- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

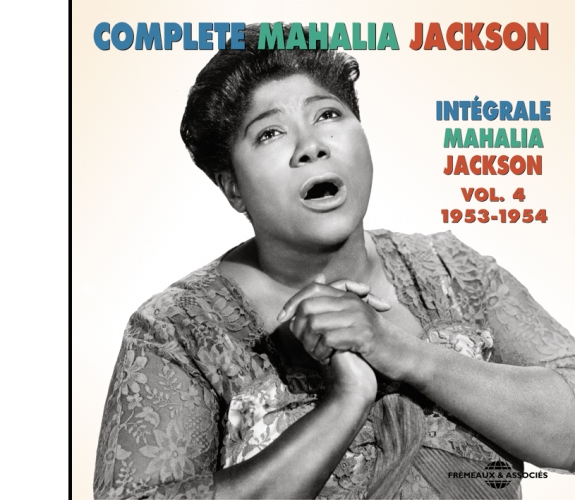

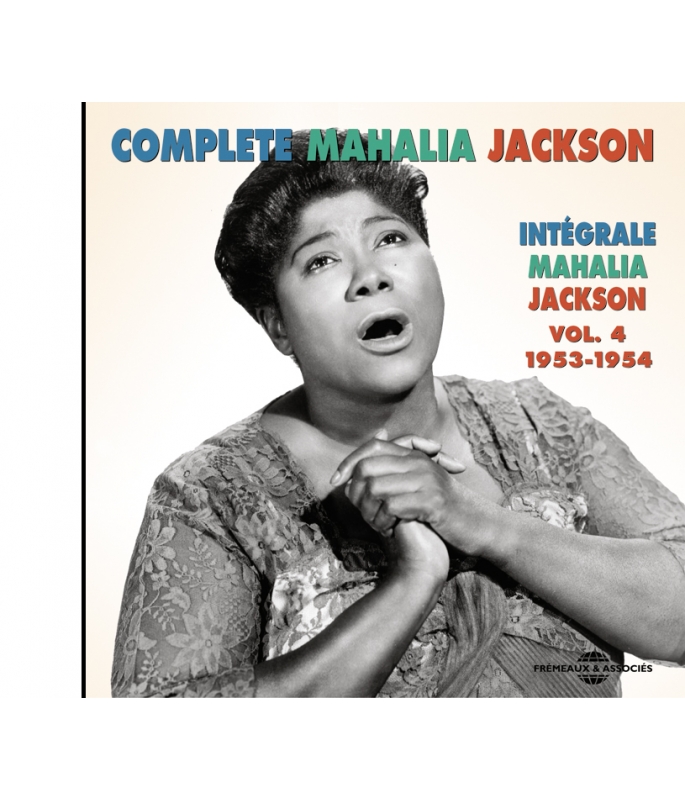

1953-1954

MAHALIA JACKSON

Ref.: FA1314

Artistic Direction : JEAN BUZELIN

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Total duration of the pack : 1 hours 1 minutes

Nbre. CD : 1

1953-1954

- - * * * * SOUL BAG

1953-1954

Before achieving world renown, Mahalia Jackson’s Apollo recordings in the early 50s reveal her at the very summit of her art.

1952-1952

1947-1950

1937-1946

INTEGRALE 1954-1955

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1I M GOING TO THE RIVERMAHALIA JACKSONB SMITH00:03:011953

-

2ONE DAYMAHALIA JACKSONK MORRIS00:02:351953

-

3I BELIEVEMAHALIA JACKSONI GRAHAM00:02:421953

-

4BEAUTIFUL TOMORROWMAHALIA JACKSONTHOMAS A DORSEY00:02:271953

-

5BEAUTIFUL TOMORROW ALTERNATE TAKEMAHALIA JACKSONTHOMAS A DORSEY00:03:091953

-

6CONSIDER MEMAHALIA JACKSONI GRAHAM00:03:381953

-

7WHAT THENMAHALIA JACKSONTHOMAS A DORSEY00:02:521953

-

8HANDS OF GODMAHALIA JACKSONLEAKE LAFAYETTE00:03:141953

-

9IT S REALMAHALIA JACKSON00:02:591953

-

10NO MATTER HOW YOU PRAYMAHALIA JACKSONFLETCHER ALLEN00:02:041953

-

11MY CATHEDRALMAHALIA JACKSONWAYNE00:03:211953

-

12WALKING TO JERUSALEM (UP IN JERUSALEM)MAHALIA JACKSON00:03:081953

-

13I WONDER IF I WILL EVER RESTMAHALIA JACKSONA HUNTER00:03:201953

-

14COME TO JESUSMAHALIA JACKSONL PAULING00:03:251953

-

15DIDN T IT RAINMAHALIA JACKSON00:01:561953

-

16(I M) ON MY WAY (TO CANAAN) ALTERNATE TAKEMAHALIA JACKSON00:03:471954

-

17(I M) ON MY WAY (TO CANAAN)MAHALIA JACKSON00:03:161954

-

18MY STORYMAHALIA JACKSONMAHALIA JACKSON00:02:571954

-

19RUN ALL THE WAY (WILLING TO RUN)MAHALIA JACKSON00:02:441954

-

20NOBODY KNOWS THE TROUBLE I VE SEENMAHALIA JACKSON00:02:391954

-

21NOBODY KNOWS THE TROUBLE I VE SEENMAHALIA JACKSON00:02:281954

COMPLETE MAHALIA JACKSON Vol.4 FA 1314

COMPLETE MAHALIA JACKSON

Vol.4 1953-1954

INTÉGRALE MAHALIA JACKSON

Au début de l’année 1953, Mahalia Jackson se remet de son hospitalisation après la maladie qui l’a conduite à abréger sa première tournée à l’automne dernier. Le grand critique et producteur John Hammond, celui qui avait organisé les concerts historiques “From Spirituals to Swing” au Carnegie Hall en 1938 et 1939, relance alors Mahalia. Grand admirateur de la chanteuse, il lui a déjà suggéré de quitter Apollo, la maison de disques dirigée par Bess Berman avec laquelle Mahalia n’a jamais eu de bonnes relations. Celles-ci ne s’arrangent pas malgré les ventes toujours confortables de ses derniers disques, en particulier Silent Night (Prix Jazz Hot en France en 1953) et In The Upper Room (1). Hammond, qui s’occupe à présent de la petite compagnie Vanguard, propose à Mitch Miller, son collègue de chez Columbia, de signer Mahalia Jackson en lui offrant un contrat de 5 ans renouvelable comprenant quatre séances d’enregistrement annuelles. Mais tout cela mérite réflexion et John Hammond reste prudent lorsqu’il téléphone à Mahalia : “Mes amis directeurs artistiques chez Columbia n’ont aucune idée de ce qu’est le gospel (…) De plus, vous risquez de perdre le meilleur public que vous n’ayez jamais eu : votre propre public noir, celui qui vient de l’Église… Vous allez vous trouver entre les mains de gens qui n’y connaissent rien. Pensez-y avant de franchir le pas.”(2)

Mais le désir de la chanteuse de pénétrer la “stratosphère” commerciale est le plus fort. Elle se trouve dans une phase ascendante et désire suivre ce que son instinct lui commande. Un contrat lui est proposé mais, toujours méfiante, elle ne le signe pas de suite. Elle enregistre, probablement en mai, toujours pour Apollo avec sa fidèle pianiste Mildred Falls, une section rythmique et un quartette vocal masculin (3) deux très beaux gospel songs puis donne un concert au Chicago Stadium devant un parterre de couleur, “son” public, d’où émergent quelques visages pâles comme ceux de son ami le journaliste Studs Terkel (4) et du chanteur Pete Seeger. Elle prend ensuite la route au sein d’un “Gospel Train” pour une longue tournée dans le Sud et le Southwest. Ses partenaires sont le fidèle James Lee (4), la chanteuse “Blind” Princess Stewart qui se fera largement connaître quelques années plus tard, en 1962, avec “Black Nativity”, le spectacle de Langston Hughes, Singing Sammy et le révérend Jodie Strawther (6). Et c’est durant ce voyage, quelque part entre la Géorgie et la Floride, que Mahalia apprend, le 1er juillet, le décès de son père Johnny Jackson à l’âge de 76 ans. Mais “le spectacle doit continuer” et la tournée se poursuit par le Texas (Little Rock, Dallas…) pour se terminer en Californie. Mahalia a emmené le fameux contrat dans ses valises et, après l’avoir bien retourné dans tous les sens, finit par le signer un soir à Oakland.

Durant cette période, elle a l’occasion de chanter en duo avec Brother Joe May, le plus grand soliste de gospel de l’époque dont on dit qu’il est l’équivalent masculin de Mahalia Jackson.En août 1953, Mahalia enregistre quatre faces avec l’excellent quartette des Melody Echoes. Dans un souci d’ouverture, deux compositions gospel de Thomas Dorsey voisinent avec deux œuvres plus “classiques”, I Believe et Consider Me qui seront éditées sous le label Lloyds orienté vers le marché pop, donc en direction d’une clientèle plutôt blanche. En septembre, Mahalia participe à une émission de la radio NBC à Miami. Elle se rend ensuite à New York et, à cette occasion, sa biographe Laurraine Goreau relate que le 4 octobre 1953 précisément, Mahalia Jackson descend pour la première fois dans un hôtel “blanc” à New York, ce qui peut paraître invraisemblable vu de ce côté-ci de l’Atlantique compte tenu de la notoriété de l’artiste ! Puis, selon un calendrier désormais bien établi, elle donne son quatrième récital annuel au Carnegie Hall, accompagnée par Mildred Falls au piano et Louise Overall Weaver à l’orgue. À ce “Gospel Jubilee”, toujours organisé par son impresario Joe Bostic (4), se produisent également, parmi d’autres chanteurs et groupes, les Dixie Hummingbirds et les Davis Sisters. Quelques jours plus tard, Mahalia Jackson attaque l’une de ses dernières sessions pour Apollo qui va se dérouler en deux temps. Sept titres sont enregistrés, les quatre premiers dans le genre “cantique”, majestueux, lents et qui, bien qu’interprétés sans emphase par la chanteuse, ne peuvent compter parmi ses réussites inoubliables, en particulier No Matter How You Pray/My Cathedral, disque également publié sous étiquette Lloyds.

La présence d’une grande chorale mixte qui chante de façon stricte et très arrangée, accentue le côté “occidental” et classique des interprétations. Par comparaison, les trois autres pièces, où l’on retrouve les Melody Echoes, dégagent une tout autre atmosphère, en particulier le lancinant I Wonder If I Will Ever Rest que souligne le battement des tambours.À la même époque paraît le premier article important que lui consacre Ebony, le plus grand magazine noir du pays. C’est enfin la rencontre avec Mitch Miller qui contresigne le fameux contrat. Mais cela ne signifie pas pour autant que les portes des studios Columbia vont s’ouvrir toutes grandes, les responsables de la maison de disques restant réservés dans la mesure où Mahalia a exigé de ne chanter que du répertoire religieux. Quant au Chicago Daily News, qui relate la nouvelle, il écrit : “Sa réputation ici dépend surtout de ses compatriotes noirs. La plupart des Blancs à Chicago ne l’ont jamais entendus.” Rappelons que Mahalia Jackson réside et se produit à Chicago depuis… 1927 !Une nouvelle grande tournée à travers le pays a lieu au printemps 1954. Mahalia Jackson est sur les routes avec Mildred Falls, James Lee et le Rev. Strawther. Ces longues et harassantes tournées, nécessaires aux chanteurs de couleur qui vont à la rencontre de leur public, révèlent cruellement les contradictions qui existent entre les concerts donnés dans le nord du pays devant un auditoire blanc respectueux et la réception hostile que les Blancs du Sud réservent aux artistes noirs chez eux : “La minute après avoir quitté la salle de concert (où elle a chanté pour les Noirs), je sens que je retourne dans la jungle”, raconte Mahalia. Elle voyage alors avec Mildred et son cousin John Stevens, un jeune comédien de Chicago qui conduit sa Cadillac bleu ciel.

“Un cauchemar ! Il n’y pas de place pour nous pour manger et pour dormir le long des grandes routes. Les restaurants ne veulent pas nous servir. Quand on sort de voiture pour acheter quelque chose à manger, les gens nous regardent de travers. Des stations-service refusent de nous servir.”(2) Ainsi que le rappelle Jules Schwerin, durant cette époque qui précède les luttes pour les droits civiques, c’était la coutume chez les artistes de recevoir en liquide le cachet de leur prestation, de rejoindre leur voiture et de filer, puis de rouler toute la nuit jusqu’à l’endroit de leur prochain concert. Il fallait souvent dormir dans l’auto si l’on ne rencontrait pas d’hôtel noir ou de gîte rural tenu par un Noir sur le trajet. Cette situation a perduré durant les premières années où Mahalia Jackson effectuait son ascension du marché musical blanc.Au retour de cette tournée, Mahalia se met à la recherche d’un nouvel organiste. En effet, ses accompagnateurs habituels, Louise Overall comme Blind Francis, ont des difficultés pour voyager. Elle entend alors parler d’un jeune organiste, Ralph Jones, qui travaille avec Prophet Powers (7) dans une petite église “boutique” de la 51e Rue.Mahalia doit encore une séance à Apollo. Durant celle-ci, qui a lieu en juin 1954, la chanteuse interprète magnifiquement des negro spirituals traditionnels. Des instruments “exotiques” sont ajoutés à la formation instrumentale habituelle, ainsi qu’un saxophone sur un morceau. Peut-être pour coller à la vogue du mambo qui secoue en ce moment le pays ? À noter deux interprétations vocales très différentes du célèbre Nobody Knows et deux versions de I’m On My Way dont l’une avec quartette vocal qui pourrait, selon Paul Jones, provenir d’une séance antérieure.Pour la tournée d’été, Ralph Jones est engagé et son association avec Mildred Falls fonctionne parfaitement.

Tous deux formeront bientôt l’ossature du Falls-Jones Ensemble qui accompagnera la chanteuse, sur ses disques Columbia comme sur scène, durant de longues années.Pendant ce temps, Mitch Miller s’est activé. Il a contacté un ami producteur à Chicago, Lou Cowan, pour lui demander d’organiser un programme radio régulier dont Mahalia serait la vedette. Quand Mahalia apprend que la station CBS cherche un rédacteur, elle pense tout de suite à Studs Terkel qui lui avait offert l’antenne dès 1947. Mais, en 1954, Terkel est indésirable à la CBS car son nom figure sur la “liste noire” de Red Channels, l’organe de presse réactionnaire qui cite complaisamment les noms des Américains “déloyaux” ou “communistes”. On connaît la triste réputation de cette liste qui, durant le maccartisme, a conduit au boycott ou à l’exil nombre d’artistes – Charlie Chaplin étant le plus célèbre. Donc, le “mauvais Américain3 Studs Terkel fait chaque jour sur une radio de Chicago des commentaires jugés dangereux pour la Nation ! Mais Mahalia insiste et la CBS accepte à condition que le nom du journaliste ne soit pas cité à l’antenne. Terkel donne son accord et le premier “Mahalia Jackson Show” a lieu le dimanche 26 septembre 1954 de 21 h 35 à 22h. Mahalia y chante I Believe, Didn’t It Rain (8), le standard You’ll Never Walk Alone et The Lord’s Prayer, accompagnée par Mildred, Ralph et un quartette blanc dirigé par Jack Halloran. Jusqu’au 6 février 1955, vingt programmes hebdomadaires seront diffusés, attirant une large audience et suscitant d’élogieux commentaires (2). On voit également la chanteuse à la télévision. Quinze jours avant cette “première”, le 11 septembre dans une atmosphère houleuse, un règlement de séparation était conclu entre les avocats de Bess Berman et ceux de Mahalia. Toujours en septembre, elle se produit à New York avec ses vieux partenaires Robert Anderson et Blind James Francis.

Elle donne son cinquième récital au Carnegie Hall et, au cours d’une soirée, rencontre Duke Ellington. Celui-ci, après le dîner, s’installe au piano et accompagne Mahalia sur The Lord’s Prayer. Quelques années plus tard, en 1958, ces deux immenses personnages de l’art musical afro-américain se retrouveront en studio pour l’enregistrement de plusieurs thèmes de la suite “Black, Brown And Beige” du Duke, seule incursion dans le monde du jazz de la chanteuse au cours d’une carrière consacrée à la musique religieuse. Mais comment ne pas assimiler ces chants écrits pour la dignité d’un peuple, aux plus beaux negro spirituals de son histoire ? Mahalia en était parfaitement consciente et ne pouvait refuser sa participation à celui qu’elle considérait comme le plus grand de tous.Notre quatrième volume de l’intégrale Mahalia Jackson s’achève donc avec la fin des enregistrements Apollo de la chanteuse. En effet, dès le 22 novembre 1954, celle-ci pousse pour la première fois les portes des studios CBS/Columbia en compagnie de Mildred Falls et de Ralph Jones. Pas moins de quatorze titres sont mis en boîte sous la direction artistique de George Avakian. Une nouvelle histoire commence pour “The World’s Greatest Gospel Singer” ainsi que la baptise la compagnie… histoire qui ne s’achèvera que peu avant la mort de la chanteuse, le 27 janvier 1972.Il demeure qu’en ce début des fifties et avec ses derniers enregistrements Apollo, la chanteuse est à son sommet. Avec sa voix forte, expressive, persuasive et bouleversante, l’étendue de son registre, son sens du placement et de la respiration innés, ses facultés de souplesse rythmique, d’improvisation et d’articulation, sa capacité à délivrer un message qui dépasse le côté affectif et émotionnel, elle provoque une réaction pénétrante chez l’auditeur. Mahalia Jackson a peut-être connu là ses plus grandes années créatrices.

Jean Buzelin

Auteur de Negro Spirituals et Gospel Songs, Chants d’espoir et de liberté (Ed. du Layeur/Notre Histoire, Paris 1998).

© FRÉMEAUX & ASSOCIÉS - GROUPE FRÉMEAUX COLOMBINI SA, 2005

Notes :

(1) Voir Complete Mahalia Jackson Vol.3 (FA 1313). À propos de In The Upper Room, le chanteur Clyde Wright nous a communiqué l’information suivante :Une première version de ce thème a été enregistrée par Mahalia Jackson en compagnie des Selah Singers dont faisait partie Clyde Wright à l’époque. Mais elle n’a jamais été publiée – sans doute est-elle perdue – et c’est la seconde version avec les Southern Harmonaires, l’autre quartette fondé par Thermon Ruth, qui a été éditée avec le succès que l’on sait. Les Selah Singers ont chanté avec Mahalia lors d’émissions de radio organisées par Joe Bostic à New York.

(2) Cité par Jules Schwerin dans God to Tell It (voir Ouvrages consultés).

(3) Il s’agit probablement des Melody Echoes qui enregistrent six titres pour Apollo sans doute le même jour (n° de matrices 2525 à 2531). Un disque sera également publié sous le nom de “Earl Ricky Wells & The Mel-o-dots” pour le marché black pop.

(4) Voir Complete Mahalia Jackson Vol.2 (FA 1312).

(5) Voir Complete Mahalia Jackson Vol.1 (FA 1311), Vol.2 et Vol.3.

(6) Ce chanteur grava quelques disques à Los Angeles à la fin des années 40 sous le nom de Brother Jodie Strawther.

(7) Prophet Powers (ou Powell) dirige une grande chorale qui a également enregistré pour Apollo.

(8) La première version de ce thème chantée par Mahalia Jackson et publiée ultérieurement par Apollo, a été enregistrée à une date inconnue, peut-être vers 1953/1954 ou même avant, sachant que Mahalia l’avait à son répertoire depuis plusieurs années. Nous avons réédité ici la version originale “brute”, et non celle artificiellement allongée (par collages de couplets répétés) qui figure dans la plupart des rééditions en CD.

Ouvrages consultés :

Laurraine Gorreau : Mahalia (Lion Pub., UK 1976 – 2e édition)

Jules Schwerin : God to Tell It :Mahalia Jackson (Oxford Universtity press, 1992)

Robert Sacré : Les Negro Spirituals et les Gospel Songs (Que-Sais-Je ?, PUF, Paris 1993)

Denis-Constant Martin : Le Gospel afro-américain (Cité de la Musique/Actes Sud, Paris 1998)

Noël Balen : Histoire du Negro spiritual et du Gospel (Fayard, Paris 2001).

Nous remercions en particulier Étienne Peltier et Robert Sacré pour le prêt de disques de leur collection ainsi que Daniel Gugolz, Bob Laughton, Per Notini et Clyde Wright pour leur collaboration.

Photos X (D.R.) et collections : Jean Buzelin, François-Xavier Moulé, Melrose Square Pub. In Mahalia Jackson.

english notes

At the beginning of 1953 Mahalia Jackson was recovering from her stay in hospital after the illness that had forced her to cut short her first tour the previous autumn. The well known critic and producer John Hammond, who had organised the legendary “From Spirituals To Swing” concerts at Carnegie Hall in 1938 and 1939, now relaunched Mahalia’s career. A great admirer of hers, he had already suggested that she leave the Apollo label, headed by Bess Berman with whom Mahalia had never really got on. Their relationship did not improve in spite of the more than satisfactory sales of her latest records, in particular Silent Night (awarded a prize by Jazz Hot magazine in France in 1953) and In The Upper Room (1). Hammond, now in charge of the small Vanguard label, suggested to Mitch Miller, his opposite number at Columbia, that he offer Mahalia Jackson a five-year renewable contract including four annual recording sessions. But all this needed thinking about and John Hammond was still having second thoughts when he phoned Mahalia: “My good A&R friends at Columbia really know next to nothing about gospel (…) You could lose the best audience you’ve ever had: your own black audience, church-grounded. While you’re reaching out to find that elusive white crowd Columbia expects will come to swoon over gospel as it came to revere jazz and blues, it might just not happen. So my advice to you, my dear – think about this before you leap.”(2)But Mahalia’s ambition to become a best seller was growing. She was now at her peak and was determined to follow her instinct. She was offered a contract but, still uncertain, she did not sign up immediately. Still with Apollo, she recorded (probably in May) with her loyal pianist Mildred Falls, a rhythm section and a male voice quartet (3) two beautiful gospel songs before giving a concert in the Chicago Stadium in front of a black audience in which, however, one or two white faces stood out e.g. her friend journalist Studs Terkel (4) and singer Pete Seeger.

She then went on the road with a Gospel Train for a long tour in the South and Southwest. Her partners were the ever faithful James Lee (4), female vocalist “Blind” Princess Stewart (who would later become more widely known in 1962 in Langston Hughes’ “Black Nativity”), Singing Sammy and Reverend Jodie Strawther (6). It was during this tour, somewhere between Georgia and Florida, that Mahalia learnt on July 1st of the death of her father Johnny Jackson at the age of 76. But the show must go on and the road show continued through Texas (Little Rock, Dallas…) before ending in California. Mahalia had taken he famous contract along with her and, after having read all the small print very carefully, finally signed it in Oakland. During this period she had the opportunity to sing duos with Brother Joe May, the greatest gospel soloist of the time who was considered the masculine equivalent of Mahalia Jackson. In August 1953, Mahalia recorded four sides with the excellent Melody Echoes quartet. Two gospel compositions by Tommy Dorsey were backed by two more classic titles, I Believe and Consider Me, published under the Lloyds label and aimed at the pop market i.e. a white audience. In September Mahalia took part in an NBC radio broadcast in Miami, before going on to New York. It was on this occasion, on 4 October 1953, that, as her biographer Laurraine Goreau recounts, she stayed for the very first time in an “whites only” hotel in New York which, in view of her reputation, seems incredible to those of us on this side of the Atlantic! Then, following a now firmly established schedule, she gave her fourth annual recital at the Carnegie Hall accompanied by Mildred Falls on piano and Louise Overall Weaver on organ. Among other singers and groups appearing at this “Gospel Jubilee”, organised as usual by her impresario Joe Bostic (4), were the Dixie Hummingbirds and the Davis Sisters.

A few days later Mahalia turned in one of her final sessions for Apollo that was divided into two halves. Seven titles were recorded, the first four slow, majestic hymn tunes which, although interpreted very simply by the singer, are not among her most unforgettable hits, especially No Matter How You Pray/My Cathedral, also published by the Lloyds label. The presence of a large mixed choir singing in a strictly arranged style underlined the classical aspect of the interpretations. The three remaining titles, on the other hand, are in a completely different vein, particularly the haunting I Wonder If I Will Ever Rest backed by the beat of drums.Around this time Ebony, the most important black magazine in the country, devoted its first full-length article to her. Then finally came the meeting with Mitch Miller who countersigned the famous contract. However, this did not mean that Columbia’s doors would suddenly open wide for Mahalia, the directors still somewhat hesitant in view of the fact that she had stipulated that she would only sing a religious repertoire. The Chicago Daily News, reporting the event, wrote “Her popularity here is confined largely by her fellow Negroes…Most white Chicagoans have never heard her”. And Mahalia Jackson had been living and playing in Chicago since 1927!A new countrywide tour took place in spring 1954 when Mahalia was on the road again with Mildred Falls, James Lee and Rev. Strawther. These long, exhausting tours, so necessary for coloured singers to meet their public, reveal the cruel difference between concerts given in the North in front of a respectful white audience and the hostile reception that Southern Whites reserved for visiting coloured performers. Mahalia said: “The minute I left the concert hall (where she had sung for a black audience) I felt as if I was returning to the jungle”.

She was travelling with Mildred and her cousin John Stevens, a young actor from Chicago who drove her sky blue Cadillac. “A nightmare! There was nowhere for us to eat or sleep along the roads. Restaurants didn’t want to serve us. When we got out of the car to buy something to eat, people gave us strange looks. Service stations refused to serve us.”(2) This is how Jules Schwerin remembers this period before the Civil Rights movement had really got going. It was normal for musicians to be paid in cash at the end of their show, to get back in their car and then to drive throughout the night to their next gig. They often had to sleep in the car if they couldn’t find a black hotel or a rooming house run by a Negro. This was the situation during Mahalia’s early years of trying to break into the white music market. When the tour ended, Mahalia began to look around for a new organist as both her regular accompanists, Louis Overall and Blind Francis, did not find it easy to travel. She heard about a young organist, Ralph Jones, working with Prophet Powers (7) in a small storefront church on 51st Street.Mahalia still owed Apollo one session which took place in June 1954 when she turned in some magnificent interpretations of traditional Negro spirituals. Perhaps to bring them in line with the mambo vogue that was sweeping the States at the time, other so-called “exotic” instruments were added e.g. the sax on one track. The session included two very different vocal versions of the famous Nobody Knows and two versions of I’m On My Way one with a vocal quartet that, according to Paul Jones, possibly came from a previous session. Ralph Jones was hired for the summer tour and he and Mildred Falls worked perfectly together, going on to form the backbone of the Falls-Jones Ensemble that would accompany Mahalia, both on Columbia records and on stage, for many years.Meanwhile Mitch Miller had not been idle.

He contacted a producer friend from Chicago, Lou Cowan, and asked him to organise a regular radio programme starring Mahalia Jackson. When Mahalia heard that CBS were looking for a staff writer she immediately thought of Studs Terkel who had given her her first radio chance in 1947. But, in 1954, CBS wanted nothing to do with Terkel whose name was on the Red Channel (a branch of the reactionary press) black list of Americans who were “disloyal” or “communist”. A list, that during the MacCarthy era, led to the boycott and even exile of numerous actors, musicians etc. …including Charlie Chaplin! Thus, Studs Terkel was considered a “bad American” making daily comments, considered “dangerous for the Nation”, on a Chicago radio station. But Mahalia insisted and CBS finally agreed on condition that the journalist’s name was not mentioned on air. Terkel accepted and the first “Mahalia Jackson Show” was broadcast on Sunday 26 September 1954 from 21h35 to 22h. Mahalia sang I Believe, Didn’t It Rain (8), the standard You’ll Never Walk Alone and The Lord’s Prayer accompanied by Mildred, Ralph and a white quartet led by Jack Halloran. Up to the 6 February 1955 twenty weekly programmes were broadcast, attracting a wide audience and enthusiastic reviews (2). The singer also appeared on television.Two weeks before her radio premier, on 11 September, an agreement putting an end to their association was signed by Bess Berman’s and Mahalia’s lawyers, in a very stormy atmosphere,. Also in September she appeared in New York with her old partners Robert Anderson and Blind James Francis. She gave her fifth recital at Carnegie Hall and, during a reception, she met Duke Ellington who, after dinner, sat down at the piano and accompanied Mahalia on The Lord’s Prayer. Some years later, in 1958, these two outstanding figures of Afro-American music got together to record several themes from Ellington’s “Black, Brown And Beige” suite, the only time that Mahalia accepted to record non-religious music.

But, it must be said that these themes, expressing racial dignity are not so far removed in feeling from the most beautiful Negro spirituals. Because Mahalia understood this she could not refuse to take part in a work written by a musician she so much admired.Thus, our fourth volume of the Complete Mahalia Jackson ends with her Apollo recordings. On 22 November 1954, she entered for the first time the CBS/Columbia studios accompanied by Mildred Falls and Ralph Jones. No fewer than fourteen titles were recorded under the artistic direction of George Avakian. A new story was beginning for “The World’s Greatest Gospel Singer” as she was now billed by the company… a story that would end only shortly before her death on 27 January 1972.Suffice it to say that, in the early 50s and on her Apollo recordings, Mahalia Jackson was at her peak. Her powerful, rich and moving voice, her wide range, innate sense of timing and rhythm, plus her gift for improvisation, convey such deep feeling that the listener cannot help but be deeply moved.

Adapted from the French text of Jean Buzelin by Joyce Waterhouse

© FRÉMEAUX & ASSOCIÉS - GROUPE FRÉMEAUX COLOMBINI SA, 2005

Notes:

(1) See Complete Mahalia Jackson Vol. 3 (FA 1313). Singer Claude Wright has given us the following information concerning In The Upper Room : a first version of this theme was recorded by Mahalia Jackson accompanied by the Selah singers, with whom Wright was singing at the time. However, it was never issued – it has probably been lost – and it is the second version with the Southern Harmonaires, the other quartet founded by Thermon Ruth, which became such a great hit. The Selah Singers sang with Mahalia during the radio broadcasts organised by Joe Bostic in New York.

(2) Quoted by Jules Schwerin in God To Tell It (see Works consulted)

(3) This was probably Melody Echoes who recorded six titles for Apollodoubtless the same day (matrix nos. 2525 to 2531).

(4) See Complete Mahalia Jackson Vol. 2 (FA 1312).

(5) See Complete Mahalia Jackson Vol. 1 (FA 1311).

(6) This singer cut several records in Los Angeles in the late 40s under the name Brother Jodie Strawther.

(7) Prophet Powers (or Powell) led a large choir that also recorded for Apollo.

(8) The first version of this theme sung by Mahalia Jackson and later issued by Apollo, was recorded on an unknown date, perhaps around 1953/1954 or even before, as Mahalia had already had her repertory for some years. We have reissued here the original version, not the one artificially lengthened (by inserting repeated couplets) which features on most CD reissues.

Works consulted:

Laurraine Gorreau: Mahalia (Lion Pub; UK 1976 – 2nd edition)

Jules Schwerin : God to Tell It: Mahalia Jackson (O.U.P. 1992)

Robert Sacré: Les Negro Spirituals et les Gospel Songs (Que-Sais-Je?, PUF, Paris 1993)

Denis-Constant Martin: Le Gospel afro-américain (Cité de la Musique/Actes Sud, Paris 1998

Jean Buzelin: Negro Spirituals & Gospel Songs (Ed. du Layeur, Paris 1998)

Noël Balen: Histoire du Negro Spiritual et du Gospel (Fayard, Paris 2001).

With special thanks to Etienne Peltier and Robert Sacré for the loan of records from their collections, and to Daniel Gugolz, Bob Laughton, Per Notini and Clyde Wright for their collaboration.

Photos X (D.R.) and collections: Jean Buzelin, François-Xavier Moulé, Melrose Square Pub. In Mahalia Jackson.

Discographie

01. I’M GOING TO THE RIVER (B. Reles - B. Smith) C2523

02. ONE DAY (K. Morris) C2524

03. I BELIEVE (E. Drake - J. Shirl - I. Graham - A. Stillman) C2532

04. BEAUTIFUL TOMORROW (T.A. Dorsey) C2533

05. BEAUTIFUL TOMORROW (T.A. Dorsey) C2533-alternate take

06. CONSIDER ME (E. Drake - J. Shirl - I. Graham - A. Stillman) C2534

07. WHAT THEN? (T.A. Dorsey) C2535

08. HANDS OF GOD (Lafayette) C2536

09. IT’S REAL (Cox - arr. M. Jackson) C2537

10. NO MATTER HOW YOU PRAY (Machan - Allen) C2538

11. MY CATHEDRAL (Eddy - Wayne) C2539

12. WALKING TO JERUSALEM (UP IN JERUSALEM) (Trad. - arr. M. Jackson) C2540

13. I WONDER IF I WILL EVER REST (A. Hunter) C2541

14. COME TO JESUS (L. Pauling) C2542

15. DIDN’T IT RAIN (Trad. - arr. R. Martin) AP3000

16. (I’M) ON MY WAY (TO CANAAN) (Trad. - arr. M. Jackson) C2561-alternate take

17. I’M ON MY WAY TO CANAAN (Trad. - arr. M. Jackson) C2561

18. MY STORY (M. Jackson) C2562

19. RUN ALL THE WAY (WILLING TO RUN) (Trad. - arr. M. Jackson - B. Smith) C2563

20. NOBODY KNOWS THE TROUBLE I’VE SEEN (Trad. - arr. B. Smith) C2564

21. NOBODY KNOWS (THE TROUBLE I’VE SEEN) (Trad. - arr. B. Smith) C2564-alternate take

Mahalia Jackson (vocal) with :

(1-2) Mildred Falls (piano), unknown (organ)(guitar)(bass)(drums), prob. The Melody Echoes (male vocal group). New York City, prob. 05/05/1953.

(3-7) Mildred Falls (piano), unknown (organ)(guitar, out on 7)(bass, out on 7)(drums, out on 3), The Melody Echoes (male vocal group). New York City, prob. 08/08/1953.

(8-11) Mildred Falls (piano), unknown (organ), The Belleville Choir (vocal). New York, prob. 09/10/1953.

(12-14) Mildred Falls (piano), unknown (organ)(guitar on 13)(drums), The Melody Echoes (vocal). New York City, prob. 12/10/1953.

(15) Mildred Falls (piano), unknown (organ). Unknown session, ca. 1953/1954.

(16-21) Mildred Falls (piano, out on 18), unknown (organ)(tenor saxophone on 19)(bass on 19, 20, 21)(drums on 19, 20, 21)(bongos, maracas on 16, 17, 18), unknown, poss. The Melody Echoes (male vocal group on 16). New York City, 10/06/1954.

CD TITRE, ARTISTE © Frémeaux & Associés (frémeaux, frémaux, frémau, frémaud, frémault, frémo, frémont, fermeaux, fremeaux, fremaux, fremau, fremaud, fremault, fremo, fremont, CD audio, 78 tours, disques anciens, CD à acheter, écouter des vieux enregistrements, albums, rééditions, anthologies ou intégrales sont disponibles sous forme de CD et par téléchargement.)