- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

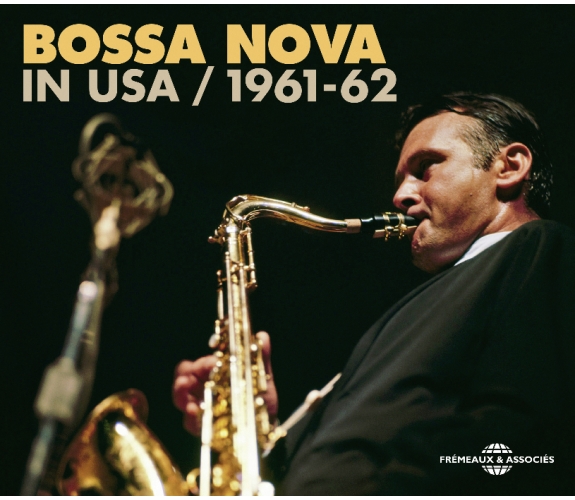

DIZZY GILLESPIE • STAN GETZ • DAVE BRUBECK • JON HENDRICKS • COLEMAN HAWKINS • LALO SCHIFRIN • …

Ref.: FA5482

Artistic Direction : TECA CALAZANS ET PHILIPPE LESAGE

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Total duration of the pack : 3 hours 18 minutes

Nbre. CD : 3

DIZZY GILLESPIE • STAN GETZ • DAVE BRUBECK • JON HENDRICKS • COLEMAN HAWKINS • LALO SCHIFRIN • …

DIZZY GILLESPIE • STAN GETZ • DAVE BRUBECK • JON HENDRICKS • COLEMAN HAWKINS • LALO SCHIFRIN • …

“João Gilberto’s first two albums made in Rio de Janeiro in 1958 gave Bossa Nova its birth certificate: misleading indolence, simplified samba rhythms, altereted chords, and a new way of placing the voice while shifting the rhythm on guitar. He gave jazzmen, record-producers and American radio a new musical language. Through the prism of their own codes, his contributions freed themselves from traditional rules to provide savoury new vitality to popular music, and the Bossa Nova spread throughout the world like a universal remedy.” Teca CALAZANS

ANTONIO CARLOS JOBIM - VINICIUS DE MORAES - JOÃO...

CHEGA DE SAUDADE 1959 - O AMOR, O SORRISO E A FLOR...

ROOTS OF BOSSA NOVA 1948-1957

THE FREMEAUX & ASSOCIES RECORDINGS 1994 -1996

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Chega de SaudadeDizzy GillepsieVinicius De Moraes00:10:101962

-

2DesafinadoStan GetzMendonca Newton00:05:521962

-

3Stompy Bossa NovaColeman HawkinsColeman Hawkins00:02:331962

-

4Bim BomStan Getz Big Band Bossa NovaJoao Gilberto00:04:331962

-

5Deve Ser AmorHerbie MannVinicius De Moraes00:04:141962

-

6Stairway To The StarsLaurindo AlmeidaMitchell Parish00:03:021962

-

7Influencia Do JazzHerbie MannCarlos Lyra00:05:441962

-

8ConsolacaoHerbie Mann00:04:241962

-

9CorcovadoJon HendricksAntonio Carlos Jobim00:02:081961

-

10Voce E EuJon HendricksCarlos Lyra00:03:081961

-

11SilviaLalo SchifrinLalo Schifrin00:03:131962

-

12One Note SambaGeorge ShearingNewton Mendonca00:02:481962

-

13Manha De CarnavalGeorge ShearingAntonio Maria00:02:201962

-

14InquietacaoLaurindo AlmeidaLaurindo Almeida00:03:061962

-

15The Color Of Her HairBud ShankLaurindo Almeida00:02:001959

-

16Se E Tarde Me PerdoaCal TjaderCarlos Lyra00:02:511962

-

17Vai QuererCal TjaderHianto De Almeida00:02:311962

-

18Chora Sua TristezaBob BrookmeyerLuvercy Fiorini00:04:131962

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Bossa Nova UsaDave Brubeck QuartetDave Brubeck00:02:281962

-

2Vento FrescoDave Brubeck QuartetDave Brubeck00:03:341962

-

3LamentoDave Brubeck QuartetDave Brubeck00:04:471962

-

4Samba De Uma Nota SoStan Getz Big Band Bossa NovaNewton Mendonca00:06:121962

-

5Recado Bossa Nova 1Zoot SimsLuis Antonio00:02:371962

-

6Rapaz De BemLalo SchifrinJohnny Alf00:02:351962

-

7On Note SambaHerbie MannNewton Mendonca00:03:261962

-

8Um Abraco No BonfaColeman HawkinsJoao Gilberto00:04:531962

-

9You And MeLalo SchifrinCarlos Lyra00:01:481962

-

10O PatoColeman Hawkins00:04:101962

-

11DesafinadoDizzy GillepsieNewton Mendonca00:03:211962

-

12CiumeSims ZootCarlos Lyra00:04:141962

-

13Amor Em PazMann HerbieVinicius De Moraes00:02:401962

-

14Speak LowAlmeida LaurindoOgden Nash00:02:231962

-

15LonelyShank BudLaurindo Almeida00:03:561959

-

16Velhos TemposRouse Charlie00:04:481960

-

17Lalo's Bossa NovaSchifrin LaloLalo Schifrin00:02:171962

-

18Chega De SaudadeHendricks JonVinicius De Moraes00:02:051961

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Cantando a orquestraZoot SimsCarlos Lyra00:04:111962

-

2Coracao sensivelDave Brubeck Quartet00:04:151962

-

3Irmao amigoDave Brubeck QuartetDave Brubeck00:03:241962

-

4E luxo soStan GetzAry Barroso00:03:441962

-

5Samba tristeStan GetzBaden Powell00:04:471962

-

6Outra vezJon HendricksAntonio Carlos Jobim00:01:581961

-

7DesafinadoHawkins ColemanNewton Mendonca00:05:491962

-

8InsensatezSchifrin Lalo00:02:231962

-

9ElizeteCal TjaderClare Fischer00:03:041962

-

10I remember youColeman HawkinsJ. Mercer00:04:001962

-

11O amor em pazJon HendricksVinicius De Moraes00:02:351961

-

12On note sambaColeman HawkinsNewton Mendonca00:06:001962

-

13MeditacaoCal TjaderNewton Mendonca00:03:341962

-

14Nao diga nadaCal TjaderNoacy Marcenes00:02:461962

-

15Samba de orfeuCharlie Rouse00:06:131960

-

16A felicidadeBob BrookmeyerVinicius De Moraes00:03:181962

-

17Coisa mais lindaJon HendricksVinicius De Moraes00:03:071961

-

18Maria ninguemZoot SimsCarlos Lyra00:02:381962

Bossa Nova FA5482

Bossa Nova

IN USA /1961-62

La Bossa Nova à Carnegie Hall

Le 21 novembre 1962, une caravane brésilienne vient planter ses tentes sur la scène de la mythique salle du Carnegie Hall. Après les années américaines de Carmen Miranda, qui était plus perçue comme une figure exotique de femme latine excentrique que comme une chanteuse talentueuse, il était rare de mettre la musique du Brésil en avant. Pourquoi cette réapparition sous les feux de la rampe ? La parution au Brésil des trois premiers LP de João Gilberto et le succès du film Orfeu Negro de Marcel Camus, palme d’or à Cannes en 1958, auraient ouvert les oreilles de certains aux compositions de luiz Bonfá (Manha de Carnaval, Samba de Orfeu) et d’Antonio Carlos Jobim (Samba de uma nota só, Desafinado, A Felicidade). Ce concert au Carnegie Hall vire à la soirée « people » de prestige où se mêlent acteurs en vue, chanteurs plébiscités et musiciens de jazz, même Miles Davis est présent dans le public. D’après Carlos Lyra, qui a toujours été un personnage très critique, cette nuit n’a pas tenu ses promesses ; ce fut confus : trop d’artistes pour trop peu de temps de présence en scène à défendre un répertoire. Il n’empêche, l’affiche était – du moins au regard de l’histoire – alléchante : Tom Jobim derrière son piano, Luiz Bonfa et João Gilberto côtoient Carlos Lyra, Oscar Castro Neves et son quartet, Sergio Mendes et son sextet, Roberto Menescal et Agostinho dos Santos, celui qui assurait les parties chantées du personnage principal dans le film Orfeu Negro. Pour qui veut en savoir plus, il est possible de se procurer l’enregistrement historique de cette soirée sur plusieurs catalogues.

Les préceptes de la Bossa Nova :

Qu’était la Bossa Nova pour susciter un tel engouement ou au moins une telle curiosité si peu de temps après son émergence au Brésil où elle commence à être reconnue sans y connaitre un grand succès commercial ? En quelques lignes, brossons les qualités novatrices de la Bossa Nova qui vont illuminer le paysage sonore par une évolution plus que par une révolution radicale: simplification du rythme du samba qui reste le terreau natif, écriture harmonique autour de belles mélodies intimistes, en jouant sur les accords alterés, paroles malicieuses, arrangements d’une simplicité raffinée, la guitare comme instrument central (João Gilberto fait sonner l’instrument en impulsant un rythme décalé qui bonifie la musique en lui donnant une dimension nouvelle). Et Aloysio de Oliveira - compositeur et futur directeur artistique des labels Odéon et Elenco - de souligner que si l’évolution donnée par Antonio Carlos Jobim a atteint l’harmonie et la mélodie, c’est bien João Gilberto qui lance les choses plus avant au plan du rythme. Il ajoute, à raison, que c’est cette mutation rythmique de la Bossa Nova qui a donné la possibilité aux étrangers de jouer le samba. : « Jusqu’à cette époque, précise t’il, il était impossible pour un nord-américain de jouer le samba parce qu’il existait un hiatus entre le temps fort caractéristique de la musique américaine qui correspond au temps faible brésilien ». La Bossa Nova - dont on date l’éclosion à la parution du 78 Tours de João Gilberto, Chega de saudade en juillet 1958 - est avant tout l’expression de la sensibilité artistique de la bourgeoisie de la Zona Sul de Rio (Copacabana, Ipanema et Leblon) et elle coule comme un mouvement né au fil de l’eau et qui s’éteindra peu à peu vers 1965 au Brésil même. Les acteurs essentiels de cette période des années 1958 à 1962 qui vont instiller un nouveau souffle à la musique populaire sont vite circonscrits autour de la signature de la « sainte trinité » sans qui rien ne serait advenu, à savoir Antonio Carlos Jobim, Vinicius de Moraes et João Gilberto, à laquelle on peut ajouter les noms de Carlos Lyra, de Roberto Menescal et on ne manquera pas de retrouver ces noms tout au long du répertoire repris par les jazzmen. Le concert à Carnegie Hall n’est qu’une suite logique à la fascination que porte un petit cercle fermé constitué de musiciens, de programmateurs de radio comme Felix Grant, de producteurs de disques et de critiques de jazz qui craquent à l’écoute des enregistrements réalisés par João Gilberto.

Les Jazzmen Précurseurs :

A la fin des années cinquante, quelques rares musiciens américains, parce qu’ils avaient vécu un temps dans le pays pour poursuivre des études musicologiques ou parce qu’ils y avaient effectué des tournées, s’étaient épris de la musique brésilienne. Charlie Byrd - qui deviendra un « passeur » représentatif de ce que Baden Powell qualifiera de « ketchup bossa nova » - ne pouvait qu’être affolé par la dextérité de guitaristes comme Luiz Bonfá, Durval Ferreira ou João Gilberto. De son côté, Clare Fisher, personnage plus fin, pianiste mais aussi arrangeur talentueux, qui avait déjà vécu plusieurs mois au Mexique, s’était installé un temps au Brésil où il a su capturer la dimension rythmique, mélodique et harmonique de cette musique encore en gestation. Il en viendra même à composer plusieurs titres, dont Elizete en l’honneur d’Elizete Cardoso, une chanteuse tout en raffinement et une des belles voix de l’époque qui anticipe un peu la Bossa Nova sans en être toutefois une des icônes (elle allait enregistrer en mars 1958 l’album Canção do amor demais ; paroles de Vinicius de Moraes, compositions et arrangements d’Antonio Carlos Jobim et, sur quelques plages, la guitare de João Gilberto). Ajoutons qu’il est aussi un musicien de grand talent dont on ne souligne pas suffisamment les qualités et son appétence précoce pour la musique brésilienne : Bud Shank. Homme de la côte Ouest des Etats-Unis, familier de Gerry Mulligan, de Bob Cooper et de Chico Hamilton, donc sensible à une certaine forme d’écriture, Bud Shank, en devenant un complice régulier du guitariste Laurindo Almeida qui résidait à Los Angeles, s’était si bien frotté, tôt dans les années cinquante, aux harmonies et aux rythmes de la musique brésilienne qu’on pourrait écrire qu’il a, avec son compère, anticipé l’éclosion de la Bossa Nova ; les thèmes choisis et l’interprétation ne relèvent certes pas explicitement du genre mais l’esprit est là, la sensualité câline en sus. Et juste retour des choses, où chacun boit dans le verre de l’autre, il est vrai aussi qu’un des thèmes majeurs de la Bossa Nova naissante s’intitule : Influência do jazz, comme quoi la musique américaine fut toujours et partout influente dans le monde occidental après la seconde guerre mondiale.

Un Bon Filon

Toujours à l’affut de nouveautés, le show business américain avait fleuré un bon filon à exploiter : une musique plaisante, cousine proche du jazz, dont les mélodies, empreintes d’une apparente simplicité, imprègnent la mémoire et qui peuvent se siffler, le matin, quand on se rase dans sa salle de bains. Ce fut une aubaine pour nombre de jazzmen mais que de mauvais disques de commande, sans charge affective d’implication, furent enregistrés sous le label « Bossa Nova » pour laisser accroire qu’on était dans le vent. Il n’en reste pas moins une vérité : c’est par l’Amérique que la Bossa Nova a conquis le monde, jusqu’à en être dénaturée avec le temps en musique d’ascenseur ou de piano-bar. The Girl from Ipanema - le fameux disque de Stan Getz où il est accompagné par João Gilberto, Antonio Carlos Jobim, Astrud Gilberto et Milton Banana, resté un temps dans les tiroirs des producteurs - participe de cette émancipation de la Bossa Nova en terre étatsunienne et son incroyable succès de la prophylaxie du genre dans le monde entier. Le savoir faire américain et la force d’impact capitalistique a parfois du bon.

Une autre lecture :

C’est parce qu’ils furent séduits par les disques de João Gilberto (une manière différente et novatrice de poser la voix, de jouer de la guitare acoustique, une fausse indolence, une autre combinaison sonore entre guitare et batterie, de superbes mélodies sur arrangements sophistiqués), que les producteurs et les jazzmen se précipitèrent sur les principales compositions de la Bossa Nova naissante sur une période charnière courte de deux à trois ans. Cela donne une explication à un répertoire étrangement redondant et réduit à quelques titres comme Desafinado, Samba de uma nota só, Chega de Saudade, Ce fut d’ailleurs, pour nous les auteurs de cette anthologie, une contrainte pour le choix des titres à retenir et on ne coupera donc pas à trois versions de Desafinado mais plusieurs motivations poussaient à ne pas les écarter: la qualité intrinsèque des interprètes (Coleman Hawkins, Stan Getz, Dizzy Gillespie), l’originalité de la composition même ancrée dans toutes les mémoires et la dimension référentielle que représente le titre Desafinado dont la traduction serait : jouer ou chanter faux (pour beaucoup, à l’époque, chanter une Bossa Nova, c’était avant tout susurrer, avec un filet de voix à la lisière de la justesse). Rares sont finalement ceux qui ont daigné composer dans l’optique Bossa Nova : qui mis à part Dave Brubeck, Gary Mac Farland et Clare Fisher ?

Deux approches :

On notera dans la sélection de notre anthologie deux approches du phénomène interprétatif de la Bossa Nova : celle d’un Dave Brubeck qui compose dans l’esprit Bossa Nova ou celle d’un Coleman Hawkins qui est au meilleur lorsqu’il reste un jazzman interprétant Stumpy Bossa Nova, une de ses compositions et, à l’opposé, celle du soliste qui s’entoure de brésiliens comme le fit Herbie Mann, accompagné à Rio même, par les meilleurs musiciens locaux (Jobim, Baden Powell, Dom Um Romão, Luis Carlos Vinhas…) qui impulsent une véritable rythmique native. Le plus souvent, dans les enregistrements « américains » de la Bossa Nova du début des années 60, l’approche rythmique est donnée par des percussionnistes originaires des caraïbes, qui tout en respectant la « marcation » de la Bossa Nova - surtout dans les introductions - dérivent insensiblement vers un déhanchement qui leur est plus naturel quoique un peu éloigné de la syncope flottante spécifique de la musique brésilienne. (Ainsi, par exemple, certaines prises des LP de Charlie Rouse ou de Cal Tjader sonnent vraiment très antillaises). Au final, les musiciens qui emportent l’adhésion sont ceux qui empoignent les thèmes de la Bossa Nova comme s’ils étaient des standards des grandes comédies musicales de Broadway, c’est-à-dire comme des rampes de lancement idéales pour improviser selon leur esthétique propre. Il en est ainsi chez Coleman Hawkins, Zoot Sims, Stan Getz ou Dizzy Gillespie dont la générosité musicale leur fait enjamber toutes les frontières stylistiques pour n’être jamais qu’eux – mêmes, loin de la médiocrité et du kitsch que la Bossa Nova ne supporte pas, elle qui est toujours en équilibre instable entre la brillance d’une goutte de rosée et les rides de la « saudade ». Si après plus d’un demi-siècle, il est toujours plaisant d’écouter la lecture jazzistique de la Bossa Nova, c’est que les meilleurs musiciens américains s’étaient appropriés ce nouveau langage, loin de tout plagiat. C’est parce qu’ils imprimèrent leur identité que la Bossa Nova aux Etats-Unis a une autre saveur, saveur qui permit à la Bossa Nova de conquérir le monde et de revenir auréolée de la reconnaissance américaine en sa terre natale.

Du côté des critiques musicaux :

A la lecture de la critique que donne Jacques Réda, dans un numéro de Jazz Magazine, à la parution du disque de Coleman Hawkins (« Quel métier déprimant ! Il faut arriver à penser quelque chose de n’importe quoi. De la bossa nova par exemple… Tout bien considéré d’ailleurs, et si l’on admet que ces rythmes samboïdes ne peuvent avoir de point commun avec le jazz qu’à partir d’un certain degré de folie, il faut reconnaître que le vieux Bean se tire remarquablement d’affaire… Sa sonorité elle –même s’est épurée, s’est faite intérieure, confidentielle sans rien perdre de sa chaleur naturelle et de sa profondeur. Tout cela compense à peu près une inévitable monotonie ») et de la notule sur Stan Getz (« le succès qu’a connu le musicien avec ses disques autour de la Bossa Nova ont occulté l’immense musicien qu’il était ») du « Dictionnaire du Jazz » de la collection Bouquins, on peut vérifier que les jazzophiles ont montré plus que de la réticence vis-à-vis de la musique brésilienne, une posture qu’il ne serait pas injuste de qualifier de colonialiste. Les musiciens brésiliens ne sauraient-ils pas improviser, ne sauraient-ils pas composer de belles mélodies et harmoniser avec délicatesse, ne seraient-ils que des instrumentistes de seconde zone ? Baden Powell – qui n’avait jamais que vingt deux ans en 1962 lorsqu’il enregistre avec Herbie Mann – n’est-il pas plus innovateur qu’un Charlie Byrd, ses compositions même ne sont - elles pas d’une belle tenue? A l’écoute des plages enregistrées par Herbie Mann, à Rio même, ne peut-on prendre la mesure du swing imparable des musiciens brésiliens, du lien étonnant qui se tisse entre guitare, piano, basse et batterie et de la fabuleuse pulsation - qui ne ressemble en rien à un drumming jazz - qu’introduisent des percussionniste comme Dom Um Romão ou Juquinha ?

Petites biographies des uns et des autres :

Coleman Hawkins (1904-1969). Celui qu’on appelait « Bean » (haricot) ou « Hawk » (le faucon), était un personnage solitaire toujours à l’écoute de l’histoire en marche : sans jamais s’écarter des pairs de sa génération, il s’est toujours entouré de jeunes musiciens novateurs, entre autres au temps de la gestation du Be Bop. Fut-il séduit par les timbres, les subtilités harmoniques et la fausse indolence de la Bossa Nova, lui qui avait étudié le violoncelle et le piano à l’adolescence avant d’emboucher un saxophone ténor ? Celui que l’on peut considérer comme le premier saxophoniste d’envergure de la longue histoire du jazz avait débuté sa carrière dans l’orchestre de Fletcher Henderson et tout au long d’une carrière de près de cinquante ans, il est demeuré un remarquable interprète de ballade, reconnaissable pour sa sonorité souple et lyrique, approche qui collait bien aux atours de la Bossa Nova, genre vers lequel il ne semble pas être revenu après l’enregistrement du LP Coleman Hawkins plays Bossa Nova and Jazz Samba ».

Dizzy Gillespie (1917-1993). Qui ne connait pas cette trompette coudée et ses bajoues gonflées par le souffle ? C’est que John Birks « Dizzy » Gillespie, musicien à la générosité musicale et humaine doté d’un humour délicieux, avait une présence magnétique, le sens de la posture exubérante jamais inepte et de la mise en scène du son. Ayant ouvert les horizons du jazz à la musique cubaine, il ne pouvait qu’être sensible à toutes les musiques latines. Il se sera entouré du percussionniste cubain Chano Pozzo, du pianiste argentin Lalo Schifrin et, plus tard, du saxophoniste cubain Paquito d’Rivera. Il pimentait sa lecture de la Bossa Nova d’un sel samba.

Stan Getz (1927-1991). De son vrai nom Stanley Gayetzetsky, Stan Getz était un personnage bien plus complexe que ne le laisserait accroire son raffinement et sa constante élégance. Cet improvisateur de premier plan compte parmi les « géants » du jazz bien que le succès phénoménal qu’il ait connu avec ses disques dévolus à la Bossa Nova l’ait desservi auprès de certains jazzophiles. La voluptueuse qualité de son timbre, son savant abandon rythmique, sa virilité tout en nuances se marient idéalement avec les codes de la Bossa Nova.

Herbie Mann (1930-2003). Multi-instrumentiste sans être un improvisateur de premier plan, Herbie Mann a surtout une réputation de soliste habile à la flûte. Il fut un précurseur de la world music avant de s’adonner au jazz fusion en fin de carrière.

Bud Shank (1926-2009). Clifford Shank est un musicien raffiné ayant étudié la composition et l’arrangement avec Shorty Rogers dans les années 40 puis mené un duo flûte / hautbois avec Bob Cooper et participé au LA Four (avec le guitariste brésilien Laurindo Almeida, le contrebassiste Ray Brown et le batteur Shelly Manne). Son jeu délicat se mariait parfaitement à celui de Laurindo Almeida avec qui il enregistre beaucoup dans les années 50/60. Il était aussi très lié au pianiste brésilien João Donato (un LP en 1965 réalisé aux USA et un album en duo au Brésil à la fin de sa vie - disponible chez Biscoito Fino).

Laurindo Almeida (1917-1995). Né à São Paulo, sa mère était une pianiste classique et concertiste et il était venu aux Etats-Unis pour une tournée avec la violoniste classique Elisabeth Waldo avant de bifurquer vers le jazz en rejoignant l’orchestre de Stan Kenton. Il se produit seul ou avec Bud Shank, tourne avec le Modern Jazz Quartet en 1963 (un magnifique disque Blue Note), enregistre avec Stan Getz et crée L.A Four. Il fut aussi un compositeur familier des studios de cinéma et de télévision.

Jon Hendricks (16 septembre 1921). Ce fils de pasteur et enfant d’une famille nombreuse est un chanteur qui posera des paroles sur les solos des musiciens de jazz. Il faut absolument écouter la version inouïe du Freddie Freeloader, le thème du quintet de Miles Davis, où les autres voix sont celles de George Benson, d’Al Jarreau et de Bobby Mac Ferrin (Denon Records, CY-76302). Ses premiers succès se firent au sein du Trio Lambert / Hendricks / Ross. Pour se familiariser avec le langage de la Bossa Nova, John Hendricks est allé souvent chez Laurindo Almeida pour écouter les disques de João Gilberto et se faire traduire les paroles. Contrairement à Sinatra dont le phrasé « allonge » les notes dans ses versions des chansons de Jobim, Hendricks, lui, s’en tient intelligemment à la simplicité minimaliste qui caractérise le langage de la Bossa Nova. Dans son disque, les arrangements de Johnny Mandel sont de pures adaptations des orchestrations écrites par Antonio Carlos Jobim. Cette approche explique la réussite musicale qui se dévoile explicitement comme un révérence au talent de João Gilberto.

Lalo Schifrin (1932). Ce pianiste, compositeur et arrangeur argentin, fils d’un chef d’orchestre classique, est passé par le conservatoire de Paris avant de se rendre aux USA en 1958 pour être le directeur musical de Dizzy Gillespie et de Quincy Jones. Ses partitions pour le cinéma et la télévision sont renommées : Mannix, Bulitt, Mission Impossible, Dirty Harry, Starsky & Hutch, entre autres.

Cal Tjader (1925 -1982). Ce fils d’une pianiste et d’un acteur aimait les musiques d’inspiration latine où il met en évidence son jeu de vibraphoniste. Il était passé un temps par l’Octet de Dave Brubeck et le quintet de George Shearing, ce qui n’est nullement anodin.

Dave Brubeck (1920-2012). Ce compositeur et pianiste érudit (cours auprès de Schoenberg et de Darius Milhaud), tout au long de sa longue vie, fut mal aimé des critiques mais adopté par un large public dans le monde entier. Ses compositions les plus fameuses Take Five, Blue Rondo A La Turk , Three To Get Ready, les deux dernières seront adaptées par Claude Nougaro sous les titres : A bout de Souffle et Le Jazz et la java, malgré les recherches formelles sur les rythmes restent gravées dans les mémoires. Le quartet qu’il a dirigé de 1951 à 1968 mettait en valeur le merveilleux saxophoniste Paul Desmond ainsi qu’Eugene Wright à la contrebasse et Joe Morello à la batterie.

Zoot Sims (1925-1985). La réputation du clarinettiste, sax ténor et alto John Haley Sims est celle d’être le plus swinguant et le plus charnel des « Four brothers » de l’orchestre de Woody Herman. Il est un des musiciens préférés de notre confrère Alain Tercinet

Charlie Rouse (1924-1998). Être passé par les orchestres de Basie et d’Ellington ainsi que dans le quartet de Monk de 1959 à 1970 indique le niveau d’excellence de ce saxophoniste ténor.

Antonio Carlos Jobim (1927-1994). Si l’aéroport international de Rio de Janeiro s’appelle « aéroport Antonio Carlos Jobim », c’est que Tom Jobim fut le plus grand musicien brésilien de la seconde moitié du siècle passé. Pianiste économe au jeu immédiatement identifiable, il n’est venu au chant que vers 1962 (« je ne suis pas chanteur, je chante mes chansons » m’avait-il dit, lors d’une interview lors de son dernier concert à Paris en 1986 mais ses interprétations ne manquent pas d’un charme bien en phase avec la Bossa Nova). Avec son ami d’enfance Newton Mendoça, orphelin de père comme lui, il a composé à deux mains Desafinado, Meditação, Samba de uma nota só, Insensatez excusez du peu. Il est aussi l’auteur de Garota de Ipanema (The Girl From Ipanema) et de Águas de Março. Sensible à l’écologie avant que ce soit devenu du « politiquement correct », l’homme était affable, charmant et d’une intelligence subtile. Ses relations avec João Gilberto furent parfois houleuses.

João Gilberto (né en 1931) : il y a un mythe João Gilberto. Sa musique est le fruit d’un long travail de perfectionniste pour trouver la hauteur idéale du son de la batterie et sa pulsation afin que rien n’entrave la fusion entre la voix intimiste et la « batida » de sa guitare. Voir sur scène ce monstre sacré - ce qui est toujours anxiogène pour le spectateur qui ne sait jamais ce qui va advenir - est un enchantement musical. Il court un nombre incroyable d’anecdotes savoureuses sur ce personnage capricieux en costume cravate de fonctionnaire.

Baden Powell (1937- 2000). Il était beau d’entendre Baden Powell de Aquino (de son nom de famille) parler avec un profond respect et beaucoup d’amour de son professeur de guitare Jayme Florence / Meira. Dans un pays qui ne manquait pas de guitaristes de grand talent, Baden Powell est apparu très jeune comme un rénovateur de l’instrument en imposant une pulsation nouvelle par son jeu de pouce. Ses titres de gloire : Berimbau, Samba Triste, les afro-sambas. Ses paroliers ont pour nom Vinicius de Moraes et Paulo César Pinheiro. C’était un grand créateur.

Carlos Lyra (né en 1936). Issu d’une famille de musiciens, il s’était rapproché du parolier Ronaldo Boscoli avant de s’étriper avec lui lorsqu’il a voulu donner, lui homme de gauche, une dimension plus sociale et politique à ses chansons. Il a tourné aux USA et au Japon avec Stan Getz et a enregistré un disque avec Paul Winter. Il est l’auteur, entre autres, de Maria Ninguém que Jackie Kennedy appréciait parait-il, de Se é tarde me perdoa et de Lobo Bobo.

Roberto Menescal (né en 1937) : ce guitariste et producteur, amateur de pêche sous-marine, a composé O Barquinho qui reste un des grands succès de la Bossa Nova. Il n’appartient pas à la même génération que Tom Jobim qui était plus âgé et il était un ami proche de la muse de la Bossa Nova : la chanteuse Nara Leão.

Teca Calazans et Philippe Lesage

© 2015 Frémeaux & Associés

BOSSA NOVA IN THE USA

Bossa Nova at Carnegie Hall

On November 21st 1962 a Brazilian caravan raised its tents on the legendary stage of Carnegie Hall. After Carmen Miranda’s American years—she was perceived more as an eccentric symbol of the exotic Latin American female, rather than as a singer of talent—it was rare to devote the stage to the music of Brazil. So, why this reappearance in the limelight? Brazil had released the first three albums by João Gilberto on LPs, and the success of Marcel Camus’ film Orfeu Negro (which won the 1958 Palme d’Or Award at the Cannes Film Festival) had probably opened

ears to the compositions of Luiz Bonfá (Manha de Carnaval, Samba de Orfeu) and Antonio Carlos Jobim (Samba de uma nota só, Desafinado, A Felicidade). That November concert at Carnegie Hall turned into a tabloid event, with famous actors mingling with singers and jazz musicians in the audience, and even Miles Davis was there. According to Carlos Lyra—always someone with a critical eye—the night didn’t live up to its reputation: the whole thing was confused, with too many artists to do justice to the music, and not enough stage-time in which

to do it… Even so, the bill made mouths water, historically speaking, at least: Tom Jobim seated at the piano, Luiz Bonfá and João Gilberto alongside Carlos Lyra, Oscar Castro Neves and his quartet, Sergio Mendes and his sextet, Roberto Menescal, and Agostinho dos Santos, the singer whose voice had dubbed the male lead in Orfeu Negro. For those who would like to know more, recordings of that historic evening appear in several catalogues.

The precepts of Bossa Nova

What was this Bossa Nova that aroused so much enthusiasm, or at least curiosity, so quickly after its emergence in Brazil? At home it was just starting to become known, and no commercial hits had yet confirmed it. Here, in a few lines, are the innovative qualities with which Bossa Nova illuminated the soundscape through evolution rather than any radical revolution: a simplified samba rhythm that remained set in its native soil; harmonic composing around beautiful, intimist melodies which played on alter-eted chords; impish lyrics; arrangements of refined simplicity; and the guitar as a central instrument (João Gilberto made the instrument ring by giving it an offbeat impulse, and the music sounded even better with the addition of this new dimension.) Aloysio de Oliveira, the composer and future Artistic Director of the Odéon and Elenco labels, pointed out that while the evolution brought by Antonio Carlos Jobim touched on harmony and melody, it was indeed João Gilberto who took the rhythm further. De Oliveira rightly added that it was this rhythmical mutation in the Bossa Nova which enabled foreigners to play sambas, saying, “Until that period, it was impossible for North-Americans to play samba because there was a pause between the characteristic markings of the beat in American music which corresponded to the Brazilian offbeat.” The Bossa Nova—which blossomed into view with João Gilberto’s 78rpm record Chega de saudade in July 1958—is above all the expression of artistic sensibilities which reigned in the bourgeoisie living in the Zona Sul region of Rio de Janeiro (Copacabana, Ipanema and Leblon), and as a movement it drifted along, like a current in the water, until it gradually died out in Brazil towards 1965. The essential players in this period, those of the years 1958-1962, would breathe new life into popular music, and they were quickly referred to as the founding “Holy Trinity”—those without whom nothing would have occurred at all—of Antonio Carlos Jobim, Vinicius de Moraes and João Gilberto, to whom can be added the names of Carlos Lyra and Roberto Menescal (whose signatures appear throughout the repertoire picked up by jazz.) The Carnegie Hall concert was merely the logical sequel to the fascination of a small, closed circle—musicians, radio programmers such as Felix Grant, record producers and jazz critics—left in amazement by the recordings of João Gilberto.

Jazz precursors

At the end of the Fifties there were a few, rare American musicians who were smitten by the music of Brazil after spending time there either studying music or touring. Charlie Byrd, for example (who became a “ferryman” representing what Baden Powell came to call “ketchup bossa nova”), couldn’t help being amazed by the dexterity of such guitarists as Luiz Bonfá, Durval Ferreira or João Gilberto. As for pianist Clare Fisher, a more elegant character and also a talented arranger, he had already lived in Mexico for several months and had gone to Brazil, where he succeeded in capturing the rhythmical, melodic and harmonic dimensions of this music that was still in gestation. He would even compose several titles, among them Elizete which he wrote in tribute to Elizete Cardoso, an extremely refined singer and one of the period’s beautiful voices anticipating Bossa Nova, although she was never one of its icons (in March 1958 she recorded the album Canção do amor demais, with lyrics by Vinicius de Moraes, compo-sitions and arrangements from Antonio Carlos Jobim and, on a few tracks, the guitar of João Gilberto). Another precursor was a highly talented musician whose qualities and precocious taste for Brazilian music shouldn’t be underestimated: Bud Shank. An American musician who’d worked on the West Coast with Gerry Mulligan, Bob Cooper and Chico Hamilton, Bud Shank had quite a feeling for a particular style of composing; he became a regular partner of guitarist Laurindo Almeida who lived in Los Angeles and, having become so familiar with the harmonies and rhythms of Brazilian music early in the Fifties, both Shank and Almeida can be said to have heralded Bossa Nova. The themes Bud chose, and his performances, are not explicit references to the genre, of course, but the spirit is certainly there, accompanied by a caressing sensuality. And it’s also true that something like the reverse also happened, if you take one of the newborn Bossa Nova’s major titles called Influência do jazz: the one influenced the other, and American music was certainly everywhere in the western world after World War II.

A goldmine

Always on the lookout for novelty, American show-business had a nose for exploring a seam: this was pleasant music that had jazz for a cousin, and its melodies stamped with an apparently simple disguise were instantly memorable; they could be hummed every morning by people shaving… So Bossa Nova was a goldmine for many jazzmen, but there were so many (bad) records made to order under the “Bossa Nova” appellation, with little or no personal invol-vement on the part of the musicians. They were made for appearances’ sake, to avoid the “has been” notion. But at least one thing was true: it was via America that Bossa Nova conquered the world, until it became lost after a time and became a source of sound for elevators and cocktail-rooms. The Girl from Ipanema-

—the famous record by Stan Getz (accompanied by João Gilberto, Antonio Carlos Jobim, Astrud Gilberto and Milton Banana) which stayed in the producers’ bottom drawer for so long—was part of the eman-cipation of Bossa Nova on American soil, and its success was a preventive cure which spread throu-ghout the world. Sometimes, good things could come from American savoir-faire and the impact of capitalism.

Another reading

It is because they were seduced by the records of João Gilberto (a new, different way of placing the voice, playing acoustic guitar, misleading indolence, another sound-combination between guitar and drums, superb melodies with sophisticated arrangements…) that producers and jazzmen literally threw themselves at the major compositions coming out of the nascent Bossa Nova style within an extremely short two or three year period. This would explain why the repertoire seems so strangely redundant, and reduced to a few titles like Desafinado, Samba de uma nota só and Chega de Saudade. When we were putting this anthology together, it was also something of a handicap when choosing the titles to be included, and so here we have three different versions of Desafinado for example. But there are several reasons to justify their appearance in this set: the intrinsic quality of the artists (Coleman Hawkins, Stan Getz, Dizzy Gillespie); the composition’s originality, even if it does belong to the collective memory; and finally, the sheer dimension of the title as a reference. Desafinado translates as something like “playing or singing false” (for many at the time, singing a Bossa Nova song meant above all murmuring the song, with just a trickle of a voice sounding almost out of tune.) And finally, rare were those who deigned to compose in the Bossa vein; apart from Dave Brubeck, Gary McFarland and Clare Fisher, how many can you name?

Two approaches

The recordings chosen here show two ways of interpreting the Bossa Nova phenomenon, that of a Dave Brubeck (whose manner of composing corresponded to the spirit of the genre) or a Coleman Hawkins (who was at his best as a jazz musician when playing Stumpy Bossa Nova, one of his own compo-sitions), and, at the opposite extreme, the approach of a soloist who chose to play with Brazilian musicians, as Herbie Mann did in Rio, accompanied by the best local instrumentalists such as Jobim, Baden Powell, Dom Um Romão or Luis Carlos Vinhas, and who gave a genuinely native impulse to the rhythm. In “Ame-rican” Bossa Nova records of the early Sixties, the approach to rhythm was most often provided by percussionists from the Caribbean who, while respecting the “accent” of the Bossa Nova beat—especially in the introductions—drifted imperceptibly into a natural swaying that came more easily to them, even if it was still distant from the “floating” synco-pation specific to Brazilian music. (Some of the tracks on LPs by Charlie Rouse or Cal Tjader really do sound Caribbean for example.) In the end, the musicians who won favour with a wide audience were those who tackled Bossa Nova themes as though they were standards from great Broadway musicals; in other words, as if they were ideal springboards from which to improvise in their own styles. This was the case with Coleman Hawkins, Zoot Sims, Stan Getz or Dizzy Gillespie, whose musical generosity gave them wings to fly over stylistic borders while remaining them-selves, far from mediocrity and kitsch… which were things that Bossa Nova couldn’t tolerate, even though the music could be said to maintain an unstable imbalance somewhere between sparkling droplets of dew and the wrinkled lines of saudade. After more than a half century, if there is still pleasure to be had from listening to jazz readings of Bossa Nova, it is because the best musicians in America appropriated this new language without ever turning into plagiarists. They left the imprint of their own identity on the genre, and this is why Bossa Nova had a different savour in the United States, one which allowed the genre to conquer the world and return home covered in the glory of American recognition.

The music critics

This is taken from Jacques Réda’s review of a Coleman Hawkins album for the review “Jazz Magazine”: “What a depressing way to make a living! You have to find a way to say something about nothing; about bossa nova for example… All things considered, by the way, and if you admit that jazz and sambaed rhythms like these can only have something in common if a certain degree of madness is involved, then you have to say that old Bean pulls it off remarkably well here… His sound has been pared down and interiorized, and it’s become confidential without losing any of its natural warmth and profoundness. All of which more or less compen-sates for inevitable monotony…” And this one comes from the entry in the “Dictionnaire du Jazz” for Stan Getz: “The hits he had with his Bossa Nova records blinded us as to how immense a musician he was.” So you can see that jazz fans have been more than reticent when it comes to Brazilian music, a pose that it wouldn’t be unfair to call “colonialist”. Could it be that Brazilian musicians were incapable of improvising? Didn’t they know how to write beautiful melodies and delicate harmonies, even if they were second-rate instrumentalists? But wasn’t Baden Powell—he was only 22 when he recorded with Herbie Mann in 1962—more of an innovator than a Charlie Byrd, for example? Isn’t there a beautiful quality in his compositions? Listening to the tracks recorded by Herbie Mann in Rio, you can sense the relentless swing of the Brazilian musicians, and the astounding rapports created between guitar, piano, bass and drums, not to mention the fabulous pulse—which has nothing to do with jazz drumming—set up by percussionists Dom Um Romão or Juquinha.

Biographical notes on those involved

Coleman Hawkins (1904-1969) had two nicknames, “Bean” or “Hawk”, and he was a solitary character who always had an ear for history in the making. He never strayed far from his peers in the same gene-ration, and always had innovative young musicians at his side, notably in periods like the beginnings of bebop. Was it the timbres, the harmonic subtleties in the misleadingly lazy Bossa Nova which so seduced this former student of the cello and piano before he ever put a tenor saxophone to his mouth? Hawkins can be considered the first major saxophonist in the long history of jazz, beginning in the orchestra of Fletcher Henderson; throughout a career of almost fifty years, he remained a remarkable ballad player and was recognized for his flexible, lyrical sound; his playing was well-suited to the finery of Bossa Nova, even though he hardly returned to the genre after making the album Coleman Hawkins plays Bossa Nova and Jazz Samba.

Dizzy Gillespie (1917-1993). Who hasn’t heard of his trumpet pointing up at an angle, his cheeks puffed up like balloons? John Birks “Dizzy” Gillespie, a musician who was generous both musically and personally, was gifted with a delicious sense of humour and had a magnetic presence; he literally staged the sounds he produced, with a talent for exuberant posturing that was never inept. After opening up jazz horizons to Cuban music, he couldn’t remain impervious to every kind of Latin music, and played with the Cuban percussionist Chano Pozo, the Argentinean pianist

Lalo Schifrin and, later, Cuban saxophonist Paquito d’Rivera. His readings of Bossa Nova were peppered with savoury samba.

Stan Getz (1927-1991). Stanley Gayetzetsky, aka Stan Getz, was a much more complex character than his constant elegance would lead you to believe. A first-rate improviser, he was one of the few to be numbered as “jazz giants”, even though the phenomenal success he enjoyed with his Bossa Nova-themed records did him a disservice with some jazz fans. The voluptuous quality of his timbre, his skilful rhythmical abandon and his highly-nuanced virility formed an ideal marriage with the codes of Bossa Nova.

Herbie Mann (1930-2003). A multi-instrumentalist although not a top-ranking improviser, Herbie Mann had a special reputation as a solo flautist; he was a precursor in world music before moving towards jazz fusion at the end of his career.

Bud Shank (1926-2009). Clifford “Bud” Shank was an elegant saxophonist who studied composition and arrangement with Shorty Rogers in the Forties before forming a flute & oboe duo with Bob Cooper and then joining the L.A. Four group (with Brazilian guitarist Laurindo Almeida, bassist Ray Brown and drummer Shelly Manne). His delicate playing perfectly married the guitar of Laurindo Almeida, with whom he recorded a great deal in the Fifties and Sixties. He was also quite close to Brazilian pianist João Donato, with whom he made an LP in the USA in 1965, and a duo album in Brazil at the end of his life (issued on the Biscoito Fino label).

Laurindo Almeida (1917-1995). He was born in São Paulo, and his mother was a classical concert pianist. He visited the USA on tour with classical violinist Elisabeth Waldo before moving into jazz when he joined the Stan Kenton Orchestra. He appeared solo or with Bud Shank, toured with the Modern Jazz Quartet in 1963 (recording a magnificent album for Blue Note), worked with Stan Getz, and founded the L.A. Four. He was also a composer working regularly in films and television.

Jon Hendricks (born September 16th 1921). The son of a preacher and one of many children, Jon Hendricks is known mainly for singing lyrics to solos played by jazz musicians. You absolutely have to listen to his incredible version of Freddie Freeloader, the theme by the Miles Davis Quintet, where the other voices are those of George Benson, Al Jarreau and Bobby McFerrin (Denon Records, CY-76302). He had his first hits as part of the Lambert, Hendricks & Ross Trio. To familiarize himself with the language of Bossa Nova, Jon Hendricks often went over to Laurindo Almeida’s house to listen to records by João Gilberto, with Almeida translating the words for him. Unlike Sinatra, whose phrasing “drew out” the notes in his own versions of Jobim songs, Hendricks intelligently kept to the minimalist simplicity which characterizes the language of Bossa Nova. In his record, the arrangements by Johnny Mandel are pure adaptations of the orchestrations written by Antonio Carlos Jobim, an approach which explains the musical achievement: it unfolds as an explicit reference to the talent of João Gilberto.

Lalo Schifrin (1932). An Argentinean pianist, composer and arranger, son of a classical conductor, who studied at the Conservatoire in Paris before moving to America in 1958 as Musical Director for Dizzy Gillespie and Quincy Jones. Among his work are some of the most famous scores ever written for films and television, among them Mannix, Bullitt, Mission Impossible, Dirty Harry or Starsky & Hutch.

Cal Tjader (1925 -1982). His mother was a pianist and his father an actor. Tjader loved Latin music, which enabled him to show his excellent vibraphone-playing. Among those he played with were Dave Brubeck (his Octet) and George Shearing (the famous Quintet), and you can’t have better references than those.

Dave Brubeck (1920-2012). An erudite composer and pianist (he studied under Schoenberg and Darius Milhaud), Brubeck was never a favourite with critics but enjoyed a worldwide following, and his most famous compositions, among them Take Five, Blue Rondo A La Turk and Three To Get Ready, will always be remembered even if they were the results of the pianist’s formal research into rhythm. The quartet he led from 1951 to 1968 featured the wonderful saxophonist Paul Desmond, together with Eugene Wright on double bass and the drummer Joe Morello.

Zoot Sims (1925-1985). John Haley “Zoot” Sims played the clarinet and alto and tenor saxophones, and enjoyed a reputation as the most swinging, most physical member of the so-called “Four brothers” in Woody Herman’s orchestra. Our colleague Alain Tercinet numbers Sims among his favourite musicians.

Charlie Rouse (1924-1998) played tenor saxophone with the orchestras of Count Basie and Duke Ellington, and was a member of the Thelonious Monk Quartet from 1959 to 1970. Those references alone indicate his excellence.

Antonio Carlos Jobim (1927-1994). The international airport which serves Rio de Janeiro is named after him because he was the greatest Brazilian musician in the second half of the last century. A pianist who played with economy, his work was immediately recognizable, but he didn’t turn to singing until around 1962. In an interview he gave at his last concert in Paris in 1986, he said, “I’m not a singer; I sing my songs”, but his vocals always had a certain charm that was well-suited to Bossa Nova. Together with his childhood friend Newton Mendoça, another orphan raised without a father, he co-wrote the titles Desafinado, Meditação, Samba de uma nota só and Insensatez (to name only four…) but also authored Garota de Ipanema (The Girl From Ipanema) and Águas de Março…. An ecologist before his time, Jobim was affable, charming, intelligent and subtle, not that this prevented him from a sometimes stormy association with João Gilberto.

João Gilberto (born 1931). João Gilberto is a legend. His music is the fruit of a perfectionist capable of spending hours working to achieve the ideal volume and beat of a drum so that nothing would obstruct the fusion of intimist voice with the batida rhythm imprinted by his guitar. Seeing this immense giant onstage—always a source of apprehension for the spectator who never knows what to expect next—is nothing short of a musical enchantment. And he’s also a legend due to the incredible number of anecdotes that exist on the subject of this whimsical character who dressed like a civil servant…

Baden Powell (1937-2000). Whenever Baden Powell de Aquino (his full name) spoke of his guitar teacher “Meira” [Jaime Florence], it was with love and deep respect. In a country which has never wanted for talented guitar-players, Baden Powell was still very young when he appeared as the man who would rejuvenate the instrument in using his thumb to give it a new impulse. A great creator, his most famous works (apart from the celebrated afro sambas) are Berimbau and Samba Triste, while his privileged lyricists were Vinicius de Moraes and Paulo César Pinheiro.

Carlos Lyra (born in 1936). A left-wing musician, he came from a musical family and worked closely with lyricist Ronaldo Boscoli before violently quarrelling with him when he felt his songs should have a more social and political dimension. He toured in the United States and Japan with Stan Getz, and also made a record with Paul Winter. Among other songs, Lyra is the author of Maria Ninguem (apparently a favourite of Jackie Kennedy), Se é tarde me perdoa and Lobo Bobo.

Roberto Menescal (born in 1937). A guitarist, producer (and amateur scuba fisherman), Menescal composed O Barquinho, which remains one of the great Bossa Nova hits. He was younger than Tom Jobim, so not from the same generation, and he was a close friend of the singer Nara Leão, the Bossa Nova’s muse.

Adapted by Martin Davies

from the french text of

Teca Calazans & Philippe Lesage

© 2015 Frémeaux & Associés

DISCOGRAPHIE CD1

1) CHEGA DE SAUDADE (Antonio Carlos Jobim / Vinicius de Moraes) DIZZY GILLESPIE : trompette, LEO WRIGHT : flute, alto sax, LALO SCHIFRIN : piano, CHRIS WHITE : bass, RUDY COLLINS : drums, ELEK BACSIK : guitare : PEPITO RIESTRA : percussions – Philips, PHS 600-048, 1962

2) DESAFINADO (Antonio Carlos Jobim / Newton Mendonça) STAN GETZ / CHARLIE BYRD STAN GETZ : tenor sax, CHARLIE BYRD, GENE BYRD : guitare, KETER BETTS : bass, BUDDY DEPPENSCHMIDT : drums, REICHENBACH : percussions – Verve, V6- 8432, 1962

3) STOMPY BOSSA NOVA (Coleman Hawkins) COLEMAN HAWKINS : tenor sax, BARRY GALBRAITH, HOWARD COLLINS : guitare, MAJOR HOLLEY : bass, EDDIE LOCKE, TOMMY FLANAGAN, WILLIE RODRIGUEZ : percussions - LP Impulse, A-28, 1962

4) BIM BOM (João Gilberto) STAN GETZ BIG BAND BOSSA NOVA –Arragend and Conducted by Gary Mcfarland – Verve, V6- 8494, 1962

5) DEVE SER AMOR (Baden Powell / Vinicius de Morais) HERBIE MANN : flute et alto flute, BADEN POWELL : guitare, GABRIEL : bass, JUQUINHA : drums – Atlantic LP AT, 5025, 1962

6) STAIRWAY TO THE STARS (Malneck / Parrish / Signorelli) LAURINDO ALMEIDA : guitare, BUD SHANK : alto sax, HARRY BABASIN : bass, ROY HARTE : drums – LP Brazilliance, WP 1412, 1962

7) INFLUÊNCIA DO JAZZ (Carlos Lyra) HERBIE MANN WITH SERGIO MENDES & BOSSA RIO Pedro Paulo : trompette, Paulo Moura : alto sax, Durval Ferreira : guitare, Sergio Mendes : piano, Otavio Bailly Junior : bass, Dom Um Romão : drums – Atlantic LP AT, 5025, 1962

8) CONSOLAÇÃO (Baden Powell) HERBIE MANN : fûte, BADEN POWELL : guitare, GABRIEL : bass, PAPÃO : drums – Atlantic LP AT, 5025, 1962

9) CORCOVADO (Antonio Carlos Jobim / Lees) JON HENDRICKS : vocal, GILDO MAHONES : piano, GEORGE TUCKER : bass, JIMMIE SMITH : drums, FRANK MESSINA : accordeon, BUDDY COLLETTE : flute, CONTE CANDOLI : trompette, MILT BERNARHT : trombone, RAY SHERMAN : orgue, Arrangements : JOHNNY MANDEL adaptés des arrangements pour cordes d’Antonio Carlos Jobim – Reprise Records, 1961

10) VOCÊ E EU (Carlos Lyra de Moraes / Hendriks) JON HENDRICKS : vocal, GILDO MAHONES : piano, GEORGE TUCKER : bass, JIMMIE SMITH : drums, FRANK MESSINA : accordeon, BUDDY COLLETTE : flute, CONTE CANDOLI : trompette, MILT BERNARHT : trombone, RAY SHERMAN : orgue, Arrangements : JOHNNY MANDEL adaptés des arrangements pour cordes d’Antonio Carlos Jobim – Reprise Records, 1961

11) SILVIA (Lalo Schifrin) LALO SCHIFRIN : piano, CHRIS WHITE : bass, RUDY COLLINS : drums, JIM HALL : guitare, CARMEN COSTA et JOSÉ PAULO : percussions – MGM E/SE 4110, 1962

12) ONE NOTE SAMBA (Antonio Carlos Jobim / Newton Mendonça) GEORGE SHEARING : woodwinds and brazilian rhythms. Arrangement : CLARE FISCHER – Capitol, ST 1873, 1962

13) MANHÃ DE CARNAVAL (Luiz Bonfá / Antonio Maria) GEORGE SHEARING : woodwinds and brazilian rhythm. Arrangement : CLARE FISCHER – Capitol, ST 1873, 1962

14) INQUIETAÇÃO (Laurindo Almeida) LAURINDO ALMEIDA : guitare, BUD SHANK : alto sax, HARRY BABASIN : bass, ROY HARTE : drums – LP Brazilliance, WP 1412, 1962

15) THE COLOR OF HER HAIR (Laurindo Almeida) BUD SHANK : alto flute, LAURINDO ALMEIDA : guitare, GARY PEACOCK : bass, CHUCK FLORES : drums. Arrangements : LAURINDO ALMEIDA – World Pacific Records, WP-1259, 1959

16) SE É TARDE ME PERDOA (Carlos Lyra / Ronaldo Boscoli) CAL TJADER : vibes, FREDDIE SCHREIBER : bass, JOHNNY RAE : drums, MILT HOLLAND : percussions, LAURINDO ALMEIDA : guitare, CLARE FISCHER : piano, PAUL HORN, DON SHELTON, BERNIE FLEISCHER, GENE CIPRIANO, JOHN LOWE : woodwinds – Verve, V-8470, 1962

17) VAI QUERER (HIANTO DE ALMEIDA / FERNANDO LOBO) CAL TJADER : vibes, FREDDIE SCHREIBER : bass, JOHNNY RAE : drums, MILT HOLLAND : percussions, LAURINDO ALMEIDA : guitare, CLARE FISCHER : piano, PAUL HORN, DON SHELTON, BERNIE FLEISCHER, GENE CIPRIANO, JOHN LOWE : woodwinds – Verve, V-8470, 1962

18) CHORA SUA TRISTEZA (NEVES / FIORINI) BOB BROOKMEYER : trombone, JIM HALL, JIMMY RANEY : guitare, GARY MCFARLAND : vibrafone, WILIE BOBO : latin drums, CARMEN COSTA : cabaça, JOSÉ PAULO : pandeiro – VM LP. 14019, VERVE, 1962

DISCOGRAPHIE CD 2

1) BOSSA NOVA USA (Dave Brubeck) DAVE BRUBECK QUARTET : PAUL DESMOND : alto sax, DAVE BRUBECK : piano, GENE WRIGHT : bass, JOE MORELLO : drums – Columbia, 4-42675, 1962

2) VENTO FRESCO (Dave Brubeck) DAVE BRUBECK QUARTET : PAUL DESMOND : alto sax, DAVE BRUBECK : piano, GENE WRIGHT : bass, JOE MORELLO : drum – Columbia, 4-42675, 1962

3) LAMENTO (Dave Brubeck) DAVE BRUBECK QUARTET : PAUL DESMOND : alto sax, DAVE BRUBECK : piano, GENE WRIGHT : bass, JOE MORELLO : drums – Columbia, 4-42675, 1962

4) SAMBA DE UMA NOTA SÓ (Antonio Carlos Jobim / Newton Mendonça) STAN GETZ BIG BAND BOSSA NOVA. Arranged and Conducted by Gary Mcfarland – Verve, V6- 8494, 1962

5) RECADO BOSSA NOVA 1 (Luis Antonio / Djalma Ferreira) ZOOTS SIMS : tenor sax, SPENCER SINATRA : flute, RON ALDRICH : clarinette, PHIL WOODS, GENE QUILL : clarinette, alto sax, JIM HALL, KENNY BURRELL : guitare, ART DAVIS : bass, SOL GUBIN : drums, TED SOMMER, WILLIE RODRIGUEZ : percussions – Colpix Records, SCP 435, 1962

6) RAPAZ DE BEM (Johnny Alf) LALO SCHIFRIN : piano, CHRIS WHITE : bass, RUDY COLLINS : drums, JIM HALL : guitare, CARMEN COSTA et JOSÉ PAULO : percussions – MGM E/SE 4110, 1962

7) ON NOTE SAMBA (Antonio Carlos Jobim / Newton Mendonça) HERBIE MANN : flute, ANTONIO CARLOS JOBIM : piano, vocal et arrangement, BADEN POWELL : guitare, string section – Atlantic / Fermata, LPAT, 5017, 1962

8) UM ABRAÇO NO BONFÁ (João Gilberto) COLEMAN HAWKINS : tenor sax, BARRY GALBRAITH, HOWARD COLLINS : guitare, MAJOR HOLLEY : bass, EDDIE LOCKE, TOMMY FLANAGAN, WILLIE RODRIGUEZ : percussions – LP Impulse, A- 28, 1962

9) YOU AND ME (Carlos Lyra / Vinicius de Moraes) LALO SCHIFRIN : piano, CHRIS WHITE : bass, RUDY COLLINS : drums, JIM HALL : guitare, CARMEN COSTA et JOSÉ PAULO : percussions – MGM E/SE 4110, 1962

10) O PATO (Jayme Silva, Neuza Teixeira) COLEMAN HAWKINS : tenor sax, BARRY GALBRAITH, HOWARD COLLINS : guitare, MAJOR HOLLEY : bass, EDDIE LOCKE, TOMMY FLANAGAN, WILLIE RODRIGUEZ : percussions – LP Impulse, A- 28, 1962

11) DESAFINADO (Antonio Carlos Jobim / Newton Mendonça) DIZZY GILLESPIE : trompette, LEO WRIGHT : flute, alto sax, LALO SCHIFRIN : piano, CHRIS WHITE : bass, RUDY COLLINS : drums, JOSÉ PAULO, CARMEN COSTA : percussions – Philips, PHS 600-048, 1962

12) CIUME (Carlos Lyra) ZOOTS SIMS : tenor sax, SPENCER SINATRA : flute, RON ALDRICH : clarinette, PHIL WOODS, GENE QUILL : clarinette, alto sax, JIM HALL, KENNY BURRELL : guitare, ART DAVIS : bass, SOL GUBIN : drums, TED SOMMER, WILLIE RODRIGUEZ : percussions – Colpix Records, SCP 435, 1962

13) AMOR EM PAZ (Antonio Carlos Jobim / Vinicius de Moraes) HERBIE MANN : flute, ANTONIO CARLOS JOBIM : piano, vocal et arrangement, BADEN POWELL : guitare, string section – Atlantic / Fermata, LPAT 5017, 1962

14) SPEAK LOW (Nash / Weill) LAURINDO ALMEIDA : guitare, BUD SHANK : alto sax, HARRY BABASIN : bass, ROY HARTE : drums – LP Brazilliance, WP 1412, 1962

15) LONELY (Laurindo Almeida / Bud Shank) BUD SHANK : alto flute, LAURINDO ALMEIDA : guitare, GARY PEACOCK : bass, CHUCK FLORES : drums. Arrangements : LAURINDO ALMEIDA – World Pacific Records, WP-1259, 1959

16) VELHOS TEMPOS (Luis Bonfa) CHARLIE ROUSE : tenor sax, KENNY BURRELL, CHAUNCEY WESTBROOK : guitare, LAWRENCE GALES : bass, WILLIE BOBO : drums, POTATO VALDES : conga, GARVIN MASSEAU : chekere – Blue Note, 4119, 1960

17) LALO’S BOSSA NOVA (Lalo Schifrin) LALO SCHIFRIN : piano, CHRIS WHITE : bass, RUDY COLLINS : drums, JIM HALL : guitare, CARMEN COSTA et JOSÉ PAULO : percussions – MGM E/SE 4110, 1962

18) CHEGA DE SAUDADE / NO MORE BLUES (Antonio Carlos Jobim / Vinicius de Moraes, Hendricks et Cavanaugh) JON HENDRICKS : vocal, GILDO MAHONES : piano, GEORGE TUCKER : bass, JIMMIE SMITH : drums, FRANK MESSINA : accordeon, BUDDY COLLETTE : flute, CONTE CANDOLI : trompette, MILT BERNARHT : trombone, RAY SHERMAN : orgue. Arrangements : JOHNNY MANDEL adaptés des arrangements pour cordes d’Antonio Carlos Jobim – Reprise Records, 1961

DISCOGRAPIE CD 3

1) CANTANDO A ORQUESTRA (Claros Lyra) ZOOTS SIMS : tenor sax, SPENCER SINATRA : flute, RON ALDRICH : clarinette, PHIL WOODS, GENE QUILL : clarinette, alto sax, JIM HALL, KENNY BURRELL : guitare, ART DAVIS : bass, SOL GUBIN : drums, TED SOMMER, WILLIE RODRIGUEZ : percussions – Colpix Records, SCP 435, 1962

2) CORAÇÃO SENSIVEL (Teo Macero) DAVE BRUBECK QUARTET : PAUL DESMOND : alto sax, DAVE BRUBECK : piano, GENE WRIGHT : bass, JOE MORELLO : drums – Columbia, 4-42675, 1962

3) IRMÃO AMIGO (Dave Brubeck) DAVE BRUBECK QUARTET : PAUL DESMOND : alto sax, DAVE BRUBECK : piano, GENE WRIGHT : bass, JOE MORELLO : drums – Columbia, 4-42675, 1962

4) É LUXO SÓ (Ary Barroso / Luis Peixoto) STAN GETZ / CHARLIE BYRD, STAN GETZ : tenor sax, CHARLIE BYRD, GENE BYRD : guitare, KETER BETTS : bass, BUDDY DEPPENSCHMIDT : drums, REICHENBACH : percussions – Verve, V6- 8432, 1962

5) SAMBA TRISTE (Baden Powell / Billy Blanco) STAN GETZ / CHARLIE BYRD : STAN GETZ : tenor sax, CHARLIE BYRD, GENE BYRD : guitare, KETER BETTS : bass, BUDDY DEPPENSCHMIDT : drums, REICHENBACH : percussions – Verve, V6- 8432, 1962

6) OUTRA VEZ / ONCE AGAIN (Antonio Carlos Jobim / Hendriks) JON HENDRICKS : vocal, GILDO MAHONES : piano, GEORGE TUCKER : bass, JIMMIE SMITH : drums, FRANK MESSINA : accordeon, BUDDY COLLETTE : flute, CONTE CANDOLI : trompette, MILT BERNARHT : trombone, RAY SHERMAN : orgue. Arrangements : JOHNNY MANDEL adaptés des arrangements pour cordes d’Antonio Carlos Jobim – Reprise Records, 1961

7) DESAFINADO (Antonio Carlos Jobim / Newton Mendonça) COLEMAN HAWKINS : tenor sax, BARRY GALBRAITH, HOWARD COLLINS : guitare, MAJOR HOLLEY : bass, EDDIE LOCKE, TOMMY FLANAGAN, WILLIE RODRIGUEZ : percussions – LP Impulse, A- 28, 1962

8) INSENSATEZ (Antonio Carlos Jobim) LALO SCHIFRIN : piano, CHRIS WHITE : bass, RUDY COLLINS : drums, JIM HALL : guitare, CARMEN COSTA et JOSÉ PAULO : percussions – MGM E/SE 4110, 1962

9) ELIZETE (Clare Fischer) CAL TJADER : vibes, FREDDIE SCHREIBER : bass, JOHNNY RAE : drums, MILT HOLLAND : percussions, LAURINDO ALMEIDA : guitare, CLARE FISCHER : piano, PAUL HORN, DON SHELTON, BERNIE FLEISCHER, GENE CIPRIANO, JOHN LOWE : woodwinds – Verve, V-8470, 1962

10) I REMEMBER YOU (Mercer / Schertzinger) COLEMAN HAWKINS : tenor sax, BARRY GALBRAITH, HOWARD COLLINS : guitare, MAJOR HOLLEY : bass, EDDIE LOCKE, TOMMY FLANAGAN, WILLIE RODRIGUEZ : percussions – LP Impulse, A- 28, 1962

11) O AMOR EM PAZ / LOVE AND PEACE (Antonio Carlos Jobim / De Moraes / Hendricks) JON HENDRICKS : vocal, GILDO MAHONES : piano, GEORGE TUCKER : bass, JIMMIE SMITH : drums, FRANK MESSINA : accordeon, BUDDY COLLETTE : flute, CONTE CANDOLI : trompette, MILT BERNARHT : trombone, RAY SHERMAN : orgue. Arrangements : JOHNNY MANDEL adaptés des arrangements pour cordes d’Antonio Carlos Jobim – Reprise Records, 1961

12) ON NOTE SAMBA (Antonio Carlos Jobim / Newton Mendonça) COLEMAN HAWKINS : tenor sax, BARRY GALBRAITH, HOWARD COLLINS : guitare, MAJOR HOLLEY : bass, EDDIE LOCKE, TOMMY FLANAGAN, WILLIE RODRIGUEZ : percussions – LP Impulse, A- 28, 1962

13) MEDITAÇÃO (Antonio Carlos Jobim / Newton Mendonça) CAL TJADER : vibes, FREDDIE SCHREIBER : bass, JOHNNY RAE : drums, MILT HOLLAND : percussions, LAURINDO ALMEIDA : guitare, CLARE FISCHER : piano, PAUL HORN, DON SHELTON, BERNIE FLEISCHER, GENE CIPRIANO, JOHN LOWE : woodwinds – Verve, V-8470, 1962

14) NÃO DIGA NADA (Carlito / Noacy Marcenes) CAL TJADER : vibes, FREDDIE SCHREIBER : bass, JOHNNY RAE : drums, MILT HOLLAND : percussions, LAURINDO ALMEIDA : guitare, CLARE FISCHER : piano, PAUL HORN, DON SHELTON, BERNIE FLEISCHER, GENE CPRIANO, JOHN LOWE : woodwinds – Verve, V-8470, 1962

15) SAMBA DE ORFEU (Luis Bonfá) CHARLIE ROUSE : tenor sax, KENNY BURRELL, CHAUNCEY WESTBROOK : guitare, LAWRENCE GALES : bass, WILLIE BOBO : drums, POTATO VALDES : conga, GARVIN MASSEAU : chekere – Blue Note, 4119, 1960

16) A FELICIDADE (Antonio Carlos Jobim / Vinicius de Moraes) BOB BROOKMEYER : piano, JIM HALL, JIMMY RANEY : guitare, GARY MCFARLAND : vibrafone, WIILIE BOBO : latin drums, CARMEN COSTA : cabaça, JOSÉ PAULO : pandeiro – Verve, VM LP. 14019, 1962

17) COISA MAIS LINDA / THES MOST BEAUTIFUL THING (Carlos Lyra / Vinicius de Moraes / Hendricks) JON HENDRICKS : vocal, GILDO MAHONES : piano, GEORGE TUCKER : bass, JIMMIE SMITH : drums, FRANK MESSINA : accordeon, BUDDY COLLETTE : flute, CONTE CANDOLI : trompette, MILT BERNARHT : trombone, RAY SHERMAN : orgue. Arrangements : JOHNNY MANDEL adaptés des arrangements pour cordes d’Antonio Carlos Jobim – Reprise Records, 1961

18) MARIA NINGUÉM (Carlos Lyra) ZOOTS SIMS : tenor sax, SPENCER SINATRA : flute, RON ALDRICH : clarinette, PHIL WOODS, GENE QUILL : clarinette, alto sax, JIM HALL, KENNY BURRELL : guitare, ART DAVIS : bass, SOL GUBIN : drums, TED SOMMER, WILLIE RODRIGUEZ : percussions – Colpix Records, SCP 435, 1962

Les deux premiers albums de João Gilberto qui signent la naissance de la Bossa Nova à Rio de Janeiro en 1958 (fausse indolence, simplification du rythme du samba, accords alterés, autre manière de placer la voix et de décaler le rythme à la guitare) firent découvrir aux jazzmen, producteurs de disques et de radio américains un nouveau langage musical. Au prisme de leur propre code de lecture, ils s’émancipèrent des règles pour offrir une autre vitalité savoureuse. Vite, la prophylaxie de la Bossa Nova s’est répandue dans le monde entier pour ne plus s’éteindre.

Philippe Lesage

João Gilberto’s first two albums made in Rio de Janeiro in 1958 gave Bossa Nova its birth certificate: misleading indolence, simplified samba rhythms, altereted chords, and a new way of placing the voice while shifting the rhythm on guitar. He gave jazzmen, record-producers and American radio a new musical language. Through the prism of their own codes, his contributions freed themselves from traditional rules to provide savoury new vitality to popular music, and the Bossa Nova spread throughout the world like a universal remedy.

Teca Calazans

CD 1

1. Chega De Saudade (Dizzy Gillespie) 10’08

2. Desafinado (Stan Getz) 5’50

3. Stompy Bossa Nova (Coleman Hawkins) 2’31

4. Bim Bom (Stan Getz) 4’31

5. Deve Ser Amor (Herbie Mann) 4’12

6. Starway To The Stars (Laurindo Almeida) 3’00

7. InfluÊncia Do Jazz (Herbie Mann) 5’42

8. Consolação (Herbie Mann) 4’22

9. Corcovado (Jon Hendricks) 2’06

10. Você E Eu (Jon Hendricks) 3’06

11. Silvia (Lalo Schifrin) 3’11

12. On Note Samba (George Shearing) 2’46

13. Manhã De Carnaval (Geoge Shearing) 2’18

14. Inquietação (Laurindo Almeida) 3’04

15. The Color Of Her Hair (Bud Shank) 1’58

16. Se É Tarde Me Perdoa (Cal Tjader) 2’49

17. Vai Querer (Cal Tjader) 2’29

18. Chora Sua Tristeza (Bob Brookmeyer) 4’13

CD 2

1. Bossa Nova Usa (Dave Brubeck) 2’26

2. Vento Fresco (Dave Brubeck) 3’32

3. Lamento (Dave Brubeck) 4’45

4. Samba De Uma Nota Só (Stan Getz) 6’10

5. Recado Bossa Nova 1 (Zoot Sims) 2’35

6. Rapaz De Bem (Lalo Schifrin) 2’33

7. One Note Samba (Herbie Mann) 3’24

8. Um Abraço No Bonfá (Coleman Hawkins) 4’51

9. You And Me (Lalo Schifrin) 1’46

10. O Pato (Coleman Hawkins) 4’08

11. Desafinado (Dizzy Gillespie) 3’19

12. Ciume (Zoot Sims) 4’12

13. Amor Em Paz (Herbie Mann) 2’38

14. Speak Low (Laurindo Almeida) 2’21

15. Lonely (Bud Shank) – 3’54

16. Velhos Tempos (Charlie Rouse) 4’46

17. Lalo’s Bossa Nova (Lalo Schifrin) 2’15

18. Chega De Saudade

(Jon Hendricks) 2’05

CD 3

1. Cantando A Orquestra (Zoot Sims) 4’09

2. Coração Sensivel (Dave Brubeck) 4’13

3. Irmão Amigo (Dave Brubeck) 3’22

4. É Luxo Só (Stan Getz) 3’42

5. Samba Triste (Stan Getz) 4’45

6. Outra Vez (Jon Hendricks) 1’56

7. Desafinado (Coleman Hawkins) 5’46

8. Insensatez (Lalo Schifrin) 2’21

9. Elizete (Cal Tjader) 3’02

10. I Remember You (Coleman Hawkins) 3’58

11. Amor Em Paz (Jon Hendricks) 2’33

12. One Note Samba (Coleman Hawkins) 5’58

13. Meditação (Cal Tjader) 3’32

14. Não Diga Nada (Cal Tjader) 2’44

15. Samba De Orfeu (Charlie Rouse) 6’11

16. A Felicidade (Bob Brookmeyer) 3’16

17. Coisa Mais Linda (Jon Hendricks) 3’05

18. Maria Ninguém (Zoot Sims) 2’38