- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

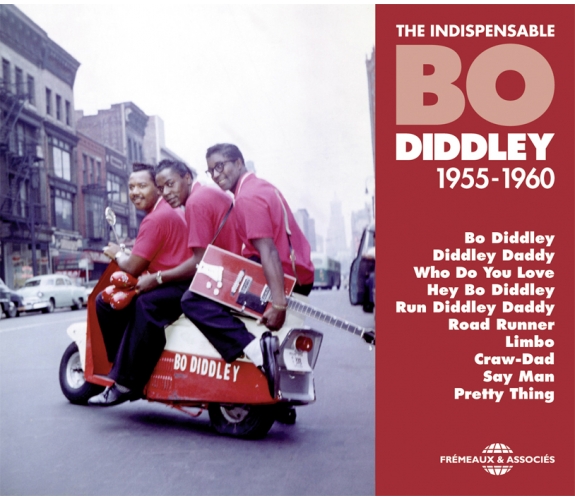

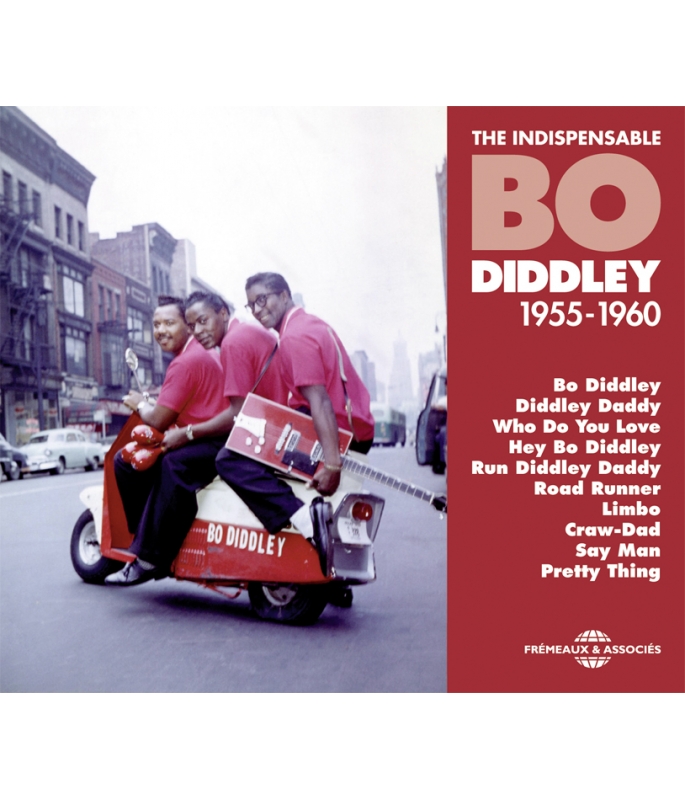

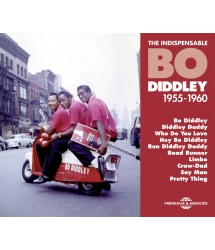

BO DIDDLEY

Ref.: FA5376

EAN : 3561302537627

Artistic Direction : BRUNO BLUM

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Total duration of the pack : 2 hours 49 minutes

Nbre. CD : 3

Bo Diddley was probably the most original rhythm & blues musician of the Fifties and Sixties. He was a remarkable singer, a prolific composer who left his mark in everyone’s songbook, an (often very funny) stage-personality... not to mention a revolutionary rhythm-guitarist whose innovations were both stylistic and technical. A visionary who defied all attempts to classify him, he became a spiritual father to many artists, from soul-singers to rappers, blues, rock and roll and even punk-rock figures, who all seemed to recognise themselves in Bo’s unbridled genius. This selection of his recordings compiled by Bruno Blum proves his status as a genuine monument in 20th century popular music. Patrick FRÉMEAUX

ELVIS PRESLEY & THE AMERICAN MUSIC HERITAGE...

THE INDISPENSABLE 1959-1962 VOL. 2

YOUNG AND WILD 1948-1949 & 1969 NOUVELLE...

I PUT A SPELL ON YOU - LIVE 1988

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1I'm a ManBo Diddley00:02:481955

-

2Little GirlBo Diddley00:02:361955

-

3Bo DiddleyBo Diddley00:02:311955

-

4You Don't Love MeBo Diddley00:02:491955

-

5Diddley DaddyBo Diddley00:02:281955

-

6She's Fine, She's MineBo Diddley00:02:441955

-

7Pretty ThingBo Diddley00:02:541955

-

8Heart-O-Matic LoveBo Diddley00:02:481955

-

9Bring It to JeromeBo Diddley00:02:321955

-

10Spanish GuitarBo Diddley00:04:081955

-

11Dancing GirlBo Diddley00:02:251955

-

12Diddy Wah DiddyBo Diddley00:02:331955

-

13I'm Looking For A WomanBo Diddley00:02:341955

-

14I'm BadBo Diddley00:03:171956

-

15Who Do You LoveBo Diddley00:02:321956

-

16Cops And RobbersBo Diddley00:03:281956

-

17Downhome SpecialBo Diddley00:03:151956

-

18Hey Bo BiddleyBo Diddley00:02:131956

-

19I Need You BabyBo Diddley00:02:231957

-

20Ed Sullivan, Dr Jive IntroductionEd SullivanEd Sullivan00:00:561957

-

21Bo Diddley 2Bo Diddley00:01:551956

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Say Boss ManBo Diddley00:02:341957

-

2Before You Accuse MeBo Diddley00:03:071957

-

3Say ManBo Diddley00:03:131957

-

4Hush Your MouthBo Diddley00:02:521957

-

5Bo's GuitarBo Diddley00:02:351957

-

6Dearest DarlingBo Diddley00:02:541957

-

7Willie And LillieBo Diddley00:02:191958

-

8Bo Meets The MonsterBo Diddley00:03:071958

-

9Crackin' UpBo Diddley00:02:061958

-

10Dont Let It GoBo Diddley00:02:451958

-

11I'm SorryBo Diddley00:02:271958

-

12Oh YeaBo Diddley00:03:091958

-

13Blues BluesBo Diddley00:02:571958

-

14The Great GrandfatherBo Diddley00:02:291958

-

15Mama MiaBo Diddley00:02:581959

-

16BucketBo Diddley00:02:331959

-

17Lazy WomanBo Diddley00:02:331959

-

18Come On BabyBo Diddley00:01:591959

-

19Nursery RhymeBo Diddley00:02:501959

-

20Mumblin GuitarBo Diddley00:02:511959

-

21I Love You SoBo Diddley00:02:241959

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Story Of Bo DiddleyBo Diddley00:02:501959

-

2She's AlrightBo Diddley00:04:051959

-

3Live My LifeBo Diddley00:02:291960

-

4LimberBo Diddley00:03:011959

-

5Say Man Back AgainBo Diddley00:02:431959

-

6Run Diddley DaddyBo Diddley00:02:471959

-

7Road RunnerBo Diddley00:02:381959

-

8Spend My Life With YouBo Diddley00:02:251959

-

9Love You BabyBo Diddley00:02:151959

-

10DiddlingBo Diddley00:02:461959

-

11CadillacBo Diddley00:02:391959

-

12LimboBo Diddley00:02:311959

-

13Look at Me BabyBo Diddley00:02:561960

-

14You Know I Love YouBobby Baskerville00:01:561960

-

15Let Me InBo Diddley00:02:371960

-

16Signifying BluesBo Diddley00:02:391960

-

17Scuttle BugBobby Baskerville00:02:251960

-

18Love MeBo Diddley00:02:241960

-

19Deed And Deed I DoBo Diddley00:02:201960

-

20Walkin' And TalkingBo Diddley00:02:431960

-

21Travelin WestBo Diddley00:01:481960

-

22Craw-DadBo Diddley00:02:291960

CLICK TO DOWNLOAD THE BOOKLET

Diddley FA5376

THE INDISPENSABLE

BO DIDDLEY 1955-1960

Bo Diddley

Diddley Daddy

Who Do You Love

Hey Bo Diddley

Run Diddley Daddy

Road Runner

Limbo

Craw-Dad

Say Man

Pretty Thing

1964 Le débarquement triomphal des Beatles pour la première fois en Amérique donna lieu à une conférence de presse :

Quelle est la première chose

que vous aimeriez voir aux États-Unis, John ?

John Lennon : Bo Diddley !

Descendant d’une famille d’esclaves de la «?ceinture de coton?» dans le delta du Mississippi, Bo Diddley est comme Fats Domino un pur produit de la créolité, sang-mêlé français, africain et indien Blackfoot. Sa mère Ethel Wilson vivait dans une ferme du sud profond des États-Unis et rencontra Eugene Bates, le père qu’Ellas Bates (né le 30 décembre 1928 à McComb, Mississippi, décédé le 2 juin 2008 à Archer, Floride) n’a jamais connu. Ethel avait à peine seize ans à la naissance d’Ellas. Trop jeune pour subvenir à ses besoins, elle confia son bébé à sa cousine germaine, Gussie McDaniel. En 1934, le décès du mari de la jeune Gussie et la Grande Dépression économique n’ont guère laissé le choix à sa famille qui, comme beaucoup d’Afro-américains pendant cette période, migra dans un ghetto surpeuplé de Chicago, glaciale ville du nord. Déjà initié au son du blues du Mississippi, Ellas se retrouva ainsi en compagnie de son oncle Herbert Wilson, sa tante Janie et leurs quatre enfants. Pour obtenir l’inscription d’Ellas à l’école, Gussie dût adopter l’enfant et lui donner le nom qui figure depuis sur tant de disques : Ellas McDaniel, l’un des compositeurs les plus repris de l’histoire du rock.

À eux seuls, les Rolling Stones ont enregistré six titres de lui dont les «?Diddley Daddy?», «?Craw-Dad, Crackin’ Up?» et «?I Need You Baby?» (dit «?Mona?») inclus ici sans oublier le «?Not Fade Away?» de Buddy Holly, dérivé de son fameux «?Mona?». Mick Jagger collectionnait ses disques et l’a rencontré en 1962, au tout début de sa carrière, quand il faisait ses premiers pas au Marquee Club.

Bo Diddley se souvient :

«?J’ai joué avec les Stones avant qu’ils ne soient connus et deux fois ensuite. J’ai adoré. Ils sont un de mes groupes préférés. Ils l’étaient à cette époque et le seront toujours. La seule chose que je n’ai pas comprise, mais je suppose que chaque génération à son propre sac à malices, c’est qu’à un moment j’ai trouvé que le public avait poussé Mick à devenir vulgaire sur scène. C’est peut-être ce qu’il a fallu qu’il fasse pour en arriver où il en est et je suis ravi qu’il ait réussi, tu sais mais… je pense que c’est sa génération qui réclamait ça. Je dirais ça comme ça. Je ne suis pas contre lui parce qu’il a remué son derrière devant les gens, avec les mômes et tout ça, parce qu’on m’a dit que je faisais la même chose alors j’ai essayé de nettoyer mon jeu de scène car je ne voulais pas faire ça, mais c’est cool, ce métier c’est le spectacle et pour ce qui est du spectacle ils ont fait un sacré boulot.?»

Entretien avec l’auteur à Paris en 1984.

La famille Wilson/McDaniel s’installe au 4746 Lan-gley Avenue dans le quartier insalubre, pauvre et violent du South Side «?où l’on grandit en prenant soin de soi-même. Car si tu ne le fais pas, quel-qu’un d’autre va s’occuper de toi. À Chicago il fallait prendre soin de soi sinon les mômes te cassaient la tête. Je ne sais pas pourquoi, mais c’était comme ça1.?»

Sa mère Gussie, sévère et très pieuse, l’emmène à l’église tous les jours sans exception. C’est à l’église baptiste missionnaire Ebenezer qu’il apprend à jouer du violon et à chanter. Il y découvre qu’il a une voix très puissante. Il a douze ans quand sa sœur Lucille lui offre une guitare à noël. Mais quand il essaye de jouer du blues au violon et veut adapter «?The Honeydripper?» de Joe Liggins, le professeur de musique lui donne une raclée et lui casse l’archet sur le dos. À quinze ans, il passe au trombone et joue dans l’orchestre de l’église pendant deux ans. Puis il se met à la guitare en utilisant la technique du violon qui permet de remuer son poignet droit avec rapidité. Ses mains sont énormes, et il ne peut pas jouer de subtilités sur le manche. Il développe ainsi une technique très personnelle, axée sur une rythmique jouée frénétiquement sur un accord en mi «?open?» qui lui permet de former un accord en barrant le manche avec un seul doigt. Son style est aussitôt unique. À l’école il apprend à fabriquer un violon, une contrebasse, puis crée une guitare et monte un groupe, les Hipsters, avec un cousin de Nat «?King?» Cole qui joue de la basse «?washtub2?». Décidé, il abandonne les classes à seize ans et devient le bricoleur à tout faire du quartier. Débrouillard, il répare tout ce qu’il trouve pour gagner quelques pièces tandis que les autres ados jouent au basket. Il vend du bois, porte les courses, répare les toits, les radios, les voitures… Son camarade de classe, le guitariste Earl Hooker, gagne des pièces en jouant au coin des rues, et les Hipsters l’imitent bientôt. Un copain, «?Sandman?», utilise un plateau couvert de sable, qu’il fait bouger en rythme. Sa famille n’accepte pas qu’il joue de la guitare ni qu’il écoute du blues, considéré diabolique par les Baptistes, et il cesse d’aller à l’église. Ellas adore Louis Jordan, Nat «?King?» Cole et la simplicité du jeu de John Lee Hooker l’inspire. Muddy Waters joue dans plusieurs cabarets de Chicago avec Little Walter et bien qu’il n’ait pas l’âge requis pour entrer il va les voir régulièrement. Muddy a douze ans de plus que lui et il lui voue une grande admiration.

Les Hipsters doivent jouer dans les rues sans que la famille d’Ellas le sache. Ils gagnent des sommes de plus en plus importantes et sont poursuivis par les adolescents du quartier. Ils doivent se défendre au couteau, et se font arrêter pour port d’arme. Bien qu’ils n’aient pas de permis de conduire ils finissent par acheter une Buick 1937 pour pouvoir fuir les gangs dès leur prestation terminée et leur succès grandit. Devenus les Langley Avenue Jive Cats, ils gagnent plusieurs concours amateur au point qu’on leur refuse l’inscription aux concours suivants. Costaud, adepte de l’autodéfense, Ellas devient boxeur amateur, puis se marie avec Louise, qui lui interdit la boxe. Il devient serveur dans une boutique de légumes, groom, employé en chambre froide d’un boucher grossiste, puis travaille dans une imprimerie. Remarié en 1949 avec Ethel «?Tootsie?» Smith, il bosse dans une usine de cadres pour tableaux et travaillera cinq ans à la construction de routes. Mal payé, il continue à jouer dans les rues pour compléter ses revenus. En 1950-52, l’harmoniciste virtuose Billy Boy Arnold rejoint son groupe, mais le quittera déplorant leur «?manque d’ambition?».

Bo Diddley beat

Ils jouent du Sonny Boy Williamson et le «?Rollin’ Stone?» de Muddy Waters en plus des compositions d’Ellas, qui a créé un amplificateur de fortune pour sa guitare en bricolant un lecteur de disques. Il s’offre ensuite un vrai ampli puissant, un Silvertone qu’il modifie pour obtenir un son original à la fois puissant et sans distorsion.

«?Je cherchais un plus gros son, et j’ai trouvé ce «?freight train drive?», c’est comme ça que je l’appelle. On n’était que trois mais j’avais développé un style qui donnait l’impression qu’on était au moins six. Voilà le monstre que j’avais construit [rires] ! Si tu écoutes ce que je joue, il n’y a pas de trous. Je joue la première et la deuxième guitare en même temps et dès que je commence à jouer tu es vite au courant ! C’est bourré de puissance sans interruption. De l’énergie pure1.?»

Il fabrique aussi un effet de son qui sera déterminant pour lui : il crée un effet trémolo pour guitare avant que Diamature n’en mette un sur le marché. Ce nouveau son original ajoute à sa forte personnalité et à son style à part.

«?C’était un délire que de jouer avec un son qui disparaît et qui revient - on perd le rythme - mais j’ai appris à jouer avec et après ça c’était le truc le plus fantastique au monde, j’ai pu l’utiliser à mes fins. […] J’étais le seul à faire ça dans le R&B, le rock ‘n’ roll, comme vous voudrez l’appeler. Personne ne faisait ça. Tu as pu en entendre sur quelques slows, mais c’est tout car le rythme se désynchronisait et on ne pouvait pas danser dessus1.?»

Jouant sans batterie, il engage son voisin d’en dessous Jerome Green aux maracas, empruntant ainsi à la tradition «?calypso?» en vogue à l’époque. Le son original entendu sur cet album prenait forme ; On lui demandait constamment quel genre de musique il jouait, ce à quoi il répondait «?je n’en sais rien, je la joue c’est tout1?».

Le célèbre rythme Bo Diddley beat fera sa gloire puis les beaux jours du rock anglais, de «?Not Fade Away?», premier numéro trois des Rolling Stones (février 1964) au «?Magic Bus?» des Who (1968) jusqu’au «?Faith?» de George Michael (1987). Il est en réalité basé sur un rythme «?répandu dans les zones côtières ouest-africaines3?» que l’on retrouve dans les percussions du mento jamaïcain, du calypso de Trinidad4, de la biguine martiniquaise et guadeloupéenne. Il est aussi parfois joué sur la clave dans le son, la rumba, la guaracha et le sucu sucu cubain. On peut par exemple l’entendre sur la version de «?Tin Tin Deo?» par l’orchestre afro-cubain de Dizzy Gillespie avec John Coltrane et Milt Jackson en 1951.

Pour Bo Diddley, son rythme particulier est un mélange de «?chant religieux, de blues/rhythm and blues et de spirituals5?» qu’il aurait spontanément créé, influencé par des rythmes entendus à l’Eglise, mais il n’était même pas sûr de cette influence.

«?Je dirais que c’est un mélange : rhythm and blues, Amérique latine, et du hillbilly, un peu de spirituals, un peu d’Afrique et de calypso des Caraïbes… et si je veux chanter un yodel dessus, je peux le faire aussi. J’aime le gumbo, tu comprends ? Et les sauces fortes. Ma musique vient de là : je mélange tout. Sur «?Bo Diddley?» j’ai mélangé ces rythmes au point qu’ils ne sont pas arrivés à les trier !1?»

Son fameux rythme joué ici à la guitare sur «?Bo Did-dley?», «?Pretty Thing?», «?Cadillac?», «?Bucket?», «?Limbo?», ou «?I Need You Baby?» est plus vraisemblablement issu du mento jamaïcain, dont les premiers disques commençaient à paraître aux États-Unis dans les années 19506. «?Limbo?» (1959), entendu sur cet album, emprunte d’ailleurs son refrain et une partie de ses paroles - et son rythme - à un mento du même nom7. Le limbo est le nom de la danse acrobatique consistant à passer sous une barre de plus en plus basse en se penchant en arrière. Elle faisait partie de la panoplie «?calypso?» en vogue sur les plages trinidadiennes et jamaïcaines dans les années 1950.

Très pauvre avec un loyer à payer, femme et bébé, il joint les deux bouts grâce aux concerts, mais en 1954 il n’envisage toujours pas de devenir professionnel en raison des réticences de sa femme. Prêt à tout pour survivre, il vend des boissons, conduit des camions d’éboueurs et le week-end joue au coin des rues et dans des bars. Inspiré par des musiciens utilisant leur sens de l’humour, il est très influencé par l’essentiel Louis Jordan, dont il reprend un temps le «?Caldonia?». Il joue aussi le «?Hey Ba Ba Rebop?» de Cab Calloway et l’instrumental «?Honeydripper?» de Joe Liggins. Il interprète aussi quelques blues, mais estimant que Muddy Waters ou John Lee Hooker font ça mieux que lui, il préfère développer tout ce qui peut être différent, personnel et cesse les reprises afin de ne rivaliser avec personne et de trouver des engagements.

«?Personne ne peut écrire de morceaux pour moi. Parce qu’ils ne comprennent pas. Il faut commencer par traîner avec moi pour voir comment je fais les choses. Un tas de gens a essayé de copier mes trucs et ils l’ont mal interprété. Ils s’en sont bien sortis. Mais disons que quand je joue avec un groupe et que le batteur commence à jouer le rythme Bo Diddley il faut que je lui dise «?non-non?» c’est pas ça. Il faut que je me mette à la batterie et que je lui montre comment ça a été fait. Le vrai rythme est sur l’original, sur «?Bo Diddley?». […] Le Bo Diddley beat peut être joué avec plein d’approches différentes [il joue le rythme sur le coin de la table, alternant deux schémas rythmiques différents]. Beaucoup le jouent comme ça [il joue cette fois le même schéma plusieurs fois de suite]. C’est pas bon.?»

Entretien avec l’auteur à Paris en 1990.

Ses musiciens changent fréquemment, mais fin 1954, il engage Clifton James à la batterie. Son épouse cède face à sa détermination de jouer, et sa formule originale plaît de plus en plus. Il travaille toujours dans le bâtiment l’été (il n’y a pas de chantiers en hiver à Chicago) quand Billy Boy Arnold revient dans le groupe et le convainc enfin, vers février 1955, d’enregistrer une maquette - refusée par United Records.

Chicago Blues

Ils sont alors reçus chez la marque indépendante Chess Records par les frères Leonard et Phil Chess, une petite entreprise familiale qui produit du jazz et du rock dans le style jump blues et distribue dans le nord du pays les disques Sun, qui l’été suivant allaient lancer le premier 45 tours d’Elvis Presley. Les frères Chess produisent aussi le roi du Chicago blues, leur vedette Muddy Waters, et son harmoniciste virtuose Little Walter. Un petit studio est installé dans le bureau des deux frères, qui possèdent le matériel nécessaire pour presser eux-mêmes les disques, jusqu’à imprimer les étiquettes. Chess fait répéter le groupe deux jours et ils enregistrent aussitôt «?I’m a Man?» et trois autres titres au studio Universal Recording. Selon Bo Diddley lui-même, «?I’m a Man?» est basé sur le «?She Moves Me?» (1951) de Muddy Waters. Muddy Waters apprécie «?I’m a Man?», qui lui inspirera bientôt sa propre composition «?Mannish Boy?» sur le même thème, mais sur une mélodie et un riff différents.

Leonard Chess a remplacé le bassiste «?washtub?» Roosevelt Jackson par un vétéran du rhythm and blues, Willie Dixon à la contrebasse (qu’on entend mal sur les quatre premiers morceaux). À peine sorti, «?I’m a Man?» fait instantanément de Bo Diddley un nouveau nom du très influent Chicago blues. Il sera repris et enregistré par Jimi Hendrix, The Who, The Yardbirds, Dr. Feelgood… et tant d’autres.

Parodie de «?I’m a Man?», «?I’m Bad?» enfonce le clou blues. La plupart des morceaux sont remarquablement bien chantés et ont à la fois le senti et le son du blues avec Billy Boy Arnold à l’harmonica, Otis Spann au piano et le célèbre auteur compositeur Willie Dixon à la contrebasse. On retrouve d’ailleurs ces deux derniers sur nombre de disques de Muddy Waters, Sonny Boy Williamson II, Howlin’ Wolf et Chuck Berry, qui rejoint également Chess en 1955 et démarre très fort avec son premier succès «?Maybellene?». Nourrie des spirituals et du gospel baptiste («?Don’t Let It Go?»), plongeant ses racines dans le delta du Mississippi où il est né, la musique de Bo Diddley s’impose aussitôt comme une référence du Chicago blues électrique et urbain du nord, à classer avec les autres géants du genre : Sonny Boy Williamson II, Little Walter, Muddy Waters, Elmore James, Buddy Guy, J.B. Lenoir, Big Walter Horton, Robert Lockwood Jr. et nombre d’autres de ses contemporains. D’autres compositions de ses débuts en studio resteront des classiques du blues, notamment «?You Don’t Love Me (You Don’t Care)?», «?Bring It to Jerome?», «?Lit-tle Girl?», «?Roadrunner?» ou «?Blues, Blues?». Son splendide «?She’s Fine (She’s Mine)?» sera enregistré à Memphis en 1960 par Willie Cobbs, qui en changera le titre et en tirera son succès «?You Don’t Love Me?». Il sera repris par nombre d’artistes, dont The Allman Brothers qui le graveront sur leur célèbre album de 1971 At Fillmore East et la chanteuse Dawn Penn qui en publiera une version rocksteady en 1967 chez Studio One (réenregistré en 1994, ce morceau deviendra un succès international du reggae sous le nom de «?(No No No) You Don’t Love Me?»). Certains de ces blues seront repris par des groupes de rock, comme «?Before You Accuse Me?» (qui deviendra un classique de Creedence Clearwater Revival) ou «?Cops and Robbers?» de Boogaloo and his Gallant Crew, gravé par les Rolling Stones, qui ne connaissaient que la reprise de Bo Diddley (ils ne sortiront pas leur enregistrement, qui circulera largement sous forme de pirate). Bien rares sont d’ailleurs les morceaux enregistrés par Bo Diddley qui n’ont pas été écrits par lui-même. Car plus que tout, il tient à son originalité, qui fait sa force. Il refusera toujours d’être catalogué «?blues?» - autant que rock and roll : il est Bo Diddley. Sa créativité n’aura pas de barrières, et le rendra vite impossible à classer entre blues, soul8, funk, rock, punk rock, rap, rhythm and blues - et chanson comique.

Funk

Pour leur premier 45 tours, le bassiste Roosevelt Jackson, hilare, suggère de changer le nom d’Ellas McDaniel en Bo Diddley, un surnom marrant qui évoque un type de petite taille aux jambes arquées (bow leg), une expression qu’ils trouvent comique et qui figure dans une de leurs chansons, «?Uncle John?». Le diddley bow est aussi un rudimentaire instrument de musique à une corde montée sur un arc, bien connu aux États-Unis. Il est sans doute hérité des cithares à une corde ou ideochords répandues dans la région du Gabon-Cameroun. Une fois rassuré sur le sens non raciste du terme («?diddley?» signifie en anglais «?rien du tout?»), Leonard Chess adopte le nom d’artiste Bo Diddley.

«?On m’a surnommé comme ça dès l’école. Je me suis toujours demandé pourquoi on m’appelait comme ça. Je ne sais pas ce que ça veut dire exactement, en gros ça veut juste dire «?mauvais garçon?», «?malicieux?». J’ai commencé à utiliser ce nom au gymnase d’Eddie Nicholson, mais je ne l’utilisais que pour la boxe?; Tous mes amis m’appelaient «?Mac1?».?»

Bo Diddley devient aussi le nom d’un morceau enregistré lors de la toute première séance et appelé jusque-là «?Uncle John?» (le prénom «?John?» signifie aussi «?sexe masculin?» en argot), aux paroles un peu risquées, et modifiées à la dernière minute. À l’origine, il chantait :

Uncle John got corn ain’t never been shucked

Uncle John got daughters ain’t never been… to school

The bow-legged rooster told the cock-legged duck

You ain’t good lookin’ but you sure can crow!

Censuré par Leonard Chess, Bo Diddley emprunte la mélodie et le premier couplet du «?Hambone?» de Red Saunders (1952) dérivé d’une chansonnette pour enfants qu’il plaque sur son rythme et crée ainsi le morceau «?Bo Diddley?». Il y raconte ensuite comment sa femme le trompe avec un doodle (sexe en argot, également appelé boodle) qui utilise un mojo, c’est-à-dire une amulette hoodoo (vaudou), un os de chat noir9.

Mojo come to my house, a black cat bone,

Take my baby all the way from home,

Look at that doodle, where’s he been,

Up your house, and gone again.

Bo Diddley, Bo Diddley have you heard?

My pretty baby said she was a bird

Sorti en face B de «?I’m a Man?», le rythme hypnotique de «?Bo Diddley «?devient aussitôt sa marque de fabrique. Gros succès, il lance sa carrière.

«?Je ne pouvais pas imaginer que des gens jouaient pour de grosses sommes. Quand on m’a donné mon premier contrat, je suis resté debout toute la nuit à le regarder, tu ne pouvais pas me dire que quelqu’un allait vraiment me payer sept cents dollars pour que je joue une chanson. Sept cents dollars ! J’avais passé un mois entier à travailler à conduire un camion - je bossais dur - et on ne me donnait pas sept cents dollars pour ça. Ça n’avait pas de sens. J’ai regardé le contrat toute la nuit, je l’ai tourné dans tous les sens1.?»

Son style inspirera des générations de rockers, de Johnny Otis («?Willie and the Hand Jive?», 1957) au Clash («?Rudie Can’t Fail, 1979) et des milliers d’autres artistes. «?Bo Diddley?» peut aussi être considéré, avec quelques-uns de ses autres morceaux, comme l’embryon véritable du futur genre funk, dont il détient l’esprit et la lettre.

Rock and Roll

Tandis que ses amis Howlin’ Wolf et Muddy Waters, ses collègues de chez Chess, restent cantonnés au blues, fusse-t-il électrique, et que Chuck Berry devient en 1955 l’un des porte-drapeaux du rock ‘n’ roll, Bo Diddley restera inclassable. Avec «?Diddy Wah Diddy?» (enregistré plus tard par The Remains) composé avec le groupe vocal The Moonglows et Willie Dixon, il respecte les canons d’un rhythm and blues auquel il apporte une touche très personnelle. Mais avec sa très forte présence scénique, sa guitare électrique au premier plan et des tempos rapides comme «?Who Do You Love?», «?Hey! Bo Diddley?» ou «?Down Home Special?», Bo Diddley est considéré comme l’un des pionniers du rock and roll, un genre qui existe depuis longtemps mais qui est lancé avec succès sous ce nom par Little Richard, Elvis Presley10, Chuck Berry, Bill Haley & the Comets en 1955. Bo Diddley sera même considéré comme l’un des pionniers du punk rock avec des tempos ultra rapides comme «?Run Diddley Daddy?», «?Mumblin’ Guitar?», «?She’s «?Alright?» ou «?Craw-Dad?» (qui donnera son nom au club où les Rolling Stones connurent le succès, le Crawdaddy Club de Giorgio Gomelsky).

Rap

Bo Diddley est en outre l’un des premiers (avec Slim Gaillard, Louis Jordan, etc.) à avoir enregistré des morceaux assimilés au rap, un genre qui ne fera surface que dans les années 1970 et ne devrait pas être dissocié de la culture des DJ et de la piste de danse dont il sera véritablement issu. Mais «?Say Man?», un de ses succès de 1956, «?Say Man, Back Again?» et plusieurs autres titres mettent néanmoins en scène des dialogues ou des rimes enchaînées sur un ton parlé.

«?Ce sont les racines. Et je ne me considère pas comme étant la racine. Mais il faut bien des fondations. Et moi je dis que je suis les fon-dations sur lesquelles d’autres ont construit, comme la plupart des groupes d’aujourd’hui. Beaucoup de groupes noirs ont lancé ce truc mais dans la communauté noire, le rap c’est pas nouveau. Quand j’étais à l’école on appelait ça le «?signifying?». Ça veut dire que je vais parler de toi et à ton tour tu vas parler de moi de la même manière. Et on avait un groupe de gamins tout autour qui voulait voir qui était capable de parler le plus mal, tu vois ? Et à la fin, il y en avait un qui ne trouvait plus rien à répondre alors il disait un truc sur ta mère et ça se terminait en bagarre?! Ha ! Ha ! C’était «?d’accord, vas-y casse-moi et je te fous une raclée !?» Tu comprends ? Et l’autre trouvait un truc à répondre genre «?Oui si je te casse je vais te casser la gueule jusqu’à ce que j’en ai marre d’arrêter?» ! «?Dans «?Say Man?» on a nettoyé tout ça. Au lieu de «?Dis, mec j’ai vu ta copine?» et le type dit «?où ça ??» puis «?A half blew and the wind was blowing and a half blew in the streets?», avant c’était «?Dis, mec?» et le type dit «?quoi ??», «?J’ai vu ta maman !?» là c’était tout de suite… parce qu’on ne pouvait pas parler de ta mère. Tu peux dire tout ce que tu veux sur papa. Mais tu disais «?maman?» et tu prenais une raclée?! [rires] C’était comme ça ! Tu vois et on disait un truc sur la mère de quelqu’un style «?Mec ta mère est laide, elle est si moche qu’elle pourrait faire lever le jour avec un bâton !?» et là, il fallait que tu te battes ! J’ai une nouvelle chanson qui s’appelle «?Tu ES laid?», «?Tu es laid, mec, tu ne peux pas t’en empêcher?», un des vers c’est?: «?Dis, t’es tellement moche que ta mère a dû te mettre une côte de porc autour du cou pour que le chien accepte de jouer avec toi !1?»

Bruno Blum

© 2012 Frémeaux & Associés

Merci à Bo Diddley, Yves Calvez, Bernard Lepesant et Michel Tourte.

1. George R. White, «Bo Diddley, Living Legend», Castle Communications, Chessington, Surrey, U.K. 1995.

2. Une basse de fortune bricolée avec une lessiveuse crevée au centre, un manche à balai et une ficelle.

3. Selon Guy Nwogang, percussionniste camerounais travaillant notam-ment avec Manu Dibango et Stevie Wonder. Entretien avec l’auteur à Yaoundé en 2010.

4. Écouter «Marjorie’s Flirtation» de Lord Kitchener sur l’album Trinidad - Calypso 1939-1959 dans cette collection (FA5348).

5. Entretien avec l’auteur à Paris en 1984.

6. Écouter «Don’t Fence Her In» inclus sur Jamaica - Mento 1951-1958 (FA5275) dans cette collection.

7. Lord Tickler, «Limbo», disponible sur le volume Calypso 1944-1958 du coffret de dix disques Anthologie des Musiques de Danse du Monde (Frémeaux et Associés FA5342).

8. En 1974, son «Stop the Pusher» sur Big Bad Bo sera un des chefs-d’œuvre de la soul music.

9. Écouter Voodoo in America dans cette même collection (Frémeaux et Associés FA5375)

10. Écouter Elvis Presley face à l’histoire de la musique américaine (FA5361) dans cette collection.

In 1964, on The Beatles’ first visit to the U.S.A., there was a press conference. One of the questions thrown at John Lennon was, «What are you most looking forward to seeing here in America, John?» To which Lennon replied, «Bo Diddley.»

The ancestors of Ellas Bates, better known as Bo Diddley, were slaves from the cotton belt strapping the Mississippi Delta, and Bo, like Fats Domino, was a pure Creole product containing mixed blood: French, African and Blackfoot Indian. Bo was born on December 30th 1928 in McComb, Mississippi (he died in Archer, Florida, on June 2nd 2008); his mother Ethel Wilson came from a farm in the Deep South, and his father was named Eugene Bates, although Bo never knew him. Ethel was barely 16 when Bo was born; she couldn’t provide for her son and so he was entrusted into the care of his cousin Gussie McDaniel. When young Gussie’s husband died in 1934, The Depression left the family no choice but to migrate and, like many other Afro-Americans, they moved into the overpopulated ghettos of Chicago, the icy city lying to the north. Gussie adopted Bo so that he could go to school, which explains why the name which later appeared on countless records was Ellas McDaniel, one of the most covered composers in rock history. The Rolling Stones alone recorded six of his songs, including the titles Diddley Daddy, Craw-Dad, Crackin’ Up and I Need You Baby (aka «Mona») which you can find here, and Buddy Holly, of course, recorded «Not Fade Away» based on Bo’s famous «Mona». Mick Jagger was as big a fan as John Lennon, and he met Bo at the Marquee Club in London in 1962, right at the beginning of his own career. As for Bo’s opinion of Jagger & Co., «I’m not against him for shaking his wingy at the people and the kids and all this, because they used to say I used to do the same thing; and then I tried to clean it up because I didn’t think I was doing that, you know, but it’s cool; you know, the name of the game is to put on a show, and I think they’ve done a hell of a job.»

The Wilson/McDaniel family moved into the poor, violent South Side district of Chicago, a neighbourhood notoriously unfit for habitation where «You had to learn how to take care of yourself, or the kids would beat your brains out...1» Bo’s adoptive mother Gussie, a strict and pious woman, took him to church every day of the week, and it was at Ebenezer Missionary Baptist Church that he learned to sing and play the violin. He discovered he had a powerful voice, and when he was 12 his sister Lucille gave him a guitar for Christmas. He tried to play blues on the violin, but when he wanted to adapt Joe Liggins’ «Honeydripper» for his fiddle, his music-teacher hit him with the bow, breaking it over his back. Bo tried the trombone when he was 15, playing in the church-group for two years, and then began playing his guitar using his violin-technique, which had given him a speedy right wrist. But his hands were enormous and they barred him from fingering with any subtlety. The technique he adopted was highly personal, based on rhythm played frenziedly over an open tuning in E which allowed him to shape his chords with a single finger laid across the neck. His style was immediately unique. At school he learned how to make a violin, and then a double bass and a guitar before setting up a group known as The Hipsters (one of Nat «King» Cole’s cousins played washtub bass). His mind made up, Bo quit school at 16 and became a local handyman, repairing anything he could find to make some money – roofs, radios, cars – while other kids played basketball. His schoolmate Earl Hooker busked on street-corners playing the guitar, and so The Hipsters did likewise. He had a friend called Sandman who used to play rhythm, shaking a tray covered with sand... Bo’s family didn’t like him to play the guitar, nor did they like him listening to the blues – Baptists said it was the devil’s music – and soon Bo stopped attending church. He loved Louis Jordan and Nat Cole, and he found John Lee Hooker’s simple guitar-playing an inspiration. Although he was under age, he sneaked into clubs to hear Muddy Waters and Little Walter whenever they were in town; Bo, twelve years his cadet, admired Muddy.

The Hipsters had to play on the streets without Bo’s family knowing. When the money started coming in they were pursued by local gangs after they’d finished playing, and had to fight to defend themselves. They were arrested for carrying knives. They weren’t old enough to drive, either, but they still bought a 1937 Buick as a getaway car. The band changed its name to the Langley Avenue Jive Cats, and they won several amateur talent-contests; they won so often that soon they were barred from entering other competitions... Bo was strong and could handle himself: he became an amateur boxer and got married to a girl named Louise... who told him he had to stop boxing. The marriage didn’t last. He did all kinds of work, remarried in 1949 (to Ethel «Tootsie» Smith), and worked in a road-gang for five years while continuing to play on the street to supplement his low wages. When virtuoso harmonica-player Billy Boy Arnold joined the group in 1950-52, that didn’t last either: Billy Boy quit due to their «lack of ambition».

The Bo Diddley Beat

Lack of ambition was Arnold’s opinion. Bo and his group played tunes by Sonny Boy Williamson and Muddy Waters’ «Rollin’ Stone» as well as Bo’s own compositions. His first amplifier was made from bits of a record-player, and then he bought himself a real one, a Silvertone which he modified to take out the distortion when the volume was high: «I was lookin’ to get a bigger sound, an’ I came up with that «freight train drive» - that’s what I call it. There were three of us, an’ I developed a style that would make us sound like six people at least... It’s power-packed all the way. Pure energy.»1

He also built his own sound-effects, and his box would be a decisive tool: he created a tremolo-effect for the guitar even before Diamature put their own on the market: «It was a trip tryin’ to play with the sound disappearin’ an’ comin’ back - you get all out of step - but I learned to play with it, an’ when I learned that, that was the greatest thing in the world, an’ I made that sucker work for what I needed it for […] I was the first one to start usin’ that in R&B, rock ‘n’ roll, whatever you wanna call it. Nobody else was doin’ it.» 1

They didn’t use drums but hired their downstairs-neighbour Jerome Green to play maracas, borrowing from the «calypso» tradition that was popular at the time. When people asked him what kind of music he was playing, he said, «I have no idea. I play it, that’s all.» 1

The famous Bo Diddley Beat rhythm made him famous and conquered English rock music, from «Not Fade Away», The Rolling Stones’ first Top Three record (Feb. ‘64) to The Who’s «Magic Bus» (1968). Twenty years later it characterized George Michael’s «Faith» (1987). It was actually based on a rhythm «spread throughout the coastal areas of West Africa2» which can be found in the percussion of Jamaican Mento, Trinidadian Calypso3 and the beguines of Martinique and Guadeloupe. It is sometimes also heard played by the clave in the Cuban genres called son, rumba, guaracha or sucu sucu. You can hear it in the 1951 version of «Tin Tin Deo» played by Dizzy Gillespie’s Afro-Cuban Orchestra with John Coltrane and Milt Jackson.

According to Bo Diddley, his special rhythm was «a mixture of a chant, blues/rhythm and blues and spiritual.4» which he created spontaneously, influenced by the rhythms he heard in church, but even he wasn’t sure of that influence: «I’d say it was a «mixed-up» rhythm: blues, an’ Latin-American, an’ some hillbilly, a little spiritual, a little African, an’ a little West Indian calypso… an’ if I wanna start yodelin’ in the middle of it, I can do that, too. I like gumbo, you dig? Hot sauces, too. That’s where my music comes from: all the mixture. I got those beats so jumbled up on ‘Bo Diddley’ that they couldn’t sort ‘em out!» 1

It’s more probable that this famous rhythm of his — you can hear it on the guitar in Bo Diddley, Pretty Thing, Cadillac, Bucket, Limbo or I Need You Baby — came from Jamaican Mento, which first appeared on records in The United States in the Fifties5. Limbo (1959), heard on this album, borrows its chorus and part of its lyrics – as well as its rhythm – from a Mento song with the same title6. The limbo, incidentally, is the acrobatic exercise where dancers have to arch themselves backwards underneath a bar constantly lowered throughout the dance; it was part of the fashionable «calypso» gear on the beaches of Jamaica and Trinidad throughout the Fifties.

Bo Diddley was still poor, with a wife and a baby and rent to pay, and he scraped through by giving concerts; but in 1954 he still hadn’t thought of tur-ning professional. He would do anything to survive: he sold drinks, drove garbage-trucks, worked in cold storage for a butcher wholeseller, built roads and houses, played in bars at weekends, even on the street... Musicians who could use their sense of humour were an inspiration to him, most of all the essential Louis Jordan (Bo played his «Caldonia» for a while). There was Cab Calloway’s «Hey Ba Ba Rebop» too, and the Joe Liggins instrumental «Honeydripper», together with some blues, but Bo thought Muddy Waters or John Lee Hooker did them better than he could, and so he set his mind to work on everything that was different in his playing; he stopped playing «covers» so that he wouldn’t have any rivals when looking for gigs.

«Nobody can write songs for me. Because they don’t understand it. First, you got to just hang around me for a while and figure out how I do things. See, a lot of people have tried to copy my stuff and they misinterpret it. They did all right. But I’ll tell it like this, when I go to play with a band, and the drummer get up and start doin’ the drums, the Bo Diddley beat, and I have to tell him ‘uh-uh, ah-ah, that ain’t the way it go.’ Then I have to go on the set on the drums, and show him the way that it was done. The right beat is on the original. That’s ‘Bo Diddley’. […] The Bo Diddley beat has so many different approaches [he starts playing on the table with his fingers, alternating two different rhythm patterns.] See, a lot of people got this here [he plays more, this time repeating the same single pattern] – that’s wrong.» (From an interview with the author in Paris in 1990).

His musicians changed frequently but at the end of 1954 he hired a drummer, Clifton James. Bo’s wife gave in to her husband’s determination to play his own music, and his original formula began to gain popularity. He was still a construction-worker that summer (work halted when the rigours of the Chicago winter set in) but when Billy Boy Arnold rejoined the band he finally persuaded Bo (in around February ‘55) to record a demo. It was turned down by United Records.

Chicago Blues

The Chess brothers, Leonard and Phil, ran the independent Chess Records label, a family business that produced jazz records and jump-blues-style rock ‘n’ roll. In the northern States Chess also distributed Sun Records, which would launch Elvis Presley’s first single the following summer. The Chess brothers also produced the King of Chicago Blues, Muddy Waters – he was their stable’s star – and his virtuoso harmonica-player Little Walter. Leonard & Phil had a little studio in their office, and also all the equipment needed to press their records and print their own labels. Bo’s group was given two days to rehearse, and they went straight on to record I’m a Man and three other titles at Universal Recording Studio. Bo Diddley himself said that I’m a Man was based on Muddy Waters’ 1951 tune «She Moves Me»; Muddy liked I’m a Man, and in turn used it as the basis for his own composition «Mannish Boy» on the same subject, only with a different melody and riff.

Leonard Chess substituted washtub-bassist Roosevelt Jackson with rhythm and blues veteran Willie Dixon, who played a stand-up double bass (you can hardly hear him on the first four titles). The instant it was released, I’m a Man made Bo Diddley a «name» as a newcomer on the Chicago blues scene; the song was later picked up by Jimi Hendrix, The Who, The Yardbirds, Dr. Feelgood… and countless others.

The song I’m Bad, a parody of I’m a Man, hammered the blues nail home. Most of the pieces Bo recorded were remarkably well-sung, and they had both the feeling and the sound of the blues, with Billy Boy Arnold on harmonica, Otis Spann on piano and, on bass, the great Willie Dixon, who was also a songwriter-composer. The latter pair also featured on many recordings made by Muddy, Sonny Boy Williamson II, Howlin’ Wolf and Chuck Berry, who joined Chess in 1955 (and began with a bang when he released «Maybellene», his first hit). Steeped in spirituals and Baptist gospel (Don’t Let It Go), plunging its roots into the Delta where it was born, the music of Bo Diddley at once imposed itself as a reference for the urban, electric Chicago blues of the north, along with the records of other giants such as Sonny Boy, Little Walter, Muddy, Elmore James, Buddy Guy, J.B. Lenoir, Big Walter Horton et al. Many compositions dating from his studio debuts would remain blues classics, among them You Don’t Love Me (You Don’t Care), Bring It to Jerome, Little Girl, Roadrunner or Blues, Blues. Bo’s splendid She’s Fine (She’s Mine) would be recorded in Memphis in 1960 by Willie Cobbs, who changed its title and made it a hit as «You Don’t Love Me». Other artists picked it up, including The Allman Brothers, who put it on their famous 1971 album At Fillmore East, and reggae artist Dawn Penn. Creedence Clearwater Revival joined the queue, making a classic of Before You Accuse Me, and The Stones did Cops and Robbers – they only knew Bo’s version, but he’d got it from Boogaloo and his Gallant Crew – which they never released; but it did circulate widely as a bootleg. Rare, also, are the records made by but not written by Bo Diddley; he wanted to remain «original» – it was his strength – and he always refused to be categorized a «blues» or even «rock ‘n’ roll» artist. He was nothing if not Bo Diddley. As for his creativity, it had no limits, and this alone made it impossible to find a suitable «file under» category between blues, soul7, funk, rock, punk rock, rap, and rhythm and blues... even comedy song for that matter.

Funk

It might be worth remembering here that Bo Diddley was still Ellas McDaniel according to his birth-certificate; when the time came to record their first 45rpm single, bassist Roosevelt Jackson laughingly suggested that he should change the «Ellas McDaniel» into «Bo Diddley», a funny nickname that recalled the «bow-legged rooster» in their song «Uncle John» (see below). A diddley bow was also familiar to Americans: a rudimentary instrument with a single string fixed to a bow, no doubt inherited from the single-string zithers or ideochords common to the Gabon-Cameroon region. After being reassured that there was nothing racist about the new name – the verb «to diddle» means «to cheat» (there are other sexual meanings) – Leonard Chess accepted it and Ellas McDaniel became officially Bo Diddley. The name stuck: «I can’t tell you exactly what it means, but it kinda means ‘bad boy’ - mischievous, you know. I used the name when I started to foolin’ around in Eddie Nicholson’s gym, but I only used it in the ring: all of my friends called me ‘Mac’.» 1 «Bo Diddley» was the name given to a tune they recorded at his first session — up until then, the song was «Uncle John» —, and it needed some last-minute changes to the original risqué lyrics (although everyone knew the sexual connotation of a «John»):

Uncle John got corn ain’t never been shucked / Uncle John got daughters ain’t never been… to school / The bow-legged rooster told the cock-legged duck / You ain’t good lookin’ but you sure can... crow!

Bo borrowed the melody and the first verse of Red Saunders’ nursery rhyme-derived «Hambone» (1952), slapped it onto his «beat» and created Bo Diddley to sing of how his wife cheated on him with a doodle using a mojo, or hoodoo (voodoo) amulet made from a black cat’s bone8:

Mojo come to my house, a black cat bone / Take my baby all the way from home / Look at that doodle, where’s he been / Up your house, and gone again. / Bo Diddley, Bo Diddley have you heard? / My pretty baby said she was a bird.

Released as the B-side of I’m a Man, the hypnotically rhythmic Bo Diddley launched Bo’s career: «It never dawned on me that people played for big money. The first contract I got, I sat all night lookin’ at it... Seven hundred dollars! I worked all month drivin’ a truck - an’ I mean worked - an’ I didn’t get no seven hundred dollars! I turned it upside-down, I turned it sideways. I knew there was a seven, but I thought it might have been a misprint.»1 Bo’s style inspired thousands, including The Clash, and Bo Diddley, like a few others in his repertoire, can be considered as an embryonic funk title: the form/spirit is there, and so is the content.

Rock and Roll

Whereas his Chess stable-mates (and friends) Howlin’ Wolf and Muddy Waters were staying with the blues, albeit electric, and Chuck Berry became rock ‘n’ roll’s flag-bearer in 1955, Bo Diddley remained outside any category, i.e. he was still Bo Diddley. With Diddy Wah Diddy (composed with The Moonglows and Willie Dixon), Bo respected a rhythm and blues canon to which he brought a quite personal touch. But thanks to his extraordinary stage presence — with his guitar to the forefront on rapid-tempo songs like Who Do You Love, Hey! Bo Diddley or Down Home Special — Bo Diddley was considered one of rock ‘n’ roll’s pioneers. The genre had been around for a while, but it really took off in 1955 with the likes of Little Richard, Elvis Presley, Chuck Berry and Bill Haley & The Comets. Bo Diddley would even be considered a pioneer of punk rock, with his ultra-fast tempos on Run Diddley Daddy, Mumblin’ Guitar, She’s Alright or Craw-Dad (Giorgio Gomelsky’s Crawdaddy Club, where The Stones were a hit, took its name from the latter).

Rap

In addition to the above, Bo Diddley was one of the first artists — with Slim Gaillard, Louis Jordan, etc. — to record pieces which can be put in the same class as rap, a genre which would only surface in the ‘70s, and which came out of the DJ and dance-floor cultures. But Say Man, one of Bo’s 1956 hits, plus Say Man, Back Again and several other titles, were all notable for dialogue and rhymes strung together conversationally…

«Well it has to be roots. And I don’t consider myself as the roots. Roots is, there has to be a foundation. And I say that I was the foundation that somebody else built on. Like most of the groups today, you know, and a lot of black groups started this thing but, see, in the black community, rap is nothing new. When I was in school we used to call it ‘signifying.’ It meant that I talk about you like you talk about me awhile. And we have a bunch of kids standing ‘round, see who could speak the baddest, you understand...? See, we’d say something like that about somebody’s mother, man, say ‘Man, your momma’s ugly, she ugly enough to break daylight with a stick!’ The cat… you’d have to fight man! I’ve got a brand new one that’s coming up called ‘You ARE ugly’. A brand new one called ‘You ugly man, you can’t help it’. And one of the lines is ‘Say, you so ugly ‘til your momma had to put a pork chop around your neck so the dog will play with you!’»8

Adapted in English by Martin Davies

Bruno Blum

© 2012 Frémeaux & Associés

Thanks to Bo Diddley, Yves Calvez, Bernard Lepesant and Michel Tourte.

1. George R. White, «Bo Diddley, Living Legend», Castle Communications, Chessington, Surrey, U.K. 1995.

2. Guy Nwogang (a Cameroon percussionist who works with Manu Dibango and Stevie Wonder among others), in an interview with the author in Yaoundé in 2010.

3. Listen to «Marjorie’s Flirtation» by Lord Kitchener on the album Trinidad - Calypso 1939-1959 in this same collection (FA5348).

4. In a 1984 interview with the author in Paris.

5. Listen to «Don’t Fence Her In» on Jamaica - Mento 1951-1958 (FA5275).

6. Lord Tickler, «Limbo», available on the Calypso 1944-1958 volume of the 10CD set Anthologie des Musiques de Danse du Monde (FA5342).

7. In 1974, his «Stop the Pusher» on Big Bad Bo would be a soul music masterpiece.

8. Listen to Voodoo in America in this same collection (Frémeaux FA5375).

9. Listen to Elvis Presley face à l’histoire de la musique américaine (FA5361) in this same collection.

All songs written by Ellas McDaniel except «Diddley Daddy» (Ellas McDaniel, Harvey Fuqua), «Bring it to Jerome» (Jerome Green), «Diddy Wah Diddy» (Willie Dixon), Ed Sullivan & Dr. Jive introduction (Ed Sullivan & Tommy Smalls) «Cops and Robbers» (Kent Levaughn Harris) and «I’m Sorry» (Ellas McDaniel, Harvey Fuqua, Alan Freed).

Discographie 1

1. I’m a Man

2. Little Girl

3. Bo Diddley

4. You Don’t Love Me (You Don’t Care)

Ellas McDaniel as Bo Diddley-g,v; William Arnold aka Billy Boy Arnold-hca; Otis Spann-p; Willie Dixon-b;Clifton James-d; Jero-me Green-maracas. Universal Recording, Chicago, March 2, 1955.

5. Diddley Daddy

Bo Diddley-g,v; Marion Walter Jacobs aka Little Walter-hca; Otis Spann-p; Willie Dixon-b; Clifton James-d; Jerome Green-maracas; The Moonglows-v : Harvey Fuqua, Bobby Lester, Prentiss Barnes, Alexander Graves aka Pete. Chess Studio, Chicago, May 15, 1955.

6. She’s Fine, She’s Mine aka (No No No)

You Don’t Love Me

Bo Diddley-g,v; William Arnold aka Billy Boy Arnold-hca; Willie Dixon-b; Clifton James-d; Jerome Green-maracas; Chess Studio, Chicago, May 15, 1955.

7. Pretty Thing

8. Heart-O-Matic Love

9. Bring it to Jerome

10. Spanish Guitar

Bo Diddley-g, v; Jerome Green-maracas, v. on 9; Lafayette Leake-p; Willie Dixon-b; Clifton James-d. Universal Studios, Chicago, July 14, 1955.

11. Dancing Girl

12. Diddy Wah Diddy

13. I’m Looking for a Woman

Bo Diddley-g, v; Jodie Williams, g; Willie Smith aka Big Eyes as Little Willie Smith-hca (12 only); Lafayette Leake-p; Willie Dixon-b; Clifton James-d; Jerome Green-maracas. Chess Studio, Chicago, November 11, 1955.

14. I’m Bad

15. Who Do You Love

Bo Diddley-g, v; Jody Williams-g; Clifton James-d; Jerome Green-maracas. Chess Studio, Chicago, May 5, 1956.

16. Cops and Robbers

17. Downhome Special

Bo Diddley-g, v; Jody Williams-g (16 only); Otis Spann-p (17 only); Willie Dixon-b; Clifton James-d; Jerome Green-maracas, v. on 18; unknown-whistles. Universal Recording, Chicago, May 24, 1956.

18. Hey Bo Diddley

19. I Need You Baby

Bo Diddley-g, v; Peggy Jones as Lady Bo-g, v (18 only); Clifton James or Frank Kirkland-d; Jerome Green, maracas; The

Flamingos: Nate Nelson, Tommy Hunt, Terry Johnson, Paul Wilson, Jake Carey-v. Beltone Studios, New York City, February 8, 1957.

20. Ed Sullivan & Dr. Jive introduction

Ed Sullivan-introduction;Tommy Smalls aka Dr. Jive-MC;

21. Bo Diddley (live)

Bo Diddley-g, v; probably Bobby Parker-g; Clifton James-d; Jerome Green-maracas. Recorded on November 20, 1956 at the Ed Sullivan Show, CBS TV Studio 50, New York City. Note: slight sounds skips at the end of the song are due to the original sound source.

Discographie 2

1. Say Boss Man

2. Before You Accuse Me

Bo Diddley-v, g; Peggy Jones as Lady Bo-g (1 only); Lafayette Leake-p; Clifton James or Frank Kirkland-d; Jerome Green-maracas; Probably The Moonglows (overdub on 1 only): Harvey Fuqua, Bobby Lester, Prentiss Barnes, Alexander Graves aka Pete-v. Chess Studio, August 15, 1957.

3. Say Man

4. Hush Your Mouth

5. Bo’s Guitar

6. Dearest Darling

Bo Diddley-v, g; Lafayette Leake-p; Peggy Jones as Lady Bo-g; Willie Dixon-b (3 & 6 only); Frank Kirkland-d; Jerome Green-maracas, lead vocals duet on 3.

7. Willie and Lillie

8. Bo Meets the Monster

Bo Diddley-v, g; Peggy Jones as Lady Bo-g; Frank Kirkland-d; Jerome Green-maracas, v on 8. New York City, September 1958.

9. Crackin’ Up

10. Don’t Let It Go

11. I’m Sorry

12. Oh Yea

13. Blues, Blues

14. The Great Grandfather

Bo Diddley-g, v, overdubbed background vocal on 9, 10 & 11; Lester Davenport-hca; Peggy Jones as Lady Bo-g (13 only), v (overdubbed background vocal on 9, 10 & 11); Lafayette Leake-p; Willie Dixon-b; Clifton James or Frank Kirkland-d; Jerome Green-maracas, overdubbed background vocal on 9, 10 & 11. Bell Sound Studios, New York City, 1958.

Note : « The Great Grandfather » was probably recorded at that session.

15. Mama Mia

16. Bucket

17. Lazy Woman

18. Come on Baby

Bo Diddley-g, v; Peggy Jones as Lady Bo-g (15 & 17 only); Lafayette Leake-p; Willie Dixon-b; Clifton James or Frank Kirkland-d; Jerome Green-maracas. Chess Studio, Chicago, February 1959.

19. Nursery Rhyme (Puttentang)

20. Mumblin’ Guitar

21. I Love You So

Bo Diddley-g, v; Peggy Jones as Lady Bo-g (19 only); Clifton James or Frank Kirkland-d; unknown-tambourine. Chess Studio, Chicago, spring 1959.

Discographie 3

1. Story of Bo Diddley

2. She’s Alright

3. Limber

4. Say Man, Back Again

5. Run Diddley Daddy

Bo Diddley-v, g, overdubbed background vocal on 3; Peggy Jones as Lady Bo-g, overdubbed background vocal on 3; Lafayette Leake-p; Willie Dixon, b; Clifton James or Frank Kirkland-d; Jerome Green, maracas, overdubbed background vocal on 3. Chess Studio, Chicago, September 1959.

6. Road Runner

7. Spend my Life with You*

Bo Diddley-g, v, overdubbed background vocals; Peggy Jones as Lady Bo-g (6 only), overdubbed background vocals; Otis Spann, p; Bobby Baskerville-b, overdubbed background vocals; Clifton James, d: Jerome Green, maracas, overdubbed background vocals. Chess Studio, Chicago, September 1959.

8. Love You Baby

9. Diddling

10. Cadillac

11. Limbo

Bo Diddley-g, v; Peggy Jones as Lady Bo-g (10 & 11 only), v (10 & 11 only); Gene Barge-ts; Clifton James, d. Bo Diddley, Jerome Green, Lady Bo-overdubbed background vocals on 8. Probably New York City, October 1959.

12. Look at me Baby*

13. You Know I Love You

14. Let Me in

15. Signifying Blues

16. Live my Life

17. Scuttle Bug

18. Love Me

19. Deed and Deed I Do

20. Walkin’ and Talking

21. Travelin’ West

Bo Diddley-v (except 13 & 17), g; Peggy Jones as Lady Bo-g, p (18 only); Otis Spann, p (12, 15, 16, 19, 20, 21 only, and piano overdub on 17); Bobby Baskerville-b; Clifton James-d; Jerome Green-maracas (12, 13, 15, 16, 19, 20, 21 only), v (15 only); Johnny Carter, Lady Bo, Harvey Fuqua, members of The Moonglows (probably Chester Simmons, Reese Palmer, James Nolan Chuck Barksdale and Marvin Gaye) -overdubbed background vocals on 13; Bo Diddley, Jerome Green, Lady Bo-overdubbed background vocals on 14, 16 19, 20, 21; unknown-tambourine. Washington D.C., January, 1960.

22. Craw-Dad

Bo Diddley fut sans doute le musicien de rhythm and blues le plus original des années 1950-60. Chanteur remarquable, compositeur prolifique extrêmement influent, homme de scène, souvent comique, Bo Diddley était un guitariste rythmique révolutionnaire aux innovations stylistiques autant que techniques. Inclassable visionnaire, il est le père spirituel de nombreux artistes, qui de la soul au rap, en passant par le blues, le rock and roll et jusqu’au punk rock, se reconnaissent dans ce génie débridé. Bruno Blum nous présente un authentique monument de la musique populaire du XXème siècle.

Patrick FRÉMEAUX

Bo Diddley was probably the most original rhythm & blues musician of the Fifties and Sixties. He was a remarkable singer, a prolific composer who left his mark in everyone’s songbook, an (often very funny) stage-personality... not to mention a revolutionary rhythm-guitarist whose innovations were both stylistic and technical. A visionary who defied all attempts to classify him, he became a spiritual father to many artists, from soul-singers to rappers, blues, rock and roll and even punk-rock figures, who all seemed to recognise themselves in Bo’s unbridled genius. This selection of his recordings compiled by Bruno Blum proves his status as a genuine monument in 20th century popular music.

Patrick FRÉMEAUX

CD THE INDISPENSABME BO DIDDLEY 1955-1960, ARTISTE BO DIDDLEY © Frémeaux & Associés 2012 (frémeaux, frémaux, frémau, frémaud, frémault, frémo, frémont, fermeaux, fremeaux, fremaux, fremau, fremaud, fremault, fremo, fremont, CD audio, 78 tours, disques anciens, CD à acheter, écouter des vieux enregistrements, albums, rééditions, anthologies ou intégrales sont disponibles sous forme de CD et par téléchargement.)