- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

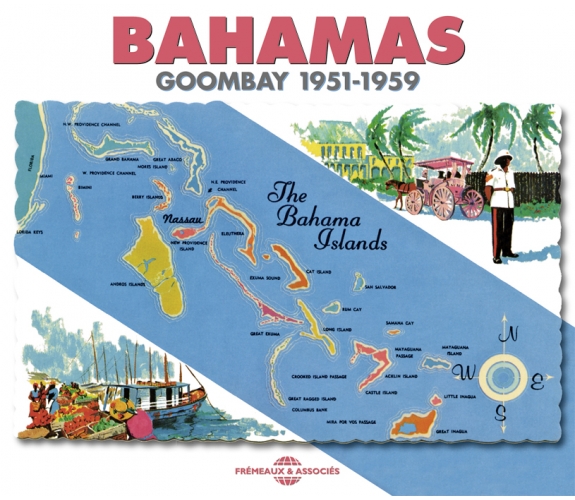

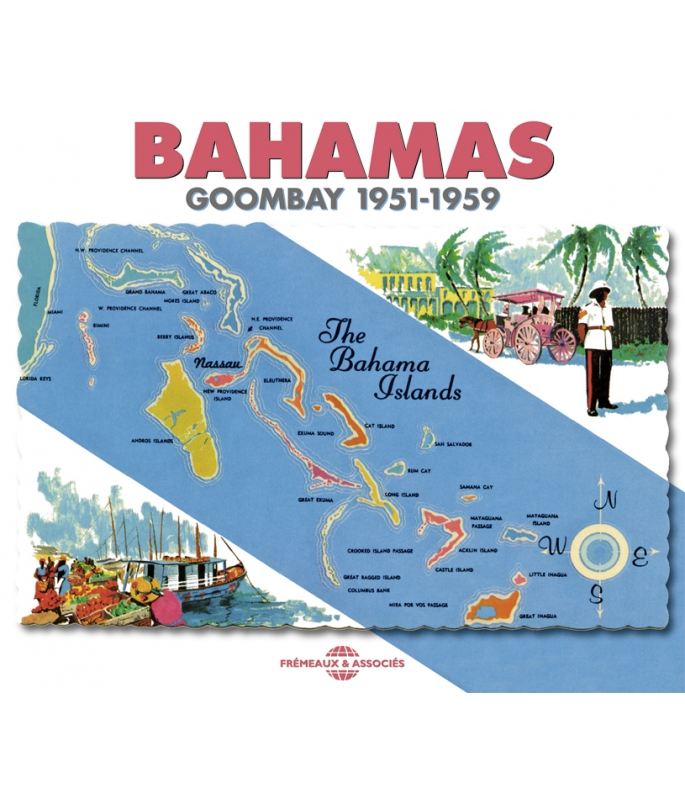

GOOMBAY - AVEC BLIND BLAKE, GEORGE SYMONETTE, CHARLIE ADAMSON…

Ref.: FA5302

Artistic Direction : BRUNO BLUM & FABRICE URIAC

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Total duration of the pack : 1 hours 48 minutes

Nbre. CD : 2

GOOMBAY - AVEC BLIND BLAKE, GEORGE SYMONETTE, CHARLIE ADAMSON…

GOOMBAY - AVEC BLIND BLAKE, GEORGE SYMONETTE, CHARLIE ADAMSON…

Just off the Florida coast, Bahamian Goombay music is a succulent hybrid, somewhere between rhythm and blues, Trinidadian calypso and Jamaican mento, yet it comes from The Bahamas, where it lives on as a separate style. The presence of world-class, English-language composers and performers Blind Blake Higgs, George Symonette or Charlie Adamson made the sounds of Nassau a Golden Age, filled with unique charm and tropical dreams. The sound fell into oblivion for half a century, but Bruno Blum (with the help of Fabrice Uriac) has finally reunited these gems of authentic goombay music, a magical concentrate of this island paradise. Patrick FRÉMEAUX

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1JP MorganBlind Blake & His Royal Victorian Hotel Calypso Orchestra00:02:431951

-

2Jones Oh JonesBlind Blake & His Royal Victorian Hotel Calypso Orchestra00:02:471951

-

3Yes Yes YesBlind Blake & His Royal Victorian Hotel Calypso Orchestra00:02:551951

-

4Run Come See JerusalemBlind Blake & His Royal Victorian Hotel Calypso Orchestra00:02:581951

-

5Lord Got TomatoesBlind Blake & His Royal Victorian Hotel Calypso Orchestra00:02:591951

-

6Uncle JoeVincent Martin & His Bahamians00:02:591957

-

7Coconut Water Rum and GinVincent Martin & His Bahamians00:02:341957

-

8Is It That You Really Love MeCharlie Adamson00:01:541957

-

9Eatin' Too Much EmilyCharlie Adamson00:01:151957

-

10My Lima BeansGeorge Symonette00:02:531954

-

11Sponger MoneyGeorge Symonette00:02:391954

-

12Stone Cold Dead In the MarketVincent Martin & His Bahamians00:02:321957

-

13Zombie JamboreeVincent Martin & His Bahamians00:03:151957

-

14Bahama Brown BabyHarold Mc Nair00:02:401956

-

15The Cigar SongBlind Blake & His Royal Victorian Hotel Calypso Orchestra00:02:261952

-

16Peas and Rice Little NassauBlind Blake & His Royal Victorian Hotel Calypso Orchestra00:02:491957

-

17I Need ItEloïse Davis00:01:301956

-

18Liza See Me HereThe Percenties Brothers00:02:371953

-

19Moonlight In NassauBlind Blake & His Royal Victorian Hotel Calypso Orchestra00:02:351957

-

20On A Tropical IsleBlind Blake & His Royal Victorian Hotel Calypso Orchestra00:02:451957

-

21Bimini GalThe Percenties Brothers00:02:501953

-

22The Briland RumbaThe Percenties Brothers00:02:421953

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Bullfrog Dressed In Soldier's ClothesDelbon Johnson00:01:531953

-

2Gombay RockBlind Blake & His Royal Victorian Hotel Calypso Orchestra00:02:591957

-

3Nassau NightsDelbon Johnson00:02:361953

-

4Sly MoongooseDelbon Johnson00:02:171953

-

5Nassau SambaGeorge Symonette00:02:361953

-

6Nassau MerengueAndré Toussaint00:01:541956

-

7Come to the CarribeanFreddie Mummings and his Silver Slipper Orchestra00:02:161955

-

8Noise In the MarketFreddie Mummings and his Silver Slipper Orchestra00:01:391955

-

9Pretty BoyGeorge Symonette00:02:101954

-

10GoombayAndré Toussaint and Georges Symonette00:02:521956

-

11Dance the GoombayCharlie Adamson00:02:271957

-

12BangaleeBlind Blake & His Royal Victorian Hotel Calypso Orchestra00:02:121957

-

13Nassau CallingBlind Blake & His Royal Victorian Hotel Calypso Orchestra00:01:561953

-

14Little NassauGeorge Symonette00:02:461953

-

15La CruzBlind Blake & His Royal Victorian Hotel Calypso Orchestra00:02:241956

-

16Bahamian Brown BabyBlind Blake & His Royal Victorian Hotel Calypso Orchestra00:02:351959

-

17CamillaGeorge Symonette00:02:351954

-

18Spirit RumBlind Blake & His Royal Victorian Hotel Calypso Orchestra00:02:241957

-

19At the Iron BarBlind Blake & His Royal Victorian Hotel Calypso Orchestra00:01:511957

-

20Boat Pull OutGeorge Symonette00:02:321954

-

21DigbyFreddie Mummings and his Silver Slipper Orchestra00:02:271955

-

22Coconut WomanFreddie Mummings and his Silver Slipper Orchestra00:02:171957

Les Bahamas

Les Bahamas

Les sept cents îles des Bahamas forment un pays anglophone du Commonwealth indépendant depuis 1973. L’archipel est situé à l’extérieur de la mer des Caraïbes, face à la côte nord-est de Cuba, à l’est de la péninsule de Floride. Les petites îles Bimini ne sont qu’à 75 km de Miami. Au sud, l’île d’Inagua n’est qu’à un peu plus de cent kilomètres de Haïti. La capitale Nassau se trouve sur l’île de New Providence, siège de centaines de banques offshore réputées pratiquer, pour certaines, le blanchiment d’argent. L’activité bancaire est très développée aux Bahamas, où les impôts sont très bas. La chanson J.P. Morgan fait ici référence à l’une de ces grandes banques d’affaires. Avec la proximité de Miami, l’industrie touristique marque beaucoup la culture du pays. Les vacanciers fournissent indirectement les revenus de la majorité de la population. Logi quement, la mus ique festive trouve un public largement composé de touristes, pour la plupart états-uniens. Avec le succès du calypso trinidadien dans les années 1940-501, les différentes musiques anglophones de la région des Caraïbes ont souvent été étiquetées calypso alors qu’elles sont en fait distinctes de celles de Trinité-et-Tobago. Le nom du groupe bahaméen Blind Blake & His Royal Victorian Hotel Calypso Orchestra est un exemple de cette étiquette, alors que Blind Blake est sans doute l’artiste majeur du goombay, le véritable nom de la musique populaire des Bahamas de l’aprèsguerre. Sur Digby, Freddie Munnings fait rimer “calypso” avec “Nassau” ; le cabaret Dirty Dick’s (du nom d’un très vieux pub londonien) de Nassau, ouvert en 1922, renvoie au Dirty Dick’s, haut-lieu du calypso à la Trinité. Avec le succès de son album Calypso en 1956, le new-yorkais d’origine jamaïcaine Harry Belafonte rendra encore plus incontournable cette classification “calypso” pour les musiques des Antilles anglo-américaines2.

Les racines du goombay

La première terre américaine où Christophe Colomb mit le pied en 1492 fut l’île bahaméenne de San Salvador où, comme en Jamaïque et à Cuba, vivaient les Indiens Taïnos (de langue Arawak) dont quelques traditions musicales, comme la danse areito (une partition est archivée à Cuba), auraient perduré sur des îles reculées. En moins d’un siècle, les Indiens ont été décimés par la variole et les mauvais traitements apportés par des colons espagnols. Les Bahamas ont ensuite été habitées par de rares Européens avant que des Anglais ne les investissent à la fin du XVIIIe siècle. Ces îles coraliennes peu fertiles ne furent peuplées qu’à partir de la guerre d’indépendance des États-Unis (1771-1776), quand des Britanniques loyaux à la Couronne d’Angleterre ont fui le continent et ont amené avec eux un grand nombre d’esclaves d’origine ouest-africaine. Après l’abolition de l’esclavage (1838), d’autres réfugiés, cette fois des Sudistes, se sont réfugiés aux Bahamas avec leurs esclaves lors de la guerre de Sécession (1861-1865). Au début du XIXe siècle, les danses et musiques des esclaves étaient encore interdites sous peine d’amende pour leurs maîtres. Les autorités coloniales anglaises redoutaient la communication et les organisations secrètes entre personnes asservies. Tout rapprochement et réunions entre Africains étaient des menaces potentielles. La révolution haïtienne toute proche (1801) faisait trembler les esclavagistes et les esclaves n’avaient pas le droit de lire, d’écrire, d’enseigner ou de prêcher. Aux Antilles britanniques, les rites de la spiritualité africaine avaient été strictement interdits en 1761 sous peine de mort ou d’exil. Ces danses, tambours et chants traditionnels étaient réputés être utilisés dans des rituels obeah, une forme de spiritualité considérée par les colons comme étant de la sorcellerie. En réalité ces groupes pratiquaient en musique des dérivés des cultes des esprits originaires notamment des peuples Ashanti, Yoruba, et leurs rites secrets interdits dont Hollywood s’est emparé en scénarisant la mythologie des zombies pour des films d’horreur tels La Nuit des morts-vivants de George A. Romero (1968). Écrit et enregistré en 1953 par Lord Intruder, un calypsonien originaire de Tobago, le Zombie Jamboree de Vincent Martin tourne ici ces légendes en dérision. Parfois appelé Back to Back, ce classique antillais a également été enregistré par le Kingston Trio de Californie, par The Charmer (alias Louis Farrakhan) de Boston, et par plusieurs Jamaïcains, dont les Wrigglers, Lord Jellicoe, les Hiltonaires et Count Frank. Toute musique africaine étant prohibée avant 1838, le statut de travailleur forcé permit néanmoins à quelques afro-bahaméens de jouer des instruments européens disponibles. Les musiciens anglais étaient rares dans les îles, et certains esclaves de maison ont ainsi reçu une éducation musicale à l’européenne, destinée à égayer les soirées des maîtres, notamment à Noël. Les aptitudes musicales des esclaves étaient même mises en valeur lors de leur vente publique. De l’autre côté de l’échelle sociale à cette époque, les aristocrates anglais des deux sexes se devaient de maîtriser un instrument. Ils interprétaient des madrigaux au luth, au dulcimer et au clavecin. Le violon, populaire chez les nobles comme chez les roturiers, est ainsi apparu sur quelques îles. Les autres instruments en vogue dans la musique populaire britannique d’alors étaient la vielle à roue, la chalemie à deux hanches (ancêtre du hautbois), la corne crumhorn en forme de J, à deux hanches, et le tambourin. Sans oublier les tambours, le clairon, la flûte et le fifre utilisés par l’armée anglaise. Les instruments, les chansons populaires et le répertoire militaire britanniques sont arrivés aux Bahamas avec les colons, et une partie de leurs compositions a été transmise à des esclaves de maison. En dépit des interdictions, certaines musiques d’essence africaine ont aussi été tolérées par certains colons. Et lors de divers événements secrets, des musiques étaient jouées par des esclaves d’origines très diverses. Ils ont ainsi créé des musiques spécifiquement bahaméennes comme le junkanoo, mélangeant aux musiques britanniques des éléments de leurs propres cultures, recréant des instruments comme le balafon (xylophone) ou les maracas. L’utilisation du banjo, qui trouve des ancêtres dans plusieurs instruments d’Afrique de l’ouest comme le ngoni, se retrouve souvent dans le goombay en

plus de la guitare sèche et des percussions.

Junkanoo

Le rythme joué ici par la clave (deux morceaux de bois frappés l’un contre l’autre, appelés tibois aux Antilles françaises) sur cinq des morceaux de George Symonette, dont Goombay et Sponger Money, ou encore sur Spirit Rum, Bimini Gal, Coconut Water, Rum and Gin, Liza See Me Here, The Briland Rumba, Nassau Samba, Come to the Caribbean, At the Iron Bar, Digby, Noise in the Market se retrouve dans le mento jamaïcain, la biguine martiniquaise et guadeloupéenne, le son, la guaracha et le sucu sucu cubain. Identique au rythme de guitare qui a rendu Bo Diddley célèbre aux États-Unis, il trouve son origine dans les musiques d’Afrique de l’ouest, où il est répandu. Les mor ceaux cités plus haut sont en fait portés par une rythmique basée sur un rythme de percussions et tambours utilisé dans les défilés junkanoo du XXe siècle aux Bahamas. La tradition du junkanoo (ou jankunu et John Canoe) met en scène des mascarades représentant les oppresseurs (la reine, le roi, les maîtres, la police, etc.) et des chansons satiriques. Aux Bahamas ces masques trouvent sans doute leur origine dans les cérémonies masculines yoruba Egungun où les masques représentent les esprits des ancêtres qui prennent possession des corps pendant la cérémonie, chez les Edo (nord du Nigeria) et les initiations Poro chez les Sénoufo (Mali, Côte d’Ivoire, Burkina). On retrace l’origine du junkanoo aux Bahamas jusqu’au XVIIIe siècle. La musique de ces défilés était initialement interprétée avec des tambours “goombay” en peau de chèvre, des cloches de vache, des coquillages (dans lesquels on soufflait) et des sifflets. Les traditions des junkanoo dansants des rues sont restées après l’abolition. On les retrouve au Belize, en Jamaïque et dans d’autres îles de la région. Le junkanoo est une pérennisation des cérémonies et processions que les maîtres permettaient aux esclaves pendant les fêtes de noël, où avaient exceptionnellement lieu trois journées sans travail. Les 26 décembre à l’aube, des milliers de Bahaméens descendent ainsi Bay Street, au centre de Nassau. Le film Thunderball (Opération Tonnerre, 1965) de Terence Young avec Sean Connery dans le rôle de James Bond a été partiellement tourné aux Bahamas, à Nassau et Paradise Island. On peut y voir une séquence de poursuite au milieu d’un défilé de junkanoo particulièrement haut en couleurs, où l’on entend de nombreux tambours. Avec l’album “Religious Songs & Drums of the Bahamas” (Folk ways, 1953) c’est l’une des rares traces enregistrées du junkanoo bahaméen, qui avait été interdit de 1899 à 1954, causant la disparition d’une partie du patrimoine musical. Plusieurs rythmes ont ainsi été perdus en dépit des efforts récents de musicologues et musiciens.

Goombay

Les chansons traditionnelles des Bahamas, notamment des rondes pour enfants, comprennent parfois des rythmes 3/4 de valse (comme ici dans The Cigar Song). Le musicologue bien connu Alan Lomax3 a été le premier à préserver le patrimoine musical des Bahamas, capturant une partie d’un répertoire traditionnel très marqué par la musique britannique en enregistrant David Pryor a capella dès 1935. C’est en 1936 que Radio Bahamas ZNS-1 a commencé à émettre sur l’ensemble de l’archipel. L’histoire de la musique du pays est peu documentée, et ZNS ne diffusait pas beaucoup de musique locale. La fusion entre la chanson anglaise et l’héritage afro-américain a néanmoins produit une musique originale, bien à part : le goombay. Ce n’est qu’après la guerre que quelques enregistrements majeurs ont eu lieu, dont un florilège est réuni ici. Ils ont été en bonne partie réalisés par l’équipe de Art Records, un petit label basé à Miami qui apportait son matériel à Nassau pour les prises de son. Fondés par Harold Doane, les disques Art publieront d’abord les disques de Blind Blake, puis de George Symonette et Delbon Johnson, André Toussaint, Colin Kelly. À la tête d’une douzaine d’albums de “calypso”, Doane se tournera ensuite vers le rock de Floride en publiant d’abord quelques singles de rockabilly de Tommy Spurlin, puis Randy Spurlin et Kent Westberry. La musique populaire des Bahamas, le goombay, porte un nom emprunté à celui des tambours tra ditionnels. On peut écouter ces tambours sur Bahamian Brown Baby, Goombay, Goombay Rock, Bullfrog Dressed in Soldiers’ Clothes, Zombie Jamboree, Sponger Money ou Stone Cold Dead in the Market et les titres de George Symonette. Apparenté au calypso de la Trinité, le rythme de base du goombay ressemble à celui du junkanoo bahaméen et porte des chansons relatant des choses de la vie ou des événements inhabituels. Transmis de façon orale, le jeu de tambour goombay est improvisé dans un esprit proche du jazz, avec des phrasés, des rythmes complexes et des subtilités impossibles à relever sur partitions. Il a été incorporé à différents styles, comme le calypso, le jazz, la valse, les ballades et d’autres encore, et peut souvent être rapproché des pratiques du gwoka et lewoz gua deloupéen enregistré en 1963 par Velo (Coq la chanté), mais aussi du mento jamaïcain et même du nyabinghi (au rythme différent) jamaïcain de Count Ossie - sans oublier les tambours vaudou haïtiens et d’autres manifestations musicales afrocaribéennes. Le tambour goombay fait à l’origine partie d’un rite de purification. Dans le morceau Goombay, George Symonette chante que l’on danse autour du feu jusqu’à ce que “la fille s’enflamme” et qu’elle remue “jusqu’à ce que le diable sorte d’elle, comme le font les tambours” :

Goombay papas beat the drum again

Goombay mamas having fun again

Goombay’s a wicked dance when they do the goombay

Goombay, goombay du-de-da-da-da

Goombay, goombay du-de-da-da-da

Shake that devil out of you

Just like the goombays do

First you build a fire

Then it gets higher, higher and higher, higher and higher

Then they dance around it and they get wilder, wilder

and wilder

‘Til the girl burst in the fire

Goombay, goombay du-de-da-da-da

Shake that devil out of you

Just like the goombays do

En Jamaïque, les tambours carrés traditionnels des Marrons d’Accompong s’appellent les goombehs. Le délicieux mento jamaïcain des années 1950 est néanmoins bien distinct du goombay bahaméen. Bien que lui aussi anglophone, historiquement, géographiquement et musicalement proche du goombay - et bien qu’il ait lui aussi été étiqueté “calypso” à l’époque - il utilise des rythmes parfois différents.4 Le gumbé est aussi le nom d’une musique de danse jouée au son de gros tambours en Guinée Bissau. Plusieurs traditions africaines ont perduré dans la multitude des îles Bahamas. Elles ont contribué à l’élaboration du style et du répertoire goombay. Le groupe ethnique Akan, qui comprend les Ashantis, a apporté de la Côte d’Or des danses et musiques (tambours, percussions et voix) liées au culte traditionnel des esprits, que l’on retrouve sous une autre forme, sous le nom d’Orisha, chez les Yorubas. Malgré les peines encourues, les rites nécromanciens étaient répandus dans les années noires de l’esclavage. Ils étaient pratiqués par des guérisseurs utilisant des plantes et des techniques médicinales anciennes, proches de la nature. Ces cérémonies en musique sont liées à la pratique ou au rejet de l’obeah, considéré maléfique à la suite d’un amalgame avec la sorcellerie pratiqué par les missionnaires. En réalité, dans sa signification originelle l’obeah désignait jadis la puissance spirituelle venue d’Afrique. C’est le sens que ce mot a conservé au Suriname (ancienne Guyane néerlandaise), où le terme obia est utilisé avec une connotation positive par la grande communauté des Marrons, ces descendants d’esclaves évadés, qui n’ont donc pas connu le regard colonial. Interdit par les autorités bri tanniques, l’obeah mélange diverses cultures ouest-africaines, où les esprits des ancêtres prennent possession des vivants et s’expriment à travers eux pour prodiguer leurs avis et conseils lors de danses. Ces rites analogues (mais à l’origine et aux pratiques différentes) à ceux de la santeria cubaine, de l’obeah jamaïcain, du vaudou haïtien ou du hoodoo de la Louisiane sont ici évoqués avec humour dans Zombie Jamboree et Spirit Rum. Dans ce dernier, Blind Blake joue sur les mots avec l’homonyme “spirit”, qui désigne à la fois les spiritueux (le rhum est utilisé pour la purification), et “l’esprit”, un fantôme qui boit ici du rhum - ce qui lui fait peur et le fait fuir :

Oh Mama, yes I’d better run

Mama, spirit drinking rum

Not the spirit that’s in the rum

Mommy, the spirit I’m running from

Oh look a spirit drinking rum

Gonna get caught in the mid-day sun

You could stay but I gotta run

Want no part of that spirit rum

Oh look a spirit drinking rum [...]

Mama let’s get on the way

I just hear what the spirit say

He gonna drink till the break of day

Want to sing and he want to play [...]

Mama what an awful night

Mama say I gonna die with fright

Here is a ghost that’s a downright tyke [...]

Oh what an unnatural sight

Here is a ghost that’s a downright tyke

(NB : “Tyke” est une personne peu raffinée, mal élevée)

En raison de la très mauvaise réputation de l’obeah qui a perduré aux Caraïbes, rares sont ceux qui s’en réclament. On peut cependant découvrir deux remarquables albums consacrés à ce thème en 1970 par le chanteur bahaméen Exuma the Obeah Man. Exuma, alias McFarlane Gregory Anthony McKey, a emprunté son nom de scène à celui d’une île proche de Cat Island, où il est né.

Goombay 1951-1959

Après l’abolition de l’esclavage aux Bahamas en 1838, l’évangélisation des afro-bahaméens s’est répandue. Alors que les premiers colons étaient catholiques et protestants, la religion anglicane s’est propagée après l’indépendance des États-Unis en 1776. Ces religions européennes ont apporté leurs chants et musiques un peu guindées, mais le développement des églises protestantes, dont l’église baptiste et la Church of God, utilisent les claquements de pieds et de mains rythmés (parfois de façon sophistiquée, en rythme jusqu’à la double croche). Les participants utilisent aussi des instruments de musique quand c’est possible. Comme aux États-Unis, les spirituals et les cantiques chrétiens ont pris racine dans la musique afro-bahaméenne, puis le gospel à partir des années 1930. On peut d’ailleurs entendre un écho chrétien dans le récit déchirant d’un naufrage rapporté dans Run Come See Jerusalem (repris par Pete Seeger), où le capitaine George Brown invite ses passagers livrés à la mer à faire face à leur jugement. Des allusions au “Seigneur” sont aussi entendues dans Lord Got Tomatoes. Cet album montre différents aspects du goombey des Bahamas. Cependant il n’inclut pas le style rake ‘n’ scrape, presque identique au genre rip saw des proches îles Turks-et-Caicos (restée britanniques à l’indépendance des Bahamas en 1973). Le rake ‘n’ scrape est interprété avec un tam bour goombay, un concertina (sorte d’accordéon simplifié), et en frottant une scie de charpentier, qui produit un son rythmique aigu. Il rappelle différentes musiques ouest-africaines où des bâtons sont frottés l’un contre l’autre en rythme, et le washboard américain. Mais en ployant de façon irrégulière, la scie musicale produit en outre des harmonies particulières. Bien à part, il est traditionnellement utilisé pour accompagner les danses de toe polka, de heel et de quadrille bahaméen. Cette instrumentation particulière est plus répandue dans les îles de province (notamment Cat Island, réputée pour sa richesse musicale), alors que cette anthologie propose la musique urbaine, plus moderne et sophistiquée entendue et enregistrée à Nassau.

Disque 1 - Comme aux proches États-Unis, dans les années 1950 la guitare électrique se répandait largement aux Bahamas, et à Nassau en particulier. Le premier disque de cette anthologie réunit des titres où les instruments électriques ne sont pas utilisés - ou à de rares exceptions (la guitare électrique est plus présente sur le disque 2). Il permet donc de se faire une idée de ce à quoi ressemblait sans doute la musique populaire bahaméenne de Nassau dans les années 1940, voire 1930, où des artistes comme Blind Blake, que l’on peut écouter ici en version acoustique, étaient déjà actifs. Ce premier volet réunit trois des artistes majeurs du goombay de Nassau : Blind Blake, George Symonette et Charlie Adamson.

Disque 2 - Le charme de l’âge d’or du goombay commencera à décliner après les années soixante sous l’afflux d’influences diverses des pays alentour, diffusées par la radio : soca, reggae, salsa, rock, disco, etc. Mais dès les années 1950, on pouvait entendre une fusion du goombay avec les musiques populaires de l’époque. Le deuxième disque de cette anthologie commence par une sélection détaillant ces influences étrangères à la petite ville de Nassau. D’abord le rhythm and blues avec l’exquis Bullfrog Dressed in Soldier’s Clothes (“la grenouille taureau habillée en soldat”) et Goombay Rock, sorti en 1952. Blind Blake y chante qu’une fille des îles l’initie à l’irrésistible “gombay rock” - où l’on entend un solo de trompette bouchée rappelant Miles Davis période cool. Plusieurs stations de radio situées dans la proche Floride diffusaient des program mes où l’on pouvait entendre toute la diversité américaine : blues, jazz, rock & roll, jump blues, country & western, variété, etc. Avec ses solos de saxophone, la présence du jazz est particulièrement sensible sur Little Nassau, avec une guitare sortie tout droit d’un rockabilly; Ensuite, bien que profondément goombay, Nassau Nights ressemble à des enregistrements de mento jazz jamaïcain; quant à Sly Mongoose, c’est une composition de mento enregistrée dès 1925 par le sépharade trinidadien Sam Manning - et dix ans plus tôt par Lionel Belasco, lui aussi un sépharade trinidadien. C’est ensuite Nassau Samba, un goombay qui ne doit au Brésil que son titre, et cite différents styles des Caraïbes; en revanche le Nassau Merengue d’André Toussaint est nettement influencé par le merengue de Saint-Domingue tout proche. Mélange revigorant de goombay et de mambo cubain, Come to the Caribbean montre bien que le bouclier des îles d’Amérique Centrale est soudé par d’incessants échanges culturels, comme une sorte de fédération afro-américaine, un axe musical caribéen du Mississipi à la Guyane, et jusqu’au Brésil. Avec son influence cubaine, Noise in the Market accentue encore cette impression, tandis que Pretty Boy, partiellement chanté en français par André Toussaint (un nom vraisemblablement haïtien) complète le tour d’horizon des Caraïbes. Evoquant plus encore le mento jamaïcain, voire le reggae, Nassau Calling indique que les Bahamas sont en fait bel et bien un chaudron où tous ces ingrédients fusionnent, et ce sans doute plus encore qu’ailleurs. Une vocation cosmopolite pan-caribéenne confirmée par La Cruz, une composition de merengue avec guitare électrique latine, chantée en espagnol - par le francophone André Toussaint… et un Bahamia Brown Baby où les tambours jouent un rythme que l’on entend aussi dans la salsa du Porto-Ricain Eddie Palmieri. Suivent quelques goombays plus “purs”, et un Coconut Woman sur un rythme de samba brésilienne… le tout souvent présenté à l’époque sous l’étiquette “calypso” à la mode - qui signifiait en réalité la musique de Trinité-et-Tobago.

BLIND BLAKE AND THE ROYAL VICTORIA HOTEL CALYPSO ORCHESTRA.

Né à Matthew Town sur l’île d’Inagua aux Bahamas, doué d’une voix immédiatement reconnaissable, le chansonnier “Blind” Blake Higgs (1915-1985) est sans doute le meilleur interprète et compositeur bahaméen (à ne pas confondre avec le guitariste virtuose Arthur “Blind” Blake, “King of Ragtime Guitar” originaire de la Floride toute proche). Selon un de ses amis d’enfance, c’est à force de regarder le soleil qu’il serait devenu aveugle à l’âge de seize ans. Né de parents guitaristes, il jouait très jeune sur une guitare jouet (un bâton sur lequel est fixée une corde) puis maîtrisa le ukulele, la guitare, le piano et divers instruments à cordes avant d’adopter le banjo. Blind Blake joue d’abord dans les rues du quartier Over the Hill à Nassau, où il fait la manche, avant d’être invité à se produire à l’hôtel Imperial par son propriétaire - malgré la présence du groupe maison qui n’apprécie pas la concurrence d’un Noir. Il reprend Duck’s Yas Yas Yas (appelé ici Yes! Yes! Yes!), un succès de 1929 du pianiste de blues James “Stump” Johnson repris avec succès par Oliver Cobb la même année. Cette chanson de style hokum ou dirty blues festive, très osée pour l’époque, toute en métaphores sur les pratiques sexuelles, était populaire dans les bordels de St. Louis : “secouez vos épaules, secouez-les vite, et si vous ne pouvez pas secouer vos épaules, secouez votre yas yas yas” (cul). Les États-Uniens King Perry & his Pied Pipers en enregistreront une version mémorable en 1950 ; John Lee Hooker en fera son Bottle Up and Go. Marqué par le blues et le style mélodique de James “Stump” Johnson, le succès de Blind Blake vient rapidement. Il est engagé en 1933 au somptueux hôtel Royal Victoria de Nassau où pendant trente ans, accompagné par quatre autres musiciens (et finalement rejoint par un trompettiste) il sera l’attraction maison sous le nom de Blind Blake and his Royal Victoria Hotel Calypso Orchestra. Ses premières diffusions à la radio établirent sa notoriété en 1935. À cette époque la saison touristique d’hiver ne durait encore que quatre mois, et sa vie de musicien aveugle itinérant fut difficile. Il parvint à trouver des engagements privés hors saison, mais eut beaucoup de mal à s’imposer dans les boîtes de Nassau en raison de la ségrégation raciale. Ses compositions brillent pourtant. C’est en collaboration avec son guitariste et parolier Dudley Stanley Butter que naquirent des morceaux comme J.P. Morgan. Love, Love Alone5, une composition du Trinidadien Lord Caresser relatant l’abdication du roi Edward VIII (qui renonça officiellement au trône par amour, préférant en 1936 la main de Wallis Simpson à la couronne d’Angleterre - mais fut en réalité écarté du pouvoir parce qu’il était trop proche des nazis) participera à la légende de Blind Blake. Il lui sera interdit de chanter ce morceau à Edward VIII lors de sa visite à la colonie. Il fallut donc que l’ex-roi Edward lui demande expressément de l’interpréter, et que Blind Blake reçoive un tonnerre d’applaudissements pour que cette anecdote assoie définitivement sa réputation à Nassau. Il se produira au Dirty Dick’s, à la Blackbeard’s Tavern, St. Mary’s Schoolroom, the Orthodox Hall, et à l’Archer Club sur East Street. Il vécut d’abord de pourboires et grave son premier 78 tours, Those Good Ol’ Asta Boys/My Name Is Asta (Art 45-500) pour les disques Art en 1950 ou 1951. Il enregistre ensuite cinq albums publiés par Art entre 1951 et 1957. Blake Alphonso Higgs a écrit de grands classiques de la chanson bahaméenne, dont une partie est incluse ici. Ses créations ont aussi été reprises par d’autres artistes bahaméens, comme ici Pretty Boy par George Symonette. Il aura fallu soixante ans pour que des morceaux de Blind Blake aussi significatifs que Moonlight in Nassau, Uncle Joe, Goombay Rock, Spirit Rum et At the Iron Bar (avec ses quelques mots de français : “rendez-vous” et “vive la vie”) soient enfin réédités ici. Il est tentant de penser que Blind Blake mérite sa place au Panthéon des meilleurs artistes américains. Il est à déplorer que même quand ils sont anglophones - et a fortiori s’ils sont noirs - lorsque les musiciens ne sont pas de nationalité états-unienne leur oeuvre n’est pas souvent retenue dans une historiographie musicale souvent rédigée par des Etats-Uniens. Comme Lord Kitchener à la Trinité ou Count Lasher en Jamaïque, Blind Blake n’en reste pas moins un artiste dont le talent et la singularité devraient lui valoir une place de choix dans l’histoire de la musique américaine. Espérons que cet album contribuera à lui rendre justice. Duke Ellington, Mahalia Jackson et Louis Armstrong saluèrent son style et son originalité, et il fut invité à jouer pour le président John F. Kennedy et le Premier Ministre Harold McMillan. À la fin de sa vie, Blake fut employé à l’aéroport de Nassau, où il chantait pour accueillir les touristes - des passants indifférents le toisant sur la piste. “Blind” Blake Alphonso Higgs est décédé en 1985. Dans J.P. Morgan il met en scène une concubine trop gourmande qui, au restaurant, commande trop de plats. Il la prévient qu’il ne pourra pas payer un tel repas et lui suggère d’oublier son appétit pour le Champagne car tout ce qu’elle aura, c’est de la bière. Il enchaîne ensuite un refrain où il explique qu’il s’appelle bien Morgan, mais Willy et non J.P. - comme la banque J.P. Morgan.

My name is Morgan but it ain’t J.P.

There is no bank on Wall Street that belong to me

Forget your Champagne appetite

For the best you’ll get is beer tonight

My name is Morgan but it ain’t J.P.

Bill Morgan married Lizzy

Was thinking that gal would change her ways

But what she did to William’s face

Why, I’m most ashamed to say

For whenever she goes shopping

She will buy everything she see

And what she could not pay for

Then she would send home C.O.D.

One day six big delivery wagons came in back to old

Bill’s door

And they ask him to accept the goods whilst they went

back for more

But it didn’t take William long ago and get his hat

and coat

When Lizzy came back home that night

Then she had met a little note

So the note said

My name is Morgan but it ain’t J.P.

You must be think I own some railroad company

He said you might have known me pretty long

But you got my initial wrong

My name is Morgan but it ain’t J.P.

Run Come See Jerusalem rappelle le drame du Pretoria, coulé par l’ouragan Andros qui frappa l’île Andros près de Nassau le 28 septembre 1929, causant 48 morts aux Bahamas. Cette chanson est attribuée à Blake Higgs, mais un certain John Roberts a revendiqué l’avoir écrite en octobre 1929. Elle a été enregistrée par Gordon Bok, The Brothers Four, et par Pete Seeger & Arlo Guthrie pour l’album Precious Friends. Peas and Rice est une chanson de marins traditionnelle bien connue dans l’archipel, qui raconte que les Bahaméens préfèrent l’alcool aux fayots ! Little Nassau, sans doute une composition traditionnelle, est un encouragement à visiter Nassau typique des chansons des îles que l’on retrouve dans toutes les Caraïbes. Même thème sur Moonlight in Nassau et On a Tropical Isle. The Cigar Song énumère des îles des Bahamas (Briland, Long Island, puis c’est Havana, Miami, New York, et Nassau) auxquelles Blind Blake associe des boissons et les cigares de différentes tailles qu’il y a fumé - le plus petit étant à Nassau.

GEORGE SYMONETTE

Né en 1913, son père le révérend Alfred Carlington Symonette était originaire de l’île Acklins au sud de l’archipel. George Symonette débuta comme organiste à l’église baptiste St. James près de Kemp Road à Nassau. Il fit des études de pharmacien et travailla au Bahamas General Hospital (devenu Princess Margaret Hospital) avant d’ouvrir sa propre pharmacie sur Kemp Road. Sportif passionné, cultivé et affable, George Symonette mesurait deux mètres. Marqué par la musique d’église, il devint pianiste et chanteur. Accompagné par le percussioniste de goombay Berkeley “Peanuts” Taylor, il interprète le répertoire local au Waterside Club de Nassau. En 1933, quand Blind Blake est engagé à l’hôtel Royal Victoria, c’est George Symonette qui le remplace avec succès à l‘hôtel Imperial d’Alexander Maillis. Il adapte les phrasés de guitare de la région au piano, crée un style rythmique personnel et devient peu à peu la vedette locale, le “King of Goombay”. Symonette est bientôt engagé aux États-Unis, où il se produit régulièrement. Comme son trompettiste Lou Adams Sr., il y rejoindra même un temps les Chocolate Dandies, un groupe de jazz où l’on a pu entendre des musiciens célèbres comme le saxophoniste Benny Carter et le pianiste Teddy Wilson. Lou Adams dit de lui en 2004 “Il me rappelle Cab Calloway, un vrai hi-de-ho man”. L’influent George Symonette a enregistré deux albums de goombay pour Art Records, sur lesquels il a repris quelques compositions du new-yorkais Alice Simms (qui passait ses hivers à Nassau), Charles Lofthouse et Blind Blake.

CHARLIE ADAMSON

Né à Cat Island, réputée pour sa musique, et parfois comparé à Burl Ives, un débonnaire acteur américain interprète de chansons traditionnelles, Charlie Adamson a enregistré plusieurs albums au cours des années 1950 et 1960. Les quatre titres inclus ici ont été gravés sur son premier album pour Bahamian Rhythms en 1957. Chanteur de charme sympathique, toujours de bonne humeur, simple et sincère, il est fortement influencé par la musique calypso de la Trinité, une autre colonie britannique des Caraïbes. Son style doux et mélodieux reflète sa gentillesse et son tempérament détendu. Guitariste gaucher, il jouait le goombay sur une guitare dont les cordes étaient montées pour les droitiers (donc avec corde grave en bas), ce qui implique de jouer les accords à l’envers (comme le faisait aussi le guitariste de blues Albert King), mais il était aussi capable de jouer de cette même guitare comme un droitier. Il frappait souvent le tablier de son instrument pour marquer le rythme, à l’espagnole. Souvent invité à chanter en direct à la radio, il travaillait dans une station service d’essence sur Blue Hill Road à Nassau, et a beaucoup marqué le goombay par ses compositions et ses interprétations senties. Sa chanson Is It That You Really Love Me est en réalité une composition du trinidadien Lord Kitchener, dont la version est sortie sous le titre Kitch, Take It Easy. Quant à Bangaley, c’est une composition sur l’infidélité qui doit sans doute lui être attribuée. Eatin’ Too Much Emily, sur le même thème que J.P. Morgan de Blind Blake, est bien une de ses compositions, tout comme Dance the Goombay, archétype du style de Nassau influencé par les rythmes des défilés de junkanoo.

ELOISE LEWIS

Née en 1935 à Jacksonville en Floride et très tôt passionnée par la musique, Eloise Lewis a appris la guitare de son frère Freddie. Elle a commencé sa carrière de chanteuse à l’âge de douze ans et a remporté plusieurs concours d’amateurs, dont certains au Cinema Theatre de Nassau dans les années 1940 et 50. Elle parvient à s’imposer dans un monde de la musique totalement composé d’hommes et devient rapidement une professionnelle de renom grâce à son talent formidable de chanteuse, et à son jeu de guitare (et de basse !). Elle s’associe avec le percussionniste de gombay Berkeley “Peanuts” Taylor, bien connu des scènes de Nassau. Son premier album, Chi Chi Merengue, lui vaut une tournée aux États-Unis à la fin des années 1950. Femme décidée, exclusive, entourée de peu d’amis triés sur le volet, passionnée par la musique elle reviendra aux Bahamas dans les années 1960, et jouera régulièrement à la taverne Blackbeard’s sur Bay Street, à l’hôtel Montague Beach et à l’hôtel Emerald Beach sur West Bay Street. Eloise Lewis disparaîtra de la scène en 1964 avant de faire son retour avec Peanuts Taylor au Drumbeat Club en 1967. Elle fera connaître son style de goombay sur les scènes d’Europe, du Mexique, des États-Unis, jusqu’au Japon. À la fin de sa vie, Eloise Lewis s’installera à Freeport sur l’île de Grand Bahama, où elle décèdera en 1984 à l’âge de 49 ans. On peut écouter ici un titre à l’accompagnement de type cubain, mais à la mélodie distinctement rhythm and blues.

THE PERCENTIE BROTHERS

Les Percentie Brothers, nés et basés dans la petite ville tranquille de Dunmore Town sur Harbour Island (dans l’archipel Out Islands près de la grande île Eleuthera). Harbour fut la première capitale des Bahamas, où des pirates avaient établi une base détruite pas l’armée britannique, qui se fixa ensuite à Nassau. Les trois frères Herman, Victor et Humphrey ont été formés à la musique (chant, banjo et guitares) par leur père fermier et musicien autodidacte “Papa” Percentie (1889-1963). Papa était pasteur à temps partiel de la Church of God. Il composa le gospel Heaven Is So High et transmit son art à son fils aîné Herman, dont le fils Newton rejoint aussi le groupe, jouant sur une basse à une corde faite d’un manche à balai et d’une bassine retournée. La famille enregistra trois albums en 1953, Harbour Island Sings, Songs in Calypso (dont sont extraits les titres acoustiques, proches des racines, inclus ici : Liza See Me Here, Bimini Gal et The Briland Rumba) et Songs in Goombay. Au XXIe siècle, quatre générations plus tard la famille Percentie continue à pratiquer la musique, participant à différents événements de renouveau du goombay dans leur île Harbour, où fleurissent nombre d’autres groupes jouant dans des styles électriques plus récents.

FREDDIE MUNNINGS

Freddie Munnings représente l’incarnation bahaméenne de la tradition des orchestres afro-cubains des années 1930-1950. Originaire de Pure Gold sur la plus grande île du pays, Andros, Munnings perdit son père dans l’ouragan qui dévasta les Bahamas en 1926, et décida peu après de prendre le bateau pour la capitale, Nassau. De grande taille, doué d’une forte personnalité, il fut l’un des principaux acteurs de la scène de Nassau. Il commença sa carrière à la trompette, puis maîtrisa le piano, la clarinette et le saxophone. Il se perfectionna lors d’un engagement à Zanzibar en Afrique de l’est, puis s’installa avec ses musiciens au Silver Slipper, un cabaret au bas de la colline de Nassau où règnait une ambiance familiale, amicale et bienveillante. Munnings y construit un solide orchestre et un grand répertoire, mais après des années de professionalisme il décida de partir étudier la musique au New England Conservatory de Boston. À son retour en 1955, il accomplit son projet de fonder un cabaret, le fameux Cat ‘n’ Fiddle night club, situé au-delà de la colline. Cette boîte devint vite la fierté de Nassau, engageant des célébrités comme Nat “King” Cole, Sammy Davis Jr., Paul Anka, Harry Belafonte, Perez Prado, Count Basie, et plus tard Ben E. King et Sam Cooke. Il y accueillit le premier ministre britannique Harold McMillan, le président américain John Kennedy et le pasteur Martin Luther King, qui se nouèrent d’amitié avec lui. Au coeur de la colonisation britannique où la mentalité créole dévalorisait les origines africaines, avec ses invités prestigieux le Silver Slipper contribua grandement à rendre aux afro-bahaméens une fierté de leur négritude. Freddie Munnings devint un homme très respecté qui, comme Harry Belafonte, s’engagea dans la lutte contre la discrimination raciale très répandue aux Bahamas à cette époque. Populaire, admiré, généreux, homme d’affaires accompli, symbole de réussite et de professionalisme, courtisé par les politiciens il fonda le syndicat des musiciens des Bahamas. Devenu un notable, il ne cessa pas ses activités de chef-d’orchestre. Le remarquable Freddie Munnings Orchestra employait d’excellents musi ciens qui pouvaient concurrencer haut la main les meilleures formations de l’époque, notamment de Cuba tout proche. La formation était marquée par les musiques cubaines à la mode dans les années 1950, comme on peut l’entendre sur l’influence mambo de Come to the Caribbean et Noise in the Market (chantés en anglais). L’influence des rythmes junkanoo des Bahamas est en revanche présente sur le goombay de Coconut Woman (qui sera enre gistré par Harry Belafonte) et Digby. L’orchestre avait plusieurs chanteurs, dont Harold McNair, qui publia plusieurs titres sous son propre nom, tel Bahama Brown Baby. Peu d’informations ont fait surface sur les autres artistes et musiciens figurant sur cet album. Comme beaucoup, le jeune Richie Delamore s’est fait connaître au bar Dirty Dick’s, et enregistra l’album Richie Delamore in Stereo en 1959 après une tournée aux Etats-Unis et au Canada; Vincent Martin & His Bahamians reprennent ici quatre compo sitions de Trinidad-et-Tobago : trois du célèbre calypsonien trinidadien Houdini, Stone Cold Dead in the Market, Coconut Water Rum & Gin et Uncle Joe, Gimme Mo’, ainsi que le classique trinidadien Zombie Jamboree (dont la version originale de Lord Intruder parut pour la première fois en 1953 en face B de Disaster with Police). Quant à Delbon Johnson, il publia en 1953 l’album Dirty Dick’s Famous Bar in Nassau Bahamas Presents Delbon Johnson’s Calypso Rhythms, où figurent plusieurs perles, dont ses propres compositions Bullfrog Dressed in Soldier’s Clothes, l’évocateur instrumental Nassau Nights, et Nassau Calling, qui lui est attribué. On peut également entendre ici sa version d’un traditionnel du mento jamaïcain, Sly Mongoose, un standard à Trinidad-et-Tobago depuis le début du XXe siècle, et le traditionnel bahaméen Little Nassau dont Blind Blake propose également un extrait dans son pot-pourri (CD 1, titre 16).

Bruno BLUM

© 2011 FREMEAUX & ASSOCIES

Remerciements à Fabrice Uriac et Kenneth Bilby.

1. Ecouter l’anthologie Trinidad - Calypso 1939-1959 (Frémeaux et Associés, à paraître fin 2011).

2. Ecouter Harry Belafonte, Calypso-Mento-Folk 1954-1957 (Frémeaux & Associés FA 5234).

3. Pour cette période antérieure à notre sélection, l’auditeur pourra se référer aux albums “Deep River of Song” et “Ring Games and Round Dances” (1934-1935), dans la série The Alan Lomax Collection, Rounder 2002.

4. Ecouter l’anthologie Jamaica-Mento 1951-1958 (Frémeaux et Associés FA 5275), qui contient notamment des versions jamaïcaines authentiques et méconnues de sept des titres repris et enregistrés par Harry Belafonte sur Calypso, dont une version antérieure du célèbre Day O jouée sur des tambours seuls.

5. Disponible sur le volume Calypso de la série Anthologie des Musiques de danse (à paraître chez Frémeaux et Associés, fin 2011).

english notes

The Bahamas

The seven hundred islands of The Bahamas have formed an independent, English-speaking part of the British Commonwealth since 1973. This archipelago lies at the limits of The Caribbean east of the Florida peninsula and facing the north-eastern shores of Cuba, with Bimini Island less than fifty miles from Miami. To the south, Inagua Island is little more than sixty miles from Haiti. The Bahamian capital Nassau is situated on New Providence Island, a home to hundreds of offshore companies including banks known for money-laundering specialities; banking is a high-profile activity of The Bahamas, where taxation is low, and the song J.P. Morgan here is an allusion to one such business-bank. Due to Miami’s proximity, the tourist industry has left a deep imprint on the country’s culture: holidaymakers indirectly provide most of the population’s income, and the country’s festive music logically draws an audience partly composed of tourists, most of them Americans. After the success of Trinidadian calypsos in the years 1940-501, the various English songstyles of The Caribbean were often labelled calypsos (although they were actually quite distinct from the genre born in Trinidad & Tobago) and the name of the Bahamian group “Blind Blake & His Royal Victorian Hotel Calypso Orchestra” is an example of the confusion. Blind Blake was probably the most important figure of goombay music, the real name of the popular music heard in The Bahamas post-war. In Digby, Freddie Munnings causes “calypso” to rhyme with “Nassau”, and the Nassau tavern known as Dirty Dick’s (named after an old pub in London, England), and which opened in 1922, also harks back to another famous Dirty Dick’s - a hot calypso spot in Trinidad. Finally, the success of the album Calypso (1956), recorded by New-Yorker of Jamaican descent Harry Belafonte, made this “calypso” qualification even more inevitable when it came to categorizing music from the Anglo-American Antilles islands2.

Goombay roots

The first American soil on which Christopher Columbus set foot in 1492 was the Bahamian island of San Salvador, an island populated — like Jamaica and Cuba — by Taino/Arawak “Indians” whose few musical traditions — like the areito dance, whose music features in Cuban archives — have endured on some remote islands. In less than a century, the native population was decimated by smallpox and the ill-treatment it received at the hands of Spanish colonists. The next inhabitants were a few rare Europeans, then the English invested The Bahamas at the end of the 18th century. The almost barren coral islands weren’t signi ficantly populated until the American War of Independence (1771-1776), when Britons loyal to the Crown of England fled there from the American continent, bringing with them many slaves of West-African origin. After the abolition of slavery (1838), other refugees, this time from the American South, came to The Bahamas with their slaves during the American Civil War (1861-1865). At the beginning of the 19th century, slaves were still banned from dancing and making music (and their masters were also punished if they condoned it). The English colonial authorities feared that music and dancing encouraged slaves to communicate and form secret organisations; any meeting between Africans was seen as a potential threat. The revolution in nearby Haiti (1801) caused those in favour of slavery to tremble, and their slaves were refused the rights to read, teach or preach. In the British Antilles islands, African religious rites were strictly forbidden in 1761, with death or exile as penalties. Traditional dances, drums and songs were reputedly used in obeah ceremonies, forms of religious ritual which the colonists considered as sorcery. In fact, obeah groups practised music as a derivative of spiritual/religious cults that originated notably among the Ashanti and Yoruba tribes; these secret, forbidden rituals were even picked up by Holly wood, and the myth of the zombie featured in screenplays such as George A. Romero’s Night of the Living Dead in 1968. Written and recorded in 1953 by Lord Intruder, a calypso performer from Tobago, Vincent Martin’s Zombie Jamboree here treats these legends with derision. Sometimes called Back to Back, this Caribbean classic was also recorded by California’s Kingston Trio, with several versions by Jamaicans including The Wrigglers, Lord Jellicoe, The Hiltonaires and Count Frank. African music had been prohibited since before 1838, yet the enforced status of Afro-Bahamians as workers did allow some of them to play European instruments that were available. English musicians were rare on the islands; and so domestic slaves often received an education in European music, with a view to enlivening their masters’ soirees, especially at Christmas. A talent for music was even considered as “added-value” when a slave was sold at a public

auction.

During this period, at the other end of the social scale, English aristocrats — men and women — had a duty to play some musical instrument, and they performed madrigals using a lute, dulcimer or harpsichord. The violin was popular with both nobles and plebeians, and so that instrument appeared on the islands too. Other instruments in vogue in English popular music at the time included the hurdy-gurdy, the shawm (a medieval, twin- reed-ancestor of the oboe), the J-shaped crumhorn (also with two reeds) and the tambourine, not to forget the drums, bugles, flutes and fifes of the English army. The instruments, popular songs (and military repertoire) of the English all arrived in The Bahamas with the colonists, and some of the compositions were handed over to domestic slaves. Despite the bans, some music with African roots was tolerated by certain colonists, and at various secret events music was played by slaves of widely-varying origin. They created specifically Bahamian music like the junkanoo, mingling English music with elements of their own cultures, and re-creating instruments like the balafon (xylophone) or maracas. The banjo, whose ancestors were various West-African instruments like the ngoni, was also frequently used in goombay music in addition to an acoustic guitar and percussion.

Junkanoo

The rhythm played here on claves (two pieces of wood struck together, called tibois in the French Caribbean) on five of the pieces by George Symonette, including Goombay and Sponger Money, but also on Spirit Rum, Bimini Gal, Coconut Water, Rum and Gin, Liza See Me Here, The Briland Rumba, Nassau Samba, Come to the Caribbean, At the Iron Bar, Digby and Noise in the Market, can also be found in mento in Jamaica, in the biguine of Martinique and Guadeloupe, as well as in the Cuban son, the guaracha and sucu-sucu. Identical to the guitar-rhythm that made Bo Diddley famous in The United States, this rhythm had its origins in the music of West Africa, where it was widespread. The pieces mentioned above are in fact sustained by a rhythm based on the drums and percussion still used in the junkanoo street-parades of The Bahamas in the 20th century. The main feature of the junkanoo (or jankunu or John Canoe) tradition is a masquerade representing the oppressor (Queen, King, master, police, etc.), where satirical songs are staged. In The Bahamas, these masques probably originated with the Egungun rituals conducted by (male) Yorubas, in which ancestral spirits took possession of their bodies during the ceremony; this was practised among the Edo population of northern Nigeria, and also in the Poro initiation-rites of Senufo tribes in Mali, Ivory Coast and Burkina. The origins of the junkanoo in The Bahamas can be traced back to the 18th century, and the music in these parades was initially performed using goatskin “goombay” drums, cow-bells, conch shells (used as wind-instruments), and whistles. The street-dancing junkanoo traditions remained after the abolition of slavery. They can be found in Belize, in Jamaica, and also on other islands in the region. The junkanoo perpetuates ceremonies and processions in which slaves took part, with their masters’ permission, during the Christmas season when, exceptionally, slaves had a three-day respite from their duties. At dawn every 26th of December, thousands of Bahamians parade down Bay Street in the centre of Nassau, and Terence Young’s film Thunderball (1965) includes scenes where James Bond, played by Sean Connery, can be seen in Nassau and Paradise Island: one scene in particular was filmed during a highly-colourful junkanoo parade filled with the sounds of the drums. Along with the album “Religious Songs & Drums of the Bahamas” (Folkways, 1953) it is one of the rare traces on record of the Bahamian junkanoo, which was prohibited from 1899 to 1954, a ban which caused part of the islands’ musical heritage to disappear: several rhythms were lost despite the recent efforts of musicologists and musicians to try and recover them.

Goombay

The traditional songs of The Bahamas, especially children’s dances, sometimes include 3/4 waltzrhythms (cf. The Cigar Song here). The well- known musicologist Alan Lomax3 was the first to preserve the music-heritage of The Bahamas by recording some of the traditional repertoire — deeply marked by British musical influences — which was performed a capella as early as 1935 by David Pryor. Bahamas Radio ZNS-1 began broadcasting across the whole archipelago in 1936, but there was little documentation of the country’s musi cal history, and ZNS also had little coverage of local music. The fusion of English song with The Bahamas’ Afro-American heritage did, however, produce original music that was quite apart: goombay music. Major recordings didn’t take place until after the War, and an anthology of those appears here. For the most part they were recorded by a team from Art Records — a small Miami-based company — who brought their own sound-recorders to Nassau. Art Records-founder Harold Doane would publish records by Blind Blake and, later, others by George Symonette, Delbon Johnson, André Toussaint and Colin Kelly. After a dozen “calypso” albums, Harold Doane then turned to rock music in Florida, releasing a few rockabilly singles by Tommy Spurlin, and then Randy Spurlin and Kent Westberry. Goombay, the popular music of The Bahamas, takes its name from traditional drums. You can listen to these on Bahamian Brown Baby, Goombay, Goombay Rock, Bullfrog Dressed in Soldiers’ Clothes, Zombie Jamboree, Sponger Money or Stone Cold Dead in the Market, and also on the George Symonette tunes. Related to the calypso of Trinidad, the basic goombay rhythm resembles Bahamian junkanoo, and it carries songs that tell everyday stories or exceptional events. Handed down from one generation to the next, goombay drumming is improvised, as in jazz, with phrasing, complex rhythms and other subtleties impossible to write down on music-paper. It has been incorp orated into different styles of music such as the calypso, jazz, waltzes, ballads and others, and can often be likened to the gwoka and lewoz (common in Guadeloupe, and recorded in 1963 by Velo with Coq la chanté), but it also resembles Jamaica’s mento, and even the Jamaican nyabinghi (a diffe rent rhythm) of Count Ossie, not forgetting the voodoo drums of Haiti and other Afro-Caribbean music-traditions. The goombay drum originally belonged to a purification ritual. In the title Goombay, George Symonette sings of dancing around a fire until “the girl burst in the fire”, shaking “that devil out... Just like the goombays do”:

Goombay papas beat the drum again

Goombay mamas having fun again

Goombay’s a wicked dance when they do the goombay

Goombay, goombay du-de-da-da-da

Goombay, goombay du-de-da-da-da

Shake that devil out of you

Just like the goombays do

First you build a fire

Then it gets higher, higher and higher, higher and

higher

Then they dance around it and they get wilder, wilder

and wilder

‘Til the girl burst in the fire

Goombay, goombay du-de-da-da-da

Shake that devil out of you

Just like the goombays do

In Jamaica the traditional square drums of the annual Maroon Festival in Accompong are called goombehs. Yet the delicious Jamaican mento of the Fifties is quite distinct from the Bahamian goombay; Englishspeaking and traditionally close — historically, geographically and musically — to the goombay, and despite the fact that it, too, was once labelled “calypso”, mento makes use of rhythms that are sometimes different4. The gumbé is also the name given to some of the dance-music accompanied by the large drums of Guinea-Bissau. Several African traditions have been perpetuated in a myriad of Bahamian islands, and they have contributed to elaborating the goombay style and its repertoire. The Akan ethnic group, which includes Ashantis, brought dances and music from the Gold Coast region (drums, percussion and singing) that were linked to the traditional spirit culture which can be found in another form — called Orisha — among Yorubas. Despite the penalties involved, necromancy rites were widespread in the dark years of slavery; they were practised by healers who used plants and ancient medicinal techniques close to nature. These musical ceremonies were tied to the practice — or reject — of Obeah, considered evil folk magic as a result of its being amalgamated with sorcery by missionaries. In fact, obeah originally meant the spiritual power that came from Africa. This is the meaning that the word has retained in Surinam, formerly Dutch Guyana, where the term obia has positive connotations among the large Maroon community; as descendants of runaway slaves, they never suffered the gaze of colonials. Prohibited by British authority, obeah is a mixture of various West-African cultures where ancestral spirits were said to take possession of the bodies of the living, and express themselves through their “hosts”, proffering advice and counsel during dances. These rituals — similar to those of the Cuban santeria, Jamaican obeah, Haitian voodoo or the hoodoo rites of Louisiana (although these had different origins and practises) — are evoked here with humour in Zombie Jamboree and Spirit Rum. In the latter, Blind Blake plays word-games with “spirit”, meaning the rum used for purification, and its homonym, “spirit”, or ghost, who drank the rum only to run away in fear:

Oh Mama, yes I’d better run

Mama, spirit drinking rum

Not the spirit that’s in the rum

Mommy, the spirit I’m running from

Oh look a spirit drinking rum

Gonna get caught in the mid-day sun

You could stay but I gotta run

Want no part of that spirit rum

Oh look a spirit drinking rum [...]

Mama let’s get on the way

I just hear what the spirit say

He gonna drink till the break of day

Want to sing and he want to play [...]

Mama what an awful night

Mama say I gonna die with fright

Here is a ghost that’s a downright tyke [...]

Oh what an unnatural sight

Here is a ghost that’s a downright tyke

Due to the unhealthy reputation of obeah perpetuated throughout the Caribbean, few people claimed to be its followers, but two remarkable albums devoted to it were recorded in 1970 by Bahamian singer Exuma The Obeah Man, alias McFarlane Gregory Anthony McKey, who borrowed his pseudonym from the isle close to Cat Island where he was born.

Goombay 1951-1959

After slavery was abolished in The Bahamas in 1838, the evangelization of Afro-Bahamians became widespread. Whereas the first colonists were Catholics and Protestants, the Anglican religion took hold after the American Declaration of Inde pendence in 1776. These European faiths brought songs and music that were a little stilted, but with the development of Protestantism, inclu ding the Baptist Church and the Church of God, came foot-tapping, hand-clapping rhythms that were sometimes sophisticated down to the semiquaver. Participants also used musical instruments whenever possible. As in The United States, spiri tuals and Christian hymns took root in Afro-Bahamian music, and then in gospel from the Thirties onwards. A Christian echo of this can be heard in the heartbreaking tale of a shipwreck told in the song Run Come See Jerusalem (picked up by Pete Seeger), where the ship’s captain George Brown invites his passengers, given up to the seas, to face their Judgement Day. Allusions to “The Lord” can also be found in Lord Got Toma toes. This album shows various aspects of goombay in The Bahamas, but excludes the rake ‘n’ scrape style, almost identical to the rip saw genre found in the nearby Turks and Caicos Islands (which remained British after The Bahamas became independent in 1973). Rake ‘n’ scrape is played with a goombay drum, a concertina (a kind of simplified accordion), and a rubbed carpentry-saw, which produces a highpitched, rhythmical sound. It is reminiscent of music from parts of West Africa, where sticks are rubbed against each other in rhythm, and also the American washboard. The musical saw, however, depending on how you bend it, can also produce special harmonies. An instrument apart, it is traditionally used to accompany Bahamian toe polka and heel dances, or the quadrille. This instrumentation is more widespread in the outlying islands (especially on Cat Island, reputed for its musical diversity), while this anthology is devoted to the urban sounds (more modern and sophisticated music), heard and recorded in Nassau. Disc 1: As was the case in the nearby United States, the electric guitar spread widely across The Bahamas in the 1950s and took a special hold in Nassau. The first disc in this anthology, however, features titles where the amplified instrument wasn’t used at all, or else only rarely (the electric guitar is more prominent in Disc 2). So this first CD gives listeners an idea of the (probable) sound of popular music in The Bahamas during the Forties (even the Thirties), when artists like Blind Blake — whose acoustic versions are a feature here — were already quite active. So this first chapter presents three major goombay artists from Nassau: Blind Blake, George Symonette and Charlie Adamson.

Disc 2: The charm of goombay’s Golden Age began to decline after the Sixties, overtaken by various trends from surrounding countries which gradually received more exposure over the airwaves: soca, reggae, salsa, rock, disco, etc. The dawn of the Fifties, however, saw a fusion of goombay with the popular music of the period, and this second disc begins with a selection showing influences that were foreign to Nassau, such as the sound of rhythm and blues, with the exquisite Bullfrog Dressed in Soldier’s Clothes and Goombay Rock, released in 1952. Blind Blake sings about the island girl who initiated him to the irresistible sounds of “goombay rock”, and the song’s muted-trumpet solo reminds you of a “cool”-period Miles Davis. Several stations in nearby Florida aired programmes where listeners could hear all of America’s diversity: blues, jazz, rock & roll, jump blues, country & western, pop, etc. The presence of jazz is well to the fore in Little Nassau, with its saxophone solos and a guitar straight out of rockabilly; next, although goombay to the core, Nassau Nights has a Jamaican mento-jazz feel; as for Sly Mongoose, this mento tune was recorded as early as 1925 by Sam Manning, a Sephardi from Trinidad (and also by Lionel Belasco ten years earlier, also a Trinidadian Sephardi.) Next comes Nassau Samba, a goombay tune (its only Brazilian connection is the title) which quotes different Caribbean styles; André Toussaint’s Nassau Merengue, on the other hand, is clearly influenced by the merengue of nearby Santo Domingo. Come to the Caribbean, an invigo rating mixture of goombay and Cuban mambo, shows that incessant cultural exchange shaped Central America’s protective shield of islands into a sort of Afro-American Federation, a Caribbean music-axis that stretched from the Mississippi to Guyana and beyond into Brazil. The Cuban influences present in Noise in the Market accentuate this impression even further, whilst Pretty Boy, sung partly in French by André Toussaint (in all likelihood a Haitian name), completes this tour of the Caribbean horizon. Nassau Calling is an even stronger evocation of Jamaican mento, or even reggae, and it shows that The Bahamas, probably more than anywhere else, were indeed a crucible where all these ingredients fused together - perhaps even more than elsewhere. This cosmopolitan, pan- Caribbean vocation is confirmed by La Cruz, a merengue composition with an electric Latin guitar and lyrics sung in Spanish... by the French-speaking André Toussaint; another confirmation is Bahamian Brown Baby, where the drums play a rhythm you can also hear in salsas by Puerto Rican Eddie Palmieri. A few “purer” goombays follow, together with a Coconut Woman whose rhythm is Brazilian samba. All of these tunes were collec tively described in their day — fashionably — as “calypsos”... the genre which was, of course, the prerogative of Trinidad & Tobago.

BLIND BLAKE AND THE ROYAL VICTORIA HOTEL CALYPSO ORCHESTRA

Born in Matthew Town on Inagua Island, and gifted with a voice that is unmistakeable, the songster “Blind” Blake Higgs (1915-1985) was no doubt the best composer/performer ever produced by The Bahamas (not to be confused with the guitar virtuoso Arthur “Blind” Blake, the “King of Ragtime Guitar” from nearby Florida). According to a childhood friend, Higgs went blind at sixteen from staring at the sun. His parents were guitarists and he played as a child on a toy guitar (a stick with a string attached) before he later mastered the ukulele, guitar, piano (and various other stringed instruments) and finally adopted the banjo. At first, Blind Blake played for tips in the streets of Nassau’s Over The Hill district, but his life changed when the owner of the Imperial Hotel invited him to perform there — despite the presence of a house band who didn’t take kindly to the competition of a Black youngster. Here Blind Blake does his own version of Duck’s Yas Yas Yas (under the title Yes! Yes! Yes!), a hit in 1929 for blues pianist James “Stump” Johnson (also covered that same year by Oliver Cobb). The song, in the festive hokum or dirty blues style, was extremely daring for the period — filled with sexual innuendo and metaphors — and its “Shake your shoulders, shake ‘em fast... if you can’t shake your shoulders, shake your yas yas yas” lyric was very popular in the cathouses of New Orleans. Americans King Perry & his Pied Pipers would record a memorable version of it in 1950; John Lee Hooker turned it into Bottle Up and Go. Blind Blake, marked by the blues and trademar k-melodies of “Stump” Johnson, was a rapid success: in 1933 he was hired by the sumptuous Royal Victoria Hotel in Nassau where for thirty years, accompanied by four other musicians (later rejoined by a trumpeter), he was the main house attraction, appearing as “Blind Blake and his Royal Victoria Hotel Calypso Orchestra”. His first radio broadcasts in 1935 sealed his popularity. In those days, however, with the winter tourist-season lasting only four months, life as an itinerant (and blind) musician was arduous during the off-season; he managed to find other bookings, but had trouble working in the Nassau clubs due to racial segre gation. Yet his compositions were brilliant: working with guitarist/lyricist Dudley Stanley Butter, the pair gave birth to pieces like J.P. Morgan. The Blind Blake legend was enhanced by Love, Love Alone5, a composition by Lord Caresser from Trinidad which related the abdication of King Edward VIII: he renounced his throne in 1936, preferring the hand of Mrs. Wallis Simpson to the Crown of England (although it seems he was in reality too close to the Nazis to remain King...). Blind Blake was forbidden to sing the song during Edward’s visit to the colony, and so the ex-King had to make a special request to hear it: the song definitively sealed Blake’s reputation in Nassau, and he appeared at Dirty Dick’s, Blackbeard’s Tavern, St. Mary’s Schoolroom, the Orthodox Hall, and at the Archer Club on East Street. Blake cut his first 78rpm record, Those Good Ol’ Asta Boys/My Name Is Asta for Art Records (Art 45-500) in 1950 or 1951, and went on to make five albums released by Art between 1951 and 1957. Blake Alphonso Higgs wrote several great Bahamian classics and some of them are included here. His creations were also covered by other Bahamian artists (cf. George Symonette with Pretty Boy). It has taken sixty years for such important Blind Blake titles as Moonlight in Nassau, Uncle Joe, Goombay Rock, Spirit Rum and At the Iron Bar (with its occasional French references, “rendezvous” or “vive la vie”) to be finally reissued here. It’s tempting to think that Blake deserves a place in the American artists’ Hall Of Fame; it’s also deplorable that non- American nationals and their works, even when the former speak English – and especially when they’re Black — hardly ever receive a mention in musichistories drafted by Americans... Even so, like Lord Kitchener in Trinidad or Count Lasher in Jamaica, Blind Blake remains an artist whose talent and singularity were more than enough to earn him a place in American music-history. Let’s hope that this album will contribute to repay that debt: Duke Ellington, Mahalia Jackson and Louis Armstrong all saluted his style and originality, and he played in front of both President John F. Kennedy and British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan. At the end of his life, Blake was employed at Nassau Airport where he sang to welcome tourists — who were all quite indifferent to his presence on the tarmac. “Blind” Blake Alphonso Higgs died in 1985. The subject of the song J.P. Morgan is a spendthrift concubine who thinks her man will always pick up the bill; a ruinous situation that leads him to remind her that:

My name is Morgan but it ain’t J.P.

There is no bank on Wall Street that belong to me

Forget your Champagne appetite

For the best you’ll get is beer tonight

My name is Morgan but it ain’t J.P.

Bill Morgan married Lizzy

Was thinking that gal would change her ways

But what she did to William’s face

Why, I’m most ashamed to say

For whenever she goes shopping

She will buy everything she see

And what she could not pay for

Then she would send home C.O.D.

One day six big delivery wagons

Came in back to old Bill’s door

And they ask him to accept the goods

Whilst they went back for more

But it didn’t take William long

To go and get his hat and coat

When Lizzy came back home that night

Then she hand me a little note

So the note said

My name is Morgan but it ain’t J.P.

You must be think I own some railroad company

He said you might have known me pretty long

But you got my initial wrong

My name is Morgan but it ain’t J.P.

Run Come See Jerusalem recalls the tragedy of the Pretoria, which sank off Andros Island near Nassau on September 28th 1929, with the loss of 48 pas sengers and crew. The song is attributed to Blake Higgs, but a certain John Roberts claimed to have written it in October 1929. It was also recorded by Gordon Bok, The Brothers Four, and by Pete Seeger & Arlo Guthrie for their album Precious Friends. Peas and Rice is a traditional sea-shanty famous throughout the archipelago for its line saying that Bahamians prefer alcohol to peas! Little Nassau, probably a traditional piece, is an exhortation to visit Nassau, a typical feature in many songs from islands throughout the Caribbean. The same theme appears in Moonlight in Nassau and On a Tropical Isle. The Cigar Song lists Bahamian islands (Briland, Long Island) and other places (Havana, Miami, New York, Nassau) which Blind Blake associates with drinks and different-sized cigars he’s smoked (the smallest being in Nassau).

GEORGE SYMONETTE

Symonette was born in 1913, and his father Reverend Alfred Carlington Symonette came from Acklins Island in the south of the archipelago. George began his career as an organist at St. James’ Baptist Church near Kemp Road, Nassau. He studied pharmacy and worked in Bahamas General Hospital (later Princess Margaret Hospital) before opening his own chemist’s shop on Kemp Road. A keen sports enthusiast, cultured and affable, George Symonette was 6’6 tall. Marked by church music, he became a pianist and singer and, accompanied by goombay drummer Berkeley “Peanuts” Taylor, he performed local songs at the Waterside Club in Nassau. When Blind Blake went to the Royal Victoria in 1933, George Symonette replaced him successfully at the Imperial, owned by Alexander Maillis. He adapted the guitar pieces of the region for the piano, creating a personal rhythmstyle that gradually earned him the local title of “King of Goombay”. Symonette was soon given his chance in The United States, and he appeared regularly there. Like his trumpeter Lou Adams Sr., he even joined The Chocolate Dandies for a time, a jazz group where such famous musicians as saxophonist Benny Carter and pianist Teddy Wilson could be heard. In 2004, Lou Adams said of Symonette, “He reminds me of Cab Calloway, a real hi-de-ho man”. The influential George Symonette recorded two goombay albums for Art Records on which he picked up a few comp ions by New York’s Alice Simms (who spent her winters in Nassau), Charles Lofthouse and Blind Blake.

CHARLIE ADAMSON

Adamson was born on Cat Island, an isle reputed for its music, and he was sometimes compared with Burl Ives, the debonair American actor/folksinger. Adamson was highly influenced by the calypsos of Trinidad, and he became a straightforward crooner whose good nature, simplicity and sincerity made him an extremely amiable personality. Charlie recorded several albums in the Fifties and Sixties, and the four titles included here are taken from his first album (1957) for Bahamian Rhythms; his soft, melodious style reflects the gentleness of his easy-going temperament. A left-handed guitarist, he played goombay on a guitar strung for a right- hander (with the bass-strings lowest), which naturally (for him) involved playing chords “the wrong way around”, like blues guitarist Albert King also did, but he was just as capable of playing the same guitar righthanded. Adamson used to slap the sound-board of his guitar, beating out the rhythm like a Spanish guitarist. He worked at a gas-station on Nassau’s Blue Hill Road, and was often invited to sing on the radio. His heartfelt songs and performances left a deep mark on goombay music. Is It That You Really Love Me isn’t an Adamson song (it was written by Trinidadian Lord Kitchener, who released it under the title Kitch, Take It Easy), but Bangaley, a song about infidelity, was probably composed by Charlie. Eatin’ Too Much Emily (on the same theme as Blind Blake’s J.P. Morgan), is indeed his own song, as is Dance the Goombay, an archetype of the Nassau style influenced by the rhythms of junkanoo street-parades.

ELOISE LEWIS