- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

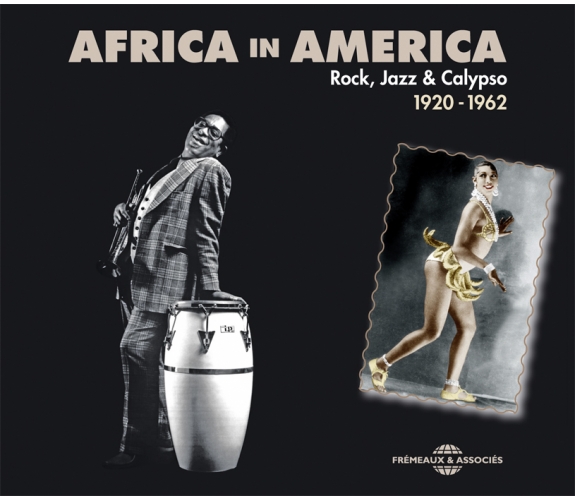

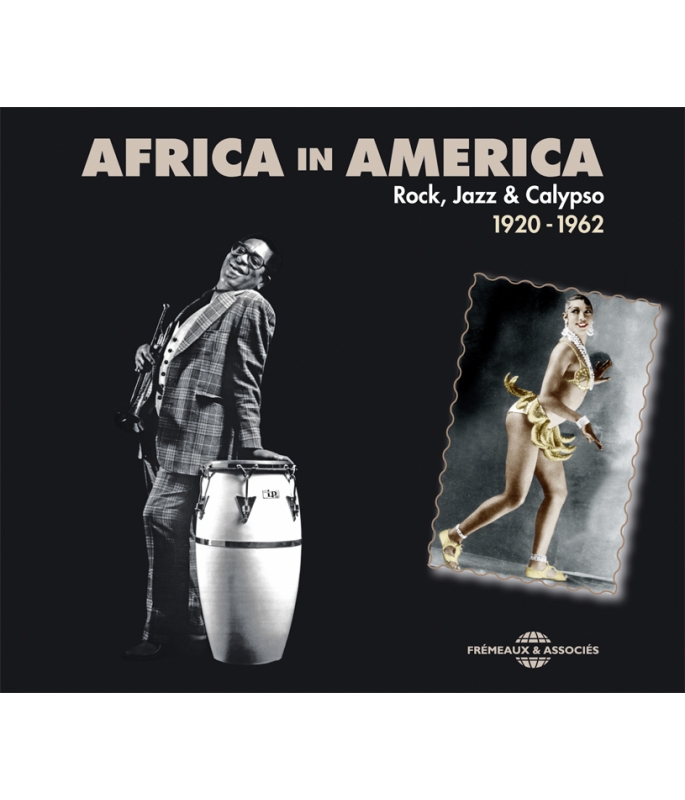

ROCK JAZZ & CALYPSO 1920 - 1962

Ref.: FA5397

EAN : 3561302539720

Artistic Direction : BRUNO BLUM

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Total duration of the pack : 3 hours 46 minutes

Nbre. CD : 3

ROCK JAZZ & CALYPSO 1920 - 1962

ROCK JAZZ & CALYPSO 1920 - 1962

The lushness of the Tropics, scantily-clad bodies, tribal aesthetics and syncopated rhythms… from the famous loincloth worn by Josephine Baker to Elizabeth Taylor’s performance as Cleopatra, Africa has always had a place of choice in the popular imagery of the 20th century. Whether as roots giving unity to separate black identities, the cradle of humanity, or the reflection of original purity, Africa - real, supposed or imaginary - has influenced most of the music, dance-forms and graphic arts of the last hundred years. With detailed comments from Bruno Blum, these splendid titles have been placed in the historic context of the Civil Rights struggle and the independence of the West Indies and the dark continent. Patrick FRÉMEAUX

ANTHOLOGIE 1918-1944

BLUES, JAZZ, RHYTHM & BLUES, CALYPSO (1926-1961)

THE STORY OF THE NEW ORLEANS JAZZ, BLUES, ZYDECO &...

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

10

-

2Greetings to fellow Citizens of AfricaMarcus GarveyMarcus Garvey00:00:271920

-

3SoudanArt's Hischman's London FiveI. Pollack00:02:351920

-

4Sounds of AfricaEubie BlakeEubie Blake00:03:101921

-

5Zulu's ballKing Oliver's Creole Jazz BandKing Oliver00:02:311923

-

6African bluesSam ManningSam Manning00:02:561924

-

7The King of the ZulusLouis ArmstrongLil Hardin00:03:221926

-

8East St. Louis Toodle-oo (version 2)Duke ElingtonDuke Ellington00:03:011927

-

9Egyptian EllaTed LewisWalter Doyle00:03:191931

-

10Shakin' the AfricanDon RedmanHarold Koehler00:02:511931

-

11Jungle FeverThe Mills BrothersDietz Howard00:03:131934

-

12African love callWilmoth HoudiniFrederick Wilmoth Hendricks00:02:551934

-

13Hojoe African war songThe LionRafael De Leon00:02:481938

-

14Jungle drumsSidney BechetArthur Singleton00:02:301938

-

15MbubeSalomon LindaLinda Salomon00:02:451939

-

16You've got me Woodoo'dLouis ArmstrongE. Lawrence00:02:591939

-

17I'm a PilgrimThe Golden Gate Jubilee QuartetTraditionnel00:03:131939

-

18African JiveSlim and SlamHarry D. Squires00:02:491941

-

19Menelik the Lion of JudaRex Stewart00:03:211941

-

20Congo bluesRed Norvo00:04:011941

-

21Night in TunisiaDizzy Gillespie00:03:091946

-

22Signifyin' MonkeyThe Big Three Trio00:02:551946

-

23Kumina BailoKumina congregation00:02:291953

-

24John Canoe MusicJohn Canoe Group00:01:481953

-

25Pukkumina CymbalPukkumina congregation00:07:571953

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1A night in TunisiaCharlie Parker/Miles Davis00:03:051946

-

2The Jungle KingCab Calloway00:03:191947

-

3Bongo BoogieAnnisteen AlenJ. Nix00:02:401947

-

4Goombay DrumBlind BlakeAlice Sims00:02:491952

-

5Mardi Gras in New OrleansFats DominoHenry Roeland Byrd00:02:211952

-

6Jock O MoSugar Boy CrawfordJames Crawford00:02:311953

-

7Stranded in the JungleThe JayhawksE. Smith00:02:521956

-

8EthiopiaLord LebbyWilliams00:03:021955

-

9Birth of GhanaLord KitchenerAldwyn Roberts00:02:511955

-

10RookombeyLloyd Prince ThomasC. Irving00:03:051956

-

11Voodoo WomanBill FlemingWilliam La Motta00:02:231956

-

12Obeah ManAlwyn RichardsAlwyn Richards00:02:231956

-

13New OrleansDuke ElingtonBilly Strayhorn00:02:301956

-

14Hey Buddy BoldenDuke ElingtonBilly Strayhorn00:04:531956

-

15Afro bluesMango SantamariaMongo Santamaria00:03:571959

-

16Congo SquareEllington DukeBilly Strayhorn00:05:281956

-

17Dial AfricaWilbur Harden/John ColtraneHarden Wilbur00:08:421958

-

18Comments on African DrumsArt Blakey00:01:571957

-

19The SacrificeArt Blakey00:05:141957

-

20La Savane Balade CreoleEugene List00:06:361957

-

21Fleurette AfricaineDuke Elington/Charles Mingus/Max RoachDuke Ellington00:03:361962

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Stranded in the JungleThe CadetsSmith Ernestine00:03:071956

-

2Ubangi StompWarren SmithCharles Underwood00:02:011956

-

3Two for TimbuktuSonny Stitt00:03:231959

-

4Kucheza bluesRandy Weston00:08:071960

-

5Signifyin' MonkeyOscar Brown Jr00:04:031960

-

6The Lion Sleeps TonightThe TakensSalomon Ntsele00:02:421961

-

7La IkbeyAhmed Abdul Malik00:05:521961

-

8AfriqueArt Blakey00:06:581961

-

9Ayiko AyikoArt BlakeySalomon G. Llori00:07:131962

-

10Moose the MoocheCount Ossie00:09:101962

-

11AfricaJohn Coltrane00:16:301961

-

12Garvey's GhostMax Roach00:07:521961

Africa in America FA5397

AFRICA IN AMERICA

Rock, Jazz & Calypso

1920-1962

Jungle luxuriante, corps dénudés, esthétique tribale, rythmes syncopés… du fameux pagne de Joséphine Baker à l’interprétation de Cléopâtre d’Elizabeth Taylor, l’Afrique a toujours tenu une place de choix dans l’imagerie populaire occidentale au XXe siècle. Racine fédératrice des identités noires, berceau de l’humanité ou reflet de la pureté originelle, l’Afrique, réelle, supposée ou imaginaire a influencé la majeure partie des musiques, danses et arts graphiques du XXe siècle. Commentés par Bruno Blum, ces titres splendides sont replacés dans le contexte historique de la lutte pour les droits civiques, des indépendances des Caraïbes et du continent noir.

Patrick Frémeaux

The lushness of the Tropics, scantily-clad bodies, tribal aesthetics and syncopated rhythms… from the famous loin-cloth worn by Josephine Baker to Elizabeth Taylor’s performance as Cleopatra, Africa has always had a place of choice in the popular imagery of the 20th century. Whether as roots giving unity to separate black identities, the cradle of humanity, or the reflection of original purity, Africa - real, supposed or imaginary - has influenced most of the music, dance-forms and graphic arts of the last hundred years. With detailed comments from Bruno Blum, these splendid titles have been placed in the historic context of the Civil Rights struggle and the independence of the West Indies and the dark continent.

Patrick Frémeaux

En France, la loi du 21 mai 2001 dite «?loi Taubira?» sur l’esclavage, dispose :

Article 2

Les programmes scolaires et les programmes de recherche en histoire et en sciences humaines accorderont à la traite négrière et à l’esclavage la place conséquente qu’ils méritent. La coopération qui permettra de mettre en articulation les archives écrites disponibles en Europe avec les sources orales et les connaissances archéologiques accumulées en Afrique, dans les Amériques, aux Caraïbes et dans tous les autres territoires ayant connu l’esclavage sera encouragée et favorisée1.

L’Afrique vue par les Américains

L’oppression des Afro-américains, Caribéens inclus, a été massive des années 1920 aux années 1960. Jusqu’aux années 1940 au moins aux États-Unis, les Noirs ont été représentés au théâtre par des black face minstrels, des ménestrels blancs grimés en noir qui les tournaient en ridicule (le personnage de Jim Crow créé par Thomas «?Daddy?» Rice vers 1828). Très populaires, ces spectacles de ménestrels avaient fini par être repris par des Afro-américains qui en reproduisaient eux-mêmes le contenu raciste — condition pour accéder à une scène professionnelle. Une cruelle discrimination était souvent endurée à différents degrés par d’autres minorités, dont les Afro-caribéens, les Indiens d’Amérique, les Inuites, les Juifs (les Juifs noirs souffrant eux-mêmes de racisme au sein de la communauté juive), les catholiques irlandais et cajuns, les Mexicains et autres hispanophones, les Chinois, les Indiens, et d’autres.

Mais les plus méprisés étaient sans conteste les lointains Africains, considérés être des primitifs sans foi ni loi, des barbares païens sans civilisation ni culture, sans écriture ni histoire — voire des cannibales, un stéréotype chanté ici au second degré (?) dans Stranded in the Jungle par les Jayhawks, les Cadets et bientôt par les New York Dolls.

Le barbare, c’est d’abord l’homme qui croit à la barbarie.

Claude Lévi-Strauss,

Race et histoire, 1952 2

On exhiba le Pygmée Ota Benga (suicidé en 1916) dans des zoos américains, des Kanaks à Paris jusqu’en 1931 et des Africains à Bruxelles jusqu’en 1958. Dans cet impitoyable contexte d’exotisme, de paternalisme, d’ignorance, de racisme, d’expansion coloniale, comment les Africains ont-ils été évoqués dans la musique populaire américaine ? Et comment étaient-ils vus par leurs descendants, leurs cousins Afro-américains ?

Nous avons une très belle histoire, et nous allons en créer une autre qui dans le futur étonnera le monde.

Marcus Garvey, vers 1920.

Nous retraçons ici la façon dont ce regard musical sur l’Afrique a évolué au cours du XXe siècle, de l’horreur des lois ségrégationnistes «?Jim Crow?» au triomphe de la lutte pour les lois civiques. Et de l’apogée des empires coloniaux aux indépendances des Caraïbes et de l’Afrique (saluée ici par le Trinidadien Lord Kitchener sur Birth of Ghana). Retrouver l’estime de soi était la première bataille à gagner. Les negro spirituals puis le gospel, le jazz, le rhythm and blues, le calypso et le rock ont eu un rôle précurseur et moteur dans la diffusion et la reconnaissance des cultures afro-américaine, caribéenne et africaine - et par conséquence, sur l’amélioration du sort des intéressés. Le principe des droits égaux pour les Afro-américains ne s’imposera que dans les années 1960. Mais il faudra encore un demi-siècle avant l’élection historique en 2008 d’un Président des États-Unis métis, l’amateur de jazz Barack Hussein Obama II (né le 4 août 1961).

Un bon compromis, une bonne loi, c’est comme une bonne phrase?; Ou un bon morceau de musi-que. Tout le monde peut le reconnaître.

Barack Obama

World Music

C’est à partir des années 1950 que la musique populaire a commencé à prendre une réelle dimension de mondialité, un fait ethnologique majeur. Tournées internationales de l’Égyptienne Oum Kalsoum ou calypso et mento jamaïcain de Harry Belafonte3, puis krio de Sierra Leone, jazz latin, son, rumba et mambo4 cubains, puis rumba congolaise et bientôt salsa new-yorkaise, bossa nova5 brésilienne de João Gilberto6, ostensibles influences cubaines et africaines sur le jazz (à écouter ici), blues des Rolling Stones ou soul des Animals, succès de la Sud-Africaine Miriam Makeba, influence de l’Indien Ravi Shankar sur John Coltrane ou George Harrison, ska et bientôt reggae de Bob Marley7 reflétaient la société multiculturelle. Ils annonçaient le courant «?world music» des années 1980.

Cet attrait occidental pour les musiques non européennes a été long à venir. Le traité sur la musique égyptienne de l’ethnomusicologue précurseur Guillaume-André Villoteau est à ce titre éloquent. Parti en Égypte avec Bonaparte en 1797, son rejet des musiques folk égyptiennes, son mépris des improvisations à la flûte, son insistance sur les racines perdues de la glorieuse Égypte antique, son utilisation d’un vocabulaire péjoratif («?ritournelle superflue?») et son dégoût de la danse du ventre qu’il assimilait à de la débauche laissent peu de place à son appréciation des mélopées, mélismes et ornements des chants de muezzins. Ce type de point de vue ethnocentriste est resté répandu en occident, y compris chez les Afro-américains.

Acculturation

Différentes lois «?Jim Crow?» furent appliquées à l’issue de la guerre de Sécession en 1865, peu après l’abolition de l’esclavage. Elles entérinèrent une stricte ségrégation raciale qui allait perdurer aux États-Unis pendant au moins un siècle. Dans le Sud des États-Unis, l’organisation criminelle blanche d’extrême-droite le Ku Klux Klan était au sommet de sa puissance. Fruit de l’ignorance, elle entretenait la terreur en commettant chaque semaine plusieurs crimes atroces en toute impunité.

Dans les territoires anglophones du continent (Canada, États-Unis) et autour de la mer des Caraïbes (Bahamas25, Bermudes26, Belize, Grenade, Guyana, Jamaïque8, Trinité-et-Tobago23, Îles Vierges28, etc.), les Afro-américains étaient dévalorisés. Le complexe de supériorité des Blancs et d’infériorité des «?Noirs?» était érigé en système jusqu’en Afrique même. L’acculturation des esclaves ayant été obligatoire pendant des siècles, le modèle blanc restait paradoxalement la référence, le seul modèle à suivre. Beaucoup de Noirs et de métis voulaient se confondre avec les Blancs afin de s’intégrer dans leur société : cheveux passés à la cire, maquillage éclaircissant… rares étaient donc ceux qui avant la Première Guerre Mondiale (1914-1918) songeaient à mettre en avant leurs origines africaines. C’est ce que feraient à demi-mot Slim and Slam en 1941 dans leur humoristique African Jive - mais toujours avec une pointe de moquerie «?Oncle Tom?» dans un esprit à la limite du ménestrel «?Jim Crow?». Enregistré en 1920 par des Anglais blancs, Soudan est l’un des premiers enregistrements de jazz à évoquer l’Afrique.

Intégration

Mais l’intégration semblait impossible. La mentalité ambiante incitait la plupart des Blancs, même les plus modérés, à considérer les Noirs comme des «?niggers?», «?coons?», «?sambos?», «?dandies» et «?Jim Crows?», une espèce physiquement, mentalement et culturellement inférieure (Essai sur l’inégalité des races humaines de Joseph Arthur de Gobineau, 1855). Cette supposée non appartenance à la «?race supérieure?» semblait justifier le mépris et l’absence de compassion pour leur douleur. Cette prétendue «?non humanité?» excusait tous les abus. L’insulte s’ajoutait à la blessure : ce racisme pseudo scientifique repris par les Nazis les présentait comme des animaux sauvages, sous-hommes fainéants, parasites, à demi-civilisés, malhonnêtes, stupides, à la naïveté et l’insouciance proverbiale — et, grand cauchemar des puritains, animés de bas instincts lubriques. Schématiquement, la culture chrétienne occidentale estimait depuis des siècles que seule l’âme pouvait élever l’Homme vers Dieu. Le corps était source de péché. En conséquence, la musique devait s’adresser à la tête et non au corps. Or nombre de musiques spirituelles africaines stimulent et réunissent les deux : l’esprit ET le corps. Qui en interagissant dans la transe, permettent d’entrer en contact avec les esprits — avec «?Dieu?». Ainsi pour les Euro-américains et leurs religions puritaines, toute danse libre et suggestive était la preuve d’une supposée animalité. Appuyant ce stéréotype, Ted Lewis (un des premiers musiciens blancs du nord à copier le jazz) et le Noir Don Redman évoquent ici de libidineuses Africaines : Egyptian Ella, une danseuse réduite au chômage en raison de son obésité, trouve le succès en Égypte où l’on apprécie mieux ses formes. Et dans l’exquis Shakin’ the African (1931) les mots «?Africain?» et «?postérieur?» ne font pratiquement qu’un. Vingt ans avant Elvis Presley, le succès du jazz «?swing?» dansant du Blanc Benny Goodman en 1935 fut perçu comme le phénomène d’intégration et de mixité raciale qu’il était. Il choqua beaucoup de Blancs.

Exclusion

Dès 1899, Scott Joplin avait connu le succès avec son ragtime très dansant Maple Leaf Rag puis d’autres compositions remarquables. Il chercha toute sa vie la reconnaissance artistique de la haute société. En vain. Malgré ses succès populaires, trop «?noir?» et en avance sur son temps son «?opéra ragtime?» Treemonisha ne trouva pas preneur. Cet échec le ruina et le brisa en 1915. Le pianiste de ragtime9 Eubie Blake (1887-1983) eut plus de chance. En 1921 il parvint à monter avec Noble Sissle une des premières comédies musicales afro-américaines, Shuffle Along. Sa première composition, Sounds of Africa, a été écrite en 1903 et gravée en 1921.

Les premiers enregistrements de musiques afro-américaines comme les negro spirituals dans les années 1900 (perdus), le premier 78 tours du Lovey’s Trinidad String Band en 1912, du jazz10 (à partir de 1917) et du blues (à partir de 1920) n’étaient pas considérés comme des expressions artistiques dignes de ce nom. Ils étaient généralement perçus comme une anecdotique et grossière musique de danse populaire nègre — sans commune mesure avec la tradition écrite classique occidentale. Pourtant, certains ne s’y trompaient pas : le Tchèque Antonín Dvor?ák (directeur du Conservatoire National de Musique à New York de 1892 à 1895) comprenait que les musiques afro-américaine et indienne indigène étaient à la fondation d’un son états-unien propre qui cherchait encore son identité. Il s’intéressa notamment aux negro spirituals11, expression d’essence africaine par excellence. Admirateur d’Art Tatum, le new-yorkais blanc George Gershwin s’inspira du jazz et des negro spirituals. Il composa notamment Rhapsody in Blue (1924) et Summertime (1935).

«?Vous, les Américains, prenez le jazz trop à la légère. Vous semblez y voir une musique de peu de valeur, vulgaire, éphémère. Alors qu’à mes yeux, c’est lui qui donnera naissance à la musique nationale des États-Unis.?»

Maurice Ravel au Musical Digest, avril 1928

Caraïbes

Il avait fallu attendre que le pianiste surdoué et virtuose Louis Moreau Gottschalk (1829-1869) compose «?La Bamboula?» (1844), puis La Savane (1846), basé sur la chanson wallone «?Lolote» (de Jacques Bertrand, 1917-1884) pour qu’un hommage à l’Afrique surgisse dans la musique américaine. Né et élevé à la Nouvelle-Orléans d’un père juif allemand et d’une créole blanche originaire de Saint-Domingue, Gottschalk a été le premier musicien américain à incorporer des éléments créoles afro-américains et caribéens à son œuvre de tradition écrite «?classique?» occidentale. Ayant étudié la composition à Paris où il fut révéré par Chopin, c’est avec ces œuvres précoces, inspirées par ce qu’il avait entendu en Louisiane dans son enfance qu’il devint le premier pianiste américain célèbre et put donner des récitals dans le monde entier. Douce pièce romantique évoquant un paysage africain, La Savane a été enregistrée pour la première fois en 1956 par Eugene List, un autre virtuose américain connu pour ses inter-prétations de Chostakovitch. Disponible dans cette collection, le «?Bamboula?» de Gottschalk évoque la «?danse nègre?» à laquelle il assista sur Congo Square12. Il y incorpora un rythme entendu lors d’un concours de danse cake-walk13 à la racine du jazz de la Louisiane. Comme pour les negro spirituals, ces formes d’expression afro-américaines étaient marquées par la présence de Bantous (Congo), notamment ceux venus de Haïti et de Jamaïque, de Bambaras (Sénégal actuel) de Louisiane, et de divers Antillais venus de Cuba. En effet, nombre d’éléments culturels perçus comme étant «?africains?» aux États-Unis sont en réalité arrivés des Caraïbes : trois documents exceptionnels, enregistrés en Jamaïque à une époque où l’électricité n’était pas disponible dans les quartiers pauvres, figurent sur cet album. Ils sont analogues aux historiques bamboulas de Louisiane (jamais enregistrées) qui ont marqué Gottschalk, la naissance du jazz, Buddy Bolden, Bechet ou Armstrong. Kumina Bailo, aux accents de blues, présente des voix et des tambours aux racines vraisemblablement congolaises, analogues aux bamboulas bambara/bantoues (et autres ethnies) de Congo Square à la Nouvelle-Orléans vers 1900. Ce titre de 1953-56 provient d’authentiques cérémonies kumina, un culte afro-jamaïcain visant à préserver des éléments culturels africains excluant l’influence chrétienne. Les liens entre influences musicales ouest-africaines et blues sont assez floues, parfois ténues et souvent difficiles à relier14, tandis que les événements sociaux (carnavals, john canoe/junkunnu, bamboulas, etc.) et rituels (kumina, vaudou, ring shouts, negro spirituals, etc.) afro-caribéens s’imposent clairement comme les véritables racines du jazz, avec leurs rythmes marqués, hémioles, tambours, rivalités, compétitions, improvisations et liens spirituels avec les esprits des ancêtres.

Sur une rythmique jouée par la respiration des fidèles lors d’une transe revivaliste, Pukkumina Cymbal témoigne d’une expression vocale inspirée par les esprits, interprétée en glossolalie (tongues). Les improvisations du jazz sont vraisemblablement dérivées de ce type de rites de possession — une forme de spirituals. Mettant en scène des chansons satiriques, mascarades et défilés analogues au Mardi-Gras de la Nouvelle-Orléans, John Canoe Music suggère une forme de proto-jazz avec ses improvisations à la flûte «?drum and fife?» sur accompagnement de tambours15. Il existe des enregistrements drums and fife (influence de l’armée) plus récents aux États-Unis (Othar Turner, Jessie Mae Hemphill). La tradition John Canoe ou jonkunu est présente dans différents pays de la région, dont les Bahamas, le Belize et ici la Jamaïque. Il est décrit en détail dans le livret de Jamaica - Mento 1951-1958 (FA 5358 - nos livrets sont en ligne sur fremeaux.com) dans cette collection. Marqués par leurs racines africaines, ces derniers exemples sont de vraies créations musicales créoles : Ne retirons pas aux Afro-américains leurs essentielles contributions, distinctes de celles de l’Afrique.

Au XXe siècle, les conditions de vie d’une grande majorité d’Afro-américains sont longtemps restées proches de l’esclavage. Il avait été interdit aux esclaves d’évoquer l’Afrique, de parler leurs langues, de jouer leurs musiques, de pratiquer leurs spiritualités. Seuls deux tambours africains ont été retrouvés sur le continent nord-américain. Ainsi les représentations d’une Afrique effacée de l’Histoire, chargée de culpabilité et de honte, ont longtemps été rares en Amérique. Héritage du langage à double sens du jargon des esclaves, caractéristiques des negro spirituals, ces évocations du continent noir sont souvent restées allusives : sur I’m a Pilgrim, un vieux spirituals décrivant un «?pèlerin?» en route vers la terre promise, l’initié comprendra que le Golden Gate Jubilee Quartet évoque en réalité une évasion vers des terres du nord, moins racistes — et à la fois un retour vers «?home?», l’Afrique. Des mots-clés signifiant l’Afrique étaient utilisés : «?Zoulou?», «?Congo», «?jungle?» et «?tambours?». Les «?bongos?» métaphoriques ont par exemple donné leur nom au Bongo Boogie d’Annisteen Allen.

Mardi Gras

La tradition du Mardi-Gras remonte au XVIIe siècle, quand la Louisiane était française. Les Caraïbes ne sont-elles pas en Amérique — et la Nouvelle-Orléans ne fait-elle pas partie des Caraïbes ? À la Nouvelle-Orléans, les Noirs (dont le groupe culturel des «?Indiens?» revendiquant le mystérieux héritage de Congo Square) participaient à une manifestation typiquement caribéenne. Ils employaient l’expression Jock-o-Mo lors des festivités. En composant ce morceau Sugar Boy Crawford n’a fait que répéter «?jockomo feena nay?» sans en comprendre le sens (peut-être «?Tous les jours c’est la veille du nouvel an?» — ou plutôt le mercredi des Cendres). Ce morceau est devenu un standard de la région, renommé «?Iko Iko?» par les Dixie Cups en 1965. Il est possible que l’expression «?iko iko?» soit dérivée de Ayiko Ayiko qui au Nigeria signifie «?bienvenue, bienvenue, ma chérie?». Art Blakey a enregistré en 1962 un morceau de ce nom pour son album «?The African Beat». Ce fut sa première vraie collaboration avec des Nigerians (et Montego Joe, un percussionniste jamaïcain) : l’aboutissement de sa quête de l’Afrique. Sur Comments on African Drums, le grand batteur parle de son long voyage au Nigeria et l’importance des percussions dans l’évocation des événements quotidiens. Il y commente aussi son album «?Ritual?» de 1962.

Le Roi des Zoulous

Les Zoulous sont une ethnie dominante en Afrique du Sud. Le Mardi-Gras était l’occasion de porter en triomphe le «?roi des Zoulous?», une personnalité noire très populaire (quand elle n’était pas gardée secrète), réélue chaque année en comité secret depuis 1909 à la Nouvelle-Orléans. Fats Domino, un influent pianiste et chanteur de rhythm and blues de Louisiane, raconte dans Mardi-Gras in New Orleans qu’il veut «?rencontrer le roi des Zoulous?». Dans son album «?A Drum Is a Woman?», une fantaisie basée sur les conquêtes de la divine Madame Zajj, Duke Ellington évoque lui aussi un roi des Zoulous du début du XXe siècle. Dans l’imagination du Duke, ce roi aurait été Buddy Bolden, le légendaire fondateur du jazz à la Nouvelle-Orléans. Bolden n’a jamais enregistré, mais son style a été reproduit par ses contemporains et il est émulé ici par le trompettiste Clark Terry. Trois morceaux de cet album conceptuel d’Ellington consacré aux racines africaines et caribéennes du jazz sont inclus ici : Congo Square, New Orleans et Hey, Buddy Bolden. C’est encore au roi des Zoulous que font allusion King Oliver dans Zulu’s Ball (1923) et Louis Armstrong sur The King of the Zulus, où un Jamaïcain au fort accent vient interrompre le solo de trombone : il veut rivaliser avec Armstrong en interprétant un morceau de son pays, causant une altercation16.

Retour en Afrique

«?Des historiens ont écrit sur le fait que les esclaves n’étaient jamais directement amenés d’Afrique en Amérique, mais qu’ils étaient d’abord emmenés aux Caraïbes. On y trouvait des gens dont le boulot était de briser la volonté de l’esclave (le «?seasoning?» NDT). Une fois que c’était fait, que sa langue et ses caractéristiques culturelles étaient détruites, il était emmené vers l’Amérique. Ainsi la volonté des Noirs ou des Africains restés aux Caraïbes n’a pas été brisée à fond comme celle des Africains qui en fin de compte se sont retrouvés sur nos rivages.?»

Malcolm X 17

Il est donc logique que, comme pour le jazz lui-même, une part substantielle du mouvement de libération noir et de la transmission de cultures africaines soit venue des Caraïbes. Le culte yoruba des Orishas est par exemple resté très présent à Trinité-et-Tobago23, comme en témoigne le chanteur de calypso The Lion, qui interprète ici Hojoe-African War Song en dialecte yoruba trinidadien.

Les Antillais n’aimaient pas pour autant qu’on les confonde avec des Africains qu’ils considéraient souvent eux-mêmes être des «?primitifs?». Mais aux États-Unis, beaucoup considéraient l’identité africaine comme à peu près indistincte de l’identité caribéenne. Pour d’autres, les Noirs du monde ne constituaient qu’une seule nation : répondant aux œuvres d’écrivains états-uniens intégrationnistes trop modérés à son goût - tels Booker T. Washington ou W.E.B. Du Bois -, c’est le Jamaïcain Marcus Garvey qui le premier a su rassembler la diaspora africaine mondiale autour d’un mouvement militant radical. Installé à Harlem au cœur de New York en 1916, son United Negro Improvement Association a capté la frustration des soldats afro-américains de retour de la Première Guerre Mondiale. Démobilisés après de durs combats — au côté de Blancs — au nom de leur pays et de la liberté, ils ne trouvaient pas chez eux la considération à laquelle ils auraient dû avoir droit. Beaucoup se sont tournés vers Garvey. Ce nationaliste noir appelait tous les Noirs des «?Africains?». C’est eux qu’il salue ici sur Greetings to Fellow Citizens of Africa. Garvey prônait une organisation totalement indépendante des Blancs, où la valorisation de l’origine africaine était centrale. Garvey le panafricaniste a connu un succès retentissant dans le monde entier en 1919-1923. Il tenait deux idées fortes : «?L’Afrique aux Africains, qu’ils soient chez eux ou à l’étranger?» et un mouvement de retour vers l’Afrique, terre promise où il voulait apporter le savoir moderne. Certains de ses adeptes partirent pour le Liberia évoqué en 1960 par John Coltrane dans un morceau au nom de ce pays. Garvey disait parfois dans ses discours que s’il échouait de son vivant, son fantôme (ghost) reviendrait terroriser ses ennemis jusqu’à ce que son peuple obtienne justice — même si ça devait prendre deux cents ans.

Chanté par Abbey Lincoln dans Garvey’s Ghost avec Max Roach en 1961, Marcus Garvey alias «?Mosiah?» [Moïse] fut au cœur du courant culturel afro-américain de la Harlem Renaissance. Il inspira Malcolm X et de nombreux musiciens, notamment au sein du mouvement jamaïcain Rastafari18. Dans African Blues, enregistré à New York en 1924 avec des musiciens blancs, le Trinidadien noir Sam Manning fait allusion au mal du pays et à son désir de partir en Afrique (où il n’avait jamais mis les pieds) — une position typiquement garveyite. Faisant écho au «?Creole Love Call?» de Duke Ellington, le Trinidadien new-yorkais Houdini militait pour le mouvement de Marcus Garvey. Il met ici en valeur un Africain :

Je viens de bien loin sur la côte d’Afrique/Je suis un millionaire/J’ai des rubis des diamants et de l’or, de l’amour et des richesses à dévoiler/Hip hip hourra universel pour le son de l’Afrique […] Certains disent donnez-moi Booker T., mais moi je dis donnez-moi Marcus Garvey.

Wilmoth Houdini,

African Love Call, New York City, 1934

La Bible anglo-saxonne [“King James version”] utilise le terme “Éthiopie” pour évoquer l’Afrique toute entière. Reprenant les idées de Garvey et prenant la Bible à la lettre, un certain nombre d’Afro-américains (dont quelques Rastas de Jamaïque) “retournèrent” sur les terres éthiopiennes que l’empereur Haïlé Sélassié Ier leur offrit au début des années 195019. Inspiré par le mouvement Rastafari, sur Ethiopia le chanteur jamaïcain de mento Lord Lebby parle de ce pays de «?lait et de miel?» (Ex III-8; Dt VI-3), la terre promise par la Bible, où il «?retournera lors d’un jour glorieux?».

Jungle Sound

Avec Menelik The Lion of Juda, Rex Stewart et Duke Ellington préfèrent rendre hommage à l’empereur Ménélik II (1844-1913), le prédécesseur de Haïlé Sélassié qui unifia l’Éthiopie. Sur l’introduction, le tromboniste Joe «?Tricky Sam?» Nanton imite le son d’un rugissement de lion, symbole de la dynastie éthiopienne :

«?Il jouait une forme très personnelle de son héritage antillais. Quand un type des Antilles vient ici et qu’on lui demande de jouer du jazz, il joue ce qu’il pense être du jazz, ou une chose qui résulte de sa volonté de se conformer à cet idiome. Tricky et son peuple étaient à fond dans le mouvement des Antilles et de Marcus Garvey. Tout un pan de musiciens antillais a surgi et contribué à ce qu’on appelle le jazz. Ils descendaient virtuellement tous de la véritable scène africaine. C’est la même chose avec le mouvement musulman, il y a beaucoup d’Antillais qui en font partie. On y trouve beaucoup de points communs avec les projets de Marcus Garvey. Comme je l’ai déjà dit une fois, le bop est le prolongement de Marcus Garvey.?»

Duke Ellington 20

En 1927, King Oliver refusait un prestigieux engagement dans un cabaret de luxe réservé aux Blancs, le célèbre Cotton Club de Harlem21. La direction a alors commandé à Duke Ellington une musique accompagnant un spectacle «?exotique?» (danse, comédie, burlesque, etc.) évoquant l’Afrique «?primitive?». L’orchestre a ainsi créé un son idoine et très influent, appelé le «?jungle sound?» dont le chef-d’œuvre East St. Louis Toodle-Oo («?L’au-revoir à Saint-Louis Est?») est emblématique. Le morceau n’évoque pas Saint-Louis-du-Sénégal mais plutôt la ville industrielle d’East St. Louis dans l’Illinois, aux États-Unis. En 1917, l’arrivée de nombreux ouvriers afro-américains venus du sud concurrençait les travailleurs blancs. Une rumeur de relations sexuelles interraciales entre hommes noirs et femmes blanches causa le déferlement de milliers d’ouvriers blancs qui commirent des agressions raciales en masse et la destruction de centaines de maisons du ghetto noir. Trente-neuf Afro-américains perdirent la vie dans ces émeutes — le record du genre — où nombre d’abominables lynchages publics ont eu lieu. On peut entendre ici le trombone bouché de Tricky Sam et la trompette bouchée de Bubber Miley dans le populaire style growl («grondement?») de l’orchestre, qui était identifié comme une expression des mystères de la jungle africaine.

Jazz Moderne

Le principe de la trompette bouchée (initialement par un chapeau) trouve son origine dans l’interdiction qu’avaient les orchestres de jazz de jouer à plein volume la nuit dans les cabarets de la Nouvelle-Orléans, où certains musiciens parvenaient à réduire ainsi leur niveau sonore. Il sera repris par nombre de trompettistes, parmi lesquels Miles Davis, entendu ici avec Charlie Parker sur le chef-d’œuvre A Night in Tunisia. Parker fut l’icône des hipsters marginaux, puis de la beat generation. Avec ses improvisations éblouissantes, il personnifia le musicien de jazz sans compromis artistique. Bird était considéré comme un intellectuel plutôt qu’un divertisseur — un statut subversif et un pas de géant pour la reconnaissance artistique d’un Noir. Avec l’irruption du mouvement be-bop dans l’après-guerre, l’Afrique a été saluée par un nombre croissant de musiciens, comme Red Norvo (Congo Blues) avec Charlie Parker. La version originelle du standard A Night in Tunisia par Dizzy Gillespie a été écrite en 1943. Son titre a été soufflé par Earl Hines en raison des opérations militaires qui avaient lieu en Tunisie. Rappelons au passage que le vibraphone joué ici par Milt Jackson (et par Red Norvo avec Parker, sans oublier Ruben la Motta sur Voodoo Woman) descend directement du balafon de bois mandingue/bantou analogue au marimba entendu chez Mongo Santamaría.

Duke Ellington a lui aussi largement contribué à améliorer l’image des Afro-américains et des Africains dans le monde. Courtisé par la haute société dès les années 1920, sa distinction, son élégance et son génie ont vite été reconnus au-delà des océans. Ses évocations de l’Afrique et de la négritude ont été plus nombreuses que celles de la plupart de ses contemporains. L’album «?A Drum Is a Woman?», qu’il narre lui-même (extraits sur le CD2), en est un exemple remarquable. Le sublime Fleurette Africaine en est un autre.

Signifying Monkey

Trois variantes de Signifying Monkey figurent sur cet album : la version du Big Three Trio, Jungle King par Cab Calloway et une reprise par Oscar Brown Jr. D’autres artistes afro-américains en enregistreront une version, notamment Rudy Ray Moore (alias Dolemite). Le signifying est un jeu pratiqué aux États-Unis par les enfants et les adolescents. Joute verbale, il consiste à défier ses adversaires en public et à leur répondre avec répartie et humour, comme par exemple dans Say Man, un succès de Bo Diddley en 1959 où le signifying est comme ici mis en musique22. Le signifying rappelle à la fois à la tra-dition afro-américaine des dirty dozens, les affron-tements verbaux du calypso des carnavals de la Trinité-et-Tobago23, les clash des DJ au micro dans les sound systems jamaïcains ou le boasting et autres rapper battles du hip hop. Dans le folklore états-unien le signifying monkey est un personnage de singe arnaqueur, ici mis en scène dans le premier groupe du célèbre bassiste Willie Dixon (qui deviendra par la suite l’un des plus grands auteurs-compositeurs du blues). Rusé, malhonnête, ce singe est d’une grande éloquence et parvient ici à con-vaincre le lion de défier l’éléphant. Cela vaut une raclée au lion qui veut ensuite se venger sur le singe. Cette histoire trouve son origine dans une fable inspirée par un personnage des Orishas, la mythologie yoruba (Bénin, Nigeria). Le singe est un compagnon habituel de la puissante divinité yoruba Esu Elegbara (alias Exu, Echu-Elegua, Papa Legba, Papa le Bas, etc.). Symbole du carrefour et du destin, messager divin confrontant à la vérité éternelle, incarnation de la mort, voire du diable, on retrouve ce personnage complexe dans le vaudou ouest-africain, caribéen et états-unien, notamment dans le classique «?Cross Road Blues24?» de Robert Johnson. Le principe de l’animal malin, baratineur et impertinent jouant des tours à ses camarades se retrouve dans nombre de fables et de contes africains. Trouvant son origine chez les Ashantis de l’ethnie Akan au Ghana actuel, le personnage de l’araignée Anansi joue également ce rôle. Anansi est récurrent dans le folklore ouest-africain, caribéen et jamaïcain en particulier. Chez les Bantous on retrouve ce principe dans la fable de la panthère et la tortue (Kulu Ba Dzé, analogue au Lièvre et la tortue de Jean de la Fontaine) et chez les Ouolof du Sénégal où la hyène incarne le fauteur de troubles rusé. En France, les célèbres fables de la Fontaine sont proches de ce type d’histoire où le goupil tire avantage de la faune des campagnes.

Le poète achemine la connaissance du monde dans son épaisseur et sa durée, l’envers lumineux de l’histoire qui a l’homme pour seul témoin.

Édouard Glissant

Vaudou

La Nouvelle-Orléans est une ville très liée aux Caraïbes par sa culture. De la Trinité à la Louisiane, les Antillais ont mieux résisté à l’acculturation des siècles d’esclavage que dans le sud des États-Unis. À Nassau par exemple, le banjoïste Blind Blake chantait Goombay Drum : en Guinée-Bissau, d’où provinrent certains esclaves, le gumbe est une musique traditionnelle liée à la lutte anticoloniale. D’origine ouest africaine, ce terme bantou signifie «?tambour?». Le terme guinéen gumbe est sans doute à l’origine du nom du goombay («?calypso?» bahaméen25), du gombey (musique afro-caribéenne des Bermudes26) et peut-être même de la recette fétiche de l’état de Louisiane, le gumbo à base d’accras (appelés ki ngombo dans la région Ki Ngombo en Angola) consommé lors des carnavals du Mardi-Gras où jouaient et dansaient déjà des esclaves. C’est probablement de là que vient aussi le nom des goombehs, tambours carrés des Marrons jamaïcains, des descendants d’esclaves évadés.

Rejetés par Jésus selon la Bible, les cultes des esprits des morts étaient répandus aux Caraïbes. Ces spiritualités afro-américaines originaires du Bénin, du Nigeria et du Congo actuels (vaudou, obeah, etc.) se sont exportées des Caraïbes en Louisiane, puis dans le reste des États-Unis. Les évocations du vaudou dans le blues, le rock, le jazz et le calypso font l’objet d’un volume dans cette série (Voodoo in America 1926 - 1961, FA 5375). Le vaudou nord-américain s’est développé au XIXe siècle parmi les esclaves et Noirs libres des faubourgs et plantations créoles de la Nouvelle-Orléans. Réaction au cadre rigoriste du protestantisme américain, au racisme et à la ségrégation, cette porte fantasmée vers l’Afrique, ou douce hérésie érotique, est devenue un exutoire pour les musiciens afro-américains en quête de racines et d’identité. Le vaudou est souvent évoqué selon une vision typi-quement coloniale, aux stéréotypes superficiels de superstition (envoûtements). C’est le cas ici sur plusieurs titres : You’ve Got Me Voodoo’d de Louis Armstrong27 avec son intro à la Bo Diddley (un rythme des côtes d’Afrique Centrale) et trois «?calypsos?» issus d’artistes des Îles Vierges28 (États-Unis), pas loin de Haïti : Rookombey, Voodoo Woman et Obeah Man.

Free Africa/Free Jazz

Comme Soudan (joué par des Anglais), la version originale de la chanson sud-africaine Mbube de Solomon Linda and the Evening Birds figure ici au titre d’invitée spéciale - car elle n’est pas venue d’Amérique. Mais cette composition a bien marqué les États-Unis avec le succès d’une version instrumentale par Pete Seeger and the Weavers, «?Wimoweh?» (1952), puis sous le nom de The Lion Sleeps Tonight par les Tokens en 1961. De nombreuses reprises seront enregistrées par la suite, notamment par le Kingston Trio, Joan Baez, puis pour la bande du film «?Le Roi Lion?» et par les Français Henri Salvador, Pow Wow… Le style du groupe de Solomon Linda a aussi beaucoup marqué l’Afrique du Sud elle-même. Il fut à l’origine du genre isicathamiya rendu célèbre par les chanteurs de gospel Ladysmith Black Mambazo.

Les expressions musicales caribéennes des carnavals divers, du Mardi-Gras, du John Canoe, des rites marrons, vaudou, obeah, mais aussi des spirituals sous leurs diverses formes, kumina, afro-revivalistes ou chrétiens, gospel ou nyabinghi rastafarien, avec leur abondance de tambours, possessions, transes, médi-tations, improvisations poly-phoniques et contacts avec les esprits ont fasciné et marqué quelques-uns des plus grands musiciens américains. Dans leur quête spirituelle, ces artistes ont également été inspirés par les musiques africaines d’où émanent les rites originels.

Formé vers 1948 et dérivé des rites kumina et des tambours congolais ntoré qui avaient survécu en Jamaïque (sous le nom de buru notamment), l’ensemble de percussions nyabinghi du Rasta Jamaïcain Count Ossie29 en est un exemple édifiant. Le groupe d’Ossie faisait souvent le bœuf avec les meilleurs jazzmen de son île. Sans doute la plus ancienne formation de fusion afro-jazz, elle n’a pourtant été enregistrée qu’à partir de 1961. Dans ce document inédit, le grand saxophoniste jamaïcain Joe Harriott exécute une longue improvisation autour d’un thème de Charlie Parker, Moose the Mooche. Solide interprète de be-bop, Harriott a évolué vers le hard bop avant de culminer au début des années 1960 en s’inscrivant dans le courant new thing qui fit connaître Ornette Coleman, Albert Ayler, Eric Dolphy, Charles Mingus ou Don Cherry. Bien que peu reconnu de son vivant (il s’était exilé à Londres en 1951), Harriott reste un des grands créateurs du free jazz, qui reflétait une liberté d’expression totale en phase avec le mouvement de libération noir en plein essor. Le free jazz rappelle aussi la spontanéité d’enregistrements ethniques africains et caribéens. Le style toujours personnel de Joe Harriott évoluera vers une fusion du jazz avec d’autres musiques du monde, le raga indien notamment, un intérêt que John Coltrane partageait avec lui en 1961. Aux États-Unis, les Congo Blues de Red Norvo et Two for Timbuktu de Sonny Stitt portent un nom évoquant de hauts-lieux africains. L’album de Wilbur Harden avec Coltrane, Tanganyika Strut offre plus : le blues Dial Africa est joué sur un rythme watusi (écouter les timbales sur l’intro) inspiré par les Watusi Royal Drums enregistrés au Rwanda par Denis Roosevelt.

Mais le grand précurseur (Message from Kenya, 1953) d’une véritable influence musicale africaine sur le hard bop fut le grand batteur Art Blakey, qui évoque sur Comments on African Drums son voyage pionnier au Nigeria en 1947. Ses The Sacrifice (1957), Afrique et Ayiko Ayiko sont des modèles de cette fusion. Avec Jazz Sahara (1958) et ici sur La Ibkey, Ahmed Abdul-Malik fut sans doute le premier à le suivre dans cette direction en intégrant pour sa part une influence soudanaise à son jazz. En 1959, le succès inattendu du Drums of Passion de l’influent percussionniste yoruba Babatunde Olatunji accentua la tendance africaine dans le jazz. Cet ami de Coltrane est présent ici sur le Kucheza Blues (Kucheza signifie «?jouer?» en Swahili) de Randy Weston, qui consacrera ses albums des années 1960 à l’Afrique. L’Islam était considéré par certains comme la religion africaine par excellence. Plusieurs musiciens de jazz, dont Yusef Lateef et Sahib Shihab entendus sur ce morceau avaient pris des noms à consonance arabe (voir discographie) dans le but d’afficher leur orientation musulmane.

Avec l’arrivée à New York de la chanteuse Miriam Makeba en 1959, puis du trompettiste sud-africain Hugh Masekela, l’Afrique gagnait peu à peu une nouvelle aura. Quant à l’influence de Cuba sur la musique des États-Unis, comme pour la Jamaïque, Haïti ou Porto Rico elle pourrait faire l’objet d’un album entier à elle seule. Afro Blue, premier standard du jazz construit sur une hémiole — une approche rythmique typiquement africaine, mélangeant binaire et ternaire (2/3, ici un rythme abakuá du nord-ouest Cameroun) —, est une composition du percussionniste Mongo Santamaría, un Cubain installé aux États-Unis, alors déjà auteur du classique Afro-Cuban Drums (1952). En 1963 une célèbre version d’Afro Blue sera enregistrée par John Coltrane, qui continuera dans cette direction de fusion, comme d’autres grands jazzmen30 après lui31 — mais avec un arrangement rythmique d’Elvin Jones bien différent.

«?Il y a eu une influence de rythmes africains dans le jazz américain. On dirait que le jazz peut emprunter certains éléments harmoniques, mais je me suis cassé la tête à chercher quelque chose de rythmique. Rien ne swingue mieux que le 4/4. Ces apports de rythmes donnent de la variété.?» John Coltrane, mai 1961

Coltrane collectionnait les enregistrements de musi-ques africaines. Il a connu différentes phases créatives et, au sommet de son art en 1961 après des compositions très sophistiquées comme Giant Steps, Trane a brusquement laissé derrière lui les règles de la composition jazz. Il a décidé d’insuffler une influence purement africaine à sa nouvelle phase d’expérimentations. Pour son premier opus chez les disques Impulse! naissants, intitulé Africa/Brass, le monstre sacré de l’improvisation réunit une grande formation, un fait très inhabituel chez lui. Sa nouvelle période commençait. Elle traduit ici les chants polyphoniques pygmées en élaborations de soliste, visant une simple catharsis émotionnelle sur deux accords hypnotiques. Imprégné des églises revivalistes afro-américaines et de leurs rites de possession, Africa reflète la fascination de Coltrane pour les voix multiples des chants sacrés improvisés : des émanations pluralistes, polyphoniques, polythéistes et spontanées de la divinité. La boucle était bouclée puisque la musique traditionnelle africaine est à la fois une expression symbolique et une validation de l’énergie psychique. Une entité vivante, enrobée de l’âme de l’énergie spirituelle qui voyage à travers elle.

Bruno Blum

Merci à Kenneth Bilby, Francis Blum, Giulia Bonacci, Jon Cleary, Stéphane Colin, Christian Corre, Mike Garnice, Joël Heuillon, Linton Kwesi Johnson, Olive Lewin, Denis-Constant Martin, Rosalia Martinez, Philippe Michel, Herbie Miller, Frédéric Saffar, Brian Setzer, Maurice Steiker, Khadi et Michel Tourte, Fabrice Uriac, Michael Veal et Norman C. Weinstein.

© Frémeaux & Associés

1. Journal Officiel de la République Française n°119 du 23 mai 2001, page 8175.

2. Éditions Folio, collection Essais, 1989 (ISBN 2-07-032413-3), chapitre 3, page 22. Le texte intégral de Tristes Tropiques de Levi-Strauss lu par Jean-Pierre Lorit est aussi disponible dans cette collection (FA 8115).

3. Écouter l’anthologie Harry Belafonte - Calypso - Mento - Folk 1954 - 1957 (FA 5234) dans cette collection.

4. Écouter Roots of Mambo 1930 - 1950 (FA 5128) et Mambo Big Bands 1946 - 1957 (FA 5210) dans cette collection.

5. Écouter Roots of Bossa Nova 1948-1957 (FA 5216) dans cette collection.

6. Écouter Antonio Carlos Jobim, Vinicius de Morales, João Gilberto : Bossa Nova - La sainte Trinité 1958 - 1961 (FA 5363) et João Gilberto (FA 5371) dans cette collection.

7. Écouter les deux premier 45 tours de Bob Marley, enregistrés en 1962, sur l’album Jamaica- USA Roots of Ska - Rhythm and Blues Shuffle 1942 - 1962 (FA5396) dans cette collection.

8. Écouter l’anthologie Jamaica - Mento 1951 - 1958 (FA 5275) dans cette collection.

9. Écouter From Cake-Walk to Ragtime 1898 - 1916 (FA 067) dans cette collection.

10. Écouter l’anthologie Early Jazz 1917 - 1923 (FA 181) dans cette collection.

11. Écouter Gospel - Negro Spirituals - Gospel Songs 1926 - 1942 (FA 008) et l’anthologie thématique Slavery in America à paraître dans cette collection.

12. Son «?Bamboula?» sera disponible sur l’album Slavery in America 1926 - 1962 à paraître dans cette collection.

13. Écouter From Cake-Walk to Ragtime 1898 - 1916 (FA 067) dans cette collection.

14. Lire et écouter le disque Africa and the Blues de Gerhardt Kubik (University Press of Mississippi, 1999).

15. Ces trois titres sont extraits de Jamaica - Trance - Possession - Folk 1939 - 1961 (FA5384) dans cette collection.

16. Extrait de FA 1353. Une grande partie de l’œuvre de Louis Armstrong est disponible dans cette collection.

17. Amy Garvey, Garvey and Garveyism (New York, Macmillan Publishing Co., 1970, p. 305-306, cité par Norman C. Weinstein dans A Night in Tunisia.

18. Écouter les albums de reggae de Burning Spear Marcus Garvey (Wolf/Island 1975) et Garvey’s Ghost (dub) qui lui rendent hommage et l’anthologie Human Race (Rastafari/Patch Work 2011), une production jamaïcaine de Bruno Blum où l’on peut entendre d’autres extraits de la voix de Garvey.

19. Lire Exodus - L’histoire du retour des Rastafariens en Éthiopie de Giulia Bonacci (L’Harmattan, 2010).

20. Extrait de l’autobiographie de Duke Ellington, Music Is my Mistress (Doubleday, Garden City, N.Y., 1973). , p. 108-109.

21. Écouter l’anthologie Cotton Club 1924 - 1936 (FA 074) dans cette collection.

22. Dans cette collection Bo Diddley explique lui-même le signifying dans le livret de Bo Diddley - The Indispensable 1955 - 1960 (FA 5376), qui inclut Say Man.

23. Lire le livret et écouter de l’anthologie Trinidad - Calypso 1939 - 1959 (FA 5348) dans cette collection.

24. Récurrent dans le vaudou, le thème du carrefour du destin est évoqué dans le grand classique du blues de Robert Johnson Cross Road Blues, disponible sur l’anthologie Voodoo in America 1926-1961 (FA 5375) dans cette collection.

25. Écouter Bahamas - Goombay 1951 - 1959 (FA 5348) du même auteur. Plusieurs autres titres de Blind Blake y figurent.

26. Écouter Bermuda - Gombey & Calypso 1953 - 1960 (FA5374) du même auteur.

27. L’œuvre intégrale de Louis Armstrong est disponible dans cette collection.

28. Ces trois titres sont extraits de Virgin Islands - Calypso à paraître en 2013).

29. Retrouvez Count Ossie sur Jamaica - Rhythm and Blues 1956 - 1961 (FA 5358) et Jamaica - Trance - Possession - Folk 1939 - 1961 (FA5384) du même auteur.

30. Lire A Night in Tunisia - Imaginings of Africa in Jazz de Norman C. Weinstein (Limelight, New York 1992).

31. Écouter Afro-Blue (Impulse!) par John Coltrane et les deux anthologies du même nom consacrées à l’influence de l’Afrique sur le jazz des années 1960-1970 (Blue Note).

Africa seen by Americans

Between the 1920s and the 1960s, Afro-Americans including West Indians were to endure opression. Until the Forties, at least in The United States, black people were represented onstage by “black face minstrels”, i.e. white minstrels in black make-up who represented them as ridiculous figures (cf. the “Jim Crow” character created by Thomas “Daddy” Rice towards 1828). These highly-popular minstrel shows were eventually taken over by Afro-Americans who copied their racist content as it was a condition of their access to the professional stage. Cruel discrimination was also endured in various degrees by other minorities but the most disdained of all were undoubtedly the distant Africans, who were considered as primitives fearing neither God nor man; they were seen as pagan barbarians with neither civilisation nor culture, no writings and no history, in other words, stereotypes like those sung here (perhaps in the second degree?) on Stranded in the Jungle by the Jayhawks, the Cadets and soon the New York Dolls.

The barbarian is above all the man who believes in barbarism.

Claude Lévi-Strauss, Race et histoire, 1952 1

American zoos exhibited the pygmy Ota Benga – he committed suicide in 1916 –, Kanaks were exhibited in Paris until 1931, and Africans in Brussels until 1958. The context was merciless: exoticism, paternalism, ignorance, racism, colonial expansion… How were Africans seen in American popular music? And how were they seen by their descendants, their Afro-American cousins?

We have a beautiful history, and we shall create another in the future that will astonish the world.

Marcus Garvey, around 1920

In this set we trace the way in which America’s musical vision of Africa evolved in the course of the 20th century, from the segregationist “Jim Crow” laws to triumph in the struggle for civil rights, and from the apogee of colonial empire to independence in the West Indies and Africa, (saluted here by the Trinidadian Lord Kitchener in Birth of Ghana). Finding self-respect was the first battle to be won. The principle of equal rights for Afro-Americans would only be established in the Sixties, and it would take another half-century to see the historic election in 2008 – and re-election in 2012 – of a mixed-race President of the United States, a jazz-fan named Barack Hussein Obama II born on August 4th 1961.

A good compromise, a good piece of legislation, is like a good sentence; or a good piece of music. Everybody can recognize it. They say, ‘Huh. It works. It makes sense.’

Barack Obama

World Music

It was at the start of the Fifties that popular music first began to take on a global dimension as a major ethnological happening. International tours by Egyptian singer Oum Kalsoum, Jamaican mento and calypso from Harry Belafonte2, and then Krio music in Sierra Leone, Latin jazz, Cuban son, rumba and mambo3, Congolese rumba and soon New York salsa, the Brazilian bossa nova4 of João Gilberto5, ostensible Cuban and African influences in jazz (like those which appear here), blues from The Rolling Stones or soul from The Animals, the hits of South African singer Miriam Makeba, the influence of the Indian musician Ravi Shankar on John Coltrane or George Harrison, ska, and soon the reggae of Bob Marley6...

Acculturation

Different “Jim Crow” laws were put into effect at the outcome of the Civil War in 1865, shortly after the abolition of slavery, and they ratified a strict racial segregation which would last for at least a century in The United States. In the south of the USA, the extremist right-wing white criminal organization known as the Ku Klux Klan was at its peak. Many Blacks and mixed-race people wanted to merge with Whites in order to integrate their society: they waxed their hair and used make-up to lighten their skin... rare were those who, before World War I (1914-1918), had thoughts of highlighting their African origins. Slim and Slam would do so (without spelling it out in as many words) when they did their comic African Jive in 1941, although there was still a hint of “Uncle Tom” derision in the Jim Crow/minstrel vein. Recorded in 1920 by white Englishmen, Soudan is one of the first jazz recordings to evoke Africa. On Ubangi Stomp (1956) you have Warren Smith, a white singer – rockabilly this time – evoking his desire for a Congolese woman during memorable festivities on the banks of the Ubangi River.

Integration & Exclusion

Western Christian culture had deemed for centuries that only the soul could raise Man towards God. The body was the source of sin. Consequently, music should address the mind, not the body. But many kinds of African religious music stimulated and joined both mind and body. Emphasizing the stereotype, Ted Lewis (one of the first white musicians from the north who copied jazz) and the Black Don Redman here evoke lewd African women: Egyptian Ella, a dancer thrown out of work because of her obesity, finds success in Egypt, where her generous forms are better appreciated. And in the exquisite Shakin’ the African (1931), the words “African” and “posterior” are practically synonyms for the same thing... Twenty years before Elvis Presley, the success of the “swing jazz” of white clarinettist Benny Goodman in 1935 was perceived as the phenomenon of integration and mixed race which it actually was... and it shocked many Whites.

As early as 1899, Scott Joplin had met with success thanks to his highly danceable ragtime tune Maple Leaf Rag, which was followed by other remarkable compositions. He spent his whole life seeking recognition in society as an artist, but in vain: in spite of his popular success, his “ragtime opera” called Treemonisha, too “black” and much too ahead of its time, didn’t find any takers. Its failure ruined him and left him a broken man in 1915. Ragtime7 pianist Eubie Blake (1887-1983) was luckier. In 1921, with Noble Sissle, he succeeded in staging one of the first Afro-American musicals, Shuffle Along. His first composition Sounds of Africa was written in 1903 and recorded in 1921.

The first Afro-American music recordings – like the lost Negro spirituals of the 1900s, the first 78rpm by Lovey’s Trinidad String Band in 1912, jazz8 (from 1917 onwards) and blues (from 1920) – were not considered worthy to be called artistic expressions; they were generally perceived as trivia, as rough-and-ready Negro popular dance music – with nothing ranking among the classical, western written tradition. Yet some composers made no mistake: the Czech musician Antonín Dvor?ák – he was director of the National Conservatory of Music in New York from 1892 to 1895 – understood that Afro-American and indigenous Indian music lay at the foundation of a United States sound of its own. He took special interest in Negro spirituals9.

“You Americans take jazz too lightly. You seem to see it as music that is worthless, vulgar and ephemeral. But I believe it will give birth to the national music of the United States.”

Maurice Ravel in the Musical Digest, April 1928

West Indies

One had to wait for the great gifts of piano virtuoso Louis Moreau Gottschalk (1829-1869) and his compositions “La Bamboula” (1844) and then La Savane (1846), based on the Walloon song “Lolote” (by Jacques Bertrand, 1917-1884), for a tribute to Africa to suddenly appear in American music. Born and raised in New Orleans by a German-Jewish father and a white Creole mother born in Santo Domingo, Gottschalk was the first American musician to incorporate Afro-American and Creole elements in a work in the “classical” western written tradition. After studying composition in Paris where he was revered by Chopin, he was inspired to write these precocious works by what he’d heard in Louisiana as a child, and he went on to become the first American pianist to gain celebrity, giving recitals around the world. A softly romantic piece that evoked an African landscape, La Savane was recorded for the first time in 1956 by Eugene List. A number of cultural elements seen as “African” in The United States were actually from the West Indies: Three exceptional recordings made in Jamaica can be heard on this album, and they date from a period when electricity was unknown in poor areas. They have analogies with the historic bamboulas in Louisiana (never recorded) which left their mark on Gottschalk, and also with the birth of jazz. Kumina Bailo‘s title from 1953-56 comes to us from authentic Kumina ceremonies which practised a form of Afro-Jamaican worship seeking to preserve African cultural elements (with the exclusion of Christian influences). Over a rhythm “played” by the faithful breathing heavily in a revivalist trance, Pukkumina Cymbal is evidence of a vocal expression inspired by spirits and interpreted with glossolalia (“the gift of tongues”). Involving satirical songs, masquerades and processions similar to Mardi-Gras in New Orleans, the army-influenced John Canoe Music suggests a form of proto-jazz with its “drum and fife” flute improvisations over a drum-accom-paniment10 (hear similar U.S recordings by Othar Turner, Jessie Mae Hemphill). The John Canoe or jonkunu tradition is present in different countries across the region, including The Bahamas, Belize and Jamaica. A detailed description appears in the booklet accompanying Jamaica - Mento 1951-1958 (FA 5358). Although influenced by their African roots, the latter few examples are creole musical creations; One should not deprive Afro-Americans from their essential contributions, which are distinct from those of Africa.

In the 20th century, living-conditions of the great majority of Afro-Americans long remained close to those of slavery. Slaves were forbidden to refer to Africa, to speak their own languages, play their own music or practise their religions. As the legacy of the double-entendres in the language of slaves, and characteristic of Negro spirituals, these evocations of the dark continent have often remained allusive: in I’m a Pilgrim, an old spiritual describing a “pilgrim” on the road to the Promised Land, the initiated will understand that the Golden Gate Jubilee Quartet is actually referring to escape to the lands of the North where there was less racism, and also a reference to the return “home” (meaning “to Africa”). Key-words used to refer to Africa included “Zulu”, “Congo”, “jungle” and “drums”, and the metaphor “bongos”, for example, gave the Annisteen Allen song Bongo Boogie its title.

Mardi-Gras

The Mardi-Gras tradition goes back to the 17th century, when Louisiana was still a French possession. In New Orleans, Blacks (including the “Indian” cultural group who still claim the mysterious Congo Square legacy as its own) took part in a typically West Indian event which used the expression Jock-o-Mo in its festivities. When he composed this piece, Sugar Boy Crawford merely repeated jockomo feena nay without understanding the meaning (it perhaps means “Every day is New Year’s Eve” or rather “Ash Wednesday”) and the piece became a standard throughout the region, renamed “Iko Iko” by the Dixie Cups in 1965. It’s possible that the expression “iko iko” comes from Ayiko Ayiko, which in Nigeria means “Welcome, my dear”. Art Blakey recorded a piece with this title in 1962 for his album “The African Beat”, his first real association with Nigerians (and Montego Joe, a Jamaican percussionist); it was also the outcome of his long quest for Africa. In Comments on African Drums, the great drummer speaks of his long trip to Nigeria and the importance of percussion in evoking day-to-day events. He also comments his “Ritual” album of 1962 on it.

The King of the Zulus

Zulus are a dominant ethnic group in South Africa. Mardi-Gras was the opportunity to carry the “Zulu King” in triumph; the title was given to a very popular black personality (when it wasn’t kept a secret) who had been elected by secret ballot in Louisiana every year since 1909. Fats Domino, an influential pianist and Rhythm and Blues singer from Louisiana, says in Mardi-Gras in New Orleans that he wants to “meet the King of the Zulus”. In his album “A Drum Is a Woman”, a fantasia based on the conquests of the divine Madam Zajj, Duke Ellington also makes reference to a King of the Zulus from the beginning of the 20th century. There are three pieces here from that Ellington concept-album devoted to the African and West Indian roots of jazz: Congo Square, New Orleans and Hey, Buddy Bolden. The King of the Zulus is also a reference in Zulu’s Ball (1923) by King Oliver, and evidently in Louis Armstrong’s The King of the Zulus, where a strong Jamaican accent interrupts the trombone solo.11

Back to Africa

“Historians have written about the fact that slaves were not brought directly to America from Africa, but first taken to the West Indies. There were people there whose job was to break a slave’s will – [author’s note: it was called “seasoning”] – and once this was done, and his language and cultural traits were destroyed, he was taken to America. So the willpower of Blacks or Africans who remained in the West Indies wasn’t totally broken, unlike that of the Africans who finally found themselves on our shores.”

Malcolm X 12

So it’s logical that, as in jazz itself, a substantial part of the Black Liberation movement and the transmission of African cultures originally came out of the West Indies. The Orisha religion of the Yorubas, for example, has remained very much alive in Trinidad and Tobago23, as evidenced by calypso-singer The Lion, who performs Hojoe-African War Song here in a Trinidadian Yoruba dialect.

In The United States, many considered the African identity as almost indistinct from the West Indian identity. For others, the Blacks in the world formed but a single nation: in answer to the works of integrationist U.S. writers who were too moderate for his own tastes – Booker T. Washington, W.E.B. Du Bois –, the Jamaican Marcus Garvey was the first to bring together the African Diasporas of the world. Set up in Harlem in the heart of New York in 1916, his United Negro Improvement Association captured the frustration of Afro-American soldiers returning from the Great War. This Black Nationalist called all Blacks “Africans”, and they are the ones he salutes here in Greetings to Fellow Citizens of Africa. Garvey, the advocate of Pan-Africanism, met with immense success worldwide between 1919 and 1923. Some of his adepts left for Liberia, the country which John Coltrane evoked in 1960 in a piece of the same name. Praised by Abbey Lincoln’s song with Max Roach in 1961 (Garvey’s Ghost), Marcus Mosiah (“Moses”) Garvey was at the heart of the Afro-American cultural trend of the Harlem Renaissance. He inspired Malcolm X and numerous musicians, notably in the bosom of the Jamaican Rastafari13 movement. In African Blues, recorded in New York in 1924 with white musicians, the black Trinidadian Sam Manning alludes to homesickness and his desire to leave for Africa (where he’d never set foot). Echoing Duke Ellington’s “Creole Love Call”, the New York Trinidadian Houdini was an activist for Garvey’s movement. Here he features an African:

Come from far on the coast of Africa

I’m a millionaire

I’ve got rubies diamonds and gold...

Hip hip hurrah for the sound of Africa universally

Some people say give me Booker T,

But I say give me Marcus Garvey

Wilmoth Houdini, African Love Call,

New York City, 1934

The King James Bible uses the term Ethiopia to refer to the whole of Africa. Taking up Garvey’s ideas (and taking the Bible literally), a certain number of Afro-Americans (including a few Rastas from Jamaica) “returned” to the soil of Ethiopia and the land which Emperor Haile Selassie Ist gave to them as a present in the early Fifties14. Inspired by the Rastafari movement, in Ethiopia the Jamaican mento singer Lord Lebby speaks of this land flowing with “milk and honey” (Deuteronomy 6-3), the Promised Land of the Bible to which he will return on “a glorious morning”.

Jungle Sound

With the title Menelik The Lion of Juda, trumpeter Rex Stewart and Duke Ellington prefer to pay tribute to Emperor Menelik II (1844-1913), Haile Selassie’s predecessor who united Ethiopia. Over the introduction, trombonist Joe “Tricky Sam” Nanton imitates the sound of a roaring lion, the symbol of the Ethiopian dynasty:

“What he was actually doing was playing a very higly personalized form of his West Indian heritage. When a guy comes from the West Indies and is asked to play some jazz, he plays what he thinks it is, or what comes from his applying himself to the idiom. Tricky and the people were deep in the West Indian legacy and the Marcus Garvey movement. A whole strain of West Indian musicians came up who made contributions to the so-called jazz scene, and they were all virtually descended from the true African scene. It’s the same now with the Muslim Movement, and a lot of West Indian people are involved in it. There are many resemblances to the Marcus Garvey schemes. Bop, as I once said, is the Marcus Garvey extension.

Duke Ellington 15

In 1927 King Oliver turned down a prestigious booking at a luxury club reserved for Whites, the famous Cotton Club in Harlem16. So the management commissioned Duke Ellington to write music for an “exotic” show – dancers, comics, burlesque etc. – that evoked “primitive” Africa. The orchestra created a fitting sound that was highly influential: the “jungle sound” whose emblem was the masterpiece entitled East St. Louis Toodle-Oo. Here you can listen to Tricky Sam on trombone and Bubber Miley on trumpet – both with mutes – in the popular “growl” style of the orchestra, used as a symbolic expression of the mysterious African jungle.

Modern jazz

Playing a muted trumpet was a practice that stemmed from a ban on jazz orchestras making too much noise at night in the New Orleans clubs, and some musicians managed to get around the problem by holding a hat in front of the bell. Many trumpeters picked up the mute-habit, among them Miles Davis, heard here with Charlie Parker playing the masterpiece called A Night in Tunisia. Bop’s main figurehead, Parker was an icon for marginal hipsters, and then the Beat generation. His dazzling improvisations made him the personification of the uncompromising jazz musician. “Bird”, as he was known, was considered an intellectual rather than an entertainer – a subversive status that was a giant step forward in the recognition of black artists. When the bebop movement surged up in the post-war years, Africa was in the minds of an increasing number of musicians, including Red Norvo (Congo Blues). The original version of the Dizzy Gillespie standard named A Night in Tunisia was written in 1943, and owes its title to Earl Hines, who named it after military operations carried out in Tunisia. Note in passing that the vibraphone played here by Milt Jackson (or by Red Norvo with Parker, and not forgetting Ruben la Motta on Voodoo Woman) is the direct descendant of the wooden balafon played by Mandingo/Bantu peoples, similar to the marimba heard with Mongo Santamaría.

Duke Ellington also largely contributed to enhancing the image of Afro-Americans and Africans in the world. He was courted by high society as early as the Twenties and his distinguished appearance, elegance and genius were quickly recognised outside America also. Duke made more references to Africa and negritude than most of his contemporaries, and his album “A Drum Is a Woman”, where Duke is also the narrator (cf. CD2) is a remarkable example, as is the sublime title Fleurette Africaine.

Signifying Monkey

Three variants of Signifying Monkey appear on this album: the version by the Big Three Trio, Jungle King by Cab Calloway, and a reprise by Oscar Brown Jr. The term signifying comes from a game played by American children and teenagers who challenge each other in public and reply with humour and repartee, as in Say Man, for example, a Bo Diddley hit from 1959 where the signifying is set to music17. In U.S. folklore the signifying monkey is a trickster-monkey character, here featured in the first group led by the famous bassist Willie Dixon (who later became one of the greatest blues songwriters). Wily and dishonest, this monkey is quite eloquent, and succeeds in persuading the lion to defy the elephant... which earns the lion a beating, and so he wants his revenge on the monkey. This yoruba religion symbol of a crossroads and destiny, a divine messenger confronting eternal truth, the incarnation of death, even the devil, is a complex character to be found in voodoo in West Africa, the West Indies and also in the USA, notably in Robert Johnson’s classic “Cross Road Blues”18. La Fontaine’s French fables are close to this kind of story: the cunning fox is the animal who takes advantage of the others.

The poet conveys knowledge of the world in its density and duration, the radiant reverse of the story whose only witness is Man.

Édouard Glissant

Voodoo

From Trinidad to Louisiana, the people of the West Indies offered better resistance to acculturation over centuries of slavery than did the southern United States. In Nassau for example, banjo-player Blind Blake sang Goombay Drum: in Guinea-Bissau, where some slaves came from, gumbe is a traditional music genre linked to the struggle against colonisation. Originating in West Africa, the Bantu word gumbe means “drum”. References to voodoo in blues, rock, jazz and calypso are a theme explored in Voodoo in America 1926 - 1961 (FA 5375), and North-American voodoo developed in the 19th century amongst slaves and free black men in the outlying areas and plantations around New Orleans. It emerge in popular culture in the 20th as a reaction to the strict framework of American Protestantism, and to racism and segregation.

Free Africa/Free Jazz

Like Soudan (played by English artists), the original version of the South African song Mbube by Solomon Linda and the Evening Birds appears here as something of a “special guest” – because it doesn’t come from America. But this composition did leave its mark on America thanks to the success of the instrumental version by Pete Seeger and the Weavers, “Wimoweh” (1952), and then in the version The Lion Sleeps Tonight by the Tokens in 1961. The style of Solomon Linda and his group also left its mark on Africa itself; it was the origin of the isicathamiya genre made famous by the gospel singers of Ladysmith Black Mambazo.

The musical expressions of the West Indies used in various carnivals, at Mardi-Gras, at John Canoe parades and at Maroon, voodoo and obeah rituals, but also in spirituals in their varied forms, Kumina, Afro-revivalist or Christian, gospel or Rastafarian nyabinghi, with their abundance of percussion, trances, meditation, polyphonic improvisation and contact with spirits, have all fascinated some of the greatest American musicians, leaving an indelible mark. In their spiritual quest, these artists have also been inspired by African music-forms at the source of Caribbean rituals.

Founded in around 1948 and derived from the Kumina rites and ntoré drums from the Congo which had survived in Jamaica (notably under the name buru), the nyabinghi percussion-ensemble of the Jamaican Rasta Count Ossie19 is an edifying example of that inspiration. Ossie’s group often jammed with the best jazzmen on the island. Even though it was probably the first Afro-jazz fusion group, it wasn’t recorded until 1961. In this previously-unreleased track, the great Jamaican saxophonist Joe Harriott plays a lengthy improvisation around the Charlie Parker tune Moose the Mooche. A solid bebop player, Harriott developed into a Hard Bop stalwart before culminating with the new thing trend of the 1960s which brought attention to players like Ornette Coleman, Albert Ayler, Eric Dolphy, Charles Mingus, Cecil Taylor or Don Cherry. Free jazz also recalls the spontaneity of ethnic recordings made in Africa and the West Indies. In The United States, the Congo Blues of Red Norvo and Two for Timbuktu by Sonny Stitt both carry titles which evoke places that were Meccas for Africans. The album Wilbur Harden made with Coltrane called Tanganyika Strut goes further: the blues entitled Dial Africa is played over a Watusi rhythm (listen to the kettledrums in the intro) inspired by the Watusi Royal Drums recorded in Rwanda by Denis Roosevelt.

But the great trail-blazer – Message from Kenya, 1953 – of a genuine African musical influence on Hard Bop was the great drummer Art Blakey, whose Comments on African Drums related his pioneering voyage to Nigeria in 1947. His titles The Sacrifice (1957), Afrique and Ayiko Ayiko are models of that Afro-jazz fusion. With Jazz Sahara (1958), and La Ibkey here, Ahmed Abdul-Malik was no doubt the first to follow in this direction by integrating a Sudanese influence in his jazz. In 1959, the unexpected success of Drums of Passion by the influential Yoruba percussionist Babatunde Olatunji also contributed to accentuate the African tendency in jazz. A friend of Coltrane, he plays here on Kucheza Blues (Kucheza means “to play” in Swahili) by Randy Weston, the pianist who dedicated his Sixties albums to Africa. Islam was considered by some as the African religion par excellence, and several jazz musicians, including Yusef Lateef and Sahib Shihab (present on this tune), had taken Arab-sounding names (cf. discography) with the aim of displaying their Muslim leanings. Others like ancient Egypt-obessed Sun Ra incorporated percussions and an African image in their music.