- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

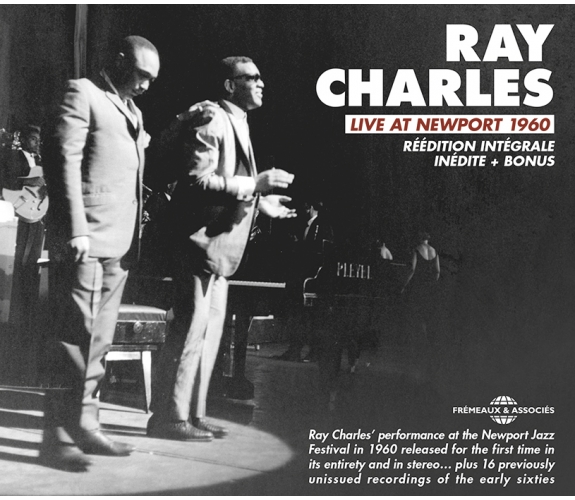

RÉÉDITION INTÉGRALE INÉDITE + BONUS

RAY CHARLES

Ref.: FA5643

Artistic Direction : JOEL DUFOUR

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Total duration of the pack : 2 hours 3 minutes

Nbre. CD : 2

RÉÉDITION INTÉGRALE INÉDITE + BONUS

RÉÉDITION INTÉGRALE INÉDITE + BONUS

“This 2 CD set presents, for the fi rst time in its entirety and in stereo, Ray Charles’ performance at the Newport Jazz Festival in 1960, plus a selection of previously unreleased recordings from the years 1960 to 1962 focusing on his often underrated talents as an instrumentalist playing piano, organ and alto saxophone, as well as on his supreme skill at singing and playing the blues.” Joël DUFOUR

Prepared for release by Joël Dufour, probably the greatest expert on the work of Ray Charles, this set highlights the “jazz” sides of the Genius when he was at his artistic peak. After making available Ray Charles’ legendary Paris concerts of 1961 and ’62 — released as “Live in Paris”, FA5471, with the accent on Ray’s soul and R&B titles — Frémeaux & Associés are proud to present this set complementing the Art of Brother Ray. Patrick FRÉMEAUX

IRMA THOMAS • DAVE BARTHOLOMEW • LARRY WILLIAMS •...

BROTHER RAY : THE GENIUS

20-21 OF OCTOBER 1961 / 17-18-20-21 OF MAY 1962

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Introduction By Willis ConoverBoris Alexandrov, Chœurs de l'armée rougeWillis Conover00:00:091960

-

2The StoryRay CharlesJames Moody00:05:041960

-

3Lil' Darlin'Ray CharlesNeal Hefti00:06:281960

-

4Blues WaltzRay CharlesMax Roach00:06:111960

-

5Let The Good Times RollRay CharlesSam Theard00:02:451960

-

6Don't Let The Sun Catch You Cryin'Ray CharlesJ. Greene00:04:101960

-

7Sticks And StonesRay CharlesTitus Turner00:03:141960

-

8I Believe To My SoulRay CharlesRay Charles00:03:451960

-

9My Baby (I Love Her Yes I Do)Ray CharlesRay Charles00:03:531960

-

10Drown In My Own TearsRay CharlesHenry Glover00:07:061960

-

11What'd I SayRay CharlesRay Charles00:06:011960

-

12Georgia On My MindRay CharlesS. Gorrell00:04:081960

-

13Hallelujah I Love Her SoRay CharlesRay Charles00:02:511960

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Blue StoneRay CharlesHank Crawford00:07:541962

-

2Moanin'Ray CharlesBobby Timmons00:03:101962

-

3PopoRay CharlesShorty Rogers00:04:081961

-

4Lil' Darlin 2Ray CharlesNeal Hefti00:07:531961

-

5One Mint JulepRay CharlesRudolph Toombs00:02:551961

-

6From The HeartRay CharlesRay Charles00:03:301961

-

7Doodlin'Ray CharlesHorace Silver00:07:521961

-

8Come Rain Or Come ShineRay CharlesJohnny Mercer00:07:131961

-

9I Ve Got News For YouRay CharlesAlfred Roy00:04:331961

-

10I WonderRay CharlesCecile Gant00:03:471961

-

11I M Gonna Move To The Outskirts Of TownRay CharlesR. Jacobs00:04:421961

-

12What'd I Say 2Ray CharlesRay Charles00:03:401961

-

13Georgia On My Mind 2Ray CharlesHoagy Carmichael00:02:481961

-

14Dialog Between Both “Ray Charles”Ray CharlesRay Charles00:00:171961

-

15What'd I Say 3Ray CharlesRay Charles00:03:061961

Ray Charles Live FA5643

Ray

Charles

Live At Newport 1960

Réédition intégrale inédite + bonus

Ray Charles’ performance at the Newport Jazz Festival in 1960 released for the first time in its entirety and in stereo… plus 16 previously unissued recordings of the early sixties

« Ce double-CD présente, pour la première fois dans son intégralité et en stéréo, la prestation de Ray Charles au festival de jazz de Newport en 1960, et une sélection d’enregistrements inédits des années 1960 à 1962 mettant notamment en lumière ses talents souvent méconnus d’instrumentiste, au piano, à l’orgue et au saxophone-alto, ainsi que son art suprême à interpréter des blues. » Joël DUFOUR

Réalisé par Joël Dufour, sans doute le plus grand spécialiste de Ray Charles, ce coffret met en exergue les facettes « jazz » du Genius alors au sommet de son art. Après avoir mis à disposition du public ses légendaires concerts parisiens de 1961 et 1962 (Ray Charles « Live in Paris » FA5471, dans un registre soul, R&B) Frémeaux & Associés est fier de vous proposer un pan complémentaire de l’art de Brother Ray.

Patrick FRÉMEAUX

“This 2 CD set presents, for the first time in its entirety and in stereo, Ray Charles’ performance at the Newport Jazz Festival in 1960, plus a selection of previously unreleased recordings from the years 1960 to 1962 focusing on his often underrated talents as an instrumentalist playing piano, organ and alto saxophone, as well as on his supreme skill at singing and playing the blues.” Joël DUFOUR

Prepared for release by Joël Dufour, probably the greatest expert on the work of Ray Charles, this set highlights the “jazz” sides of the Genius when he was at his artistic peak. After making available Ray Charles’ legendary Paris concerts of 1961 and ’62 — released as “Live in Paris”, FA5471, with the accent on Ray’s soul and R&B titles — Frémeaux & Associés are proud to present this set complementing the Art of Brother Ray.

Patrick FRÉMEAUX

CD-1 (57’14):

1. Introduction by Willis Conover

(Newport Jazz Festival, July 2, 1960) 0’09

2. The Story (James Moody) 5’04

3. Lil’ Darlin’ (Neal Hefti) 6’27

4. Blues Waltz (Max Roach) 6’11

5. Let the Good Times Roll (Sam Theard, Fleecie Moore) 2’44

6. Don’t Let the Sun Catch You Cryin’ (Joe Greene) 4’09

7. Sticks and Stones (Titus Turner) 3’13

8. I Believe to My Soul (Ray Charles) 3’45

9. My Baby (I Love Her, Yes I Do) (Ray Charles) 3’52

10. Drown in My Own Tears (Henry Glover) 7’06

11. What’d I Say (Ray Charles) 6’01

12. Georgia on My Mind (Hoagy Carmichael, Stuart Gorrell)

(with spoken intro by Hugh Hefner) 4’08

13. Hallelujah I Love Her So (Ray Charles) 2’51

CD-2 (67’21):

1. Blue Stone (Hank Crawford) 7’54

2. Moanin’ (Bobby Timmons) 3’09

3. Popo (Shorty Rogers) 4’08

4. Lil’ Darlin’ (Neal Hefti) 7’53

5. One Mint Julep (Rudolph Toombs) 2’55

6. From the Heart (Ray Charles) 3’29

7. Doodlin’ (Horace Silver) 7’52

8. Come Rain or Come Shine

(Johnny Mercer, Harold Arlen) 7’13

9. I’ve Got News for You (Roy Alfred) 4’33

10. I Wonder (Cecil Gant, Raymond Leveen) 3’47

11. I’m Gonna Move to the Outskirts of Town

(Roy Jacobs, Andy Razaf, William Weldon) 4’42

12. What’d I Say (Ray Charles) 3’40

13. Georgia on My Mind

(Hoagy Carmichael, Stuart Gorrell) 2’48

14. Dialog between both “Ray Charles”

(Perry Como show, February 22, 1961) 0’17

15. What’d I Say (Ray Charles) 3’06

Ray Charles Live At Newport 1960 (plus bonus)

Composition du double-CD et renseignements discographiques :

CD-1 (57’14) :

1 - Introduction by Willis Conover

(Newport Jazz Festival, July 2, 1960) 0’09

2 - The Story (James Moody) [1]

[solo: PG, LC, JH, HC, DN, RC] 5’04

3 - Lil’ Darlin’ (Neal Hefti) [1]

[solo: RC, JH, PG, DN, HC, RC] 6’27

4 - Blues Waltz (Max Roach) [1]

[solo: PG, HC, JH, DN, LC, RC] 6’11

5 - Let the Good Times Roll

(Sam Theard, Fleecie Moore) [1]

[solo: DN] 2’44

6 - Don’t Let the Sun Catch You Cryin’

(Joe Greene) [1] [solo: RC, JH] 4’09

7 - Sticks and Stones (Titus Turner) [1]

[solo: RC] 3’13

8 - I Believe to My Soul (Ray Charles) [1] 3’45

9 - My Baby (I Love Her, Yes I Do) (Ray Charles) [1] [solo: MH] 3’52

10 - Drown in My Own Tears (Henry Glover) [1] 7’06

11 - What’d I Say (Ray Charles) [1] 6’01

12 - Georgia on My Mind (Hoagy Carmichael,

Stuart Gorrell) [2] [solo: DN]

(with spoken intro by Hugh Hefner) 4’08

13 - Hallelujah I Love Her So (Ray Charles) [2]

[solo: DN] 2’51

CD-2 (67’21) :

1 - Blue Stone (Hank Crawford) [3]

[solo: RC] 7’54

2 - Moanin’ (Bobby Timmons) [4]

[solo: RC, PG] 3’09

3 - Popo (Shorty Rogers) [5]

[solo: HC, DN, PG, LC, RC] 4’08

4 - Lil’ Darlin’ (Neal Hefti) [5]

[solo: RC, JH, PG, DN, HC, RC] 7’53

5 - One Mint Julep (Rudolph Toombs) [6]

[solo: RC] 2’55

6 - From the Heart (Ray Charles) [6]

[solo: RC, PG] 3’29

7 - Doodlin’ (Horace Silver) [7]

[solo: RC, PG, DN, LC] 7’52

8 - Come Rain or Come Shine (Johnny Mercer, Harold Arlen) [6] [solo: DW] 7’13

9 - I’ve Got News for You (Roy Alfred) [8]

[solo: RC] 4’33

10 - I Wonder (Cecil Gant, Raymond Leveen) [8] 3’47

11 - I’m Gonna Move to the Outskirts of Town

(Roy Jacobs, Andy Razaf, William Weldon) [7] [solo: PG, RC] 4’42

12 - What’d I Say (Ray Charles) [9] 3’40

13 - Georgia on My Mind (Hoagy Carmichael,

Stuart Gorrell) [10] [solo: DN] 2’48

14 - Dialog between both “Ray Charles”

(Perry Como show, February 22, 1961) 0’17

15 - What’d I Say (Ray Charles) [11] 3’06

[1] – Newport Jazz Festival, Rhode Island, July 2, 1960 (Voice of America radio recording)

Ray Charles (vocals, piano); Phillip Guilbeau (trumpet); John Hunt (flugelhorn); Hank Crawford (Bennie Ross “Hank” Crawford, Jr.) (alto saxophone, band leader); David “Fathead” Newman (tenor saxophone); Leroy “Hog” Cooper (baritone saxophone); Edgar Willis (bass); Milton Turner (drums); the Raelets: Gwendolyn Berry, “Margie Hendrix” (Marjorie Hendricks), Mae Moseley, Bettye Smith (background vocals).

[2] – “Playboy’s Penthouse” TV show, December 4, 1960

Ray Charles (vocals, piano); David Newman (flute, tenor saxophone); unidentified bassist and drummer.

[3] – Olympia Theater, Paris, May 21, 1962 (Europe-1 radio recording)

Ray Charles (alto saxophone); Marcus Belgrave, Wallace Davenport, Phil Guilbeau (trumpet); John Hunt (flugelhorn); Henderson Chambers, James Lee Harbert, Frederic “Keg” Johnson, James Leon Comegys (trombone); Everard “Rudy” Powell (alto saxophone); David Newman, Donald Wilkerson (tenor saxophone); Leroy Cooper (baritone saxophone); Elbert “Sonny” Forriest (guitar); Hank Crawford (piano, band leader); Edgar Willis (bass); Edward “Bruno” Carr (drums).

[4] – Olympia Theater, Paris, May 20, 1962 (Europe-1 radio recording)

Same as [3] above, except that Ray Charles plays piano and Hank Crawford plays alto saxophone.

[5] – Antibes Juan-les-Pins Jazz Festival, July 21, 1961 (RTF radio recording)

Ray Charles (piano); Phil Guilbeau (trumpet); John Hunt (flugelhorn); Hank Crawford (alto saxophone, band leader); David Newman (tenor saxophone); Leroy Cooper (baritone saxophone); Edgar Willis (bass); Bruno Carr (drums).

[6] – Palais des Sports, Paris, October 21, 1961 (RTF radio recording)

Ray Charles (organ – plus vocals on Come Rain or Come Shine) with same personnel as on [4].

[7] – Palais des Sports, Paris, October 22, 1961 (afternoon concert) (RTF radio recording)

Ray Charles (organ, – plus vocals on I’m Gonna Move to the Outskirts of Town) with same personnel as on [4].

[8] – Kongresshaus-Bühne, Zürich, October 18, 1961 (Radio Basel recording)

Ray Charles (vocals, piano) with same personnel as on [4]. On I Wonder, add the Raelets: Gwen Berry, Margie Hendrix, Priscilla “Pat” Moseley Lyles, Ethel “Darlene” McCrea.

[9] – soundtrack of the 20th Century Fox film “Swingin’ Along”, 1961

Ray Charles (vocals, organ); Phil Guilbeau (trumpet); John Hunt (flugelhorn); David Newman (tenor saxophone); Leroy Cooper (baritone saxophone); Edgar Willis (bass); Bruno Carr (drums); The Raelets: Gwen Berry, Margie Hendrix, Pat Moseley Lyles, Darlene McCrea (Hank Crawford may also have been present as alto saxophonist and band leader).

[10] – “Perry Como’s Kraft Music Hall” TV show, February 22, 1961

Ray Charles (vocals, piano) with David Newman (flute); Edgar Willis (bass); Milton Turner (drums); The Ray Charles Singers (background vocals); strings.

[11] – as [10] but omit strings and add: Phil Guilbeau (trumpet); John Hunt (flugelhorn); Hank Crawford (alto saxophone, band leader); David Newman (tenor saxophone); Leroy Cooper (baritone saxophone); The Raelets: Gwen Berry, Margie Hendrix, Mae Moseley, Darlene McCrea.

Blue Stone was arranged by Hank Crawford.

I’ve Got News for You was arranged by Ralph Burns.

Come Rain or Come Shine, Doodlin’, From the Heart,

I’m Gonna Move to the Outskirts of Town,

Let the Good Times Roll,

Moanin’ and One Mint Julep were arranged by Quincy Jones.

The other arrangements are by Ray Charles.

Ray Charles Live at Newport 1960 (plus bonus)

Par Joël Dufour

Le début des années 1960 avait marqué pour Ray Charles, non sans remous, la consécration de cette « crossover » (la conquête du public blanc) à laquelle il aspirait, tout comme tant d’autres artistes popu-laires noirs pour qui drainer la plus vaste audience possible constituait un enjeu de survie.

Si Ray Charles jouissait déjà de l’adhésion d’une frange de la jeunesse blanche dingue de Rock ’n’ Roll, qui dansait déjà (plus ou moins clandestinement) depuis plusieurs années au rythme des succès qu’il multipliait dans le domaine du Rhythm ’n’ Blues (I got a woman, Hallelujah I love her so, What’d I say…), il visait maintenant le grand public d’âge plus mûr dont l’idole majeure était alors Frank Sinatra. Aussi, dès octobre 1959, s’était-il déjà aventuré avec son album « The Genius of Ray Charles » sur le territoire de « Old Blue Eyes », avec des moyens similaires : reprises de standards em-pruntés au répertoire de Broadway et accom-pagnements orchestraux « de luxe » assurés, sur une face, par un big band de jazz de type Count Basie, et sur l’autre par un orchestre symphonique et une grande chorale. C’est surtout ce dernier type d’arrangements, où la voix et le piano de Ray se trouvaient noyés par des violons et un chœur séraphique, qui avait fait hurler à la trahison nombre des fans qu’il avait conquis avec son R’n’B pur et dur, à commencer par ceux de sa communauté d’origine, mais pas seulement : le traumatisme avait aussi durement touché jusqu’au cercle grandissant de ses admirateurs européens.

Apparemment indifférent à cette controverse – tout comme il l’avait été, six ans auparavant, devant les véhémentes protestations qu’avait suscitées auprès de beaucoup d’églises noires la fusion du blues (« la musique du diable ») et du gospel qu’il avait entreprise (signant ainsi au passage l’acte de naissance de la « Soul Music ») – Ray Charles allait appliquer sa nouvelle formule : 50 % orchestration jazz en big band / 50 % violons et choristes à la plupart de ses recueils des années 1960, avec de considérables succès (Georgia on my mind, Ruby, I can’t stop loving you…), mais sans abandonner pour autant sa production de R’n’B, devenue minoritaire et le plus souvent reléguée à des faces de 45 tours non reprises sur album.

Conséquence de l’éclatant « crossover » qu’il était en train de réaliser, celui que l’on surnommait désormais « the Genius » fit une courte apparition musicale dans la comédie hollywoodienne de série B « Swingin’ Along » et il se vit inviter à venir chanter dans de populaires émissions de télévision, parfois avec choc des cultures à la clé. Hugh Hefner, le patron du magazine Playboy, fut le premier à solliciter Ray pour apparaître dans son programme télévisé, façon club, « Payboy’s Penthouse ». En quartet, Ray y interpréta Georgia on my mind et Hallelujah I love her so devant un public ostensiblement appréciateur et participatif. Mais le grand moment comique vint lorsque le crooner Perry Como mit en présence, dans son show télévisé, le Genius (Ray Charles Robinson), et « l’autre Ray Charles » (Charles Raymond Offenberg), le leader de la chorale de variétés connue en tant que « Ray Charles Singers ». Leur collaboration sur Georgia on my mind est conforme à l’arrangement chargé du disque, mais que dire de la substitution des Ray Charles Singers aux Raelets à la fin de What’d I say ?

Aux antipodes de cette démarche de séduction d’un nouveau public « étranger », c’est pour se livrer aux deux formes de musique sans concession qu’il avait portées à un si haut niveau d’excellence au cours des années 1950 que, le 2 juillet 1960, Ray Charles était monté pour la deuxième fois sur la scène du Newport Jazz Festival à la tête de son octet et des Raelets : son jazz enflammé, qui n’avait rien à envier aux meilleures formations de « soul jazz » de l’époque, et son R’n’B gospelisant qui suscitait alors une sorte de possession collective de son auditoire, versant parfois dans l’hystérie.

En dehors de son déchirant soul-blues Drown in my own tears, qui constituait une pièce maîtresse de son répertoire depuis 1955, Ray avait essen-tiellement donné des interprétations de certains de ses 45 tours les plus récents, tels que My baby (I love her, yes I do), son ardent duo avec la soliste des Raelets, la grande Margie Hendrix, ou un Sticks and stones rivalisant dans l’excitation avec son déjà classique What’d I say, qui apparaît ici dans sa plus exaltante interprétation « live ». Débarrassé des cordes de la version studio, Don’t let the Sun catch you cryin’ se révélait aussi comme un chef d’œuvre de blues-ballad du Genius, traversé par un lumineux solo de piano du maître.

Outre qu’il nourrissait la partie R’n’B de sa musique, notamment en faisant appel à des harmonies riches, complexes, l’élément jazz était essentiel, en soi, à la musique de Ray Charles parce qu’il offrait aussi à ses musiciens, tous passionnés de bebop, comme il l’était lui-même, l’opportunité de s’exprimer en solo, plutôt que de ne faire qu’aligner des riffs derrière un chanteur. C’est un élément qui a certainement aidé Ray à attirer, et à garder sur la durée, des musiciens de la classe du trompettiste Phil Guilbeau ou des saxophonistes David « Fathead » Newman (auteur de la plupart des soli de ténor dans ses chansons R’n’B), Hank Crawford et Leroy Cooper. Newman et Crawford surent d’ailleurs mener par la suite de belles carrières personnelles, tandis que, moins entre-prenants mais non moins talentueux, Guilbeau et Cooper sont restés dans l’ombre.

C’est toujours à la tête de son octet que Ray Charles s’était produit en juillet 1961 – pour la première fois hors des Etats-Unis – au festival de jazz d’Antibes Juan-les-Pins, marquant la fin d’une époque, car c’est à la tête de son premier « big band » qu’il allait revenir en France trois mois plus tard.

La publication de la prestation de Ray Charles à Newport en 1960, tout comme, avant elle, celle enregistrée à ce même endroit en 1958 et celle d’Atlanta en 1959 (respectivement publiées par Atlantic sur les albums « Ray Charles at Newport » et « Ray Charles in Person »), ainsi que le DVD réunissant tout ce qui a survécu en vidéo de ses « sets » à Antibes en 1961 (« Ray Charles Live in France», Eagle Vision ) représentent d’inestimables témoignages de ce qui reste sans doute la musique la plus intensément personnelle qu’ait produite Ray Charles : celle du temps où il arrangeait la quasi-totalité de son répertoire, en écrivait une partie lui-même, et n’était pas avare de ses propres soli instrumentaux.

Une constante de ces enregistrements publics est que l’on y découvre toujours des morceaux qu’il n’a jamais enregistrés en studio. Ray estimait d’ailleurs avoir écrit une centaine d’arrangements qu’il avait interprétés sur scène sans les avoir jamais enregistrés. Des descriptions que lui-même ou ses musiciens donnaient parfois d’un show « standard » où ils jouaient pour la danse dans les années 1950 donnent un aperçu vertigineux de ce que nous avons manqué, car, semble-t-il, aucun de ses nombreux engagements de ce type n’a jamais fait l’objet d’un enregistrement : trois heures de scène, la première instrumentale avec Ray jouant de l’alto, la deuxième avec Ray au piano chantant des reprises, dont des succès R’n’B du moment, et la troisième (le summum) Ray interprétant les chansons de ses propres disques.

Lorsqu’il était parvenu à créer son big band à partir du noyau que constituait son octet, à l’automne 1961, Ray Charles avait notamment rameuté deux remarquables musiciens qui avaient contribué à des versions précédentes de son « small band » : le trompettiste Marcus Belgrave et le saxophoniste-ténor Don Wilkerson. C’est ce dernier qui avait joué les soli de ténor sur les disques de Ray en 1954-55, et il récupérait incidemment ainsi le privilège de rejouer son propre solo original sur Hallelujah I love her so, que David Newman avait pris l’habitude de jouer note-pour-note à sa place.

Quincy Jones avait considérablement aidé son ami Ray Charles (les deux musiciens s’étaient connus, adolescents, à Seattle en 1948) à monter son grand orchestre en lui donnant les partitions de son propre big band, qu’il venait de se résoudre à dissoudre faute d’engagements. Quincy avait également écrit de nouveaux arrangements, pour grand orchestre de jazz, pour les chansons que Ray avait enregistrées en studio avec des violons, comme Just for a thrill, Georgia on my mind ou Come rain or come shine.

Une importante sélection de morceaux des merveilleux concerts parisiens de Ray Charles en 1961 et 1962 a été publiée sur le coffret de 3 CD « Ray Charles Live in Paris 1961-1962 » (Frémeaux & Associés) et nous en proposons un complément dans ce double CD.

Au cours de ses concerts d’octobre 1961 au Palais des Sports, Ray avait joué de l’orgue Hammond à la place du piano – ceci pour la première et la dernière fois au cours d’une tournée européenne.

Les musiciens ayant influencé le subtil jeu de piano de Ray Charles sont bien connus : il citait fré-quemment les noms de Nat « King » Cole, Charles Brown, Oscar Peterson ou Hank Jones – et il convient d’y ajouter celui du pianiste de blues Lloyd Glenn, qui avait produit pour Swing Time les tous premiers disques de Ray, de 1949 à 1951. De même, ses influences au saxophone sont clairement identifiées : un peu de Louis Jordan et beaucoup de Charlie Parker. C’est sa fascination pour Parker qui avait décidé Ray à abandonner la clarinette (qu’il avait apprise en autodidacte par admiration pour Artie Shaw) en faveur du saxo-alto.

Il semble, par contre, que ce soit en l’absence de tout modèle que Ray Charles avait élaboré son jeu à l’orgue. Il y avait développé, par une utilisation toute personnelle des registres et une science de la montée et de la résolution des tensions (favorisée par la possibilité d’accords tenus), un style spécifique particulièrement envoutant. D’ailleurs son (alors récent) album « Genius + Soul = Jazz », où il jouait de l’orgue et ne chantait que sur deux titres, avait remporté un considérable succès pour un disque de jazz, tandis que le 45t One mint julep qui en était extrait avait atteint la 1ère place R&B et la 8ème place Pop au classement du magazine Billboard – une performance inédite pour un instrumental.

Ray Charles aura utilisé le saxophone-alto de façon moins éphémère que l’orgue Hammond, mais néanmoins très parcimonieuse à partir des années 1960. Ce n’est qu’en 1962 – et lors d’un unique concert – qu’il avait joué pour la première fois en France de cet instrument. Lorsque l’orchestre avait commencé à jouer et que le rideau s’était levé à l’Olympia, ce 21 mai 1962, les projecteurs avaient plongé sur le piano : vide… Ray se tenait debout au centre de la scène, jouant à l’alto la composition Blue stone de Hank Crawford (lequel allait bientôt se glisser au piano). Il s’agit de la seule version connue de ce thème par le Genius. Chorus après chorus inspiré, Ray Charles y délivrait ce qui est certainement sa plus belle interprétation à l’alto qui ait été enregistrée.

Si, au début de sa carrière, Ray Charles avait beaucoup imité deux chanteurs et pianistes pra-tiquant une tournure de blues-ballade sophistiquée, Nat King Cole et Charles Brown, à partir du moment où il avait pris la route en 1950 pour accompagner le chanteur et guitariste Lowell Fulson en tournée, Ray avait été quotidiennement impliqué dans une forme de blues plus âpre à laquelle il n’allait pas tarder à adhérer. D’autant plus qu’avec Lowell, ou plus tard, dans la période où il était musicien indépendant (1952-1954), Ray avait aussi eu l’opportunité de soutenir au piano d’autres grands bluesmen, comme T-Bone Walker, Big Joe Turner ou Guitar Slim. Et lors d’une tournée commune, en 1954, après son propre set, Ray, muni de son alto, se joignait même chaque soir à la formation du chanteur-harmoniciste Little Walter.

Par rapport à la totalité de l’œuvre publiée de Ray Charles, on ne peut que constater que – quan-titativement – les blues, au sens strict du terme, n’y tiennent pas une grande place, même si le blues suintait de tout ce qu’il a pu faire en musique, tant il était inexpugnable de sa voix et de son jeu sur tous les instruments qu’il pratiquait.

Lorsqu’il se livrait au blues sur scène – parfois après une adresse teintée d’ironie au public (« J’espère que vous me pardonnerez, mais je dois chanter un peu le blues. Je ne peux pas m’en empêcher ») – Ray s’y immergeait totalement, en faisant immanquablement un moment de grâce unique. Et il savait aussi investir d’un puissant caractère blues une ballade ou un standard de Broadway, comme il l’avait magistralement fait avec ce Come rain or come shine, au Palais des Sports le 21 octobre 1961, en complète communion avec le ténor lyrique de Don Wilkerson.

Ray Charles aimait à se définir comme un non-spécialiste, un « homme à tout faire » de la musique et il l’a surabondamment prouvé au cours d’une carrière professionnelle couvrant six décennies qui l’aura vu puiser régulièrement dans le répertoire de la Country Music (dont la popularité auprès du grand public américain lui doit beaucoup) tout comme dans celui des Beatles, et flirter plus furtivement avec le Gospel, les chants de Noël, et jusqu’au Disco et au Hip Hop.

Mais, sur scène, il n’avait jamais abandonné l’essence R&B et jazz de sa musique – dont la magie culminait dans les années 1950 et les premières années 1960.

Joël Dufour

© FRÉMEAUX & ASSOCIÉS 2016

Remerciements à :

Michel Brillié et Gilles Pétard, qui nous ont permis d’utiliser les enregistrements de Blue Stone

et Moanin’ appartenant à leur fonds Live in Paris / Body & Soul, ainsi qu’à Jean-Claude Alexandre, Peter Bürli, Jean Buzelin, Michelle Dufour, Jeff Helgesen, Jacques Périn (Soul Bag) et Bob Stumpel.

Ray Charles Live at Newport 1960 (plus bonus)

By Joël Dufour

The beginning of the 1960s had signa-led for Ray Charles (not without trouble) the establishing of the kind of crossover success that he had been yearning for – a goal also pursued by so many other Black popular artists for whom reaching the largest possible audience was a matter of survival.

While Ray Charles was already enjoying the recognition of a portion of the white teenagers crazy about Rock ’n’ Roll – who had been already dancing (more or less secretly) for several years to the sounds of his hits in the field of Rhythm ’n’ Blues (I got a woman, Hallelujah I love her so, What’d I say…) – he now wanted to reach the larger, more mature, public whose major idol was Frank Sinatra. Thus, as early as October 1959, he had already ventured on Old Blue Eyes’ territory with similar means: covering standards borrowed from the Broadway repertoire with “luxurious” orchestral accompaniments provided, on one side, by a Count Basie type jazz big band, and on the other side by a symphonic orchestra and a mass choir. It was particularly this latter type of arrangements, where Ray’s voice and piano were drown in violins and angelic voices, which had made roar treason many of the fans he had conquered with his pure and tough R ’n’ B, starting with the ones of his own community of origin, but not only them: the trauma had also harshly stricken all the way to the growing circle of his European admirers.

Seemingly unmoved by this controversy – like he had been, six years earlier, when he had faced the protests of many Black churches triggered by the fusion of the blues (“the Devil’s music”) and gospel music he had initiated (signing, in so doing, the birth certificate of “Soul Music”) – Ray Charles would apply his new formula: 50% big band jazz setting / 50% strings and choir to most of his albums of the 1960s, with considerable success (Georgia on my mind, Ruby, I can’t stop loving you…), yet without giving up his R ’n’ B output, now mostly relegated as single-only tracks.

As a consequence of the crossover triumph he was in the process of achieving, “the Genius”, as he was starting to be called, made a short musical appearance in the B-movie Hollywood comedy “Swingin’ Along” and he was invited to guest in popular television programs, sometimes not without cultural clashes. Hugh Hefner, the boss of the Playboy magazine, was the first one to ask Ray to feature in his “club” TV program “Playboy’s Penthouse”. Heading a trio, Ray sang versions of Georgia on my mind and Hallelujah I love her so before an ostensibly appreciative and participative audience. But the big funny moment came when the crooner Perry Como introduced in his TV show the Genius (Ray Charles Robinson) to “the other Ray Charles” (Charles Raymond Offenberg), the leader of the pop choir known as “The Ray Charles Singers”. Their collaboration on Georgia on my mind conforms to the heavy arrangement of the studio version, but what can one say of the substitution of the Ray Charles Singers to the Raelets at the end of What’d I say?

At the very opposite of this attempt at luring a new “alien” audience, it was to devote himself to the two forms of uncompromising music he had elevated to such a level of excellence during the 1950s that, on July 2, 1960, Ray Charles had hit the stage of the Newport Jazz Festival at the head of his octet and Raelets: his passionate jazz, on par with the best “soul jazz” bands of the time, and his gospel drenched R ’n’ B which was arousing a sort of collective possession of his audience, sometimes drifting into hysteria.

Aside from his heart-rending soul-blues Drown in my own tears, which constituted a mainstay of his repertory, Ray had mostly offered renditions of songs from some of his most recent singles, such as My baby (I love her, yes I do), his burning duet with the Raelets soloist, the great Margie Hendrix, or a version of Sticks and stones competing in excitement with his already classic What’d I say, which appears here in its most intoxicating live version. Cleared of the strings of the studio version, Don’t let the Sun catch you cryin’ was revealing itself as a masterpiece of a blues-ballad by the Genius, crossed by a bright piano solo by the master.

Besides nourishing the R ’n’ B part of his music, notably by relying on rich, complex harmonies, the jazz element was essential, in itself, to Ray Charles’ music because it was offering his musicians, all of them fervent bebop lovers, as Ray was himself, opportunities to express themselves as soloists, rather than being restricted to playing riffs behind a singer. It is an element which has certainly helped Ray Charles to attract, and retain for years, musicians of the caliber of trumpet player Phil Guilbeau or of saxophonists David “Fathead” Newman (who was playing most of the tenor solos on his R ’n’ B songs), Hank Crawford and Leroy Cooper. Moreover Newman and Crawford subsequently embarked in fruitful personal careers, while, less enterprising but no less talented, Guilbeau and Cooper remained in the shadow.

It is still heading his octet that Ray Charles had performed in July 1961 – for the first time outside of the U.S.A. – at the Antibes Juan-les-Pins Jazz Festival in France, marking the end of an era, since it was at the head of his first big band that he was to come to France again three months later.

The release of Ray Charles’ set at Newport in 1960, just like, before it, the one recorded at the same place in 1958 and the one of Atlanta in 1959 (respectively published by Atlantic on the albums “Ray Charles At Newport” and “Ray Charles in Person”), as well as the DVD gathering all of what had survived on video of his sets at Antibes in 1961 (“Ray Charles Live in France”, Eagle Vision) represent invaluable testimonies of what probably remains the most intensely personal music that Ray Charles ever made: the one of the period of time when he was arranging almost all of his catalogue, writing part of it himself, and abundantly playing as a soloist.

A constant feature of those live recordings is that one would always discover tunes that Ray Charles had never recorded in the studio. Besides, Ray estimated that he had written about one hundred arrangements which he had played on stage but never recorded. Descriptions that he or his musicians were sometimes making of a typical show where they would play for dances in the 1950s provide an awesome glimpse at what we have missed, since, apparently, none of his numerous gigs of this sort has ever been recorded: three hours of show, the first hour purely instrumental with Ray blowing his alto-sax, the second hour with Ray at the piano singing covers, including current R ’n’ B hits, and the third hour (the climax) with Ray performing songs of his own records.

When building his big band around the nucleus of his octet, during the fall of 1961, Ray Charles had in particular called back two remarkable musicians who had been part of previous versions of his “small band”: trumpet player Marcus Belgrave and tenor saxophonist Don Wilkerson. It is the latter who had played the tenor solos on Ray’s records in 1954-55, and he would thus retrieve the pleasure of playing his original solo on Hallelujah I love her so that David Newman had become used to playing note-for-note in his place.

Quincy Jones had tremendously helped his friend Ray Charles (the two musicians had met when they were both teenagers in Seattle in 1948) to organize his big band by giving him the scores of his own big band, which he had been forced to give up because he wasn’t able to find enough gigs for it. Quincy had also written new arrangements, for a jazz big band, for those songs that Ray had recorded in the studio with strings, such as Just for a thrill, Georgia on my mind or Come rain or come shine.

A hefty selection of songs from the wonderful Ray Charles concerts in Paris in 1961 and 1962 has been released on the 3 CD box set “Ray Charles Live in Paris 1961-1962” (Frémeaux & Associés) and we now propose a supplement in this double CD.

During his October 1961 concerts at the Palais des Sports in Paris, Ray had played the Hammond organ instead of piano – for the first and last time during an European tour.

The musicians who have influenced Ray Charles’ subtle piano playing are well known: he used to frequently mention the names of Nat “King” Cole, Charles Brown, Oscar Peterson or Hank Jones – and it is essential to add the one of blues pianist Lloyd Glenn, who had produced for the Swing Time label Ray’s very first records, from 1949 to 1951. Likewise the influences on his saxophone playing are clearly identified: a little bit of Louis Jordan and a whole lot of Charlie Parker. It is his fascination for Parker which had decided Ray to give up the clarinet (which he had learnt to play by himself out of admiration for Artie Shaw) in favor of the alto saxophone.

On the contrary, it is seemingly without any model that Ray Charles had worked up his way of playing the organ. On that instrument, he had developed, through a very personal use of drawbar settings and an art for building and resolving tensions (facilitated by the possibility of sustaining chords), a particularly mesmerizing specific style. Besides his (then recent) album “Genius + Soul = Jazz”, where he was playing organ and on which he sang only two songs, had attained a huge success for a jazz record, while the single track One mint julep extract from it had reached #1 R&B and #8 Pop in the charts of the Billboard magazine – an unheard of feat for an instrumental tune.

While Ray Charles’ practice of the alto-saxophone has been less short-lived than his use of the Hammond organ, ever since the early 1960s he scarcely blew his horn anymore. It’s only in 1962 – and in the course of a single concert – that he had played his alto for the first time in France. That May 21, 1962, at the Olympia theater, when the band had started playing and the curtain had lifted, the spotlights had focused on the piano: empty… Ray was standing center stage, playing on his saxophone Hank Crawford’s tune Blue Stone (Hank would soon slide at the piano). It is the only known version of that tune by the Genius. Chorus after inspired chorus, Ray Charles was delivering what certainly remains his most beautiful interpretation at the alto which has been recorded.

Although, at the beginning of his career, Ray Charles had abundantly imitated two singers and pianists performing a kind of sophisticated blues-ballad style, Nat King Cole and Charles Brown, when he had started touring in support of singer-guitarist Lowell Fulson, Ray had been involved every day in a harsher form of blues to which he would soon adhere. Moreover, with Lowell, or later on during the period of time when he was

a freelance musician (1952-1954), Ray also had the opportunity of backing on piano other great bluesmen, such as T-Bone Walker, Big Joe Turner or Guitar Slim. Also, during a 1954 tour, every evening after having played his own set at the piano, Ray would step again on stage, this time with his alto-sax, to join forces with the band of harmonica player and singer Little Walter.

With regard to Ray Charles’ whole released body of work, one can only notice that, quantitatively, the blues – in the strict meaning of this word – do not hold an important place in it, even though a blues feeling imbued all he has ever done in music, as it was inex-pugnable from his voice as well as of his playing on whatever instrument he used.

When he sang the blues on stage – sometimes after a statement marked with irony to the public (“I hope you forgive me, but I must play some blues. I can’t help it”) – Ray would dive into it entirely, always making such a moment unique. He knew as well how to infuse a ballad with a tough blues feeling, as he had done in Paris on October 21, 1961, with Come rain or come shine, in complete communion with Don Wilkerson’s lyrical tenor-sax.

Ray Charles liked to define himself as a non-specialist, a “utility man” in music, and he more that abundantly proved that during a career covering six decades during which he would steadily dig into the Country Music repertory (the popularity of which owes him a lot) as well as in the Beatles songbook, and flirt with Gospel, Christmas songs, and even Disco and Hip Hop. Yet, on stage, he had never given up the R&B and jazz spirit of his music – the magic of which culminated in the fifties and early sixties.

Joël Dufour

© FRÉMEAUX & ASSOCIÉS 2016

Thanks to:

Michel Brillié and Gilles Pétard – who allowed us to use the recordings of Blue Stone and Moanin’ which are part of their Live in Paris / Body & Soul collections – as well as to Jean-Claude Alexandre, Peter Bürli, Jean Buzelin, Michelle Dufour, Jeff Helgesen, Jacques Périn (Soul Bag) and Bob Stumpel.