- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

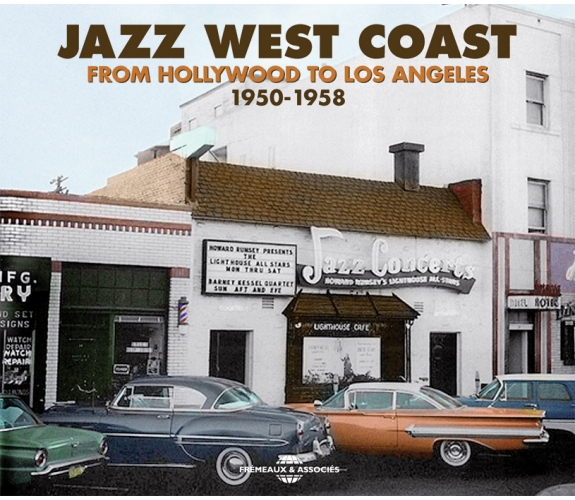

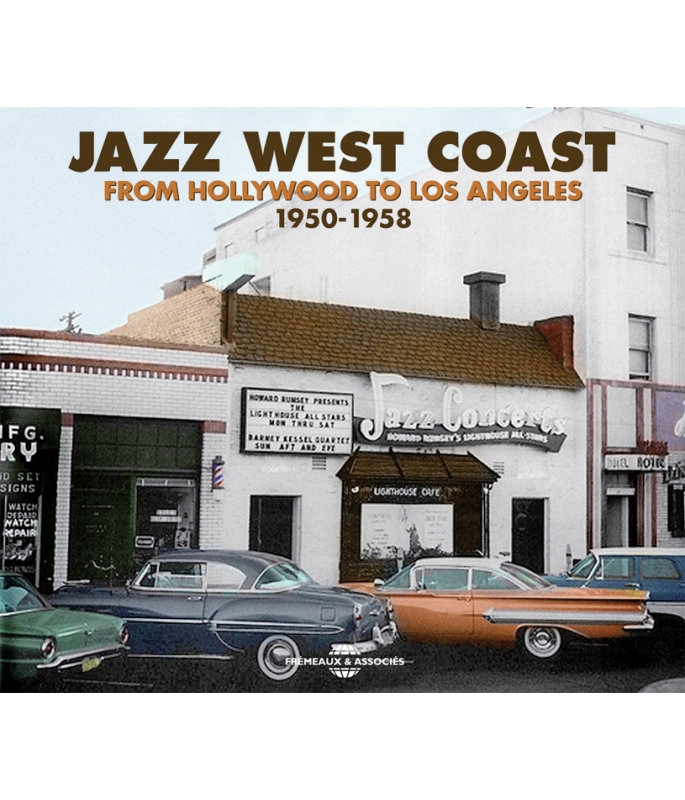

FROM HOLLYWOOD TO LOS ANGELES 1950 - 1958

Ref.: FA5281

Artistic Direction : ALAIN TERCINET

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Total duration of the pack : 2 hours 35 minutes

Nbre. CD : 2

FROM HOLLYWOOD TO LOS ANGELES 1950 - 1958

FROM HOLLYWOOD TO LOS ANGELES 1950 - 1958

“You know, we never made any premeditated attempt to play anything different or specific that could be labelled “West Coast Jazz”.” Shorty ROGERS

Directed by Alain Tercinet, this 2CD set present the great treasures of West Coast Jazz, recorded from Hollywood to Los Angeles between 1950 and 1958.

NEW YORK LOS ANGELES PARIS 1946-1955

SAN FRANCISCO - NEW YORK - LOS ANGELES 1948-1959

NEW YORK - HACKENSACK - LOS ANGELES 1953-1957

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Jolly RogersStan Kenton and his Orchestra00:02:431950

-

2A Mile Down The Highway There's A Toll BridgeJune Christy00:02:281950

-

3A ProposShorty Rogers And His Giants00:02:451951

-

4Soft ShoeGerry Millugan Quartet00:02:401952

-

5Viva Zapata N°1Howard Rumsey's Lighthouse All Stars00:03:231952

-

6Surf RideArt Pepper Quartet00:02:531952

-

7GazelleShely Manne And His Men00:03:021952

-

8Sweetheart Of Sigmund FreudShorty Rogers And His Giants00:02:461953

-

9RockerGerry Mulligan Tentet00:02:291953

-

10No TiesChet Baker Quartet00:03:011953

-

11Blues For BrandoShorty Rogers And His Giants00:02:591953

-

12Bones For ZootZoot Sims Quartet00:04:231954

-

13Doggin' AroundShorty Rogers And His Giants00:02:401954

-

14Dad's GrooveHoward Rumsey's Lighthouse All Stars00:03:171954

-

15CarinosoLaurido Almeida Quartet00:03:381954

-

16Abstract N°1The three00:03:361954

-

17Free FormChico Hamilton Quintet00:05:081955

-

18Lazy TonesJimmy Giuffre Quartet00:04:131955

-

19Frankly SpeakingLyle Murphy00:05:471954

-

20Sad SackHoward Rumsey's Lighthouse All Stars00:03:021954

-

21CharlestonJazz Studio 300:02:571955

-

22Martians Go HomeShorty Rogers Quintet00:07:531955

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1TNTCy Touff Octet00:04:581955

-

2Stanger In The RainMarty Paich Septet00:03:511955

-

3It's De LovelyBob Cooper Octet00:02:181955

-

4Dot's GroovyJack Montrose Quintet00:04:451955

-

5The Man I LoveDon Fagerquist Nonetet00:03:221955

-

6Circling The BluesLenny Niehaus Octet00:03:211955

-

7Sunday In SavannahDave Pell Octet00:03:571955

-

8Maybe Next YearDuane Tatro00:03:021955

-

9Sweet SueBill Usselton Sextet00:03:161956

-

10The SearchJohnny Mandel00:04:451956

-

11Blues For A PlayboyBarney Kessel00:04:051956

-

12The Train And The RiverJimmy Giuffre Trio00:03:351956

-

13New OrleansHoagy Carmichael00:03:551956

-

14CycleBuddy Colette Octet00:02:551956

-

15ThemeBud Shank Quartet00:05:251956

-

16Songs Of The IslandsBill Perkins Octet00:03:571956

-

17Nice Work If You Can Get ItMell Torme00:03:161957

-

18BroadwayTed Brown Sextet00:06:061956

-

19Sophisticated RabbitShelly Manne And His Men00:03:281958

-

20A Geophisical EarShorty Rogers And His Giants00:03:491957

JAZZ WEST COAST

JAZZ WEST COASTFROM HOLLYWOOD TO LOS ANGELES 1950-1958

Shelly Manne : “Toutes les affaires étaient faites par un petit nombre de musiciens. Ainsi quand Shorty Rogers avait un engagement, j’étais à la batterie et Jimmy Giuffre au ténor. Si j’en avais un, Shorty était à la trompette et Giuffre au ténor. Et ainsi de suite. Alors naturellement le son restait le même. C’était le nôtre et il est devenu un style.” (1) Et c’est ainsi qu’un natif du Massachusetts - de Great Barrington plus précisément - assisté par un New Yorkais bon teint et un Texan venu de Dallas inventa “le jazz californien”. À son insu. “Nous n’avons jamais eu l’intention de jouer quelque chose de différent et de spécifique qui puisse être baptisé “Jazz West Coast” avoua Shorty Rogers (2). Genèse d’un phénomène jugé à l’époque comme vaguement sulfureux et à propos duquel il ne fut pas exagéré de parler d’apostasie, à tout le moins d’hérésie.

Tout débuta en décembre 1951. Revenu en Californie, base arrière de ses activités, Stan Kenton décida d’y dissoudre son orchestre “Innovations in Modern Music”. Un ensemble aussi ambitieux que pléthorique qui lui avait fait perdre quelque deux cent mille dollars. En faisait partie depuis la fin janvier 1950, Milton Michael Rajonski alias Shorty Rogers, trompettiste et arrangeur. L’un de ses tous premiers travaux – sinon le premier – annoncé en concert comme An Expression from Rogers reçut au studio le titre de Jolly Rogers ; un jeu de mots qui, on le verra, en préfigurait bien d’autres dans l’intitulé des morceaux liés à Shorty. Une partition brillante, assez différente des œuvres signées par les autres arrangeurs de l’orchestre Kenton. De Pete Rugolo à Johnny Richards en passant par Bob Graettinger : Shorty reconnaissait avoir subi deux influences, le grand orchestre de Count Basie avec Harry “Sweets” Edison puis le Nonet de Miles Davis. Une emprise qui saute à l’oreille lors d’une séance organisée en 1950. La vedette en était la chanteuse de l’orchestre Kenton, June Christy qui, épouse du saxophoniste Bob Cooper, deviendra la vocaliste emblématique du “Jazz West Coast”. La sonorité des ensembles sur A Miles Down the Highway There’s a Toll Bridge n’autorise aucun doute quant à la source de son inspiration ; ce que confirmera peu après la séance “Modern Sounds” gravée en septembre 1951. À ce moment-là, Shorty Rogers n’appartient plus à l’ensemble “Innovations in Modern Music”. Épuisé par un régime ininterrompu de tournées subi depuis longtemps, ayant réalisé que ses trois premiers enfants étaient nés en septembre en fonction de ses seuls congés accordés à Noël, il avait abandonné l’orchestre durant l’été. En conservant toutefois des liens étroits avec les membres de la formation puisque, à l’exception de Jimmy Giuffre et d’Hampton Hawes, tous les participants à la séance “Modern Sounds” en faisaient partie. L’instrumentation était pratiquement identique à celle du “Birth of the Cool Band” de Miles Davis et la perfection formelle semblable. L’esprit, lui, était bien différent. Incurable optimiste, doté d’un solide sens de l’humour, Shorty revendiquait le droit à un “jazz de plaisir”. Les exclamations d’encouragement que se prodiguent les interprètes au long de A Propos ne laissent guère de doute sur leur ralliement à cette vision de la musique.

À leur tour lassés par les tournées, nombreux furent ceux qui, venus de la formation de Stan Kenton, décidèrent d’imiter Shorty Rogers - Art Pepper, Bud Shank, Milt Bernhart, Shelly Manne, Bob Cooper, John Graas entre autres. Pour un jazzman, s’installer à Los Angeles n’était pas choisir la facilité. La Californie possédait certes des atouts - de son climat au mode d’habitat en maisons individuelles qui favorisait le travail personnel - mais, sur le plan du jazz, c’était un désert. L’époque des vaches grasses concomitante à la multiplication des usines aéronautiques et navales qui suivit l’entrée en guerre des Etats-Unis, était bien terminée. Alors rivale de la 52ème Rue new-yorkaise, Central Avenue avait vu disparaître la quasi totalité de ses clubs, les rescapés se souciant fort peu du jazz. En désespoir de cause les musiciens avaient gagné l’Est ; seuls quelques irréductibles tels Sonny Criss, Hampton Hawes ou Curtis Counce décidèrent de demeurer sur place. John Graas : “Nous savions qu’il allait être difficile de trouver du travail. Nous avons même pensé, un moment, louer une vieille grange et la transformer en boîte de nuit seulement nous n’avions pas songé qu’il nous fallait une licence pour vendre des alcools. Donc, au début, ça n’a pas été tout seul. La région était le fief du Dixieland. Les patrons de clubs d’Hollywood et de Los Angeles ne voulaient pas entendre parler d’autre chose. Malgré nos cartes syndicales, nous n’avons pu trouver de travail fixe pendant six mois.” (3) Lorsque, par miracle, un engagement était déniché, il s’avérait peu gratifiant : Bud Shank entra dans la formation d’un certain George Redman qui, cinq soirs par semaine, organisait des compétitions de… jitterbug.

Au cours de l’un de ses congés, Shorty Rogers s’était lié d’amitié avec un ex-bassiste de l’orchestre Kenton - californien d’origine - , Howard Rumsey, qui lui avait proposé de jouer durant son temps libre dans le club qu’il dirigeait à Hermosa Beach, le Lighthouse. Un établissement dont le décor faussement polynésien avait perdu beaucoup de son pouvoir d’attraction depuis la guerre du Pacifique. Dans cette salle de cent quatre-vingt places dotée d’une estrade, Howard Rumsey avait suggéré au nouveau propriétaire qui ne savait qu’en faire, de présenter un orchestre de jazz. Le 29 mai 1949, un dimanche après-midi, le coup d’envoi fut donné par un quintette composé de Don Dennis à la trompette, Dick Swink au ténor, le pianiste Arnold Kopitch, Bobby White à la batterie et, naturellement, Howard Rumsey à la basse : “J’ai engagé les musiciens les plus bruyants que j’ai pu trouver et nous avons démarré en laissant les portes ouvertes. Le public a commencé à venir. Bientôt la salle a été pleine. Il y avait plus de clients que Levine n’en avait vus durant les quinze jours précédents.” (4) Au long des deux années suivantes, le Lighthouse amplifia ses activités, attirant des musiciens comme Teddy Edwards, Sonny Criss, Hampton Hawes ou Wardell Gray. Shorty avait éprouvé un grand plaisir à jouer au Lighthouse aussi, lorsqu’il abandonna l’orchestre Kenton, se tourna-t-il tout naturellement vers Howard Rumsey. Le bassiste décida alors de constituer un orchestre permanent dont la première mouture réunissait le maître des lieux à la contrebasse, le pianiste Frank Patchen, le batteur Shelly Manne, lui aussi ex-Kentonien, Shorty Rogers et l’un de ses amis rencontré à l’époque de leur appartenance commune au “Second Herd” de Woody Herman, le ténor Jimmy Giuffre ; l’auteur de Four Brothers venait d’arriver en Californie. Sur son élan, Rumsey décida d’enregistrer un 45 t qui serait vendu au Lighthouse comme souvenir. Il comportait un mémorable Big Boy sur lequel Giuffre se livrait à un numéro de ténor hurleur parfaitement réjouissant. Un clin d’œil adressé au R’N’B’ mis à la mode en Californie par Big Jay McNeely qui jouait du saxo en se roulant sur le dos. Un orchestre fantôme prolongea un temps la plaisanterie sous l’appellation de “Boots Brown and His Blockbusters” ; “Boots Brown” n’était autre que Shorty et les “champions du box office”, ses partenaires habituels ou occasionnels. De Gerry Mulligan à Barney Kessel en passant, bien sûr, par Jimmy Giuffre. Le “Lighthouse All Stars” accueillait volontiers les invités : le 6 janvier ce furent Milt Bernhart au trombone et Art Pepper à l’alto ; suivirent Gerry Mulligan, Stan Getz, Zoot Sims, Miles Davis, Chet Baker et bien d’autres. Ils sautaient sur l’occasion offerte par les concerts du dimanche, véritables marathons débutant à deux heures de l’après-midi pour se terminer… douze heures plus tard. Au début, il s’agissait de simples jam-sessions sur Tickle Toe , Yesterdays ou Another Hair-Do. Avec l’utilisation de compositions originales écrites et arrangées par les participants comme Viva Zapata n°1 qui mettait en avant le goût de Shorty pour les rythmes afro-cubains, Howard Rumsey pourra revendiquer pour ses prestations du dimanche la qualité de “Jazz Concerts”. Une initiative qui ne souleva pas un enthousiasme délirant chez des édiles accoutumés aux surfers et aux volleyeurs : “Quand se répandit la nouvelle qu’une bande de musiciens bop se livraient à des jam-sessions le dimanche au Lighthouse, le conseil municipal d’Hermosa Beach envisagea sérieusement de prendre un édit qui nous aurait conduit à la faillite” (5). Shorty Rogers : “Le dimanche, il y avait du jazz toute la journée. Le Lighthouse était à un demi-bloc de la plage. Certains venaient l’après-midi en maillot de bain. Lors de la fermeture à deux heures du matin, certains d’entre eux étaient encore là… toujours en maillot de bain.” (6) Un soir, alors qu’il avait été invité à se joindre à un groupe de clients, l’un d’entre eux, le compositeur Leith Stevens, proposa à Shorty de travailler sur les orchestrations d’une musique de film qui lui avait été commandée. Shorty accepta immédiatement une tâche qui lui permettait de mettre un pied dans les studios hollywoodiens, lui donnant aussi l’opportunité d’y introduire plus tard ses amis. Peu de temps après, Shorty Rogers eût en charge la composition d’une partie de la musique destinée à “The Wild One” (L’équipée sauvage). Etait-ce grâce à Marlon Brando qui venait l’écouter régulièrement au Zardi’s lorsqu’il s’y produisait ? Mystère. Blues for Brando au long duquel brille Bill Perkins fut probablement gravé en vue d’être intégré à la bande sonore du film de Laslo Benedek. De son côté, Shelly Manne n’était pas en reste : “La première fois que l’on m’a convoqué pour faire un job de studio, j’ai rempli mon contrat alors que c’était en fait très difficile. Comme c’était une musique proche du jazz, ils avaient fait appel à un jazzman. Il s’agissait de jouer en lecture à vue la partition de Leonard Bernstein “Fancy Free” écrite en 5/4. À l’époque c’était inhabituel. Je l’ai donc fait et depuis j’ai été convoqué pour jouer toutes sortes de musiques. Ils avaient compris que je pouvais tout jouer et du coup, ils ont engagé de plus en plus de jazzmen.” (7) Bud Shank le confirmera bien des années plus tard : “Avant que Shorty ne fasse sa première orchestration pour Leith Stevens les musiciens de jazz n’étaient pas autorisés à pénétrer dans les studios de cinéma. […] Et puis tout d’un coup : Hé, mais ces gars-là savent lire la musique et puis celui-là sait jouer du hautbois, cet autre de la flûte, et lui, de la clarinette. Regardez-moi ça, j’aurais jamais cru que c’était possible.” (8) Les musiciens de jazz se voyaient enfin offrir l’occasion de s’affranchir de toute contingence commerciale dans leur propre musique. L’arrivée de compositeurs, d’arrangeurs, d’interprètes venus du jazz bouleversa quelque peu la musique de film. Une métamorphose à laquelle contribua Elmer Bernstein qui, en 1955, fit appel à Shorty pour “The Man with the Golden Arm”, une production prestigieuse signée Otto Preminger. Suivront les partitions de “I Want to Live” (Johnny Mandel), de “Sweet Smell of Success” (Chico Hamilton), mais ceci est une autre histoire…

En 1952 Ralph Gleason, correspondant en Californie du magazine “Down Beat” et chroniqueur réputé au “San Francisco Chronicle”, avertit ses lecteurs qu’au bord du Pacifique, il se passait enfin quelque chose qui soit digne d’intérêt musicalement parlant. Venu en Californie vendre des arrangements à Stan Kenton, le saxophoniste baryton Gerry Mulligan - l’un des maîtres d’œuvre du fameux “Nonet” de Miles Davis - s’était vu proposer au printemps l’animation des soirées du lundi au Haig’s . Un petit club situé à Los Angeles sur Wilshire Boulevard dont Richard Bock assurait la promotion. Il avait seulement demandé à Mulligan de se débrouiller avec les musiciens disponibles sur le moment. Parmi eux, un trompettiste nouveau venu que Charlie Parker avait choisi comme interlocuteur en Californie, Chesney H. Baker. Mulligan : “C’est l’un des meilleurs musiciens intuitifs que j’aie jamais connus.” (9) Naquit alors le “Gerry Mulligan Quartet” composé d’une trompette, d’un saxo baryton, d’une basse et d’une batterie ; pas de piano. Une instrumentation hors norme qui rencontra un succès public immédiat appelé à s’étendre, à la fin de l’année, hors de la Californie grâce à la publication d’un disque 78 t . Richard Bock s’était laissé persuader de créer un label, Pacific Jazz, destiné à jouer un rôle important dans la diffusion du jazz de la West Coast. Par son climat musical privilégiant la sobriété et le naturel, en usant sur un thème séduisant de contrepoints improvisés évoquant les traditionnelles improvisations collectives, Soft Shoe peut être considéré comme le parangon du travail de Mulligan en quartette. Un ensemble dont l’existence sera éphémère (moins d’un an ) ; celle du “Tentet” le fut encore plus. Mulligan : “Pendant que nous jouions au Haig’s avec le quartette, j’avais mis sur pied un Tentet en tant qu’orchestre de répétition afin d’avoir l’occasion d’écrire pour un ensemble […] Je pense que, musicalement, il fonctionnait parfaitement autour de l’idée qui servait de base au quartette et il était très facile d’écrire pour lui. J’aurais voulu continuer l’expérience à l’époque mais c’est la vie.” (10) Bob Enevoldsen qui tient la partie de trombone à pistons dans Rocker : “C’était une musique inhabituelle pour l’époque. Elle était différente.” (11) Nombre d’arrangeurs californiens (dont Bill Holman) s’en souviendront. Avec une certaine mauvaise foi, Mulligan niera toujours avoir entretenu le moindre rapport avec le jazz de la Côte Ouest. Qu’importe. En raison de sa brusque célébrité, il avait attiré le feu des projecteurs sur les bords du Pacifique, tout en révélant un musicien, Chet Baker. Qui, maintenant à la tête de son propre quartette, faisait un malheur. Photogénique en diable, couvert de groupies, submergé par les fans, il semblait incarner à lui seul la musique californienne. Malheureusement plus en raison de son physique et du mode de vie qu’il avait adopté qu’en raison de son talent dont No Ties fournit une preuve irréfutable.

Lorsqu’au début de 1954 Gerry Mulligan quitta les bords du Pacifique, le jazz “West Coast” n’était plus dans l’état où il l’avait trouvé. L’année précédente Shorty Rogers avait pris la tête des “Giants”, une formation à géométrie variable qui lui permettait de donner libre cours à son éclectisme et à sa fantaisie. Tiré de l’album “Cool & Crazy”, Sweetheart of Sigmund Freud dont le titre répondait bien à celui du LP, était exposé par… trois saxophones barytons. Fait suffisamment rare alors pour être signalé, il rendra aussi hommage à un musicien vivant, Count Basie. Dans l’album “Shorty Rogers Courts the Count” - une complète réussite - , se détache Doggin’ Around en raison de l’irréprochable chorus pris par Zoot Sims. L’année suivante, en compagnie de ses complices de la première heure, Jimmy Giuffre et Shelly Manne, Shorty participait à l’album “The Three” ; sans rapport aucun avec “Cool & Crazy”… “Nous avions tous les trois le goût des choses expérimentales et ce disque reste intéressant. J’en ai écrit tous les morceaux. J’avais trouvé des petits stratagèmes qui, à ma connaissance, n’avaient jamais été utilisés et certainement pas par les compositeurs dodécaphonistes. Il s’agissait d’adapter ce système à la situation du jazz et d’obtenir différentes progressions harmoniques” (12). À cette période, Shorty et Jimmy Giuffre suivaient l’enseignement du Dr. Wesley La Violette, gourou plus que professeur, qui aidait ses élèves à se connaître afin qu’ils puissent tirer le meilleur parti du champ musical dans lequel ils entendaient évoluer. Ne rejetant aucun domaine musical, sa pédagogie prenait en compte toutes les avant-gardes jusque-là inconnues de la majorité des jazzmen. Pour avoir été le rythmicien de l’orchestre Kenton lors de ses incursions musicales les plus téméraires, Shelly Manne savait ce qu’expérimentation voulait dire. Dans le volume 1 de “Shelly Manne and His Men” - formation qui n’aura d’existence permanente qu’à la fin de 1955 – , figuraient divers arrangements audacieux pour l’époque, dont Gazelle signé Bill Russo. Le volume 2, lui, contenait entre autres une pièce atonale de Jimmy Giuffre. Batteur mélodiste, Shelly succombait souvent à la tentation d’introduire l’incongru dans un contexte “classique” : au cours de Martians Go Home, il fit tourner une pièce d’un demi-dollar sur le tom basse. En guise de break… “The Three” contenait Abstract n°1 avec lequel le triumvirat du “Jazz West Coast” relevait un défi lancé en 1949 par Lennie Tristano par le biais d’ Intuition : improviser à plusieurs sans aucun schéma pré-établi. Shorty : “C’est le résultat d’un travail d’équipe poussé à l’extrême. Les oreilles grandes ouvertes nous nous écoutions pour prolonger et compléter nos idées mutuelles. Nous travaillions depuis si longtemps ensemble qu’il s’était développé entre nous une compréhension dans l’improvisation qui pouvait se manifester dans un arrangement ou dans une partie libre.” (13) En 1955, les membres de l’une des formations les plus singulières et les plus passionnantes du moment, le “Chico Hamilton Quintet” renouvelèrent l’expérience. En public, au “Strollers”, Buddy Collette, le violoncelliste Fred Katz, Jim Hall à la guitare, Carson Smith et Chico Hamilton - deux anciens du Gerry Mulligan Quartet - servirent Free Form. Avec une réussite égale à celle d’Abstract n°1. L’une et l’autre tentatives passèrent inaperçues, ne suscitant au mieux qu’un intérêt poli. Personne n’imaginait qu’elles préfiguraient un futur proche. À la décharge des critiques, il faut reconnaître, qu’à cette période, vouloir suivre ce qui s’inventait simultanément au bord du Pacifique pouvait donner le vertige.

Les pionniers du “Jazz West Coast” n’étaient plus seuls. Beaucoup de musiciens avaient répondu aux invites de Shorty Rogers qui, au cours de ses séjours dans diverses grandes formations, y avait noué nombre d’amitiés. Tous techniciens aguerris issus de minorités raciales italiennes, juives, irlandaises, slaves aux traditions musicales vivaces, ces jazzmen usaient d’un langage dont les fondements plongeaient dans la “Swing Era”. De la révolution be-bop, quelques-uns avaient tiré des enseignements sur un plan harmonique ou rythmique. Shorty Rogers, Shelly Manne, Frank Rosolino, Claude Williamson et quelques autres en connaissaient les tenants et les aboutissants. Du fait des tournées continuelles qui les isolaient, d’autres n’en possédaient qu’une très vague idée – l’un d’entre eux avoua n’avoir entendu Parker qu’au début des années 50… En sus le bop était le fruit d’une révolte noire. Ils ne voyaient donc pas la nécessité de s’y dévouer corps et âme, préférant, sans ostentation ni sectarisme, conquérir leur indépendance. Quitte à puiser à l’occasion dans le vaste réservoir alimenté par la musique européenne. Leur patrimoine. Jim Hall : “J’ai toujours considéré que la musique de jazz était partie des Noirs, mais c’est maintenant la mienne autant que celle de quiconque. Je n’ai volé la musique de personne, je lui ai apporté seulement quelque chose de différent.” (14) À Los Angeles, chacun s’employait à cultiver son jardin, tout en se mettant à la disposition des autres avec la meilleure grâce du monde. S’en suivra un chassé-croisé de musiciens – souvent les mêmes - au long de séances divergentes tant par l’esprit que par la lettre. Pacific Jazz, Contemporary, Capitol, mais aussi Nocturne, Andex ou Discovery, tous labels locaux, se bousculaient pour offrir au chaland le plus grand nombre possible de microsillons agrémentés de pochettes au graphisme aussi inventif qu’attractif, souvent ornées de photos – remarquables - de William Claxton.

Shelly Manne : “Ce qui caractérisa le style West Coast, ce fut de prendre en considération la composition et aussi de s’intéresser à l’expérimentation.” (15) Serait-il abusif de sous-entendre, qu’en cet endroit, à ce moment-là, l’écriture faisait jeu égal avec l’expression individuelle ? Sans pour autant brimer les purs improvisateurs. Surf Ride interprété par Art Pepper, Bones for Zoot dû à Zoot Sims, Theme joué par Bud Shank, Blues for a Playboy signé de Barney Kessel prouveraient si besoin était la pérennité du langage spontané. Des interprétations qui, à l’image de ce qui se jouait alors au bord du Pacifique, ne souffrent à aucun moment d’un quelconque laisser-aller. Ce qui ne les distingue guère des pièces bénéficiant, elles, d’arrangements, écrits ou “de tête”, destinés à ces moyennes formations au travers desquelles le jazz de la West Coast exprima le mieux son art poétique. Sextette, septette, octette, autant de formules instrumentales qui, dans la mouvance du Nonet de Miles Davis, conjuguaient liberté et discipline dans la recherche d’un son d’ensemble. Un domaine sur lequel l’empreinte de Lester Young sur les saxophonistes – majoritaires ici - s’affirmait suffisamment forte pour que l’on parlât, non sans malice, de musique “ténorisée”. La prise de conscience de ce ralliement global à l’esthétique sonore défendue par le Président piqua l’imagination des arrangeurs. Certains improvisateurs adoptèrent, eux, des instruments jusqu’alors inusités. Piliers de la seconde génération du “Lighthouse All-Stars” en compagnie de Frank Rosolino – voir Sad Sack - , Bud Shank et Bob Cooper proposèrent un Bag’s Groove interprété respectivement à la flûte et au hautbois. John Graas éleva le cor à la dignité d’instrument soliste (Charleston) alors que Cy Touff réhabilitait la trompette-basse (TNT). Jimmy Giuffre, Buddy Collette remettaient la clarinette à l’honneur et le saxophone baryton, instrument d’élection de Gerry Mulligan, devenait incontournable tenu par Bob Gordon ou par les multi-instrumentistes qu’étaient Bud Shank, Bob Cooper et Jimmy Giuffre. Afin de faire varier le son des ensembles, les arrangeurs s’amusaient à concocter des alliages instrumentaux inédits, voir incongrus : trompette / quatre saxophones (The Man I Love – Don Fagerquist), saxophone ténor, trombone et clarinette-basse chez Billy Usselton (Sweet Sue), deux ténors et un alto (Broadway – Ted Brown), un saxophone ténor et un baryton (Dot’s Groovy - Jack Montrose). Thèmes originaux, standards, compositions anciennes (Charleston, Sweet Sue), tout était bon pour servir de tremplins à ceux qui possédaient un tant soit peu d’imagination.

Émise à propos du seul Shorty, l’opinion de Ted Gioia définit fort bien la quasi totalité de ce qui fut joué au bord du Pacifique : “La musique de Shorty Rogers illustre ce que le courtisan italien Castiglione appelait “sprezzatura” - la faculté de faire des choses difficiles avec une apparente facilité”. (16) Lennie Niehaus pouvait user de constants changements de tonalités au cours de Circling the Blues tout comme Buddy Collette dans Cycle, Lyle Murphy appliquer à Frankly Speaking une forme de dodécaphonisme dont il était l’inventeur, Duane Tatro se référer, dans Maybe Next Year, au système inventé par Arnold Schoenberg, jamais, au grand jamais ces innovations n’engendraient une musique rébarbative. À l’oreille, rien ne distinguait vraiment le fruit des recherches sophistiquées de partitions moins audacieuses comme la jolie version du It’s De Lovely de Cole Porter revu par Bob Cooper, de Sunday in Savannah habillé de neuf par le trompettiste Wes Hensel à l’attention de l’octette de Dave Pell ou de Song of the Islands dans lequel Bill Holman s’amusait à transcrire pour les ensembles le chorus interprété par Lester Young dans la version originale. Autant d’occasions offertes à des interprètes souvent méconnus de montrer leur valeur. À l’exemple de l’excellent trompettiste Don Fagerquist ou du saxophoniste ténor Bob Hardaway, remarquable sur Stranger in the Rain au sein de l’octette de Marty Paich. Associés à des vocalistes, les arrangeurs mettaient un point d’honneur à rechercher l’accord parfait entre accompagnateurs et accompagné. Une entente qui pouvait se manifester de façon inattendue, à l’exemple de la complicité née, au-delà des années, entre l’ancien compagnon de Bix Beiderbecke, Hoagy Carmichael et Art Pepper sur New Orleans. Considéré dans ce domaine comme la Rolls Royce des formations, le “Marty Paich Dek-Tette”, recherché aussi bien par Ella Fitzgerald que par Sammy Davis Jr., atteignit à des sommets en compagnie de Mel Tormé sur Nice Work If You Can Get It . À l’issue d’un survol du Jazz West Coast, il appert qu’aucun de ses musiciens ne s’est vraiment soucié de pousser plus avant ses recherches. Deux explications à cela : la brève durée de son époque créative et la boulimie musicale propre à ses serviteurs. “En tant que musicien de jazz, on brûlait de curiosité de découvrir comment on pouvait transformer quelque chose ; on relevait ces défis et puis on passait à autre chose” constatait Bud Shank (17). Quelqu’un qui, pourtant, fut l’un des acteurs de la seule initiative née sur la Côte Ouest qui se soit prolongée au fil des ans. “En 1953 au moment où Gerry et Chet étaient au Haig’s, je m’y produisais le lundi, jour de relâche, avec Laurindo Almeida, Harry Babasin et Roy Harte. Ce groupe avec Almeida est né au Haig et c’était l’idée d’Harry de nous réunir.” (18) Roy Harte : “Nous avons répété pendant à peu près un mois, Harry assurant à la basse la direction rythmique. Au vrai nous répétions pour voir si Laurindo pouvait swinguer. Nous savions tous quel grand guitariste il était, cependant nous voulions nous assurer qu’il lui était possible de swinguer dans un contexte jazz. Notre but essentiel était d’arriver à une sorte de baião/jazz - nous trouvions la samba ringarde - en retrouvant la pulsation légère du baião combinée à celle du jazz. Pour ce faire, j’utilisais les balais non pas sur une caisse claire mais sur une conga, ce qui apportait de la légèreté. Au vrai, je tentais d’assurer de la main droite la pulsation jazz nécessaire à Bud et, de la gauche, j’apportais la couleur brésilienne en accord avec le jeu de Laurindo.” (19) Au mois d’avril 1953, le quartette entra dans un studio d’enregistrement pour mettre en boîte six morceaux destinés à un LP 25 cm. Signé du compositeur brésilien Pixinguinha, Carinoso en faisait partie. Une expérience qui ne fut certes pas à l’origine de la bossa nova mais conforta dans leurs recherches quelques jeunes musiciens brésiliens comme Antonio Carlos Jobim, João Gilberto ou Roberto Menescal. Qui, par ailleurs, faisaient leur miel des albums “Pacific Jazz”, fort bien distribués à Rio.

De 1955 à 1958, le jazz californien vécut son apogée. N’ayant rien perdu de leur allant, Shorty Rogers et Shelly Manne avançaient chacun dans une voie moins semée d’embûches que celles précédemment explorées. À leurs yeux, l’expérimentation n’en était plus une à partir du moment où elle devenait une habitude et ce qui avait été fait dans ce domaine avait été bien fait, donc pourquoi insister. The Geophysical Ear de Shorty adressait un clin d’œil à Jolly Rogers, l’écriture pour grande formation offrant encore bien des occasions de s’amuser. À la tête de ses “Hommes”, Shelly Manne offrait un Sophisticated Rabbit dont les audaces se paraient d’un voile de classicisme. Le troisième membre du triumvirat, Jimmy Giuffre - il ne commença à enregistrer sous son nom qu’à plus de trente ans - entamait un itinéraire exigeant qui fera de lui l’une des voix majeures du jazz moderne. Lazy Tones et The Train and the River dans lequel il renonçait à la pulsation de la batterie, en offrent les prémices. Un peu partout les années 60 sonnèrent le glas du jazz commercialement parlant. La Californie ne fit pas exception, The Jefferson Airplane renvoyant les Giants dans les studios où, quelquefois, ils assistèrent anonymement ceux qui les avaient détrônés. Shelly Manne, Pete Jolly, Frank Capp participèrent à l’album “Lumpy Gravy” de Frank Zappa ; sans faire la fine bouche. Le “Jazz West Coast” n’avait donc plus d’existence et nombre de ses serviteurs étaient en train de tomber dans les oubliettes de l’histoire. Bien des années passeront avant que l’on posât à son sujet les bonnes questions ; à propos de la spécificité de sa musique et la multiplicité de ses facettes. Sur sa légitimité aussi. Ne représentant guère que la partie émergée de l’iceberg, les quarante-trois interprétations ici réunies apportent peut-être quelques esquisses de réponses.

Alain Tercinet

© 2010 Frémeaux & Associés – Groupe Frémeaux Colombini

NOTES

(1) “Manne with the Golden Arms”, interview de Claude Carrière et Alain Tercinet – Jazz Hot n° 351/352, été 1978

(2) “The Gentle Giant” Howard Lucraft - Jazz Journal, fév. 1979

(3) “Écoutez-moi ça” Nat Shapiro et Nat Hentoff, trad. Robert Mallet – Buchet/Chastel, Paris, 1956

(4) Texte de pochette du LP “Howard Rumsey – In the Solo Spotlight” - Contemporary C 3517 (

5) “Hermosa Beach Almost Passed Law Banning Rumsey’s Bunch of Boppers” - Down Beat, 11 mars 1953

(6) “The Gentle Giant” Howard Lucraft - Jazz Journal, fév. 1979 (7) “Manne with the Golden Arms”, interview de Claude Carrière et Alain Tercinet – Jazz Hot n° 351/352, été 1978

(8) “Shorty Rogers - Bud Shank”, interview de Kirk Silsbee – Cadence, juin 1999 (

9) Livret “The Original Gerry Mulligan Quartet with Chet Baker” – coffret Mosaic

(10) Texte de pochette du LP “Gerry Mulligan Tentette” - Capitol Jazz 5CO52.80 801

(11) “Bob Enevoldsen”, interview de Bob Rush – Cadence, avril 1991

(12) “Shorty le géant”, interview de Gérard Rouy – Jazz Magazine n° 348, avril 1986

(13) Texte de pochette du LP “The Three” - Contemporary C 2516 (

14) Nat Hentoff “Jazz is…” - Random House, NYC 1976

(15) “Manne with the Golden Arms”, interview de Claude Carrière et Alain Tercinet – Jazz Hot n° 351/352, été 1978

(16) Ted Gioia “West Coast Jazz” - University of California Press, 1992

17) Barney Hoskyns “Waiting for the Sun”, trad. Héloïse Esquié et François Delmas – Editions Allia, Paris 2004

(18) Gordon Jack “Fifties Jazz Talk – An Oral Retrospective”, Studies in Jazz n° 47 – The Scarecrow Press Inc., Lanham, Maryland, 2004

(19) Pete Welding Texte de livret du CD “Laurindo Almeida/Bud Shank - Braziliance vol. 1” - World Pacific CDP 7 96339 2

..................................

English Version

According to Shelly Manne, “All the bookings were done by just a small number of musicians. So when Shorty Rogers had a gig, I was the drummer and Jimmy Giuffre played tenor. If I had one, Shorty played trumpet and Giuffre was the tenor. And so on. So naturally the sound remained the same. It was our sound, and it turned into a style.” (1) With the assistance of one New Yorker and one Dallas Texan, a native of Massachusetts had invented “California jazz”... in blissful ignorance of the term. “You know, we never made any premeditated attempt to play anything different or specific that could be labelled “West Coast Jazz”, confessed Shorty Rogers (2). It was the genesis of a phenomenon. Some vaguely detected the smell of sulphur in it, while others referred to it as the “abandonment of all belief”, or heresy at the very least. It all began in December 1951. Stan Kenton had returned to base in California and decided to disband his “Innovations in Modern Music” group, in part because the ambitions of the orchestra had cost him in excess of two hundred grand... A certain Milton Michael Rajonski, alias trumpeter/arranger Shorty Rogers, had been a member of the band for two years and one of his first jobs was Jolly Rogers, heralding more puns to come in titles associated with the arranger. A brilliant score, it was rather different from pieces Pete Rugolo and others had done for Kenton, and Shorty admitted to two major influences: the Basie orchestra (Edison version) and the Miles Davis Nonet. Their hold on Shorty leapt off the page in a session set up in 1950 for Kenton’s singer June Christy, and the ensemble-playing in Toll Bridge leaves no doubt as to the source of Shorty’s inspiration. Shorty left Kenton after realising that his first three children all had birthdays in September, as a direct consequence of the band’s mandatory Christmas holidays... he was exhausted by all the touring and he quit in the summer, although he remained close to many from the band. The line-up of his «Giants» was practically identical to Miles Davis’ “Birth of the Cool Band”, and its formal perfection was similar, too, although the idea behind the concept was quite different: an incurable optimist with a solid sense of humour, Shorty’s motto was “jazz for pleasure”, and the shouts of encouragement exchanged throughout A Propos show everyone agreed with his musical vision... The touring soon led others to imitate Shorty, among them Art Pepper, Bud Shank and Shelly Manne, even though regular work in jazz had almost deserted California (nearly all the L.A. clubs on Central Avenue had closed after the industrial boom ended). John Graas was another victim: “We knew it was going to be hard to find work. We even thought for a while of renting an old barn to use as a night club, but we hadn’t realized that we’d need a liquor licence and things like that. So things were rough at first. That was all Dixieland territory then. The Club owners in Hollywood and Los Angeles wouldn’t hear of anything but Dixieland. Well, we had our cards in at the local, so in any case we couldn’t do any steady work for six months.” (3) If by miracle a gig did materialise, it often turned out a chore: Bud Shank joined George Redman and found himself playing jitterbug contests five nights a week!

It was while on one of his few holidays that Shorty became friends with ex-Kenton bassist Howard Rumsey, a Californian who ran a club (with a fake Polynesian interior) on Hermosa Beach called “The Lighthouse”. He invited Shorty over to play. The club’s owner, John Levine, hadn’t known what to do with the place when he’d bought it, and Rumsey had suggested jazz: they’d opened one Sunday afternoon in May 1949 with a quintet that (naturally) featured Rumsey on bass: “I hired the loudest musicians I could find. We propped the front doors open and started to blast off. The people began to filter in. Pretty soon the place was full. There were more people than Levine had had in the entire preceding two weeks.”(4) Shorty had loved playing there and so, when he quit Kenton, he turned to Howard Rumsey. Howard decided to set up a house band, and its first line-up included Rumsey, drummer Shelly Manne (another Kenton alumnus), Shorty Rogers, and one of his pals from Woody Herman’s “Second Herd”, tenor player Jimmy Giuffre, who’d just come to California. Rumsey made a single — Big Boy — with Giuffre wailing on tenor, and the band lived for a time as “Boots Brown and His Blockbusters” (Shorty was Boots, the others being variously Gerry Mulligan, Barney Kessel et al.) This, in fact, was the “Lighthouse All Stars”, whose guests included Art Pepper on alto, Getz, Zoot Sims, Miles Davis, Chet Baker and many, many others who jumped at the chance of playing Sunday concerts that often turned into 12-hour marathons. Initially they were jam-sessions, based on Tickle Toe , Yesterdays or Another Hair-Do, but thanks to original compositions with written arrangements — like Viva Zapata N°1, which shows Shorty’s taste for Afro-Cuban rhythms — these Sunday “matinees” soon earned themselves the title of “Jazz Concerts”, which did little to raise the enthusiasm of locals more interested in surf and volleyball: “When the word got around that a ‘bunch of bop musicians’ were doing Sunday jam sessions at the Lighthouse, the Hermosa Beach city council actually considered passing a special ordinance that would have put us out of business.” (5) As Rogers put it, “Sunday we had jazz all day. The Lighthouse is just half a block from the beach. People would come into the club in their bathing suits in the afternoon. And at two in the morning, when we closed, some of them would still be sitting there in their swimsuits.” (6) Nonetheless, Shorty did meet interesting people. Leith Stevens came in one afternoon, and they talked about a film-score Stevens was busy composing; Stevens asked him if he’d like to help out, and Shorty had a foot in Hollywood’s door. Shortly after (no pun), Rogers found himself writing part of the music for “The Wild One”. Did Brando have anything to do with that? It’s anyone’s guess, but Brando had been a regular visitor to Zardi’s when the trumpeter had been playing there. Blues for Brando, where Bill Perkins shines, was probably recorded for the soundtrack of Laslo Benedek’s film. Shelly Manne wasn’t far behind: “The first time I was called in to do a studio job, I honoured my contract although it was in fact very difficult; the music was close to jazz, so they’d called in a jazz man. The job was sight-reading Leonard Bernstein’s ‘Fancy Free’ score written in 5/4 time. So I did it and since then I’ve been called in to do all kinds of music. They realised I could play anything, and they began hiring more and more jazz people as a result.” Many years later, this was confirmed by Bud Shank, who said, “Prior to Shorty doing that first orchestration job for Leith Stevens, jazz musicians weren’t permitted in the film studios. (…) All of a sudden, ‘Hey, these guys can read, and that one plays an oboe and this one plays a flute, and that one plays clarinet – look at that. I didn’t think that was possible.’” (8) Jazz musicians were finally being given the chance to play their own music, unbound by commercial imperatives. And the arrival of jazz composers, arrangers and performers was turning films upside down, too: in 1955 Elmer Bernstein contributed to the metamorphosis by calling Shorty in to do Otto Preminger’s “Man with the Golden Arm”, and others followed suit.

In 1952 Ralph Gleason, California’s “Down Beat” correspondent and a critic at the “San Francisco Chronicle”, told his readers that something interesting, from a musical standpoint, was finally happening on the Pacific coast: baritone saxophonist Gerry Mulligan (who’d come down to sell arrangements to Stan Kenton) was playing at Haig’s on Monday nights. The Haig’s promoter had told Mulligan to avail himself of the local talent to get his group together, and among the talented was a trumpet-playing newcomer who’d already been picked out by Charlie Parker: his name was Chesney H. Baker. According to Mulligan, “Chet was one of the best intuitive musicians I‘ve ever seen.” (9) The Gerry Mulligan Quartet’s line-up was: trumpet, baritone saxophone, bass, drums. No piano. The exceptional format met with instant success, and by year-end its fame had spread beyond California thanks to a 78rpm record made for Richard Bock’s Pacific Jazz, a label destined to play a major role in spreading jazz all the way down the West Coast. With its music-climate giving preference to naturalness and sobriety, and a seductive theme whose improvised counterpoint passages recalled traditional collective improvisations, Soft Shoe can be seen as a model of excellence in the opus of Mulligan’s quartet. If that band lasted less than a year, Mulligan’s Tentet had an even shorter life. According to Mulligan, “When we were first playing at the Haig with the quartet, I started the tentet as a rehearsal band to have something to write for. (…) Musically I think the ensemble worked perfectly with the quartet concept and the band was very easy to write for. I would like to have pursued it further at that time but, c’est la vie…” (10) The valve-trombone heard in Rocker is played by Bob Enevoldsen, who said, “It was unusual music for that time. It was different than anybody else’s. (11) Many Californian arrangers, among them Bill Holman, would remember that. Somewhat dishonestly, Mulligan would always deny even the most tenuous links with West Coast jazz. Not that it mattered: his instant celebrity trained the spotlights on the Pacific and revealed Chet Baker, who was bringing the house down with his own quartet. Chet was handsome, drew fans in hundreds (and groupies like flies), and seemed to incarnate Californian music all by himself; unfortunately, his life-style and looks distracted the public’s attention away from his undeniable talent (No Ties). When Mulligan left the Pacific coast in ’54, “West Coast Jazz” was no longer the same. In 1953 Shorty Rogers had fronted the “Giants”, a group of varying size that allowed him to give free rein to his fantasy: taken from the album “Cool & Crazy”, Sweetheart of Sigmund Freud had its theme stated by no fewer than three baritone saxophones, something almost as rare as the fact that his next album, “Shorty Rogers Courts the Count”, paid homage to a musician who was still alive, Basie. All the tracks were great, but especially Zoot Sims’ impeccable chorus on Doggin’ Around. A year later came “The Three” (Giuffre, Manne, Rogers). According to Shorty, “All three of us had a taste for experimenting and this record is still interesting. I wrote all the tunes for it. I came up with a few little tricks that had never been used, certainly not by dodecaphonist composers. The point was to adapt that system to a jazz situation, and obtain different harmonic progressions.” (12) Shorty and Jimmy Giuffre were then following the teachings of one Dr. Wesley La Violette, more guru than professor, who assisted his pupils in getting the best out of the musical field in which they wanted to work. His teachings, which embraced all musical domains, even took in avant-gardes most jazzmen had never heard of... As the rhythmist of the Kenton orchestra in its wildest excursions, Shelly Manne knew exactly what “experimenting” meant, and he often succumbed to temptation in the form of incongruous intrusions in a more “classical” context: during Martians Go Home, he spins a half-dollar on his bass tom-tom by way of a break. Abstract n°1 comes from the album “The Three”. The “West Coast Jazz” triumvirate picks up the gauntlet Lennie Tristano had thrown down in 1949 with Intuition: several musicians improvising without a pre-established outline. In Shorty’s view, “It’s the product of extreme team work, keeping our ears open all the time, listening to each other, sequencing and completing each other’s ideas. We’ve worked together so long we’ve developed the ability to improve arrangements or abstracts.” (13) Chico Hamilton’s Quintet renewed the experience in 1953, just as successfully, with Free Form, yet both attempts received only polite attention, as nobody realised they were listening to the heralds of the future. Not that you could hold this against critics: it would have made any one of them dizzy trying to follow all the inventions coming from those Pacific shores...

The “West Coast Jazz” pioneers were no longer alone, as many musicians had responded to Shorty Rogers’ invitations, and these jazzmen used a language whose roots went back to the Swing Era. Some had absorbed the harmonic and rhythmical teachings of the bebop revolution, not only Manne and Rogers, but also men like Frank Rosolino. Others had only a vague idea — mainly due to being isolated from such events by being away on tour — and some confessed they hadn’t even heard Parker until the Fifties. On top of that, bebop was the harvest of a black rebellion, and so they hadn’t felt the necessity of devoting themselves to it body and soul in order to conquer their independence. The heritage of these musicians was the vast reservoir that stored the waters of European music. According to Jim Hall, “I’ve always felt that the music started out as black but that it’s as much mine now as anyone else’s. I haven’t stolen the music from anybody – I just bring something different to it.” (14) In Los Angeles everyone was digging his own patch, with each musician gracefully awaiting a call from the others; the result was that there was a lot of heavy two-way traffic on record-sessions, and these were as different as chalk and cheese both in spirit and in the flesh. Pacific Jazz, Contemporary and Capitol, but also local labels like Nocturne or Discovery, vied with each other in issuing as many LPs as possible for fans, usually with graphically inventive sleeves that were often adorned with the remarkable photographs of William Claxton. Shelly Manne: “What most characterized the West Coast style was the consideration given to the composing, and also the interest in experimenting.”(15) Would it be abusive to say that the composition, in that place and at that moment, was just as important as individual expressiveness? Which is not to belittle the pure improvisers: Surf Ride (Art Pepper), Bones for Zoot (Zoot Sims), Theme (Bud Shank) and Blues for a Playboy (Barney Kessel) provide ample proof of the spontaneous language’s everlasting importance. All these performances are like almost everything else that was played out on the Pacific coast in those days: not the slightest trace of casualness. This made them no different from the “arranged” pieces, either head-arrangements or the written varieties, which were destined for the average-sized bands where West Coast Jazz best expressed its poetic art. Sextet, septet and octet were as many instrumental formulae where, in true Miles Davis Nonet fashion, freedom and rigour were conjugated in search of an ensemble sound. With saxophonists outnumbering other instrumentalists — Lester Young was an influence, and there was banter about the music being “tenorized” — the sound-aesthetic defended by the Pres spurred the arrangers’ imaginations, and some soloists even adopted instruments that had rarely been seen of late: Bud Shank and Bob Cooper, along with Frank Rosolino, were mainstays of the second “Lighthouse All-Stars” generation – see Sad Sack – and the former two play flute and oboe respectively on Bag’s Groove. John Graas made the French horn a dignified solo instrument (Charleston), and Cy Touff rehabilitated the bass trumpet (TNT). Giuffre and Buddy Collette brought back the clarinet, and Mulligan’s favourite, the baritone, became a regular feature in the grip of Bob Gordon and multi-instrumentalists Shank, Cooper and Giuffre. To vary the sound of the ensemble, arrangers began concocting new instrumental alloys, some of them quirky: trumpet and four saxophones (The Man I Love), for example, or tenor, trombone and bass clarinet (Sweet Sue). Any combination was acceptable, as long as the performers showed some imagination.

Ted Gioia’s following remark (actually on the subject of Shorty Rogers) could serve equally to define almost everything played on the coast: “[The music] exemplifies what the Italian courtier Castiglione called spezzatura – the ability to do difficult things with apparent ease.”(16) Lennie Niehaus constantly changes keys in Circling the Blues, as does Buddy Collette in Cycle; Lyle Murphy invented the dodecaphonic form he applies to Frankly Speaking; and in Maybe Next Year Duane Tatro refers to the system invented by Schoenberg. But never, ever, did these innovations produce music that was unattractive. When you listen to them, nothing strikes the ear to differentiate them from the sophisticated research carried out with less daring scores, like Song of the Islands for instance, where Bill Holman had fun transcribing Lester Young’s original chorus for the ensemble-passages heard here. Arrangers associated with vocalists made it a point of honour to seek the perfect entente between the accompanists and the accompanied, and that entente could manifest itself in some very unexpected ways: listen to the complicity between Hoagy Carmichael and Art Pepper in New Orleans for example, and the “Marty Paich Dek-Tette”, considered an orchestral Rolls-Royce in this domain (and much sought-after by Ella Fitzgerald and Sammy Davis Jr.), reaches the summits in Nice Work If You Can Get It, in the company of Mel Tormé. After this cursory look at West Coast Jazz it appears that no musician really bothered pursuing his research. There are two explanations: the brevity of this creative era, and the musical binge-eating syndrome affecting its servants. “As jazz musicians we were burning with curiosity to discover how we could transform something; we picked up these challenges and then moved on to something else,” observed Bud Shank (17) and yet he was one of the actors in the only initiative born on the West Coast that continued over the years: “During 1953 when Gerry and Chet were at the Haig, I played there on Mondays, which were the off-nights, with Laurindo Almeida, Harry Babasin and Roy Harte. The Haig was where that group with Laurindo was born, and it was Harry’s idea for us to get together. ” (18) According to Roy Harte, “Actually, we rehearsed for our own education… Of course, we all knew how great Laurindo was as a formal guitarist, but we wanted to find out if he could really swing in jazz. I played brushes on a conga drum, not a snare drum. This gave it a light feeling. Actually, I was trying to play with my right hand to Bud’s jazz blowing, and with my left I was putting in the samba color with Laurindo’s playing.” (19) In April 1953 they recorded six titles including this Carinoso; it wasn’t the origin of bossa nova, but it did comfort some of the greatest young Brazilians in their own musical research (Jobim, João Gilberto and Roberto Menescal, all of them assiduous collectors of records released by the “Pacific Jazz” label.) Californian jazz was at its apogee from 1955 to 1958. To Shorty Rogers and Shelly Manne, an experiment wasn’t really an experiment when it became a habit, and what they’d already done (with excellence) was done. So why continue? Shorty’s The Geophysical Ear was a nice nod in the direction of Jolly Rogers (writing for a big band was still fun); Shelly Manne did Sophisticated Rabbit and hid its daring behind a classical veil; the triumvirate’s third member, Jimmy Giuffre — he didn’t record under his own name until he was over thirty — embarked on an exacting journey that would make him one of the major voices in modern jazz (Lazy Tones and The Train and the River, where he abandons the pulse of the drums, contain inklings of that.) Here and there, almost everywhere commercizlly speaking, the Sixties tolled the knell for jazz. California was no exception, and The Jefferson Airplane put the Giants back in the studios, where sometimes they assisted those who’d dethroned them (Shelly Manne plays on Zappa’s “Lumpy Gravy” for example). Many years went by before people began asking the right questions about West Coast Jazz, its specificity, its aspects and its legitimacy. The 43 performances here are only the tip of the iceberg, but perhaps they provide some of the answers.

Alain Tercinet

Adapted from the french text by Martin Davies

© 2010 Frémeaux & Associés – Groupe Frémeaux Colombini

NOTES

“Manne with the Golden Arms”, interview by Claude Carrière and Alain Tercinet, Jazz Hot N° 351/352, summer 1978 Howard Lucraft, “The Gentle Giant”, Jazz Journal, Feb. 1979

Nat Shapiro & Nat Hentoff, “Hear Me Talkin’ To Ya”, Dover Publications, June 1966

Sleeve notes, “Howard Rumsey – In the Solo Spotlight”, LP Contemporary C 3517 “

Hermosa Beach Almost Passed Law Banning Rumsey’s Bunch of Boppers”, Down Beat, March 11, 1953

Same as (2)

Same as (1)

“Shorty Rogers - Bud Shank”, interview by Kirk Silsbee, Cadence, June 1999

Booklet, “The Original Gerry Mulligan Quartet with Chet Baker”, Mosaic boxed-set

Sleeve notes, “Gerry Mulligan Tentette”, LP Capitol Jazz 5CO52.80 801

“Bob Enevoldsen”, interview by Bob Rush, Cadence, April 1991

“Shorty le géant”, interview by Gérard Rouy, Jazz Magazine N° 348, April 1986

Sleeve notes, “The Three”, LP Contemporary C 2516

Nat Hentoff, “Jazz is”, Limelight Editions,

2004 Same as (1)

Ted Gioia, “West Coast Jazz”, University of California Press, 1998

Barney Hoskyns, “Waiting for the Sun”, Backbeat Books, 2002

Gordon Jack, “Fifties Jazz Talk: An Oral Retrospective”, The Scarecrow Press, 2004

Pete Welding, sleeve notes, “Laurindo Almeida/Bud Shank - Braziliance vol. 1”, CD World Pacific CDP 7 96339 2

Discographie

CD 1

1 - STAN KENTON AND HIS ORCHESTRA: JOLLY ROGERS - Mx 5491-2, Capitol 1043 - 2’39

2 - JUNE CHRISTY: A MILE DOWN THE HIGHWAY THERE’S A TOLL BRIDGE - Mx 6563-7C, Capitol 1207 - 2’26

3 - SHORTY ROGERS & HIS GIANTS: A PROPOS - Mx 9121, Capitol 15764 - 2’41

4 - GERRY MULLIGAN QUARTET: SOFT SHOE - Mx 222, Pacific Jazz 606 - 2’35

5 - HOWARD RUMSEY’S LIGHTHOUSE ALL STARS: VIVA ZAPATA N°1 - Mx LH504, Contemporary 351 - 3’15

6 - ART PEPPER QUARTET: SURF RIDE - Mx D-6003-5, Discovery 158 - 2’49

7 - SHELLY MANNE & HIS MEN: GAZELLE - Mx C342, Contemporary C353 - 3’00

8 - SHORTY ROGERS AND HIS ORCHESTRA: SWEETHEART OF SIGMUND FREUD - Mx E3VB0067, RCA Victor LPM-3138 - 2’39

9 - GERRY MULLIGAN TENTETTE: ROCKER - Mx 11118, Capitol EAP 1-439 - 2’25

10 - CHET BAKER QUARTET: NO TIES - Unnumbered, Pacific Jazz EP4-8 - 3’00

11- SHORTY ROGERS AND HIS ORCHESTRA: BLUES FOR BRANDO - Mx E3VB0147, RCA Victor EPA-535 - 2’48

12 - ZOOT SIMS QUARTET: BONES FOR ZOOT - Unnumbered, Pacific Jazz PJ19 - 4’20

13 - SHORTY ROGERS AND HIS ORCHESTRA: DOGGIN’ AROUND - Mx E4VB3025, RCA Victor LJM 1004 - 2’35

14 - HOWARD RUMSEY’S LIGHTHOUSE ALL STARS: BAG’S GROOVE - Unnumbered, Contemporary C 2510 - 3’14

15 - LAURINDO ALMEIDA QUARTET: CARINOSO - Mx 318, Pacific Jazz LP 7 - 3’37

16 - THE THREE: ABSTRACT N°1 - Unnumbered, Contemporary C 2516 - 3’34

17 - CHICO HAMILTON QUINTET: FREE FORM - Unnumbered, Pacific Jazz PJ 1209 - 5’ 06

18 - JIMMY GIUFFRE QUARTET: LAZY TONES - Mx 14004, Capitol T634 - 4’10

19 - LYLE MURPHY AND HIS ORCHESTRA: FRANKLY SPEAKING - Unnumbered, Gene Norman LP 9 - 2’53

20 - HOWARD RUMSEY’S LIGHTHOUSE ALL STARS: SAD SACK - Contemporary EP4015 - 5’45

21 - JAZZ STUDIO 3 - JOHN GRAAS: CHARLESTON - Mx L8104, Decca ED 2192 - 2’50

22 - SHORTY ROGERS QUINTET: MARTIANS GO HOME - Mx 1725, Atlantic EP 539 - 7’52

Index

1 - STAN KENTON AND HIS ORCHESTRA: Buddy Childers, Maynard Ferguson, Chico Alvarez, Don Paladino (tp), Shorty Rogers (tp, arr), Milt Bernhart, Harry Betts, Bob Fitzpatrick, Bill Russo (tb), Bert Varsalona (b-tb), Gene Englund (tuba), Bud Shank (as), Art Pepper (as, cl), Bob Cooper (ts), Bart Caldarell(ts, bs), Bob Gioga (bs, b-cl), Stan Kenton (p, dir.), Laurindo Almeida (g), Don Bagley (b), Shelly Manne (dm), Carlos Vidal (cga) - Los Angeles, February 5, 1950 Solos: Rogers (tp), Pepper (as), Ferguson (tp)

2 - JUNE CHRISTY Orchestra conducted by Shorty Rogers: John Graas (frh), Gene Englund (tuba), Art Pepper (as), Bob Cooper, Bud Shank (ts), Bob Gioga (bs), Claude Williamson (p), Don Bagley (b), Shelly Manne (dm), Shorty Rogers (arr, dir) - Hollywood, September 11, 1950

3 - SHORTY ROGERS & HIS GIANTS: Shorty Rogers (tp), John Graas (frh), Gene Englund (tuba), Art Pepper (as), Jimmy Giuffre (ts), Hampton Hawes (p), Don Bagley (b), Shelly Manne (dm) - Los Angeles, September 1951

4 - GERRY MULLIGAN QUARTET: Chet Baker (tp), Gerry Mulligan (bs), Bob Whitlock (b), Chico Hamilton (dm) - Los Angeles, October 15/16, 1952

5 - HOWARD RUMSEY’S LIGHTHOUSE ALL STARS: Shorty Rogers (tp), Milt Bernhart (tb), Jimmy Giuffre, Bob Cooper (ts), Frank Patchen (p), Howard Rumsey (b), Shelly Manne (dm), Carlos Vidal (cga) - Los Angeles, July 22, 1952

6 - ART PEPPER QUARTET: Art Pepper (as), Hampton Hawes (p), Joe Mondragon (b), Larry Bunker (dm) - Los Angeles, February 7, 1952

7 - SHELLY MANNE & HIS MEN: Bob Enevoldsen (v-tb), Art Pepper (as), Bob Cooper (ts), Jimmy Giuffre (bs), Marty Paich (p), Curtis Counce (b), Shelly Manne (dm), Bill Russo (arr) - Hollywood, April 6, 1953

8 - SHORTY ROGERS AND HIS ORCHESTRA: Shorty Rogers, Conrad Gozzo, Maynard Ferguson, Tom Reeves, John Howell (tp), Milt Bernhart, John Halliburton, Harry Betts (tb), John Graas (frh), Gene Englund (tuba), Bud Shank, (as, bs), Art Pepper (as, ts), Jimmy Giuffre (cl, ts), Bob Cooper (bs), Marty Paich (p), Curtis Counce (b), Shelly Manne (dm) - Los Angeles, April 2, 1953 Solos: Rogers (tp), Pepper (ts), Bernhart (tb), Shank (bs)

9 - GERRY MULLIGAN TENTETTE: Chet Baker, Pete Candoli (tp), Bob Enevoldsen (vtb), John Graas (frh), Ray Siegel (tuba), Bud Shank (as), Don Davidson, Gerry Mulligan (bs), Joe Mondragon (b), Chico Hamilton (dm) - Los Angeles, January 29, 1953

10 - CHET BAKER QUARTET: Chet Baker (tp), Russ Freeman p), Carson Smith (b), Larry Bunker (dm) - Los Angeles, October 3, 1953

11 - SHORTY ROGERS AND HIS ORCHESTRA: Shorty Rogers, Conrad Gozzo, Maynard Ferguson, Tom Reeves, Ray Linn (tp), Bob Enevoldsen, Jimmy Knepper, Harry Betts (tb), John Graas (frh), Paul Sarmento (tuba), Herb Geller, Bud Shank (as), Bill Holman, Bill Perkins (ts), Jimmy Giuffre, Bob Cooper (bs), Russ Freeman (p), Joe Mondragon (b), Shelly Manne (dm) - Los Angeles, July 14, 1953 Solo: Perkins (ts)

12- ZOOT SIMS QUARTET: Zoot Sims (ts), Russ Freeman (p), Carson Smith (b), Shelly Manne (dm) - Los Angeles, August 13, 1954

13 - SHORTY ROGERS AND HIS ORCHESTRA: Shorty Rogers, Conrad Gozzo, Maynard Ferguson, Harry Edison, Clyde Raesinger (tp), Milt Bernhart, Bob Enevoldsen, Harry Betts (tb), John Graas (frh), Paul Sarmento (tuba), Herb Geller (as), Bud Shank (as, ts, bs), Zoot Sims, Bob Cooper (ts), Jimmy Giuffre (cl, ts, bs), Marty Paich (p), Curtis Counce (b), Shelly Manne (dm) - Los Angeles, February 2, 1954 Solos: Geller (as), Rogers (tp), Sims (ts)

14 - HOWARD RUMSEY’S LIGHTHOUSE ALL STARS: Bud Shank (fl, alto fl), Bob Cooper (oboe, eng-hrn), Claude Williamson (p), Howard Rumsey (b), Max Roach (dm) - Los Angeles, February 25/26, 1954 15 - LAURINDO ALMEIDA QUARTET: Bud Shank (fl, as), Laurindo Almeida (g), Harry Babasin (b), Roy Harte (dm) - Los Angeles, April 15, 1954

16 - THE THREE: Shorty Rogers (tp), Jimmy Giuffre (ts), Shelly Manne (dm) - Los Angeles, September 10, 1954

17 - CHICO HAMILTON QUINTET: Buddy Collette (fl, cl, as, ts), Fred Katz (cello), Jim Hall (g), Carson Smith (b), Chico Hamilton (dm) - “The Strollers”, Long Beach, CA, August 4, 1955

18 - JIMMY GIUFFRE QUARTET: Jack Sheldon (tp), Jimmy Giuffre (cl), Ralph Peña (b), Artie Anton (dm) - Los Angeles, June 7, 1955

19 - LYLE MURPHY AND HIS ORCHESTRA: Russ Cheever (ss), Frank Morgan (as), Buddy Collette (ts), Bob Gordon (bs), Lyle Murphy (celesta), Buddy Clark (b), Chico Hamilton (dm) - Los Angeles, end November 1954

20 - HOWARD RUMSEY’S LIGHTHOUSE ALL STARS: Conte Candoli (tp), Frank Rosolino (tb), Bud Shank (as), Bob Cooper (ts), Claude Williamson (p), Howard Rumsey (b), Stan Levey (dm) - Los Angeles, December 3, 1954

21 - JAZZ STUDIO 3 / JOHN GRAAS NINETET: Conte Candoli (tp), John Graas (frh), Charlie Mariano (as), Zoot Sims (ts), Jimmy Giuffre (bs), André Previn (p), Howard Roberts (g), Curtis Counce (b), Larry Bunker (dm) - Los Angeles, January 6, 1955.

22 - SHORTY ROGERS QUINTET: Shorty Rogers (tp), Jimmy Giuffre (cl), Pete Jolly (p), Curtis Counce (b), Shelly Manne (dm) - Los Angeles, March 1, 1955

CD 2

1 - CY TOUFF OCTET: TNT - Unnumbered, Pacific Jazz PJ 1211 - 4’55

2 - MARTY PAICH SEPTET: STRANGER IN THE RAIN - Unnumbered, Bethlehem BCP 6039 - 3’42

3 - BOB COOPER OCTET: IT’S DE LOVELY - Mx 13966, Capitol T6513 - 2’15

4 - JACK MONTROSE QUINTET: DOT’S GROOVY - Mx 1641, Atlantic EP 564 - 4’40

5 - DON FAGERQUIST NONETTE: THE MAN I LOVE - Mx 10435, Capitol EAP 2-659 - 3’17

6 - LENNIE NIEHAUS OCTET: CIRCLING THE BLUES - Unnumbered, Contemporary C3503 - 3’16

7 - DAVE PELL OCTET: SUNDAY IN SAVANNAH -Mx 1631, Atlantic LP 1216 - 3’54

8 - DUANE TATRO: MAYBE NEXT YEAR - Unnumbered, Contemporary C3514 - 2’57

9 - BILL USSELTON SEXTET: SWEET SUE - Unnumbered, Kapp KL 1051 - 3’09

10 - JOHNNY MANDEL: THE SEARCH - Unnumbered, World Pacific P 2005 - 4’43

11 - BARNEY KESSEL ORCHESTRA: BLUES FOR A PLAYBOY - Unnumbered, Contemporary C3521 - 3’53

12 - JIMMY GIUFFRE TRIO: THE TRAIN AND THE RIVER - Mx 2284, Atlantic LP 1254 - 3’35

13 - HOAGY CARMICHAEL: NEW ORLEANS - Unnumbered, Pacific Jazz PJ 1223 - 3’55

14 - BUDDY COLLETTE OCTET: CYCLE - Unnumbered, Contemporary C3522 - 2’51

15 - BUD SHANK QUARTET: THEME - Unnumbered, Pacific Jazz PJ 1230 - 3’56

16 - BILL PERKINS OCTET: SONG OF THE ISLANDS - Unnumbered, World Pacific WP 1221- 5’19

17 - MEL TORME: NICE WORK IF YOU CAN GET IT - Unnumbered, Bethlehem BCP 6013- 3’08

18 - TED BROWN SEXTET: BROADWAY - Unnumbered, Vanguard VRS8515- 6’05

19 - SHELLY MANNE & HIS MEN: SOPHISTICATED RABBIT - Unnumbered, Contemporary C3536 - 3’18

20 - SHORTY ROGERS & HIS GIANTS: A GEOPHYSICAL EAR - Mx H2JB3148, RCA Victor LPM1561 - 3’46

Index

1 - CY TOUFF OCTET: Harry Edison, Conrad Gozzo (tp), Cy Touff (b-tp), Richie Kamuca (ts), Matt Utal (as, bs), Russ Freeman (p), Leroy Vinnegar (b), Chuck Flores (dm), Johnny Mandel (arr) - Forum Theater, Los Angeles, December 4, 1955

2 - MARTY PAICH SEPTET: Conte Candoli (tp), Bob Enevoldsen (v-tb), Bob Hardaway (ts), Marty Paich (p), Tony Rizzi (g), Max Bennett (b), Stan Levey (dm) - Hollywood, January 15, 1955

3 - BOB COOPER OCTET: John Graas (frh), Bob Enevoldsen (v-tb), Bud Shank (as, ts), Bob Cooper (ts, arr), Jimmy Giuffre (cl, ts, bs), Claude Williamson (p), Joe Mondragon (b), Shelly Manne (dm) - Hollywood, June 13, 1955

4 - JACK MONTROSE QUINTET: Jack Montrose (ts), Bob Gordon (bs), Paul Moer (p), Red Mitchell (b), Shelly Manne (dm) - Hollywood, May 11, 1955

5 - DON FAGERQUIST NONETTE: Don Fagerquist (tp), Zoot Sims, Dave Pell, Bill Holman (ts), Bob Gordon (bs), Donn Trenner (p), Vernon Polk (g), Buddy Clark (b), Bill Richmond (dm), Wes Hensel (arr) - Hollywood, June 21, 1955

6 - LENNIE NIEHAUS OCTET: Stu Williamson (tp), Bob Enevoldsen (v-tb), Lennie Niehaus (as), Bill Holman (ts), Jimmy Giuffre (bs), Pete Jolly (p), Monty Budwig (b), Shelly Manne (dm) - Hollywood, January 26, 1955

7 - DAVE PELL OCTET: Don Fagerquist (tp), Ray Sims (tb), Dave Pell (ts), Bob Gordon (bs), Donn Trenner (p, celesta), Tony Rizzi (g), Buddy Clark (b), Bill Richmond (dm), Wes Hensel (arr) - Hollywood, April 23, 1955

8 - DUANE TATRO: Stu Williamson (tp), Bob Enevoldsen (v-tb), Vince de Rosa (frh), Lennie Niehaus (as), Bill Holman (ts), Bob Gordon (bs), Ralph Peña (b), Shelly Manne (dm), Duane Tatro (dir, comp, arr) - Los Angeles, April 4, 1955

9 - BILL USSELTON SEXTET: Bob Burgess (tb), Billy Usselton (ts), Abe Aaron (b-cl), Paul Moer (p, arr), Mel Pollan (b), Lloyd Morales (dm) - Hollywood, June 22, 1956

10 - JOHNNY MANDEL (“The James Dean Story” feat. Chet Baker and Bud Shank): Chet Baker, Don Fagerquist, Ray Linn (tp), Milt Bernhart (tb), Bud Shank (as, fl), Charlie Mariano, Herbie Steward (as), Bill Holman, Richie Kamuca (ts), Pepper Adams (bs), Claude Williamson (p), Monty Budwig (b), Mel Lewis (dm), Mike Pacheco (bo), Johnny Mandel (arr) - Los Angeles, November 8, 1956

11 - BARNEY KESSEL ORCHESTRA: Ted Nash (fl, cl), Julie Cobb (oboe, eng-hrn) , George Smith (cl), Howard Terry (bassoon, cl, b-cl), Justin Gordon (cl, b-cl), Jimmy Rowles (p), Barney Kessel (g), Red Mitchell (b), Shelly Manne (dm) - Los Angeles, October 15, 1956

12 - JIMMY GIUFFRE TRIO: Jimmy Giuffre (ts), Jim Hall (g), Ralph Peña (b) - Los Angeles, December 3, 1956

13 - HOAGY CARMICHAEL with the Pacific Jazzmen: Hoagy Carmichael (voc), Harry Edison, Conrad Gozzo (tp), Jimmy Zito (b-tp), Harry Klee (fl), Art Pepper (as), Mort Friedman (ts), Marty Berman (bs, reeds), Jimmy Rowles (p), Al Hendrickson (g), Joe Mondragon (b), Irv Cottler (dm) - Los Angeles, September 10, 1956

14 - BUDDY COLLETTE OCTET: Gerald Wilson (tp), David Wells (b-tp, tb), Buddy Collette (as, ts, fl, cl), William E. Green (as), Jewell Grant (bs), Ernie Freeman (p), Red Callender (b), Max Albright (dm) - Los Angeles, February 13, 1956

15 - BUD SHANK QUARTET: Bud Shank (as), Claude Williamson (p), Don Prell (b), Chuck Flores (dm) - Los Angeles, September 7/8, 1956

16 - BILL PERKINS OCTET: Stu Williamson (tp, v-tb), Carl Fontana (tb), Bud Shank (as), Bill Perkins (ts), Jack Nimitz (bs, b-cl), Russ Freeman (p), Red Mitchell (b), Mel Lewis (dm) - Hollywood, February 9, 1956

17 - MEL TORME acc. by The Marty Paich Dek-Tette: Mel Torme (voc), Pete Candoli, Don Fagerquist (tp), Bob Enevoldsen (v-tb, ts), Vince de Rosa (frh), Albert Pollan (tuba), Herb Geller (as), Jack Montrose (ts), Jack Dulong (bs), Max Bennett (b), Alvin Stoller (dm), Marty Paich (cond., arr) - Hollywood, November 1956

18 - TED BROWN SEXTET: Art Pepper (as), Ted Brown, Warne Marsh (ts), Ronnie Ball (p), Ben Tucker (b) Jeff Morton (dm) - Los Angeles, November 26, 1956

19 - SHELLY MANNE & HIS MEN: Stu Williamson (tp), Charlie Mariano (as), Russ Freeman (b), Monty Budwig (b), Shelly Manne (dm) - Hollywood, February 24, 1958

20 - SHORTY ROGERS & HIS GIANTS: Shorty Rogers (tp, flh), Conte Candoli, Pete Candoli, Conrad Gozzo, Don Fagerquist, Al Porcino (tp), Bob Enevoldsen, Harry Betts, Frank Rosolino, George Roberts (tb), Herb Geller (as, ts), Bill Holman, Richie Kamuca, Jack Montrose (ts), Pepper Adams (bs), Lou Levy (p), Monty Budwig (b), Stan Levey (dm) - Los Angeles, July 15, 1957

Solos: Rogers (tp), Adams (bs), Kamuca (ts), Holman (ts), Kamuca (ts), Holman (ts), Rosolino (tb), Levy (p)

JAZZ WEST COAST FROM HOLLYWOOD TO LOS ANGELES © Frémeaux & Associés(frémeaux, frémaux, frémau, frémaud, frémault, frémo, frémont, fermeaux, fremeaux, fremaux, fremau, fremaud, fremault, fremo, fremont, CD audio, 78 tours, disques anciens, CD à acheter, écouter des vieux enregistrements, albums, rééditions, anthologies ou intégrales sont disponibles sous forme de CD et par téléchargement.)