- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

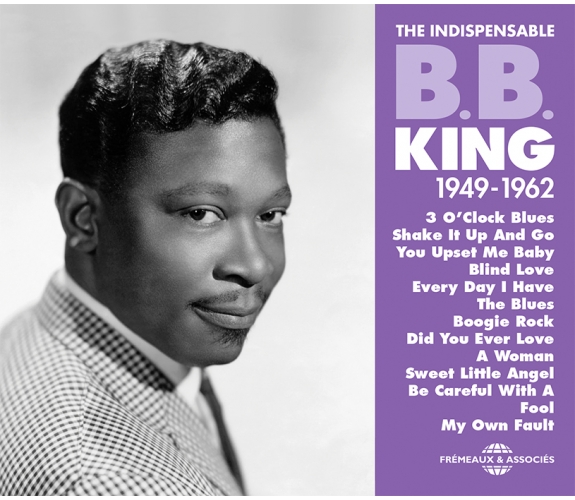

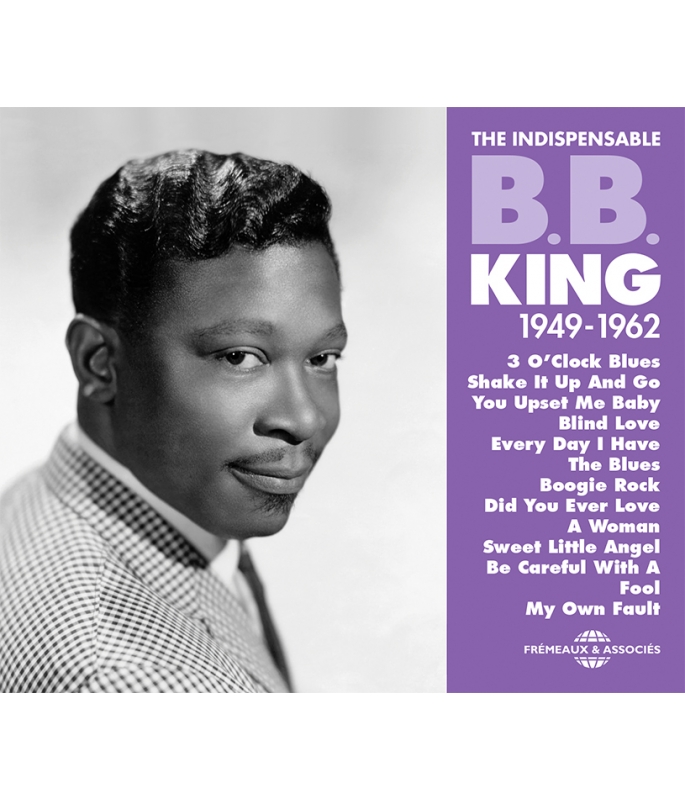

THE INDISPENSABLE 1949-1962

B.B. KING

Ref.: FA5414

Artistic Direction : BRUNO BLUM

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Total duration of the pack : 3 hours 17 minutes

Nbre. CD : 3

THE INDISPENSABLE 1949-1962

THE INDISPENSABLE 1949-1962

With his great Soul voice and elegant guitar, B.B. King is the musician who deserves most credit for making the world discover the Blues. This anthology compiled by Bruno Blum includes the best titles from the guitarist’s most authentic period, the years in which he imposed his influential, highly personal style to become a King of the Blues. Patrick FRÉMEAUX

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Miss Martha KingBB KingBB King00:02:441949

-

2Take A Swing With MeBB KingBB King00:02:371949

-

3Mistreated WomanBB KingBB King00:02:501950

-

4BB BoogieBB KingBB King00:03:131950

-

5The Other Night BluesBB KingBB King00:03:411950

-

6Walkin' And Cryin'BB KingBB King00:03:301950

-

7My Baby's GoneBB KingBB King00:02:011951

-

8Don't You Want A Man Like MeBB KingBB King00:02:211951

-

9Questionnaire BluesBB KingBB King00:03:001951

-

10BB BluesBB KingBB King00:02:291951

-

11A New Way Of DrivingBB KingBB King00:01:571951

-

12She's A DynamiteBB KingHudson Woodbridge00:02:311951

-

13She's A Mean WomanBB KingBB King00:02:351951

-

14Hard Workin' WomanBB KingBB King00:02:361951

-

15Pray For YouBB KingBB King00:02:331951

-

16Three O' Clock BluesBB KingL. Fulson00:03:081951

-

17That Ain't The Way To Do ItBB KingInconnu00:02:251951

-

18She Don't Move Me No MoreBB KingBB King00:03:101951

-

19Shake It Up And GoBB KingBB King00:02:371952

-

20It's My Own FaultBB KingBB King00:03:301951

-

21Gotta Find My BabyBB KingBB King00:02:271952

-

22Low Down Dirty BabyBB KingBB King00:03:071952

-

23Someday SomewhereBB KingBB King00:02:521952

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Blind LoveBB KingBB King00:03:051952

-

2Everything I Do Is WrongBB KingBB King00:02:291954

-

3You Didn't Want MeBB KingBB King00:02:341952

-

4You Know I Love YouBB KingBB King00:03:061952

-

5Boogie Woogie WomanBB KingBB King00:02:531952

-

6Woke Up This MorningBB KingBB King00:02:581952

-

7Don'T Have To CryBB KingBB King00:03:171952

-

8Please Love MeBB KingBB King00:02:521952

-

9Highway BoundBB KingBB King00:02:471952

-

10Bye Bye BabyBB KingBB King00:02:321952

-

11Can't We Talk It OverBB KingBB King00:03:241952

-

12Please Hurry HomeBB KingBB King00:02:441953

-

13Praying To The LordBB KingBB King00:02:551953

-

14Why Did You Leave MeBB KingBB King00:03:111953

-

15Please Help MeBB KingBB King00:03:171953

-

16Please Remember MeBB KingBB King00:03:171953

-

17The Woman I LoveBB KingPeter Joe Clayton00:02:421954

-

18When My Heart Beats Like A HammerBB KingJ.L. Williamson00:02:561954

-

19Every Day I Have The BluesBB KingP. Chatman00:02:501954

-

20Ten Long YearsBB KingBB King00:02:491955

-

21Boogie RockBB KingHudson Whittaker00:03:021955

-

22Crying Won't Help YouBB KingHudson Whittaker00:03:001955

-

23Bad LuckBB KingJoe Hunter Ivory00:02:531955

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1You Upset Me BabyBB KingBB King00:03:041955

-

2Did You Ever Love A WomanBB KingArnold Dwight Moore00:02:341955

-

3Sweet Little AngelBB KingHudson Whittaker00:03:021956

-

4You Don't KnowBB KingWalter Springs00:02:261956

-

5I Stay In The MoodBB KingBB King00:02:331956

-

6Be Careful With A FoolBB KingBB King00:02:521956

-

7On My Word Of HonorBB KingSamuel Ram00:02:561956

-

8Days Of OldBB KingBB King00:02:291958

-

9Worry, WorryBB KingJeremiah Bihari00:02:431958

-

10Please Accept My LoveBB KingClarence J. Garlow00:02:341958

-

11Sweet SixteenBB KingAhmet Ertegun00:06:141959

-

12Bad LuckBB KingBB King00:02:191956

-

13Hold That TrainBB KingBB King00:03:581960

-

14Walkin Dr BillBB KingPeter J. Clayton00:03:411960

-

15It's My Own FaultBB KingBB King00:03:341960

-

16You Done Lost Your Good Thing NowBB KingBB King00:05:151960

-

17DownheartedBB KingBB King00:03:141962

-

18I Will SurviveBB KingBB King00:02:421960

-

19Peace Of MindBB KingBB King00:02:181961

-

20Going Down SlowBB KingJames B. Oden00:02:531962

-

21Down NowBB KingBB King00:03:021961

BB KIng FA5414

THE INDISPENSABLE

B.B. KING

1949-1962

Avec une voix «?soul?» et un jeu de guitare raffiné, B.B. King a été le principal musicien américain à faire découvrir le blues dans le monde entier. Cette anthologie dirigée par Bruno Blum réunit les meilleurs titres de sa période la plus authentique pendant laquelle, en imposant son style influent et très personnel, il a obtenu son titre de roi du blues.

Patrick Frémeaux

With his great Soul voice and elegant guitar, B.B. King is the musician who deserves most credit for making the world discover the Blues. This anthology compiled by Bruno Blum includes the best titles from the guitarist’s most authentic period, the years in which he imposed his influential, highly personal style to become a King of the Blues.

Patrick Frémeaux

B.B. King

The Indispensable 1949-1962

par Bruno Blum

The Indispensable B.B. King

B.B. King est le musicien qui a le plus largement fait découvrir le blues au grand public américain. C’est son style issu d’une longue tradition, combiné à un chant de rocker «shouter?» où de rapides phrases de guitare prolongent et ornent ses vers chantés, qui a conquis l’Amérique et le monde. En dépit de la ségrégation raciale toujours en vigueur au milieu des années 1960, il a su profiter de l’intérêt pour le blues suscité aux États-Unis par le succès de musiciens anglais blancs comme les Rolling Stones, les Animals, John Mayall and the Bluesbreakers, Peter Green, Eric Clapton, Ten Years After ou les Pretty Things. Cette percée dans de nouveaux réseaux tombait à pic car son public afro-américain se détournait du blues pour les délices de la soul et de la pop de type Motown. Ses enregistrements les plus significatifs étaient déjà loin derrière lui quand il a gravé en 1964 son succès «?Rock Me Baby?» (une reprise de Big Bill Broonzy) et l’album Live at the Regal qui ont commencé à élargir son auditoire. En plus de quinze ans de carrière, B.B. King avait déjà obtenu un succès considérable auprès du public afro-américain avec nombre de chefs-d’œuvre comme Three O’Clock Blues (n°1 r&b, 1951), le très dansant shuffle1 rhythm and blues You Upset Me Baby (n°2 r&b, 1954) ou son célèbre Sweet Little Angel (n°6 r&b, 1956), un plagiat du «?Black Angel Blues?» de Robert Nighthawk (déjà enregistré par Lucille Bogan en 1930 et par Tampa Red en 1934 sous le nom de «?Sweet Black Angel»2). À son tour, son style sera très influent.

Je pense que personne ne vole quoi que ce soit?; Je dirais plutôt qu’on emprunte tous.

— B.B. King

Ce coffret réunit les indispensables enregistrements originaux de ses débuts et de son âge d’or initial en 1949-1962. En effet une page s’est tournée en 1962 quand, comme Ray Charles3, il a rejoint les disques ABC-Paramount réputés pour leur diffusion massive, leur promotion nationale — et leur son impeccable, très accessible, voire commercial (Everyday I Have the Blues, CD3) qui ont assuré son succès grand public.

Gospel

Riley Ben King est né le 16 septembre 1925 dans une plantation isolée entre Itta Bena et Indianola, Sunflower County, état du Mississippi, à 150km au sud de Memphis. Sa famille gérait une petite exploitation de coton en métayage (une part de la récolte — tiers ou moitié — revenait aux King). Cette pratique apparue dans l’état du Mississippi, où de vastes terrains fertiles n’étaient pas cultivés, avait permis à de nombreux Afro-américains et leurs descendants de survivre après l’abolition de l’esclavage en 1865. Le propriétaire du terrain fournissait une mule et une cabane, où vivait une famille. Le système du métayage de différait pas beaucoup de l’esclavage. Il entretenait une misère sans espoir. La crise économique de 1929 n’a fait qu’aggraver une situation déjà dramatique pour la famille King. Comme Muddy Waters, John Lee Hooker et Bo Diddley nés dans le Mississippi rural à la même époque, le jeune B.B. King a été élevé dans des conditions très difficiles. Il n’avait que neuf ans quand sa mère décéda et qu’il dut reprendre l’exploitation. L’éducation, financée par des fondations comme celle d’Anna T. Jeanes, était réduite au strict minimum. Le droit de vote était réservé à ceux qui payaient la poll tax à deux dollars, et rares étaient les Afro-américains qui pouvaient se l’offrir. Le racisme a toujours été particulièrement violent dans le Mississippi, où les lois de ségrégation étaient très dures, les meurtres racistes d’Afro-américains très fréquents — et commis en toute impunité. Le Ku Klux Klan et d’autres groupes criminels pour la suprématie blanche y étaient très actifs. À titre d’exemple, en 1962 un groupe de Blancs ségrégationnistes a attaqué à coups de feu et jets de briques cinq cents policiers déployés pour permettre à James Meredith, le premier Afro-américain inscrit à l’University of Mississippi, d’entrer en classe. L’émeute fit deux morts et des dizaines de blessés graves.

J’ai fait face à plus d’humiliations que je ne pourrais me rappeler.

— B.B. King

La famille King fréquentait un temple baptiste rural où elle chantait les spirituals et le gospel, seul antidote au désespoir, et seule activité sociale. Comme tant de grands musiciens afro-américains, le jeune Riley a été formé au chant dans ce contexte. Il admirait le révérend Sam Crary, chanteur du Fairfield Four, un groupe de gospel de la Fairfield Baptist Church de Nashville, dans le Tennessee tout proche. Comme les œuvres de James Brown, Little Richard, Chuck Berry, Bob Marley, Ray Charles, Aretha Franklin, Bo Diddley, Marvin Gaye et tant d’autres géants du XXe siècle, la musique de B.B. King est directement issue des negro spirituals et du gospel. Il a appris les rudiments de la guitare du beau-frère de sa tante, un pasteur baptiste. Un gospel est inclus ici : Praying to the Lord, bien distinct de sa production blues habituelle. Il en enregistrera régulièrement d’autres, dont une dizaine de classiques des spirituals et du gospel en 1960.

Mississippi Blues

Les baptistes considèrent le blues comme une musique maléfique, et il n’en jouait pas encore quand il a été appelé à l’armée en 1943. C’est dans les rangs de l’U.S. Army que, exclus de son milieu familial, Riley a commencé à jouer des musiques profanes. Ravi d’échapper à sa plantation isolée, il fut notamment inspiré par les disques du virtuose de la guitare sèche Lonnie Johnson, qui avait été le premier à enregistrer de véritables solos, une corde à la fois, à la guitare4. Mais la guerre s’achevait et Riley fut renvoyé chez lui au bout de quelques mois. Motif : un conducteur de tracteur était utile aux champs. Mais décidé à jouer de la musique pour échapper à son destin d’agriculteur, il essaya aussitôt de jouer et de chanter dans les rues — en s’éloignant le plus possible des petites villes du coin pour ne pas être reconnu par sa famille.

Quand j’étais à la campagne et que j’essayais de jouer, on aurait dit que personne ne faisait attention à moi. Les gens disaient «?C’est ce chanteur de vieux blues?».

— B.B. King

L’état du Mississippi s’étend à l’est du grand fleuve, tandis que la Louisiane mitoyenne est située à l’ouest du delta. C’est dans cette région que le blues est né et s’est initialement développé?; la tradition du bluesman vagabond (hobo) guitariste solitaire itinérant plonge ses racines dans la boue du Mississippi. Les plus grands noms du blues rural (country blues) sont originaires de cet état : Henry Sloan, Charlie Patton, Son House, Bukka White, Tommy Johnson, Ishman Bracey, Robert Johnson, Willie Brown, Skip James, R.L. Burnside, Mississippi Fred McDowell, Robert Petway… B.B. King est un pur produit de cette culture.

Né dans le Mississippi, Bukka White (1909-1977) était un des grands maîtres du country blues, un émule de la première grande vedette du blues rural Charlie Patton, qu’il a bien connu. La mère de Bukka White avait pour sœur la grand-mère du futur B.B. King. Remarquable chanteur et guitariste slide utilisant une National Steel (avec un open tuning particulier en mi mineur), le cousin exerçait une fascination sur le jeune Riley, qui lui rendit visite en famille en 1947. De seize ans son aîné, Bukka White lui offrit une guitare sèche Stella — la marque bon marché qu’utilisaient Charlie Patton, Skip James et bien d’autres bluesmen de la région. C’est aussi Robert Lockwood Jr., beau fils de Robert Johnson qui a transmis la tradition du blues de la région à Riley et lui a appris à copier les styles des deux plus importants pionniers de la guitare électrique, le jazzman Charlie Christian5 et le bluesman T-Bone Walker. Les bluesmen professionnels comme Lockwood jouaient dans des plantations et des établissements de bords de route dans le sud, les juke joints ou jook joints. Robert Lockwood accompagnait alors le grand harmoniciste du Tennessee Sonny Boy Williamson I6.

Memphis, Tennessee

Riley avait environ vingt ans quand Sonny Boy présenta Riley à Rufus Thomas, un chanteur de rhythm and blues né dans une famille de métayers du Mississippi installée depuis longtemps à Memphis. Rufus Thomas était un ancien artiste de vaudeville qui animait un concours de jeunes talents au Palace Theater de Memphis. C’est là que Riley compléta sa culture musicale. La plupart des artistes du Mississippi restaient les dépositaires d’une tradition isolée qu’ils transmettaient à leur manière, comme Arthur Crudup ou Big Joe Williams. C’était aussi le cas de Muddy Waters, Elmore James, John Lee Hooker, Howlin’ Wolf et des harmonicistes Sonny Boy Williamson II et James Cotton, des bluesmen du Mississippi qui trouvèrent tous refuge et travail à Chicago. C’est là qu’ils donnèrent un son électrique, nouveau et urbain, à leur tradition du grand sud. En revanche, comme Bo Diddley7, un chicagoan également né dans le Mississippi — et comme Chuck Berry8 à St. Louis — B.B. King se nourrit de nombreuses influences : country, gospel, boogie woogie, jump blues, jazz, ce qui explique peut-être pourquoi il parviendra à séduire le grand public comme Diddley et Berry.

Historiquement, Memphis est la ville où les cultures musicales blanches et afro-américaines se sont rencontrées. Comme d’autres bluesmen légendaires après lui (Howlin’ Wolf, Joe Hill Louis, Sonny Boy Williamson et bien d’autres), Riley Ben King devint disc jockey. Il fit ses débuts avec Sonny Boy Williamson sur KWEM. Fondée en 1947, la station WDIA de Memphis programmait sans succès de la variété légère et de la country. En octobre 1948, les difficultés financières ont décidé les propriétaires blancs à engager Nat D. Williams, un journaliste et enseignant noir, pour animer l’émission Tan Town Jubilee visant spécifiquement le public afro-américain — une grande première aux États-Unis, a fortiori dans le terrible contexte de ségrégation raciale du Tennessee. Cette nouvelle formule originale a aussitôt fonctionné, et WDIA a cherché à engager des animateurs noirs. Pris à l’essai pour une intervention de cinq minutes à l’automne 1948, Riley Ben King est devenu l’un des pionniers de cette radio décisive, qui fera vite des émules. C’est sous le nom de Beale Street Blues Boy qu’il anima dès 1949 une émission de deux heures où il programmait toute une palette de musiques populaires américaines en vogue dans l’après-guerre : le rhythm and blues de Louis Jordan, Nat «?King?» Cole, mais aussi des artistes blancs comme Frank Sinatra, Vaugh Monroe (un trompettiste leader d’un big band) jusqu’au très éclectique Frankie Laine. L’impact de WDIA a été énorme. Il y apprit l’élocution, se débarrassa de ses expressions rurales, et imposa sa personnalité sûre d’elle-même. L’amélioration de soi-même était un thème central de ses émissions comme de ses chansons. Devenu une vedette de la radio tout en jouant parallèlement dans les juke joints de Memphis équipé d’une ES-150 (le premier modèle électrique de Gibson), il raccourcit son nom d’animateur radio «?Blues Boy?» et devint B.B. King.

Sam Phillips

Il fut vite été repéré par Sam Phillips (1923-2003), un ingénieur du son et animateur de radio de 26 ans. Phillips travaillait depuis peu comme découvreur de talents pour les disques Modern, une marque importante basée à Los Angeles. Il enregistra la première séance de B.B. King à Memphis fin 1949 et envoya la bande aux frères Bihari en Californie. Modern avait à Nashville une filiale consacrée aux enregistrements de la région du Tennessee, Bullett Records, qui publièrent deux 78 tours sans succès. Le 3 janvier 1950, Sam Phillips a ouvert son propre studio, le Memphis Recording Service au 706 Union Avenue. Il y enregistra B.B. King durant l’été 1950. Les disques suivants sont sortis sur l’étiquette RPM, une autre sous-marque de Modern. Ils exploraient différentes pistes, dont plusieurs boogies rapides comme B.B. Boogie ou des rocks hurleurs comme She’s Dynamite. L’originalité des blues lents, tendus et électriques, s’est imposée d’elle-même avec le succès. L’influence de Sam Phillips sur la cristallisation du style de B.B. King ne peut pas être sous-estimée. Grand visionnaire, ce producteur génial passionné par les musiques afro-américaines découvrira et dirigera à cette époque rien moins que Howlin’ Wolf, Junior Parker, Rosco Gordon, les Prisonaires, Bobby Blue Bland, Rufus Thomas et James Cotton, pour ne citer qu’eux. Il créera ensuite le rockabilly dans son studio Sun, découvrant et lançant successivement Elvis Presley, Jerry Lee Lewis, Carl Perkins, Johnny Cash, Roy Orbison et tant d’autres — le tout pendant la courte période 1949-1956.

Quant à B.B. King, il restait fortement marqué par Lonnie Johnson et T-Bone Walker, dont le style est à l’origine du blues moderne 9?; Comme T-Bone, il alternait ses phrases de guitare électrique avec les vers qu’il chantait et jouait rarement des accords.

Je ne suis pas bon en accords. Je suis nul en accords.

— B.B. King

Les premiers enregistrements de guitare électrique datent de 1935, mais ce nouvel instrument a commencé à véritablement se répandre dans l’après-guerre avec des succès rhythm and blues de Louis Jordan (avec Carl Hogan à la guitare), le jazz virtuose de Les Paul, Bob Wills (avec Junior Barnard et Eldon Shamblin dans le style western swing) ou encore le «?(Call It) Stormy Monday?» (1947) de T-Bone Walker, qui a tourné une page dans l’histoire du blues (lire le livret et écouter l’anthologie Electric Guitar Story 1935-1962 dans cette collection). B.B. King se distinguait de T-Bone par ses phrases de guitare personnelles, dans lesquelles il enchaînait souvent des croches rapides avec un son saturé, plus agressif, plus dur : un style neuf qui anticipait une partie du langage rock moderne cinq ans avant le «?Maybellene?» de Chuck Berry. B.B. partageait avec les guitaristes Clarence «?Gatemouth?» Brown et T-Bone Walker un goût pour la présence d’instruments harmoniques à vent (saxophones, trompette, trombone) dont les riffs enrichissaient aussi l’aspect rythmique. À l’exception de ses tout premiers enregistrements, cet héritage des orchestres de swing et de jump blues (neuf musiciens) des années 1940 perdurera toute sa vie. Il utilisa une Fender Telecaster à partir de la séance de Blind Love (CD 2) et se procurera aussi une somptueuse Gibson L5 CESN en 1954 (la même que Scotty Moore, guitariste d’Elvis Presley). Côté chant, l’influence de blues shouters comme Jimmy Rushing10 et surtout de rock shouters comme Roy Brown ou Wynonie Harris étaient à la base de son approche au pathos intense, avec de longs «?weeeell?» tendus qui anticipaient fréquemment ses couplets. Il exploitait aussi beaucoup le style déclamatoire de Louis Jordan, l’irrésistible géant de cette période, et incorporera progressivement des clichés du gospel (mélismes, voix de tête) dans son langage. Il faudra encore un an pour que, sous la direction de Sam Phillips et quatre séances de studio plus tard, B.B. King accouche en 1951 de sa version magistrale de Three O’Clock Blues, une composition de Lowell Fulson. Elle montera directement au numéro un des ventes dans les classements R&B réservés aux musiques afro-américaines — ségrégation oblige. B.B. King travaillera avec l’ingénieur du son Bill Holford au studio A.C.A. de Houston, Texas, à partir de 1952, puis enregistrera de fantastiques séances en Californie au milieu des années 1950. Il enchaînera les succès jusqu’en 1970 et continuera à bien vendre très au-delà.

B.B. Blues

Pour B.B. King comme pour tous les artistes de rhythm and blues, le succès d’un disque avait pour conséquence d’interminables tournées mal payées dans le circuit «?chitlin’?», du nom des chitterlings, une recette à base de tripes de porc que l’on y servait (ces abats à bas prix étaient un plat afro-américain emblématique car longtemps consommé par les esclaves). Les disques ne rapportaient pas beaucoup, surtout quand l’interprète ne composait pas ses morceaux. Et quand c’était le cas, il devait partager les droits d’auteur avec ses producteurs, Julius, Saul et Joseph Bihari (apparaissant sous les pseudonymes Taub, Ling et Josea), qui le pousseront à signer des morceaux qu’il n’avait pas composés, comme Three O’Clock Blues pour ne citer que celui-là. Pendant les soixante années suivantes, B.B. King passera donc l’essentiel de sa vie sur la route. D’abord pour gagner sa vie (il a quitté la radio WDIA en 1952), puis par habitude, au gré des aléas du succès. En 1956 au sommet de sa gloire originelle, il donnera pas moins de 340 concerts. Ce mode de vie nomade n’était pas compatible avec une relation affective stable, ce qui explique la vie sentimentale compliquée de l’intéressé (il aura des enfants de six femmes différentes) exprimée ad nauseam par sa musique pendant plus d’un demi siècle.

Nombre d’influences se sont accumulées chez ce musicien réfléchi qui, bien que né dans une exploitation agricole en rase campagne, a su produire un blues urbain des plus raffinés. Qu’il signe les titres ou non, le répertoire de B.B. King s’est nourri des meilleurs morceaux de rhythm and blues en vogue dans les années 1940-1950 comme le Sweet Sixteen de Joe Turner. L’intro de son Please Love Me Baby rappelle par exemple celle du «?Dust my Broom?» (1951) d’Elmore James11?; son Please Help Me fait penser à la mélodie du «?Driftin’ Blues?» de Charles Brown enregistré par Chuck Berry12. Quant à l’intro de guitare de Ain’t the Way to Do It, elle semble bien avoir été inspirée par celle de Carl Hogan sur Ain’t That Just Like a Woman (Louis Jordan and his Tympany Five, 1946), dont Chuck Berry s’inspirera largement pour son célèbre «?Johnny B. Goode?»13.

On a tous des idoles. Joue comme tous ceux qui t’importent, mais essaye d’être toi-même en le faisant.

— B.B. King

Plus que tout, B.B. King a imposé un son, un style qu’il a appliqué à différentes sources. Très influent dès le début des années 1950, il a marqué profondément une génération de guitaristes essentiels de cette décennie, parmi lesquels Mickey Baker (guitariste des séances Atlantic), Otis Rush, Buddy Guy et son ami Johnny Winter14, qui en 1971 enregistrera une mémorable version en public de It’s My Own Fault. Il y en eut bien d’autres, parmi lesquels Jimi Hendrix, Mike Bloomfield, Alvin Lee, Jimmy Page, Eric Clapton et une cohorte de brillants suiveurs : B.B. Junior, Little B.B., Albert Nelson (Albert King), Earl Silas Johnson IV (Earl King) et Frederick Christian (Freddie King) dont le succès «Have You Ever Loved a Woman?» écrit par Billy Myles rappelle beaucoup le Did You Ever Love a Woman de B.B. La mélodie de Woke Up This Morning évoque celle du futur succès rhythm and blues de Clarence «?Frogman?» Henry «?Ain’t Got No Home?» (1956)?; bien d’autres filiations pourraient être citées. Vite devenu le grand bluesman emblématique des années 1950, il fut souvent considéré comme une figure de proue de la communauté afro-américaine martyrisée. Quand le 7 décembre 1956 Elvis Presley fit une apparition amicale à un concert caritatif afro-américain où il se fit prendre en photo avec B.B. King, la presse de droite accusa le jeune Elvis de violer les lois de la ségrégation raciale en vigueur à Memphis, où vivaient les deux hommes. C’est ainsi que Presley a ouvertement exprimé son attachement aux Afro-américains, ce qui contribua beaucoup au scandale du rock. Cette musique était incarnée par le succès démentiel d’Elvis Presley, accusé de dévoyer la jeunesse avec une musique issue de la culture afro-américaine, considérée par certains comme vulgaire — un euphémisme qui cachait mal le racisme inimaginable de l’époque15.

The Thrill Is Gone

Sa popularité auprès du public afro-américain a chuté au début des années 1960, vite relayée par une nouvelle phase internationale relayée par le contrat avec ABC-Paramount. Le «?blues boom?» britannique du milieu des années 1960 accentua la tendance («?Don’t Answer the Door?», 1966). Ces musiciens anglais ne faisaient pourtant pas souvent référence à B.B. King, lui préférant Muddy Waters16, Bo Diddley17, Howlin’ Wolf, Jimmy Reed et quelques autres. Quoi qu’il en soit, avec «?The Thrill Is Gone?», une reprise de Roy Hawkins en 1969, il ajoutera un gros succès à son palmarès déjà impressionnant et renouera ainsi avec un public afro-américain attiré loin du blues par le funk et d’autres styles naissants. Avec son aîné John Lee Hooker (1917-2001), il restera l’icône vivante du blues pour le grand public mondial. Sa collaboration avec le groupe pop irlandais U2 en 1988 sera suivie d’apparitions prestigieuses et de collaborations avec nombre d’artistes de premier plan - y compris quelques mots en duo avec Barack Obama sur un «?Sweet Home Chicago?» all stars en 2012. La longévité de l’intrépide B.B. King, toujours sur scène à près de 90 ans, participe à sa légende.

Bruno Blum

Merci à Gilles Pétard.

© FRÉMEAUX & ASSOCIES 2013

1. Lire le livret et écouter Jamaica & USA - Roots of Ska - Rhythm and Blues Shuffle 1942-1962 (FA5396) dans cette collection.

2. Lire le livret de Gérard Herzaft et écouter l’anthologie Tampa Red - Slide Guitar Wizard 1931-1946 (FA 257) dans cette collection.

3. Lire le livret de Jean Buzelin et écouter Ray Charles 1949-1960 - Brother Ray: The Genius (FA5350) dans cette collection.

4. Lire le livret de Gérard Herzaft et écouter l’anthologie Lonnie Johnson - The Blues 1925-1947 (FA 262) dans cette collection.

5. Lire le livret d’Alain Gerber et écouter Charlie Christian 1939-1941 - The Quintessence (FA 228) dans cette collection.

6. Lire le livret de Gérard Herzaft et écouter «Sonny Boy» Williamson - Chicago 1937-1945 (FA 253) dans cette collection.

7. Lire les livrets et écouter nos deux anthologies The Indispensable Bo Diddley (FA 5376 et FA5406) dans cette collection.

8. Lire le livret et écouter The Indispensable Chuck Berry (FA5409) dans cette collection.

9. Lire le livret de Gérard Herzaft et écouter T-Bone Walker 1929-1950 - Father of Modern Blues Guitar (FA 267) dans cette collection.

10. Lire le livret de Jacques Morgantini et écouter The Greatest Blues Shouters 1944-1955 (FA 5166) dans cette collection.

11. Lire le livret et écouter l’anthologie Electric Guitar Story 1935-1962 à paraître dans cette collection.

12. Lire le livret et écouter l’anthologie The Indispensable Chuck Berry 1954-1961 (FA5409) dans cette collection.

13. La version originale de Ain’t That Just Like a Woman par Louis Jordan & his Tympani Five est incluse dans l’anthologie Electric Guitar Story 1935-1962 à paraître dans cette collection.

14. Lire le livret et écouter l’anthologie Electric Guitar Story 1935-1962 à paraître dans cette collection.

15. Lire les livrets et écouter les anthologies Elvis Presley face à la musique américaine (FA 5361 et FA 5383) dans cette collection.

16. Lire les livrets de Gérard Herzaft et écouter les deux anthologies consacrées à Muddy Waters (FA 266 et FA 273) dans cette collection.

17. Lire les livrets et écouter nos deux anthologies The Indispensable Bo Diddley (FA 5376 et FA5406) dans cette collection.

B.B. King

The Indispensable 1949-1962

by Bruno Blum

The Indispensable B. B. King

B. B. King is the musician most widely responsible for allowing the great American public to discover the blues. And his style, which comes down to us from an old tradition, aided by a voice where the rocker combines with the blues-shouter in verses decorated by rapid bursts of guitar, has conquered not only America but the rest of the world. Despite the racial segregation which still reigned in the Sixties, B. B. King was able to profit from America’s new interest in the blues, a discovery assisted by the success of white British musicians — The Rolling Stones, The Animals, John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers, Peter Green, Eric Clapton, Ten Years After or The Pretty Things. This “blues-rock invasion” of America came just at the right time for him: Afro-Americans were turning away from blues and moving towards the delights of Soul and pop music that was coming out of Motown. His most significant recordings were already a long way behind him in 1964 when he cut his hit “Rock Me Baby” (a reprise of a Big Bill Broonzy song) and the album Live at the Regal, which began broadening his audience. In a career that had already lasted fifteen years, B. B. King had been considerably successful with Afro-American audiences thanks to a number of masterpieces like Three O’Clock Blues (a N°1 R&B hit in 1951), the very danceable R&B shuffle1 You Upset Me Baby (N°2 in the R&B charts in ‘54) or his famous Sweet Little Angel (an R&B N°6 in 1956), which plagiarized Robert Nighthawk’s “Black Angel Blues” (itself already recorded by Lucille Bogan in 1930 — and by Tampa Red in 1934 — as “Sweet Black Angel”2). In turn, B. B.’s style would have great influence.

I don’t think anybody steals anything; all of us borrow.

— B. B. King

This set puts together the indispensable original recordings made by B. B. King at his debuts and during his first Golden Age as a musician, from 1949 to 1962. A new chapter began in 1962 when, like Ray Charles3, B. B. joined ABC-Paramount Records, a firm with a reputation for massive distribution and promotion at a national level… as well as an impeccable sound and some very accessible — some say commercial — records which guaranteed his success with a mass audience (cf. Everyday I Have the Blues, CD3).

Gospel

Riley Ben King was born on September 16th 1925 on an isolated plantation one hundred miles south of Memphis, between Itta Bena and Indianola in Sunflower County, Mississippi. His family managed a little cotton farm under the sharecroppers system — part of the crop, either one third or one half, was kept by the King family —, a practice which originated in Mississippi where vast plots of fertile land weren’t cultivated; it allowed many Afro-Americans and their descendants to survive after slavery was abolished in 1865, as landowners would supply a mule and a shack to a family who worked on the plantation. In fact, sharecropping wasn’t far different from slavery, as it kept the poor in a desperate state of misery. The economic chaos of 1929 only made matters worse for the King family. Like Muddy Waters, John Lee Hooker and Bo Diddley, who were born in rural Mississippi in the same period, the young B. B. King was raised in hardship. He was only nine years old when his mother died and he had to run the farm himself. Education, financed by foundations like that of Anna T. Jeanes, was reduced to a strict minimum. The right to vote was reserved for those who paid the $2 poll-tax, and only rarely could an Afro-American afford to pay. Racism had always been especially violent in the State of Mississippi, where the segregation-laws were extremely hard and where racist murders were quite frequent — and often went unpunished. The Ku Klux Klan and other criminal groups working towards white supremacy were very active in the State. One example: in 1962 a group of white segregationists, armed and throwing bricks, attacked five hundred police who had been deployed to protect James Meredith, the first Afro-American to enrol at the University of Mississippi, and allow him to physically enter the building. A riot ensued causing two deaths and dozens of serious casualties.

I’ve put up with more humiliation than I care to remember.

— B. B. King

The King family regularly went to a rural Baptist church where they sang spirituals and gospel songs; it was the only social activity and the only antidote to despair. As with many great Afro-American musicians, that was how the young Riley learned to sing. He admired Reverend Sam Crary, who sang with The Fairfield Four, a gospel group from the Fairfield Baptist Church in nearby Nashville, Tennessee. Like the works of James Brown, Little Richard, Chuck Berry, Bob Marley, Ray Charles, Aretha Franklin, Bo Diddley, Marvin Gaye and so many other 20th century giants, B. B. King’s music came directly from Negro spirituals and Gospel; he learned the rudiments of guitar-playing from his aunt’s brother-in-law, who was a Baptist preacher. A gospel song is included here: Praying to the Lord is quite different from King’s usual blues songs, and he would record others regularly, notably a dozen classics in the same genre in 1960.

Mississippi Blues

Baptists held the blues to be the music of the Devil, and Riley King wasn’t yet playing blues when he was drafted into the Army in 1943. It was only while under the flag, far from his family milieu, that he began playing non-church music. Delighted to have escaped from his lonely plantation, he found inspiration in the records of acoustic-guitar virtuoso Lonnie Johnson4, who was the first to record genuine solos, plucking the strings one at a time. His time in the army didn’t last for long; Riley was sent back home after a few months, as men who could drive tractors were needed in the fields. But he knew farming wasn’t his destiny, and immediately began singing and playing in the streets… or at least those streets far enough from home so that his family wouldn’t find out what he was doing.

When I was in the country and I was trying to play, nobody seemed to pay too much attention to me. People used to say, ‘That’s just that ole blues singer.’

— B. B. King

The State of Mississippi spreads east of the great river whilst its neighbour Louisiana lies west of the Delta. The blues was born there, and initially developed in the image of the hobo bluesman tradition, with solitary, itinerant guitarists whose roots lay deep in the mud of the Mississippi. Natives of the state include some of the greatest country blues players — Henry Sloan, Charlie Patton, Son House, Bukka White, Tommy Johnson, Ishman Bracey, Robert Johnson, Willie Brown, Skip James, R. L. Burnside, Mississippi Fred McDowell, Robert Petway — and B. B. King was a pure product of that culture.

Bukka White (1909-1977) was one of the great masters, a disciple of the first great country blues star Charlie Patton, whom he knew well; and the sister of Bukka White’s mother was the future B. B. King’s grandmother. A remarkable singer and slide-guitarist — he played a National Steel guitar with open tuning (E minor in particular) — this cousin fascinated the young Riley, who visited him in 1947. Bukka was sixteen years his elder, and he presented his visitor with a Stella acoustic guitar, an inexpensive model used by Patton, Skip James and many other bluesmen in the area. Robert Johnson’s stepson, Robert Lockwood Jr., also transmitted the region’s traditional blues to Riley, teaching him to copy the styles of the two most important pioneers of the electric guitar, jazzman Charlie Christian5 and bluesman T-Bone Walker. Professionals like Lockwood used to play on plantations, and also in the juke or jook joints which lined the roads of the South; it was there that Robert Lockwood accompanied the great Tennessee harmonica-player Sonny Boy Williamson I.6

Memphis, Tennessee

Riley was around twenty when Sonny Boy introduced him to Rufus Thomas, a rhythm & blues singer born into a family of Mississippi sharecroppers who’d been living in Memphis for years. Rufus was a former vaudeville artist, and he used to run amateur talent contests at the Palace Theatre in Memphis. It was there that Riley completed his musical culture. Most Mississippi artists were the guardians of an isolated tradition which they handed down to others in their own way, like Arthur Crudup or Big Joe Williams. So were Muddy Waters, Elmore James, John Lee Hooker, Howlin’ Wolf and harmonica-players Sonny Boy Williamson II and James Cotton, all of them Mississippi bluesmen who found refuge (and work) in Chicago. There, in the Windy City, they gave their Deep South tradition a new electric, urban sound. But B. B. King, like Bo Diddley7 — a Mississippi-born Chicagoan — and Chuck Berry8 in St. Louis, drew sustenance from many influences: country, gospel, boogie woogie, jump blues and jazz, which perhaps explains why King managed to seduce such a large audience, as did Bo Diddley and Chuck Berry.

Historically, Memphis is the city where white and Afro-American music cultures first met. Like other legendary bluesmen after him (Howlin’ Wolf, Joe Hill Louis, Sonny Boy Williamson et al.), Riley Ben King became a disc jockey. He made his radio debut with Sonny Boy Williamson on KWEM. Founded in 1947, the WDIA station in Memphis programmed light pop and country music without meeting much success. In 1948, the station’s financial difficulties prompted its white owners to hire Nat D. Williams, a black journalist and teacher, to host his own Tan Town Jubilee show aimed specifically at an Afro-American audience — it was a great first in the United States, all the more so given the terrible context of racial segregation in Tennessee. The original new format was an immediate success, and WDIA started looking for black presenters. Riley was given a chance to introduce the show for five minutes in the autumn of 1948, and was one of the pioneers who took the station to the top of its format, arousing much competition. Under the name “Beale Street Blues Boy”, by 1949 he was presenting a two-hour show which aired a whole palette of the American music in vogue during those post-war years: rhythm and blues by Louis Jordan and Nat “King” Cole, but also white artists like Frank Sinatra, Vaughn Monroe (a trumpet & trombone player who led his own big band), even the very eclectic Frankie Laine. WDIA had an enormous impact. Riley King learned elocution, ridding himself of his rural expressions, and he stamped the show with his self-assured personality. Bettering oneself was a central theme of his shows (and his songs). Now a radio-star, and still playing in Memphis juke-joints armed with a Gibson ES-150 — the company’s first electric model — Riley shortened his radio pseudonym “Blues Boy” and became B. B. King.

Sam Phillips

B. B. was quickly noticed by Sam Phillips (1923-2003), a 26-year old sound engineer and radio presenter. Phillips had been working for a short time with Modern Records, an important label based in Los Angeles. He recorded B. B. King’s first session in Memphis at the end of 1949 and sent the tapes to the Bihari brothers in California. Modern Records had an affiliate in Nashville, Bullet Records, which specialized in local Tennessee recordings, and Bullet released two 78’s; neither of them sold much. On January 3rd 1950, Sam Phillips opened his own recording studio, Memphis Recording Service, at 706 Union Avenue, and recorded B. B. King there during the summer of 1950. The records that followed were issued on the RPM label, another Modern subsidiary, and they explored different avenues, among them several fast boogie tracks like B. B. Boogie or rock shouters like She’s Dynamite. Original, slow blues numbers, tense and electric, established themselves in the wake of the label’s success. One can’t underestimate the influence of Sam Phillips on the manner in which B. B. King’s style crystallized. A producer of genius, Phillips was also a great visionary with a passion for Afro-American music, discovering and recording such names as Howlin’ Wolf, Junior Parker, Rosco Gordon, The Prisonaires, Bobby “Blue” Bland, Rufus Thomas and James Cotton, to name only some of them. He went on to create Rockabilly in his famous Sun studio, launching first Elvis Presley and then Jerry Lee Lewis, Carl Perkins, Johnny Cash, Roy Orbison and so many others, all in the short period from 1949 to 1956.

As for B. B. King, he remained strongly influenced by Lonnie Johnson and T-Bone Walker, from whose style modern blues originated9; Like T-Bone, B. B. alternated electric guitar phrases with the verses he sung, and only rarely played chords.

I’m no good with chords. I’m horrible with chords.

— B. B. King

The first electric guitar recordings date from 1935, but this new instrument really began to spread after the war, thanks to rhythm and blues hits by Louis Jordan (with Carl Hogan on guitar), virtuoso jazz records by Les Paul, Bob Wills (with Junior Barnard and Eldon Shamblin playing in the western swing style), or else “(Call It) Stormy Monday” (1947) by T-Bone Walker, a disc which wrote a new chapter in the history of the blues (cf. Electric Guitar Story 1935-1962). B. B. King set himself apart from T-Bone by playing his own style of guitar, phrases in which fast eighth notes ran into a saturated sound that was harder and more aggressive: it was a new style, and it anticipated parts of the modern rock-language some five years before Chuck Berry and his “Maybellene” hit. B. B. King and guitarists Clarence “Gatemouth” Brown and T-Bone Walker shared a taste for reed and brass harmony instruments (saxophones, trumpet, and trombone), whose riffs also enhanced the rhythmic aspects of their music. Except in his first recordings, this legacy from the swing orchestras and jump blues bands (nine-piece groups) of the Forties would be a constant throughout B. B. King’s disco-graphy. He used a Fender Telecaster, beginning with the Blind Love session (CD 2), and would also acquire a sumptuous Gibson L5 CESN in 1954 (the same ins-trument which Elvis Presley’s guitarist Scotty Moore played). As for his vocals, the influence of blues shouters like Jimmy Rushing10 — and especially rock shouters like Roy Brown or Wynonie Harris — formed the basis of his approach. Intense pathos, including frequent long wailing cries of “weeeell,…” preceding his verses, was a characteristic of his singing style. He also exploited the declamatory style of Louis Jordan, the irrepressible giant of that period, and would progressively incorporate gospel traits such as melisma or falsetto into his singing. It would take another year and four sessions with Sam Phillips before B. B. King would release his masterly 1951 version of Three O’Clock Blues, a Lowell Fulson composition. It went straight to N°1 in the R&B sales-charts reserved for Afro-American music (another aspect of segregation…). From 1952 onwards B. B. King would work with sound-engineer Bill Holford at the A.C.A. Studio in Houston, Texas, and then in the mid-Fifties he did some fantastic sessions in California. The hits kept coming until 1970, but sales remained constant thereafter.

B. B. Blues

For B. B. King, a successful record had the same consequences as for all rhythm and blues artists: interminable, badly-paid tours on the chitlin’ circuit — it was named after the recipe for chitterlings, the emblematic (cheap) pork-tripe dish long served to slaves and popular with Afro-Americans. Record-sales didn’t bring in much money, especially if the performer didn’t write his own songs; even when B. B. signed his songs he had to share royalties with his producers, Julius, Saul and Joseph Bihari (who appeared under the pseudonyms Taub, Ling and Josea): they manoeuvred him into putting his name to pieces he hadn’t written, like Three O’Clock Blues, to name only one. For the next sixty years B. B. King would spend most of his life on the road: first to earn a living (he left WDIA Radio in 1952), and then out of habit, and he did so with more or less success. In 1956, while at the peak of his original glory, he gave no fewer than 340 concerts. His nomadic existence wasn’t compatible with a stable relationship with any woman, which explains his complicated sentimental life; he would father six children with six different mothers, and his problems with women were themes that saturated his music for over five decades.

Many influences accumulated within this pensive musician whose blues, even though he was a farm-boy born in the middle of nowhere, were some of the most refined urban songs ever produced. Whether he wrote the titles or not, B. B. King’s songbook grew out of the best rhythm and blues pieces that were in fashion in the Forties and Fifties, like Joe Turner’s Sweet Sixteen. The intro to his Please Love Me Baby recalls the beginning of “Dust my Broom” (1951) by Elmore James11 ; his Please Help Me makes you think of the melody in Charles Brown’s “Driftin’ Blues” also recorded by Chuck Berry12. As for the guitar intro of Ain’t the Way to Do It, it seems to have been inspired by Carl Hogan’s introduction on Ain’t That Just Like a Woman (Louis Jordan and his Tympany Five, 1946), which inspired Chuck Berry to record his famous “Johnny B. Goode”13.

We all have idols. Play like anyone you care about, but try to be yourself while you’re doing so.

— B. B. King

Above all else, B. B. King imposed a sound, a style which he applied to different sources. He was already influential in the early Fifties, and deeply marked a whole generation of guitarists forming the essence of that decade, among them Mickey Baker (who played on sessions for Atlantic), Otis Rush, as well as Buddy Guy and his friend Johnny Winter14, who in 1971 recorded a memorable “live” version of It’s My Own Fault. There were many others —Jimi Hendrix, Mike Bloomfield, Alvin Lee, Jimmy Page, Eric Clapton — and a legion of brilliant followers: B. B. Junior, Little B. B., Albert Nelson (Albert King), Earl Silas Johnson IV (Earl King), and Frederick Christian (Freddie King), whose hit “Have You Ever Loved a Woman”, written by Billy Myles, reminds you a lot of B. B. King’s own Did You Ever Love a Woman. The melody of Woke Up This Morning evokes Clarence “Frogman” Henry’s future hit “Ain’t Got No Home” (1956), and many other descendants could be mentioned. He quickly became the great, emblematic bluesman of the Fifties, and was often considered one of the leading lights of the martyred African-American community. On December 7th 1956 when Elvis Presley dropped in at an Afro-American charity concert and had his photo taken with B. B. King, the right-wing press accused the young Elvis of violating the segregation laws of Memphis, where the two men lived. It was in fact Elvis’ way of expressing his attachment to the Afro-American cause, but it just contributed to heighten the scandal surrounding rock. That kind of music was incarnated by the insane success of Presley, a man who stood accused of leading young people astray, and whom many considered as vulgar — a euphemism which scarcely disguised the unimaginable racism which was rife at the time15.

The Thrill Is Gone

His popularity with Afro-American audiences declined in the early Sixties and a new international phase began at the same time as his contract with ABC-Paramount. The British “blues boom” of the mid-Sixties accentuated the trend (“Don’t Answer the Door”, 1966). But the British musicians involved didn’t often mention B. B. King; they preferred to quote Muddy Waters16, Bo Diddley17, Howlin’ Wolf, Jimmy Reed and others as their references. Whatever. With the “The Thrill Is Gone”, a 1969 cover of a Roy Hawkins song, B. B. King would add a substantial hit to his already impressive discography and regain the loyalty of an Afro-American audience which had been drawn away from the blues by funk and other nascent music styles. In the eyes of international audiences, together with his elder, John Lee Hooker (1917-2001), B. B. King would remain a living icon of the blues. His collaboration with the Irish band U2 in 1988 was followed by a number of prestigious partnerships with many first-rate artists… including a few words at the microphone with Barack Obama during an All-Stars version of “Sweet Home Chicago” in 2012. The longevity of the intrepid B. B. King, still alive and kicking at ninety, is part of his legend.

Bruno Blum

Thanks to Gilles Pétard.

© FRÉMEAUX & ASSOCIÉS 2013

1. Listen to Jamaica & USA - Roots of Ska - Rhythm and Blues Shuffle 1942-1962 (FA5396).

2. Cf. Gérard Herzhaft’s booklet with the anthology Tampa Red - Slide Guitar Wizard 1931-1946 (FA 257) in this collection.

3. Cf. Jean Buzelin’s anthology, Ray Charles 1949-1960 - Brother Ray: The Genius (FA5350).

4. Cf. the anthology Lonnie Johnson - The Blues 1925-1947 (FA 262) and the booklet by Gérard Herzhaft.

5. Cf. Charlie Christian 1939-1941 - The Quintessence (FA 228) and the booklet by Alain Gerber.

6. Cf. “Sonny Boy” Williamson - Chicago 1937-1945 (FA 253) and the booklet by Gérard Herzhaft.

7. Cf. the two anthologies The Indispensable Bo Diddley (FA 5376 & FA5406).

8. Cf. The Indispensable Chuck Berry (FA5409).

9. Cf. T-Bone Walker 1929-1950 - Father of Modern Blues Guitar (FA 267) and the booklet by Gérard Herzhaft.

10. Cf. The Greatest Blues Shouters 1944-1955 (FA 5166) and the booklet by Jacques Morgantini.

11. Cf. Electric Guitar Story 1935-1962 (to be released).

12. Cf. The Indispensable Chuck Berry 1954-1961 (FA5409).

13. The original version of Ain’t That Just Like a Woman by Louis Jordan & his Tympani Five appears in the anthology Electric Guitar Story 1935-1962 (to be released).

14. Cf. Electric Guitar Story 1935-1962 (to be released).15. Cf. the two-volume anthology Elvis Presley face à la musique américaine (FA 5361 & FA 5383).

16. Cf. the two anthologies devoted to Muddy Waters and the booklets by Gérard Herzhaft (FA 266 & FA 273).

17. Cf. the two anthologies The Indispensable Bo Diddley (FA 5376 & FA5406).

Discographie 1

1. Miss Martha King (Riley B. King aka B.B. King)

2. Take a Swing With Me (Riley Ben King aka B.B. King)

Riley Ben King as B.B. King-v; Thomas Branch-tp; Sammie Jett-tb; Ben Branch-ts; Phineas Newborn Jr.-p; Richard Green aka Tuff -b; Phineas Newborn Sr.-d. Produced by Sam Phillips or possibly Overton Ganong. Memphis, circa June, 1949.

3. Mistreated Woman (Riley Ben King aka B.B. King)

4. B.B. Boogie (Riley Ben King aka B.B. King)

5. The Other Night Blues (Riley Ben King aka B.B. King, Joseph Bihari as Joe Josea)

6. Walkin’ and Cryin’ (Riley Ben King aka B.B. King, Saul Samuel Bihari as Sam Ling)

Riley Ben King as B.B. King-v; Calvin Newborn-g; Phineas Newborn, Jr.-p; Richard Green aka Tuff-b; Earl Forest-d. Produced by Sam Phillips for the Bihari Brothers, Sun Studio, Memphis, circa July 1950.

7. My Baby´s Gone (Riley Ben King aka B.B. King, Julius Jeramiah Bihari as Jules Taub)

8. Don’t You Want a Man Like Me (Riley Ben King aka B.B. King)

9. Questionnaire Blues (Riley Ben King aka B.B. King, Joseph Bihari as Joe Josea)

10. B.B. Blues (Riley Ben King aka B.B. King)

11. A New Way of Driving (Riley Ben King aka B.B. King, Saul Samuel Bihari as Sam Ling)

Riley Ben King as B.B. King-v, g; E. A. Kamp-ts; Ford Nelson-p; James Walker-b; Solomon Hardy-d. Produced by Sam Phillips for the Bihari Brothers, Sun Studio, Memphis, January 8, 1951.

12. She’s Dynamite

(Hudson Woodbridge aka Hudson Whittaker aka Tampa Red)

Riley Ben King as B.B. King-v, g; Richard Sanders-ts; possibly Calvin Newborn, g; unknown-p, b, d. Produced by Sam Phillips for the Bihari Brothers, Sun Studio, Memphis, circa May 27, 1951.

13. She’s a Mean Woman (Riley Ben King aka B.B. King, Julius Jeramiah Bihari as Jules Taub)

14. Hard Workin’ Woman (Riley Ben King aka B.B. King, Julius Jeramiah Bihari as Jules Taub)

15. Pray for You

(Riley Ben King aka B.B. King)

Same as CD 1, track 12-add unknown ts; ensemble v on 14. Produced by Sam Phillips for the Bihari Brothers, Sun Studio, Memphis, June 18, 1951.

16. Three O’Clock Blues (Lowell Fulson)

17. That Ain’t the Way to Do It (unknown)

18. She Don’t Move Me No More (Riley Ben King aka B.B. King)

Riley Ben King as B.B. King-v, g; unknown g on 17; Adolph Duncan aka Billy-ts except on 17; Ike Turner-p on 16; Johnny Ace-p on 17 & 18; James Walker-b; Earl Forest-d. Produced by Sam Phillips for the Bihari Brothers, Sun Studio, Memphis, circa September, 1951.

19. Shake It Up and Go (Riley Ben King aka B.B. King)

20. It’s My Own Fault (aka My Own Fault, Darlin’) (Riley Ben King aka B.B. King)

21. Gotta Find my Baby (Riley Ben King aka B.B. King)

Riley Ben King as B.B. King-v, g; Richard Sanders-ts; unknown sax; Johnny Ace-p; George Joyner-b; Earl Forest-d; Onzie Horne-vb; omit saxes on 20. Produced by Sam Phillips for the Bihari Brothers, Sun Studio, Memphis, January 24, 1952.

Note : 19 adapted from James Johnson aka Stump Johnson’s The Duck’s Yas Yas Yas.

22. Low Down Dirty Baby (Riley Ben King aka B.B. King)

Riley Ben King as B.B. King-v, g; Raymond Hill-as; unknown-b, d; Onzie Horne-vb. Produced by Sam Phillips for the Bihari Brothers, Sun Studio, Memphis. January 24, 1952.

23. Someday Somewhere (Riley Ben King aka B.B. King)

Same as CD 1, tracks 19, 20 & 21.

Discographie 2

1. Blind Love (Who Can Your Good Man Be)

(Riley Ben King aka B.B. King, Julius Jeramiah Bihari as Jules Taub)

Riley Ben King as B.B. King-v, g; Floyd Jones-tp; George Coleman-as, ts; Bill Harvey-ts; Connie Mack Booker-p; James Walker-b; Ted Curry-d; Charles Crosby-congas. Produced by Bill Holford and Riley B. King as B.B. King for the Bihari Brothers, A.C.A. Studio, Houston, late 1952.

2. Everything I Do Is Wrong (Riley Ben King aka B.B. King, Julius Jeramiah Bihari as Jules Taub)

B.B. “Blues Boy” King and his Orchestra: Riley Ben King as B.B. King-v, g; Jewell Grant-as; Maxwell Davis-ts; Hubert Myers aka Bump-ts; unknown saxes, Willard McDaniel-p; unknown b; Jesse Sailes-d. Los Angeles, February 6, 1954.

3. You Didn’t Want Me (Riley Ben King aka B.B. King)

4. You Know I Love You (Riley Ben King aka B.B. King)

5. Boogie Woogie Woman (Riley Ben King aka B.B. King, Julius Jeramiah Bihari as Jules Taub)

Riley Ben King as B.B. King-v, g; unknown as, ts, bs, b, d; possibly Ike Turner-p.

Produced by Sam Phillips for the Bihari Brothers, Sun Studio, Memphis, 1952.

6. Woke Up this Morning (My Baby Was Gone) (Riley Ben King aka B.B. King, Julius Jeramiah Bihari as Jules Taub)

7. Don’t Have to Cry (aka Past Day) (Riley Ben King aka B.B. King, Julius Jeramiah Bihari as Jules Taub)

8. Please Love Me (Riley Ben King aka B.B. King, Julius Jeramiah Bihari as Jules Taub)

9. Highway Bound (Riley Ben King aka B.B. King, Julius Jeramiah Bihari as Jules Taub)

10. Bye! Bye! Baby (Riley Ben King aka B.B. King)

11. Can’t We Talk it Over (aka Come Back Baby) (Walter Davis)

Same as CD 2, track 1.

12. Please Hurry Home (Riley Ben King aka B.B. King, Julius Jeramiah Bihari as Jules Taub)

Same personnel as CD 2, track 1. Cincinnati, August 1953.

13. Praying to the Lord (Riley Ben King aka B.B. King, Julius Jeramiah Bihari as Jules Taub)

14. Why Did You Leave Me

Same as CD 2, track 1.

15. Please Help Me (Riley Ben King aka B.B. King, Julius Jeramiah Bihari as Jules Taub)

Same personnel as CD 2, track 1. Cincinnati, August 1953.

16. Please Remember Me (Riley Ben King aka B.B. King, Julius Jeramiah Bihari as Jules Taub)

Riley Ben King as B.B. King-v, g; possibly same personnel as CD 2, track 1; unknown org replaces p. Possibly Covington, Tennessee, circa January 1953.

17. The Woman I Love (Peter Joe Clayton)

Same as CD 2, track 2.

18. When my Heart Beats Like a Hammer (John Lee Williamson)

19. Every Day I Have the Blues (Peter Chatman aka Memphis Slim)

Same as CD 2, track 2; possibly Charles Crosby, congas. Los Angeles, March 2, 1954.

20. Ten Long Years (I Had a Woman) (Riley Ben King aka B.B. King, Julius Jeramiah Bihari as Jules Taub)

21. Boogie Rock (House Rocker) (Riley Ben King aka B.B. King, Joseph Bihari as Joe Josea)

Riley Ben King as B.B. King-v, g; Johnny Board-ts; Maxwell Davis, sax; unknown saxes, tp, b; Willard McDaniel-p; Ted Curry or Jesse Sailes-d. Los Angeles, 1955.

22. Crying Won’t Help You (Hudson Whittaker aka Tampa Red)

Riley Ben King as B.B. King-v, g; Johnny Board-ts; Maxwell Davis, sax; unknown saxes, tp, b; Willard McDaniel-p; Ted Curry or Jesse Sailes-d. Possibly Chicago, 1955.

23. Bad Luck (Ivory Joe Hunter)

Riley Ben King as B.B. King-v, g; Johnny Board-ts; Maxwell Davis, sax; unknown saxes, tp, b; Willard McDaniel-p; Ted Curry or Jesse Sailes-d. Los Angeles, November 19, 1955.

Discographie 3

1. You Upset Me, Baby (Riley Ben King aka B.B. King, Julius Jeramiah Bihari as Jules Taub)

Riley Ben King as B.B. King-v, g; unknown as, ts, bs, p, b, d. Los Angeles, circa August 18/19, 1954.

2. Did You Ever Love a Woman (Arnold Dwight Moore)

Riley Ben King as B.B. King-v, g; Johnny Board-ts; Maxwell Davis, sax; unknown saxes, tp, b; Willard McDaniel-p; Ted Curry or Jesse Sailes-d. Los Angeles, December 10, 1955.

3. Sweet Little Angel (Hudson Whittaker aka Tampa Red)

Riley Ben King as B.B. King, v, g; Calvin Owen, Kenneth Sands aka Kenny-tp; Lawrence Burdine-as; Johnny Board-ts; Floyd Newman, Fred Ford or Herman Green-bs; Milliard Lee-p; Jymie Merritt-b; Ted Curry-d. Produced by Julius, Saul and Joseph Bihari. Los Angeles, April or May 1956.

4. You Don’t Know (Walter Spriggs)

5. I Stay in the Mood (Riley Ben King aka B.B. King, Joseph Bihari as Joe Josea)

Same as above, add Plas Johnson-ts, g. Produced by Julius, Saul and Joseph Bihari. Los Angeles, September 16, 1956.

6. Be Careful with a Fool (Riley Ben King aka B.B. King, Joseph Bihari as Joe Josea)

Same as CD 3, track 3-add Plas Johnson-ts, g. Chicago, 1956.

7. On my Word of Honor (Samuel Ram, Claude Baum)

Same as CD 3, tracks 4 & 5.

8. Days of Old (Riley Ben King aka B.B. King, Julius Jeramiah Bihari as Jules Taub)

Riley Ben King as B.B. King, v, g; Kenneth Sands aka Kenny, Henry Boozier-tp; Lawrence Burdine-as; Johnny Board-ts; Barney Hubert-bs; Milliard Lee-p; Marshall York-b; Ted Curry, d. Produced by Julius, Saul and Joseph Bihari. Los Angeles, circa January, 1958.

9. Worry, Worry (David Plumber, Maxwell Davis, Julius Jeramiah Bihari as Jules Taub)

10. Please Accept my Love (Clarence J. Garlow)

Same personnel as CD 3, track 8. Houston, August, 1958.

11. Sweet Sixteen (parts 1&2) (Ahmet Ertegun)

Riley Ben King as B.B. King, v, g; unknown tp, saxes, p, b, d. Produced by Julius, Saul and Joseph Bihari. Los Angeles, October 26, 1959.

12. Bad Luck (Riley Ben King aka B.B. King, Julius Jeramiah Bihari as Jules Taub)

Same as CD 3, track 3.

13. Hold That Train (Riley B. King aka B.B. King, Joseph Bihari as Joe Josea)

14. Walkin’ Dr. Bill (Peter J. Clayton) Got to Find my Baby ?

15. It’s My Own Fault (Riley Ben King aka B.B. King, Julius Jeramiah Bihari as Jules Taub)

16. You Done Lost Your Good Thing Now (Riley Ben King aka B.B. King, Joseph Bihari as Joe Josea)

Riley Ben King as B.B. King, v, g; Lloyd Glenn-p; Ralph Hamilton-b; Jesse Sailes-d. Produced by Julius, Saul and Joseph Bihari. Unknown location, possibly Los Angeles, circa March 3, 1960.

17. Downhearted (How Blue Can You Get) (Riley Ben King aka B.B. King, Joseph Bihari as Joe Josea)

Riley Ben King as B.B. King, v, g; Plas Johnson-ts; Maxwell Davis-p; unknown b, d. Produced by Julius, Saul and Joseph Bihari. Los Angeles, January 9, 1962.

18. I’ll Survive (Riley Ben King aka B.B. King, Saul Samuel Bihari as Sam Ling)

Riley Ben King as B.B. King, v, g; Henry Boozier, John Browning or Kenneth Sands aka Kenny-tp; Pluma Davis-tb; Lawrence Burdine-as; Barney Hubert bs; Johnny Board-ts; Lloyd Glenn-p; Marshall York-b; Ted Curry or Sonny Freeman-d. Produced by Julius, Saul and Joseph Bihari. Los Angeles, March 16, 1960.

19. Peace of Mind (Riley Ben King aka B.B. King, Joseph Bihari as Joe Josea)

Riley Ben King as B.B. King, v, g; unknown tp, saxes, p, b, d, strings. Produced by Julius, Saul and Joseph Bihari. Los Angeles, April 10, 1961.

20. Going Down Slow (James Burke Oden aka St. Louis Jimmy Oden)

Same as CD 3, 17.

21. Down Now (Riley Ben King aka B.B. King, Julius Jeramiah Bihari as Jules Taub)

Riley Ben King as B.B. King, v, g; John Browning, Kenneth Sands aka Kenny-tp; Johnny Board-ts, bs; Milliard Lee-p; Marshall York-b; Sonny Freeman-d. Produced by Julius, Saul and Joseph Bihari. Los Angeles, January 10, 1961.

CD BB King The Indispensable 1949-1962, BB King © Frémeaux & Associés 2013.