- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

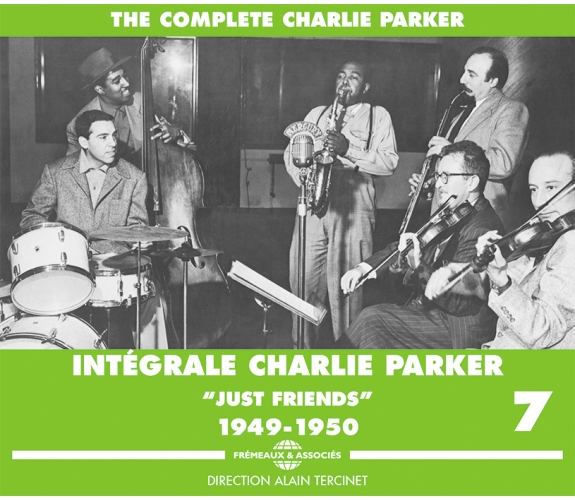

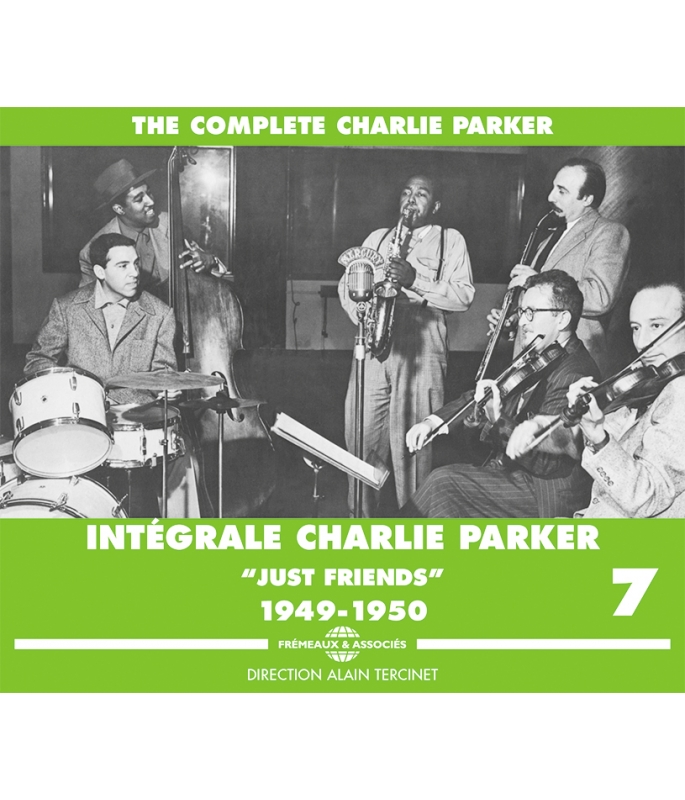

JUST FRIENDS - 1949-1950

CHARLIE PARKER

Ref.: FA1337

Artistic Direction : ALAIN TERCINET

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Total duration of the pack : 3 hours 48 minutes

Nbre. CD : 3

JUST FRIENDS - 1949-1950

JUST FRIENDS - 1949-1950

« Charlie Parker did all the things I would like to do and more – he really had a genius, see. He could do things and he could do them melodiously so that anybody, the man in the street, could hear – that’s what I haven’t reached, that’s what I’d like to reach. » John COLTRANE

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1The OpenerCharlie Parker & Jazz At The Philharmonic00:12:491949

-

2Lester LeapsCharlie Parker & Jazz At The Philharmonic00:12:321949

-

3Embraceable YouCharlie Parker & Jazz At The Philharmonic00:10:441949

-

4Just FriendsCharlie Parker & Jazz At The Philharmonic00:11:001949

-

5The CloserCharlie Parker with Strings00:03:331949

-

6Everything Happens To MeCharlie Parker with Strings00:03:181949

-

7April In ParisCharlie Parker with Strings00:03:091949

-

8SummertimeCharlie Parker with Strings00:02:481949

-

9I Didn't Know What Time It WasCharlie Parker with Strings00:03:151949

-

10If I Should Lose YouCharlie Parker with Strings00:02:521949

-

11Annonce/OrnithologyCharlie Parker Quintet00:05:351949

-

12CherrylCharlie Parker Quintet00:05:001949

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1KokoCharlie Parker Quintet00:05:031949

-

2Bird Of ParadiseCharlie Parker Quintet00:06:081949

-

3Now's The TimeCharlie Parker Quintet00:05:141949

-

452nd Street ThemeCharlie Parker, Fats Navarro & The Bud Powell Trio00:01:351950

-

5WahooCharlie Parker, Fats Navarro & The Bud Powell Trio00:06:351950

-

6Round MidnightCharlie Parker, Fats Navarro & The Bud Powell Trio00:05:141950

-

7This Time The Dreams On MeCharlie Parker, Fats Navarro & The Bud Powell Trio00:06:231950

-

8Dizzy AtmosphereCharlie Parker, Fats Navarro & The Bud Powell Trio00:07:051950

-

9A Night In TunisiaCharlie Parker, Fats Navarro & The Bud Powell Trio00:05:381950

-

10Move/52nd Street ThemeCharlie Parker, Fats Navarro & The Bud Powell Trio00:06:511950

-

11The Street BeatCharlie Parker, Fats Navarro & The Bud Powell Trio00:09:211950

-

12Out Of NowhereCharlie Parker, Fats Navarro & The Bud Powell Trio00:06:131950

-

13Little Wille Leaps/52nd Street ThemeCharlie Parker, Fats Navarro & The Bud Powell Trio00:05:541950

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1OrnithologyCharlie Parker, Fats Navarro & The Bud Powell Trio00:07:571950

-

2I'll Remember April/52nd Street ThemeCharlie Parker, Fats Navarro & The Bud Powell Trio00:09:391950

-

3Embraceable YouCharlie Parker, Fats Navarro & The Bud Powell TrioGeorge & Ira Gerschwin00:06:071950

-

4Cool BluesCharlie Parker, Fats Navarro & The Bud Powell Trio00:06:531950

-

552nd Street ThemeCharlie Parker, Fats Navarro & The Bud Powell Trio00:02:121950

-

6I Don T Know What Time It WasCharlie Parker Quintet00:02:381950

-

7OrnithologyCharlie Parker Quintet00:03:301950

-

8I Cover The WaterfrontCharlie Parker Quintet00:02:201950

-

9VisaCharlie Parker Quintet00:03:001950

-

10Embraceable YouCharlie Parker Quintet00:01:471950

-

11Scrapple From The AppleCharlie Parker Quintet00:04:401950

-

12Star EyesCharlie Parker Quintet00:02:541950

-

1352nd Street ThemeCharlie Parker Quintet00:00:141950

-

14ConfirmationCharlie Parker Quintet00:03:161950

-

15Out Of NowhereCharlie Parker Quintet00:02:201950

-

16Hot HouseCharlie Parker Quintet00:03:481950

-

17What's NewCharlie Parker Quintet00:02:461950

-

18Now's The TimeCharlie Parker Quintet00:04:181950

-

19Smoke Gets In Your EyesCharlie Parker Quintet00:03:341950

-

2052nd Street Theme IICharlie Parker Quintet00:01:131950

Intégrale Charlie parker vol. 7 FA1337

THE COMPLETE Charlie Parker 7

INTÉGRALE Charlie Parker 7

“JUST FRIENDS”

1949-1950

DIRECTION ALAIN TERCINET

Proposer une véritable «?intégrale?» des enregistrements laissés par Charlie Parker est actuellement impossible et le restera longtemps. Peu de musiciens ont suscité de leur vivant autant de passion. Plus d’un demi-siècle après sa disparition, des inédits sont publiés et d’autres – dûment répertoriés – le seront encore. Bon nombre d’entre eux ne contiennent que les solos de Bird car ils furent enregistrés à des fins privées par des musiciens désireux de disséquer son style. Sur le seul plan du son, ils se situent en majorité à la limite de l’audible voire du supportable. Faut-il rappeler, qu’à l’époque, leurs auteurs employaient des enregistreurs portables sur disque, des magnétophones à fil, à bande (acétate ou papier) et autres machines devenues obsolètes, engendrant des matériaux sonores fragiles??

Aucun solo joué par Charlie Parker n’est certes négligeable, toutefois en réunissant chronologiquement la quasi-intégralité de ce qu’il grava en studio et de ce qui fut diffusé à l’époque sur les ondes, il est possible d’offrir un panorama exhaustif de l’évolution stylistique de l’un des plus grands génies du jazz?; cela dans des conditions d’écoute acceptables.

Toutefois lorsque la nécessité s’en fait sentir stylistiquement parlant, la présence ponctuelle d’enregistrements privés peut s’avérer indispensable. Au mépris de la qualité sonore.

L’intégrale CHARLIE PARKER

STUDIO & RADIO VOL. 7

“JUST FRIENDS” 1949 - 1950

« ?No Bop Roots In Jazz : Parker?». Quelle mouche a donc piqué Bird, lui qui, jusque-là, entretenait soigneusement un certain flou artistique dans ses propos et, lors d’une écoute aveugle organisée par Metronome, avait manifesté un éclectisme de bon aloi ? Interrogé à plusieurs reprises par Michael Levin et John S. Wilson, Parker exposait, sans précautions oratoires, sa conception de la musique qu’il entendait défendre. Avec un sens de la provocation justifiant le surtitre qui barrait, le 9 septembre 1949, la première page de Down Beat. Reniant - à tort ou à raison - toute référence marquée envers la tradition, sans pour autant s’inféoder à la musique contemporaine, il entendait bien ne pas s’interdire de flirter avec un procédé comme l’atonalité - ce qu’il fera mais pratiquement à la sauvette. Parker en profitait pour égratigner quelque peu le penchant de Gillespie pour l’exhibitionisme vestimentaire. Un sujet sur lequel Dizzy ne répliqua pas lorsque, un mois plus tard dans le même magazine, il ripostait au brûlot parkerien au moyen d’un article intitulé «?Bird Wrong ; Bop Must Get a Beat : Dizzy?».

Rien ne laissait prévoir une telle foucade de la part de Bird revenu aux Etats-Unis depuis la fin du mois de mai. La réception qu’il avait connue à Paris l’avait-elle incité à formuler ce credo agressif qui le dissociait de la scène traditionnelle du jazz, alors même que l’on annonçait l’ouverture sur Broadway d’un club baptisé «?Birdland?» en son honneur ? Peut-être.

Dans son élan, Bird avait fourni aux journalistes de Down Beat un inter à tout le moins discutable, «?Lester Didn’t Influence Me?». La preuve du contraire sera apportée au cours d’un concert donné à Carnegie Hall le 17 septembre par la troupe du Jazz At The Philharmonic. S’y trouvaient réunis, entre autres, Roy Eldridge, Tommy Turk, Flip Phillips, Ray Brown, Hank Jones, Lester Young et… Bird. The Opener et le plus intéressant morceau du concert, Embraceable You, offrent l’illustration parfaite d’une filiation Prez / Bird. Sur ce dernier titre, l’édition originale en LP comprenait un montage faisant se succéder les interventions de Lester et de Parker alors que, sur scène, un solo de Tommy Turk venait s’immiscer. Une décision éditoriale, ici respectée, parfaitement logique lorsque l’on écoute la réédition en CD, conforme, elle, à la chronologie des chorus.

«?Quand j’ai enregistré avec des cordes, certains de mes amis ont dit «?Tiens, Bird devient commercial !?» Ce n’était pas du tout ça. Je cherchais de nouvelles façons de dire des choses musicalement. De nouvelles combinaisons sonores (1).?» Doris Sydnor, épouse légitime de Parker depuis 1948, précisera : «?Norman Granz n’était pas à l’origine de l’idée de faire travailler Charlie avec des cordes. C’était son rêve – et peut-être que ça lui a cassé les pieds plus tard. mais Norman ne l’a fait que pour faire plaisir à Charlie (2).?» Non sans réticences : «?Charlie Parker voulait des cordes. D’un point de vue économique, j’étais horrifié ; c’était affreusement cher ! J’ai dit à Charlie «?Pourquoi ne fais-tu pas ça avec un trio ??» Charlie refusa, il voulait des cordes. Il savait exactement ce qu’il voulait (3).?» Un tournant dans la carrière de Bird sur lequel nous reviendrons.

Le 30 novembre, Parker se serait retrouvé dans un studio, face à trois violons, un alto, un violoncelle et une harpe, assistés de Ray Brown, Buddy Rich et du pianiste Stan Freeman, un musicien de studio. Selon le principal intéressé, Mitch Miller, l’ajout d’un hautbois aurait été le fruit d’une décision de dernière minute. Conseiller musical des répertoires chez Mercury, sollicité pour l’occasion par Norman Granz, il avait engagé comme arrangeur son vieux complice, Jimmy Carroll?; un professionnel à l’écriture dépourvue de la moindre audace.

Allergique à tout ce qui pouvait ressembler à une répétition, Granz décida que la mise au point se ferait sur le tas. La légende dorée du jazz voudrait que, miraculeusement, l’album de 78 t «?Charlie Parker with Strings?» fut mis en boîte en deux temps trois mouvements. Divers témoignages, dont celui de Stan Freeman, laissent entendre qu’en fait les choses ne se passèrent pas si simplement : un certain nombre de rencontres non répertoriées auraient eu lieu avant que les six morceaux prévus réussissent à être gravés. Ainsi, après avoir interprété le seul Just Friends, Parker disparut dans la nature. Granz expliquera qu’il était tellement ému par ce qu’il venait d’entendre interprété par l’ensemble à cordes qu’il ne s’était pas senti capable de jouer. La chose est plausible, un tel désarroi n’étant pas passé inaperçu aux yeux de Franz Brieff, futur chef du Columbia Symphony Orchestra, qui participait à la séance en tant qu’altiste?: «?Ce qui m’a vraiment touché, c’est qu’il était fier de nous avoir, car apparemment, on lui avait parlé de ce que nous faisions dans le monde de la musique. Il avait le sentiment que nous étions de plus grands musiciens que lui, ce qui était parfaitement faux […] Il nous a tous ébahis par sa superlative façon d’improviser. Bien sûr, nous avions des arrangements, mais il jouait avec sans cesse : il nous est arrivé de recommencer plusieurs fois et ses improvisations étaient toujours différentes, jusqu’à ce qu’il aime ce qu’il entende (4).?» Franz Brieff terminait en affirmant que Bird possédait en lui cette vertu indéfinissable, inouïe, qui fait de quelqu’un un musicien d’exception.

Dans ce nouvel environnement, Bird s’exprimait d’une façon nouvelle pour lui. Respectant les standards sélectionnés, il endossait le rôle d’un enlumineur plutôt que celui d’improvisateur.

Un positionnement relativement banal dans le jazz que sublimait son exceptionnel génie de mélodiste, ajouté à un sens rare des nuances dans l’énoncé. Bird respectait son contrat : «?Je cherchais de nouvelles façons de dire des choses musicalement.?» Couplé avec Everything Happens to Me sur un 78 t qui sera l’une des meilleures ventes de Bird, Just Friends compte parmi les plus grandes interprétations de Charlie Parker.

Si, dans ce contexte, les musiciens entourant Parker ne tenaient qu’un rôle d’accompagnateurs au sens premier du terme, il en était autrement dans le quintette renouvelé que Bird dirigeait en parallèle. Lorsque Max Roach avait décidé de reprendre sa liberté, il avait alerté quelqu’un qui commençait à faire parler de lui dans le petit monde de la percussion, Roy Haynes. Ex-accompagnateur régulier de Lester Young et, sporadiquement, de Stan Getz, il se produisait au sein de la formation que Bud Powell dirigeait à l’Orchid Club. Très heureux de cette situation, il déclina, dans un premier temps, l’offre de Parker. Pour changer d’avis au mois d’octobre : il alla retrouver Bird au Three Deuces. Sonny Rollins : «?Roy était différent. Il était capable d’accompagner Parker de la manière la plus fantastique. Il avait sa propre sonorité et ses propres manières.?» Chan confiera à Roy Haynes, le jour des obsèques de Bird, que ce dernier le considérait comme le meilleur batteur qu’il ait jamais eu.

Le quintette de Parker comprenait un autre nouveau, le jeune trompettiste Robert Chudnick alias Red Rodney. Un choix qui en avait étonné plus d’un, y compris l’intéressé lui-même : «?J’ai protesté un moment. J’ai dit «?Je ne suis vraiment pas prêt pour travailler avec toi?». Et j’ai même suggéré Fats Navarro qui était dans le circuit et qui était certainement plus prêt. Kenny Dorham également dont je pensais qu’il était meilleur. Et il m’a répondu «?Peut-être, mais je sais reconnaître un bon trompettiste quand je l’entends et c’est toi que je veux» (5).?» Red Rodney qui, malgré son jeune âge, avait appartenu à un nombre conséquent de grandes formations – Gene Krupa, Buddy Rich, Claude Thorhill, Woody Herman, entre autres – s’était converti très tôt au bop. Certes, il n’égalait pas Dizzy, non plus que Miles ou Kenny Dorham, mais Bird avait pressenti dans son jeu une complémentarité avec le sien, évidente au fil des interprétations. Presque toutes prises sur le vif car Red Rodney ne franchira qu’à de très rares reprises les portes d’un studio en compagnie de Parker…

Le 15 décembre, à la tête de son quintette, Charlie Parker tint bien évidemment la vedette, lors de l’inauguration du Birdland - ex-The Clique – qui se vantera d’être «?The Jazz Corner of the World?». Participèrent à la fête Max Kaminsky, Lester Young, Stan Getz, Lennie Tristano, Lee Konitz, Hot Lips Page et Harry Belafonte encore très loin du calypso.

Dix jours plus tard, Bird, Red Rodney, Al Haig, Tommy Potter et Roy Haynes entraient sur la scène de Carnegie Hall à l’occasion d’un concert-fleuve présenté par Leonard Feather et Symphony Sid, «?The Stars of Modern Jazz?». À leur suite défileront le trio de Bud Powell, Miles Davis, Stan Getz, Kai Winding, Sarah Vaughan et Lennie Tristano à la tête de son propre quintette. Charlie Parker et ses partenaires offrirent une prestation exemplaire, composée de «?classiques?» éprouvés comme Ornithology, Cheryl où Parker, salué par les ovations du public, cite le solo d’Armstrong sur West End Blues, Ko Ko, Bird of Paradise – un chef d’œuvre - et Now’s the Time. Pour la petite histoire, au milieu des années 50, cette partie du concert fut éditée sur un LP 25 cm hors commerce par le Hot Club de Lyon. Sans doute l’une des toutes premières initiatives du genre.

Charlie Parker, Fats Navarro, Bud Powell, Curley Russell, Art Blakey… une réunion vraiment digne du qualificatif de «?All Stars?». Les mystères et les incertitudes ne manquent pas dans la discographie de Charlie Parker mais, cette fois, on se trouve devant un cas d’école. L’endroit où se tint ce «?Summit Meeting?» fit longtemps l’objet d’un débat. La «?Discographie commentée des enregistrements publics de Charlie Parker?» de Michel Delorme (6) désignait le Café Society, localisation reprise sur un LP japonais. Depuis, un certain consensus s’est fait sur le Birdland en tenant compte du fait que Bud Powell y était alors un habitué. S’agit-il d’une seule prestation ? Divers témoignages - celui de Little Jimmy Scott entre autres - donneraient à penser que ce fut le cas, hypothèse confortée par une certaine uniformité dans la prise de son. Pourtant trois dates différentes figurent sur les étiquettes de «?Boris Rose Records?» - collection Norman R. Saks - reproduisant une partie des interprétations, 1, 8 mai et 1 juin alors que plupart des discographies s’accordent sur le 15-16 mai d’après l’inscription écrite sur une boîte. Quand à espérer résoudre le problème en se référant à la programmation du Birdland, peine perdue… À la rubrique concernée, Down Beat imprimait «?Changement continuel de musiciens, toutefois la programmation concerne toujours le jazz moderne.?» Sans commentaire…

Certains historiens s’interrogent. Divers témoins, dont Ira Gitler et Dan Morgenstern, ont décrit l’état pitoyable de Fats Navarro dans les mois précédant sa disparition survenue le 7 juillet 1950. Un décès dû à la tuberculose jointe à une sévère addiction à l’héroïne. Ce qu’il interprète au cours de cette soirée - son chorus sur The Streat Beat est le plus long qui soit conservé de lui - ne semble pas le fait d’un musicien diminué. Navarro joue ici d’une façon plus brillante qu’en septembre 1949, au cours de sa dernière séance d’enregistrement sous la houlette de Don Lanphere. À l’écoute de Fats sur Dizzy Atmosphere, de la précision dont il fait preuve durant les unissons de Little Willie Leaps pris sur tempo ultra-rapide, sans parler de sa version de A Night in Tunisia, il n’est pas déraisonnable d’envisager comme datation le tout début de 1950. Ou même plus tôt. À moins d’une rémission quasi miraculeuse.

Au mieux de son art, servi par un Bud Powell en forme superlative, débarrassé un temps de ses préventions - l’entente entre lui et Parker n’était pas toujours au beau fixe -, Bird atteint à des sommets au long de ‘Round Midnight et This Time the Dream’s on Me. À l’occasion de Out of Nowhere, et dans une moindre mesure sur Little Willie Leaps, il se livre à une entreprise d’abstractisation de thèmes figurant depuis belle lurette à son répertoire. Une démarche qui, comme le faisait remarquer Dan Morgenstern, s’apparente à celle de Lee Konitz ou de Warne Marsh. Aussi bien lors de l’ouverture du Birdland que sur la scène de Carnegie Hall, Bird les avait côtoyés, tous deux étant membres du quintette de Lennie Tristano…

Sur Ornithology, peut-être l’œuvre la plus accomplie issue de cette rencontre, porté par une rythmique en état de grâce, encouragé par le «?Goooo, Baaaby?» lancé d’une voix de fausset par Pee Wee Marquette, Bird prouve une nouvelle fois qu’il ne jouait pas tout-à-fait dans la même cour que ses partenaires ; aussi talentueux soient-ils. D’excellente humeur, il cite une fois de plus la Habanera de Carmen avant de provoquer, sur I’ll Remember April, une série d’échanges de haut vol avec un Art Blakey frénétique, dispensant ses «?bombes?» avec à-propos et générosité. Dans son rôle difficile de point d’ancrage, Curley Russell se montre irréprochable. Rien ne vient entacher une séance à tout point de vue exceptionnelle. Jusque là…

Si Embraceable You inspire à Bird un solo plein de sensibilité, il fit l’erreur d’y inviter Little Jimmy Scott dont le vocal ne peut trouver grâce qu’aux oreilles de ses fans inconditionnels. Disons à sa décharge que la rythmique ne lui facilita pas la tâche, Bud Powell ayant été manifestement irrité par son intrusion. Il cédera d’ailleurs sa place à Walter Davis Jr. qui, sur Cool Blues, reprend tant bien que mal l’accompagnement imaginé par Erroll Garner lors de la version princeps gravée pour Dial. Pour l’occasion, il semble que Tommy Potter et Roy Haynes aient remplacé Russell et Blakey (7).

À l’exemple de Dean Benedetti, pour leur satisfaction personnelle et leur gouverne, certains musiciens fascinés par Parker s’employaient à péréniser coûte que coûte ses chorus. Au moyen d’enregistreurs divers et variés, dans des conditions matérielles insensées. Ces captations se déroulaient bien sûr clandestinement, au grand dam des organisateurs de soirées et patrons de cabarets. Sur ce sujet, les anecdotes abondent, allant du percement de trous dans des cloisons à l’investissement de toilettes prétendûment «?hors service?». Ce samedi soir là, au Saint Nicholas Arena, le saxophoniste Don Lanphere était à la tâche.

Il n’allait pas bénéficier des meilleures conditions accoustiques possibles. Métamorphosé pour l’occasion en dancing, le St Nicholas Arena abritait d’ordinaire… des combats de boxe. Fut-ce le fait de jouer pour un public dépourvu de préjugés ? Toujours est-il que Parker fit preuve d’une liberté rarement égalée jusque-là. Malgré leurs imperfections sonores et une fragmentation regrettable, les interprétations comportent des fulgurances qui, plus d’un demi-siècle après, surprennent toujours par leur audace. Quand aux échanges Parker / Rodney sur Scrapple from the Apple, Ornithology-1, Confirmation ou Hot House, ils confirment le bien fondé du choix de Bird.

D’écoutes collectives en copies privées, les enregistrements du St Nicholas Arena finirent par acquérir une réputation quasi légendaire. À tel point que Jazz Workshop, une sous-marque du label Debut créé par Charles Mingus et Max Roach, les publia à la fin des années 1950. Contrairement à son volume jumeau, «?Bird on 52nd Street?», plus aléatoire, il est impossible pour tout amateur de faire l’impasse sur «?Bird at St Nick’s?».

Alain Tercinet

© 2014 Frémeaux & Associés

(1) Livret de «?The Complete Charlie Parker on Verve?».

(2) Robert Reisner, «?La légende de Charlie Parker?», trad. François Billard et Catherine Weinberger-Thomas, Pierre Belfond, 1989.

(3) Propos tenus par Norman Granz en 1984, rapportés par Bill Kirchner – Internet.

(4) comme (1).

(5) Ben Sidran, «?Talking Jazz?», trad. Christian Séguret, Night and Day Library – Bonsaï, 2005.

(6) Jazz Hot n° 207, mars 1965.

(7) Est-ce toujours Fats Navarro à la trompette ? Sans aucun doute selon Leif Bo Petersen et Theo Rehak («?The Music and Life of Theodore «?Fats?» Navarro?», Studies in Jazz n°59, The Scarecrow Press, Lanham, Maryland, 2005) alors que Laurence O. Koch penche pour Red Rodney («?Yardbird Suite?», Northeastern University Press, 1999). Ce qui semble douteux, Rodney venant de subir une appendisectomie.

NOTES DISCOGRAPHIQUES

Jazz at The Philharmonic

Trois morceaux récemment retrouvés - ils ne peuvent donc figurer ici - mettent en vedette Ella Fitzgerald. Ils viennent s’ajouter aux rééditions en CD du concert. Probablement absent au cours de Flying Home dévolu à Flip Phillips, Parker intervient sur How High the Moon et Perdido.

Conservé sur une transcription quasi inaudible en compagnie de fragments de Lover Come Back to Me, Bean and the Boys et The Man I Love - ces deux derniers sans Parker -, un Stuffy incomplet auquel participe Coleman Hawkins, a donné lieu à plusieurs datations. La plus courante situe l’événement au mois de juin alors que le calendrier des prestations du J.A.T.P. donné dans le livret de coffret «?The Complete Jazz At The Philharmonic on Verve 1944/1949?», ne fait mention d’aucun concert à cette période. Certains pensent qu’il pourrait venir du concert donné le 17 septembre qui précédait celui de minuit.

Fats Navarro, Charlie Parker & the Bud Powell Trio

Dans leur discographie consacrée à Charlie Parker, Piet Koster et Dick M. Bakker, comme Tom Lord, Walter Bruyninckx et Jorgen Grunnet Jepsen, indiquent «?broadcast?» à l’origine de ces bandes. Pour Norman Saks, Leonard Bukowski et Robert M. Bregman, auteurs de «?The Charlie Parker Discography?», on serait en présence d’enregistrements privés, ce qu’estime également Tony Williams qui donne comme responsable Bill Hirsh agissant pour le compte de Boris Rose. Ce qui est certain est que ces interprétations figuraient dans le fond du collectionneur impénitent de «?broadcasts?» qu’était ce dernier et qu’il en reproduisit des extraits à la demande avant de les publier sur des LP aux appellations fantaisistes. Cette séance du Birdland était depuis longtemps connue des collectionneurs car elle figure dans la discographie de Charlie Parker incluse dans le volume 6 de «?Jazz Records 1942-1962?» de Jorgen Grunnet Jepsen (1963).

Wahoo : intitulé Perdido dans de nombreuses éditions, ce morceau est souvent amputé du début du solo de Bud Powell suivant celui de Fats Navarro.

A Night in Tunisia : Malgré l’absence de Parker, cette interprétation figure ici en raison du jeu de Fats Navarro.

Il existe un titre supplémentaire, Conception / Deception, sur lequel Miles Davis, J. J. Johnson, Brew Moore se joignent à la formation de Cool Blues. Il ne figure pas ici en raison de sa piètre qualité sonore et du fait que Bird n’y prend pas de solo.

A genuine “complete” set of the recordings left by Charlie Parker is impossible today and will remain so for a long time to come. Few musicians aroused so much passion during their own lifetimes and today, more than half a century after his disappearance, previously-unreleased music is published, and other titles – duly listed – will also come to light. A good many contain only solos by Bird, as they were recorded – privately – by musicians wanting to dissect his style. Regarding their sound-quality, most of them are at the limit: barely audible, sometimes almost intolerable, but in fact understandable: those who captured these sounds used portable recorders that wrote direct-to-disc, or wire-recorders, “tapes” (acetate or paper) and other machines now obsolete. Obviously they all produced sound-carriers that were fragile.

Of course, no solo ever played by Charlie Parker is to be disregarded. But a chronological compilation of almost everything he recorded – either inside a studio or on radio for broadcast purposes – does make it possible to provide an exhaustive panorama of the evolution of his style (Parker was, after all, one of the greatest geniuses in jazz), and to do so under acceptable listening-conditions. However, since we refer to style, the occasional presence here of some private recordings is indispensable, whatever the quality of the sound.

THE COMPLETE CHARLIE PARKER

STUDIO & RADIO VOLUME 7

“JUST FRIENDS” 1949-1950

“No Bop Roots In Jazz: Parker”. Whatever had got into him? Previously, Bird had been rather vague in his declarations, but in a blindfold test organized by Metronome he showed a respectable eclecticism. In several replies to Michael Levin and John S. Wilson, Parker laid out his conception of the music he intended to defend, and did so without taking any precautions over the words he used. His provocative leanings explained the above banner across the front page of Down Beat on September 9th 1949. Renouncing, rightly or wrongly, any marked reference to tradition — whilst not swearing allegiance to contemporary music in as many words — he had the firm intention of allowing himself a flirt with the atonal system. And he duly did so, although he rushed it somewhat. Parker seized the opportunity to take a shot at Gillespie and his penchant for dressing like an exhibitionist. The subject didn’t merit further examination from Dizzy when, a month later in the same magazine, Diz riposted by answering the Bird’s blistering attack in an article which proclaimed, “Bird Wrong; Bop Must Get a Beat: Dizzy.”

Bird’s outburst had come without warning on his return from Europe at the end of May. Was the reception he’d been given in Paris the reason that moved him to state this aggressive credo dissociating him from the traditional jazz scene, just when the announcement came that Birdland, christened in his honour, was opening on Broadway? Maybe it was.

In his élan, Bird gave Down Beat’s journalists an headline was open to argument, to say the least: “Lester Didn’t Influence Me.” Proof of the contrary was supplied during a Carnegie Hall concert by the JATP troupe on September 17th. Among them were Roy Eldridge, Tommy Turk, Flip Phillips, Ray Brown, Hank Jones, Lester Young and… Bird. The Opener and the concert’s most interesting number, Embraceable You, perfectly illustrate the Prez/Bird filiations. In the original LP release, the latter title was a montage with the contributions of Lester and Parker coming in succession, whereas onstage Tommy Turk had slipped his own solo between the two. Call it an editorial decision — respected here —, and a perfectly logical one when you listen to the CD reissue, which complies with the chronological order of the choruses.

“When I recorded with strings, some of my friends said, ‘Oh, Bird is getting commercial.’ That wasn’t it at all. I was looking for new ways of saying things musically. New sound combinations.” (1) Doris Sydnor, Parker’s legitimate wife since 1948, would make clear that “Norman Granz did not conceive the idea of Charlie working with strings. This was Charlie’s dream, and perhaps it bugged him later. But Norman did it only to please Charlie.”(2) Not without some reticence: “Charlie Parker wanted strings. Economically, I was horrified at strings; man, it was expensive! I said to Charlie, ‘Why don’t we do it with a trio?’ Charlie said no, he wanted strings. He knew exactly what he wanted.”(3) We’ll come to this turning-point in Bird’s career later.

On November 30th Parker is said to have been in the studio opposite three violins, a viola, a cello and a harp, and assisted by Ray Brown, Buddy Rich and Stan Freeman, a studio pianist. According to Mitch Miller, the man most concerned by the line-up, the addition of an oboe was a last-minute decision. As Mercury’s musical advisor on repertoire issues — Granz had called him in to do the session —, Mitch had hired his old crony Jimmy Carroll for the arrangements; Carroll was a professional, and his writing was the opposite of bold.

Granz had an allergy to anything remotely resembling a rehearsal, and so he decided to tie up all the loose ends while they were in the room. Legend — that golden legend of jazz again — has it that, as if by a miracle, the 78rpm album entitled “Charlie Parker with Strings” was put in the can in the blink of an eye. Various accounts, including that of Stan Freeman, lead us to believe that it didn’t happen quite so simply, and that apparently quite a number of unregistered meetings took place before the six tunes on the schedule were actually recorded. And that Parker, after he’d played Just Friends, just vanished. Granz would explain that Bird was so moved by what he’d just heard from the string section that he didn’t feel capable of playing another note. It’s plausible, since his disarray didn’t go unnoticed by Franz Brieff (the future conductor of the Columbia Symphony Orchestra) who was playing viola on the session: “The thing that touched me, he was really so proud to have us there because apparently he’d been told about us and what we had done in the music world. He felt that we were greater musicians than he was, and that wasn’t true at all. […] He somehow just astounded all of us by his great method of improvisation. And of course we had arrangements. He just played around with it all the time. Sometimes we would repeat it a few times, and he changed every time with his improvisations until he liked what he heard.”(4) Franz Brieff concluded by saying that Bird carried inside of him that indefinable, extraordinary virtue which makes a person an exceptional musician.

In this new environment, Bird expressed himself in (for him) a new way. Showing his respect for the standards chosen, he assumed the role of an illuminator rather than an improviser. Taking a relatively ordinary role in jazz, he sublimated it with his exceptional genius for melody, combined with his rare feeling for nuance when stating a theme. Bird respected his contract: “I was looking for new ways to say things musically.” Paired with Everything Happens to Me on a 78rpm record that turned out to be a best-seller for Bird, the title Just Friends counts as one of Charlie Parker’s greatest performances.

Whereas the musicians surrounding Parker confined themselves to their roles as accompanists (in the original sense of the word) in that context, it was quite another story with the new quintet which Bird was leading in parallel. When Max Roach decided to regain his freedom, he’d alerted someone who was starting to make a name for himself in percussion’s little world: Roy Haynes. Formerly a regular partner for Lester Young and, sporadically, Stan Getz, Haynes was playing in the band that Bud Powell had taken into the Orchid Club. He was happy with that, and at first he declined Parker’s offer to replace Max. In October he changed his mind: he went to join Bird at the Three Deuces. Sonny Rollins: “Roy was different. He was able to accompany Parker in the most wonderful way. He had his own sound and his own methods.” On the day of Bird’s funeral, Chan would tell Haynes that Bird considered him the best drummer he’d ever had.

Parker’s quintet had another newcomer, the young trumpeter Robert Chudnick, alias Red Rodney. The choice surprised almost everybody, including Red: “I protested for a moment. I said, ‘I’m not ready to work with you.’ And I even mentioned that Fats Navarro was on the scene and he certainly was more ready. [And] Kenny Dorham, who I thought was better. Those are the two names I mentioned. And his reply was, ‘Maybe, but I know a good trumpet player when I hear one and I want you.’”(5). Despite his tender years, Red Rodney had been a member of a number of big bands — Gene Krupa, Buddy Rich, Claude Thornhill, Woody Herman et al — and was an early bop convert. He was no Dizzy, of course, nor a Miles or a Kenny Dorham, but in Rodney’s playing Bird had heard how it might complement his own, and the trumpeter’s suitability became obvious in the course of their performances. Almost all of these were recorded with an audience, as Red Rodney only rarely went into a studio in Parker’s company…

On December 15th, fronting this quintet, Charlie Parker was obviously the star at the inauguration of Birdland (formerly The Clique), a club which vaunted itself to be “The Jazz Corner of the World”. Taking part in the festivities were Max Kaminsky, Lester Young, Stan Getz, Lennie Tristano, Lee Konitz, Hot Lips Page and, yes, Harry Belafonte, for whom calypsos were still in the distant future.

Ten days later, Bird, Red Rodney, Al Haig, Tommy Potter and Roy Haynes trouped onstage at Carnegie Hall for a mammoth concert presented by Leonard Feather and Symphony Sid and billed as “The Stars of Modern Jazz”. Following them were Bud Powell and his trio, Miles Davis, Stan Getz, Kai Winding, Sarah Vaughan, and Lennie Tristano leading his own quintet. Bird and his partners performed an exemplary set of tried and trusted “classics” like Ornithology, Cheryl (in which Parker, greeted with an ovation by the audience, quotes Armstrong’s solo on West End Blues), Ko Ko, Bird of Paradise — a masterpiece — and Now’s the Time. It might be worth noting that in the mid-Fifties this part of the concert was released in France by the Hot Club of Lyon, on a not-for-sale 10” LP which was no doubt one of the first issues of its kind.

Charlie Parker, Fats Navarro, Bud Powell, Curley Russell and Art Blakey… it was a reunion that definitely justified the “All Stars” label. Charlie Parker’s discography is known for its mysteries and uncertainties, but this one takes the biscuit. The venue and the dates for this summit meeting have been discussed for years. Michel Delorme’s “Commented Discography of the Public Recordings of Charlie Parker” (6) designates the venue as the Café Society, and this appeared on a Japanese LP. Since then, there’s been a consensus of opinion over the fact that the event actually took place at Birdland, given that Bud Powell was a regular there. Was this a one-off concert? Various accounts — from Little Jimmy Scott among others — corroborate that hypothesis, comforted by a kind of uniformity in the sound-takes. Yet three different dates appear on the labels of “Boris Rose Records” — Norman R. Saks’ collection — which reproduce part of the performances, i.e. May 1 and May 8, plus June 1, whereas most discographies agree on the dates May 15-16, based on the inscription appearing on a can of tape. If you thought the problem could be solved by taking a look at the Birdland programme, you’d be wasting your time: the small print on the relevant page in Down Beat says, “Change of personnel always erratic, but offering will be definitely modern jazz.” No comment…

Some historians have their doubts. Various eye-witnesses, including Ira Gitler and Dan Morgenstern, described Fats Navarro’s condition as pitiful in the months before he died of tuberculosis (combined with a serious addiction to heroin) on July 7th 1950. But what Fats plays in the course of the evening — his chorus on The Street Beat is the longest that has survived the years — is not the work of a musician in any way diminished. Navarro plays even more brilliantly here than in September 1949 on his last record-date for Don Lanphere. Listening to Fats on Dizzy Atmosphere, and the precision he shows in the unison parts of Little Willie Leaps taken at high speed, not to mention his version of A Night in Tunisia, it’s not unreasonable to situate these pieces at the beginning of 1950 (or even earlier, unless he’d gone miraculously into remission).

At his absolute best, and served by a Bud Powell in superlative form — and for once unencumbered by the need to take preventive action, as the entente between Powell and Parker wasn’t always cordiale —Bird hits the heights on his way through ‘Round Midnight and This Time the Dream’s on Me. When he gets to Out of Nowhere and, to a lesser extent, Little Willie Leaps, he takes tunes that had been in his repertoire for a long time and turns them into a form of abstract art. As Dan Morgenstern pointed out, his approach is similar to that of Lee Konitz or Warne Marsh; and they were familiar to Bird: they were at the opening of Birdland and at Carnegie Hall, as members of Lennie Tristano’s quintet.

On Ornithology, perhaps the most accomplished work that came out of it all, and a piece carried by a rhythm section in a state of grace — urged on by the high-pitched voice of Pee Wee Marquette yelling “Goooo, Baaaby” — Bird once again proves that he wasn’t boxing in quite the same category as his sidekicks, however talented they were. In an excellent mood, Bird quotes the Habanera from “Carmen” again before laying into I’ll Remember April in a high-flying series of exchanges with Art Blakey; the drummer is in a state of frenzy, dropping his bombs with largesse and relevance in equal doses. In his difficult role as the anchor, Curley Russell is faultless. Not a single blot on a session that remains exceptional, whichever way you look at it. So far, so good.

Embraceable You inspires Bird to play a solo filled with sensibility, but inviting Little Jimmy Scott along was a mistake: his vocals will only find pardon in the ears of his unconditional fans. In his defence, let it be said that the rhythm section doesn’t make life easy for him, and Bud Powell is manifestly irritated by the intrusion. In fact, he lets Walter Davis Jr. take his place; on Cool Blues, Walter picks up (as best he can) the accompaniment which Erroll Garner had invented for the original version recorded for Dial. Here it seems that Tommy Potter and Roy Haynes have replaced Russell and Blakey.(7)

Following Dean Benedetti’s example — he did the same thing for his own satisfaction and guidance — some musicians with a fascination for Bird took pains to preserve his choruses for posterity, using a motley array of recorders in conditions that were often insane. Their efforts were quite clandestine of course, to the great dismay of club-owners and other concert-organizers, and anecdotes abound on the subject, ranging from holes drilled through walls, to toilets with an “Out of Order” sign on the door to conceal budding sound-engineers… One such musician with a Bird fascination was saxophonist Don Lanphere, and he was busy with his gear on one particular Saturday at the St. Nicholas Arena.

The acoustics weren’t going to help him much: transformed into a dancehall for the occasion, the St. Nicholas Arena was usually a home for prize-fights. Was it the fact that Bird was playing for a totally unbiased crowd? Whatever the reason, Parker played with a freedom that had rarely been equalled up until then. Despite their imperfect sound and their regrettable existence as fragments, these bursts of Bird contain dazzling flashes whose audacity still comes as a surprise more than half a century later. And as for Bird’s exchanges with the young Chudnick/Rodney on Scrapple from the Apple, Ornithology-1, Confirmation or Hot House, they show that Parker made exactly the right decision when he chose his new trumpeter.

Over various listening-sessions and after private copies began circulating, the St. Nicholas Arena recordings acquired a legendary reputation, so much so that at the end of the Fifties they were issued by Jazz Workshop — a sub-label of the recently-founded Debut Records owned by Charles Mingus and Max Roach — in two volumes. Unlike its companion, “Bird on 52nd Street”, which is of lesser interest, the volume “Bird at St. Nick’s” is not be ignored by any aficionado.

Adapted by Martin Davies from the French text of Alain Tercinet

© 2014 Frémeaux & Associés

(1) From the booklet in the set “The Complete Charlie Parker on Verve”, Verve Records.

(2) Robert Reisner, “Bird: The Legend of Charlie Parker”, Da Capo Press, 1977.

(3) Norman Granz in 1984, speaking to Bill Kirchner (internet).

(4) as (1).

(5) Ben Sidran, “Talking Jazz, an Oral History”, Da Capo Press, 1995.

(6) Jazz Hot N° 207, March 1965.

(7) Is Fats Navarro still the trumpeter? No doubt about it, according to Leif Bo Petersen & Theo Rehak (“The Music and Life of Theodore ‘Fats’ Navarro”, Studies in Jazz N°59, The Scarecrow Press, Lanham, Maryland, 2005). Laurence O. Koch says it’s Red Rodney (“Yardbird Suite”, Northeastern University Press, 1999). This seems doubtful given that Rodney had just had his appendix removed.

DISCOGRAPHICAL NOTES

JATP, Jazz at the Philharmonic

Three pieces have recently been re-discovered — so naturally they couldn’t be included here — featuring Ella Fitzgerald, and they can be added to the CD reissues of the concert. Probably absent on Flying Home (Flip Phillips plays it), Parker contributes to How High the Moon and Perdido.

Preserved on an almost inaudible transcription-disc (together with fragments of Lover Come Back to Me, Bean and the Boys and The Man I Love — these last two without Parker), an incomplete version of Stuffy with Coleman Hawkins has also had various dates attributed to it. Most references situate the event in June, whereas the calendar of JATP appearances included in the booklet inside the boxed-set “The Complete Jazz at the Philharmonic on Verve, 1944/1949” makes no mention of any concert at that time. Some people think Stuffy might be taken from the concert of September 17th preceding the set played at midnight.

Fats Navarro, Charlie Parker & the Bud Powell Trio

In their Charlie Parker discography, Piet Koster and Dick M. Bakker, like Tom Lord, Walter Bruyninckx and Jorgen Grunnet Jepsen, indicate the origins of these tapes as “broadcast”. For Norman Saks, Leonard Bukowski and Robert M. Bregman, the authors of “The Charlie Parker Discography”, these are private recordings, which is also the opinion of Tony Williams, who says Bill Hirsh was responsible on behalf of Boris Rose. What is certain is that that these performances were part of the resources amassed by the latter, Boris Rose, an unrepentant “broadcast” collector, and that he copied parts of them on request before issuing them on LPs with quaint names. This Birdland session has been known to collectors for a long time because it appears in the Charlie Parker discography included in Vol. 6 of Jorgen Grunnet Jepsen’s “Jazz Records 1942-1962” (1963).

Wahoo: entitled Perdido in numerous releases, this piece is often amputated with the removal of the beginning of Bud Powell’s solo (after Fats Navarro).

A Night in Tunisia: Despite the absence of Parker the performance is included here thanks to Fats Navarro’s trumpet.

There is one additional title, Conception / Deception, on which Miles Davis, J. J. Johnson and Brew Moore join the Cool Blues line-up. It isn’t included in this set because the sound is mediocre and Parker doesn’t take a solo.

Discographie - CD 1

JAZZ AT THE PHILHARMONIC

Roy Eldridge (tp)?; Tommy Turk (tb)?; Charlie Parker (as)?; Lester Young, Flip Phillips (ts)?; Hank Jones (p)?; Ray Brown (b)?; Buddy Rich (dm). Carnegie Hall, NYC, 18/9/1949

1. THE OPENER (Shrdlu) (Clef EP vol. 12/mx. 382/3/4) 12’46

2. LESTER LEAPS IN (L. Young) (Clef EP vol. 12/mx. 385/6/7) 12’29

3. EMBRACEABLE YOU (G. & I. Gershwin) (Clef EP vol. 13) 10’41

4. THE CLOSER (Shrdlu) (Clef EP vol. 13) 10’56

CHARLIE PARKER with STRINGS

Charlie Parker (as)?; Mitch Miller (oboe, engl-horn)?; Bronislaw Gimpel, Max Hollander, Milton Lomask (vln)?; Frank Brieff (vla)?; Frank Miller (cello)?; Meyer Rosen (harp)?; Stan Freeman (p); Ray Brown (b)?; Buddy Rich (dm)?; Jimmy Carroll (arr, cond). NYC, (?) and 30/11/1949

5. JUST FRIENDS (J. Klenner, S. M. Lewis) (Mercury/Clef 11036/mx. 319-5) 3’31

6. EVERYTHING HAPPENS TO ME (M. Dennis, T. Adair) (Mercury/Clef 11036/mx. 320-3) 3’16

7. APRIL IN PARIS (V. Duke, E. Y. Harburg) (Mercury/Clef 11037/mx. 321-3) 3’07

8. SUMMERTIME (G. Gershwin, DuBose Heyward) (Mercury/Clef 11038/mx. 322-2) 2’46

9. I DIDN’T KNOW WHAT TIME IT WAS (R. Rogers, L. Hart) (Mercury/Clef 11038/mx. 323-2) 3’13

10. IF I SHOULD LOSE YOU (R. Rainger, L. Robin) (Mercury/Clef 11037/mx. 324-3) 2’48

CHARLIE PARKER QUINTET

Red Rodney (tp)?; Charlie Parker (as)?; Al Haig (p)?; Tommy Potter (b)?; Roy Haynes (dm).

Voice of America, program n° 7, Carnegie Hall, NYC, 24/12/1949

11. Annonce/ ORNITHOLOGY (C. Parker, B. Harris) (Hot Club de Lyon, unumbered) 5’33

12. CHERYL (C. Parker) (Hot Club de Lyon, unumbered) 5’00

Discographie - CD 2

CHARLIE PARKER QUINTET

Red Rodney (tp)?; Charlie Parker (as)?; Al Haig (p)?; Tommy Potter (b)?; Roy Haynes (dm).

Voice of America, program n° 7, Carnegie Hall, NYC, 24/12/1949

1. KOKO (C. Parker) (Hot Club de Lyon, unumbered) 5’01

2. BIRD OF PARADISE (C. Parker) (Hot Club de Lyon, unumbered) 6’06

3. NOW’S THE TIME (C. Parker) (Hot Club de Lyon, unumbered) 5’10

FATS NAVARRO, CHARLIE PARKER & THE BUD POWELL TRIO

Fats Navarro (tp)?; Charlie Parker (as)?; Bud Powell (p)?; Curley Russell (b)?; Art Blakey (dm).

Birdland, NYC, poss. early 1950 or 15 - 16/5/1950

4. 52nd STREET THEME (T. Monk) (Jazz Cool JC101) 1’33

5. WAHOO (B. Harris) (Jazz Cool JC102) 6’36

6. ‘ROUND MIDNIGHT (T. Monk, C. Williams, B. Hanighen) (Jazz Cool JC101) 5’14

7. THIS TIME THE DREAMS ON ME (H. Arlen, J. Mercer) (Ozone 4) 6’21

8. DIZZY ATMOSPHERE (D. Gillespie) (Ozone 4) 7’03

9. A NIGHT IN TUNISIA (D. Gillespie, F. Paparelli) (poss. aircheck) 5’36

10. MOVE/52nd STREET THEME (T. Monk) (Jazz Cool JC101) 6’49

11. THE STREET BEAT ( C. Thompson) (Jazz Cool JC102) 9’19

12. OUT OF NOWHERE (J. Green, E. Heyman) (Ozone 9) 6’11

13. LITTLE WILLIE LEAPS (M. Davis)/

52nd STREET THEME (T. Monk) (Meexa Discox 1776) 5’54

Discographie - CD 3

FATS NAVARRO, CHARLIE PARKER & THE BUD POWELL TRIO

Fats Navarro (tp)?; Charlie Parker (as)?; Bud Powell (p)?; Curley Russell (b)?; Art Blakey (dm).

Birdland, NYC, poss. early 1950 or 15 - 16/5/1950

1. ORNITHOLOGY (C. Parker, B. Harris) (Jazz Cool JC101) 7’54

2. I’LL REMEMBER APRIL (D. Raye, G. DePaul, P. Johnstone /52nd STREET THEME (T. Monk)

(poss. aircheck) 9’37

Add Little Jimmy Scott (voc)

3. EMBRACEABLE YOU (G. & I. Gershwin) (Meexa Discox 1776) 6’05

Fats Navarro (tp)?; Charlie Parker (as)?; Walter Bishop Jr. (p)?; Tommy Potter (b)?; Roy Haynes (dm).

Same place and dates

4. COOL BLUES (C. Parker) (Jazz Cool JC101) 6’51

5. 52nd STREET THEME (T. Monk) (Ozone 9) 2’08

CHARLIE PARKER QUINTET

Red Rodney (tp)?; Charlie Parker (as)?; Al Haig (p)?; Tommy Potter (b)?; Roy Haynes (dm).

St Nicholas Arena, NYC, 18/2/1950

6. I DON’T KNOW WHAT TIME IT WAS (R. Rogers, L. Hart) (Jazz Workshop JWS 500) 2’36

7. ORNITHOLOGY (C. Parker, B. Harris) (Jazz Workshop JWS 500) 3’28

8. EMBRACEABLE YOU (G. & I. Gershwin) (Jazz Workshop JWS 500) 2’18

9. VISA (C. Parker) (Jazz Workshop JWS 500) 2’58

10. I COVER THE WATERFRONT (J. Green, E. Hayman) (Jazz Workshop JWS 500) 1’45

11. SCRAPPLE FROM THE APPLE (C. Parker) (Jazz Workshop JWS 500) 4’38

12. STAR EYES (G. DePaul, D. Raye) (Jazz Workshop JWS 500) 2’54

13. 52nd STREET THEME I (T. Monk) (Jazz Workshop JWS 500) 0’11

14. CONFIRMATION (C. Parker) (Jazz Workshop JWS 500) 3’14

15. OUT OF NOWHERE (J. Green, E. Heyman) (Jazz Workshop JWS 500) 2’18

16. HOT HOUSE (T. Dameron) (Jazz Workshop JWS 500) 3’46

17. WHAT’S NEW ? (R. Haggart, J. Burke) (Jazz Workshop JWS 500) 2’44

18. NOW’S THE TIME(C. Parker) (Jazz Workshop JWS 500) 4’16

19. SMOKE GETS IN YOUR EYES (J. Kern, O. Harbach) (Jazz Workshop JWS 500) 3’34

20. 52nd STREET THEME II (T. Monk) (Jazz Workshop JWS 500) 1’13

« ?Charlie Parker a réalisé tout ce que j’aurais voulu faire et bien plus encore – il était vraiment génial, voyez-vous. Il était capable d’inventer des tas de choses et de le faire d’une façon si mélodieuse que n’importe qui, l’homme de la rue, pouvait les écouter – Ce que je n’ai pas réussi, ce à quoi j’aimerais arriver.?»

John Coltrane

“Charlie Parker did all the things I would like to do and more – he really had a genius, see. He could do things and he could do them melodiously so that anybody, the man in the street, could hear – that’s what I haven’t reached, that’s what I’d like to reach.”

John Coltrane

CD Intégrale Charlie Parker vol. 7 Just friends 1949-1950, Charlie Parker © Frémeaux & Associés 2014.