- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

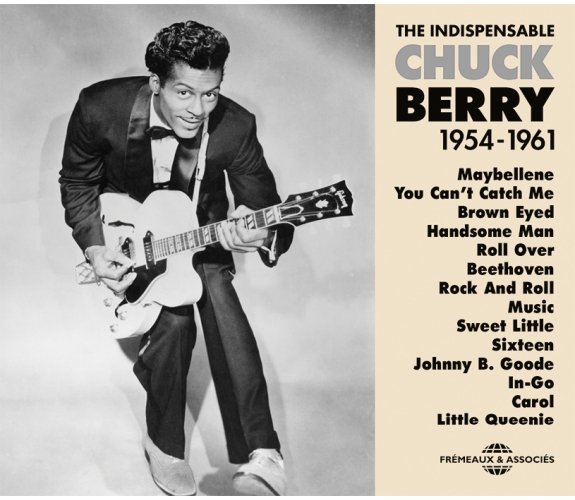

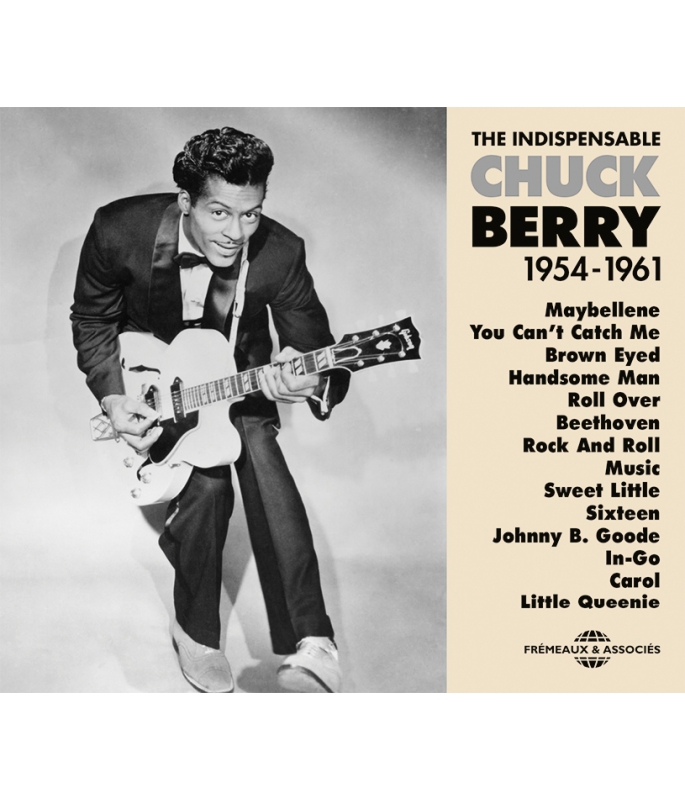

THE INDISPENSABLE 1954-1961

CHUCK BERRY

Ref.: FA5409

Artistic Direction : BRUNO BLUM

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Total duration of the pack : 2 hours 57 minutes

Nbre. CD : 3

THE INDISPENSABLE 1954-1961

THE INDISPENSABLE 1954-1961

As Rock ‘n’ Roll’s great modernizer when the Fifties turned into the Sixties, Chuck Berry was one of the most influential musicians in 20th century American pop. His compositions have been played by the greatest, from Count Basie to The Beatles, and are today so famous that people forget that Chuck’s originals were the greatest… Here, compiled by Bruno Blum, are Berry’s indispensable songs from 1954 to 1961. Patrick FRÉMEAUX

“There’s only one true king of rock ‘n’ roll. His name is Chuck Berry.” Stevie WONDER

JAMES BROWN

THE INDISPENSABLE 1959-1962 VOL. 2

ELVIS PRESLEY & THE AMERICAN MUSIC HERITAGE...

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1MaybelleneChuck BerryRuss Fratto00:02:251955

-

2We We HoursChuck Berry00:03:061955

-

3Thirty DaysChuck Berry00:02:261955

-

4Together We Will Always BeChuck Berry00:02:391955

-

5You Can'T Catch MeChuck Berry00:02:461955

-

6Downbound TrainChuck Berry00:02:521955

-

7No Money DownChuck Berry00:03:001955

-

8Roly PolyChuck Berry00:02:531955

-

9Berry Pickin'Chuck Berry00:02:341955

-

10Drifting HeartChuck Berry00:02:521956

-

11Brown Eyed Handsome ManChuck Berry00:02:201956

-

12Roll Over BeethovenChuck Berry00:02:261956

-

13Too Much Monkey BusinessChuck Berry00:02:571956

-

14Havana MoonChuck Berry00:03:101956

-

15School DayChuck Berry00:02:441956

-

16La JaundaChuck Berry00:03:141956

-

17Blue FellingChuck Berry00:03:031956

-

18How You've ChangedChuck Berry00:02:501957

-

19Rock And Roll MusicChuck Berry00:02:341957

-

20I've ChangedChuck Berry00:03:081957

-

21Oh Baby DollChuck Berry00:02:401957

-

22Rockin' At The PhilharmonicChuck Berry00:03:251957

-

23I Hope These Words Will Find You WellChuck Berry00:02:431954

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Sweet Little SixteenChuck Berry00:03:041957

-

2Guitar BoogieChuck Berry00:02:221957

-

3Johnny B.GoodeChuck Berry00:02:421957

-

4In GoChuck Berry00:02:301957

-

5Reelin' And Rockin'Chuck Berry00:03:181958

-

6Around And AroundChuck Berry00:02:411958

-

7It Don't Take But A Few MinutesChuck Berry00:02:281958

-

8Hey PedroChuck Berry00:01:591958

-

9Blues For HawaiiansChuck Berry00:03:261958

-

10CarolChuck Berry00:02:501958

-

11Oh Yeah!Chuck Berry00:02:361958

-

12Time WasChuck Berry00:02:001958

-

13House Of The Blue LightsChuck Berry00:02:281958

-

14Beautiful DelilahChuck Berry00:02:171958

-

15Jo Jo GunneChuck Berry00:02:481958

-

16Sweet Little Rock And RollerChuck Berry00:02:241958

-

17Anthony BoyChuck Berry00:01:551958

-

18Memphis 2Chuck Berry00:02:151958

-

19Little QueenieChuck Berry00:02:441958

-

20Run Rodolph RunChuck BerryMarks00:02:461958

-

21Merry Christmas BabyChuck BerryJonnhy Moore00:03:161958

-

22Almost GrownChuck Berry00:02:231959

-

23Back In The UsaChuck Berry00:02:291959

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Betty JeanChuck Berry00:02:331959

-

2County LineChuck Berry00:02:191959

-

3Broken ArrowChuck Berry00:02:281959

-

4Let It RockChuck Berry00:01:491959

-

5Too Pooped To PopChuck Berry00:02:371959

-

6Don't You Lie To MeChuck Berry00:02:101960

-

7Drifting BluesChuck BerryEdward Williams00:02:181960

-

8Worried Life BluesChuck Berry00:02:131960

-

9Bye Bye JohnnyChuck Berry00:02:071960

-

10Our Little Rendez-VousChuck Berry00:02:041960

-

11Run AroundChuck Berry00:02:331960

-

12Jaguar And The BthunderbirdChuck Berry00:01:541960

-

13I Got To Find My BabyChuck Berry00:02:181960

-

14Little StarChuck Berry00:02:481960

-

15Down The Road ApieceChuck Berry00:02:171960

-

16Confessin' The BluesChuck BerryJay McShann00:02:111960

-

17Sweet SixteenChuck Berry00:02:491960

-

18Mad LadChuck Berry00:02:231960

-

19Route 66Chuck Berry00:02:501961

-

20I'M Talking About YouChuck Berry00:01:521961

-

21Come OnChuck Berry00:01:511961

-

22Go Go GoChuck Berry00:02:361961

-

23The Man And The DonkeyChuck Berry00:02:071961

Chuck Berry FA5409

THE INDISPENSABLE

Chuck Berry

1954-1961

Maybellene

You Can’t Catch Me

Brown Eyed

Handsome Man

Roll Over

Beethoven

Rock And Roll Music

Sweet Little

Sixteen

Johnny B. Goode

In-Go

Carol

Little Queenie

Chuck Berry

The Indispensable 1954-1961

Par Bruno Blum

Il n’y a qu’un seul vrai roi du rock ‘n’ roll. Il s’appelle Chuck Berry.

— Stevie Wonder

The Indispensable Chuck Berry

De tous les musiciens de rock, Chuck Berry est sans doute le plus important. Il est probablement le plus grand auteur-compositeur du genre, un des plus grands hommes de scène et l’un des meilleurs guitaristes, un instrument avec lequel il a, plus que tout autre, contribué à définir les contours du style rock. En alimentant le rêve américain de son temps avec des chansons imagées, Berry est l’un de ceux qui ont transformé le rock originel de Louis Jordan, Tiny Bradshaw, Ike Turner ou Roy Brown en une formule capable d’atteindre le public blanc — c’est à dire le grand public.

Appelez ça comme vous voudrez : jive, jazz, jump, swing, soul, rhythm, rock ou même punk, c’est toujours du boogie en ce qui me concerne. […] Quand c’est du boogie avec un nom étranger, le lien ça reste le boogie, qui est mon genre de musique.

— Chuck Berry

Sciemment pensées pour séduire, conçues dans le but de trouver le langage rock universel, ses compositions ont été enregistrées par les plus grands, de Count Basie à Elvis Presley, des Rolling Stones aux Beatles, de Jimi Hendrix à Peter Tosh, des Ramones aux Sex Pistols et de Creedence Clearwater Revival à Wyclef Jean. Il restera pour toujours une figure centrale du classic rock originel avec ses images de pin-ups, de juke-boxes, de disques 45 tours, de guitares électriques vintage, de radio rock, de danses libres, de flirts en voiture américaine aux larges banquettes et de cinémas drive-in.

Le dessin animé à succès de Walt Disney/Pixar Cars (John Lasseter, Joe Ranft, 2006), où on peut l’écouter interpréter Route 66, en témoigne1. Les enregistrements originaux de ses nombreux classiques, comme Roll Over Beethoven ou Maybellene restent insurpassables. Ce coffret contient la quasi totalité de ses morceaux gravés avant sa seconde incarcération, qui brisera sa carrière en 1962.

Brown Eyed Handsome Man

Les meilleurs rockers blancs des années 1950, parmi lesquels Gene Vincent, Eddie Cochran, Buddy Holly, Elvis Presley ou Jerry Lee Lewis étaient fondamentalement des chanteurs de country qui chantaient «?noir?» en cherchant à transmettre une émotion vocale jusque-là surtout réservée au gospel et au blues. Chuck Berry était un miroir qui leur renvoyait l’image inverse : il filtrait la country avec une sensibilité rhythm and blues.

En dominant le rock, qui a conquis la jeunesse des années 1950 et enfoncé les barrières raciales de façon profondément subversive, il représente aussi, peut-être plus que tout autre, la revanche, le triomphe artistique d’un Afro-américain en ces cruelles années de ségrégation dont il a souvent souffert. Chez lui à St. Louis, les places arrière des trams étaient par exemple obligatoires pour les «?colored?». Loin du personnage soumis de l’?«?Oncle Tom?», dans son chef-d’œuvre à la gloire de cette musique Roll Over Beethoven, l’impertinent Chuck Berry chante avec le sourire qu’en apprenant le succès du rhythm and blues, Beethoven devait se retourner dans sa tombe — une litote signifiant que la musique afro-américaine avait dépassé en popularité la musique blanche de tradition écrite.

Tu sais ma température monte/Le juke-box a pété les plombs/Mon cœur bat le rythme et mon âme chante le blues/Retourne-toi Beethoven, et donne les nouvelles à Tchaïkovski

— Chuck Berry, Roll Over Beethoven, 1956

Il fait aussi allusion à ce thème avec Rockin’ at the Philharmonic. Et sur Brown Eyed Handsome Man, la «?femme du juge?» plaide pour qu’un homme noir qui a séduit une femme blanche soit libéré. Cette litote fait allusion aux lynchages, fréquents dans sa région et souvent motivés par des relations sexuelles interraciales entre hommes noirs et femmes blanches consentantes. Son père n’avait cessé de le mettre en garde contre tout «?manque de respect?» ou toute avance faite à une femme blanche, qu’il pourrait payer cher. L’Afrique est présente ici via les influences latino-caribéennes entendues notamment sur Havana Moon (dérivé du «?Calypso Blues?» de Nat «?King?» Cole), La Jaunda, mais aussi sur Jo Jo Gunne, une adaptation du «?Jungle King?» de Cab Calloway ou du «?Signifying Monkey?» de Willie Dixon basés sur un conte d’origine yoruba (qu’il entendit en prison). On peut écouter ces deux derniers et en lire l’histoire dans le coffret Africa in America 1926-1962 (FA 5397) dans cette collection.

L’une des quatre arrière-grand-mères de Chuck Berry est née du mariage d’un esclave d’origine africaine, Isaac Banks, et d’une cuisinière indienne Chihuaha de l’Oklahoma. Charles Banks, un de leurs sept enfants, devint le grand-père maternel de Chuck. C’est en Oklahoma qu’il rencontra Lula Thomas, fille d’un cuisinier d’origine africaine employé dans les trains de luxe et d’une voyageuse anglaise blanche. Née en 1867, Lula avait la peau claire. Elle avait été la première personne de la famille à naître après l’abolition de l’esclavage. Ils eurent eux aussi sept enfants dont la deuxième fille Martha deviendrait la mère de Chuck Berry. Côté paternel, le grand-père William Berry est né de l’union d’un Indien de l’Oklahoma et d’une esclave d’origine africaine. William était un séducteur à l’infidélité notoire. Sa femme Lucinda est décédée quand leur fils Henry avait douze ans. Ainsi, Henry le père de Chuck a-t-il été élevé par ses grands-parents maternels Charles et Lula. Henry n’a jamais oublié la légèreté de son père coureur de jupons toujours en voyage et, sans doute en conséquence, il donnera une éducation religieuse très stricte à ses six enfants dont Charles Edward Anderson Berry, dit Chuck, est né à 6h59 le 18 octobre 1926 au 2520 Goode Avenue, St. Louis, Missouri.

Worried Life Blues

Les negro spirituals et le gospel bercent l’enfance du jeune Charles : le chœur du temple baptiste où chantent ses parents répète à la maison. Pauvre mais unie, la famille Berry chante en harmonie en toute occasion et fréquente assidûment le temple du coin de la rue en plein quartier noir de St. Louis. Son père Henry restera administrateur du temple Antioch pendant 36 ans. Henry travaille à plein temps dans un moulin industriel, puis à mi-temps dans la longue crise économique des années 1930. Il complète ses revenus comme homme à tout faire pour une firme immobilière : poubelles, peinture, menuiserie, réparations… payé très en dessous du tarif syndical réservé aux Blancs. Charles partage son lit tête-bêche avec deux autres enfants. Très tôt, il gagne quelques cents en vendant des fruits et légumes à la criée dans les rues (il chante les noms de tout ce qu’il vend) et assiste bientôt son père sur les chantiers. Il rêve de conduire un camion.

Une grosse radio Victrola (puis une Philco de 1929) orne le salon et le soir les enfants Berry ont parfois l’autorisation d’écouter Fats Waller, Bing Crosby ou Louis Armstrong - ce qui les change de la musique religieuse. Charles est friand de country music comme de boogie-woogie. Comme sa mère, à longueur de journée sa grande sœur Lucy joue du piano. Elle chante avec passion du gospel et des standards populaires. Charles lui dispute l’accès au piano : il aime les disques dansants comme Worried Life Blues de Big Maceo, «?Going Down Slow?» de St. Louis Jimmy, «?C.C. Rider?» par Bea Boo, «?A Ticket a Tasket?» par Ella Fitzgerald et bien d’autres — mais sa sœur continue à chanter l’«?Ave Maria?» et «?God Bless America?». Charles adore Tampa Red dont il enregistrera en 1960 le Don’t You Lie to Me2, Lonnie Johnson3, Arthur Crudup, Muddy Waters4 et Rosetta Tharpe5 — tous des guitaristes — et la grande chanteuse de blues Lil Green. Ses frères et sœurs préfèrent plutôt les orchestres de Duke Ellington, Tommy Dorsey, Count Basie. Ses prières n’étant pas entendues, Charles commence à douter sérieusement de la religion dans laquelle il baigne. Mais il rejoint les Jubilee Ensembles, un groupe vocal de spirituals et gospel où il brille par son interprétation de «?Tempted and Tried?». Il enregistrera en 1956 Downbound Train, un morceau sur le thème de la modération inspiré par plusieurs poèmes connus et par la foi ambiante. Il y décrit le train vers l’enfer (en opposition au train vers le paradis chanté dans tant de spirituals) d’un alcoolique. Après quelques essais, Charles s’abstiendra de consommer marihuana, tabac et alcool, ce qui explique sans doute sa longévité. Il leur préfèrera les femmes.

Sweet Little Sixteen

Mais Charles Berry a de moins en moins envie d’une vie rangée : selon lui c’est une arnaque, qu’il chantera dans Too Much Monkey Business. Après le collège le jeune adolescent travaille dans une épicerie qui lui donne une indépendance financière lui permettant de retaper un vélo à partir de pièces détachées. Il s’achète un drape suit (costume et pantalon très amples) à la mode. Il commence aussi à voler quelques œufs à l’épicerie — et se fait prendre. Il traîne près des juke-boxes et rêve de conquérir une femme, un projet qu’il évoquera dans plusieurs chansons comme Sweet Little Sixteen où il décrit une jolie collectionneuse d’auto-graphes de seize ans qui redevient une sage étudiante le lendemain matin. Une chose plus que toute est interdite aux membres de la famille : les relations sexuelles avant le mariage. Mais précoce, le garçon a du succès et il a quinze ans en 1941 quand son père le corrige violemment à coups de lanière d’un épais cuir à affilage pour rasoirs après qu’il ait eu une relation avec la fille d’un voisin diacre. D’autres relations de Charles sont ainsi punies et brisées (occasionnant un chagrin d’amour) par ces très douloureux coups de lanière de cuir sur les fesses. Ces humiliations et souffrances le fâchent définitivement avec la religion et l’éloignent de sa famille. Quelque chose se brise en lui. Charles traîne en vélo avec des copains de son âge, Skip et James, et commence à mal tourner. L’essence est rare pendant la guerre et ils se font de l’argent de poche en volant l’essence qu’ils vidangent dans les réservoirs des voitures stationnées la nuit. Charles est aussi témoin du braquage d’un alcoolique. Il déteste l’alcool et estime que le buveur s’est mis en position de faiblesse avec sa boisson et l’a cherché. Très rationnel et pragmatique, l’adolescent est passionné par la photographie et diverses sciences. Il apprend la guitare en autodidacte.

La musique c’est de la science. Tout est de la science. Parce que la science, c’est la vérité.

— Chuck Berry

Au collège il décide de participer à un spectacle où il ose chanter Confessin’ the Blues, le dernier succès de Jay McShann, un pianiste de Kansas City. Il sait que ce morceau est un succès chez les jeunes et veut leur donner ce qu’ils aiment plutôt que les chansons guindées habituelles dans ce genre de soirée. Il reçoit un tonnerre d’applaudissements et décide de se mettre sérieusement à la guitare après avoir réalisé que la plupart des chansons qu’il aime se jouent sur quelques accords. Un copain de classe lui prête une guitare ténor (quatre cordes). Le soir, Charles travaille pour un réparateur de radios. Déjà bricoleur, il se passionne pour l’électronique et devient disc jockey. Il racontera avec School Day et Almost Grown le sentiment de liberté que le rock and roll et la romance procurent aux ados accablés par les études. Il joue des disques de «?rhythm?» et de jazz. Avec l’argent gagné il s’offre sa première voiture d’occasion, une Ford V-8 de 1934 et ne cessera plus d’acheter et revendre sans cesse des voitures qui font de lui la vedette du quartier et de la high school. Il évoquera ces marchandages d’automobiles dans No Money Down.

Blue Feeling

À 17 ans en 1944, Charles n’a pas été appelé pour la Seconde Guerre Mondiale. Il est devenu un play-boy. Mais un nouvel échec sentimental (une lesbienne) le traumatise. Il ne quitte plus ses deux copains Skip et James, qui l’entraînent vers la délinquance. Ils décident de partir à l’aventure dans la voiture de Charles. À court d’argent et d’essence à Kansas City, Skip braque un magasin pistolet à la main. Puis un autre. Charles l’imite avec un calibre 22 hors d’usage et y laisse presque sa peau — le coiffeur était armé et sur le point de dégainer. Skip attaque plusieurs autres magasins puis ils décident de rentrer à St. Louis. Tombés en panne sur l’autoroute, les ados arrêtent une voiture qui venait leur proposer de l’aide et braquent le conducteur. Ils volent sa voiture et remorquent l’Oldsmobile de Charles. Mais l’aimable automobiliste appelle la police qui les poursuit (la chanson Jaguar and the Thunderbird relatera une poursuite avec la police, qui n’arrive pas à rattraper les délinquants). Ils se font vite prendre. Après un procès de vingt minutes, Charles Berry est condamné à une lourde peine : dix ans de prison ferme pour attaque à main armée. Les trois complices sont incarcérés à la prison d’Algoa, près de Jefferson dans le Missouri. Charles y participera à un groupe de boogie-woogie et, comme James Brown peu après lui6, à un quartet d’harmonies vocales de gospel. C’est sans doute pendant cette période que, dans la solitude d’un dortoir qu’il repeindra seul, il conçoit quelques blues magistraux comme Wee Wee Hours (inspiré par le «?Wee Baby Blues?» de Joe Turner). Après une rocambolesque histoire d’amour (jamais consommée) avec l’épouse blanche du directeur de la prison, qui rappelle beaucoup Brown Eyed Handsome Man, il obtient une réduction de peine et sera libéré au bout de trois ans, le jour de ses vingt-et-un ans, le 18 octobre 1947.

Together We Will Always Be

Son frère Henry est revenu de la guerre du Pacifique. Il surnomme Charles du diminutif «?Chuck?». Libéré, bien décidé à prendre sa revanche sur la vie, l’ex braqueur amateur reprend la menuiserie, les réparations avec son père — et la guitare. En prison il a ressassé et gravé dans le marbre de sa tête les meilleurs moments de son adolescence révolue, qu’il mettra en scène avec nombre de compositions. Pour Chuck, le belle vie c’était d’emmener une jolie fille se promener en voiture au son de la radio et de sentir le vent de la liberté siffler aux fenêtres. Il le chantera par exemple sur son chef-d’œuvre You Can’t Catch Me, où il compare sa voiture à un avion. Cette volonté de faire revivre l’intimité et la magie de cette adolescence perdue habite toute son œuvre, comme ici dans Back in the USA ou Carol. En six mois, Chuck Berry a économisé de quoi se payer une somptueuse Buick Roadmaster noire et revient à sa vie de séducteur. Beau, costaud, drôle et intelligent, il séduit Themetta «?Toddy?» Suggs qu’il promène en Buick. Ils se marient le 28 octobre 1948 et emménagent dans le petit salon de beauté qu’elle a ouvert. Il chante sa rédemption et sa revanche dans Together We Will Always Be, un hymne au mérite, à l’effort : «?Rien ne bat mieux l’échec que l’effort/Il y a une grande récompense?». Chuck n’est pas pour autant fidèle et une relation avec une femme blanche lui attire des ennuis avec la police raciste, à qui il doit mentir pour éviter un passage à tabac, voire un lynchage ; il jure de ne plus prendre le risque de fréquenter une blanche (mais ne tiendra pas parole). Le couple travaille dur et achète une maison en 1949. Ils en louent trois pièces. Leur fille Ingrid naît le 3 octobre 1950.

Rock and Roll Music

Chuck prend sa carte du syndicat des musiciens sans laquelle il n’a pas le droit de jouer en public, et se perfectionne en chantant dans un bar blanc seul avec sa guitare. Il travaille comme portier à la radio WEW et achète à un guitariste de gospel sa première guitare électrique d’occasion. Il acquiert aussi un petit magnétophone à bande à l’été 1951 et enregistre ses premiers essais. Il apprend l’essentiel de son style de guitare avec Ira Harris, un jazzman très influencé par Charlie Christian7. Chuck a acheté une méthode de musique et écoute assidument T-Bone Walker8, Buddy Johnson, Nat «?King?» Cole9, Charles Brown10 (il reprend ici son Driftin’ Blues) et Louis Jordan11. Il est particulièrement admiratif de Carl Hogan, le guitariste du Tympani Five de Louis Jordan à qui il emprunte l’intro de Ain’t That Just Like a Woman (1946) qui deviendra sa signature : on la retrouvera note pour note sur Johnny B. Goode12. L’influence de T-Bone Walker sera également décisive. On retrouvera ses phrases de guitare dans quasiment tous les rocks de Chuck Berry.

Le 13 juin 1952, son ami Tommy Stevens (qui l’avait accompagné au collège lors de sa toute première scène) lui propose de venir chanter tous les samedis soirs. Il se chargera de l’accompagner avec son trio de blues. Ils jouent du Muddy Waters, Joe Turner, Elmore James et son idole Nat «?King?» Cole. Chuck n’hésite pas à inclure dans son répertoire des morceaux de hillbilly, un mélange noir-blanc très inhabituel qui surprend beaucoup. Melody, deuxième fille de Chuck, naît le 1er novembre 1952. À partir de novembre, le groupe remplit Huff’s Garden chaque semaine. Leur salaire double et ils sont engagés le vendredi en plus. Le 30 décembre, le pianiste Johnnie Johnson appelle Chuck pour qu’il remplace son chanteur au pied levé à la Saint-Sylvestre pour un enga-gement au Cosmopolitan Club. Le patron décide de garder Chuck et au bout de quelques semaines, le groupe remplit le vaste Cosmo (avec Ebby Hardy à la batterie et différents bassistes). Afin d’élargir son public Chuck mélange sciemment les répertoires de ses grandes influences Nat «?King?» Cole (qui plaît à tout le monde), le hillbilly (country & western) très populaire chez les Blancs et le blues (surtout Muddy Waters) apprécié par son public noir. Il reprend aussi du Harry Belafonte13. Ce style original vise le grand public avec succès, et attire de plus en plus de jeunes Blancs, un fait inhabituel. Chuck change son nom en Berryn pour que l’on ne sache pas qu’il est le fils de Henry Berry, chanteur de gospel bien connu et directeur d’un temple. Son seul rival «?noir?» sérieux à St. Louis est le groupe d’Ike Turner, et bientôt Albert King. Il invente de nouveaux couplets humoristiques qu’il ajoute aux morceaux qu’il reprend et achète un station wagon Ford Esquire rouge vif, sa première voiture neuve. Il joue désormais au-delà de St. Louis.

Maybellene

Le rock est si bon avec moi. Le rock c’est mon enfant et mon grand-père.

— Chuck Berry

En mai 1954, avec un vieux copain de classe Chuck Berry conduit jusqu’à Chicago afin de voir Howlin’ Wolf, Elmore James sur scène et sa grande inspiration, Muddy Waters. Après le concert, son idole Muddy lui recommande le producteur Leonard Chess. Le directeur des disques Chess (qui produisait déjà les disques de Bo Diddley14, Muddy Waters et Little Walter) lui demande une maquette de ses compositions. Chuck rentre à St. Louis, persuadé de tenir sa chance. Il écrit et enregistre sur son petit matériel quatre de ses chansons, dont une dérivée de Ida Red, une chanson de hillbilly traditionnelle entendue dans son enfance (et sans doute adaptée d’une version country boogie de Bob Wills15). En août 1954 Chuck participe aussi à une séance de studio peu connue de Joe Alexander and the Cubans. La face A du 45 tours «?Oh Maria?» est un calypso où la guitare a peu d’intérêt — mais la face B I Hope This Words Will Find You Well, où Chuck joue un solo, est incluse ici. Leonard Chess apprécie la bande envoyée par Chuck. Il aime particulièrement l’idée d’une chanson country chantée par un Afro-américain et lui propose une séance d’enregistrement en mai 1955. C’est à sa suggestion que Chuck renomme Maybellene sa chanson dérivée de «?Ida Red?». Les paroles racontent comment il poursuit une fille conduisant une Cadillac. Le solo est très influencé par celui de Carl Hogan sur le Ain’t That Just Like a Woman de Louis Jordan. Son groupe est augmenté de Willie Dixon à la contrebasse et de Jerome Green, percussionniste de Bo Diddley. Trente-cinq prises seront nécessaires pour satisfaire Leonard Chess, qui à l’avenir interviendra à chaque séance de façon significative et réfléchie, apportant toujours à Chuck Berry un encadrement efficace et nécessaire. Chuck joue au Cosmo trois soirs par semaine, continue les réparations avec son père et étudie la coiffure un jour par semaine. Il sera un temps coiffeur. Mais en juillet 1955, avec la promotion du disc jockey Alan Freed (qui touchera un tiers des droits, et Russ DeFratto un autre tiers) l’irrésistible Maybellene est un gros succès et Chess lui envoie un agent garantissant 40.000 dollars par an en cachets. Chuck cesse son job de menuisier. Quelques jours plus tard, il joue devant sept mille personnes à New York. Si l’on excepte son incarcération de février 1962 à octobre 1963 pour relations sexuelles avec une serveuse apache mineure, Chuck Berry restera au sommet jusqu’en 1972, devenant notamment la première des influences sur la vague de rock anglais qui dominera les années 1960.

Johnny B. Goode

Son conte de fée lui inspirera Johnny B. Goode, l’histoire d’un petit guitariste de province dont le nom «?apparaît en lettres de lumière?» comme l’avait prédit sa mère. Dans ses chansons Chuck Berry mettra en scène son propre vécu avec candeur et humour. Il racontera tout en détail dans son autobiographie16 et ira jusqu’à mettre en scène son propre mythe en énumérant les titres de ses morceaux dans Oh Yeah. Inspiré par la mode des chansons sur les voitures «?hot rod?» du début des années 1950, il signera plusieurs classiques sur le thème de l’automobile, récurrent dans la musique populaire américaine, comme l’excellent No Money Down ou County Line17. Mais depuis ses premiers concerts au Cosmo, sa motivation principale sera toujours de plaire au public, de toucher le plus grand nombre, se concentrant sur les goûts du public adolescent (il a 30 ans en 1956). Il sera aussi responsable d’un certain nombre de plagiats : son Blues for Hawaiians est par exemple entièrement repris de l’instrumental «?Floyd’s Guitar Blues?» de l’orchestre d’Andy Kirk and his Clouds of Joy, premier succès d’un instrumental à la guitare électrique de l’histoire (avec Floyd Smith à la pedal steel guitar) en mai 1939. La version originale de «?Floyd’s Guitar Blues?» est disponible sur Electric Guitar Story 1935-1962 (FA 5421) dans cette collection.

Au-delà de l’argent et de sa collection de voitures, son plus grand bonheur restera sans doute d’avoir obtenu le respect du grand public blanc comme noir à une époque où bien des gens considéraient les Noirs comme des êtres inférieurs, des animaux juste bons à être exploités. Équipé de ses Gibson ES-350TN puis ES-335 Berry a aussi révolutionné la guitare électrique avec des solos magistraux comme celui de The Man and the Donkey (une chanson dérivée de «?Junco Partner?»18). Il sera copié par tous ses contemporains, et ses trucs de scène, comme son «?duck walk?» et plusieurs tours et astuces scéniques souvent empruntés à T-Bone Walker seront immortalisés dans plusieurs films. Il saura aussi triompher des imprésarios malhonnêtes (atypique, il deviendra son propre manager dès 1955) et parviendra même à résister, dans les limites du possible, aux manipulations de Leonard Chess qui le dépossèdera d’une partie substantielle de ses droits d’auteur (éditions) en lui faisant signer des contrats qu’il ne comprenait pas. Chuck Berry fera finalement modifier des contrats à son avantage et tiendra lui-même ses comptes : il était premier en calcul à l’école. Toujours pragmatique et décidé à ne jamais retourner travailler avec son père, il imposera son style économe en tournée — qui tranche avec celui de la plupart des autres musiciens, dépensiers et sans souci du lendemain. Ne supportant plus l’alcoolisme, les retards et comportements sur scène de Johnnie Johnson et Ebby Hardy, dès 1957 il se présentera le plus souvent seul aux concerts, laissant le soin aux organisateurs de fournir les musiciens et le matériel. Sa carrière internationale commencera à l’été 1957 avec le succès de School Days en Angleterre : ses enregistrements inclus ici comptent parmi les plus influents et les plus importants du XXe siècle.

Bruno BLUM

© FRÉMEAUX & ASSOCIÉS 2013

1. Lire le livret et écouter dans cette collection l’anthologie Road Songs - Car Tunes Classics 1942 - 1962 (FA5401), où l’on retrouve cinq titres de Chuck Berry. Tous nos livrets sont en ligne sur Fremeaux.com.

2. Lire le livret de Gérard Herzaft et écouter l’anthologie Tampa Red - Slide Guitar Wizard 1931-1946 (FA 257) dans cette collection.

3. Lire le livret de Gérard Herzaft (en ligne sur fremeaux.com) et écouter l’anthologie consacrée à Lonnie Johnson (FA 262) dans cette collection.

4. Lire les livrets de Gérard Herzaft (en ligne sur fremeaux.com) et écouter les deux anthologies consacrées à Muddy Waters (FA 266 et FA 273) dans cette collection.

5. L’œuvre intégrale de Sister Rosetta Tharpe est disponible chez Frémeaux et Associés.

6. Lire le livret et écouter The Indispensable James Brown 1956-1961 (FA 5378) dans cette collection.

7. Lire le livret d’Alain Gerber et écouter Charlie Christian 1939-1941 - The Quintessence (FA 228) dans cette collection.

8. Lire le livret de Gérard Herzaft et écouter T-Bone Walker 1929-1950 - Father of Modern Blues Guitar (FA 267) dans cette collection.

9. Lire le livret d’Alain Gerber et écouter les deux volumes Nat King Cole - The Quintessence (FA 208 et FA 227) dans cette collection.

10. Retrouvez le Blazer’s Boogie de Charles Brown sur Boogie Woogie Piano 2 (FA 5164) dans cette collection.

11. Retrouvez cinq titres de Louis Jordan (et deux de T-Bone Walker) dans l’anthologie Jamaica-USA - Roots of Ska 1942-1962 (FA 5396) dans cette collection.

12. La version originale de Ain’t That Just Like a Woman par Louis Jordan & his Tympani Five est incluse dans l’anthologie Electric Guitar Story 1935-1962 (FA5421) dans cette collection.

13. Lire le livret et écouter Harry Belafonte - Calypso Mento Folk 1954-1957 (FA 5234) dans cette collection. Chuck Berry enregistrera son Jamaica Farewell dans les années 1960.

14. Lire les livrets et écouter nos deux anthologies The Indispensable Bo Diddley (FA 5376 et FA5406) dans cette collection.

15. La version boogie de «Ida Red» enregistrée en 1946 est incluse sur l’album Bob Wills and his Texas Playboys 1932-1947 (FA 164) dans cette collection.

16. Chuck Berry, The Autobiography, Harmony Books, New York, 1987.

17. Lire le livret et écouter le triple Road Songs - Car Tune Classics 1944-1962 (FA 5401) dans cette collection.

18. La version originale de «Junco Partner», un morceau rendu célèbre par The Clash, est incluse sur The Roots of Punk Rock Music 1926-1962 (FA5415) dans cette collection.

Chuck Berry

The Indispensable 1954-1961

By Bruno Blum

There’s only one true king of rock ‘n’ roll. His name is Chuck Berry.

— Stevie WONDER

The Indispensable Chuck Berry

Chuck Berry is probably the most important rock musician in history. He remains perhaps the greatest singer-songwriter in the genre, one of its greatest stage-entertainers, and no doubt one of rock’s greatest guitarists, an instrument with which, more than any other, Berry contributed to defining the very shape of the rock style. In nourishing the American Dream of his age with image-filled songs, Berry is one of those who transformed the primeval rock of Louis Jordan, Tiny Bradshaw, Ike Turner and Roy Brown into a formula that was capable of reaching a white audience – or, in other words, the masses.

Call it what you may: jive, jazz, jump, swing, soul, rhythm, rock, or even punk, it’s still boogie as far as I’m connected with it […] When it’s boogie, but with an alien title, the connection is still boogie and my kind of music.

— Chuck Berry

Deliberately conceived for seduction, and with a mind to discover the universal language of rock, Berry’s compositions have been recorded by the greatest artists from Count Basie to Wyclef Jean via Elvis Presley, The Rolling Stones, The Beatles, Jimi Hendrix, Peter Tosh, The Ramones, Sex Pistols and Creedence Clearwater Revival. Berry will always be a central figure of the first, classic rock with all its associated images: pin-ups, juke-boxes, vinyl singles, vintage electric guitars, rock radio and flirting at drive-ins in convertibles with bench-seats. Just take a look at the Walt Disney/Pixar hit movie Cars by John Lasseter & Joe Ranft (2006), where you can hear Chuck playing Route 66.1 The original recordings of many of his classic songs like Roll over Beethoven or Maybellene remain unsurpassed to this day, and this set contains almost every piece recorded by Chuck before his second jail-sentence, which severed his career in 1962.

Brown Eyed Handsome Man

The best white rockers of the Fifties – Gene Vincent, Eddie Cochran, Buddy Holly, Elvis Presley or Jerry Lee Lewis among them – were basically country singers who “sang black” to try and communicate a vocal emotion which had hitherto remained the province of gospel music and the blues. But Chuck Berry was a mirror returning the opposite image: he filtered country music with a rhythm and blues feel.

In dominating rock, which conquered Fifties’ youth and brought down racial barriers in a deeply subversive manner, Berry also represents – perhaps more than any other – the – notion of revenge: the artistic triumph as an Afro-American in the cruel years of segregation, from which he often suffered. In his native St. Louis, the rear seats in trams were reserved for “colored” people. In his masterpiece Roll Over Beethoven, which he dedicated to this music, the impertinent Chuck Berry – far from the submissive “Uncle Tom” character – laughingly sings that Beethoven must have turned in his grave when he learned how successful rhythm and blues had become – an ironical understatement really meaning that Afro-American music had become even more popular than “white” music in the classical, written tradition.

You know my temperature is rising / The juke-box’s blowing a fuse / My heart’s beatin’ rhythm and my soul is singing the blues / Roll over, Beethoven, and tell Tchaikovsky the news.

— Chuck Berry, Roll Over Beethoven, 1956

Chuck also alludes to the same theme in Rockin’ at the Philharmonic, and in Brown Eyed Handsome Man the “judge’s wife” calls up the D.A. to plead for the release of a black man who has seduced a white woman, which is Chuck’s reference to the lynching that was a commonplace in Missouri, and often the result of interracial sex between (black) males and (white, consenting) females. His own father had constantly warned him against any “lack of respect” or advance made to a white woman, on the grounds that he might have to play dearly for it. Africa is present here in the form of the Latin-Caribbean influences heard notably in Havana Moon (derived from Nat “King” Cole’s “Calypso Blues”) and La Jaunda, but also in Jo Jo Gunne, an adaptation of Cab Calloway’s “Jungle King” or Willie Dixon’s “Signifying Monkey”, both based on a Yoruba tale (which he heard in prison). The latter two and their story can be found in the boxed set Africa in America 1926-1962 (FA 5397).

One of Chuck Berry’s four great-grandmothers was born to a married couple comprising a slave of African origin, Isaac Banks, and a Chihuahua Indian cook from Oklahoma. Charles Banks, one of their seven children, became Chuck’s maternal grandfather, and it was in Oklahoma that he met Lula Thomas, the daughter of a white Englishwoman and a man of African origins, employed as a cook on one of the luxury-trains crossing the continent. Born in 1867, Lula was light-skinned and also the first child in the family to be born after the abolition of slavery. She and her husband also had seven children, and her second daughter Martha was Chuck’s mother. On his father’s side, his grandfather William Berry was born to an Oklahoma Indian and a female African slave, and William turned out to be a notoriously unfaithful ladies’ man. His wife Lucinda died when their son Henry was twelve, and so Henry (Chuck’s father) was raised by his maternal grandparents Charles and Lula. Henry never forgot his father was a woman-chaser – he was always travelling – and, no doubt as a consequence, he ensured his six children received a strict, religious education… including his son Charles Edward Anderson “Chuck” Berry, born at 6.59 a.m. on October 18th 1926 at 2520 Goode Avenue, St. Louis, Missouri.

Worried Life Blues

Negro spirituals and gospel songs lulled young Charles in his cradle: the choir at the local Baptist church in the black district of St. Louis – his parents were members – rehearsed at his home, and the Berry family, although poor, were a tightly-knit unit and used to sing harmony at the slightest opportunity, even when they weren’t attending church. Chuck’s father, Henry, was an administrator at the Antioch Church for 36 years, and he worked full-time at an industrial mill, then part time throughout the long economic crisis of the twenties. He made ends meet also working as a handyman, taking out trash, painting, doing carpentry and other repair-jobs… his wage was way below the union rate paid to white workers. Chuck shared his bed at home head-to-toe with two other children, and was soon earning a few cents selling fruit and vegetables in the streets, singing out the names of all his wares. Soon he was helping his father as a labourer; he dreamed about driving a truck.

The family sitting-room had a big Victrola radio (and later a Philco in 1929), and some evenings the Berry kids were allowed to listen to Fats Waller, Bing Crosby or Louis Armstrong – which made a change from the religious music they heard so much of the time. Charles liked country music as well as boogie-woogie and his eldest sister Lucy, like their mother, played piano all day long. She sang passionate gospel songs and pop standards, and Charles used to fight to get to the piano first. His favourites were dance records like Big Maceo’s Worried Life Blues, “Going Down Slow” by St. Louis Jimmy, Bea Boo’s “C.C. Rider”, Ella Fitzgerald singing “A Ticket a Tasket”, and many others, but his sister just kept on singing “Ave Maria” and “God Bless America”. Charles adored Tampa Red – in 1960 he recorded Don’t You Lie to Me2 – Lonnie Johnson3, Arthur Crudup, Muddy Waters4 or Rosetta Tharpe5 — all guitar-players – and the great blues singer Lil Green. His brothers and sisters preferred the big bands of Duke Ellington, Tommy Dorsey and Count Basie. When his prayers weren’t heard, Charles began to have serious doubts over the religion he was steeped in, but nevertheless joined The Jubilee Ensembles, a spirituals & gospel vocal group in which he stood out thanks to his version of “Tempted and Tried”. In 1956 Chuck recorded Downbound Train, a piece on the theme of sobriety inspired by several well-known poems and peoples’ faith. Berry describes the train to hell (as opposed to the train to paradise known to several spirituals) taken by an alcoholic… Note that Berry himself, after trying marihuana, tobacco and alcohol, was quick to give them all up, which might explain his ripe old age (he’s in his 87th year at the time of writing). He always preferred women.

Sweet Little Sixteen

A well-ordered life seemed less and less interesting to Charles Berry: he thought it was a scam, and would later sing about it in Too Much Monkey Business. He took a job at a grocery store after school so he could make enough to get his junk bicycle back on the road. He also bought himself a hip, loose-fitting drape suit… and then got caught stealing eggs from the store. He used to hang out close to a juke-box, dreaming of female conquests; they would appear later in several songs, like Sweet Little Sixteen, with its pretty little autograph-huntress who reverts to a serious student the next morning.

If one thing was taboo in the Berry family, it was sex before marriage, but the boy was precocious and a ladies’ man. He was fifteen in 1941 when his father gave him a lashing with his razor strop because he’d slept with a neighbour’s daughter – the neighbour was a deacon – and Charles, in and out of love, endured that same punishment more than once. The humiliation and suffering eventually drove him away from religion, and away from his own family. Something broke inside. He used to take his bike and hang out with Skip and James, friends of his own age, and soon trouble came his way: gasoline was scarce in wartime, and at night Charles and his pals used to siphon cans of gas from parked cars and sell it for cash. One day he was witness to an attack on a drunk; he hated alcohol and saw the incident as something the drunk had brought on himself. A pragmatic and rational thinker, when Charles was left to his own devices he took an interest in photography, science, and then taught himself to play the guitar.

Music is science. Everything is science. Because science is truth.

— Chuck Berry

He decided to take part in a school show, and dared to sing Confessin’ the Blues, the latest hit by Kansas City pianist Jay McShann. He knew that young people liked the song, and wanted to give the audience something they wanted to hear, rather than the stilted pieces that were usually part of the proceedings. He sang to thunderous applause, and decided there and then to work hard on his guitar, realizing that most of the songs he liked were playable even if you only knew a few chords. A school-friend loaned him a tenor guitar (four strings). In the evenings, Charles worked for a radio repairman, fiddling with electronics – it became a passion – and then got a job as a DJ, playing jazz and “rhythm” records. He earned enough to buy his first automobile, a (second-hand) 1934-model Ford V-8, and he made a habit of buying and selling various models; it made him a star before he even left high-school. Dealing cars formed the theme of No Money Down, and in the songs School Day and Almost Grown Chuck could express the feeling of freedom which rock ‘n’ roll and romance could give to teenagers as a release from schooling.

Blue Feeling

Aged 17 in 1944, Charles wasn’t drafted into the war and became a playboy. A further setback in his love-life (this time with a lesbian) was a traumatic experience and, returning to his old comrades Skip and James, Chuck found himself a delinquent again. This time they decided to take a drive in Chuck’s car, and when they ran out of gas and money in Kansas City, Skip pulled a gun on a store-owner. And then another. Charles copied him – with a .22 pistol that wouldn’t fire – and almost got killed at a barber-shop because the barber had a gun too. Skip held up a few other stores and they decided to go back to St. Louis. The car broke down on the highway and the teenagers pulled their gun on a driver who’d pulled over to help them. They stole his car, towing Charles’ Oldsmobile along behind them. The luckless driver called the police, and the cops gave chase; the song Jaguar and the Thunderbird tells of a chase in which the cops didn’t catch up with them, but that was fiction: Charles and the others were caught, and after a trial lasting only twenty minutes Mr. Charles Berry was sentenced to ten years in jail for armed robbery. The three accomplices were sent down to serve their sentence at Algoa Prison near Jefferson, Missouri. Chuck joined a boogie-woogie group and then, like James Brown shortly after him6, a gospel vocal-harmony group. It was no doubt during this period that Chuck, isolated in a dormitory that he repainted himself, wrote a few of his masterful blues pieces like Wee Wee Hours (inspired by Joe Turner’s “Wee Baby Blues”). After a new incredible love-affair reminiscent of Brown Eyed Handsome Man – this time with the (white) wife of the warden, although the affair wasn’t consummated – Chuck’s sentence was reduced and he was freed after three years on October 18th 1947. It was his 21st birthday.

Together We Will Always Be

Charles became “Chuck” after his brother Henry gave him the nickname when he came back from the war in the Pacific. Once out of jail, the ex-amateur stick-up specialist went back to carpentry, repairs for his father, and the guitar. He’d had time in prison to take inventory of his teenage exploits and they became the subject-matter of his songs. Chuck’s idea of a happy new existence was taking girls for a car-ride, listening to the radio and letting the wind of freedom blow through his hair. This was exactly what his masterpiece You Can’t Catch Me was all about, and it compared his automobile to an aeroplane. Every piece he wrote, or almost, revolved around this desire to relive the intimacy and magic of his lost adolescence, as in Back in the USA or Carol included here. In less than six months Chuck Berry had saved enough to buy a sumptuous black Buick Roadmaster and return to life as a seducer. Handsome, strong, intelligent and witty, he seduced Themetta “Toddy” Suggs with a ride in his Buick. They married on October 28th 1948 and set up home in the little beauty salon she opened. He sang about redemption and revenge in Together We Will Always Be, a hymn to merit and effort: “Nothing beats a failure like a try / there’s a great reward.” Chuck wasn’t faithful even if he was married, and an affair with a white woman got him into trouble with the (racist) police. He had to lie to them to avoid a beating, if not a lynching, and swore never to date a white woman again (he didn’t keep his word). The Berry couple worked hard and bought a house in 1949, renting out three rooms. Their daughter Ingrid was born on October 3rd 1950.

Rock and Roll Music

Chuck joined the musicians’ union – without a union card he couldn’t play in public – and practised his singing in a bar for whites, accompanying himself on guitar. He worked as a doorman at radio WEW and bought his first second-hand electric guitar from a gospel musician. In summer 1951 he also acquired a little tape-recorder and began recording his first attempts. He learned the essentials of his guitar-style with Ira Harris, a jazz player strongly influenced by Charlie Christian7. Chuck bought a teach-yourself music book and listened assiduously to T-Bone Walker8, Buddy Johnson, Nat “King” Cole9, Charles Brown10 (listen to his version of the latter’s Driftin’ Blues) and Louis Jordan11. Chuck showed special admiration for Carl Hogan, who played guitar with Louis Jordan’s Tympani Five; he borrowed Carl’s introduction on the 1946 tune Ain’t That Just Like a Woman and made it his signature-tune (you can hear it played note for note in Johnny B. Goode12.) T-Bone Walker also had a decisive influence on him, and you can find Walker phrases in almost all of Chuck Berry’s rock tunes.

On June 13th 1952, his friend Tommy Stevens (who’d accompanied Chuck on his first stage-appearance in high-school) asked him if he’d like to go and sing with his blues trio on Saturday nights. They played numbers by Muddy Waters, Joe Turner, Elmore James and his idol Nat “King” Cole. Chuck put a number of hillbilly pieces into his repertoire, and the unusual black/white musical mixture surprised (and pleased) a lot of people. From November that year, the group played to a full house at Huff’s Garden every week. Their salary doubled, and then they played on Fridays also. On December 30th Chuck got a call from pianist Johnnie Johnson offering him a job as a last-minute replacement for his own singer (a New Year’s Eve booking at the Cosmopolitan Club). The boss was so impressed that he decided to keep Chuck at the club and, after a few weeks, the group was packing them in at the vast Cosmo (with Ebby Hardy on drums and a succession of bass-players). To keep his audience growing, Chuck skilfully mixed songs from his great influence Nat “King” Cole (everybody liked Nat Cole) with hillbilly (country & western) tunes (popular with whites) and blues (Muddy Waters’ songs especially) which catered to a black audience. Chuck also picked up some things by Harry Belafonte13. His original style was a hit with the public, and Chuck began to draw white youngsters, which was quite unusual. Chuck also changed his name to Berryn, so that nobody would know his father was Henry Berry, the well-known gospel singer and church-elder. Chuck’s only serious “black” competition in St. Louis was Ike Turner and his group, and soon Albert King. He invented funny new verses which he added to the songs he covered, and soon he was able to buy himself his first new car, a bright red Ford Esquire station-wagon. By now, he was playing outside St. Louis.

Maybellene

Rock is so good to me. Rock is my child and my grandfather.

— Chuck Berry

In May 1954 Chuck Berry drove to Chicago with an old school-friend to see Howlin’ Wolf and Elmore James onstage with his great inspiration Muddy Waters. After the concert, his idol Muddy recommended producer Leonard Chess to him. Chess already produced the records of Bo Diddley14, Muddy Waters and Little Walter, and asked Chuck for a demo of his songs. Chuck went home to St. Louis convinced that he had a chance, and recorded four of the songs he’d written on his little tape-deck at home. One of them was derived from Ida Red, a traditional hillbilly song he’d heard as a child (and probably adapted from a country boogie version by Bob Wills15). In August 1954 Chuck also took part in a little-known studio-session by Joe Alexander and the Cubans. The A-side of the single “Oh Maria” was a calypso – the guitar wasn’t that interesting – but the B-side was I Hope These Words Will Find You Well, where Chuck plays a solo, and you can listen to it here. Leonard Chess liked the tape Chuck sent him, and he also liked the idea of a country song sung by an Afro-American, so he offered Chuck a record-session in May 1955. It was Leonard Chess who suggested to Chuck that the song adapted from “Ida Red” should be renamed Maybellene (the lyrics relate his pursuit of a girl driving a Cadillac). Chuck’s solo is highly influenced by Carl Hogan’s playing on Louis Jordan’s version of Ain’t That Just Like a Woman. His group is supplemented by Willie Dixon on double bass together with Bo Diddley’s maracas player Jerome Green. It took thirty-five takes (35!) to satisfy Leonard Chess, who from then on supervised every session very closely, thinking hard over each take and always providing Chuck with efficient support. By now, Chuck was playing at the Cosmo three days a week, still working on repair-jobs with his father, and also learning how to cut hair (one day a week). He was a hair-dresser for a time. But in July 1955, thanks to the promotion it received from disc jockey Alan Freed (who received a third of its royalties) and Russ DeFratto (another third as a percentage), the irresistibly catchy Maybellene was an enormous hit, and Chess sent Chuck an agent who guaranteed he would earn some 40.000 dollars a year in fees. Chuck quit his job as a carpenter. A few days later, he was playing for an audience of 7.000 fans in New York. Apart from his jail-term from February 1962 to October 1963 (a sentence for having sex with an under-age Apache waitress), Chuck Berry stayed at the top until 1972, and became the first major influence on the British “rock wave” which dominated the Sixties.

Johnny B. Goode

Chuck’s fairy-tale story inspired him to write Johnny B. Goode, the story of a little country-boy guitar-player whose name “appears in lights” just as his mother predicted. Chuck Berry staged his own life in his songs, candidly and with humour. He would put much more detail into his autobiography16 and even went so far as to make reference to his own legend when he enumerated the titles of his songs in Oh Yeah. Inspired by the songs that became fashionable when hot-rods were a fad in the early Fifties, he wrote several classics around the theme of the automobile – it’s recurrent in American pop – like the excellent No Money Down or County Line17. But ever since his first appearances at the Cosmo, Chuck’s main motivation was to please an audience all the time, to reach the largest number of people possible, concentrating on younger people – he was 30 in 1956. He was also responsible for a certain amount of plagiarism: his Blues for Hawaiians, for example, was copied in toto from the instrumental Floyd’s Guitar Blues by Andy Kirk and his “Clouds of Joy” Orchestra, the first instrumental hit with an electric-guitar in history (May 1939, with Floyd Smith playing pedal steel guitar) with Floyd Smith playing pedal steel guitar). Hear Floyd Smith’s original on Electric Guitar Story 1935-1962 (FA 5401) in this series.

Apart from the money – and his automobile-collection – the thing which made Chuck proudest was probably the respect he earned from white audiences in a period when a huge number of people considered blacks as their inferiors, if not just good enough to be exploited like animals. Armed with his Gibson ES-350TN guitar (and later the ES-335) Berry brought about a revolution in the guitar with solos like the one you can hear in The Man and the Donkey (a song derived from “Junco Partner”18). All his contemporaries would copy him at some point, and his stage quirks, like his famous “duck walk” and other things (often borrowed from T-Bone Walker) would be immortalized in several films. He overcame shyster impresarios (atypically becoming his own manager as early as 1955), and even succeeded in resisting (mostly) the manoeuvres of Leonard Chess, who still managed to deprive him of a substantial part of his publishing-rights by making him sign contracts he didn’t understand. But Chuck Berry finally had them changed to his advantage and began taking care of his own finances (he was, after all, top of the class in maths at school). Ever the pragmatist, and determined not to return to work with his father, Chuck imposed his economic style whenever he went on tour, which was quite unlike anything any of his spendthrift musicians had ever seen before. By 1957, Chuck had had enough of Johnnie Johnson and Ebby Hardy, who were always late and/or drunk onstage, and he often turned up alone at concerts, letting the promoters supply the musicians and equipment. His international career would begin in the summer of 1957, when School Days was a hit in Britain. The music included here ranks among some of the most important records of the 20th century..

Bruno BLUM

Adapted into English by : Martin DAVIES

© FRÉMEAUX & ASSOCIÉS 2013

1. Cf. the anthology Road Songs - Car Tune Classics 1942 - 1962 (FA5401), which has five Chuck Berry titles. All the booklets in this series are online at www.fremeaux.com.

2. Cf. Gérard Herzhaft’s booklet and anthology Tampa Red - Slide Guitar Wizard 1931-1946 (FA 257).

3. Id. The Lonnie Johnson anthology (FA 262).

4. Id. Both Muddy Waters albums (FA 266, FA 273).

5. The complete recordings of Sister Rosetta Tharpe are available from Frémeaux & Associés.

6. Cf. The Indispensable James Brown 1956-1961 (FA 5378).

7. Cf. Alain Gerber’s notes and the recordings in Charlie Christian 1939-1941 - The Quintessence (FA 228).

8. Cf. Gérard Herzhaft’s notes and the recordings in T-Bone Walker 1929-1950 - Father of Modern Blues Guitar (FA 267).

9. Cf. both volumes of Nat King Cole - The Quintessence (FA 208 & FA 227).

10. Hear Blazer’s Boogie by Charles Brown on Boogie Woogie Piano 2 (FA 5164).

11. Five Louis Jordan titles (and two by T-Bone Walker) feature in the Jamaica-USA - Roots of Ska 1942-1962 anthology (FA 5396).

12. The original version of Ain’t That Just Like a Woman by Louis Jordan & his Tympani Five is included in Electric Guitar Story 1935-1962 (FA5421).

13. Cf. Harry Belafonte - Calypso Mento Folk 1954-1957 (FA 5234). Chuck Berry recorded his Jamaica Farewell in the Sixties.

14. Cf. both anthologies devoted to The Indispensable Bo Diddley (FA 5376 & FA5426).

15. The boogie version of “Ida Red” recorded in 1946 is included in Bob Wills and his Texas Playboys 1932-1947 (FA 164).

16. The Autobiography, Harmony Books, New York, 1987.

17. Cf. the triple set Road Songs - Car Tune Classics 1944-1962 (FA 5401).

18. The original version of “Junco Partner”, a piece made famous by The Clash, features in The Roots of Punk Rock Music 1926-1962 (FA5415).

Chuck Berry The Indispensable 1954-1961

All compositions by Charles Edward Anderson Berry aka Chuck Berry except:

Maybellene (Charles Edward Anderson Berry aka Chuck Berry, Russ Fratto, Alan Freed) Note: Maybellene was derived from the traditional song Ida Red.

Worried Life Blues (Maceo Merriweather aka Big Maceo)

Floyd’s Guitar Blues as Blues for Hawaiians (Floyd Smith)

Down the Road Apiece (Donald MacRae Wilhoite aka Don Raye)

Confessin’ the Blues (Walter Brown, Jay McShann)

Mad Lad (B. B. Davis)

Broken Arrow (E. Anderson)

Driftin’ Blues (Charles Brown, Edward Williams, John Moore)

Route 66 (Robert Troup aka Bobby Troup)

Sweet Sixteen (Ahmet Ertegun as A. Nugetre)

Run Rudolph Run (Charles Edward Anderson Berry aka Chuck Berry, John Marks, Marvin Brodie)

I Hope These Words Will Find You Well (Oscar Washington)

Merry Christmas Baby (Lou Baxter,

Johnny Moore)

Recordings produced by Lejzor Czyz

as Leonard Chess and Fiszel Czyz

as Phil Chess.

Discographie 1

1. Maybellene

2. Wee Wee Hours

Charles Edward Anderson Berry as Chuck Berry-g, v; Johnnie Clyde Johnson as Johnnie Johnson-p; Willie Dixon-b; Jasper Thomas-d; Jerome Green-mrcs. Produced by Lejzor Czyz as Leonard Chess and Fiszel Czyz as Phil Chess, Chicago, May 21, 1955

3. THirty Days

4. Together We Will Always Be

Charles Edward Anderson Berry as Chuck Berry-g, v; Johnnie Clyde Johnson as Johnnie Johnson-p; Willie Dixon-b; Jasper Thomas-d; Jerome Green-mrcs. Produced by Lejzor Czyz as Leonard Chess and Fiszel Czyz as Phil Chess, Chicago, September, 1955

5. You Can’t Catch Me

6. Downbound Train

7. No Money Down

8. Roly Poly (inst.)

9. Berry Pickin’ (inst.)

Charles Edward Berry as Chuck Berry-g, v; Otis Spann-p; Willie Dixon-b; Ebby Hardy-d. Produced by Lejzor Czyz as Leonard Chess, Chicago, December 20, 1955.

10. Drifting heart

11. Brown Eyed Handsome Man

12. Roll Over Beethoven

13. Too Much Monkey Business

Charles Edward Anderson Berry as Chuck Berry-g, v; Johnnie Johnson-p; Willie Dixon-b; Fred Below-d. L.C. Davis-ts on 10 & 13. Produced by Lejzor Czyz as Leonard Chess and Fiszel Czyz as Phil Chess, Chicago, April 16, 1956.

14. Havana Moon

Charles Edward Anderson Berry as Chuck Berry-g, v; Johnnie Clyde Johnson as Johnnie Johnson-p; Jimmy Rogers-g; Willie Dixon-b; Fred Below-d. Produced by Lejzor Czyz as Leonard Chess, Chicago, circa October 1956.

15. School Day (Ring Ring Goes the Bell)

16. La Jaunda

17. Blue Feeling (Low Feeling = slowed down - One Dozen) (inst.)

Charles Edward Anderson Berry as Chuck Berry-g, v; unknown-g; Johnnie Clyde Johnson as Johnnie Johnson-p; Willie Dixon-b; Fred Below, d, bongos on 18. Produced by Lejzor Czyz as Leonard Chess and Fiszel Czyz as Phil Chess, Chicago, December, 1956.

18. How You’ve Changed

19. Rock and Roll Music

20. I’ve Changed

21. Oh Baby Doll

Charles Edward Anderson Berry as Chuck Berry-g, v; Lafayette Leake-p; Willie Dixon-b; Fred Below, d. Produced by Lejzor Czyz and Fiszel Czyz as Phil Chess as Leonard Chess, Chicago, May 1957.

22. Rockin’ at the Philharmonic (inst.)

Same as Disc 2, tracks 1-5.

23. I Hope THese Words Will Find You Well

Joe Alexander and the Cubans: Joe Alexander-v; Charles Edward Anderson Berry aka Chuck Berry as Chuck Berryn-g; unknown congas. Possibly St. Louis, Missouri. August 13, 1954.

Discographie 2

1. Sweet Little Sixteen

2. Guitar Boogie (inst.)

3. Johnny B. Goode

4. In-go (inst.)

Charles Edward Anderson Berry as Chuck Berry-g, v; Lafayette Leake-p; Willie Dixon-b; Fred Below, d. Produced by Lejzor Czyz as Leonard Chess and Fiszel Czyz as Phil Chess, Chicago, December 29 & 30, 1957.

5. Reelin’ and Rockin’

6. Around and Around

7. It Don’t Take But a Few Minutes

8. Hey, Pedro

9. Blues for Hawaiians (Floyd’s Guitar Blues)

Charles Edward Anderson Berry as Chuck Berry-g, v, overdubs: 2nd g, electraharp guitar on 9, p, d; unknown b, possibly Berry. Produced by Lejzor Czyz as Leonard Chess and Fiszel Czyz as Phil Chess, February 28, 1958.

10. Carol

11. Oh Yeah

12. Time Was

13. House of Blue Lights

14. Beautiful Delilah

Charles Edward Anderson Berry as Chuck Berry-g, v; G. Smith-b; Johnnie Johnson-p; Ebby Hardy-d; unknown perc. Produced by Lejzor Czyz as Leonard Chess and Fiszel Czyz as Phil Chess, Chicago, Illinois, May 2, 1958.

15. Jo Jo Gunne

16. Sweet Little Rock and Roller

17. Anthony Boy

Charles Edward Anderson Berry as Chuck Berry-g, v, overdub: 2nd g; Johnnie Johnson-p; Willie Dixon-b; Fred Below-d. possibly Etta James, Harvey & the Moonglows (see track 22)-backing vocals on 15. Produced by Lejzor Czyz as Leonard Chess and Fiszel Czyz as Phil Chess, Chicago,

Illinois, September 28, 1958.

18. Memphis 2

Charles Edward Anderson Berry as Chuck Berry-g, v, b, d. Produced by Charles Edward Anderson Berry as Chuck Berry, 4221 West Easton Avenue, St. Louis, Missouri, 1958.

19. Little Queenie

20. Run Rudolph Run

21. Merry Christmas baby

Charles Edward Anderson Berry as Chuck Berry-g, v, overdub: 2nd g on 21; Johnnie Johnson-p; Willie Dixon-b; Fred Below-d. Produced by Lejzor Czyz as Leonard Chess and Fiszel Czyz as Phil Chess, Chicago, Illinois, November 1958.

22. Almost Grown

23. Back in the USA

Charles Edward Anderson Berry as Chuck Berry-g, v, overdub: 2nd g; Johnnie Johnson-p; Willie Dixon-b; Fred Below-d; Etta James- backing v; Harvey & the Moonglows: Harvey Fuqua, Marvin Gaye, James Nolan, Reese Palmer, Chuck Barksdale, Chester Simmons-backing vocals. Roquel Davis aka Billy Davis- backing vocals on 22. Produced by Lejzor Czyz as Leonard Chess and Fiszel Czyz as Phil Chess, Chicago, Illinois, February 17, 1959

Discographie 3

1. Betty Jean

2. County Line

3. Broken Arrow

4. Let It Rock

5. Too Pooped to Pop

Charles Edward Anderson Berry as Chuck Berry-g, v, overdub: 2nd g; Leroy C. Davis-ts. Johnnie Johnson-p; Willie Dixon-b; Fred Below-d; The Ecuadors: Etta James, Harvey Fuqua, Roquel Davis aka Billy Davis- backing vocals on 1. Chicago, Illinois, July 1959.

6. Don’t You Lie to Me (Hudson Woodbridge aka Hud---son Whittaker as Tampa Red 1940)

7. Drifting Blues

8. Worried Life Blues

9. Bye Bye Johnny

10. Our Little Rendez Vous

11. Run Around

12. Jaguar and the Thunderbird

13. I Got to Find my Baby

Charles Edward Anderson Berry as Chuck Berry-g, v, st g on 12; Matt Murphy aka “Guitar” Murphy-g; Leroy C. Davis-ts; Johnnie Johnson-p; Willie Dixon-b; Jaspar Thomas-d. Chicago, February 12 and/or March 29, 1960.

14. Little Star

15. Down the Road Apiece

16. Confessin’ the Blues

17. Sweet Sixteen

18. Mad Lad (inst.)

Charles Edward Anderson Berry as Chuck Berry-g, v, st g on 18; Matt Murphy aka “Guitar” Murphy-g; Leroy C. Davis-ts; Johnnie Johnson-p; Willie Dixon-b; Jaspar Thomas-d. February 15 and/or April 12, 1960.

19. Route 66

20. I’m Talking About You

Charles Edward Anderson Berry as Chuck Berry-g, v; Leroy C. Davis-ts; Johnnie Johnson-p; possibly Reggie Boyd-b; Ebby Hardt-d. Chicago, January 10 or 19, 1961.

21. Come On

22. Go Go Go

23. The Man and the Donkey

Charles Edward Anderson Berry as Chuck Berry-g, v; Johnnie Johnson-p; Reggie Boyd-b; Phil Thomas-d; Martha Berry- 2nd v. Chicago, July 29, 1961.

Grand modernisateur du rock n’ roll à la charnière des années 1950-1960, Chuck Berry est l’un des musiciens les plus influents de la musique populaire américaine du XXe siècle. Les compositions de Chuck Berry ont été jouées par les plus grands (de Count Basie aux Beatles) et sont tellement célèbres que l’on oublie parfois qu’il en reste le meilleur interprète. Bruno Blum a sélectionné le florilège de Chuck Berry entre 1954 et 1961.

Patrick FRÉMEAUX

« Il n’y a qu’un seul vrai roi du rock ‘n’ roll. Il s’appelle Chuck Berry. »

Stevie WONDER

As Rock ‘n’ Roll’s great modernizer when the Fifties turned into the Sixties, Chuck Berry was one of the most influential musicians in 20th century American pop. His compositions have been played by the greatest, from Count Basie to The Beatles, and are today so famous that people forget that Chuck’s originals were the greatest… Here, compiled by Bruno Blum, are Berry’s indispensable songs from 1954 to 1961.

Patrick FRÉMEAUX

“There’s only one true king of rock ‘n’ roll. His name is Chuck Berry.”

Stevie WONDER

CD The Indispensable Chuck Berry 1954-1961, Chuck Berry © Frémeaux & Associés 2013.