- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

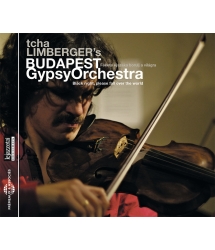

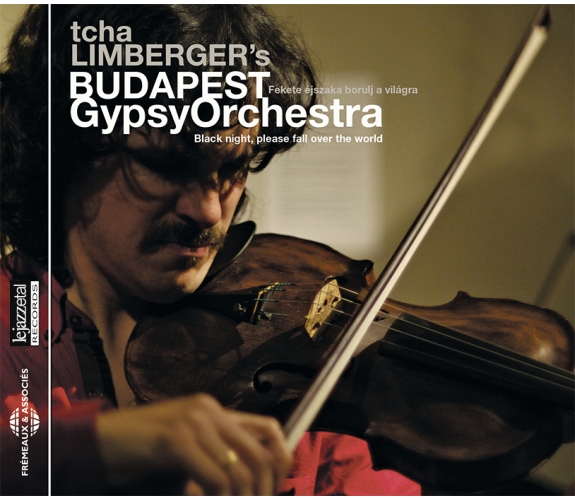

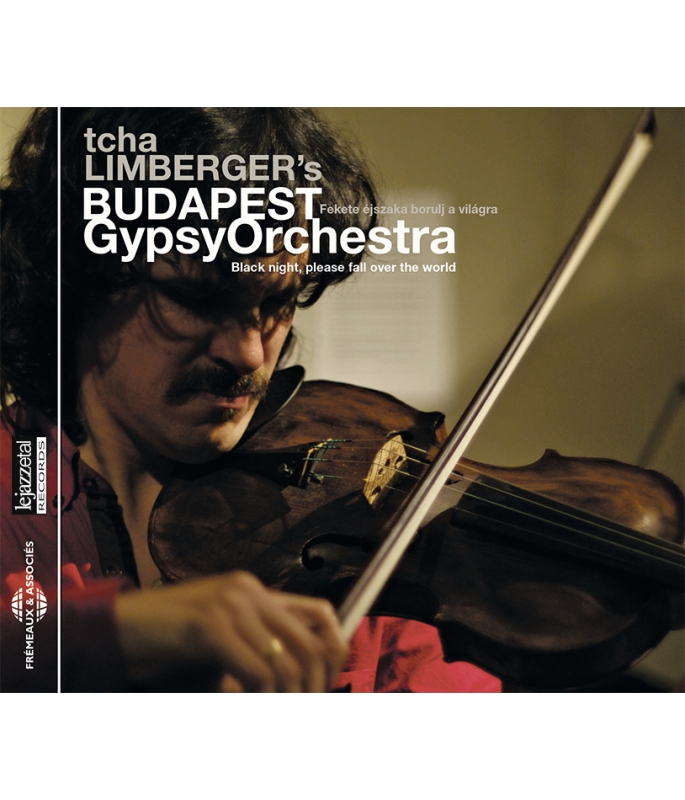

BLACK NIGHT, PLEASE FALL OVER THE WORLD / FEKETE EJSZAKA BORULJ A VILAGRA

TCHA LIMBERGER

Ref.: FA8524

EAN : 3448960852425

Artistic Direction : DAVE KELBIE

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Total duration of the pack : 1 hours 12 minutes

Nbre. CD : 1

BLACK NIGHT, PLEASE FALL OVER THE WORLD / FEKETE EJSZAKA BORULJ A VILAGRA

BLACK NIGHT, PLEASE FALL OVER THE WORLD / FEKETE EJSZAKA BORULJ A VILAGRA

Born into a family of famous gypsy musicians in Belgium, Tcha Limberger is a violinist whose sincerity is as attractive as his virtuosity when he wields his bow. Noting that gypsy jazz had an American matrix — threads of New Orleans and Swing — he took a closer interest in the original music of the Hungarian gypsies known as Tziganes who settled in Central Europe. He went to Hungary for a year and a half, an initiatory voyage on which he met with the best musicians, also learning Hungarian. In 2009 he founded the Gypsy Budapest Orchestra with support from Dave Kelbie, the great British producer of Evan Christopher, Fapy Lafertin etc. Today, Limberger’s violin brilliantly reincarnates Magyar nota, the great popular repertoire of Hungary (between folk and classical music) that had gone into decline. Tcha Limberger is internationally recognized: he triumphed at the 2015 opening of World Music Expo (Womex), and received France Musique’s World Award at Babel Med the same year. This recording have been nominated in the Songlines Music Awards 2016. Augustin BONDOUX & Patrick FRÉMEAUX

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Racz Bela emlekereTcha Limberger' Budapest Gypsy Orchestra00:08:122014

-

2Szomoruan zug-bug a szelTcha Limberger' Budapest Gypsy Orchestra00:08:592014

-

3Fekete ejszaka borulj a vilagraTcha Limberger' Budapest Gypsy Orchestra00:03:422014

-

4Klarinet szoloTcha Limberger' Budapest Gypsy Orchestra00:06:012014

-

5Csokolom a kis kezedetTcha Limberger' Budapest Gypsy Orchestra00:12:032014

-

6Cimbalom szoloTcha Limberger' Budapest Gypsy Orchestra00:04:392014

-

7Ha nem lenne napfeny a virag sem nyilnaTcha Limberger' Budapest Gypsy Orchestra00:09:042014

-

8De szeretnek de szeretnekTcha Limberger' Budapest Gypsy Orchestra00:03:052014

-

9Cello szoloTcha Limberger' Budapest Gypsy Orchestra00:07:242014

-

10Szakadozo rongy vonodat mit sajnalod !Tcha Limberger' Budapest Gypsy Orchestra00:06:132014

-

11Kiballagok a vasuthozTcha Limberger' Budapest Gypsy Orchestra00:03:122014

TCHA LIMBERGER FA8524

tcha LIMBERGER’s

BUDAPEST Gypsy Orchestra

Fekete éjszaka borulj a világra

Black night, please fall over the world

Tcha Limberger

Voici mes premières impressions lorsqu’à Londres, au printemps 2014, j’ai rencontré Tcha Limberger pour la première fois. Un homme maigre, très beau, le teint mate, une fine moustache, de belles mains, gracieux, très intelligent et s’exprimant avec une extrême aisance. Un homme transporté par le fait de jouer de la musique et bien sûr, non voyant.

J’étais pourtant au courant, bien avant notre rencontre, que Tcha était non voyant et j’étais fasciné qu’un homme aussi remarquable ait réalisé (et continue) autant de choses en ayant grandi sans la vue. Tcha m’a raconté qu’enfant, sa mère a toujours insisté pour qu’il aille dans une école publique avec d’autres enfants, plutôt que dans une école pour aveugles. « Je pense être le premier enfant non voyant de Belgique à avoir fait cela » raconte-t-il, en insistant que toute sa vie on ne l’a jamais empêché d’entreprendre quoi que ce soit à cause de son handicap. Bien au contraire, il a toujours été encouragé. Ainsi, lorsqu’il eut envie d’apprendre le hongrois (sa passion était tellement forte pour le violon tzigane de Hongrie, qu’il fit son premier voyage à Budapest à 19 ans) il s’y est mis très simplement, alors qu’il s’agit pourtant de l’une des langues les plus difficiles à apprendre. « J’avais un bon livre que j’ai fait traduire en braille, nous sommes ensuite allés à l’ambassade de Hongrie en Belgique, où il m’ont présenté une enseignante qui m’a été d’une grande aide ».

Bien évidemment, Tcha n’est pas le premier musicien talentueux pour qui ce handicap visuel n’a pas été un frein à l’épanouissement artistique. Toutefois, je ne connais pas beaucoup de musiciens (handicapés comme valides) qui ont si brillamment réussi à s’immerger dans une culture étrangère à celle dans laquelle ils sont nés. En effet, la première fois que j’ai écouté la musique de Tcha, j’ai pensé qu’il devait être un musicien hongrois qui avait emprunté un nom de scène étranger. Cela m’a surpris lorsque j’ai appris qu’il était né dans une famille belge, car je prenais pour acquis le fait que les Roms de cette partie du Nord de l’Europe (Belgique, Pays-Bas et France), ont pour tradition de jouer uniquement du « jazz manouche », lui-même directement inspiré des enregistrements des années 1930 de Django Reinhardt. Lorsque je parle de tout cela avec Tcha, il me dit qu’il est très familier avec la tradition manouche issue de Django et qu’il adore la jouer à la guitare, mais qu’il est plus réservé quant à la façon dont est jouée cette musique aujourd’hui : « Le jazz manouche est un folklore simplifié issu du jazz. Django ne jouait pas du « jazz manouche », mais du jazz new-orleans puis du be-bop ».

En parlant avec Tcha j’ai découvert qu’il n’était pas seulement un formidable musicien (et linguiste), mais que c’était également un grand penseur, avec un fort sens esthétique, et très critique à l’égard de tout ce qui est markété « Gypsy » de nos jours. En plus de 30 ans j’ai interviewé de nombreux musiciens, Tcha fait partie de cette rare veine d’instrumentistes qui sont aussi habiles dans le verbe qu’ils le sont avec leur instrument de prédilection. C’est une bénédiction de bien des façons. Spécialement lorsque cela permet à Tcha de raconter sa propre histoire, sans que j’ai besoin de retrousser mes manches pour y ajouter beaucoup d’informations.

« Je suis né à Bruges. Ma mère est Flamande et mon père est Manouche. Les Manouches sont une branche issue des Sintés. Les Roms qui viennent d’Europe de l’Est parlent un dialecte très différent du romani que nous parlons en Belgique. J’ai grandi dans un environnement plus flamand que manouche (lorsque j’ai eu 3 ans nous sommes allés nous installer dans une maison, ma mère voulait m’inscrire à la crèche). A 6 ans j’ai commencé à apprendre à jouer du flamenco. J’étais fou des disques de Manitas De Plata, qui, je l’ai réalisé plus tard, n’étaient pas du vrai flamenco, mais une version bâtarde de cette musique. Mon père jouait dans le groupe de l’un des fils de Manitas, il était revenu du pèlerinage gitan de Sainte Marie de la Mer avec plein de disques gramophones. C’est comme cela que j’ai pu connaitre cette musique. J’ai été vite en contact avec le vrai flamenco espagnol de Camaron de la Isla et Paco de Lucia, ce qui m’a énormément impressionné. Au même moment je m’intéressais à des musiques de partout dans le monde, les gens me ramenaient tout le temps des cassettes de leurs voyages car ils savaient que j’étais un passionné de musique. Celle qui m’impressionnait le plus avec le flamenco était alors la musique bolivienne andine, quechua et aymara. J’ai appris comment jouer cette musique et ai d’ailleurs joué dans un groupe quechua en Belgique jusqu’à mes 20 ans.

« Lorsque j’ai eu 12 ans, j’ai compris que si je voulais jouer du vrai flamenco, je devais aller vivre en Espagne. J’étais évidemment trop jeune pour faire cela, je me suis alors intéressé à la clarinette jazz new-orleans. J’ai rejoins le groupe du frère de mon père à la clarinette et nous jouions du jazz manouche (qui emprunte beaucoup au new-orleans) mais également de la musique hongroise. A 13 ans j’ai commencé à jouer de la guitare et de la clarinette en trio avec mon père et son plus jeune frère. J’ai également travaillé avec une troupe de danse contemporaine jusqu’à mes 23 ans. C’était une époque importante pour moi car cela m’a permis de rencontrer Dick Van der Harst, un Hollandais qui vit en Belgique. Il compose et joue de la guitare et en connait tout un rayon en musique. J’ai aussi rencontré Koen Decauter, le leader du Waso Jazz Quartet (mon père a joué avec eux un long moment) et Herman Schamp qui est un grand guitariste classique, fin connaisseur de Django et de la musique paraguayenne. Il m’a initié à la musique classique. Je l’ai rencontré quand j’avais 14 ans et tout ceci est venu se confondre avec ma quête personnelle dans la recherche de tout ce qui est réellement authentique : à vrai dire, je ne suis pas un puriste, mais la fusion ne m’inspire pas beaucoup. La musique acoustique est importante pour moi, je préfère jouer sans micros, sans amplification.

« A l’adolescence j’ai commencé à avoir de plus en plus d’engouement pour la musique hongroise et j’ai voulu approfondir mes recherches sur la musique de Toki Horvath (bien que son nom signifie « le Croate » il s’agit bien d’un Hongrois) mais à cette époque je ne jouais pas de violon. Je ne pensais même pas encore à pratiquer cet instrument, mais après l’écoute des disques de mon grand-père violoniste, je suis devenu déterminé à en apprendre la pratique. Nous les Sintés, nous sommes un peu butés – tout le monde veut apprendre à jouer de la guitare maintenant. J’avais 17/18 ans, ce qui est un âge tardif pour commencer l’apprentissage du violon, mais fort heureusement c’est rapidement devenu mon instrument de prédilection. Lorsque Koen, mon père et moi, sommes allés jouer à Budapest, j’étais comme un coq en pâte, je me sentais très bien ! J’ai de suite compris, à 19 ans, que c’était ce que je voulais faire. Concernant la musique hongroise, le style originaire de Budapest possède des bases de musique classique, contrairement aux autres genres de musiques tsiganes. J’ai décidé d’apprendre le hongrois car j’ai rencontré Kallai Zsolt qui m’a dit : « tu ne seras capable de jouer cette musique correctement que si tu sais parler la langue ». Je sais désormais qu’il avait raison. Deux ans après, à l’âge de 23 ans, j’ai pu me rendre à Budapest et découvrir par moi-même ce dont on m’avait pourtant prévenu : la musique que je voulais jouer, la magyar nota était en train de mourir assez rapidement.

« La magyar nota est un type de chanson populaire apparu en Hongrie à la fin du XVIIIe siècle. Cette musique a été inventée par les nobles qui voulaient une musique de divertissement, jouée durant les réceptions, qui soit plus raffinée que les musiques paysannes d’alors. Cette nouvelle musique devint très vite populaire. Lorsque Bartock partit étudier les musiques folkloriques des villages de Transylvanie, c’est la magyar nota qui avait remplacé toute la vraie musique traditionnelle, il dû faire beaucoup d’efforts pour réussir à la trouver. Cette musique était tellement populaire qu’à la fin du XIXe siècle chacun des 75 restaurants de Budapest disposait d’au minimum 3 à 4 groupes pour jouer la magyar nota toute la nuit. Je me suis rendu compte que la mort lente de cette musique était due en partie au fait que les gens la considèrent comme mielleuse et guimauve.

« Le répertoire que je joue est très compliqué et difficile à jouer. En tant que premier violon, tu diriges le groupe, qui regarde notamment la manière dont tu tiens l’archet. J’essaye de trouver des musiciens qui aiment jouer cette musique : la plupart des musiciens tsiganes qui en jouent aiment cela, mais sont très fermés à l’encontre des étrangers. Heureusement pour moi j’ai rencontré Horvart Belo, qui m’enseigna cette musique pendant 18 mois. Il avait reçu une formation classique et à 17 ans, il était déjà très impressionnant. Il m’a beaucoup aidé, il fallait que je trouve mon propre style, cela m’a pris des années. De retour en Belgique j’avais été appelé un soir pour jouer avec un groupe local de musiciens Hongrois, j’étais très impressionné, des Hongrois voulaient que je joue avec eux ! J’ai joué toute la nuit et ça a très bien marché ! »

Depuis, Tcha est devenu l’un des fers de lance de la magyar nota hongroise. Son talent incroyable, couplé avec un travail de longue date avec des musiciens hongrois et roumains (qui continuent de jouer de la magyar nota dans sa forme originelle), lui ont permis de créer l’extraordinaire musique que l’on peut écouter sur cet album. Sur Fekete éjszaka borulj a vilagra (nuit noire s’il te plait, tombe sur le monde) Tcha et son Budapest Gypsy Orchestra ont accouché d’une musique extraordinaire. On y écoute le son authentique de la musique populaire hongroise du XIXe siècle, joué par des musiciens qui ont acquis leurs techniques instrumentales de leurs pères, qui eux-mêmes les détenaient de leurs aïeux.

Les musiciens ici présents (sauf Tcha) sont tous issus d’une caste tsigane dont les membres sont tous appelés soit « musiciens » ou « romungro » (littéralement « tsigane hongrois »). Ce nom a la même signification en Roumanie chez ceux que l’on nomme « lautari ». Les musiciens sont donc tous issus de familles d’artistes ; ils ont été triés sur le volet par Tcha, parce qu’ils ont tous une connaissance, ainsi qu’une grande passion pour ce vieux répertoire. Ils sont considérés à Budapest comme des maitres de leurs instruments. Il faut souligner que le violoncelliste est le dernier joueur de violoncelle à connaitre ce répertoire (les mélodies étaient souvent jouées au violoncelle à l’unisson avec la voix et le violon).

Qu’une musique aussi étrange, d’une extraordinaire beauté, soit désormais sur le déclin et soit reliée au présent et au monde par un musicien belge relève en quelque sorte de la tragédie. Mais cet album est une fête, il ne s’agit pas de lamentation, car Tcha et ses musiciens jouent une musique extrêmement raffinée. En effet, la musique qu’il a choisi d’enregistrer est ancienne et peu, voire plus, jouée aujourd’hui. Cette dernière n’a rien à voir avec l’estampillage « Danses hongroises de Brahms », que l’on retrouve dans les groupes qui jouent la magyar nota de nos jours.

Garth Cartwright

Auteur de “Princes Amongst Men: Journeys With Gypsy Musicians”

www.garthcartwright.com

TCHA LIMBERGER

Here are my initial impressions upon meeting Tcha Limberger in London in spring, 2014. Slim. Handsome. Tan skin. Light moustache. Beautiful hands. Graceful. Highly intelligent. Extremely articulate. A man consumed with making music. And, of course, blind.

I was well aware that Tcha is blind before we met and it fascinated me how this remarkable man who has achieved – and continues to achieve – so much managed to do so having grown up sightless. Tcha explained to me that as a small child his mother insisted he go to a normal school with other children rather than a school for the blind. “I believe I was the first blind child in Belgium to do this,” he explained, noting that throughout his life he had never been told he could not do things because of his lack of sight. Instead, he was always encouraged. Thus, when he decided that he needed to learn the Hungarian language – so great was his passion for Hungarian Gypsy violin music after his first trip to Budapest at the age of 19 – he simply got on with the task of learning this most difficult of languages. “I got a good book and had it translated into Braille and went to the Hungarian embassy in Belgium and they found a teacher for me and she was very helpful.”

Obviously, Tcha is not the first celebrated musician who refuses to let being blind stop him succeeding at his art. Yet I cannot think of many musicians – disabled or able bodied - who have so successfully immersed themselves in a culture quite foreign to that they were born into. Indeed, when I first heard Tcha’s music I thought he must be a Hungarian musician who had adopted a non-Hungarian surname. Learning he was born into a Belgian family surprised me in the sense that one takes it for granted that the Roma of that corner of northern Europe (Belgium, Holland, France) tend to make music in what is called the “Gypsy Jazz” tradition ie modelled very closely on Django Reinhardt’s 1930s recordings. Asking Tcha about this he noted that he was very familiar with the Django tradition and, while capable of playing it on guitar, holds reservations about much of the music now made in that genre: “Gypsy Jazz is a simplified folklore of jazz music. Django did not play Gypsy Jazz. He played New Orleans-style then be-bop.”

Speaking with Tcha I realised he is not simply a formidable musician and linguist but a thinker who has a strong sense of aesthetic purpose and a critique of much of what today is marketed as “Gypsy”. I have been interviewing musicians now for more than three decades and Tcha is amongst that rare breed who are as articulate with speech as they are upon their chosen instrument. Which is a blessing in many ways. Especially as it allows Tcha to tell his own story without me having to lean in and add lots of information.

“I was born in Bruge. My mother is Flemish and my father a Manouche Gypsy. The Manouche are a splinter division of the Sinti. The Roma who now arrive from Eastern Europe speak a very different dialect of Romani from that which we speak in Belgium. I grew up in a more Flemish than Gypsy environment – when I was three we moved into a house as my mother wanted me to attend a kindergarten. Aged six I started learning how to play flamenco guitar. I was excited about the recordings of Manitas De Plata which, I later realized, was not real flamenco but a bastardised version. My father was a musician who played in a band with one of Manitas’s son’s and had been to the Gitan Pilgrimage at St Maries de la Mer and returned with gramophone records so this is how I came to know this music. Pretty soon I got to hear real Spanish flamenco of Camaron de la Isla and Paco De Lucia and this impressed me hugely. At the same time I got interested in music from all around the world and people would bring me back tapes because people are always travelling and were aware I was keen to hear music. The music that impressed me most, alongside flamenco, was the Bolivian Indian music Quecha Atmara. I learnt how to play this kind of music and playing in a Quecha band in Belgium until I was twenty.

“When I was about twelve I decided that if I wanted to play the real flamenco I would have to go and live in Spain – obviously, I was too young to do so so I started getting interested in the clarinet in New Orleans jazz. I joined my father’s brother’s band playing clarinet and we played Gypsy jazz – which borrows a lot from New Orleans – and some Hungarian music too. De Piotto’s was our name (we were named after my grandfather). At 13 I started playing in a trio with my father and his youngest brother as a guitarist and clarinet player. I worked with a contemporary dance troupe and I did that until I was 23. It was an important time for me as it brought me in contact with Dick Van Der harst, a Dutch guy who ended up living in Belgium and plays guitar and composed. He knows a helluva lot of music. Also, I met Koen Decauter who is the leader of the Waso Jazz Quartet (my father played with them for a long time) and Herman Schamp who is an important classical guitarist who knows lots about Django and the music of Paraguay. He opened my ears to lots of classical music. I met him when I was 14 and all this mixed up with my continuous research for what is really authentic. I’m not a purist but I’m not attracted by a lot of fusion. I know that rock is something which never attracted me. Acoustic music is important to me. I prefer to play with no microphones, no PA.

“In my teens I got very interested in Hungarian music and I wanted to research the music of Toki Horvath (that means ‘the Croatian guy’ but he’s Hungarian) but, back then, I didn’t play violin. I didn’t even think of playing it but then I heard the recordings of my grandfather playing violin and I became determined to learn. We Sinti are silly – everyone just wants to play guitar now. I was 17/18 and this is a very late start to learn violin but, whatever, I’m happy as I started and it quickly really became my instrument. Koen and I and my father went to Budapest to play. It felt like sitting in a hot bath – it just felt so good! I knew then – at 19 – this is what I wanted to do. The Budapest style of Hungarian music uses a classical basis which is contrary to other Gypsy music styles. So I decided to learn Hungarian. Then I met Kallai Zsolt and he told me ‘you won’t be able to play this music correctly if you don’t speak Hungarian’. And I now know he was right. After two years, aged 23, I could go to Budapest and I found out what I had been warned about – the music I want to play, Magyar nota, is dying out very quickly.

“Magyar nota is Hungarian chanson music born at the end of the 1700s. It was a music invented by the Hungarian nobility who wanted a music that would suit their restaurants and tea houses and was not as rough as the village music. So it is a new music that got very popular very quickly. Bartok found this when he went out looking for the folk music in the villages of Transylvania – everywhere Magyar nota had taken over from real folk music. He struggled to find traditional folk music. Let me tell you how popular Magyar nota was in Hungary – at the end of the 19th Century there were 75 restaurants in Budapest with minimum three or four bands who played Magyar nota every night. I found out that the dying out of Magyar nota was due to people thinking it was very sugary, very cheesy.

“The repertoire I play is hugely complicated and difficult to play. As first violinist you lead the band – they look at how you hold your bow. I try to find people who like it – most of the Gypsy musicians who play Magyar nota like it but they are not that hospitable to outsiders. Fortunately, I found this teenager Horvart Belo who taught me for 18 months. He had classical training and, at 17, was just amazing. He really helped me. I had to find my own style. That cost some years. Back in Belgium I got called one night to come and play with a local Hungarian band and I was like ‘wow, Hungarians want me to play!’ I played all night and it clicked!”

Since then Tcha has become one of the foremost exponents of Hungary’s Magyar nota. His talent, deepened by a long engagement with Hungarian and Romanian Gypsy musicians who have continued to perform Magyar nota in the traditional style, allows him to create the extraordinary music found on this album. Fekete éjszaka borulj a világra (Black Night Please Fall Over The World) finds Tcha and his Hungarian Gypsy Orchestra creating extraordinary music. Here is the sound Hungarian popular music of the late 19th century played by musicians who have learnt their instrumental skill from their fathers who learnt from their fathers.

The featured musicians (apart from Tcha) are all from a Gypsy caste who are just called “musician”, or “Romungro” (literally “Hungarian Gypsy”) a name used by people referring to these musicians. This is similar in it’s meaning as ‘Lautari’ in Romania. The musicians’ in the band all from musician families and are hand picked by Tcha as all have an enthusiasm for and knowledge of the old repertoire. All are top players in Budapest on their instruments. A special case is the cellist; he being the only cellist left who even knows this old repertoire. (melodies very often played on cello in unison with voice or violin)

That a music of such eerie, extraordinary beauty should now be on the verge of extinction and relies on a Belgian violinist to present it to the world is close to being a cultural tragedy. But this album is about celebration, not mourning, as Tcha and his fellow musicians bring forth an exquisite Hungarian music. Indeed, the music Tcha has chosen to record on this album is old and little played today (if at all). The music here bares no relation to the touristic ‘Brahms-Hungarian dances’ style you would normally find today in a band playing Magyar nota.

Garth Cartwright

Author, Princes Amongst Men: Journeys With Gypsy Musicians

www.garthcartwright.com

Tcha Limberger’s

Budapest Gypsy Orchestra

Fekete éjszaka borulj a világra

Recorded at Stiwdio Felin Fach, Abergavenny

taithrecords.co.uk/studio

31 March, 1/2 April 2014

Engineered by Dylan Fowler & Dan Lawrence

Mixed by Dave Kelbie at Stiwdio Felin Fach

24/25 Oct, 4/5 Dec 2014 & 8/9/10/16 Feb 2015

Mastering by Minerva Pappi at Chartmakers, Helsinki

P 2014-2015 Lejazzetal Records

© 2016 Groupe Frémeaux Colombini under license from Lejazzetal

Produced by Lejazzetal Records, London

design & artwork by Dave Kelbie

assisted by Kathryn at Prestset

prestset.co.uk

manufactured by Frémeaux & Associés

Photos

Front/back cover & booklet front -

Richard Hammerton @thehammerton

Booklet inside - Paul Nicholas

paulnicholas.net

Sleeve notes by Garth Cartwright

garthcartwright.com

Translation (French) by Augustin Bondoux

Thanks to Mirella Hodzic, Linde Timmermans, Tivadar Fátyol, Balassi Institute London, Garth Cartwright, Roby Lakatos, Minerva Pappi, Yvonne Bauer, Dylan Fowler, Andy Whitehouse

Management: Lejazzetal London UK

Dave Kelbie, Lejazzetal

dave.kelbie@gmail.com

for info, tour dates and more

tchalimberger.com

lejazzetal.com

Contact :

Lejazzetal Records London UK Frémeaux & Associés

Dave Kelbie Coordination: Augustin Bondoux

dave.kelbie@gmail.com info@fremeaux.com

for CDs, tour dates and more... full catalogue

www.lejazzetal.com www.fremeaux.com

About the music I intend to play: to start off with, this music deserves to be re-appreciated in it’s essential form and for that reason I don’t intend to create a new style immediately. It should again be played by musicians who really want to play it. Of course, we will not try to sound like a Gypsy band out of 1920, but also we’ll not play current versions either. I would like to bring all these elements together that made me want to study this music, that still inspire me about this music, even when it seems to be dead already.

TCHA LIMBERGER

Fekete éjszaka borulj a világra

1. Rácz Béla emlékére (08:12)

In memory of Rácz Bela

2. Szomorúan zúg-búg a szél (08:59)

The sad sound of the wind

3. Fekete éjszaka borulj a világra (03:42)

(Nádor József) Black night please fall over the world

4. Klarinét szóló (06:01)

Clarinet solo

5. Csókolom a kis kezedet (12:03)

I kiss your little hand

6. Cimbalom szóló (04:39)

Cimbalom solo

7. Ha nem lenne napfény, a virág sem nyílna (09:04)

(Bányay Aladár, Egerszeghy Géza) If there were no sunlight, flowers would not blossom

8. De szeretnék, de szeretnék (03:05)

Oh how I would like, oh how I would like

9. Cello szóló (07:24)

Cello solo

10. Szakadozó, rongy vonódat mit sajnálod! (06:13)

(Sas Náci, Molnár Pápai Kálman) Don’t pity your old bow!

11. Kiballagok a vasúthoz (03:12)

(Kalmár Tibor snr, Kalmár Tibor jnr) I saunter out to the railway station

All arrangements by the orchestra

He plays Hungarian Gypsy music on such a high level that he is able to perform with the greatest Hungarian musicians, and even among them he gives an outstanding performance. When I listen to this album I feel like I am in the golden age of gypsy music. It sounds as though it were recorded before World War II, except that it was enhanced by 21st century technology and equipment.

In his music I involuntarily discover the style of Gyula Toki Horváth and Sándor Járóka Sr. It is a great honour for us Hungarians that such a young and talented Belgian Sinti musician plays this type of Hungarian Gypsy music that has already fallen into oblivion. I dare even say that with this album a new chapter could begin in the history of Gypsy music. Through the interpretation of Tcha Limberger and his great band I feel the rebirth of this precious historical music. This record gives me a lot of joy; I wish the same for all of you!

ROBY LAKATOS

Né en Belgique, issu d’une célèbre famille de musiciens manouches, Tcha Limberger séduit tant par la sincérité, que la virtuosité avec laquelle il brandit son archet. Partant du constat que le jazz manouche était une musique de matrice américaine (issue des courants new orleans et swing), il décide de s’intéresser aux origines de la musique tsigane qui prennent racine en Europe Centrale. Après un séjour de 18 mois en Hongrie, véritable quête initiatique au cours de laquelle il rencontre les plus grands musiciens et apprend à parler hongrois, il fonde en 2009 le « Gypsy Budapest Orchestra » épaulé par le grand producteur anglais Dave Kelbie (Evan Christopher, Fapy Lafertin). Le violoniste incarne avec brio un grand répertoire populaire en déclin qui se situe entre musique folklorique et classique : la « magyar nota ». Auréolé par une reconnaissance internationale, il a fait une ouverture triomphale au Womex 2015 et reçu le prix France Musique des musiques du Monde à Babel Med 2015. Ce disque vient d’être nominé aux Songlines Music Awards 2016.

Augustin BONDOUX & Patrick FRÉMEAUX

Born into a family of famous gypsy musicians in Belgium, Tcha Limberger is a violinist whose sincerity is as attractive as his virtuosity when he wields his bow. Noting that gypsy jazz had an American matrix — threads of New Orleans and Swing — he took a closer interest in the original music of the Hungarian gypsies known as Tziganes who settled in Central Europe. He went to Hungary for a year and a half, an initiatory voyage on which he met with the best musicians, also learning Hungarian. In 2009 he founded the Gypsy Budapest Orchestra with support from Dave Kelbie, the great British producer of Evan Christopher, Fapy Lafertin etc. Today, Limberger’s violin brilliantly reincarnates Magyar nota, the great popular repertoire of Hungary (between folk and classical music) that had gone into decline. Tcha Limberger is internationally recognized: he triumphed at the 2015 opening of World Music Expo (Womex), and received France Musique’s World Award at Babel Med the same year. This recording have been nominated in the Songlines Music Awards 2016.

Augustin BONDOUX & Patrick FRÉMEAUX

Limberger Tcha - violon

Ruszo István - violon

Olah Norbert - brácsa

Csikos Vilmos - basse

Fehér István - cimbalom

Lukács Csaba - clarinette

Szegfű Károly - violoncelle

1. Rácz Béla emlékére (08:12)

2. Szomorúan zúg-búg a szél (08:59)

3. Fekete éjszaka, borulj a világra (03:42)

4. Klarinét szóló (06:01)

5. Csókolom a kis kezedet (12:03)

6. Cimbalom szóló (04:39)

7. Ha nem lenne napfény, a virág sem nyílna (09:04)

8. De szeretnék, de szeretnék (03:05)

9. Cello szóló (07:24)

10. Szakadozó, rongy vonódat mit sajnálod! (06:13)

11. Kiballagok a vasúthoz (03:12)