- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

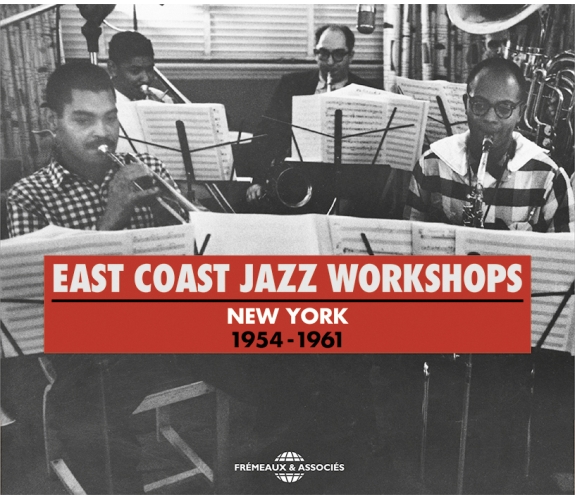

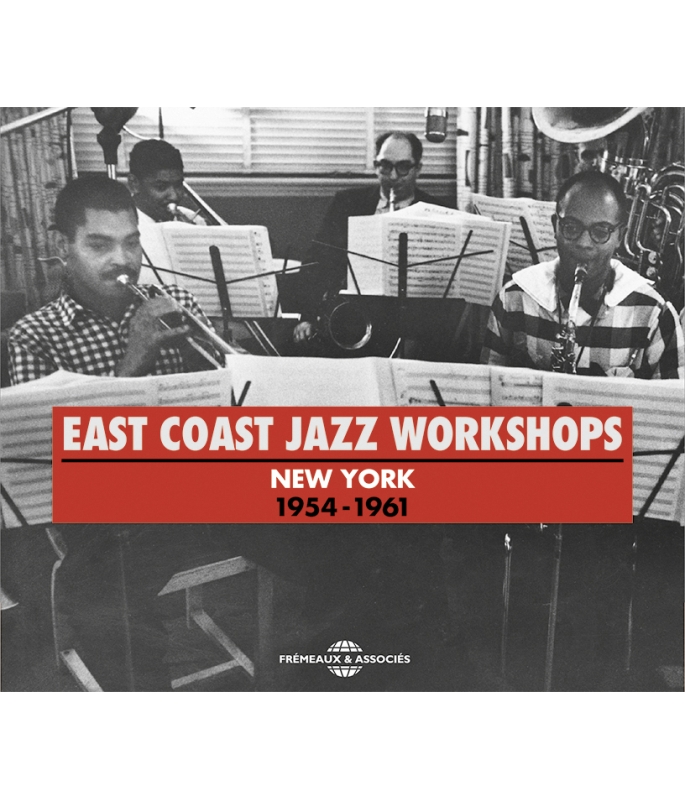

EAST COAST JAZZ WORKSHOPS

Ref.: FA5392

Artistic Direction : ALAIN TERCINET

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Total duration of the pack : 2 hours 31 minutes

Nbre. CD : 2

EAST COAST JAZZ WORKSHOPS

EAST COAST JAZZ WORKSHOPS

“In those days, music was in a period some have labeled the “cool school”. Most musicians spent their time practicing chord changes and checking out Stravisky or Bartok. Nobody was making money, but musically, it was an interesting time.” Helen MERRILL

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Cohn Not CohenFour Brass, One Tenor00:02:491955

-

2HarooshFour Brass, One Tenor00:04:051955

-

3The Return Of The Red HeadThe Sax Section00:03:311956

-

4Poor Dr. MillmossManny Albam00:05:361957

-

5Anything GoesManny Albam00:03:441955

-

6Confusion BluesBob Brookmeyer00:04:251956

-

7Darn That DreamBob Brookmeyer00:04:291959

-

8VenezuelaJohn Benson Brooks00:04:381956

-

9Boo WahHenri Renaud's US Stars00:04:551954

-

10SaltTony Fruscella00:04:391955

-

11Joe The ArchitectPhil Sunkel's Jazz Band00:03:051956

-

12Study In TurquoiseJoe Haliday and His Band00:03:021957

-

13CarmenoochThe Westchester Workshop00:04:081956

-

14Bond StreetTom Talbert00:02:401956

-

15White HouseThe Freddy Merkle Group00:03:431957

-

16Miss Wise-KeyDon Elliot Octet00:02:301956

-

17Evening in ParisQuincy Jones00:04:081956

-

18Kerry DanceThe Orchestra of Gigi Gryce00:03:021955

-

19Nica's TempoDonald Byrd - Gigi Gryce Jazz Lab00:05:291957

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Blues For PabloHal McKusick Jazz Workshop00:04:541956

-

2Miss ClaraHal McKusick Jazz Workshop00:04:071956

-

3Ballad Of Hix BlixGeorge Russsell & His Smalltet00:03:191956

-

4Ye Hypocrite, Ye BelzebuthGeorge Russsell & His Smalltet00:03:531956

-

5JambangleGil Evans & Ten00:05:021957

-

6La Plus Que LenteGerry Mulligan Sextet00:03:331956

-

7Makin' WhoopeeGerry Mulligan Sextet00:04:101956

-

8On a RiffAndré Hodeir00:02:571957

-

9Green BluesThe Teddy Charles Trenet00:04:111956

-

10T.C.'s GrooveJazz Composers Workshop - Teo Macero00:03:471955

-

11Gregarian ChantCharles Mingus Sextet00:02:511954

-

12GhensisGil Mellé00:03:481956

-

13Chinese Water TortureBilly Byers00:03:461956

-

14Dancing in The DarkHal Schaefer00:02:201955

-

15Zonkin'George Handy00:04:081956

-

16Walkin On The AirTony Scott Tentette00:03:001956

-

17DjangoMichel Legrand00:04:141956

-

18Fugue For Jazz OrchestraThe John Glasel Brasstet00:02:241959

-

19Davenport BluesBill Russo00:03:441959

-

20Angkor WatJohn Carisi Orchestra00:06:231961

East coast Jazz workshops FA5392

EAST COAST JAZZ WORKSHOPS

new york 1954-1961

EAST COAST JAZZ WORKSHOPS

new york 1954-1961

« Au temps de l’Âge d’Or, de lointains thuriféraires croyaient que le bon jazz s’écrivait avant de se jouer ; c’était le contraire. Un demi-siècle plus tard, c’est en passant par l’écriture qu’on eût évité le marasme : la majorité des musiciens et la quasi-totalité du public ne jurait plus que par l’improvisation. D’autres que moi expliqueront, peut-être, pour quelles raisons l’histoire du jazz a évité, vers 1960, le tournant qu’il eut fallu prendre, pourquoi les œuvres de jazz sont restées dans les tiroirs, pourquoi celles qui ont été publiées sont demeurées confidentielles et pourquoi, diffusées à doses homéopathiques, elles ont été privées de toute influence. »

André Hodeir «L’improvisation simulée – Sa genèse. Sa fonction dans l’œuvre jazz» Cahiers du Jazz Nlle série n°11, 1997.

Fin 1955 apparut chez les disquaires new-yorkais un microsillon à la présentation particulièrement austère : fond blanc, en noir les silhouettes traitées au trait de trois trompettes et d’un ténor posé sur son support, en bistre le titre « Four Brass, One Tenor ». Pas de nom de leader ; une seule mention, « The Jazz Workshop » dans laquelle le graphisme fantaisiste du mot « Jazz » avait probablement été dessiné par Jim Flora.

À l’origine de cet album, Jack Lewis, ancien directeur artistique de RCA Victor pour la Californie - il y avait enregistré le grand orchestre de Shorty Rogers. Le producteur Manny Sachs l’avait rappelé à l’Est pour lui demander d’imaginer un nouveau projet destiné au département jazz. En résulta une collection baptisée « The RCA Jazz Workshop ». Pour y entrer, selon Hal Schaefer l’un des musiciens contacté « il fallait que vous soyiez à la fois compositeur, arrangeur et instrumentiste ; le tout réuni en une seule personne. » Par le biais de cette initiative, une « major company » officialisait une tendance dans l’air depuis déjà quelque temps.

Il semble bien que le vocable « workshop » - c’est-à-dire « atelier » -, accolé au mot jazz, soit apparu pour la première fois à la fin de 1953 sur la couverture d’un LP 25 cm publié chez Debut Records. Il réunissait quatre trombones - J.J. Johnson, Kai Winding, Bennie Green, Willie Dennis – et une rythmique. L’année suivante, l’un des producteurs qui n’était autre que Charles Mingus reprendra le terme pour son compte et le conservera tout au long de sa carrière pour chapeauter ses divers ensembles.

À l’époque, une question qui se posait depuis un certain temps attendait une réponse urgente : «Que jouer afin de ne pas avoir l’air de piétiner avec bonne conscience les plate-bandes des boppers historiques ? » Depuis la fin de 1953, Art Blakey, un vétéran du bop, présentait ses « Jazz Messengers ». Parmi eux, Horace Silver : « Bien sûr nous jouions be bop. Lorsque Art et moi étions ensemble, la seule différence venait du fait que, dans la mesure où j’étais quelqu’un qui aimait le blues et le gospel, ces musiques s’imposèrent plus largement dans le bop. Du coup ce n’était pas seulement du be bop. Nous y avons introduit Doodlin’, The Preacher qui penchaient nettement du côté funky, nous insérions le blues et le gospel dans la musique, ce que le be bop n’avait pas fait auparavant (1). »

Qualifiée de « Hard Bop », cette école emporta l’adhésion des amateurs car, au fond, elle les rassurait. Les tonnerres libérés par Art Blakey et les hymnes entonnés par Horace Silver couvrirent la petite musique de ceux qui se sentaient peu concernés par les remèdes promulgués par les « Jazz Messengers ». D’autant plus que nombre d’entre eux, mais pas tous, n’appartenaient pas à la communauté afro-américaine. Pour eux, le nonette de Miles Davis avait suggéré une réponse beaucoup plus prometteuse au problème de l’après-bop.

Au cours d’une conférence donnée le 8 avril 1995 à la Washington University de St-Louis, le saxophoniste, compositeur, arrangeur et auteur Bill Kichner déclara à ce propos : « Il a seulement gravé une douzaine de morceaux pour Capitol et joué en public dans un club pendant deux semaines en tout et pour tout, cependant ses enregistrements, par l’influence qu’ils ont eu, ont été comparés à ceux du Hot Five et du Hot Seven d’Armstrong ainsi qu’à d’autres classiques signés Duke Ellington, Count Basie et Charlie Parker … L’influence du Birth of the Cool Band s’est étendue beaucoup plus loin que la West Coast, se manifestant dans toutes sortes de contextes inattendus. Dans les années 50, des compositeurs-arrangeurs comme Gigi Gryce, Quincy Jones et Benny Golson ont produit des disques usant de la même approche, comme le fit le traditionaliste Dick Cary qui usa de ce style pour orchestrer quelques chevaux de bataille du Dixieland. Thelonious Monk, en compagnie de l’arrangeur Hall Overton, sollicita une instrumentation pratiquement identique lors de son fameux concert de Town Hall en 1959. La dimension du Birth of the Cool Band montrait qu’elle offrait toutes sortes de possibilités pour une écriture jazzistique créative (2). »

Convaincus que l’arrangement constituait la base de renouvellement du jazz, à l’image de ce qui se passait en Californie, quelques musiciens new-yorkais, anciennement parties prenantes dans le Birth of the Cool Band, sympathisants ou convertis de fraîche date, s’employèrent à le prouver par l’exemple. Suivant le modèle offert par la formation qui avait entourée Miles, ils réunirent des ensembles de taille moyenne, à géométrie variable, allant du sextette à des formations de dix ou douze musiciens. La variété des instrumentations sollicitées y concurrençait ce qui était devenue une norme sur la West Coast : trois altos pour Hal Schaefer, trois trompettes et un ténor pour Al Cohn, quatre trombones pour Billy Byers, l’accordéon d’Orlando DiGirolamo chez Teo Macero, cinq cuivres soutenus par une basse et une batterie à l’initiative de John Glasel…

Un mouvement qui connut son apogée entre 1954 et 1960 et que l’évolution du jazz oblige à qualifier de « souterrain ». Issue de formations labellisées « workshops » ou interprétée par nombre d’ensembles similaires mais sans étiquette, la musique issue de ces « ateliers » - quelquefois d’une belle complexité - ne bénéficia pas d’une véritable reconnaissance en dépit des perspectives qu’elle laissait entrevoir. Dans sa diversité qui pouvait aller même jusqu’à l’antagonisme, elle portait témoignage des préoccupations jazzistiques de l’époque. Sans œillères puisque trois Français aux préoccupations proches - Henri Renaud, André Hodeir et Michel Legrand, aussi différents entre eux que les Américains l’étaient - pourront s’exprimer dans les studios new-yorkais.

Au fil des séances, à la façon de ce qui se passait sur la côte ouest, se retrouvaient souvent les mêmes interprètes qui, en dépit de leurs grandes qualités, ne bénéficièrent guère pour la plupart de la reconnaissance publique. Osie Johnson et Milt Hinton, respectivement batteur et bassiste, le guitariste Barry Galbraith, Hal McKusick, Nick Travis, les saxophonistes baryton Sol Schlinger, Gene Allen ou Danny Bank. Art Farmer dont on ne sait s’il faut plus vanter l’éclectisme ou la qualité de ses interventions ; Zoot Sims à propos duquel Ronnie Scott faisait remarquer que « les clients les plus blasés revenaient à la vie et souriaient aux anges lorsqu’il commençait à jouer ».

Variété de styles, éclectisme des musiciens impliqués, s’il fallait sacrifier au petit jeu favori des critiques de jazz, à savoir apposer des étiquettes, les arrangeurs dans le cas présent pourraient être rangés selon deux familles, les « néo-classiques » et les « expérimentateurs ». Avec toutes les nuances intermédiaires possibles et imaginables. Le premier groupe prolongerait l’esprit des petites formations en activité durant l’ère du swing. Toutefois, connaissant sur le bout des doigts le be bop et ses avancées, chacun des représentants de cette tendance savait en tirer profit à leur guise. Al Cohn à propos de son « Natural Seven » : « Dans ces morceaux, nous avons essayé de retrouver le feeling des Kansas City Seven, à notre façon bien sûr ». Les «expérimentateurs », quant à eux, cherchaient à défricher une voie dépassant le bop.Chacun à sa manière, quitte à lorgner parfois en direction de la musique dite « sérieuse ».

Kirk Silsbee : « Phil Woods me raconta que ce fut dans le living room d’Al Cohn qu’il entendit la musique la plus magnifique. Al possédait une merveilleuse science de l’harmonie et de la composition mais il n’y avait rien d’académique dans son jeu ou dans son écriture. Tout était naturel et musical (3). » Cohn not Cohen, Haroosh, The Return of the Red Head en portent témoignage. Faut-il ajouter à la liste Boo Wah, tiré d’une série d’enregistrements réalisés à New York par Henri Renaud missionné par le label Swing ? Les notes de pochette originales signées Charles Delaunay le laissent supposer. La version de Boo Wah qui fut publiée n’était pas définitive, sa finalisation n’ayant pu être mise en boîte faute de temps. Ses qualités surpassant ses quelques faiblesses, Al Cohn, J. J. Johnson qui remplaçait au pied levé Brookmeyer parti en tournée, Jerry Hurwitz (alias Jerry Lloyd), trompettiste rare - il abandonnera bientôt la musique -, Henri Renaud méritent d’y être écoutés.

Extraits de « Four Brass, One Tenor », Cohn not Cohen et Haroosh mettaient aux prises Al Cohn et quatre trompettistes – Joe Newman prend les solos, Thad Jones expose Haroosh – , soutenus par l’incomparable Freddie Green. Mordant dans le premier morceau, lyrique au long du second, Al Cohn bâtit des « solos qui ressemblent à des thèmes et le développement de ses improvisations témoigne d’une continuité dans la pensée créatrice, d’une logique digne d’Armstrong » (Henri Renaud).

Affichant à son tour l’intention d’adopter la formule « workshop », la compagnie phonographique Epic confia à Al Cohn la réalisation d’un album. À trois reprises il devait y mettre en scène, de façons différentes, une section de saxes s’appuyant sur une rythmique. Pour l’une d’entre elles, il fit appel à Zoot Sims qui, dans The Return of the Red Head, prend le premier la parole, Al Cohn le suivant avant que ne s’instaure entre eux un dialogue sous forme de 4/4. Des échanges qui se prolongeront durant une bonne trentaine d’années, sur scène et en studio. Après qu’ils se soient retrouvés une nouvelle fois quatre mois plus tard. Al Cohn : « J’ai pris beaucoup de plaisir à cette session ; une séance d’enregistrement vraiment agréable. Nick Travis, Buddy Jones à la basse, Osie Johnson, Galbraith et Zoot – il jouait de l’alto et moi du baryton … Nous sommes arrivés sans avoir vu la musique préalablement à notre venue au studio. Ce n’était pas difficile. C’était du John Benson Brooks ; quelqu’un de très talentueux, amusant, intelligent aussi (4). » Chaleur et simplicité, rigueur et efficacité, les qualités de Venezuela sont identiques à celles qui marquent les partitions d’Al Cohn.

À Manny Albam qui l’assista sur le volume inaugural de la série « RCA Victor Jazz Workshop », « Four Brass, One Tenor », fut attribuée la réalisation de l’un des suivants. Saxophoniste baryton, au début des années 1950 il avait abandonné une carrière d’instrumentiste pour se consacrer à l’écriture. En suivant un credo bien précis : « Je ne peux pas couper les ponts avec la tradition dont nous venons tous et qui devrait servir de base pour quiconque travaille dans le jazz. Si l’écriture doit concerner le jazz, elle doit amalgamer les éléments qui composent cette tradition – le beat, l’improvisation dans un encadrement organisé et le feeling unique qui lui est propre ». Il insistait en outre sur la nécessité d’une interdépendance étroite entre écriture et improvisation.

Manny Albam réunit pour l’occasion deux trompettes, deux trombones, deux saxes et deux rythmes (basse et batterie). Une dualité instrumentale qui, pour inusitée qu’elle fut, fait merveille sur la chanson de Cole Porter, Anything Goes, les trompettistes Nick Travis et Jimmy Nottingham y interprétant respectivement leurs parties sans et avec sourdine.

Albam revendiquait l’influence qu’avait exercée sur lui Duke Ellington, une référence manifeste au long des « Jazz Greats of Our Time », deux LP réunissant ses compositions originales et arrangements enregistrés par la fine fleur des musiciens établis les uns à New York, les autres à Los Angeles. Inspiré à son auteur par un personnage de l’humoriste James Thurber, Poor Dr. Millmoss s’ouvre sur une confrontation à deux saxophones baryton tenus par Mulligan et Cohn (ordre respecté lors des chorus et durant les 4/4). Une partition festive qui donne la parole à chacun des interprètes. Parmi eux un autre ami d’Henri Renaud : « … Brookmeyer, c’est un musicien original et déconcertant. D’une vaste culture musicale, il peut écrire de la musique atonale puis évoquer dans ses partitions King Oliver et Louis Armstrong. Il connaît aussi bien Jelly Roll Morton que Gil Evans. Comme soliste, il recourt aux longues phrases legatos des improvisateurs d’aujourd’hui puis sacrifie à un jeu beaucoup plus contrasté et beaucoup plus expressionniste, dérivé manifestement du style des grands solistes « classiques ». En vérité, le qualificatif de « moderne traditionaliste » semble avoir été inventé pour lui (5). »

Partenaire privilégié de Gerry Mulligan durant plusieurs décennies, partie prenante dans l’un des trios les plus audacieux de Jimmy Giuffre, Brookmeyer revendiquait son amour pour le jazz de sa ville natale, Kansas City. Tout en s’autorisant quelques coups de canif dans leur contrat de mariage. Une ambiguïté féconde qui fait le charme de deux pièces, Confusion Blues qui aurait pu servir d’introduction à son album « Traditionalism Revisited » et Darn That Dream que Kenneth Hagood avait enregistré accompagné par le Birth of the Cool Band de Miles Davis. Est-ce le fait du hasard ? Toujours est-il que Brook convoqua à son tour cor et tuba pour rendre justice au lyrisme désenchanté qui imprègne ce vieux succès. Sans pour autant tomber dans le pastiche.

Bob Brookmeyer restera bien présent sur la scène du jazz jusqu’au début de ce siècle ; il en sera tout autrement pour nombre de ceux qui représentèrent les forces vives des « ateliers ». Injustement oublié, Phil Sunkel, trompettiste, cornettiste, sollicité aussi bien par Al Cohn et Gil Evans qu’engagé dans le Concert Jazz Band de Gerry Mulligan. Comme arrangeur, il collabora au seul album officiel signé par l’un de ses confrères élevé au rang de mythe, Tony Fruscella. En est extrait Salt, une variation sur le blues écrite et superbement arrangée par Sunkel qui, à la tête de son propre Jazz Band, dirigea Joe the Architect. Un autre de ses thèmes dédié à l’un de ces clochards célestes chers à Jack Kerouac. Tout aussi oublié des dictionnaires du jazz, le chef d’orchestre et arrangeur Tom Talbert. Il avait dirigé en Californie une formation qui compta dans ses rangs - entre autres -Lucky Thompson et Art Pepper. De l’arrangement qu’il avait écrit alors sur I’ve Got You Under my Skin, Maria Schneider dira qu’ « il portait la marque du génie ». Ayant gagné la côte est, Tom Talbert travailla en étroite collaboration avec Oscar Pettiford présent dans le Bond Street de Fats Waller où les ensembles orchestraux dialoguent avec le piano tenu par George Wallington.

Vinnie Riccitelli avait créé le «Westchester Workshop » qui, dans son énoncé, revendiquait une appartenance à l’un des soixante-deux comtés de l’état de New York. Un octette à l’instrumentation classique dont le seul album fait regretter que les qualités d’écriture de Riccitelli n’aient pas eu plus souvent l’occasion de se concrétiser - on ne retrouvera guère sa trace qu’en tant qu’instrumentiste dans les grands orchestres de Dick Meldonian / Sonny Igoe et de Lew Anderson. Mettant en valeur le ténor Carmen Leggio, son Carmenooch ne pouvait se passer d’adresser un clin d’œil à Georges Bizet. Autre musicien oublié, Joe Holiday. Un ténor fort intéressant venu de Sicile, marqué par les styles de Wardell Gray et de Stan Getz, auteur du délicat Study in Turquoise qui bénéficia des bons soins d’Ernie Wilkins. Un arrangeur (également saxophoniste) dont la réputation s’était bâtie à partir des partitions qu’il avait concoctées pour son ancien employeur, Count Basie mais aussi grâce à celles destinées à Dizzy Gillespie, Harry James, Tommy Dorsey et autres grandes formations. Son terrain de chasse favori qu’il abandonnait parfois pour sacrifier à l’écriture pour moyens ensembles.

Si la renommée d’Ernie Wilkins n’a pas souffert au fil du temps, il existe un arrangeur-compositeur sur lequel les feux des projecteurs n’ont cessé de rester braqués. Quincy Jones. Personnalité du show business, membre de la « jet set », il demeure avant tout un jazzman. « Je préférerais que ma musique ne soit pas rangée dans une catégorie quelconque, pour la bonne raison qu’elle a probablement été influencée par chaque voix originale que j’ai entendue dans et en dehors du jazz, peut-être par toutes, du chanteur de blues Ray Charles à Ravel (6) » écrivait-il en préface à « How I Feel About Jazz ». Un album dont est extrait Evening in Paris pour lequel Zoot Sims vint tout spécialement de Washington enregistrer le solo que Quincy lui avait réservé au sein de son tentette. Une formule instrumentale qu’il n’utilisa que parcimonieusement pour son usage personnel, préférant écrire pour des formations plus étoffées. Il en était tout autrement lorsqu’il travaillait pour les autres, témoin ce Miss Wise-Key destiné à Don Elliott qui contient une remarquable partie de batterie signée Osie Johnson. Une partition que Quincy conçut avant de venir compléter son éducation musicale sous la férule de Nadia Boulanger en France. Un pays où, à l’origine, il avait montré ses talents d’écriture au long des séances d’enregistrement clandestines organisées autour de Clifford Brown, durant une tournée de l’orchestre Hampton.

L’avait alors épaulé Gigi Gryce, un saxophoniste alto qui considérait que Tadd Dameron était « l’un des plus grands, des plus inventifs, des plus aventureux arrangeurs de notre temps ». Goût pour la beauté des lignes mélodiques, audaces harmoniques, chorus faisant fi des structures traditionnelles, dans son écriture Gigi Gryce entendait faire fructifier l’héritage de son maître à penser. Co-directeur du « Jazz Lab », il y accueillait à l’occasion des invités. Pour mettre en boîte une nouvelle version de Nica’s Dream, l’une de ses compositions les plus célèbres, en sus du baryton Sahib Shihab vinrent l’assister Julius Watkins au cor et le tuba de Don Butterfield. Deux instruments auxquels Gigi Gryce avait déjà eu précédemment recours sur Kerry Dance - un air du folklore irlandais souvent cité par Charlie Parker – recréant pour l’occasion le sound du nonette de Miles Davis. À l’instar de ce que Shorty Rogers avait fait à Los Angeles quatre ans plus tôt.

Si l’héritage du Birth of the Cool Band allait faire florès auprès d’un nombre conséquent d’arrangeurs, son initiateur vivait pour le moment une véritable traversée du désert. Jusqu’alors n’étaient venues s’ajouter au palmarès de Gil Evans qu’une séance esthétiquement inachevée avec Charlie Parker et quelques partitions destinées à divers vocalistes dont Johnny Mathis. Fort heureusement, le vent allait tourner. Avant que Miles ne fasse de nouveau appel à lui, Helen Merrill avait imposé sa participation à l’un de ses albums et, en 1956, Teddy Charles lui avait commandé une partition. Trois mois plus tard, c’était au tour d’Hal McKusick auquel avait été confié la direction d’un volume du « RCA Victor Jazz Workshop ». Instrumentiste, compositeur, il fut l’un des musiciens-clé de la nébuleuse « ateliers », montrant dans un jeu marqué à l’origine par les discours de Parker et de Lee Konitz, une finesse et une intelligence musicale rares, aussi bien à l’alto ou à la clarinette qu’à la flûte. Ses classes ayant été effectuées dans une bonne dizaine de grands orchestres, en 1954, il avait monté avec Barry Galbraith un quartette sans piano, afin d’explorer les possibilités sonores offertes par l’alliage alto (ou flûte) /guitare. Un jumelage sollicité durant l’exposé de Ballad of Hix Blewitt.

Gil Evans fournit à Hal McKusick deux partitions dont Blues for Pablo que réenregistrera Miles Davis. Sa version princeps inspira ce commentaire à André Hodeir : « Dans les années cinquante, les compositeurs de jazz ont cherché à donner à certaines phrases écrites pour les pupitres de l’orchestre un peu de la souplesse et de la liberté rythmique qu’avaient acquis les improvisateurs. Ainsi dans la première version de Blues for Pablo (1956), Gil Evans s’efforce-t-il de modeler l’écriture des unissons à l’image de la phrase chorus. La période qui commence comme une exposition du thème, s’infléchit dès la troisième mesure pour évoluer vers une habile suggestion de « double time » (7). »

Grâce à son ouvrage publié en 1953 « The Lydian Chromatic Concept Of Tonal Organization for Improvisation », George Russell se posait comme celui qui entendait approfondir les recherches sur une union possible jazz / musique modale. Le rencontrant dans un drugstore où, poussé par la nécessité, il occupait un poste de serveur, Hal McKusick lui demanda si écrire pour lui l’intéresserait… Russell lui apporta Miss Clara, une pièce particulièrement complexe comportant un interlude orchestral en 6/4.

S’étant vu confier à son tour la direction d’un « Jazz Workshop » - sur l’insistance d’Hal McKusick -, George Russell réunit un sextette où figurait un pianiste qu’il venait de découvrir, Bill Evans. Son solo sur Ye Hypocrit, Ye Belzebuth ou l’accompagnement quasiment « monkien » qu’il pratique au long de Ballad of Hix Blewitt explique la fascination qu’il avait exercé sur l’arrangeur.

Le volume du « RCA Victor Jazz Workshop » dirigé par George Russell reçut un accueil dithyrambique dans la presse spécialisée. Ce qui n’empêcha pas la compagnie phonographique d’arrêter une série qui ne compta guère que sept volumes dont l’un resta inédit. Les autres chefs de chantier élus avaient été le tromboniste Billy Byers et le pianiste Hal Schaefer. Compositeurs et arrangeurs l’un et l’autre, ils partageaient avec leurs confrères californiens un goût prononcé pour les alliages sonores inusités. Signé du premier, Chinese Water Torture opposait quatre trombones à une trompette et un ténor alors que trois altos, dont celui de Phil Woods, servaient les desseins d’Hal Schaefer dans Dancing in the Dark.

Durant la gestation de « Miles Ahead», Davis avait réussi à persuader Bob Weinstock d’offrir à Gil Evans l’opportunité de signer son premier album personnel sur son label Prestige. Une sorte de marché de dupes car l’homme d’affaires et le musicien ne partageaient pas la même conception du travail : le plus vite et le moins cher possible pour l’un, perfectionnisme pour l’autre, ce qui supposait prendre tout le temps nécessaire pour les retouches sur le vif.

Gil Evans avait choisi comme solistes, Steve Lacy au soprano – maintes répétitions eurent lieu à son domicile – et le tromboniste Jimmy Cleveland qu’il contactait régulièrement pour savoir si les thèmes sélectionnés lui convenaient. Alors qu’il n’affichait aucune prétention en tant qu’instrumentiste, au long de Jambangle, un thème oscillant entre binaire et ternaire incluant des figures de boogie woogie, Gil Evans vient opportunément rappeler qu’il était aussi pianiste.

Complice de Gil lors de la mise sur pied du Birth of the Cool Band, Gerry Mulligan, découragé par l’absence de perspectives new-yorkaises, avait gagné la Californie pour y trouver la célébrité grâce au quartette qu’il y avait monté avec Chet Baker. Une formule transitoire à ses yeux. Au mois de décembre 1954, il invita Bob Brookmeyer et Zoot Sims à rejoindre Jon Eardley, Red Mitchell, Larry Bunker et lui-même sur la scène du Hoover High School Auditorium de San Diego. À la suite de ce concert, revenu à New York, Gerry réalisa qu’une telle réunion de quatre instruments mélodiques, d’une basse et d’une batterie convenait on ne peut mieux à sa musique. Il battit le rappel et, à la fin de l’été 1955, le Gerry Mulligan Sextet était né. Une formation ayant une existence hors des studios qui s’insérait d’autant mieux au sein du mouvement marginal new yorkais que son chef était… arrangeur.

Au mois de septembre 1956, le sextette enregistra Makin’ Whoopee, une chanson célèbre de 1921, montrant ainsi l’enrichissement apporté par cette formule instrumentale lorsque l’on se réfère à l’interprétation gravée en quartette trois ans plus tôt. Au cours de la même séance, l’ensemble servit une version de La plus que lente de Claude Debussy. Un arrangement de Gil Evans qui réussissait à mêler étroitement son style propre à celui de Mulligan, illustrant a posteriori le propos d’André Hodeir contenu dans « Hommes et problèmes du Jazz » : « Un Evans, un Mulligan semblent avoir compris que l’objectif principal de l’arrangeur doit être de respecter la personnalité de chaque exécutant, tout en donnant au groupe une âme unanime. »

Au début de 1957, à l’invitation du Département d’Etat, André Hodeir lui-même se rendit en mission culturelle à New York. Certains de ses albums avaient été envoyés à Savoy Records qui publia aux USA l’un d’entre eux comprenant Evanescence un salut adressé à Gil Evans. Mêlant reprises et compositions originales dont The Alphabet, œuvre majeure que sa durée empêche de reproduire ici, une séance fut organisée à New York. On a Riff, basé sur le blues, ne comprend aucun solo.

Une démarche unanimiste déjà utilisée par Charles Mingus, avec des moyens différents pour un résultat diamétralement opposé. Installé à New York, il avait rejoint en 1953 un ensemble à géométrie variable baptisé « The Composers Workshop » rassemblant Teo Macero, John LaPorta, Teddy Charles et quelques autres avant-gardistes. Sous son égide, fut gravé Gregarian Chant dont, selon Mal Waldron, Mingus exposa clairement le modus operandi : « Quand nous interprétons ce morceau, nous ne nous référerons à aucune grille d’accords, nous traduirons juste des émotions. Suivez-moi seulement, en transcrivant vos états d’esprit et nous bâtirons quelque chose de magnifique (8). »

En l’absence de Mingus, Teo Macero, futur producteur de Miles Davis chez Columbia, et John LaPorta gravèrent T. C.’s Groove qui réhabilitait tout autant l’improvisation collective. Paradoxalement en était absent le dédicataire, Teddy Charles, qui, sur la côte ouest, avait dirigé quelques séances audacieuses en compagnie de Shorty Rogers et Jimmy Giuffre. Revenu à New York dès la fin de 1953, il réunit en studio un tentette afin d’interpréter des partitions signées par Gil Evans, Jimmy Giuffre, George Russell ou lui-même dont celle de Green Blues. Une pièce frisant parfois l’atonalité, mettant en vedettes le compositeur au vibraphone, J. R. Monterose au ténor et le batteur Joe Harris.

Hal McKusick : « Les arrangements de George (Handy) sont les premiers que j’ai entendus ou interprétés dans lesquels transparaissaient aussi nettement les influences de la musique classique moderne et qui aient été tout autant conçus pour swinguer. Ses partitions étaient un vrai défi mais se révélaient d’une grande beauté lorsqu’elles étaient correctement exécutées. Elles comprenaient beaucoup de lignes mélodiques s’opposant entre elles, des harmonies intéressantes et de bons « voicings » (9). » Mettant en lice des musiciens de tout premier plan comme Dave Schildkraut ou Allen Eager, Zonkin’ montrait surtout que George Handy n’avait guère de leçons à recevoir sur le plan du swing. Malheureusement après qu’il eût travaillé sur deux albums destinés à Zoot Sims - dans l’un, ce dernier interprétait en re-recording plusieurs parties de saxophones -, sa carrière tourna court.

Autre individualiste, Gil Mellé, un autodidacte qui n’occupa jamais le moindre poste de «sideman». Interrogé sur ses instrumentistes favoris, il désigna Stan Getz et Lars Gullin en revendiquant comme maîtres à penser Stan Kenton, Monk, les boppers, Debussy et l’école impressionniste française. Pour l’album « Gil’s Guests », Kenny Dorham, Hal McKusick et Don Butterfield vinrent se greffer sur son quartette habituel où Joe Cinderella tenait la guitare, lui-même jouant du baryton. Ils interprétèrent Ghengis, basé sur des motifs de Bela Bartok ; une étonnante réussite.

Troisième français à diriger une séance à New York, Michel Legrand. Son album « I Love Paris » ayant connu un grand succès, en guise de remerciement Columbia accepta de produire un disque de jazz entièrement réalisé selon ses vœux. Les deux hommes ayant sympathisé à Paris, Legrand sollicita pour quatre morceaux la présence de Miles Davis qui, curieux de comparer son style d’écriture avec celui de Gil Evans, accepta. À l’issue de la séance, il se déclara en faveur de ce dernier, ce qui ne l’avait pas empêché de signer une magnifique version du thème de John Lewis, Django ; la seule qu’il ait jamais interprétée. « Ce morceau, Django, est une des plus grandes choses qui aient été écrites depuis longtemps » avait-il confié à Nat Hentoff (10).

Après avoir travaillé à Chicago, Bill Russo, l’un des principaux artisans des recherches conduites par l’orchestre de Stan Kenton, s’était établi dans la Grosse Pomme. Le New York Philharmonie Orchestra y avait interprété sa symphonie « The Titans ». Après avoir arrangé pour Lee Konitz l’album « An Image », Bill Russo proposa sa Fugue for Jazz Orchestra à Johnny Glasel qui dirigeait le BrassTet, un ensemble à l’instrumentation inhabituelle, cinq cuivres, une basse et une batterie. Trompettiste aussi à l’aise dans les orchestres symphoniques que dans des orchestres de jazz, compositeur et arrangeur, Johnny Glasel avait précédemment dirigé The Six, le seul ensemble Dixieland… « cool ». Quelqu’un qui se trouvait toujours où on ne l’attendait pas. Bill Russo composa à la même époque une assez surprenante partition basée sur le Davenport Blues de Bix Beiderbecke. « Cette version n’a rien d’une parodie bien qu’elle soit enjouée » dira-t-il. Une pièce qui sera incluse dans « Something New, Something Blue », un recueil rassemblant des œuvres écrites par Manny Albam, Teo Macero, Teddy Charles et Bill Russo bien sûr. Tous musiciens alors reconnus au contraire de John Carisi.

Ce qu’il avait enregistré pour la collection « RCA Victor Jazz Workshop » resta quelques trente ans dans les placards. Arrangeur du Nonette de Miles Davis, trompettiste, élève de Stefan Wolpe, cet ami de Gil Evans resta -et reste - parfaitement sous-estimé. Selon Gunther Schuller, il fut l’un des premiers à réussir l’intégration du feeling jazz dans des œuvres utilisant les formes développées habituellement dans la musique classique. Composé et arrangé par ses soins pour le Tony Scott Tentette, Walkin’ on the Air met en valeur les mêmes qualités d’écriture qu’il avait montrées dans Israel, l’une des pièces-phares du Birth of the Cool Band. Composition inspirée par une tournée en Extrême-Orient qu’il avait effectuée sous les auspices du Département d’Etat américain, Angkor Wat pourrait bien être un autre chef-d’œuvre. Remarquablement écrite, arrangée et interprétée, cette pièce appartenait à l’album « Into the Hot » patronné par Gil Evans. Alors que « Something New, Something Blue » peut être considéré comme l’ultime manifestation unitaire de l’esprit « workshop », ce recueil en annonçait le délitement en faveur de l’ambivalence qui allait dominer le devenir du jazz : l’orchestre de John Carisi y partageait l’affiche avec le septette de… Cecil Taylor.

Valorisant toutes sortes d’écritures, les ateliers avaient proposé, au cours des années 1950, une issue pour le jazz. En perdant de son unanimisme, en voyant ses apports et audaces se diluer dans le courant du jazz historiquement majoritaire, le travail des « workshops » se marginalisa encore un peu plus. Un échec regretté par André Hodeir comme le laisse entendre la citation placée en exergue de ce texte. Bien sûr, il n’aurait certainement pas apporté sa caution à la grande majorité des pièces regroupées ici. Ce qui n’interdit pas, malgré tout, de partager ses regrets.

Alain TERCINET

© 2013 FRÉMEAUX & ASSOCIÉS – GROUPE FRÉMEAUX COLOMBINI

(1) Josef Woodard, Horace Silver – Feeling the Healing, JazzTimes, février 1998.

(2) Gene Lees, Arranging the Score, Cassell, London & New York, 2000. Deux interprétations du Tentette de Monk sont incluses dans le coffret « The Quintessence » qui lui est consacré. La séance arrangée par Dick Cary fut gravée au mois de juin 1957 à New York sous le titre « Dixieland Goes Modern » pour une label disparu depuis belle lurette ; y participait le trompettiste Johnny Glasel ici présent à la tête de son BrassTet

(3) Michael Gerber, Jazz Jews, Five Leaves Publications, Nottingham, G.B., 2009. Al Cohn ne fit qu’une seule apparition en France les 17 et 18 juillet 1981 à la Grande Parade du Jazz de Nice au sein du « Concord All Stars »…

(4) Bob Rush, Al Cohn - Interview, Cadence vol. 12 n° 11, novembre 1986.

(5) Henri Renaud, Le jazz qu’on appella cool, Cahiers du jazz n° 6, 1962.

(6) Quincy Jones, Notes de pochette du LP « How I Feel about Jazz », ABC Paramount.

(7) André Hodeir, L’improvisation simulée – Sa genèse. Sa fonction dans l’œuvre jazz » Cahiers du Jazz Nlle série n°11, 1997.

(8) Brian Priestley, Mingus - a critical biography, Da Capo, 1982.

(9) Mark Myers, Hal McKusick – Interview, Jazz Wax - internet.

(10) Nat Hentoff, Miles : A Trumpeter in the Midst of a Big Comeback Makes a Very Frank Appraisal of Today’s Jazz Scene, Down Beat, 2 novembre 1955.

EAST COAST JAZZ WORKSHOPS

new york 1954-1961

“During the golden age, now-forgotten sycophants believed that good jazz had to be written before it was performed; it was just the opposite. A half-century later, written jazz would have avoided semi-starvation: most musicians, and almost the entire public, were swearing only by improvisation. Others will perhaps explain the reasons why jazz history, in around 1960, avoided the change that should have been made, why works of jazz remained in drawers, why those which were published remained confidential and why, distributed in homeopathic doses, they were deprived of all influence.”

[André Hodeir, “Improvisation Simulation – Its origins, Its function in a Work of Jazz”, in “The André Hodeir Jazz Reader”, The University of Michigan Press, 2009].

In 1955 the bins in New York’s record-shops saw the arrival of an LP with a particularly austere sleeve: against a white background, a dark grey line-drawing silhouetted three trumpets stood on end, together with a tenor saxophone on its rest. Bistre-coloured lettering announced the title Four Brass One Tenor. No bandleader, just “The Jazz Workshop”, with the whimsical graphics of the word “Jazz” probably designed by Jim Flora.

The man behind the album was Jack Lewis, who used to do A&R for RCA in California (he’d recorded Shorty Rogers’ big band there). Producer Manny Sachs had brought him back east to ask him to think up a new project for the jazz department. The result was a collection christened “The RCA Jazz Workshop”. According to Hal Schaefer, one of the musicians they contacted, to join the Workshop “You had to be a composer, arranger and instrumentalist, all rolled in one.” With this initiative, a record-industry “major” officialised a trend that had been around for a while already.

It would seem that the terms “workshop” and “jazz” were coupled together for the first time at the end of 1953, on the cover of a 10” LP released by Debut Records. It gathered four trombones – J. J. Johnson, Kai Winding, Bennie Green, Willie Dennis – and a rhythm section. The following year, a producer (Charles Mingus, no less) adopted the term and kept it throughout his career as a name for various groups he put together.

At the time, the question which people had been asking for a while was: “What can we play with a clear conscience and still not look like people walking all over history’s boppers?” Since the end of 1953, bop veteran Art Blakey had introduced his Jazz Messengers and among them was Horace Silver: “Well, we were playing bebop. The only difference, when me and Art got together, myself being a person who loved the blues and loved black gospel music, more of that music came into the bebop. It wasn’t just all bebop. It was bebop, yes, but we brought in Doodlin’, The Preacher which was more on the gospel elements into the music, whereas the bebop didn’t have that before.” (1) Referred to as “Hard Bop”, this school won the support of fans because, deep down, it reassured them. The thunder released by Art Blakey – with Horace Silver breaking into hymns – drowned out the little music of those who didn’t feel concerned by the remedies which The Jazz Messengers were prescribing. All the more since many of them – but not all – weren’t part of the Afro-American community. For them, the nonet led by Miles Davis had suggested a much more promising answer to the question of what came after bop.

At a conference held on April 8th 1995 at Washington University in St. Louis, the saxophonist, composer, arranger and writer Bill Kirchner had this to say on the subject: “It [the nonet] recorded only a dozen pieces for Capitol and played in public for a total of two weeks in a nightclub, but its recordings and their influence have been compared to the Louis Armstrong Hot Fives and Sevens, and to other classics by Duke Ellington, Count Basie and Charlie Parker … But the ‘Birth of the Cool’ influence extended far beyond west coast jazz and frequently appeared in all sorts of unexpected places. In the 50’s, east coast composer-arrangers such as Gigi Gryce, Quincy Jones and Benny Golson produced recordings using this approach, as did traditionalist Dick Cary, who used the style in orchestrating a set of Dixieland warhorses. Thelonious Monk, with arranger Hall Overton, used an almost identical ‘Birth of the Cool’ instrumentation for his famed 1959 Town Hall concert. The format was proving to have all sorts of possibilities for creative jazz-writing.” (2)

Convinced that arrangements were the basis for renewing jazz, as in California, a few New York musicians – old hands from the Birth of the Cool Band, sympathisers or recent converts – got busy setting the example. Following the model provided by the group which had gathered around Miles, they formed groups of varying (mostly-medium) size, from sextets to bands with ten or twelve musicians. The instrumentation of these groups rivalled what had become the norm on the west coast: three altos for Hal Schaefer, three trumpets and a tenor for Al Cohn, four trombones for Billy Byers, the accordion of Orlando DiGirolamo with Teo Macero, five brass plus bass and drums (John Glasel’s initiative)…

The movement, which reached its apogee in 1954-1960, was called “subterranean”, jazz-evolution oblige. Whether it came from formations labelled “workshops”, or was performed by a number of similar bands without that label, the music – which had a beautiful complexity – didn’t enjoy true recognition despite the perspectives which could be glimpsed in it. Its diversity, which could even go so far as to be antagonism, bore witness to jazz’ preoccupations at the time. Nor were the ‘shops closed to foreigners, as three Frenchmen with similar preoccupations – Henri Renaud, André Hodeir and Michel Legrand, each as different from the other as they all were from the Americans – had the chance to express themselves in the studios of New York.

As on the west coast, as time went by the N.Y. studios often found themselves occupied by the same instrumentalists who, despite their great qualities, enjoyed hardly any public recognition. There were Osie Johnson and Milt Hinton, respectively on bass and drums, guitarist Barry Galbraith, Hal McKusick, Nick Travis, baritone sax-players Sol Schlinger, Gene Allen, Danny Bank… There was Art Farmer (nobody knows if his eclecticism deserved more praise than the quality of his contributions); there was Zoot Sims, too, about whom Ronnie Scott once said, “When he started playing, he brought even the most blasé of customers back to life with a grin.”

There was such a variety of style and eclecticism among the musicians involved that, if one had to give in and start playing the favourite game of jazz critics, i.e. start putting things into categories, the arrangers, in this case, could be grouped into two families, “neo-classical” and “experimental”, even though all kinds of in-between possibilities were imaginable. The first bunch continued in the spirit of the small groups which were active during the swing era; but since they knew bebop and its advanced column like the backs of their hands, each representative of this group tended to turn it to his own advantage whenever he felt like it. As Al Cohn said about his “Natural Seven”, “We tried on these records to recapture the feeling of the Kansas City Seven – in our own way, of course.”

As for the “experimental”, they were looking to clear the underbrush beyond bop. They did so in their own way, too, even if it meant taking a step in the direction of what they called “serious” music.

According to Kirk Silsbee, “Phil Woods tells me the greatest music he ever heard was in Al Cohn’s living room. Al had all this wonderful knowledge of harmony and composition, and yet there was nothing academic about his playing or his writing. All were organic and musical.” (3) The titles Cohn not Cohen, Haroosh and The Return of the Red Head testify to that. Should we add Boo Wah, taken from a series of recordings which Henri Renaud made in New York for the Swing label? The original sleeve-notes written by Charles Delaunay lead one to believe so. The released version of Boo Wah wasn’t the definitive one, because there wasn’t time to finish the final take, but what with its qualities far outweighing its few weaknesses, Messrs Al Cohn, J. J. Johnson (standing in at the last minute for Brookmeyer, who’d gone on tour), Jerry Hurwitz (alias Jerry Lloyd, a rare trumpeter who soon abandoned music altogether) and Henri Renaud more than deserve a listen.

Taken from “Four Brass, One Tenor”, Cohn not Cohen and Haroosh see Al Cohn taking on four trumpeters – Joe Newman plays the solos, Thad Jones plays the statement of Haroosh –, backed by the incomparable Freddie Green. Incisive in the first piece, waxing lyrical throughout the second, Al Cohn builds “solos that resemble themes, and the development of his improvisations bears witness to the continuity in his creative thought-process, and a logic worthy of Armstrong” (Henri Renaud).

Displaying in turn its own intentions to adopt the “workshop” formula, the Epic label entrusted Al Cohn with an album. On three different occasions he put together, in different ways, a sax section and a rhythm section. For one of them he called in Zoot Sims who, on The Return of the Red Head, plays the first part, and Al Cohn the next, before a dialogue takes shape in 4/4. They met up again four months later and their exchanges would continue for a good thirty years, both onstage and in the studios.

Al Cohn: “I enjoyed that date a lot, a very ‘fun’ record date. Nick Travis, Buddy Jones on bass, Osie Johnson, Galbraith and Zoot – he played alto and I played baritone … We just came and never saw that music before we walked on the studio. It wasn’t difficult. It was all John Benson Brooks. Very talented guy, funny man; also, clever.” (4) Played with warmth and simplicity, rigour and efficiency, Venezuela has qualities identical to those which marked Al Cohn’s scores.

Manny Albam helped him out with the inaugural volume of the RCA Victor Jazz Workshop series, “Four Brass, One Tenor”, and he was credited with producing one of the next. Albam was a baritone saxophonist who abandoned his playing-career in the early Fifties to concentrate on writing. He followed a precise credo: “I cannot divorce myself from tradition, for it’s where we all come from, and it should be a base from which we operate in jazz. If writing is to be JAZZ WRITING, it should fuse the elements particular to its own tradition – the beat, improvisation within a disciplinary frame, and its own unique feeling.”. He also insisted on the necessity of a narrow interdependence between writing and improvisation. For the occasion, Manny put the instruments in pairs: two trumpets, two trombones, two saxes, plus a bass and drums rhythm-section. The duality was most unusual but it still works marvels on Cole Porter’s song Anything Goes, with trumpeters Nick Travis and Jimmy Nottingham playing their respective parts without and with a mute.

Albam made no secret of the influence Duke Ellington had on him, and Duke is an obvious reference throughout “Jazz Greats of Our Time”, a double album which featured his original compositions and arrangements recorded by musicians who were the cream of the crop, some of them based in Los Angeles while others were from New York. Inspired by a character created by humorist James Thurber, Poor Dr. Millmoss opens with a confrontation between two baritone saxophones (Gerry Mulligan and Al Cohn, in that order in the choruses and their 4/4 exchanges). The piece has a festive score which allows each musician to speak in turn, and one of them was another of Henri Renaud’s friends: “… Brookmeyer, he’s an original, a disconcerting musician. His musical culture is vast; he can write atonal music and then recall King Oliver and Louis Armstrong in his scores. He knows Jelly Roll Morton as well as he knows Gil Evans. As a soloist, he has recourse to the long, legato phrases of today’s improvisers and then yields to a way of playing that is much more contrasted and expressionist, manifestly derived from the style of the great ‘classical’ soloists. In fact, the term ‘modern traditionalist’ might have been invented for him.” (5)

Brookmeyer was Gerry Mulligan’s preferred partner for several decades, and played his part in one of Jimmy Giuffre’s most audacious trios; he was also proud of his love for Kansas City jazz (he was born there), but that didn’t stop him putting a knife into the marriage-licence… In fact, he had a fertile ambiguity which turned on the charm for the two pieces Confusion Blues – which could have served as an introduction to his own “Traditionalism Revisited” album – and Darn That Dream, which Kenneth Hagood had recorded in the company of Miles Davis’ Birth of the Cool Band. Was that any accident? Even if it wasn’t, the fact is that ‘Brook’, in turn, summoned a French horn and a tuba to do justice to the disenchanted lyricism which fills this old hit. No trace of pastiche at all.

If Bob Brookmeyer remained on the jazz scene until the beginning of the new century, things worked out differently for a good many others, the lifeblood of these workshops. Among them was the unjustly forgotten Phil Sunkel, a trumpeter and cornet-player who was on call for both Al Cohn and Gil Evans, never mind Mulligan, who hired him to play in his Concert Jazz Band. As an arranger, Sunkel collaborated on the only official album made by his colleague Tony Fruscella, a man of now-legendary status. Salt comes from that one, and it’s a variation on the blues which was composed and superbly arranged by Sunkel, who leads his own Jazz Band on Joe the Architect (another of his tunes, this one dedicated to one of those celestial hobos dear to Jack Kerouac.) Just as forgotten by jazz encyclopaedias is the arranger/bandleader Tom Talbert. In California he’d been leading an orchestra which had Lucky Thompson and Art Pepper in its ranks, amongst others. Maria Schneider, when asked about his arrangement of I’ve Got You Under my Skin, said: “To me, that’s just genius-writing.” Once he got to the east coast, Tom Talbert worked closely with Oscar Pettiford, who was present on Fats Waller’s Bond Street where the orchestral ensembles converse with the piano of George Wallington.

In Washington, Bill Potts signed most of the arrangements played by “The Orchestra”, led by Joe Timer, which accompanied Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie. Potts partnered Lester Young at Olivia Davis’ Patio Lounge, and he persuaded ‘Pres’ to allow him to record them. The result was a series of thrilling albums. Gathered in RCA’s New York studios, the Freddy Merkle Group was actually most of the musicians from “The Orchestra”. White House, composed and arranged by Potts, recreates to some extent the atmosphere of Mulligan’s Tentet, with excellent help from John Payne, Joe Davis, Earl Swope and Al Seibert.

Vinnie Riccitelli had formed the “Westchester Workshop” whose name announced its link with one of the sixty-two boroughs in New York State. It was an octet in the classical format and made only one album, which makes you regret that Riccitelli’s writing-skills didn’t get an airing more often – almost the only trace of him is his instrumental work in the big bands of Dick Meldonian/Sonny Igoe and Lew Anderson. His Carmenooch features the tenor of Carmen Leggio, and doesn’t resist a nod in the direction of Georges Bizet. Another forgotten musician was Joe Holiday, a very interesting tenor-player born in Sicily whose style has Wardell Gray and Stan Getz influences. He wrote the delicate Study in Turquoise which benefits from Ernie Wilkins’ attentions. Wilkins – he was both an arranger and a saxophonist – had built his reputation with the scores he’d concocted for his former employer Count Basie, but also thanks to arrangements for Gillespie, Harry James, Tommy Dorsey and other big bands. The latter were his favourite hunting-grounds but he sometimes spared the time to write for medium-size groups.

While the reputation of Ernie Wilkins hasn’t exactly suffered over the years, there was one other arranger/composer around who has almost never been out of the spotlight: Quincy Jones. A “jet-setter” and showbiz personality, Quincy remains above all a jazzman: “I would prefer not to have this music categorized at all, for it is probably influenced by every original voice in and outside of Jazz, maybe anyone from Blues singer Ray Charles to Ravel,” (6) he wrote in his preface to “How I Feel About Jazz”, the album from which this Evening in Paris is taken. Zoot Sims came down from Washington especially to record the solo which “Q” reserved for him in his tentet. Quincy used the ten-piece format sparingly, and then only for himself: he preferred writing for more substantial ensembles. When he worked for others, however, it was another matter altogether, as shown on this Miss Wise-Key written for Don Elliott, and which contains a remarkable drum part by Osie Johnson. Quincy wrote his score before going off to France to complete his musical education under Nadia Boulanger; France was where he’d originally shown his writing-skills in clandestine sessions for Clifford Brown, during a tour by the Hampton orchestra.

Hampton had been fortunate to have Gigi Gryce playing alto alongside him; Gryce was of the opinion that Tadd Dameron was “one of the greatest, most inventive, most adventurous arrangers of our time.” With a taste for beautiful melody lines, daring harmonies and choruses that gave not a whit for traditional structures, Gigi Gryce intended to fructify the legacy of his maître à penser. He was co-leader of the “Jazz Lab” and from time to time he invited guests to drop in: to record this new version of Nica’s Tempo, one of his most famous compositions, baritone saxophonist Sahib Shihab was assisted by Julius Watkins on French horn and Don Butterfield on tuba. Gryce used the same two instruments for Kerry Dance – an Irish folk-tune from which Charlie Parker often quoted – and gave the piece the sound of Miles’ nonet; Shorty Rogers had done the same thing four years earlier in Los Angeles.

If the legacy of the Birth of the Cool Band found great success at the hands of many arrangers, for the time being its initiator was biding his time in the wilderness. Only a few things had come along to enhance Gil Evans’ career: an aesthetically incomplete session with Charlie Parker and a few scores for various vocalists including Johnny Mathis. Fortunately, the wind changed direction. Before Miles summoned him back, singer Helen Merrill had insisted on Gil’s presence for one of her own albums, and in 1956 Teddy Charles commissioned a score from him. Three months later came Hal McKusick’s turn at the helm of a new volume in the RCA Victor Jazz Workshop series. Instrumentalist/composer McKusick was one of the key musicians in the workshop nebula: his playing, initially influenced by the discourse of Parker and Lee Konitz, showed a rare finesse and musical intelligence, not only with his alto but also when he put a clarinet or flute to his lips. After a learning-curve with a dozen big-bands, in 1954 he set up a piano-less quartet with Barry Galbraith in order to explore the sounds that were possible with an alto (or flute) & guitar combination. The alto/guitar pairing can be heard in the statement of Ballad of Hix Blewitt.

Gil Evans gave two scores to Hal McKusick, among them Blues for Pablo which Miles Davis would also record. Gil’s first edition inspired this observation from André Hodeir: “In the Fifties, jazz composers sought to give certain phrases written for orchestral instruments a little of the flexibility and rhythmical freedom acquired by improvisers. And so in the first version of ‘Blues for Pablo’ (1956), Gil Evans endeavours to model his unison writing in the image of the chorus-phrase. The period which begins like a theme-statement dips down from the third bar to evolve into a deft suggestion of double time.” (7)

With his book “The Lydian Chromatic Concept Of Tonal Organization for Improvisation” published in 1953, George Russell dug deeper into his research concerning the possible union of jazz and modal music. He was working behind the counter at a drugstore – at least it was a living – when Hal McKusick bumped into him and asked if he might be interested in writing a piece for him… Russell composed Miss Clara, a particularly complex piece of music with an orchestral interlude written in 6/4.

After some insistence from Hal McKusick, George Russell found himself in charge of a Jazz Workshop, and he put together a sextet which included a pianist he’d just discovered: Bill Evans. The solo which Evans plays on Ye Hypocrit, Ye Belzebuth, and his accompaniment – quasi Monk-ish – throughout the Ballad of Hix Blewitt, go a long way towards explaining the fascination he held for Russell, whose RCA Victor Jazz Workshop volume was showered in praise by the critics. That, however, didn’t stop the record-company, who brought the series to a halt after only seven albums, one of which remains unreleased. The other foremen on these building-sites were trombonist Billy Byers and pianist Hal Schaefer. Both were composers, both were arrangers, and with their colleagues they shared a pronounced taste for unusual sound-alloys. Chinese Water Torture was written by Byers and opposes four trombones with a trumpet and tenor; three altos – one of them Phil Woods – carry out the plans of Hal Schaefer on Dancing in the Dark.

While “Miles Ahead” was in gestation, Miles Davis had succeeded in persuading Bob Weinstock at Prestige to give Gil Evans the opportunity to do an album, the first with his own name on the sleeve. It was a kind of fools’ bargain in that the businessman and the musician had different work-concepts: the quicker and the cheaper the better, for the first; the name of the game for the second was perfectionism, a concept which meant taking all the time that was needed to make changes on the fly. When it came to choosing his soloists, Gil Evans opted for Steve Lacy on soprano – many rehearsals took place at his home – and trombonist Jimmy Cleveland, whom he contacted regularly just to see if he was OK with the themes he’d written for him. Another thing: although Gil Evans had no pretensions as an instrumentalist, he appears throughout Jambangle, a tune which oscillates between binary and ternary sections and includes boogie woogie figures, to fortunately remind everyone that he also played piano.

Gerry Mulligan had been one of Gil Evans’ accomplices in setting up The Birth of the Cool Band and, discouraged by the absence of any promising perspectives in New York, he’d gone to California to find fame with the quartet he founded with Chet Baker, a format which he saw as a temporary one. In December 1954 he invited Bob Brookmeyer and Zoot Sims to join Jon Eardley, Red Mitchell, Larry Bunker and his good self on the stage of the Hoover High School Auditorium in San Diego. Back in New York after the gig, Gerry realised that the ‘four melody-instruments plus bass and drums’ format was ideally suited to his music; he rang everyone up and, at the end of the summer in 1955, the Gerry Mulligan Sextet was born. It had advantages: it could exist outside a studio, and it was all the more capable of slipping itself into this marginal New York movement since its leader was… an arranger.

In September 1956 they recorded Makin’ Whoopee, a famous song from 1921, and showed how much richer it was when played by the sextet’s instrumental format, compared with the quartet performance recorded three years earlier. During the same session, the sextet served up a version of Claude Debussy’s La plus que lente. Gil Evans’ arrangement succeeds in closely mingling his own style with that of Mulligan, and it is a later illustration of André Hodeir’s observations in “Hommes et problèmes du Jazz”: “An Evans, a Mulligan, seem to have understood that the arranger’s principal objective must be to respect the personality of each performer whilst giving the group a unanimous soul.”

Hodeir went to New York himself in 1957, invited by the State Department on a cultural mission. Some of his albums had been sent to Savoy Records, who released the one which had the tune Evanescence, a salute to Gil Evans. A session was consequently organized in New York, mingling new versions of some pieces with original compositions like The Alphabet, a major work whose duration prevents its inclusion here. On a Riff, based on the blues, has no solo in it.

Charles Mingus had already used that minimalist approach with different means, and the results were the complete opposite. Settled in New York, Mingus had joined a group of varying size in 1953; called “The Composers Workshop”, it contained Teo Macero, John LaPorta, Teddy Charles and a few other avant-gardists. Under the aegis of Mingus they recorded Gregarian Chant in which, according to Mal Waldron, Mingus gave a clear statement as to his modus operandi: “When we play this tune, we’re not going to play any changes, we’re just going to play moods. Just follow me, and put your moods in, and we’ll build something beautiful.” (8)

With Mingus absent, Teo Macero (Miles Davis’ future producer at Columbia) and John LaPorta recorded T. C.’s Groove, which did just as much to rehabilitate collective improvisation. Paradoxically, the vibraphonist/arranger to whom it was dedicated, Teddy Charles, was also absent; out on the west coast, he’d led a few daring sessions in the company of Shorty Rogers and Jimmy Giuffre. When he went back to New York at the end of 1953, he took a tentet into the studio to record scores written by Gil Evans, Jimmy Giuffre, George Russell or himself, including this Green Blues, a piece sometimes skirting the atonal, which features the composer’s vibraphone, J. R. Monterose on tenor, and drummer Joe Harris.

Hal McKusick: “George [Handy]’s arrangements were the first I had heard or played that had heavy modern classical influences and were created to swing, too. His pieces were a challenge and beautiful when played correctly. There were many flowing lines against lines, and interesting harmonies and good voicing.” (9). The musicians doing the jousting were first-rate, like Dave Schildkraut or Allen Eager, and Zonkin’, especially, showed that nobody could teach George Handy much about swing. After working on two albums for Zoot Sims – on one of them, Zoot overdubbed four alto saxophone parts – George’s self-destructive behaviour sadly cut short his career.

Another individualist was Gil Mellé, a self-taught baritone-player who never had a job as a sideman. When asked who his favourite musicians were, he came up with a list including Stan Getz and Lars Gullin, and said his mentors were Stan Kenton, Monk, the boppers, Debussy, and the French Impressionist School… On the album “Gil’s Guests”, Kenny Dorham, Hal McKusick and Don Butterfield were grafted onto his usual quartet with guitarist Joe Cinderella and Mellé himself on baritone. They played Ghengis, based on Bela Bartok’s motifs, an astonishing achievement.

The third Frenchman to lead a session in New York was Michel Legrand. His album “I Love Paris” had been very successful and by way of a thank-you, Columbia agreed to produce a jazz album that would be all his own choosing. Legrand and Miles Davis had become friends in Paris, and Legrand asked for the trumpeter to play on four pieces. Miles, who was curious to compare Legrand’s style of writing with that of Gil Evans, accepted. When the session was over, he came out in favour of the latter, but it hadn’t stopped him from playing a magnificent version of the John Lewis tune Django, the only one he ever did. As Miles said to Nat Hentoff, “That piece ‘Django’ is one of the greatest things written in a long time.” (10)

Bill Russo was one of the main artisans of the research conducted by the Stan Kenton Orchestra, and after working out of Chicago he moved to the Big Apple, where the New York Philharmonic Orchestra had performed his symphony “The Titans”. After arranging the album “An Image” for Lee Konitz, Bill Russo proposed his Fugue for Jazz Orchestra to Johnny Glasel, who was fronting the BrassTet, a group with an unusual line-up of five brass, bass and drums. A trumpeter equally at home with symphony orchestras and those of the jazz kind, and who doubled as a composer/arranger, Johnny Glasel had previously had a group called The Six, the only “cool school” Dixieland band. In other words, Glasel was always where he was least expected. At around the same time, Bill Russo composed a rather surprising score based on Davenport Blues by Bix Beiderbecke. “This version is not at all a parody, although it is playful,” he said. That piece would form part of “Something New, Something Blue”, an anthology of works written by Manny Albam, Teo Macero, Teddy Charles (and Bill Russo of course). All of them were recognized musicians, except John Carisi.

The album which Carisi recorded for the RCA Victor Jazz Workshop series stayed in a drawer for something like thirty years. Carisi wrote arrangements for Miles Davis’ nonet, had been a pupil of Stefan Wolpe, and was a friend of Gil Evans, but he remained – and remains – grossly underestimated. According to Gunther Schuller, he was one of the first to succeed in making the jazz ‘feel’ an integral part of works which used forms usually found in classical music. Carisi composed and arranged Walkin’ on the Air for the Tony Scott Tentette, and it features the same writing-skills which he had demonstrated in Israel, one of the emblematic pieces from the Birth of the Cool Band. Angkor Wat was a composition inspired by a State Department tour of the Far East, and could well be another masterpiece; remarkably written, arranged and performed, the piece comes from the album “Into the Hot” supervised by Gil Evans. Whereas “Something New, Something Blue” might be considered the final unitary manifestation of the “workshop”-spirit, “Into the Hot” heralded its dissolution in favour of the ambivalence which would dominate the evolution of jazz: John Carisi’s orchestra shared the billing on the album with the septet led by… Cecil Taylor.

By giving validity to all kinds of jazz-writing, these workshops of the Fifties had suggested a way for jazz to move on. When it lost its universal consensus, and saw the audacity of its contributions diluted into the mainstream which, historically, constituted most of jazz, the workshops were marginalised even further. André Hodeir regretted their failure to persist, as shown by his observations in “Improvisation Simulation”, which introduce these notes. Of course, he certainly wouldn’t have endorsed most of the pieces gathered here but, this notwithstanding, one can still share his regrets.

Alain TERCINET

Adapted into English By Martin DAVIES

© 2013 FRÉMEAUX & ASSOCIÉS – GROUPE FRÉMEAUX COLOMBINI

(1) Josef Woodard, “Horace Silver – Feeling the Healing”, JazzTimes, February 1998.

(2) Gene Lees, “Arranging the Score”, Cassell, London & New York, 2000. Two performances by Monk’s tentet are included in the “Quintessence” set devoted to his work. The session, arranged by Dick Cary, was recorded in New York in June 1957 (under the title “Dixieland Goes Modern”) for a label that has long since disappeared. One participant was trumpeter Johnny Glasel, who appears here leading his own BrassTet.

(3) Michael Gerber, “Jazz Jews”, Five Leaves Publications, Nottingham, G.B., 2009. Al Cohn made only one appearance in France on July 17th/18th at the “Grande Parade du Jazz” in Nice, playing with The Concord All Stars.

(4) Bob Rush, “Al Cohn – Interview”, Cadence vol. 12 N° 11, November 1986.

(5) Henri Renaud, “Le jazz qu’on appelle cool”, Cahiers du jazz N° 6, 1962.

(6) Quincy Jones, in his sleeve-notes for the LP “How I Feel about Jazz”, ABC Paramount.

(7) André Hodeir, “Improvisation Simulation – Its origins, Its function in a Work of Jazz”, originally published in Cahiers du Jazz, Nlle série N°11, 1997.

(8) Brian Priestley, “Mingus - A Critical Biography”, Da Capo, 1982.

(9) Mark Myers, “Hal McKusick – Interview”, Jazz Wax (internet).

(10) Nat Hentoff, “Miles: A Trumpeter in the Midst of a Big Comeback Makes a Very Frank Appraisal of Today’s Jazz Scene”, Down Beat, November 2nd 1955.

CD 1

1. FOUR BRASS, ONE TENOR : COHN, NOT COHEN

mx F2JB3736, RCA-Victor LPM 1161 2’48

2. FOUR BRASS, ONE TENOR : HAROOSH

mx F2JB3740, RCA Victor LPM 1161 4’03

3. THE SAX SECTION : THE RETURN OF THE RED HEA

mx CO56270, Epic LN3278 3’29

4. MANNY ALBAM : POOR DR. MILLMOSS

mx 102151, Coral CRL57173 5’34

5. MANNY ALBAM : ANYTHING GOES

mx F2JB8567, RCA Victor LPM1211 3’42

6. BOB BROOKMEYER : CONFUSION BLUES

mx G4PB7366, Vik LX 1071 4’23

7. BOB BROOKMEYER : DARN THAT DREAM

mx 3376, Atlantic LP 1320 4’27

8. JOHN BENSON BROOKS : VENEZUELA

mx G4PB8105, Vik LX1083 4’36

9. HENRI RENAUD’S U. S. STARS : BOO WAH

Unnumbered, Swing M. 33. 327 4’53

10. TONY FRUSCELLA : SALT

mx 1467, Atlantic LP1220 4’37

11. PHIL SUNKEL’S JAZZ BAND : JOE, THE ARCHITECT

Unnumbered, ABC Paramount 136 3’03

12. JOE HOLIDAY AND HIS BAND : STUDY IN TURQUOISE

Unnumbered, Decca DL8487 3’00

13. THE WESTCHESTER WORKSHOP : CARMENOOCH

Unnumbered, RKO-Unique LP103 4’06

14. TOM TALBERT : BOND STREET

mx 2095, Atlantic LP 1250 2’38

15. THE FREDDY MERKLE GROUP : WHITE HOUSE

mx H4JB4010, Vik LX1114 3’41

16. DON ELLIOTT OCTET : MISS WISE-KEY

Unnumbered, ABC Paramount 106 2’28

17. QUINCY JONES : EVENING IN PARIS

mx 5332, ABC Paramount ABC 149 4’06

18. THE ORCHESTRA OF GIGI GRYCE : KERRY DANCE

mx 123, Signal S1201 3’00

19. DONALD BYRD - GIGI GRYCE JAZZ LAB : NICA’S TEMPO

mx CO57304, Columbia CL 998 5’29

1. FOUR BRASS, ONE TENOR : Joe Newman, Bart Valve (Thad Jones), Bernie Glow (tp) ; Nick Travis (tp, v-tb) ; Al Cohn (ts, arr), Dick Katz (p), Freddie Green (g) ; Buddy Jones (b) ; Osie Johnson (dm) - NYC, may 14, 1955

2. FOUR BRASS, ONE TENOR : Joe Newman, Bart Valve (Thad Jones), Phil Sunkel (tp) ; Nick Travis (tp, v-tb) ; Al Cohn (ts, arr), Dick Katz (p), Freddie Green (g) ; Buddy Jones (b) ; Osie Johnson (dm) - NYC, may 16, 1955

3. THE SAX SECTION : Zoot Sims, Al Cohn, Eddie Wasserman (ts) ; Sol Schlinger (bs) ; Hank Jones (p) ; Milt Hinton (b) ; Don Lamond (dm) ; Al Cohn (arr) – NYC, june 28, 1956

4. MANNY ALBAM : Nick Travis, Art Farmer (tp) ; Bob Brookmeyer (v-tb) ; Phil Woods (as) ; Zoot Sims (ts) ; Al Cohn (ts, bs) ; Gerry Mulligan (bs) ; Hank Jones (p) ; Milt Hinton (b) ; Osie Johnson (dm), Manny Albam (arr) - NYC, april 3, 1957

5. MANNY ALBAM : Nick Travis, Jimmy Nottingham (tp) ; Billy Byers (tb) ; Bob Brookmeyer (v-tb) ; Al Cohn (ts) ; Sol Schlinger (bs) ; Milt Hinton (b) ; Osie Johnson (dm) ; Manny Albam (arr) – NYC, december 24, 1955

6. BOB BROOKMEYER : Nick Travis (tp) ; Bob Brookmeyer (v-tb, arr) ; Gene Quill (as) ; Al Cohn (ts) ; Sol Schlinger (bs) ; Hank Jones (p) ; Milt Hinton (b) ; Osie Johnson (dm) – NYC, october 15, 1956

7. BOB BROOKMEYER : Irving « Marky » Markovitz, Ray Copeland (tp) ; Bob Brookmeyer (v-tb, p, arr) ; John Barrows (frh) ; Frank Rehak (tb) ; Bill Barber (tuba) ; Gene Quill (as) ; Gene Allen (bs) ; George Duvivier (b) ; Charlie Persip (dm) – NYC, september 13, 1959

8. JOHN BENSON BROOKS ENSEMBLE : Nick Travis (tp) ; Zoot Sims (as) ; Al Cohn (bs) ; John Benson Brooks (p, arr) ; Barry Galbraith (g) ; Buddy Jones (b) ; Osie Johnson (dm) – NYC, november 1, 1956

9. HENRI RENAUD’S U. S. STARS : Jerry Hurwitz (tp) ; Jay Jay Johnson (tb) ; Al Cohn (ts, arr) ; Gigi Gryce (bs) ; Henri Renaud (p) ; Curley Russell (b) ; Walter Bolden (dm) – NYC, february 28, 1954

10. TONY FRUSCELLA : Tony Fruscella (tp) ; Chauncey Welsch (tb) ; Allen Eager (ts) ; Danny Bank (bs) ; Bill Triglia (p) ; Bill Anthony (b) ; Junior Bradley (dm) ; Phil Sunkel (arr) – NYC, march 1955

11. PHIL SUNKEL’S JAZZ BAND : Phil Sunkel (tp, arr) ; Al Stewart, Siggy Shatz (tp) ; Gene Hessler (tb) ; Dick Meldonian (as) ; Buddy Arnold (ts) ; Gene Allen (bs) ; George Syran (p) ; Bob Petersen (b) ; Harold Granowsky (dm) - NYC, may/june 1956

12. JOE HOLIDAY AND HIS BAND : Joe Newman, Thad Jones (tp) ; Eddie Bert (tb) ; Joe Holiday (ts) ; Cecil Payne (bs) ; Duke Jordan (p) ; Addison Farmer (b) ; Art Taylor (dm) ; Ernie Wilkins (arr) – NYC, february 13, 1957

13. THE WESTCHESTER WORKSHOP : Joe Shepley (tp) ; Eddie Bert (tb) ; Vinnie Riccitelli (as, arr) ; Carmen Leggio (ts) ; Gene Allen (bs) ; Dolph Castellano (p) ; Eddy Tone (b) ; Joe Venuto (dm) - NYC, 1956

14. TOM TALBERT : Joe Wilder, Nick Travis (tp) ; Jimmy Cleveland, Eddie Bert (tb) ; Aaron Sachs (cl) ; George Wallington (p) ; Oscar Pettiford (b) ; Osie Johnson (dm) ; Tom Talbert (arr) – NYC, august 28, 1956

15. THE FREDDY MERKLE GROUP : John Payne, Joe Bovello, Hal Posey (tp) ; Earl Swope, Rob Swope (tb) ; Al Seibert, Ted Efantis (ts) ; Joe Davis (bs) ; Bill Potts (p, arr) ; John Beal (b) ; Freddy Merkle (dm) - NYC, may 10, 1957

16. DON ELLIOTT OCTET : Don Elliott (mellophone, vib) ; Herbie Mann (fl, ts) ; Sol Schlinger (bs) ; Joe Puma (g) ; Vinnie Burke (b) ; Osie Johnson (dm) ; Quincy Jones (arr) – NYC, june 30, 1956

17. QUINCY JONES : Art Farmer (tp) ; Jimmy Cleveland (tb) ; Gene Quill (as) ; Zoot Sims (ts) ; Jack Nimitz (fl, bs) ; Hank Jones (p) ; Brother Soul aka Milt Jackson (vib) ; Charles Mingus (b) ; Charlie Persip (dm) ; Quincy Jones (arr, cond) – NYC, september 14, 1956

18. THE ORCHESTRA OF GIGI GRYCE : Art Farmer (tp) ; Jimmy Cleveland (tb) ; Gunther Schuller (frh) ; Bill Barber (tuba) ; Gigi Gryce (as, arr) ; Danny Bank (bs) ; Horace Silver (p) ; Oscar Pettiford (b) ; Kenny Clarke (dm) – NYC, october 22, 1955

19. DONALD BYRD - GIGI GRYCE JAZZ LAB : Donald Byrd (tp) ; Jimmy Cleveland (tb) ; Julius Watkins (frh) ; Don Butterfield (tuba) : Gigi Gryce (as, arr) ; Sahib Shihab (bs) ; Wadde Legge (p) ; Wendell Marshall (b) ; Art Taylor (dm) - NYC, march 13, 1957

CD 2

1. HAL McKUSICK JAZZ WORKSHOP : BLUES FOR PABLO

mx G2JB3404, RCA Victor LPM1366 4’52

2. HAL McKUSICK JAZZ WORKSHOP : MISS CLARA

mx G2JB3425, RCA Victor LPM1366 4’05

3. GEORGE RUSSELL & HIS SMALLTET : BALLAD OF HIX BLIX

mx G2JB9793, RCA-Victor LPM 1372 3’17

4. GEORGE RUSSELL & HIS SMALLTET : YE HYPOCRITE, YE BELZEBUTH

mx G2JB9793, RCA-Victor LPM 1372 3’51

5. GIL EVANS & TEN : JAMBANGLE

mx 1356, Prestige LP 7120 5’00

6. GERRY MULLIGAN SEXTET : LA PLUS QUE LENTE

mx 14179-2, Mercury MG20453 3’31

7. GERRY MULLIGAN SEXTET : MAKIN’ WHOOPEE

mx 14181-2, Mercury MG20453 4’08

8. ANDRÉ HODEIR : ON A RIFF

mx SAH6984, Savoy MG12104 2’55

9. THE TEDDY CHARLES TENTET : GREEN BLUES

mx 1813, Atlantic LP1229 4’09

10. JAZZ COMPOSERS WORKSHOP / TEO MACERO : T. C.’S GROOVE

mx CO54052, Columbia CL 842 3’45

11. CHARLES MINGUS SEXTET : GREGARIAN CHANT

mx SCM6915, Savoy MG 15050 2’49

12. GIL MELLÉ : GHENGIS

mx 968, Prestige PRLP 7063 3’46

13. BILLY BYERS : CHINESE WATER TORTURE

mx F2JB8348, RCA Victor LPM-1269 3’44

14. HAL SCHAEFER : DANCING IN THE DARK

mx F2JB8083, RCA Victor LPM-1199 2’18

15. GEORGE HANDY : ZONKIN’

mx E4LB4951, « X » LXA1004 4’06

16. TONY SCOTT TENTETTE : WALKIN’ ON THE AIR

mx G2JB5907, RCA Victor EPA 942 2’58

17. MICHEL LEGRAND : DJANGO

mx CO61070, Columbia CL 1250 4’12

18. THE JOHN GLASEL BRASSTET : FUGUE FOR JAZZ ORCHESTRA

Unumbered, Jazz Unlimited LP 1002 2’22