- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

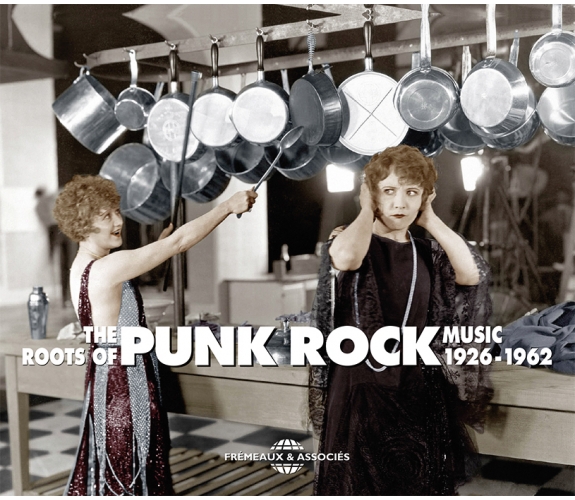

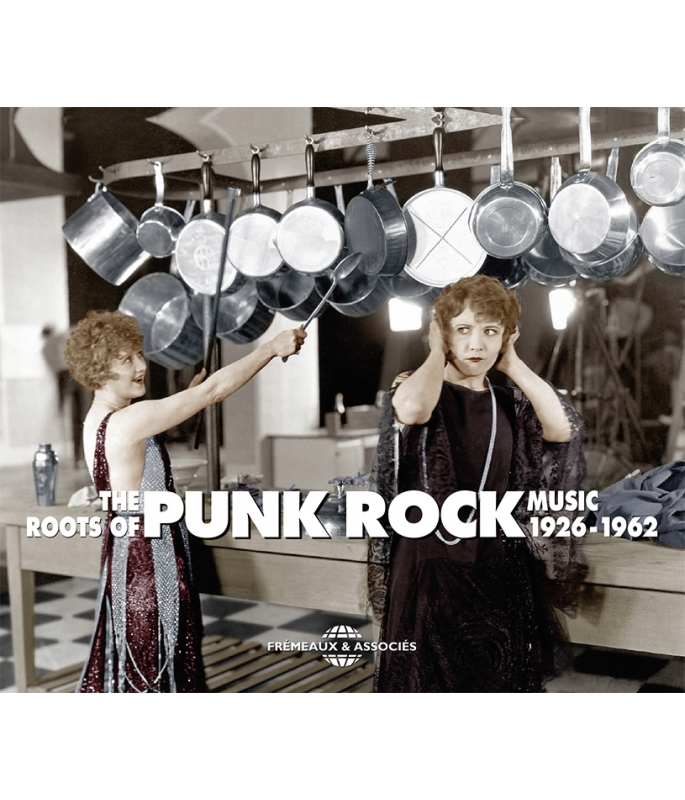

PUNK ROCK (THE ROOTS OF) 1926-1962

Ref.: FA5415

EAN : 3561302541525

Artistic Direction : BRUNO BLUM

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Total duration of the pack : 3 hours 3 minutes

Nbre. CD : 3

PUNK ROCK (THE ROOTS OF) 1926-1962

PUNK ROCK (THE ROOTS OF) 1926-1962

Bruno Blum, himself part of the Punk movement in London in the late Seventies, here returns to the original forms of subversion contained in Rock. As hedonists looking for ways to overtake their own selves as well as their social status, Artists — and particularly Musicians — seemed to be the only ones who could free themselves of society’s rigorous norms. From Charlie Parker to Bo Diddley via Artie Shaw or Richard Berry, the irreverence and arrogance later celebrated in the Punk Rock of Iggy Pop, The Clash or The Ramones has roots in the frenzied tempos of Bop and the contorted melodies of Free Jazz, with branches as far as the sexual allusions of the Blues and the wild solos of Rockabilly. Patrick FRÉMEAUX

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Petro RhythmVaudou congregation00:00:501960

-

2Black Bottom StompJelly Roll Morton00:03:121926

-

3Tiger RagArt Tatum00:01:591932

-

4Swing Is HereGene Krupa's Swing Band and Benny GoodmanRoy Eldridge00:02:571936

-

5Traffic JamArtie Shaw and his OrchestraRoy Eldridge00:02:171939

-

6B 19Slim and SlamRichard D. Squires00:03:061932

-

7KokoCharlie Parker's Be Bop BoysRichard D. Squires00:02:551932

-

8I Want My LovingArthur Big Boy Crudup00:02:591946

-

9Get The MopRed Allen00:02:481946

-

10Butcher PeteRoy BrownRoy Brown00:05:131949

-

11RebeccaBig Joe Turner00:02:431944

-

12Run Mister RabbitSmilin' Smokey LynnJackson00:02:121944

-

13I'M Going Myself A RoomTiny Bradshaw and his orchestraBradshaw00:02:451950

-

14Earl's BluesEarl Bostic00:02:351949

-

15Junco Partner Worthless ManJames Wee Willie Wayne00:02:291951

-

16She Sets My Soul On FireSonny Parker00:02:521951

-

17Hurry Hurry BabeRoy Brown00:02:351952

-

18The GoofBig Jay McNeelyRobert McNeely00:02:271952

-

19You Look BadDanny Taylor00:02:271953

-

20OverboardSugar Boy Crawford00:02:361953

-

21Mess AroundRay Charles00:02:441953

-

22She SaidHasil Adkins and his Happy Guitar00:02:481955

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Louie LouieRichard Berry and the Pharaohs00:02:141956

-

2MaybelleneChuck Berry00:02:251955

-

3Train Kept A Rollin'The Johnny Burnette Rock'n Roll TrioHoward Kay00:02:171956

-

4The Woo Woo TrainThe ValentinesGeorge Goldner00:03:021956

-

5Rubber BiscuitThe ChipsR. Levy Adam00:02:091956

-

6Every Time I Hear That Mellow SaxophoneRoy Montrell00:02:211956

-

7Stranded In The JungleThe CadetsJ. Johnson00:03:071956

-

8Hot Skillet MamaYochanan with Sun Ra and his ArkestraLe Sony'r Ra00:03:141957

-

9Rock This MorningLowell Fulson00:01:491957

-

10Red HotBob Luman00:02:041957

-

11Keep A Knockin'Little Richard00:02:191957

-

12High School ConfidentialJerry Lee Lewis00:02:331958

-

13C'Mon EverybodyEddie CochranJerry Capehart00:01:581958

-

14Red Hot Rockin' BluesJesse JamesLee Denson00:02:251958

-

15Little GirlJohn and Jackie00:02:141958

-

16Green MosquitoThe Tune RockersGene Strong00:02:201958

-

17Thumb ThumbFrankie LymonR. Hernandez00:02:181957

-

18Bad BoyLarry Williams00:02:191959

-

19Juvenile DelinquentRonnie Allen00:01:581958

-

20Strollin After DarkThe Shades00:02:101959

-

21Right TurnLink Wray and His WraymanM. Grant00:01:471959

-

22Excursion On A Wobbly RailThe Cecil Taylor Quartet00:09:051958

-

23Lonely WomanOrnette Coleman00:04:591959

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Love MeThe Phantom00:01:321958

-

2Ooh My SoulLittle Richard00:02:071957

-

3Rockin' The JointEsquerita00:02:021958

-

4Sunglasses After DarkDwight Pullen00:02:121958

-

5Rave OnBuddy Holly and the Crickets00:01:501958

-

6Do You Wanna DanceBobby Freeman00:02:371958

-

7Somethin' ElseEddie Cochran00:02:061959

-

8The Beat GenerationBob McFadden and Dor00:02:061959

-

9Run Diddley DaddyBo Diddley00:02:431959

-

10I Love You SoBo Diddley00:02:261959

-

11Brand New CadillacVince Taylor00:02:371959

-

12Rockin' In The GraveyardJackie Moningstar00:02:421959

-

13Swichblade SamJeff Daniels00:02:121959

-

14I Fought The LawThe Crickets00:02:141959

-

15California SunJoe Jones00:02:221961

-

16Pills Love's Labour LostBo Diddley00:02:511961

-

17DeniseRandy and The Rainbows00:01:581961

-

18Good Golly Miss MollyScreaming Lord Sutch00:02:391961

-

19Goo Goo MuckRonnie Cook and the Gaylads00:02:391962

-

20BossThe RumblersJonnhy Kirkland00:02:241962

-

21Papa Oom Mow MowThe RivingtonsCarl White00:02:281962

-

22Let's DanceChris Montez00:02:241962

-

23High School ConfidentialHasil Adkins00:02:431959

-

24No MoeAlbert Ayler00:07:061962

The Roots of punk FA5415

The roots of Punk Rock Music 1926-1962

par Bruno Blum

Je me promenais sur King’s Road avec une colère et un ressentiment total. Les gens étaient extrêmement absurdes et portaient encore des pattes d’ef, des platform boots et des brushings mi-longs en prétendant que ce qu’il se passait dans le monde n’existait pas vraiment.

— John Lydon dit Johnny Rotten, chanteur des Sex Pistols1

Cristallisé en 1977, le mouvement punk exprimait sans fard sa révolte et la réalité crue des tumultes de la jeunesse. Par leurs actes artistiques subversifs et leur engagement, les groupes punks ont contribué à faire progresser les mentalités de leur temps. Leur rock était une forme d’expression radicale issue d’un sentiment d’exclusion, d’injustice — et d’ennui.

Pas marrant d’être seul/Amoureux de personne d’autre/Peut être sortir peut-être rester à la maison/Peut-être appeler maman au téléphone

— The Stooges, No Fun, 1969

Comme le jazz « swing » des années 1930, le jazz moderne « bop » des années 1940, le free jazz des années 1950-60 et le rock des années 1950, le rock punk des années 1960 et 1970 a subi une diabolisation médiatique et un rejet des conservateurs.

— C’est quoi exactement, le rock punk ?

Joe Strummer [The Clash] : Je n’ai pas encore décidé ce que c’était ! [rires] Demande à quelqu’un d’autre ! Demande au policier le plus proche ! Il t’expliquera !

— Joe Strummer à l’auteur en avril 1978

Cet album réunit des musiciens des générations précédant les années 60-70, des précurseurs habités par les mêmes ressentiments et aspirations. Pour la plupart américains, ils inspirèrent la vague punk des années 1970 par leur style, leur esprit d’initiative, leur goût de la transgression, leur énergie juvénile et leur absence de complexes.

Rock and Roll Nigger

Punk (1) [pungk]. n. et adj. Une personne ou une chose sans valeur ; balivernes ; bêtise.

— Harrap’s Chambers Concise English Dictionnary, Londres, Chambers, 1993.

À la télé, quand tu regardes un policier comme Kojak, à la fin quand les flics attrapent le tueur en série, ils le traitent de «?sale punk?». Les profs t’appellent comme ça. Ça veut dire que tu es ce qu’il y a de pire. Alors tous les paumés et les ratés se sont regroupés et ont lancé un mouvement.

— Legs McNeil, rédacteur en chef du magazine new-yorkais Punk2

En toute logique, le punk rock plonge principalement ses racines dans les musiques de descendants d’esclaves ayant subi le mépris de la société blanche et l’inique exclusion de la ségrégation raciale. Tous vivaient une révolte intérieure et beaucoup d’entre eux affichaient une ostensible excentricité (comme ici Esquerita, Little Richard ou les Chips sur Rubber Biscuit).

Rejeté par la société/Traitée avec impunité/Protégé par ma dignité/Une quête de la réalité/New wave/Nouvelle vague/Nouveaux amis

— Bob Marley & Lee “Scratch” Perry, Punky Reggae Party, 1977

Les musiciens de rock attirés par la rébellion revendiquent souvent leur lien avec les afro-américains et reprennent leurs compositions. Patti Smith, figure centrale du mouvement punk et auteur de l’album Radio Ethiopia, raconte dans sa chanson « Rock and Roll Nigger » que le modèle absolu pour se retrouver « hors de la société » c’est le « négro » (sic). Pour elle, tous ceux qui se placent à l’extérieur de la société sont en fait assimilables à ses frères et sœurs les « négros ».

Jimi Hendrix était un négro/Jésus Christ et ma grand-mère aussi/Jackson Pollock était un négro/Un négro négro négro négro /Négro négro négro/

Si tu cherches en dehors de la société/C’est là que tu vas me trouver

— Patti Smith Group, Rock and Roll Nigger, 1978

Pour cette passionnée de rhythm and blues et de reggae, le terme péjoratif nigger (« négro ») était le symbole de l’exclusion. Dans les années 1940-1950 où, dans plusieurs états, le droit de vote et l’accès aux écoles pour les citoyens d’origine africaine n’étaient pas appliqués, le racisme était une violente réalité. À l’origine, le mot « punk » signifie « amadou », un extrait de champignon parasite de couleur noire, l’amadouvier.

« À la racine de ce mot anglais et de son synonyme «?spunk?», qui signifie aussi sperme, on trouve le gaëlique « spong » (amadou) dérivé du latin spongia (éponge). « Punk » a une autre signification dérivée du sens de cet agaric parasite et abondant : « mauvaise qualité », «sans valeur» et par extension « faible d’esprit ou de santé ». Ainsi, certains Américains blancs appellent parfois des « punks» les personnes de la même couleur que l’amadouvier, puisqu’ils les considèrent sans valeur3.»

Les artistes réunis ici étaient aussi possédés par la fièvre du désir (évoquée, entre autres, sur Hot Skillet Mama avec Sun Ra), une frustration propre à la jeunesse, subversive car évoquée sans retenue dans une Amérique pudibonde (Love Me). Leur quête identitaire générationnelle était tout aussi difficile à satisfaire dans un contexte très conservateur. Ils avaient en commun des esthétiques musicales diverses mais convergentes (paroles osées, humour aigre-doux, défiance, refus des conventions musicales établies, tempos très rapides, danses frénétiques et libres). Analogues par leur mal de vivre, leur hédonisme et leur soif de liberté, ils provenaient néanmoins d’horizons sociaux et musicaux très différents, du jazz dixieland de Jelly Roll Morton ou Henry «Red» Allen jusqu’au rockabilly adolescent le plus cru (Hasil Adkins, The Phantom, John & Jackie, Dwight Pullen). Mais rétrospectivement leur originalité, leur radicalité et leur célébration sincère, parfois candide de la marginalité les réunit au-delà d’une stricte forme musicale.

J’étais debout au coin d’une rue passante/Tout le monde me regardait/Je portais des lunettes de soleil la nuit/On a vraiment l’air classe avec des lunettes de soleil la nuit

— Dwight Pullen, Sunglasses After Dark, 1958.

À bien des égards, nombre d’écrivains, cinéastes et artistes radicaux ont participé au mouvement punk, qu’ils l’aient compris ou non, de Marcel Duchamp au mouvement dada, de Guy Debord à Hubert Selby, de la beat generation à Alejandro Jodorowsky, du courant expressionniste à Andy Warhol, du Professeur Choron à Coluche, de Jean Genet à William Burroughs et de Fritz Lang à David Lynch. À leur manière, ils en ont partagé l’esprit — et l’attitude incisive.

Je disais déjà « laissez-moi sortir » avant d’être né/C’est un tel pari que d’avoir un visage/C’est fascinant d’observer ce que fait le miroir/Mais quand je dîne je me mets devant un mur

— Richard Hell, The Blank Generation, 1977.

Vaudou

Le thème du vaudou est récurrent dans l’œuvre du grand groupe de punk rock/psychobilly post-kitsch The Cramps4, qui adaptèrent l’obscur instrumental Strolling in the Dark (très influencé par Link Wray) inclus ici pour en faire leur classique « I Was a Teenage Werewolf » proche de l’imagerie vaudou des comic books américains dans les années 1950. Les cimetières et autres « witch doctors » sont chantés ici par Jackie Morningstar sur Rockin’ in the Graveyard. Mais le vaudou n’est pas qu’un stéréotype satanique pour film de série B. Il est d’abord une grande religion originaire d’Afrique qui s’est mélangée à d’autres éléments africains et chrétiens dans toutes les Amériques, dont le territoire des États-Unis — aux Îles Vierges5 et en Louisiane notamment. Le vaudou fut ainsi l’une des grandes forces spirituelles qui façonnèrent la résistance à l’esclavage. À sa manière, le punk rock sera aussi une forme de résistance à l’oppression, à l’exploitation de l’homme par l’homme, au statu quo social : à quelques nuances près, il descend directement des intenses cérémonies afro-américaines des cultes des esprits, qui mêlées aux negro spirituals, sont aux véritables racines du rock6.

Le 15 août 1791, le prêtre vaudou Boukman donnait le signal de départ de la seule grande révolte d’esclaves victorieuse de l’histoire. Elle fut menée par Toussaint L’Ouverture, qui avec le vaudou unifia et galvanisa son peuple en lutte. En douze ans de révolution, le « Spartacus noir » triompha de la plantocratie française, de l’armée anglaise de George III, et accouchera de la première république noire de l’histoire : Haïti. Nombre d’esclaves furent déportés d’Haïti en Louisiane pendant cette période tumultueuse. À la Nouvelle-Orléans, notamment à l’occasion des musiques et danses afro-américaines de Congo Square7, ce sont leurs descendants imprégnés de vaudou qui poseront les bases des musiques de résistance afro-américaines modernes, dont l’existence même était un défi à l’autorité : negro spirituals8 des siècles de l’esclavage9, puis revivalisme, jazz, blues10 et autres. Ces formes d’expression ont précédé le gospel, le calypso11, le rock12, le reggae, le funk, le rap… Le vaudou est une religion et une culture complexe, aux différentes facettes, de l’amour au chant de guerre. Sa forme Petro, issue du peuple Kongo (bantous), est associée au feu spirituel des charmes de guérison et aux forces du mal, offensives. Enregistré à Haïti, le premier titre de cette anthologie Petro Rhythm provient d’une authentique cérémonie vaudou et donne le ton de ce florilège13.

Jazz Punk

Pour paraphraser Jack Kerouac, le jazz est une musique pour hédonistes marginaux non-conformistes qui vibrent, et non pour des « vieux riches et conservateurs ». Black Bottom est interprété par l’essentiel Jelly Roll Morton (1890-1941), l’un des grands fondateurs du jazz dans les années 190014. Né à la Nouvelle-Orléans, Jelly Roll était issu d’une famille haïtienne et pratiqua le vaudou. Comme bien des personnages hauts en couleurs de cette anthologie, il fut aussi un délinquant (à la réputation de proxénète, d’arnaqueur), un révolté et malgré son talent, un grand perdant de la vie : l’archétype punk. Née au début du siècle dans le sud des États-Unis la danse appelée black bottom supplanta le charleston et devint très populaire dans les années 1920. Black Bottom était aussi un quartier noir de Detroit. Démolie en 1960 avant le succès des disques Motown et les premiers concerts des Stooges ou du MC5, cette zone était réputée pour ses bars à musique fréquentés par des travailleurs en usine automobile. Des artistes de blues et de jazz comme Duke Ellington, Count Basie et Ella Fitzgerald s’y produisaient, faisant de cet endroit l’un des plus chauds des États-Unis. Le génial Jelly Roll Morton y joua peut-être au début de sa carrière de pianiste de vaudeville itinérant. Il nomma ainsi ce titre au tempo incitant à une danse jitterbug frénétique, à moins qu’il ne fasse simplement allusion à un « derrière noir » — ou aux deux. Les allusions au sexe (à mots couverts) étaient une forme de subversion en cette époque où les afro-américains, réputés lubriques, étaient exclus de la société blanche et où la sexualité était un tabou. Par son tempo rapide (rarement vu depuis Felix Mendelssohn !) et ses improvisations inspirées, ce morceau suggère une expression totale du corps, une libération physique et spirituelle professée par ces jeunes musiciens dévergondés : la danse jitterbug (jitter : nervosité, agitation ; jitterbug : le virus de l’agitation. Du mandingue jito : effrayé15) est l’ancêtre du pogo, danse-bousculade créée par Sid Vicious à Londres en 1976.

Très tôt, d’autres musiciens ont adopté les tempos ultra-rapides, toujours assortis d’une danse de saint-guy ad hoc — une esthétique très punk. On retrouve cette éruption d’énergie juvénile sur l’extraordinaire premier titre enregistré par Art Tatum (1909-1956), Tiger Rag (morceau de ralliement des fumeurs de marihuana). Ce pianiste virtuose aveugle n’a pu accéder à une carrière de concertiste classique en raison de son origine afro-américaine — et par goût de l’improvisation libre. Il enregistrera plus tard des compositions d’Antonín Dvorák mais leur préférait le difficile style stride de Fats Waller. Le célèbre batteur blanc Gene Krupa était connu pour son jeu exubérant très scénique qui contribua à faire découvrir le jazz au grand public. On peut l’entendre ici accompagnant Benny Goodman sur un tempo d’enfer. Artie Shaw (1910-2004) était un clarinettiste virtuose et un perfectionniste génial, cultivé, innovateur sans barrières et fonceur. Fier de son talent, ce séducteur était connu pour son arrogance et son franc-parler. Juif ashkénaze comme son grand rival clarinettiste Benny Goodman, Artie Shaw nous a laissé un héritage musical pétaradant, dont ce Traffic Jam de 1939 qui ne reprend jamais son souffle, véritable bombardement de sons multicolores orchestrés de main de maître — une claque pour un public pas toujours prêt à un tel feu d’artifice. On exigeait de lui toujours plus de morceaux doux et raffinés comme sa fameuse version de « Begin the Biguine » et tandis que d’autres comme Glenn Miller produisaient des succès commerciaux pour la danse, à l’efficace tempo moyen, Artie Shaw était l’incarnation d’une attitude très rock dans cette période « swing » où le grand public s’emparait du jazz. Riche et désabusé après la guerre, fatigué des tournées incessantes et de la demande d’un public conservateur qui freinait en permanence sa créativité — et le tempo de ses morceaux — Shaw a eu le courage de tout plaquer pour s’installer au calme en Espagne en 1954, riche et accompli. Il a ensuite consacré sa vie à l’écriture et vécut jusqu’à l’âge de 94 ans.

Koko

Avec sa vie romanesque, Slim Gaillard (1916-1991) fut à la fois l’excentrique bouffon du jazz moderne, le champion de l’argot jive et la coqueluche des boppers : connus pour leur fantastique scène dans le film Hellzapoppin (Henry C. Potter, 1941) Slim and Slam étaient à la fois de grands musiciens et des humoristes osant toutes les impertinences — ce qui pour des Afro-américains en 1941 demandait beaucoup de courage (ou d’inconscience). Cinq mois avant Pearl Harbour, leur pastiche antimilitariste (censuré pendant la guerre) des films de propagande de l’U.S. Air Force tournait en dérision un soldat qui a peur de monter dans le nouveau bombardier géant B-19, fleuron de l’armée — et finit quand même par lâcher des bombes sur un pays d’Europe. C’est sur un tempo ultra rapide, presque injouable, qu’ils discutent le coup : « Say man, let’s drop a bomb on them cats down there ». L’après-guerre est bien sûr synonyme de l’explosion du jazz moderne menée par Charlie Parker (1920-1955), un héroïnomane excentrique et autodestructeur qui a bouleversé l’histoire de la musique américaine. Punk parmi les punks, en tournant la page de la période swing avec sa musique éblouissante Bird a beaucoup contribué à faire reconnaître qu’une musique «noire» pouvait avoir une grande valeur artistique et ne pas se limiter à être à un vulgaire divertissement.

Quand Bird a quitté New York il était un roi. Mais là-bas à Los Angeles il n’était qu’un nègre de plus, bourré, bizarre, fauché, qui jouait une musique étrange. Los Angeles est une ville bâtie sur la célébration des stars et Bird n’avait rien d’une star.16

— Miles Davis

Enregistré à l’âge de vingt-cinq ans avec Dizzy Gillespie, Koko (un clin d’œil à la cocaïne ?) est l’un de ses nombreux chefs-d’œuvre, une performance sur un tempo supersonique qui fait ressembler les Ramones à des escargots sous Valium. La vertigineuse virtuosité des cinq hommes bouscule quelque peu les valeurs punks iconoclastes où ce sont d’abord l’énergie juvénile et l’intention qui comptent, jusqu’à largement encourager l’amateurisme mais doit-on pour autant disqualifier Parker et quelques autres grands jazzmen pour le haut niveau de leur interprétation, sans laquelle ils n’auraient pas été enregistrés — et qui ne retire rien à leur rafraîchissante attitude proto-punk ?

Punk Rock

Le tempo accéléré est aussi présent ici chez le bluesman Arthur Crudup, un musicien méconnu, aux morceaux simples et efficaces et dont l’œuvre est loin de se limiter aux trois compositions reprises par Elvis Presley17. Cet homme simple, qui endura toute sa vie l’oppression raciale dans le Mississippi rural, offrait dès 1946 un modèle précoce d’esthétique punk rock archi basique avec son I Want my Loving (1946). L’après-guerre a aussi été une pépinière pour le jump blues, le rock noir originel, mélange de tempos bop et de swing suractivé avec riffs de cuivres. C’est ce que firent d’autres authentiques fondateurs du rock comme Big Joe Turner avec Rebecca (1944), Tiny Bradshaw (I’m Going to Have Myself a Ball, 1950) et Roy Brown avec son hystérique Hurry, Hurry Babe (1952). On retrouve cette exubérance totale chez Sonny Parker (1925-1957), Earl Bostic (1913-1965) et Smilin’ Smokey Lynn, dont le Run Mister Rabbit est une réponse au Run Rabbit Run de Noel Gay et Ralph Butler, deux auteurs de théâtre britanniques qui évoquaient la cruauté de la chasse au lapin et avaient changé leurs paroles en « Run Adolf Run » pendant la guerre. Le jump blues a aussi accouché de la crise de nerfs musicale de Big Jay McNeely et son « honking sax ». Dès qu’ils pouvaient s’en offrir, les musiciens afro-américains de cette époque portaient souvent des costumes zoot, un style ample et excentrique porté par les zazous des années 1940 en France, et repris par les teddy boys anglais dans les années 1950. Le manager des Sex Pistols a longtemps porté et vendu ces zoot suits dans sa boutique de Londres :

Pour moi l’idée du look teddy boy c’était d’être un paon, de se faire remarquer dans la foule. Et en même temps de se sentir faire partie de ceux qu’on a dépossédés.

— Malcolm McLaren dans le film The Filth and the Fury de Julian Temple, 2000.

Les multiples reprises de Louie Louie (dont celles, archi punk, gravées par Iggy and the Stooges18 et Motörhead en 1977) ont fait de l’ombre à l’exquise et méconnue version originale de Richard Berry and the Pharaohs. Louie Louie met en scène un Jamaïcain qui se languit d’une femme de son pays et raconte à un barman nommé Louie qu’il doit partir la rejoindre. Le succès ultérieur d’une reprise des Kingsmen, dont les paroles sont incompréhensibles, a incité des centaines de groupes à inventer leurs propres paroles. Certaines étaient obscènes au point de justifier une enquête probante du FBI, gratifiant la chanson d’un culte hors de toute proportion depuis. Avec sa légende, son refrain accrocheur et quatre accords très simples (attention : le premier accord du couplet est majeur, et celui du refrain est mineur !), Louie Louie est un classique punk. La principale source musicale qui inspira les fondateurs du punk rock est bien sûr ce rhythm and blues/rock and roll d’après-guerre, qui sera repris et enregistré par des artistes clé comme les New York Dolls (Pills, Stranded in the Jungle), les Stooges (Louie Louie) ou Sid Vicious avec les Sex Pistols (Somethin’ Else et C’mon Everybody d’Eddie Cochran19).

L’archétype du style musical punk avec son balayage permanent de la guitare, tel qu’il fut défini par les premiers disques des Ramones en 1975, trouve lui aussi ses racines dans le R&B des années 1950 et les disques de Link Wray (Right Turn et sa guitare au son saturé) et Bo Diddley en particulier20 (Run Diddley Daddy). Sur I Love You So, comme les Cramps vingt ans plus tard Bo Diddley n’utilisait pas de basse :

« Je cherchais un plus gros son, et j’ai trouvé ce « freight train drive », c’est comme ça que je l’appelle. On n’était que trois mais j’avais développé un style qui donnait l’impression qu’on était au moins six. Voilà le monstre que j’avais construit [rires] ! Si tu écoutes ce que je joue, il n’y a pas de trous. Je joue la première et la deuxième guitare en même temps et dès que je commence à jouer tu es vite au courant ! C’est bourré de puissance sans interruption. De l’énergie pure21. »

Comme Blondie (reprise de l’exquis doo-wop Denise par Randy and the Rainbows) et les Real Kids (Rave On de Buddy Holly), les Ramones aimaient l’insouciance adolescente et les chansons ultra légères qu’ils propulsaient avec leur rythmique décapante. Ils ont repris, entre autres, Do You Wanna Dance, Let’s Dance, California Sun et « Surfin’ Bird » dérivé des Papa-Oom-Mow-Mow et de « The Bird Is the Word » des Rivingtons produits par Kim Fowley. D’un autre côté les Cramps («Surfin’ Bird», Goo Goo Muck, She Said ou le Boss des Rumblers qui devint leur « Garbageman »), Richard Hell and the Voidoids (« Blank Generation » dérivé de The Beat Generation), le Clash (Junco Partner, I Fought the Law, Brand New Cadillac) préféraient des thèmes plus sulfureux, des commentaires sociaux en forme de métaphores contestataires.

Protest songs

Dans les années 1940-1960 un courant de musique engagée, la protest song, a pris une place conséquente dans le panorama des musiques populaires américaines. Comme à leur manière les negro spirituals22, cette tendance attisera la contestation dans le rock. L’inclusion de grands noms de la musique folk comme Josh White23, Leadbelly, Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger, Harry Belafonte, Joan Baez ou Bob Dylan a été envisagée pour cette anthologie. Au début de sa carrière Joe Strummer adoptera même le surnom de Woody en hommage à Guthrie ; En 1981 il nommera l’album du Clash Sandinista! afin de soutenir les rebelles nicaraguayens combattus par la CIA. De Métal Urbain en France à Pussy Riot en Russie, la volonté de bousculer tous les conservatismes et de lutter contre l’oppression sera indissociable du punk rock. Cependant la musique combinant l’agitation du corps avec celle de l’esprit a toujours été au cœur de l’alchimie punk. Pour Iggy Pop et les Dead Kennedys aux États-Unis comme pour les Sex Pistols ou le Clash au Royaume-Uni, la danse libre déchaînée (évoquée dans le Mess Around de Ray Charles), l’énergie et la provocation sont les deux faces d’une même pièce. Les chansons «?folk?» interprétées à la guitare sèche sont donc quelque peu incompatibles avec les canons du genre. Une anthologie séparée est ainsi consacrée aux protest songs24 dans cette collection. Le rock et le punk rock ont eux aussi exprimé la contestation, mais en d’autres termes et selon une esthétique bien différente. C’est par exemple avec un humour adolescent que les Chips crient famine et frustration sur l’énergique Rubber Biscuit, tout comme Ronnie Cook (de Bakersfield, Californie) sur Goo Goo Muck.

Libération sexuelle

Avec leurs hurlements de mâles en rut sur des rocks hystériques comme Run Mister Rabbit (1949) ou Hurry Hurry Babe (1952), Smilin’ Smokey Lynn et Roy Brown n’ont fait qu’aller un peu plus loin dans l’expression de la frustration. Dans la société américaine ultra puritaine où le mariage était un préalable à toute relation sexuelle, l’évocation directe du désir et du sexe était perçue comme étant inacceptable. Comme lors des émeutes de mai 1968 en France, qui à l’origine contestaient l’interdiction de la mixité dans les dortoirs de l’université, le rock d’après-guerre était déjà un manifeste pour la liberté sexuelle, une subversion préalable à d’autres combats sociaux. Les morceaux de country « honky tonk », les blues « hokum » (à double sens, comme ici Roy Brown dans son brûlant Butcher Pete, un rock de 1949) et autres calypsos osés étaient considérés comme vulgaires et honteux dans les années 1950. En outre, l’idée même qu’un afro-américain puisse prétendre à la séduction choquait la grande majorité des Blancs, un tabou que le beau Harry Belafonte contribuera à briser25. Le mot « rock » lui-même signifiait à la fois se balancer, danser — et faire l’amour, comme dans le démentiel Rock This Morning de Lowell Fulson en 1946. Des musiciens comme Lowell Fulson, Red Allen ou Ray Charles sont surtout connus pour des titres moins amphétaminés que ceux inclus ici. Mais le rhythm and blues noir a toujours alterné les balades, le blues et le rock and roll, qui inspira le nerveux country boogie blanc26 et bientôt le rockabilly27 dont Elvis Presley reste le plus essentiel interprète28. Malgré la réaction souvent négative de la société bien pensante à la soudaine popularité d’Elvis en 1954-1958 (ses prestations étaient jugées trop sensuelles29), nombre d’artistes blancs adoptèrent le rock dans son sillage. Beaucoup appréciaient justement ce style pour sa défiance, son érotisme et son arrogance. En comparaison avec le Mellow Saxophone de Roy Montrell (enregistré par les Stray Cats en 1981 sous le nom de « Wild Saxophone ») ou du rockabilly Red Hot par Bob Luman, le « killer » Jerry Lee Lewis semble encore bien sage. Son High School Confidential est aussi repris ici par le nec plus ultra punk Hasil Adkins, qui, faute de groupe, jouait lui-même de tous les instruments en même temps et enregistrait seul dans sa chambre. Certains comme The Phantom sur l’irrésistible et bouillant Love Me (1958) se sont risqués à aller plus loin dans l’évocation crue de la sexualité. La voix de Jackie évoque l’orgasme sans équivoque sur le Little Girl (1958) de John & Jackie dix ans avant « Je t’aime moi non plus » de Jane Birkin et Serge Gainsbourg. Ces disques ostensiblement salaces étaient rares, marginaux et en rupture totale avec les conventions de l’époque. Les énormes succès du géant Little Richard étaient l’exception qui confirmait la règle. Bisexuel, drogué, grand innovateur et homme de scène, il fut la plus flamboyante de toutes les stars du rock mais en dépit de son apparence gay ostensible, personne n’osait encore penser à l’homosexualité. Son alter ego Esquerita fut l’une des grandes inspirations scéniques de Little Richard et copia à son tour le style androgyne de son disciple lorsqu’il enregistra ses premiers disques plutôt amateurs, dont Rockin’ the Joint inclus ici. Quant à Screamin’ Lord Sutch (au nom inspiré par Screamin’ Jay Hawkins) il fut sans doute le premier punk rocker anglais. Il reprend ici une composition de Little Richard.

I Fought the Law

Les Afro-américains Danny Taylor (You Look Bad, 1953) et Larry Williams (un proxénète dont le Bad Boy serait bientôt enregistré par les jeunes Beatles) décrivent l’indiscipline et le laisser-aller, un thème considéré diabolique sous la présidence du très conservateur général Eisenhower. Brillamment plagié en 1977 par Richard Hell and the Voidoids, The Beat Generation (1959) de Bob Mc Fadden & Dor était en phase avec l’esprit beatnik et fait l’éloge de la paresse et des allocations pour chômeurs. McFadden était une vedette des voix de dessins animés et de la publicité radio, et se moquait souvent de son métier, qu’il regardait avec recul. Rod McKuen (Dor) adaptait les chansons de Jacques Brel en anglais et a écrit des centaines de chansons pour les plus grands noms, dont Chet Baker, Johnny Cash, Sinatra et Madonna. Il vendra plus tard des millions de livres de poésie, qualifiée de kitsch par ses détracteurs.

En représentant de manière fascinante des jeunes gens en rupture avec la société, les films L’Équipée sauvage (The Wild One, László Benedek, 1953) avec Marlon Brando et La Fureur de vivre (Rebel Without a Cause, Nicholas Ray, 1955) avec James Dean avaient préparé le terrain. Mais ce fut sans doute Graine de violence (Blackboard Jungle, Richard Brooks, 1955) avec Sidney Poitier, première vraie vedette noire du cinéma, qui contribua à associer le rock avec la délinquance (le générique lança le célèbre « Rock Around the Clock »). Avec des titres comme le Juvenile Delinquent de Ronnie Allen (réponse au « I’m Not a Juvenile Delinquent » de Frankie Lymon) la criminalité a commencé à être évoquée et revendiquée ouvertement dans le rock des années 1950. Jeff Daniels met carrément en scène une bagarre au couteau sur Switchblade Sam. À l’âge de dix-huit ans à peine, Chuck Berry lui-même n’a-t-il pas été condamné à dix ans de prison pour attaque à main armée après une poursuite en voiture avec la police du Missouri ? Il a purgé trois ans détention de 1944 à 1947, et retournera deux fois en prison au cours de sa vie. Sa fascination pour les belles voitures lui a inspiré son premier succès Maybellene, une histoire de course poursuite automobile — où il rattrape une jolie fille qui conduit une Cadillac.

C’est accompagné par les Crickets de feu Buddy Holly qu’Earl Sinks chante ici l’histoire d’un bagnard sur I Fought the Law, dont le Clash enregistrerait en 1979 une fameuse version. Le groupe anglais reprendra aussi le Brand New Cadillac de l’Anglais Vince Taylor, qui avait une image de voyou en raison des émeutes survenant à ses concerts en France (et chante faux ici mais c’est pas grave c’est dans l’esprit !). Le Clash enregistrera plusieurs autres reprises, mais lorsqu’on sait que le groupe était affligé par la toxicomanie de son batteur, la plus touchante reste sans doute leur version reggae du Junco Partner de James Wee Willie Wayne, une perle R&B qui dépeint un héroïnomane purgeant une peine de prison à perpétuité au sinistre pénitencier Angola en Louisiane :

Un associé accro descendait la rue/Il était aussi défoncé qu’il pouvait l’être/Il était assommé/Assommé défoncé/Seigneur il titubait dans toutes les rues/En chantant : « Six mois c’est pas un pêcheur/Personne ici n’a pris beaucoup de temps/Moi je suis né à Angola/Je purge quatre-vingt-dix-neuf ans/Quand j’avais de l’argent/J’avais des amis dans toute la ville/Maintenant je n’ai plus d’argent/Et mes meilleurs amis me descendent ».

D’autres allusions aux stupéfiants figurent sur cet album, notamment le Pills de Bo Diddley — qui ne prenait jamais de drogues, contrairement à Johnny Thunders qui chanterait ce morceau sur le premier album des New York Dolls. Les Dolls ont aussi enregistré Stranded in the Jungle, un succès des Cadets inclus ici30. Charlie Parker n’est pas le seul héroïnomane à déployer ses talents sur cet album. Ray Charles, Little Richard et Larry Willliams ont aussi souffert de cette dépendance. Star à quatorze ans, Frankie Lymon (1942-1968) s’est accroché à l’héroïne dès l’âge de quinze ans. Il en avait seize quand sortit l’énergique Thumb Thumb, et mourut d’une dose trop forte à l’âge de vingt-cinq ans.

Free Jazz et Free Rock

À la fin des années 1950 le jazz très libre de Cecil Taylor, Ornette Coleman, Don Cherry, Albert Ayler, John Coltrane, Joe Harriott ou Sun Ra découlait directement de l’influence très innovante de Charlie Parker. Parfois dissonant et chaotique, il a fait scandale et influencera profondément Iggy Pop et les Stooges (« Fun House »), le Velvet Underground (« Sister Ray » ou «?European Son?»), Patti Smith (« Radio Ethiopia »), Captain Beefheart, John Lydon, Television et d’autres musiciens pionniers du mouvement punk des années 1970 comme le MC5 («?Starship?») :

Pour moi on essayait de faire la même chose qu’eux. Bien qu’on soit venus d’une perspective de guitare rock et eux d’un point de vue jazz traditionnel, il n’y avait pas de différence entre ce que faisaient Joseph Jarman [Art Ensemble of Chicago, NDA] ou Charles Moore et ce que faisait le MC5. On essayait tous de passer par la porte que Sun Ra, Albert Ayler, Coltrane, Pharoah Sanders et Archie Shepp avaient ouverte. C’est la musique qui nous inspirait. On faisait tout pour ça.31

Libre et libérateur, le free jazz découle d’une attitude libertaire et a joué un rôle d’exemple pour la radicalité musicale punk : Excursion on a Wobbly Rail (Cecil Taylor) était le nom de l’émission de radio créée et animée à l’université de Syracuse par Lou Reed, fondateur du Velvet Underground, et Lonely Woman Quarterly était le nom de sa feuille littéraire périodique, qui sera interdite en 1962 et lui valut une mise à l’épreuve de l’université32. Quant au groupe punk anglais emblématique The Damned, n’a-t-il pas invité le grand saxophoniste anglais Lol Coxhill, qui joua très « free » durant l’intégralité du premier « concert d’adieu » du groupe au Rainbow à Londres en 1978 ?

Bruno Blum

Merci à Jean Buzelin, John Cale, Gilles Conte, Giovanni Dadomo, Bo Diddley, Guillaume Gilles, Béatrice Givaudan, Bob Gruen, Christophe Hénault, Chrissie Hynde, Youri Lenquette, Philippe Michel, Sterling Morrison, Vincent Palmer, Gilles Pétard, Prague Frank, Lou Reed, Frédéric Saffar, Joe Strummer, Johnny Thunders et Marc Zermati.

© 2013 FRÉMEAUX & ASSOCIÉS

1. Extrait du film The Filth and the Fury de Julian Temple, 2000.

2. Extrait de Please Kill Me, The Uncensored Oral History of Punk (Grove Press, New York, 1996) de Legs McNeil et Gillian McCain. Édition française : Allia 2006.

3. Extrait du livre Punk - Sex Pistols, Clash et l’explosion punk (Paris, Hors Collection, 2006) de Bruno Blum.

4. Écouter « Zombie Dance » (Songs the Lord Taught Us, Illegal, 1980) et «Voodoo Idol» (Psychedelic Jungle, Illegal, 1981) par les Cramps.

5. Écouter l’album Virgin Islands - Quelbe & Calypso 1956-1960 (FA5403) dans cette collection.

6. Écouter l’album Voodoo in America 1926-1961 (FA5375) dans cette collection.

7. Lire Congo Square de Freddi Williams Evans (University of Louisiana at Lafayette Press, 2011. Édition française : La Tour Verte, 2012).

8. Écouter l’album Gospel - Negro Spirituals - Gospel Songs 1926-1942 (FA008) dans cette collection.

9. Écouter l’album Slavery in America à paraître dans cette collection.

10. Écouter l’album Blues - 36 Masterpieces of Blues Music (FA033) dans cette collection.

11. Écouter les albums Trinidad - Calypso Calypso 1939-1959 (FA5348) et Bermuda - Goombey & Calypso 1953-1960 (FA5374) dans cette collection.

12. Lire les livrets et écouter nos anthologies Rock ‘n’ Roll en huit volumes, couvrant la période de 1927 à 1952.

13. Lire aussi le livret en ligne (fremeaux.com) et écouter Jamaica - Folk-Trance-Possession, Roots of Rastafari 1939-1961 (FA5384) dans cette collection.

14. Écouter Jelly Roll Morton - The Quintessence 1923-1940 (FA203) dans cette collection.

15. Jean-Paul Levet, Talking That Talk, le langage du blues et du jazz (Paris, Hatier 1992).

16. L’œuvre intégrale de Charlie Parker est disponible dans cette collection.

17. Retrouvez Arthur Crudup sur notre premier volume Elvis Presley face à l’histoire de la musique américaine 1954-1956 (FA5361) qui juxtapose les interprétations d’Elvis Presley et leurs versions originales.

18. Écouter « Louie Louie » par Iggy and the Stooges sur l’album en public Metallic K.O. (Skydog, 1976).

19. Écouter The Indispensable Eddie Cochran 1956-1960 à paraître dans cette collection.

20. Écouter les deux volumes The Indispensable Bo Diddley 1955-1960 (FA5376) et 1960-1962 (FA5406 ) dans cette collection.

21. Bo Diddley parle ici de son style de 1954. Extrait de “Bo Diddley, Living Legend” de George R. White (Castle Communications, Chessington, Surrey, U.K. 1995).

22. Écouter Gospel - negro spirituals/gospel songs 1926-1942 (FA008) dans cette collection.

23. Écouter Josh White 1932-1945 (FA264) dans cette collection.

24. Écouter l’anthologie Protest Songs à paraître dans cette collection.

25. Écouter Harry Belafonte - Calypso-Mento-Folk 1954-1957 (FA5234) dans cette collection.

26. Écouter l’anthologie Country Boogie 1939-1947 (FA160) dans cette collection.

27. Écouter l’anthologie Rockabilly à paraître dans cette collection.

28. Écouter Elvis Presley face à l’histoire de la musique américaine - 1954-1956 (FA5361) qui juxtapose les interprétations d’Elvis Presley et leurs versions originales.

29. Écouter Elvis Presley face à l’histoire de la musique américaine - vol.2 1956-1957 (FA5383) qui juxtapose les interprétations d’Elvis Presley et leurs versions originales.

30. La méconnue version originale de « Stranded in the Jungle » par les Jayhawks figure sur l’album Africa in America 1920-1962 (FA5397) dans cette collection.

31. Le guitariste du MC5 Wayne Kramer à Jason Gross dans Perfect Sound Forever, novembre 1998.

32. Lire la biographie Lou Reed - Electric Dandy (Paris, Hors Collection, 2008) par Bruno Blum.

The roots of Punk Rock Music 1926-1962

by Bruno Blum

I walked up and down the King’s Road with complete anger and resentment. People were extremely absurd and still stuck into flares, platform shoes, neat hair and pretending that the world wasn’t really happening… It was an escapism that I resented… wear the garbage bag for God’s sake, and then you are dealing with it. That’s what I would be doing.

— John Lydon, aka Johnny Rotten, singer with the Sex Pistols1

The punk movement crystallized in 1977 as an open expression of rebellion and the raw reality of the tormented young. Through their subversive artistic acts and dedication, punk groups contributed to cause the mentality of their times to move on. Their rock was a radical form of expression that came from feelings of exclusion, injustice — and boredom.

No fun to be alone / In love with somebody else / Well, maybe go out, maybe stay home / Maybe call mom on the telephone.

— The Stooges, No Fun, 1969

Like swing jazz in the 30’s, modern “bop” jazz in the 40’s, free jazz in the 50’s and 60’s, and rock in the 50’s, punk rock in the 60’s and 70’s was represented as a demon in the media and rejected by conservatives.

— What is punk rock, exactly?

Joe Strummer [The Clash]: I still haven’t decided! [Laughter]. Ask someone else! Ask the nearest policeman! He’ll tell you!

— Joe Strummer speaking to the author in April 1978.

This album brings together musicians of the generations preceding the 60’s and 70’s. Those precursors were haunted by the same resentment and longing. Mainly Americans, they inspired the punk wave of the Seventies with their style, initiative, taste for transgression, youthful energy and lack of complexes.

Rock and Roll Nigger

Punk [pVNk]. n. & adj. A person of no account, a worthless fellow; a young hooligan or petty criminal. Chiefly N. Amer. colloq. Esp. in show business: a youth, a novice; a young circus animal.

— New Shorter Oxford English Dictionary.

On TV, if you’re watching a detective series like Kojak, when the cops catch a serial killer at the end they call him a dirty punk. Teachers call you that. It means you’re the worst thing there is. So all the losers and misfits grouped together and launched a movement.

— Legs McNeil, Editor of the New York magazine Punk.2

In all logic, punk rock’s main roots lie deep in the music of slave descendants by white society and grossly excluded from it by racial segregation. All of them went through an inner rebellion, and many showed conspicuous eccentricity (as here with Esquerita, Little Richard or the Chips on Rubber Biscuit).

Rejected by society / Treated with impunity / Protected by my dignity / I search for reality / New wave, new craze, new phrase.

— Bob Marley & Lee “Scratch” Perry, Punky Reggae Party, 1977

Rock musicians attracted by rebellion often claimed ties with Afro-Americans, and they covered their compositions. Patti Smith, a central figure of the punk movement who wrote the album Radio Ethiopia, says in her song “Rock and Roll Nigger” that the absolute model for finding oneself “outside of society” is “the nigger” (sic). For her, all those placing themselves outside society could in fact be assimilated to their brothers and sisters, “the niggers”.

Jimi Hendrix was a nigger / Jesus Christ and Gran-dma, too / Jackson Pollock was a nigger / Nigger, nigger, nigger, nigger / nigger, nigger, nigger / Outside of society, if you’re looking / that’s where you’ll find me.

— Patti Smith Group, Rock and Roll Nigger, 1978

With Patti’s passion for rhythm & blues and reggae, the derogatory word nigger was for her the symbol of exclusion. In the 40’s and 50’s, when voting rights and access to schooling for citizens of African origin were denied, racism was a violent reality. Originally the word “punk” meant touchwood, from the dark-coloured tinder fungus mushroom.

“The root of this English word, and its synonym ‘spunk’ which also means sperm, is the same as that of the Gaelic word ‘spong’ (touchwood) from the Latin ‘spongia’ or sponge. Punk has another meaning derived from the mushroom parasite called the tinder fungus: “bad quality” or “worthless” and, by extension, “feeble in mind or health”. So some white Americans sometimes use the word “punks” to refer to people of the same colour as the tinder fungus, because they consider them worthless.” 3

The artists gathered here were also possessed by the fever of desire (mentioned on Hot Skillet Mama with Sun Ra among others), and by the frustration belonging to the young, which was subversive because it was freely referred to in a prudish America (Love Me). Their search for identity as a generation was just as difficult to satisfy in the highly conservative context. They shared musical styles that were diverse yet convergent (risqué lyrics, bittersweet humour, defiance, refusal of established conventions in music, very fast tempos and frenzied, free dancing…) They were similar in their mal de vivre, their hedonism and their thirst for freedom, yet they came from very different social and musical horizons: from the Dixieland jazz of Jelly Roll Morton or Henry “Red” Allen to the crudest adolescent rockabilly (Hasil Adkins, The Phantom, John & Jackie, Dwight Pullen). But in retrospect, their originality, their radical nature and sincere, sometimes candid, celebration of marginality united them beyond the bounds of any particular musical form.

Standing on the corner of a busy street / everybody kept on looking at me / I was wearing sunglasses after dark, oh yeah / well you really look sharp wearin’ sunglasses after dark. — Dwight Pullen, Sunglasses after Dark, 1958.

In many respects, a number of writers, filmmakers and radical artists were part of the punk movement whether they understood it or not: from Marcel Duchamp to the Dadaists, from Guy Debord to Hubert Selby, from the beat generation to Alejandro Jodorowsky, from the expressionist trend to Andy Warhol, from humorists Professeur Choron to Coluche and Lord Buckley to Lenny Bruce, from Jean Genet to William Burroughs, and from Fritz Lang to David Lynch. In their own ways, they each shared its spirit — and its incisive attitude.

I was saying let me out of here before I was even born / It’s such a gamble when you get a face / It’s fascinatin’ to observe what the mirror does / But when I dine it’s for the wall that I set a place.

— Richard Hell, The Blank Generation, 1977.

Voodoo

Voodoo was a recurrent theme in the work of the great punk rock/post-kitsch psycho-billy group The Cramps4, who adapted the obscure instrumental Strolling in the Dark (very Link Wray-influenced) included here, turning it into their own classic “I Was a Teenage Werewolf”, which was close to the American comic-book voodoo imagery of the Fifties. Cemeteries and witch-doctors etc. are sung here by Jackie Morningstar on Rockin’ in the Graveyard. But voodoo was not just a satanic stereotype for B movies. Above all, it was/is a great religion of African origin which became mixed with African and Christian elements throughout the Americas, including The Unites States and notably in the Virgin Islands5 and Louisiana. So voodoo was one of the great spiritual forces which shaped resistance to slavery. In its way, punk rock would also be a form of resistance to oppression, man’s exploitation of man and the social status quo: apart from a few nuances, it was a direct legacy of the intensity found in Afro-American rituals involving spirits which, mixed with Negro spirituals, lay at the real roots of rock.6

On August 15th 1791 a voodoo priest named Boukman gave the signal which started the only great victorious slave rebellion in history. The revolt was led by Toussaint L’Ouverture who, with voodoo, united and galvanized his people in their struggle. In twelve years of revolution, the “Black Spartacus” triumphed against both the French plantocracy and the English army of George III, and produced history’s first black republic: Haiti. A number of slaves were deported from Haiti to Louisiana during this tumultuous period: in New Orleans, especially when Afro-Americans danced and made music in Congo Square7, it was their descendants, impregnated with voodoo, who laid the foundations of the modern music of Afro-American resistance, and its very existence was itself a challenge to authority, in Negro spirituals8 which came from centuries of slavery9, and then in revivalism, jazz, blues10 and other forms. Those forms of expression preceded gospel, calypso11, rock12, reggae, funk, rap… Voodoo is a complex religion and culture with different facets that range from love to songs of war. Its Petro form, which came from the Kongo people (Bantus), has associations with the spiritual fire of healing charms and the offensive forces of evil. Recorded in Haiti, the first title in this anthology, Petro Rhythm, comes from an authentic voodoo ceremony, and sets the tone for the rest of this set.13

Jazz Punk

To paraphrase Jack Kerouac, jazz is music for non-conformist, marginal hedonists who vibrate, and not for “rich, old conservatives.” Black Bottom is performed by the essential Jelly Roll Morton (1890-1941), one of the greats who founded jazz in the 1900’s.14 Born in New Orleans, Jelly Roll came from a Haitian family and practised voodoo. Like many colourful figures of the period, he was also a delinquent — with a reputation as a pimp and swindler —, a rebel and, despite his talents, one of life’s great losers: the archetypical punk. The dance called the Black Bottom was born in the southern States at the beginning of the century and it supplanted the Charleston to become immensely popular in the Twenties. Black Bottom was also a district in Detroit. Razed in 1960 before Motown records were hits, and before the first concerts by the Stooges or MC5, the Black Bottom district was renowned for its music bars, whose regular customers worked in automobile plants. Blues and jazz artists like Duke Ellington, Count Basie and Ella Fitzgerald used to play there, making the area one of the hottest in America. Maybe the genius Jelly Roll Morton played there early in his career as an itinerant vaudeville pianist. He gave the district’s name to this title whose tempo sent people into a frenzied jitterbug dance, unless of course it was just an allusion to a black butt… or maybe both. Sexual references (half-concealed) were a form of subversion in times when Afro-Americans — they were reputed as lewd — were excluded from white society, and when sexuality was taboo. With its rapid tempo (rarely heard since Felix Mendelssohn!) and inspired improvisations, this title suggests the total body-expression and the physical and spiritual freedom to which those licentious young musicians professed: the jitterbug — from the “jitters” (nervous agitation) and its virus, the jitter bug, and from the Mandingo word jito meaning “afraid”15 — was the ancestor of the pogo, the shuddering dance which Sid Vicious created in London in 1976.

Early on, other musicians adopted ultra-fast tempos that were always associated with impromptu jerky movements, like Saint Vitus Dance, an aesthetic that was very punk. You find this eruption of youthful energy in the extraordinary first title recorded by Art Tatum (1909-1956), Tiger Rag (a piece that was the rallying-cry of pot-smokers). This virtuoso blind pianist couldn’t hope for a career as a concert pianist because he was an Afro-American (plus the fact that he had a taste for free improvisation.) Later he recorded works by Antonín Dvorák, but he still preferred Fats Waller’s difficult stride-piano style. The famous white jazz drummer Gene Krupa was known for his exuberant playing, especially onstage, and he contributed to reveal jazz to a wide audience. You can hear him here accompanying Benny Goodman on clarinet at a breakneck clip. Artie Shaw (1910-2004) was another virtuoso clarinettist: he was cultivated, a great perfectionist, innovative, and a straight-ahead explorer who knew no limits. He was also a great seducer, and known for being arrogant and outspoken. An Ashkenazi Jew like his rival Benny Goodman, Artie Shaw left a firecracker music legacy that includes this 1939 version of Traffic Jam which never pauses for breath, dropping bombs of multicoloured orchestral sounds that hit audiences like slaps in the face, especially those who weren’t always ready for such pyrotechnics…. They increasingly demanded softer, more refined pieces, like his famous version of “Begin the Biguine”, and while others like Glenn Miller were producing efficient, mid-tempo commercial hits for dancers, Artie Shaw incarnated a very “rock” attitude in this swing era when jazz was besieged by a mass audience. Post-war, wealthy and disillusioned, tired by ceaseless touring and playing to conservative audiences who stifled his creativity — putting the brakes on the tempo of his numbers —Artie Shaw bravely dropped everything and moved to the calm of Spain in 1954; he’d accomplished his career. He spent the rest of his life writing, and lived to the ripe old age of 94.

Koko

The picaresque life of Slim Gaillard (1916-1991) made him the eccentric buffoon of modern jazz, the champion of jive slang, and one of the boppers’ favourites, all at the same time. Slim and Slam were famous for their fantastic scene in the film Hellzapoppin (Henry C. Potter, 1941); they were not only great musicians but also humorists who dared to be insolent — which took a lot of courage (unless they never gave it a thought) for two Afro-Americans in 1941. Five months before Pearl Harbour, their anti-military pastiche (censored in wartime) in a US Air Force propaganda film poked fun at a soldier afraid to board a giant B-19 bomber, the pride of the USAF (but he still went off on a raid over Europe). Taken at an ultra-fast tempo, almost unplayable, the song has a discussion between the pair of them saying, “Say man, let’s drop a bomb on them cats down there.” The post-war period, of course, was synonymous with the modern jazz explosion detonated by saxophonist Charlie Parker (1920-1955), a self-destructive heroin addict who turned American music upside down. They called him “Bird”, a punk amongst punks, and in writing a new chapter in music after the swing era with his dazzling improvisations, “Bird” made a huge contribution to the recognition of “black” music as a major artistic value, and not merely as popular entertainment.

When Bird left New York he was a king. But down in Los Angeles he was just one more nigger, stoned, bizarre and broke, who played strange music. Los Angeles is a city built on the celebration of stars and Bird was anything but a star.16

— Miles Davis

Recorded with Dizzy Gillespie when Bird was 25, Koko (a pun on “coke”?) is one of Parker’s countless masterpieces, a tune taken at supersonic speed in a performance that makes the Ramones sound like snails on Valium. The dizzy virtuosity of this five-piece shakes up iconoclastic punk values a little — juvenile energy and intentions counted above all else, to the point where amateurism was widely encouraged — but for all that, should Parker (and a few other great jazzmen) be disqualified due to the high level of their playing? Without that, they wouldn’t have been recording… And it takes nothing away from their refreshing proto-punk attitude.

Punk Rock

An accelerated tempo is also present here in the work of bluesman Arthur Crudup, a little-known musician whose pieces were simple, efficient and, taken together, much more consequent than the three compositions picked up by Elvis Presley.17 As early as 1946, Crudup, a simple man who suffered from racial oppression in rural Mississippi throughout his life, offered a precocious model of an extremely basic punk rock style with the title I Want my Loving. The post-war period was also a nursery for jump blues, the first black rock music, which had a mixture of bop tempos and hyper-active swing featuring brass riffs. It was a kind of music that other authentic rock founders played, like Big Joe Turner with Rebecca (1944), Tiny Bradshaw (I’m Going to Have Myself a Ball, 1950) or Roy Brown with his Hurry, Hurry Babe (1952) hysteria. You can find this total exuberance in Sonny Parker (1925-1957), Earl Bostic (1913-1965) and Smilin’ Smokey Lynn: his Run Mister Rabbit is a response to the Run Rabbit Run by Noel Gay and Ralph Butler, two British music-hall songwriters who wrote a song about the cruelty of rabbit-hunting and changed their lyrics to “Run Adolf Run” in wartime. Jump blues also gave birth to the nerve-racking Big Jay McNeely and his honking sax. Afro-American musicians of this period wore “zoot” suits as soon as they could afford them — echoed by the eccentric, loose-fitting clothes worn in France in the 40’s by music-fans called “Zazous” — and the suits were the ancestors of the gear worn by England’s Teddy boys a decade later. Malcolm McLaren, the Sex Pistols’ manager, used to wear zoot suits (he sold them in his London boutique).

To me the idea of the Teddy boy look was to be a peacock standing out in the crowd. And at the same time, to feel part of the dispossessed.

— Malcolm McLaren in the film The Filth and the Fury by Julian Temple, 2000.

The many later versions of Louie Louie (including the mega-punk Iggy and the Stooges18 and Motörhead in 1977) relegated the exquisite, rare original by Richard Berry and the Pharaohs to the shade. The plot of Louie Louie has a Jamaican — pining with love for a woman from back home — telling a barman named Louie that he has to go back to her. The later success of a cover by The Kingsmen, with incomprehensible lyrics, incited hundreds of bands to invent their own words. Some lyrics were so obscene that they warranted a thorough FBI investigation, and that fact alone has turned the piece into a cult-song: the legend surrounding it, plus its catchy refrain and four very simple chords — watch out: a major chord opens the verse and a minor one the chorus! —, make Louie Louie a punk classic. The main musical source which inspired the founders of punk rock was, of course, the rhythm & blues/rock ‘n’ roll of the post-war period, which was taken up and recorded by such key artists as The New York Dolls (Pills, Stranded in the Jungle), The Stooges (Louie Louie) or Sid Vicious with The Sex Pistols (Somethin’ Else and C’mon Everybody by Eddie Cochran19).

The archetype of the punk music-style, with its permanent, sweeping guitar sound (as defined by The Ramones’ first records in 1975), also had its roots in 50’s R&B and the records of Link Wray (Right Turn and its saturated guitar) and Bo Diddley especially20 (Run Diddley Daddy). On I Love You So, like The Cramps twenty years later, Bo Diddley doesn’t use a bass:

“I was lookin’ to get a bigger sound, an’ I came up with that ‘freight-train drive’, that’s what I call it. There were three of us, an’ I developed a style that would make us sound like six people at least… That’s the monster I built! [Laughter.] If you listen to what I play, there are no gaps. I play lead and second guitar at the same time and as soon as I start playing you know all about it real quick! It’s power-packed all the way. Pure energy.”21

Like Blondie (a reprise of the exquisite doo-wop song Denise by Randy and the Rainbows) and the Real Kids (Rave On by Buddy Holly), The Ramones had a taste for the carefree life of teenagers and the ultra-light songs they propelled forwards with their abrasive rhythm-section. Among others, they covered Do You Wanna Dance, Let’s Dance, California Sun and “Surfin’ Bird” (derived from the Papa-Oom-Mow-Mow and “The Bird Is the Word” by The Rivingtons, produced by Kim Fowley.) On the other hand, The Cramps (“Surfin’ Bird”, Goo Goo Muck, She Said or the Boss by The Rumblers which became their “Garbageman”), Richard Hell and the Voidoids (“Blank Generation” after The Beat Generation), and The Clash (Junco Partner, I Fought the Law, Brand New Cadillac) preferred themes that smacked of the Devil, with social commentary in the form of anti-establishment metaphors.

Protest songs

Between 1940 and 1960 there was a militant protest-song trend which became quite important in American popular music. As Negro spirituals22 had done before, the trend would rekindle rebellion in rock, and so great names in folk music came to mind — Josh White23, Leadbelly, Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger, Harry Belafonte, Joan Baez or Bob Dylan — for inclusion in this anthology. Early in his career, Joe Strummer even adopted the nickname Woody in tribute to Guthrie. In 1981 he named the Clash album Sandinista! in support of the rebels in Nicaragua hunted by the CIA. From Métal Urbain in France to Pussy Riot in Russia, the will to overturn conservatism of all kinds and fight oppression has been inseparably linked with punk rock. Yet the music that combines the agitation of the body with that of the mind was always at the heart of punk’s chemistry. For Iggy Pop and The Dead Kennedys in the USA, as for The Sex Pistols and The Clash in the UK, wild free dancing (referred to in Mess Around by Ray Charles), and energy and provocation, were all sides of the same coin. So with “folk” songs on acoustic guitar being not exactly compatible with the canons of punk, a separate anthology in this series will be reserved for protest songs.24 Rock and punk rock also expressed protest, but in other terms and according to a quite different aesthetic. Take adolescent humour, for example: The Chips cry famine and frustration in the energetic Rubber Biscuit, and so does Ronnie Cook (from Bakersfield, California) in Goo Goo Muck.

Sexual freedom

Screaming rutting males in hysteric rock songs such as Run Mister Rabbit (1949) or Hurry Hurry Babe (1952), Smilin’ Smokey Lynn and Roy Brown were only taking the expression of frustration a short step further. In an ultra-Puritan American society where people put marriage before sexual relations, any overt reference to desire or sex was considered unacceptable. As during the May 1968 riots in France, which originally protested against the ban on mixing the sexes in university dorms, rock in the post-war period was already a manifesto for sexual freedom, a subversive form that prepared for other social combats yet to come. Honky-tonk country pieces, “hokum” blues (with double-entendres, like Roy Brown here in his burning 1949 rock piece Butcher Pete) and other risqué calypso songs were considered vulgar and shameful in the Fifties. And again, the very idea of an Afro-American as a seducer was shocking for the vast majority of Whites, a taboo which handsome Harry Belafonte would continue to break.25 The word “rock” itself meant to swing, to dance, and also to make love, as in this crazy Rock This Morning from Lowell Fulson in 1946. Musicians like Fulson, Red Allen or Ray Charles were mostly known for titles with fewer amphetamines than the ones included here. But black rhythm and blues always alternated ballads, blues and rock and roll, which inspired first the edgy white country boogie26 and soon rockabilly27, whose most vital exponent was Elvis Presley.28 Despite the often negative reaction of right-minded society to Elvis Presley’s sudden popularity in 1954-1958 (his performances were deemed too sensual,29) a number of white artists adopted rock in the wake of Elvis. Indeed, many appreciated that style for its defiance, eroticism and arrogance. Compared with Mellow Saxophone by Roy Montrell (recorded by The Stray Cats in 1981 under the title “Wild Saxophone”), or the rockabilly title Red Hot by Bob Luman, Jerry Lee Lewis — the “Killer” — still seems quite mild. Jerry Lee’s High School Confidential is also taken up here by the nec plus ultra punk Hasil Adkins who, for want of a group, plays all the instruments himself at the same time while recording in his bedroom. A few, like The Phantom on the irresistible, simmering Love Me (1958), took the risk of going much further with crude sexual references. The voice of Jackie sounds unequivocally like an orgasm in Little Girl (1958) by John & Jackie, ten years before Jane Birkin and Serge Gainsbourg came up with “Je t’aime moi non plus”. These ostensibly salacious records were rare; they were marginal and broke completely with period conventions. The enormous hits of the immense Little Richard were the exception that proved the rule. Bisexual, druggie, great innovator, showman… Little Richard was the most flamboyant of all rock stars, but despite his conspicuous gayness nobody yet dared to speak openly of homosexuality. His alter ego Esquerita was one of his great stage-inspirations, who in turn copied the androgynous style of his disciple when he was recording his first, rather amateurish efforts, which include this Rockin’ the Joint title. As for Screamin’ Lord Sutch — his name was inspired by Screamin’ Jay Hawkins —, he was no doubt the first English punk rocker. Here he features in a Little Richard composition.

I Fought the Law

Afro-Americans Danny Taylor (You Look Bad, 1953) and Larry Williams (a pimp whose Bad Boy title would soon be picked up by The Beatles) based songs on the unruly, lackadaisical attitude which conservatives demonized under President Dwight D. Eisenhower. Brilliantly plagiarized in 1977 by Richard Hell and the Voidoids, The Beat Generation (1959) by Bob McFadden & Dor was in phase with the Beatnik spirit, a song in praise of idleness (and Welfare for the jobless). McFadden was a star as the voice behind numerous cartoons and radio jingles, and he was often derisory about his own role, stepping back to consider it more objectively. Rod McKuen (Dor) adapted Jacques Brel songs into English and wrote hundreds of others for some of the greatest names (including Chet Baker, Johnny Cash, Sinatra and Madonna). Later on he sold millions of books of poetry which his detractors said were kitsch.

Films were not neglected: with their fascinating portrayals of young people breaking off relations with society, The Wild One (László Benedek, 1953) with Marlon Brando, and Nicholas Ray’s Rebel without a Cause (1955, starring James Dean), had paved the way. But Blackboard Jungle (Richard Brooks, 1955) was no doubt the film which definitively associated rock with delinquency. It starred Sidney Poitier, the first genuine black film star, and the main title in the movie soundtrack featured the arch-famous “Rock Around the Clock”. Songs like Juvenile Delinquent from Ronnie Allen (the answer to “I’m Not a Juvenile Delin-quent” by Frankie Lymon) saw criminality beginning to appear as a theme, and it was openly adopted in rock songs during the Fifties. Jeff Daniels even went so far as to sing about a knife-fight (in Switchblade Sam). And hadn’t Chuck Berry himself been sentenced to ten years in gaol when barely 18, after a car-chase involving Missouri police? He served three years in detention between 1944 and 1947, and was sent back to prison again twice in the course of his lifetime. His fascination for beautiful automobiles inspired his first hit Maybellene, the story of a ride in which he chases after a pretty girl at the wheel of a Cadillac.

Accompanied by the Crickets group of the late Buddy Holly, the song I Fought the Law has Earl Sinks singing about a convict, and The Clash did a famous version of this in 1979. The English band would also cover Brand New Cadillac by Vince Taylor, who had a hoodlum-image due to the riots that ensued at his concerts in France (his singing is off-key here, but it doesn’t matter because it still feels right!) The Clash recorded several other covers, but when you learn that the band was suffering from their drummer’s drug-habit, their most touching song is no doubt their reggae version of Junco Partner by James Wee Willie Wayne, an R&B gem portraying a junkie serving time behind the bars of the sinister Angola penitentiary in Louisiana:

“Boy, he was loaded as can be / he was knocked out, knocked out loaded / he was a’wobblin’ all over the street / singing ‘Six months ain’t no sentence / yeah, and one year ain’t no time / I was born in Angola / serving fourteen to ninety-nine.’”

Other drug references appear here, notably in Pills by Bo Diddley — who never actually took any drugs, unlike Johnny Thunders who would later sing this one on the first New York Dolls album. The Dolls also recorded Stranded in the Jungle, a hit by the Cadets included here.30 Charlie Parker isn’t the only addict to show his talents in this album; Ray Charles, Little Richard and Larry Williams all had habits also. A star at fourteen, Frankie Lymon (1942-1968) got hooked on heroin when he was just fifteen, and only a year later he released the energy-filled Thumb Thumb; he died of an overdose at the age of 25.

Free Jazz & Free Rock

At the end of the 50’s the free jazz playing of Cecil Taylor, Ornette Coleman, Don Cherry, Albert Ayler, John Coltrane, Joe Harriott or Sun Ra was a direct result of the influence of the great innovator Charlie Parker. Sometimes dissonant and chaotic, free jazz caused more than one scandal and had a deep influence on Iggy Pop and The Stooges (“Fun House”), the Velvet Underground (“Sister Ray”, “European Son”), Patti Smith (“Radio Ethiopia”), Captain Beefheart, John Lydon, Television, and many other pioneering musicians in the punk movement of the 70’s, like the MC5 (“Starship”).

What we were really trying to do was, in my opinion, the same thing… even though we came from a guitar rock perspective and they came from a traditional jazz perspective. We were all trying to get through that door that Sun Ra opened up, that Coltrane opened up, that Pharoah Sanders and Archie Shepp opened up. That was the music that inspired (us). That’s what we were striving for.31

Liberated and liberating, free jazz was born of a libertarian attitude and served as an example of how radical punk music could be: Excursion on a Wobbly Rail (Cecil Taylor) was the name of a radio show created and produced at Syracuse University by Lou Reed, the founder of the Velvet Underground, and Lonely Woman Quarterly was the name of its literary pendant, which Lou Reed edited. It was banned in 1962 and Lou was put on probation at Syracuse.32 As for the emblematic English punk band The Damned, didn’t they have the great English sax-player Lol Coxhill as a guest? He played very “free” for the whole of the band’s first farewell concert in ‘78 at London’s Rainbow Theatre.

Bruno BLUM

Adapted into English by Martin DAVIES

Thanks to Jean Buzelin, John Cale, Gilles Conte, Giovanni Dadomo, Bo Diddley, Guillaume Gilles, Béatrice Givaudan, Bob Gruen, Christophe Hénault, Chrissie Hynde, Youri Lenquette, Philippe Michel, Sterling Morrison, Vincent Palmer, Gilles Pétard, Prague Frank, Lou Reed, Frédéric Saffar, Joe Strummer, Johnny Thunders and Marc Zermati.

© 2013 FRÉMEAUX & ASSOCIÉS

1. From the film The Filth and the Fury, dir. Julian Temple, 2000.

2. From Please Kill Me, The Uncensored Oral History of Punk (Grove Press, New York, 1996) by Legs McNeil & Gillian McCain.

3. From Punk - Sex Pistols, Clash et l’explosion punk by Bruno Blum, Paris, Hors Collection, 2006.

4. Cf. “Zombie Dance” (Songs the Lord Taught Us, Illegal, 1980) and “Voodoo Idol” (Psychedelic Jungle, Illegal, 1981) by The Cramps.

5. Cf. Virgin Islands - Quelbe & Calypso 1956-1960 (FA5403).

6. Cf. Voodoo in America 1926-1961 (FA5375).

7. Cf. Congo Square, Freddi Williams Evans, University of Louisiana at Lafayette Press, 2011.

8. Cf. Gospel - Negro Spirituals - Gospel Songs 1926-1942 (FA008).

9. Cf. Slavery in America (to be released).

10. Cf. Blues - 36 Masterpieces of Blues Music (FA033).

11. Cf. Trinidad - Calypso Calypso 1939-1959 (FA5348) and Bermuda – Goombey & Calypso 1953-1960 (FA5374).

12. Cf. the eight volumes of the Rock ‘n’ Roll anthologies covering the period 1927-1952.

13. Cf. Jamaica - Folk-Trance-Possession, Roots of Rastafari 1939-1961 (FA5384) and the booklet online at www.fremeaux.com.

14. Cf. Jelly Roll Morton - The Quintessence 1923-1940 (FA203).

15. Jean-Paul Levet, Talking That Talk, le langage du blues et du jazz, publ. Hatier, Paris, 1992.

16. The complete works of Charlie Parker are available in this collection.

17. Arthur Crudup can be heard in our first volume of Elvis Presley & the American Musical Heritage 1954-1956 (FA 5361), which has Presley versions alongside the originals he “covered”.

18. Cf. “Louie Louie” by Iggy and the Stooges on the live album Metallic K.O. (Skydog, 1976).

19. Cf. The Indispensable Eddie Cochran 1956-1960 (future release).

20. Cf. The Indispensable Bo Diddley Vol. 1, 1955-1960 (FA5376) & Vol. 2, 1960-1962 (FA5406).

21. Bo Diddley talking about his 1954 style in “Bo Diddley, Living Legend”, George R. White, Castle Communications, Chessington, Surrey, U.K., 1995.

22. Cf. Gospel - Negro spirituals/gospel songs 1926-1942 (FA008).

23. Cf. Josh White 1932-1945 (FA264).

24. Cf. Protest Songs (future release).

25. Cf. Harry Belafonte - Calypso-Mento-Folk 1954-1957 (FA5234).

26. Cf. Country Boogie 1939-1947 (FA160).

27. Cf. the Rockabilly anthology (future release)..

28. Cf. Elvis Presley & the American Musical Heritage 1954-1956 (FA5361), which has Presley versions alongside the originals he covered.

29. Cf. 28 above, Vol.2 1956-1957 (FA5383).

30. The little-known original version of “Stranded in the Jungle” by the Jayhawks appears on the album Africa in America 1920-1962 (FA5397).

31. MC5 guitarist Wayne Kramer, speaking to Jason Gross in Perfect Sound Forever, November 1998.

32. In Lou Reed - Electric Dandy, Bruno Blum, Paris, Hors Collection, 2008.

Disc 1

1. Petro Rhythm - Vaudou congregation

(traditional)

Unknown vocals, percussion, whistle. Haiti, circa 1960.

2. Black Bottom Stomp - Jelly Roll Morton’s Red Hot Peppers

(Joseph LaMothe as Jelly Roll Morton)

Omer Simeon-cl; George Mitchell-tp; Edward Ory as Kid Ory-tb; Ferdinand Joseph LaMothe as Jelly Roll Morton-p; Johnny St. Cyr-bj; John Lindsay-b; Andrew Hilaire-d. Chicago, September 15, 1926.

3. Tiger Rag - Art Tatum

(Nick LaRocca)

Arthur Tatum Jr. as Art Tatum-p. New York, August 5, 1932.

4. Swing Is Here - Gene Krupa’s Swing Band W/

Benny Goodman

(Eugene Bertram Krupa aka Gene Krupa, David Roy Eldridge aka Roy Eldridge, Leon Brown Berry aka Chu Berry)

David Roy Eldridge aka Roy Eldridge -tp; Benny Goodman-cl; Leon Brown Berry aka Chu Berry-ts; Jess Stacy-p; Alla Reuss-g; Israel Crosby-b; Eugene Bertram Krupa as Gene Krupa-d. New York City, February 29, 1936.

5. Traffic Jam - Artie Shaw and his Orchestra

(Teddy McCrae, Arthur Jacob Arshawsky aka Artie Shaw)

Chuck Peterson, John Best, Bernie Privin-tp; George Arus, Les Jenkins, Harry Rodgers-tb; Les Robinson, Hank Freeman, Tony Pastor, Georgie Auld-saxes; Arthur Jacob Arshawsky as Artie Shaw-cl; Bob Kitsis-p; Al Avola-g; Sid Weiss-b; Buddy Rich-d. June 12, 1939.

6. B-19 - Slim and Slam

(Bulee Gaillard aka Slim Gaillard, Richard D. Squires aka Harry D. Squires)