- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

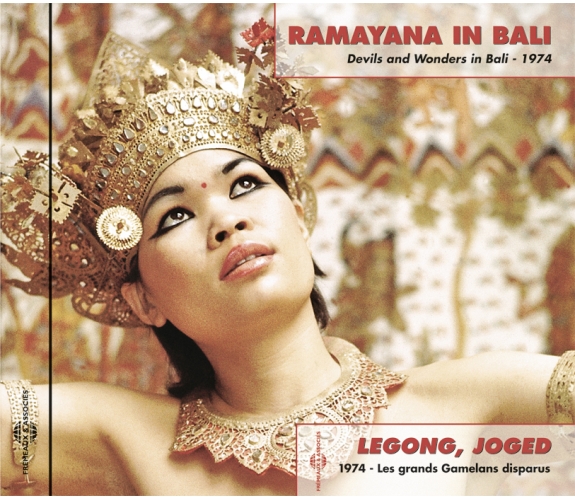

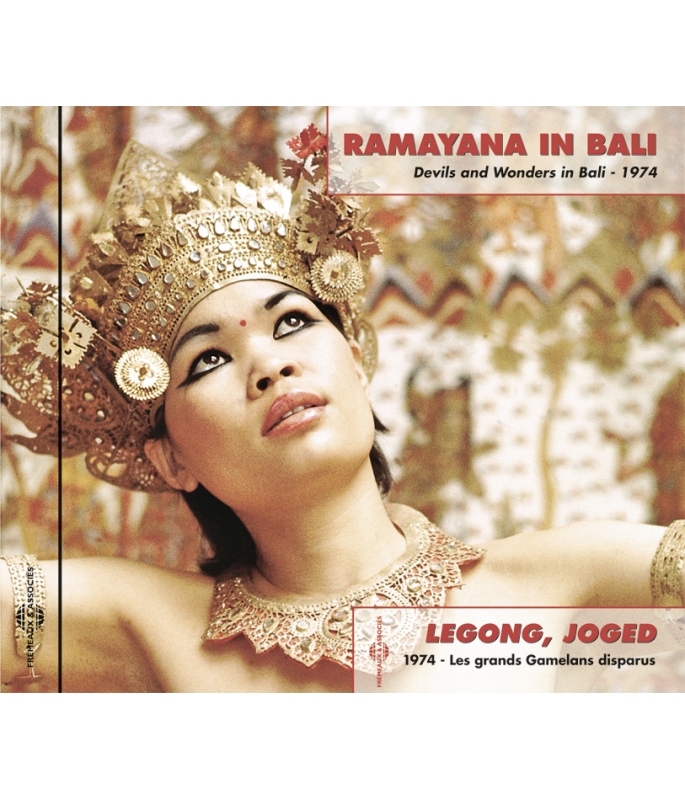

DEVILS AND WONDERS IN BALI

Ref.: FA5293

EAN : 3561302529325

Artistic Direction : FRANCOIS JOUFFA

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Total duration of the pack : 1 hours 5 minutes

Nbre. CD : 1

DEVILS AND WONDERS IN BALI

DEVILS AND WONDERS IN BALI

“Music is in Bali what meditation is to religion. It is part of all social events as well as of religious and theatrical ones, the whole participating to the same everyday magic. To discover the heart of Bali, and understand the soul of its inhabitants, just follow the musical journey that leads to a set of gamelans to another and keep your ears wide opened to its charm if not its enchantment”, explains François Jouffa. In 1974, the ethnomusicologist recorded a sound culture that is now about to disappear: the gamelans (Balinese orchestras). His recordings allow the listener a priviledged access to the greatest treasures of the island’s traditions: the Ramayana, as well as the Legong and Joged dances. A legacy kept in memory by all of the visitors of the famous Hindu island of Indonesia. P. Frémeaux & C. Colombini

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Enlèvement de SitaEnsemble Semara Budava00:05:201975

-

2Duel entre Ravana et JatayuEnsemble Semara Budava00:09:581975

-

3Préparation aux bataillesEnsemble Semara Budava00:16:431975

-

4TabuhTraditionnel00:06:171975

-

5BarisTraditionnel00:03:451975

-

6Oleg TambulilingaTraditionnel00:04:091975

-

7Raja PalaTraditionnel00:02:081975

-

8Tari TenunTraditionnel00:01:571975

-

9Panji SemirangTraditionnel00:05:021975

-

10Tabuh - Tari Nalayan - Mergapati - JogedTraditionnel00:09:451975

Le RAMAYANA A BALI

Le RAMAYANA A BALI

1974 - Les grands Gamelans disparus

Legong, joged

Devils and Wonders in Bali - 1974

“Les soupirs d’un instrument à vent prolongent des vibrations de cordes vocales avec un sens de l’identité tel qu’on ne sait si c’est la voix elle-même qui se prolonge ou le sens qui depuis les origines a absorbé la voix.”

Antonin Artaud, Le Théâtre balinais, 1931

“Le gamelan jouait ; un air doux et incertain alternait avec des notes vives, fortes et guerrières, que précipitaient les battements du tambour. Il aimait cette attente de la danse qui faisait courir de petits frissons sur sa peau.”

Vicki Baum, Sang et volupté à Bali, 1937

“L’orchestre qu’on appelle “gamelang”, comportait une quarantaine d’exécutants, accroupis devant les instruments (…), des lames d’acier vibrantes, des gongs de toutes sortes de tailles, alignés côte à côte et qui résonnent chacun selon une note unique, tout un ensemble très complexe et très riche qui suppose, au dire des musicologues, la connaissance avant la lettre des découvertes les plus hardies de la musique contemporaine en Europe.”

Roger Vailland, Boroboudour, voyage à Bali, Java et autres îles, 1951

“La gamelan balinais frappe de tous ses xylophones sur chaque fibre de notre sensibilité. C’est une “musique-expérience” qui fait appel à tout le corps : pas de sentiment, mais plutôt un contact, une symphonie sensuelle qui fait converger plusieurs cascades vers le même point.”

Merry Ottin et Alban Bensa, Le sacré à Java et à Bali, 1969.

“Sous le ciel devenu couleur d’encre claire, on ne distingue plus les visages des Balinais, émaciés, fondus dans la nuit. N’en reste plus que le blanc des yeux. Attente. Assis en rond. Petite musique stylisée du gamelan, discrets frétillements cuivrés à peine plus sonores que le vent dans les palmiers.”

Muriel Cerf, Le diable vert, 1975

Démons et merveilles à Bali

Bali fait partie des Petites îles de la Sonde. Sa superficie de 5 635 km2 (soit les 2/3 de la Corse). Sa population est passée de 2 à 3 millions d’habitants en 40 ans. Bali, dont la capitale est Denpassar, est l’une des provinces de la République d’Indonésie. Le nom Indonésie vient du latin Indus, Inde, et du grec nesos, île : 17 500 îles dont 3000 habitées (le plus grand archipel du monde) avec 240 millions d’habitants (le 4e pays le plus peuplé du monde). L’Indonésie est le plus important pays à majorité musulmane. Bali présente l’originalité d’être la seule île indonésienne à être essentiellement hindouiste, avec plus de 20 000 temples. Si le tourisme, culturel ou sportif (le surf), est l’une des activités économiques les plus importantes pour l’Indonésie, elle le doit principalement à Bali pour qui c’est la principale ressource. Le tourisme international, qui a débuté à Bali dès les années 1920, s’est intensifié à la suite de l’Exposition coloniale de Paris en 1931. L’artisanat, influencé par l’Islam en Indonésie, est restreint du fait que les représentations humaines et animales y sont interdites par la religion. Sauf à Bali, où les arts se sont développés grâce à un héritage d’art bouddhique et d’art hindouiste mélangés, sans compter les influences animistes. Les dépliants touristiques vendent/vantent Bali, comme étant le dernier paradis terrestre. On peut le croire aisément quand on assiste aux couchers de soleil sur les plages ou quand on se promène sur les flancs des collines vertes étagées en rizières, entrelacées de palmeraies et de cours d’eau dans lesquels se baignent, encore parfois, des hommes et des femmes nus. Les merveilles de la nature sont en harmonie avec les divinités et les démons de l’île. Car Bali est à la fois Paradis et Enfer. La lutte est constante entre le Bien et le Mal. Les forces bénéfiques, les dieux protecteurs du panthéon hindouiste et des traditions animistes, siègent au sommet des volcans sacrés. Les forces maléfiques, les vampires, ses sorcières, sont réfugiés au fond des mers. Pour réconcilier les deux extrêmes, les Balinais ont un calendrier des fêtes magiques et religieuses très chargé, et leurs offrandes sont destinées aux divinités bienfaisantes comme aux mauvais esprits ; l’équilibre cosmique est ainsi respecté, pour le respect de la nature comme pour le mental des humains. À Bali, les processions, les prières, les danses folkloriques ou classiques, toujours mythiques, les crémations comme les exorcismes sont soutenues par les vibrations sonores des gamelans. Ce sont des orchestres de xylophones en bambou, de métallophones, de gongs et autres tambours et percussions, agrémentés souvent d’une flûte et parfois de sortes de vièle (rebab) ou de cithare (kacapi). Sans oublier les voix au féminin et au masculin. Il y a trois grandes écoles de gamelans, ceux du pays Sunda (la partie occidentale de l’île de Java), le pays javanais lui-même (le centre et l’est) et, bien entendu, l’île de Bali. Claude Debussy avait écrit s’en être inspiré pour ses propres compositions. Francis Poulenc (Concerto pour deux pianos) a utilisé le gamelan. Steve Reich et Philip Glass ont été influencés par cette musique hypnotique, proche de la transe.

Pour découvrir le cœur de Bali, et comprendre l’âme de ses habitants, il suffit de suivre l’itinéraire musical qui mène d’un ensemble de gamelan à un autre, et d’avoir l’oreille disponible à être charmé sinon ensorcelé. La musique est à Bali ce que la méditation est à la religion. Elle participe à chaque événement social (naissance, limage des dents des jeunes gens, mariage, crémation-enterrement, etc.) ou religieux ou théâtral. Le tout se fondant en une même magie quotidienne. Chacune des communautés d’un village (les bandjars) possède son ensemble orchestral. L’aura des vibrations et les énergies se dégagent en musique de toutes les occasions rituelles pour fêter l’irrationnel. Les meilleurs musiciens et danseurs du village sont cooptés par leurs pairs et en faire partie est un honneur qui comporte beaucoup de devoirs. Le chef artistique (il y a aussi un chef administratif élu) est à la fois le compositeur des musiques et le professeur de musique et de danse pour l’ensemble des membres du «gong». En compensation du temps passé en répétitions, réunions officielles, déplacements et leçons particulières aux artistes les plus jeunes, le village lui prête gratuitement des rizières. Tous les membres de l’orchestre sont des amateurs, pour la plupart cultivateurs. Ils forment, eux-mêmes, leurs enfants à divers arts, en dehors de la musique, comme la peinture, la sculpture sur bois (à Mas) et sur pierre, l’argenterie (à Celuk) ou les arts textiles (à Ubud, technique javanaise). L’ensemble instrumental traditionnel, le fameux gamelan - qu’on appelle en fait gong besar, c’est-à-dire le grand orchestre - comprend 29 instruments, chacun utilisé par un musicien, à l’exception du barangan qui est joué par quatre musiciens. Il se compose ainsi :

- 1 ensemble de 4 gongs (considéré comme un seul instrument) : de tailles et de sonorités différentes, frappés selon un rythme lent par un seul musicien entouré de ses percussions.

- 18 gangce : métallophones dont les lames de bronze sont suspendues au-dessus de tubes en bambou servant de résonateurs. Il y a sept types de gangce ayant six, sept ou dix lames accordées selon la gamme pentatonique balinaise. Les cinq notes, ding, dong, deng, dung, dang, correspondent à nos mi, fa dièse, sol dièse, si et do dièse. Le musicien frappe avec rapidité les lames au moyen d’un marteau en bois tenu de la main droite, tandis qu’il amortit les lames de la main gauche.

- 1 gecek : instrument à percussion constitué de quatre petites cymbales fixées sur un petit banc et frappées par deux autres cymbales identiques dans les mains du musicien.

- 2 kendang : tambours tenus horizontalement et frappés, sur les deux faces, avec la main ou un petit maillet. Le plus gros des tambours, qui est considéré comme le mâle, est aux mains du chef d’orchestre. Lorsqu’un gamelan accompagne une danse, un dialogue s’installe entre le joueur de tambour et les danseurs qui mènent le rythme de leur chorégraphie. - 4 suling : flûtes en bambou, deux sopranes et deux ténors apportant six notes chacune.

- 2 bancs à cloches : le barangan (4 musiciens) et le trompong qui est joué en solo dans certains morceaux. Chacun de ces bancs portent 12 cloches (le trompong peut en avoir 13) dites reon.

- 1 petuk : cloche de bronze semblable au reon, mais fixée seule sur un petit banc et frappée de façon régulière pour donner le tempo.

Autre formation possible, l’angklung bambu : formé d’un cadre de bambou dans lequel deux tubes de bambous encochés peuvent se balancer et heurter la base du cadre pour produire leurs notes. On peut rencontrer des ensembles de 12 instruments angklung bambu jouant chacun simultanément deux notes à l’octave.

Durée du CD : 65’12

A. Le Ramayana

Le Ramayana qui conte les aventures d’un prince exilé, errant, a souvent été comparé à l’Odyssée d’Homère qui s’en est forcément inspiré. La plus vieille version connue du Ramayana est attribuée au sage Valmiki qui l’aurait écrite au Xe siècle avant notre ère. La version actuelle se compose de 2 400 vers répartis en 500 chants. Bible des Hindous, cette épopée mystique et morale est plus qu’une légende. Rama symbolise l’idéal des vertus masculines : force, endurance et honneur. Sita, son épouse, est l’idéal de la beauté, de la fidélité et de l’amour marital. Lakshmana, le frère de Rama, personnifie le courage et la loyauté. Quant à Ravana, le roi-démon et son armée de géants, ils représentent la cruauté, la luxure, la haine et la trahison. L’opposition entre les héros et leurs ennemis ne saurait être plus évidente. Bali, l’île où chaque rite a pour sujet la lutte immortelle entre les forces du bien et les forces du mal, est la terre promise d’un Ramayana quotidien. Rama, Sita et les autres, sans oublier Hanuman, le fidèle et malin général de l’armée des singes, sont présents à chaque détour de rizières et de temples : sculptures, peintures, danses, tragi-comédies, marionnettes du théâtre d’ombres Wayang Kulit, etc. Cet enregistrement de l’ensemble orchestral Semara Budava a eu lieu, en octobre 1974, à Kuta, au bord de la mer, devant un petit temple éclairé par un faible spot. Les visages mobiles des comédiens expriment, tour à tour, le dédain, l’orgueil ou la pitié. Les coups d’œil sont magnétiques. L’improvisation est totale dans la troupe des animaux : ainsi le brave oiseau Jatayu bat des ailes selon ses désirs, et l’armée des singes offre une touche de comique avec leurs galipettes désordonnées. La chorégraphie est à la mesure des sentiments des personnages. Le monstre Ravana et ses aides avancent à grandes enjambées arrogantes et prétentieuses, alors que les danseuses qui tiennent les nobles rôles masculins de Rama et Lakshmana et féminin de Sita, évoluent à petits pas distingués, en dodelinant de la coiffe. Les coudes, les poignets et les doigts des danseuses se plient avec une beauté fascinante. Comme pour retenir, dans l’humidité de l’air chaud, les notes obsédantes des métallophones.

1 – Enlèvement de Sita. 5’18

La princesse Sita, seule dans la forêt de l’exil, est enlevée par Ravana, roi des monstres à plusieurs têtes, qui s’était camouflé en ermite pour lui mendier un bol d’eau.

2 – Duel entre Ravana et Jatayu. 9’56

Kidnappée, emmenée de force dans les airs vers Lanka, la princesse Sita hurle et pleure. Le grand oiseau Jatayu tente d’attaquer Ravana mais, battu et grièvement blessé, il vient s’écraser par terre.

3 – Préparation aux batailles. 16’38

Rama était parti naïvement, à la demande de Sita, à la poursuite d’un daim en or. En fait, c’était la sorcière Maricha, sœur de Ravana, qui s’était transformée ainsi pour l’éloigner et tenter de le séduire. Il fut rejoint par Lakshmana accouru à son secours, et qui avait laissé Sita seule, croyant que Rama était en danger. Les deux frères reviennent à temps pour recueillir les dernières paroles de Jatayu qui leur raconte la mauvaise fortune de Sita. Rama demande alors à Hanuman, le général des singes, de partir à la recherche de Sita et de la retrouver. Il lui confie sa bague pour qu’il la montre et la laisse à sa bien-aimée. Ainsi, elle sera prévenue qu’ils sont tous sur le pied de guerre pour aller la reconquérir.

B. Le spectacle du Legong

Ce spectacle de la danse du Legong, ici enregistré le 21 octobre 1974 après 20 heures, sur la scène de l’Indraprastra Satge à Kuta, était destiné à renflouer la caisse de l’école primaire. L’entrée coûtait alors 600 roupies. A l’origine, le Legong était la danse mythique des nymphes divines, aux mouvements gracieux d’une quintessence de féminité. Cette chorégraphie, toute en symboles, pure de tout sujet depuis le XIIIe siècle, suit les rebondissements nombreux d’une histoire d’amour indonésienne très romanesque. Elle s’en échappe, parfois, pour devenir une danse abstraite, bien que toujours empreinte de séduction.

4 – Tabuh. 6’15

Instrumental d’ouverture.

5 – Baris. 3’42

Baris signifie “rangée”. Car, à l’origine, c’était une danse de guerriers, en ligne, se préparant moralement et physiquement au combat. Le Baris glorifie le courage et le triomphe. La relation intime qui existe entre le danseur et l’orchestre des gongs du gamelan, est si puissante qu’on ne distingue plus lequel accompagne ou dirige l’autre. Les gestes, tout d’abord lents et étudiés du danseur, muent en un tourbillon de mouvements saccadés, d’une précision parfaite, dans un déchaînement de fortes passions. Cette émotion spectaculaire est apte à faire fuir l’ennemi.

6 – Oleg Tambulilingan. 4’06

Cette chorégraphie est incluse dans le spectacle du Legong depuis le début des années 1950. “Tambulilingan” signifie “abeille”. La jeune fille entre sur scène la première, les doigts frémissants à l’image des ailes d’une abeille virevoltant d’un côté de la scène à l’autre, d’une fleur à l’autre, au rythme du gamelan. Arrive le bourdon dont les mouvements avivent les sentiments contradictoires de la femme. S’enchaînent sur son visage, à la cadence de ses petits pas, la séduction coquine comme la retenue de la pure innocence. Le couple se cherche, s’unit, se sépare et se retrouve, dans un assaut d’œillades et de coquetteries, de frôlements érotiques.

7 – Raja Pala. 2’05

Cette danse raconte l’histoire du chasseur Raja Pala qui découvrit le lieu secret Dedari où se baignaient nues les 7 vierges célestes ailées. Il subtilisa la blouse magique (une de ses ailes) de l’une d’elle, Sulasih, qui ne put retourner au ciel. Il l’a supplia de lui faire un enfant. Ce sera Durma, un fils, qu’ils élèveront durant 7 années. Puis, elle récupéra son aile manquante et retourna au ciel, alors que Raja Pala devint un saint homme.

8 – Tari Tenun. 1’53

On perçoit distinctement, en arrière plan, la son aigu des chauves-souris qui se regroupent par milliers dans les arbres, au-dessus des artistes et des spectateurs.

9 – Panji Semirang. 4’58

C’est la danse du grand conquérant, du super héros, toute en force et en grâce. La relation entre le danseur et le gamelan est intense. Celle aussi entre les mouvements agiles ondulés des bras d’une part, et l’irréalité du roulement des yeux dans leurs orbites d’autre part, le tout donnant un pouvoir magnétique aux expressions du visage du guerrier se préparant à la bataille.

10 – Tabuh – Tari Nelayan – Mergapati – Joged. 9’45

Ces titres s’enchaînent : l’ouverture (Tabuh), la danse du pêcheur (Tari Nelayan), la danse du lion (Mergapati) et la danse folklorique (Joged). Pour ce dernier morceau, on entend le grantang bumbung, un ensemble de quatre xylophones à lames de bambou utilisé surtout lors du Joged, danse au cours de laquelle une danseuse, après une introduction en soliste, pleine de séduction, vient chercher un homme dans le public pour l’inviter à se joindre à elle sur scène. Cette distraction est très populaire dans les fêtes balinaises du nord de l’île. Parfois, l’invité met l’assistance en joie par son inexpérience alors que sa partenaire est la meilleure danseuse du village. Lorsqu’elle juge que la mascarade a assez duré, elle le renvoie à sa place et en choisit un autre d’un coup d’éventail, volontaire, directif mais charmeur.

Production-réalisation : François JOUFFA (1974 et 2010).

Enregistrements à Bali en octobre 1974, au Nagra III mono sur bandes magnétiques Agfa-Gevaert offertes par la radio Europe n°1.

Textes : François JOUFFA (1975 et 2010) d’après des notes sur le terrain de Sylvie MEYER (1974).

Photos : François JOUFFA (1974), Sylvie JOUFFA (1977), Susie JOUFFA (2005). Photo de couverture : Didier Duval (1975).

Montage et premastering : Alexis FRENKEL, Studio Art & Son, Paris (2010).

Directeurs artistiques : Benjamin GOLDENSTEIN et Alexis JOUFFA (2010).

english notes

“The sighs of a wind instrument prolong the vibrations of vocal cords with such a sense of identity that one cannot tell if it is the voice itself that persists or its meaning that has, since the origins, absorbed the voice”.

Antonin Artaud, Le Théâtre balinais, 1931

“The gamelan was being played; a soft and uncertain melody was alternating with sharp, powerful and warlike notes that accelerated the beatings of the drum. He used to appreciate the expectancy of the dance that had him shiver with excitement.”

Vicki Baum, Liebe und Tod auf Bali, 1937

“The orchestra called ‘gamelang’ comprised about forty performers squatting in front of the instruments […], vibrating steel bars, gongs of all sizes lined up side by side, each echoing its single note, a whole set very complex and rich according to the musicologists, a knowledge discovered prior to the boldest and daring inventions in contemporary European music”.

Roger Vaillant, Boroboudour, Voyage à Bali, Java et autres îles, 1951

“The Balinese gamelan strikes with all its xylophones on every fibre of our sensibility. It is a ‘music-experience’ that involves the whole body: no feelings but instead a contact, a sensual symphony that has several cascades converge towards the same point”.

Mary Ottin and Alban Bensa, Le sacré à Java et à Bali, 1969

“Under the sky that has become clear inked-coloured, one can no longer distinguish the faces of the Balinese, emaciated, blending into the night. There remains only the white of the eyes. Waiting. Sitting in circle. Short stylized music of the gamelan, discrete coppered wriggles barely louder than the wind in the palms”.

Muriel Cerf, Le diable vert, 1975

Devils and wonders in Bali

Bali belongs to the Lesser Sunda Islands. Its surface covers an area of 5.635 km2. Its population rose from 2 to 3 million inhabitants in 40 years. Bali, the capital of which is Denpasar, is one of the provinces of the Republic of Indonesia. The word Indonesia comes from the Latin Indus, India, and from the Greek nesos, island: 17.500 islands, of which 3.000 are inhabited (the world’s biggest archipelago) with 240 million inhabitants (the fourth country in the world with the highest density). Indonesia is the country with the more important Muslim population while Bali is the only Hindu island of Indonesia with a majority of Hindu people and more than 20.000 Hindu temples. Cultural tourism and sport tourism (surfing) are among the more important economical activities of Indonesia due to Bali where it constitute the main resources. International tourism intensified greatly after the French Colonial Exhibition in Paris in 1931. Crafts, mainly influenced by the Islamic culture in Indonesia, are restrained due to the fact that human and animal representations are forbidden by the religion, except in Bali where arts have been greatly developed thanks to the heritage of both Buddhist and Hindu cultures, not to mention the animist influences. Touristic brochures present Bali as the last paradise on earth. One can easily agree with this view when beholding the sunset on the beach or when walking around on the slopes of the green hills tiered in rice paddies intertwined with palm groves and streams in which men and women bathe, sometimes naked. The wonders of nature are in harmony with the island’s gods and devils as Bali is both Paradise and Hell at the same time. The struggling between Good and Evil is constant. The favourable forces, the protective gods of the Hindu pantheon and of the animist traditions seat on the summit of sacred volcanoes. The evil forces, vampires, witches, have taken refuge in the depth of the seas. In order to reconcile the two extremes, the Balinese calendar is full of magical and religious ceremonies, and offerings are intended for the favourable divinities as well as for the bad spirits; the cosmic balance is thus respected for the sake of nature and individuals mind. In Bali, processions, prayers, folkloric and classical dances – always with a mythical dimension – cremations as well as exorcisms are backed by the sound vibrations of gamelans. These are orchestras of bamboo xylophones, metallophones, gongs and other drums and percussions, often embellished with a flute or, at times, of some sort of fiddle (rebab) or zither (kacapi). Not to mention the female and male voices.

There are three major styles of gamelan, one in the Sunda land (in the Western part of Java Island) another in the heart of the Javanese country (Central and Eastern Java) and, naturally, one in Bali. Claude Debussy wrote it had inspired him for his own compositions. Francis Poulenc (Concerto for Two Pianos) used the gamelan. Steve Reich and Philip Glass were influenced by this hypnotic music, near trance. To discover the heart of Bali, and understand the soul of its inhabitants, just follow the musical journey that leads to a set of gamelans to another and keep your ears wide opened to its charm if not its enchantment. Music is in Bali what meditation is to religion. It is part of all social events (birth, teeth grinding, wedding, cremation-burial, etc.) as well as of religious and theatrical ones, the whole participating to the same everyday magic. Each community of a village (bandjars) has its own orchestra. The aura of the vibrations and the energies free up the music in all the ritual occasions that celebrate the irrational. The best musicians and dancers from the village are co-opted by their peers, and being part of it is an honour that entails numerous duties. The artistic leader (there is also an elected administrative chief) is both the music composer and music and dance teacher of all the members of the “gong”. As a compensation for the time spent in rehearsals, official meetings, journeys and in private lessons given to younger artists, the village put at his disposal some portions of paddy field for free. All the members of the orchestra are amateurs, most of them being farmers the rest of the time. Besides music, they personally train their children in various arts like painting, wood (in Mas) and stone carving, silver work (in Celuk) or textile arts (in Ubud, Javanese technique). The famous traditional instrumental band, the famous gamelan – actually called “gong besar”, that is to say the full orchestra – is comprised of 29 instruments, each used by a single musician, except the barangan that requires four musicians.

It is composed thus:

- A set of 4 gongs (considered as one instrument): of different sizes and tones struck at a slow pace by a single musician surrounded by his percussion instruments.

- 18 gangsa gantung: metallophones with bronze bars suspended over bamboo tubes used as resonators. There are seven types of gangsa gantung, with six, seven or ten bars, tuned according the Balinese pentatonic scale. The five notes, ding, dong, deng, dung, dang correspond to our E, F#, G#, B and C#. The musician strikes the bars quickly using a wooden hammer held in his right hand while damping the bars with the left hand.

- 1 ceng-ceng: percussion instrument made of four small cymbals mounted on a wooden frame and struck by two small identical cymbals held by the fingers of the musician.

- 2 kendang: drums held horizontally and struck on both sides with the hand or a small mallet. Considered as the male instrument, the biggest drum is held by the conductor. When a gamelan accompanies a dance, a dialogue is established between the drummer and the dancers that lead the pace of their choreography.

- 4 suling: bamboo flutes, two sopranos and two tenors bringing six notes each.

- 2 gongs in a row: the barangan (4 musicians) and the trompong which is played in solo in some songs. Each of the rows comprises 12 bells (the trompong can have 13) called reyong.

- 1 petuk: bronze bell similar to the reyong but merely fixed on a small frame and struck on a regular basis to set the tempo. The angklung bamboo is another possible ensemble: it is made of a bamboo frame in which two bamboo slotted tubes can swing and strike the base of the frame to produce musical notes. One can find sets of 12 angklung bamboo instruments each playing simultaneously two notes an octave.

Total playing time: 65’12

A- The Ramayana

The Ramayana, which recounts the adventures of a prince in exile, wandering, has often been compared to Homer’s Odyssey that probably drew its inspiration from it. The oldest known version of the Ramaya is attributed to the sage Valmiki who is said to have written it in the tenth century B.C.E. The current version consists of 2400 verses distributed into 500 songs. Considered as the Bible of the Hindu this mystic and moral epic is more than a legend. Rama symbolizes the ideals of masculine virtues: strength, endurance and honour. His wife Sita is the ideal of beauty, fidelity and marital love. Lakshmana, Rama’s brother, is the personification of courage and loyalty. As to the demon king Ravana and his army of giants, they represent cruelty, lust, hatred and betrayal. The contrast between the heroes and their enemies could not be made more evident. Bali, the island where every ritual is about the eternal struggle between good and evil forces, is the promised land of a daily Ramayana. Rama, Sita and the others, including Hanuman the faithful and clever general of the monkey army, are present at every turn of rice paddies and temples: in sculptures, paintings, dances, tragic-comedies, in the puppets of the Wayang Kulit shadow theatre, etc. This recording of the orchestral ensemble Semara Budava took place in October 1974, nearby the sea in Kuta, in front of a small temple illuminated by a weak spot. The actors’ mobile faces were expressing successively disdain, pride and pity. The glances were magnetic. Improvisation was the rule among the animals’ characters: while the brave Jatayu was flapping his wings in his own way (ad-lib), the army of monkeys was providing a comic touch with its tricks and disorganized somersaults. The choreography accompanied the characters’ feelings. Whereas the monster Ravana and his attendants were striding forward in an arrogant and pretentious way, the female dancers who assumed the leading roles of Rama, Sita and Lakshmana, were taking small and elegant steps while nodding their heads.

1- The abduction of Sita. 5’18

Princess Sita, alone in the forest of exile, is kidnapped by Ravana, the multi-headed lord of the demons, who had disguised himself as a hermit begging for a bowl of water.

2 – The battle between Ravana and Jatayu. 9’56

Kidnapped against her will into the air towards Lanka, princess Sita is screaming and shedding tears. The great bird Jatatyu attacks Ravana but he gets seriously injured and crashes on the ground.

3- Preparing for battles. 16’38

Rama who had gone credulously in pursuit of a golden deer -in fact the witch Maricha, the sister of Ravana, who had changed her appearance- and Lakshmana who had left the princess alone as he thought his brother was in danger, are back and collect the last words of Jatayu who tells them about Sita’s misfortune. Rama then asks Hanuman, the general of the monkey army, to go in search of Sita. He entrusted his ring to Hanuman to let his beloved know they are all on the warpath to rescue her.

B. The Legong Dance

The Legong performance, here recorded in October 21, 1974, after 8pm on the Indraprastra Satge stage in Kuta was intended to raise funds for the treasury of the village primary school. The entry fare was of 600 rupees. Originally, the Legong was the mythical dance performed by celestial nymphs. The choreography, high in symbols, has been kept intact in its subject matter since the XIIIth century and follows the numerous twists and turns of a romantic Indonesian love story. But it sometimes strays from the subject and becomes an abstract dance, although still imbued with seduction.

4- Tabuh. 6’15

Instrumental opening.

5 – Baris. 3’42

Baris means “rows”. For, originally, it was the dance of warriors, aligned in rows and preparing morally and mentally for battle. The Baris glorifies courage and triumph. The intimate link between the dancer and the gamelan orchestra of gongs is so strong that one cannot distinguish which one accompanies or leads the other. The dancer’s gestures first slow and measured then turn into a whirlwind of jerky movements, perfectly accurate, in an outburst of vigorous passions. Such a dramatic emotion has the enemies run away.

6- Oleg Tambulilingan. 4’06

This choreography is included in the Legong show since the early 1950s. “Tambulilingan” means “bee”. The lady gets on the stage first, her fingers trembling just like the fluttering wings of a bee fliying from one side of the stage to another, from one flower to another, to the beat of the gamelan. Then comes the drone whose movements intensify the conflicting feelings of the lady. Her face shows successively, at the pace of her small steps, naughty seduction and the reserve of pure innocence. The couple is trying to find its way, unites, splits and gets back together, flirtatiously casting glances while their erotic bodies, in a light contact, are brushing against each other.

7- Raja Pala. 2’05

This dance tells the story of the hunter Raja Pala who discovered Dedari, the secret location where used to bathe the 7 naked and winged celestial virgins. He stole the celestial nymph Sulasih’s magical blouse (one of her wings) who therefore couldn’t return to heaven. He begged her to give him a child. It will be Durma, their son they bred together for 7 years. She then recovered her missing wing and returned to heaven while Raja Pala became a holy man.

8 – Tari Tenun. 1’53

One can distinguish clearly, in the background, the shrilling sounds of thousands of bats gathering in the trees just above the artists and the audience.

9 – Panji Semirang. 4’58

It is the dance of the great conqueror, the super hero, all in strength and in grace. The relationship between the dancer and the gamelan is intense. Alike the one between the nimble movements of the waving arms and the unreality of the rolling of the eyes in their sockets, the whole giving a magnetic power to the facial expressions of the warrior preparing for battle.

10 – Tabuh – Tari Nelayan – Mergapati – Joged. 9’45

The following pieces are consecutive: the opening (Tabuh), the fisherman’s dance (Tari Nelayan), the lion’s dance (Mergapati) and the folk dance (Joged). In this last piece, one can hear the grantang bumbung, a set of four xylophones with bamboo bars used essentially during the Joged, dance in which a female dancer, highly seductive, after an opening in solo, picks up a man at random in the audience and invites him to join her on stage. This distraction is very popular during the Balinese celebrations of the Northern part of the island. Sometimes, the guest delights and amuses the audience because of his inexperience in dancing while his partner is the best female dancer of the village. When she thinks the masquerade has lasted long enough, she sends him back to his chair and selects another one by pointing her hand-held fan in a determined, directive but charming way.

Production-direction: François JOUFFA (1974 and 2010). Recordings in Bali in October 1974 with a Nagra III mono on magnetic tapes Agfa-Gevaert offered by the French radio station Europe n°1. Texts: François JOUFFA (1975 and 2010) adapted from the notes taken in situ by Sylvie MEYER (1974). English translation: Susie Jouffa. Photographs: François JOUFFA (1974), Sylvie JOUFFA (1977), Susie JOUFFA (2005). Cover picture: Didier Duval (1975). Editing and premastering: Alexis Frenkel, Studio Art & Son, Paris (2010). Artistic and Technical advisors: Benjamin GOLDENSTEIN and Alexis JOUFFA.

CD Le RAMAYANA A BALI © Frémeaux & Associés (frémeaux, frémaux, frémau, frémaud, frémault, frémo, frémont, fermeaux, fremeaux, fremaux, fremau, fremaud, fremault, fremo, fremont, CD audio, 78 tours, disques anciens, CD à acheter, écouter des vieux enregistrements, albums, rééditions, anthologies ou intégrales sont disponibles sous forme de CD et par téléchargement.)