- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

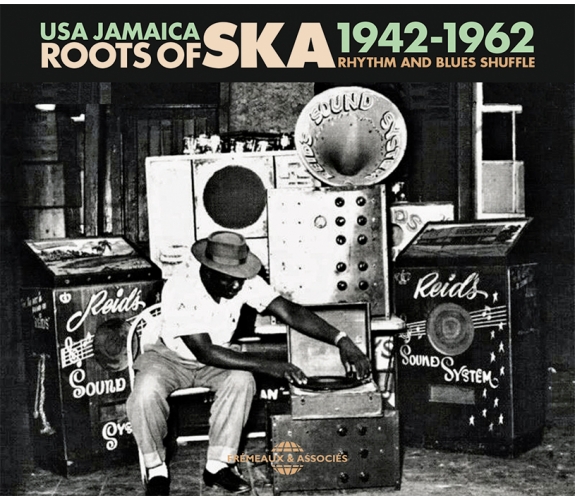

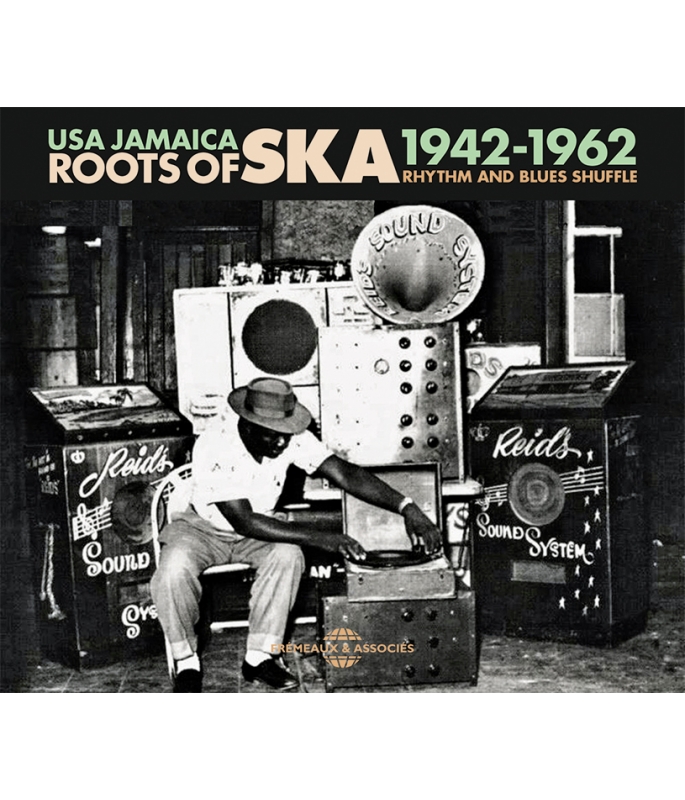

RHYTHM AND BLUES SHUFFLE

Ref.: FA5396

Artistic Direction : BRUNO BLUM

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Total duration of the pack : 3 hours 14 minutes

Nbre. CD : 3

RHYTHM AND BLUES SHUFFLE

RHYTHM AND BLUES SHUFFLE

There are many mysteries surrounding the origins of ska, the famous music-style born in Kingston in 1962, but this Bruno Blum selection puts an end to all the speculation. Ska and its signature offbeat (which later surfaced in reggae) derived from the little-known Ame rican R&B style called shuffle. This anthology has some dazzling illustrations of it, from the obscure, original version of the hit “My Boy Lollipop” to the classic song “Just a Gigolo” - as well as 27 shuffles recorded in Jamaica just before the creation of ska, not to mention some early Bob Marley - this is the original sound of Jamaican dancehall. Patrick FRÉMEAUX

THE KINGSTON RECORDINGS 1951-1958

Lord Kitchener, Mighty Sparrow, Lord Invader, King...

ROOTS OF RASTAFARI 1939 - 1961

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1It 's A Low Down Dirty ShameLouis JordanOllie Shepard00:02:501942

-

2Gi JiveLouis JordanOllie Shepard00:03:021944

-

3Choo Choo Ch BoogieLouis JordanD. Darling00:02:481946

-

4Boogie Woogie Blue PlateLouis JordanJoe Bushkin00:02:471947

-

5Rock BottomGene PhilipsNewman00:02:391947

-

6T-Bone ShuffleT-Bone WalkerAaron Thibaut00:02:591947

-

7Killer DillerGene CoyGene Coy00:02:531948

-

8Reet Petite And GoneLouis JordanS. Lee00:02:441946

-

9Willie MaeProfessor LonghairR. Byrd00:02:501949

-

10Page Boy ShuffleTodd RhodesHenry Glover00:02:401949

-

11Spoon Calls HootieJimmy WitherspoonHenry Glover00:02:431948

-

12If It's So BabyThe RobinsLeonard Terrel00:03:071949

-

13Rockin' At HomeFloyd DixonJay Riggins00:02:521949

-

14Boogie GuitarThe Johnny Otis ShowVeliotes00:02:361949

-

15San Diego BounceHarold LandHarold Land00:02:431949

-

16Ben Fooling AroundProfessor LonghairR. Byrd00:03:031949

-

17Stack A LeeArchibaldGross00:02:311950

-

18Later For The GatorWillis Gator JacksonW. Jackson00:02:421950

-

19Street Walkin' WomanT-Bone WalkerWalker T-Bone00:03:041950

-

20Tend To Do BusinessJames WayneWayne00:02:331951

-

21Train Time BluesRoy BrownR. Brown00:02:501950

-

22No More Doggin'Rosco GordonR. Gordon00:02:581952

-

23My Ding A LingDave BartholomewDave Bartholomew00:02:131952

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Lovers Lane BoogieLittle EstherInconnu00:02:321950

-

2I Found Out My TroublesThe RobinsInconnu00:02:441950

-

3Rockin' The Blues AwayTiny GrimesTiny Grimes00:02:571951

-

4Rock This MorningJesse AllenAllen Jesse Lery00:02:041951

-

5Chicken BluesBill BrownR.L. Williams00:02:501950

-

6Rockin' All DayJimmy McCrackinJ. McCracklin00:02:411950

-

7Guitar ShuffleLowell FulsonLowell Fulson00:02:471951

-

8You'Re Not The OneSmiley LewisSmiley Lewis00:02:301952

-

9Hey BartenderFloyd DixonDoosie Terry00:02:491954

-

10You Upset Me BabyBB KingB.B. King00:03:031954

-

11Hot Little MamaJohnny WatsonJohnny Watson00:03:231955

-

12Gettin' DrunkJohnny WatsonJohnny Watson00:02:431954

-

13Oop ShopShirley Gunter and the QueensShirley Gunter00:02:161954

-

14Hey Hey GirlRosco GordonR. Gordon00:02:381955

-

15Too TiredJohnny WatsonJohnny Watson00:02:441955

-

16My Bop LollipopSpencer BobbySpencer00:02:241956

-

17Just A Gigolo I Aint NobodyLouis PrimaJ. Brammer00:04:441956

-

18Sea CruiseFrancis GuzzoHuey Smith00:02:461959

-

19I Feel GoodErnest RanglinOwen Gray00:02:421959

-

20The JokerAlphonso RolandArthur Reid00:03:091959

-

21GreasyJackie Mc LeanWalter Davis00:07:251959

-

22Duke's CookiesInconnuArthur Reid00:02:271960

-

23Judge NotBob MarleyBob Marley00:02:321962

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Rocking In My FeetOwen GrayOwen Gray00:04:141962

-

2SilkyClue J and his Blues BlastersCuett Johnson00:02:511962

-

3Yard BroomRoland AlphonsoRoland Alphonso00:03:151960

-

4Japanese GirlLloyd ClarkeLloyd Clarke00:02:351962

-

5That Man Is BackDon DrummondDon Drummond00:01:561962

-

6One Cup Of CoffeeBob MarleyC. Gray00:02:401962

-

7Midnight TrackOwen GrayOwen Gray00:02:341962

-

8Me And My Forty FiveEric Marty MorrisOwen Gray00:02:531962

-

9MagicRico RodriguezEmmanuel Rodriguez00:03:011962

-

10Cool SchoolChuck and DoddyChuck Josephs00:02:531957

-

11Bridgeview ShuffleMatador All StarsRoland Alphonso00:02:431957

-

12That's MeTheophilus BeckfordTheophilus Beckford00:02:461957

-

13African ShuffleCount Ossie and the WareikasHarry A Mudie00:02:391961

-

14Over The RiverThe Jiving JuniorsDerrick Harriott00:02:061961

-

15I Love YouWinston & BarbaraWinston Stewart00:02:351962

-

16Luke Lane ShuffleRico RodriguezEmmanuel Rodriguez00:02:551962

-

17Bouncing WomanLaurel Aitken and the blue BeatsEmmanuel Rodriguez00:02:331961

-

18Stew Peas And CornflakesAudrey Adams & Rico RodriguezEmmanuel Rodriguez00:02:251961

-

19RosabelleCornell CampbellCornel Campbell00:02:221956

-

20I Was WrongChuck & BoddyChuck Josephs00:02:121961

-

21What A WorldBusty & CoolA. Robinson00:02:161961

-

22Ten VirginsThe Angelic BrothersJustin Yap00:02:291962

-

23Jamaica BluesAzie LawrenceOssie Lawrence00:02:491961

Roots of ska FA5396

USA JAMAICA

ROOTS OF SKA

1942-1962

RHYTHM AND BLUES SHUFFLE

Jamaica & U.S.A.

Roots of Ska

Rhythm and Blues Shuffle 1942-1962

par Bruno Blum

— Vous dansiez sur quoi ?

— Des choses folles, c’était avant le rock and roll, j’adorais, c’était le boogie-woogie et le blues, et le jazz, on aimait les danses vraiment très sauvages. Et puis ensuite j’ai voulu me mettre à la musique, et chanter aussi.

[Lee « Scratch » Perry à l’auteur, 1994. La future vedette du reggae Lee « Scratch » Perry a fait ses débuts en tant qu’assistant de Clement « Coxsone » Dodd en 1961.]

À la lisière du jazz et du rock, le style shuffle est le produit d’une culture profondément afro-américaine axée sur la danse. Ce style est mal connu, car il a été peu exposé au grand public blanc de son époque. Il n’en comprend pas moins quelques-uns des trésors du rhythm and blues enregistré au États-Unis et en Jamaïque. Le ska, puis le reggae, en sont directement dérivés.

R&B

En Jamaïque les premiers 45 tours de rhythm and blues n’ont été mis en vente qu’en 1959. Cette petite production de disques naissante ne peut évidemment pas se mesurer avec vingt ans de l’immense patrimoine états-unien, d’où sont extraits plusieurs chefs-d’œuvre inclus ici. Malgré tout son talent, la petite Jamaïque ne pouvait rivaliser avec des monstres sacrés des années 1940-1950 comme Professor Longhair, Rosco Gordon, Louis Jordan, T-Bone Walker, Johnny Otis, Little Esther, Johnny « Guitar » Watson ou B.B. King. Néanmoins dès le début, le son jamaïcain avait des atouts sérieux. L’indéniable originalité du shuffle de l’île doit beaucoup à un guitariste qui fera une carrière internationale dans le mento, le jazz, le R&B, le ska et le reggae, Ernest Ranglin1. Le saxophoniste Roland Alphonso ou le tromboniste Don Drummond, futurs piliers des Skatalites, n’avaient rien à envier non plus aux meilleurs instrumentistes américains. Les enregistrements fondateurs des chanteurs Owen Gray, Laurel Aitken, Theophilus Beckford, Bob Marley ou Derrick Morgan pour ne citer qu’eux, sont restés dans la légende du ska et du reggae. Ces genres musicaux ont toujours entretenu des liens très proches avec le R&B, la soul, le gospel, le funk, le rap. À leur échelle, la direction artistique de Clement « Coxsone » Dodd (Studio One), Prince Buster (Prince Buster), Duke Reid (Treasure Isle) et Chris Blackwell (R&B/Island), les quatre producteurs à l’origine du ska, du rocksteady et du reggae, peut tenir la dragée haute aux plus grands noms américains comme Nesuhi et Ahmet Ertegun (Atlantic), Julius Bihari (Modern/Meteor), Bumps Blackwell (Specialty), Sam Phillips (Sun), Syd Nathan (King/Federal) ou Berry Gordy (Motown), qui les inspirèrent.

One Step Beyond

En 1979, quelques succès anglais comme le Gangsters des Specials ou Wrong’em Boyo (reprise d’un rocksteady des Rulers par The Clash) et One Step Beyond (reprise d’un instrumental de Prince Buster par Madness) ont lancé une mode étiquetée « ska ». Depuis, ce genre n’a cessé de faire des émules dans le monde : Tokyo Ska Paradise Orchestra, Jim Murple Memorial, Toasters, etc. Les vêtements à carreaux noirs et blancs et les disques de la marque londonienne 2-Tone ont été en vogue pendant quelques mois en 1979-1981 avant de disparaître brusquement. Ils ont fait place au renouveau du rockabilly lancé par les Stray Cats et à la pop électronique qui domina le début de la décennie 1980 en Grande-Bretagne. Mais cette mode « ska » éphémère a beaucoup participé à faire découvrir le ska originel, une musique d’une grande richesse née dans un studio de Kingston vers la fin de l’année 1961. Nombre de musiciens jamaïcains ont depuis tenté de s’attribuer la paternité du ska. Beaucoup d’inexactitudes et de mensonges sur sa naissance ont été publiés au fil des ans. Ce florilège de morceaux empruntés aux patrimoines états-unien et jamaïcain contient du rhythm and blues enregistré avant le développement du ska. Il mettra, nous l’espérons, un point final aux spéculations sur les véritables origines de ce genre musical. Espérons qu’il fera aussi découvrir quelques morceaux aussi remarquables que méconnus, et mieux comprendre cette filiation des spirituals au jazz, du boogie woogie au rock and roll, du swing au jump blues et du shuffle au ska. Voici leur histoire.

Dance Hall

Après la violente crise économique de 1929, le blues ne se vendait plus. Déjà marginal, il est passé de mode. Après une phase de tâtonnements, la vague du swing (un rythme utilisé par des jazzmen comme Duke Ellington) a commencé à toucher le grand public aux États-Unis. En 1935, le très dansant « King Porter Stomp »2 de Benny Goodman, un clarinettiste virtuose, juif new-yorkais (il fut le premier Blanc à engager des Noirs — Lionel Hampton et Teddy Wilson — dans son groupe) est véritablement parvenu à ouvrir le grand public au jazz. Cette musique était alors très rythmée, dansante et riche en improvisations libres. C’est ainsi que la dance music fit en quelque sorte son entrée dans le grand public sous le nom de « swing » (balancement).

Les musiques afro-américaines, qui stimulent autant le corps que l’esprit, étaient jusque-là tenues à distance par l’essentiel du public blanc, très majoritaire. Schématiquement, les traditions protestantes et catholiques considéraient depuis des siècles que la musique devait impérativement élever l’esprit vers Dieu. La musique devait donc s’adresser à la tête ; en revanche, le corps était en quelque sorte jugé être l’instrument du diable : gourmandise, sexe, désirs, etc. En dehors d’une élite éclairée, le jazz et sa danse libre étaient perçus comme des curiosités nègres, vulgaires, lubriques et vaguement diaboliques — une forme de péché, de plaisir interdit, ou réservé aux gigolos et filles de mauvaise vie. Jusque-là, cette musique incitant à des mouvements décomplexés était principalement cantonnée à des dancings urbains fréquentés par des afro-américains : les dance halls. La communauté jamaïcaine était déjà importante à New York. Comme le raconte Mezz Mezzrow dans son autobiographie, on importait de la marijuana jamaïcaine très prisée par les musiciens de jazz — y compris certains entendus ici. Un saxophoniste jamaïcain comme Lord Fly joua une bonne partie de sa carrière à New York avant de devenir chanteur de calypso. Il existait aussi quelques cabarets chic comme le Cotton Club3, interdit au public noir et fréquenté par des bourgeois venus s’encanailler dans le quartier afro de New York (on pouvait y assister à de véritables spectacles avec danseurs et musiciens). Le jazz atteignait des sommets de qualité dans les meilleurs dancings appréciés par les Afro-américains, comme le pres-tigieux Savoy Ballroom4 de Harlem5. Puis pendant la Deuxième Guerre Mondiale, le jazz dansant connut un âge d’or à Kansas City où la pègre était particu-lièrement puissante et pouvait s’offrir de grands orchestres comme ceux de Big Joe Turner ou Jay McShann, entendu ici accompagnant le blues shouter6(capable de chanter sans micro devant un orchestre) Jimmy Witherspoon.

Ces haut lieux de la danse proposaient des concours de lindy hop7, danses libres, spontanées et acrobatiques (on dirait aujourd’hui le « rock and roll acrobatique »), frénétiques, voire érotiques : pour une grande partie de la majorité blanche — et un pourcentage important des Noirs —, c’était le comble de la décadence. De fabuleux orchestres y jouaient sur un tempo moyen favorisant la danse, appelé swing. Les disques de Jimmy Lunceford, Lucky Millinder, Count Basie ou Duke Ellington se vendaient de mieux en mieux. En pleine ségrégation raciale, des formations blanches comme celles de Paul Whiteman, Gene Krupa, Frank Sinatra8 ou Glenn Miller (qui dirigeait un orchestre aux arrangements écrits, sans improvisations) répondaient à la demande croissante de ces musiques « swing » et attiraient une part importante de ce nouveau marché de la « dance music » de l’époque. Une fois la paix revenue en 1945, le grand public américain a continué à danser au son de musiques populaires aux racines afro-américaines mieux intégrées. Elles étaient souvent interprétées par des chansonniers blancs qui osaient s’adapter aux musiques afro en vogue comme la rumba, le boogie-woogie ou le calypso des Andrew Sisters9, le swing de Sinatra — et bientôt le rock d’Elvis Presley10. C’est d’ailleurs ce qui arrivera également au Just a Gigolo/I Ain’t Got Nobody de Louis Prima, un musicien blanc de jazz, originaire de la Nouvelle-Orléans, qui en 1957 réussira l’un des rares tubes « grand public » (pop) du shuffle. Ce succès lui ouvrira les portes des studios de Walt Disney ; il prêtera en 1967 sa voix scat au roi des singes du dessin animé Le Livre de la Jungle. Deux autres chanteurs blancs figurent sur cette anthologie : Barbie Gaye et Frankie Ford, dont le gros succès Sea Cruise en 1959 sera dû à l’excellent accompagnement d’un Noir, Huey « Piano » Smith, dont l’irrésistible arran-gement est un pur produit du shuffle afro-américain de la Nouvelle-Orléans : dans le contexte de la mode du « rock » blanc dominée par Elvis Presley, le phénotype blanc de Frankie Ford était plus facile à promouvoir dans les médias que celui plus sombre de Piano Smith.

Après la guerre et l’âge d’or de Kansas City, il était devenu difficile de rentabiliser les grandes formations de jazz passées de mode. Menée par Charlie Parker11 à partir de 1945, l’irruption du jazz moderne privilégiait les petits groupes, les « combos ». Le nouveau jazz bebop était souvent joué sur des tempos rapides pas toujours appréciés par les danseurs — ni le grand public. Il rendait tout de même le son de Count Basie ou Louis Armstrong obsolète. Qu’allaient devenir les danseurs ? Et les musiciens des orchestres de jazz ? De leur côté, les musiciens blancs se partageaient l’essentiel du marché avec diverses musiques populaires, du gospel blanc d’un Stuart Hamblen à la variété radiophonique de Jane Froman, Dean Martin ou Bing Crosby. Sans oublier le bluegrass, la country music12 et son style honky tonk13. La country music était d’ailleurs appréciée en Jamaïque : le deuxième single du débutant Bob Marley, One Cup of Coffee est une reprise d’un succès country de Claude Gray de 1961. Inversement, certains Blancs états-uniens écoutaient aussi des musiques influencées par les sons afro-américains : musiques latines, swing, western swing14, country boogie15…

Jump Blues

Pour danser, le jeune public afro-américain se tourna vers le son à la mode dans l’après-guerre : le jump blues16. Orientée vers la danse, cette branche du rhythm and blues naissant était interprétée par des orchestres où les instruments à vent tenaient encore une grande place. Les musiciens étaient de haut niveau mais souvent peu nombreux (plus de grandes formations, ou bien moins grandes), comme chez le maître du genre, Louis Jordan. Ils jouaient parfois des tempos (ou BPM !) très rapides marqués par l’influent jazz bebop, mais surtout, dans la continuité de la période swing d’avant-guerre, des tempos incitant à danser. À la Nouvelle-Orléans, les pianistes de blues Champion Jack Dupree, Archibald, Professor Longhair (qui joue ici la basse à la main gauche sur le piano) et son disciple Rosco Gordon à Memphis comptaient parmi les nombreux gardiens d’une tradition pianistique cousine du boogie woogie. Bien que les premiers enregistrements de « ’Fess’ » Longhair ne datent que de 1949 (donc après les premiers disques de shuffle de Louis Jordan), il a vraisemblablement été l’un des passeurs, des « professeurs » du style shuffle qui conquit les Afro-américains des États-Unis et de Jamaïque. Certaines mélodies de Rosco Gordon (comme ici Hey Hey Girl en 1955) semblent directement influencées par Professor Longhair.

« Il y a avait plein de pianistes qui jouaient ça. Il est impossible de savoir de qui ça vient vraiment.»

— Jon Cleary, entretien avec l’auteur, 2012.

Quand les orchestres voulaient faire danser la salle, leur meilleure carte était ce rythme shuffle, objet de cet album. Il était au répertoire de musiciens de jazz comme Louis Jordan and his Tympani Five, qui comptent parmi les pionniers de ce style avec des tubes exquis comme G.I. Jive. Sortie en 1944, cette reprise de Johnny Mercer fait allusion au jargon (et aux grades) des soldats américains partis au front en Europe :

PSC the CPL the SGT the LT/CP the whole deal the MP makes you do café/It’s the G.I. jive/Man alive/It starts with the bugle blowing reveille over your head

Dans le sillage du populaire Louis Jordan, l’efficacité du shuffle incita toutes sortes de formations de R&B à enregistrer ce type de rythmique, comme Roy Brown (Train Time Blues), un chanteur de gospel qui devint l’un des tout premiers rockers, compositeur de « Good Rockin’ Tonight » entre autres. Le groupe légendaire du trompettiste Dave Bartholomew accompagnait presque tous les artistes (Little Richard et Fats Domino inclus) au studio de Cosimo Matassa à la Nouvelle-Orléans. Bartholomew interprète ici lui-même sa composition shuffle sur le thème du pénis, My Ding-a-Ling, qui en 1972 donnera à Chuck Berry le plus gros succès de sa carrière. James « Wee Willie » Wayne, immortel créateur de « Junco Partner » (un rhythm and blues sur le thème de l’héroïne qui sera enregistré en version reggae en Jamaïque par The Clash en 1980) a enregistré son premier disque et succès Tend to do Business (« occupe-toi de tes affaires ») sur ce rythme.

Les instruments à vent sont très présents dans le rhythm and blues américain des années 1940. Mais c’est aussi à cette époque que les solistes de la guitare électrique se sont imposés sous l’influence centrale de T-Bone Walker. Son disciple B.B. King enchaîna une série de succès dont l’implacable You Upset Me, Baby (n°1 R&B en 1954), un pur shuffle. Armé de sa guitare à quatre cordes, Tiny Grimes (qui enregistra avec Charlie Parker, Art Tatum et d’autres géants du jazz), Clarence « Gatemouth » Brown (« Just Got Lucky » 1949) et Lowell Fulson comptent parmi ceux qui, comme l’extraordinaire Johnny « Guitar » Watson ont posé les jalons de la guitare électrique dans le blues et le rock.

It was rocking, it was rocking/You’d never seen such scuffling, shuffling and rocking ‘til the break of dawn/It was rocking, it was rocking

— Louis Jordan, “Saturday Night Fish Fry”, 1949

En Jamaïque, le guitariste de jazz Ernest Ranglin pérennisera sa contribution au rock jamaïcain

avec quelques titres de blues shuffle comme Easy Snappin’, Jack and Jill Shuffle ou ici That’s Me de Theophilus Beckford.

De grands orchestres américains de rhythm and blues comme le Johnny Otis Show (qui accompagne ici Pete Lewis, Little Esther Philips et les Robins) ont également adopté ce rythme, mais de petites formations aussi. À vrai dire, le jump blues et sa branche shuffle sont tout simplement la première véritable forme prise par qu’on appellait dans les années 1940 le rhythm and blues ou le rock and roll — comme en attestent ici les titres Rockin’ at Home, Rock Bottom, Rockin’ the Blues Away, Rock This Morning, Rockin’ All Day ou Rocking in my Feet.

« En fait, tous les éléments caractéristiques du rock étaient déjà présents dans le « jazz » des années 1940, à commencer par la magie du « swing », du « groove » — du « rock » ou balancement. Dans le jazz ? Ou plutôt dans la musique de « rythme ». Pour le grand public (entendez « public blanc »), la distinction entre blues, rhythm and blues, jump blues, boogie woogie, jazz et swing n’existait pas vraiment. […] En vérité, dans sa forme originelle dans les années 1940, le rock à succès est principalement incarné parce que l’on appelle communément le jump blues, caractérisé par des compositions de rock interprétées par un orchestre de jazz/rhythm and blues conçu pour la danse. »

— Le Dictionnaire du rock, notice « Jazz », édition de 201317.

Le shuffle dansant des pionniers de la guitare électrique était également présent sous formes de titres instrumentaux entre jazz et R&B : T-Bone Walker (T-Bone Shuffle), Lowell Fulson (Guitar Shuffle), Tiny Grimes and his Rocking Highlanders (Rockin’ the Blues Away). Bien que moins connu, sur Silky et That’s Me le guitariste jamaïcain Ernest Ranglin rivalise ici de talent avec ses célèbres pairs américains. Les musiques afro-américaines ont beaucoup circulé à travers les États-Unis et les Antilles. Le merengue de Saint-Domingue18 a conquis le Venezuela, Haïti et d’autres îles ; les musiques cubaines et brésiliennes se sont répandues dans nombre de pays et ont longtemps fusionné avec le jazz « latin » d’après-guerre ; le calypso trinidadien19 et le mento jamaïcain ont conquis les Antilles jusqu’aux Bermudes20 et ont connu un succès mondial avec Harry Belafonte21. De la même manière, le rhythm and blues du sud des États-Unis a trouvé sa place en Jamaïque : entendu à la radio américaine et très apprécié sur les dance halls de l’île, à partir de 1956 le shuffle sera enregistré dans les premiers studios de Kingston, à deux heures d’avion de Miami. L’album Jamaica - Rhythm & Blues 1956-1961 paru dans cette collection contient une quarantaine de shuffles jamaïcains. Il est complémentaire à cette anthologie. Son livret relate en détail l’histoire du R&B jamaïcain et des sound systems où les deejays, animateurs équipés de micros, ont fait découvrir le shuffle aux danseurs des quartiers pauvres de l’île.

Jamaïque

Tout un pan de musiciens antillais a surgi et contribué à ce qu’on appelle le jazz. Ils descendaient virtuellement tous de la véritable scène africaine.

— Duke Ellington22

À partir de 1954 environ (probablement un peu plus tôt), quelques cabarets comme le Glass Bucket de Kingston accueillaient des musiciens de jazz locaux prêts à jouer dans le style R&B. Mais trop pauvres, les Jamaï-cains du peuple n’a-vaient pas accès à ces établissements. Ils ne disposaient pas non plus de dance halls po-pulaires, ces dancings bon marché où se produisaient les orchestres de jazz ou de rhythm and blues aux États-Unis. Dans les ghettos miséreux où la demande de musique était très forte, il fallait se contenter de disques américains d’abord importés par des soldats pendant la guerre, puis par des disc jockeys à la page. Les blues parties étaient organisées par des équipes propriétaires de sonos mobiles, qu’ils louaient à des bars où le shuffle et le swing régnaient. L’histoire de ces sound systems jamaïcains, qui bouleverseront bientôt l’histoire de la musique populaire, est racontée plus en détail dans le livret de notre album Jamaica - Rhythm and Blues 1956-1961 (FA 5358).

Nombre de musiciens américains, comme ici Harold Land, les saxophonistes Todd Rhodes (Page Boy Shuffle) ou Willis « Gator » Jackson ont gravé des instrumentaux shuffle dominés par les instruments à vent. À partir de 1950 environ, le tube Later for the Gator de « Gator » Jackson est devenu le « thème » avec lequel Clement « Coxsone » Dodd ouvrait et achevait ses soirées dansantes à Kingston. Coxsone le rebaptisa « Coxsone Hop » pour que ses concurrents ne puissent pas retrouver le disque, longtemps resté l’exclusivité de son sound system Downbeat. Il cacha aussi le véritable nom du San Diego Bounce d’Harold Land, longtemps connu en Jamaïque sous le nom de « Coxsone Shuffle ». Coxsone deviendra vite le plus important producteur de rhythm and blues de l’île, puis de ska à partir de 1962 et plus tard de rocksteady et de reggae. Pour ses premières séances d’enregistrement en 1956, il réunit Clue J and the Blues Blasters, la crème des jazzmen de l’île à qui il demanda de copier avec soin le son du shuffle américain - tout en y mettant leur grain de sel. Le Killer Diller de Gene Coy (1948) sera par exemple retravaillé par ses Blues Blasters, qui replaceront une partie du thème dans leur instrumental « Milk Lane Hop », un shuffle de 1961. « Killer Diller » contient aussi un passage parlé rappelant le style des deejays jamaïcains animant les sound systems au micro. Il est certain que ce morceau influent a contribué à inspirer les deejays de l’île, qui devinrent les authentiques pionniers du rap avant de l’exporter à New York dans les années 1970 — avec le succès qu’on sait23.

La formule instrumentale était appréciée en Jamaïque. Le jazz y était particulièrement populaire dans les années 1950 — et ce dans toute la population, contrairement aux États-Unis où la ségrégation raciale était implacable et où la majorité blanche ignorait en bonne partie cette musique. Les premiers enregistrements de rhythm and blues jamaïcain comprennent donc beaucoup d’instrumentaux shuffle marqués par le jazz comme le manifeste afro rasta African Shuffle de Count Ossie and the Wareikas et Joker ou Yard Broom avec le saxophoniste Roland Alphonso. Les instrumentaux Stew Peas and Cornflakes, Silky ou The Man Is Back du grand tromboniste Don Drummond sont des exemples de cette influ-ence décisive sur les productions de Coxsone Dodd. Les Luke Lane Shuffle et Duke’s Cookies avec Rico Rodriguez (tromboniste, ancien élève de Drummond), ont eux été produits par le grand rival de Coxsone, Duke Reid. Duke Reid dominait les sound systems pendant cette période et le prestigieux nom Duke Reid’s Group apparaissait sur plusieurs disques.

Influencés par le style des jubilee groups du gospel, nombre de groupes de rhythm and blues américain pratiquaient aussi la difficile discipline des harmonies vocales. On peut en déguster quelques splendides exemples ici avec les titres des Robins, de Little Esther et de Bill Brown avec Billy Ward and His Dominoes — sans oublier le très repris Oop Shoop de Shirley Gunter and the Queens, dans ce que l’on appellera plus tard le style doo wop. Très présent aux États-Unis comme en Jamaïque, le gospel noir et ses harmonies « barber shop » ou « jubilee » a fortement marqué le rhythm and blues. Les groupes vocaux américains étaient particulièrement appréciés par le public jamaïcain. On peut apprécier cette influence sur le volet jamaïcain de ce coffret (fin du disque 2 et disque 3) : Chuck & Dobby, Busty & Cool et Winston & Barbara ont notamment été marqués par Shirley and Lee, célèbre duo de la Nouvelle Orléans. Le ska viendra plus tard renforcer cette tendance avec de grands groupes vocaux comme les Clarendonians, les Gaylads avec Dobby Dobson, Higgs and Wilson, les Techniques, les Wailers, etc.

Laurel Aitken, première vedette jamaïcaine du rhythm and blues, a aussi enregistré le Hey Bartender24 de Floyd Dixon entendu ici (également repris depuis par les Blues Brothers). No More Doggin’, premier shuffle enregistré par Rosco Gordon en 1952, a été un gros succès aux États-Unis. Le pianiste jamaïcain Theophilus Beckford était un admirateur de Rosco, dont il copia le style, comme l’on peut l’entendre ici sur That’s Me. Principal pianiste de Clue J and his Blues Blasters, Theo joua la croche ou «skank» au piano sur nombre des premiers disques de R&B jamaïcain (voir discographie). Son influence sur le ska — et le reggae à venir — ne peut donc pas être surestimée.

Shuffle ou Ska ?

Le ska a surgi quelques mois avant l’indépendance (août 1962) de la Jamaïque. Il a connu son âge d’or entre 1962 et 1965, puis il est passé de mode. Il s’est vite métamorphosé en reggae, un genre d’une importance et d’une portée considérables. À son tour le reggae a connu différentes mutations. Il est devenu depuis l’un des symboles de la « world music » reflet de la société multiculturelle. Le plus célèbre des musiciens de reggae, Bob Marley, a enregistré de nombreux skas au début de sa carrière. Mais son premier enregistrement Judge Not (1962) n’était pas encore du ska. C’est un morceau au rythme de batterie caractéristique du shuffle venu des États-Unis. Il existe des liens entre le shuffle et des formes de musique jamaïcaine indigène comme les negro spirituals revivalistes25, le gospel, le mento26 (le fifre entendu sur Judge Not en est un bon exemple), le jazz3, le nyabinghi27, mais le ska proprement dit est presque à 90 % un dérivé du style shuffle américain imprégné de jazz et de jump blues. En Jamaïque, où l’on ne pouvait pas écouter de musique locale à la radio nationale, et où les pistes de danse étaient le média de la musique populaire, la culture du disc jockey était déterminante.

Le shuffle eut aussi un impact direct sur le premier succès international du ska

Marqué par le pionnier de la guitare électrique jazz, Charlie Christian, Ernest Ranglin a profité des leçons du Jamaïcain Cecil Houdini avant de passer professionnel à l’âge de seize ans dans l’orchestre de jazz de Val Bennett, puis celui d’Eric Dean, la meilleure formation du genre en Jamaïque. Il sera l’un des principaux acteurs des premières séances d’enregistrement du mento, du shuffle jamaïcain (dès 1956) puis du ska. Il réalisera notamment l’enregistrement d’une version ska de My Boy Lollipop par Millie Small, un gros succès international vendu à six millions d’exemplaires qui en 1964 feront la fortune de leur producteur Chris Blackwell. Avec l’argent gagné, investi dans ses disques Island, Blackwell publiera ensuite du shuffle jamaïcain et du ska en Grande-Bretagne puis Steve Winwood, Cat Stevens, King Crimson, Toots, Bob Marley, U2, Grace Jones et bien d’autres. Méconnue, la version originale de My Boy Lollipop par Barbie Gaye, un shuffle américain gravé huit ans plus tôt, est incluse ici et ressemble à s’y méprendre à celle de Millie. Barbie Gaye avait quinze ans quand elle a enregistré ce morceau écrit par Robert Spencer des Cadillacs. Son disque était souvent joué par le DJ Alan Freed. Il eut suffisamment de succès pour assurer à Barbie une prestation en première partie de Little Richard dans le spectacle de noël de Freed en 1956.

Quelle est la différence entre shuffle et ska ? Principalement la rythmique, puisque la présence des instruments à vent, des voix marquées par le gospel, des guitares bluesy et jazzy sont à peu de chose près les mêmes. Le rhythm and blues « shuffle » est principalement caractérisé par une batterie « swing » et une partie de basse « walking bass » (ambulante) jouée à la noire, pentatonique. On la retrouve dès 1942 sur le It’s a Low-Down Dirty Shame de Louis Jordan and his Tympany Five. Le shuffle états-unien comme jamaïcain ne déviera pas de cette formule et basculera vers le ska à l’hiver 1962. Certains morceaux sont à la charnière des deux rythmes, comme One Cup of Coffee. La création du rythme ska par le batteur jamaïcain Lloyd Knibb s’est produite fin 1961 ou début 1962 :

« Tout a commencé avec le rhythm and blues. Puis la musique a changé. Coxsone m’a appelé au studio un jour et m’a dit « Lloydie je veux changer le rythme tu sais ? Trouve un beat. » D’accord, alors je suis allé au studio et j’ai essayé un rythme vraiment différent. J’ai commencé par le style Burru [issu du rythme ntoré, tambours d’origine est-congolaise, NDT] et je me suis retrouvé sur le deuxième et le quatrième temps tout au fond du temps, et on a mis le reste de ce qu’on avait là-dedans. Le deuxième et le quatrième temps étaient le rythme le plus direct. Coxson a dit « yeah » et c’était fini. Du rock and roll et rhythm and blues on est passé au ska. Tout le monde a accroché à ce rythme. Et tout le monde l’a enregistré, Bob Marley, One Cup of Coffee je me souviens de celui-là. Owen Gray, Delroy Wilson, Alton Ellis, cite-les tous, ils sont tous passés entre nos mains. »28

Origines du shuffle

La batterie shuffle est jouée dans un style dérivé du piano boogie woogie ; On peut parfois entendre ce ta-ta/ta-ta/ta-ta (bien en évidence ici sur T-Bone Shuffle de T-Bone Walker ou Jamaica Blues d’Azie Lawrence), qui était parfois joué en accords par la main gauche de grands pianistes de boogie des années 1930 comme Jimmy Yancey, Willie « The Lion » Smith, Meade « Lux » Lewis, Albert Ammons ou Memphis Slim. Joué à la batterie, ce rythme ternaire basique combiné à une « walking bass » (jouée sur toutes les noires) est à la racine du jazz swing, du jazz moderne comme d’un « rock » tel le Rock This Morning de Jesse Allen & James Gilchrist. Il plonge peut-être ses racines dans la musique des Bambaras de la Nouvelle-Orléans ou un rythme congolais, le ntoré30 que l’on entendait vraisemblablement lors des fameuses bamboulas de Congo Square à la Nouvelle-Orléans au XIXème siècle : beaucoup de Congolais ont été déportés en Louisiane et en Jamaïque peu avant les abolitions de l’esclavage. La culture des Bantous du Congo a ainsi marqué la région des Caraïbes29. Le rythme ntoré congolais se retrouve profondément ancré dans la musique afro-jamaïcaine, qui présente de grandes affinités naturelles avec le swing. On le retrouve notamment dans les tambours Burru, les cérémonies revivalistes kumina et le nyabinghi des Rastas, qui ont toujours visé à préserver la mémoire de l’esclavage et à valoriser leur identité africaine. On peut écouter un rare mélange de pur shuffle avec ces tambours rituels rastas sur le African Shuffle des légendaires Count Ossie and the Wareikas30. Il est également présent dans le mento traditionnel jamaïcain31. Voilà pour la partie basse-batterie. Pour les autres éléments musicaux, dans le rhythm and blues entendu sur cet album en plus de la « walking bass », la spécificité du « shuffle » est que la main droite du piano et parfois la guitare électrique jouent de brefs accords à contretemps, c’est à dire sur le « et » du 1-et-2-et-3-et-4-et… Cet usage s’est développé dans le shuffle des années 1940. En Jamaïque elle est appelée le « skank », ce qui en patois local signifie « danse » et donnera son nom au ska en 1962 (on la retrouvera bientôt au premier plan dans le reggae, qui naîtra en 1968). Un exemple limpide peut en être écouté chez le premier géant du rhythm and blues, l’un des grands créateurs du rock and roll et du jazz, l’immense Louis Jordan qui dès 1942 gravait It’s a Low-Down Dirty Shame dans ce style shuffle très dansant. Le chanteur et saxophoniste cherchait le succès. Il est devenu extrêmement populaire et influent dans la communauté afro-américaine de l’après-guerre. Jordan chantait de petites histoires remarquablement écrites, souvent drôles, sur une musique qu’il voulait dansante, accrocheuse, dans l’esprit du swing décrit plus haut. C’est ainsi qu’il a gravé des titres invincibles comme Choo Choo Ch’Boogie (1946) ou Boogie Woogie Blue Plate (1947). La puissance d’entraînement du shuffle (l’afterbeat ou offbeat) est totale. En pleine ségrégation raciale, la magie du swing parvenait à séduire le grand public blanc. L’accent « shuffle » marqué sur le contretemps décuplait encore l’envie de danser. Pour le poète du dub, vedette du reggae et sociologue Linton Kwesi Johnson,

« Tu le retrouves dans toutes nos musiques, le reggae, le calypso, le mento, la musique de la Martinique, de la Guadeloupe, tu le retrouves dans le hi-life, le merengue. De plus cette attirance pour l’« afterbeat » se retrouve dans les églises avec les rythmes de tambourins, les claquements de mains, etc. »

— Linton Kwesi Johnson, à l’auteur32.

En effet dans les cultures afro-américaines, les spiritualités africaines se sont mélangées aux religions bibliques des églises méthodistes, pentecôtistes, baptistes, apostoliques, etc.33

« On ne chantait que des spirituals pendant les ring shouts et le style de la danse était strictement réglementé. On ne devait jamais croiser les pieds, ce qui aurait immédiatement pu faire penser à une danse profane. Pour les croyants les plus stricts, le pied ne devait pour ainsi dire pas quitter le sol et la progression n’était obtenue que par le shuffle, ce pas glissé qui, beaucoup plus tard, devait devenir un pas de danse pratiqué avec virtuosité par les danseurs noirs34. »

Aux États-Unis comme à la proche Jamaïque, ces intenses religions « revivalistes » ont incorporé différents éléments de rituels africains. Sur le continent nord-américain ils étaient présents dès le XVIIIème siècle dans les cercles où les negro spirituals libéraient l’âme.

« À l›origine, le shuffle est un pas frotté (pied à plat) en usage dans les ring shouts des esclaves. Ensuite, à l’époque des minstrels, on trouve le soft-shoe shuffle qui donna lieu à plusieurs variantes. Plus tard, ce pas fut sans doute transposé à l’orchestre et donna naissance à un rythme spécial. Ce rythme est celui produit dans le boogie-woogie par la main gauche à raison de huit basses par mesure (eight-to-the-bar), pour schématiser : huit croches inégales jouées « ternaires ».

— Philippe Baudoin, le Dictionnaire du jazz35.

Ainsi, des tambourins aux claquements de mains baptistes, des glissements de pied rythmés aux danseurs de claquettes du jazz jusqu’au rhythm and blues entendu ici, la pratique du shuffle sous ses diverses formes est l’un des nombreux points communs où se rejoignent les traditions créoles afro-américaines et afro-caribéennes. La symbolique des mouvements de pied dans les cérémonies revivalistes jamaïcaines est significativement évoquée dans le livret du volume Jamaica - Folk - Trance - Possession 1939 - 1961 (FA5384) dans cette collection. Sans doute du fait de son utilisation dans les pas de danse des rites religieux, à l’origine le shuffle porte en lui une idée de comportement respectueux, bon, honnête, conscient, spirituel. Ce terme est par exemple utilisé pour décrire le geste de battre un jeu de cartes, où le frottement des cartes en rythme doit être réalisé sans tricherie et remettre le résultat au hasard — aux esprits. Un tricheur peut frauder en battant les cartes, comme il est fait allusion ici :

Why you play the bad card/Now we caught you off guard/Natty dread want to shuffle/Not looking for nothing to scuffle now

— Bob Marley, Who Colt The Game, 1977.

Les églises baptistes (protestantes) étaient très majoritaires dans la communauté afro-américaine des États-Unis dans les années 1940-1960. Pour les baptistes, qui tapent dans leurs mains sur le contretemps « shuffle » dans leurs cérémonies, la danse proprement dite est exclue. Elle a valeur d’anathème. Ce goût très prononcé pour la danse en Jamaïque — et le shuffle en particulier — s’explique sans doute par la forte présence de l’église pentecôtiste, très majoritaire dans l’île, qui encourage la danse et l’expression corporelle — tandis que les baptistes (majoritaires chez les Afro-américains aux États-Unis) sont nettement plus frileux dans ce domaine. Le « shuffle » des pieds est monnaie courante dans les cérémonies pentecôtistes et revivalistes. C’est ce contretemps qu’on retrouvera dans le ska jamaïcain en 1962, puis dans le reggae, dont il restera la signature.

Bruno BLUM

© FRÉMEAUX & ASSOCIÉS 2013

Merci à Steve Barrow, Chris Blackwell, Antoine Bourgeois, Gilles Conte, Clement Dodd, Gary Karp, David Katz, Linton Kwesi Johnson, King Stitt, Lloyd Knibb, « Dizzy » Johnny Moore, Rainford « Lee Scratch » Perry, Frédéric Saffar, Gilbert Shelton, Soul Stereo Sound System, Gilles Pétard, Roger Steffens et Carter Van Pelt.

1. On peut écouter les remarquables premiers enregistrements d’Ernest Ranglin sur Jamaica - Mento 1951 - 1958 (FA 5275) dans cette collection.

2. Écouter « King Porter Stomp » sur Benny Goodman - The Quintessence 1935-1954 (FA 244) dans cette collection.

3. Écouter dans cette collection Cotton Club 1924-1936 (FA 5189), qui retrace l’histoire de ce célèbre dancing.

4. Écouter dans cette collection l’album The Savoy Ballroom 1931-1955 (FA 074), qui retrace l’histoire de ce célèbre dancing.

5. Écouter Harlem Was the Place 1929-1952 (FA 5175) dans cette collection.

6. Écouter The Greatest Blues Shouters 1944-1955 (FA 5166) dans cette collection.

7. Écouter Jazz, Lindy Hop, Boogie dans notre coffret Anthologie des musiques de danse du monde (FA 5341).

8. Écouter l’album Frank Sinatra - The Quintessence (FA 243) paru dans cette collection.

9. Écouter le succès Rum and Coca Cola des Andrew Sisters sur le volume Calypso de notre coffret Anthologie des musiques de danse du monde (FA 5342) et la version originelle par Lord Invader sur Trinidad - Calypso 1939 - 1959 (FA 5348) dans cette collection.

10. Lire les livrets et écouter dans cette collection les trois volumes Elvis Presley face à l’histoire de la musique américaine, où l’on peut découvrir les versions originales des morceaux enregistrés par Elvis Presley en plus de ses propres versions.

11. Écouter l’œuvre intégrale de Charlie Parker parue dans cette collection.

12. Écouter Country Music 1940-1948 (FA 173) dans cette collection.

13. Écouter Honky Tonk - Country Music 1945-1953 (FA 5087) dans cette collection.

14. Écouter Western Swing 1928-1944 (FA032) dans cette collection.

15. Écouter Country Boogie 1939-1947 (FA 5087) dans cette collection.

16. Écouter The Jumpin’ Blues par l’orchestre de Jay McShann (avec Charlie Parker) en 1942, disponible sur le premier volume de l’intégrale de Charlie Parker (FA 1331) dans cette collection.

17. Éditions Robert Laffont.

18. Écouter Santo Domingo - Merengue (à paraitre dans cette collection).

19. Écouter Trinidad - Calypso 1939-1959 (FA 5348) dans cette collection.

20. Écouter Bermuda - Gombey & Calypso 1953-1960 (FA 5374) dans cette collection.

21. Écouter Harry Belafonte - Calypso - Mento - Folk 1954-1957 (FA 5234) dans cette collection.

22. Extrait de l’autobiographie de Duke Ellington, Music Is my Mistress (Doubleday, Garden City, N.Y., 1973).

23. Lire Le Rap est né en Jamaïque de Bruno Blum (Le Castor Astral).

24. Écouter la version de Laurel Aitken sur l’album Jamaica - Rhythm and Blues 1956-1961 (FA 5358) dans cette collection.

25. Écouter l’album Jamaica - Folk - Trance - Possession 1939-1961 (FA 5384) dans cette collection et lire son livret.

26. Écouter l’album Jamaica - Mento 1951-1958 (FA 5275) dans cette collection et lire son livret.

27. Écouter les tambours nyabinghi de « Moose The Mooche » par Bill Barnwell avec Count Ossie and the Wareikas sur l’anthologie Africa in America (FA 5397) dans cette collection.

28. Extrait de Le Rap est né en Jamaïque (Castor Astral, 2009) de Bruno Blum, p. 63. Entretien du 23 avril 1998 par Carter Van Pelt avec Lloyd Knibb, batteur de jazz dans les formations de Val Bennett et Eric Dean à Kingston dans les années 1950, puis batteur principal des séances de ska des années 1960. Lors d’un entretien au studio Davout à Paris en 2002, Lloyd Knibb m’a rapporté le même témoignage.

29. Lire le livret et écouter l’anthologie Voodoo in America 1926-1961 (FA 5375) dans cette collection.

30. Retrouvez Count Ossie & the Wareikas sur l’album Remember Count Ossie (Moodisc) et les anthologies Africa in America (FA 5397),

Slavery in America (à paraître dans cette collection), Jamaica - Rhythm and Blues 1956-1961 (FA 5358) et Jamaica - Mento 1951-1958 (FA5275) dans cette collection.

31. Écouter l’anthologie Jamaica - Mento 1951-1958 (FA5275) dans cette collection, où l’on retrouve ce rythme, notamment sur le « Not Me » de Hubert Porter.

32. Hors-série du magazine Best, Best of Reggae, 1994.

33. Écouter les albums Gospel Sisters and Divas 1943-1951 (FA 5053) et la série de trois anthologies Gospel (FA 008, FA 026 et FA 044) dans cette collection.

34. Maurice Cullaz, Gospel (Jazz Hot/L’instant, 1990), p. 40.

35. Robert Laffont, 1994.

Jamaica & U.S.A.

Roots of Ska

Rhythm and Blues Shuffle 1942-1962

by Bruno Blum

— What did you dance to?

— Crazy stuff. This was before rock and roll and I loved it all. There was boogie-woogie and blues, there was jazz… people liked really wild dances. And so later I wanted to get into music and sing too.

[Lee “Scratch” Perry talking to the author in 1994; he’d become a reggae star after starting as an assistant to Clement “Coxsone” Dodd in 1961.]

On the edge of jazz and rock, the shuffle style was a product of a dance-based culture that was profoundly Afro-American, and also little-known, because hardly any white American audiences were exposed to it in its day. But that didn’t prevent the shuffle from containing some of the great R&B treasures which were recorded in both America and Jamaica. First ska, and then reggae, derive directly from it.

R&B

The first 45rpm R&B records didn’t go on sale in Jamaica until 1959, and it was early days for quite a small output which obviously couldn’t compete with the immense legacy of twenty years of American production (from which several masterpieces here are taken). Despite all its talent, little Jamaica couldn’t rival with such Forties giants as Professor Longhair, Rosco Gordon, Louis Jordan, T-Bone Walker, Johnny Otis, Little Esther, Johnny “Guitar” Watson or B.B. King. But all the same, Jamaican sound really had something going for it, right from the beginning. The undeniable originality of the shuffle played on the island owed a lot to a guitarist who went on to enjoy an international career playing mento, jazz, R&B, ska and reggae, Ernest Ranglin1. And saxopho-nist Roland Alphonso or trombone-player Don Drummond – future stalwarts of The Skatalites – had no grounds to envy the best American instrumentalists either. As for the singers, Owen Gray, Laurel Aitken, Theophilus Beckford, Bob Marley or Derrick Morgan (to name only a few) made founding records which have remained part of ska and reggae legend. These music-styles have always enjoyed very close ties with R&B, soul, gospel, funk and rap. On another scale, the A&R work of Clement “Coxsone” Dodd (Studio One), Prince Buster (Prince Buster), Duke Reid (Treasure Isle) and Chris Blackwell (R&B/Island) – the four producers at the origins of ska, rocksteady and reg-gae – holds its own in comparison with the greatest American names who inspired them, peo-ple like Nesuhi or Ahmet Ertegun (Atlantic), Julius Bihari (Modern/Meteor), Bumps Blackwell (Specialty), Sam Phillips (Sun), Syd Nathan (King/Federal) or Berry Gordy (Motown).

One Step Beyond

In 1979 there were a few British hits – The Specials’ Gang-ster or Wrong’em Boyo by The Clash (a cover of a rocksteady song by the Rulers), and also One Step Beyond from Madness (a cover of a Prince Buster instrumental) – and they launched a trend that was given the label “ska”. And ever since, this genre has continued to have adepts all over the world (the Tokyo Ska Paradise Orchestra, Jim Murple Memorial, Toasters etc.) Black-and-white chequered clothes and records from the London label 2-Tone were in fashion for a few months in 1979/1981 and then they abruptly disappeared. They gave way to a rockabilly revival launched by Stray Cats and the electronic pop which dominated the British scene in the early Eighties. But the short-lived British “ska” trend at least served to help people discover the original, extremely rich music which had been born in a Kingston studio at the end of 1961. Many Jamaican musicians since then have tried to claim paternity of ska; and many untruths and misleading stories surrounding its birth have continued to be published over the years. This present anthology of pieces borrowed from the legacies of America and Jamaica contains rhythm and blues which was recorded before the first ska titles, and hopefully it puts an end to the debate over ska’s real origins. We also hope it will allow listeners to discover some pieces which are all the more remarkable for the fact that they are hardly known; they will at least allow you to better understand the relations between spirituals and jazz, boogie woogie and rock and roll, swing and jump blues, and shuffle’s relation to ska, of course. Here’s the story.

Dance Hall

After the violence of the economic crisis of 1929, blues was no longer selling. In fact, from being marginal it moved straight to unfashionable. After a lot of trial and error, the Swing craze (named after the jazz rhythm used by musicians like Duke Ellington) started reaching a mass audience in The United States, and in 1935 the highly-danceable tune “King Porter Stomp”2 by Benny Goodman (a virtuoso clarinettist who was also a Jewish New Yorker and the first white bandleader to hire black musicians, namely Lionel Hampton and Teddy Wilson) succeeded in opening people’s ears to jazz. The music had rhythm; it brought dancers to their feet; and it was a dream for improvisers. So you could say that this was how dance-music really reached out to the masses, under the name “swing”.

Until then, Afro-American music styles – which stimulated the body as much as the mind – were kept at a certain distance by the white majority. Broadly, Protestant and Catholic traditions had considered for centuries that music should imperatively lift the spirit towards God. So music had to speak to the mind. On the other hand, the body was seen to be the devil’s instrument: gluttony, sex, desire, etc. To all people outside a small, elite circle, jazz and its free dance-movements were perceived as Negro/vulgar/lewd-and-vaguely-diabolical curiosities – a kind of sin and/or forbidden pleasure reserved for gigolos and whores. Until then, this music that incited people to move their bodies around unashamedly was confined mostly to the haunts of Afro-Americans, i.e. urban dance halls. The Jamaican community in New York was quite large at the time. As Mezz Mezzrow relates in his autobiography, you could find Jamaican marijuana rather easily in New York, and it was a variety which had a lot of fans among jazz musicians, including some of those you can hear in this set. A Jamaican saxophonist by the name of Lord Fly spent a good part of his career in New York before becoming a calypso singer, and there were a few chic cabaret-type places like the Cotton Club3 from which blacks were banned, but which still had a sizeable following amongst white middle-class slummers in search of a good time in the Afro neighbourhoods of New York. Places like these staged some fantastic shows with dancers and musicians, and jazz reached the summits in Afro-American favourites such as the prestigious Savoy Ballroom4 in Harlem5. World War II became a Golden Age for “dance-jazz”, particularly in Kansas City where the underworld had power and money enough to afford great bands like those of Big Joe Turner or Jay McShann (you can hear the latter here accompanying blues-shouter6 Jimmy Witherspoon, whose voice didn’t need a microphone.)

Some venues were temples for dancers and they organized lindy hop7 competitions whose main charac-teristics were free, spontaneous dances that were acrobatic (today you’d call them “acrobatic rock’n’roll”), frenetic and indeed even erotic. For most of the white majority – and for a high percentage of Blacks – lindy hop was about as decadent as you could get. Some fabulous orchestras played in these places, and the medium tempo of the music favoured dancing; it was called swing. Sales of records by Jimmy Lunceford, Lucky Millinder, Count Basie or Duke Ellington increased continually, and in the midst of racial segregation there were white orchestras – those of Paul Whiteman, Gene Krupa, Frank Sinatra8 or Glenn Miller (whose band played written arrangements with no improvising) – which responded to the growing demand for this “swing” music and consequently attracted a large part of this new market for “dance music”. Post-war, in 1945, the great American public continued dancing to the strains of popular music whose Afro-American roots were better integrated. The artists were often white: they were those who dared to adapt to the Afro music-styles that were in fashion, like the rumba, boogie-woogie or calypso of The Andrews Sisters9, the swing of Sinatra — and soon the rock of Elvis Presley10. This, incidentally, is also what happened to Just a Gigolo/I Ain’t Got Nobody by Louis Prima, a white jazz musician from New Orleans who, in 1957, became one of the rare artists to have a popular (i.e. mass-audience) hit with a shuffle piece (in fact, it was such a hit that Walt Disney studios opened their doors to him in 1967 so that he could become the scat-singing King of the Apes in the Jungle Book film.) Two other white singers featured here are Barbie Gaye and Frankie Ford, whose great 1959 hit Sea Cruise owed its success to the excellent accompaniment of a black musician, Huey “Piano” Smith. Huey’s irresistible arrangement was a pure product of Afro-American shuffle as played in New Orleans, but in the prevailing context – fashionable white “rock” dominated by Elvis Presley – Frankie Ford, as a white phenotype, was easier to promote to the media than the more sombre Huey Smith.

After the war and the Golden Age of Kansas City, jazz big-bands were increasingly costly to maintain and also on the way out of fashion; from 1945 onwards, led by Charlie Parker,11 modern jazz would favour smaller groups (commonly called combos). The new jazz – Bebop – was often played at a fast tempo which didn’t always suit either dancers or the public, but it made the sound of Count Basie and Louis Armstrong quite obsolete. What would become of dancers? What about their jazz bands? Well, most of the market would be shared by white musicians playing various kinds of popular music, from the white gospel of Stuart Hamblen to the radio-oriented pop of Jane Froman, Dean Martin or Bing Crosby. And there was also bluegrass, country music12 and its honky tonk style13. Jamaica liked country music, too: the second single from the young Bob Marley was One Cup of Coffee, a reprise of a country hit by Claude Gray in 1961. And the reverse was also true: some white Americans were listening to music whose sound was influenced by Afro-American genres such as Latin music, swing, western swing14 or country boogie15…

Jump Blues

Young Afro-Americans turned to a fashionable post-war sound when they wanted to dance, and its name was jump blues16. Rhythm and blues was in its early days, and jump blues was a young, dance-oriented branch of the tree played by bands where wind instruments were still important. There were excellent musicians around (although not many in number: there were no more big-bands, or only lesser versions), like those in the group led by the genre’s master, Louis Jordan. The tempos played were sometimes fast but most of all, in this continuity of pre-war swing, it was the tempos which made people want to dance. In New Orleans there were blues pianists like Champion Jack Dupree, Archibald, Professor Longhair (here using his left hand to play bass on the piano), plus his Memphis disciple Rosco Gordon, and they were just some of the many guardians of a piano tradition that was boogie woogie’s cousin. Although the first recordings of “Fess” (Professor Longhair) were as recent as 1949 (after Louis Jordan’s first shuffle records), it’s still more than likely that Longhair was one of the conduits, i.e. a “professor” of the shuffle style that conquered Afro-Americans in both America and Jamaica. Some of Rosco Gordon’s tunes (like his 1955 Hey Hey Girl here) seem directly influenced by Professor Longhair.

“Many, many pianists were playing that. It’s impossible to know who it really came from.” [Jon Cleary talking to the author in 2012.]

When a band wanted to bring everyone to their feet, the best way to do it was to play a shuffle, which incidentally is also the aim of this album. Shuffle numbers were basics in the “books” of jazz musicians like Louis Jordan and his Tympani Five, who pioneered the style with exquisite hits like G.I. Jive. Released in 1944, this version of a Johnny Mercer piece has references to the jargon (and rank) of U.S. troops sent to the front in Europe:

PSC the CPL the SGT the LT / CP the whole deal the MP makes you do café / It’s the G.I. jive / Man alive / It starts with the bugle blowing reveille over your head.

In the wake of the popular Louis Jordan, the shuffle’s efficiency encouraged all kinds of R&B groups to record this type of rhythm, like Roy Brown for example (Train Time Blues), a gospel singer who became one of the very first rockers (he composed “Good Rockin’ Tonight”, amongst others.) The legendary group led by trumpeter Dave Bartholomew accompanied almost every artist at Cosimo Matassa’s studio in New Orleans (Little Richard and Fats Domino included). Here Bartholomew plays his own shuffle composition My Ding-a-Ling (he was referring to his penis) which in 1972 gave Chuck Berry one of the biggest hits in his career. James “Wee Willie” Wayne, the immortal creator of “Junco Partner” – an R&B number with heroin as its theme; The Clash did a reggae version of it in Jamaica in 1980 – also used a shuffle rhythm when he was making his first record (and hit) Tend to do Business.

Wind instruments were featured heavily in American R&B in the Forties, but it was also in this period that electric guitarists began to build a reputation as soloists, under the central influence of T-Bone Walker. His disciple B.B. King would line up one hit after another, including the implacable You Upset Me, Baby (a N°1 R&B smash in 1954), which was a pure shuffle. Armed with his four-string guitar, Tiny Grimes (who recorded with Charlie Parker, Art Tatum and other jazz giants), Clarence “Gatemouth” Brown (“Just Got Lucky”, 1949) and Lowell Fulson were others who, like the extraordinary Johnny “Guitar” Watson, left markers for the electric guitar right across blues and rock.

It was rocking, it was rocking / you’d never seen such scuffling, shuffling and rocking ‘til the break of dawn / it was rocking, it was rocking. [Louis Jordan, “Saturday Night Fish Fry”, 1949.]

In Jamaica, jazz guitarist Ernest Ranglin would make a permanent contribution to Jamaican rock with a few shuffle blues titles like Easy Snappin’, Jack and Jill Shuffle or That’s Me (a Theophilus Beckford tune you can listen to here). Great American R&B orchestras like the Johnny Otis Show (here accompanying Pete Lewis, Little Esther Philips and The Robins) also adopted this rhythm, and so did little groups. In fact, jump blues and its shuffle offshoot are quite simply the first forms which were taken by what the Forties called rhythm and blues or rock and roll — as shown by the titles Rockin’ at Home, Rock Bottom, Rockin’ the Blues Away, Rock This Morning, Rockin’ All Day or Rocking in my Feet which are included here.

“In fact, all the characteristic elements of rock were already present in Forties ‘jazz’, and the magic of swing and groove to begin with – which was music that ‘rocked’. In jazz? It was more the music of rhythm. For the majority audience – meaning ‘the white public’ – the distinctions between blues, rhythm and blues, jump blues, boogie woogie, jazz and swing didn’t really exist […] In fact the principal incarnation of successful rock, in its original Forties form, was what we commonly call jump blues, characterized by rock compositions played by a jazz/R&B orchestra conceived for dancing.” [Le Dictionnaire du rock, “Jazz” section, 2013 edition.]17

The dancing shuffle of pioneering electric guitarists was also present in jazz/R&B instrumental titles recorded by T-Bone Walker (T-Bone Shuffle), Lowell Fulson (Guitar Shuffle) or Tiny Grimes and his Rocking Highlanders (Rockin’ the Blues Away). The Jamaican guitarist Ernest Ranglin was less well-known, but you can hear from Silky and That’s Me that his talent rivalled that of his famous American counterparts. Afro-American music circulated widely across America and the Caribbean; from Santo Domingo,18 merengue spread to conquer Venezuela, Haïti and other islands; Cuban and Brazilian music crossed to many countries and fused with post-war “Latin” jazz; Trinidad’s calypso19 and mento from Jamaica conquered the West Indies as far as Bermuda20 and went on to world fame with Harry Belafonte21. And similarly, the rhythm and blues of the southern United States found its place in Jamaica: heard on American stations and much-appreciated in the island’s dance halls, shuffle would be recorded in Kingston’s first studios in 1956 (it was only a two-hour flight from Miami…) The album Jamaica - Rhythm & Blues 1956-1961 in this collection has some forty Jamaican shuffles that complement this anthology. The booklet in that set gives details of Jamaican R&B history and the “sound-systems” of the dee-jays who caused dancers in Jamaica’s poor neighbourhoods to discover shuffle.

Jamaica

A whole strain of West Indian musicians came up who made contributions to the so-called jazz scene, and they were all virtually descended from the true African scene. [Duke Ellington].22

From around 1954 onwards, and probably a little earlier, there were some small clubs like the Glass Bucket in Kingston which billed local jazz musicians who were ready to play R&B styles. Most Jamaicans, however, couldn’t afford to go to places like those and, unlike Americans, they didn’t have popular dance-halls to go to either, i.e. places where they could hear jazz or R&B bands. In the poorest ghettos – where the demand for music was very high – people had to make do with imported American records, brought in first by soldiers during the war, and then by deejays who were following the trends across the water. Blues parties were organized by crews owning portable P.A. systems and amplifiers etc., which they hired out to bars where shuffle and swing were played all the time. The story of these Jamaican “sound systems” can be found in more detail in the booklet inside the album Jamaica - Rhythm and Blues 1956-1961.

Numerous American musicians, as here with Harold Land, or saxophonists Todd Rhodes (Page Boy Shuffle) and Willis “Gator” Jackson, cut shuffle instrumentals where the dominant sounds were provided by wind instruments. From around 1950 onwards, the hit Later for the Gator by “Gator” Jackson was the “theme-tune” with which Clement “Coxsone” Dodd opened and closed his dance-nights in Kingston. Coxsone rechristened it the “Coxsone Hop” so that his competitors wouldn’t be able to get their hands on the record, and it remained exclusive to his own Downbeat sound system for a long time. Dodd also kept the real title of Harold Land’s San Diego Bounce a secret: for ages it was known to Jamaicans as “Coxsone Shuffle”. Coxsone quickly went on to become the island’s most important R&B producer, switching to ska in 1962 and later rocksteady and reggae. For the first sessions he produced in 1956, Dodd brought together Clue J and the Blues Blasters, i.e. the cream of the island’s jazz-players, and asked them to carefully clone the sound of American shuffle (while still making their own voices heard, of course): Gene Coy’s Killer Diller title from 1948 would be picked up by the Blues Blasters, and they put part of its theme into their own instrumental “Milk Lane Hop”, a shuffle they recorded in 1961. “Killer Diller” also had a spoken passage which recalled the style of Jamaica’s deejays when they were emceeing behind their sound systems, and it’s certain that this influential piece inspired the island’s later deejays to become the original pioneers of rap before they exported it to New York in the Seventies. And we all know how successful that was...23

If there was one thing Jamaica liked, it was an instrumental, and jazz was particularly popular there in the Fifties. It covered the whole population, too, unlike in America where segregation was so widespread that most whites didn’t hear much jazz at all. So the first Jamaican R&B records contained a lot of shuffle instrumentals with a jazz imprint, like the Afro/Rasta manifesto African Shuffle by Count Ossie and the Wareikas, and Joker or Yard Broom with saxophonist Roland Alphonso. The instrumentals Stew Peas and Cornflakes, Silky or The Man Is Back by the great trombonist Don Drummond are all examples of that decisive influence which jazz had over Coxsone Dodd’s productions. As for Luke Lane Shuffle and Duke’s Cookies with Rico Rodriguez (a trombone-player taught by Drummond), they were produced by Coxsone Dodd’s great rival Duke Reid. Reid dominated Jamaica’s sound systems in this period, and Duke Reid’s Group was a prestigious name that appeared on several records.

Influenced by the style of gospel’s jubilee groups, a good many American R&B groups also practised the difficult discipline of vocal harmonies. There are a few splendid titles here from the Robins, Little Esther and Bill Brown with Billy Ward and His Dominoes — and not forgetting the extremely “covered” Oop Shoop from Shirley Gunter and the Queens, which exemplifies the style later called “doo wop”. With a strong presence in both America and Jamaica, black gospel and “barber-shop” or “jubi-lee” harmonies left a strong impression on rhythm and blues, and American vocal groups were particularly popular with Jamaicans. You can see just how influential they were in the Jamaican titles in this set (end of CD2 and CD3): Chuck & Dobby, Busty & Cool and Winston & Barbara were all notably marked by Shirley and Lee, a famous New Orleans duo. Ska later came to reinforce that trend with great vocal groups such as the Clarendonians, the Gaylads with Dobby Dobson, Higgs and Wilson, the Techniques, the Wailers, etc.

Laurel Aitken, Jamaica’s first rhythm and blues star, also recorded the Floyd Dixon song Hey Bartender24 included here (it was also picked up by The Blues Brothers). No More Doggin’, the first shuffle recorded by Rosco Gordon in 1952, was a big hit in the U.S.A. One of his admirers was Jamaican pianist Theophilus Beckford and he copied Rosco’s style, as you can hear on That’s Me. Theo was the N°1 pianist with Clue J and his Blues Blasters, and he played the eighth note “skank” rhythm-pattern on many of the first Jamaican R&B records (cf. discography), so his influence on ska – and the reggae to come – is not to be underestimated.

Shuffle or Ska?

Ska suddenly appeared a few months before Jamaica’s independence in August 1962 and for three years it enjoyed a Golden Age until it went out of fashion in 1965, when it metamorphosed into reggae, a genre which was to have considerably greater importance. In turn, reggae went through various mutations to become a symbol of so-called world music in reflecting a multicultural society.

Reggae’s most famous musician Bob Marley recor-ded many ska titles early in his career but his first record, Judge Not (1962), was earlier than ska: it’s a piece where the drums play a characteristic U.S. shuffle rhythm from The United States. There are ties between shuffle and native Jamaican music-forms – revivalist Negro spirituals25, gospel, mento26 (the fife you can hear in Judge Not is a good example), jazz3 and nyabinghi27 – but genuine ska is almost 90% derived from the American shuffle style steeped in jazz and jump blues. In Jamaica – where nobody could hear local music on national radio, and dance-floors were the only “media” available to popular music – the disc jockey culture was a determining factor.

Shuffle also had a direct impact on the first international ska hit. Guitarist Ernest Ranglin was deeply marked by the pioneer of the electric guitar in jazz, Charlie Christian, and Ranglin took lessons from Jamaican Cecil Houdini before turning professional at the age of sixteen, playing first with Val Bennett’s jazz band and then with Eric Dean, who had the best jazz group in Jamaica. Ranglin was one of the main actors in the first mento recordings made in Jamaica before leading the way in Jamaican shuffle (as early as 1956) and then ska. Ranglin is also notable for his recording of a ska version of Millie Small’s My Boy Lollipop, the huge international hit – it sold six million copies – which in 1964 contributed to make a fortune for its producer Chris Blackwell, who invested part of his gains in the creation of Island Records. Blackwell went on to issue Jamaican shuffle and ska in the U.K. before introducing the likes of Steve Winwood and Cat Stevens to the world, along with King Crimson, Toots, Bob Marley, U2, Grace Jones and many, many more. The original version of My Boy Lollipop is hardly known at all, but you can listen to it here: it’s an American shuffle recorded eight years earlier by Barbie Gaye, and it sounds almost exactly like Millie Small’s record. Barbie Gaye was fifteen when she recorded this song written by The Cadillacs’ Robert Spencer, and American DJ Alan Freed often played the record. It was enough of a hit for Barbie to get the chance to open for Little Richard in Freed’s 1956 Christmas show.

What’s the difference between shuffle and ska? Mainly rhythmical, because the wind instruments used, plus the gospel-influenced vocals and bluesy/jazz guitars, are almost exactly the same. The principal characteristic of R&B shuffle is a “swing” drum-pattern with a walking bass line, generally consisting of quarter notes and played on a pentatonic scale. You can find it as early as 1942 in It’s a Low-Down Dirty Shame by Louis Jordan and his Tympany Five. Shuffle – American or Jamaican – wouldn’t deviate from this, and it turned into ska in the winter of 1962. Some pieces fall exactly where the two rhythms are hinged, like One Cup of Coffee. The creation of ska rhythm by Jamaican drummer Lloyd Knibb dates from the end of 1961 or early 1962:

“It all started with rhythm and blues. Then the music changed. Coxsone called me at the studio one day and said to me, ‘Lloydie, I want to change the rhythm, you know? Find a beat.’ OK, so I went to the studio and I tried a really different rhythm. I started with the Burru style [Ed. note: the ntoré rhythm named after the drums in eastern Congo] and found myself on the second and fourth beats right at the back of the beat, and we put everything else we had right in there. The second and fourth beats were the most direct rhythm. Coxsone said ‘yeah’ and that was it. From rock and roll and rhythm and blues we went to ska. Everybody got hooked on that rhythm. And everybody recorded it, Bob Marley, One Cup of Coffee, I remember that one. Owen Gray, Delroy Wilson, Alton Ellis, you name them, they were all in there with us at some time.”28

Shuffle origins

Shuffle drums were played in a style derived from boogie woogie piano. You can sometimes hear that da-da/da-da/da-da (well in evidence here on T-Bone Shuffle from T-Bone Walker or Jamaica Blues by Azie Lawrence) which was sometimes played in chords by the left hands of some of the great Thirties boogie pianists like Jimmy Yancey, Willie “The Lion” Smith, Meade “Lux” Lewis, Albert Ammons or Memphis Slim. On drums, this basic ternary rhythm combined with a walking bass formed the roots of swing jazz or the modern “rock” jazz like Rock This Morning by Jesse Allen & James Gilchrist. Perhaps its roots go deep into the Bambara music of New Orleans or a Congolese rhythm, the ntoré30 that was probably a common feature of the famous Creole bamboulas in New Orleans’ Congo Square in the 19th century; many people from the Congo were deported to Louisiana and Jamaica shortly before slavery was abolished, and so the Bantu culture of the Congo left its mark on the whole West Indies29. The ntoré rhythm of the Congo found itself deeply anchored in Afro-Jamaican music, which has great natural affinities with swing. You can find it notably in Burru drumming, Kumina revivalist ceremonies and the nyabinghi of Rastas, who always sought to preserve the memory of slavery and strengthen their African identity. You can listen to a rare mixture of pure shuffle and these ritual Rasta drums on African Shuffle by the legendary Count Ossie and the Wareikas30. It is also present in traditional Jamaican mento31. Concerning its other musical elements in the rhythm and blues featured in this set – apart from the walking bass & drum part – the shuffle’s specificity lies with the right hand on the piano, and sometimes the electric guitar, playing brief chords on the off-beat (on the “and” when you count “1-and-2-and-3-and-4-and…”). This custom was deve-loped in shuffle in the Forties. In Jamaica it is called skank, meaning “dance” in the local patois, and it gave its name to ska in 1962 (returning to the front in reggae, which was born in 1968). A clear example of skank can be heard in records by the first giant of rhythm and blues, Louis Jordan, one of the great creators of rock and roll and jazz who, in 1942, recorded It’s a Low-Down Dirty Shame in this very danceable shuffle style. Singer/saxophonist Jordan was looking for success, and he found it; he was extremely popular (and influential) among Afro-Americans post-war. He sang remarkably well-written little stories, often funny, with music that he wanted people to dance to, music with a catchy hook in the swing spirit referred to above; Jordan recorded some invincible titles like Choo Choo Ch’Boogie (1946) or Boogie Woogie Blue Plate (1947). The lure of the shuffle (its afterbeat or offbeat) was total. In the midst of racial segregation, shuffle and its magical powers of swing managed to seduce mass white audiences, and that “shuffle” accent on the offbeat acted as an incredible amplifier for those with a desire to dance. According to Linton Kwesi Johnson – dub poet, reggae star and sociologist – “You find it in all our music, reggae, calypso, mento, the music from Martinique, Guadeloupe; you can find it in hi-life, merengue... And that attraction for the afterbeat is found in churches, with tambourine rhythms, hand-claps etc.” [Linton Kwesi Johnson speaking to the author.]32

In Afro-American cultures, in fact, African religions were mixed with the biblical religions of Methodist, Pentecostal, Baptist, Apostolic and other churches.33

“Only spirituals were sung at ring shouts and there were strict rules governing the dance-style. The feet should never cross; otherwise you’d immediately think it was non-religious. For the strictest believers, the feet should never leave the ground, with movement only obtained through a shuffle, that sliding step which, much later, became a dance-step which black dancers practised with virtuosity.”34

In The United States as in nearby Jamaica, these intense “Revivalist” religions incorporated different elements of African rituals. On the continent of North America they were present as early as the 18th century in circles where Negro spirituals freed the soul.

“Originally, the shuffle was a rubbed (flat-footed) step used by slaves at their ring shouts. Later, at the time of the minstrels, came the soft-shoe shuffle which gave rise to several variants. And that step was no doubt transposed much later into the orchestra, giving rise to a particular rhythm. That rhythm is the one produced by the left hand in boogie-woogie, with eight bass-notes in each bar – eight-to-the-bar – or in other words, eight unequal eighth-notes (quavers) played “swing.” [Philippe Baudoin, le Dictionnaire du jazz.]35