCHUCOS • LUIZ GONZAGA…

The rural music of Latin America reflects the continent’s mental geography in showing how far Creole cultures have evolved and matured. The gap between the cities and rural areas didn’t widen until the early 19th century, mostly because of the slow diffusion, from urban centres to the interior, of new ideas and fashions influenced by Europe. These recordings made between 1930 and 1960 — by the Cubans Don Azpiazu, Gonzalo Roig and the Septeto Nacional, the Argentineans Atahualpa Yupanqui, Los Morochucos and Los Chalchaleros, the Venezuelan Los Torrealberos, and Brazilians like Luiz Gonzaga or Jackson do Pandeiro — measure the pulse of the rural popular music that remained very much alive despite the appearance of urban genres like the choro, samba, tango and mambo. Philippe LESAGE ET Teca CALAZANS

LUIZ GONZAGA • SIVUCA • CHIQUINHO DO ACCORDEON •...

BADEN POWELL • PAULO MOURA • WALDIR AZEVEDO • ABEL...

AVEC WALTER ALFAIATE, LUIZ CARLOS DA VILA, QUINTETO...

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Madrugada LlaneraLos TorrealberosJ.V. Torrealba00:02:541958

-

2El ArrieroAtahualpa YupanquiAtahualpa Yupanqui00:03:021958

-

3Los Ejes De Mi CarretaLuiz Alberto del PalmaAtahualpa Yupanqui00:03:121959

-

4Aquela NocheLos TorrealberosJ.V. Torrealba00:02:501958

-

5Chakai MantaLos ChalchalerosV. Ledesma00:01:521958

-

6Viene ClareandoLos ChalchalerosAtahualpa Yupanqui00:03:391958

-

7Mananitas MendocinasLos ChalchalerosG. Pelayo Patterson00:02:201958

-

8Las Caricias De CristinaLos TorrealberosJ.V. Torrealba00:02:281958

-

9El GavilanAngel Custodio LoyolaJ.V. Torrealba00:02:431958

-

10Sueno AzulLos TorrealberosJ.V. Torrealba00:02:541958

-

11Pajaro CampanaLes 4 GuaranisPerez Cardoso00:03:111953

-

12Luna TucumanaAtahualpa YupanquiAtahualpa Yupanqui00:03:051958

-

13Chacarera Del PantanoAtahualpa YupanquiAtahualpa Yupanqui00:01:561958

-

14BurruyacuAtahualpa YupanquiAtahualpa Yupanqui00:03:111958

-

15El Zamba Del TristeLos ChalchalerosAtahualpa Yupanqui00:03:431958

-

16Una LagrimaLos ChalchalerosAtahualpa Yupanqui00:02:031958

-

17La BochincheraLos ChalchalerosE. Velasquez00:01:561958

-

18El BergantinVioletta ParraTraditionnel00:02:431958

-

19Soy CarnavalLos AndariegosZaldivar00:02:211958

-

20Zamba Del PanueloAtahualpa YupanquiG. Leguizamon00:03:161961

-

21Lena VerdeAtahualpa YupanquiAtahualpa Yupanqui00:02:541958

-

22Guapo Mi Viejo BueyLes 4 GuaranisEmilio Bigi00:03:181953

-

23El HumahuaquenoLos AndariegosZaldivar00:02:571958

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Fina EstampaLos MorochucosGranda Chabuca00:02:191962

-

2Mi MorenaLos MorochucosRecp Ayarza00:03:361962

-

3HermelindaLos MorochucosInconnu00:02:391962

-

4CumbiaLos MorochucosRecp Ayarza00:02:161962

-

5TuGonzalo RoigEduardo Sanchez de Fuentes00:03:251958

-

6Flor De YumuriGonzalo RoigG. Roig00:02:571958

-

7Mi RecuerdosLos TorrealberosJ.V. Torrealba00:02:481958

-

8La GuayabaLos TorrealberosJ.V. Torrealba00:03:091958

-

9Buey ViejoSepteto Nacional d'Ignacio PineiroIgnacio Pineiro00:02:341959

-

10Cerro La SillaLos Charros de AmecaAntonio Tanguma00:02:281960

-

11Sopa De ChochocaEl Jilguero del HuascaranErnesto Sanches00:02:421960

-

12La JuaquinitaConjuto MadrigalInconnu00:02:411960

-

13Canto A Vera CruzConjonto Terra Blanca de Chico BarcelataInconnu00:03:081957

-

14El CascabelConjonto Terra Blanca de Chico BarcelataInconnu00:03:141957

-

15La BambaConjonto Terra Blanca de Chico BarcelataZo Barcelata Castro Loren00:02:281957

-

16Los RuegosLos MorochucosTraditionnel00:03:011962

-

17El PalmeroLos MorochucosTraditionnel00:03:161962

-

18La Carreta CampesinaOrquesta Peru RimaCardozo Ocampo00:03:351960

-

19El Pecho Se Me Ha CerradoMaguina AliciaAlicia Maguina00:03:061962

-

20Marinera E ResbalosaAlicia MaguinaAlicia Maguina00:03:061962

-

21Paloma IngrataAlicia MaguinaVioletta Parra00:02:201958

-

22Zamba ZambitaLos MorochucosTraditionnel00:02:411962

-

23Soy De MorelitaConjuto MadrigalInconnu00:03:171960

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1LaguajiraDon ArpiazuDon Arpiazu00:03:141930

-

2Me Voy Pal PubloTrio Los PanchosMercedes Valdes00:02:561955

-

3El TrangueiroLos TorrealberosJ.V. Torrealba00:02:411958

-

4Capricios De CarmenLos TorrealberosJ.V. Torrealba00:03:091958

-

5Tempestade En El PalmarLos TorrealberosJ.V. Torrealba00:03:001958

-

6Forro De SurubimJackson do PandeiroJose Batista00:02:571959

-

7Cantiga Do SapoJackson do PandeiroJackson do Pandeiro00:02:491959

-

8Casaca De CouroJackson do PandeiroRui de Morais00:02:401959

-

9Dezessete E SetecentosLuiz GonzagaLuiz Gonzaga00:02:341959

-

10Pau De AraraLuiz GonzagaLuiz Gonzaga00:02:511952

-

11BoiaderoLuiz GonzagaKlecius Caldas00:02:461952

-

12SabiaLuiz GonzagaLuiz Gonzaga00:02:401951

-

13ImbalancaLuiz GonzagaLuiz Gonzaga00:02:491952

-

14Penerou GaviaoJackson do PandeiroJackson do Pandeiro00:02:461952

-

15Coco De ImprovisoJackson do PandeiroJackson do Pandeiro00:02:591960

-

16O Canto Da EmaJackson do PandeiroAlventino Cavalcanti00:02:421960

-

17Estrada Do CanindeLuiz GonzagaLuiz Gonzaga00:02:411951

-

18Vozes Da SecaLuiz GonzagaLuiz Gonzaga00:02:421953

-

19Asa BrancaLuiz GonzagaLuiz Gonzaga00:02:521950

-

20Respeita JanuarioLuiz GonzagaLuiz Gonzaga00:02:361956

-

21Meus CanarisLuiz VieiraLuiz Vieira00:03:301958

-

22Na Asa Do VentoLuiz VieiraLuiz Vieira00:03:041958

-

23Maria FiloLuiz VieiraLuiz Vieira00:03:011958

Musiques rurales FA5670

MUSIQUES RURALES D’AMÉRIQUE LATINE

Argentine, Brésil, Cuba, Mexique,

Paraguay, Pérou, Venezuela

THE RURAL MUSIC OF LATIN AMERICA

Atahualpa Yupanqui – Jackson do Pandeiro

Juan Vicente Torrealba – Los Morochucos

Luiz Gonzaga

DISCOGRAPHIE

CD1

1) MADRUGADA LLANERA (Juan Vicente Torrealba) - Los Torrealberos - chant Mario Suarez - LP Discos Banco Largo du Venezuela QBL-504 - Circa 1958

2) El ARRIERO Cancion Criolla (Atahualpa Yupanqui), Guitare et chant Atahualpa Yupanqui - LP LP Yupanqui / Zaldivar / Los Andariegos - « Folklore d’Argentine » / 1957 et 1958 ; parution 1961 - Odeon OSX 193 S

3) LOS EJES DE MI CARRETA (Atahualpa Yupanqui) Luiz Alberto del Parana Y su Trio Los Paraguayos - LP « Viaje Tropical » - Philips P 10119 - 1959

4) AQUELA NOCHE (Juan Vicente Torreaalba) - Los Torrealberos - Chant Mario Suarez - LP Discos Banco Largo du Vénézuela QBL-504 - Circa 1958

5) CHAKAI MANTA, Chacarera, (DESDE ALLA) (V. Ledesma / Hnos Abalos), Los Chalchaleros - LP « Chakai Manta » - RCA - AVL- 3137 -1958

6) VIENE CLAREANDO ; Zamba (Atahualpa Yupanqui / S. Aredes) - Los Chalchaleros - LP « Chakai Manta » - RCA AVL - 3137 -1958

7) MAÑANITAS MENDOCINAS, Cueca (G. Pelayo Patterson / E. Cabeza) - Los Chalchaleros - LP « Chakai Manta » - RCA - AVL- 3137 -1958

8) LAS CARICIAS DE CRISTINA (Juan Vicente Torrealba) - Los Torrealberos - LP Dos Criollisimos - CIMA 301 - Circa 1958

9) El Gavilan (Juan Vicente Torrealba) - Chant, Angel Custodio Loyola, LP Dos Criollisimos - CIMA 301 - Circa 1958

10) SUEÑO AZUL (Juan Vicente Torrealba) - Los Torrealberos - Chant Mario Suarez - LP Discos Banco Largo du Vénézuela QBL-504 - Circa 1958

11) PAJARO CAMPANA (Perez Cardoso) Les 4 Guaranis– BAM LD 302 - 1953

12) LUNA TUCUMANA - Zamba (Atahualpa Yupanqui) - Guitare et chant, Atahualpa Yupanqui. - LP Yupanqui / Zaldivar, Los Andariegos - « Folklore d’Argentine » / 1957 et 1958 ; parution 1961 - Odeon OSX 193 S

13) CHACARERA DEL PANTANO - Chacarera (P. Del Cerro / Atahualpa Yupanqui) Guitare et chant A. Yupanqui - LP LP Yupanqui / Zaldivar, Los Andariegos - « Folklore d’Argentine » - Odeon OSX 193 S - 1957 et 1958 ; parution 1961

14) BURRUYACU - Zamba (P. Del Cerro / Atahualpa Yupanqui) Guitare et chant A. Yupanqui. LP Yupanqui / Zaldivar, Los Andariegos - « Folklore d’Argentine » / 1957 et 1958 ; parution 1961 - Odeon OSX 193 S

15) EL ZAMBA DEL TRISTE - Los Chalchaleros - LP « Chakai Manta » - RCA AVL- 3137 -1958

16) UNA LAGRIMA - Bailecito (Recopilado por Hnos Aramayo) Los Chalchaleros - LP « Chakai Manta » - RCA AVL- 3137 -1958

17) LA BOCHINCHERA - Chaya Riojana (E. Velasquez / A. Chazarreta) Los Chalchaleros - LP « Chakai Manta » - RCA AVL- 3137 -1958

18) EL BERGANTIN - Vals (Folklore recop. y arreglos Violeta Parra), Guitare et chant Violeta Parra - LP EMI Odeon Chilena - 1958

19) SOY CARNAVAL - Carnavalito (E. P. Zaldivar) Guitare et chant E. P. Zaldivar. LP Yupanqui / Zaldivar, Los Andariegos - « Folklore d’Argentine » / 1957 et 1958 ; parution 1961 - Odeon OSX 193 S

20) ZAMBA DEL PANUELO - Zamba (G. Leguizamon / M.J. Castillo) Chant et Guitare Atahualpa Yupanqui - LP Yupanqui / Zaldivar, Los Andariegos - « Folklore d’Argentine » / 1957 et 1958 ; parution 1961 - Odeon OSX 193 S

21) LENA VERDE - Milonga Pampeana - (Atahualpa Yupanqui) Chant et guitare A. Yupanqui. LP Yupanqui / Zaldivar, Los Andariegos - « Folklore d’Argentine » / 1957 et 1958 ; parution 1961 - Odeon OSX 193 S

22) GUAPO MI VIEJO BUEY - Canción (Emilio Bigi / Romero Valdovinos) - Los 4 Guaranis - BAM LD 302 - 1953

23) EL HUMAHUAQUENO - Carnavalito (E. Zaldivar) Chant et Guitare E. Zaldivar et Los Andariegos. LP Yupanqui / Zaldivar, Los Andariegos - « Folklore d’Argentine » / 1957 et 1958 ; parution 1961 - Odeon OSX 193 S

CD2

1) FINA ESTAMPA - Vals (Chabuca Granda) - Los Morochucos - LP Music of Peru, Parlophone PMC 1217 -1962

2) MI MORENA - Danza (Recp. De Rosa Morena Ayarza) - Los Morochucos, LP Music of Peru, Parlophone PMC 1217 - 1962

3) HERMELINDA - Los Morochucos - LP Music of Peru, Parlophone PMC 1217 - 1962

4) CUMBIA (Recp Ayarza) Los Morochucos - LP Music of Peru, Parlophone PMC 1217 - 1962

5) TU - Habanera (Eduardo Sanchez de Fuentes), Gonzalo Roig Orchesta - RCA Victor LPM 1531 1958

6) FLOR DE YUMURI - Habanera, (Jorge Anckermann), Gonzalo Roig Orchesta - RCA Victor LPM 1531 - 1958

7) MIS RECUERDOS (Juan Vicente Torrealba) Los Torrealberos, Chant Angel Custodio Loyola, LP Dos Criollisimos - CIMA 301 - Circa 1958

8) LA GUAYABA (Juan Vicente Torrealba) Los Torrealberos, Chant Angel Custodio Loyola), LP Dos Criollisimos - CIMA 301 - Circa 1958

9) BUEY VIEJO - Son Montuno (Ignacio Piıñeiro) Septeto National - WS Latino WS 4085 - 1959

10) CERRO LA SILLA - Redova (Antonio Tanguma) Los Charros de Ameca, LP Bailes Regionales Peerless LPL 334 - Circa 1960

11) SOPA DE CHOCHOCA (Ernesto Sanches), El Jilguero del Huascarán - Odeon, LD-1268 - Circa 1960

12) LA JUAQUINITA - Conjunto Madrigal - LP Norteña Alegre - Discos Corona DCL -1007 - Circa 1960

13) CANTO A VERA CRUZ - (huapango) Conjunto Tierra Blanca de Chico Barcelata, LP Veracruz Columbia HL 8138 - 1957

14) EL CASCABEL - Son Jarocho, Conjunto Tierra Blanca de Chico Barcelata, LP Veracruz, Columbia HL 8138 - 1957

15) LA BAMBA - Conjunto Tierra Blanca de Chico Barcelata, LP Veracruz, Columbia HL 8138 - 1957

16) LOS RUEGOS - Traditionnel ; triste con fuga de tondero -Los Morochucos - LP Music Of Peru, Parlophone PMC 1217 - 1962

17) EL PALMERO - Traditionnel ; Marinera y resbalosa - Los Morocuchos - LP Music Of Peru, Parlophone PMC 1217 - 1962

18) LA CARRETA CAMPESINA - Purajhei ; (Cardozo Ocampo/ Diosnel Chase) Orquesta « Peru Rima » Dúo Soler Sanabria, Industrias Fono electonicas Guarania / 300 c/ 1960

19) EL PECHO SE ME HA CERRADO - Marinera (Velásquez e su conjunto) Alicia Maguiña, LP Marinera e Resbalosa - Sonoradio LPL 2223 - 1962

20) MARINERA E RESBALOSA - Traditionnel - Alicia Maguiña, (Lucho de la Cuba al piano) LP Marineira e Resbalosa - Sonoradio LPL 2223 - 1962

21) PALOMA INGRATA - Mazurca (Folklore recop y arreglos Violeta Parra) – Guitare et chant, Violeta Parra. LP EMI Odeon Chilena, 1958

22) ZAMBA ZAMBITA - Marinera - Traditionnel Los Morochucos - LP Marinera e Resbalosa Sonoradio LPL 2223 - 1962

23) SOY DE MORELITA - Conjunto Madrigal - LP Nortena Alegre, Discos Corona DCL - 1007 - Circa 1960

CD3

1) LA GUAJIRA - Rumba, (Don Azpiazu) Don Azpiazu et son Orchestre - Disques Gramophone - K-6713 - 50-2564 - 1930

2) ME VOY PAL PUEBLO - Guajira, (Mercedes Valdés) Trio Los Panchos - Columbia CB-2 .053-B, 1955

3) EL TRANGUEIRO (Juan Vicente Torrealba) Los Torrealberos - Chant Mario Suarez - LP Discos Banco Largo du Vénézuela QBL-504 - Circa 1958

4) CAPRICIOS DE CARMEM (Juan Vicente Torrealba) Los Torrealberos - Chant Mario Suarez - LP Discos Banco Largo du Vénézuela QBL-504 - Circa 1958

5) TEMPESTADE EN EL PALMAR (Juan Vicente Torrealba), Los Torrealberos - Chant Mario Suarez - LP Discos Banco Largo du Vénézuela QBL-504 - Circa 1958

6) FORRO DE SURUBIM (José Batista / Antonio Barros da Silva) - Chant, J. do Pandeiro, LP Jackson do Pandeiro e seu conjunto, COLUMBIA - CB 3.097 - 1959

7) CANTIGA DO SAPO (Jackson do Pandeiro / Buco do Pandeiro) Chant, J. do Pandeiro, LP Jackson do Pandeiro - COLUMBIA LPCB 37056 - 1959

8) CASACA DE COURO (Rui de Morais / E. Silva) Chant, J. do Pandeiro LP Jackson do Pandeiro - Columbia LPCB 37056 - 1959

9) DEZESSETE E SETECENTOS (L. Gonzaga / Miguel Lima), Chant et accordéon, Luiz Gonzaga, LP Xamego RCA Victor BBL 1015 - 1959

10) PAU DE ARARA (L. Gonzaga / Guio de Moraes) Chant et accordéon, Luiz Gonzaga - 78 RPM RCA Victor, 80-09-36 A - 1952

11) BOIADERO (Klécius Calda / Armando Cavalcanti) - Chant et accordéon, Luiz Gonzaga - 78 RPM RCA Victor - 80-0717-A - 1950

12) SABIA (Luiz Gonzaga / Zé Dantas) - Chant et accordéon, Luiz Gonzaga - 78 RPM RCA Victor 80-08-27-A- 1951

13) IMBALANÇA (Luiz Gonzaga / ZÉ Dantas) Chant et accordéon, Luiz Gonzaga - 78 RPM RCA Victor, 80-08-94- A, 1952

14) PENEROU GAVIÃO (Jackson do Pandeiro / Odilon Vargas), Chant, J. do Pandeiro, LP Jackson do Pandeiro, Columbia LPCB 37056 - 1959

15) COCO DE IMPROVISO (Edson Menezes / Alventino Cavalcanti / Jackson do Pandeiro) Chant, J. do Pandeiro, LP Sua Maiestade, o Rei do Ritmo - Copacabana CLP 10023 - 1960

16) O CANTO DA EMA (Alventino Cavalcanti / Aires Viana / João do Vale) Chant, J. do Pandeiro, LP Sua Maiestade o Rei do Ritimo - Copacabana CLP 10023 - 1960

17) ESTRADA DO CANINDÉ (Luiz Gonzaga / Humberto Teixeira) - Toada, Chant et accordéon, Luiz Gonzaga - 78 RPM RCA Victor 80-0744-A - 1951

18) VOZES DA SECA (Luiz Gonzaga / Zé Dantas) Chant et accordéon, Luiz Gonzaga - RCA Victor 78 RPM 80-1193-A, 1953

19) ASA BRANCA (Luiz Gonzaga / Humberto Teixeira) Chant et accordéon, Luiz Gonzaga - 78 RPM - RCA Victor 800510- 1950

20) RESPEITA JANUÁRIO (Luiz Gonzaga / Humberto Teixeira) Chant et accordéon, Luiz Gonzaga, LP A História do Nordeste na voz de Luiz Gonzaga - RCA Victor BLP 3004 - 1956

21) MEUS CANARIS –Baião, (Luiz Vieira / Timoteo Martins) Chant Luiz Vieira - LP Retalhos do Nordeste, Copacabana CLP - 11041, 1958

22) NA ASA DO VENTO - Schottish (Luiz Vierira / João Vale) Chant Luiz Vieira - LP Retalhos do Nordeste - Copacabana CLP - 11041, 1958

23) MARIA FILÓ (O DANADO DO TREM) Corridinho, (Luiz Vieira / João Vale) - Chant Luiz Vieira - LP Retalhos do Nordeste, Copacabana CLP - 11041, 1958

MUSIQUES RURALES D’AMERIQUE LATINE

Argentine, Brésil, Cuba, Mexique, Paraguay, Pérou, Venezuela

La géographie mentale de l’Amérique Latine : L’appellation Amérique Latine englobe l’Amérique du Sud proprement dite, l’Amérique Centrale et Les Caraïbes. Sous les colonisations espagnole, portugaise, anglaise et française, ces contrées aux populations amérindiennes, noires et blanches offrirent au monde une miction de cultures et de belles musiques métissées. Cette anthologie revisite le patrimoine des musiques rurales qui a perduré au fil des siècles malgré l’apparition des genres citadins récents comme le samba, le tango ou le mambo.

Les musiques rurales sont le reflet de la géographie mentale de l’Amérique Latine et de l’interpénétration des cultures aussi bien sur les genres musicaux, sur les thématiques et les formes poétiques que sur la lutherie. A leur écoute, en filigrane, se dessine l’indicible poids de l’histoire et l’unité culturelle née dans la diversité des évènements. Elles disent l’incontournable fertilisation espagnole (et portugaise au Brésil), les stigmates de l’esclavagisme sur les « nations » noires, le fatalisme des peuples amérindiens ainsi que l’épanouissement de la culture créole en un nationalisme qui chante les beautés de la terre natale. On donne, à la fin du 19e siècle, le nom d’américains à tous les créoles sans distinction de couleurs et l’identité continentale commune se forge face aux espagnols et aux portugais qui deviennent alors des étrangers.

Le champ géographique et temporel de l’anthologie : mis à part une échappée caribéenne vers l’île de Cuba, on s’attachera avant tout au sous-continent sud-américain proprement dit et aux expressions musicales qui résistèrent jusqu’au milieu des années 1960. Fait d’importance à relever, ce n’est qu’à la fin du 18e siècle que se creuse inexorablement l’opposition entre cité et campagne. Les sources explicatives de cet antagonisme tiennent pour une large part à la lente circulation de l’information, des idées et des modes entre les capitales sous influence de l’Europe et l’intérieur des terres. Comme le souligne Carmen Bernand, dans son livre Genèse des Musiques d’Amérique Latine, dans les vastes territoires américains, le moindre déplacement le long des chemins de terre relève de l’expédition. Ce sont des pistes qui s’embourbent, des rivières qui débordent, des pans de routes qui s’effondrent, rebelles aux véhicules modernes, assertion confortée par l’écrivain Alejo Carpentier, dans son livre La musique à Cuba, lorsqu’il précise qu’au début du siècle dernier, il fallait plusieurs jours pour voyager de Santiago de Cuba à La Havane. Traduction sur le plan musical de cet état de fait : la musique rurale argentine, par exemple, n’a rien à voir avec la musique qui éclot à Buenos Aires. Lorsqu’il sillonne les terres de l’intérieur de son pays, guitare en bandoulière, en bon « payador » qu’il est au début du XXe siècle, Carlos Gardel chante « gato », « jota », « estilo » et des « vals » et non pas les tangos qui feront sa gloire lorsqu’il s’installera dans la capitale. Et si Atahualpa Yupanqui et Edmundo P. Zaldivar - qui fut pourtant un des guitaristes du bandonéoniste Anibal Troilo - s’ouvrent à d’autres thématiques et d’autres genres musicaux que Julio de Caro ou Astor Piazzolla, c’est que l’Argentine rurale va au-delà de l’image des immigrants italiens qui envahissent le port de Buenos Aires, au-delà même du symbole du gaucho, pour dépeindre les muletiers, les agriculteurs « mestizos », ces métis d’indien et d’espagnol. Et à Cuba, où l’influence noire est plus prégnante, il est évident que le « son » et la « guajira » donnés par le Septeto Nacional n’ont rien à voir avec le « mambo » et le « chá-chá-chá » à venir qui, eux, sont plus des genres musicaux pour le cabaret, les casinos et la nuit. Au Venezuela, la ruralité se note dans une prégnance amérindienne plus audible avec l’arpa criolla et les maracas et plus on descend vers le sud du continent, plus les sonorités amérindiennes sautent aux oreilles. C’est sensible au Paraguay, dans le nord de l’Argentine et au Pérou (qui a quand même, bien qu’on le sache peu, une dense population noire qui innerve sa musique). Le Nordeste brésilien s’habille des couleurs du « caboclo » (métis d’indien et de blanc), sur des rythmes plus proches de ceux de la Colombie et de Saint Domingue mais avec une identité bien spécifique qui tranche avec le reste du continent comme on pourra le noter à l’écoute de notre compilation. Loin de se vouloir travail ethno-musicologique, notre anthologie se penche sur les enregistrements réalisés au cours des années 1940 à 1960 afin de prendre le pouls de musiques populaires rurales toujours vivaces.

Genres musicaux et lutherie : Comme faire appel à un témoignage de première main semblait judicieux, j’ai longuement interrogé Sergio Valdeos, musicien péruvien membre fondateur de Maogani, un merveilleux quartet de guitares, et qui fut pendant plus de sept années l’accompagnateur de la chanteuse (et ministre de la culture du Pérou) Susana Baca. Ses réponses donnent un bon éclairage sur les musiques andines. A la question : « peut-on considérer la guitare d’origine espagnole comme étant aussi un instrument péruvien ? », il précise que la guitare est bien un instrument européen mais que le peuple latino-américain utilise pour s’exprimer et s’accompagner et que dès son arrivée, l’instrument s’est adapté à chaque rythme et à chaque genre. Au Pérou, dit-il, selon les régions, on change le toucher des cordes, on accorde différemment et on donne diverses ornementations et comme l’instrument fait toujours partie de l’âme des fêtes, il s’est rompu à toutes les nécessités. Ainsi de nos jours, il existe même des manières de fabriquer l’instrument selon les lieux. Quant à la musique la plus marquée par la ruralité, il répond que cela dépend beaucoup des régions mais qu’en général le « huayno » est le dénominateur commun mais que la valse (vals selon l’écriture locale) fut le genre le plus dansé et enregistré au cours du 20° siècle, surtout jusqu’aux années 1960. Il précise aussi que le « festejo » est un terme générique pour les nombreuses danses afro-péruviennes qui ont un rythme assez similaire. Sur les traces laissées dans la musique par les Incas, il ne manque pas de souligner au béotien européen que le passé du Pérou est bien plus ancien que l’histoire des Incas qui ne fut qu’un empire qui avait conquis des peuples qui avaient déjà une culture très ancienne. Il est ainsi normal que dans la musique des Andes, l’influence de ces peuples reste très présente jusque dans la manière de jouer de la guitare qui est unique au monde. D’eux, nous viennent de nombreux instruments à vent comme les quenas, zamponhas, tarkas et des instruments de percussions. Quand les instruments européens arrivèrent, ajoute t’il, ils furent associés aux styles musicaux locaux, ce qui a enrichi les timbres des musiques andines. De nombreux genres musicaux, le plus souvent liés aux fêtes et aux danses sont regroupés sous un terme générique : le huayno, mais terme qui diffère selon les régions sous les appellations huaycas, carnavales, danças de Tijeras, llamenadas.

En complément des précisions données par notre interlocuteur, élargissons le panorama vers quelques genres musicaux et danses de l’Amérique du Sud en commençant par la « marinera ». C’est une danse autrefois appelée «zamacueca » et qui a voyagé dans toute l’Amérique Latine sous diverses dénominations. Au Pérou, elle s’appelle « marinera » en l’honneur de la Marine de guerre qui est intervenue contre le Chili. L’histoire est bien longue mais en synthèse, la « zamacueca » revint du Chili sous une forme différente en étant dénommée « zamacueca chilienne » ou « chilena ». La guerre terminée, il y eut une résistance du peuple à appeler cette danse déjà assimilée sous le nom de «chilena » ; ce fut donc la raison pour laquelle son nom fut changé en « marinera ». Autre danse incontournable : la « Chacarera ». Vibrante, (rythme ternaire en 6/8) et s’appuyant sur la guitare, le charango et un « bombo ligeiro », c’est une danse de conquête amoureuse avec zapateado de gaucho et qui vient donc de la Pampa argentine. Le « Joropo », que l’on écoute en Colombie et au Venezuela, remonte au 18° siècle et découle du fandango espagnol. Cette musique rapide est interprétée à l’arpa criolla, au cuatro et aux maracas, par contre, la « tonada », présente au Venezuela mais aussi au Chili et en Argentine et qui vient d’Espagne, ne se danse pas. La « guajira », dont l’origine est souvent attribuée au compositeur cubain Jorge Anckermann, se déploie sur un rythme lent proche du « son » et elle évoque clairement dans ses paroles (en « décima » : dix pieds) la vie rurale. Très métissée parce que née dans les veillées funèbres au son des tambours des esclaves, la « cumbia » s’est enrichi des sonorités des flûtes et des ocarinas amérindiens et des mélodies, paroles et pas de danse des espagnols. Le « triste » (ou Yaravi ») porte bien son nom puisqu’il est un équivalent sud-américain du blues alors que la « zamba » (rien à voir avec le samba brésilien) est une danse où un cavalier fait la cour en faisant passer un foulard sur la tête de sa compagne. De caractère noble et viril, le « gato » se danse par couples séparés sur pas de valse avec zapateado. D’influence quechua, la « cueca » est la danse des amoureux : le danseur agite de la main droite un fin mouchoir de couleur pendant que la danseuse relève timidement sa jupe de la main gauche ; lui, la main gauche sur la hanche, paume en dehors, cherche à la conquérir. Le « Carnavalito », un « huayno » si souvent entendu dans les couloirs du métro après que Zaldivar s’en soit emparé pour en faire un succès planétaire, provient du Pérou et de la Bolivie. Toujours lié au carnaval… et à l’alcool fort qu’est la chicha, il y a le « humahuaqueno ». Cette danse d’influence amérindienne, sur un fond musical de guitares, flûte et tambourins, ressemble au « bailecito » mais se danse en file (en file indienne si l’on peut dire), hommes et femmes se tenant par la main, le plus souvent dos et têtes courbées vers le sol comme résignés mais avec de temps à autre des élans qui font relever la tête et lever les bras en signe d’espérance. Très lié au monde des laboureurs du Paraguay, le « chococué purajhei » se signale par son caractère de révolte. Typique de Vera Cruz, le « son jarocho » fait appel à des percussions (mâchoires d’âne ou de cheval), harpe et zapateado. Le « baião » du nordeste brésilien, lancé par Luiz Gonzaga au mitan des années 1940, est une synthèse du motif du « rojão » et de la viola du cantador à la toada de l’aveugle des foires alors que le « coco » est une danse des caboclos (métis d’indiens et de noirs) où un « coqueiro » (chanteur soliste) lance les vers qui sont repris par le chœur de la ronde.

Après l’arrivée des conquistadors, il y a eu interpénétration des influences culturelles dans la lutherie. La « arpa criolla » est un instrument diatonique à 36 cordes et le charango, qui accompagne le plus souvent le « carnavalito », le « bailecito » et la « cueca », lui, est un instrument à 8 cordes tendues sur une carapace de tatou ou à cinq cordes doubles accordées par octaves. Du côté des instruments percussifs, on trouve le caja (petit tambour rudimentaire sur lequel on frappe avec une seule baguette), le bombo qui est fait à partir d’un tronc évidé et qui se joue avec une baguette à bout ouatée, les maracas à l’influence amérindienne marquée avec leurs graines et les indispensables triangles et zabumbas (large tambour proche d’une grosse caisse) des trios nordestins. On n’oubliera pas, bien sûr, les instruments à vent dont le plus symbolique est la quena qui est un type de flûte à bec.

Les chemins de la poésie populaire : Les bons paroliers de chansons sont toujours considérés comme des poètes en Amérique du Sud et bien des chansons à charge symbolique qui rivalisent avec les meilleurs romans ne manquent pas de nous émouvoir. « Aube radieuse, un coq chante, au loin un chien aboie, les vaches s’y mettent, le llano s’éveille » : ce sont les premiers vers de Madrugada Llanera qui ouvrent notre anthologie et qui donnent la clé de tout ce qui va s’ensuivre. Dans Los Ejes de Mi Carreta (les essieux de ma charrette), les vers d’ Atahualpa Yupanqui disent la solitude du muletier : « Porque no engraso los ejes/ me llaman abandona’o / Si a mi me gusta que suenem/ Pa que los quiero engrasar ?/ No necessito silencio/ Yo no tengo en qui pensar/ Tenia, pero hace tiempo/ Ahora, ya no tiengo mais / Les ejes de mi carreta/Nunca los voy a engrasar » (Pourquoi je ne graisse pas les essieux de ma charrette/ Si ça me plait qu’ils fassent du bruit/ Pourquoi je les engraisserais/ Je n’ai pas besoin de silence/ Je n’ai personne à qui penser/ Il y avait quelqu’un mais cela fait longtemps/ Maintenant, je ne pense plus/ Les essieux de ma charrette/ Je ne les graisserai jamais ». Atahualpa Yupanqui s’inscrit dans la même veine dans El Arriero : « Las penas y las vaquitas/ Se van por la misma senda/ Las penas son de nosotros/ Las vaquitas son ajenas/ Y admirando la tropa, dale que dale/ El arriero va, el arriero va » (les peines et les vaches/ vont par le même chemin/ Les peines sont à nous/ les vaches aux autres/ Et en admirant le troupeau, vaille que vaille / le bouvier va… ». De son côté, le brésilien Luiz Gonzaga nous fait sentir ce qu’est quitter sa terre pour fuir la sécheresse : « Quando olhei a terra ardente/Qual fogueira de São João/ Eu perguntei a Deus do céu, ai/ Por que tamanha judiação/ Que braseiro, que fornália/ Nem um pé de plantação/ Por falta d’agua perdi meu gado/ Morreu de sede meu alazão/ Até mesmo a Asa Branca/ Bateu asas do sertão/ Então eu disse adeus Rosinha/ Guarda contigo meu coração/hoje longe, muitas léguas/ numa triste solidão/ Espero a chuva cair de novo/ Pra mim voltar pro meu sertão » (Quand j’ai regardé la terre brulante/ comme un feu de Saint Jean/ J’ai demandé au Dieu du ciel/ Pourquoi une telle punition/ Quel brasier, quelle fournaise/ Pas un pied de plantation/ Par manque d’eau, j’ai perdu mon troupeau/ Mon alezan est mort de soif/ Même l’oiseau Asa Branca/ s’est envolé du sertão/ Donc je te dis adieu Rosinha/ garde-moi en ton cœur/ Maintenant loin, à mille lieues/ dans une triste solitude/ J’espère que la pluie va tomber de nouveau/ Pour que je puisse revenir dans mon sertão).

Quelques propos au sujet des artistes

Méconnu en nos contrées, le vénézuélien Juan Vicente Torrealba, venu du llano proche de Caracas encore riche d’haciendas dans sa jeunesse, est né en 1917 et, à l’heure où nous écrivons, semble-t’il toujours alerte. Spécialiste de la musique rurale, autodidacte, il est passé de la guitare à la «arpa criolla » qu’il associe dans ses disques au cuatro et aux maracas et, plus tardivement, à la contrebasse. Il a monté le groupe Los Torrealberos en 1948, et il a créé son propre label « Discos Banco Largo » qu’il fera vivre jusque dans les années 1970. Sa musique énergique, d’une émouvante beauté, a donné ses lettres de noblesse à la musique d’extraction folklorique de son pays en la stylisant. Il s’est appuyé sur deux fantastiques chanteurs à voix de ténor : Angel Custodio Loyola et Mario Suarez. Les enregistrements des Torrealberos sont si beaux qu’il est impossible de détacher son esprit des mélodies et de la scansion rythmique imprimée. Egalement vénézuélien, le Conjunto Tierra Blanca a été monté en 1957 par Chico Barcelata avec Mario Berrada Murcia (arpa criolla) ; Eduardo Hernandez (Guitarra), José Garcia Rosas (jarana veracruzana) et Jesus Diaz (requinto) et il s’est spécialisé dans les « sones zapateados ». Autre stature de géant de la musique du continent : Atahualpa Yupanqui (1908-1992). Son père d’ascendance quechua était fonctionnaire des chemins de fer et sa mère d’origine basque et son véritable nom est

Hector Roberto Chavero Aramburu. Après avoir parcouru, dès 1921, les chemins d’Argentine et de Bolivie, après s’être lié d’amitié avec l’anthropologue Alfred Métraux, il prendra la plume et sa guitare pour décrire la vie misérable des indiens et des métis et choisira le pseudonyme d’Atahualpa Yupanqui (« yupanqui » se traduisant par « grand méritant », soit le titre du cacique suprême des indiens quechua et Atahualpa en souvenir du nom du dernier empereur inca qui fut prisonnier des conquistadors en 1532). Militant communiste, il est emprisonné sous la dictature de Juan Peron puis il s’exile en France en 1950 où il se rapproche d’Aragon, d’Eluard, de Picasso et du poète espagnol Rafael Alberti. Il débute en première partie d’un tour de chant d’Edith Piaf à l’Athénée avant de connaître une notoriété largement méritée aussi bien en France qu’en Argentine. Il rédige des contes (El canto del viento) et compose des milongas, des widalas, des chacareras, des zambas, des bagualas, des canciones, toutes inspirées de ses pérégrinations dans les sierras. Son épouse canadienne Paula – Antoinette Pepin Fitzpatrick signe les paroles et parfois des mélodies sous le pseudonyme de Pablo Del Cerro. Sa discographie imposante, en partie disponible au Chant du Monde, commence en 1940 et ne s’éteindra qu’à sa mort intervenue à l’âge de 84 ans. Avec son côté sismographe des âmes, plein de sagesse et d’humanité, il impose dans ses chansons un climat où le silence entre les mots dit ce que sont les maux des hommes. Sa chanson Duerme Negrito a bercé bien des enfants du baby boom en France. Edmundo Porteño Zaldivar, né en 1917 à Palermo, un quartier de Buenos Aires, fut un temps lié au monde du tango. Comme guitariste, Il a accompagné Rosita Quiroga, Charlo, le bandonéoniste Ciriaco Ortiz et a aussi intégré le quartet Troilo/ Grela mais il s’est tourné, à un moment, vers une musique plus traditionnelle avec des zambas et des carnavalitos. Il compose en 1941 le carnavalito Humahuaca du nom d’une province du nord de l’Argentine, dans la province de Jujuy, proche du Chili et de la Bolivie et qui est située à plus de 3000 mètres et où la culture précolombienne et criollas est vivace. Son carnavalito, autant joué dans le monde entier que le fameux El Condor Pasa, en devient insupportable mais fige l’empreinte amérindienne. Ami d’Atahualpa Yupanqui, il est indéniable que Edmundo P. Zaldivar soit un grand musicien et avoir été un partenaire de l’immense bandonéoniste Anibal Troilo est plus qu’une signature de sa qualité artistique. Egalement argentin de Mendoza, le groupe Los Andariegos a été créé en 1954 et il a enregistré douze albums et fut le premier groupe vocal à intégrer dans le folklore argentin les troisième, quatrième et cinquième voix. La première formation comprenait Pedro Floreal Caldera, Claudio Santa Cruz, Rafael Tapia, Juan Carlos « Pato » Rodriguez, Angel Ritrovato (Cacho Ritro), Abel Gonzales, Francisco « rubio » Gimenez. Vers la fin des années 1960, le groupe s’est rapproché de la chanteuse Mercedes Sosa pour intégrer le mouvement « Nuevo Cancionero » à contenu plus social. Los Chalchaleros (traduction : merle à ventre roux) est un autre groupe argentin créé en 1948. L’album Chakai Manta (soit « desde alla » en espagnol ou en français « depuis longtemps ») a été enregistré en 1958 avec les musiciens suivants : Ricardo Federico Davalos - qui donne le style distinctif par un jeu éblouissant de guitare -, José Zambrano, Juan Carlos Saraiva aka El Gordo et Ernesto Cabeza. Le Pérou est représenté par Alicia Maguiña, née en 1938, et qui fut la compagne du grand compositeur populaire Carlos Hayre décédé récemment. Elle interprète dans notre anthologie des marineras de Lima et sa conséquence Resbalosa. Avant de rejoindre les fêtes familiales dans les années 1950, la marinera se donnait à Lima dans « El salon de los blancos » et dans « el calejon de los negros ». Groupe de Lima, actif de 1947 à 1962, Los Morochucos est un groupe péruvien composé d’Oscar Aviles, d’Augusto Ego-Aguirre et d’Alejandro Cortez. Bien représentatif du « meztizo » (métis d’indien et d’espagnol), le groupe aborde marinera, cumbia, tondero, triste (autre nom : yaravi) et danza à l’aide de la quena, du caja, du charango et du humanacar (petit tambour indien) et des flûtes de pan. Luis Osmar Meza a choisi comme pseudonyme Luis Alberto del Paraguay et il a fondé le trio Los Paraguayos, qui connut un réel succès à l’étranger, avec le harpiste Digno Garcia et Agustin Barboza remplacé plus tard par le harpiste José de los Santos et Robito Medina et Reynado Meza, le propre frère du fondateur. La chilienne Violeta Parra (1917-1967) avait un look à la Joan Baez et un tempérament de feu. Dès 1952, avec son frère Nicanor, elle a recueilli, un peu à l’image de l’américain Woody Guthrie, des chansons folkloriques dans tout le Chili avant de venir résider pendant deux ans en France où elle exposera ses tapisseries et enregistrera pour Le Chant du Monde. Elle s’est suicidée par amour alors qu’elle dirigeait une institution culturelle populaire dans son pays. Ses enfants Isabel et Angel vécurent leur exil en France lors de la dictature de Pinochet. Son œuvre, dans ses forces et faiblesses, est bien représentative de l’époque « folk ». Les cubains sont représentés par Gonzalo Roig (1890-1970), l’auteur du bolero Quiereme Mucho mais qui fut aussi le fondateur de la Orquesta Sinfonica de La Habana et de l’Opéra national. La Habanera Flor de Yumuri, qui est un thème enivrant, a été composée par Jorge Anckermann, autre personnalité d’envergure par ses dons et son action sur la vie musicale locale. Ignacio Piñeiro (1888-1969), d’extraction modeste, a tenu des métiers aussi divers que tonnelier, agent portuaire ou ouvrier dans l’industrie du tabac mais après être passé comme contrebassiste dans le Sexteto Occidente dirigé par la grande Maria Teresa Vera, il a fondé le Sexteto Nacional, vite devenu Septeto Nacional, en 1927. Créateur prolifique, ancré dans la veine afro-cubaine, il est l’auteur de Buey Viejo et il a laissé de nombreuses compositions sur divers genres : son-montuno, conga, guajira. Véritable institution, il a marqué la musique populaire de son île. L’immensité du Brésil et la diversité de ses paysages et de ses coutumes font que la musique du monde rural est bien représentée dans le patrimoine sonore du pays. Dans cette anthologie, nous avons retenu deux voix majeures et un petit maître nés dans le Nordeste. Luiz Vieira (né en 1928), a quitté Caruaru, petite ville de l’intérieur de l’Etat de Pernambouc à l’âge de treize ans pour vivre de petits boulots à Rio de Janeiro. Il connaitra un certain succès à la radio et à la télévision dans les années 1950 et 1960. Les véritables hérauts du Nordeste sont Luiz Gonzaga et Jackson do Pandeiro. Qui a eu la chance de voir en scène, même à la fin de sa vie, Luiz Gonzaga (1912-1989) mesure le magnétisme qui émanait de lui et son charisme bonhomme. Il était né dans une fazenda d’Exu, petit bled de l’Etat du Pernambouc et avait étudié la musique avec son père Januário, un bon accordéoniste amateur. Après un passage à l’armée, il rejoint le sud du Pays, travaille et enregistre à São Paulo et Rio de Janeiro. C’est à la fin des années 1940 qu’il décide de se vêtir en « Vaqueiro nordestino » (vacher nordestin) et qu’il rencontre son premier succès avec le chamego Vira E Mexe. Il trouvera en Miguel Lima, Humberto Teixeira et Zé Dantas des paroliers d’envergure qui sauront exploiter sa verve populaire et traduire en mots les joies et peines, le quotidien et les drames du petit peuple du Nordeste. L’humour qui ensoleille les textes cède parfois la place à une dimension plus grave lorsqu’il aborde l’exil des « retirantes », ces paysans quittant leur terre pour fuir la sécheresse comme dans Vozes da Seca, une toada – baião de 1953 ou dans Asa Branca de 1959. Cette dernière est une des chansons majeures du patrimoine sonore du pays et a été souvent reprise. A la fin de sa vie, Il effectuera une longue tournée avec Gonzaguinha qui avait toujours affirmé être son fils. S’il était français, on dirait de Jackson do Pandeiro (José Gomes Filho ; 1919-1982), qu’il est un « titi » ou un poulbot montmartrois. Sarcastique, grivois, narquois, taquin, libertaire, ses intonations sont le calque des expressions que l’on capte dans les ruelles des marchés. Sa manière si personnelle de chanter en décalant le phrasé fait qu’il délivre un swing puissant. Même si on peut classer ses enregistrements dans ce qu’on appelle aujourd’hui le « forró », il s’adonnait plus au rojão et au coco (synthèse afro-amérindienne) qu’au baião véhiculée par Luiz Gonzaga.

Teca Calazans et Philippe Lesage

© 2017 Frémeaux & Associés

THE RURAL MUSIC OF LATIN AMERICA

Argentina, Brazil, Cuba, Mexico, Paraguay, Peru, Venezuela

The mental geography of Latin America: The term Latin America covers South America proper, plus Central America and the Caribbean. In the colonies of settlers from Spain, Portugal, England and France, these Latin American countries with black, white and Amerindian populations provided the world with a blend of cultures and mixed-race music genres. The present anthology revisits the national heritage of rural music forms that have lasted over the centuries despite the appearance of recent urban genres such as the samba, tango or mambo.

Rural music forms reflect the mental geography of Latin America and also the interpenetration of its cultures, which have impacted music and its themes as much as poetic forms and instrument-making. Listening to the music, you can glimpse the indescribable weight of history that is implicit here along with the cultural unity born out of such a diversity of events. The music goes some way to explaining the inevitable Spanish fertilization (Portuguese in Brazil), the stigmata of slavery left on black “nations”, the fatalism of Amerindian peoples and the flowering of Creole culture in a nationalism that sings the beauties of native lands. At the end of the19th century, the name “American” was given to every Creole irrespective of colour, and a common national identity was forged in face of the Spanish and Portuguese, who then became foreigners.

The geographical and temporal scope of the anthology: Apart from a break in the Caribbean around Cuba, the aim here is above all to examine the South American subcontinent proper and the musical expressions that resisted until the mid-Sixties. It is important to note that it was only towards the end of the 18th century that the opposition between city and country began to develop inexorably. The sources that explain this antagonism depend mostly on the slow circulation of information, ideas and fashions between the region’s capital cities (under influences from Europe), and into the interior. As Carmen Bernand emphasizes in her book Genèse des Musiques d’Amérique Latine, the slightest movement along the dirt tracks crossing these vast American territories was nothing short of an expedition: trails that turned to mud, rivers in flood, whole sections of road that collapsed (if not already unsuitable for modern vehicles)… This was confirmed by Alejo Carpentier writing in Music in Cuba, where he says that at the beginning of the last century, Havana was still several days’ distant from Santiago de Cuba. Translating that fact into music, the rural genres of Argentina, for example, were totally different from the music that bloomed in Buenos Aires. When he criss-crossed the Argentinean interior with his guitar slung over his shoulder, Carlos Gardel, still a payador in that turn-of-the-century period, was singing gato, jota, estilo and vals, not the tangos that made his fame when he moved to the capital. If Atahualpa Yupanqui and Edmundo P. Zaldivar — even though he was one of the guitarists with the bandoneonista Anibal Troilo — were more open to other topics and music genres than Julio de Caro or Astor Piazzolla, it was because rural Argentina went beyond the image of the Italian immigrants who invaded the port of Buenos Aires, and even further than the “gaucho” symbol, to portray muleteers and farmers who were mestizos of mixed race, Indian and Spanish. In Cuba, where the black influence is more meaningful, it’s obvious that the son and the guajira played by the Septeto Nacional bear no relationship to the mambo and chá-chá-chá to come: the latter were kinds of music intended more for clubs and cabarets, casinos and the night. In Venezuela, rural aspects were to be noted due to their Amerindian significance, more audible, with the arpa criolla and maracas, and the further you go south, down into the continent, the more the sounds of Amerindians leap into your ears. This can be felt in Paraguay, in northern Argentina and in Peru (which, even though it’s not well known, has a dense black population that innervates its music). The Nordeste of Brazil wears the colours of the caboclo (“copper-coloured”, a person half-white, half-Indian) over rhythms closer to those of Colombia or Santo Domingo, but with a quite specific identity that stands out against the rest of the continent, as you will notice when listening to our compilation. Far from being the work of an ethno-musicologist recordings made from the Forties to the Sixties in order to take the pulse of rural popular music forms that remain very much alive.

Music genres and instrument making: Because it seemed judicious to have first-hand eyewitness accounts available, I interviewed Sergio Valdeos at length. Valdeos is a Peruvian musician, a founder member of the marvellous Maogani guitar quartet, and for more than seven years he accompanied singer Susana Baca (who was also Peru’s Minister of Culture). His answers throw much light on the music of the Andes. When I asked him if he considered the “Spanish” guitar a Peruvian instrument he pointed out that while the guitar was indeed a European instrument, Latin Americans used it to accompany and express themselves, and that as soon as it was introduced into the country, Peruvians adapted it to each and every rhythm and genre. In Peru, he said, depending on the region, the way the strings are played will change and the tuning is different also; the ornamentation varies and, because the instrument is always part of the life and soul of festive celebrations, it’s familiar with everyone’s needs. Today, there even exist different ways of manufacturing the instrument, depending on where you are.

As for the music that has the most rural nature, he said that it depended a lot on the region, but that in general the huayno was the common denominator, while the waltz (or vals as it’s locally written) was the genre most often danced and recorded in the course of the 20th century, especially up until the Sixties. Sergio Valdeos also made clear that festejo was a generic word for many Afro-Peruvian dances with a rather similar rhythm. Concerning the musical traces of the Incas, he also took care to underline — for this idiot of a European — that Peru’s past went back much further than the history of the Incas, whose empire had conquered populations who already had ancient cultures of their own. So it is normal that the influence of those populations remains very present in the music of the Andes, including in the unique way they play guitar. Numerous indigenous wind instruments were also handed down — the quena, zamponha and tarka flutes, percussion instruments — and when European instruments arrived, he added, they were associated with local music styles, which enhanced the timbres in Andes music. Many music genres, often linked to feasts and ceremonial dances, were grouped generically as huayno, but the term varies regionally depending on local names like huaycas, carnavales, danças de Tijeras or llamenadas.

To complement the information given by Sergio Valdeos we can extend the panorama to cover music genres and dances in South America, beginning with the marinera, which was formerly called the zamacueca and has travelled throughout Latin America under various names. In Peru it was known as marinera in honour of the navy, which intervened against Chile. It’s a long story but, in short, the zamacueca came back from Chile in a different form named either chilena or Chilean zamacueca; but once the war ended, people resisted the name chilena and changed it to marinera. Another unavoidable dance is the vibrant Chacarera with its ternary rhythm in 6/8; relying on guitar, charango and bombo ligeiro, the dance is an amorous conquest, complete with the zapateado of the gaucho, and so it comes from the Argentinean pampa. The Joropo heard in Colombia and Venezuela dates from the 18th century; based on Spain’s fandango, it has a quick tempo and is performed on the arpa criolla, the cuatro and maracas. On the other hand, the tonada present in Venezuela (and in Chile and Argentina) comes from Spain but is not for dancing. The guajira, whose origin is often attributed to Cuban composer Jorge Anckermann, unfolds over a slow rhythm close to the son, and its lyrics (written in a metre of ten feet) refer clearly to rural life. The cumbia owes its mixed-race nature to its origins in funeral vigils accompanied by the drums of slaves, made richer with the melodic timbres of Amerindian flutes and ocarinas, and the lyrics and dance steps of the Spanish. The Yaravi (meaning “sad”), lives up to its name as the South American equivalent of the blues, while in the zamba (which bears no relation to Brazil’s samba), the male dancer woos his female partner by passing a scarf around her head. Noble and virile in character, the gato is a pair dance for separated couples with waltz steps and zapateado. The Quechan-influenced cueca is the dance of lovers: the male partner waves a fine coloured handkerchief with his right hand while his partner shyly raises her skirt with her left hand; the male, his left hand on his hip with the palm turned outwards, seeks to conquer her. The Carnavalito, a huayno so often heard in the corridors of the Metro after Zaldivar made it a worldwide hit, comes from Peru and Bolivia. Still related to the carnaval — and to the strong alcohol called chicha — is the humahuaqueno. This dance influenced by the Amerindians is accompanied by guitars, flutes and tambourines and resembles the bailecito, except that it is danced in single file; men and women hold each other by the hand, and most often their heads and backs bow over towards the ground as if in resignation, but from time to time with sudden movements that cause their heads to raise, lifting their arms in signs of hope. Closely linked to the labourers’ world in Paraguay, the chococué purajhei stands out by its rebellious nature. Typical of Vera Cruz, the son jarocho calls for percussion (jawbones of donkeys or horses), harp and zapateado. The baião from Brazil’s Nordeste (launched by Luiz Gonzaga in the middle of the Forties) is a synthesis of the rojão and viola e cantador motifs with the toada of the blind at fairs, while the coco was danced by mixed-race (Indian and black) caboclos, with a soloist singing out verses that were picked up by everyone in chorus.

After the conquistadors’ arrival, instrument manufacture was also subject to various cultural influences. The arpa criolla is a diatonic instrument with 36 strings while the charango (most often seen accompanying the carnavalito, bailecito and cueca) has its strings tightened over the shell of an armadillo, either eight single ones or five double strings tuned in octaves. As for percussion, there was the simple caja (a rudimentary little drum struck with a single stick), the bombo (actually made from a hollowed-out trunk, and hit with a stick whose tip was wrapped in cotton), maracas, whose enclosed seeds showed marked Amerindian influence, not to mention the indispensable triangles and zabumbas (large drums close to the size of a bass drum) used by trios in the Nordeste. Plus, of course, various wind instruments, the most symbolic of which was the quena, a type of recorder.

The paths of popular poetry: Good song lyricists are always considered poets in South America, and many songs that are symbolically meaningful and rival the best novels have always been moving. “Radiant dawn, a cockerel singing, in the distance a dog barks, the cows join in, the llano wakens…” Those are the first lines from Madrugada Llanera that opens our anthology, and they provide the key to all that follows. In Los Ejes de Mi Carreta (“The axles of my cart”), Atahualpa Yupanqui’s verses tell of the solitude of the muleteer: Porque no engraso los ejes / Me llaman abandona’o / Si a mi me gusta que suenem / Pa que los quiero engrasar? / No necessito silencio / Yo no tengo en qui pensar / Tenia, pero hace tiempo / Ahora, ya no tiengo mais / Les ejes de mi carreta / Nunca los voy a engrasar.

[“Why grease the axles of my cart? If I like the noise they make, why would I? I don’t need silence; I’ve nobody to think about. There used to be someone, but that was long ago. Now I don’t think anymore, and the axles on my cart, I’ll never grease them.”]

Atahualpa Yupanqui is in the same vein in El Arriero: “Las penas y las vaquitas / Se van por la misma senda / Las penas son de nosotros / Las vaquitas son ajenas / Y admirando la tropa, dale que dale / El arriero va, el arriero va.” [“Troubles and cows, they take the same road, and while admiring the herd, the cattleman goes…”]

As for the Brazilian Luiz Gonzaga, he makes us feel what it is like to leave one’s lands due to drought: “Quando olhei a terra ardente/Qual fogueira de São João/ Eu perguntei a Deus do céu, ai/ Por que tamanha judiação/ Que braseiro, que fornália/ Nem um pé de plantação/ Por falta d’agua perdi meu gado/ Morreu de sede meu alazão/ Até mesmo a Asa Branca/ Bateu asas do sertão/ Então eu disse adeus Rosinha/ Guarda contigo meu coração/hoje longe, muitas léguas/ numa triste solidão/ Espero a chuva cair de novo/ Pra mim voltar pro meu sertão.” [“When I saw the earth burning like a Midsummer’s Night bonfire, I asked God in heaven, Why such a punishment? What a blaze, what a furnace! Not a single plant, for lack of water I’ve lost my herd. My chestnut horse has died of thirst, even the bird Asa Branca has flown away from the sertão. So I say goodbye, Rosinha, keep me in your heart. Now far away, a thousand leagues distant, in sad solitude, I hope the rain will fall again, so that I may return to my sertão.”]

A few notes on the artists

Unknown in Europe is the Venezuelan Juan Vicente Torrealba, from the llano near Caracas, an area still rich with haciendas when he was young. He was born in 1917 and, at the time of writing, he still seems as much on the alert as ever. A self-taught rural music specialist, he went from the guitar to the arpa criolla, which he uses on his records together with the cuatro, maracas and later the double bass. He founded the group Los Torrealberos in 1948 and created his own label, “Discos Banco Largo”, which he kept alive with his own recordings until the Seventies. His energetic music, movingly beautiful, gave his country’s folk music its letters patent of nobility: he stylised it. He was assisted by two fantastic tenor voices, those of Angel Custodio Loyola and Mario Suarez. Recordings by the Torrealberos are so beautiful that it’s impossible to take your mind off the melodies and the clearly defined rhythmic scansion. Also from Venezuela is the Conjunto Tierra Blanca group, which was set up in 1957 by Chico Barcelata with Mario Berrada Murcia (arpa criolla), Eduardo Hernandez (guitar), José Garcia Rosas (jarana veracruzana) and Jesus Diaz (requinto). The group specialized in zapateado sounds.

Another giant in the continent’s music was Atahualpa Yupanqui (1908-1992). His father was a Quechuan who worked on the railways, and his mother had Basque origins. His real name was Hector Roberto Chavero Aramburu, and after going on the road in Argentina and Bolivia as early as 1921, he became friends with anthropologist Alfred Métraux. He took up his pen and his guitar to describe the life of misery that befell Indians and half-breeds, and he chose as his pseudonym Atahualpa Yupanqui (the name Yupanqui means “greatly deserving”, i.e. the title of the supreme leader of the Quechua Indians, and Atahualpa in memory of the name of the last Emperor of the Incas, taken prisoner by the conquistadors in 1532). A militant communist, he was jailed by the dictator Juan Peron and then in 1950 he went into exile in France, where he became close to Aragon, Eluard, Picasso and the Spanish poet Rafael Alberti. He started singing by opening for Edith Piaf at the Athénée in Paris before achieving well-deserved fame both in France and Argentina. Yupanqui wrote tales (El canto del viento) and composed milongas, widalas, chacareras, zambas, bagualas and other songs inspired by his wanderings in the sierras. His Canadian wife Paula — Antoinette Pepin Fitzpatrick — wrote lyrics and sometimes melodies under the pseudonym Pablo Del Cerro. Yupanqui’s impressive discography, some of which is available from Le Chant du Monde, began in 1940 and he made records until he died at the age of 84. He was like a seismographer of souls, full of wisdom and humanity, and in his songs he established a climate in which the silences between words related the woes of mankind. His song Duerme Negrito was a lullaby for many children during the baby boom.

Edmundo Porteño Zaldivar, born in 1917 in the Palermo district of Buenos Aires, was linked with the world of tango for a time. As a guitarist he accompanied Rosita Quiroga, Charlo or the bandoneonista Ciriaco Ortiz, and was also a member of the Troilo-Grela quartet, but at one point he turned to more traditional music with zambas and carnavalitos. In 1941 he composed the carnavalito Humahuaca, named after a province in northern Argentina (in Jujuy close to Chile and Bolivia, a region ten thousand feet up in the mountains where Pre-Colombian culture and criollas still thrived. His carnavalito, played throughout the world as often as the famous El Condor Pasa, became unbearable because of it but it fixed the Amerindian imprint. Edmundo P. Zaldivar was a friend of Atahualpa Yupanqui, and is undeniably a great musician: having partnered the immense bandoneonista Anibal Troilo more than guarantees his qualities as an artist.

Also Argentinean, this time from Mendoza, is the group Los Andariegos. Formed in 1954, the group recorded twelve albums and was the first vocal ensemble to integrate the third, fourth and fifth voices in Argentinean folk music. The first line-up was comprised Pedro Floreal Caldera, Claudio Santa Cruz, Rafael Tapia, Juan Carlos “Pato” Rodriguez, Angel Ritrovato (Cacho Ritro), Abel Gonzales and Francisco “Rubio’ Gimenez. Towards the end of the Sixties, the group became close to singer Mercedes Sosa, joining the Nuevo Cancionero movement whose songs had a more social content. Los Chalchaleros (named after the American robin) was another Argentinean group created in 1948. The album Chakai Manta (meaning “so long ago”) was recorded in 1958 with the musicians Ricardo Federico Davalos (whose dazzling guitar gives the group its distinctive style), José Zambrano, Juan Carlos Saraiva a.k.a. El Gordo (the nickname means “Fatty”) and Ernesto Cabeza.

Peru is represented here by Alicia Maguiña; born in 1938, she was the companion of the great popular composer Carlos Hayre who died recently. Alicia performs marineras from Lima in our anthology and its conclusion Resbalosa (a Peruvian dance). Before appearing in family celebrations in the Fifties, marineras were performed in Lima, in “El salon de los blancos” and in “El calejon de los negros.” The group Los Morochucos from Lima was active from 1947 to 1962, and made up of Peruvians Oscar Aviles, Augusto Ego-Aguirre and Alejandro Cortez. They are very representative of mestizos (mixed Indian and Spanish race), and their repertoire comprises marineras, cumbias, tonderos, tristes (also known as yaravis) and danzas with instruments like the quena, caja, charango and humanacar (a little Indian drum) together with pan flutes.

Luis Osmar Meza chose the pseudonym Luis Alberto del Paraguay and founded Los Paraguayos, a trio that was very successful overseas with harpist Digno Garcia and Agustin Barboza, later replaced by the harpist José de los Santos and Robito Medina, and Reynaldo Meza, the founder’s own brother. Chilean singer Violeta Parra (1917-1967) was a Joan Baez lookalike and she had a fiery temperament. As early as 1952, together with her brother Nicanor she began putting together a collection of folk songs from all over Chile (a little like the American artist Woody Guthrie did for Americana songs), before going to live in France for two years, a period during which she exhibited her own tapestries and recorded for Le Chant du Monde. She took her own life due to a love affair after she was appointed to manage one of her country’s popular cultural institutions. Her children Isabel and Angel would live in exile in France during Pinochet’s regime. Violeta’s work, with all its strengths and weaknesses, is extremely representative of “the folk years”.

Composer Gonzalo Roig (1890-1970) represents Cuba here; he wrote the bolero Quiereme Mucho but was also the founder of the Orquesta Sinfonica of Havana and the Cuban National Opera. Jorge Anckermann, another musician who was a leading figure in Cuba due to his talent and activities on the local scene composed the habanera entitled Flor de Yumuri, an intoxicating theme. Ignacio Piñeiro (1888-1969), was variously a cooper, an agent for the Havana port authorities, and also worked in the tobacco industry, but he became the double-bass player with the Sexteto Occidente led by the great Maria Teresa Vera; he then founded the Sexteto Nacional (which quickly became the Septeto Nacional) in 1927. A prolific creator anchored in the Afro-Cuban vein, he was the author of Buey Viejo and left many compositions in various genres: son-montuno, conga, guajira. A veritable institution, he left his mark on popular music in Cuba.

The immensity of Brazil and the diversity of its landscape and customs have ensured that music from the rural world of Brazil would be well represented in the country’s heritage. For this anthology we have retained two major voices and a master, all from Brazil’s Nordeste. Luiz Vieira (born 1928) was 13 when he left Caruaru, a small town in the interior in the state of Pernambuco, to earn his living working at small jobs in Rio de Janeiro, and in his Twenties he was quite successful with a career in radio and television.

The real symbols of the Nordeste were Luiz Gonzaga and Jackson do Pandeiro. For those lucky enough to see Luiz Gonzaga (1912-1989) onstage, even towards the end of his life, they couldn’t fail to appreciate the magnetism that emanated from him and his easy-going charisma. He was born in a fazenda in Exu, a mere hamlet in Pernambuco, and he’d studied music with his father Januário, a good amateur accordionist. After military service he went back south to work and record in São Paulo and Rio. It wasn’t until the end of the Forties that he decided to appear dressed as a Vaqueiro nordestino or “Nordeste cowherd”, and his first hit was the chamego song Vira E Mexe. In Miguel Lima, Humberto Teixeira and Zé Dantas he found lyricists of great calibre who could exploit his popular verve and translate into words all the joys and troubles, all the everyday dramas of the ordinary folk in the northeast. The humour that shines in the texts sometimes gives way to a more serious dimension when he turns his attention to the retirantes, those peasants who abandoned their fields to flee from the drought, as in Vozes da Seca, a toada–baião of 1953, or in the 1959 song Asa Branca. The latter is one of the most important songs in the country’s heritage, and new readings of it often appear. Towards the end of his life he did a long tour with Gonzaguinha, who always claimed to be his son.

If Jackson do Pandeiro (José Gomes Filho, b. 1919, d. 1982) had been a Londoner they would have called him a cheeky Cockney: by turns sarcastic and saucy, often teasingly sardonic, his libertarian accents were a carbon copy of expressions heard in the streets and markets. He had such a personal way of shifting his phrasing that his intonation carried a powerful swing. Even if his recordings can be categorized as part of what is today called the forró, he devoted his efforts more to the rojão and coco (an Afro-Amerindian synthesis) than to the baião sung by Luiz Gonzaga.

Teca Calazans et Philippe Lesage

© 2017 Frémeaux & Associés

Reflet de la géographie mentale de l’Amérique Latine, les musiques rurales disent l’épanouissement de la culture créole. Ce n’est qu’au début du 19e siècle que se creuse le fossé entre cité et campagne due à la lente circulation des idées et des modes entre les capitales sous influence de l’Europe et l’intérieur des terres. Les enregistrements de 1930 à 1960 (les cubains Don Azpiazu, Gonzalo Roig, Septeto Nacional, les argentins Atahualpa Yupanqui, Los Morochucos, Los Chalchaleros, Los Torrealberos vénézuéliens et les brésiliens Luiz Gonzaga, Jackson do Pandeiro…) prennent le pouls des musiques populaires rurales qui restèrent vivaces malgré l’apparition de genres citadins comme le choro, le samba, le tango ou le mambo.

Philippe LESAGE et Teca CALAZANS

The rural music of Latin America reflects the continent’s mental geography in showing how far Creole cultures have evolved and matured. The gap between the cities and rural areas didn’t widen until the early 19th century, mostly because of the slow diffusion, from urban centres to the interior, of new ideas and fashions influenced by Europe. These recordings made between 1930 and 1960 — by the Cubans Don Azpiazu, Gonzalo Roig and the Septeto Nacional, the Argentineans Atahualpa Yupanqui, Los Morochucos and Los Chalchaleros, the Venezuelan Los Torrealberos, and Brazilians like Luiz Gonzaga or Jackson do Pandeiro — measure the pulse of the rural popular music that remained very much alive despite the appearance of urban genres like the choro, samba, tango and mambo.

CD 1

1) Madrugada Llanera (LOS TORREALBEROS) 2’52

2) EL Arriero (ZALDIVAR) 3’01

3) Los Ejeres de mi Carreta (LUIZ ALBERTO DEL PARANA) 3’10

4) Aquela Noche (LOS TORREALBEROS) 2’49

5) Chakai Manta (LOS CHARCHALEROS) 1’51

6) Viene Clareando (LOS CHARCHALEROS) 3’37

7) Mananitas Mendocinas (LOS CHARCHALEROS) 2’18

8) Las Carícias de Cristina (ANGEL C. LOYOLA) 2’27

9) EL Gavilan (ANGEL C. LOYOLA) 2’42

10) Sueño Azul (LOS TORREALBEROS) 2’53

11) Pajaro Campana (LOS 4 GUARANIS) 3’10

12) Luna Tucumana (A. YUPANQUI) 3’03

13) Chacarera del Pantano (A. YUPANQUI) 1’54

14) Burruyacu (A. YUPANQUI) 3’09

15) Zamba del Triste (LOS CHARCHALEROS) 3’41

16) Una lagrima (LOS CHARCHALEROS) 2’01

17) La Bochinchera (LOS CHARCHALEROS) 1’55

18) El Bergantin (VIOLETA PARRA) 2’42

19) Soy Carnaval (LOS ANDARIEGOS) 2’20

20) Zamba del Panuelo (A.YUPANQUI) 3’15

21) Lena Verde (A. YUPANQUI) 2’52

22) Guapo mi Viejo Buey (LOS 4 GUARANIS) 3’16

23) El Humahuaqueno (LOS ANDARIEGOS) 2’58

CD 2

1) Fina Estampa (LOS MOROCHUCOS) 2’18

2) Mi Morena (LOS MOROCHUCOS) 3’35

3) Hemelinda (LOS MOROCHUCOS) 2’37

4) Cumbia (LOS MOROCHUCOS) 2’14

5) Tu (GONZALO ROIG) 3’23

6) Flor de Yumuri (GONZALO ROIG) 2’55

7) Mi Recuerdos (ANGEL C. LOYOLA) 2’47

8) La Guayaba (ANGEL C. LOYOLA) 3’08

9) Buey Viejo (SEPTETO NACIONAL) 2’33

10) Cerro la Silla (LOS CHARROS DE AMECA) 2’26

11) Sopa de Chochoca (EL JILGUERO DEL HUASCARAN) 2’40

12) La Juaquinita (CONJUNTO MADRIGAL) 2’39

13) Canto a Vera Cruz (CONJUNTO TIERRA BLANCA) 3’06

14) El Cascabel (CONJUNTO TIERRA BLANCA) 3’12

15) La Bamba (CONJUNTO TIERRA BLANCA) 2’57

16) Los Ruegos (LOS MOROCHUCOS) 3’00

17) El Palmero (LOS MOROCHUCOS) 3’15

18) La Carretta Campesina (YMA GUARE) 3’33

19) El Pecho se me ha cerrado (ALICIA MAGUINA) 3’05

20) Marinera y Resbalosa (ALICIA MAGUINA) 3’05

21) Paloma Ingrata (VIOLETA PARRA) 2’19

22) Zamba, Zambita (LOS MOROCHUCOS) 3’40

23) Soy de Morelita (CONJUNTO MADRIGAL) 3’17

CD 3

1) La Guarija (DON AZPIAZU) 3’13

2) Me voy pal pueblo (LOS PANCHOS) 2’55

3) El Tranquero (LOS TORREALBEROS) 2’40

4) Caprichos de Carmen (L. TORREALBEROS) 3’07

5) Tempestad en El Palmar (LOS TORREALBEROS) 2’58

6) Forro de Surubim (JACKSON DO PANDEIRO) 2’56

7) Cantiga do Sapo (J. DO PANDEIRO) 2’48

8) Casaca de couro (J. DO PANDEIRO) 2’38

9) Deszessete e Setecentos (LUIZ GONZAGA) 2’33

10) Pau de Arara (LUIZ GONZAGA) 2’50

11) Boiadero (LUIZ GONZAGA) 2’45

12) Sabiá (LUIZ GONZAGA) 2’39

13) Imbalança (LUIZ GONZAGA) 2’48

14) Penerou Gavião (J. DO PANDEIRO) 2’45

15) Coco de Improviso (J. DO PANDEIRO) 2’58

16) O Canto da Ema (JACKSON DO PANDEIRO) 2’40

17) Estrada do Canindé (LUIZ GONZAGA) 2’39

18) Vozes da Seca (LUIZ GONZAGA) 2’40

19) Asa Branca (LUIZ GONZAGA) 2’50

20) Respeita Januario (LUIZ GONZAGA) 2’35

21) Meu Canari (LUIZ VIEIRA) 3’28

22) Na Asa do Vento (LUIZ VIEIRA) 3’03

23) Maria Filó (LUIZ VIEIRA) 3’01