- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

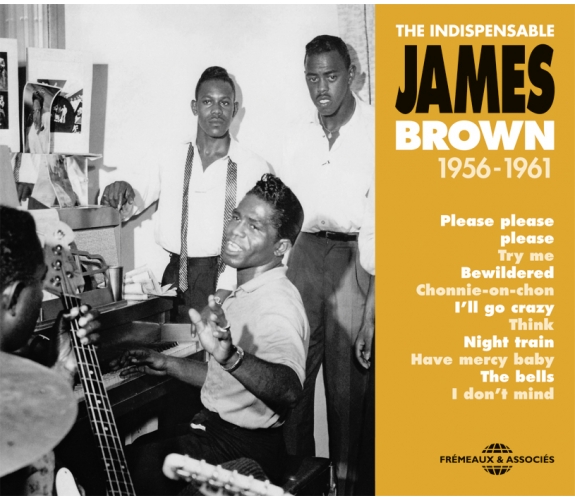

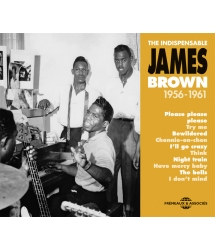

JAMES BROWN

JAMES BROWN

Ref.: FA5378

Artistic Direction : BRUNO BLUM

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Total duration of the pack : 2 hours 33 minutes

Nbre. CD : 3

JAMES BROWN

JAMES BROWN

A Giant of Afro-American music. James Brown turned rhythm & blues upside down and inside out when he blew the verve of Gospel right through it. This collection by Bruno Blum tells the story of the «Godfather of Soul» from the beginning with his splendid first recordings (including the legendary «Please, Please, Please»). One listen to these, and you can already feel the storm which this Soul Giant and unrivalled Funk King was going to kick all the way across the planet. Patrick FRÉMEAUX

OTIS REDDING • ARETHA FRANKLIN • JAMES BROWN • MARVIN...

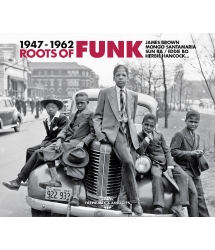

JAMES BROWN • MONGO SANTAMARIA • SUN RA / EDDIE BO •...

THE INDISPENSABLE 1949-1962

ELVIS PRESLEY & THE AMERICAN MUSIC HERITAGE...

I PUT A SPELL ON YOU - LIVE 1988

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Please Please PleaseJames BrownJames Brown00:02:461956

-

2I Feel That Old Feeling Coming OnJames BrownJames Brown00:02:351956

-

3Why Do You Do MeJames BrownJames Brown00:03:031956

-

4I Don't KnowJames BrownJames Brown00:02:481956

-

5I Walked AloneJames BrownJames Brown00:02:431956

-

6No, No, No, NoJames BrownJames Brown00:02:151956

-

7You're Mine, You're MineJames BrownJames Brown00:02:331956

-

8Hold My Baby's HandJames BrownJames Brown00:02:151956

-

9Chonnie-On-ChonJames BrownJames Brown00:02:141956

-

10I Won't Plead No MoreJames BrownJames Brown00:02:281956

-

11Just Won't Do RightJames BrownJames Brown00:02:361956

-

12Let's Make ItJames BrownJames Brown00:02:271956

-

13Gonna TryJames BrownJames Brown00:02:471956

-

14Can't Be The SameJames BrownJames Brown00:02:171956

-

15Messing With The BluesJames BrownJames Brown00:02:131957

-

16Fine Old Foxy SelfJames BrownJames Brown00:02:111957

-

17Love Is A GameJames BrownJames Brown00:02:181957

-

18Why Does Everything Happen To MeJames BrownJames Brown00:02:121957

-

19Begging, BeggingJames BrownJames Brown00:02:541957

-

20Baby Cries Over To The OceanJames BrownJames Brown00:02:351957

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Try MeJames BrownJames Brown00:02:331958

-

2Tell Me What I Did WrongJames BrownJames Brown00:02:241958

-

3That's When I Lost My HeartJames BrownJames Brown00:02:511958

-

4That Dood ItJames BrownJames Brown00:02:281958

-

5There Must Be A ReasonJames BrownJames Brown00:02:241958

-

6I'Ve Got To ChangeJames BrownJames Brown00:02:281958

-

7Got To CryJames BrownJames Brown00:02:351958

-

8It Was YouJames BrownJames Brown00:02:461958

-

9I Want You So BadJames BrownJames Brown00:02:481958

-

10It Hurts To Tell YouJames BrownJames Brown00:02:551958

-

11Don't Let It Happen To MeJames BrownJames Brown00:02:541959

-

12BewilderedJames BrownJames Brown00:02:271959

-

13Goos Good Lovin'James BrownJames Brown00:02:191959

-

14Wonder When You're Comin' HomeJames BrownJames Brown00:02:371959

-

15I'll Go CrazyJames BrownJames Brown00:02:091959

-

16This Old HeartJames BrownJames Brown00:02:121959

-

17I Know It S TrueJames BrownJames Brown00:02:431959

-

18ThinkJames BrownJames Brown00:02:471960

-

19I'll Never Never Let You GoJames BrownJames Brown00:02:221960

-

20You've Got The PowerJames BrownJames Brown00:02:221960

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1I Don't MindJames BrownJames Brown00:03:171960

-

2If You Want MeJames BrownJames Brown00:02:261960

-

3Baby You're RightJames BrownJames Brown00:03:011960

-

4Love Don't Love NobodyJames BrownJames Brown00:02:071960

-

5Come Over HereJames BrownJames Brown00:02:451960

-

6And I Do Just What I WantJames BrownJames Brown00:02:261960

-

7Just You And Me DarlingJames BrownJames Brown00:02:501960

-

8So LongJames BrownJames Brown00:02:511960

-

9Tell Me What Cha Gonna DoJames BrownJames Brown00:02:131960

-

10The BellsJames BrownJames Brown00:02:581960

-

11Hold ItJames BrownJames Brown00:02:111960

-

12Dancing Little ThingJames BrownJames Brown00:01:571961

-

13You Don't Have To GoJames BrownJames Brown00:02:481961

-

14Lost SomeoneJames BrownJames Brown00:03:281961

-

15Shout And ShimmyJames BrownJames Brown00:03:181961

-

16Night TrainJames BrownJames Brown00:03:421961

-

17Yes I DoJames BrownJames Brown00:02:491961

-

18Have Mercy BabyJames BrownJames Brown00:02:141961

-

19Just Won't Do RightJames BrownJames Brown00:02:421961

The indispensable James Brown FA5378

THE INDISPENSABLE

JAMES BROWN

1956-1961

Please please please

Try me

Bewildered

Chonnie-on-chon

I’ll go crazy

Think

Night train

Have mercy baby

The bells

I don’t mind

Funky

Né dans la misère d’une cabane sans eau ni électricité au fond d’une forêt de pins en Caroline du Sud, James Joseph Brown (3 mai 1933-25 décembre 2006) a été abandonné par ses parents. Il avait quatre ans lorsque sa mère est partit chercher une vie meilleure au nord du pays. Le gamin a ensuite été élevé par son père, mi-Africain mi-Apache, qui avait aussi du sang asiatique. Il recueillait la résine des arbres pour subvenir à ses besoins mais, trop pauvre, un an plus tard il s’est engagé dans la marine militaire, laissant à son tour tomber son fils. James a été recueilli par sa tante Honey, tenancière de maison close, qui l’a élevé dans la misère de sa maison habitée par une douzaine de personnes. L’enfant et son cousin, âgé d’un an de plus que lui, ont ainsi grandi pieds nus été comme hiver, ramassant du charbon sur la voie ferrée pour chauffer la maison, cirant les chaussures dans les rues et racolant activement les soldats vers le bordel familial. Ainsi, James a appris à danser pour attirer les bidasses et recevoir quelques pièces. C’est dans ce contexte sordide qu’a été élevé l’un des plus grands musiciens du XXe siècle, précurseur et futur roi incontesté de la soul music et du funk, compositeur, arrangeur, chanteur et danseur essentiel, champion absolu de la scène et influence déterminante sur presque tout ce qui lui succèdera dans la musique populaire américaine et au-delà : R&B, soul, funk mais aussi reggae, rap et hip hop.

Gospel

Solitaire, James Brown a passé beaucoup de temps dans les rues. Débrouillard, décidé à s’en sortir, il devint chanteur du Cremonia Trio à l’âge de douze ans et donna quelques premiers concerts au moment où s’achevait la Seconde Guerre mondiale. La Georgie était alors championne de la ségrégation raciale : avec une misère endémique et la récurrence d’atroces crimes racistes impunis, la vie des Afro-américains y était aussi misérable que dangereuse et désespérante. James a été renvoyé de l’école en raison de ses haillons trop « indignes ». Aux États-Unis une personne mal habillée, qui sent mauvais et traîne dans les rues est qualifiée de «funky», un terme également synonyme d’authen-ticité et de ressenti dans le jazz d’après-guerre.

Malgré les mises en garde de son cousin qui venait de quitter la ville, James commit quelques vols pour pouvoir s’habiller décemment. Arrêté pour tentative de vol de voiture, il fut condamné à seize ans de prison ferme. Incarcéré en prison puis au Georgia Juvenile Institute à l’âge de seize ans, l’adolescent devint boxeur et joueur de base-ball. Leader naturel à la forte personnalité, James se consacra à chanter le gospel avec une formation de détenus. C’est à un match de base-ball auquel il assista pendant sa détention qu’il rencontra le pianiste Bobby Byrd, déjà professionnel dans un groupe de gospel et un autre de rhythm and blues. Ces activités sportives, spirituelles et musicales ont forcé le respect de ses geôliers, son autorité et sa popularité dans la prison lui valant d’être bien noté. Il n’avait pas encore vingt ans quand, après avoir purgé trois ans et un jour de prison, il fut libéré pour bonne conduite, la famille de Bobby Byrd se portant garante de lui. Sa libération conditionnelle lui interdisait de remettre les pieds à Augusta.

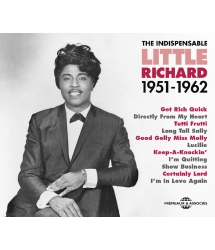

Libre, James Brown jouait beaucoup au base-ball. Il a été accueilli chez Bobby Byrd, qui comprenait son talent et insistait pour l’engager dans son groupe de R&B. Mais James ne voulait chanter que du gospel. Il était capable de mettre les églises en transes et se maria avec une fervente pratiquante qui l’avait vu à l’œuvre. Il abandonna la boxe après une défaite et travailla comme vendeur de voitures, puis dans une fabrique de matières plastiques tout en construisant sa réputation dans les églises baptistes au sein des Ever Ready Gospel Singers. James Brown rejoint finalement le groupe de son ami Bobby Byrd, les Gospel Starlighters, un groupe vocal dans la tradition des jubilee groups1. On peut entendre cette forte identité gospel, avec son intensité particulière dans la voix et les appel-réponses des chœurs sur ce qui, en 1956, deviendra leur premier disque, l’énorme succès rhythm and blues Please Please Please (dérivé du « Baby Please Don’t Go » du groupe vocal The Orioles). D’autres titres des débuts portent cette couleur gospel très marquée, comme Let’s Make It, I Want You So Bad ou I Feel That Old Feeling Coming On. Car leur répertoire s’élargit vite aux chansons de R&B à la mode au début des années 1950. Sous le nom des Avons ils interprétaient initialement des morceaux de Hank Ballard & the Midnighters, Roy Brown, des Clovers, Five Royales, Spaniels et trouvaient ainsi des engagements pour des soirées dansantes. James a appris le piano boogie-woogie et quand les Avons ont vu l’hystérie féminine provoquée par Hank Ballard sur scène, ils décidèrent de se consacrer pleinement au rhythm and blues et de composer des chansons. James était aussi très influencé par le hurleur Roy Brown, premier chanteur à vérita-blement apporter l’influence gospel dans le style R&B dès les années d’après-guerre (« Good Rocking Tonight », 19472). Rebaptisés The Flames, le groupe a tourné en Georgie tant bien que mal. Little Richard, un autre hur-leur originaire de la région lui aussi venu du gospel, n’avait pas encore sorti son premier succès quand les Flames ont sauté sur scène à l’improviste pendant l’entracte de l’un de ses concerts. Little Richard a apprécié la surprise et leur présenta son manager, qui les engagea dans sa boîte de Macon. Little Richard, bientôt appelé vers les grandes scènes nationales avec le succès énorme de « Tutti Frutti2 » en 1955, n’était plus en mesure d’honorer ses engagements locaux. Les Flames, rebaptisés les Famous Flames par leur nouveau manager, le remplacèrent à Macon. C’est pendant cette période que James Brown mit sa voix rauque plus en avant encore, utilisant des techniques vocales issues du gospel comme les cris et apostrophes qui deviendront sa marque de fabrique – et qui le faisait ressembler à Little Richard. On peut l’entendre ici chanter Chonnie-on-Chon à ses débuts dans un style rock and roll proche de Little Richard. Il développa aussi sa dimension scénique, répétant inlassablement avec ses musiciens et travaillant un très populaire numéro de danseur qui influencera profondément quantité de musiciens importants, de Jackie Wilson à Michael Jackson ou Prince, qui lui doivent tant. Une maquette de Please Please Please circula et convaincut instantanément les disques King, qui publiaient déjà les enregistrements de Hank Ballard et Little Willie John, d’autres pionniers de la soul.

Soul Music

Avec l’influence d’autres précurseurs de la soul music, comme Esther Phillips, Little Willie John, Clyde McPhatter ou Hank Ballard, le rhythm and blues était en train de changer, l’originalité et l’émotion transmise par l’interprétation prenant de plus en plus de place. Si le chanteur Solomon Burke (« Everybody Needs Somebody to Love ») s’est attribué l’étiquette soul dès 1961, la musique soul n’adoptera véritablement ce nom qu’à partir de 1964. Que la racine soit blues, jazz, jump blues ou gospel, on parlait auparavant de rhythm and blues. Jusque-là, le terme « soul » était lié au gospel (comme les Soul Stirrers de Sam Cooke) et à un type de jazz « hard bop » apparu au milieu des années 1950. La vague du bebop, style virtuose, difficile, mené par Charlie Parker, avait libéré le jazz des carcans du swing, de la piste de danse et ébloui l’après-guerre par ses extraordinaires improvisations. Mais aussi brillant et révolutionnaire fût-il, l’art du bop était un peu abstrait, déconnecté du grand public. Vers 1955 certains musiciens comme Horace Silver, Bobby Timmons ou Cannonball Adderley ont voulu retrouver les racines du jazz, c’est à dire le gospel et le blues, frères ennemis au sein d’une même communauté. Le blues, individualiste, à la réputation sulfureuse, était l’anti-thèse du gospel unificateur, spirituel et bien-pensant. L’un comme l’autre transmettent des émotions, mais le gospel et les spirituals étaient depuis longtemps la force dominante à la racine de toutes les musiques afro-américaines. Le gospel était interprété avec ferveur par la quasi-totalité des Afro-américains qui, depuis l’abolition de l’esclavage, avaient structuré leur communauté martyrisée et leur culture autour des églises. L’adjectif « soul » était donc associé à un jazz bien senti, bluesy, avec une sensibilité gospel qui touchait le cœur plus que le mental. Pour décrire un jazz pourvu de ces qualités, on utilisait jusque-là le terme « funk » ou « funky », un mot associé à la crasse, la sexualité, les odeurs corporelles : « Blue Funk » de Ray Charles et Milt Jackson en 1957 ou encore le « Funky Blues » de 1952 avec Johnny Hodges, Charlie Parker, Oscar Peterson, Ben Webster, etc.

À partir du milieu des années 1950, le mot soul (« âme »), qui fait directement allusion au gospel, a commencé à remplacer l’adjectif « funky ». En 1955 Ray Charles enregistrait « A Bit of Soul » et en 1956 «Houseful of Soul » ; Puis son « Soul Meeting3 » jazz gravé en 1958 avec Milt Jackson.

Mais plus encore que ces étiquettes, l’influence du gospel lui-même a réellement commencé à percer dans la musique populaire américaine, entendez la musique commerciale. Après « I Got a Woman », 1956 est l’année où Ray Charles publia « Drown in my Own Tears », deux énormes succès pétris dans la matrice gospel. Et c’est un autre chanteur de gospel précurseur de la soul, Sam Cooke, qui enregistra « Wonderful » et « I’ll Come Running Back to You » en opérant lui aussi sa sortie du monde gospel pour se consacrer au R&B. Le 4 février 1956, avec un son plus cru James Brown and His Famous Flames firent de même. Ils enregistrèrent leur premier classique, Please Please Please au studio King de Cincinnati (Ohio). James y supplie une femme de ne pas le quitter, un thème plutôt ordinaire, mais qu’il interprète de façon éblouissante avec l’intensité et les techniques du chant gospel. Sorti le 3 mars 1956 sur la sous-marque Federal de la maison King, le disque se vendra à plus d’un million d’exemplaires.

The Famous Flames

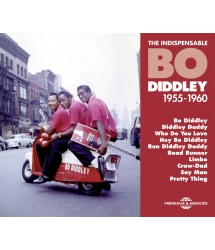

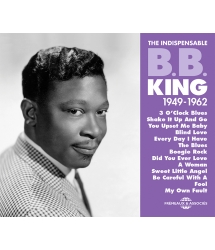

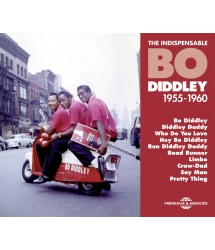

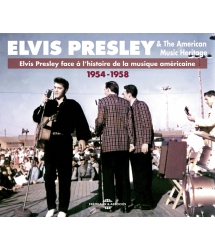

Sid Nathan, le patron des disques King, n’appréciait pas James Brown et son gospel métamorphosé en R&B. Il ne croyait pas à son avenir. Pour ne rien arranger, le groupe vocal n’a pas apprécié que le disque sorte sous le nom de James Brown & His Famous Flames, et tout le monde a laissé tomber le chanteur. Tout de même sollicité à la suite de ce succès soudain, James engagea des musiciens et parvint à donner des concerts dans les réseaux afro-américains, le fameux chitlin’ circuit : le chitterling (ou chitlin’) est une recette populaire à base de tripes de porc. Les esclaves se nourrissaient des abats et rebuts des maîtres et le chitterling de la soul food est devenu tellement emblématique de l’identité afro-américaine que, servi dans les juke-joints, il a donné son nom au réseau des concerts R&B. D’autres morceaux enregistrés en 1956-57 feraient l’objet de singles, mais aucun des huit 45 tours suivants n’aura de succès. L’originalité et la magie de Please Please Please n’étaient pas au rendez-vous. James Brown produisait un rhythm and blues splendide auquel il manquait sans doute une pincée de sel pendant cette période très concurrentielle, particulièrement créative, où des milliers de disques afro-américains remarquables se disputaient le succès. La période 1956-1958 a été marquée par l’âge d’or du rock and roll avec la déferlante Bo Diddley4, Chuck Berry, Little Richard et des artistes blancs comme Elvis Presley5, Gene Vincent ; des groupes vocaux comme les Drifters, les Coasters, les Platters occupaient beaucoup de terrain, et le blues électrique connaissait lui aussi une période faste avec Howlin’ Wolf, B.B. King, Muddy Waters, John Lee Hooker et tant d’autres. Sans oublier l’énorme succès des précurseurs de la soul comme Clyde McPhatter, Ray Charles, Hank Ballard, Jackie Wilson, Sam Cooke, Little Willie John… malgré les difficultés, James Brown est parvenu à persévérer grâce à son caractère d’acier – et à un coup de main des Upsetters, le groupe de Little Richard qui en 1957 avait abandonné le rock pour se consacrer à la religion. James Brown l’a remplacé nombre de fois en engageant une partie des Upsetters. Il avait goûté au succès, et il n’était pas question qu’il retourne d’où il était venu.

Déjà devenu un extraordinaire homme de scène, il lui faudra attendre septembre 1958 avant d’enregistrer son second tube, le très gospel Try Me. Dans le même esprit que Please Please Please, entre janvier 1959 et février 1961 ce morceau ouvre la voie à pas moins de onze succès. Avec des musiciens hors-pair, un groupe vocal chevronné et un style de plus en plus affirmé, James Brown and His Famous Flames parviennent à capturer l’ambiance électrique de leurs spectacles et à la restituer sur des 45 tours. Un nouveau son James Brown a surgi, imbibé de gospel et de soul. L’équipe s’éloigne peu à peu de ses influences des débuts et transcende les styles. Ni rock, ni doo wop, ni gospel, ni blues, leur formule R&B est tout ça à la fois, mais reste unique. Servi par une remarquable interprétation, I’ll Go Crazy est l’un des tours de force des Famous Flames, leur troisième succès important. Puis ce sont Think, au son moins bien enregistré et This Old Heart avec ses rythmes de saxophone discordants, dont la prise de son laisse aussi à désirer. Sur The Bells, une reprise de Clyde McPhatter & The Dominoes qui met en scène un décès, James s’effondre en larmes et sanglote. Citons encore Baby You’re Right sur une suite d’accords gospel où il fait déraper sa voix comme des pneus sur l’asphalte, annonçant son style à venir ; et l’impressionnant I Don’t Mind, où l’interaction entre les chœurs et la formidable interprétation crée un style de balade qui deviendra vite l’un des canons des années soixante. Puis c’est l’impeccable Just You and Me Darling, la voix torturée de Lost Someone et l’énorme succès Night Train, un instrumental agrémenté de quelques cris indiquant des localités américaines. Shout and Shimmy, un morceau pour chauffer les salles, moins subtil, a été enregistré avec un égal soin. Sans arrêt sur scène, James Brown infligeait sans pitié des répétitions permanentes à ses musiciens, ce qui assurait un niveau de professionalisme sans égal pour un groupe de rock/rhythm and blues à cette époque. La précision était égale en studio et sur scène, où James développait de nouveaux pas de danse-éclair à couper le souffle, toujours habillé avec élégance et recherche, coiffé d’une banane élaborée… le spectacle atteignait son paroxysme quand il feignait de s’effondrer, en nage, épuisé et qu’un MC venait le couvrir d’une cape pailletée avant de guider ses pas vers les coulisses. Dès le début des années soixante, la James Brown Revue invitait des artistes venus chanter en première partie leur seul succès - voire deux chansons - des danseuses, comédiens. Le groupe hors du commun, qui reste l’un des plus mémorables de l’histoire de la pop music, enchaînait ensuite succès sur succès avec une frénésie et un dynamisme irrésistible. Ce triple album contient tous les indispensables enregistrements en studio de l’éclatante première période de James Brown, celle du pur rhythm and blues venu de l’école gospel. La deuxième période de la carrière de James Brown commencera ensuite, en 1962 avec un album enregistré au légendaire Apollo de Harlem, qui lancera véritablement sa période soul.

Bruno BLUM

© FRÉMEAUX & ASSOCIÉS 2012

Remerciements à Gilles Pétard.

Notes

1. Écouter Gospel Quartets 1921-1942 (FA 026) et Golden Gate Quartet - Gospel 1937-1941 (FA 002) dans cette collection.

2. Écouter les versions originales de « Good Rocking Tonight » (1947) par Roy Brown et de « Tutti Frutti » par Slim & Slam (1938) et Little Richard (1955) sur l’album Elvis Presley face à l’histoire de la musique américaine - 1954-1958 (FA 5361) dans cette collection.

3. Écouter l’album de Ray Charles Brother Ray: The Genius - 1949-1960 (FA 5350) dans cette collection.

4. Écouter l’album Bo Diddley – The Indispensable - 1955-1960 (FA 53756) dans cette collection.

5. Écouter l’album Elvis Presley face à l’histoire de la musique américaine - 1954-1958 (FA 5361) dans cette collection.

Funky

Born in a miserable shack deep inside the South Carolina woods – no water, no electricity – James Joseph Brown (May 3rd 1933 – December 25th 2006) was abandoned by his parents when he was four. His mother went looking for the better things in life up north… and James was raised by his father, a half-African/half-Apache with a drop of Asian blood in his veins who tried to earn a living tapping resin from trees. But when that didn’t suffice he joined the Navy – he was the next to abandon his son – and James was taken in by his aunt Honey, who ran a brothel and raised him in a place which already housed twelve others. James and his cousin – he was a year older – went barefoot, and not just in the summer: they had to steal coal from the railroad tracks just to warm the house. They shined shoes in the street and used the ploy to lure soldiers into the family whorehouse. That was how James Brown learned to dance: by attracting GIs to earn a few cents. This sordid context was to produce one of the greatest musicians of the 20th century, the man who would be the precursor and later the uncontested King of Soul and Funk, a composer, arranger, singer/dancer/bandleader who became an absolute stage-performer with a definitive influence on almost everyone who came after him, and then some, whatever the domain: not only R&B, soul and funk but also reggae, rap and hip hop.

Gospel

James Brown was a loner and spent a lot of time in the streets. But he was resourceful and determined to succeed: he joined the Cremona Trio as a singer when he was twelve, and was giving his first concerts by the time war came to a close. It was a period when Georgia had the unenviable reputation of being the N°1 State for racial segregation, and its endemic misery – combined with an atrociously high rate of unpunished racist crimes – made life for Afro-Americans as desperate as it was dangerous. James was thrown out of school because his tattered clothes made him «unworthy» of an education… This was an America where someone who «dressed badly» and «didn’t smell nice» was (pejoratively) considered «funky», especially if he spent more time in the street than at home. But fortunately, the term «funk» was also a synonym for «authenticity» and «feeling» in post-war jazz… Even so, despite the warnings he’d received from his cousin before the latter left town, James resorted to theft so that he could dress «decently»; arrested for stealing an automobile, he was sentenced to sixteen years in jail without remission. He was incarcerated, and at the age of sixteen he was transferred to the Georgia Juvenile Institute – he was as old as his prison-term – where his strong character made him a natural leader. He devoted himself to singing gospel with a prison choir, and turned to boxing and baseball for recreation. It was while he was watching a baseball game that he met pianist Bobby Byrd, who was already a professional with one gospel group while playing in another band whose music was rhythm & blues. James’ activities – sporting, spiritual and musical – earned him the respect of his jailers, and his authority and popularity amongst other prisoners were rewarded with points for good conduct. Before he turned twenty, James was released (after three years and one day) into the care of Bobby Byrd’s family… on condition that he never set foot in Augusta, Georgia again.

James Brown played a lot of baseball as a free man; Bobby Byrd’s family welcomed him into their home, and Bobby understood his talents enough to recommend that he join his R&B group. James, however, only wanted to sing gospel: he could send whole congregations into a trance, and he married a fervent worshipper who’d witnessed his singing at first hand. He gave up boxing after losing a match and became an automobile-salesman before working in a plastics factory, all the time building himself a reputation in Baptist churches with the Ever Ready Gospel Singers. When he was ready, James finally joined his friend Bobby Byrd’s group The Gospel Starlighters, a vocal ensemble in the jubilee group tradition1. You can hear his strong gospel-identity – with that particular intensity in his vocals and the call-and-response exchanges of the chorus – in their first record (1956) which became a huge rhythm & blues hit, Please Please Please (derived from The Orioles’ «Baby Please Don’t Go»). Other hits from his early years also carry that marked gospel colour, like Let’s Make It, I Want You So Bad or I Feel That Old Feeling Coming On. Their repertoire quickly grew to include fashionable R&B songs from the early Fifties. As The Avons, they began singing pieces by Hank Ballard & The Midnighters, Roy Brown, The Clovers, The Five Royales and The Spaniels, and they found bookings to appear at dances. James had learned to play boogie-woogie piano, and as The Avons saw women go into hysterics when they saw Hank Ballard take the stage, they decided to drop everything in favour of R&B and began writing songs of their own. James was also highly influenced by Roy Brown, whose florid, pleading vocal style made him the first singer to bring a genuine gospel influence to the R&B of the post-war years (cf. «Good Rocking Tonight», 1947)2. Rechristened The Flames, the group went on tour in Georgia…

Little Richard, another shouter from the south (also coming from gospel), hadn’t yet released his first hit when The Flames spontaneously leaped on stage during the interval at one of his concerts. Little Richard liked the surprise and introduced them to his manager, who promptly gave them a gig at his own club in Macon; when the enormous success of «Tutti Frutti»3 in 1955 gave Little Richard many international opportunities, he was no longer able to honour his local gigs and The Flames – rechristened The Famous Flames by their new manager – replaced Little Richard in Macon. It was at around this time that James Brown began placing his raucous voice more «upfront», using the gospel vocal techniques – yells and the use of apostrophe would become his signature – that gave him a «Little Richard-sound». Here you can listen to him in those days singing Chonnie-on-Chon, in a rock ‘n’ roll style close to that of Little Richard. James also developed his stage dimension, tirelessly rehearsing with his musicians to perfect a popular dance-routine that would have a deep influence on many major artists from Jackie Wilson to Michael Jackson or Prince, all of whom owed much to James Brown. A demo of Please Please Please was circulated and it immediately convinced King Records, a label which was already issuing records by two other soul pioneers, Hank Ballard and Little Willie John.

Soul Music

Under the influence of soul music’s precursors – Esther Phillips, Little Willie John, Clyde McPhatter, Hank Ballard – rhythm and blues was changing: the originality and emotion communicated by performers was occupying more and more space. While singer Solomon Burke («Everybody Needs Somebody to Love») had given himself a Soul label as early as 1961, Soul Music only became known as such from 1964 onwards. Whether its roots lay in blues, jazz, jump blues or gospel, up until then people spoke only in terms of rhythm and blues. The term Soul had been tied to gospel (cf. Sam Cooke’s Soul Stirrers), and to a kind of hard-bop jazz which appeared in the mid-Fifties: the bebop craze, brought on by the virtuoso, complex style of Charlie Parker and his kind, had freed jazz from the codes of swing and dance-halls, and it dazzled the post-war generation with its extraordinary improvising. But, as brilliant and revolutionary as it was, the art of bop seemed rather abstract to mass audiences and they remained disconnected from it. Towards 1955, some musicians – Horace Silver, Bobby Timmons and Cannonball Adderley – sought to return to those roots of jazz which rivalled each other within the same community, i.e. gospel and blues. Blues, that individualistic form with an air of heresy about it, was the antithesis of unifying, spiritual, God-fearing Gospel. Both were vehicles for emotion, but gospel and spirituals had long been the dominant forces at the root of all Afro-American music. Gospel was sung with fervour by almost all Afro-Americans who, ever since the abolition of slavery, had structured their martyred community and culture around the Church. So the «soul» adjective was associated with a kind of heartfelt jazz that was bluesy: its gospel feeling touched the heart rather than the mind. Up until then, the kind of jazz which didn’t lack any of those qualities had been described as «funk» or «funky», terms associated with dirt, sex and body-odour: there was «Blue Funk» by Ray Charles and Milt Jackson in 1957, for example, and before that (1952) there was «Funky Blues» with Johnny Hodges, Charlie Parker, Oscar Peterson, Ben Webster etc.

Beginning in the mid-Fifties, the word soul, a direct allusion to gospel, appeared as a replacement for the adjective «funky». In 1955 Ray Charles recorded «A Bit of Soul», and then «Houseful of Soul» in 1956; and in 1958 there was his «Soul Meeting»3 jazz record with Milt Jackson.

But, apart from such labelling-considerations, it was the influence of gospel music itself which really began to break into American popular (i.e. «commercial») music: after «I Got a Woman», 1956 was the year when Ray Charles released «Drown in My Own Tears», and both were enormous hits nurtured in the gospel matrix. Another gospel singer/soul precursor was Sam Cooke, who recorded «Wonderful» and «I’ll Come Running Back to You»: he, too, was emerging from the gospel universe to devote himself to R&B. On February 4th 1956, James Brown and His Famous Flames did the same, only the sound wasn’t as suave… They recorded their first classic Please Please Please at the King studios in Cincinnati, Ohio. Just take a listen: the theme – asking your woman not to leave you – might be ordinary, but James begs and implores her not to go with all the dazzlingly intense technique of the great gospels. King released the record on March 3rd 1956 on its subsidiary label Federal, and it sold more than a million copies.

The Famous Flames

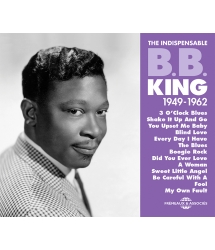

Sid Nathan, who ran King Records, didn’t appreciate James Brown and his gospel-metamorphosis/R&B. He didn’t believe he had a future. To make matters even less simple, the vocal group didn’t like it when the record was released under the name «James Brown & His Famous Flames», and so they wrote him off as their singer. It didn’t make much difference once the record was a hit: James was in great demand and he hired other musicians to take with him on the famous chitlin’ circuit, that string of venues named after the Southern meal called chitterlings (or pork-intestines, sometimes called tripe when cooked). Slaves ate tripe and other leftovers, and the soul-food chitterlings that came to symbolise the Afro-American identity were served up in juke-joints across the country; it was an ideal name for a venue-circuit where R&B was on the menu… Other pieces recorded in 1956-57 became singles, but none of the eight 45rpm records released later enjoyed as much success: the originality and magic of Please Please Please was lacking. James Brown was producing a splendid brand of rhythm and blues, but it no doubt needed a pinch of salt in that highly competitive period; they were particularly creative times, and thousands of Afro-American recordings were queuing up to be hits. The 1956-58 period was rock ‘n’ roll’s Golden Age, with a tidal wave of artists whose names were Bo Diddley4, Chuck Berry and Little Richard, not to mention white artists like Elvis Presley5 and Gene Vincent; vocal groups like The Drifters, The Coasters and The Platters were also gaining a strong foothold, and it was a particularly rich period for electric blues thanks to Howlin’ Wolf, B. B. King, Muddy Waters, John Lee Hooker and many others. And if you thought the soul precursors had been forgotten, Clyde McPhatter, Ray Charles, Hank Ballard, Jackie Wilson, Sam Cooke and Little Willie John were still successful… The situation was difficult but James Brown persevered thanks to his iron will and… a little help from The Upsetters, the group behind Little Richard, who gave up rock in 1957 to devote himself to The Lord: James Brown replaced him on many occasions when he hired members of The Upsetters. He’d tasted success, and there was no going back.

He was already an extraordinary stage-performer, but James had to wait until September 1958 to record his second hit, the (very) gospel song Try Me. This piece – it has the same spirit as Please Please Please – opened the way for no fewer than eleven hits between January 1959 and February 1961. With excellent musicians, a reputed vocal group and a style that constantly matured, James Brown and His Famous Flames succeeded in capturing the electric atmosphere of their shows, and they reproduced that on record. A new James Brown sound rose up, and it was steeped in gospel and soul. The outfit gradually drew away from its initial influences to transcend all styles: Rock, doo wop, gospel, blues… The band’s R&B formula was none of them and yet all of them: it was unique. Served by a remarkable performer, I’ll Go Crazy is a Famous Flames masterpiece, the group’s third major hit; it was followed by Think, which was technically not very well recorded, and This Old Heart with its dissonant saxophone-rhythms (the sound of the take left something to be desired also). On The Bells, a reprise of the Clyde McPhatter & The Dominoes song which had a sad demise as its theme, James Brown breaks down in tearful sobs. There was also Baby You’re Right, based on a succession of gospel chords over which his voice skids like a tyre in a fast bend, announcing the style to come; the impressive I Don’t Mind produced a ballad-style – created by the interaction of the chorus with James’ formidable voice – which quickly became a Sixties code. And then we have the impeccable Just You and Me Darling, the tortured voice of Lost Someone and the enormous hit Night Train, an instrumental embellished with shouts of American place-names… And just as much care was taken over the recording of Shout and Shimmy, a less subtle piece that was perfect for warming up an audience…

James Brown never took a breather: he was always onstage. He mercilessly inflicted rehearsals on his musicians – permanent repeated exercise – and the result was a level of professionalism without parallel among rock/R&B groups of the period. That precision was present in the studio and onstage, where James developed new dance-routines – executed with breath-taking speed by a careful, elegant dresser who would appear wearing an ornate pompadour on his head… The show reached its paroxysm when he pretended to faint, steaming in sweat and exhausted to the point where an MC had to wrap him in a spangled cape before escorting him into the wings. By the early Sixties, the James Brown Revue was inviting artists to come and sing their only hit – sometimes two songs – as openers for James’ show; there were dancers, comedians…. This uncommon troupe – it remains one of the most memorable in pop-music history – would then launch into hit after hit in a dynamic frenzy that was irresistible. This triple album contains all the indispensable studio-recordings dating from that first, shattering James Brown era, the period featuring pure rhythm and blues from the gospel school. The second great phase in James Brown’s career would begin in 1962, with an album he recorded at the legendary Apollo in Harlem; it launched his Soul years.

Bruno BLUM

Adapted in English by Martin DAVIES

© Frémeaux & Associés 2012

With thanks to Gilles Pétard.

Notes

1. Listen to Gospel Quartets 1921-1942 (FA 026) and Golden Gate Quartet - Gospel 1937-1941 (FA 002) in this collection.

2. Listen to the original versions of Good Rocking Tonight (1947) by Roy Brown and Tutti Frutti by Slim & Slam (1938) and Little Richard (1955) on the album Elvis Presley & the American Music Heritage: 1954-1958 (FA 5361) in this collection.

3. Listen to the Ray Charles album Brother Ray: The Genius, 1949-1960 (FA 5350) in this collection.

4. Listen to the album Bo Diddley – The Indispensable, 1955-1960 (FA 5376) in this collection.

5. Listen to the album Elvis Presley face à l’histoire de la musique américaine - 1954-1958 (FA 5361) in this collection.

DISCOGRAPHIE CD 1

1. Please Please Please

2. I Feel That Old Feeling Coming On

3. Why Do You Do Me (Like You Do)

4. I Don’t Know

James Brown & His Famous Flames: James Brown-v; Bobby Byrd, Johnny Terry, Nashville Knox, Sylvester Keels-v; Ray Felder-as; Clifford Scott, Wilbert Smith-ts; Bobby Byrd-p; Nafloyd Scott-g; Clarence Mack-el. b; Edison Gore-d. King Studios, Cincinnati, February 4, 1956.

5. I Walked Alone

6. No, No, No, No

7. You’re Mine, You’re Mine

8. Hold my Baby’s Hand

9. Chonnie-on-Chon

10. I Won’t Plead No More

James Brown-v; Bobby Byrd, Johnny Terry, Nashville Knox, Sylvester Keels-v; Ray Felder, Cleveland Love-as; Alvin Gonder aka Fats-p; Nafloyd Scott-g; Clarence Mack-b; Reginald Hall-d; Gene Redd-arr. King Studios, Cincinnati, March 27, 1956.

11. Just Won’t Do Right

12. Let’s Make It

13. Gonna Try

14. Can’t Be the Same

Same as 10 except 14, vocal duet with Bobby Byrd. Other vocalists out. Cincinnati, July 24, 1956.

15. Messing with the Blues

16. Fine Old Foxy Self

17. Love Is a Game

18. Why Does Everything Happen to Me

(Strange Things Happen)

James Brown-v; John B. Brown-as; Cleveland Love-ts; Eddie Freeman or Nafloyd Scott-g; Bobby Byrd-p; Alvin Gonder aka Fats-p; Edwyn Conley-b; Reginald Hall-d; unkown-vocal group. King Studios, Cincinnati, April 10, 1957.

19. Begging, Begging

20. Baby Cries Over to the Ocean

James Brown-v; Bill Hollings-v; Louis Madison-bck v, org or Alvin Gonder aka Fats-p; Guitar Gable, John Faire or Bobby Roach-g; Baroy Scott-el. b; «Tee» or Edison Gore-d. King Studios, Cincinnati, October 21, 1957.

DISCOGRAPHIE CD 2

1. Try Me

2. Tell Me What I Did Wrong

James Brown-v; Johnny Terry, Bill Hollings, Louis Madison aka JW-bck v; George Dorsey-as; Clifford Scott-ts; Ernie Hayes-bs; Kenny Burrell or Bobby Roach-g; Alvin Gonder aka Fats or Gene Redd-p; Carl Pruitt-el. b; Panama Francis-d; Gene Redd-arr. Beltone Studios, New York, September 18, 1958.

3. That’s When I Lost my Heart

4. That Dood It

Same as CD1, tracks 19-20.

5. There Must Be a Reason

6. I’ve Got to Change

Same as CD2, tracks 1-2.

7. Got to Cry

8. It Was You

9. I Want You So Bad

10. It Hurts to Tell You

James Brown-v; Lee Diamond, JC Davis-ts; Alvin Gonder aka Fats-p, org; Bobby Roach-g; Bernard Odum-el. b; Charles Conner-d; bck v. same as CD2, tracks 1-2. Horns out on 10. Masters Studios, Los Angeles, December 18, 1958.

11. Don’t Let it Happen to Me

12. Bewildered

Same as CD2, tracks 7-10 except Charles Connors or Nat Hendricks (d) and unknown tpt added. Horns out on 12.

Beltone Studios, New York, January 20, 1959.

13. Good Good Lovin’

James Brown-v; James McGary-as; JC Davis-ts; Alvin Gonder aka Fats-org; Bobby Byrd-p; Bobby Roach-g; Bernard Odum-el. b; Nat Kendricks-d. King Studios, Cincinnati, June 27, 1959.

14. Wonder When You’re Comin’ Home

15. I’ll Go Crazy

16. This Old Heart

17. I Know It’s True

Same as CD2 track 13 except Sonny Thompson-p replaces Gonder and Byrd. King Studios, Cincinnati, November 11, 1959.

18. Think

19. I’ll Never, Never Let You Go

20. You’ve Got the Power

James Brown-v; Bea Ford-v on 20; Bill Hollings, Johnny Terry, Bobby Byrd-v, p on 20; JC Davis, possibly St. Clair Pinkney-ts; unknown-tp on 20; Bobby Roach-g; Bernard Odum-el. b; Nat Kendricks or Clayton Filyard-d. All vocals out on 20 except Brown and Ford. United Recording Studios, Hollywood, February 20, 1960.

DISCOGRAPHIE CD 3

1. I Don’t Mind

2. If You Want Me

3. Baby You’re Right

4. Love Don’t Love Nobody

James Brown-v, p on 1; Bill Hollings, Johnny Terry, Bobby Byrd-p on 1; Alfred Corley-as; JC Davis-ts; Roscoe Patrick---tp; Bobby Byrd-p on 3; Les Buie-g; Hubert Perry-el. b; Nat Kendricks-d. Masters Studios, Los Angeles, September 27, 1960.

5. Come Over Here

6. And I Do Just What I Want

7. Just You and Me, Darling

8. So Long

Same as 1-4 with Byrd-p on 8, bck v out on 6. Masters Studios, Los Angeles, September 29, 1960.

9. Tell Me What ‘Cha Gonna Do

10. The Bells

11. Hold It

Same as 1-4, bck v out. Masters Studios, Los Angeles, October 4, 1960.

12. Dancing Little Thing

13. You Don’t Have to Go

14. Lost Someone

15. Shout and Shimmy

16. Night Train

James Brown-v, org on 16; JC Davis, St. Clair Pinkney-ts; Al Clark aka Brisco -bs; possibly Alfred Cauley-sax; Bobby Byrd or Alfred Gonder aka Fats-el. p; Bobby Roach-g; Bernard Odum-el. b; Nat Kendricks-d; Bobby Byrd, Lloyd Stallworth, Bobby Bennett or Johnny Terry-bck v; Bck v out on 16. King Studios, Cincinnati, February 10, 1961.

17. (I Love You) Yes I Do

James Brown-v; St. Clair Pinkney-ts; Bobby Byrd-org; Bernard Odum-b; Nat Kendricks-d. King Studios, Cincinnati, February 1961.

18. Have Mercy Baby

19. Just Won’t Do Right

James Brown-v; Bobby Byrd-v on 19; St. Clair Pinkney-ts; Al Clark aka Brisco-bs; Roosevelt Brown-tp; Alfred Gonder aka Fats-org; Les Buie-g; H. Perry-el. b; Nat Kendricks-d; Dukoff Studios, Miami, June 9, 1961.

CD JAMES BROWN THE INDISPENSABLE 1956-1961, JAMES BROWN © Frémeaux & Associés 2012 (frémeaux, frémaux, frémau, frémaud, frémault, frémo, frémont, fermeaux, fremeaux, fremaux, fremau, fremaud, fremault, fremo, fremont, CD audio, 78 tours, disques anciens, CD à acheter, écouter des vieux enregistrements, albums, rééditions, anthologies ou intégrales sont disponibles sous forme de CD et par téléchargement.)