- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

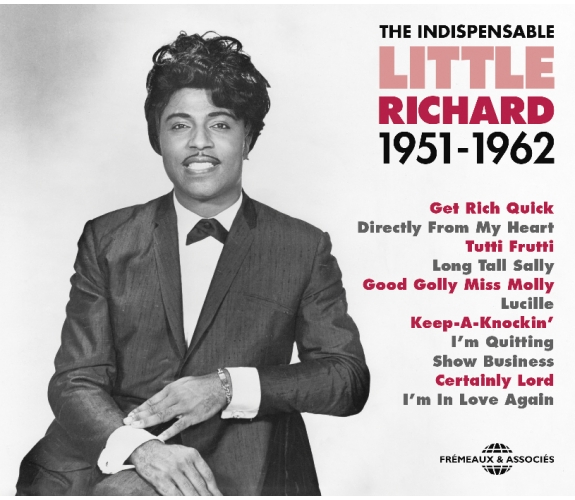

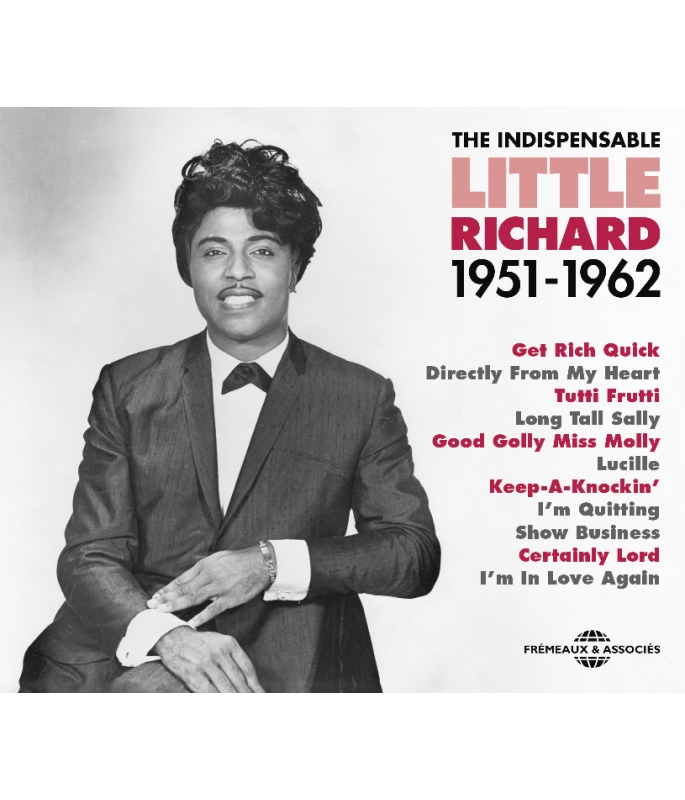

LITTLE RICHARD

Ref.: FA5607

EAN : 3561302560724

Artistic Direction : BRUNO BLUM

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Total duration of the pack : 2 hours 37 minutes

Nbre. CD : 3

Little Richard was the most intense Rock singer ever, a precursor of Soul and a giant of Rock ‘n’ Roll, and his success first thundered through music in 1955: eccentric, extrovert, brilliant and wild, his exciting, incredible story made just as much noise. In the 28-page booklet accompanying this selection, Bruno Blum tells that story from the drag queen revues, the Blues and his triumphs in Rock to the Gospel years as well as his unbelievable comeback. This album is perhaps the most indispensable set in the whole series, and includes many rare recordings which are now finally available to the public. Patrick FRÉMEAUX

“Richard is a supreme star. A once-in-a-millenium talent.” His producer Robert “Bumps” BLACKWELL

ROCK AROUND THE CLOCK

THE INDISPENSABLE 1949-1962

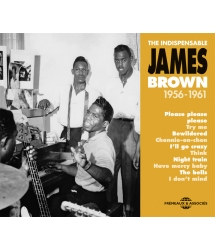

JAMES BROWN

THE INDISPENSABLE 1954-1961

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Every HourLittle RichardRichard Wayne Penniman00:02:551951

-

2Taxi BluesLittle RichardLeonard Feather00:02:191951

-

3Get Rich QuickLittle RichardLeonard Feather00:02:181952

-

4Thinkin' About My MotherLittle RichardRichard Wayne Penniman00:02:541952

-

5Please Have Mercy On MeLittle RichardJoe Thomas00:02:331952

-

6Fool At The WheelLittle Richard, The Deuces Of Rhythm and The tempo ToppersRaymond Taylor00:02:411953

-

7Ain't That Good NewsLittle Richard, The Deuces Of Rhythm and The tempo ToppersRaymond Taylor00:02:531953

-

8Directly From My HeartLittle RichardRichard Wayne Penniman00:02:571953

-

9Little Richard S BoogieLittle RichardRichard Wayne Penniman00:02:511953

-

10Maybe I'm RightLittle RichardRichard Wayne Penniman00:02:511953

-

11Lonesome And BlueLittle Richard And His BandRichard Wayne Penniman00:02:181955

-

12All Night LongLittle Richard And His BandRichard Wayne Penniman00:02:161955

-

13Directly From My HeartLittle RichardRichard Wayne Penniman00:02:211955

-

14Maybe I'm RightLittle RichardRichard Wayne Penniman00:02:101955

-

15BabyLittle RichardRichard Wayne Penniman00:02:061955

-

16I'm Just A Lonely GuyLittle RichardD. Labostrie00:02:391955

-

17Tutti FruttiLittle RichardD. Labostrie00:02:271955

-

18Chicken Little BabyLittle RichardRichard Wayne Penniman00:02:011955

-

19True Fine MamaLittle RichardRichard Wayne Penniman00:02:441955

-

20Kansas City Hey Hey HeyLittle RichardJerry Leiber00:02:411955

-

21Wonderin'Little RichardRichard Wayne Penniman00:02:511955

-

22Miss AnnLittle RichardRichard Wayne Penniman00:02:171956

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Long Tall SallyLittle RichardRobert Blackwell00:02:121956

-

2Slippin' And Slidin'Little RichardRichard Wayne Penniman00:02:411956

-

3The Most I Can OfferLittle RichardScott William00:02:221956

-

4Oh Why ?Little RichardScott William00:02:101956

-

5I Got ItLittle RichardRichard Wayne Penniman00:02:201956

-

6Reddy TeddyLittle RichardRobert Blackwell00:02:101956

-

7Hey Hey Hey Hey (Goin Back To Birmingham)Little RichardRichard Wayne Penniman00:02:061956

-

8Rip It UpLittle RichardRobert Blackwell00:02:251956

-

9LucilleLittle RichardRichard Wayne Penniman00:02:251956

-

10Heeby-JeebiesLittle RichardMichael James Jackson00:02:151956

-

11All Around The WorldLittle RichardRobert Blackwell00:02:291956

-

12Can't Believe You Wanna LeaveLittle RichardLloyd Price00:02:271956

-

13Shake A HandLittle RichardJoe Morris00:02:521956

-

14She's Got ItLittle RichardJohn Marascalco00:02:281956

-

15Jenny JennyLittle RichardRichard Wayne Penniman00:02:041956

-

16Good Golly Miss MollyLittle RichardRobert Blackwell00:02:131956

-

17Baby FaceLittle RichardH. Akst00:02:161956

-

18The Girl Can't Help It Take 9Little RichardBobby Troup00:02:271956

-

19By The Light Of The Silvery MoonLittle RichardEdward Madden00:02:081956

-

20Send Me Some Lovin'Little RichardJohn Marascalco00:02:221956

-

21The Girl Can't Help It Take 12Little RichardBobby Troup00:02:311956

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Keep-A-Knockin'Little RichardPerry Bradford00:02:201957

-

2Ooh ! My SoulLittle RichardRichard Wayne Penniman00:02:081957

-

3I'll Never Let You Go (Boo Hoo Hoo Hoo)Little RichardRichard Wayne Penniman00:02:241957

-

4Early One MorningLittle RichardRichard Wayne Penniman00:02:171957

-

5She Knows How To RockLittle RichardRichard Wayne Penniman00:02:021957

-

6Whole Lotta Shakin' Goin OnLittle RichardDave Williams00:01:571957

-

7LucilleLittle Richard And The UpsettersAlbert Collins00:03:001957

-

8Long Tall SallyLittle Richard And The UpsettersRichard Wayne Penniman00:02:081957

-

9I'm Quitting Show BusinessLittle RichardRichard Wayne Penniman00:03:021959

-

10Milky White WayLittle RichardTraditionnel00:03:161959

-

11I've Just Come From The FountainLittle RichardTraditionnel00:01:461959

-

12Coming HomeLittle RichardRichard Wayne Penniman00:02:471959

-

13Certainly LordLittle RichardTraditionnel00:01:591959

-

14It's RealLittle Richard King Of GospelHomer L. Cox00:03:161961

-

15Joy, Joy, JoyLittle Richard King Of Gospel00:02:201961

-

16Crying In The ChapelLittle Richard00:02:241962

-

17Hole In The WallLittle RichardTerry Taylor00:02:301962

-

18Every Night About This TimeLittle RichardDave Bartholomew00:03:051962

-

19I'm In Love AgainLittle RichardDave Bartholomew00:02:051962

-

20Valley Of TearsLittle RichardDave Bartholomew00:03:211962

-

21Freedom RideLittle RichardJoe Hughes00:01:581962

Little Richard FA5607

THE INDISPENSABLE

LITTLE RICHARD

1951-1962

Get Rich Quick

Directly From My Heart

Tutti Frutti

Long Tall Sally

Good Golly Miss Molly

Lucille

Keep-A-Knockin’

I’m Quitting

Show Business

Certainly Lord

I’m In Love Again

Par Bruno Blum

Long tall Sally she’s built for speed/She’s got everything uncle John needs1.

Richard Wayne Penniman est né le 5 décembre 1932, troisième d’une fratrie de douze enfants à Macon en Georgie (près de la Floride). Ses parents étaient issus de familles nombreuses. Femme de caractère, sa mère Leva Mae née Stuart venait d’une famille aisée et cultivée, à la peau relativement claire (« je pense qu’ils avaient du sang indien2 »). Son frère Louis était un pasteur baptiste. Leva Mae n’avait que quatorze ans quand elle s’est mariée avec Charles Penniman dit Bud, un maçon fils du pasteur Walter Penniman. Dans certains counties (régions), l’alcool restera prohibé jusqu’à nos jours. La vente et la consommation d’alcool étaient interdits en Georgie quand Bud vendait un whisky artisanal, le « moonshine ». La famille Penniman était équilibrée et avait un pouvoir d’achat moyen. Bébé de grande taille, fort et avec une grande personnalité, Richard devint un enfant très turbulent, toujours à commettre des transgressions, des farces cruelles, mentant pour échapper aux coups de ceinture, qu’il reçut abondamment comme punition. Il aimait choquer, provoquer et énerver les gens, particulièrement les adultes. Né avec une tête trop grosse, surnommé « grosse tête » à l’école, Richard avait une jambe trop courte. Boiteux, il était moqué par ses camarades. Sa démarche précieuse fut très tôt jugée efféminée. De petite taille, il n’aimait pas jouer avec les garçons et avait beaucoup d’amies filles.

Negro Spirituals

À Macon comme partout dans le sud, les ghettos de la ségrégation raciale vibraient au son de chants libérateurs religieux et profanes3. Ouvriers, enfants, ménagères, tous chantaient spontanément des spirituals comme « Motherless Child » ou « Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen » repris en chœur par toute la rue4. L’esprit de solidarité était alors très répandu, ce qui permit à son père de ne pas se faire arrêter ou dénoncer quand il vendait son alcool prohibé chez lui. Encadré par des dames de l’église, avec ses frères Richard participait à une formation vocale d’enfants, les Tiny Tots. Ils rejoignaient fréquemment un groupe de femmes adultes, qui chantaient des spirituals en tapant des pieds en rythme avec ferveur. Très jeune, il voyageait déjà en voiture dans la région pour chanter lors de réunions religieuses : camp meetings de campagne et temples protestants où ils chantaient « Peace in the Valley » ou « Precious Lord ». Richard se tenait tranquille dans cette seconde famille fraternelle qui l’initia au piano et au chant.

Le producteur de ses succès Bumps Blackwell le décrira comme incapable de prendre une décision et de s’y tenir. L’enfant oscillait déjà entre le garnement et le bon élève très pieux. En 1959 c’est dans le giron des congrégations qu’il reviendra enregistrer le gospel « Coming Home » (« Je reviens à la maison »). À dix ans, Richard se présentait comme un guérisseur qui agissait en chantant. À douze ans (1945) il fut engagé comme vendeur de boissons à l’auditorium de Macon, ce qui lui permit de voir sur scène Cab Calloway, Hot Lips Page, Cootie Willliams, Lucky Millinder et son idole, la chanteuse-guitariste de gospel Sister Rosetta Tharpe5. L’enfant lui chanta deux de ses succès dans les coulisses. La grande vedette l’invita à les chanter sur scène et lui donna quarante dollars pour sa prestation, une forte somme. L’enfant restera très marqué par cet événement.

Mauvais élève, Richard maîtrisa vite le saxophone alto et rejoint le groupe du collège. Attiré par les garçons, il se sentait différent. Il était très jeune quand il eut une première relation sexuelle avec une fille plus âgée que lui, qui le déniaisa. Cette rencontre fut vite suivie par une fellation d’un pédophile qui payait de jeunes adolescents pour ça. Catalogué « sissy », Richard reçut des propositions d’adultes blancs et traînait avec deux homos de son âge. Ils étaient poursuivis et harcelés par leurs camarades. Richard aimait les mauvaises plaisanteries et son frère dut se battre plusieurs fois pour le protéger contre les autres garçons. Il était la terreur de tous ses professeurs, aimait se faire remarquer, chanter et hurler en public en tapant bruyamment sur des casseroles et des marches d’escalier pour s’accompagner. Il faisait partie du groupe de gospel familial The Penniman Singers, où sa tendance à chanter trop fort et très haut, à hurler lui causait sans arrêt des remontrances. Sa mère fréquentait avec lui la New Hope Baptist Church de la Troisième Avenue et son père le temple (African Methodist Episcopal Church) de Madison Street. Mais Richard préférait l’exubérance et l’intensité musicale propre aux cérémonies pentecôtistes6. Avec ses copains il y imitait la glossolalie (« speaking in tongues », improvisations vocales inspirées par la ferveur) des fidèles en riant. Son cousin germain Amos Penniman était pasteur pentecôtiste et le jeune Richard avait pour idole Brother Joe May, un évangéliste chantant surnommé « The Thunderbolt of the West ». Il rêvait de devenir pasteur à son tour. C’est ce qu’il essaiera de faire à l’âge de vingt-cinq ans après une carrière fulgurante de chanteur de rock.

Tent Queen Shows

Son père le critiquait pour sa démarche et ses manières efféminées. Cancre et libertaire, se sentant rejeté par sa famille il fréquentait des camelots, des charlatans vendant des élixirs lors de spectacles de rue. Richard y participa en chantant pour attirer les clients. À l’âge de quatorze ans il partit en tournée avec le Dr. Hudson Medicine Show qui vendait sa panacée « l’huile de serpent » (le serpent est un symbole du vaudou, une religion animiste considérée maléfique par les chrétiens) aux passants superstitieux. Accompagné par un pianiste, Richard interprétait « Caledonia » de Louis Jordan, son premier morceau non religieux. Il dormait à la belle étoile dans les champs. Recueilli par Ethel Wynnes, propriétaire du club Winsetta Patio sur East Pine Street, il remplaça le chanteur de B. Brown & his Orchestra. En tournée avec eux dans toute la Georgie en 1947, il interprétait des ballades comme « Goodnight Irene », un standard folk. Annoncé pour la première fois sous le nom de « Little Richard » peint sur la voiture bâchée du groupe, le chanteur portait déjà sa coupe « pompadour » et se produit avec succès devant sa famille à Macon. Son père accepta sa nouvelle carrière. Sa mère le trouvait trop jeune pour partir seul. Little Richard rejoint une autre troupe moins âgée, le minstrel show de Sugarfoot Sam, un spectacle de vaudeville où il joua un rôle habillé en femme. Il rejoint ensuite le King Brothers Circus puis les Tidy Jolly Steppers où il chantait avec une robe de femme. Il fit de même dans le L. J. Heath Show (un autre minstrel show) parmi d’autres travestis maquillés, portant des faux cils. Ses contacts avec le milieu homosexuel se multiplièrent. Il fut engagé dans les Broadway Follies, un spectacle incluant des travestis. Il chanta chaque semaine dans la capitale de la Georgie, l’immense Atlanta où le très influent rhythm and blues connaissait un âge d’or dans les nombreuses boîtes du quartier d’Auburn Avenue, dont plusieurs fréquentées par des homos. À la fin des années 1940 le rock and roll originel était né et ségrégation raciale oblige, il restait encore confiné au public noir7. Little Richard se produisait dans le même spectacle que Chuck Willis ; dirigées par le comédien Snake, les Broadway Follies partageaient l’affiche avec B.B. King, Jimmy Witherspoon et d’autres vedettes de la région. C’est à Atlanta que Little Richard rencontra Billy Wright (« The Prince of the Blues »), un chanteur « shouter » très influencé par le gospel qui s’habillait de façon voyante et eut un impact déterminant sur l’adolescent. Billy Wright était homosexuel et son succès dans le style « jump blues » (le rock avec des riffs de cuivres à la mode swing, comme ici Get Rich Quick) fut influent en 1949-1951. Little Richard adopta même son fond de teint, le Pancake 31, et une coupe de cheveux « pompadour » outrée (très gonflée sur le haut du crâne). Billy Wright chantait dans des spectacles de travestis, les tent queen shows, une tradition de cabaret du sud des États-Unis initialement développée sous des tentes. On pouvait y écouter un répertoire graveleux traditionnel comme « Don’t You Want a Man Like Me » (« Confessin’ the Blues » de Jay McShann), que Richard interprétait à merveille, faisant rire son auditoire. Il emprunta aussi à Billy Wright « Busy Bootin’ » (parodie du standart Keep a Knockin’) et son futur premier succès (ici avant modification des paroles), une parodie d’un titre Slim & Slam8 :

Tutti Frutti/Good bootie/If it don’t fit/don’t force it/Just grease it/Make it easy

Billy Wright présenta Little Richard à l’un des premiers disc-jockeys blancs à diffuser de la musique noire, Zenas Sears. C’est à la radio de Macon WGST que, grâce à Sears qui avait obtenu un budget des disques RCA, Little Richard enregistra ses premiers titres avec les musiciens de Wright. Succès local grâce à la diffusion de Zenas Sears, Every Hour est marqué par le style de son mentor. C’est d’ailleurs Billy Wright lui-même qui, à la demande de Lee Magid, producteur chez Savoy, plagia le morceau sous le nom de « Ev’ry Evenin’ » et en tira un vrai succès. Plusieurs autres titres furent gravés par Richard pour RCA. Heureux que ce premier disque soit bien accueilli, à la suggestion de leur manager Horace Edwards son père lui donna la permission de rejoindre l’orchestre du bassiste Percy Welch. Avec eux Little Richard chanta le standart des travestis « Don’t You Want a Man Like Me » jusque dans le Kentucky et le Tennessee. C’est dans la salle d’attente de nuit de la station de car Greyhound de Macon, seul endroit ouvert la nuit de la ville et lieu de drague, que Little Richard rencontra le pianiste de jazz Esquerita. Le musicien accompagnait Sister Rosa, une chanteuse de gospel qui vendait du pain béni. Comme lui, Esquerita était marqué par la tradition des tent queen shows9 et portait coiffure pompadour et costumes excentriques. Il tomba sous le charme de Little Richard et lui enseigna le piano. Il enregistrera en 1958 un album très influencé par Little Richard, qui enregistra à nouveau en 1952 (seuls les meilleurs enregistrements pour RCA sont inclus ici).

Un mois plus tard, le père de Richard fut assassiné d’une balle dans une altercation stupide. Richard était réconcilié avec son père, qui était sur le point de lui offrir une voiture10. Leva Mae était enceinte et la famille plongea aussitôt dans la misère. Le grand frère était à la guerre de Corée et Richard dut faire la plonge à la station Greyhound pour nourrir la famille. Managé par Clint Brantley, il forma ensuite les Tempo Toppers avec les frères Taylor. Ils séjournèrent longuement à la Nouvelle-Orléans pour un engagement au Tijuana Club où il devint ami avec le chanteur-guitariste Earl King. Mais c’est en tournée à Houston qu’il rencontra le leader d’orchestre Johnny Otis. Otis repéra Richard lors d’un déjeûner au Club Matinee où le chanteur se produisait avec exubérance, provocation, érotisme et flamboyance. Richard s’était présenté à la fin du spectacle comme « le roi du blues » puis ajouta « et aussi la reine ! ». Les disques Peacock le firent enregistrer mais les morceaux ne reflétaient pas l’aura excentrique de Little Richard et n’eurent aucun succès. À la suite d’un différend financier, le patron de Peacock Don Robey passa Richard à tabac. Fin 1953, Little Richard poursuivit une carrière solo avec le guitariste Thomas Hartwell.

The Upsetters

Le chanteur commençait à se lasser de l’influence du gospel. Il souhaitait se tourner plus vers le rock ‘n’ roll, un style énergique qui plaisait au public en concert et avait fait connaître des artistes noirs comme Jackie Brenston and his Delta Cats (« Rocket 88 » et « My Real Gone Rocket », 1951) ou Wally Mercer (« Rock Around the Clock », 1952). Il tomba sur ses copains de la Nouvelle-Orléans Chuck Connor, un des meilleurs batteurs de l’époque, et le pianiste saxophoniste Wilbert Smith. Ils accompagnaient Shirley and Lee. Baptisant son nouveau groupe The Upsetters, Richard ajouta deux saxophones à leur formation et repartit en tournée avec succès11. Leur répertoire puisait dans les compositions plus nerveuses de B.B. King, Little Walter, Fats Domino — et de deux des véritables artistes fondateurs du rock ‘n’roll : le « Keep Your Hand on Your Heart » de Billy Wright et Roy Brown. Mais leur grand succès était la parodie de Tutti Frutti.

Specialty

« Lawdy Miss Clawdy » était l’un des grands succès noirs de l’époque. Le chanteur Lloyd Price joua un soir à l’auditorium de Macon. Il suggéra à Little Richard d’envoyer un enregistrement à Art Rupe, le patron des disques Specialty à Los Angeles. Enregistrée en février 1955 à la radio WBML de Macon, la maquette de Wonderin’ était un plagiat « d’un copain ». « He’s my Star » était un autre blues marqué par le style gospel. Mais Art Rupe ne réagit pas. Richard organisait alors des relations sexuelles à trois où il était voyeur. Il emmenait sa copine Fanny en voiture et lui demandait de séduire un homme. Richard emmenait alors les partenaires dans un coin tranquille et les regardait faire l’amour tandis qu’il se masturbait. Dénoncé à la police par un pompiste qui les épiait dans une aire de stationnement, il fut arrêté et emprisonné plusieurs jours pour outrage aux mœurs. L’avocat envoyé par sa mère obtint sa libération mais Richard était désormais interdit de séjour à Macon — la ville de son enfance et de sa famille — et se consacra alors à la scène. Il sillonna le sud et construit un nouveau répertoire au fil de 1955. En septembre Specialty le contacta enfin : le producteur maison Bumps Blackwell lui proposa une séance de studio à la Nouvelle Orléans. Blackwell était noir, mais il avait été formé à la composition à l’université de Los Angeles dans la tradition blanche de la musique écrite. À la fin des années 1940 il avait mené un orchestre de jazz où jouaient les jeunes Ray Charles et Quincy Jones. Engagé par Art Rupe chez Specialty en 1949, c’est ce fin musicien qui avait repéré la maquette de Richard et l’enregistra pour la première fois dans le légendaire studio de Cosimo Matassa à la Nouvelle-Orléans. Dans le contexte de la ségrégation raciale, le public noir ne s’intéressait

pas souvent aux artistes blancs – qui de surcroit copiaient de plus en plus souvent le style et les idées des artistes noirs. Le marché des musiques afro-américaines était fourni par des marques indépendantes comme Specialty, fondé en 1944 à Hollywood par Art Rupe (né Goldberg), un homme d’affaires juif blanc tombé amoureux des musiques noires après avoir écouté du gospel dans une église baptiste de son quartier à Pittsburgh.

Specialty comptait déjà parmi les premières et meilleures de ces nouvelles marques « noires ». Dans la tradition des producteurs de jazz juifs comme Alfred Lion (Blue Note) avant lui, Rupe répondait à la demande en produisant la musique noire à la mode, lançant Sam Cooke et Lloyd Price entre autres. En 1955, tous les producteurs cherchaient des artistes capables de reproduire la formule du « I’ve Got a Woman » de Ray Charles : un rock profane au style imprégné par le chant gospel12. Little Richard aimait le son de la Nouvelle-Orléans et c’est là, au studio de Cosimo Matassa où travaillaient Fats Domino et Lloyd Price que Bumps Blackwell lui donna rendez-vous. Une fois son contrat racheté à Peacock, ils enregistrèrent quelques blues avec la crème des musiciens locaux, dont l’essentiel géant de la batterie Earl Palmer. Mais Blackwell savait que les morceaux lents gravés là n’auraient pas de succès.

Tutti Frutti

À la pause déjeûner du deuxième jour, Little Richard se mit au piano du Dew Drop Inn pour montrer son style au saxophoniste Lee Allen. Soudain exposé au jeune public de l’auberge, il hurla « womp-bop-aloo-momp-alop-bomp-bomp » et enchaîna la version parodique sexuellement explicite de Tutti Frutti héritée de Billy Wright. Bumps sut immédiatement qu’il tenait un succès monstre. Dorothy LaBostrie en réécrit les paroles sur le champ. Richard joua le piano lui-même et en trois prises improvisées, Tutti Frutti était achevé. Ce même après-midi, il avait enregistré un chef-d’œuvre de la soul (I’m Just a Lonely Guy) et un chef-d’œuvre du rock. Après le tranquille « I’ve Got a Woman », le « Maybellene » de Chuck Berry fut le premier succès « rock » grand public. Sur WLAC (Tennessee), Gene Nobles était l’un des tout premiers disc jockeys à diffuser des musiques noires à la radio. Il annonça en octobre 1955 que Tutti Frutti était un succès partout dans le pays (limité au marché du public noir). Elvis Presley n’avait pas encore signé avec les disques RCA. Le « Rock Around the Clock » de Bill Haley faisait un malheur depuis l’été. La vague rock commençait à prendre de l’ampleur.

Tutti Frutti arrivait au bon moment. Plus radical, plus excitant, avec cette voix possédée, puissante et électrique, loin du pépère Fats Domino ou du raffiné Ray Charles : cette fois l’énergie pure portait le morceau13. Le rythme soutenu, le swing d’Earl Palmer, le style de piano et surtout les cris, la voix démente de Little Richard… l’héritage parodique des spectacles travestis du sud avait accouché d’une formule magique. Richard a soudain refusé d’honorer une série d’engagements prévus. Le débutant James Brown le remplaça, présenté en scène sous le nom de Little Richard. Brown enregistrera bientôt Chonnie-Chon-Chon dans le style rock de Richard14. Il sera bientôt remplacé par Otis Redding, un autre imitateur débutant qui idolâtrait Richard15. La nouvelle star fut aussitôt invitée à Los Angeles par Specialty. Arrivé avec sa coiffure surélevée d’au moins vingt centimètres, ses habits très colorés, ses manières affectées, ses déclarations tonitruantes et vaniteuses il se fit beaucoup remarquer. Ses préférences sexuelles ostensibles participaient à marquer les esprits. Nombre de groupes ont mis « Tutti Frutti » à leur répertoire. Le mièvre Pat Boone l’enregistra vite avec grand succès. Elvis l’enregistra quelques jours plus tard en janvier 1956. Vite sortie chez RCA en pleine Elvismania, sa version, bien qu’inférieure, eut un impact important16.

Have some fun tonight

Les disques rapportaient peu aux artistes, surtout quand ils étaient noirs (un demi cent par 45 tours). Little Richard partit sur la route avec les Upsetters pour rentabiliser son succès. Avec Cherie Landry comme manager et Henry Nash comme régisseur, accompagné par d’excellents musiciens, ils répétèrent un spectacle imbattable. Blackwell fut contacté par un disc jockey qui lui présenta Enortis Johnson, une adolescente venue d’Opelousas en Louisiane. Elle avait écrit les incompréhensibles paroles de ce qui deviendrait vite Long Tall Sally et ses vers sulfureux « I saw Uncle John talking to “Long Tall Sally”. She saw me comin’ and he ducked back in the alley17 ». D’abord réticent, Richard y ajouta l’accroche « have some fun tonight » et ce fut son deuxième single, instantanément numéro un des ventes R&B.

Une insipide version de Pat Boone se vendit à plus d’un million d’exemplaires. Richard acheta alors une grande maison avec étages, jardin, sols et statues de marbre à sa mère, qui déménagea avec toute sa famille au 1710 Virginia road, un quartier riche de Los Angeles. Les Penniman avaient pour voisins Joe Louis, le champion du monde de boxe. Ils n’avaient jamais vu de Noirs vivre dans une telle maison. Richard acheta une Cadillac couleur or. Selon lui, ce fut la période la plus heureuse de sa vie. Il continua à produire des bombes. Rip It Up sortit en juin et monta au numéro un. Elvis Presley, Buddy Holly et Bill Haley l’enregistrèrent aussi. Ses apparitions télévisées, ses concerts et ses disques contribuaient à faire reculer les tabous raciaux18. Dans un pays où un Noir séduisant une femme blanche risquait d’être assassiné, Little Richard se protégea en adoptant une attitude outrancière qui le ferait passer pour un fou inoffensif. Il monta sur scène déguisé en reine d’Angleterre, puis en pape Pie XII. Il brillait comme un quasar et agissait sans barrière, les mèches de cheveux dans la figure, dégoulinant de sueur, secouant la tête, dansant librement et incitant la foule à se lâcher complètement comme lui à une époque où les spectacles étaient polis, convenus. Little Richard et les Upsetters déferlaient sur l’Amérique. Noirs et Blancs se mélangeaient dans la danse. Aucune salle n’était assez grande pour eux. Alors qu’Elvis Presley était au sommet de sa gloire et reprenait ses chansons, Little Richard en composait sans arrêt de nouvelles et ne reculait devant rien : très maquillé, habillé avec des costumes de diamant, des couleurs criardes il montait sur le piano, se déshabillait sur scène, descendait dans la salle, sautait, hurlait, dansait sans retenue… personne n’avait jamais vu ça. Elvis Presley faisait scandale mais n’en faisait pas le dixième. À Baltimore, une pluie de culottes et de panties tomba sur Richard et son groupe. Les concerts devaient être interrompus pour empêcher des filles hystériques de monter sur scène arracher les habits du chanteur en souvenir. À El Paso au Texas, le chanteur fut emprisonné parce qu’il osait porter des cheveux longs, mais globalement leur triomphe se passait bien. Adulé par un public majoritairement blanc, Little Richard et ses musiciens étaient poursuivis par des jeunes femmes avec qui ils organisaient des soirées et des orgies. Comme à son habitude, Richard se masturbait en regardant ces scènes. « Je regardais ces gens coucher avec mes musiciens. Je payais un type avec un gros pénis pour qu’il couche avec des dames et je les regardais faire. […] Toutes mes activités gay tournaient autour de la masturbation. Je faisais ça six ou sept fois par jour […] je me sentais mal après. Je me détestais, je ne voulais pas en parler, ni répondre à des questions. Je me demandais « pourquoi fais-tu ça ? » Tu es fou ? La plupart des gays tombent amoureux d’eux-mêmes19. » Il rencontra alors Angel, qu’il rebaptisa Lee Angel. Cette beauté noire d’à peine dix-sept ans, mince, aux traits de femme blanche et aux énormes seins, était prête à tout pour lui plaire, y compris à séduire quatre hommes très beaux et faire l’amour avec les quatre à la fois devant Richard, qui se masturbait compulsivement tandis qu’Angel lui léchait les tétons. Danseuse, mannequin nue, strip-teaseuse, Angel ne le quittait plus. Le sexe devint leur principale activité hors scène (Richard racontera une orgie avec Buddy Holly). Préférant enregistrer avec les Upsetters, Richard dirigea plusieurs séances à Los Angeles puis céda aux exigences de Blackwell qui préférait la formule avec Earl Palmer. Lucille fut un énorme succès. Basé sur le riff accéléré de son blues Directly From my Heart, il y fait allusion à un travesti surnommé Queen Sonya rebaptisé Lucille. Quant à Good Golly Miss Molly, Richard avait entendu le DJ Jimmy Pennick utiliser cette expression. Le riff de guitare a été emprunté au « Rocket 88 » de Jackie Brenston. She Knows How to Rock est dérivé du « Rockin’ With Red » de Piano Red (1950)20. Le survolté Keep a Knockin’ avait été enregistré par nombre d’artistes blancs dont Milton Brown et Adolf Hofner21. En dépit de ces emprunts, le style de Richard était inimitable. Les plus grandes vedettes du rock blanc enregistraient ses chansons : Bill Haley22, Elvis Presley23 (4 titres), Carl Perkins, Gene Vincent24, Jerry Lee Lewis25 (qui copiait aussi son style de piano), Buddy Holly26, les Everly Brothers, Pat Boone, Eddie Cochran27 — mais aucune de ces versions ne surpassaient les siennes.

The Girl Can’t Help It

À la suite du succès du film Blackboard Jungle (Graine de violence, Richard Brooks, sorti en mars 1955) qui avait lancé le « Rock Around the Clock » de Bill Haley et la mode du rock dans le public blanc, le producteur Sam Katzman tourna un nouveau film rock, Don’t Knock the Rock (Alan Dale, 1956). Little Richard y chante Tutti Frutti et Long Tall Sally qui firent souffler un vent de liberté inspirant toute sa génération. Mais c’est dans The Girl Can’t Help It (Frank Tashlin, décembre 1956), le meilleur film du genre rock, que Little Richard se taille la part du lion : trois chansons (She’s Got It — un remake de I Got It —, The Girl Can’t Help It et Ready Teddy) aux côtés du sex symbol Jayne Mansfield et de royales apparitions de Julie London, Abbey Lincoln, Gene Vincent, Fats Domino, Eddie Cochran, des Platters, des Treniers et d’autres. La chanson The Girl Can’t Help It (dans une version différente de celle du film) et le film furent d’énormes succès. Little Richard était maintenant une vedette internationale. She’s Got It, Send Me Some Lovin’, Miss Ann, Jenny Jenny, Keep a Knockin’ et d’autres furent de nouveaux succès. Little Richard gagnait dix ou quinze mille dollars tous les soirs rien qu’en cachets. Une valise pleine de billets de banque ne le quittait pas. Le coffre de sa Cadillac était plein à ras bords de billets qu’il distribuait par poignées à ceux qu’il aimait. Son triomphe était sans limite.

King of Gospel

Bien qu’il n’ait pas bu une goutte d’alcool28 (il préférait le café), son image androgyne chargée de sexualité, dénoncée comme diabolique par les bien-pensants alors que le rock faisait scandale, était en contradiction avec la religion dans laquelle il avait grandi. Sans parler des orgies, qui selon ses propres dires étaient devenues une terrible addiction. Brother Wilbur Galley, un missionaire de la United Church of God and the Ten Commandments, frappa un jour à sa porte. Il évangélisait des vedettes du quartier avec une rhétorique convaincante. Richard le reçut à bras ouverts. Galley le mit en contact avec Joe Lutcher, un sax/chanteur de rock dont le « Rockin’ Boogie » (1947) produit par Art Rupe avait été l’un des premiers succès de Specialty. Lutcher avait quitté le monde du spectacle, devenant un prêcheur Adventiste du Septième Jour. Poursuivi par le fisc, épuisé par les tournées sans fin, très controversé, menacé et harcelé par des organisations racistes qui haïssaient le rock ‘n’ roll, Richard était mûr, sur le point de craquer. Il avait plus d’une fois alerté son entourage en leur lisant la Bible. Fin septembre 1957, il s’envola pour une tournée australienne avec Gene Vincent, Eddie Cochran et Alis Lesley. Richard avait peur en avion et n’avait encore jamais quitté l’Amérique. Survolant le Pacifique il crut son avion en feu et pensa qu’il devait la vie à des anges qui le portaient. Cinq concerts plus tard le 11 octobre 1957, il enregistrait une émission de radio (dont deux titres suractivés sont inclus ici) et chantait devant quarante mille personnes dans une arène en plein air à Sydney. En plein concert il aperçut un objet volant non identifié, une boule de feu dans le ciel, (il supposera plus tard qu’il s’agissait de la fusée du Sputnik I russe, premier satellite artificiel de l’histoire, mais celui-ci avait été mis en orbite le 4). Croyant à un signe céleste, il abandonna le piano en plein morceau et quitta la scène sans crier gare. Sa décision était prise : il laissait tout tomber et rentrait chez lui. Il se consacrerait à Dieu. La troupe interloquée s’envola pour Los Angeles le lendemain, perdant un demi-million de dollars de 1957 en cachets australiens, une véritable fortune. Selon Richard l’avion qu’ils auraient dû prendre plus tard pour rentrer d’Australie s’écrasa dans la mer, ce qu’il perçut comme un autre signe divin. Il refusa de se présenter à cinquante engagements déjà signés, avec acomptes versés, n’acceptant qu’un concert d’adieu à l’Apollo de New York pour son ami DJ Alan Freed. Au grand dam de ses millions de fans, il partit rejoindre l’adventiste Lutcher et un nouveau mode de vie.

En comparaison avec nombre d’autres mouvements religieux américains, les adventistes sont plutôt libéraux, progressistes. Ils encouragent un régime sain, végétalien, connu pour son raffinement et sa qualité. Le chanteur dira plus tard que cette alimentation est à la source de son exceptionnelle énergie et de sa longévité29. Lutcher et Little Richard montèrent ensemble le Little Richard Evangelist Team et partirent en mission à travers le pays pour aider les indigents en difficulté. Richard servait dans les camp meetings (tentes), lavant les pieds des membres avant la communion, s’affairant et priant à tout moment. Il s’engagea dans une formation de trois ans au collège d’Oakwood (Alabama) pour devenir pasteur. Angel disparut. Il rencontra en novembre Ernestine Campbell, une secrétaire adolescente qui avait à peine terminé ses études et rejoint la marine militaire, l’U.S. Navy où travaillait toute sa famille. Il se marièrent en juillet 1959. Souvent absent, très demandé, Richard était absorbé par ses activités religieuses. Il enregistra cinq gospels pour George Goldner, le producteur de Frankie Lymon, (disques End, Roulette, Goldisc) avec une congrégation anonyme. Goldner a sorti deux albums sous le nom de Little Richard, mais la voix du chanteur ne figure que sur les cinq titres inclus ici. Le charismatique Richard appréciait les leçons mais mauvais élève, il était toujours en retard. Il venait en cours dans sa Cadillac jaune : Les élèves le suppliaient de leur chanter du rock. Il dérangeait les classes. Son homosexualité fut découverte à la suite d’une aventure avec un étudiant ; furieux d’être démasqué, il se sentit coupable d’avoir menti et quitta brusquement l’institution. Specialty continuait à sortir ses enregistrements inédits de 1956-57. Devenu directeur artistique de Mercury, Bumps Blackwell lui proposa d’enregistrer un album de gospel avec Quincy Jones, un arrangeur réputé. La voix de Richard n’est présente que sur deux titres de l’album King of Gospel sorti sous son nom : il est arrivé avec dix heures de retard à la séance où quarante musiciens l’attendaient, annonçant calmement « Le Seigneur ne voulait pas que j’enregistre aujourd’hui ». Il donna alors des concerts avec son amie Mahalia Jackson puis enregistra Crying in the Chapel, un 45 tours Atlantic en hommage à son épouse Ernestine. Mais le mariage était un échec.

Come Back

Don Arden lui proposa soudain une tournée anglaise en tête d’affiche avec Sam Cooke et Gene Vincent. Little Richard était annoncé partout comme chanteur de rock mais l’intéressé croyait être engagé pour chanter du gospel. Ce qu’il fit le premier soir avec Billy Preston (seize ans) à l’orgue — un désastre pour le public anglais, très déçu. Mais quand Sam Cooke (qui avait abandonné sa brillante carrière dans le gospel pour adopter le style soul) arriva le deuxième soir, Richard observa son succès. Il monta ensuite sur scène dans le noir et murmura des instructions à Preston. Tout en blanc, il surgit brusquement dans une poursuite et hurla Long Tall Sally. Son retour choc avait commencé et il fit un triomphe, comme si cinq années ne s’étaient pas écoulées. Vite engagé pour une autre tournée et une série de concerts à Hambourg en Allemagne en été, il emmena avec lui les jeunes Beatles (et les Stones quelques mois plus tard), dont le premier single « Love Me Do » venait de sortir avec succès. Richard devint ami avec eux et enseigna ses techniques vocales à Paul McCartney, qui l’idolâtrait. Les Upsetters avaient sorti un 45 tours instrumental chez Gee Records (Goldner) en 1960. Comme à l’aller il rentra en paquebot et enregistra aussitôt quatre titres de rock dont trois de Fats Domino. Il sortit ces morceaux peu connus sous le nom plus discret des World Famous Upsetters. La face B du deuxième single, un instrumental avec Richard au piano, annonçait ce qui allait venir : Freedom Ride.

Bruno Blum, juin 2014

Merci à Stéphane Colin, Christophe Hénault, Gilles Pétard et Patrick Renassia (Rock Paradise).

© FRÉMEAUX & ASSOCIÉS 2015

1. « Long Tall Sally est construite pour la vitesse/Elle a tout ce qu’il faut pour les besoins d’oncle John ».

2. Entretien avec Little Richard publié dans The Life and Times of Little Richard, The Quasar of Rock de Charles White (Harmony Books, New York City, 1984).

3. Lire le livret et écouter Great Black Music 1927-1962 (FA 5456) et Slavery in America – Redemption Songs 1914- 1972 (FA 5467) dans cette collection.

4. Lire le livret et écouter Gospel – Negro Spirituals/Gospel Songs 1926-1942 (FA 008) dans cette collection.

5. L’œuvre intégrale de Sister Rosetta Tharpe est disponible dans cette collection.

6. Lire le livret et écouter Roots of Soul 1928-1962 (FA 5430), où figure Little Richard, dans cette collection.

7. Lire le livret et écouter Race Records – Black Rock Music Forbidden on U.S. Radio 1942-1955 (FA 5600) à paraitre dans cette collection.

8. La meilleure version de Tutti Frutti par Slim and Slam est incluse sur notre volume 1 de Elvis Presley face à l’histoire de la musique américaine, 1954-1958 (FA 5361) au côté des versions de Little Richard et d’Elvis, qui l’enregistra en 1956.

9. Écouter « Rock the Joint » par Esquerita sur The Roots of Punk Rock Music 1926-1962 (FA 5415) dans cette collection.

10. Le meurtrier de Bud Penniman, Frank Tanner, a été acquitté faute de preuves le 18 octobre 1952. Leva Mae n’avait pas de quoi payer un avocat à charge. Vers 1962 Tanner vint demander pardon à la famille – et fut pardonné.

11. En Jamaïque, le non moins excentrique Lee « Scratch » Perry, lui aussi de petite taille et admirateur de Shirley and Lee comme de Little Richard, reprendrait en 1968 le nom The Upsetters, qu’il utilisa à son compte jusqu’en 1981.

12. « I’ve Got a Woman » de Ray Charles est un plagiat de « It Must Be Jesus », un gospel des Southern Tones inclus dans le coffret Roots of Soul 1928-1962 (FA 5430) — qui contient également le I’m Just a Lonely Guy de Little Richard — dans cette collection.

13. Lire le livret et écouter Roots of Punk Rock 1926-1962 (FA 5415) dans cette collection.

14. Lire le livret et écouter The Indispensable James Brown 1956-1961 (FA 5378) dans cette collection.

15. Écouter « Shout Bamalama » par Otis Redding en 1962 sur Roots of Soul 1928-1962 (FA 5430) dans cette collection.

16. Écouter les versions de Tutti Frutti par Slim and Slam, Little Richard et Elvis Presley juxtaposées sur Elvis Presley face à l’histoire de la musique américaine 1954-1956 (FA 5361) dans cette collection.

17. Les musiques afro-américaines regorgeaient alors de double sens salaces. En anglais « John » est un terme d’argot signifiant les attributs masculins. À la lumière de ses fantasmes habituels, racontés par Little Richard lui-même, cette phrase pourrait donc être comprise ainsi : « J’ai vu « oncle John » parler à la grande Sally/Elle m’a vu « venir » et il est sorti de « l’allée » en marche arrière ».

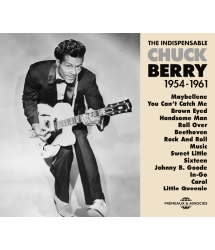

18. Lire le livret et écouter The Indispensable Bo Diddley 1955-1960 (FA 5376) et 1959-1962 (FA 5406) ainsi que The Indispensable Chuck Berry 1955-1961 (FA 5409) dans cette collection.

19. Charles White, ibid, p. 77.

20. « Rockin’ with Red » est inclus dans Race Records – Black Rock Music Forbidden on U.S. Radio 1942-1955 (FA 5600) à paraitre dans cette collection.

21. Écouter Keep a Knockin’ par Milton Brown sur Rock n’ Roll 1927-1938 (FA 351) et celle d’Adolf Hofner dans Hillbilly Blues 1928-1946 (FA 065) dans cette collection.

22. Lire le livret et écouter le coffret The Indispensable Bill Haley 1948-1962 (FA 5465) dans cette collection.

23. Lire le livret et écouter Elvis Presley face à l’histoire de la musique américaine 1954-1956 (FA 5361) et 1956-1957 (FA 5383) dans cette collection.

24. Lire le livret et écouter The Indispensable Gene Vincent 1956-1958 (FA 5402) et 1958-1962 (FA 5422) dans cette collection.

25. Lire le livret et écouter The Indispensable Jerry Lee Lewis 1956-1962 à paraitre dans cette collection.

26. Lire le livret et écouter The Indispensable Buddy Holly 1956-1959 à paraitre dans cette collection.

27. Lire le livret et écouter The Indispensable Eddie Cochran 1955-1960 (FA 5425) dans cette collection.

28. Little Richard deviendra toxicomane dans les années 1960.

29. « Dieu dit : Voici, je vous donne toute herbe portant semence à la surface de toute la terre et tout arbre ayant en lui le fruit d’arbre portant semence : ce sera votre nourriture ». La Bible, Génèse 1:29.

The Indispensable Little Richard 1951-1962

By Bruno Blum

Long tall Sally she’s built for speed/She’s got everything Uncle John needs.

Richard Wayne Penniman was born in Macon, Georgia on December 5th 1932. He was the third of twelve children born to parents who also came from large families. His mother Leva Mae Stuart, a woman of character, was relatively light-skinned; her parents were cultured and well-to-do (“I think they had Indian blood1”), and her brother Louis was a Baptist minister. She was only fourteen when she married Charles “Bud” Penniman, a mason whose father Walter was also a preacher. In some counties, alcohol was banned (and it still is); its sale and consumption were forbidden in Georgia, but Bud used to sell “moonshine” whiskey. The middle-class Pennimans lived in harmony. Richard was a big, strong baby with a strong personality and he grew to be a very turbulent child, always quick to step out of line or play cruel tricks, and he lied to try to escape a (frequent) strapping when he was punished. He liked to provoke and shock people, especially adults. His head was large in proportion (he was called “big head” in school) and one of his legs was too short. His schoolmates made fun of his limp and quickly deemed his affected gait to be effeminate. He didn’t grow tall and disliked playing with other boys, preferring the company of girls. Most of his friends were girls.

Negro Spirituals

As everywhere in the South, the racial segregation in Macon vibrated to the sounds of freedom songs, both

religious and secular.2 Workers, children, housewives... everyone sang spirituals like “Motherless Child” or “Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen” which were picked up in chorus by the whole street.3 Solidarity was widespread, and Richard’s father wasn’t denounced or arrested because of his home-distillery. Ladies at the church took care of Richard and his brothers when they became part of the Tiny Tots children’s choir, and the boys would often join the elder women singing spirituals, stamping in rhythm with fervour. While he was still very young he went by car to sing “Peace in the Valley” or “Precious Lord” at religious gatherings at camp meetings and Protestant churches. Richard behaved when he was with this second family who taught him to play piano and sing.

The man who produced his hits, Bumps Blackwell, would describe Richard as being incapable of making a decision and sticking to it. As a child, the singer already wavered between behaving like a rascal and being a good boy and pious student. In 1959 he would go back to his congregation to record the gospel song Coming Home. At ten he posed as a healer who cured by singing. At twelve (1945) he was hired as a drinks-vendor at Macon Auditorium, and it allowed him to see Cab Calloway, Hot Lips Page, Cootie Williams or Lucky Millinder onstage, as well as his idol, the gospel singer-guitarist Sister Rosetta Tharpe4. He sang two of her hits for her in the wings; the great star invited him to sing them onstage and gave him forty dollars, a huge sum; the event left a lasting impression on him.

He was a poor student but quickly mastered the alto saxophone and joined his school band; he was attracted to boys and felt different. He was quite young when he lost his virginity to an elder girl, and that first sexual relationship was followed by performing oral sex on a paedophile who bought favours from young adolescents. Richard was catalogued a sissy and hung around with two homosexuals of his own age, often propositioned by white adults and chased and harassed by their comrades. Richard liked bad jokes and his brother had to fight to protect him from other boys. He terrorized his teachers and liked to be noticed, screaming when he sang in public or else banging on pans in the staircase as accompaniment. He belonged to the family gospel group The Penniman Singers, but was permanently in trouble: he tended to sing too loud and too high. He and his mother attended the New Hope Baptist Church on Third Avenue, and his father the African Methodist Episcopal Church on Madison Street. Richard, however, preferred the exuberance and intense music of the Pentecostal Church services5. He and his friends would laughingly mimic the “speaking in tongues” vocal improvisations of the faithful there. His cousin Amos Penniman was a Pentecostal pastor and young Richard’s idol was Brother Joe May, a singing evangelist known as “The Thunderbolt of the West”. Richard dreamed of becoming a minister in turn, and when he was twenty-five, after a flashing career as a rock singer, this is what he would try to do.

Tent Queen Shows

His father was critical of his effeminate manners and the way he walked; Richard was a dunce and free spirit who felt rejected by his family, and he took up company with street vendors and charlatans selling elixirs at sideshows where he used to sing to draw more customers. At fourteen he joined the Dr. Hudson Medicine Show, whose superstitious patrons bought its “snake oil” cure [snakes were symbols used in the animist “voodoo” religion which Christians considered evil.] Accompanied by a pianist, Richard used to sing Louis Jordan’s “Caledonia”, his first non-religious piece. At night he slept in the open air. Taken in by Ethel Wynnes, who owned the Winsetta Patio club on East Pine Street, Richard stood in for the singer with B. Brown & his Orchestra. In 1947 he toured with them all the way through Georgia singing ballads like “Goodnight Irene”, a folk standard. Calling himself “Little Richard” for the first time (it was painted on the group’s covered truck), the singer already had his Pompadour hairstyle and he was a hit when he sang in Macon; his family were there, and although his father accepted his new career, his mother thought he was too young to go off alone. Little Richard joined another troupe whose members were even younger, the Sugarfoot Sam Minstrel Show, a vaudeville show where he played a role dressed as a woman. He then joined the King Brothers Circus, and next the Tidy Jolly Steppers, where he also sang wearing women’s clothes. He did the same with another minstrel troupe, the L. J. Heath Show, joining other transvestites wearing make-up and false eyelashes. He became more and more involved with the homosexual milieu, and was hired for the Broadway Follies, again a show featuring transvestites. Every week he sang in Georgia’s huge capital, Atlanta, where rhythm and blues enjoyed a golden age; Atlanta was very influential thanks to many clubs like those in the Auburn Avenue district, some of which were regular meeting-places for homosexuals.

With the end of the Forties came the birth of seminal rock and roll and, because of racial segregation, it was restricted to black audiences.6 Little Richard appeared on the same show as Chuck Willis; under the direction of the comedian called Snake, the Broadway Follies troupe shared bills with B. B. King, Jimmy Witherspoon and other stars of the region. It was in Atlanta that Little Richard met Billy Wright, “The Prince of the Blues”, a blues-shouter whose songs had a strong gospel influence. Billy was a snappy dresser and he had a decisive influence on the adolescent Richard. He was also a homosexual and his hits in the “jump blues” style—rock with swing-like brass riffs, like Get Rich Quick here—had impact in 1949-1951. Little Richard even adopted Billy’s foundation-cream (the ‘Pancake 31’ brand), and an outrageous Pompadour haircut perched on top of his skull. Billy Wright was a familiar figure at “tent queen shows”—a southern U.S. club-tradition which originally began under canvas—where people could hear ribald songs like “Don’t You Want a Man Like Me” (“Confessin’ the Blues” by Jay McShann), which Little Richard sang marvellously (his audience cried with laughter). From Billy he also borrowed “Busy Bootin’” (a parody of the Keep a Knockin’ standard) and his future first hit (here before the lyrics were changed) which parodied a Slim & Slam7 title: Tutti Frutti / Good bootie / If it don’t fit / don’t force it / Just grease it / Make it easy.

Billy Wright introduced Little Richard to one of the first white disc-jockeys to play black music, Zenas Sears. Thanks to Sears, who’d obtained the necessary funds from RCA Records, it was on Radio WGST in Macon that Little Richard recorded his first tunes (with Billy Wright’s musicians). A local hit thanks to airplay from Zenas Sears, Every Hour has the stamp of his mentor, and it was even Billy Wright himself who, at the request of Savoy producer Lee Magid, plagiarized the piece under the title “Ev’ry Evenin’” and had a real hit with it. Several other songs were cut for RCA by Little Richard. His father was delighted at the welcome given to this first record, and at the suggestion of their manager Horace Edwards, he gave permission for Richard to join the band led by bassist Percy Welch. With them, Little Richard would sing the “transvestite standard” entitled “Don’t You Want a Man Like Me” all the way to Kentucky and Tennessee.

The Greyhound Bus company had a waiting-room at the bus-station in Macon, the only place in the city that remained open all night (and also a favourite pick-up place); it was there that Little Richard met jazz pianist Esquerita. The latter was accompanying Sister Rosa, a gospel singer who sold blessed bread. Like Richard, Esquerita was marked by Tent Queen shows8, he also had a Pompadour and dressed like an eccentric. He fell under Richard’s spell and taught him to play piano. In 1958 he would record an album that was highly influenced by Richard, who would make another record in 1952 (only Richard’s best recordings for RCA are included here).

A month later, Richard’s father was shot to death in a stupid quarrel; he and Richard had become reconciled, and he was due to buy his son an automobile.9 Leva Mae was pregnant and the family was immediately plunged into misery. Richard’s brother was away fighting in the Korean War and the singer was washing dishes at the Greyhound bus station to help feed the family. Now managed by Clint Brantley, he formed the Tempo Toppers with the Taylor brothers, and they spent a long time in New Orleans playing at the Tijuana Club where Richard became friends with singer-guitarist Earl King. But it was in Houston that he would meet the bandleader Johnny Otis. Otis spotted Richard while having lunch at the Matinee Club, where the singer was giving an exuberant, provocative, erotic and flamboyant show: at the end of the performance, Richard styled himself as “the King of the Blues”, adding, “and also the Queen!” Peacock Records had him record for them but the songs didn’t reflect Little Richard’s eccentric aura and they weren’t hits. After an argument over money, Peacock’s boss Don Robey gave Richard a beating. At the end of 1953, Little Richard pursued a solo career, working with guitarist Thomas Hartwell.

The Upsetters

The singer began to tire of gospel’s influence and wanted to turn more to rock ‘n’ roll, an energetic style that pleased concert audiences and had revealed black artists like Jackie Brenston and his Delta Cats (“Rocket 88” and “My Real Gone Rocket”, 1951) or Wally Mercer (“Rock Around the Clock”, 1952). Richard crossed paths with two of his old New Orleans buddies who were accompanying Shirley & Lee (drummer Chuck Connor, one of the best around, and pianist/saxophonist Wilbert Smith) and together they became Little Richard’s new group, The Upsetters. He added two saxophones and took them on tour, and they were a hit,10 playing repertoire that drew from the edgier compositions of B. B. King, Little Walter and Fats Domino — and two of rock ‘n’ roll’s authentic founding-fathers (the song “Keep Your Hand on Your Heart” by Billy Wright, and Roy Brown). Their great hit, however, was their parody of Tutti Frutti.

Specialty

“Lawdy Miss Clawdy” was one of the biggest black hits of the period. Singer Lloyd Price was playing one night at Macon Auditorium and suggested to Little Richard that he might send a recording to Art Rupe, who ran Specialty Records in Los Angeles. Recorded in February 1955 at radio WBML in Macon, the demo of Wonderin’ had in fact been plagiarized from a “friend”. “He’s my Star” was another blues marked by gospel, but Art Rupe didn’t react. By then, Richard was organizing triangular sexual encounters in which he was a voyeur. He used to take his girlfriend Fanny out in the car and ask her to seduce men; Richard would then take the partners to a quiet spot and watch them make love while he masturbated. Denounced to the police by a gas-station attendant who spied on them from a parking-lot, Richard was arrested and spent several days in gaol for indecent behaviour. The attorney sent by his mother obtained his release but Richard was banished from Macon — the city of his childhood, and all of his family — and decided to devote himself to the stage, travelling all over the South while building a new repertoire in the course of 1955. In September he was finally contacted by Specialty Records: house-producer Bumps Blackwell offered him a studio-session in New Orleans. Blackwell was black, but he had been schooled at Los Angeles University in the white tradition of musical composition, and in the late 40’s he’d led a jazz orchestra whose musicians included the young Ray Charles and Quincy Jones. Hired by Art Rupe in 1949, Bumps Blackwell was the fine musician who spotted Richard’s demo, leading to his first recordings for Specialty in New Orleans at the legendary studio owned by Cosimo Matassa. In the context of racial segregation, the black public often took little interest in white artists, especially when they were increasingly copying the style and ideas of black artists… The market for Afro-American music was supplied by independent labels like Specialty, which was founded in Hollywood in 1944 by Art Rupe (real name Goldberg), a (white) Jewish businessman who’d fallen in love with gospel music after hearing it in his neighbourhood Baptist church in Pittsburgh.

Specialty was already one of the first and best of these new “black” labels. In the tradition of Jewish jazz producers like Alfred Lion (Blue Note) before him, Rupe catered to demand by producing fashionable black music and launched Sam Cooke and Lloyd Price among others. In 1955, every producer was looking for artists who could reproduce Ray Charles’ “I’ve Got a Woman” formula: secular rock impregnated with gospel song.11 Little Richard liked the New Orleans sound and it was there, at Cosimo Matassa’s studio where Fats Domino and Lloyd Price worked, that Bumps Blackwell gave him an appointment. Once his contract had been acquired from Peacock, they recorded a few blues with the best local musicians, most notably the drum-giant Earl Palmer. But Blackwell knew that the slow numbers they recorded there wouldn’t be hits.

Tutti Frutti

During their lunch-break the next day, Little Richard sat down at the piano at the Dew Drop Inn to demonstrate his style to saxophonist Lee Allen. Suddenly exposed to the young Dew Drop audience, he screamed “womp-bop-aloo-momp-alop-bomp-bomp” and launched into the sexually-explicit parody-version of Tutti Frutti inherited from Billy Wright. Bumps knew at once that he had a monster hit on his hands, and Dorothy LaBostrie rewrote the lyrics there and then. Richard played piano himself and in three improvised takes, Tutti Frutti was finished. In the same afternoon he’d recorded one soul masterpiece (I’m Just a Lonely Guy) and one rock masterpiece. After the calm “I’ve Got a Woman”, Chuck Berry’s “Maybellene” was the first truly “rock” hit with a mass audience. On WLAC in Tennessee, Gene Nobles was one of the very first disc-jockeys to air black music; in October 1955 he announced that Tutti Frutti was a country-wide hit (limited to the black market). Elvis Presley hadn’t yet signed with RCA, and Bill Haley had been all the rage since the summer with “Rock Around the Clock”. The rock wave was gaining strength.

Tutti Frutti came at the right time. It was more radical, more exciting with that possessed, inhabited voice; it was powerful and electric, a long way from the placid Fats Domino or the elegant Ray Charles: this time the piece was carried by pure energy.12 The sustained rhythm, Earl Palmer’s swing, the piano style and especially the screams from the crazy voice of Little Richard… the tradition of parody inherited from transvestite shows in the South had given birth to a magic formula. Richard suddenly refused to honour a series of bookings, and was replaced by a beginner named James Brown who was introduced onstage as Little Richard. Brown would go on to record Chonnie-Chon-Chon in the rock style of Richard13, and would soon be replaced by Otis Redding, another copycat-beginner who idolized Richard.14 The new star was at once invited to Los Angeles by Specialty; he arrived with his hair styled at least eight inches high, and his colourful clothes, affected manner and thundering, vain declarations made everyone sit up and take notice. His conspicuous sexual preferences also left an impression. Many groups put “Tutti Frutti” into their repertoire; the vapid Pat Boone quickly recorded it (successfully) and Elvis recorded it a few days later in January 1956. RCA rush-released the latter—right in the middle of Elvismania—and despite it being an inferior version it still had major impact.15

Have some fun tonight

Artists didn’t earn much from records, especially if they were black artists (a half-cent for each 45rpm), and Little Richard took to the road with the Upsetters to capitalize on his success. With Cherie Landry as manager and Henry Nash as road-manager, and backed by excellent musicians, they rehearsed an unbeatable show. Blackwell was contacted by a DJ who introduced Enortis Johnson to him. She was a teenage girl from Opelousas, Louisiana, and she’d written the unintelligible words for what would soon become Long Tall Sally, complete with sulphurous, double-entendre lyrics: “I saw Uncle John talking to ‘Long Tall Sally.’ She saw me comin’ and he ducked back in the alley.”16 After hesitating, Richard added the hook, “Have some fun tonight”, and it became his second single, an instant N°1 in the R&B sales charts.

An insipid Pat Boone-version of it sold over a million copies. Richard consequently bought a fine house of several storeys for his mother, complete with marble floors, statues and a garden, and she moved in with the whole family at 1710 Virginia Road, a wealthy area of Los Angeles. One of the Pennimans’ neighbours was world boxing-champion Joe Louis. They’d never seen Blacks living in such opulence. Richard bought a gold-coloured Cadillac. According to him, it was the happiest period in his life. He produced one hit after another. Rip It Up came out in June and went to N°1. Elvis Presley, Buddy Holly and Bill Haley recorded it also. Richard’s tele-vision appearances, concerts and discs contributed to push back racial taboos.17 In a country where a black man seducing a white woman risked being murdered, Little Richard sought protection by behaving outrageously: it made him seem just an inoffensive buffoon, and he would go onstage disguised as the Queen of England or Pope Pius XII.

But onstage Little Richard flashed like a quasar and knew no limits. With his hair plastered to his face in sweat, he danced and shook his head around, urging audiences to set themselves free; and all this at a time when concerts were usually polite, staid affairs. Little Richard and the Upsetters washed over America like a tidal wave. Blacks and Whites mingled and danced. No venue was big enough for them. If Elvis was at his peak and content just to sing new versions of his old songs, Little Richard composed new ones without a break, and nothing seemed to stop him: wearing thick make-up and diamond-studded suits in flashing colours, he climbed onto his piano, ripped his clothes off onstage, jumped into the audience, all the time screaming and dancing his music wildly… nobody had ever seen anything like it. Elvis Presley caused a scandal but Little Richard did ten times as much. In Baltimore, panties and other underwear rained down on Richard and his band. Concerts had to be interrupted to prevent hysterical girls from ripping his clothes from his body as souvenirs. In El Paso, Texas, he was imprisoned because he’d dared to wear his hair long, but generally there was little serious trouble. Worshipped by the public (white in their great majority), Little Richard and his musicians were hunted down by young women to the point where they began organizing orgies with them. As was his habit, Richard would masturbate while watching these scenes. “I used to like to watch these people having sex with my band men. I would pay a guy who had a big penis to come and have sex with these ladies so I could watch them. It was a big thrill to me […] As I was watching, I would masturbate while someone was eating my titties […] I hated myself, I didn’t want to talk about it or answer any questions. I asked myself, ‘Why are you doing this? Are you insane?’ Most gays fall in love with themselves.”18 Then he met Angel (he renamed her Lee Angel), a slim black beauty who was barely seventeen, with full breasts and a white woman’s features. She would do anything to please him, which included having sex with four different men at the same time in front of Little Richard, who was masturbating as usual while Angel licked his nipples. She was a dancer, stripper and nude model, and they became inseparable. Sex became their main activity when they weren’t onstage (Richard would tell of an orgy involving Buddy Holly). Preferring to record with the Upsetters, Richard led several sessions in Los Angeles before giving in to Blackwell’s demands (he preferred the formula with Earl Palmer). Lucille was a giant hit. Based on the accelerated riff from his blues Directly From my Heart, the song is about a transvestite named Queen Sonya who is rechristened Lucille. As for Good Golly Miss Molly, Richard had heard DJ Jimmy Pennick use the expression. The guitar riff was borrowed from Jackie Brenston’s “Rocket 88”. She Knows How to Rock is derived from “Rockin’ with Red” by Piano Red (1950)19. The supercharged Keep a Knockin’ had been recorded by numerous white blues artists including Milton Brown and Adolf Hofner.20 Despite those borrowings, Richard’s style was inimitable. The greatest stars in white rock were recording his songs — among them Bill Haley21, Elvis Presley22 (4 titles), Carl Perkins, Gene Vincent23, Jerry Lee Lewis24 (who also copied his piano style), Buddy Holly25, the Everly Brothers, Pat Boone and Eddie Cochran26 — but no version ever surpassed his own.

The Girl Can’t Help It

Following the success of Richard Brooks’ film Blackboard Jungle (released March 1955) which launched Bill Haley’s “Rock Around the Clock” and created the rock craze among the white public, its producer Sam Katzman produced a new rock film called Don’t Knock the Rock (Alan Dale, 1956). In it, Little Richard sang Tutti Frutti and Long Tall Sally which caused a fresh wind of freedom to blow, inspiring a whole generation. But it was in Frank Tashlin’s The Girl Can’t Help It (December 1956), the best film in the rock genre, that Little Richard was the most visible: three songs (She’s Got It — a remake of I Got It —, The Girl Can’t Help It and Ready Teddy) alongside sex symbol Jayne Mansfield, and regal appearances by Julie London, Abbey Lincoln, Gene Vincent, Fats Domino, Eddie Cochran, the Platters, Treniers and others. The song The Girl Can’t Help It (different from the film version) and the film itself were enormous hits. Little Richard was now an international star. She’s Got It, Send Me Some Lovin’, Miss Ann, Jenny Jenny, Keep a Knockin’ and others were all new hits. Little Richard was earning ten to fifteen thousand dollars every night from his concerts alone. A valise full of cash accompanied him everywhere, and the trunk of his Cadillac was packed with banknotes which he distributed in handfuls to everyone he liked. His triumph knew no bounds.

King of Gospel

Although he never drank a drop of alcohol (he preferred coffee),27 his androgynous sex-charged image—denounced as the work of the devil by God-fearing folk in times when rock was scandalous—was in contradiction with the religion in which he had grown up. Not to mention the orgies which, by Richard’s own admission, had become a terrible addiction. One day there was a knock on his door from Brother Wilbur Galley, a missionary of the United Church of God and the Ten Commandments. He was seeking to convert the neighbourhood stars to Christianity, and his flowery phrases were convincing. Richard welcomed him with open arms. Galley introduced him to Joe Lutcher, a rock-singer/sax-player whose “Rockin’ Boogie” (1947) produced by Art Rupe had been one of Specialty’s first hits. Lutcher had quit show business and become a Seventh Day Adventist preacher. Little Richard was being hounded by the Inland Revenue; highly controversial, routinely harassed, he was exhausted after endless tours, and also under constant threat from racist organizations who hated rock and roll… on the point of cracking up, Richard was ready. He’d already shown this more than once by reading the Bible to his entourage.

At the end of September 1957 he flew off to undertake an Australian tour with Gene Vincent, Eddie Cochran and Alis Lesley. Richard was scared of flying and had never left America before. Over the Pacific he thought his plane was on fire, and after landing he said he owed his life to the angels who’d been carrying him. Five concerts later (October 11th 1957) he recorded a radio show (both of these super-active tunes are included here) and was singing for some 40,000 people in an outdoor arena in Sydney when he noticed, right in the middle of the show, a ball of fire in the sky. He thought it was a UFO. [Later, he supposed it was the Russian rocket which launched Sputnik I, the first artificial satellite in history, but that one had already been placed in orbit on October 4th.] Onstage, Richard thought it was a sign from God; he left his piano in mid-song and walked offstage without warning. He’d made his decision: he was going to drop everything, go home, and devote his life to God. The rest of the troupe, speechless, flew to Los Angeles the next morning, saying goodbye to half a million dollars in fees, a genuine fortune in 1957. According to Richard, the plane they were all due to have taken (to return from Australia after the tour) crashed into the sea, and he took that as another sign from God. He refused to honour his next fifty concerts (for which he’d already signed and received part-payment) and accepted just one farewell concert at the Apollo Theatre in New York as a gesture to his friend, DJ Alan Freed. To the huge dismay of millions of fans, Little Richard went off to join Lutcher, the Adventists, and a new way of life.

Compared with many other American religious movements, the Adventists were rather liberal and progressive. They encouraged a healthy vegan diet known for its refinement and quality. The singer later said that the diet was the reason for his exceptional energy and longevity.28 Lutcher and Little Richard put together the Little Richard Evangelist Team and crossed the country on a mission to help the poor in difficulty. Richard served at tent shows, washed members’ feet before communion, kept generally busy, and prayed all the time. He went to Oakwood College in Alabama for a three year course to train as a minister. Angel disappeared. In November he met Ernestine Campbell, a teenage secretary who was barely out of school; she’d joined the U.S. Navy where her whole family worked. They married in July 1959. Often absent, and much in demand, Richard was totally absorbed by his religious activities. He recorded five gospels with an anonymous congregation (the records appeared on the labels End, Roulette and Goldisc) under the aegis of George Goldner, Frankie Lymon’s producer. Goldner released two albums under Little Richard’s name, but Richard’s voice only features on the five titles included here. At Oakwood College the charismatic Richard liked the teaching but was a poor student, and always arrived late; he would drive up in his yellow Cadillac, and other students would beg him to sing some rock for them. In a word, he was a disruptive element. His homosexuality was revealed after an adventure with another student; he was furious at being unmasked and felt guilty of being a liar. He abruptly left the institute. Specialty continued to publish previously-unreleased recordings from 1956-57, and then Bumps Blackwell, now a producer at Mercury, proposed a gospel album featuring Richard with the celebrated arranger Quincy Jones. Richard’s voice is present only on two titles from that King of Gospel album released under his own name: he turned up ten hours late for the session—forty musicians were waiting for him—only to calmly announce that “The Lord didn’t want me to record today.” There were also concerts at this time, with his friend Mahalia Jackson, and he recorded Crying in the Chapel for Atlantic, a 45rpm single which was a tribute to his wife Ernestine. Their marriage failed.

Comeback

Then promoter Don Arden suddenly offered him a tour in England, sharing the bill with Sam Cooke and Gene Vincent. Little Richard was billed everywhere as a rock singer, but he thought he’d been hired to sing gospels. Which he did at the first concert (with a sixteen-year old Billy Preston playing organ); it was a disaster for the disappointed English audience. But on the second night, when Sam Cooke came on—he’d abandoned his brilliant gospel career in favour of a soul style—Richard could see he was a hit with the crowd. When Cooke concluded, Richard whispered a few instructions to Preston before going up onstage in the dark. He had a white suit on, and sprang into the spotlight screaming Long Tall Sally. His thundering comeback was a triumph: it was as if he’d never been away, even after five years. He was quickly booked to do another tour and a series of concerts in Hamburg that summer. With him he took the young Beatles (and also the Stones a few months later). The Beatles’ first single “Love Me Do” had just been released with success. Richard and the Beatles became friends, and Richard gave some lessons in vocal technique to Paul McCartney, who idolized him. The Upsetters had released an instrumental 45rpm on Gee Records (“G” as in Goldner) in 1960. As on the outward voyage, Richard went home by steamer and immediately recorded four rock titles, three of them by Fats Domino. He released those little-known pieces under the more discreet name of The World Famous Upsetters. The B side of the second single, an instrumental with Little Richard on piano, heralded what was to come: Freedom Ride.

Bruno Blum, June 2014

English adaptation: Martin DAVIES

Thanks to Stéphane Colin, Christophe Hénault, Gilles Pétard and Patrick Renassia (Rock Paradise).

© FRÉMEAUX & ASSOCIÉS 2015

1. Little Richard, interview published in The Life and Times of Little Richard, The Quasar of Rock, Charles White, Harmony Books, New York City, 1984.

2. Cf. Great Black Music 1927-1962 (FA 5456) and Slavery in America – Redemption Songs 1914- 1972 (FA 5467)

3. Cf. Gospel – Negro Spirituals/Gospel Songs 1926-1942 (FA 008).

4. The complete works of Sister Rosetta Tharpe are available in this collection.

5. Cf. Roots of Soul 1928-1962 (FA 5430), in which Little Richard is also featured.

6. Cf. Race Records – Black Rock Music Forbidden on U.S. Radio 1942-1955 (FA 5600) in this series.

7. The best Slim & Slam version of Tutti Frutti can be heard on Vol.1 of Elvis Presley & the American Music Heritage, 1954-1958 (FA 5361), alongside a version by Little Richard and one by Elvis, who recorded it in 1956.

8. Cf. “Rock the Joint” by Esquerita on The Roots of Punk Rock Music 1926-1962 (FA 5415).

9. Bud Penniman’s killer, Frank Tanner, was acquitted for lack of evidence on 18th October 1952. Leva Mae couldn’t afford a prosecution lawyer. In around 1962 Tanner would ask for the family’s pardon – and was forgiven.

10. In Jamaica, the no-less eccentric Lee “Scratch” Perry, also slightly-built and an admirer of Shirley & Lee and Little Richard, began using the name The Upsetters in 1968, keeping it until 1981.

11. Ray Charles’ “I’ve Got a Woman” was plagiarism; it was based on the Southern Tones’ gospel song “It Must Be Jesus” included in the set Roots of Soul 1928-1962 (FA 5430) which also contains I’m Just a Lonely Guy by Little Richard.

12. Cf. Roots of Punk Rock 1926-1962 (FA 5415).

13. Cf. The Indispensable James Brown 1956-1961 (FA 5378).

14. Listen to “Shout Bamalama” by Otis Redding in 1962 in Roots of Soul 1928-1962 (FA 5430).

15. Listen to the versions of Tutti Frutti by Slim and Slam, Little Richard and Elvis Presley one alongside the other in Elvis Presley face à l’histoire de la musique américaine 1954-1956 (FA 5361).

16. Afro-American music is full of lewd double-entendres like “John”, a slang term for the male organ. Given Little Richard’s habitual fantasies, this whole phrase takes on new meaning.

17. Cf. The Indispensable Bo Diddley 1955-1960 (FA 5376) and 1959-1962 (FA 5406), plus The Indispensable Chuck Berry 1955-1961 (FA 5409).

18. Charles White, ibid, p. 77.

19. “Rockin’ with Red” is included in Race Records – Black Rock Music Forbidden on U.S. Radio 1942-1955 (FA5600) in this series.