- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

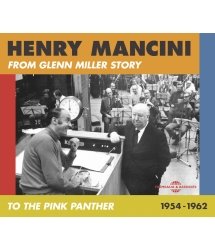

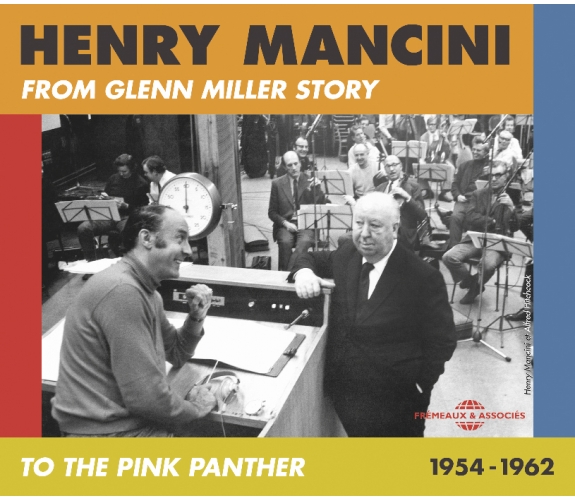

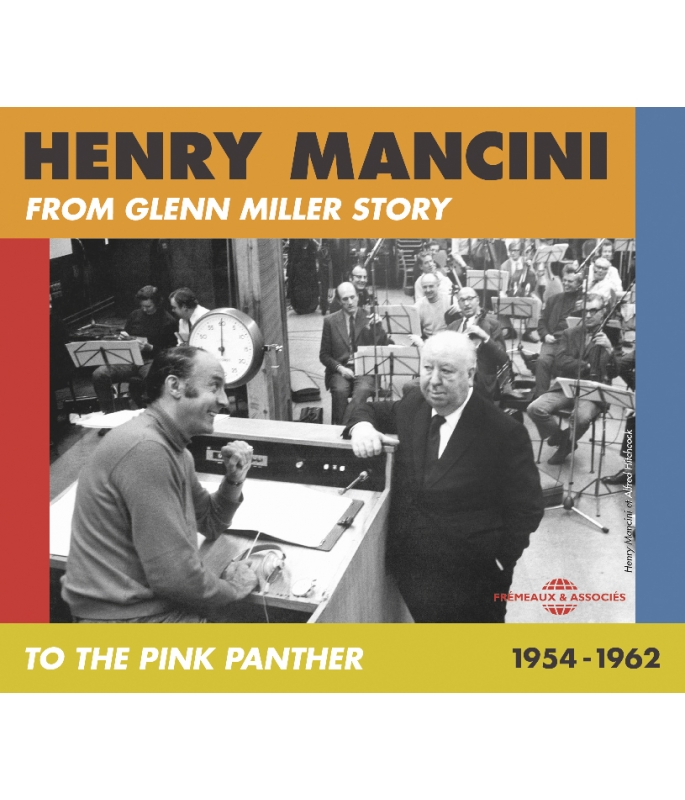

FROM GLENN MILLER STORY TO THE PINK PANTHER 1954-1962

HENRY MANCINI

Ref.: FA5499

Artistic Direction : ALAIN TERCINET

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Total duration of the pack : 2 hours 31 minutes

Nbre. CD : 2

FROM GLENN MILLER STORY TO THE PINK PANTHER 1954-1962

FROM GLENN MILLER STORY TO THE PINK PANTHER 1954-1962

“Up until that time, film scoring was almost entirely derived from European symphonic composition. Mancini changed all that.” Gene LEES

ANTHOLOGIE DES BANDES ORIGINALES 1960-1998

ASCENSEUR POUR L’ÉCHAFAUD, A BOUT DE SOUFFLE, UNA...

PREMIER CHAPITRE 1954-1961 (UN TEMOIN DANS LA...

Michel Magne, Nino Rota, Georges Delerue, Maurice...

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Free And EasyHenry Mancini And Unidentified Orchestra00:01:541956

-

2Borderline MontumaJoseph And Gershenson Universal International Orchestra00:02:031958

-

3Lease BreakerJoseph And Gershenson Universal International Orchestra00:02:461958

-

4Blue (Angel) PianolaR. Sherman00:03:121958

-

5Peter GunnHenry Mancini And His Orchestra00:02:081958

-

6DreamsvilleHenry Mancini And His Orchestra00:03:571958

-

7The FloaterHenry Mancini And His Orchestra00:03:191958

-

8A Profond GassHenry Mancini And His Orchestra00:03:221958

-

9Not From DixieHenry Mancini And His Orchestra00:04:121958

-

10My Man ShellyHenry Mancini And His Orchestra00:02:411958

-

11The Little Man ThemeHenry Mancini And His Orchestra00:03:181959

-

12Spook !Henry Mancini And His Orchestra00:03:011959

-

13Mr. LuckyHenry Mancini And His Orchestra00:02:161959

-

14That's It And That's AllHenry Mancini And His Orchestra00:02:561959

-

15SiestaHenry Mancini And His Orchestra00:02:531961

-

16A Mild BlastHenry Mancini And Unidentified Orchestra00:03:111960

-

17New BloodHenry Mancini And Unidentified Orchestra00:02:491960

-

18The Dean SpeaksHenry Mancini And Unidentified Orchestra00:02:391960

-

19Moon RiverHenry Mancini And His OrchestraJohnny Mercer00:01:541960

-

20Hub Caps And Tail LightsHenry Mancini And His Orchestra00:02:341961

-

21The Big HeistHenry Mancini And His Orchestra00:03:141961

-

22Experiment In TerrorHenry Mancini And His Orchestra00:02:201962

-

23Kelly's TuneHenry Mancini And His Orchestra00:03:201962

-

24Baby Elephant WalkHenry Mancini And His Orchestra00:02:451961

-

25Big Band BwanaHenry Mancini And His Orchestra00:03:041961

-

26Crocodile, Go Home !Henry Mancini And His Orchestra00:02:551961

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Dancer's DelightTex Beneke And His Orchestra00:03:091951

-

2Too Little TimeThe Original Reunion Of The Glenn Miller Band00:02:551954

-

3What's It Gonna BeThe Four FresmenB. Carey00:01:461957

-

4The Peter Gunn ThemeRay Anthony And His Orchestra00:01:521958

-

5Brief And BreezyLola Albright - Henry ManciniS. Cahn00:03:181959

-

6Slow And EasyLola Albright - Henry ManciniS. Cahn00:02:341959

-

7Straight To BabyLola Albright - Henry ManciniJ. Livingston00:02:521959

-

8Sorta BlueLola Albright - Henry ManciniS. Cahn00:02:591959

-

9PolitelyHenry Mancini And His Orchestra00:03:191959

-

10Let's WalkHenry Mancini And His Orchestra00:03:071959

-

11A Cool Shade Of BluesHenry Mancini And His Orchestra00:03:491959

-

12Robbin's NestHenry Mancini And His OrchestraE. Thompson00:03:411959

-

13The BluesHenry Mancini And His Orchestra00:02:421960

-

14Blue FlameHenry Mancini And His OrchestraJ. Bishop00:02:471960

-

15After HoursHenry Mancini And His OrchestraE. Hawkins00:03:091960

-

16The BeatHenry Mancini And His Orchestra00:03:101960

-

17Tippin' InHenry Mancini And His OrchestraB. Smith00:03:481960

-

18How Could You Do A Thing Like That To Me ?Henry Mancini And His OrchestraT. Glenn00:03:341960

-

19Moanin'Henry Mancini And His Orchestra00:02:531960

-

20Swing LightlyHenry Mancini And His Orchestra00:04:191960

-

21A Powedered WigHenry Mancini And His Orchestra00:02:401960

-

22Far East BluesHenry Mancini And His Orchestra00:03:301960

-

23Everybody Blow !Henry Mancini And His Orchestra00:03:241960

-

24Days Of Wine And RosesHenry Mancini And His OrchestraJohnny Mercer00:02:101962

-

25The Pink Panther ThemeClaude Bolling Big Band00:03:041995

Mancini FA5499

HENRY MANCINI

From Glenn Miller Story

to The Pink Panther

1954-1962

HENRY MANCINI

From “Glenn Miller Story” to “The Pink Panther”

1954 – 1962

«C’était The Crusades de Cecil B. De Mille. Je n’avais jamais vu un film parlant, seulement les comédies muettes de Charlie Chase, Buster Keaton, Laurel et Hardy, Charlie Chaplin et les Keystone Cops. Ce dont je me souviens le plus de cette journée, c’est la musique, le son d’un grand orchestre. Je n’avais jamais entendu quelque chose comme ça, seulement la musique des concerts donnés par l’orchestre des Sons of Italy dans lequel je jouais de la flûte et du piccolo […] Je croyais qu’il y avait une grande formation derrière l’écran […] Il [mon père] me dit que le son de l’orchestre faisait partie intégrante du film […] J’ai su ce que je ferai quand j’aurai grandi. J’écrirai de la musique pour les films (1). »

Enrico Nicola Mancini avait onze ans lorsque, durant l’hiver 1935, son père l’avait emmené à Pittsburgh voir « The crusades » (Les croisades). La munificence d’une partition de Rudolph G. Kopp, viennois d’origine et admirateur de Richard Wagner, lui avait révélé un univers qu’il allait faire sien. La découverte du jazz viendra trois ans plus tard, grâce à un orchestre afro-américain – trois trompettes, deux trombones, cinq saxes et une section rythmique – qui s’exprimait, se souviendra-t-il, dans un style proche de Fletcher Henderson et de Count Basie.

Les années d’apprentissage musical d’Henry Mancini se résumèrent essentiellement à une pratique du piano et à la dissection de disques d’Artie Shaw et de Benny Goodman en raison d’une passion naissante pour l’arrangement. « Par chance, depuis le collège, j’ai été capable de subvenir à mes besoins grâce à la musique. Même durant ces années-là, j’avais l’habitude de jouer beaucoup. Je me faisais à chaque fois deux ou trois dollars. Mariages polonais, mariages italiens. J’ai grandi en Pensylvanie dans un endroit nommé Aliquippa où la totalité des groupes ethniques européens étaient représentés et je jouais dans tous les mariages. Vous pouviez manger tout ce que vous vouliez et vous receviez un ou deux dollars (2) ».

Admis à la Juilliard School en 1942, Henry Mancini eut juste le temps d’y découvrir la musique de Ravel et de Debussy avant d’être enrôlé dans l’armée de l’air. Grâce à Glenn Miller, il fut versé dans le 28th Air Force Band, échappant ainsi à une affectation de mitrailleur sur un B-27.

Saxophoniste ténor et chanteur très apprécié dans la formation que dirigea Glenn Miller avant-guerre, Tex Beneke décida de la faire revivre, avec l’assentiment de la veuve du chef d’orchestre disparu. Un an après les débuts de l’ensemble en janvier 1946, Henry Mancini fut engagé en tant que pianiste et arrangeur puis, à sa demande, comme arrangeur seulement : son Dancer’s Delight n’avait rien à envier aux partitions que Jerry Gray concoctait pour la formation d’origine. La fréquentation quotidienne de ses pairs lui permit de jauger leurs capacités. Par la suite, pour son propre compte, il fera appel en toute connaissance de cause à quelques-uns d’entre eux.

Grâce à Skip to My Lou arrangé pour l’orchestre de Jimmy Dorsey, Mancini fut pris à l’essai chez Universal Pictures alors à la recherche d’un spécialiste de l’écriture pour orchestre de danse. Entré pour deux semaines, il resta cinq ans dans l’équipe d’arrangeurs-orchestrateurs-compositeurs polyvalents attachée au studio. En compagnie d’Herman Stein - un merveilleux musicien à ses dires -, il travailla sur une quantité de séries B, pour ne pas dire de séries Z. À l’image de la « Creature of the Black Lagoon » où un homme-poisson, visiblement épris de l’actrice Julie Adams, passait son temps à grimper à babord du bateau des explorateurs qui le guettaient à tribord ; ou vice et versa. Il y eut une suite, « Revenge of the Creature », dans laquelle Mancini était encore partie prenante. Parmi les figurants, un certain Clint Eastwood en laborantin maladroit.

Henry Mancini, à l’évidence l’homme de la situation, fut chargé en 1953 de vérifier les partitions originales qui devaient être utilisées dans le film « The Glenn Miller Story ». En s’acquittant de sa tâche, il constata l’absence d’une mélodie susceptible d’accompagner les moments d’intimité des deux principaux personnages. Il composa alors Too Little Time qui, utilisé dans le film, ne figure dans aucun des albums reproduisant la bande originale. À l’occasion de la sortie de « The Glenn Miller Story », Too Little Time fut interprété au cours d’un concert donné, au Shrine Auditorium de Los Angeles, par les anciens de l’orchestre dirigés par Billy May.

Le film d’Anthony Mann ayant rencontré un succès inattendu, Universal décida d’exploiter le filon, mettant en chantier « The Benny Goodman Story », avec, à nouveau, Henry Mancini comme superviseur musical. Un rôle qu’il tenait tout autant dans une production nettement moins prestigieuse,« Rock Pretty Baby ». Sorti sur les écrans en 1956, la même année que « The Benny Goodman Story », ce film dont la vedette était Sal Mineo, célébrait la génération Rock’n’Roll. Mancini en profita pour y glisser plusieurs thèmes de sa composition dont Free and Easy qui, avec des paroles dues à Bobby Troup, obtint un joli succès et What’s It Gonna Be. Interprété à l’écran par Jim Daley and the Ding-A-Lings, il fut repris - pour le meilleur - par The Four Freshmen.

En 1958 fut confiée à Henry Mancini une tâche qui, pour passionnante qu’elle fut, était parsemée de chausse-trapes : composer la musique de « Touch of Evil ». Un film noir, mis en scène et interprété par Orson Welles qui, d’emblée, savait ce qu’il voulait pour chaque composant du film. Y compris la musique. « Il comprenait vraiment en quoi consistait une bande sonore. Comme il faisait un film résolument réaliste, j’ai pensé qu’il voudrait que la musique elle-même soit ancrée dans la réalité. Ce qui signifiait que son émergence devait être justifiée par le scénario (3). »

Welles avait adressé à Joseph Gershenson, directeur du département musical d’Universal, un nombre conséquent de mémos exposant ses exigences. L’intrigue, située dans une petite ville sise à la frontière entre les Etats-Unis et le Mexique, exigeait le recours à diverses formes de musiques latino-américaines. Pour certaines séquences, le rock’n’roll alors à la mode s’imposait. Les notes précisaient même la couleur musicale à utiliser selon les scènes ainsi que l’instrumentation adéquate.

Orson Welles aurait approuvé, dit-on, ce que Mancini avait composé bien qu’il ne l’entendit pas en situation. Exclu du montage, s’estimant trahi de ce fait, il refusa de visionner « Touch of Evil ». En 1998, une nouvelle version, basée sur ses notes, tenta de rétablir sa version. Dans la mesure du possible…

Henry Mancini considéra toujours son travail sur « Touch of Evil » comme l’un des meilleurs qu’il ait signé. Accompagnant le magnifique plan-séquence d’ouverture, Borderline Montuma installe d’emblée l’atmosphère. Écho à la violence du gang de jeunes mexicains, Lease Breaker donne la parole au saxophoniste Plas Johnson pour un solo fleurant bon le rythm’n’blues. Est-ce Mancini, est-ce Welles, qui eut l’idée de lier le son d’un piano mécanique aux apparitions de Tanya/Marlène Dietrich ? Rien ne pouvait mieux souligner la singularité du personnage que The Blue (Angel) Pianola.

« Bien que d’autres aient utilisé avant lui des éléments de jazz dans les bandes sonores de film, c’est Mancini qui ouvrit la voie à une utilisation complète de cette musique dans un drame […] Il fit découvrir à un large public, et aux têtes pensantes de l’industrie de la communication, l’extraordinaire gamme expressive de cette musique (4). » Johnny Mandel, auteur de la musique de « I Want to Live », confirma l’affirmation de Gene Lees. Il reconnut que la partition composée par Henry Mancini pour « Touch of Evil » lui avait grandement facilité la tâche vis-à-vis de ses producteurs.

Gene Lees : « Jusqu’à cette période, la musique de film s’inspirait presque entièrement de la musique symphonique européenne. Mancini a changé cela. Plus que quiconque, il a « américanisé » la musique de film et, du coup, même les compositeurs européens lui ont emboîté le pas (5) ». Venus de Vienne pour la plupart, Erich Wolfgang Korngold, Franz Waxman, Max Steiner ou Rudolph G. Kopp tenaient alors le haut du pavé à Hollywood. Compositeurs classiques à l’origine, ils avaient imposé un style d’accompagnement se refusant à la moindre référence directe à la musique populaire. Mancini allait tout changer.

En premier lieu, au moment d’enregistrer la musique de « Touch of Evil », il avait prévenu Joseph Gershenson que l’orchestre du studio serait incapable d’exécuter ses partitions de manière satisfaisante. En conséquence, il engagea Pete Candoli, Conrad Gozzo, Rollie Bundock - il les avait côtoyés chez Tex Beneke - ainsi que Plas Johnson, Bob Bain, Shelly Manne. Au fil des productions, les rejoindront Ted et Dick Nash, Vince de Rosa, Ronnie Lang, Larry Bunker, Vic Feldman, Jimmie Rowles qui, au piano, succédera à John Towner Williams, futur compositeur de « Star Wars », « Indiana Jones » et « Saving Private Ryan ». Liés de plus ou moins près au jazz West Coast, ils constituèrent un noyau fixe qui donnait aux orchestres réunis par Henry Mancini un son bien spécifique.

Durant ses « années Universal » qui venaient de s’achever à la suite de la vente du studio à MCA, Mancini avait sympathisé avec Blake Edwards. Scénariste et metteur en scène, ce dernier lui proposa alors de travailler sur une série policière conçue pour la télévision, « Peter Gunn » (6).

Henry Mancini : « L’idée d’utiliser le jazz dans la musique d’accompagnement ne fut jamais mise en question. C’était inhérent à l’histoire. Peter Gunn fréquentait une boîte appelée « Mother’s » où se produisait un quintette. Dans l’épisode pilote, cinq ou six minutes s’y déroulaient. Il était donc évident que le jazz devait être utilisé. C’était l’époque du soit-disant « jazz cool » de la West Coast avec Shelly Manne, les frères Candoli et Shorty Rogers parmi d’autres. Ce fut cette ambiance sonore qui me vint naturellement à l’esprit, « walking bass » et batterie. En fait, le thème de « Peter Gunn » découle plus du rock’n’roll que du jazz. J’ai utilisé une guitare et un piano jouant à l’unisson ce que l’on appelle en musique un « ostinato » qui signifie « obstiné ». Il persiste durant tout le morceau, installant un climat d’angoisse que ponctue quelques interventions de saxophone et des éclats de cuivres (7). »

Sur le petit écran, en accord avec la mise en scène de Blake Edwards - contrairement à nombre de séries policières de l’époque, « Peter Gunn » conserve aujourd’hui son efficacité -, le jazz tenait une place prépondérante. Au fil des épisodes, Vic Feldman, Bob Bain, Rollie Bundock et même Shorty Rogers dans l’épisode « The Frog », apparaissaient à l’écran. Les intrigues amenaient souvent Peter Gunn à franchir les portes d’autres clubs et, parfois, dans « Streetcar Jones » par exemple, la musique elle-même en constituait le ressort.

À l’issue d’une projection de l’épisode pilote, Alan Livingstone, très au fait de l’industrie du disque, suggéra à RCA de publier la musique de « Peter Gunn ». Consacrer un album lié à une série télévisée n’étant guère dans ses habitudes, la compagnie phonographique fit la sourde oreille.

Ray Anthony venait de faire un tube du thème de « Dragnet », une autre feuilleton. Connaissant bien Blake Edwards, il lui proposa d’enregistrer celui de « Peter Gunn » arrangé par son auteur. Le succès rencontré finit par décider RCA.

L’usage de la stéréophonie s’étant généralisé sur le marché du disque, il fallait tout ré-enregistrer. Le nom d’Henry Mancini était inconnu du public. En haut lieu, la décision fut prise de s’adresser à quelqu’un ayant le vent en poupe, Shorty Rogers qui, par honnêteté, refusa. C’était l’œuvre de Mancini, il l’avait composée, la connaissait mieux que personne, il devait donc la diriger.

Mancini se vit offrir un contrat valable pour un seul album, RCA s’arrogeant le droit de fixer le nombre d’exemplaires à presser, en l’occurrence 800. En moins d’une semaine, ils étaient vendus…

Les albums « Music from Peter Gunn » et « More Music from Peter Gunn » reprenaient en studio les thèmes interprétés fragmentairement par le quintette du « Mother’s » ou accompagnant certaines séquences. Mancini y prenait un malin plaisir à varier les atmosphères. Dreamsville évoquait Gil Evans et Soft Sounds saluait le Modern Jazz Quartet. Les claquements de doigts sur The Floater recréaient l’ambiance d’un cabaret et My Man Shelly rendait hommage à Shelly Manne, figure majeure du jazz californien et complice de Mancini au fil des ans (8). Les parties orchestrales jouées en grande formation étaient marquées par l’influence de Stan Kenton ; une empreinte présente d’ailleurs sur nombre de bandes sonores.

Cité onze fois aux Grammy Awards en 1959, « Music from Peter Gunn » en reçut deux en tant que « Meilleur album de l’année » et « Meilleur arrangement ». Aux Emmy Awards, il avait été sélectionné dans la catégorie « Meilleure musique de film de la saison ». Quant au thème de « Peter Gunn », au fil des ans, il se déclinera en plus de cinquante versions (9).

Un autre feuilleton télévisé réunissait également Blake Edwards et Henry Mancini, « Mr. Lucky ». Il se déroulait, lui, dans une contrée exotique imaginaire dont Siesta, dévolu à Laurindo Almeida, rendait l’ambiance. Le jazz ne pouvant y trouver place qu’à la portion congrue, That’s It and That’s All est l’un des rares exemples de son utilisation dans « Mr. Lucky ». Par contre, comme ce fut le cas pour « Peter Gunn », son thème générique servira de tremplin à un nombre impressionnant de jazzmen.

En 1957, à l’époque de « Rock, Pretty Baby », Mancini avait signé l’album « Driftwood and Dreams », réédité sous le titre « The Versatile Henry Mancini ». Un exercice de style qui témoignait du goût de son signataire pour les mélanges sonores inhabituels. Deux ans plus tard, « The Mancini Touch » fera appel à vingt cordes, quatre cors, quatre trombones, cinq rythmes - dont un vibraphone - plus Ted Nash au saxophone alto et Ronnie Lang à la flûte alto (au baryton sur Robbin’s Nest). Une instrumentation insolite qui mettait en valeur des compositions originales comme Politely et A Cool Shade of Blue.

Il faut dire que Billboard, la bible de l’industrie phonographique, avait qualifié la formation réunie pour l’enregistrement de « Music from Peter Gunn » de « The most promising band of the year ». Henry Mancini avait donc eu toutes les facilités pour diriger une séance consacrée à ses arrangements de pièces sans rapports directs avec le petit ou le grand écran. La première d’une longue série dont fera partie « The Blues and the Beat ».

Dans son texte de pochette, Mancini affirmait que l’essence du jazz se résumait à ces deux composants. À chacun d’eux était consacré une face de l’album, un thème original introduisant chaque fois cinq classiques du répertoire. The Blues amenait Blue Flame et After Hours, tandis que The Beat annonçait Tippin’ In et How Could You Do A Thing Like That To Me ?

Pour être en accord avec le titre choisi pour son LP suivant, « Combo ! », Mancini réunira dix de ses jazzmen préférés et Art Pepper… à la clarinette (Moanin’, Swing Lightly). John T. Williams s’y essayait au clavecin sur A Powdered Wig alors que, dans Everybody Blow !, Larry Bunker intervenait au marimba.

Privilégiant guitare, saxo alto, trombone, vibraphone, et flûtes - en section ou en solo -, Henry Mancini mitonnait de séduisants mélanges sonores. Mariant connaissance des règles de la musique « sérieuse », expérience acquise au sein de grandes formations héritières de la Swing Era et assimilation des innovations dues aux arrangeurs de Stan Kenton, Mancini élargissait le vocabulaire de l’orchestration. Don Piestrup, arrangeur pour Buddy Rich : « Sa façon de mixer relève de la magie. Dureté, détente, rythme, toujours dans la proportion juste. Et son utilisation des cors d’harmonie est la meilleure que l’on puisse trouver, que ce soit dans le jazz ou dans le classique. Leur équilibre est splendide (10). »

Née sur le petit écran, la collaboration entre Henry Mancini et Blake Edwards s’étendra au cinéma. Avec Bing Crosby en vedette, « High Times » donna à Mancini l’occasion de poursuivre son flirt avec le jazz. La composition de l’orchestre n’est pas connue mais, à l’écoute de A Mild Blast, New Blood ou The Dean Speaks, aucun doute n’est permis, l’équipe Mancini est à l’œuvre.

Un film à suspense et une comédie sophistiquée les réuniront ensuite.

Dans « Experiment in Terror », la musique est réduite au minimum. Seul le thème du générique qui instaure une angoisse répondant à l’intrigue, possède une véritable présence. Très représentatif de l’écriture de son auteur, Kelly’s Tune n’est entendu que brièvement, diffusé par un autoradio.

À l’origine, il avait été convenu qu’Henry Mancini prendrait en charge la musique de « Breakfast at Tiffany’s » mais laisserait à un autre compositeur, plus qualifié que lui dans ce domaine, le soin de signer une chanson. Une décision aberrante. Si quelqu’un possédait le don d’inventer des mélodies, c’était bien lui.

Simples d’apparence mais jamais simplistes, séduisantes, facilement mémorisables, nombre de compositions de Mancini pouvaient se transformer aisément en chansons. Dans le bel album, « Dreamsville » Lola Albright (Edie Hart dans « Peter Gunn ») interprète, sous la direction de Mancini, Brief and Breezy, Slow and Easy, Sorta Blue ou Straight to Baby. Tous thèmes tirés de la série télévisée, agrémentés de « lyrics » signés Sammy Cahn ou Jay Livingstone et Ray Evans.

Après avoir entendu Audrey Hepburn, vedette de « Breakfast at Tiffany’s », interpréter How Long Has This Been Going On ? dans « Funny Face » de Stanley Donen, Henry Mancini décida de tenter sa chance. Un mois lui fut nécessaire pour trouver une mélodie qui dévoilerait la face cachée de l’exubérante Holly Golightly, tout en étant compatible avec les moyens vocaux de son interprète. Il signera alors l’une de ses plus belles compositions sur laquelle Johnny Mercer mit un texte remarquable. Dans le film, Audrey Hepburn l’interprète en s’accompagnant à la guitare, assise sur le rebord de sa fenêtre donnant sur l’escalier de secours (elle l’enregistra avec la seule assistance du guitariste Bob Bain).

Moon River avait été plébiscité par tous. Marty Rackin qui dirigeait la Paramount fit alors preuve d’une acuité de jugement digne de celle de ses pairs qui avaient voulu retirer Over the Rainbow de « The Wizard of Oz ». À l’issue d’une projection privée, ne déclara-t-il pas « Bien, mais il faudra virer cette foutue chanson. » Réputée pour sa réserve, Audrey Hepburn ne fit qu’un bond. On ne sait ce qu’elle dit exactement à Marty Racksin mais Moon River ne passa pas aux oubliettes.

Dans la partition de « Breakfast at Tiffany’s », Henry Mancini avait introduit quelques clins d’œil en direction du jazz avec Hub Caps and Tail Lights qui préfigurait quelque peu le thème fameux de « The Pink Panther » et The Big Heist mais ce sera Moon River qui recueillera les suffrages des jazzmen.

Plus de trois cents interprétations, de Barney Kessel aux Jazz Messengers en passant par Erroll Garner et Brad Mehldau, figurent maintenant dans les discographies. Seul concurrent sérieux, une autre composition de… Mancini, Days of Wine and Roses, tirée du film éponyme signé, lui aussi, par Blake Edwards.

Henry Mancini fut engagé sur « Hatari » dirigé par une légende d’Hollywood, Howard Hawks. Les deux hommes s’entendirent à merveille sur cette histoire africaine menée tambour battant par John Wayne où le jazz trouvait tout naturellement sa place. Crocodile, Go Home ! met en vedettes Shelly Manne, Jimmie Rowles, Bud Shank et Big Band Bwana se termine par un beau duel de trompettes. Le thème de Baby Elephant Walk qui accompagne les tribulations d’Elsa Martinelli aux prises avec un éléphanteau capricieux, fut interprété sur l’un de ces petits orgues à vapeur (électrifié pour l’occasion) baptisés « calliope », utilisés sur les bateaux à roues.

Mancini retrouva Blake Edwards pour « The Pink Panther » dont le thème allait connaître une immense popularité en grande partie grâce à la série de dessins animés qui suivit le film. À la différence de ses succès précédents, celui-là ne se prêtait guère à l’improvisation. Ceux qui le reprendront, comme Claude Bolling,

resteront au plus près de la version princeps.

« The Pink Panther » ouvrait la seconde partie de la carrière d’Henry Mancini, celle durant laquelle, sans disparaître complètement – on pense à « The Party »-, l’influence du jazz se fera plus diffuse. Encore que, en 1982, à l’occasion de « Victor, Victoria », son ultime collaboration avec Blake Edward, Mancini évoquera, non sans malice, le jazz des années 30 avec Le Jazz Hot chanté par Julie Andrews ou de The Big Lift.

Dans l’hommage que publia Down Beat à la suite de la disparition d’Henry Mancini le 14 janvier 1994, John Ephland rappela ses collaborations avec Shelly Manne, Shorty Rogers, Jimmie Rowles, Red Mitchell, Ray Brown. Sans évoquer la polémique assez vaine qui naquit à la suite du succès rencontré auprès du public par l’album « The music of Peter Gunn ». Les attaques étaient venues d’une partie du monde du jazz. Dans « The Jazz Review » daté de juin 1959, l’arrangeur George Russell se livra à une exécution capitale du disque, à propos duquel, dans Down Beat, Richard B. Hadlock écrivit que « le jazz doit être plus que les sons éphémères d’une musique de fond pour être supportable en disque ». » Henry Mancini n’ignorait pas ces critiques : « Je connais cette controverse. C’est étonnant parce que, à aucun moment à propos de « Peter Gunn », sur les albums ou au cours d’une interview que j’aurais donnée, n’a été faite la moindre revendication comme quoi il s’agissait de jazz. La musique était influencée par le jazz qui

participait à la dramaturgie ; bon nombre de critiques l’ont compris (11) ». Et l’admettaient. D’autres non. Écrivain, parolier, critique, un temps rédacteur en chef de Down Beat, Gene Lees aura le dernier mot : « Ses détracteurs ont été tellement occupés à déplorer ce qu’il avait fait du jazz qu’ils ont fermé les yeux sur ce qu’il avait fait pour lui. (12) »

Alain Tercinet

© 2015 Frémeaux & Associés

(1) « Did They Mention the Music ? – the Autobiography of Henry Mancini », Coopper Square Press, NYC, 2001.

(2) Henry Mancini interviewed by Valerie Sager (1982) in « The Music From Peter Gunn – complete edition », American Jazz Classics.

(3) comme (1)

(4) (5) Gene Lees, préface de « Did They Mention the Music ? – the Autobiography of Henry Mancini », Coopper Square Press, NYC, 2001.

(6) « Peter Gunn » débuta le 22 septembre 1958 sur NBC, dura trois saisons et comprendra 114 épisodes. Il fut diffusé en France sur M6, en octobre 1987, avec « Bonne chance Mr. Lucky », dans la série « Les Privés ne meurent jamais » à 16 h 40 le dimanche.

(7) comme (1)

(8) Shelly Manne and His Men enregistreront pour Contemporary deux excellents albums « Play Peter Gunn » et « Play More Music from Peter Gunn ».

(9) La musique de Mancini fut à nouveau utilisée en 1967 dans le film « Peter Gunn » tourné par Blake Edwards pour la télévision mais distribué néanmoins en salle. Peter Strauss y remplaçait Craig Stevens. En 1980, le thème de « Peter Gunn » fit partie de la bande sonore du film-culte « The Blues Brothers ». À la tête de son Harmonie Ensemble/New York, Steven Richman reprit en 2014 « The Music of Peter Gunn ». Lew Soloff et Lew Tabackin participèrent à l’enregistrement (Harmonia Mundi USA).

(10) Sammy Mitchell, « Unbuggable Mancini », Down Beat, 6 mars 1969.

(11) Fred Binkley, « Mancini’s Movie Manifesto », Down Beat, 5 mars 1970

(12) comme (4)

HENRY MANCINI

From “Glenn Miller Story” to “The Pink Panther”

1954 – 1962

“It was Cecil B. De Mille’s ‘The Crusades’ […] I had never seen a talking picture, only the silent comedies of Charlie Chase, Buster Keaton, Laurel and Hardy, Charlie Chaplin and the Keystone Cops. But what I remember most of all from that day is the music, the sound of a big orchestra. I’d never heard anything like it. I’ve never heard anything much but the concert music of the Sons of Italy band, in which I played flute and piccolo […] I thought that there was a big orchestra behind the screen […] He (my father) told me the sound of that orchestra was in the movie […] I knew what I was going to do when I grew up. I was going to write music for the movies.”(1)

In the winter of 1935, Enrico Nicola Mancini was eleven and his father had taken him to Pittsburgh to see “The Crusades.” The splendidly generous score of Rudolph G. Kopp, a Vienna-born admirer of Richard Wagner, had revealed a universe that the boy would make his own. The discovery of jazz would come three years later, thanks to an Afro-American orchestra – three trumpets, two trombones, five saxophones and a rhythm section – which expressed itself in a style, as he would remember it, close to Fletcher Henderson and Count Basie.

Henry Mancini’s years of musical apprenticeship amounted essentially to playing piano and dissecting records by Artie Shaw and Benny Goodman, due to his new-born passion for arranging. “Fortunately I’ve been able to sustain myself in music since high school. Even during high school. I used to play a lot; I used to get two or three dollars for a job, a Polish wedding, an Italian wedding... I was brought up in a place called Aliquippa, Pennsylvania. We had every ethnic minority group that was ever created in Europe. I grew up playing all these weddings; we’d get all you could eat plus a dollar or two.”(2) He went to the Juilliard School in 1942, but barely had time to discover the music of Ravel and Debussy before he was drafted into the Air Force; thanks to Glenn Miller, he was enrolled in the 28th Air Force Band and so escaped being posted as a gunner in a B-27.

Tex Beneke was a tenor player and much-appreciated singer in the band led by Glenn Miller before the war, and he decided to revive the orchestra after the bandleader’s death, with the consent of Miller’s widow. A year after the band’s debuts in January 1946, Henry Mancini was hired as its pianist and arranger, and then, at his own request, solely as its arranger: his Dancer’s Delight had no reason to envy any of the scores that Jerry Gray had cooked up for the original orchestra. Working with his peers on a daily basis allowed Mancini to evaluate their abilities and later, when working for himself, he would call on a few of them since they knew exactly what they were doing.

Thanks to his arrangement of Skip to My Lou for the Jimmy Dorsey Orchestra, Mancini was given a try-out at Universal Pictures, who were looking for a writer specializing in dance-orchestras. His two-week trial period stretched to five years, during which time he worked with the team of arrangers, orchestrators and multi-purpose composers attached to the film-studio. In the company of Herman Stein — in Mancini’s words, a marvellous musician — he worked on a host of B-movies, not to mention the Z ones. There was the “Creature from the Black Lagoon” for example, in which said creature, half-man and half-fish (and visibly smitten by actress Julie Adams), spent much of the film climbing aboard the explorers’ boat on the port side while the crew looked out to starboard; or maybe vice versa. There was even a sequel called “Revenge of the Creature” in which Mancini was also involved; Clint Eastwood was cast as a clumsy lab rat in that one.

In 1953, Henry Mancini, obviously the man for the job, was tasked with checking the original scores to be used in the film “The Glenn Miller Story”. While carrying out his mission, he noticed the absence of a melody that could accompany the more intimate moments between the two main characters. So Mancini composed Too Little Time, which, although used in the film, doesn’t appear on any of the soundtrack-albums. When “The Glenn Miller Story” reached the box-office, Too Little Time was played in the Shrine Auditorium in Los Angeles, at a concert featuring alumni of the orchestra conducted by Billy May.

After the unexpected success of Anthony Mann’s film, Universal decided to mine the seam and started production on “The Benny Goodman Story”, again with Henry Mancini as music supervisor, a role he played just as competently in other, (much) less prestigious films such as “Rock Pretty Baby”. That one reached the box-office in 1956, the same year as “The Benny Goodman Story”, and it starred Sal Mineo in a celebration of the rock ’n’ roll generation. Mancini took advantage of the film to slip in several of his own compositions, among them Free and Easy, which was quite successful as a song after lyrics were added by Bobby Troup, and What’s It Gonna Be, which was sung onscreen by Jim Daley and the Ding-A-Lings before it was picked up — for the better — by The Four Freshmen.

In 1958 Henry Mancini was given a job which, although enthralling, was strewn with pitfalls: composing the music for “Touch of Evil”. It was a noir film directed by (and starring) Orson Welles, and Welles knew what he wanted for each component of his film right from the outset. Including the music: “He truly understood film scoring. And since he was making a grimly realistic film, I think he reasoned that even the music had to be rooted in reality. And that meant it all had to come from the story itself; it would be source cues.”(3) Joseph Gershenson was head of the music department at Universal and Welles sent him a sizeable number of memos stating his demands. The plot was set in a little town on the border with Mexico, and called for various forms of Latin American music; for certain scenes, that meant the kind of rock ‘n’ roll that was in fashion then. Welles’ memos even pointed out the musical colour to be used for each scene, and also which instruments might be appropriate.

They say that Orson Welles would have approved the music that Mancini composed, even though he never heard it used in the film: Welles was barred from the editing and saw this as treason; as a result, he refused to see “Touch of Evil.” In 1998, a new version of the film based on his notes tried to restore Welles’ intentions… insofar as that was possible. Henry Mancini would always consider “Touch of Evil” as one of his best works. Accompanying the magnificent opening sequence shot, Borderline Montuma immediately creates the atmosphere. Echoing the violence of the gang of young Mexicans, Lease Breaker gives a solo to saxophonist Plas Johnson which smacks of rhythm ‘n’ blues. And was it Mancini or Welles who had the idea of associating the sound of a player piano with Tanya/Marlene Dietrich’s appearances? Nothing could have better emphasized the singularity of this character than The Blue (Angel) Pianola.

“Although others had used elements of jazz in film scores before him, it was Mancini who opened the way for the full use of this music in drama. […] He established, for a broad American public and for the executives of the communications industry, the extraordinarily expressive range of this music.”(4) Johnny Mandel, who wrote the music for “I Want to Live”, confirmed Gene Lees’ statement. He admitted that the score composed for “Touch of Evil” by Henry Mancini had made his own task that much easier where his own producers were concerned. According to Gene Lees, “Up until that time, film scoring was almost entirely derived from European symphonic composition. Mancini changed all that. More than any other person, he Americanized film scoring, and in time even European film composers followed in his path.”(5) Most of the latter came from Vienna: Erich Wolfgang Korngold, Franz Waxman, Max Steiner or Rudolph G. Kopp ruled over Hollywood in those days; originally classical composers, they had imposed a style of accompaniment by refusing all direct references to popular music.

Mancini would change all that. First, when the time came to record the music he’d written for “Touch of Evil”, he warned Joseph Gershenson that the studio-orchestra was incapable of playing his score satisfactorily; he hired Pete Candoli, Conrad Gozzo and Rollie Bundock – alongside him in the ranks of the Tex Beneke orchestra – and also Plas Johnson, Bob Bain and Shelly Manne. As other productions came along, they were joined by Ted and Dick Nash, Vince de Rosa, Ronnie Lang, Larry Bunker, Vic Feldman, and Jimmie Rowles, who replaced pianist John Towner Williams, the future composer of “Star Wars”, “Indiana Jones” and “Saving Private Ryan”. They all had more or less close ties with West Coast jazz, and they formed a nucleus which provided the very specific sound of the orchestras put together by Mancini.

During his “Universal years” (which ended when the studio was sold to MCA), Mancini had found a friend in Blake Edwards, and the screenwriter & director offered him the chance to work on a detective series for tele-vision entitled “Peter Gunn”(6) According to Mancini, “The idea of using jazz in the ‘Gunn’ score was never even discussed. It was implicit in the story. Peter Gunn hangs out in a jazz roadhouse called Mother’s where there is a five-piece jazz group. In the pilot, five or six minutes took place in Mother’s. That’s a long time, so it was obvious that jazz had to be used. It was the time of the so-called cool West Coast jazz, with Shelly Manne, the Candoli brothers and Shorty Rogers, among others. And that was the sound that came to me: the walking bass and drums. The ‘Peter Gunn’ title theme actually derives more from rock and roll than from jazz. I used guitar and piano in unison, playing what is known in music as an ostinato, which means obstinate. It was sustained throughout the piece giving it a sinister effect, with some frightened saxophone sounds and some shouting brass.”(7)

On television, fitting in nicely with Blake Edwards’ directing, – unlike a number of its contemporaries in the private-eye genre – “Peter Gunn” remains just as efficient today, with jazz predominant. Over the different episodes, Vic Feldman, Bob Bain, Rollie Bundock (and even Shorty Rogers, in the episode entitled “The Frog”), all appeared onscreen. The plot often took the Peter Gunn character into other clubs, and sometimes, in “Streetcar Jones” for example, the music itself constitutes the episode’s story. After a screening of the series’ pilot, Alan Livingstone, who was very familiar with the record-industry, suggested to RCA that they ought to publish the music from “Peter Gunn.” An album devoted to the music in a television series wasn’t something in the RCA vocabulary, and so the company turned a deaf ear. Ray Anthony, however, had just had a hit with the theme from “Dragnet”, another TV series. Anthony knew Blake Edwards well enough to suggest that he should record “Peter Gunn” with an arrangement by Mancini; it was so successful that it changed RCA’s mind. Stereo recordings had by now become almost a commonplace in the record-market and so everything had to be re-recorded. And Henry Mancini’s name was unknown to the general public. Upstairs at RCA, it was decided that someone with more wind in his sails ought to be involved, namely Shorty Rogers; Shorty was honest enough to turn them down. It was Mancini’s music; he’d composed it and knew it better than anyone, so he ought to conduct the whole affair. Mancini was offered a contract to make a single album, and a clause stipulated that the number of copies of it to be manufactured would be RCA’s decision. They pressed 800. All of them were sold inside a week…

The albums “Music from Peter Gunn” and “More Music from Peter Gunn” were new studio versions of themes played either in fragments by the quintet at “Mother’s” or else accompanying certain scenes. Dreamsville was reminiscent of Gil Evans, and Soft Sounds was a salute to the Modern Jazz Quartet; snapping fingers on The Floater recreated a club atmosphere while My Man Shelly was a tribute to Shelly Manne, a major figure in Californian jazz who was close to Mancini for years.(8) The orchestral parts played by the big band showed the influence of Stan Kenton, whose imprint, incidentally, is present in many soundtracks. With eleven mentions at the 1959 Grammy Awards, “Music from Peter Gunn” received two, with awards as “Album of the Year” and for “Best Arrangement.” At the Emmy Awards, its theme was “Best Musical Contribution to a Television Program.” Over the years, the theme would be recorded in over fifty versions.(9)

Another television series saw Mancini associated with Blake Edwards: “Mr Lucky.” That one was set in exotic surroundings whose atmosphere was rendered by Siesta, played by Laurindo Almeida. There wasn’t much room for jazz in the film; in fact, it amounted to That’s It And That’s All, period. On the other hand, the film’s main theme served as a springboard for an impressive number of jazzmen in the same way as “Peter Gunn.”

Around the same time as “Rock Pretty Baby,” Mancini made the album “Driftwood and Dreams” which was reissued under the title “The Versatile Henry Mancini.” It was a stylistic exercise and it showed Mancini’s taste for unusual sound-mixtures. Two years later, “The Mancini Touch” would use twenty strings, four horns, four trombones, five rhythm instruments (including a vibraphone), plus Ted Nash on alto saxophone and Ronnie Lang on alto flute (switching to baritone for Robbin’s Nest). The instrumentation was original enough to enhance even further such original compositions as Politely and A Cool Shade of Blue. It has to be said that Billboard, the bible of the record-industry, referred to the ensemble which recorded “Music from Peter Gunn” as, “The most promising band of the year.” So it made life that much easier for Henry Mancini when setting up a session devoted to his arrangements for pieces that were not directly related to television or films. It would be the first of a long series, and “The Blues and the Beat” was one of the records they produced. In his sleeve notes, Mancini stated that, “If jazz could be taken into a laboratory and put through a distilling process, two things would remain after everything else had evaporated: the blues and the beat.” One side of the album was devoted to each of them, with an original theme introducing five classics in the jazz repertoire. The Blues brought in Blue Flame and After Hours, while The Beat announced Tippin’ In and How Could You Do A Thing Like That To Me?

To remain coherent with the title chosen for his following LP (“Combo!”), Mancini brought ten of his favourite jazzmen down to the studio along with Art Pepper… who played clarinet on Moanin’ and Swing Lightly. John T. Williams gives the harpsichord a try on A Powdered Wig while for Everybody Blow! Larry Bunker switches to a marimba. Favouring the guitar, alto saxophone, trombone, vibraphone and flutes — as a section or playing solo — Henry Mancini cooked up some seductive blends of sound. Marrying his knowledge of the rules of “serious” music, his experience acquired in big bands that were heirs to the Swing Era, and also his assimilation of the innovations owed to Stan Kenton’s arrangers, Mancini broadened the vocabulary of orchestration. Don Piestrup, an arranger for Buddy Rich, declared, “He mixes like a magician. Tightness, relaxation, rhythm... always in the right proportion. And his French horns are the greatest to be found anywhere, either jazz or classical. They’re beautifully balanced.”(10)

Born in television, the collaboration between Henry Mancini and Blake Edwards moved into films. With Bing Crosby as its star, “High Times” gave Mancini the opportunity to continue flirting with jazz. We don’t have details of the members of the orchestra, but listening to A Mild Blast, New Blood or The Dean Speaks leaves no doubt that this is Mancini’s crew at work. And they carried on together with a thriller and a sophisticated comedy. In “Experiment in Terror”, the music was reduced to a minimum; only the music behind the credits — it installs the dread inherent in the title and plot — has a genuine presence. Kelly’s Tune, highly representative of Mancini’s writing, is heard only briefly, played over a car radio. As for “Breakfast at Tiffany’s,” it was initially understood that Mancini would take charge of the music, and that another composer with better song-writing qualifications would be entrusted with the song for the film. How absurd… someone with a greater gift for melody than Henry Mancini? A number of his compositions may have seemed simple, but they were never simplistic, always seductive and always easily memorable; they could also be turned into songs without difficulty. In the handsome album called “Dreamsville”, Lola Albright (she was ‘Edie Hart’ in “Peter Gunn”), sings Brief and Breezy, Slow and Easy, Sorta Blue and Straight to Baby with Mancini conducting. All of them were taken from the television series, with lyrics written by Sammy Cahn or Jay Livingstone and Ray Evans.

After hearing the “Breakfast at Tiffany’s” star Audrey Hepburn singing “How Long Has This Been Going On?” — in Stanley Donen’s “Funny Face” — Mancini decided to try his luck. It took him a month to come up with a melody that could unveil the hidden face of the exuberant Holly Golightly and also match the star’s vocal resources. The result was one of Mancini’s most beautiful compositions, to which Johnny Mercer added some remarkable lyrics. In the film, Audrey Hepburn sings it accompanying herself on the guitar, while sitting on the window-ledge next to the fire-escape (she recorded it with the aid of guitarist Bob Bain alone).

Moon River had everybody’s vote. Marty Rackin was head of production at Paramount and he demonstrated how sound and reliable his judgment was, in the same way as his peers when they wanted to remove “Over the Rainbow” from “The Wizard of Oz”... After a private screening Marty declared, “Well, the fucking song has to go.” Audrey Hepburn was known for her reserve, but obviously her blood quickened; we don’t know exactly what she said to Rackin but Moon River stayed.

In his score for “Breakfast at Tiffany’s”, Mancini had introduced a few veiled allusions to jazz with The Big Heist and Hub Caps and Tail Lights, a composition that somehow announced the famous “Pink Panther” theme. However, Moon River was the candidate for jazzmen: more than three hundred versions, from Barney Kessel to The Jazz Messengers, and including Erroll Garner and Brad Mehldau, can be found in discographies today. In fact its only serious competition comes from… another composition by Mancini, Days of Wine and Roses, taken from the film of the same name (directed by Blake Edwards also.)

When Henry Mancini was hired by the producers of “Hatari” — filmed by Hollywood legend Howard Hawks — the composer and the director got on famously when working on this tale set in Africa with John Wayne in charge of the cast. Jazz naturally plays a role here, with Crocodile, Go Home! featuring Shelly Manne, Jimmie Rowles and Bud Shank, and Big Band Bwana ending on beautiful duelling trumpets. The Baby Elephant Walk theme accompanying Elsa Martinelli’s tribulations with a capricious baby elephant was played on one of those little steam organs used on paddle boats; called a calliope, this one was electrically amplified for the occasion.

Mancini met up with Blake Edwards again for “The Pink Panther”, whose main theme became immensely popular later, mostly thanks to a cartoon series produced after the film. Unlike Mancini’s previous hits, this one hardly lent itself to improvisation, and others who recorded it, like Claude Bolling, stayed as close as possible to the seminal version. “The Pink Panther” began a new chapter in Mancini’s career, a second life where jazz, while not disappearing completely — take “The Party” for example — had a scarcer presence. Even so, for his final collaboration with Blake Edwards (“Victor, Victoria” in 1982), Mancini impishly recalled the jazz of the Thirties with Julie Andrews singing “Le Jazz Hot”, or else “The Big Lift.”

In the tribute to Mancini which appeared in Down Beat after his passing on January 14th 1994, John Ephland reminded readers of the composer’s ties with Shelly Manne, Shorty Rogers, Jimmie Rowles, Red Mitchell or Ray Brown, but didn’t devote a word to the rather pointless controversy which arose after the reception that the public gave to “The Music of Peter Gunn”. The attacks on Mancini came partly from the jazz world: in the June 1959 issue of “The Jazz Review”, arranger George Russell took a figurative hatchet to the album, while Richard B. Hadlock wrote in Down Beat that, “Jazz must be more than transient background sounds to endure on record.”

Henry Mancini was quite aware of that criticism, saying: “I know the controversy. It was very strange because at no time during the ‘Peter Gunn’ show was any claim made, on the albums or by me in any interview, that it was jazz. It was jazz-oriented, it was dramatic, and jazz was a part of it; in that way it was picked up by various critics.”(11) They admitted as much. Others did not. The last word would be had by writer, lyricist, critic and onetime-editor of Down Beat, Gene Lees, who wrote, “His detractors were so busy deploring what Mancini had done with jazz that they overlooked what he was doing for it.”(12)

Adapted by Martin Davies

from the French text of Alain Tercinet

© 2015 Frémeaux & Associés

(1) “Did They Mention the Music? The Autobiography of Henry Mancini,” Cooper Square Press, NYC, 2001.

(2) Henry Mancini interviewed by Valerie Sager (1982) in “The Music From Peter Gunn – Complete Edition”, American Jazz Classics.

(3) See (1).

(4) (5) Gene Lees, in his preface to “Did They Mention the Music?” Cf. (1)

(6) “Peter Gunn” was first shown on NBC, beginning on September 22, 1958. There were three seasons and 114 episodes.

(7) See (1).

(8) Shelly Manne and His Men recorded two excellent albums for Contemporary, “Play Peter Gunn” and “Play More Music from Peter Gunn”.

(9) Mancini’s music was used again in 1967 in the film “Peter Gunn” which Blake Edwards made for television (it was also shown in cinemas), and Peter Strauss replaced Craig Stevens in the cast. In 1980 the “Peter Gunn” theme was used in the soundtrack for the cult movie “The Blues Brothers”. In 2014, Steven Richman and his Harmonie Ensemble/New York picked up “The Music of Peter Gunn,” with Lew Soloff and Lew Tabackin taking part in the recording (Harmonia Mundi USA).

(10) Sammy Mitchell in “Unbuggable Mancini”, Down Beat, March 6, 1969.

(11) Fred Binkley in “Mancini’s Movie Manifesto”, Down Beat, March 5, 1970.

(12) See (4).

DISCOGRAPHIE HENRY MANCINI

CD 1 - “THE SOUNDTRACKS ”

1. FREE AND EASY Decca DL 429 1’52

Rock, Pretty Baby - Henry Mancini (cond), unidentified orchestra - 1956

2. BORDERLINE MONTUNA Challenge 615 2’01

3. LEASE BREAKER Challenge 615 2’44

Touch of Evil (La soif du mal) : Pete Candoli, Conrad Gozzo (tp) ; Milt Bernhardt (tb) ; Plas Johnson (ts) ; Dave Pell (bs) ; Ray Sherman (p) ; Red Norvo (vib) ; Bob Bain (g) ; Rollie Bundock (b) ; Shelly Manne (dm) ; Jack Costanzo (bgo) + Universal-International Orchestra, Joseph Gershenson (cond) - Hollywood, January 17, 1958

4. BLUE (ANGEL) PIANOLA Challenge 615 3’10

Ray Sherman (pianola) - Hollywood, January 1958

5. PETER GUNN RCA Victor LPM-1956 2’06

Peter Gunn (TV series) : Pete Candoli, Ray Linn, Frank Beach, Uan Rasey (tp) ; Dick Nash, Jimmy Priddy, Milt Bernhart, Karl de Karske (tb) ; Vince de Rosa, Richard Perissi, John Cave, John Graas (frh) ; Ted Nash (as) ; Ronnie Lang (bs) ; Al Hendrickson, Bob Bain (g) ; Rollie Bundock (b) ; Jack Sperling (dm) ; Henry Mancini (cond) – Hollywood, August 26, 1958

6. DREAMSVILLE RCA Victor LPM-1956 3’55

Conrad Gozzo, Pete Candoli, Frank Beach, Uan Rasey (tp) ; Dick Nash, Jimmy Priddy, Milt Bernhart, Karl de Karske (tb) ; Vince de Rosa, Richard Perissi, John Cave, John Graas (frh) ; Plas Johnson, Ted Nash (s) ; John T. Williams (p) ; Larry Bunker (vib) ; Alton Hendrickson, Barney Kessel (g) ; Rollie Bundock (b) ; Jack Sperling (dm) ; Henry Mancini (cond) – Hollywood, August 31, 1958

7. THE FLOATER RCA Victor LPM-1956 3’17

8. A PROFOND GASS RCA Victor LPM-1956 3’20

Dick Nash (tb) ; Ronnie Lang (s) ; John T. Williams (p) ; Vic Feldman (vib) ; Bob Bain (g) ; Rollie Bundock (b) ; Jack Sperling (dm) ; Henry Mancini (cond) – Hollywood, September 4, 1958

9. NOT FROM DIXIE RCA Victor LPM-1956 4’10

Pete Candoli, Ray Linn, Frank Beach, Uan Rasey (tp) ; Dick Nash, Jimmy Priddy, Milt Bernhart, Karl de Karske (tb) ; Vince de Rosa, Richard Perissi, John Cave, John Graas (frh) ; Ronnie Lang, Ted Nash (s) ; Al Hendrickson, Bob Bain (g) ; Rollie Bundock (b) ; Jack Sperling (dm) ; Henry Mancini (cond) – Hollywood, August 26, 1958

10. MY MAN SHELLY RCA Victor LPM-2040 2’39

Pete Candoli (tp) ; Dick Nash (tb) ; Ted Nash (as, picc, fl), Ronnie Lang (bs, alto fl) ; John T. Williams (p) ; Vic Feldman (vib) ; Bob Bain (g) ; Joe Mondragon (b) ; Shelly Manne (dm) ; Henry Mancini (cond) – Hollywood, February 17, 1958

11. THE LITTLE MAN THEME RCA Victor LPM-2040 3’16

12. SPOOK ! RCA Victor LPM-2040 2’59

Conrad Gozzo, Pete Candoli, Frank Beach, Graham Young (tp) ; Dick Nash, Jimmy Priddy, Hoyt Bohannon, Karl de Karske (tb) ; Ted Nash (as, picc, fl) ; Ronnie Lang (bs, alto fl) ; Paul Horn, Gene Cipriano (woodwinds) ; Plas Johnson (ts on Spook !) ; John T. Williams (p) ; Vic Feldman (vib) ; Bob Bain (g) ; Rollie Bundock (b) ; Shelly Manne (dm) ; Henry Mancini (cond) – Hollywood, March 5, 1959

13. Mr. LUCKY RCA Victor LPM-2198 2’14

Mr. Lucky (TV series) : Don Fagerquist (tp) ; Dick Nash, Jimmy Priddy, John Halliburton, Karl de Karske (tb) ; Vince de Rosa, Dick Perissi, John Cave, John Graas (frh) ; Ronnie Lang, Harry Klee, Gene Cipriano, Jules Jacob, Lloyd Hildebrandt (s) ; John T. Williams (p) ; Edwin L. Cole (org) ; Bob Bain (g) ; Rollie Bundock (b) ; Shelly Manne (dm) ; Frank Flynn (perc) + strings ; Henry Mancini (cond – Hollywood, December 4, 1959

14. THAT’S IT AND THAT’S ALL RCA Victor LPM-2198 2’54

Same but James Decker (frh), Howard Terry (s), Al Hendrickson (g) replaces John Cave, Lloyd Hildebrandt, Bob Bain ; Milt Holland (dm) added – Hollywood, December 17, 1959

15. SIESTA RCA Victor LPM-2360 2’51

Dick Nash (tb) ; Vince de Rosa (frh) ; Ronnie Lang (s) ; Jimmie Rowles (p) ; Robert Hammack (org) ; Laurindo Almeida, Bob Bain (g) ; Rollie Bundock (b) ; Shelly Manne, Larry Bunker, Milt Holland, Frank Flynn (perc) ; Henry Mancini (cond) – Hollywood, January 12, 1961

16. A MILD BLAST RCA Victor LPM-2314 3’09

17. NEW BLOOD RCA Victor LPM-2314 2’47

18. HE DEAN SPEAKS RCA Victor LPM-2314 2’37

High Time (Une seconde jeunesse) : Shelly Manne (dm) with unidentified orchestra prob. Jimmie Rowles (p) ; Henry Mancini (cond) - 1960

19. MOON RIVER Film Soundtrack 2’10

Breakfast at Tiffany’s (Diamants sur canapé) : Audrey Hepburn (voc) ; George Peppard (word) ; Bob Bain (g) + unidentified orchestra ; Henry Mancini (cond) – Hollywood, December 8, 1960

20. HUB CAPS AND TAIL LIGHTS RCA Victor LPM-2362 2’32

21. THE BIG HEIST RCA Victor LPM-2362 3’12

Dick Nash, Jimmy Priddy, Karl de Karske (tb) ; Ted Nash, Gene Cipriano, Wilbur Schwartz (s) ; Jimmie Rowles (p) ; Larry Bunker (vib) ; Bob Bain (g) ; Red Mitchell (b) ; Shelly Manne (dm) + strings ; Henry Mancini (lead) – Hollywood, April 27, 1961

22. EXPERIMENT IN TERROR RCA Victor LPM-2442 2’18

23. KELLY’S TUNE RCA Victor LPM-2442 3’18

Experiment in Terror (Allo, Brigade spéciale) : Conrad Gozzo, Pete Candoli, Frank Beach, Ray Triscari (tp) ; Dick Nash (tb) ; Ronnie Lang, Gene Cipriano, Ted Nash (woodwinds) ; Jimmie Rowles (p) ; Vic Feldman (vib) ; Bob Bain (g, autoharp) ; Red Mitchell (b) ; Shelly Manne (dm) with unidentified orchestra ; Henry Mancini (cond) - 1962

24. BABY ELEPHANT WALK RCA Victor LPM-2559 2’43

25. BIG BAND BWANA RCA Victor LPM-2559 3’02

26. CROCODILE, GO HOME ! RCA Victor LPM-2559 2’55

Hatari ! : Don Fagerquist, Pete Candoli, Conrad Gozzo, Ray Triscari (tp) ; Dick Nash, Jimmy Priddy, Dick Noel, Karl de Karske (tb) ; Sam Rice (tuba) ; Benny Gill (vln) ; Bud Shank, Harry Klee (fl, s), Ronnie Lang, Gene Cipriano, Wilbur Schwartz, Justin Gordon, Mahlon Clark (s) ; Jimmie Rowles, Ray Sherman (p) ; Bob Bain (g) ; Rollie Bundock (b) ; Shelly Manne, Frank Flynn, Milt Holland (dm) ; Henry Mancini (cond) – Hollywood, December 5, 1961

All tunes composed by Henry Mancini. Moon River (J. Mercer – H. Mancini)

« Jusqu’à cette période, la musique de film découlait presqu’entièrement de la musique symphonique européenne. Mancini a changé tout ça. » Gene Lees

“Up until that time, film scoring was almost entirely derived from European symphonic composition. Mancini changed all that.” Gene Lees

CD 1 : “The Soundtracks”

Rock, Pretty Baby

1. Free and Easy 1’52

Touch of Evil

2. Borderline Montuma 2’01

3. Lease Breaker 2’44

4. Blue (Angel) Pianola 3’10

Peter Gunn

5. Peter Gunn 2’06

6. Dreamsville 3’55

7. The Floater 3’17

8. A Profond Gass 3’20

9. Not From Dixie 4’10

10. My Man Shelly 2’39

11. The Little Man Theme 3’16

12. Spook ! 2’59

Mr Lucky

13. Mr. Lucky 2’14

14. That’s It and That’s All 2’54

15. Siesta 2’51

High Time

16. A Mild Blast 3’09

17. New Blood 2’47

18. The Dean Speaks 2’37

Breakfast at Tiffany’s

19. Moon River 1’52

20. Hub Caps and Tail Lights 2’32

21. The Big Heist 3’12

Experiment in Terror

22. Experiment in Terror 2’18

23. Kelly’s Tune 3’18

Hatari !

24. Baby Elephant Walk 2’43

25. Big Band Bwana 3’02

26. Crocodile, Go Home ! 2’55

CD 2 : “The Music Of Henry Mancini”

Tex Beneke and His Orchestra

1. Dancer’s Delight 3’07

The Original Reunion of The Glenn Miller Band

2. Too Little Time 2’53

The Four Freshmen

3. What’s It Gonna Be 1’44

Ray Anthony and His Orchestra

4. The Peter Gunn Theme 1’50

Lola Albright

5. Brief and Breezy 3’16

6. Slow and Easy 2’32

7. Straight to Baby 2’50

8. Sorta Blue 2’57

Henry Mancini and His Orchestra

9. Politely 3’17

10. Let’s Walk 3’05

11. A Cool Shade of Blues 3’47

12. Robbin’s Nest 3’39

13. The Blues 2’40

14. Blue Flame 2’45

15. After Hours 3’07

16. The Beat 3’08

17. Tippin’ in 3’46

18. How Could You Do A Thing Like That to Me ? 3’32

19. Moanin’ 2’51

20. Swing Lightly 4’17

21. A Powedered Wig 2’38

22. Far East Blues 3’26

23. Everybody Blow ! 3’22

24. Days of Wine and Roses 2’07

Claude Bolling Big Band

25. The Pink Panther Theme 3’04