- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

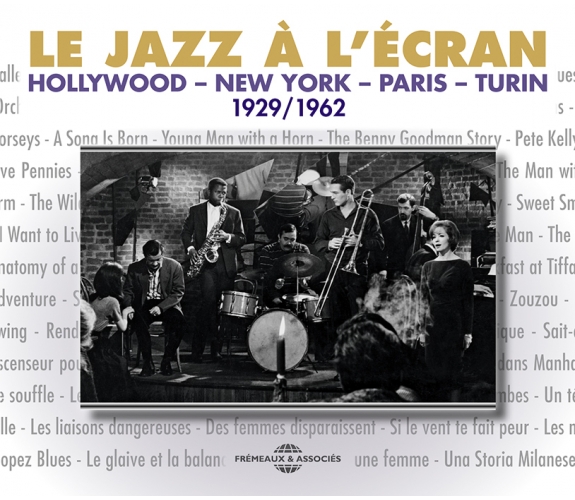

ASCENSEUR POUR L’ÉCHAFAUD, A BOUT DE SOUFFLE, UNA STORIA MILANESE,…

Ref.: FA5462

Artistic Direction : ALAIN TERCINET

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Total duration of the pack : 3 hours 39 minutes

Nbre. CD : 3

ASCENSEUR POUR L’ÉCHAFAUD, A BOUT DE SOUFFLE, UNA STORIA MILANESE,…

ASCENSEUR POUR L’ÉCHAFAUD, A BOUT DE SOUFFLE, UNA STORIA MILANESE,…

“Using jazz as background music is very difficult, because an improvisation says something in the same way as an image does, so there’s a constant risk of pleonasm.”Alain CORNEAU

This 3CD box set features an analysis on the relationship between jazz and cinema. Including soundtracks by Miles Davis (« Ascenseur pour l’échafaud »), Martial Solal (« A bout de souffle »), Alain Goraguer (« j’irai cracher sur vos tombes »), Michel Legrand (« Une femme est une femme »), Barney Wilen (« Un témoin dans la ville »), John Lewis (« Una Storia Milanese »)and Shorty Rogers (« Tarzan »)!

ANTHOLOGIE DES BANDES ORIGINALES 1960-1998

FRANCE, BELGIUM, SWEDEN, GERMANY, AUSTRIA, ITALY,...

LES PREMIÈRES ANNÉES 1937-1939

FROM GLENN MILLER STORY TO THE PINK PANTHER...

PREMIER CHAPITRE 1954-1961 (UN TEMOIN DANS LA...

PARIS - BERLIN - HOLLYWOOD 1929-1939

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Blue Blowers BluesCurtis Mosby And His Dixieland Blue Blow00:03:151928

-

2Happy FeetPaul Whiteman And His OrchestraM. Agen00:03:011929

-

3Memphis BluesMae West with Duke Ellington and His OrchestraW.C. Handy00:01:371934

-

4I've Got A Heartful Of MusicBenny Goodman00:02:131937

-

5Jeepers CreepersLouis Armstrong00:02:101938

-

6HellzapoppinSam Gaillard, Slam Stewart, Rex Stewart00:04:571941

-

7Blues in The NightJimmie Lunceford And His Orchestra00:01:511941

-

8Boom ShotGlenn Miller And His Orchestra00:02:351941

-

9Ain't is The TruthLena Horne00:02:331942

-

10Goin' UpDuke Ellington And His Orchestra00:03:411942

-

11Ain't Misbehavin'Fats Waller00:04:001943

-

12The Jumpin' JiveCab Calloway And His Orchestra00:04:361943

-

13Hong Kong BluesHoagy Carmichael00:02:181944

-

14Farewell To StoryvilleBillie HolidayWilliams00:04:281946

-

15BluesTommy Dorsey, Jimmy Dorsey, Art Tatum00:02:511946

-

16A Song Was BornLouis Armstrong, Tommy Dorsey, Benny GoodmanD. Raye00:04:251947

-

17With A Song in My HeartHarry JamesL. Hart00:02:411949

-

18Slipped DiscBenny Goodman00:04:211955

-

19He Needs Me SugarPeggy LeeA. Hamilton00:03:311955

-

20I'm Gonna Meet My Sweetie NowPete KellyB. Davis00:02:141955

-

21Hard Hearted HannahElla FitzgeraldJ. Yellen00:03:041955

-

22The Five Pennies SaintsLouis Armstrong, Dabby KayeTraditionnel00:03:121955

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Four DeucesAlex North00:03:091950

-

2Hot BloodShorty Rogers00:03:231953

-

3Dance Of The LilliputianLeith Stevens00:03:101954

-

4AuditionElmer Bernstein00:02:471955

-

5Lost KeysBuddy Bregman00:01:551956

-

6The RaceAlexander Courage00:04:451957

-

7ReflectionHenry Mancini00:03:031957

-

8Testing The Limits Of LifeLeith Stevens00:02:391957

-

9JonalahFred Katz, Chico Hamilton00:02:151957

-

10Black NightgownJonnhy Mandel00:03:361958

-

11Britt's BluesElmer Bernstein00:02:111957

-

12Social CallJohn Lewis00:03:571957

-

13OomgawaShorty Rogers00:03:261959

-

14Blues Strutter Piano Jazz WheelsShelly Manne00:04:091960

-

15Main Title Anatomy Of A MurderDuke Ellington00:04:411959

-

16Bread And WineAndré Prévin00:04:171959

-

17Autumnal SuiteDuke Ellington00:03:141961

-

18Bert's ThemeKenyon Hopkins00:02:331961

-

19Something For CatHenry Mancini00:03:121961

-

20Dance Of The Sea MonstersBud Shank00:04:121961

-

21Satan In High HeelsMundell Low00:03:271961

-

22Theme For Sister SalvationFreddie Redd00:04:441960

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1FantastiqueRay Ventura00:02:501932

-

2C'est luiJosephine BakerR. Bernstein00:03:061934

-

3Mademoiselle swingIrène de TrébertL. Poterat00:03:121942

-

4Old schoolClaude Luter00:03:231948

-

5Trottoirs de ParisSidney Bechet00:03:071955

-

6Blues à la finClaude Luter00:04:151955

-

7The rose trucJohn Lewis00:05:471957

-

8Florence sur les Champs-ElyséesMiles Davis00:02:541957

-

9Paris BBHenri Crolla, Hubert RostaingH. Crolla00:03:531957

-

10Les tricheursStan Getz, Roy Eldridge00:03:141958

-

11Street in ManhattanChristian ChevallierC. Chevalier00:03:171958

-

12DuoMartial Solal00:02:241959

-

13DanseAndré Hodeir00:02:331959

-

14Black marchSerge Gainsbourg00:01:391959

-

15Blues de memphisAlain Goraguer00:01:581959

-

16Témoin dans la villeBarney Wilen00:03:001959

-

17No hay problemaJack Marray, Duke Jordan00:03:571959

-

18Juste pour eux seulsBenny Golson00:02:281958

-

19Char à voileMartial Solal00:01:561960

-

20Thème des mordusSacha Distel00:01:351960

-

21Blues de MadoHenri Crolla, André Hodeir00:01:451960

-

22TumbleweedHenri Crolla, André Hodeir00:02:181960

-

23Le glaive et la balanceLouiguy00:02:261961

-

24Blues chez le bougnatMichel Legrand00:02:121961

-

25Monday in MilanJohn Lewis00:06:311961

Le Jazz à l'écran FA5462

LE JAZZ À L’ÉCRANHollywood – New York – Paris – Turin

1929/1962

LE JAZZ À L’ÉCRAN

Hollywood – New York – Paris – Turin 1929/1962

« Dès l’après-guerre 1914-18, les États-Unis s’installaient au premier rang des pays producteurs de films. Le cinéma et le jazz se trouvant ainsi contemporains et les circonstances de leurs développement réciproques les faisant parfois voisiner, on pouvait penser qu’ils allaient très tôt se rencontrer (1). » Effectivement. Le fameux Original Dixieland Jazzband fut filmé en 1917 au Reisenweber’s de New York dans un court-métrage, hélas perdu, « The Good-for-Nothing ». Faut-il rappeler qu’à quinze ans, Thomas « Fats » Waller accompagnait au piano les films du Lincoln Theatre ? Et qu’en 1923, Eubie Blake apparaissait dans trois court-métrages – deux en compagnie de Noble Sissle – réalisés selon le procédé Phonofilm de Lee DeForest ? Et cela avant l’apparition sur les écrans américains le 6 octobre 1927 du premier film parlant, « The Jazz Singer » qui, d’ailleurs, ne traitait en rien du sujet qu’il annonçait.

Une liaison – tumultueuse parfois - entre jazz et cinéma se nouera alors et ne cessera d’évoluer. En rassembler chronologiquement quelques témoignages qui soient significatifs revient à refuser d’établir toute hiérarchie entre leurs responsables. On croisera quelques authentiques « grands » du cinéma, un certain nombre d’artisans méritants, une poignée de tâcherons et d’autres dont il n’est pas interdit de penser qu’ils s’étaient trompé de profession.

LE JAZZ EN ATTRACTION

Furent projetés dans les salles obscures en 1929 « Thunderbolt » de Josef von Sternberg et « Hallelujah » de King Vidor qui donnaient à voir et entendre un orchestre afro-américain dirigé par Curtis Mosby. Dans le premier film, il officiait dans le cabaret « The Black Cat » et accompagnait Theresa Harris sur Daddy, Won’t You Please Come Home. Soutenue pratiquement par les mêmes musiciens, Nina Mae McKinney interprétait Swanee Shuffle dans « Hallelujah » et, hors écran, la formation jouait Blue Blowers Blues (2).

Au mois de novembre de la même année, fut donné le premier tour de manivelle de « The King of Jazz ». Une production dont l’intitulé faisait écho à la distinction décernée à Paul Whiteman par un public avide de symboles. Tourné en technicolor dans de somptueux décors kitchissimes, « The King of Jazz » qui se targuait de représenter « The Dawn of a New Day in Talking Pictures », enchaînait une suite de numéros musicaux. Rhapsody in Blue, It Happened in Monterey et quelques chansons assez anodines leur servaient de prétextes. Au long de Happy Feet, la séquence la plus délibérément « jazz », défilaient un débutant nommé Bing Crosby, les Sisters « G », un danseur contorsionniste, Rubber Legs Al Norman, et un bataillon de girls dont les claquements de talons couvraient presque la musique (3).

Après 1929, jazz et cinéma continuèrent à entretenir des liens. Parfois houleux. Familière de toutes les provocations – sa pièce « Sex » lui avait valu huit jours de prison - , Mae West refusa tout net que, pour l’accompagner dans « Belle of the Nineties », la Paramount ait recours à son orchestre de studio attitré. Duke Ellington et ses musiciens étant disponibles, ce serait eux ou personne. Ayant pratiquement sauvé la firme de la faillite grâce à ses deux derniers films, elle eut finalement gain de cause. Pour la plus grande joie du metteur en scène Leo McCarey : « Comme je suis (moi aussi) de cœur un musicien, la chose qui m’a le plus ému fut ma collaboration avec Duke Ellington. Je l’ai gardé deux semaines de plus que le temps prévu, et, un jour, le grand patron du studio vint voir ce qui se passait sur le plateau : j’étais en train de jouer du piano, et tout l’orchestre m’accompagnait, dirigé par Ellington… » (4). Leo Mc Carey ne se fera pas prier pour rendre bien visible à l’écran au long de Memphis Blues, un orchestre afro-américain donnant la réplique à une chanteuse outrageusement blond platine. À l’issue du tournage, le Duke désigna Mae West comme son actrice favorite.

Pour Hollywood, le jazz tenait de l’attraction pittoresque, genre dont il ne fallait pas abuser. La « Swing Craze » allait changer la donne. Comment songer à faire l’impasse sur ce qui envahissait les ondes, remplissait les dancings et produisait une multitude de disques qui s’arrachaient ? Benny Goodman avait involontairement déclenché ce raz de marée lors de son passage en 1935 au Palomar Ballroom de Los Angeles. C’est donc à lui que l’on fera appel. Dans la séquence d’ouverture d’« Hollywood Hotel », ses musiciens, chacun debout sur la banquette d’un cabriolet, défilaient en interprétant Hooray for Hollywood. Viendra plus tard s’insérer, sans grande logique, une version incandescente de Sing, Sing, Sing suivi de I’ve Got a Heartful of Music servi en quartette.

Souvent gratuites, ces interventions d’un musicien connu ou d’un orchestre à la mode assureront involontairement la survie de films promis sans elles aux oubliettes. Qui se soucierait encore de « Goin’ Places » et de son cheval mélomane Jeepers Creepers, si l’entraîneur n’avait été Louis Armstrong ? Musicien et chanteur de génie, Satchmo, acteur-né, sera le jazzman le plus sollicité par Hollywood. En partie pour des raisons extra-musicales tenant à sa facilité pour sublimer les stéréotypes raciaux. Sans en être dupe.

Dans ce chef-d’œuvre de l’absurde qu’est « Helzapoppin’», qui s’étonnerait de voir deux livreurs, en l’occurrence Slim Gaillard et Slam Stewart, céder aux joies de l’improvisation en compagnie d’un cuisinier nommé Rex Stewart ? Avant que gâte-sauces et soubrettes ne se livrent à une exhibition de jitterbug digne du Savoy Ballroom.

Par contre, pour Michael Curtiz et Howard Hawks, un intermède musical pouvait avoir une influence sur l’intrigue ou posséder un lien avec son déroulement. Dans « Casablanca », Sam/Dooley Wilson interprète As Time Goes By à la demande d’Ilsa Lund/Ingrid Bergman et l’histoire bascule. Au long de « To Have and Have Not », Hoagy Carmichael, jouant du piano un cure-dent à la bouche, chante Hong Kong Blues et How Little We Know. Des commentaires à ce qui se tramait au café « La Perle de San Francisco ».

Et si, tout compte fait, l’univers du jazz pouvait donner matière à une histoire romanesque ? En édulcorant quelque peu la réalité. Les apprentissages d’une nouvelle formation, les mésaventures de ses membres confrontés à la pègre et à la tentation du commercialisme serviront de ressorts dramatiques à Blues in the Night qui devra son titre à la présence de la composition éponyme interprétée par Jimmie Lunceford.

Évoquant les difficultés rencontrées dans un orchestre en raison des jalousies, antipathies et intrigues sentimentales vécues par ses membres et leurs compagnes, « Orchestra Wives » était beaucoup moins anodin qu’aurait pu le laisser supposer la présence de Glenn Miller en tête d’affiche. En dehors du célèbre I’ve Got a Gal in Kalamazoo, la bande-son comprenait un bel arrangement de George Williams sur Boom Shot.

En 1941, Orson Welles envisagea de tourner « The Story of Jazz » qui figurerait dans son documentaire-fleuve « It’s All True » ou serait présenté à part en tant que « Saga of Jazz ». Enthousiasmé par « Jump for Joy », il avait demandé à Duke Ellington d’en composer la musique. Le projet tomba à l’eau mais le script refit surface cinq ans plus tard. Ajoutée à sa trame historique, une intrigue sentimentale et musicale assez inepte donna naissance à « New Orleans ». Points positifs, la présence sur l’écran, parmi d’autres, de Louis Armstrong, Billie Holiday, Bunk Johnson, Barney Bigard, Meade Lux Lewis ainsi que le portrait de relations interraciales amicales, ce qui défiait les codes de l’époque. Rien d’étonnant à cela, le scénariste et co-producteur du film n’étant autre qu’Herbert J. Biberman qui figura bientôt parmi les « Dix d’Hollywood » blacklistés par la Commission des Activités Anti-américaines dirigée par McCarthy. Néanmoins le résultat se situait bien loin de ce qu’avait envisagé Orson Welles (5).

Autre metteur en scène trahi, Howard Hawks. Une « expérience absolument horrible », ainsi qualifia-t-il « A Song is Born » qui réutilisait le script de son « Balls of Fire » en remplaçant les aléas liés de la composition d’un dictionnaire par ceux venus de la rédaction d’une encyclopédie musicale. Seule consolation pour le réalisateur de « Rio Bravo », une jam session grandiose menée par Louis Armstrong et Lionel Hampton.

Vouloir utiliser le jazz comme prétexte à films débouchait immanquablement sur une palanquée de biographies. L’annonce de la mise en chantier d’un film consacré aux frères Dorsey laissa Eddie Condon sceptique : « Bien sûr, ils vont confier le rôle de Jimmy à Tommy et celui de Tommy à Jimmy. » Les entorses à la vérité n’allèrent pas jusque-là. Au cours d’une séquence de « The Fabulous Dorseys », Art Tatum rejoignait les deux frères et quelques gloires de la « swing era » pour faire le bœuf. L’une de ses très rares apparitions à l’écran.

Furent mises en chantier quelques hagiographies dédiées à Glenn Miller - superbement interprété par James Stewart - , Gene Krupa, Benny Goodman (il considéra le film comme une imbécillité), Red Nichols et W. C. Handy, le père du blues. Pour une fois qu’Hollywood rendait hommage à un musicien afro-américain, il accumula la même quantité de clichés, approximations et erreurs que dans les autres biopics. Toutefois, à l’écoute de Slipped Disc interprété par l’octette de Benny Goodman ou des échanges vocaux parfaitement délirants conduits par Armstrong et Danny Kaye dans The Five Pennies Saints, on ne peut qu’éprouver une certaine indulgence pour un genre pouvant offrir de tels instants.

Basé sur le roman de Dorothy Baker inspiré par la personnalité de Bix Beiderbecke, « Young Man with a Horn » tranche au milieu de ces visions idéalisées. Une intrigue amoureuse improbable et le choix d’Harry James pour évoquer Bix donnent évidemment prise à la critique. Pour ne rien dire d’une happy end aussi factice qu’invraisemblable. Il n’empêche. Pour la première fois, un musicien de jazz était montré dans toutes ses contradictions. Qu’importe si, par facilité, sa quête de l’impossible a été symbolisée par la note ratée en fin de With a Song in my Heart, le personnage incarné par Kirk Douglas possédait une véritable densité humaine (6). Qualité tout aussi présente chez les protagonistes de « Pete Kelly’s Blues » - dans le rôle du clarinettiste Al Gannaway, Lee Marvin donnait une vraie présence à un rôle secondaire. L’intri-gue, située à Kansas City en 1927, mettait en lumière les problèmes rencontrés par les jazzmen d’un speakeasy aux prises avec un racketteur sans scrupules. Stylistiquement fidèle, la bande-son donnait à entendre une petite formation « dixieland », Peggy Lee, remarquable en chanteuse déboussolée, et Ella Fitzgerald qui incarnait pour l’occasion la tenancière d’un bouge/distillerie clandestine.

Leur distribution étant entièrement afro-américaine, deux films ne bénéficient guère d’indulgence de la part de ceux qui jugent le passé à l’aune du présent. «Cabin in the Sky» et « Stormy Weather » ne manquent pas de moments musicaux forts, tels Lena Horne chantant Ain’t is The Truth, Goin’ Up exécuté par Duke Ellington, Fats Waller et son irrésistible version d’Ain’t Misbehavin’ ou Cab Calloway dans The Jumpin’ Jive. Et au long de « Stormy Weather », dans un rôle calqué sur sa personnalité, Bill « Bojangles » Robinson faisait mieux que tirer son épingle du jeu. Comme Lena Horne.

Certaines séquences de ces films n’étaient pas sans évoquer les innombrables courts-métrages célébrant les mérites d’un orchestre ou d’un soliste. Précieux pour l’histoire du jazz, ils se situent en marge de la production cinémato-graphique courante, donc hors-sujet. Même si, parmi eux, se trouve un chef-d’œuvre, « Jammin’ the Blues ».

LE JAZZ EN ACTION

Jusqu’au début des années 1950, le jazz n’était guère passé derrière l’image. Certes, les studios hollywoodiens employaient bien à l’occasion quelques rares jazzmen mais accéder à ces lieux privilégiés n’était pas à la portée du premier venu. La dissolution de l’orchestre Stan Kenton en Californie changea bien des choses. Installés à Los Angeles, ses anciens membres possédaient une technique instrumentale irréprochable, tout en montrant une appétance marquée pour l’écriture. Leur musique intéressa certains compositeurs, d’autant plus que, dans sa partition fameuse de « A Streetcar named Desire », Alex North avait commencé à introduire des séquences « jazz » (Four Deuces). D’aucuns décidèrent de lui emboîter le pas.

Trompettiste, compositeur, arrangeur, Shorty Rogers fut contacté sur son lieu de travail, le Lighthouse, par Leith Stevens qui lui proposa de travailler aux orchestrations de « The Glass Wall ». L’occasion rêvée pour mettre un pied dans les studios (7). Toujours grâce à Leith Stevens - à la suggestion dit-on de Marlon Brando -, Shorty se vit ensuite offrir l’opportunité d’arranger et de diriger quatre morceaux pour « The Wild One ». Parfaitement en situation, d’une belle violence (Hot Blood), ils étaient diffusés par le juke-box du café envahi par les motards. L’efficacité de son travail ne fut jamais contestée alors même que le film suscitait un beau scandale.

De son côté, Shelly Manne, partenaire et ami de Shorty, mit fin à certains préjugés hollywoodiens concernant les batteurs de jazz. «La première fois que l’on m’a convoqué pour un job de studio, j’ai rempli mon contrat alors que c’était très difficile. Comme c’était pour une musique proche du jazz, ils avaient fait appel à un jazzman. Il s’agissait de jouer en lecture à vue la partition de Leonard Bernstein, Fancy Free, écrite en 5/4, ce qui était inhabituel à l’époque. Je l’ai fait et, depuis, j’ai été convoqué pour jouer toutes sortes de musique. Ils avaient compris que je pouvais tout jouer et, du coup, ils ont engagé de plus en plus de jazzmen (8)»

À propos de la bande sonore de « The Man with the Golden Arm » dont il avait la charge, Elmer Bernstein déclara : « Je veux rendre crédit à Shorty et à Shelly pour leurs contributions. Non seulement je les ai pris comme consultants mais je leur ai laissé la bride sur le cou à de nombreux endroits pour qu’ils puissent y insérer ce qui correspondait à leurs idées (9). » Cette histoire de joueur drogué échouant dans sa tentative de devenir musicien professionnel - moment dépeint par Audition - entraîna une levée de boucliers. On put lire cependant dans The Hollywood Reporter : « Il faut bien mettre en valeur la contribution historique au développement de la musique de film apportée par la partition d’Elmer Bernstein. Jusqu’alors, le jazz avait été utilisé comme attraction ou afin de souligner une séquence précise. Il restait, de la part de Bernstein, à prouver qu’il pouvait être utilisé en tant que soutien continu de l’intrigue, en reflétant les diverses ambiances du film tout entier. »

Elmer Bernstein continuera dans la même voie pour « Sweet Smell of Success » en faisant appel à Fred Katz et Chico Hamilton dont le quintette interprète ici Jonalah. Plus tard, dans « Kings Go Forth », il laissera s’exprimer à deux reprises un sextette dirigé par Red Norvo, le trompettiste Pete Candoli doublant Tony Curtis dans Britt’s Blues. Et à l’occasion de « The Rat Race », il donnera la parole à Gerry Mulligan et Paul Horn.

Lorsqu’il contacta Shorty Rogers, Leith Stevens travaillait à Hollywood depuis 1939. C’était donc en toute connaissance de cause que, pour renouveler la musique de film, il avait choisi une voie novatrice qu’il utilisera à plusieurs reprises. Ayant montré que jazz et violence s’entendaient à merveille sur les écrans, dans « Private Hell 36 » qui relevait du film criminel, Leith Stevens travailla sa partition dans un esprit proche de celui prévalant dans « The Wild One ». À propos de sa musique pour « The James Dean Story », l’auteur des notes de pochette parlait de la façon unique - aussi inhabituelle qu’efficace - dont il avait su user de l’idiome du jazz. Une pièce comme Testing the Limits of Life illustrant ce que Dean avait pensé et vécu durant ses derniers mois, sortait de l’ordinaire. Paradoxalement, Leith Stevens sera sélectionné aux Academy Awards pour sa contribution à… « The Five Pennies ».

« The Wild Party » ne fut mentionné que du bout de la plume par des critiques révulsés par la brutalité d’un scénario signé John McPartland (on en a vu d’autres depuis). Pourtant, une fort belle partition de l’arrangeur Buddy Bregman soulignait les méfaits de Tom Kupfen/Anthony Quinn. Et Pete Jolly doublait Kicks/Nehemiah Persoff qui, au cours d’une séquence, accompagnait Buddy de Franco.

Lorsque lui fut confié « Hot Rod Rumble » se déroulant dans le milieu des courses de voitures trafiquées, Alexandre Courage décida d’imiter la démarche suivie par Leith Stevens vis-à-vis de ses motards. Avec une belle audace car, après un exposé plus ou moins descriptif, The Race laissait successivement le champ libre à Bob Cooper, Barney Kessel, Bud Shank, Claude Williamson, Herb Geller, Frank Rosolino et Maynard Ferguson.

Ancien pianiste et arrangeur de l’orchestre Glenn Miller (version Tex Beneke), Henry Mancini réunit aussi une équipe de « West Coasters » pour « Touch of Evil ». Il lui confia une partition très écrite, souvent proche par le style de celles qui avaient constitué leur quotidien chez Kenton, le très « bluesy » ; Reflections faisant quelque peu exception. Par la suite, Mancini signa quantité de bandes sonores pour lesquelles, quel qu’en soit leur style, il recourait à ses jazzmen de prédilection, leur offrant souvent une « séquence jazz ». À l’image de Something for Cat extrait de « Breakfast at Tiffany » dont le thème principal, Moon River, deviendra un standard interprété par une multitude de solistes et de formations (10).

Franz Waxman (« Crime in the Streets »), Pete Rugolo (« Jack the Ripper »), Dean Elliott («College Confidential»), Neal Hefti (« Synanon »), Stu Phillips (« Hell to Eternity») comptèrent également parmi ceux qui, au fil des ans, firent appel aux jazzmen de la Côte Ouest pour l’exécution de leurs partitions, souvent destinées à des film de série B.

Johnny Mandel qui avait écrit pour le compte de Woody Herman, Count Basie, Stan Getz et Chet Baker, réussit un coup de maître pour son premier travail au cinéma. Nommée aux Grammy Awards, sa partition de « I Want to Live » fut la première, aux USA, à relever intégralement du jazz. Joué par une petite formation dirigée par Gerry Mulligan, Black Nightgown, comme quelques autres thèmes, devait être inséré dans la bande sonore lorsque une source extérieure justifiait sa diffusion ; un poste de radio par exemple.

Partagé entre musique de film traditionnelle à laquelle il faisait honneur et jazz, André Previn pencha nettement en faveur du second pour l’adaptation à l’écran du roman de Jack Kerouac « The Subterraneans ». Malgré une pièce comme Bread and Wine, sa partition en laissa plus d’un sur sa faim. Quelques décennies plus tard, la publication d’un CD contenant les morceaux rejetés par la production lui rendit enfin justice.

En 1959, le Duke se vit confier la composition de la bande sonore d’un film d’ Otto Preminger, « Anatomy of a Murder ». « Je me suis employé à composer une musique d’accompagnement qui colle le mieux possible à l’image. Et cela, je pense que c’est important ! (11) » De cette œuvre couronnée « Best Motion Picture Soundtrack of the Year » aux Grammy Awards, Alain Corneau dira qu’« avec une partition très écrite, étonnamment bluesy, Duke Ellington se situe sur le même plan et atteint à une identique réussite que Bernard Hermann vis-à-vis d’Hitchcock (12). »

Ellington reçut une nouvelle commande concernant un film signé Martin Ritt, « Paris Blues ». Habilement adapté d’un roman assez médiocre de Harold Flanders, il avait pour sujet la vie de deux jazzmen américains dans la capitale où le film serait tourné. Le Duke procéda en trois étapes. La première consistant en la réalisation de pré-enregistrements sur lesquels répéteraient Sidney Poitier et Paul Newman, parfaitement convaincants dans leurs rôles. S’en suivit une mise au point à Paris, comprenant prioritairement l’intégration de Satchmo : « Une des choses que je connaissais à l’avance était que Louis occuperait une place prépondérante et donc qu’il fallait que j’écrive de façon à ce que Louis sonne comme Louis (13). » Troisième acte, l’enregistrement à New York d’une musique d’accompagnement au sens premier du terme. En fait partie Automnal Suite qui accompagnait une promenade sur des quais de la Seine aussi dépourvus de voie sur berge que de Paris-Plage.

Après n’avoir été qu’exécutants, certains musiciens de la West Coast virent enfin leur nom figurer au bas de l’affiche. Quelquefois de façon inattendue. Shorty Rogers : « Au premier chef j’ai ressenti une certaine appréhension lorsque la MGM m’a contacté pour écrire la musique d’un film de Tarzan. J’ai vite réalisé que je n’avais pas besoin de m’en faire : ils m’ont seulement demandé de faire quelque chose d’excitant avec plein de percussions et m’ont laissé me débrouiller avec ça (14). » Une liberté bien venue : Oomgawa compte parmi les pièces « exotiques » les plus réussies de Shorty.

Shelly Manne : « En Europe, en France spécialement, d’excellentes bandes sonores ont été réalisées par Miles Davis, Herbie Hancock. Elles étaient parfaites car elles respectaient l’esprit du film sans s’interposer et tout en restant de l’excellent jazz. C’est ce que j’ai essayé de faire pour « The Proper Time » (15). » Après l’avoir vu et revu, Joe Gordon, Richie Kamuca, Vic Feldman, Russ Freeman, Monty Budwig et Shelly lui-même improvisèrent comme Miles Davis et ses partenaires l’avaient fait à l’occasion d’«Ascenseur pour l’échafaud». Pour des raisons techniques, le disque publié – remarquable - fut le fruit d’un « remake » en studio. Qu’en était-il à l’écran ? Mystère. Jamais distribué ici le film de Tom Laughlin ne fait l’objet d’aucune édition en DVD… Tout comme les deux productions de Bruce Brown « Slippery When Wet » et « Barefoot Adventure ». Deux films consacrés au surf pour lesquels Bud Shank composa et enregistra un accompagnement assez inattendu dans un tel contexte. Venu de « Barefoot Adventure », Dance of the Sea Monsters est interprété par un sextette dans lequel la guitare remplace le piano.

Même si Hollywood restait maître-d’œuvre, New York eut vite son mot à dire. John Lewis : « Odds Against Tomorrow » fut pour moi une expérience différente [de « Sait-on jamais ? »], car j’ai dû composer une musique étroitement liée à l’histoire de ce film, une musique vraiment conçue pour coller au film (15). » De ce fait, en extraire un morceau sans le priver de toute signification s’avère délicat. United Artists en prit conscience car, simultanément à la publication de la musique originale, fut édité un second album dans lequel le Modern Jazz Quartet reprenait les principaux thèmes. Il n’empêche. Jean-Pierre Melville désigna cette bande sonore comme la meilleure qui ait jamais été conçue.

« The Hustler » de Robert Rossen figure maintenant parmi les classiques du 7ème Art. Vingt-cinq ans plus tard, Martin Scorsese lui donna une suite avec « The Color of Money » pour laquelle Gil Evans travailla. Curieusement, la partition d’origine signée par Kenyon Hopkins, un solide professionnel dont le palmarès comprenait déjà « Baby Doll » et « Twelve Angry Men », reste méconnue. Pourtant, il avait réuni pour l’occasion une équipe de musiciens new-yorkais de premier plan dont Phil Woods et Hank Jones. Ce que fera également le guitariste Mundell Lowe pour « Satan in High Heels ». Un film à très petit budget, légèrement scandaleux à l’époque, qui survivra plus par sa musique que par les charmes généreusement dévoilés de ses interprètes.

« The Connection » appartient à ce cinéma américain indépendant, faisant fi des tabous, qui n’hésitait pas à s’assurer l’appui du jazz le moins consensuel qui soit. Tout auréolé d’une participation musicale de Charles Mingus, « Shadows » l’avait précédé. En fait, dans sa seule version visible – la seconde –, le film de Cassavetes ne donne à entendre que quelques courtes phrases de contrebasse solo et un exposé embryonnaire de Nostalgia in Times Square ponctuant la bagarre dans l’arrière-cour du café. Le reste de la bande-son est assuré par Shafi Hadi au saxophone, jouant a cappella derrière d’abondants dialogues…

Pour « The Connection », Shirley Clarke eut recours tant à la musique de Freddie Redd qu’aux jazzmen qui, chaque soir, improvisaient sur scène lorsque la pièce éponyme avait été représentée au Living Theatre. Illustrant la confrontation entre une salutiste et les drogués attendant leur fournisseur, Theme for Sister Salvation connut une belle carrière.

Sous l’égide de l’Association Française de la Critique de Cinéma, « The Connection » fut présenté hors-sélection au Festival de Cannes 1961. L’année où, dans le jury officiel, figurait Edouard Molinaro. L’un de ceux grâce auxquels, au cours des années 1950, la France concurrença Hollywood sur le plan du jazz pris comme musique de film…

LE JAZZ ET LES ÉCRANS NOIRS FRANÇAIS

Peut-on considérer que « L’amour à l’américaine », sorti en décembre 1931, contienne l’un des premiers témoignages d’une liaison hexagonale cinéma/musique syncopée ? Les opinions divergeront. Toutefois, en admirateur de Paul Whiteman, Ray Ventura y flirtait bien quelque peu avec le jazz grâce à Fantastique ! qui deviendra son indicatif (17).

La présence de musiciens ou d’orchestres afro-américains se banalisera bientôt dans les productions françaises. Freddie Johnson et ses musiciens furent aperçus jouant brièvement St Louis Blues dans « Chotard et Cie » de Jean Renoir (1933). À l’exemple des États-Unis, nombre de scènes de cabaret laissaient entrevoir - et entendre en fond de dialogues - , ceux qui faisaient alors les beaux soirs des boîtes de nuit parisiennes : Arthur Briggs and His American-Cubano Boys (« Le roman d’un tricheur », Sacha Guitry, 1936), Valaida Snow (« Pièges », Robert Siodmak, 1939), Willie Lewis and His Entertainers (« Cinderella », Pierre Caron, 1937), l’orchestre de Bobby Martin (« L’alibi », Pierre Chenal, 1936), Garland Wilson et une chanteuse interprétant Darling, je vous aime beaucoup (« Carrefour », Curtis Bernhardt, 1938) (18). Et, bien sûr, Joséphine Baker qui, au final de « Zouzou » à la suite d’une série de tableaux vivants, interprétait C’est lui entourée de boys. L’accompagnait un orchestre dirigé par Al(ain) Romans. Tout cela relevait d’un exotisme bien compris auquel, par la force des choses, l’Occupation mit fin.

Si, en réaction aux diktats des autorités, jazz et simili jazz connaissaient une belle popularité dans la capitale, le cinéma se devait d’observer une grande prudence. Une bluette comme « Mademoiselle Swing » frisa même l’interdiction. Une jeune personne masquée, glissant sur un toboggan pour arriver sur scène et chanter « Oubliez tous vos soucis, devenez swing aussi », n’avait guère sa place au sein du réarmement moral si cher à Vichy. La dite « Mademoiselle » était incarnée par la nouvelle coqueluche des zazous, Irène de Trébert. L’une des rares à pratiquer en France les claquettes.

Une fois le pays libéré, Gisèle Pascal incarna une ingénue nouvelle dans « Mademoiselle et son flirt » qui, dans une scène de cabaret, donnait à voir – paraît-il – quelques jazzmen français dont Alain et Boris Vian. De ce film signé Jean de Marguenat, il ne reste rien, semble-t-il, sinon une chanson, Un oiseau chante dans mon cœur, et une nouvelle, « Le figurant » incluse dans le recueil « Les Fourmis ». Boris Vian y racontait le tournage. À sa manière.

Amateur de jazz de longue date – depuis 1925 -, Jacques Becker avait décidé de faire du « Lorientais » le point de rencontre des jeunes de l’après-Libération dont il entendait conter les mésaventures dans « Rendez-vous de Juillet ». Le script d’origine prévoyait qu’Ole Miss interprété par le Mezzrow/Bechet Quintet accompagne le générique. Il n’en fut rien (19). S’y font cependant entendre Bernard Peiffer accompagnant la chanteuse Simone Langlois, Rex Stewart et, surtout, le maître des lieux, Claude Luter. La bande originale du film ne fut jamais éditée et de nombreux dialogues viennent parasiter les interprétations de Black Bottom Stomp et de Blues. Faire l’impasse sur « Rendez-vous de Juillet » est impensable en raison de son importance historique. Recourir à un subterfuge devient une obligation. Enregistré à leur insu quelques mois plus tôt, Old School témoigne d’une fougue et d’un enthousiasme identiques à ceux qui animaient les Lorientais devant la caméra de Becker. En sus, il s’agit d’un thème de Mezz Mezzrow dont le nom figure au générique conjointement à celui de Jean Wiener.

Saint Germain-des-Prés, ses caves et sa faune défrayaient la chronique. Les producteurs jugeront donc bien venu d’insérer une séquence germanopratine dans des films où elle n’avait rien à faire. Dans « Piédalu député » ou « C’est la vie parisienne », par exemple. La popularité de Sidney Bechet lui vaudra d’apparaître dans « Série Noire » pour lequel il composa Trottoirs de Paris que l’on entendait à deux reprises (20). Non seulement en tant que musicien mais aussi comme acteur, il participera à « L’inspecteur connaît la musique » dans lequel il succombait au cours d’une algarade avec le clarinettiste Harris Louis alias Claude Luter. À l’origine de leur différent, Blues de la fin.

Jusque-là, le « Vieux Style » remportait sur les écrans la bataille qui l’opposait aux « Modernistes ». En 1957, la victoire allait changer de camp grâce à Roger Vadim, Louis Malle et, dans un moindre mesure, Michel Boisrond. Destinée à mettre en valeur Brigitte Bardot, « Une Parisienne » habituera les spectateurs à des sonorités inhabituelles dans le cadre d’une comédie « grand public ». La partition d’Henri Crolla et Hubert Rostaing n’hésitait pas à flirter épisodiquement avec le jazz moderne. Chanté par Christiane Legrand, Paris B. B. évoquait le fameux Hey, Bellboy gravé trois ans plus tôt en Californie par Gloria Wood, assistée de Pete Candoli (21).

À la vérité « Sait-on jamais ? » fut le premier film au monde à présenter une bande sonore exclusivement « jazz ». Ray Ventura étant co-producteur du film, son neveu Sacha Distel suggéra à Roger Vadim de prendre comme compositeur John Lewis. Connaissant et aimant Venise où se déroulait l’intrigue, il saurait mieux que personne écrire une musique en accord avec un tel cadre. The Rose Truc accompagne l’un des rares moments inoubliables du film : Sforzi/Robert Hossein, tout de noir vêtu une rose rouge à la main, aborde Sophie/Françoise Arnoul dans une rue déserte de la Giudecca. Une séquence muette qui laisse toute la place à la musique de John Lewis (22).

Vis-à-vis d’« Ascenseur pour l’échafaud », Miles Davis sembla se comporter de manière désinvolte. Pierre Michelot : « À l’exception d’un morceau (Sur l’autoroute) basé sur les harmonies de Sweet Georgia Brown, nous n’eûmes de la part de Miles Davis que des indications succinctes. En fait, il nous a simplement demandé de jouer deux accords – ré mineur et do7 -, quatre mesures de chaque ad libitum. Cela aussi était nouveau, les morceaux n’étaient pas mesurés en durée. Il y avait des semblants de structures, mais elles étaient un peu éclatées par rapport à ce que l’on jouait habituellement. » Miles savait ce qu’il faisait : le pouvoir de fascination de Florence sur les Champs-Elysées lié à la déambulation nocturne de Jeanne Moreau, reste intact après plus d’un demi-siècle…

Pour illustrer musicalement son nouveau film, « Les liaisons dangereuses », Vadim demanda son avis à Marcel Romano. Alors programmateur du Club St Germain, ce dernier était une figure incontournable lorsqu’il s’agissait de marier cinéma et jazz. Thelonious Monk devait venir à Paris, il conviendrait donc à merveille. Sa tournée ayant été annulée, l’enregistrement dût s’effectuer à New York. À la demande de son chef, Barney Wilen se joignit au quartette de Monk qui l’avait entendu la veille, au sein des Jazz Messengers, pendant qu’ils gravaient une autre partie de la bande sonore. Signée Jack Marray alias Duke Jordan, elle seule sera éditée - No Hay Problema en fait partie. De Monk, il reste de nombreux extraits identifiables au fil des images. À l’exception du spiritual Bye and Bye servi à trois reprises, aucune composition originale n’est décelable, seulement des fragments de Rhythm-a-ning, Bolivar Blues, Well You Needn’t réinterprétés.

La même année, toujours à l’instigation de Marcel Romano, Edouard Molinaro confia la musique d’« Un témoin dans la ville » à Barney Wilen qui composa et interpréta une partition parfaitement en situation. À la dernière minute, Molinaro avait également demandé à Art Blakey de fournir un accompagnement à un autre de ses films « Des Femmes disparaissent ». Habitué à ce genre de travail, Benny Golson prit les choses en main et, le temps pressant, adapta certaines compositions du répertoire des Messengers – Juste pour eux seuls est en fait Just by Myself. Leur son « Hard Bop » pur et dur convenait à une production dont la brutalité de certaines séquences avait choqué, à l’époque, les chroniqueurs (23).

Si Vadim, Louis Malle ou Edouard Molinaro possédaient une vague idée de ce qui les attendait en se tournant vers des jazzmen, Jean-Luc Godard n’en avait pas la moindre. Jean-Pierre Melville lui avait recommandé Martial Solal auquel il avait eu recours ponctuellement pour « Deux hommes dans Manhattan » lorsque Christian Chevallier, compositeur en titre de son film s’était révélé indisponible. Le metteur en scène avait été séduit par ce qu’il avait imaginé pour accompagner la poursuite du photographe Delmas par Moreau.

De sa partition pour « À bout de souffle » Solal dira : «… elle est faite de trois notes : c’est surtout un travail d’ambiance et d’orchestration (24). » Sans doute, mais au travers de Duo comme de Char à voile, écrit pour « Si le vent te fait peur », il se révélait comme l’un des compositeurs les plus efficaces et les plus personnels qui soit dans l’univers cinématographique. À l’instar d’André Hodeir qui, pour les « Les tripes au soleil », déclarait « avoir conçu sa partition un peu comme un commentaire d’opéra ».

Qu’avait eu à l’esprit Alain Goraguer, confronté à l’adaptation calamiteuse du « J’irai cracher sur vos tombes » de son ami Boris Vian ? Ce dernier l’avait reniée mais s’était rendu à la projection qui lui sera fatale, sensible à l’argument de Jacques Dopagne : « Et puis, Goraguer, sa musique est magnifique. Toi-même, Boris, tu l’as dit souvent : même si le film est une merde, il y aura quand même la musique ». L’auteur de « L’écume des jours » n’eut pas le temps d’entendre ce Blues de Memphis qui, mieux que les images, évoquait le Sud profond.

Les représentants de la « Nouvelle Vague » cinématographique n’avaient pas l’exclusivité de l’annexion du jazz à leurs productions. En 1947, Marcel Carné avait contacté Django Reinhardt pour illustrer « La fleur de l’âge », un film qui restera inachevé. À l’occasion des « Tricheurs », portrait d’une certaine jeunesse, il savait quelle musique était indispensable. Le fait qu’aient été négociés les droits d’enregistrements du commerce ne le satisfaisait pas vraiment. Le JATP donnant deux concerts Salle Pleyel, Carné fit appel à la troupe de Norman Granz qui enregistra pour lui quelques quarante minutes de musique. Être utilisée en fond sonore durant les surprise-parties du film ne lui rendit pas vraiment justice. L’édition d’un 45 t donna accès à l’intégralité de pièces comme Les Tricheurs interprété par Roy Eldridge, Stan Getz et le trio d’Oscar Peterson.

Les modes passent. Au cinéma plus qu’ailleurs. Au début des années 1960, le jazz ne s’imposera plus qu’à la sauvette. Dans « St Tropez Blues », sur Tumbleweed, André Hodeir renouait avec une écriture dont la singularité s’était révélée à l’occasion des « Tripes au soleil ». À la façon dont Serge Gainsbourg et Alain Goraguer avaient réussi à glisser Black March dans « L’eau à la bouche », un nouveau venu, Michel Legrand, inséra son Blues chez le bougnat dans « Une femme est une femme » signé Jean-Luc Godard. L’ouverture de « Le glaive et la balance » donnait à entendre Kenny Clarke et Lou Bennett sans que rien ensuite dans la musique de Louiguy n’y fasse écho. Probablement parce qu’il y tenait le rôle principal, Sacha Distel réussit dans « Les mordus » à faire la part belle au jazz.

John Lewis, lui, eut semble-t-il les coudées franches pour la co-production franco-italienne « Una Storia Milanese ». Monday in Milan donne à entendre un quartette de jazz comprenant Bobby Jaspar et René Thomas confronté à une contrebasse « classique » et à un quatuor à cordes. Passionnant. Hélas, ce fut pratiquement le dernier travail de John Lewis pour le cinéma…

L’histoire des rapports entre jazz et films ne se termine pas là bien sûr. Elle se prolongea, tant outre-Atlantique qu’en Europe, à la fois semblable et différente, en fonction des foucades et contradictions de ses composants.

Alain Tercinet

© 2014 Frémeaux & Associés

(1) Henri Gautier « Jazz au cinéma », Premier Plan n° 11, juillet 1960, Lyon. La première étude circonstanciée consacrée au sujet en France.

(2) Curtis Mosby et ses Blue Blowers apparaissent aussi dans « Off in the Silly Night », « Music Hath Charms », « The Melancholy Dame », « Framing of the Shrew », quatre court- métrages produits par les Christie Studios, destinés essentiellement au public afro-américain. Tiré de « Hallelujah », Swanee Shuffle figure dans l’anthologie conçue par Daniel Nevers « Jazz Dance Music 1923 - 1941 », (Frémeaux FA 03).

(3) Simultanément Paul Whiteman avait enregistré Happy Feet pour Columbia, version donnant à entendre Bing Crosby, Eddie Lang, Frankie Trumbauer, Andy Secrest et Joe Venuti.

(4) « Leo et les aléas », entretien avec Leo McCarey par Serge Daney et Jean-Louis Noames, Cahiers du cinéma n° 163, février 1965.

(5) Les variations d’intensité sonore de Farewell to Storyville tiennent au fait que, dans le film, ce morceau est entendu alternativement depuis le cabaret l’Orpheum et la rue où la police évacue le Quartier Réservé. « New Orleans » contient un magnifique anachronisme car Woody Herman y figure sous son nom à la tête de son orchestre alors qu’à l’époque où se déroule le film, il avait environ dix ans…

(6) Une photo reproduite dans « Eddie Condon’s Scrapbook of Jazz » montre Kirk Douglas se familiarisant avec le maniement du cornet au « Eddie Condon’s », entouré de Sidney Bechet, Pee Wee Russell et Art Hodes.

(7) Shorty lui-même apparaîtra dans « The Glass Wall ».

(8) « Manne with the Golden Arms », interview de Claude Carrière et Alain Tercinet, Jazz Hot n° 351/352, été 1978.

(9) Livret du CD «Music from the Motion Picture composed and conducted by Elmer Bernstein - The Man with the Golden Arm» (Fresh Sound).

(10) Henry Mancini composa également la musique d’accompagnement de la série télévisée, « Peter Gunn » dans laquelle un détective privé passait ses loisirs au « Mother’s », une boîte de jazz. Il ne fut pas le seul à hanter les petits écrans sur fond de cette musique : « Richard Diamond, Private Detective » (Pete Rugolo) ; « M-Squad », « Mike Hammer », « Ironside » (Marty Paich, Quincy Jones, Benny Golson), « Johnny Staccato »… La plupart des épisodes contenaient d’excellents moments de jazz.

(11) A. H. Lawrence « Duke Ellington and His World », Routledge, New York, London, 2001.

(12) « Alain Corneau, le choix des rythmes », propos recueillis par Alain Tercinet, JazzMan n° 36, mai 1998.

(13) comme (11).

(14) Livret du CD « You Shorty, Me Tarzan » (Giant Steps Records).

(15) comme (8). Shelly Manne composa et interpréta la musique d’un western « Young Billy Young » et de « The Trial of Cattonsville Nine » relatant un procès fait à des étudiants réfractaires à la conscription en raison de leur opposition à la guerre du Vietnam.

(16) Thierry Lalo, « John Lewis », collection Mood Indigo, éditions du Limon, 1991.

(17) Deux versions en furent gravées. La première, conforme au film, comprend un vocal de Mlle Spinelly difficilement supportable. Dans la seconde, Russell Goudey la remplace avantageusement.

(18) « Pépé le Moko » (Julien Duvivier, 1936) : le nom d’Herman Chittison est mentionné dans certains ouvrages. Au mieux, il pourrait être l’un des interprètes de la musique liée au disque choisi par Pépé/Jean Gabin pour danser avec Gaby/Mireille Balin au Bar Ali-Baba. Une autre erreur voudrait que Django Reinhardt soit présent dans « Naples au baiser de feu ».

(19) Mal accueilli par la critique lorsqu’il fut présenté au Festival de Cannes en septembre 1949, « Rendez-vous de Juillet » fut entièrement remonté par Jacques Becker avant sa sortie dans les salles en Décembre. Est-ce à cette occasion qu’Ole Miss passa à la trappe?

(20) Il s’agit du film de Pierre Foucaud interprété par Eric Von Stroheim et Henri Vidal et non du « Série Noire » d’Alain Corneau.

(21) Par un juste retour des choses, ce sera la même Gloria Wood qui reprendra la partie de Christiane Legrand dans la version de Paris B.B. appartenant à l’album « Behind Bardot » que Pete Rugolo consacra en 1960 aux musiques de films français.

(22) La seule édition phonographique reproduisant la musique entendue à l’écran fut publiée à l’époque sur le label français « Versailles », propriété de Ray Ventura. Les rééditions parues sur Atlantic utilisent certaines versions alternatives.

(23) Alors que son nom est cité au générique, Kenny Clarke ne figure dans aucun crédit non plus que dans les discographies. Au catalogue de la Library of Congress on peut lire, à la suite de l’énoncé du personnel, « + the participation of Kenny Clarke, solo drums. » C’est lui que l’on entend en ouverture de Générique, introduisant un extrait du thème Des femmes disparaissent. Un montage répété à deux reprises.

(24) Yvan Amar, « Martial Solal : Cinémémoire », JazzMan n° 36, mai 1998.

NOTES DISCOGRAPHIQUES

L’état des bandes sonores de certains films empêchent souvent de les utiliser. Un pis-aller consiste à se retourner vers les enregistrements 78t des morceaux correspondants, gravés par les mêmes musiciens à la même période (Curtis Mosby, Paul Whiteman, Ray Ventura, Joséphine Baker, Irène de Trébert, Claude Luter).

À partir du moment où les bandes sonores ont été publiées commercialement, il est difficile de savoir s’il s’agit vraiment de la musique telle qu’elle est entendue dans les cinémas ou d’une re-création en studio. Ce qui est le cas pour Leith Stevens (Dance of the Lilliputian), Buddy Bregman (Lost Keys), Shelly Manne (Blue Strutter/ Piano Jazz / Wheels), Sidney Bechet (Trottoirs de Paris), Claude Luter (Blues de la fin).

JAZZ ON FILM

Hollywood – New York – Paris – Turin 1929/1962

“As soon as World War I ended in 1918, the United States installed itself as the N°1 film-producing country. With jazz and films finding themselves contemporaries, and sometimes neighbours due to circumstances in their reciprocal development, it was fair to suppose that they would meet very soon.”(1) Indeed. The famous Original Dixieland Jazzband was filmed at Reisenweber’s in New York in 1917: that short-film, “The Good-for-Nothing”, was unfortunately lost. Does anyone need reminding that Thomas “Fats” Waller was accompanying films at the Lincoln Theatre when he was fifteen? Or that in 1923, Eubie Blake appeared in three short-films — Noble Sissle was in two of them — that were made using Lee De Forest’s Phonofilm system? And it all happened before the first “talking picture” called “The Jazz Singer” appeared on American screens on October 6th 1927, a film which, incidentally, didn’t deal with the subject announced in its title.

A liaison — sometimes tumultuous — would develop between jazz and films, and the affair continues to this day. Putting a few significant elements together chronologically would be tantamount to refusing any hierarchy between those responsible; and so the scheme of things in this set combines some of the authentic “greats” in the movies, a certain number of deserving craftsmen, a handful of odd jobbers, and others whose presence here might possibly give the impression that they chose the wrong trade.

JAZZ AS AN ATTRACTION

In 1929 there were projections in darkened theatres of Josef von Sternberg’s “Thunderbolt” and King Vidor’s “Hallelujah”, where spectators could see and hear an Afro-American orchestra led by Curtis Mosby. In the former he was officiating at “The Black Cat” club, and accompanying Theresa Harris on Daddy, Won’t You Please Come Home. In “Hallelujah”, with practically the same musicians, Nina Mae McKinney sang Swanee Shuffle and, off-screen, the band played Blue Blowers Blues.(2)

In November that same year, the camera rolled for “The King of Jazz”, a production whose title echoed the honour given to Paul Whiteman by a public eager for symbols. Filmed in Technicolor in sumptuously kitsch settings, “The King of Jazz” — it boasted that it represented “The Dawn of a New Day in Talking Pictures” — strung together a succession of musical numbers, among them Rhapsody in Blue, It Happened in Monterey and a few rather trivial songs which served as a pretext. In the course of Happy Feet, the most deliberately “jazz” piece, the sights included a beginner named Bing Crosby, the “G” Sisters, the dancer/contortionist “Rubber Legs” Al Norman, and a battalion of girls whose clacking heels almost drowned out the music.(3)

After 1929, jazz and the movies continued to have ties. Some were turbulent. As someone used to all kinds of provocation — her play called “Sex” earned her a week in jail — Mae West flatly refused when Paramount wanted its own studio orchestra to accompany her in “Belle of the Nineties”: Duke Ellington and his musicians were available, and Mae told the studio it was either that or nothing. Having practically saved the company from bankruptcy thanks to her two previous films, Mae won in the end. Director Leo McCarey was delighted: “Since I’m a musician at heart (me too), the thing that moved me most was my association with Duke Ellington. I kept him two weeks longer than planned, and one day the big boss at the studio came over to see what was happening on the set: I was playing the piano, accompanied by the whole orchestra, led by Ellington…”(4) Leo McCarey didn’t need to be pleaded with to make sure he was always in the shot during Memphis Blues, featuring an Afro-American orchestra behind the outrageous platinum-blonde singer. When they’d finished shooting, Duke declared that Mae West was his favourite actress.

Jazz was seen as a picturesque attraction by Hollywood, but the genre wasn’t one to be abused. The “Swing Craze” changed all the cards. How could Hollywood ignore the way jazz was invading the air-waves, filling dancehalls and producing thousands of records that were snatched up as soon as they went on sale? Benny Goodman had involuntarily caused this tidal wave with his 1935 appearance at the Palomar Ballroom in Los Angeles, and so Hollywood called him. In the opening sequence for “Hollywood Hotel” his musicians, each one standing on the bench-seat of a convertible, parade for the camera while playing Hooray for Hollywood. A later insert in the film — there’s no apparent logic behind it — is an incandescent version of Sing, Sing, Sing followed by a quartet-version of I’ve Got a Heartful of Music.

Often gratis, these appearances by a well-known musician or fashionable orchestra accidentally ensured the survival of films that would have remained in oblivion without them. Who would still remember “Goin’ Places” and its music-loving horse Jeepers Creepers, if the trainer hadn’t been Louis Armstrong? Besides being a musician and singer of genius, Satchmo was a born actor, and he would be the one most sought-after by Hollywood, partly for reasons which had nothing to do with music at all, i.e. the facility with which he portrayed racial stereotypes. Not that he was fooled for a minute.

In the masterpiece of the absurd that is “Helzapoppin’”, who would have been amazed to see two delivery-men, namely Slim Gaillard and Slam Stewart, abandoning themselves to the joys of improvisation in the company of a cook named Rex Stewart? The maids and the kitchen-boy then went on to give a ‘jitterbug’ demonstration worthy of the Savoy Ballroom.

On the other hand, especially where Michael Curtiz and Howard Hawks were concerned, a musical interlude could have an influence on the plot, or provide a link in the way it unfolded. In “Casablanca”, Sam/Dooley Wilson plays As Time Goes By for Ilsa Lund/Ingrid Bergman, and the storyline suddenly tilts. And all the way through “To Have and Have Not”, Hoagy Carmichael, playing piano with a tooth-pick in his mouth, sings Hong Kong Blues and How Little We Know. They were comments on what was afoot at the Pearl of San Francisco Cafe.

And what if, when all is said and done, the jazz universe could lend substance to a romantic story, even if it did sweeten reality a little? The beginnings of a new band, the misadventures of its members confronted by the Mob, the temptations of commercialism… they would all serve as dramatic springboards in Blues in the Night, which would take its title from the composition played by Jimmie Lunceford.

In evoking the difficulties encountered by an orchestra due to the jealousies, hostilities and sentimental intrigues lived by its members and their companions, “Orchestra Wives” was a lot less innocuous than you might suppose on seeing the name of Glenn Miller at the top of the bill. Besides the famous I’ve Got a Gal in Kalamazoo, the soundtrack included George Williams’ beautiful arran-gement of Boom Shot.

In 1941, Orson Welles envisaged shooting “The Story of Jazz”, either to appear in his marathon-documentary “It’s all True”, or else as a stand-alone film, a “Saga of Jazz”. Filled with enthusiasm for “Jump for Joy”, Welles had asked Duke Ellington to write the music for it. The project was abandoned, but the script resurfaced five years later. Once added to the story’s historic thread, a rather inept sentimental and musical plot gave birth to “New Orleans”. There were still positive aspects: the presence on the screen of, among others, Louis Armstrong, Billie Holiday, Bunk Johnson, Barney Bigard and Meade Lux Lewis, plus the portrayal of friendly interracial relationships, which went against the codes of the period. This should come as no surprise, given that the screenwriter and co-producer of the film was none other than Herbert J. Biberman, who soon appeared on the blacklist of writers — the “Hollywood Ten” — published by McCarthy and his House Committee on Un-American Activities. But even so, the result was a long way from the one Orson Welles had in mind.(5)

Another betrayed filmmaker was Howard Hawks. “An absolutely horrible experience” was how he qualified “A Song is Born”, which re-used the script of his “Balls of Fire” by substituting the misfortunes linked to writing a dictionary with those involved in editing a musical encyclopaedia… The only consolation for the director of “Rio Bravo” was a grandiose jam-session led by Louis Armstrong and Lionel Hampton.

The desire to use jazz as a pretext for making a film inevitably led to a bunch of biopics. The announcement of work beginning on a film devoted to the Dorsey brothers left Eddie Condon sceptical: “They’re bound to give Jimmy’s role to Tommy, and Tommy’s role to Jimmy.” Hollywood’s twisting of the truth didn’t actually go that far. In one scene from “The Fabulous Dorseys”, Art Tatum joins both brothers and a few “swing era” heroes for a jam in one of his very rare screen-appearances.

A few hagiographies were also devoted to the likes of Glenn Miller — a superb performance by James Stewart —, Gene Krupa, Benny Goodman (he thought the film was trash), Red Nichols, and W. C. Handy, the father of the blues. The latter film was one of the rare instances where Hollywood would pay tribute to an Afro-American musician, but it accumulated the same quantity of clichés, approximations and errors as other biopics. On the other hand, when you listen to Slipped Disc played by Benny Goodman’s octet, or the totally crazy vocal exchanges between Armstrong and Danny Kaye in The Five Pennies Saints, you can only feel a kind of indulgence towards a genre capable of inspiring such great moments.

Based on the Dorothy Baker novel inspired by Bix Bei-derbecke, the film “Young Man with a Horn” cut right through such idealized visions. Its improbable love-story, combined with the choice of Harry James to portray Bix, couldn’t avoid giving critics something to get their teeth into, not to mention the film’s “happy ending”, which has a ring to it as false as the ending is improbable. But even so, a jazz musician was portrayed for the first time in all his contradictions. It doesn’t really matter if the hero’s quest for the impossible is symbolized — facilely — by the note he misses at the end of With a Song in my Heart, because the character portrayed by Kirk Douglas possesses a genuinely human density.(6) That quality is just as present in the protagonists of “Pete Kelly’s Blues”: in the role of clarinettist Al Gannaway, Lee Marvin makes a second role very substantial. The plot, set in Kansas City in 1927, throws light on the problems encountered by jazzmen in a speakeasy when they fall prey to an unscrupulous gangster. The soundtrack is stylistically faithful and it allows you to hear a small “Dixieland” group, Peggy Lee (remarkable in the role of a washed-up singer), and Ella Fitzgerald as the mistress-owner of a dive/clandestine liquor operation.

Two films with an entirely Afro-American cast were shown hardly any indulgence by those accustomed to judging the past by the present. “Cabin in the Sky” and “Stormy Weather” show no lack of strong musical moments: Lena Horne singing Ain’t it The Truth; Goin’ Up performed by Duke Ellington; Fats Waller and his irresistible version of Ain’t Misbehavin’; Cab Calloway’s The Jumpin’ Jive; and in “Stormy Weather”, playing a role tailored to his own personality, Bill “Bojangles” Robinson does much better than merely get away with it (and so does Lena Horne).

Some scenes in the above films remind you of the countless short-films that were made to celebrate the merits of this or that orchestra/soloist; they are precious to jazz history, but they generally appear in the margins of contemporay filmmaking, and so remain “out of scope”. It’s a shame, because one of them was a masterpiece: “Jammin’ the Blues”.

JAZZ IN ACTION

Jazz was scarcely heard on the screen until the beginning of the Fifties. Hollywood studios had used a few jazz musicians, of course — occasionally — but the privilege of playing in a film wasn’t within the reach of most. The disbanding of Stan Kenton’s orchestra in California changed a lot of things: the band’s alumni were based in Los Angeles, and they had impeccable technique, not to mention a partiality for written compositions. Their music interested certain film-composers, all the more since Alex North, in his famous score for “A Streetcar named Desire”, had started introducing “jazz” sequences (Four Deuces). Some of directors decided to follow suit.

Shorty Rogers, the trumpeter, composer and arranger, was contacted at his “office”, i.e. the Lighthouse, by Leith Stevens, who offered him the job of working on orchestrations for “The Glass Wall”: Shorty couldn’t have dreamed of a better chance to set foot in the studios.(7) Thanks to Leith Stevens again — they say it was at Marlon Brando’s suggestion — Shorty next found himself with an opportunity to arrange and conduct four pieces for “The Wild One”, and the music couldn’t have found a better home, as it was featured on the juke-box in the scene where the bikers invade a cafe (the beautifully violent Hot Blood). Shorty’s efficient work was never criticized, even though the film caused quite a scandal.

As for Shelly Manne, a partner of Shorty and one of his friends, he put an end to some of Hollywood’s prejudices where jazz drummers were concerned. “The first time I was called to do studio-work, I did what I was supposed to do, but it was very difficult. Because the music was close to jazz, they’d called a jazzman, and the job was to sight-read Leonard Bernstein’s Fancy Free score, written in 5/4, which was unusual for the time. I did it, and since then I’ve been given calls to play all kinds of music. They’d realized that I could play anything, and as a result, they sent calls out to more and more jazzmen.(8)

On the subject of his soundtrack for “The Man with the Golden Arm”, Elmer Bernstein declared, “I want to give credit to Shorty and Shelly for their contributions. Not only did I take them on as consultants, I gave them a free rein at many points so that they could put in whatever corresponded to their own ideas.(9) The film’s story — a musician with a drug-addiction who fails in his attempt to turn professional (the moment that corresponds to Audition) — caused a general outcry, but one could read in The Hollywood Reporter that, “One still has to note the historic contribution to the development of film-music which Elmer Bernstein’s score brings to the film. Until now, jazz has been used as an attraction, or to emphasize a particular scene. It remained for Bernstein to prove that it could be used to provide continuous support for the plot by reflecting the various atmospheres in the entire film.”

Elmer Bernstein would continue in the same direction (“The Sweet Smell of Success”) by appealing to Fred Katz and Chico Hamilton, whose quintet here plays Jonalah. Later, in “Kings Go Forth”, he would use Red Norvo’s sextet twice, with trumpeter Pete Candoli dubbing for Tony Curtis on Britt’s Blues. And Bernstein would later bring in Gerry Mulligan and Paul Horn for “The Rat Race”.

At the time he contacted Shorty Rogers, Leith Stevens had been working in Hollywood since 1939, so he knew exactly what he was doing when it came to choosing an innovative way to renew film-music; and he would resort to the same method on several occasions. Having shown that jazz and violence worked wonderfully together in films, for “Private Hell 36”, a crime-movie, Leith Stevens worked on a score whose spirit would reflect the music written for “The Wild One”. When writing about his music for “The James Dean Story”, the author of the sleeve-notes spoke of the unique way — as unusual as it was efficient — in which Stevens made use of the jazz idiom. The piece Testing the Limits of Life is an illustration of what James Dean’s frame of mind had been during the last months of his life, and it stood out from the rest. It was a paradox that Leith Stevens would receive an Academy Award for his contribution to… “The Five Pennies”.

“The Wild Party” was mentioned almost as a footnote by critics who’d found John McPartland’s screenplay brutally revolting (and there have been others since.) Even so, a marvellous score by arranger Buddy Bregman accompanied the wrongdoings of Tom Kupfen/Anthony Quinn. And it was Pete Jolly who stood in for Kicks/Nehemiah Persoff who, in one scene, accompanies Buddy de Franco.

When Alexandre Courage was entrusted with “Hot Rod Rumble” — a film set against a background of souped-up automobile races — he decided to copy Leith Stevens’ modus operandi when dealing with bikers. He did so daringly, because, after a more or less descriptive exposé, The Race left the field wide open to a succession of musicians: Bob Cooper, Barney Kessel, Bud Shank, Claude Williamson, Herb Geller, Frank Rosolino and Maynard Ferguson.

Henry Mancini used to be the pianist and arranger for the Glenn Miller Orchestra (the version managed by Tex Beneke), and he put together a team of “West Coasters” for the film “Touch of Evil”. He gave the musicians a score where everything was wrtten down, often close in style to the pieces they’d been playing on a daily basis for Kenton (with the exception of the very “bluesy” Reflections.) Mancini later wrote a number of soundtracks where he had recourse to his favourite jazz players whatever their styles, often offering them a “jazz scene” to play. Take Something for Cat for example, from “Breakfast at Tiffany’s”, whose main theme Moon River went on to become a standard that has been performed by countless soloists and orchestras.(10)

Franz Waxman (“Crime in the Streets”), Pete Rugolo (“Jack the Ripper”), Dean Elliott (“College Confidential”), Neal Hefti (“Synanon”) and Stu Phillips (“Hell to Eternity”) also numbered amongst those who, over the years, would call on jazzmen from the West Coast to perform their scores, often destined for B movies.

Johnny Mandel, who wrote for Woody Herman, Count Basie, Stan Getz and Chet Baker, pulled off something of a coup with his very first score for a film. His work for “I Want to Live” was nominated for a Grammy Award, and it was the first U.S. film with an entirely jazz score. Played by a small-group led by Gerry Mulligan, Black Nightgown, like a few other tunes, had to be inserted into the soundtrack whenever an outside source justified a hearing (like a radio-set in the shot, for example).

Divided between traditional film music — which he honoured by his presence — and jazz, André Previn clearly favoured the latter for the screen adaptation of Jack Kerouac’s novel “The Subterraneans”. Despite a piece like Bread and Wine, his score left more than one filmgoer thirsting for more. A few decades later, Previn finally saw justice with the release of a CD containing pieces which had been rejected by the producers for whom they’d been written...

In 1959, The Duke saw himself entrusted with the task of composing the soundtrack for the Otto Preminger film “Anatomy of a Murder”. “I was trying to do background music fittingly. And that, of course, I think was important!”(11) Ellington’s work was crowned “Best Motion Picture Soundtrack of the Year” at the Grammy Awards, and French filmmaker Alain Corneau would say that, “with a highly written, astonishingly bluesy score, Duke Ellington can be situated at the same level, and with the same success, as Bernard Hermann with regard to Hitchcock.”(12)

Ellington received another commission, this time for a film by Martin Ritt, “Paris Blues”. Skilfully adapted from a rather mediocre novel by Harold Flanders, the film dealt with the life of two American jazzmen in the French capital, where the film was shot. The Duke approached the film in three stages, the first being to make some pre-recordings which actors Sidney Poitier and Paul Newman would use to rehearse (and they turned out to be extremely convincing in their roles, too). Next came some fine-tuning in Paris, with priority given to integrating Satchmo into the proceedings: “One thing I knew in advance was there was a lot of Louis (Armstrong) in the picture, so I knew I had to write Louis to sound Louis.”(13) The third and final act was the recording (in New York) of the background music, in the true sense of the word. Part of that is the Autumnal Suite, which accompanies a stroll along the banks of the River Seine (deprived of the two lanes of traffic they carry nowadays, except when they’re turned into a sandy beach in summer…)

After being reduced to walk-on parts, some West Coast musicians finally saw their names on the bill, albeit at the bottom, and sometimes quite unexpectedly. According to Shorty Rogers, “At first, I was slightly apprehensive when MGM approached me to write and record the soundtrack for a Tarzan movie, but I needn’t have concerned myself. They just said, ‘Make it exciting with plenty of drumming,’ and left me alone to get on with it…”(14) The freedom they gave him was most welcome: Oomgawa is one of Shorty’s most successful “exotic” pieces.

Shelly Manne: “In Europe, especially in France, excellent soundtracks were done by Miles Davis, Herbie Hancock. They were perfect because they respected the spirit of the film without intervening, and still remained excellent jazz. That’s what I tried to do for ‘The Proper Time’.”(15) After they’d seen the film over and over again, Joe Gordon, Richie Kamuca, Vic Feldman, Russ Freeman, Monty Budwig and Shelly himself improvised as Miles Davis and his partners had done for the film “Lift To The Scaffold”. For technical reasons, the (remarkable) recording of the music which was released was the fruit of a “remake” in the studio. What about the music accompanying the film? It’s a mystery. Tom Laughlin’s film was never released outside America and has never been issued on DVD… The same goes for the two Bruce Brown productions, “Slippery When Wet” and “Barefoot Adventure”, two surf-films for which Bud Shank composed and recorded music that was quite unexpected given the context. Dance of the Sea Monsters comes from “Barefoot Adventure”, played by a sextet in which the piano is replaced by a guitar.

Even if Hollywood remained in charge, New York quickly had something to say about it all. According to John Lewis, “For me, ‘Odds Against Tomorrow’ was a different experience [from “Sait-on jamais?”], because I had to compose a piece of music that stayed close to the film’s story; the music was genuinely conceived to stick to the film.”(16) That makes it quite a delicate task to choose an excerpt without depriving it of all meaning. United Artists was well aware of that: simultaneously with the release of the original music, a second album appeared in which the Modern Jazz Quartet picked up the film’s main themes. But even so, French director Jean-Pierre Melville deemed that soundtrack to be the best ever written.

Robert Rossen’s film “The Hustler” is today one of the classics of the Seventh Art. Twenty-five years later, Martin Scorsese directed a follow-up to that one with “The Color of Money”, a film on which Gil Evans worked. Curiously, the original score written by Kenyon Hopkins, a solid professional whose filmography already included “Baby Doll” and “Twelve Angry Men”, remains little-known, despite the fact that it features a first-rate team of musicians from New York including Phil Woods and Hank Jones. Likewise, the guitarist Mundell Lowe saves the film “Satan in High Heels”, a low-budget movie (with the smell of scandal at the time of its release) which has escaped oblivion thanks to its music rather than the generous charms unveiled by the females in the cast.

“The Connection” is one of those American independent films that cared little for taboos and didn’t think twice about ensuring support from jazz that was hardly consensual; it had been preceded by “Shadows”, which still carried the halo of Charles Mingus’ contribution. The Cassavetes film, in fact, in the only visible version of it (the second), only allows a hearing of a few solo bass phrases, and an embryonic exposé of Nostalgia in Times Square that punctuates the brawl in the back-room of the café in the film. The rest of the soundtrack has the work of Shafi Hadi on saxophone, playing a cappella behind abundant conversations…

For “The Connection”, Shirley Clarke made as much use of the music of Freddie Redd as she did of the jazzmen who, every night, improvised onstage at the Living Theatre during the performance of the eponymous play. Illustrating the confrontation between a Salvationist and junkies waiting for their supplier, Theme for Sister Salvation went on to enjoy a fine career.

Under the aegis of the French Cinema Critics Association, “The Connection” was presented at the 1961 Cannes Film Festival, although not part of the official selection. French director Edouard Molinaro was on the official jury that year and he was one of the filmmakers thanks to whom France would compete with Hollywood in the Fifties when it came to using jazz as film-music…

JAZZ AND FILM NOIR IN FRANCE

Can “L’amour à l’américaine” (released December 1931) be considered one of the first love-affairs between French films and syncopated music? Opinions diverge, but Ray Ventura (a fan of Paul Whiteman), indeed had a flirt with jazz thanks to Fantastique!, which became his signature-tune.(17)

The presence of Afro-American musicians or orchestras would soon become commonplace in French productions. Freddie Johnson and his musicians were briefly glimpsed playing St. Louis Blues in Jean Renoir’s “Chotard et Cie” (1933). Following America’s example, a number of club-scenes allowed spectators to see — and hear, back behind the dialogue somewhere — the people who made Parisian night-clubs the places to be: Arthur Briggs and His American-Cubano Boys (in “Le roman d’un tricheur” by Sacha Guitry, 1936), Valaida Snow (in Robert Siodmak’s “Personal Column”, 1939), Willie Lewis and His Entertainers (in “Cinderella” by Pierre Caron, 1937), the Bobby Martin Orchestra (in Pierre Chenal’s “L’alibi”, 1936), or Garland Wilson and a chanteuse singing Darling, je vous aime beaucoup (in Curtis Bernhardt’s “Carrefour”, 1938).(18) And, of course, Josephine Baker, who, in the finale of “Zouzou”, after a series of live tableaux, performed C’est lui surrounded by what even the French called “boys”. She was accompanied by an orchestra conducted by ‘Al’ (Alain) Romans. It all carried the kind of agreed exoticism which the Occupation, inevitably, would bring to a halt.

While jazz and pseudo-jazz remained popular in the French capital as a reaction to the diktats of authority, films had to observe great caution. Even the sentimental “Mademoiselle Swing” came close to being banned: a personable young lady in a mask, sliding onstage on a sled to sing, “Forget all your worries, be swing, too…”, was hardly popular with the moral rearmament notions that were dear to the Vichy government. The “Mademoiselle” in question was incarnated by Irène de Trébert, who was all the rage with the “Zazou” subculture of the time (and also one of the rare French female tap-dancers.)

Once France was liberated, Gisèle Pascal played a new ingénue in “Mademoiselle et son flirt”, a film with a cabaret scene in which — apparently — one could see a few French jazzmen including Alain and Boris Vian. Apparently, nothing remains of that film made by Jean de Marguenat, except for a song, Un oiseau chante dans mon cœur, and a novella, “Le figurant”, in which Boris Vian, in his own inimitable way, told the story of the making of the film (it was published in the short-story collection entitled “Les Fourmis”).