- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

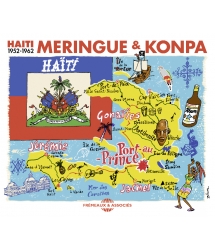

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

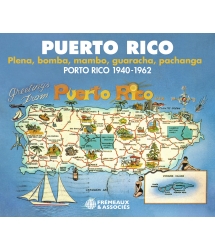

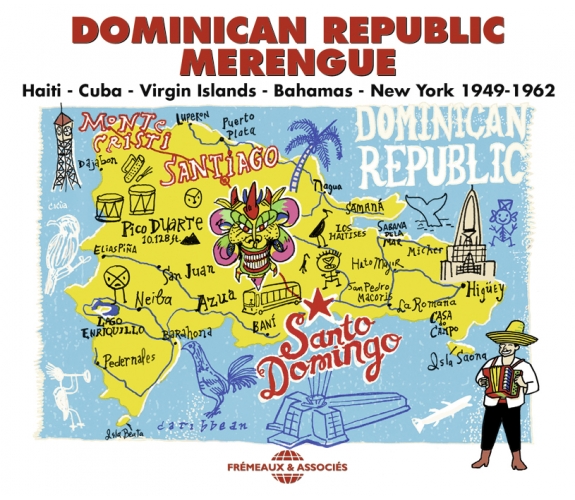

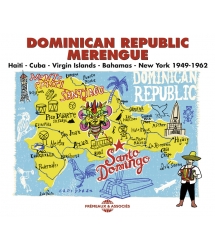

HAITI - CUBA - VIRGIN ISLANDS - BAHAMAS - NEW YORK 1949-1962

Ref.: FA5450

EAN : 3561302545028

Artistic Direction : BRUNO BLUM

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Total duration of the pack : 3 hours 17 minutes

Nbre. CD : 3

HAITI - CUBA - VIRGIN ISLANDS - BAHAMAS - NEW YORK 1949-1962

HAITI - CUBA - VIRGIN ISLANDS - BAHAMAS - NEW YORK 1949-1962

After its eclosion in Santo-Domingo, merengue established its supremacy as Latin dance-music. Dominican musicians in exile in New York propagated the genre further, and their orchestras contributed to the great Latin wave which swept over the Fifties. A style as fabulous as it is little-known, at the root of kompa music, pachanga, bachata, bomba and salsa, this authentic merengue music was one of the most influential styles of its time, and one of the great gems of the Caribbean. This anthology compiled by Bruno Blum with a detailed commentary contains treasures which have eluded many for almost a half century. Patrick FRÉMEAUX

GOOMBAY - AVEC BLIND BLAKE, GEORGE SYMONETTE, CHARLIE...

THE KINGSTON RECORDINGS 1951-1958

Lord Kitchener, Mighty Sparrow, Lord Invader, King...

ROOTS OF RASTAFARI 1939 - 1961

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1A Lo OscuroAngel Viloria y su Cunjunto Tipico CibaenoTraditionnel00:03:001950

-

2El VironayAngel Viloria y su Cunjunto Tipico CibaenoRafael Igniacio00:03:021950

-

3Oye Mi NegraDoris Vallidares y Su Conjunto Tipico CibaneoAngel Viloria00:02:451953

-

4El TapadorDoris Vallidares y Su Conjunto Tipico CibaneoAngel Viloria00:02:461953

-

5LoretaDoris Vallidares y Su Conjunto Tipico CibaneoLuis Alberti00:02:571950

-

6Te Van A PegarDoris Vallidares y Su Conjunto Tipico CibaneoDioris Valladares00:02:561950

-

7Volvimos De NuevoGuandulito y Su Conjunto Tipico CibaneoJovina Lambardi00:02:451952

-

8El Secreto De SandyDoris Vallidares y Su Conjunto Tipico CibaneoDioris Valladares00:02:491956

-

9AprietameDoris Vallidares y Su Conjunto Tipico CibaneoMario De Jesus00:03:021950

-

10Limpiando La HebillaLuis Kalaff y sus Alegres DominocanosLuis Kalaff00:02:361962

-

11Tu Si Sabes Come FueLuis Kalaff y sus Alegres DominocanosLuis Kalaff00:02:541962

-

12Compadre Pedro JuanNini Vasquez y Sus RigolerosLuis Alberti00:03:561962

-

13Pa Despues Venir LlorandoLuis Kalaff y sus Alegres DominocanosLuis Kalaff00:02:371962

-

14Juana MariaLuis Kalaff y sus Alegres DominocanosLuis Kalaff00:02:491961

-

15Lengua LargaAngel Viloria y su Cunjunto Tipico CibaenoAngel Viloria00:03:041950

-

16FiestaJuanito Sanabria and his OrchestraLuis Alberti00:02:431949

-

17El Negrito Del BateyJuanito Sanabria and his OrchestraMedardo Guzman00:03:031949

-

18Pan CalienteLuis Quintero y Su Conjunto Alma CibaenaAntonio Perdomo00:02:431962

-

19Alabao Sea DiosLuis Kalaff y sus Alegres DominocanosLuis Kalaff00:02:411962

-

20Ahora Me Viene LlorandoLuis Kalaff y sus Alegres DominocanosLuis Kalaff00:02:171962

-

21Consigueme EsoAngel Viloria y su Cunjunto Tipico CibaenoN. Perez Pedro00:03:091950

-

22RosauraAngel Viloria y su Cunjunto Tipico CibaenoTraditionnel00:03:081950

-

23Senor PoliciaLuis Kalaff y sus Alegres DominocanosLuis Kalaff00:02:481962

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Ti Yaya TotoJean-Baptiste Nemours et son Ensemble aux CalebassesNemours Jean Baptiste00:03:431959

-

2La EmpalizaThe La Motta Brothers Virgin Iles Hotel OrchestraLuis Kalaff00:02:411956

-

3La CruzAndré ToussaintLuis Kalaff00:02:241956

-

4Por Culpa De Un SaxofonDoris Vallidares y Su Conjunto Tipico CibaneoDe Jesus Mario00:02:521956

-

5El FucuLuis Kalaff y sus Alegres DominocanosLuis Kalaff00:02:371962

-

6Cada Tierra Con Su RitmoLuis Kalaff y sus Alegres DominocanosLuis Kalaff00:02:461962

-

7El Jarro PichaoAngel Viloria y su Cunjunto Tipico CibaenoC. Rodriguez00:02:471950

-

8Me Caso A Los 36Juanito Sanabria and his OrchestraMario De Jesus00:02:481949

-

9Fiesta En La JovaAntonio MorelF. Lopez00:02:461949

-

10Ay Mi VidaDoris Vallidares y Su Conjunto Tipico CibaneoManolin Morel00:02:391956

-

11Midnight MerengueBill La MottaBill La Motta00:02:441959

-

12Contestation De El MarineroCelia CruzTete Cabrera00:02:371956

-

13El MerengueCelia CruzNarciso Aguero00:03:011956

-

14GrateyDoris Vallidares y Su Conjunto Tipico CibaneoReyes Alfau Radames00:02:521956

-

15SeveraLuis Quintero y Su Conjunto Alma CibaenaPalenque00:03:041962

-

16La PesadillaLuis Quintero y Su Conjunto Alma CibaenaEmilio Nunez00:02:561962

-

17Madora Che CheLuis Kalaff y sus Alegres DominocanosLuis Kalaff00:02:451962

-

18Que PaquetonLuis Quintero y Su Conjunto Alma CibaenaEmilio Nunez00:02:361956

-

19Los Dos MerenguesDoris Vallidares y Su Conjunto Tipico CibaneoAna Muriel00:03:031956

-

20Compai CucuDoris Vallidares y Su Conjunto Tipico CibaneoTraditionnel00:02:561956

-

21Chauflin'Damiron y ChapuseauxTraditionnel00:01:511958

-

22Seguire A CaballoOrquesta Presidente Trujillo Rafael MartinezTraditionnel00:03:151958

-

23Al Compas Del MerengueThe La Motta Brothers Virgin Iles Hotel OrchestraNelson Noriega00:02:591956

-

24Poor Man's MerengueBill La MottaBill La Motta00:03:361959

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Las BatatasDoris Vallidares y Su Conjunto Tipico CibaneoEfrain Rivera00:02:541956

-

2San CristobalAntonio MorelEnriquillo Sanchez00:03:561958

-

3Cana BravaAntonio MorelT. Abreu00:02:311960

-

4CayetanoAntonio MorelPerez Prado00:02:481960

-

5La ParrandaAntonio MorelInconnu00:01:561958

-

6El ErvoltosoAntonio MorelA. Cruz00:03:081958

-

7La Salve De Las AntillasLuis Kalaff y sus Alegres DominocanosLuis Kalaff00:02:311962

-

8Los GuandulitosAntonio MorelL. Perez00:03:081954

-

9Fingido AmorAntonio MorelA. Parahoy00:02:151957

-

10Arroyito CristalinoAntonio MorelArcadio Franco00:03:071961

-

11El Guapo De La SierraAntonio MorelJ.A. Hernandez00:02:591958

-

12El MarineroDamiron y ChapuseauxR. Rico00:02:491962

-

13Sina JuanicaAntonio MorelF. Lopez00:02:361954

-

14El CompayAntonio MorelMolina Y Pachero Ramon00:02:301955

-

15Arroyuto CristalinoAntonio MorelFranco Arcadio00:02:031961

-

16El MonoAntonio MorelQ. Fernandez00:02:261959

-

17La CachuchaJuanito Sanabria and his OrchestraN. Perez Pedro00:02:541949

-

18Virgencita Del ConsueloAntonio MorelAntonio Morel00:02:321959

-

19La MechaLuis Kalaff y sus Alegres DominocanosLuis Kalaff00:02:551962

-

20Rio Abajo VoyLuis Kalaff y sus Alegres DominocanosLuis Kalaff00:02:191962

-

21Ahi Viene La NenaLuis Kalaff y sus Alegres DominocanosLuis Kalaff00:02:471962

-

22Cadena Morel n°3Antonio MorelTraditionnel00:03:261961

-

23Los SaxofonesAntonio MorelRafael Vasquez00:01:561961

CLICK TO DOWNLOAD THE BOOKLET

Dominican Republic Merengue

DOMINICAN REPUBLIC MERENGUE

Haiti - Cuba - Virgin Islands - Bahamas - New York 1949-1962

Dominican Republic - Merengue

Haiti - Cuba - Virgin Islands - Bahamas - New York 1949-1962

Par Bruno Blum

Le merengue a une histoire atypique : il était presque impossible pour les musiciens d’enregistrer leur musique en République Dominicaine même. Malgré leur popularité, le matériel d’enregistrement était peu disponible. En outre, la tyrannie autocratique de Rafael Trujillo (au pouvoir de 1930 à 1961) a incité nombre des meilleurs musiciens à l’exil. C’est à New York que la petite diaspora dominicaine a principalement trouvé refuge. À partir de 1949 les musiciens ont accédé à une production de disques de qualité, notamment pour les marques new yorkaises Ansonia (fondée par Rafael Pérez Dávila en 1949) et Seeco (fondée par Sidney Siegel en 1943). Ainsi avec le succès des enregistrements de formations dont la première fut celle de l’accordéoniste Angel Viloria avec le chanteur Doris Valladares, le merengue a pu rayonner à travers les Caraïbes latines dès le début des années 1950. Comme les Îles Vierges1, Porto Rico faisait partie du territoire des États-Unis. Les musiciens dominicains étaient particulièrement appréciés par leurs voisins portoricains, nombreux à New York. Les orchestres portoricains et cubains de son, mambo, cha-cha-cha et autres musiques latines à la mode dans les années 1950 ont vite repris le merengue à leur compte et des artistes célèbres comme Xavier Cugat ou Celia Cruz ont enregistré dans ce style en y ajoutant leur couleur locale. Après l’avènement du calypso2 et du rock ‘n’ roll3 en 1956, les musiques latines ont continué à prospérer. Irrésistiblement dansant, l’influent merengue authentique entendu ici constitue l’une des principales racines du compas haïtien et de la salsa, un genre qui s’est par la suite développé dans la communauté latine de New York — et portoricaine en particulier. Méconnu malgré son succès depuis les années 1970, le véritable merengue est l’héritier d’une tradition qui remonte au XVIIe siècle. Cet album réunit un florilège de son vrai âge d’or, les années 1950.

Contredanse à Saint-Domingue

Située au sud-est des côtes de la Floride, la République Dominicaine est le plus vaste territoire des Caraïbes après sa voisine Cuba. L’île fut appelée Hispaniola par Christophe Colomb en 1492 et Saint-Domingue par les Français, qui la disputaient aux Espagnols. Les Indiens Taïnos de langue arawak ont été anéantis par la colonisation espagnole et les épidémies venues d’Europe. Mais le métissage était très répandu et nombre de Dominicains ont des ancêtres amérindiens. La déportation à Saint-Domingue d’Africains réduits en esclavage a été massive à partir du XVIe siècle, créant au passage la catégorie des zambos (Africains métissés avec des Taïnos). Première colonie importante du nouveau monde, la ville de Saint Domingue s’est développée rapidement. Elle contient un quartier colonial du XVIe siècle où trône la plus ancienne cathédrale chrétienne des Amériques. Elle fut la première base militaire des conquêtes espagnoles aux Caraïbes, en Amérique Centrale et en Amérique du Sud.

Selon le saxophoniste et ethnomusicologue Paul Austerlitz dont le remarquable travail sur l’histoire du merengue fait autorité4, les « danses des campagnes » (country dance) connurent une vogue dans la noblesse britannique. Les nobles les ont adaptées aux salons des aristocrates de la cour de Charles II. Le roi de France Louis XIV était friand de nouvelles danses et au milieu du XVIIe siècle il adopta ces country dance anglaises (appelées phonétiquement « contredanses » en France) à sa cour au château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye. Elles avaient pour nouveauté et particularité d’être dansées par des couples libres, ce qui contrastait avec la pratique habituelle des danses en groupe. L’Espagne céda l’ouest de l’île Hispaniola à la France en 1697. La variante française de la contredanse prit alors sa place dans les salons coloniaux de Port-au-Prince. Comme d’autres musiques d’origine européenne, la contredanse était aussi jouée par les esclaves musiciens à la demande de leurs maîtres. Elle fut vite adoptée par les Dominicains d’origine africaine, pour qui la musique représentait une forme de liberté5. Ils en créèrent une version afro-américaine populaire, notamment la danse et le rythme « carabinier » à l’origine du meringue de l’ouest de l’île, futur Haïti (« mereng » selon l’orthographe anglaise). Ainsi dès le XVIIe siècle la colonie française de Saint-Domingue était vraisemblablement le cadre de danses afro-américaines préfigurant les danses en couple très libres du XXe siècle.

Trop occupée par l’invasion de l’Amérique du Sud, l’Espagne céda l’est de l’île à la France en 1795. Entretemps, dans l’élan de la révolution française de 1789, l’ouest de l’île obtint son indépendance au terme d’une longue et sanglante révolte d’esclaves menée par Toussaint-L’Ouverture. Indépendant depuis 1804, ce territoire devint la république d’Haïti. Fondé par d’anciens esclaves, Haïti fut la première république des Caraïbes, la première république noire du monde et la deuxième démocratie d’Amérique. En conséquence, l’île a été partagée en deux parties : après l’indépendance de Haïti, l’est de l’île et sa capitale Saint-Domingue sont restés français.

Merengue, carabinier et danza

La tourmente de la révolution haïtienne a poussé nombre de Français à fuir. Beaucoup partirent avec leurs esclaves vers les Caraïbes espagnoles (Cuba, Porto Rico), où la contredanse se répandit aussitôt — à moins que ce soit l’inverse, car l’influence de la contradanza pourrait bien être venue des Antilles espagnoles jusqu’à Haïti. Le terme espagnol « merengue » trouve en tous cas son étymologie dans la meringue, une pâtisserie française : peut-être est-ce parce que battre les œufs en neige nécessite d’agiter le corps frénétiquement ; quant au sucre de la recette, il était un produit des Antilles. Les contredanses (contradanza en espagnol) et leur dérivé haïtien, le carabinier, sont vraisemblablement à la racine des rythmes et des styles proches du merengue qui se développèrent dans la région des Caraïbes (notamment la danza à Porto Rico et Cuba) et accoucheront en fin de compte de plusieurs styles majeurs traités dans le paragraphe « influences du merengue » en fin de livret. Ils se sont ensuite cristallisés au XIXe siècle à Saint-Domingue sous le nom de merengue, un style populaire et rural qui tranchait avec les contredanses de salon. Au fil des années les Haïtiens ont tenté d’étendre leur révolution à l’est. Des guerres et massacres répétés ont installé une haine féroce entre les deux parties de l’île, dirigées par des Noirs à l’ouest et des Blancs à l’est. C’est finalement avec le soutien de Haïti et de la Grande-Bretagne que les Espagnols ont repris le contrôle de l’est de l’île en 1821. Les rythmes originels du merengue étaient donc interprétés bien avant l’indépendance de la République Dominicaine en 1844. Distinct du merengue classique au rythme 2/4 contenu dans l’essentiel de cet album, le style carabinier restera partie intégrante du merengue dans son ensemble et habite cet album à la fois par son influence mélodique et rythmique. Tu Ti Sabes Como Fue en est ici une incarnation dans le style merengue.

Sur l’île voisine de Porto Rico, une variante de la danza cubaine, appelée l’upa, a été apportée par des régiments cubains en 1842 et 1843. Critiquée pour sa danse en couple jugée trop libre et trop lascive, l’upa y a été interdite en 1849 sous peine d’amende pour ceux qui l’accueillaient et de prison pour les danseurs (l’upa disparaîtra après les années 1870). Une longue tradition esclavagiste considère les musiques et danses afro-américaines vulgaires, débauchées et incompatibles avec la religion. À Cuba la danza d’origine afro-haïtienne, a également été censurée. Le même sort attendait le merengue au Venezuela, où il fut interprété avant de disparaître avant la fin du XIXe. Mais comme le meringue haïtien, la danza cubaine (et le danzón cubain sur lequel on dansait le paseo en groupe) devinrent des repères identitaires afro-caribéens. Le merengue dominicain n’a pas échappé à ce symbolisme nationaliste pan-caribéen. Dénoncé par les sociétés coloniales pour sa sensualité et sa danse en couple, il était apprécié par le peuple pour cette même raison. À l’indépendance de la République Dominicaine en 1844, il était déjà indissociable de l’identité nationale. Juan Bautista Alfonseca fut vraisemblablement le premier compositeur de merengue dont le nom ait été retenu. Alfonseca a fait partie du mouvement d’indépendance et il composa dans différents styles, dont la mangulina (une autre musique et danse locale). La mangulina (et non le merengue) donna son rythme au premier hymne national, qu’il composa dans ce style local qu’il voulait valoriser.

La plupart des sources écrites du XIXe siècle critiquent durement le populaire merengue. Elles dénoncent sa danse, qui incluait parfois des mouvements de bassin suggestifs, considérés inconvenants, dégradants. Indifféremment appelée danza ou merengue, cette musique était vue comme une méprisable expression afro-américaine dans un pays où la haute société haïssait la négritude haïtienne toute proche et où l’on admirait les cultures française et espagnole. Pourtant la population de Saint-Domingue était issue du métissage de populations d’origines majoritairement africaine et indigène. Mais la société blanche au pouvoir imposait une identité européenne à la nation et le merengue était exclu des musiques de salon. Ce paradoxe montre aussi à quel point il était apprécié dans les bals populaires ruraux. Il y était joué avec des cordes dont le violon, la guitare, la mandoline, le tiple ou tiplet, le cuatro, une flûte et des percussions incluant le tambourin (pandereta). Présent dans les musiques portoricaines et latino-caribéennes en général, le merengue était joué au güiro caribéen d’origine africaine : une calebasse évidée et cannelée. La calebasse deviendrait plus tard un tube-grattoir de métal symbolique du merengue, frotté à l’aide du gancho ou pùa, trois ou quatre baguettes de métal plantées dans un socle muni d’une poignée de bois (voir photo du groupe de Luis Kalaff). Également présents, la timbale et la tambora, un tambour spécifique au merengue. Il fut d’abord joué sur les genoux au XIXe siècle, puis accroché autour du cou par une sangle et frappé par une baguette d’un côté et par la main de l’autre (voir photo de Luis Quintero). Après la « guerre de restauration » qui repoussa une invasion espagnole (1863-1865), la clarinette et le baryton militaire sont apparus dans des groupes ruraux qui voulaient ressembler aux élégantes formations des salons de la ville. Ces instruments à vent ont également joué un rôle dans la danza portoricaine et le meringue haïtien analogues. Quand les circonstances le permettaient, le piano était aussi utilisé. Comme partout dans les Caraïbes, de la Louisiane au Venezuela des musiques européennes — ici la contredanse — se sont transformées. Elles ont d’abord traversé les centres urbains coloniaux avant de se disséminer dans les campagnes où elles ont été soumises à la créativité et aux influences diverses des artistes locaux. Ce fut le cas avec le quadrille, la polka, le schottische, la mazurka, le boléro, la valse, les cantiques et d’autres musiques européennes qui ont pris racine aux Amériques. Elles ont fourni le terreau d’où ont surgi les musiques afro-américaines comme les negro spirituals, le calypso, le merengue, le son, puis le jazz ou le gospel. En Europe même, la valse était parfois considérée comme inconvenante ; elle également a connu une incarnation créole dans toute la région des Caraïbes. Son rythme ressemble à une forme de merengue « carabiné » dont les Tu Si Sabe Come Fue et Madora Che Che de Luis Kalaff sont des exemple parlants, propices aux pas de la mangulina, une danse dominicaine effectuée en groupe.

Merengue cibaeño

La contredanse/danza/meringue/merengue étaient joués dans toute la République Dominicaine. Mais c’est plus particulièrement dans la région paysanne de Cibao, très peuplée, que s’est affirmé un nouveau son, celui de l’accordéon rythmé par la güira (au swing ternaire) et la tambora. L’accordéon s’y est répandu progressivement à partir de 1870. Les négociants Allemands achetaient rhum et tabac à Saint-Domingue où ils exportaient aussi leurs accordéons. Considéré comme un instrument peu élaboré (car ne produisant qu’une seule gamme majeure), il a été très critiqué par ceux qui lui préféraient les cordes, plus raffinées. Plusieurs chansons ont fait allusion à ce différend stylistique. Mais bien qu’il ne puisse jouer les morceaux en mode mineur composés dans le passé, l’accordéon s’est imposé dans la région de Cibao. Les morceaux évoquaient des événements divers. Ils étaient souvent déférents à l’égard des caudillos, les dirigeants de la région qu’ils saluaient et glorifiaient.

La politique économique du dictateur Ulises Heureaux, au pouvoir de 1886 à 1899, a ruiné le pays au point que ses créanciers européens ont envoyé des navires de guerre pour obtenir paiement. Les États-Unis ont perçu ces mouvements de troupes européennes comme une menace à leur contrôle du très stratégique canal de Panama en construction. Un accord ouvrit en 1905 le contrôle des finances dominicaines aux États-Unis, qui partagèrent le produit intérieur du pays entre les créanciers étrangers et la population. Cette atteinte à la souveraineté du pays a créé de fortes tensions intérieures et mené à une occupation états-unienne de 1916 à 1924 (Haïti a été occupé pendant la même période). Les autorités militaires américaines étaient détestées et le nationalisme dominicain s’est exacerbé sous différentes formes : guérilla contre les marines américains à l’est mais aussi valorisation de la culture du pays, dont le merengue « typique » de la région de Cibao (merengue cibaeño) est devenu un des symboles. La capitale régionale Santiago de los Caballeros était emblématique du développement de ce merengue folklorique. Ce sont les formations d’accordéonistes, dont les vedettes Francisco « ñino » Lora et Antonio « Toño » Abreu, qui ont donné forme au merengue moderne avec accordéons à deux rangs de touches (capables de produire des gammes mineures), güira en métal (le güiro est la version en calebasse) et tambora jouée avec la paume de la main gauche en plus de la baguette. À partir de 1910 environ, le saxophone alto a progressivement remplacé le rôle rythmique du baryton. Sous l’influence d’Avelino Vásquez et Pedro « Cacù » Lora le style du saxophone merengue s’est développé. Il participera beaucoup à l’efficacité de cette musique, comme on peut l’entendre ici avec Ramon E. Gomez dans l’orchestre d’Angel Viloria vers 1950. Mais le saxophone était rare dans les zones rurales et n’était pas considéré comme típico dans les campagnes. Pourtant à Cibao le merengue urbain de Santiago (souvent avec sax) était tout autant «typique» et son essor a été important dans le succès de ce genre musical. Il était interprété à l’occasion de festivités diverses (combats de coq, bals, dates importantes et dans les bordels) sur des pistes de danse impeccables. Les danseurs cibaeños mettaient leurs plus beaux habits et portaient des chaussures même dans les régions les plus rurales. En ville, toutes les classes de la société participaient aux danses de fin de semaine, les pasadías, au point que le merengue est devenu un ciment unitaire pour la population de la région. La séduction passait par la danse, où l’homme effectuait des pas qui lui permettaient de briller. Entraînant, le tempo du merengue accélèrera progressivement dans les années 1950-60 jusqu’à atteindre des vitesses supersoniques par la suite mais au début du XXe siècle le tempo était assez lent. Il se décomposait en trois parties : une courte introduction invitait les danseurs en annonçant le début de la danse (le paseo des dix premières secondes de Compadre San Juan en est un bon exemple), puis la « première partie » merengue suivie du jaleo répétitif, qui utilise le principe de l’appel-réponse caractéristique des musiques afro-américaines, où les saxophones jouaient un rôle rythmique particulier. C’est dans cette « deuxième partie » où les solistes s’envolaient que la frénésie s’emparait de l’orchestre et des danseurs endimanchés. Comme ailleurs dans les Caraïbes, les bals populaires étaient des événements, de véritables spectacles mettant en valeur les participants. Les meilleurs chanteurs étaient capables d’improviser des paroles commentant les questions d’actualité. À la demande de l’intéressé (e), ils pouvaient imaginer des chansons incitant une personne à en marier une autre. Les politiciens étaient couramment critiqués ou félicités. Desiderio Arias, un leader de Cibao très populaire avant l’invasion américaine de 1916, était fréquemment cité dans les chansons. Dans les bordels, les paroles décrivaient parfois des femmes sans vertu. Pendant les années 1920, des sociétés américaines (dont Victor) ont réalisé les premiers enregistrements de merengue/danza à New York. Le merengue était néanmoins un vecteur culturel de résistance à l’occupation états-unienne. Les Américains étaient moqués et menacés sur « La Protesta », rarement joué devant les intéressés ; le style « pambiche » (Palm Beach prononcé à l’espagnole) fut même inspiré par les danses maladroites des forces d’occupation, leurs one-step et autres fox-trots. Les musiques folkloriques dominicaines ont peu à peu été écoutées d’une oreille romantique et après le départ des Américains en 1924 le mouvement nationaliste dominicain a largement utilisé les mélodies traditionnelles du merengue cibaeño comme véhicule d’une idéologie patriote. De nouvelles paroles, nationalistes ou non, ont été adaptées à des airs populaires érigés en trésors du patrimoine. Luis Alberti a par exemple signé la mélodie traditionnelle de Compadre Pedro Juan (la version incluse ici est interprétée par l’orchestre de ñiñi Vasquez) après l’avoir adaptée à un rythme lié à la tradition latino-caribéenne du rythme cinquillo. Une forte influence mexicaine a aussi contribué à nourrir la chanson dominicaine au XXe siècle. Les élites comme le peuple affichaient leur nationalisme, ce qui a miné le moral des occupants américains. Les musiques américaines étaient boycottées. De façon analogue, la culture populaire vaudou avait porté la révolution haïtienne — et la danza du peuple a été associée aux mouvements indépendantistes de Cuba et Porto Rico.

Merengue art officiel

Le merengue était pestiféré dans les bals de salon où le danzón cubain était joué pour la haute société par des orchestres avec instruments à vent (sans accordéon ni tambora)6. Mais dans les années 1920 le merengue cibaeño typique — considéré rustique et indigne des oreilles bourgeoises — a commencé à être timidement accepté dans les villes de la région de Cibao. L’anti-américanisme ambiant n’a pas empêché l’influence du gramophone et la diffusion du jazz enregistré de jouer un rôle influent. La pulsion afro-américaine du merengue contient des polyrythmies et tout en lui le rapproche du jazz. Après l’occupation états-unienne, le groupe de Luis Alberti jouait du jazz dans les salons chics et en 1933 il a commencé à fusionner jazz et merengue, allant jusqu’à incorporer accordéon, piano, güira et tambora dans sa formation. Cette importante innovation a réussi à faire revenir le merengue dans les salons après une très longue absence (il y avait été joué sous une autre forme au XIXe siècle). Dans les irrésistibles passages jaleo en fin de morceau les motifs de saxophone marqués par le jazz des orchestres américains se superposaient en remplacement de l’accordéon, notamment dans l’orchestre très populaire des frères Vásquez. Le merengue s’est cristallisé dans la forme qui aurait bientôt un succès international. À Santiago ce nouveau style est vite devenu populaire. Finalement les élites venues de Cibao, qui jusque-là méprisaient le merengue, ont adopté cette musique comme un symbole culturel national.

C’est aussi ce que fit Rafael Trujillo (1891-1961), qui prit le pouvoir en 1930 au profit d’un coup d’état militaire mené par Rafael Estrella Ureña. Estrella fut écarté par son rival lors des élections truquées qui suivirent le putsch. Trujillo a été au pouvoir pendant la quasi-totalité des enregistrements figurant sur cet album. Il joua un rôle très particulier dans le développement du merengue. Ce nouveau despote était un modeste petit bourgeois venu de San Cristóbal, une petite ville de province du sud. Il connut une enfance sans relief où il entendit du merengue paleo echao (le style du sud), du palos et de la mangulina dans les bals. Télégraphiste à seize ans, il est devenu membre d’un petit gang sans envergure puis a travaillé pour l’industrie du papier avant de devenir garde-champêtre. Il chercha à être admis par la haute société mais ses origines métissées partiellement haïtiennes, son instruction très limitée, sa façon de courir les filles et son appartenance à un gang lui ont fermé les portes des clubs de la bonne société à laquelle il vouera une rancune tenace. Il prendra sa revanche au-delà de ses espérances. En 1918 Trujillo s’engagea dans la garde nationale qui collaborait avec les forces d’occupation états-uniennes. Ses bons rapports avec les Américains lui permirent de gravir rapidement les échelons de l’armée. Il devint commandant de la région de Cibao où il découvrit le merengue cibaeño típico (le style du nord-ouest). Il dirigea des combats contre les résistants à l’occupation dans l’est et tout en conservant des liens étroits avec les États-Unis, il resta dans l’armée après le retrait américain. En 1928, neuf ans seulement après son engagement il fut nommé chef de l’armée. Il en fit aussitôt un instrument de pouvoir personnel. En ordonnant aux soldats de rester an caserne, Trujillo laissa les rebelles d’Estrella prendre la capitale en 1930 et devint co-président, chef de la police en plus de l’armée avant d’écarter Estrella de la présidence intérimaire quelques jours plus tard. Il était accompagné partout par un groupe cibaeño típico qui chantait ses louanges et décida aussitôt d’utiliser le merengue typique de Cibao comme un symbole d’unité nationale. Usant de violence, d’intimidation, de traîtrise et de grossière tricherie il gagna prétendument les élections avec 99 % des voix après une campagne ancrée dans la popularité du merengue. Plusieurs opposants avaient été jetés en prison avant même son élection. En un an, il serra tous les boulons d’une tyrannie absolutiste particulièrement abjecte, au culte de la personnalité aussi démesuré que grotesque. La moindre contrariété du Benefactor, qu’on devait appeler El Jefe, pouvait mener à un massacre. Tous les dirigeants régionaux ont été écartés ou réduits à néant, y compris Desiderio Arias, le populaire leader de Cibao qui fut exécuté. Les hommages à Arias, notamment l’interprétation d’un populaire merengue portant son nom, furent interdits. Trujillo ordonna que le merengue soit joué dans tous les bals de son territoire. Le merengue cibaeño típico n’avait jamais été entendu dans les bals de la capitale. L’interprétation de merengue, un symbole du peuple, choqua la haute société, mais nul n’osa critiquer les goûts du despote. La plupart des morceaux parlaient de danse, de séduction etc. Mais le dictateur narcissique suggéra aussi aux artistes de composer des morceaux à sa gloire et publiera lui-même à la fin de sa vie un recueil en quatre volumes de quatre cents d’entre eux. Des groupes jouant dans le style de Cibao ont commencé à sillonner le pays, évoquant souvent des sujets exaltant à la fois la paysannerie et le nationalisme comme El Negrito del Batey ou Caña Brava sur la culture de la canne à sucre, une industrie majeure dans l’île. Les bourgeois et la clique de Trujillo ont également découvert le merengue dans les bordels des bas quartiers, où était joué un répertoire salace bien spécifique. Bien que le merengue fusse à l’évidence une musique créole très ancrée dans ses influences africaines, selon la position officielle il était une musique créée par la « race blanche », dérivée directement de la culture espagnole et « malheureusement contaminée par la musique de sauvages nègres »7. Rien d’étonnant venant d’un populiste illuminé ami de dictateurs comme Franco en Espagne ou Somoza au Nicaragua. Pour Trujillo, le merengue devait bien entendu valoriser les valeurs blanches, espagnoles et catholiques — d’ailleurs l’Espagne le soutenait autant que l’église. Le slogan « Dieu au ciel, Trujillo sur terre » devait obligatoirement figurer sur les églises. Néanmoins en réalité les masses de la « république » dominicaine avaient un mode de vie caractéristiquement caribéen, proche de celui des créoles afro-américains de toutes les Caraïbes — incluant les stéréotypes de l’exploitation, de la misère et de l’acculturation issus de l’esclavage. Sans oublier que, comme à Haïti, le vaudou d’origine ouest-africaine est toujours resté très présent dans la culture locale. Tout en préservant une façade de bon chrétien Trujillo avait lui-même placé sa foi dans cette religion populaire, un culte animiste syncrétique appelé lua ou vaudou dans l’île. Il fréquentait ce milieu avec assiduité et utilisa les envoûtements et la divination — alors qu’il avait fait interdire ces pratiques dans tout le pays. Version merengue d’une salve, un autre style musical local, La Salve de las Antillas fait ici brièvement allusion à la santería dérivée des orishas yorubas8.

Grands Orchestres

En 1936 Trujillo fit renommer la capitale du pays à son nom. Il convoqua aussi Luis Alberti, un des meilleurs artistes du pays. Il le désigna comme son musicien personnel et le laissa enregistrer vingt titres à bord d’un bateau. Le tyran renomma son groupe de danse Orquesta Presidente Trujillo avant de l’introduire dans les bals officiels (écouter ici Seguiré a Caballo, enregistré des années plus tard par cet orchestre). En 1937 le dictateur xénophobe et raciste, qui exécrait les Haïtiens (alors que sa grand-mère était d’origine haïtienne) fit massacrer froidement entre dix et vingt mille paysans. Pour la plupart des Dominicains frontaliers, ils étaient soupçonnés d’être des immigrés haïtiens illégitimes et voleurs de vaches. Les personnes assassinées par l’armée étaient sélectionnées en fonction de leur accent : les Haïtiens prononcent mal le « r » du mot perejil (persil) et les candidats à l’exécution étaient sélectionnés ainsi. Jusqu’à son assassinat en mai 1961, l’autocratie de Trujillo a été sans limite. Le point culminant du pays a été rebaptisé Trujillo, les plaques d’immatriculation d’automobiles portaient le slogan Viva Trujillo ! et des statues à son effigie ont été produites en masse. Parmi les merengues qui lui ont été dédiés, citons Seguiré al Caballo (« je suis — du verbe suivre — à cheval »), qui fait allusion à son régime. San Cristóbal, du nom de sa ville de naissance, est un classique du genre, ici repris par l’orchestre d’Antonio Morel. Le tyran rebaptisera lui-même la région qui entoure San Cristóbal du doux nom de Trujillo.

Mais c’est surtout en raison de leur qualité que ces morceaux remarquablement bien écrits et arrangés étaient joués dans tous les bals. Tout en assurant la propagande nationaliste, la puissance de la musique séduisait le peuple. Beaucoup de Dominicains n’étaient pas dupes et jouaient le jeu : le généralissime apparaissait toujours couvert de médailles et le peuple l’appelait « Chapitas » (« capsules de bouteille ») pour cette raison. Contrairement aux oligarques de la haute société, Trujillo était un bon danseur. À sa grande satisfaction, l’élite du pays le détestait plus encore parce qu’il pouvait séduire une partie du peuple par la danse, une étincelle d’élégance, un panache dont les privilégiés de la haute société étaient incapables. Très machiste, la culture dominicaine considérait qu’une femme ne pouvait sortir seule danser le merengue. Connu pour sa grande consommation de femmes cédant sous la contrainte et la menace, le dictateur ouvrait les bals seul avec l’infortunée cavalière qu’il avait choisie, dénichée par une équipe payée pour lui fournir de jeunes femmes. Sa pratique de la danse faisait parler de lui et ces potins détournaient l’attention de ses actes moins heureux. Son goût pour le merengue faisait oublier à une partie du peuple la brutalité de son régime : la musique était devenue une sorte de soupape, de couverture, de façade.

Toute sa famille exploitait néanmoins le pays de ce champion du népotisme. À terme elle avait pris possession de 75 % des industries du pays, ce qui fit du généralissime un milliardaire. Bientôt, lancé par un frère de Trujillo et inspiré par les innovations de Luis Alberti, le Super Orquesta San José de Papa Molina avec le remarquable Tavito Vásquez au sax s’est imposé avec des classiques comme El Compay (interprété ici en version instrumentale par Antonio Morel). Leur chanteur Joseíto Mateo était présenté comme le « roi du merengue ». Ils avaient adopté un style nouveau, sans accordéon, utilisant un tempo plus rapide, des congas à la cubaine et une basse jouée en syncope, à contretemps. On peut écouter ce type de rythmique progressive dont Luis Kalaff fut le pionnier sur Severa, Gratey, La Pesadilla, Pan Caliente, Que Paqueton et Compay Cucu. Cette rythmique suggérait déjà la salsa. Une variante du merengue a aussi été enregistrée à Porto Rico sous l’étiquette locale bomba, notamment par Rafael Cortijo9 (« Cortaron a Elena » vers 1956). Un autre groupe dominant était celui d’Antonio Morel, représenté ici par de nombreux titres chantés par différents interprètes — dont Joseíto Mateo, ici sur Fiesta en la Joya — et plusieurs instrumentaux. Morel était une vedette un peu indépendante du pouvoir, à la fois engagée par la haute société, les bals populaires — et autorisée à enregistrer librement. Il alliait également le merengue à la sophistication des arrangements selon l’esthétique « swing » avec cuivres et saxophones. Sa version instrumentale de Los Saxofones incluse ici est caractéristique de ses arrangements sophistiqués. Morel y va directement au passage jaleo, normalement situé en troisième partie des morceaux, une pratique qui s’est répandue au fil des années 195010. Son orquesta représente aussi une tendance grand orchestre ancrée à la fois dans la très riche musique cubaine (rumba, son, mambo, etc.)11 qui faisait fureur à l’époque et les big bands américains des années 1920-1940. La richesse des arrangements de ces grands orchestres était prestigieuse. Le tyran et son frère José « Petán » Arismendy, un fêtard qui avait le contrôle des orchestres de merengue de tout le pays, soutenaient ces formations savantes qui jouaient dans leurs salons et palais. Comme son frère, Petán demandait souvent que la première danse soit réservée à son couple et les musiciens jouaient en cercle autour d’eux — en n’en pensant pas moins.

Malheureusement, à quelques exceptions près Petán s’est avéré incapable de produire des disques. Cette phase essentielle des musiques caribéennes n’a donc pas été enregistrée comme elle aurait dû l’être et les orchestres de merengue basés à l’étranger, bien mieux diffusés, ont pris d’autant plus d’importance. Les classes sociales étaient reflétées par leurs styles de merengue : les pauvres dansaient au son de l’accordéon des orchestres cibaeño típico (parfois augmentés d’un saxophone) et les riches des villes au son de grands orchestres rutilants capables de jouer dans les salons officiels. Les deux styles étaient joués en direct à la Voz Dominicana, une station de radio (et de télévision dès 1952) très populaire, fondée en 1942. La radio permettait aussi aux Dominicains d’écouter d’autres musiques latines venues de Colombie, Cuba, Porto Rico, des États-Unis et du Mexique. La location de matériel d’enregistrement ne fut disponible qu’à partir de 1950, ce qui permit notamment à Antonio Morel de graver quelques disques. Mais la peur et le monopole de Petán étaient tels que personne n’osait trop innover. Et nul n’osait vraiment concurrencer le frère du despote dans ce qui était pour lui un passe-temps. Petán s’intéressait aux bals où il pouvait briller et non à la production en studio ; Ce n’est qu’au hasard de ses caprices que des disques étaient enregistrés à Saint-Domingue et pressés aux États-Unis. Les grands orchestres sont principalement réunis sur le disque 3 de ce coffret.

Merengue International

Dès 1936, des musiciens avaient commencé à fuir le pays malgré les difficultés administratives, financières et l’interdiction de quitter le territoire. Billo Frómeta fut le premier à trouver le succès au Venezuela avec Billo’s Caracas Boys (avec Damíron au piano). Le chanteur de boléro Alberto Beltrán a rejoint un temps la Sonora Matancera à New York, avec qui il chantait aussi du merengue. Il fit connaître El Negrito del Batey et Compadre Pedro Juan aux États-Unis. Mais le premier à obtenir un grand succès à New York fut Angel Viloria. Cet accordéoniste jouait le merengue en petite formation dans le style cibaeño típico auquel il ajouta l’excellent saxophoniste Ramón E. García qui s’inspirait des innovations venues du jazz via Luis Alberti, Ramon António Molina y Pacheco dit Papa Molina (Super Orquesta San José) et Antonio Morel. Formé en 1950, après une série de 78 tours son groupe fut le premier à sortir un album microsillon chez Ansonia avec l’essentiel 25cm ALP-1 intégralement inclus ici. Spécialisés dans les musiques latines, les disques Ansonia avaient été fondés en juin 1949 par Rafael Pérez Dávila (né à Yauco, Porto Rico) et ont immédiatement trouvé le succès avec Viloria et son chanteur, Dioris Valladares.

Né le 14 août 1916, Dioris Valladares fut l’un des premiers Dominicains à s’exiler à New York dès 1936. Chanteur, percussionniste (güira), guitariste, il commença à se produire dans des groupes de rumba en 1939 avant de servir dans l’armée américaine pendant la Deuxième Guerre Mondiale. Il chantera avec de nombreux orchestres, dont ceux de Xavier Cugat, Noro Morales, Anselmo Sacasas, José Curbelo, Enrico Madriguera et celui du trompettiste Roger King Mozian, compositeur du standard de Machito « Asia Minor ». En 1950 Valladares rejoint le groupe du guitariste Porto Ricain Juanito Sanabria, qui jouait régulièrement au club Havana Madrid sur Broadway ainsi qu’au El Chico et au La Conga. Engagé au bal annuel du Daily News au club Caborrojeña dans le quartier de Spanish Harlem à New York, le groupe interpréta trois merengues qui eurent un grand succès, nécessitant plusieurs rappels. Le Caborrojeña devint le rendez-vous des Dominicains de New York. De nombreux Porto Ricains le fréquentaient aussi, et préféraient les merengues lents pour séduire. En revanche, les Dominicains appréciaient les tempos rapides où ils pouvaient faire valoir leur jeu de jambes. Chez les disques Ansonia fondés quelques semaines plus tôt, Rafel Pérez venait d’échouer avec une première série d’enregistrements latins. Dès qu’il eut vent de son succès il engagea l’orchestre de Juanito Sanabria. Les seizes faces de 78 tours qu’il a produit en 1950 se sont bien vendues mais la formation de Sanabria ne comprenait pas d’accordéon « typique ». Dominée par le piano et les instruments à vent, elle ne correspondait sans doute pas suffisamment aux canons du merengue rural et Pérez organisa une nouvelle séance, cette fois avec le Conjunto Cibañeo Típico de Viloria. Avec les enregistrements de l’excellent Tavito Vásquez (l’écouter sur Compadre San Juan de Ñiñi Vásquez) et quelques autres grands saxophonistes représentés ici, ces morceaux contribuent à inscrire le merengue et ses meilleurs saxophonistes dans l’arbre généalogique du jazz. On peut aussi y écouter l’excellent percussionniste dominicain Luis Quintero au tambora. Avec Vallardes au chant leurs premiers 78 tours eurent un large succès à New York, puis dans les communautés hispanophones des États-Unis et d’Amérique Centrale, aux Caraïbes et jusqu’en Amérique du Sud. En 1953 Luis Quintero et Dioris Valladares ont quitté Angel Viloria après une série de disques (réédités en albums microsillon 25 cm) qui avaient largement ouvert le marché du merengue. À leur tour Valladares et Quintero ont réussi avec leurs propres albums chez Ansonia, également représentés ici. Le chanteur Tetiton Guzmán enregistra aussi, sans doute avec Angel Viloria qui décéda peu après en 1954. Devenu le « roi du merengue » de la diaspora dominicaine, en 1961 Valladares a rejoint les disques Alegre et obtint un gros succès avec la pachanga ‘’Vete Pa’l Colegio’’. Il a continué sa carrière de chanteur latino à succès jusqu’en 1977, où il se fit plus discret. Dans les années 1970-90 avec l’émigration d’un grand nombre de Dominicains aux États-Unis le merengue se diffusera massivement sur les deux continents américains. De plus en plus apprécié, il disputera même parfois la place à la salsa sur les pistes de danse latines.

Influence du merengue

Quand Marilou danse reggae

Elle et moi plaisirs conjugués

En Marilou moi seringuer

Faire mousser en meringué

— Serge Gainsbourg, Marilou reggae

Étant donné la rareté des enregistrements insulaires et des disques dominicains, dans les années 1950 les artistes de merengue les plus connus internationalement étaient des exilés. Les musiciens dominicains étaient encore rares aux États-Unis et ils jouaient principalement pour la diaspora portoricaine de New York. Le succès des premiers disques de merengue enregistrés à New York au début des années 1950 — ceux de Dioris Valladares en particulier — ont incité des étrangers à adopter ce style très dansant. Appelé meringue à Haïti au milieu du XIXe siècle, c’est en 1955 que l’impact du merengue dominicain inspira au saxophoniste Nemours Jean-Baptiste une variante haïtienne initialement nommée le compas direct (konpa dirék ou kompa en créole), appelé « compas » en français et en anglais12. Chantés en créole haïtien, ses premiers enregistrements incluait du merengue. Ti Yaya Toto montre ici que d’un côté à l’autre de l’île, le merengue populaire était du même tonneau. Le compas était dérivé du merengue et s’est imposé à Haïti. À partir de 1956 il devint à son tour influent et important, notamment en Dominique, Martinique et en Guadeloupe où Kassav a partiellement basé son répertoire sur le compas avant de créer le zouk, qui en fut dérivé à la fin des années 1970. Le merengue a marqué toute l’Amérique du Sud et les Caraïbes, jusqu’en Jamaïque où les brillants saxophones altos du merengue ont marqué Sugar Belly, qui dans les années 1950 enregistra du mento avec un « bamboo sax » artisanal de son invention, puis du reggae13.

Valladares et Angel Viloria sont vite devenus des vedettes à Cuba, où le régime dictatorial de Batista était comme celui de Trujillo soutenu par les États-Unis. Le président américain Eisenhower était un militaire très conservateur qui préférait la stabilité de Trujillo au chaos qui l’avait précédé et ce ne sera que sous la présidence de gauche de Kennedy que les États-Unis prendront leurs distances avec l’affreux despote (la CIA participera discrètement à son assassinat le 16 août 1961). Comme Cuba, Saint-Domingue était une destination de vacances pour les Américains et à New York comme ailleurs, c’est dans un contexte de mode pro-cubaine que l’impact du merengue a été important pendant la décennie d’après-guerre. Après la vogue de la rumba (commencée dès les années 1920), l’impact des fantastiques musiques afro-cubaines modernes post-rumba avait commencé. Sous l’influence de Perez Parado et Beny Moré, la vague du rythme mambo déferlait. Cuba marquait déjà fortement la musique des États-Unis depuis 1947. Louis Jordan, Nat « King » Cole, Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, James Moody, Babs Gonzales, Ahmad Jamal, Billy Taylor, Lester Young, Sonny Rollins, Duke Ellington, Art Blakey, Erroll Garner, Slim Gaillard enregistrèrent tous sur des rythmes mambo cubains (notamment) — sans oublier Django Reinhardt et les artistes de rhythm and blues Dave Bartholomew, Chuck Berry14, Ruth Brown, Mickey Baker et tant d’autres qui affichaient leur ouverture aux sons latins. Mais contrairement au raz-de-marée du mambo et de son dérivé le cha cha chá qui touchaient le grand public américain grâce à des formations stables, installées avec le soutien de grosses marques de disques, le merengue était plus marginal, plus radical. Il séduisait surtout les latinos eux-mêmes.

La puissante incitation à la danse qu’il déclenchait a vite trouvé sa place dans les carnavals cubains — le summum de la reconnaissance pour une musique afro-latine. En version locale il était de plus en plus distinct de la grande aventure américaine et internationale. Pourtant, bien qu’enregistré à l’étranger par des exilés ou des musiciens d’autres nationalités, le merengue est resté un symbole culturel dominicain. À l’issue de la chasse aux sorcières anticommuniste menée aux États-Unis par le sénateur Joseph McCarthy, Trujillo a organisé en 1955 la « Fête de la paix et de la fraternité du monde libre » (!) — sous-entendu : le monde anticommuniste de l’après Staline — qui réussit à récupérer politiquement le succès international du merengue. À ces fins il commanda notamment un album de merengue à l’orchestre luxueux de Xavier Cugat, une grande vedette cubaine dont les engagements prestigieux étaient partagés entre New York et Los Angeles. Cugat y invitait le public à se rendre à la « Fête du monde libre ». Comme Xavier Cugat, le groupe phare cubain La Sonora Matancera enregistra plusieurs merengues. Chanteuse vedette de la Sonora Matancera, la grande Celia Cruz était une artiste de son cubain ouverte à diverses influences. Comme plusieurs artistes dominicains, elle publiait en outre des disques chez Seeco. Cruz s’installa à New York après la révolution de Fidel Castro en 1959. Nombre d’autres musiciens hispanophones ont inclus du merengue dans leur répertoire.

À Porto Rico, les vedettes locales Ismael Rivera, Rafael Cortijo et plusieurs autres ont enregistré dans les styles locaux très proches du merengue, la bomba et la plena (musique traditionnelle issue de la contradanza), qui étaient parfois vendus sous l’étiquette merengue en Europe en raison de leur similitude. L’influence du merengue se propagea aussi aux Bahamas (écouter ici le morceau d’André Toussaint avec son splendide solo de guitare)15. Il perça aux Îles Vierges voisines de Porto Rico (tous deux des territoires américains des Caraïbes) où les La Motta Brothers Virgin Isles Hotel Orchestra menés par leur pianiste Bill La Motta participèrent à faire connaître ce style avec leurs disques et leur spectacle à l’hôtel Virgin Isle (deux titres inclus ici). En 1959 le vétéran des séances de studio new-yorkaises Bill LaMotta enregistra son premier album solo à Porto Rico16. Deux de ses morceaux sont inclus ici. Comme Damíron, il proposait une version jazzy du merengue où les improvisations au clavier remplacent les instruments à vent. Les frères La Motta participèrent à l’enregistrement de l’album Calypso from the Virgin Islands sorti chez RCA, qui crédite le Trinidadien The Mighty Zebra au chant. Mais les deux merengues qu’il contient ne sont pas interprétés par ce dernier et El Compas del merengue et La Empaliza sont inclus dans ce florilège. Par ailleurs, l’excellent accordéoniste et compositeur Luis Kalaff émigra à Porto Rico puis à New York, où il enregistra plusieurs albums pour Seeco dont quelques-uns des meilleurs extraits sont inclus ici. Accompagné par le pianiste Francisco Alberto Simón Damirón, le chanteur José Ernesto « Negrito » Chapuseaux obtiendra de grand succès à New York jusque dans les années 1960 avec une version jazzy, quelque peu américanisée du merengue. Sur le chef-d’œuvre dansant El Marinero ils chantent un marin ambitieux parti à la conquête de l’Amérique et du monde.

À la fin des années 1950, les meilleurs musiciens de merengue étaient capables d’expérimenter de nouvelles rythmiques originales. La basse syncopée et l’ambiance suggéraient déjà la salsa (et ce plus encore que la plena portoricaine). Ce style de merengue original avec sa basse à contretemps, que Luis Kalaff fut un des premiers à populariser après son séjour portoricain est entendu ici sur La Pesadilla, Severa, Gratey, Compay Cucu, Que Paqueton, Severa (avec un solo de tambora de Luis Quintero), Pan Caliente, Madora Che Che, Pan Caliente, Las Dos Merengues. Après avoir été elle aussi longtemps rejetée par la haute société, la bachata, une forme dominicaine du boléro proche du merengue proprement dit, sera enregistrée à partir de 1961 par José Manuel Calderon. Plus ancrée dans le langage des rues et l’ironie contestataire, dans les années 1970 elle deviendra très populaire à Saint-Domingue et au-delà. La guitare caractéristique de la bachata originelle est déjà suggérée ici dans les merengues Pa’ Despues Venir Llorando, La Salve de las Antillas, Rio Abojo Voy et La Mecha de Luis Kalaff. Elles font parfois penser aux guitares tournantes de la rumba congolaise de Franco et l’O.K. Jazz, Docteur Nico ou Tabu Ley Rochereau dans les années 1960 — et aux succès de Manu Chao dans les années 199017.

Une fois mélangé au son montuno cubain le carabinier/merengue sera également à la racine de la pachanga cubaine (à la mode avec sa danse dérivée du guaracha cubain à partir de 1960) et de la salsa, une musique et danse latino américaine développée à New York dans les années 1970. Certains enregistrements de salsa rappellent ce style globalement dérivé du carabinier (carabiné en espagnol). C’est à Cuba qu’Eduardo Davidson a créé en 1959 la pachanga, un style proche du rythme merengue. Née à la fin des années 1960, la salsa descend directement de la pachanga et donc du merengue. Le musicien Johnny Pacheco, popularisateur de la pachanga et fondateur des célèbres disques Fania, marque emblématique de la salsa, est d’ailleurs né en République Dominicaine, où il a grandi.

À la mort de Rafael Trujillo, la liesse populaire rejeta illico les morceaux composés en son honneur, interdits en 1962. Tout ce qui portait son nom reprit son appellation d’origine et, soulagés, la plupart des artistes qui chantaient ses louanges retournèrent leur veste. De nouveaux morceaux condamnant le despote surgirent, parfois écrits par les mêmes. Cette période coïncide avec l’arrivée de la bachata et ses guitares, un nouveau style qui contribua à tourner une page maculée de sang. Le merengue est revenu à la mode une décennie plus tard.

Bruno Blum

Merci à Paul Austerlitz, Franck Jacques (Crocodisc), Youri Lenquette, Philippe Lesage, Dominique Rousseau (Exodisc), Louis Carl Saint Jean, Superfly Records et Fabrice Uriac.

© FRÉMEAUX & ASSOCIÉS 2014

1. Lire le livret et écouter Virgin Islands - Quelbe & Calypso 1956-1960 (FA 5403) dans cette collection.

2. Lire les livrets et écouter Harry Belafonte 1954-1957 (FA 5234) et le volume Calypso du coffret Anthologie des musiques de danse du monde (FA 5342) qui retracent le succès international du calypso dans cette collection.

3. Lire les livrets et écouter Elvis Presley face à l’histoire de la musique américaine 1954-1956 (FA 5361) et 1956-1960 (FA 5383).

4. Paul Austerlitz, Merengue, Dominican Music and Dominican Identity, Temple University Press, Philadelphia, 1997.

5. Lire le livret et écouter Slavery in America - Redemption Songs 1914-1972 (à paraître dans cette collection).

6. Lire le livret et écouter Cuba - Bal à La Havane 1926-1937 (FA 5134) et Cuba - 1923-1995 (FA 157) dans cette collection.

7. Paul Austeritz, ibid. p. 62, citant Floridá de Nolasco, un folkloriste en accord avec le régime.

8. Lire les livrets (disponibles en ligne sur fremeaux.com) et écouter Voodoo in America 1920-1961 (FA 5375), Jamaica - Folk, Trance, Possession 1939-1961 - Roots of Rastafari (FA 5384), Slavery in America - Redemption Songs 1914-1972 à paraître, Africa in America 1920-1962 (FA 5397) et Virgin Islands - Quelbe & Calypso 1956-1960 (FA 5403) dans cette collection. Ces coffrets évoquent tous les cultes animistes afro-caribéens.

9. Écouter El Bombón de Elena de Cortijo y su Combo sur l’anthologie Great Black Music Roots 1927-1962 (FA 5456) dans cette collection.

10. Lire l’analyse musicologique de « Los Saxofones » par Paul Austerlitz, ibid. p. 58.

11. Lire le livret et écouter Cuba - Bal à La Havane 1926-1937 (FA 5134) dans cette collection.

12. Écouter le compas Contredanse #8 de Nemours Jean-Baptiste sur l’anthologie Great Black Music Roots 1927-1962 (FA 5456) dans cette collection.

13. Lire le livret et écouter Sugar Belly sur Jamaica - Mento 1951-1958 (FA 5275) et l’album de reggae Sugar Merengue (Studio One, 1973).

14. Lire le livret et écouter The Indispensable Chuck Berry 1954-1961 (FA 5409) dans cette collection.

15. Retrouvez André Toussaint sur Bahamas - Goombay 1951-1959 (FA 5302) dans cette collection.

16. Retrouvez Bill La Motta et les La Motta Brothers sur Virgin Islands - Quelbe & Calypso 1956-1960 (FA 5403) dans cette collection.

17. Retrouvez Franco et le Tout Puissant OK Jazz et Tabu Ley Rochereau sur l’anthologie Great Black Music Roots 1927-1962 (FA 5456) dans cette collection.

Dominican Republic - Merengue

Haiti - Cuba - Virgin Islands - Bahamas - New York 1949-1962

By Bruno Blum

Merengue has an atypical history in that it was almost impossible for Dominican musicians to record their music in their own Republic. Despite the popularity of the genre, recording equipment was quite scarce; and the autocratic tyranny of Rafael Trujillo, who was in power from 1930 to 1961, moved many musicians into exile. This small Dominican scattering found refuge principally in New York where, from 1949 on, musicians would have access to record-production of quality, notably with such N.Y. labels as Ansonia (founded by Rafael Pérez Dávila in 1949) or Seeco (founded by Sidney Siegel in 1943). And so, with the success of records by bands like that of Angel Viloria with singer Dioris Valladares, merengue was able to spread across the Latin Caribbean from the Fifties onwards. Like the Virgin Islands1, Puerto Rico was a U.S. territory, and Dominican musicians were especially appreciated by their Puerto Rican neighbours, of whom there were many in New York. Cuban and Puerto Rican orchestras playing son, mambo, cha-cha-cha and other fashionable Latin styles of the Fifties — cf. Xavier Cugat, Celia Cruz — made merengue records and added their own colours. Latin music still continued to prosper after the advent of calypso2 and rock ‘n’ roll3 in 1956. Dancers found merengue irresistible, and the influential authentic variety heard here formed one of the main roots of kompa from Haiti and also salsa, the genre which developed later amidst the Latin community in New York (and Puerto Ricans in particular). The little-known merengue genre, despite its success since the Seventies, is the heir to a tradition that dates from the 17th century and this anthology represents its true Golden Age, the 1950s.

Country dances in Santo Domingo

Located to the southeast of the Florida shore, the Dominican Republic is the Caribbean’s largest territory after neighbouring Cuba. The island was named Hispaniola by Christopher Columbus in 1492, and the French, who disputed the Spanish claim, called it Saint-Domingue. The island’s Arawak-speaking Taino natives were exterminated by Spanish colonization and epidemics carried there from Europe, but cross-breeding was widespread and a number of Dominicans have Amerindian ancestors. From the 16th century onwards, Africans reduced to slavery were deported en masse, creating a new population-category of zambos (mixed-blood Taino-Africans). The city of Santo Domingo rapidly developed as the first major colony of the New World, and by the 16th century its colonial district possessed the first Christian cathedral of the Americas. It also became the first military base for the Spanish conquests of the Caribbean, Central and South America.

According to saxophonist, ethnomusicologist and merengue history authority Paul Austerlitz4, “country dances” were fashionable with the English gentry and adapted to the salons of aristocrats at the court of Charles II. King Louis XIV of France was very fond of new dances and in the mid-18th century he adopted them under the name of “contredanses” — a simple phonetic version of “country dances” — at his own court at the Château of Saint-Germain-en-Laye. Their novel particularity was that couples danced them freely, in contrast with the usual practice of group dances. In 1697, Spain granted the western part of Hispaniola to France by treaty. The French “contredanse” variant was then introduced into the colonial salons of Port-au-Prince. Like other music-styles of European origin, at the request of their masters it was also played by enslaved musicians. It was quickly adopted by Dominicans of African origin to whom music represented a kind of freedom5. They created a popular African American version of it, notably the “carabinier” dance and rhythm at the root of the meringue (“mereng” in English) found in the western part of the island, which would later become Haiti. And so as early as the 17th century, the Santo Domingan French colony probably provided the context for Afro-American dances which foreshadowed the extremely free pair-dances of the 20th century.

Too busy with its invasion of South America, Spain granted the eastern part of the island to France in 1795. Meanwhile, in the élan of the 1789 French revolution, the western side of the island obtained its independence after a long and bloody slave-rebellion led by Toussaint-L’Ouverture. Independent since 1804, that territory became the Haitian Republic. Founded by former slaves, Haiti was the first Caribbean republic, the world’s first black republic, and America’s second democracy. The consequence was that the island was divided into two separate countries; after Haitian independence, the east of the island and its capital — “Saint-Domingue” — remained French.

Merengue, carabinier and danza

The turmoil of the Haitian revolution caused a number of the French to flee, and many took their slaves with them to Spanish territories in the Caribbean (Cuba, Puerto Rico) where their “country dances” instantly spread — unless it was the other way around, as the influence of the contradanza might well have come to Haiti all the way from the Spanish Antilles. The Spanish term “merengue”, in any case, has its etymology in the “meringue”, the baked French confection (maybe because well-beaten egg-whites can require frenzied body-movements.) As for the sugar in the meringue recipe, that ingredient came from the Antilles. The “contredanse” (“contradanza” in Spanish) and its Haitian derivative the carabinier are probably at the roots of the rhythms and styles close to merengue which developed in the Caribbean region (notably the danza in Puerto Rico and Cuba) and finally gave birth to several major styles referred to in the paragraph at the end of this booklet devoted to merengue influences. Those styles crystallized later on Santo Domingo in the 19th century as “merengue”, a popular and rural style which contrasted with the “contredanses” of the salons. Over the years, Haitians attempted to spread their revolution eastwards; wars and repeated massacres installed a climate of fierce hatred between the island’s two halves, ruled by Blacks in the west and Whites in the east. Finally, with the support of Haiti and Great Britain, the Spanish regained control of the eastern part of Santo Domingo in 1821. So the original rhythms of merengue were performed well before the Dominican Republic gained independence in 1844. Distinct from the classic 2/4 merengue rhythm used on most titles in this set, the carabinier style would remain an integral part of merengue as a whole and its melodic and rhythmical influences are featured in this anthology. Tu Ti Sabes Como Fue here is an incarnation of it in the merengue style.

In neighbouring Puerto Rico, a variant of the Cuban danza called upa was brought in by Cuban regiments in 1842/43. Criticized as too lascivious, the “upa” (danced freely by couples) was banned in 1849; fines were imposed on those who allowed it, and upa dancers were imprisoned… It disappeared in the 1870s. According to a long tradition in slavery which considered Afro-American music and dancing to be vulgar, debauched and incompatible with religion, in Cuba the danza of Afro-Haitian origin was also censored. The same fate awaited merengue in Venezuela, where it was performed before disappearing before the end of the 19th century. But like the Haitian mereng, Cuba’s danza (and the danzón in which groups danced the paseo) became a symbol of Afro-Caribbean identity. The Dominican merengue didn’t escape this pan-Caribbean nationalistic symbolism: denounced by colonial societies for its sensuality and the fact that it was danced by couples, it was appreciated by the people for those very same reasons. When the Dominican Republic became independent in 1844, it was already inseparable from its national identity. Juan Bautista Alfonseca was probably the first merengue composer whose name was remembered; he belonged to the independence movement and composed in different styles including the mangulina (another local dance and music form). The mangulina (and not merengue) gave its rhythm to the country’s first national anthem, which Alfonseca composed in the local style whose standing he wanted to enhance.

Most written 19th century sources harshly criticize popular merengue. They denounce the dance, which sometimes included suggestive hip-movements considered unseemly and degrading. Indifferently referred to as danza or merengue, the music was seen as a contemptible African American form of expression in a country whose high society detested nearby Haiti’s negritude, admiring the cultures of France and Spain instead. And yet the population of Santo-Domingo descended from mixed blood: crossbreeding with origins that were African and indigenous in their majority. But the white society in power insisted on imposing a European identity on the nation, and merengue music was excluded from its salons. This paradox also shows the extent to which it was appreciated in popular rural dances. It was played with strings, including the violin, guitar, mandolin, the tiple or tiplet, the cuatro, a flute, and percussion that included a tambourine or pandereta. Present in Puerto Rican and Latin-Caribbean music in general, the merengue was played on the Caribbean güiro of African origin, a hollow gourd with notches in the side which later became a metal tube that symbolized merengue, rubbed with a gancho or pùa (scraper), three or four metal sticks planted on a base with a wooden handle (see Luis Kalaff’s group photo). Also present were the timbale and tambora, a drum specific to merengue that was played across one’s lap in the 19th century, and later hung around the neck on a strap and struck with a drumstick on one side, by the hand on the other (see Luis Quintero’s photo). After the “restoration war” which repelled a Spanish invasion in 1863-65, the clarinet and military baritone appeared in rural groups wanting to resemble the elegant ensembles in the city’s salons. These wind instruments also played a role in the Puerto Rican danza and Haitian merengue, which were similar. When circumstances allowed, a piano was also used. As everywhere in the Caribbean, from Louisiana to Venezuela, European music forms — here the contredanse — were transformed. First they crossed colonial urban centres, and then they spread to the countryside, where they were subjected to the creativity, diversity and influence of local artists. This was the case with the quadrille, polka, schottische, mazurka, bolero, waltz, hymns and other European music forms, which took root in the Americas. They supplied the soil from which sprang African American music styles like Negro spirituals, the calypso, merengue, son, and later jazz or gospel. Even in Europe the waltz was sometimes considered improper; it also enjoyed a Creole incarnation throughout the Caribbean. Its rhythm resembles a form of carabinier-merengue, and Tu Si Sabe Come Fue and Madora Che Che (Luis Kalaff) are eloquent examples of it as a form suited to the steps of the mangulina, the Dominican group-dance.

Merengue cibaeño

Quadrilles, danzas and meringue/merengue dances were played throughout the Dominican Republic. But it was more particularly in the densely-populated Cibao country region that a new sound came to be heard, an accordion with rhythm provided by the swinging güira and the tambora. The accordion spread progressively through the region beginning in 1870. German traders were buying rum and tobacco in Santo Domingo and also exported their accordions there. Considered a simple instrument (in that it produced only one major scale), it was highly criticized by those who preferred strings, which were considered more refined. Several songs have referred to this stylistic issue, but even if it couldn’t play some of the pieces that had previously been written in a minor key, the accordion established itself in the region of Cibao. Songs written for it allude to various events and they often deferred to the caudillos, the region’s rulers, whose glory they saluted.

The economic policies of the dictator Ulises Heureaux, who was in power from 1886 to 1899, ruined the country to the point where its European creditors sent warships to obtain payment. The United States saw these troop movements as a threat to their control of the highly strategic Panama Canal, then under construction, and in 1905 a treaty gave control over Dominican finances to the USA, who shared the country’s domestic product between foreign creditors and the population. This infringement of the country’s sovereignty created strong tensions and led to an American occupation from 1916 to 1924 (Haiti was occupied in the same period). The American military authorities were hated, and Dominican nationalism was exacerbated, taking various forms: not only guerrilla warfare against American marines in the east, but also an increased prestige given to the country’s own culture, notably the form of merengue that was typical of Cibao and its region — merengue cibaeño became one of that culture’s symbols. The regional capital Santiago de los Caballeros was emblematic of the development of this traditional folk merengue. Accordionists’ groups, among whose stars were Francisco “ñino” Lora and Antonio “Toño” Abreu, were those who gave shape to modern merengue: accordions with two rows of buttons (capable of producing minor scales), güira made of metal (the güiro being the calabash variant), and tambora played with the palm of the left hand in addition to a drumstick. From around 1910 onwards, an alto saxophone gradually replaced the rhythm role of the baritone. Under the influence of Avelino Vásquez and Pedro “Cacù” Lora, the saxophone merengue style began to develop. It would greatly contribute to the efficiency of this music, as you can hear from Ramon E. Gomez here in Angel Viloria’s orchestra towards 1950. But the saxophone was scarce in rural areas, and not considered típico. In Cibao, however, the urban merengue of Santiago (often with a saxophone) was just as authentic, and its rise was important in the success of this music genre. It was performed at various feasts — at cock fights, dances, major calendar-events, even in brothels — and played on dance-floors that were impeccable. Cibaeño dancers donned their finest clothes (and wore shoes!) even in the most rural areas. In town, every social class took part in the dances held at weekends (pasadías), so much so that merengue became a kind of social mortar that bound the regional population together. Dancing enabled seduction, with males carrying out dance steps that allowed them to shine. The lively tempo of merengue gradually accelerated in the Fifties and Sixties to reach supersonic speeds later, but at the beginning of the 20th century the tempo was rather slow.

It was made up of three parts: a short introduction forming an invitation to dancers in announcing the start of the dance (a good example is the paseo of the first ten seconds of Compadre San Juan), and then the “first part” merengue followed by the repetitive jaleo, where the saxophones played a special rhythmical role in the “call and response” principle characteristic of African American music. It was in this “second part” — where the soloists take flight — that the orchestra and dancers in their Sunday best were seized by frenzy. As elsewhere in the Caribbean, popular dances were genuine events, authentic shows that put the spotlight on participants. The best singers were capable of improvising lyrics that commented on current topics: on request, they could even think up songs that would encourage one person to marry another… Politicians were commonly criticized or congratulated. Desiderio Arias, a Cibao leader who was very popular before the American invasion in 1916, was often mentioned in such songs. In brothels, songs would have lyrics often describing women with little virtue. Even though merengue was still a vector of cultural resistance to the American occupation, during the 1920s American companies like Victor made the first merengue/danza recordings in New York. Americans were mocked and threatened in “La Protesta”, which was rarely played in their presence; the “pambiche” style (Palm Beach with a Spanish accent) was even inspired by the clumsy dancing of the American occupiers and their one-step and fox-trots etc... Gradually, Dominican folk music was listened to with a romantic ear, and on the departure of the Americans in 1924 the Dominican nationalist movement widely used the traditional melodies of Cibaeño merengue as a vehicle for patriotic ideology. New lyrics, nationalist or not, were adapted for popular tunes and given the status of national treasures. Luis Alberti, for example, signed the traditional melody of Compadre Pedro Juan (the version here is played by ñiñi Vasquez’ orchestra) after adapting it to a rhythm linked to the Latino-Caribbean tradition of the cinquillo rhythm. A strong Mexican influence also contributed to nourish Dominican song in the 20th century. Both the elite and the people displayed their nationalism, which undermined the morale of American occupiers. American music was boycotted. In similar fashion, popular voodoo culture had carried the Haitian revolution, and the danza of the people has been associated with the independence movements in Cuba and Puerto Rico.

Merengue, an official art

Merengue was given a leper’s welcome in salons where Cuban danzón was played for high society by orchestras featuring wind instruments (i.e. without an accordion or tambora)6. But in the 1920s the characteristic merengue cibaeño tipico — considered rustic and unfit for bourgeois ears — began to be timidly accepted in towns around Cibao. The reigning anti-Americanism didn’t prevent the influence of the gramophone and the spread of jazz from playing an influential role: the African American pulse of merengue had polyrhythm and everything about merengue brought it close to jazz. After the US occupation Luis Alberti and his group played jazz in chic salons and in 1933 he began a fusion of jazz and merengue, even going so far as to incorporate an accordion, piano, güira and tambora in his orchestra. That important innovation managed to bring merengue back into salons after a lengthy absence (it had been played there in another form in the 19th century). Marked by jazz and American orchestras, the saxophone riffs in the irresistible jaleo parts at the end of a piece were superimposed and replaced the accordion, notably in the extremely popular orchestra led by the Vásquez brothers. Thus merengue crystallized in the form which would soon enjoy international success. In Santiago the new style quickly became very popular and the elites from Cibao, who had scorned merengue until then, finally adopted the music as a national cultural symbol.