- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

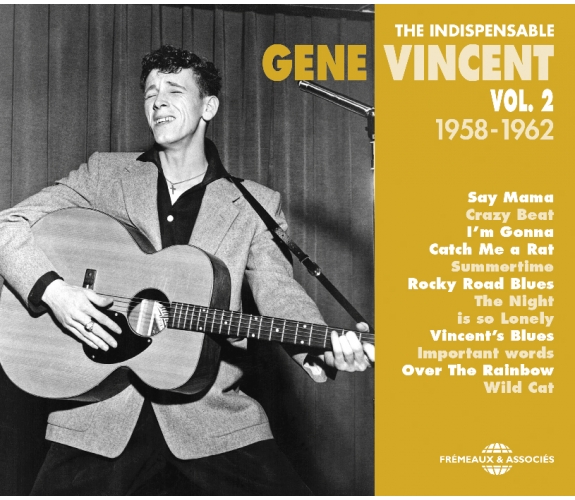

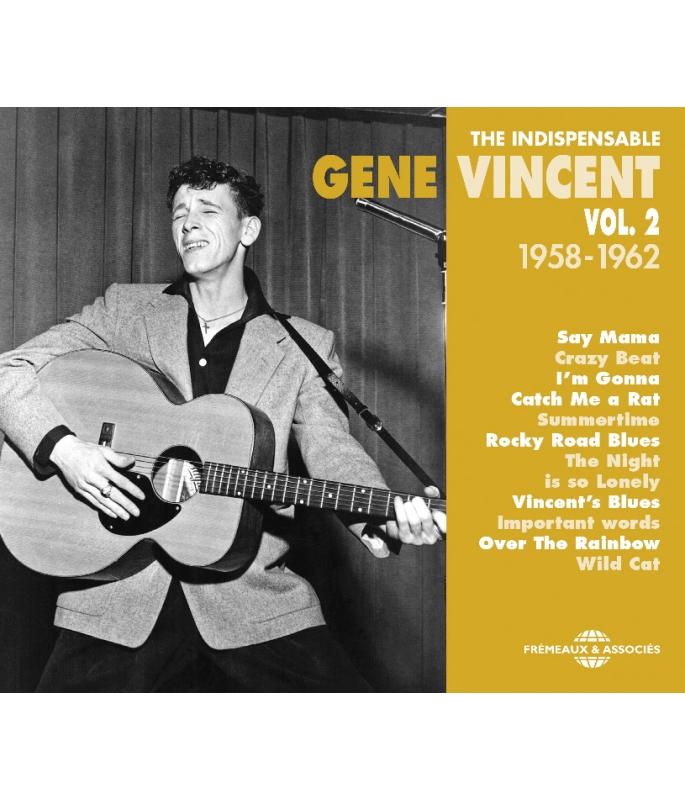

GENE VINCENT

Ref.: FA5422

Artistic Direction : BRUNO BLUM

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Total duration of the pack : 2 hours 49 minutes

Nbre. CD : 3

After Be-Bop-a-Lula, in which Gene Vincent and the Blue Caps sent tremors through the world of rock’n’roll, the years 1958-1962 saw Gene varying his style with several remarkable albums of great influence. They were only really successful in England, where the public adopted Gene as Eddie Cochran’s equal (he recorded and toured with him). With a bonus of six titles taken from broadcasts by the BBC, this second volume completes the studio recordings made by Gene Vincent in the first part of his career. Patrick FRÉMEAUX

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Five Feet Of Lovin'Gene VincentPeddy Buck00:02:141958

-

2Somebody Help MeGene VincentKelly Bob00:02:121958

-

3Look What You Gone And Done To MeGene VincentRobert Lee Jones00:02:061958

-

4Hey Good Lookin'Gene VincentWilliams Hiram King00:02:331958

-

5I Can't Help It (If I'M Still In Love With You)Gene VincentWilliams Hiram King00:02:521958

-

6SummertimeGene VincentGeorge Gershwin00:02:571958

-

7Now Is The HourGene VincentMaewa Kalhan00:03:001958

-

8The Wayward WindGene VincentStanley Richard Lebowsky00:02:461958

-

9Lonesome BoyGene VincentTommy Baldwell00:02:101958

-

10You Are The One For MeGene VincentCfifton Simmons00:02:221958

-

11MaybeGene VincentJohnny Caroll00:02:231958

-

12My HeartGene VincentJohnny Burnette00:02:291958

-

13I Got To Get You YetGene VincentJohnny Burnette00:02:121958

-

14The Night Is So LonelyGene VincentGene Vincent00:02:331958

-

15Beautiful Brown EyesGene VincentArthur Smith00:03:091958

-

16Rip It UpGene VincentRobert Blackwell00:02:031958

-

17MaybelleneGene VincentAlan Freed00:02:301958

-

18High Blood PressureGene VincentHuey Smith00:02:501958

-

19Be Bop Boogie BoyGene VincentGene Vincent00:01:511958

-

20In Love AgainGene VincentGene Vincent00:02:331958

-

21I Can't Believe You Wanna LeaveGene VincentLloyd Price00:02:481958

-

22Who's Pushing Your SwingGene VincentGlenn Artie00:02:051958

-

23Gone Gone GoneGene VincentJoe South00:02:111958

-

24Anna AnnabelleGene VincentClifton Simmons00:01:391958

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Say MamaGene VincentJohnny Earl00:02:151958

-

2My Baby Don't LowGene VincentGene Vincent00:02:351958

-

3Important WordsGene VincentGene Vincent00:02:431958

-

4I Might Have KnownGene VincentJoe South00:02:111958

-

5Over The RainbowGene VincentHarburg Edgar Yipsel00:02:571958

-

6Vincent's BluesGene VincentGene Vincent00:02:221958

-

7Ready TeddyGene VincentRobert Blackwell00:01:591958

-

8She She Little SheilaGene VincentWhitey Pullen00:02:301958

-

9Ac-Centu-Ate The PositiveGene VincentJohnny Mercer00:02:041958

-

10Pretty PearlyGene VincentDiane Johnson00:02:261958

-

11DarleneGene VincentGene Vincent00:02:471959

-

12Why Don't You People Learn To DriveGene VincentJames Noble00:02:011959

-

13Greenback Dollar Watch And ChainGene VincentRay Harris00:02:221959

-

14Crazy TimesGene VincentBurt Bacharach00:02:151959

-

15Wild CatGene VincentWalter Gold00:02:261959

-

16Ridht Here On EarthGene VincentCharles Singleton00:02:321959

-

17Hot DollarGene VincentOllie Jones00:02:261959

-

18Big Fat Saturday NightGene VincentLuther Diwon00:02:031959

-

19Mitchiko From TokyoGene VincentHansard00:02:161959

-

20Blue Eyes Crying In The RainGene VincentFred Rose00:02:171959

-

21Everybody's Got A Date But MeGene VincentAaron Harold Schroeder00:02:091959

-

22Wild CatGene VincentWalter Gold00:02:101959

-

23My HeartGene VincentJohn Joseph Burnette00:01:451960

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1SummertimeGene VincentHeyward Dubose00:02:571960

-

2Say MamaGene VincentJohnny Earl00:02:021960

-

3Rocky Road BluesGene VincentWilliam Smith Monroe00:02:281960

-

4Be Bop A LulaGene VincentGene Vincent00:03:551960

-

5Pistol Packi' MamaGene Vincent00:02:111960

-

6Weeping WillowGene VincentDebra Lynn00:02:411960

-

7Crazy BeatGene VincentJohnny Fallin00:02:061960

-

8I'm Gonna Catch Me A RatGene VincentJessie Mae Robinson00:02:061960

-

9It's Been NiceGene VincentMort Shuman00:01:591960

-

10That's The Trouble With LoveGene VincentRobert Chilton00:02:121961

-

11Good Lovin'Gene VincentRorie00:02:041961

-

12Mister LonelinessGene VincentNeil Nephew00:01:571961

-

13TeaedropsGene VincentRichard Eugene Glasser00:02:311961

-

14If You Want My LovinGene VincentGraham Morrison Turnbull00:01:591961

-

15I'm Goin' Home (To See My Baby)Gene VincentBob Bain00:02:411961

-

16Love Of A ManGene VincentEd Newman00:02:301961

-

17Spaceship To MarsGene VincentMilton Subotsky00:02:031961

-

18There I Go AgainGene VincentJohn Gillard00:02:381961

-

19Baby Don't Believe HimGene VincentClyde Pitts00:02:181961

-

20Lucky StarGene VincentDave Burgess00:02:161961

-

21The King Of FoolsGene VincentBob Barratt00:02:331961

-

22You're Still In My HeartGene VincentBob Barratt00:02:401961

-

23Held For QuestioningGene VincentCharles Blackwell00:02:161961

-

24Be-Bop-A-LulaGene VincentGene Vincent00:02:111962

Gene Vincent vol. 2 FA5422

THE INDISPENSABLE

GENE VINCENT

VOL. 2

1958-1962

The Indispensable Gene Vincent VOLUME 2 1958-1962

Par Bruno Blum

Dans notre premier volume Gene Vincent et ses Blue Caps déploient une magie telle que rétrospectivement, leur réputation de rois du rockabilly reste quasiment indiscutable. Avec l’extraordinaire guitariste Cliff Gallup répondant aux charmes vocaux de Gene Vincent, de «?Be-Bop-a-Lula??» à «??Cruisin’?» leur millésime 1956 a marqué à tout jamais l’histoire de la musique populaire américaine. Rebelles, brillants, marginaux, fulgurants, Gene Vincent and his Blue Caps ont fait triompher l’esprit du rock avec authenticité et talent. Comme le montre notre anthologie Rockabilly 1951-1960 dans cette collection, il existe une pléthore d’autres splendides enregistrements dans le style rockabilly, ce qui rend la suprématie des Blue Caps d’autant plus valorisante qu’ils rivalisaient avec des monstres sacrés comme Johnny Cash, Johnny Burnette, Carl Perkins, Lew Williams, Jerry Lee Lewis, Buddy Holly ou Elvis Presley — mais objectivement aucun d’entre eux, même Elvis, n’a su graver autant de chefs-d’œuvre dans l’esthétique du pur rockabilly1.

Perdant Magnifique

En 1956, après quelques premiers mois de succès le départ de l’époustouflant guitariste Cliff Gallup a porté un coup terrible au chanteur. L’abandon de Sheriff Tex, le disc jockey manager qui avait décroché le contrat avec les disques Capitol et orchestré le succès immense de Be-Bop-a-Lula (dont il s’est attribué au passage une partie des droits d’auteur) a rendu la situation de Gene Vincent critique. Devant supporter le mode de vie très dur des tournées incessantes en dépit de son grave handicap à la jambe gauche, subissant des échecs conjugaux en raison de son absence du foyer pour raisons professionnelles et sans succès discographique vraiment consistant depuis «?Be-Bop-a-Lula?» à l’été 1956, Gene Vincent souffrait en outre d’une forte tendance à l’alcoolisme, ce qui compliquait signi-fi-cativement ses relations professionnelles et affectives.

«?Boiteux à la suite d’un accident de moto qui le pousse à consommer alcool et morphine, sa vie pleine de tensions et de problèmes de santé est marquée par une malchance acharnée, mais sa grande sensibilité lui permet malgré tout d’atteindre des sommets dans son art. Personnage attachant rappelant James Dean mais paranoïaque, instable, il est son propre pire ennemi, usant amours, amitiés et bonnes volontés avec une constance suicidaire.?»

— Jean-William Thoury, Le Dictionnaire du rock (Robert Laffont, 2001)

Livré à lui-même, sa carrière a vite pâti d’un net manque de soutien, de direction et a subi diverses errances dès 1956. Elles mèneront en fin de compte à sa fin tragique à l’âge de trente-six ans, ce qui a participé à son mythe de «?perdant magnifique?» du rock, mort jeune, brisé par une cruelle et ingrate indifférence. Un grave accident de voiture, où son ami et collaborateur Eddie Cochran perdit la vie en 1960 et où sa jambe fut à nouveau brisée en morceaux n’a rien arrangé. Pas plus qu’un deuxième divorce dévastateur qui le priva de ses deux enfants en 1961. Pourtant le poids de la légende fait parfois oublier que dans l’ombre de «?Be-Bop-a-Lula?» Gene Vincent (11 février 1935-12 octobre 1971) a laissé à la postérité nombre d’autres morceaux aussi splendides que méconnus, dont une seconde partie est incluse dans ce volume deux de sa période Capitol de 1958 à 1962. Si l’excellence des Blue Caps originels est restée insurpassable, la suite de son œuvre reste d’une très bonne tenue, comme en témoignent ici des classiques comme Say Mama, Crazy Beat, I’m Gonna Catch Me a Rat ou encore la version inspirée de Summertime enregistrée à Londres par la radio BBC. Certes ses différents accompagnateurs et producteurs restent critiquables en quelques occasions. Mais les interprétations remarquables du jeune Gene ont toujours compté parmi celles des plus grands.

A Gene Vincent Record Date

Les dernières séances d’enregistrement de la formation originelle de Gene Vincent and his Blue Caps avec Cliff Gallup à la guitare ont eu lieu en octobre 1956. L’intégrale de leurs trente-cinq titres en studio (plus deux en public), qui restent le nec le plus ultra du rockabilly, figurent dans notre volume 1. Elle y est complétée par trente et un morceaux de la deuxième configuration des Blue Caps, où Johnny Meeks tenait la guitare. Basse électrique, nouveau guitariste soliste, chœurs, style plus diversifié, en évolution, cette deuxième phase montre un changement de son très net dès la fin 1956, avec un éloignement des canons du rockabilly originel comme on le retrouve également chez tous leurs contemporains (Buddy Holly, Eddie Cochran, Elvis Presley, etc.). Les premières séances d’enregistrement avec Johnny Meeks à la guitare ont eu lieu en juin 1957. La chasse aux sorcières qui frappait les artistes de rock pendant cette période les incitait à adoucir et élargir quelque peu leur répertoire et, sans doute poussé par les disques Capitol, Gene Vincent n’y a pas échappé. La forte présence d’un groupe vocal, influence directe des Jordanaires — un groupe de gospel blanc présent sur tant d’enregistrements d’Elvis Presley — est un aspect marquant de cette évolution. Néanmoins si Gene Vincent a toujours été un chanteur de ballades émouvant, il tiendra résolument un cap rock.

Appelé à l’armée, Elvis Presley est parti faire son service militaire le 24 mars 1958. Dès lors, ses disques seront orientés vers une diversité de styles, délaissant partiellement le rock. Si le phénomène Presley a largement perduré pendant ses deux années de quasi absence, le rock avait très mauvaise réputation en 1958 et tous les artistes du genre en ont pâti. Les musiciens aussi2. Ce volume deux de l’œuvre de Gene Vincent commence précisément en mars 1958, au moment ou Presley partait à l’armée en pleine gloire, sous les feux des médias du monde. Une nouvelle phase a commencé pour l’histoire du rock, et ce volume deux de l’œuvre de Gene Vincent va plus loin encore dans cette tendance à la diversification, caractéristique du rock de l’époque.

L’agent de concerts McLemore de Dallas au Texas infligeait aux Blue Caps un calendrier épuisant. Après trois mois de tournées sur la côte ouest, le troisième album Gene Vincent Rocks and the Blue Caps Roll est sorti le 18 mars 1958. Le batteur Dickie Harrell a été le dernier membre des Blue Caps originels à jeter l’éponge. Harrell est parti s’installer avec la sœur du choriste Tommy Facenda : une nouvelle déception pour Gene Vincent (qui le remplaça par Judey Gomez et plus tard Clyde Pennington). Étant donné le dilettantisme de Johnny Meeks (proche de Gene, le guitariste partait peu volontiers en tournée), le pianiste Clifton Simmons était devenu le leader du groupe, qui a enregistré de nouveaux titres à la fin du mois de mars, dont une nouvelle et élégante version de Five Feet of Lovin’ qui ouvrirait l’album Record Date. Ces changements de musiciens de plus en plus récurrents ont contribué à ce que le chanteur se rapproche de son ami Eddie Cochran, un autre auteur compositeur interprète majeur du rock, dont la carrière ne cessait de marquer des points en 1958. Gene et Eddie s’étaient rencontrés lors du tournage de «?La Blonde et moi?» (The Girl Can’t Help It, Frank Tashlin, 1956) et étaient devenus amis lors d’une mémorable tournée australienne en octobre 1957. La tête d’affiche Little Richard avait quitté la tournée prématurément, laissant Gene et Eddie assurer le rôle de vedettes.

En effet le 11 octobre 1957, Little Richard chantait à Sydney dans une arène en plein air devant quarante mille personnes. Il aperçut en plein concert un objet volant non identifié, une boule de feu dans le ciel, (il supposera plus tard qu’il s’agissait du Sputnik I russe, premier satellite artificiel de l’histoire, mais il avait été mis en orbite le 4). Croyant à un signe céleste, il abandonna le piano en plein morceau et quitta la scène sans crier gare. Sa décision était prise : il laissait tout tomber et rentrait chez lui. Il se consacrerait à Dieu. Little Richard annonça la nouvelle aux musiciens le lendemain et la troupe interloquée s’envola pour Los Angeles sur le champ, perdant un demi-million de dollars de 1957 en cachets australiens. Quelques jours plus tard, selon Richard l’avion qu’il aurait dû prendre pour rentrer d’Australie s’écrasa dans la mer, ce qu’il vit comme un signe divin supplémentaire. Gene Vincent et Eddie Cochran assurèrent le reste de la tournée sans la superstar. À dix-neuf ans en mars 1958, le Californien Eddie Cochran était déjà un remarquable musicien de studio, capable de composer et chanter de façon très personnelle. Il était aussi coutumier des séances d’enregistrement en tant que guitariste d’accompagnement, et soliste de rock comme de country. Eddie avait enregistré le 12 janvier sa chanson «?Jeannie Jeannie Jeannie?» et un mois plus tard en mai 1958 il gravera l’un de ses plus gros succès, l’excellent «?Summertime Blues?». Cochran a participé aux chœurs des huit premiers titres figurant sur le disque 1 de ce volume (on peut aussi l’entendre sur notre volume 1). On entend bien sa voix grave sur l’album A Gene Vincent Record Date, notamment sur la ballade Wayward Wind, reprise d’un succès country de Tex Ritter datant de 1956. La présence d’Eddie Cochran eut aussi une influence importante sur le son de Gene pendant cette période. Les deux amis (Gene n’avait que trois ans de plus que lui) ont échangé des idées d’arrangements. Dans la période qui va suivre, les enregistrements de Cochran seront marqués par une sophistication analogue, notamment des chœurs3. On entend aussi Eddie sur Now Is the Hour et d’autres titres (voir discographie). Ces séances ont produit leur lot de futurs classiques : Rocky Road Blues, «?Git It?»... Peek et Facenda ont été tentés par une carrière solo mais sont revenus le temps que soit tourné Hot Rod Gang (Lew Landers, 1958) avec John Ashley et Jody Fair. Ce film long métrage montre Gene Vincent dans un petit rôle et chantant «?Dance In The Street?», «?Baby Blue?» et «?Dance To The Bop?» (inclus dans notre volume 1).

En mai 1958, Gene s’est marié avec Darlene Hicks, 19 ans, déjà mère de Debbie, deux ans. Darlene se déplaçait souvent avec lui en tournée. Elle n’appréciait pas son absence et devait composer entre sa petite fille et son mari. C’était le deuxième mariage du chanteur, qui avait épousé Ruth Ann Hand (15 ans) en 1955. Leur union avait été de courte durée. De mars à octobre 1958 le groupe est reparti tourner aux quatre coins des États-Unis. Johnny Meeks a préféré rentrer chez lui à Greenville et a été remplacé par Howard Reed. Il ne reviendra qu’en octobre pour enregistrer à nouveau. Dirigés par le pianiste Clifton Simmons, les nouveaux Blue Caps ont subi des changements incessants. Les tensions étaient palpables, mais le quatrième album A Gene Vincent Record Date (sorti en novembre 1958) reste l’une des meilleurs productions de la fin des années cinquante. Pour certains d’admirateurs de Gene Vincent, c’est son album le plus abouti et le plus réussi — le plus mûr. C’est en tous cas ce qu’il a gravé de mieux dans les studios de la Tour Capitol à Hollywood. Plus cool que le volcan des débuts, le trente centimètres en vinyle est soigné et raffiné. Parfaitement dans son époque, il a un son vraiment caractéristique de la période, riche, enjoué, plein de réverb et de choristes. Il sera influent, et pas seulement sur Eddie Cochran. On retrouvera notamment ce type de chœurs dans les enregistrements de Vince Taylor («?I’ll Be Your Hero?» ou «?Wat’cha Gonna Do?», 1960) qui sera très marqué par Gene Vincent, ou encore des Chaussettes Noires d’Eddy Mitchell («?Dactylo Rock?», 1961), qui enregistreront aussi une adaptation française de Be-Bop-a-Lula en 1960. Le single Say Mama/Be Bop Boogie Boy a été publié en même temps que l’album. Deux disques excellents, mais qui n’ont eu aucun impact à leur sortie.

Sounds Like Gene Vincent

En 1958, le rock avait mauvaise réputation. Avec Elvis au service militaire depuis mars (ses disques continuaient à sortir et à vendre énormément mais étaient de plus en plus éloignés du rock), sans oublier le décès à 22 ans de Buddy Holly le 3 février 1959, Eddie Cochran et Gene Vincent devenaient peu à peu les deux principaux chanteurs blancs à réellement représenter l’étendard du rock. Les Everly Brothers et Ricky Nelson avaient du succès ; mais leur musique, bien plus douce, correspondait aux attentes de radios qui n’avaient que faire de titres trop rapides, trop excitants — trop rock. Même le roi Chuck Berry devait ralentir le tempo4. Si Bo Diddley avait de plus en plus de succès, son style très à part le marginalisait5. Quant à Little Richard, il était entré en religion en octobre 576. En outre, en 1958 une guerre commerciale entre radios et distributeurs de juke-boxes a eu pour conséquence un scandale de pots-de-vin qui décima les disc jockeys rock, les programmes de radio et avec eux, les chanteurs de rock. Deux singles forts de Gene Vincent, Rocky Road Blues/«?Yes I Love You Baby?» en juillet et «?Git It?»/«?Little Lover?» en septembre n’ont pas obtenu grand succès. Le «?Summertime Blues?» d’Eddie Cochran a été l’un des rares véritables rocks à pénétrer les sommets des ventes cet été-là.

Dans ce contexte difficile, malgré la qualité de son travail en studio Gene Vincent était contraint de continuer à tourner comme un forcené de la Californie au Canada, remplissant des salles en s’entourant de musiciens professionnels compétents mais avant tout attirés par les cachets. Brusqués par les comportements de Gene et les conditions de voyage, peu sont restés bien longtemps. Peek, Facenda et le pivot du groupe, le guitariste Johnny Meeks (remplacé en concert par Howard Reed) refusaient le plus souvent de partir à l’aventure sur la route. Ils sont tout de même revenus pour enregistrer à l’automne. Mais d’autres ne pouvaient se libérer. Les départs et retours successifs de Mac Lipscomb, Facenda, Grady Owen, Paul Peek, Johnny Meeks et d’autres ont été une plaie pour Gene Vincent.

D’un autre point de vue, de nouvelles collaborations forcées ont enrichi les enregistrements de la rentrée. La participation de musiciens provisoires provoqua quelques expériences et idées nouvelles. En octobre 58, une nouvelle semaine en studio a précédé la sortie de l’album Record Date, qui dévoilait des morceaux enregistrés en mars. Gene avait engagé le saxophoniste Jackie Kelso, un accompagnateur de Johnny Otis qui travailla avec Duke Ellington, Barney Bigard, Lucky Thompson et nombre d’autres artistes très divers. Le sax de Kelso modifia sensiblement le son du groupe. Il figure ici sur dix-huit titres, dont une partie s’est retrouvée sur le cinquième album pour Capitol Sounds Like Gene Vincent. Les saxophones ténors hurlants étaient à la mode dans le rock instrumental en 1958. Il est bien possible que ce soit la raison qui ait poussé Gene à engager Kelso. On les retrouve en particulier dans les instrumentaux à succès de Duane Eddy (dont l’influent «?Rebel Rouser?» était un tube de l’été 1958), Bill Justis («?Raunchy?», 1957) ou des Champs («?Tequila?», 1958)7.

Quoi qu’il en soit, toujours menés par le pianiste Clifton Simmons, Gene et ses Blue Caps à géométrie variable étaient capables de graver de grands moments comme Vincent’s Blues, le classique Say Mama ou The Night Is So Lonely (cosigné par Gene et son pianiste). Plusieurs titres de cette période étaient particulièrement marqués par le rock afro-américain (Ready Teddy, Maybellene) et le blues (Vincent’s Blues), auxquels les Blue Caps apportaient une forte couleur country/rockabilly. Et une influence afro-caribéenne cette fois pour Maybe et My Heart où l’on entend une présence du rythme boléro espagnol/cubain alterné avec des passages de pur rock.

Crazy Times

Gene et Darlene vivaient en Oregon et ont donné naissance à Melody Jean en avril 1959. Avec de trop rares compositions originales, le point fort de Gene Vincent restait à l’évidence sa voix, toujours touchante et sensuelle (le You Are the One for Me presque doo-wop composé par le pianiste Clifton Simmons). Car quels que soient ses musiciens, sur The Night Is So Lonely, Say Mama, Be-Bop Boogie Boy, Anna Annabelle ou l’une des meilleures versions jamais gravées de Over the Rainbow, Vincent brille au moins autant que son concurrent numéro un, Elvis Presley. Comme lui Presley s’aventurait de plus en plus sur des terrains plus grand public que le rock, comme les ballades. Mais la superstar avait pour lui un imprésario à la poigne de fer, une organisation impeccable et une maison de disques extrêmement active. Inversement, toujours ombrageux et difficile à vivre Gene Vincent l’ancien marin (dans la marine américaine les navigants sont appelés les «?blue caps?») n’inspirait pas confiance et menait sa barque seul. Il quitta l’agent texan McLemore et continua les concerts en embauchant les musiciens de première partie pour l’accompagner. Il arrivait aussi qu’il engage les Silhouettes, dont le batteur Clayton Watson lui a présenté le guitariste Jerry Merritt. Ils partirent ensemble tourner trois semaines au Japon, où Gene a été accueilli par des milliers d’admirateurs en délire à l’aéroport. À leur retour, ils ont enregistré en août 1959 ce qui donnera l’album Crazy Times, près d’un an après les séances d’octobre 58. Ils étaient entourés par des pros : Jackie Kelso, Jimmy Johnson au piano, le grand contrebassiste de jazz Red Callender, Sandy Nelson à la batterie et les Eligibles, célèbre groupe de choristes de studio dirigé par Ron Hicklin à Los Angeles.

Wild Cats

Mais le public américain boudait de plus en plus Gene Vincent. Après un concert à l’Olympia de Paris le 15 décembre 1960 il partit en Angleterre où le rock était de plus en plus apprécié. C’est le producteur de spectacles Larry Parnes qui avait proposé à Gene d’organiser une longue tournée en Grande-Bretagne. L’impact d’Elvis Presley et de films comme Graine de violence (Blackboard Jungle, Richard Brooks, 1955) avec Sidney Poitier construisait peu à peu une culture rock marginale dans la nouvelle génération des adolescents britanniques. Après l’énorme succès de la version de «?Rock Island Line?» par le précurseur Lonnie Donnegan en 1956, les disques de Bill Haley, Buddy Holly, Little Richard et Elvis Presley ont eu du succès dans l’île européenne. Be-Bop-a-Lula était monté au n°16 des ventes britanniques en août 1956 et Gene Vincent y était considéré comme une légende. Des chanteurs de rock anglais pionniers, comme Wee Willie Harris puis Tommy Steele, copiaient le rock américain et ont surgi en 1957. La demande du jeune public était réelle et d’autres artistes sont venus y répondre, notamment sous la férule de l’imprésario Larry Parnes, qui lança Marty Wilde en 1957, Vince Eager, Billy Fury et plusieurs autres en 1958. Parnes organisait aussi des auditions, des concerts et des tournées. Gay, flamboyant, autoritaire, il donnait à ses poulains des chansons écrites par des professionnels et se préoccupait surtout de choisir de jeunes hommes physiquement attirants qui pouvaient plaire aux adolescentes. Leur musique lui importait peu : il visait des activités télévisuelles, cinématographiques ou de music-hall et soignait surtout leur image, une apparence dans l’esprit «?teen idol?» américain (Ricky Nelson, Paul Anka, Pat Boone) de l’époque. Il affublait ces ordinaires adolescents anglais de pseudonymes «?sauvages?» comme Marty «?Wilde?» et les habillait de façon originale et séduisante afin d’accéder facilement à l’émission de télévision rock Oh Boy! produite et présentée par Jack Good. Leur musique était le plus souvent insipide, avec quelques exceptions comme le talentueux Georgie Fame, lui aussi lancé par l’essentiel Larry Parnes.

«?Quand j’ai vu Georgie Fame pour la première fois je me suis dit «?j’aimerais chanter aussi bien que lui et aller aussi loin.?»

— Mick Jagger8

L’Anglais Tony Sheridan, qui en 1961 enregistrera accompagné par les jeunes Beatles, a également fait surface en 1958. D’autres rockers britanniques ont fait leurs débuts en 1959, parmi lesquels Vince Taylor et Screamin’ Lord Sutch (dont les premiers enregistrements étaient produits par un autre gay qui soignait l’image de ses produits, Joe Meek)9. Tous copiaient le rock américain, auquel ils empruntaient une bonne partie de leur répertoire, et cultivaient ses mythes naissants. Avec «?Move It?» en 1958, Cliff Richard a été le premier rocker anglais à obtenir un véritable succès dans ce style. Cliff Richard était accompagné par les Shadows, un groupe qui en 1960 deviendrait célèbre avec l’instrumental «?Apache?», dont le son de guitare était à l’évidence influencé par celui de Cliff Gallup sur Be-Bop-a-Lula et d’autres titres des Blue Caps10. En plus de ses activités sur la chaîne ABC de ITV, Jack Good était le manager de Tommy Steele et Adam Faith qu’il a lancés en 1958 et représentait aussi Cliff Richard. Good produisait les émissions de télévision qui ont fait découvrir le rock au public britannique. Il travaillait avec Larry Parnes, dont il invitait volontiers les artistes à la télévision. En décembre 1959 Jack Good présentait la très populaire émission hebdomadaire du samedi soir Boy Meets Girls, où l’on pouvait voir Marty Wilde régulièrement. Larry Parnes avait proposé à Gene Vincent d’être accompagné sur scène par les Wild Cats, le groupe de son poulain Marty Wilde. On peut les écouter ici sur six titres enregistrés pour les besoins de la radio en mars 1960, notamment dans une version inspirée du standard de George Gershwin, Summertime.

Cuir Noir

Le sixième album Crazy Times est sorti le 1er janvier 1960. Avec ses mélodies accrocheuses il était à la fois très moderne et fidèle à l’esprit du rock n’ roll. Les paroles alternent entre insolence et innocence, drame et comédie : She She Little Sheila, Big Fat Saturday Night, Everybody’s Got A Date But Me, Mitchiko From Tokyo... une fois de plus Gene Vincent proposait une musique de grande qualité.

Quand il est arrivé à Londres quelques jours avant noël 1959, il est apparu dans Boy Meets Girls avec les Wild Cats. Souhaitant que les rockers anglais habillés avec style pour les caméras ne fassent pas d’ombre au chanteur américain, Jack Good avait demandé à Gene Vincent d’adopter un spectaculaire costume de cuir noir (suggéré par Larry Parnes ?) des pieds à la tête, gants de cuir de moto inclus, avec médaille et chaîne autour du cou. Rappelant l’image du motard rebelle joué par Marlon Brando dans le classique du cinéma L’Équipée sauvage (The Wild One, László Benedek, 1953) qui avait contribué à façonner l’image subversive et menaçante du rock outre-Atlantique, Gene adopta son nouveau costume de scène pour toute la tournée. En ces temps d’avions à hélice, aucun rocker américain n’avait encore été chanter en Grande-Bretagne. L’arrivée télévisée d’un grand nom américain du genre suscita beaucoup de passions et Gene Vincent eut un impact important en Angleterre.

«?Quand on a vu Gene Vincent arriver, on a vu le cuir arriver avec lui. Il a été le premier à porter du cuir noir dans le rock. Vince Taylor ? Il n’a été qu’un des premiers à le copier. Quand je les ai vus, Gene était la version originale, et Vince Taylor était la copie.?»

— Ian «?Lemmy?» Kilmister (Motörhead)11

Eddie Cochran, Johnny Kidd, Lou Reed avec le Velvet Underground, puis Jim Morrison avec les Doors ont porté des pantalons de cuir noir et même Elvis Presley, surgi comme Gene en total look cuir noir lors de son historique retour télévisé en 1968. Quant aux Beatles, ils ont été auditionnés à Liverpool par Larry Parnes en mai 1960. Ils adoptèrent eux aussi le blouson de cuir noir et posèrent ainsi à Hambourg en octobre. Un an plus tard, ils rencontreraient leur manager Brian Epstein, — un troisième gay clé dans l’histoire du rock anglais — qui, à l’inverse de Larry Parnes cultivant l’image rebelle du rock, les convaincra de porter des costumes cravate consensuels, icones de la Beatlemania de 1963-1966.

Arrivé le 10 janvier 1960 à Londres, Eddie Cochran partit immédiatement sur la route avec Billy Fury, Joe Brown et la tête d’affiche Gene Vincent. Tous étaient accompagnés par les Wild Cats de Marty Wilde. Comme tous les musiciens ils disposaient d’une chambre pour deux et Gene et Eddie partagèrent leur chambre d’hôtel pendant des mois. Les deux Américains étaient inséparables ; Gene Vincent, boîteux, gros buveur et affecté par les déboires de sa carrière en chute libre, s’appuyait sur son ami Eddie, plus solide. Le séjour fut très éprouvant mais triomphal. Les enregistrements réalisés pour la BBC en mars témoignent de la qualité de leur musique. Après quatre mois de tournées et un ultime concert à Bristol, Sharon la conjointe d’Eddie, Gene, Eddie et le régisseur Patrick Thompkins prirent enfin un taxi pour l’aéroport de Londres, situé à plus de cent cinquante kilomètres de là. Conduite à tombeau ouvert par un jeune chauffeur inexpérimenté, la voiture sortit de la route de campagne. Eddie Cochran mourut d’une blessure à la tête le lendemain matin, lundi de Pâques 1960. Il avait vingt et un ans12.

Bien que bien classés dans les meilleures ventes en Angleterre, Wild Cat puis My Heart n’ont pas été commercialisés aux États-Unis. Gravement blessé au bassin, au bras et à la jambe dans l’accident, et dévasté par la mort de son ami, Gene Vincent resta à Londres où le public l’appréciait. Il enregistra quelques jours aux studios EMI d’Abbey Road avec le groupe de Georgie Fame, les Beat Boys. Pistol Packin’ Mama fut gravé selon un arrangement imaginé par Cochran et Norrie Paramor arrangea un orchestre pour le déchirant Weeping Willow qui évoque Eddie.

Twist

Après la convalescence de Gene pendant l’été, Darlene mit au monde Gene Junior en octobre. Paru début janvier 1960, l’album de Gene Vincent Twist Crazy Times était initialement nommé Crazy Times comme la chanson qu’il contient. À la suite de l’énorme succès «?Let’s Twist Again?» de Chubby Checker à la rentrée, la mode montante du twist, une danse très populaire mieux acceptée que le rock par les parents, incita EMI à ajouter le mot «?twist?» au titre de l’album. Il montera au n°12 des ventes au Royaume Uni, le seul des albums de Gene classé dans ce pays. Capitol/EMI mirent en avant cette image twist, qui ne plaisait pas beaucoup aux fans puisque le twist était une forme de rock commerciale et consensuelle. Vincent donna des concerts en Afrique du Sud où il fit la connaissance d’une chanteuse de 16 ans, Jackie Frisco, belle-sœur de Mickie Most auquel il avait emprunté ses musiciens les Play Boys. Il revint en Angleterre où il se produit à la même affiche que Johnny Kidd accompagné par les Echoes. Darlene le quitta en avril 1961, le privant de ses deux enfants. De plus en plus erratique, Gene Vincent était accompagné par Sounds Incorporated avec John St. John à la guitare. Il enregistra avec eux à Abbey Road, où Paramor dirigea aussi l’orchestre qui donna un nouveau classique, Love of a Man. En juillet, Gene se produisit à la Cavern de Liverpool, où les Beatles n’ont pas raté une miette du concert. Rentré en Californie, il fit une apparition en blanc sur scène à Hollywood où il interpréta Spaceship To Mars dans It’s Trad Dad (Richard Lester, 1962). Il tourna ensuite en Italie et chanta deux semaines en juillet au Star Club de Hambourg où il fut accompagné le premier soir par les jeunes Beatles, qui remplaçaient Sounds Incorporated arrivés en retard. Gene Vincent vécut beaucoup en Europe pendant les dix années qui lui restaient à vivre. Il aura notamment un fort impact en France en 1963. Toujours à Abbey Road, à la demande d’EMI il enregistra une version de son classique Be-Bop-a-Lula dans le style twist. C’est le dernier titre qu’il enregistra pour Capitol/EMI. Il n’eut aucun succès.

Bruno BLUM

Merci à Alexis Frenkel, Brian Setzer, Slim Jim Phantom, Lee Rocker, Jacky Chalard et Jean-William Thoury.

© FRÉMEAUX & ASSOCIÉS 2015

1. Lire le livret et écouter dans cette collection le volume 1 de Elvis Presley face à l’histoire de la musique américaine 1954-1956 (FA5361) où les versions originales de tous les morceaux qu’il a repris sont alternées avec ses propres enregistrements, et l’anthologie Rockabilly 1951-1960 (FA5423).

2. Le livret du volume 2 Elvis Presley face à l’histoire de la musique américaine (FA5383) dans cette collection explique plus en détail la vague réactionnaire qui a attaqué les artistes de rock en 1957-1958.

3. Lire le livret et écouter The Indispensable Eddie Cochran 1955-1960 (FA5425) dans cette collection.

4. Écouter The Indispensable Chuck Berry 1955-1961 (FA5409) dans cette collection.

5. Écouter The Indispensable Bo Diddley 1955-1960 (FA5376) et 1959-1962 (FA5406) dans cette collection.

6. Écouter The Indispensable Little Richard à paraître dans cette collection.

7. Retrouvez Duane Eddy, Bill Justis et les Champs sur l’anthologie Rock Instrumentals Story 1934-1962 (FA5426) dans cette collection.

8. Mick Jagger à l’auteur, 1980.

9. Retrouvez Vince Taylor et Screamin’ Lord Sutch sur l’anthologie The Roots of Punk Rock Music 1920-1962 (FA5415) dans cette collection.

10. Retrouvez «Apache» par les Shadows sur Electric Guitar Story 1935-1962 (FA5421) et Rock Instrumentals Story 1934-1962 (FA5426) dans cette collection.

11. Lemmy à l’auteur en 1979.

12. Lire le livret et écouter The Indispensable Eddie Cochran 1955-1960 (FA5425) dans cette collection.

The Indispensable Gene Vincent VOLUME 2 1958-1962

By Bruno Blum

The titles by Gene Vincent and his Blue Caps in our first volume deploy a magic which in retrospect makes their reputation as kings of rockabilly practically unarguable. With the extraordinary guitar of Cliff Gallup replying to Gene’s vocal charm, their 1956 vintage, from “Be-Bop-a-Lula” to “Cruisin’”, marked American popular music history for ever. Gene and his group were marginal, brilliant rebels, and their authenticity and talent enabled the spirit of rock to triumph. As our Rockabilly 1951-1960 anthology in this collection shows, there were many splendid recordings in the rockabilly style around, giving the Blue Caps supremacy all the more merit as they were competing with giants such as Johnny Cash, Johnny Burnette, Carl Perkins, Lew Williams, Jerry Lee Lewis, Buddy Holly and Elvis Presley — but, quite objectively, none of the latter, not even Elvis, managed to record as many defining, pure rockabilly masterpieces as Gene Vincent did.1

Beautiful Loser

In 1956, after a successful first few months, the departure of the dazzling guitarist Cliff Gallup was a major blow to the band’s singer. The situation was already critical, as Gene had been abandoned by Sheriff Tex, the disc-jockey manager who had secured Gene’s contract with Capitol and also orchestrated the immense success of Be-Bop-a-Lula (even though, he still ensured that some of the title’s royalties would come his way). Life was very hard for Gene during this period: he had to endure continuous touring despite his severely handicapped left leg; his marriage suffered from his repeated absences; and there had been no hits of any consequence since “Be-Bop-a-Lula” in the summer of ‘56. To cap it all, Gene Vincent was drinking heavily, which seriously complicated his professionalism (and his love-life).

“He had a permanent limp after his motorcycle accident which caused him to drink and take morphine; his life was fraught with stress and health problems; bad luck plagued him. But despite it all, his remarkable sensitivity allowed him to reach summits of artistry. He had an endearing character reminiscent of James Dean, but he was paranoid, unstable, and his own worst enemy, wearing out love, friendship and goodwill with suicidal consistency.”

— Jean-William Thoury, Le Dictionnaire du rock (Robert Laffont, 2001)

With Gene left to his own devices, his career quickly suffered from a lack of support and guidance and it began to go astray in 1956. It would eventually lead to his tragic death at the age of thirty-six, and the artist’s waywardness lent substance to the myth of Gene Vincent as one of rock’s “beautiful losers”: he died young, broken by cruel, thankless indifference. The serious car accident which cost his friend and associate Eddie Cochran his life in 1960 did nothing to smooth matters: Gene’s leg was shattered a second time. And then in 1961 a second devastating divorce deprived him of his two children. Even so, the weight of his legend sometimes makes you forget that, in the shadows of “Be-Bop-a-Lula”, Gene Vincent (b. 11 February 1935, d. 12 October 1971) left to posterity a number of recordings as splendid as they are little-known, and this second volume devoted to his Capitol period covers the records he made from 1958 to 1962. While the splendour of the original Blue Caps remains unsurpassed, the remainder of Gene’s work here is excellent, as shown in such classics as Say Mama, Crazy Beat, I’m Gonna Catch Me a Rat or the inspired version of Summertime which was recorded by the BBC in London. While it’s true that criticism can be levelled against various producers and also some of those accompanying him, the young Gene Vincent’s remarkable performances in this set still rate alongside the greatest.

A Gene Vincent Record Date

The ultimate sessions by the original Gene Vincent and his Blue Caps, with Cliff Gallup on guitar, took place in October 1956. A complete issue of their 35 studio titles (plus two live performances) constitute the nec plus ultra in rockabilly, and they appear in our first volume. Completing them in Volume 2 we have 31 titles by the second Blue Caps with guitarist Johnny Meeks: with an electric bass, a new lead-guitar, back-up vocalists and an evolved, more diversified style, this second phase shows the clear change in the band’s sound as early as the end of 1956. They were moving away from the canons of original rockabilly in the same way as their contemporaries Buddy Holly, Eddie Cochran, Elvis Presley, etc. The first sessions with Meeks on guitar came in June ‘57. The witch-hunt against rock artists in this period encouraged groups to soften their styles and broaden their repertoire: no doubt urged on by Capitol, Gene Vincent followed suit, and the strong presence of a vocal group here — a direct result of the influence of the Jordanaires, the white gospel group on so many Presley records — is just one aspect of this change. But while Gene Vincent had always been a moving ballad-singer, his direction remained resolutely rock.

Elvis Presley was drafted on March 24th 1958, and from then on his records would leave rock partly to one side and take on various other styles. While the Elvis phenomenon continued almost unabated during his two-year absence under the flag, rock had a very bad reputation in 1958 and every artist in the genre suffered from it. And so did musicians.2 This set begins in March 1958, just when Presley made headlines with the draft. A new era in rock was beginning, and Gene Vincent would take the trend even further.

The McLemore concert agency in Dallas, Texas, had set up an exhausting schedule for the Blue Caps and after three months out on the West Coast, they released their third album, Gene Vincent Rocks and the Blue Caps Roll, on March 18th 1958. Drummer Dickie Harrell had been the last original Blue Cap to throw in the towel, and he left to settle down with the sister of backup-singer Tommy Facenda: it was a new disappointment for Gene, who brought in Judey Gomez and then Clyde Pennington as his replacement. Johnny Meeks was something of a dilettante (he was close to Gene but didn’t care much for tours), and pianist Clifton Simmons became the group’s leader; they recorded new titles at the end of March, including an elegant new version of Five Feet of Lovin’ which opened the Record Date album. The more or less recurrent changes in personnel brought Gene closer to his friend Eddie Cochran, another major rock singer/songwriter whose career soared in 1958. They’d met on the set of Frank Tashlin’s 1956 film The Girl Can’t Help It, and their friendship had grown during a memorable Australian tour in October 1957, when Gene and Eddie suddenly became the tour’s stars after bill-topper.

Little Richard quit the tour prematurely, leaving Vincent the headline and Cochran playing before him. That night on October 11, 1957 Little Richard was singing in a 40,000-seater Sidney arena and saw an unidentified flying object, a ball of fire (he will later assume that it was the first-ever artificial satellite, USSR’s Sputnik I, but that was sent in orbit on October 4). Believing it was a celestial sign, he left the piano in the middle of a song and left the stage out of the blue. He’d taken his decision: he let go of everything and was going home to devote his life to the Church. Little Richard broke the news the next day and he flew home with his dumbstruck band right away, losing half a million 1957 dollars in Australian fees. A few days later, according to him the plane that was meant to fly them home to America crashed in the sea, which he thought was another godly sign.

As for Californian singer Eddie Cochran, he was a remarkable studio musician before he reached twenty, with a personal style as a singer/composer, regularly playing as an accompanist and rock or country music soloist. On January 12th he recorded his own song “Jeannie Jeannie Jeannie”, and in May he cut one of his greatest hits, the excellent “Summertime Blues”. Cochran appears as a backing vocalist on the first eight titles here (CD1) and can also be heard in the companion Volume One. His deep voice comes through clearly on the album A Gene Vincent Record Date, especially in the ballad Wayward Wind, a reprise of Tex Ritter’s 1956 country hit. Cochran’s presence had a major influence on Gene’s sound in this period, and the two friends (Gene was only three years older) exchanged ideas for arrangements. In the period that followed, Cochran’s recordings would be marked by a similar sophistication, especially in the backing-vocals.3 Eddie can also be heard in Now Is the Hour and other titles (cf. discography) included in Volume One. These sessions produced their share of future classics: Rocky Road Blues, “Git It”... Gene’s companions Peek and Facenda were tempted by solo careers but returned for the film Hot Rod Gang (Lew Landers, 1958, with John Ashley and Jody Fair). Gene Vincent had a small role in the film, and sang “Dance In The Street”, “Baby Blue” and “Dance To The Bop” (cf. Volume One).

In May 1958, Gene married 19 year-old Darlene Hicks, who already had a daughter, Debbie, then aged two. Darlene often went on tour with Gene; she didn’t like him going away and was torn between her little daughter and her husband. It was Gene’s second marriage (in 1955 he’d married Ruth Ann Hand when she was 15.) The group toured America from March to October 1958; Meeks decided to return home (he was replaced by Howard Reed), only returning in October went they went into the studios. Led by pianist Clifton Simmons, the new Blue Caps continually changed personnel. Tension was rife, but the fourth album A Gene Vincent Record Date (released in November ‘58) remains one of the best productions of the late Fifties, and his fans saw it as his most complete (and most successful) work, and also his most mature effort. It was certainly the best record he made in Hollywood’s Capitol Tower studio: refined and carefully prepared, the LP was a much cooler version of the volcano which constituted his debuts. The sound was characte-ristic of the period, rich and lively with loads of reverb and back-up voices. It had influence, too, and not just on Eddie Cochran. This type of choral sound would be found in Vince Taylor’s records (“I’ll Be Your Hero” or “Wat’cha Gonna Do”, 1960) which carried a Gene Vincent influence, and it spread as far as France, where Eddy Mitchell’s “Chaussettes Noires” recorded a French-language version of Be-Bop-a-Lula in 1960. The single Say Mama/Be Bop Boogie Boy was released at the same time as the LP, both of them excellent, but neither had much impact.

Sounds Like Gene Vincent

Rock had a bad reputation in 1958. Elvis was still in the Army but records continued to come out and sell, even though they put more and more distance between Elvis and rock. By the time Buddy Holly died on February 3rd 1959 at the age of only 22, Eddie Cochran and Gene Vincent had slowly become the two main white singers who genuinely represented rock. The Everly Brothers and Ricky Nelson had hits, but their music was much softer: it suited radio-formats not caring much for edgy, exciting, fast-tempo numbers, i.e. rock. Even the king, Chuck Berry, had to slow down.4 Bo Diddley was increasingly successful but his highly individual style set him apart from the rest.5 As for Little Richard, he “got religion” in October ‘57.6 And the following year saw a commercial war raging between radio stations and juke-box distributors, entailing a payola scandal which decimated the ranks of rock DJs, radio shows and consequently rock-singers also. Gene Vincent had two strong singles, Rocky Road Blues/”Yes I Love You Baby” in July and “Git It”/”Little Lover” in September, but they weren’t commercial hits. Eddie Cochran’s “Summertime Blues” was one of the rare genuine rock songs to reach the top of the charts that summer.

In this difficult context, and despite the quality of his studio-efforts, Gene Vincent found himself obliged to slave away on tours from California to Canada. He still filled rooms, surrounded by professional musicians who were competent but more interested in their fee than in any musical cause; and they didn’t stay long, hastened by Gene’s erratic behaviour and their working-conditions. Peek, Facenda and Johnny Meek, the band’s mainstay, (replaced at concerts by Howard Reed) usually refused point blank to follow Gene on the road, returning only to record in the autumn. Others weren’t available, and the successive departures and returns of Mac Lipscomb, Facenda, Grady Owen, Paul Peek and Johnny Meeks, amongst others, were a plague on Gene’s career.

On the other hand, some of the new partners he was obliged to find made for a richer return to recording, with musicians in his pick-up bands provoking new ideas and experiments. In October ‘58 a new week of studio dates preceded the release of the Record Date LP which revealed tunes recorded that March. Gene had hired saxophonist Jackie Kelso, a Johnny Otis alumnus who’d worked with jazzmen Duke Ellington, Barney Bigard, Lucky Thompson and a number of other artists with varying backgrounds. Kelso’s sax palpably changed the group’s sound, and he plays here on 18 titles, some of which turned up on Gene’s fifth Capitol album, Sounds Like Gene Vincent. Screaming tenors were in fashion in instrumental rock dated 1958, and this was probably what moved Gene to hire Kelso. Tenor saxes can be heard in Duane Eddy’s instrumental hits, like the influential “Rebel Rouser” (a summer hit that year), or Bill Justis’ “Raunchy” (1957) and The Champs’ “Tequila” (1958).7

Tenors apart, Gene, and his Blue Caps led by pianist Clifton Simmons (with varying line-ups) still showed themselves capable of recording great moments: there were Vincent’s Blues, the classic Say Mama or The Night Is So Lonely (written by Gene and Simmons). Several titles from this period were particularly marked by Afro-American rock (Ready Teddy, Maybellene) and the blues (Vincent’s Blues), with the Blue Caps adding a strong country/rockabilly colour, and in the case of Maybe and My Heart an Afro-Caribbean flavour thanks to a strong presence of Spanish/Cuban bolero rhythms alternating with passages of pure rock.

Crazy Times

Gene and Darlene were living in Oregon when their daughter Melody Jean was born in April 1959. Gene Vincent only rarely wrote original songs in this period and his strongpoint was obviously his voice, always moving and sensual (as on You Are the One for Me, an almost-Doo-Wop title written by Clifton Simmons). Regardless of the musicians, the titles The Night Is So Lonely, Say Mama, Be-Bop Boogie Boy, Anna Annabelle, or, again, one of the best versions ever recorded of Over the Rainbow, Vincent’s voice shines through at least as brilliantly as that of his number-one rival, Elvis Presley. Like Gene, Presley was venturing further and further into domains which reached mass audiences, especially ballads. But Presley the superstar had an iron-fisted impresario working on his behalf, with an impeccable organization and a very active record-company behind him. Gene Vincent, on the other hand, was still hard to live with and quick to take offence; he’d been in the Navy (“Blue Caps” came from the name given to seafaring personnel) and he didn’t inspire confidence. Gene sailed his boat alone. He quit his Texan agency (McLemore) and continued giving concerts with pick-up bands hired from among the musicians who opened for him. He also took on The Silhouettes, whose drummer Clayton Watson introduced Gene to guitarist Jerry Merritt. They went to tour in Japan for three weeks, and Gene was given a delirious welcome at the airport. On their return they recorded the album Crazy Times, (August ‘59), almost a year after the previous sessions. They had pros in the group, too: Jackie Kelso, Jimmy Johnson on piano, the great jazz bassist Red Callender, Sandy Nelson on drums, and also The Eligibles, the famous studio vocal group led by Ron Hicklin in Los Angeles.

Wild Cats

American audiences, however, were increasingly aban-doning Gene Vincent. After a concert at The Olympia in Paris on December 15th 1960, Gene went to England, where rock was “in”. It was promoter Larry Parnes who had offered Gene a lengthy British tour; the impact of Presley, and films like Richard Brooks’ Blackboard Jungle (1955) which featured Sidney Poitier, had slowly built up a marginal rock culture among the new generation of British teenagers. After the enormous success of Lonnie Donnegan’s version of “Rock Island Line” in ‘56, records by Bill Haley, Buddy Holly, Little Richard and Elvis Presley became hits in Britain: when Be-Bop-a-Lula went to N°16 in the British charts in August ‘56, Gene Vincent became a legend for many. Pioneering English rock-singers like Wee Willie Harris or Tommy Steele sprang up in 1957, copying American rock. Demand from young audiences was very real, and many artists came to the fore (especially those represented by Larry Parnes, who launched Marty Wilde in 1957, Vince Eager, Billy Fury and several others in 1958.) Parnes also set up auditions, concerts and tours. Gay, flamboyant and authoritarian, he gave his “stable” songs written by professionals, and took great care to choose good-looking young men who would be attractive to teenage girls. He didn’t care about the music: what mattered to Larry was the size of the audience, whether his artists were on television, on the silver screen, or onstage in a music-hall. He took care of their image, which was the look of the American “teen-idol” at the time (namely Ricky Nelson, Paul Anka or Pat Boone). He gave ordinary English teenagers “wild” stage-names (Marty “Wilde”…) and dressed them in original, seductive stage-outfits to make it easier for them to appear on the hit TV show Oh Boy! whose producer/presenter was Jack Good. Their music was generally insipid, but there were exceptions: Georgie Fame had talent (the essential Larry Parnes had him under his wing). “The first time I saw Georgie Fame I thought, ‘I’d like to sing as good as he can and go just as far’,” said Mick Jagger.8

Another English rocker, Tony Sheridan, who recorded with The Beatles in 1961, also emerged in 1958; others followed him in 1959, among them Vince Taylor and Screamin’ Lord Sutch (whose first records were produced by another gay who took care over his “products” and their image: Joe Meek.9 All of them copied American rock and borrowed a good part of their repertoire from it, cultivating these burgeoning myths. With “Move It” in 1958, Cliff Richard was the first English rocker to have a genuine hit in this style. Cliff was accompanied by The Shadows, a group which in 1960 became famous with its instrumental hit “Apache”, with a guitar-sound obviously influenced by Cliff Gallup’s playing on Be-Bop-a-Lula and other Blue Caps titles.10 On top of his activities on ITV television, Jack Good managed both Tommy Steele and Adam Faith, whom he launched in 1958, and he also represented Cliff Richard. Good produced the TV shows which caused British audiences to discover rock. He worked with Larry Parnes, whose artists were naturally invited to do his shows. In December 1959 Jack Good introduced the very popular Saturday evening show Boy Meets Girls, and Marty Wilde was a regular guest. It was Parnes who suggested that Marty’s group The Wild Cats might accompany Gene Vincent, and you can hear them on six titles here, all recorded for radio in March 1960; they include an inspired version of the George Gershwin standard, Summertime.

Black Leather

The sixth album Crazy Times was released on January 1st 1960; its catchy melodies were both modern and faithful to the spirit of rock ‘n’ roll. The lyrics alternated between insolence and innocence, drama and comedy, and with She She Little Sheila, Big Fat Saturday Night, Everybody’s Got A Date But Me and Mitchiko From Tokyo Gene Vincent once again provided quality music.

When he arrived in London a few days before Xmas 1959 he appeared on Boy Meets Girls with the Wild Cats. Producer Jack Good didn’t want the stylishly dressed English rockers to put his guest American singer in the shade, and so he asked Gene to dress from head to foot in a spectacular black leather costume (maybe suggested by Larry Parnes?), and wear leather motorcycle gloves together with a chain around his neck. Gene’s new apparel recalled the image of Marlon Brando’s “rebel-biker” hero in the film classic The Wild One (László Benedek, 1953), which had contributed to shape the menacing, subversive image which rock carried on the other side of The Atlantic, and Gene adopted the new black stage-gear for the rest of his tour. In those days — aeroplanes still had propellers — no American rocker had ever sung in Britain before: the televised arrival of a great American rock-name aroused a lot of excitement, and Gene had a major impact: “When they saw Gene Vincent come in, they saw leather come in. He was the first to wear black leather in rock. Vince Taylor? He was just one of the first to copy him. When I saw them, Gene was the original version and Vince Taylor was the copy.” (Ian “Lemmy” Kilmister of Motörhead).11

Eddie Cochran, Johnny Kidd, Lou Reed with the Velvet Underground, and then Jim Morrison with the Doors: they all wore black leather pants, even Elvis Presley, who sprang up, like Gene, with a total leather look in 1968 on his historic televised return. As for The Beatles, when they were auditioned by Larry Parnes in Liverpool in May 1960 they wore black leather jackets, and that was how they were dressed when they landed in Hamburg that October. A year later they met their manager Brian Epstein (a third gay key-figure in English rock history): whereas Parnes had cultivated rock’s “rebel” image, Epstein convinced the Beatles, in a spirit of consensus, to wear the suits and ties which became icons of the Beatle-mania which reigned from 1963 to 1966.

When Eddie Cochran arrived in London on January 10th 1960 he immediately went on tour with Billy Fury, Joe Brown and the show’s headliner Gene Vincent. They were all accompanied by Marty Wilde’s Wild Cats. Musicians usually all shared twin rooms, and Gene and Eddie roomed together for months. The two Americans were inseparable: Gene Vincent, dragging his leg, drank like a fish to drown his sorrows caused by a career going down the drain, and he needed a crutch to lean on. The crutch was his solid friend Eddie. Their stay in Britain was nerve-racking but triumphal, and the tapes made by the BBC in March show the quality of their music. After four months of touring, and after a final concert in Bristol, Sharon Cochran, Gene, Eddie and their road-manager Patrick Thompkins took a taxi to London Airport. It was almost a hundred miles away, and the driver, young and inexperienced, was travelling too fast. The car left the road and overturned. Eddie Cochran was seriously injured in the accident and died the next morning, on Easter Monday 1960, from his head-wounds. He was twenty-one.12

Although they were among the best-sellers in England, first Wild Cat and then My Heart were not released in America. Seriously injured in the accident — pelvis, arm, leg — and devastated by the death of his friend Eddie, Gene stayed in London where he was much-appreciated. He recorded over a few days at EMI’s Abbey Road Studios, with Georgie Fame’s group the Beat Boys. Pistol Packin’ Mama was recorded with an arrangement conceived by Cochran, and Norrie Paramor wrote the orchestral arrangement for the heartbreaking song Weeping Willow dedicated to Eddie’s memory.

Twist

After Gene spent the summer convalescing, Darlene Vincent gave birth to Gene Junior in October. Released the following January, Gene’s album Twist Crazy Times was initially titled Crazy Times after one of its songs; following the enormous success of Chubby Checker’s “Let’s Twist Again”, the Twist craze was gaining momentum — it was a popular dance; parents with teenage children accepted it better than rock — and this encouraged EMI to add the word “Twist” to the album’s original title. It went to N°12 in the British charts and was the only album by Gene to enter the hit-parade there. Capitol/EMI promoted the “twist” image, displeasing fans who saw the dance as a trendy form of commercial rock… Gene did some concerts in South Africa, where he met a sixteen year-old singer named Jackie Frisco (she was Mickie Most’s sister-in-law) and borrowed her musicians, the Play Boys. On his return to England he appeared on the same bill as Johnny Kidd, accompanied by the Echoes. Darlene left him in April 1961, taking their two children with her, and Gene’s behaviour became more and more erratic. He changed musicians again, playing with Sounds Incorporated (the guitarist was John St. John), and he also recorded with them at Abbey Road to produce yet another classic, Love of a Man. July saw him at the Cavern in Liverpool, where The Beatles didn’t miss a minute…

When he returned to California, Gene went onstage in Hollywood (dressed in white) to play Spaceship to Mars in Richard Lester’s film It’s Trad Dad (1962). He did another film in Italy, and then went to Hamburg for two weeks to sing at the Star Club, where he was accompanied on his first night by the young Beatles (Sounds Incorporated had turned up late). In the remaining ten years of his life Gene Vincent lived mostly in Europe (he was very popular in France in 1963), and when EMI requested that he return to Abbey Road to record a twist-version of his classic hit Be-Bop-a-Lula, it would turn out to be his last title for the Capitol/EMI label. It didn’t sell.

Bruno Blum, July 2013

Thanks to Alexis Frenkel, Brian Setzer, Slim Jim Phantom, Lee Rocker, Jacky Chalard and Jean-William Thoury.

© FRÉMEAUX & ASSOCIÉS 2015

1. Cf. booklet & music in Vol. 1 of Elvis Presley face à l’histoire de la musique américaine 1954-1956 (FA5361) where the original versions feature alongside his covers, and also the anthology Rockabilly 1951-1960 (FA5423).

2. The booklet enclosed with Vol. 2 of Elvis Presley face à l’histoire de la musique américaine (FA5383) has details of the reactionary attacks on rock artists in 1957/1958.

3. Cf. The Indispensable Eddie Cochran 1955-1960 (FA5425).

4. The Indispensable Chuck Berry 1955-1961 (FA5409).

5. The Indispensable Bo Diddley 1955-1960 (FA5376) & 1959-1962 (FA5406).

6. In The Indispensable Little Richard (future release).

7. Duane Eddy, Bill Justis and the Champs feature in Rock Instrumentals Story 1934-1962 (FA5426).

8. Mick Jagger speaking to the author, 1980.

9. Vince Taylor and Screamin’ Lord Sutch feature in The Roots of Punk Rock Music 1920-1962 (FA5415).

10. “Apache” by the Shadows appears in Electric Guitar Story 1935-1962 (FA5421) and in Rock Instrumentals Story 1934-1962 (FA5426).

11. Lemmy, speaking to the author in 1979.

12. Cf. The Indispensable Eddie Cochran 1955-1960 (FA5425).

Disc 1 : 1958

1. Five Feet of Lovin’ (Buck Peddy, Lonnie Melvin Tillis aka Mel Tillis)

2. SomeBody help me (Bob Kelly)

Gene Vincent and his Blue Caps: Vincent Eugene Craddock as Gene Vincent-v, rg; Johnny Meeks-lg; Grady Owen-rg; Clifton Simmons-p; Bobby Jones-b; Juvey Gomez-d; Paul Peek aka Paul Edward Peek Jr. aka Red, Tommy Facenda aka Bubba-hand claps, chorus vocals; Eddie Cochran-backing vocals. Produced by Ken Nelson. John Kraus, engineer. Capitol Tower, Hollywood, March 27, 1958.

3. Look What You Gone and Done to Me (Robert Lee Jones)

4. Hey Good Lookin’ (Hiram King Williams aka Hank Williams)

5. I Can’t Help It (If I’m Still in LOve With You) (Hiram King Williams aka Hank Williams)

6. Summertime (George Gershwin, DuBose Heyward)

Same as CD 1, track 1. March 28, 1958.

7. Now Is the Hour (Maewa Kalhan, Clement William Scott, Dorothy Stewart)

8. The Wayward Wind (Stanley Richard Lebowsky aka Stanley Lebowski, Herbert Newman as Herb Newman)

Same as CD 1, track 1. March 29, 1958.

9. Lonesome Boy (Tommy Baldwell)

10. You Are the One for Me (Clifton Simmons)

11. Maybe (John Lewis Carrell aka Johnny Caroll, Paulette Williams)

Gene Vincent and his Blue Caps: Vincent Eugene Craddock as Gene Vincent-v, rg; Johnny Meeks-lg; Jerry Singleton-rg; Clifton Simmons-p; Grady Owen-b; Clyde Pennington-d; Paul Peek, Tommy Facenda-v chorus, handclaps. Produced by Ken Nelson. Capitol Tower, Hollywood, October 13, 1958.

12. My Heart (John Joseph Burnette aka Johnny Burnette)

13. I Got to Get You Yet (John Joseph Burnette aka Johnny Burnette)

14. The Night Is So Lonely (Clifton Simmons, Vincent Eugene Craddock aka Gene Vincent)

Same as CD 1, track 9. October 14, 1958.

15. Beautiful Brown Eyes (Alton Delmore, Arthur Smith)

16. Rip It Up (John S. Marascalso aka John Marascalco, Robert Blackwell a.k.a. Bumps)

17. Maybellene (Charles Edward Anderson Berry aka Chuck Berry, Russ Fratto, Albert James Freed aka Alan Freed)

18. High Blood Pressure (Huey Smith aka Huey “Piano” Smith)

Same as CD 1, track 9. Add John Joseph Kelson, Jr. as Jackie Kelso-ts; Plas Johnson-bs. October 15, 1958.

19. Be Bop Boogie Boy (Vincent Eugene Craddock aka Gene Vincent)

20. In Love Again (Vincent Eugene Craddock aka Gene Vincent)

21. I Can’t Believe You Wanna Leave (Lloyd Price)

Same as CD 1, track 9. Add John Joseph Kelson, Jr. as Jackie Kelso-ts; Plas Johnson-bs on 19 & 21. October 16, 1958.

22. Who’s Pushing Your Swing (Charles Artice Glenn aka Artie Glenn)

23. Gone, Gone, Gone (Joseph Alfred Souter aka Joe South)

24. Anna-Annabelle (Clifton Simmons)

Same as CD 1, track 9. Add John Joseph Kelson, Jr. as Jackie Kelso-ts; Plas Johnson-bs. October 17, 1958.

Disc 2 : 1958-1960

1. Say mama (Johnny Meeks, Earl Theodore Baughman aka Country Earl aka Johnny Earl)

Same as CD 1, track 9. Add John Joseph Kelson, Jr. as Jackie Kelso-ts; Plas Johnson-bs. October 16, 1958.

2. My Baby Don’t ‘Low (adapted from “My Babe”; William James Dixon aka Willie Dixon, with lyrics modified by Vincent Eugene Craddock aka Gene Vincent)

Note: The original melody of Willie Dixon’s “My Babe” is based on the traditional spiritual “This Train”.

3. Important Words (Vincent Eugene Craddock aka Gene Vincent, William Douchette aka Bill Beauregard Davis aka Sheriff Tex)

4. I Might Have Known (Joseph Alfred Souter aka Joe South)

5. Over the Rainbow (Harold Arlan, Edgar Yipsel Harburg aka Yip Harburg)

Same as CD 1, track 9. Add John Joseph Kelson, Jr. as Jackie Kelso-ts; Plas Johnson-bs on 3; unknown xylophon on 5. October 20, 1958.

6. Vincent’s Blues (Vincent Eugene Craddock aka Gene Vincent)

7. Ready Teddy (John S. Marascalso aka John Marascalco, Robert Blackwell a.k.a. Bumps)

Same as CD 1, track 9. October 21, 1958.

8. She She Little Sheila (Jerry Lee Merritt aka Jerry Merritt, Dwight A. Pullen aka Whitey Pullen)

9. Ac-cEntu-ate the Positive (Hyman Arluck aka Harold Arlen, John Herndon Mercer aka Johnny Mercer)

10. Pretty Pearly (Don Johnson, Diane Johnson)

11. Darlene (Vincent Eugene Craddock aka Gene Vincent)

Vincent Eugene Craddock as Gene Vincent-v; Jerry Merritt-g; John Joseph Kelson, Jr. as Jackie Kelso-ts; Jimmy Johnson-p; George Sylvester Callender as Red Callender-b; Sandy Nelson-d; The Eligibles: Ron Hicklin, Stan Farber, Ron Rolla, Bob Zwirn-vocal chorus. Produced by Ken Nelson. Capitol Tower, Hollywood, August 2, 1959.

12. Why Don’t You People Learn to Drive (James Noble)

13. Greenback Dollar, Watch and Chain (Ray Harris)

14. Crazy times (Paul Schwartz aka Paul Hampton, Burt F. Bacharach)

Same as CD 2, track 8. August 4, 1959.

15. Wild Cat (Aaron Harold Schroeder, Walter Gold aka Wally Gold)

16. Right here on Earth (Charles Singleton aka Charlie “Hoss” Singleton)

17. Hot Dollar (Ollie Jones)

18. Big Fat Saturday Night (Donald Randolph aka Don Covay, John Berry, Luther Dixon)

Same as CD 2, track 8. August 5, 1959.

19. Mitchiko From Tokyo (Bobbie Carroll, Kirk Hansard)

20. Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain (Fred Rose aka Floyd Jenkins)

21. Everybody’s Got a Date But me (Dwight A. Pullen aka Whitey Pullen)

Same as CD 2, track 8. August 6, 1959.

22. Wild Cat (Aaron Harold Schroeder, Walter Gold aka Wally Gold)

23. My Heart (John Joseph Burnette aka Johnny Burnette)

Vincent Eugene Craddock as Gene Vincent-v; The Wild Cats: Jim Sullivan-lg; Tony Belcher-rg; Brian Locking-b; Brian Bennett-d. Playhouse Theatre BBC Studio, Northumberland Avenue, City of Westminster, London, circa March 1-3, 1960. Broadcasted on Saturday, March 5, 1960, on the Saturday Club Show hosted by Bernie Andrews.

Disc 3 : 1960-1962

1. Summertime (George Gershwin, DuBose Heyward)

2. Say Mama (Johnny Meeks, Earl Theodore Baughman aka Country Earl aka Johnny Earl)

Same as CD 2, track 22.

3. Rocky Road Blues (William Smith Monroe aka Bill Monroe)

4. Be-Bop-a-Lula (Vincent Eugene Craddock aka Gene Vincent, William Douchette aka Bill Beauregard Davis aka Sheriff Tex)

Same as CD 2, track 22. Broadcasted on Saturday, March 12, 1960.

5. Pistol Packin’ Mama (Al Dexter, arranged by Ray Edward Cochrane aka Eddie Cochran)

Gene Vincent and the Beat Boys: Vincent Eugene Craddock as Gene Vincent-v; The Blue Flames: Billy McVay-ts; Colin Green-lg; Clive Powell as Georgie Fame-p; Vincent Cooze-b; Red Reece-d.

6. Weeping Willow (Darlene Craddock aka Debra Lynn)

Gene Vincent and the Norrie Paramor Orchestra and chorus.

Vincent Eugene Craddock as Gene Vincent-v; unknown orchestra personnel; unknown chorus v. Orchestra conducted by Norrie Paramor. Abbey Road Studios, London, May 5, 1960.

Note: This song was dedicated to Gene Vincent’s mother. Written shortly after the car accident that killed Eddie Cochran and severely injured Gene Vincent, it is officially credited to Debra Lynn, a pseudonym for Darlene Craddock (Gene’s second wife). This pseudonym is likely to refer to Debbie (“Debra”), who was Gene’s step-daughter by Darlene and “Lynn” was his sister. Darlene possibly inspired or contributed to writing this song most likely written by Vincent “Gene” Craddock himself.

7. Crazy beat (Johnny Fallin, Andrew Jackson Rhodes aka Jack Rhodes)

8. I’m Gonna Catch me a Rat (Jessie Mae Robinson)

9. It’s Been Nice (Doc Pomus, Mort Shuman)

10. That’s the Trouble With Love (Joe M. Huling, Robert Chilton)

Gene Vincent with the Jimmy Haskell Orchestra and Chorus: Vincent Eugene Craddock as Gene Vincent-v; Graham Morrison Turnbull aka Scott Turner as Scotty Turner-g; unknown orchestra personnel; unknown chorus v. Produced by Sheridan Pearlman aka Jimmy Haskell. Capitol Tower, Hollywood, January 10, 1961.

11. Good Lovin’ (Calaban, Rorie)

12. Mister Loneliness (Bradford Boobis, Robert Stevens, Neil Nephew)

13. Teardrops (Richard Eugene Glasser aka Dick Glasser aka Dick Lory)

14. If You Want my Lovin’ (John S. Marascalso aka John Marascalco, Graham Morrison Turnbull aka Scott Turner aka Scotty Turner)

Same as CD 3, track 7. January 11, 1961.

15. I’m Goin’ Home (To See my Baby) (Bob Bain)

16. Love of a Man (Ed Newman)

Gene Vincent with Sounds Incorporated: Vincent Eugene Craddock as Gene Vincent-v; John St. John aka John Gillard-lg; Griff (Major) West aka Dave Glyde-ts; Bobby Cameron aka Baz Elmes-keyboards, bs; Alan Holmes-sax; Wes Hunter aka Dick Thomas-b; Tony

Newman-d. Produced by Norrie Paramor. Abbey Road Studios, London, July 27, 1961.

17. Spaceship to Mars (Norrie Parmor, Milton Subotsky)

18. THere I Go Again (John St. John aka John Gillard)

Same as CD 3, track 15. London, July 27, 1961.

19. Baby Don’t Believe Him (Clyde Pitts)

20. Lucky Star (Dave Burgess)

Gene Vincent with the Dave Burgess Band: Vincent Eugene Craddock as Gene Vincent-v; unknown g, b, d, chorus. Produced by Nick Venet. Capitol Tower, Hollywood, October 18, 1961.

21. The King of Fools (Bob Barratt)

22. You’re Still in my Heart (Bob Barratt)

23. Held for Questioning (Charles Blackwell)

24. Be-Bop-a-Lula (Vincent Eugene Craddock aka Gene Vincent, William Douchette aka Bill Beauregard Davis aka Sheriff Tex)

Gene Vincent with the Charles Blackwell Orchestra and Chorus: Vincent Eugene Craddock as Gene Vincent-v; unknown g, b, d, chorus, orchestra. Produced by Bob Barratt, Norrie Paramor. Orchestra conducted and arranged by Norrie Paramor. Abbey Road Studios, London, July 3, 1962.

Après Be-Bop-a-Lula, qui avait fait de Gene Vincent and the Blue Caps l’une des figures telluriques du rock ‘n’ roll, la période 1958-1962 marque le choix de la diversification de Gene Vincent qui enregistre plusieurs albums remarquables et influents. Ces disques n’ont pourtant eu de réel succès qu’en Angleterre, où il fut adopté par le public, à l’égal d’Eddie Cochran (avec qui il enregistre et tourne beaucoup). Avec six titres diffusés par la BBC en prime, l’intégrale studio de la première période de Gene Vincent s’achève avec ce deuxième volume.

Patrick FRÉMEAUX

After Be-Bop-a-Lula, in which Gene Vincent and the Blue Caps sent tremors through the world of rock’n’roll, the years 1958-1962 saw Gene varying his style with several remarkable albums of great influence. They were only really successful in England, where the public adopted Gene as Eddie Cochran’s equal (he recorded and toured with him). With a bonus of six titles taken from broadcasts by the BBC, this second volume completes the studio recordings made by Gene Vincent in the first part of his career.

Patrick FRÉMEAUX

CD Gene Vincent volume 2 1958-1962 The Indispensabme, Gene Vincent © Frémeaux & Associés 2015