- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

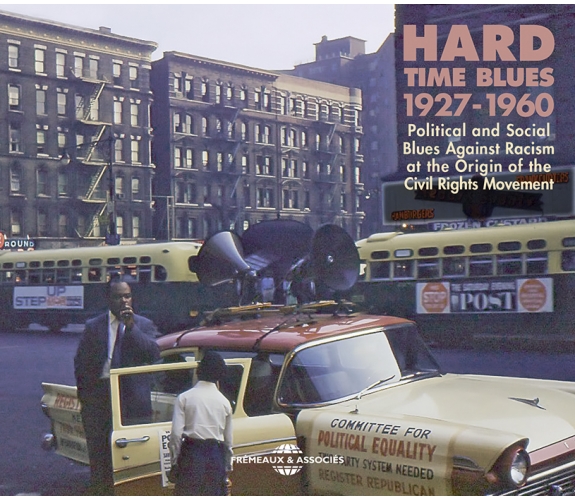

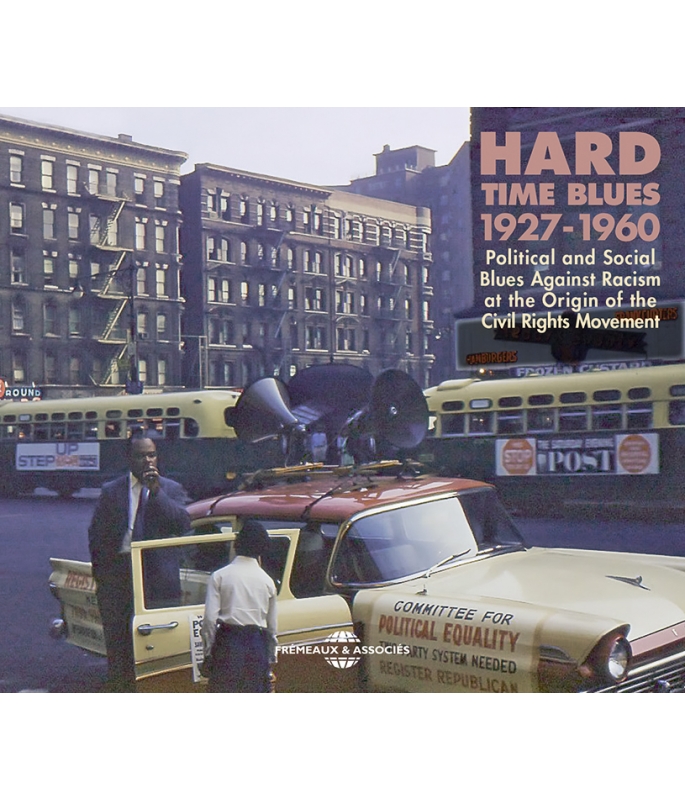

POLITICAL AND SOCIAL BLUES AGAINST RACISM AT THE ORIGIN OF THE CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT

BIG BILL BROONZY, JOSH WHITE, LIGHTNIN’ HOPKINS, J.B. LENOIR,…

Ref.: FA5480

EAN : 3561302548029

Artistic Direction : JEAN BUZELIN ET JACQUES DEMÊTRE

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Total duration of the pack : 2 hours 28 minutes

Nbre. CD : 2

POLITICAL AND SOCIAL BLUES AGAINST RACISM AT THE ORIGIN OF THE CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT

POLITICAL AND SOCIAL BLUES AGAINST RACISM AT THE ORIGIN OF THE CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT

With its roots in segregation, the blues echoed all the political and social events of the 20th century in the United States, and bore witness to the reactions of Afro-Americans to racism, poverty, hunger, unemployment, prison… Beginning with the Depression up to the Civil Rights struggle, Jean Buzelin and Jacques Demêtre have put together a series of themes touching on the New Deal, wars, natural catastrophes, elections and all the daily problems confronting the black community which has still not found its rightful place within American white society. Patrick FRÉMEAUX

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Defense Factory BluesJosh WhiteJosh White00:02:441941

-

2Uncle Sam SaysJosh WhiteJosh White00:02:461941

-

3Million Lonesome WomenBrownie McGheeBrownie McGhee00:02:351941

-

4You Better Be Ready To GoTampa RedHudson Whittaker00:03:041941

-

5Uncle Sam Came And Get ItWee Bea BoozeP. Grainger00:03:161942

-

6The Number Of MineBig Bill BronzyWilliam Lee Conley Broonzy00:02:451940

-

7Get Back (Black Brown And White)Big Bill BronzyWilliam Lee Conley Broonzy00:03:041951

-

8Cell N°13 BluesBig Bill BronzyWilliam Lee Conley Broonzy00:02:571945

-

9County Jail BluesBig MaceoM. Merriweather00:02:571941

-

10No Job BluesRamblin' ThomasWalter Thomas00:03:121928

-

11There Is No JusticeJimmy JordanWilliam Lee Conley Broonzy00:02:431932

-

12Parchman Farm BluesBukka WhiteWinston White00:02:421940

-

13I'M Prison Bound (Doin' Time Blues)Lowell FulsonL. Carr00:03:131948

-

14Penitentiary BluesHopkins Lightin'00:02:561959

-

15The Bourgeois BluesHuddie LedbetterLomax00:03:251939

-

16Jim Crow (Blues)Lead BellyHuddie Ledbetter00:02:251944

-

17Jim Crow TrainJosh WhiteCuney Waring00:02:491956

-

18Back-Water BluesBessie SmithBessie Smith00:03:201927

-

19When The Levee BreaksJoe McCoyJoe McCoy00:03:181929

-

20Mean Old TwisterArnold KokomoJames Arnold00:03:001937

-

21Florida HurricaneSaint Louis JimmyJames B. Oden00:02:561948

-

22Income Tax BluesRalph WillisWillis Ralph00:02:391951

-

23Collector Man BluesSonny Boy WilliamsonJohn Lee Williamson00:03:201937

-

24It's Hard TimeJoe StoneJoe Stone00:03:111933

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1President RooseveltBig Joe WilliamsJohn Lee Williams00:03:531960

-

2Don't Take Away My P.W.A.Jimmie GordonJimmie Gordon00:02:571936

-

3W.P.A. BluesCasey Bill WeldonL. Melrose00:03:201936

-

4Working On The ProjectPeetie Wheatstraw00:03:071937

-

5Let's Have A New DealCarl MartinCarl Martin00:02:461935

-

6Welfare Store BluesSonny Boy WilliamsonJohn Lee Williamson00:02:521940

-

7Warehouse Man BluesChampion Jack DupreeJack Dupree00:02:501940

-

8F.D.R. BluesChampion Jack DupreeJack Dupree00:02:401945

-

9God Bless Our New PresidentChampion Jack DupreeJack Dupree00:02:451945

-

10President's BluesHerman RayHerman Ray00:03:171949

-

11Eisenhower BluesJ.B. LenoirJ.B. Lenoir00:02:541954

-

12Korea BluesJ.B. LenoirJ.B. Lenoir00:02:461950

-

13Back To Korea BluesSunnyland SlimA. Luandrew00:03:131950

-

14Crazy WorldJulia LeeRalph Burns00:03:011947

-

15The World Is In A TangleJimmy RogersJimmy Rogers00:02:581951

-

16Hard Times BluesIda CoxIda Cox00:02:591939

-

17Hard TimesCharles BrownMike Stoller00:03:111951

-

18No ShoesEddie KirklandEddie Kirkland00:02:401953

-

19Lonesome Cabin BluesBaby Roy WarrenWarren Baby Roy00:03:011949

-

20Poor Boy BluesBrownie McGheeBrownie McGhee00:02:481947

-

21Pawnshop BluesBrownie McgheeBrownie McGhee00:03:291960

-

22The Alabama Bus Pt.1&2Brother Will HairstonBrother Will Hairston00:04:331956

-

23Democrat ManJohn Lee HookerJohn Lee Hooker00:03:301960

-

24The Big RaceMemphis SlimP. Chatman00:05:481960

CLICK TO DOWNLOAD THE BOOKLET

Hard time blues FA5480

HARD TIME BLUES

1927-1960

Political and Social

Blues Against Racism

at the Origin of the

Civil Rights Movement

HARD TIME BLUES

Political and Social blues against racismAt the origin of the Civil Rights Movement

1927-1960

Par Jean Buzelin et Jacques Demêtre

« Le blues n’est pas, et n’a jamais prétendu être, un phénomène purement social, c’est en premier lieu une forme poétique et en second lieu une façon de créer de la musique. »

LeRoi Jones, Le peuple du blues, 1963 (Gallimard, 1968)(1)

Le blues, vocal et instrumental, apparaît comme l’une des formes musicales les plus originales et significatives créées par les descendants des esclaves africains transplantés en Amérique du Nord. Né à la fin du 19e siècle dans le sud des Etats-Unis, il prend ses racines sur un terrain composé de deux situations contradictoires et antagonistes : l’émancipation, proclamée par le président Lincoln en 1862 et entérinée par le Congrès à la fin de la guerre de sécession, et la ségrégation, instituée par les lois « Jim Crow » et l’arrêt de la Cour suprême de 1896. L’émancipation permet à l’homme noir de s’affranchir du « groupe », de s’individualiser, la ségrégation le maintient, l’enferme, dans sa communauté. « Le blues s’est développé en même temps que la société noire en Amérique, écrit Paul Oliver ; il est né du drame d’un groupe, isolé par la couleur de sa peau, et néanmoins forcé de s’adapter à une société qui lui refuse l’intégration totale. »(2) Le blues se construit donc, et se développe ainsi dans les marges de la société américaine. Même s’il est parfois invité à distraire quelques Blancs lors de petites fêtes locales, le bluesman s’adresse quasi-exclusivement à ses frères et sœurs de couleur, et bien rares sont les amateurs blancs qui sont touchés, et intéressés, par ses disques qui, à partir de 1920, sont catalogués dans la catégorie race records, donc essentiellement destinés au public noir. Le chanteur de blues est à la fois une sorte de colporteur des histoires de, et pour, sa communauté, et de troubadour « indépendant » en ce sens que, plus qu’un simple témoin, il modèle ces histoires selon son point de vue et son vécu personnels.

Le blues n’est pas une forme musicale protestataire au sens où on l’entendait dans les années 60 avec les protest songs, ni une expression de résignation. « Durant les années 20 (…), aucun Noir ne se serait avisé de protester — et encore moins d’invoquer ses droits — lorsqu’il était victime de la discrimination raciale. »(3) Comme il lui est impossible d’exprimer ouvertement son hostilité envers l’oppresseur dominant, le bluesman prend à partie les siens en leur faisant part de ses problèmes, de ses états d’âme, de sa tristesse, mais aussi de ses joies et ses capacités à transcender sa condition grâce à des dons d’observation souvent caustiques qu’il manifeste à travers un humour à double sens que seuls les membres de sa communauté peuvent comprendre et apprécier. C’est une manifestation de revendication à usage interne, voire de révolte contenue et de résistance passive — on peut y voir l’une des sources de la non-violence de Martin Luther King. En effet, notamment jusqu’à la Seconde Guerre mondiale, manifester plus ouvertement exposerait le bluesman — le Noir — à des ennuis et des représailles (on cherchera en vain, à l’époque, un blues parlant ouvertement de lynchage ou du Ku-Klux-Klan). Le Noir doit rester à sa place, ne doit surtout pas s’occuper des affaires des Blancs, et encore moins les provoquer.

Le parti que nous avons choisi pour illustrer musicalement ces « temps difficiles » est celui du ressenti, de la réaction du bluesman face aux évènements auxquels il est confronté et à ses conséquences, et non au commentaire de l’événement lui-même. Pour cela nous avons puisé uniquement dans les disques commerciaux, c’est-à-dire destinés à l’audition publique, avec les limites que cela engendrait. Les producteurs, tous blancs, n’auraient jamais accepté, surtout avant-guerre, un morceau par trop contestataire, et les musiciens étaient « libres » dans la mesure où leurs disques se vendaient (4). En outre, à une exception près (et encore), nous sommes restés volontairement dans le domaine profane, celui du blues, tout en sachant que les chants religieux, negro spirituals et gospel songs, traitent aussi largement des problèmes du quotidien.

« La majeure partie de son répertoire [le blues] baigne dans l’ambiance qui règne dans les ghettos noirs. Les sujets les plus fréquemment abordés, outre celui de l’amour frustré, ont trait à la misère, à la faim, au chômage, aux catastrophes naturelles, à la prison ou à la maladie, tous phénomènes qui frappent particulièrement la population noire et qui composent une toile de fond des conditions de vie dans les ghettos. »(5)

Cela ne veut pas dire que le chanteur de blues reste insensible aux évènements politiques et sociaux. Soit il les commente à sa façon, soit il réagit à ceux-ci lorsqu’ils touchent sa communauté et son environnement, en particulier les plus dramatiques qui la frappent en priorité. « Le bluesman tient avant tout la chronique des évènements qui touchent le groupe social dont il est le porte-parole. Dans ce domaine, il se limite en général à son expérience locale. »(6)

Il y a donc le quotidien : racisme, ségrégation, discriminations, interdits de toute nature, brutalités et brimades physiques ou morales, avec pour corollaire la prison, thème très souvent chanté. Il y a les évènements ponctuels, comme les catastrophes naturelles (inondations, cyclones, tornades, ouragans) qui, si elles n’épargnent personne, frappent en premier lieu les plus démunis, les Noirs étant en général les derniers à bénéficier des secours et des aides (voir l’exemple récent de l’ouragan Katrina à la Nouvelle-Orléans, et ceci au 21e siècle !). Il y a les difficultés récurrentes et le poids des charges qui s’abattent sur les épaules fragiles de la population noire : logements, impôts, tracasseries administratives, pauvreté, dénuement, délinquance, etc.

Ces difficultés éclatent au grand jour durant la période de la Grande Dépression qui suit le krach de Wall Street en 1929 et dont les Noirs subirent les effets de la crise de plein fouet. Les bluesmen qui la vivaient directement — grosses chutes de la production et de la vente des disques — la commentent abondamment, soit qu’ils insistent sur les aspects négatifs (chômage, misère, queues devant la porte de magasins vides, errance…), soit qu’ils en soulignent les côtés positifs amenés par le New Deal et les programmes de grands travaux initiés par l’Administration Roosevelt ; le chanteur restant néanmoins souvent sceptique quant aux résultats dont il peut bénéficier. « Le New Deal fut incapable, écrit Giles Oakley (…), de déboucher sur les changements radicaux de la société américaine qu’un certain nombre de mesures avait semblé annoncer. Les années 30 marquèrent néanmoins un changement décisif dans les relations entre l’Amérique noire et la blanche. Les Noirs se sentirent davantage impliqués dans le mouvement général de la société et beaucoup d’entre eux commencèrent à tourner leur regard vers le gouvernement, avec le sentiment que quelque chose pouvait être fait. »(7)

C’est donc à partir de ce moment que les situations plus directement politiques, et notamment les hommes qui les portent, entrent dans les paroles des blues. Herbert Hoover brièvement, pour l’aspect négatif, Franklin Roosevelt abondamment, et en qui la communauté noire met beaucoup d’espoirs. Espoirs qui, retombés après-guerre avec Truman et Eisenhower, renaissent avec l’élection de John F. Kennedy.

Nous avons donc tenté de mettre en lumière tout ce mouvement au travers d’un choix de thèmes, de chansons et d’interprètes qui montrent bien l’évolution de la prise de conscience du Noir Américain en général, et du bluesman en particulier. Après la contestation « interne » des années 30, le temps de la guerre permet un champ de réactions plus ouvert, notamment à propos des discriminations dans l’armée ou dans les usines qui travaillent pour l’effort de guerre. Un intérêt pour ces thèmes qui se poursuit avec la guerre de Corée, la « guerre froide », et l’état du monde en général qui concerne à présent une population minoritaire qui sort de son isolement forcé.

Peut-on parler de politisation ? Il faut attendre le tournant des années 30/40 pour que certains bluesmen, notamment ceux qui sont reçus dans les milieux avancés et progressistes de New York (Harlem ou Greenwich Village), expriment ouvertement leur point de vue. Lorsqu’ils sont acceptés et reconnus par une frange blanche libérale, ils peuvent sortir de leur réserve (communautaire) et afficher des positions plus affirmées, voire contestataires. Lead Belly et surtout Josh White (8), Sonny Terry & Brownie McGhee dans une moindre mesure, qui fréquentent des chanteurs de folk songs engagés et militants, comme Woody Guthrie ou Pete Seeger (9), montrent au grand jour une forte conscience sociale et politique, souvent d’ailleurs personnelle et individuelle. Il en est ainsi de Champion Jack Dupree, John Lee Hooker, Memphis Slim, ou Big Bill Broonzy, certainement encouragé par ses fréquentations européennes (10).

Cette prise de conscience va se manifester de façon exemplaire, dans les années 50 et 60, chez J.B. Lenoir, chanteur de blues réellement « engagé », qui va faire entendre de véritables blues protestataires, accompagnant à sa manière la lutte pour les droits civiques et autres mouvements contestataires (Alabama Blues ou Vietnam en 1965).

Mais, en même temps qu’il émerge et s’ouvre vers de nouveaux publics (jeunes amateurs Américains blancs, Européens), le blues traditionnel perd peu à peu de son influence auprès de sa propre communauté, laissant sa place à la Soul music, laquelle va être le véritable support musical encadrant tous les grands mouvements des années 60.

Demeurent les témoignages de trente années décisives qui ont conduit l’homme noir de son « enfermement » forcé à la perspective qui lui laissait entrevoir sa libération tant espérée.

Morceaux choisis

Les blues et morceaux apparentés, rassemblés dans le présent coffret, proviennent de disques qui ont été enregistrés depuis les années 20 jusqu’en 1960. C’est dire qu’ils correspondent à une époque où les Noirs des Etats-Unis continuaient, malgré quelques améliorations, à être victimes de discriminations raciales ouvertes ou latentes qui les maintenaient dans un statut social inférieur au sein de la société américaine.

Première partie

Le premier disque s’ouvre sur une période cruciale de l’Histoire des Etats-Unis, celle de la Seconde Guerre mondiale. Les Noirs y ont largement participé, tout en étant en butte à toutes sortes de préjugés. Le chanteur-guitariste Josh White (1915-1969) en fait état dans Defense Factory Blues qui parle du refus d’embauche d’un jeune Noir dans une usine travaillant pour l’effort de guerre. Dans Uncle Sam Says, il énumère ce que les Noirs ont dû subir dans l’aviation, la marine et l’armée de terre, mais il formule l’espoir de voir un jour cesser le règne de Jim Crow (Jim le Corbeau), personnage qui symbolise le raciste le plus extrême.

Got my long government letter

My time to go

When I got to the army

I’m on the same ol’ Jim Crow

Uncle Sam says

Two camps for Blacks and Whites

But when trouble starts

We’ll all be in the same big fight.

(…)

If you ask me I think

Democracy is fine

I mean democracy

Without the colour line

Uncle Sam says

We’ll live an american way

Let’s get together

And kill Jim Crow today.

(Josh White, Uncle Sam Says, 1941)

D’une façon générale, cette guerre et ses prémices ont donné naissance à des blues que l’on pourrait qualifier de « complaintes de recrutement » à l’égard de l’ingrat Oncle Sam, c’est-à-dire des Etats-Unis qui ne réaliseront l’intégration raciale dans leur armée qu’en… 1948.

Dans ce registre, nous entendrons des œuvres comme Million Lonesome Women par le chanteur-guitariste Brownie McGhee (1915-1996), You Better Be Ready To Go par le chanteur-guitariste Tampa Red (1903-1981) et le pianiste Big Maceo, Uncle Sam Came And Get My Him par la chanteuse Bea Booze (1920-1965) et le pianiste Sammy Price, et This Number Of Mine par le chanteur-guitariste Big Bill Broonzy (1893-1958) et le pianiste Memphis Slim. Dans ce dernier morceau, le chanteur se plaint d’être poursuivi par le nombre 158 dans diverses circonstances de sa vie, notamment en recevant son « questionnaire » pour être incorporé dans l’armée.

I’ve got my questionnaire

And I found that old number of mine (bis)

Well I think I’m gonna start moving

Baby don’t need to crying.

All you young men

I mean come and follow me (bis)

American soldiers went before

Well why can’t we?

(Big Bill Broonzy, The Number Of Mine, 1940)

En 1951, le même chanteur Big Bill Broonzy a enregistré un véritable pamphlet contre le racisme anti-noir sous le titre Black, Brown And White, ceci à Paris lors d’une tournée européenne de concerts. De retour aux Etats-Unis, il a réenregistré, malgré les réticences des producteurs, ce même thème sous le titre plus sibyllin de Get Back que nous entendrons ici. Après avoir cité des cas de racisme dans l’embauche, le montant des salaires, etc., le chanteur appelle, tout comme Josh White dix ans plus tôt, à la fin de l’ère Jim Crow. Ce morceau est ponctué par le refrain insistant : « Si tu es blanc, tout va bien, si tu es brun, tiens-toi à l’écart ; mais comme tu es noir, frère, va-t-en, va-t-en, va-t-en. »

This little song that I’m singing about

People you know is true,

If you’re black and go to work for living

That’s what they say to you

If you’re white, it’s all right

If you’re brown, stick around

But as you’re black, brother

Get back, get back, get back.

(Big Bill Broonzy, Get Back, 1951)

Mais là où le racisme contre les Noirs était particulièrement dur et même violent, c’était dans leurs rapports avec la police, les tribunaux, et le monde carcéral, sans parler de la peine de mort à laquelle ils ont payé un lourd tribut. Le répertoire des chanteurs de blues s’en ressent évidemment, car ils expriment les sentiments de révolte contre les arrestations souvent arbitraires, les jugement hâtifs, et les détentions trop longues dans des cellules ou dans des fermes pénitentiaires où ils sont soumis à d’harassants travaux forcés.

C’est ce qu’on entend à travers les blues du même et prolifique Big Bill Broonzy avec Big Maceo au piano, dans Cell N°13 Blues, de Big Maceo (1905-1953) lui-même au chant et au piano avec Tampa Red à la guitare dans County Jail Blues, des chanteurs-guitaristes Ramblin’ Thomas (1902-1945) dans No Job Blues, Lonnie Johnson (prob.1899-1970) dans There Is No Justice, Bukka White (1906-1977) dans l’autobiographique Parchman Farm Blues, et Lowell Fulson (1921-1999) dans I’m Prison Bound, créé par le chanteur-pianiste Leroy Carr vingt ans auparavant. Et nous pourrions en proposer bien d’autres.

Judge give me life this morning

Down on Parchman farm (bis)

I wouldn’t hate it so bad

But I left my wife and my home.

(…)

We got to work in the morning

Just at dawn of day (bis)

Just at the setting of the sun

That’s when the work is done.

(Bukka White, Parchman Farm Blues, 1940)

Même les femmes étaient astreintes à ces travaux forcés, comme nous le confirme le chanteur-guitariste Lightnin’ Hopkins (1912-1982) dans Penitentiary Blues ; ce thème relate des évènements qui se sont déroulés dans l’État du Texas en 1910 et qui sont restés dans les mémoires. Cette année-là, le gouverneur Bud Russell fit travailler des femmes aux côtés des hommes dans un ou plusieurs pénitenciers de la vallée de la rivière Brazos.

Ne quittons pas ce monde carcéral sans signaler que, parmi tous les prisonniers noirs, figura notamment le célèbre chanteur-guitariste Huddie Ledbetter, dit Lead Belly (1885-1949), qui purgea une longue peine dans les pénitenciers du Sud des Etats-Unis. Découvert en 1934 par le folkloriste John Lomax, qui effectuait des collectages pour le compte de la Bibliothèque du Congrès (Library of Congress) de Washington, il fut libéré sur parole et alla vivre au nord du pays. Dans certains de ses nombreux disques, Lead Belly raconte qu’il y a rencontré des préjugés raciaux, certes moins durs que la ségrégation institutionnalisée des États du Sud, mais néanmoins très humiliants. Parmi ses chansons protestataires, retenons The Bourgeois Blues et Jim Crow Blues.

Me and my wife run all over town

Everywhere we go

The people would turn us down

Lord in the bourgeois town

I got the bourgeois blues

Gonna spread the news all around.

(Lead Belly, The Bourgeois Blues, 1939)

Bunk Johnson (*) told me too

This old Jim Crow

Dead bad luck for me and you.

(…)

One thing people

I want everybody to know

You gonna find some Jim Crow

Every place you go.

(Lead Belly, Jim Crow Blues, 1944)

Le même personnage de Jim Crow apparaît dans Jim Crow Train où l’on retrouve le chanteur-guitariste Josh White qui reprend, quinze ans après, un thème déjà gravé par lui-même en 1941 (ce qui illustre la lenteur de la déségrégation raciale dans le sud des Etats-Unis).

En plus des manifestations directes du racisme dues au comportement des Blancs, des effets secondaires de ce racisme furent provoqués par les catastrophes naturelles qui ravagent périodiquement le territoire et les côtes des Etats-Unis. Elles engendraient des conséquences dramatiques pour les populations mal loties, essentiellement les Noirs et les Blancs pauvres, qui vivaient souvent dans les basses-terres en contrebas des grands fleuves (les low lands).

L’une des catastrophes les plus spectaculaires fut la crue du Mississippi de 1927. Après d’incessantes pluies, le fleuve déborda et rompit les digues de protection sur cent cinquante points, en plus des dynamitages volontaires effectués pour épargner la Nouvelle-Orléans.

Cette inondation, qui fit 700 000 sans-abri dont la moitié parmi la communauté noire, inspira à la chanteuse Bessie Smith (1894-1937), assistée de James P. Johnson au piano, son fameux Back-Water Blues, qui fut repris par bien d’autres interprètes. De leur côté, le duo de guitaristes Joe McCoy (prob.1905-1950) qui chante, et Memphis Minnie enregistra un When The Levee Breaks. À ces deux morceaux présents dans notre recueil, nous avons ajouté un thème sur les méfaits d’une tornade : Mean Old Twister du chanteur-guitariste Kokomo Arnold (1901-1969), et un autre sur ceux d’un ouragan : Florida Hurricane du chanteur St.Louis Jimmy (1905-1977) accompagné par Sunnyland Slim au piano et Muddy Waters à la guitare.

It rained five days

And the skies turned dark as night (bis)

The trouble taken place

In the lowland at night.

(Bessie Smith, Back Water Blues, 1927)

Les deux plages suivantes se réfèrent aux tracasseries auxquelles les Noirs étaient soumis de la part du fisc. S’il s’agit là d’un phénomène quasi universel, celui-ci était spécialement aigu pour cette population du fait qu’elle vivait le plus souvent au jour le jour sur le plan financier et ne disposait pas de réserves pour payer ses impôts.

C’est ainsi que le chanteur-guitariste Ralph Willis (1910-1957), accompagné par Brownie McGhee, se plaignait, dans Income Tax Blues, d’être imposé sur tout ce qu’il utilisait ou consommait, tandis que dans Collector Man Blues, le chanteur-harmoniciste John Lee «Sonny Boy » Williamson (1914-1948) nous racontait qu’il était obligé de se cacher lorsque le percepteur venait à son domicile.

La pièce qui conclut ce premier disque est intitulée It’s Hard Time ; elle est dévolue au chanteur-guitariste Joe Stone alias J.D. Short (1902-1962). Elle résume à elle seule les temps difficiles et la misère subie par la communauté afro-américaine durant la Dépression qui suivit la grande crise de 1929. Le chanteur parle de Hooverville ; ainsi étaient surnommés les innombrables bidonvilles du temps du président Herbert Hoover. Remarquons qu’il s’agit d’un des rares enregistrements de blues effectués en 1933, l’année la plus dure avant que les programmes de l’adminis-tration Roosevelt ne commencent à faire leur effet. Ce que nous allons constater…

Seconde partie

Le second disque s’ouvre sur un important épisode de l’Histoire des Etats-Unis, à savoir l’élection du démocrate Franklin D. Roosevelt à la présidence du pays en 1932. Venant après la crise économique de 1929 et de la grande dépression qui suivit et provoqua un chômage de masse, notamment parmi la communauté noire, le programme (New Deal) du nouveau président réussit à sortir progressivement le pays du marasme, par le lancement d’une série de grands travaux d’intérêt général. Ceux-ci étaient pilotés par des organismes tels que la C.W.A. (Civil Works Administration) que remplacera la W.P.A. (Works Progress Administration), et la P.W.A. (Public Works Administration) ; ils étaient relayés par un réseau de services sociaux comme les bureaux d’assistance (relief stations), de bienfaisance (welfare stations) et des entrepôts de marchandises à bon marché (warehouses). Globalement bénéfique pour les Noirs, lesquels ont voué un véritable culte pour Roosevelt, ce système a connu néanmoins des dysfonctionnements dus à la relative timidité de l’équipe du président dans sa lutte contre le racisme anti-noir.

Les blues de cette période se sont évidemment fait l’écho de ces évènements. Mais en préambule, prenons connaissance de l’hommage posthume enregistré en 1960 par le chanteur-guitariste Big Joe Williams (1903-1982) sous le simple titre President Roosevelt. Quant aux pièces suivantes, rien que leur appellation reconstitue l’ambiance dans laquelle vivait alors les Noirs. Don’t Take Away The P.W.A. par le chanteur Jimmie Gordon (ca.1906-?), W.P.A. Blues par le chanteur-guitariste Casey Bill Weldon (1909-ca.1970), Working On The Project par le chanteur-pianiste Peetie Wheatstraw (1902-1941) et le guitariste Kokomo Arnold, Let’s Have A New Deal par le chanteur-guitariste Carl Martin (1906-1979), Welfare Store Blues (le magasin de l’assistance) par Sonny Boy Williamson à nouveau, accompagné par Joshua Altheimer au piano, et Warehouse Man Blues par le chanteur-pianiste Champion Jack Dupree (1910-1992). Au sujet des aspects négatifs du programme de Roosevelt, ces chanteurs se plaignent que le bureau d’assistance ait fermé ses portes et que l’entrepôt reste pratiquement vide ; il faut aller trouver un « vrai Blanc », dit Sonny Boy, pour qu’il vous signe un bon qui lui permettra d’obtenir une paire de chaussures dépareillées !

You go to the warehouse

White folks say it ain’t no use (bis)

Government ain’t givin’ away

Nothing but that canned grape-fruit juice.

(Champion Jack Dupree, Warehouse Man Blues, 1940)

Mais ces quelques vicissitudes n’empêchèrent pas l’énorme émotion soulevée chez les Noirs par le décès de Roosevelt en 1945, et leur espoir dans le programme du nouveau président Harry Truman. Cette popularité rejaillira sur le Parti démocrate auquel les Noirs resteront toujours fidèles dans leur ensemble, mais qui perdra les élections présidentielles de 1952 avec l’arrivée du général Eisenhower. Toutes ces péripéties ont inspiré les chanteurs de blues comme le même Champion Jack Dupree dans une sorte d’oraison funèbre intitulée F.D.R. Blues, et dans ses vœux au président Truman sous le titre God Bless On New President — il le regrettera plus tard ! —, ainsi que le chanteur Herman Ray (1914-?) assisté du pianiste Sammy Price dans President’s Blues où il compare Truman aux présidents Lincoln et Roosevelt. Tout autre son de cloche chez le chanteur-guitariste J.B. Lenoir (1929-1967) dans Eisenhower Blues, disque qui fut censuré en 1954 comme étant trop désobligeant envers le président en exercice.

I sure feel bad

With tears running down my face (bis)

I lost a good friend

Was a credit to our race.

(…)

I know I can see

With my friends got sad news (bis)

Cause he run away

And left me

And I got the F.D.R. blues.

(Champion Jack Dupree, F.D.R. Blues, 1945)

Sur le plan international, on se souvient qu’après la fin de la Seconde Guerre mondiale en 1945, les Etats-Unis et leurs alliés sont entrés en conflit larvé avec l’URSS et les pays du bloc soviétique (les « Rouges »). Ce fut l’époque de la « guerre froide » qui se transforma en guerre réelle en Corée et au Vietnam. À nouveau, on vit ressurgir des « complaintes du recrutement » avec des disques comme Korea Blues du même J.B. Lenoir avec Sunnyland Slim (1907-1995) au piano, celui-ci chantant un Back To Korea en compagnie de Snooky Pryor à l’harmonica.

En dehors du conflit armé en Corée, la guerre froide a également donné lieu à plusieurs blues qui restituent très bien l’atmosphère angoissée qui parcourait le monde compte tenu des armes atomiques dont disposaient les grandes puissances. Dans Crazy World, la chanteuse-pianiste Juila Lee (1902-1958) exposait ses états d’âme à ce sujet et prônait une réconciliation générale par l’amour entre les hommes et les femmes. Dans un registre plus grave, le chanteur-

guitariste Jimmy Rogers (1924-1997) déclarait, dans The World Is In A Tangle, qu’il allait se creuser une cave pour pouvoir se réfugier dans le sous-sol.

I’ve got my questionnaire man

I’ve got my class card too

I begin to feel so worried

I don’t know what to do

You know I’m gonna build myself a cave

And move down in the ground.

(Jimmy Rogers, The World Is In A Tangle, 1951)

Les deux morceaux qui suivent portent le titre de Hard Times et sont successivement interprétés par la chanteuse Ida Cox (1889-1967) et par le chanteur-pianiste Charles Brown (1922-1999). Les paroles chantées par Ida Cox sont particulièrement hallucinantes lorsqu’elle se dit assiégée dans sa cabane par des loups affamés. Même du temps de Roosevelt, il y eut des périodes de misère et de détresse pour les Noirs.

I’ve never seen

Such real hard times before (bis)

The wolf keeps walking

All around my door.

They howled all night long

And they moaned till the break of day (bis)

They seemed to know

My good man gone away.

(Ida Cox, Hard Times Blues, 1939)

Les temps difficiles vécus par les Noirs servent de toiles de fond aux thèmes de la misère, de la solitude et de l’errance. On peut l’entendre chez les chanteurs-guitaristes Eddie Kirkland (1928-2011) dans No Shoes, Baby Boy Warren (1919-1977) dans Lonesome Cabin Blues, et Brownie McGhee dans Poor Boy. Celui-ci, avec son partenaire Sonny Terry (1911-1986) à l’harmonica, ajoutait même à ce tableau la nécessité d’avoir recours à un prêteur sur gages dans Pawnshop Blues.

Notre sélection se poursuit avec The Alabama Bus interprété par un ouvrier d’usine et preacher, Brother Will Hairston (1919-1988). À la façon narrative d’un negro spiritual, celui-ci décrit l’affaire qui s’est déroulée en 1955 et 56 dans la ville de Montgomery, capitale de l’État de l’Alabama. Il y régnait alors une ségrégation raciale absolue, notamment dans les autobus d’une manière particulièrement inique : les Noirs devaient être assis à l’arrière et les Blancs à l’avant, mais si l’un d’eux était debout, il avait le droit d’exiger d’un Noir assis de lui céder sa place.

Or, le 1er décembre 1955, une femme noire du nom de Rosa Parks refusa, spontanément et sans préméditation, de se lever pour laisser sa place à un jeune Blanc. Appelée par le chauffeur du bus, la police l’arrêta, et elle fut passée en jugement. Alertés par les associations et églises noires, dont celle dirigée par le pasteur Martin Luther King, les Noirs décidèrent unanimement de boycotter les autobus tant qu’ils appliqueraient cette loi ségrégationniste. (11)

Au bout de près d’un an de ce boycott éprouvant animé principalement par le révérend King, la Cour Suprême des Etats-Unis donna raison à la communauté noire par un arrêt daté du 13 novembre 1956. Ces évènements accélérèrent la déségrégation raciale qui se produisit — avec quelles difficultés et résistances ! — dans les États du Sud à partir des années 60.

Martin Luther King y acquis de son côté une stature nationale en prenant la tête de son mouvement pour les droits civiques (civil rights), dont on peut dire, par ailleurs, que bien des signes avant-coureurs étaient déjà contenus de façon ouverte ou sous-entendue dans les blues choisis ici parmi bien d’autres. Cette stature se renforça par une renommée internationale à partir de la grande marche de Washington en 1963. Prix Nobel de la Paix l’année suivante, le Dr King paya de sa vie sa courageuse action non-violente en étant assassiné par un Blanc à Memphis en 1968.

Trois ans après les évènements de Montgomery, les Etats-Unis sont entrés dans la campagne électorale qui devait aboutir à l’élection de leur nouveau président à la fin de l’année 1960. Le chanteur-guitariste John Lee Hooker (1917-2001) participa à sa manière à cette campagne en enregistrant un morceau titré Democrat Man. Il y proclamait sa foi dans le parti démocrate et reprochait aux femmes d’avoir fait perdre ce parti aux précédents scrutins qui avaient vu, par deux fois, la victoire du républicain Dwight Eisenhower. Aussi leur lançait-il un pathétique appel à ne plus commettre la même erreur (the same mistake) cette fois-ci.

Effectivement, ce fut le démocrate John F. Kennedy qui l’emporta sur le républicain Richard Nixon. Cette victoire fut accueillie avec joie et espoir par le peuple noir. Avec l’humour décapant qu’on lui connaissait, le chanteur-pianiste Memphis Slim (1915-1988) salua, dans The Big Race (la grande course), la victoire de l’« âne » (symbole curieux du parti démocrate) sur l’« éléphant » (le parti républicain).

Well, we finally won the Big Race

While the Elephant for eight years

Has been taking the place.

(…)

But you know we had a good jockey,

A jockey wwho was willing to fight

And take the inside track

And come out front with the Civil Rights.

(Memphis Slim, The Big Race, 1960)

Certes, Kennedy n’eut pas le temps, avant son assassinat en 1963, de faire appliquer tout son programme, et ce fut son successeur Lyndon B. Johnson qui abolit partout la ségrégation raciale en 1964… officiellement mais pas dans les mœurs et les mentalités dans les États du Sud.

Hélas, ces bonnes nouvelles furent endeuillées, durant les années 60, non seulement par la mort de John Kennedy, mais aussi par des émeutes et des affrontements raciaux, et surtout par l’assassinat du pasteur Martin Luther King (sans parler de ceux de Malcolm X ou de Robert Kennedy). Néanmoins, la porte s’était ouverte vers une marche pour l’égalité des droits entre toutes les composantes de la société américaine. Mais, pour y parvenir réellement, le chemin sera encore bien long… Jusqu’à ce qu’un événement pres-que incroyable se produise quarante ans plus tard : l’élection d’un Noir, Barack Obama, à la présidence de la République !

Malgré cela, plusieurs faits dramatiques récents nous ont cruellement rappelé que cette « égalité » était loin d’être acquise.

Jean BUZELIN & Jacques DEMÊTRE

© 2014 FRÉMEAUX & ASSOCIÉS

Notes :

(1) Si nombre d’historiens, d’ethnomusicologues, d’observateurs de la musique populaire noire et du blues en particulier partagent le même avis, le point de vue de LeRoi Jones (Amiri Baraka, 1934-2014) possède un poids incontestable, l’auteur étant l’un des représentants les plus engagés de la communauté afro-américaine dès le début des années 60.

(2) Paul Oliver, Le Monde du blues (Arthaud, 1962).

(3) op. cit. Avec une exception notoire, le Jim Crow Blues de Cow Cow Davenport enregistré en 1927.

(4) Les enregistrements « de terrain », effectués notamment par John et Alan Lomax dans le cadre de la Bibliothèque du Congrès, n’avaient pas ce souci et les chanteurs amateurs pouvaient s’exprimer plus librement dans la mesure où ces enregistrements n’étaient pas destinés à la publication.

(5) Jacques Demètre, Évènements & Figures historiques à travers les chants populaires noirs (Jazz Hot n° 345/46-347-348, janvier-février-mars 1978).

(6) Robert Springer, Fonctions sociales du blues (Parenthèses, 1999).

(7) Giles Oakley, Devil’s Music, Une histoire du blues (1976) (Denoël, 1985).

(8) Voir leur histoire et leur combat respectifs dans les livrets de Gérard Herzhaft : Lead Belly (FA 269) et Josh White (FA 264).

(9) Sans parler de ces grandes figures artistiques noires que sont Paul Robeson ou Marian Anderson.

(10) William Lee Conley Broonzy & Yannick Bruynoghe, Big Bill Blues (1955) (Ludd, 1987).

(11) The Alabama Bus est reconnu comme étant le premier disque dans lequel apparaît le nom de Martin Luther King :

I wanna tell you ‘bout the Reverend Martin Luther King,

You know, they tell me that the people began to sing.

You konw, the man God sent out in the world,

You know, they tell me that the man had the mighty nerve.

Photos & collections : Jacques Demêtre (1959), Frank Driggs, X (D.R.) ; Edwin Rosskam, John Vachon, Walker Evans, Jack Delano (Library of Congress).

Nous remercions Patrice Buzelin, Jean-Paul Levet et Nicolas Teurnier pour leur aide.

HARD TIME BLUES

Political and Social blues against racism

At the origin of the Civil Rights Movement

1927-1960

By Jean Buzelin and Jacques Demêtre

“The blues is not, and has never claimed to be, a purely social phenomenon, it is first and foremost part of a poetic form and secondly a way of making music”.

LeRoi Jones, Blues People 1963

(Apollo Editions, NYC) (1)

The blues, both vocal and instrumental is one of the most original and significant musical forms created by the descendants of African slaves transported to North America. Born at the end of the 19th century in the southern states of America, it was rooted in two contradictory and opposing situations: emancipation, declared by President Lincoln and ratified by Congress at the end of the War of Secession, and segregation, resulting from the “Jim Crow” laws and the 1896 decree of the Supreme Court. Emancipation enabled Negroes to become part of a group, to see themselves as individuals, while segregation kept them confined to their own community. Paul Oliver wrote “The blues has grown with the development of Negro society on American soil; it has evolved from the peculiar dilemma in which a particular group, isolated by its skin pigmentation or that of its ancestors, finds itself when required to conform to a society which yet refuses its full integration within it.” (2) Thus the blues was formed and developed on the margins of American society. Even though occasionally invited to entertain white audiences at small local parties, the bluesman spoke almost exclusively to his coloured brethren and few white fans were moved by or interested in recordings which, from 1920 onwards, were catalogued as race records and thus aimed essentially at a black audience. The blues singer was both a sort of pedlar of stories about and for his own community and an “independent” troubadour in the sense that, rather than just a mere onlooker, he based these stories on his own point of view and experience.

The blues is not the same as the protest songs of the 60s, nor does it express resignation. “During the 20s (…) it was unwise for any black man to protest – or even less proclaim his rights – while he was the object of racial discrimination.” (3) As it was impossible for him to express openly his hostility to his oppressors, the bluesman invited his own people to share his problems, his moods and his sadness, but also his joys and his ability to overcome his condition thanks to often caustic humorous observations, with a double meaning easily understood by his audience. This was an internal protest, a form of passive resistance – one of the sources of the non-violence preached by Martin Luther King. In fact, until the Second World War, more open protest would have exposed Negroes to reprisals (there were no blues at the time referring openly to lynchings or to the Ku Klux Klan). The black man had to know his place and must never interfere in the affairs of white men and, still less, provoke them.

The part of the present blues compilation illustrating this difficult time reveals the reactions of bluesmen to events confronting them and the consequences, not a commentary on the events themselves. Hence, we have chosen only commercial records i.e. those intended for public listening with all the limits that this entails. Producers, all white, would never have accepted, especially pre-war, an overly anti-establishment piece. The musicians were “free” as long as their records sold. (4) Furthermore, with barely any exception, we have kept to the secular domain although we know that Negro spirituals and gospel songs to a great extent also cover everyday problems.

Jacques Demêtre pointed out that the main part of the blues repertoire reflects the atmosphere that reigned in the black ghettos. The most popular subjects, apart from thwarted love, were poverty, hunger, unemployment, natural catastrophes and prison or illness, all of which formed the background to ghetto life. (5)

This did not mean that a blues singer was unaware of political and social problems. Either he treated them in his own way, or reacted to those that touched his own community, in particular those that affected them directly. Robert Springer explains that the bluesman was concerned principally with events that directly touched the social group for which he was the spokesman. He usually limited himself to his local experience. (6)

This included everyday life: racism, segregation, discrimination, all sorts of bans, brutality and physical and moral harassment. There were occasional events (floods, cyclones, tornados and hurricanes) which, although no-one was immune, affected most severely the poorest, Negroes being generally the last to receive help and support (e.g. hurricane Katrina in New Orleans and this in the 21st century!). There were also recurring problems the brunt of which was borne by the black population: rent, taxes, administrative red tape, poverty, delinquency etc.

These problems came to the fore during the Great Depression which followed the Wall Street Crash in 1929 when the effects hit mainly the black population very hard. Bluesmen who felt this directly – huge falls in production and sales of records – commented on it widely, either by underlining the negative aspects (unemployment, poverty, queues in front of empty shops, homelessness …) or by pointing out the positives resulting from the New Deal and the work programmes introduced by the Roosevelt Administration while, however, still remaining sceptical about what benefits this would bring them. Giles Oakley writes that the New Deal was incapable of bringing about the radical changes in American society which a number of measures seemed to have promised. However, the 30s did mark a definite change in relations between black and white Americans. Afro-Americans felt more involved in general social movement and many of them began to turn to the government, believing that something might be possible. (7)

It was from this point that politics and, in particular, politicians began to feature more prominently in blues lyrics. Herbert Hoover briefly, in a negative light, and Franklin Roosevelt more widely on whom the black community based their hopes. . Hopes which, after the war, fell with Truman and Eisenhower but revived again with the election of John F. Kennedy.

Hence, we have tried to highlight this movement with a choice of themes, songs and singers which illustrate the increasing awareness of Afro-Americans and bluesmen in particular. After the less obtrusive protest of the 30s the war gave rise to more open reactions, especially concerning discrimination in the armed forces and in factories working for the war effort. An interest in such themes continued during the Cold War with the Korean War and the world situation in general concerning a minority beginning to emerge from its enforced isolation.

However, the blues only became truly politicised in the early 40s when certain bluesmen, in particular those welcomed in forward-thinking and progressive New York milieus (Harlem or Greenwich Village), expressed their opinions openly. Once accepted and recognised by a white liberal fringe, they felt free to shed their community’s normal reserve and declare their own, often anti-establishment views. Lead Belly and especially Josh White (8) and Sonny Terry & Brownie McGhee to a lesser extent, who rubbed shoulders with committed and militant folk singers such as Woody Guthrie or Pete Seeger (9), did not hesitate to show a strong social and political conscience, moreover often personal and individual. The same went for Champion Jack Dupree, John Lee Hooker, Memphis Slim and Bog Bill Broonzy, some of whom were encouraged by European tours. (10)

This political awareness was revealed clearly in the 50s and 60s by J.B. Lenoir, a truly committed blues singer, whose protest songs underlined the struggle headed by the Civil Rights Movement (Alabama Blues or Vietnam in 1965).

However, at the same time as gaining a new public of young white American and European fans, traditional blues were gradually losing influence within their own community, replaced by Soul music which would become the vehicle for all the important movements of the 60s.

There remain these testimonies of thirty years that led the Afro-American out of his enforced isolation and allowed him a glimpse of that long hoped for freedom.

The pieces chosen

The blues and similar pieces which make up this compilation were all recorded between the 1920s and 1960, covering a period when the black population of the United States, in spite of certain improvements, was still subject to racial discrimination, whether open or veiled, and were still regarded as inferior within American society.

Part 1

The first CD opens on a crucial period for the United States, that of the Second World War in which black Americans had played a large part even though they still faced all kinds of prejudice. Singer/guitarist Josh White (1915-1969) refers to this in Defence Factory Blues which tells of a young black man being refused a job in a factory that was contributing to the war effort. In Uncle Sam Says he recounts what blacks have to suffer in the air force, the marines and the army, but he also expresses the hope that the day will come when Jim Crow (a symbol of the most extreme racism) will reign no longer.

(Josh White, Uncle Sam Says, 1941) : see lyrics in the French text

Overall this war and what it revealed gave birth to a blues that were a form of “recruitment laments” against Uncle Sam i.e. the US government that did not acknowledge racial integration in the armed forces until 1948.

Examples include Million Lonesome Women by singer/guitarist Browne McGhee (1915-1996), You Better Be Ready To Go by singer/guitarist Tampa Red (1903-1981) and pianist Big Maceo, Uncle Sam Came And Get My Him by vocalist Bea Booze (1920-1965) and pianist Sammy Price and This Number Of Mine by singer/guitarist Big Bill Broonzy (1893-1958) and pianist Memphis Slim. On the latter the singer complains about being followed by the number 158 at various times of his life, notably when he received his call up papers to join the army.

(Big Bill Broonzy, The Number Of Mine, 1940) : see lyrics in the French text

In 1951 Big Bill Broonzy, in Paris during a European tour, also recorded a veritable tract against anti-black racism entitled Black, Brown And White. On returning to the States he re-recorded it, in spite of reticence on the part of producers, but with the more enigmatic title Get Back, the version heard her. After quoting examples of racism in employment, unequal pay etc. he calls for an end to the Jim Crow era, just as Josh White had done ten years earlier. The song is punctuated by the insistant refrain: “If you’re white, it’s alright, if you’re brown, stick around, but as you’re black brother, get back, get back, get back.”

(Big Bill Broonzy, Get Back, 1951) : see lyrics in the French text

However, harsh and even violent examples of anti-black attitudes were even more prevalent among the police and within the judicial and prison systems, not to mention the death sentence which exerted a particularly heavy toll on black men. Blues singers’ repertoires obviously reflected these injustices, expressing anger against these arbitrary arrests, hasty judgements and long incarceration in cells or on penitentiary farms where prisoners were subject to exhausting forced labour.

All this is heard on the blues of the prolific Big Bill Broonzy with Big Maceo on piano, on Cell N° 13 Blues and those of Big Maceo (1905-1953) himself providing vocals and piano with Tampa Red on guitar on County Jail Blues, singer/guitarists Ramblin’ Thomas (1902-1945) on No Job Blues, Lonnie Johnson (circa 1899-1970) on There Is No Justice, Bukka White (1906-1977) on the autobiographical Parchman Farm Blues and Lowell Fulson (1921-1999) on I’m Prison Bound, created by Leroy Carr twenty years earlier – and, of course, many others.

(Bukka White, Parchman Farm Blues, 1940) : see lyrics in the French text

Even the women had to do forced labour as singer/guitarist Lightnin’ Hopkins (1912-1982) recounts on Penitentiary Blues that relates the memorable events that took place in Texas in 1910, the year that the governor Bud Russell forced women to work alongside men in several penitentiaries along the river Brazos valley.

We can’t leave this prison environment without men-tioning that these black prisoners included Huddie Ledbetter, known as Leadbelly (1885-1949) who served a long sentence in a prison in the South. Discovered in 1934 by musicologist John Lomax, who was making a collection of folk music for the Library of Congress in Washington, he was released on parole and went to live in the north. On several of his records Leadbelly recounts how he had come up against racial discrimination which, although less open than in the south, was still humiliating. His protest songs include The Bourgeois Blues and Jim Crow Blues.

(Lead Belly, The Bourgeois Blues, 1939) and

(Lead Belly, Jim Crow Blues, 1944) : see lyrics in the French text

The figure of Jim Crow also appears on Jim Crow Train that singer/guitarist Josh White reprised fifteen years after he had already recorded it in 1941 (which shows how slow the progress of racial de-segregation was in the southern states).

In addition to overt racism on the part of white Americans, secondary effects resulted from natural catastrophes that periodically ravaged coastal areas. They had dramatic consequences for the less fortunate population, mainly black Americans and poor whites who often lived on lowlands subject to flooding. One of the most spectacular of these was the Mississippi floods in 1927. Following continuous rain, the river burst its banks and broke through the flood barriers in fifty places, worsened by deliberate dynamiting carried out to protect New Orleans.

This flood that made 700,000 homeless, over half of them black, inspired Bessie Smith (1894-1937), accompanied by James P. Johnson on piano, to write her legendary Back Water Blues, that would be later taken up by many other singers. Also guitarist Joe McCoy (prob. 1905-1950) and Memphis Minnie recorded When The Levee Breaks. In addition to these two pieces we have included here a theme on the results of a tornado: Mean Old Twister by singer/guitarist Koko Arnold (1901-1969), and another on that of a hurricane: Florida Hurricane by vocalist St. Louis Jimmy (1905-1977) backed by Sunnyland Slim on piano and Muddy Waters on guitar.

(Bessie Smith, Back Water Blues, 1927) : see lyrics in the French text

The following two tracks refer to the problems black people had with the tax system. It was especially difficult for them as they lived mainly from hand to mouth and had no savings with which to pay their taxes.

Singer/guitarist Ralph Willis (1910-1957), accompanied by Brownie McGhee complained, on Income Tax Blues of being taxed on everything he used or consumed while singer/harmonica player John Lee “Sonny Boy” Williamson (1914-1948) recounts how he had to hide when the tax collector came around.

We conclude our first CD with It’s Hard Time by singer/guitarist Joe Stone alias J.D. Short (1902-1962) which sums up the poverty endured by the Afro-American community during the Depression that followed the financial crash of 1929. The singer refers to Hooverville, the nickname of the numerous shanty towns that flourished during the time of Herbert Hoover. This was one of the rare blues recordings made in 1933, the most difficult time before the Roosevelt administration began to have an effect.

Second part

The second CD opens at an important period in American history with the election in 1932 of Franklin D. Roosevelt as President. Arriving on the heels of the Wall Street Crash and the Depression which created massive unemployment, particularly among the black community, the new president’s New Deal gradually managed to lift the country out of stagnation by a series of general work programmes. These were led by such organisations as the Civil Works Administration (C.W.A.) and the Public Works Administration (P.W.A.) and then taken over by a social services network of relief stations, welfare stations and warehouses selling cheap goods. Although affording overall help to black people, who adored Roosevelt, the system encountered several problems due to a relative reticence on the part of the president’s team in the anti-racist struggle.

The blues of this period obviously echo these events but firstly we have the posthumous homage recorded in 1960 by singer/guitarist Big Joe Williams (1903-1982) with the simple title of President Roosevelt. The following tracks underline, if only by their titles, what the blacks experienced during this period. Don’t Take Away The P.W.A. by singer Jimmie Gordon (ca. 1906 -?), W.P.A. Blues by singer/guitarist Casey Bill Weldon (1909-ca.1970), Working On The Project by singer/guitarist Peetie Wheatstraw (1902-1941) and guitarist Kokomo Arnold, Let’s Have A New Deal by singer/guitarist Carl Martin (1906-1979), Welfare Store Blues again by Sonny Boy Williamson accompanied by Joshua Altheimer on piano, and Warehouse Man Blues by singer/pianist Champion Jack Dupree (1909-1992). These singers complained about certain negative aspects of Roosevelt’s programme, in particular the closure of the relief stations and that the cheap warehouses were virtually empty: Sonny Boy said that you had to find a “real white man” to sign a docket that entitled you to a pair of worn-out shoes!

(Champion Jack Dupree, Warehouse Man Blues, 1940) : see lyrics in the French text

However, these problems did not prevent an outpouring of emotion on from the black community when Roosevelt died in 1945 and they now pinned their hopes on the new president Harry Truman, most of whom continued to support the Democrats but the latter lost the elections in 1952 when Eisenhower came to power. Even Champion Jack Dupree was inspired to write a funeral oration entitled F.D.R. Blues, followed by best wishes to Truman on God Bless Our New President – which he later regretted! – as well as vocalist Herman Ray (1914-?), backed by Sammy Price, on President’s Blues on which he compared Truman to Lincoln and Roosevelt. On the other hand, Eisenhower’s Blues by J.B. Lenoir (1929-1967) was banned in 1954 as too critical of the then president.

(Champion Jack Dupree, F.D.R. Blues, 1945) : see lyrics in the French text

Following the end of the Second World War in 1945, the so-called Cold War began between the United States and the Soviet Union, leading to real war in Korea and Vietnam. New “recruitment” blues began to surface: Korea Blues by J.B. Lenoir and Sunnyland Slim (1907-1995) on piano, the latter also providing the vocal on Back To Korea with Snooky Pryor on harmonica.

In addition to the Korean War, the Cold War also gave rise to several blues referring to world-wide anxiety about an atomic war. On Crazy World, singer/pianist Julia Lee (1902-1958) sang about these concerns, preaching the need for universal love. On a more serious note, singer/guitarist Jimmy Rogers (1924-1997) declared on The World Is In A Tangle that people would have to dig a cellar to hide themselves in.

(Jimmy Rogers, The World Is In A Tangle, 1951) : see lyrics in the French text

The next two pieces are entitled Hard Times and are interpreted first by Ida Cox (1889-1967) and then singer/pianist Charles Brown (1922-1999). Cox’s lyrics are particularly striking as she speaks of being besieged in her cabin by hungry wolves. Even in the time of Roosevelt, things were hard for black Americans.

(Ida Cox, Hard Times, 1939) : see lyrics in the French text

The on-going themes of poverty, loneliness and enforced wandering endured by the black population are ever present on tracks by such singer/guitarists as Eddie Kirkland (1928-2011), Baby Boy Warren (1919-1977) on Lonesome Cabin Blues, and Brownie McGhee on Poor Boy. The latter, alongside his partner Sonny Terry (1911-1986) on harmonica, adds the theme of having to borrow money on Pawnshop Blues.

The following track The Alabama Bus, by factory worker and preacher Brother Will Hairston (1919-1988), echoing the style of a Negro spiritual, describes events that took place in 1955 and 56 in Montgomery, capital of Alabama where racial segregation was paramount, particularly on buses where Afro-Americans had to sit at the back and whites in front. If a white person was standing he had the right to force a black person to give up his/her seat. On 1 December 1955 a woman, Rosa Parks, refused on the spur of the moment to give up her seat to a young white man. Called in by the bus driver, the police arrested her and she was sent for trial. Alerted by black associations and churches, including that headed by Martin Luther King, Afro-Americans decided to boycott buses as long as they applied this segregation policy. (11)

After almost a year this boycott, led principally by Reverend King, the American Supreme Court upheld the black community in a judgement dated 13 November 1956. These events accelerated racial desegregation – with some resistance! – in the southern states from 1960 onwards.

Martin Luther King himself became a national figure at the head of the Civil Rights movement earlier signs of which had, moreover, already been evident or hinted at in our blues selection. His position was further reinforced by the March on Washington in 1963. After receiving the Nobel Peace Prize the following year, Dr. King paid with his life for his non-violent actions when he was assassinated by a white man in Memphis in 1968.

Three years after the events in Montgomery the United States embarked on the electoral campaign to elect a new president at the end of 1960. Singer/guitarist John Lee Hooker (1917-2001) participated in his own way in this campaign with Democrat Man, proclaiming his faith in the Democrat Party and reproaching women for having helped defeat this party in previous votes that had seen Republican Dwight Eisenhower elected twice. He appealed to them not to make the same mistake this time round.

In fact, Democrat John F. Kennedy won over Richard Nixon, a victory which was greeted with joy by the black community. With his usual sardonic humour singer/pianist Memphis Slim (1915-1988) on The Big Race lauded the victory of the “Donkey” over the “Elephant”.

(Memphis Slim, The Big Race, 1960) : see lyrics in the French text

Kennedy did not have enough time, before he was assassinated in 1963, to implement all his programmes and it was his successor Lyndon B. Johnson who abolished racial segregation in 1964… officially that is although not in the attitude and behaviour of many Americans.

Alas, these achievements were overshadowed during the 60s, not only by the death of John Kennedy but also by racial riots and confrontations and, in particular by the assassination of Martin Luther King (not forgetting those of Malcolm X and Robert Kennedy).

Nevertheless, the door had been opened for a march towards civil rights for all Americans, whatever their colour or creed. But there was still a long way to go … until something incredible happened nearly forty years later, the election of a black man, Barack Obama, to the presidency!

Despite this, several recent developments were a dramatic reminder that this “equality” was still far from being achieved.

Adapted by Joyce Waterhouse from the French text of Jean Buzelin & Jacques Demêtre

© 2014 FRÉMEAUX & ASSOCIÉS

Notes

(1) While a number of historians, musicologists and observers of popular black music and blues in particular share the same opinion, that of LeRoi Jones (Amiri Baraka, 1934-2014) carries undeniable weight, the author being very closely connected with the Afro-American community since the 60s.

(2) Paul Oliver, Blues Feel this Morning, (Cassell, London, 1960).

(3) With one notable exception, Cow Cow Davenport’s Jim Crow Blues recorded in 1927.

(4) Field recordings, carried out mainly by John and Alan Lomax for the Library of Congress, did not have this worry and amateur singers could express themselves more freely as these recordings were not intended to be issued commercially.

(5) Jaques Demêtre, Evènements & Figures historiques à travers les chants populaires noirs (Jazz Hot n° 345/46-347-348, January-February-March 1978).

(6) Robert Springer, Fonctions sociales du blues (Parenthèses, 1999).

(7) Giles Oakley, Devil’s Music, (Da Capo Press, 1976).

(8) See their respective stories and struggles in Gérard Herzhaft’s sleeve notes: Lead Belly (FA 269) and Josh White (FA 264).

(9) Not forgetting such great black artistes as Paul Robeson and Marian Anderson.

(10) William Lee Conley Broonzy & Yannick Bruynoghe, Big Bill Blues (Cassell, London, 1955).

(11) The Alabama Bus is recognized as being the first record to feature the name of Martin Luther King:

“I wanna tell you ‘bout the Reverend Martin Luther King

You know, they tell me that the people began to sing

You know, the man God sent out into the world,

You know, they tell me that man had the mighty nerve”.

Photos & collections : Jacques Demêtre (1959), Frank Driggs, X (D.R.); Edwin Rosskam, John Vachon, Walker Evans, Jack Delano (Library of Congress).

We thanks for their help to Patrice Buzelin, Jean-Paul Levet and Nicolas Teurnier.

DISCOGRAPHIE CD 1

1. DEFENSE FACTORY BLUES (W. Cuney - J. White) QB-1687

2. UNCLE SAM SAYS (W. Cuney - J. White) QB-1690

3. MILLION LONESOME WOMEN (W.B. McGhee) C-3791-1

4. YOU BETTER BE READY TO GO (H. Whittaker) 064187

5. UNCLE SAM CAME AND GET IT (P. Grainger) 70545-A

6. THE NUMBER OF MINE (W.L.C. Broonzy) WC-3510-1

7. GET BACK (BLACK, BROWN AND WHITE) (W.L.C. Broonzy) C 4385

8. CELL N°13 BLUES (W.L. Broonzy) 4523

9. COUNTY JAIL BLUES (M. Merriweather) 064192-1

10. NO JOB BLUES (W. Thomas) 20343-2

11. THERE IS NO JUSTICE (W.L.C. Broonzy) 152143-1

12. PARCHMAN FARM BLUES (W. White) WC-2981-A

13. I’M PRISON BOUND (DOIN’ TIME BLUES) (L. Carr)

14. PENITENTIARY BLUES (Trad. - arr. S. Hopkins)

15. THE BOURGEOIS BLUES (H. Ledbetter - A. Lomax) GM-504

16. JIM CROW (BLUES) (H. Ledbetter)

17. JIM CROW TRAIN (W. Cuney)

18. BACK-WATER BLUES (B. Smith) 143491-1

19. WHEN THE LEVEE BREAKS (J. McCoy) 148711-1

20. MEAN OLD TWISTER (J. Arnold) 91161-A

21. FLORIDA HURRICANE (J.B. Oden) UB 9290A

22. INCOME TAX BLUES (R. Willis) 4462

23. COLLECTOR MAN BLUES (J.L. Williamson) 016521

24. IT’S HARD TIME (J. Stone [= J.D. Short]) 76837

(1-2) Joshua White g, vo). New York City, NY, 1941.

(3) Brownie McGhee (as Blind Boy Fuller #2) (g, vo), Jordan Webb (ha). Chicago, IL, 23/05/1941.

(4) Tampa Red (g, vo, kazoo), Big Maceo (p), Ransom Knowling (b). Chicago, 24/01/1941.

(5) Wee Bea Booze (g, vo), Sam Price (p), unknown (b)(dm). NYC, 10/03/1942.

(6) Big Bill (Broonzy) (g, vo), prob. Memphis Slim (p), Ransom Knowling (b). Chicago, 17/12/1940.

(7) Big Bill Broonzy (g, vo), Ransom Knowling (b). Chicago, 08/11/1951.

(8) Big Bill (Broonzy) (g, vo), Buster Bennett (as), Big Maceo (p), Tyrell Dixon (dm). Chicago, 19/02/1945.

(9) Big Maceo (p, vo), Tampa Red (g). Chicago, 24/06/1941.

(10) Ramblin’ Thomas (g, vo). Chicago, ca. 02/1928.

(11) Jimmy Jordan (Lonnie Johnson) (g, vo). NYC, 17/03/1932.

(12) Bukka White (g, vo), Washboard Sam (wbd). Chicago, 07/03/1940.

(13) Lowell Fulson (g, vo), Martin Fulson (g). Oakland, CA, 1948.

(14) Lightnin’ Hopkins (g, vo). Houston, TX, 16/01/1959.

(15) Huddie Ledbetter (Lead Belly) (g, vo). NYC, 01/04/1939.

(16) Lead Belly (g, vo). NYC, 05/1944.

(17) Josh White (g, vo), Al Hall (b), Sonny Greer (dm). NYC, 21/12/1956.

(18) Bessie Smith (vo), James P. Johnson (p). NYC, 17/12/1927.

(19) Kansas Joe & Memphis Minnie: Joe McCoy (g, vo), Memphis Minnie (g). NYC, 18/06/1929.

(20) Kokomo Arnold (g, vo). Chicago, 30/03/1937.

(21) St. Louis Jimmy (vo) with Muddy Waters & His Blues Combo: Oliver Alcorn (ts), Sunnyland Slim (p), Muddy Waters (g), Ernest “Big“ Crawford (b). Chicago, ca. 09/1948.

(22) Ralph Willis (g, vo) feat. Brownie McGhee (g), Dumas Ransom (b), unknown (dm). NYC, 18/01/1951.

(23) Sonny Boy Williamson (ha, vo), prob. Walter Davis (p), prob. Robert Lee McCoy and Henry Townsend (g). Aurora, IL, 11/11/1937.

(24) Joe Stone (J.D. Short) (g, vo). Chicago, 02/08/1933.

DISCOGRAPHIE CD 2

1. PRESIDENT ROOSEVELT (J.L. Williams)

2. DON’T TAKE AWAY MY P.W.A. (J. Gordon) 90917

3. W.P.A. BLUES (W. Weldon - L. Melrose) C-1256-1

4. WORKING ON THE PROJECT (W. Bunch [= P. Wheatstraw]) 91164-A

5. LET’S HAVE A NEW DEAL (C. Martin) 90294-A

6. WELFARE STORE BLUES (J.L. Williamson) 053001

7. WAREHOUSE MAN BLUES (J. Dupree) WC-3109-A

8. F.D.R. BLUES (J. Dupree) 5102-A

9. GOD BLESS OUR NEW PRESIDENT (J. Dupree) 5102-B

10. PRESIDENT’S BLUES (H. Ray) W 74937

11. EISENHOWER BLUES (J.B. Lenoir) P 53203-5

12. KOREA BLUES (J.B. Lenoir) JB 31644

13. BACK TO KOREA BLUES (A. Luandrew) EOCB 4504

14. CRAZY WORLD (R. Burns) 2460-2

15. THE WORLD IS IN A TANGLE J.A. Lane [= J. Rogers]) U 7308

16. HARD TIMES BLUES (I. Cox) 26241-A

17. HARD TIMES (J. Leiber - M. Stoller) RR 1752-3

18. NO SHOES (E. Kirkland) K 9306-2

19. LONESOME CABIN BLUES (R.H. Warren) RW 707A

20. POOR BOY BLUES (W.B. McGhee) S 3459

21. PAWNSHOP BLUES (W.B. McGhee)

22. THE ALABAMA BUS Pt. 1 & 2 (W. Hairston)

23. DEMOCRAT MAN (J.L. Hooker)

24. THE BIG RACE (P. Chatman)

(1) Big Joe Williams (g, vo). Los Gatos, CA, 05/10/1960.

(2) Jimmie Gordon (vo), prob. Horace Malcolm (p), Joe or Charlie McCoy (g), Harrison (b). Chicago, 02/10/1936.

(3) Casey Bill (g, vo), Black Bob (p), Bill Settles (b). Chicago, 12/02/1936.

(4) Peetie Wheatstraw (p, vo), Kokomo Arnold (g). Chicago, 30/03/1937.

(5) Carl Martin (g, vo), Willie Bee James (g). Chicago, 04/09/1935.

(6) Sonny Boy Wiliamson (ha, vo), Joshua Altheimer (p), Fred Williams (dm). Chicago, 17/05/1940.

(7) Champion Jack Dupree (p, vo), Wilson Swain or Ransom Knowling (b). Chicago, 13/06/1940.

(8-9) Champion Jack Dupree (p, vo). NYC, 18/04/1945.

(10) Herman Ray (vo), J.T. Brown (ts), Sam Price (p), Lonnie Johnson (g), unknown (b)(dm). NYC, 20/05/1949.

(11) J.B. Lenoir (g, vo), Lorenzo Smith (ts), Joe Montgomery (p), Al Galvin (dm). Chicago, ca. 04/1954.

(12) J.B. Lenoir (g, vo), Sunnyland Slim (p), Leroy Foster (g), Alfred Wallace (dm). Chicago, late 1950.

(13) Sunnyland Slim (p, vo), Snooky Pryor (ha), Leroy Foster (g). Chicago, ca. 10/1950.

(14) Julia Lee (p, vo) & Her Boy Friends: Vic Dickenson (tb), Benny Carter (as), Dave Cavanaugh (ts), Jack Marshall (g), Billy Hadnott (b), Sam “Baby“ Lovett (dm). Los Angeles, 13/11/1947.

(15) Jimmy Rogers (g, vo) & His Rocking Four: Ernest Cotton (ts), Eddie Ware (p), Big Crawford (b), Elgar Edmonds (dm). Chicago, 23/01/1951.

(16) Ida Cox (vo) & Her All-Star Band: Oran “Hot Lips“ Page (tp), J.C. Higginbotham (tb), Edmond Hall (cl), Fletcher Henderson (p), Charlie Christian (g), Artie Bernstein (b), Lionel Hampton (dm). NYC, 31/10/1939.

(17) Charles Brown (p, vo) & His Band: Maxwell Davis (ts), Jesse Ervin (g), Wesley Prince (b), Lawrence Marable (dm). Los Angeles, 24/09/1951.

(18) Eddie Kirkland (g, vo), Ray Brown (dm). Cincinnati, OH, 23/07/1953.

(19) Baby Boy Warren (g, vo) & His Buddy: Charlie Mills (p). Detroit, 1949.

(20) Brownie McGhee (g, vo), Melvin Merritt (p), unknown (b), Arthur Herbert (dm). 20/10/1947.

(21) Brownie McGhee (g, vo) & Sonny Terry (ha). Englewoods Cliffs, NJ, 22/08/1960.

(22) Brother Will Hairston (vo), unknown (p), Washboard Willie (wbd). Detroit, ca. 1956.

(23) John Lee Hooker (g, vo). NYC, 09/02/1960.

(24) Memphis Slim (p, vo), Arbee Stidham (g), Armand “Jump“ Jackson (dm). Chicago, 10/1960.

Né avec la ségrégation, le blues a accompagné tous les évènements politiques et sociaux du XXe siècle aux États-Unis, et témoigné des réactions du peuple afro-américain face au racisme, à la misère, à la faim, au chômage, à la prison… De la Grande Dépression à la lutte pour les droits civiques, Jean Buzelin et Jacques Demêtre ont dressé un choix de thèmes qui abordent le New Deal, les guerres, les catastrophes naturelles, le vote, et tous les problèmes quotidiens auxquels est confrontée la communauté noire au sein de l’Amérique blanche.

Patrick FRÉMEAUX

With its roots in segregation, the blues echoed all the political and social events of the 20th century in the United States, and bore witness to the reactions of Afro-Americans to racism, poverty, hunger, unemployment, prison… Beginning with the Depression up to the Civil Rights struggle, Jean Buzelin and Jacques Demêtre have put together a series of themes touching on the New Deal, wars, natural catastrophes, elections and all the daily problems confronting the black community which has still not found its rightful place within American white society.

Patrick FRÉMEAUX