- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

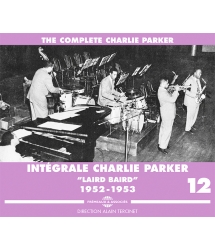

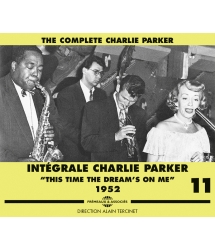

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

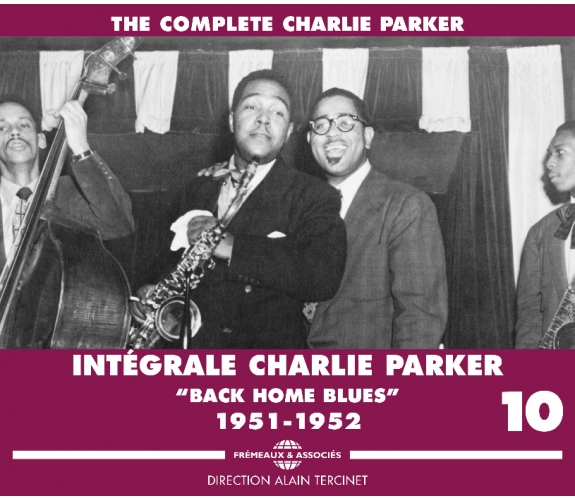

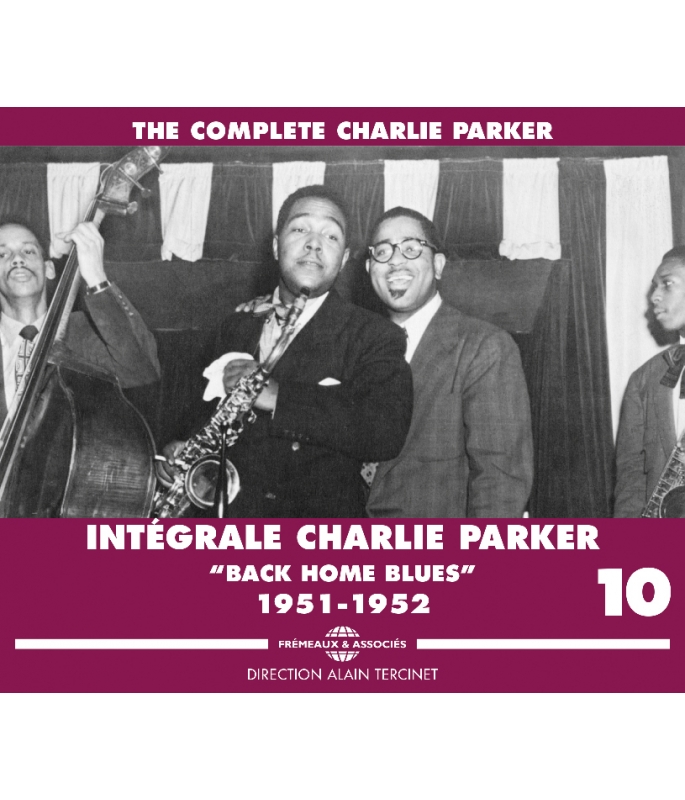

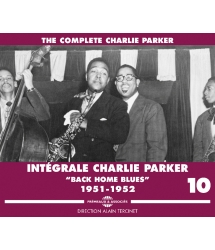

BACK HOME BLUES 1951-1952

CHARLIE PARKER

Ref.: FA1340

Artistic Direction : ALAIN TERCINET

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Total duration of the pack : 3 hours 6 minutes

Nbre. CD : 3

BACK HOME BLUES 1951-1952

BACK HOME BLUES 1951-1952

“My vote is definitely for Charlie Parker. I’ve worked with all the great names you mentioned, but Charlie Parker was the originator and innovator of the century.” Buddy de FRANCO

The aim of 'The Complete Charlie Parker', compiled for Frémeaux & Associés by Alain Tercinet, is to present (as far as possible) every studio-recording by Parker, together with titles featured in radio-broadcasts.

Private recordings have been deliberately omitted from this selection to preserve a consistency of sound and aesthetic quality equal to the genius of this artist.

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Blue‘ N BoogieCharlie Parker All-StarsDizzy Gillespie00:07:311951

-

2AnthropologyCharlie Parker All-Stars00:05:461951

-

3‘Round MidnightCharlie Parker All-StarsB. Hanighan00:03:311951

-

4Night In Tunisia/Jumpin' With Symphony SidCharlie Parker All-Stars00:05:201951

-

5Hot HouseCharlie Parker All-Stars00:04:251951

-

6Embraceable YouCharlie Parker All-StarsG. et I.Gershwin00:03:441951

-

7How High The Moon - OrnithologyCharlie Parker All-StarsNancy Hamilton00:05:231951

-

8Scrapple From The AppleCharlie Parker00:15:181951

-

9Lullaby In RhythmCharlie Parker00:12:301951

-

10Happy Bird BluesCharlie Parker00:02:521951

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1You Go To My HeadCharlie Parker with Woody Herman and his orchestraHaven Gillespie00:03:101951

-

2Leo The Lion ICharlie Parker with Woody Herman and his orchestra00:03:081951

-

3Cuban HolidayCharlie Parker with Woody Herman and his orchestra00:03:081951

-

4The Nearness Of YouCharlie Parker with Woody Herman and his orchestraN. Washington00:03:371951

-

5Lemon DropCharlie Parker with Woody Herman and his orchestra00:03:461951

-

6The Goof And ICharlie Parker with Woody Herman and his orchestra00:03:351951

-

7LauraCharlie Parker with Woody Herman and his orchestraJohnny Mercer00:02:581951

-

8Four BrothersCharlie Parker with Woody Herman and his orchestra00:03:531951

-

9Leo The Lion IICharlie Parker with Woody Herman and his orchestra00:03:141951

-

10More MoonCharlie Parker with Woody Herman and his orchestra00:03:211951

-

11Blues For AliceCharlie Parker Quintet00:02:521951

-

12Si SiCharlie Parker Quintet00:02:441951

-

13Swedish SchnappsCharlie Parker Quintet00:03:201951

-

14Swedish SchnappsCharlie Parker Quintet00:03:171951

-

15Back Home BluesCharlie Parker Quintet00:02:411951

-

16Back Home BluesCharlie Parker Quintet00:02:531951

-

17Lover ManCharlie Parker QuintetR. Ramirez00:03:311951

-

18All Of MeCharlie Parker/Lennie TristanoGerald Marks00:03:381951

-

19I Can'T Believe That You Re In LoveCharlie Parker/Lennie TristanoJ. McHugh00:04:231951

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1TemptationCharlie Parker Big BandA. Freed00:03:341952

-

2LoverCharlie Parker Big BandR. Rodgers00:03:091952

-

3Autumn In New YorkCharlie Parker Big Band00:03:311952

-

4Stella By StarlightCharlie Parker Big BandN. Washington00:03:001952

-

5Mama InezCharlie Parker QuintetE. Grenet00:02:561952

-

6La CucarachaCharlie Parker QuintetTraditionnel00:02:461952

-

7EstrellitaCharlie Parker QuintetA. Venosa00:02:461952

-

8Begin The BeguineCharlie Parker Quintet00:03:171952

-

9La PalomaCharlie Parker QuintetTraditionnel00:02:441952

-

10Night And DayCharlie Parker Big Band00:02:521952

-

11Almost Like Being In LoveCharlie Parker Big BandA.J. Lerner00:02:371952

-

12I Can'T Get StartedCharlie Parker Big BandIra Gershwin00:03:101952

-

13What Is This Thing Called LoveCharlie Parker Big BandCole Porter00:02:401952

-

14Hot HouseCharlie Parker/Dizzy Gillespie00:04:451952

-

15Cool BluesJerry Jerome All Stars00:04:231952

-

16OrnithologyJerry Jerome All StarsBenny Harris00:08:211952

CLICK TO DOWNLOAD THE BOOKLET

Int. Charlie Parker Vol. 10 FA1340

THE COMPLETE CHARLIE PARKER

INTÉGRALE CHARLIE PARKER

“BACK HOME BLUES”

1951-1952

Vol. 10

DIRECTION ALAIN TERCINET

« Je voterai définitivement pour Charlie Parker. J’ai travaillé avec tous les grands noms que vous avez mentionnés, mais Charlie Parker était le créateur et le novateur de ce siècle. » B. de Franco

“My vote is definitely for Charlie Parker. I’ve worked with all the great names you mentioned, but Charlie Parker was the originator and innovator of the century.” Buddy de Franco

CD 1

CHARLIE PARKER ALL-STARS

Station WJZ, Birdland, NYC, 31/3/1951

1. BLUE ‘N’ BOOGIE 7’29

2. ANTHROPOLOGY 5’46

3. ‘ROUND MIDNIGHT 3’31

4. NIGHT IN TUNISIA/ JUMPIN’

WITH SYMPHONY SID 5’17

CHARLIE PARKER ALL-STARS

Birdland, NYC, spring 1951

5. HOT HOUSE 4’23

6. EMBRACEABLE YOU 3’42

7. HOW HIGH THE MOON / ORNITHOLOGY 5’20

CHARLIE PARKER

Christy’s Restaurant, Framingham, Massachussets ? 4/1951

8. SCRAPPLE FROM THE APPLE 15’16

9. LULLABY IN RHYTHM 12’28

10. HAPPY BIRD BLUES 2’52

CD 2

CHARLIE PARKER WITH WOODY HERMAN AND HIS ORCHESTRA

Municipal Arena, Kansas City, 22/7/1951

1. YOU GO TO MY HEAD 3’08

2. LEO THE LION I 3’06

3. CUBAN HOLIDAY 3’06

4. THE NEARNESS OF YOU 3’35

5. LEMON DROP 3’44

6. THE GOOF AND I 3’33

7. LAURA 2’56

8. FOUR BROTHERS 3’51

9. LEO THE LION II 3’12

10. MORE MOON 3’18

CHARLIE PARKER QUINTET

NYC, 8/8/1951

11. BLUES FOR ALICE 2’50

12. SI SI 2’42

13. SWEDISH SCHNAPPS 3’18

14. SWEDISH SCHNAPPS 3’15

15. BACK HOME BLUES 2’39

16. BACK HOME BLUES 2’51

17. LOVER MAN 3’28

CHARLIE PARKER / LENNIE TRISTANO

Lennie Tristano’s studio, NYC, august 1951

18. ALL OF ME 3’36

19. I CAN’T BELIEVE

THAT YOU’RE IN LOVE 4’23

CD 3

CHARLIE PARKER BIG BAND

NYC, 22/1/1952

1. TEMPTATION 3’32

2. LOVER 3’07

3. AUTUMN IN NEW YORK 3’29

4. STELLA BY STARLIGHT 2’57

CHARLIE PARKER QUINTET

NYC, 23/1/1952

5. MAMA INEZ 2’54

6. LA CUCARACHA 2’44

7. ESTRELLITA 2’44

8. BEGIN THE BEGUINE 3’15

9. LA PALOMA 2’41

CHARLIE PARKER BIG BAND

NYC, 25/3/1952

10. NIGHT AND DAY 2’50

11. ALMOST LIKE BEING IN LOVE 2’35

12. I CAN’T GET STARTED 3’08

13. WHAT IS THIS THING

CALLED LOVE ? 2’37

CHARLIE PARKER / DIZZY GILLESPIE

Channel 5 TV, NYC, 24/2/1952

14. HOT HOUSE 4’42

JERRY JEROME ALL STARS

Loew’s Theatre, Brooklyn, 25/3/1952

15. COOL BLUES 4’21

16. ORNITHOLOGY 8’21

Proposer une véritable « intégrale » des enregistrements laissés par Charlie Parker est actuellement impossible et le restera longtemps. Peu de musiciens ont suscité de leur vivant autant de passion. Plus d’un demi-siècle après sa disparition, des inédits sont publiés et d’autres – dûment répertoriés – le seront encore. Bon nombre d’entre eux ne contiennent que les solos de Bird car ils furent enregistrés à des fins privées par des musiciens désireux de disséquer son style. Sur le seul plan du son, ils se situent en majorité à la limite de l’audible voire du supportable. Faut-il rappeler, qu’à l’époque, leurs auteurs employaient des enregistreurs portables sur disque, des magnétophones à fil, à bande (acétate ou papier) et autres machines devenues obsolètes, engendrant des matériaux sonores fragiles ?

Aucun solo joué par Charlie Parker n’est certes négligeable, toutefois en réunissant chronologiquement la quasi-intégralité de ce qu’il grava en studio et de ce qui fut diffusé à l’époque sur les ondes, il est possible d’offrir un panorama exhaustif de l’évolution stylistique de l’un des plus grands génies du jazz ; cela dans des conditions d’écoute acceptables.

Toutefois lorsque la nécessité s’en fait sentir stylistiquement parlant, la présence ponctuelle d’enregistrements privés peut s’avérer indispensable. Au mépris de la qualité sonore.

L’intégrale CHARLIE PARKER

STUDIO & RADIO VOL. 10

“BACK HOME BLUES” 1951-1952

En 1951, au mois de mars, Charlie Parker et Dizzy Gillespie se livrèrent à une partie de chaises musicales sur la scène du Birdland. Le 15, Dizzy entamait un séjour d’une semaine à la tête d’un septette comprenant John Coltrane qui, le dernier jour, se verra signifier son congé tellement son addiction à la drogue rendait son comportement imprévisible. Le 22, Charlie Parker prenait le relais pour une semaine à la tête de son orchestre à cordes et, le 29 rejoignait Gillespie de retour… à temps pour participer, deux jours plus tard, à l’une des retransmissions radiophoniques tardives du samedi effectuées depuis le Birdland. Pour l’occasion, Bird et Diz s’étaient entourés de Bud Powell, Tommy Potter et Roy Haynes. « Je ne sais pas trop qui tient le haut de l’affiche ce soir, voici donc… Dizzy Gillespie - Charlie Parker, Charlie Parker - Dizzy Gillespie. » L’annonce complète de Symphony Sid trahissait un certain embarras en laissant supposer qu’une rivalité persistait dès qu’il était question de préséance…

Au programme, une poignée de classiques bop. Sur Anthropology Parker enchaîne des citations – Tenderly, High Society, Temptation – qui ne laissent rien ignorer de l’intérêt qu’il porte à une spectatrice. « La musique, c’est votre propre expérience, vos propres pensées, votre propre sagesse. Si vous ne la vivez pas, elle ne sortira pas de votre instrument. On vous enseigne qu’il y a une frontière à la musique mais il n’y a pas de frontière en art (1). »

Au cours de A Night in Tunisia, si Diz et Bird renouent avec leurs habitudes, le solo le plus remarquable est dû à Bud Powell qui, sur ‘Round Midnight, avait déjà concocté derrière Parker un accompagnement, certes remarquable, qui en aurait désarçonné plus d’un.

Au cours d’une seconde retransmission radiophonique, Billy Taylor remplaça Bud. Ces versions de Hot House, Embraceable You et Ornithology étaient sans doute liées à l’interview que Parker avait accordée à Leonard Feather depuis le Birdland. Ensemble, ils avaient évoqué, entre autres, un article paru dans Ebony Magazine où Cab Calloway accusait les musiciens asujettis aux stupéfiants de conduire le monde de la musique à la ruine. Le tout illustré par une photo de Fats Navarro à la fin de sa vie.

S’avouant lui-même choqué, Leonard Feather demanda l’opinion de Parker. En insistant une fois de plus sur le fait que la drogue n’aidait pas à jouer mieux, Bird répondit : « C’est pauvrement écrit, pauvrement exprimé, pauvrement pensé, en un mot, c’est pauvre ».

Chan Parker : « Avant la naissance de Pree, on prit un grand appartement à l’angle de l’Avenue B et de la 10ème Rue. Pour la première fois, il avait une vie de famille. Il jouait à la perfection son rôle de père et d’époux. Il adorait Kim et prenait au sérieux ses responsabilités. Notre appartement se situait dans le quartier ukrainien du Lower East Side, plus tard connu sous le nom d’East Village. C’était pauvre, peuplé de juifs hassidiques portant les papillotes rituelles, de romanis d’origine hongroise, de russes, tout un brouet de réfugiés […] La musique de Bird en ces années 1951 à 1953 exprime une certaine joie de vivre qui reflète probablement cette phase de stabilité familiale (2). »

Invité par Parker, Al Cohn parlera de ce changement : « C’était ravissant chez eux. Au bout d’un certain temps, il dit à Chan que nous sortions boire un verre ou deux. C’était un quartier plein d’Ukrainiens et nous sommes allés dans trois ou quatre bistrots. Tous les Ukrainiens, des ouvriers, le connaissaient en tant que Charlie. Je ne pense pas qu’ils aient su qu’il était musicien mais, à l’évidence, ils l’aimaient et étaient heureux de le voir. Cette fois-là, j’ai vu une facette différente de sa personnalité : un type de la classe moyenne avec des valeurs de la classe moyenne (3). » Ce qui ne diminuait en rien sa curiosité musicale comme en témoigne sa suggestion au batteur Ed Shaughnessy : « Eddy, il faut absolument que tu viennes avec moi dans ce restaurant roumain. Ils ont ce formidable groupe folklorique avec des instruments à cordes anciens et des percussions, et tu veux que je te dise, ils swinguent plus que nous ! (4). »

Le Christy’s Restaurant, sis à Framingham dans la banlieue de Boston, était réputé pour ses jam sessions. Le 12 avril, Bird y fut conduit par le batteur Joe McDonald en compagnie de Nat Pierce et de Jack Lawlor. Dans cet établissement tenu par un ancien policeman amateur de jazz, Eddie Curran, Parker retrouva le trompettiste Howard McGhee : « L’endroit donnait sur un lac. Bird jouait de la façon la plus détendue possible dans une petite pièce alors que le reste de l’orchestre était à côté (5). » Maggie ne figure pas sur ce qui a été conservé de la soirée, à la différence de Wardell Gray, venu depuis le Hi Hat de Boston où se produisait l’orchestre de Count Basie auquel il appartenait alors. Il partagera Scrapple from the Apple avec Parker, Bill Wellington les rejoignant sur Lullaby of Rhythm. De bonne humeur, Bird esquissera en sus un blues.

Fin avril, à la tête de son orchestre à cordes, Parker entreprit une tournée qu’il prolongea avec un quintette dont Benny Harris était le trompettiste. À Philadelphie, ce dernier fit défection pour le plus grand bonheur de Clifford Brown qui put jouer une semaine entière en compagnie de Bird. À son retour, ce dernier préviendra Blakey en partance pour Philly : « N’emmène pas de trompettiste. Tu n’en éprouveras pas le besoin quand tu auras entendu Clifford Brown (6). » Le 20 juin, invité de l’orchestre de Machito, Charlie Parker apparut au Birdland. Il faudra attendre quinze mois avant de le voir à nouveau figurer à l’affiche.

Jusque-là, chance ou prudence, Charlie Parker n’avait pas été pris la main dans le sac mais ce qui devait arriver, arriva. Arrêté, un juge le condamna à trois mois de prison avec sursis, prétexte idéal pour que lui soit retirée sa « New York City Cabaret Identification Card ». Le seul document, obligatoire depuis la Prohibition, qui autorise un musicien à se produire dans les lieux de la Grosse Pomme où l’alcool était en vente ; c’est-à-dire dans les seuls endroits où il avait une chance de travailler (7).

Au même moment paraissait dans le numéro de Down Beat du 29 juin, la réponse de Bird à la question posée dans la rubrique « My Best On Wax » (Mes meilleurs enregistrements) : « Je suis navré mais mon meilleur enregistrement est encore à venir. Lorsque j’écoute mes disques, je trouve que sur chacun, des améliorations auraient pu être apportées. Il n’y en a pas un seul qui me satisfasse complètement. Par contre, si vous voulez savoir quel est mon plus mauvais disque, c’est facile, je désignerai Lover Man, une horreur qui n’aurait jamais dûe être publiée, enregistrée la veille du jour où j’ai eu une dépression nerveuse. Et puis non, je choisirais Be Bop gravé à la même séance ou The Gypsy. Ils sont épouvantables. »

On peut s’étonner qu’aucune de ses interprétations gravées en compagnie de son orchestre à cordes ne trouve grâce à ses yeux. Toutefois, il n’est pas impossible que, ainsi qu’il est d’usage dans la presse avec ce genre d’écho bouche-trou, ce texte soit resté un certain temps au marbre, perdant ainsi de son actualité. En tout état de cause, il montrait que Parker avait la rancune tenace.

Suite de la sanction décrétée par la State Liquor Authority, Parker ne pouvait se produire qu’en dehors de New York. À Kansas City, sa venue coïncida avec celle de la formation dirigée par Woody Herman, l’un de ses grands admirateurs : « Toutes ces années, Charlie Parker dépassait tout le monde de la tête et des épaules et tous ceux qui ont essayé de l’imiter sont à mes yeux dans l’erreur (8). »

À New York, au Basin Street et au Music-in-the-Round, Bird était venu se mêler à l’orchestre pour le plaisir. Cette fois, il le rejoindra durant un concert donné à la Municipal Arena. Dick Hafer : « Bird était en grande forme ce soir-là. Il était venu voir sa mère et pour l’occasion, il restait sobre car elle n’aurait pas permis qu’il en soit autrement. Nous avons joué dans un grand auditorium. Je crois que c’était une salle pour « conventions ». C’était amusant, Bird savait ce qu’il voulait jouer. Il était étonnant car il semblait connaître l’intégralité du répertoire de Woody (9). »

Dans les arrangements, Bird prit la place de Woody Herman. More Moon, Leo the Lion, interprété à deux reprises, The Goof and I, Lemon Drop, Cuban Holiday, tous les « classiques » hermaniens défilèrent. Même Four Brothers où Parker, après un bref moment de flottement, reprit successivement les breaks dévolus aux Brothers. Dick Hafer se souvint que la soirée se termina par un bœuf mémorable dans un club de la ville.

La suppression de sa carte n’empêchait pas Bird d’enregistrer à New York. Le 8 août, en compagnie de Red Rodney, John Lewis, Ray Brown et Kenny Clarke, il mit en boîte Si Si, Blues for Alice, Swedish Schnapps et Back Home Blues. Red Rodney : « Il était vraiment en forme ce jour-là, très heureux d’enregistrer avec des gens qui, à part moi, n’étaient pas ses partenaires réguliers. Il aimait ça. C’était très différent de la rythmique que nous avions. Je ne sais pas si c’était mieux mais c’était un défi […] Quand nous sommes arrivés, tout était écrit, je soupçonne John Lewis de l’avoir fait, même si c’est Bird qui a tout composé (10). »

Norman Granz demanda ensuite à Bird d’enregistrer Lover Man. Sans grand enthousiasme, il accepta. Son contrechant derrière Red Rodney permet à cette reprise d’échapper à l’insignifiance mais, à l’évidence, le cœur n’y était pas. Cette séance marqua la seule rencontre officielle entre Parker et Kenny Clarke. Avant (ou juste après), ils se rendirent dans l’atelier de Lennie Tristano. En la compagnie de ce dernier, Bird interpréta deux standards, l’occasion pour Kenny d’utiliser ses balais sur… des annuaires téléphoniques.

Six mois vont s’écouler avant que Parker ne franchisse à nouveau les portes d’un studio, en compagnie cette fois d’un grand orchestre. Il en avait choisi le répertoire, affichant une vraie passion pour Autumn in New York (ce sera sa troisième meilleure vente en « single »). Granz avait de nouveau fait appel aux services de Joe Lippman : « J’étais une sorte d’arrangeur commercial mais je pense que Norman voulait cela plutôt que du jazz pur. Sinon il aurait fait appel à un arrangeur de jazz. Je veux dire à un spécialiste (11). » Indifférent tant à la lourdeur de l’accompagnement dans Lover qu’à l’introduction grandiloquente de Temptation, dans pareil contexte Parker se comporta à la façon d’un crooner. Un choix judicieux.

Dans la foulée fut terminé l’album « South of the Border ». Renvoyé à plusieurs reprises, réengagé autant de fois, Benny Harris en petite forme y participait. Un seul joueur de congas, Luis Miranda, assistait cette fois Max Roach. Parker prit un tel plaisir à interpréter Mama Inez, à s’épancher sur Estrellita ou à cajoler Begin the Beguine que Roy Haynes le soupçonnera toujours d’avoir été l’instigateur de ces séances à tout le moins surprenantes par la thématique choisie.

Pas plus que les studios, les plateaux de TV n’étaient interdits à Bird. Le pianiste Dick Hyman se produisait dans « Date on Broadway », un show télévisé diffusé à une heure tardive. Tenant le producteur pour « progressiste », il lui avait proposé d’inviter Leonard Feather qui remettrait leurs Down Beat Awards à Charlie Parker et Dizzy Gillespie qui joueraient ensuite. La suggestion ayant été acceptée, le batteur Charlie Smith et le bassiste Sandy Block furent engagés.

Dick Hyman : « Gillespie et Parker étaient heureux de se trouver là. Tout le monde était bien disposé, sans la moindre trace de racisme, mais avec, sans doute, une certaine gêne tenant essentiellement à la découverte de ce nouveau média qu’était la télévision et aux interrogations vis-à-vis du travail des cameras (13). »

Bird et Diz interprétèrent Hot House au cours d’une courte scène reprise dans tous les documentaires consacrés à Charlie Parker. Elle constitue en effet la seule et unique séquence filmée où l’on puisse voir et entendre Bird jouer. Dans ce qui reste du second film de Gjon Mili produit par Norman Granz (voir volume 9), le son a été postsynchronisé. Grâce soit donc rendue au DuMont Television Network et à Dick Hyman.

Le lendemain, lorsqu’il fallut compléter la séance en grand orchestre, tout ne se déroula pas sous les meilleurs auspices. Danny Bank : « Bird est arrivé le premier. Il devait être neuf heures du matin. J’étais le deuxième. Il était à son pupitre prêt à enregistrer. Le fait qu’il soit à l’heure était fréquent dans beaucoup de cas. Il arrivait avec ses accords de passage sur des petites fiches. Il posait les cartons sur le pupitre et faisait toute la séance avec ça (12). » Contestant le fait que les chorus de trompette soient attribués à Bernie Privin, un musicien blanc, Parker exigea à cor et à cris la venue d’Idrees Sulieman. Sans obtenir gain de cause. Il imposa ensuite à Body and Soul un tempo si rapide qu’Oscar Peterson fut obligé de prendre impromptu un solo pour que le morceau atteigne une durée convenable.

Le soir même, au Loew’s Valencia Theater de Jamaica dans la banlieue de New York, Parker participa à un concert, calqué sur le Jazz at The Philharmonic, organisé par Jerry Jerome. Sur Cool Blues, il aurait été accompagné par Teddy Wilson ce qui, à l’écoute, n’est pas évident. Le pianiste pourrait en fait être Dick Cary, présent sur Ornithology où interviennent Bill Harris et Buddy de Franco.

Dans son édition du 7 mai, Down Beat publia une chronique à tout le moins mitigée de Au Privave et de Star Eyes. Parker en prit-il connaissance ? À la fin du mois, il gagnait la Californie, engagé au Tiffany Club de Los Angeles…

Alain Tercinet

© 2015 Frémeaux & Associés

(1) Nat Shapiro & Nat Hentoff, « Hear Me Talkin’ To Ya », Rinehart and C°, inc, 1955.

(2) Chan Parker, « Ma vie en mi bémol », trad. Liliane Rovère, Plon, 1993.

(3) (4) Gary Giddins, « Celebrating Bird – Le triomphe de Charlie Parker », trad. Alain-Pierre Guilhon, Denoël,1988.

(5) Lawrence O. Koch, « Yardbird Suite », Northeastern University Press, 1999.

(6) Nick Catalano, « Clifford Brown », Oxford University Press, 2000.

(7) Cette disposition fut définitivement abrogée en 1967 par le président Kennedy suite à un scandale survenu sept ans plus tôt : Lord Buckley (Richard Myrtle Buckley), auteur de monologues satiriques et figure de l’underground new-yorkais, était mort d’une crise cardiaque, à cinquante-quatre ans, après avoir appris le retrait de sa carte.

(8) Gene Lees, « Leader of the Band – The Life of Woody Herman », Oxford University Press, 1995.

(9) William D. Clancy & Audree Coke Kenton, « Woody

Herman, Chronicles of the Herds », Schirmer Books, 1995.

(10) (11) (12) Livret du coffret « The Complete Charlie Parker on Verve ».

(13) Dick Hyman interviewé par Mark Myers, 5/1/2010, JazzWax, internet.

NOTES DISCOGRAPHIQUES

INTERVIEW LEONARD FEATHER

La date précise en est incertaine. Une source donne février 1951 ce qui n’est guère vraisemblable, Parker étant absent de New-York à cette période.

CHARLIE PARKER WITH WOODY HERMAN AND HIS ORCHESTRA

More Moon (intitulé How High the Moon sur certaines rééditions) marqua l’arrivée de Parker sur scène. Dans le brouhaha précédant le début de l’interprétation, on devine Woody Herman saluant l’arrivée de Bird. Ici ce More Moon a été déplacé en fin de session en raison d’une qualité sonore très inférieure. Ce concert avait été publié à l’origine sur un LP sans numéro, à tirage limité, sous pochette blanche portant comme seule indication un nom de label, Alamac. La source en était la collection de Boris Rose qui, plus tard, édita lui-même cette bande sur une autre marque fantaisiste (Mainman – La Mere d’Oiseau) sous le titre « Bird Flies with The Herd ». The Goof and I y était faussement intitulé Sonny Speaks. Le nom Alamac sera repris des années plus tard pour exploiter sur LP une partie du fond Boris Rose.

SÉANCES DU 22/1/1952 ET DU 25/3/1952.

Tous les solos de trombone sont interprétés par Bill Harris, tous les solos de trompette sont dus à Bernie Privin, à l’exception de celui de Lover pris par Al Porcino.

THE COMPLETE CHARLIE PARKER

STUDIO & RADIO VOLUME 10

“BACK HOME BLUES” 1951-1952

A genuine “complete” set of the recordings left by Charlie Parker is impossible today and will remain so for a long time to come. Few musicians aroused so much passion during their own lifetimes and today, more than half a century after his disappearance, previously-unreleased music is published, and other titles – duly listed – will also come to light. A good many contain only solos by Bird, as they were recorded – privately – by musicians wanting to dissect his style. Regarding their sound-quality, most of them are at the limit: barely audible, sometimes almost intolerable, but in fact understandable: those who captured these sounds used portable recorders that wrote direct-to-disc, or wire-recorders, “tapes” (acetate or paper) and other machines now obsolete. Obviously they all produced sound-carriers that were fragile.

Of course, no solo ever played by Charlie Parker is to be disregarded. But a chronological compilation of almost everything he recorded – either inside a studio or on radio for broadcast purposes – does make it possible to provide an exhaustive panorama of the evolution of his style (Parker was, after all, one of the greatest geniuses in jazz), and to do so under acceptable listening-conditions. However, since we refer to style, the occasional presence here of some private recordings is indispensable, whatever the quality of the sound.

In March 1951, Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie played musical chairs on the stage at the Birdland club: on the 15th Dizzy began a week-long gig fronting a septet that included John Coltrane (who was sacked on his last day because his drug addiction was making his behaviour unpredictable); on the 22nd Charlie Parker took over for a week with his own string orchestra; and on the 29th Bird was joined by Gillespie, who’d come back… just in time to take part two days later in one of those late radio broadcasts which went out from Birdland every Saturday. Bird and Diz had enlisted Bud Powell, Tommy Potter and Roy Haynes for the occasion. “I don’t really know who’s top of the bill tonight, so here’s… Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker; Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie.” On the whole, Symphony Sid’s announcement betrayed a certain embarrassment; he supposed there might still be some rivalry between them over questions of precedence…

The programme featured a fistful of bop classics. On Anthropology Parker goes through a series of quotes – Tenderly, High Society, Temptation – which conceal none of his interest in a female member of the audience. “Music is your own experience, your thoughts, your wisdom. If you don’t live it, it won’t come out of your horn. They teach you there’s a boundary line in music. But, man, there’s no boundary line to art.”1 During A Night in Tunisia, while Diz and Bird go back to their old habits, the most remarkable solo comes from Bud Powell who, on ‘Round Midnight, had already concocted a remarkable piece of piano accompaniment that would have thrown more than one soloist. In a second radio broadcast Billy Taylor replaces Bud. These versions of Hot House, Embraceable You and Ornithology no doubt relate to the interview that Parker had given to Leonard Feather while at Birdland. Among other things they discussed was a piece in Ebony Magazine where Cab Calloway had said that narcotics were ruining the music business… The piece was illustrated by a photo of Fats Navarro towards the end of his life. Feather wanted Parker’s opinion of Calloway’s statement that “a large number of musicians” were using narcotics, admitting he was also shocked. While emphasizing once again that drugs didn’t help anyone play better, Parker replied, “I’d rather say that it was poorly written, poorly expressed, and poorly meant. It was just poor.”

Chan Parker: “There is a happy maturity in the music of Bird during those years from 1951 to 1953. He had entered this phase of domestic stability and his children brought much joy to him […] Before Pree was born, we moved to a large apartment on Avenue B and 10th Street. For the first time of his life Bird had a stable family life. He played his role of husband and father to the hilt. He adored Kim and took his paternal duties seriously. Our apartment was in the Ukrainian section of Lower East Side. It later became known as the East Village. It was an area full of poverty, peopled by Hassidic Jews with sidelocks and by gypsies, and was a melting pot for refugees.”2

Al Cohn talked about the change after being invited to the Parkers’ home: “They had a very nice place. After a while, he told Chan we were going out to have a few drinks. It was a Ukrainian neighbourhood and we went to three or four different bars. All the Ukrainians, working-class guys, knew him as Charlie. I don’t think they knew he was a musician, but it was obvious they liked him and were glad to see him. I saw a different side of him: he was like a middle-class guy with middle-class values.”3 None of this life made Parker any less curious about music, as witnessed by his suggestion to drummer Ed Shaughnessy: “Eddie, you’ve got to come up to this Romanian restaurant with me. They have this fantastic folk group with some authentic stringed instruments and percussion, and you know something, they swing more than we do!”4

Christy’s Restaurant in the Boston suburb of Framingham was renowned for its jam sessions, and drummer Joe McDonald took Bird there on April 12th with Nat Pierce and Jack Lawlor. Christy’s was run by Eddie Curran, an ex-cop jazz fan, and there Parker found trumpeter Howard McGhee: “It overlooked a lake, and Bird played his most relaxed horn in a separate little wing while the rest of the band was in the next room.”5 Maggie doesn’t appear on what was kept of the recordings made that night, unlike Wardell Gray, who’d come over from the Hi Hat in Boston where he was playing with Count Basie’s orchestra. With Parker, Wardell would share Scrapple from the Apple, with Bill Wellington joining them on Lullaby of Rhythm. Bird, in a good mood, sketches out an additional blues.

At the end of April Parker took his string orchestra on tour, and then extended the tour with a quintet which included Benny Harris on trumpet; in Philadelphia the latter deserted, delighting Clifford Brown who could now play for a whole week in Bird’s company. When Bird returned home, he said to Art Blakey (on his way to Philly himself), “Don’t take a trumpet player with you. You won’t need one after you hear Clifford Brown.”6 On June 6th Parker appeared at Birdland as a guest of Machito and his orchestra, but fifteen months would go by before anyone saw Parker’s name on a poster again.

Until then, either through luck or by exercising prudence, Bird hadn’t been caught red-handed, but now the inevitable finally happened. He was arrested and given a three-months’ suspended sentence, an ideal motive for the authorities to confiscate his “New York City Cabaret Identification Card.”7 This “cabaret card”, mandatory since Prohibition, was the only document that authorized a musician to work at venues in the Big Apple where liquor was sold, i.e. the only places where they could find work anyway. At the same time, the June 29th issue of Down Beat carried Bird’s contribution to the section called “My Best On Wax”: “I’m sorry, but my best on wax has yet to be made. When I listen to my records I always find that improvements could be made on each one. There’s never been one that completely satisfied me. If you want to know my worst on wax, though, that’s easy. I’d take ‘Lover Man’, a horrible thing that should never have been released – it was made the day before I had a nervous breakdown. No, I think I’d choose ‘Be-Bop’, made at the same session, or ‘The Gypsy’. They were all awful.” You might find it amazing that none of the records he made with a string orchestra found favour with him. However, it’s not impossible (given the habits of the press when it comes to this sort of stop-gap news item) that the article had been at the printers’ for a while already and was no longer topical. Either way, Parker’s comments show he could hold a grudge for a long time.

The ban decreed by the State Liquor Authority meant that Parker could now play only outside New York. He went to Kansas City, and his arrival coincided with that of the band led by Woody Herman, one of Bird’s great admirers: “In recent years Charlie Parker was head and shoulders above anyone else, and all the ones that tried to emulate him, to me, are just kind of lost people.”8 In New York, at the Basin Street Club and at the Music-in-the-Round, Bird had joined in with the Herman band for fun. This time it would be for a concert at the Municipal Arena. According to Dick Hafer, “Bird was in great shape that night. He was visiting his mother. He always stayed sober when he was around her because she wouldn’t allow it. We played in a huge auditorium. I think it was a convention centre. It’s funny; Bird knew what he wanted to play. He was so amazing, it seemed like he knew Woody’s whole book. He’d call tunes that he wanted to play.”9 Bird took Woody Herman’s place in the arrangements, and all the Herman band classics filed past: More Moon, Leo the Lion (played twice), The Goof and I, Lemon Drop, Cuban Holiday... There was even a Four Brothers where Parker, after an instant’s hesitation, took each one of the Brothers’ breaks in succession. Dick Hafer remembered that the night came to an end with a memorable jam in a city club.

Confiscation of Bird’s cabaret card didn’t stop him from recording (as opposed to appearing) in New York, however. On August 8th he taped Si Si, Blues for Alice, Swedish Schnapps and Back Home Blues in the company of Red Rodney, John Lewis, Ray Brown and Kenny Clarke. “I remember he was in really good form that day,” said Red Rodney. “He was very happy about recording with people he regularly didn’t play with. It wasn’t his regular band except for me; he enjoyed that, you know, it was a little different. It was much different than the rhythm section we had, I don’t know if it was better but it was challenging […] When I got there, these things were written out, so I suspect that John Lewis had written them even though Bird was the writer of the tunes.”10 Next, Norman Granz asked Parker to record Lover Man. Bird agreed, but without any enthusiasm. The counterpoint he plays behind Red Rodney allows this version of the tune to avoid being classified as meaningless, but obviously Bird’s heart isn’t in it anymore. This session marked the only official pairing of Parker with Kenny Clarke. Beforehand (or just afterwards) they went over to Lennie Tristano’s workshop where, in the company of the latter, Bird played two standards giving Kenny the opportunity to display his brushwork… on two phonebooks.

Six months would go by before Parker went into a studio again, this time accompanied by a large orchestra. Parker chose the repertoire, displaying his genuine passion for Autumn in New York (the record, incidentally, would be his third-biggest selling “single”). Granz had once again called on Joe Lippman’s services: “I was like a commercial arranger,” said Joe, “but I think Norman wanted a little commercialism in the arrangements more than the downright jazz. Otherwise, he probably would have gone with a jazz arranger. I mean a guy who specializes in jazz.”11 Equally indifferent to both the heaviness of the Lover accompaniment and also the grandiloquence of the introduction to Temptation, in this context Parker behaved like a crooner. It was a wise choice.

They finished the album “South of the Border” while they were at it. Fired on several occasions (and rehired just as often), Benny Harris took part in that one although he was in poor shape. This time, a single conga-player, Luis Miranda, was present to assist Max Roach. Parker seems to derive so much pleasure from playing Mama Inez, pouring out his feelings on Estrellita, or cajoling the song Begin the Beguine, that Roy Haynes always thought Bird was the instigator of these sessions; at the very least they were surprising, given the themes that were chosen.

Television wasn’t off-limits to Bird either, no more than the studios were. Pianist Dick Hyman was appearing on “Date on Broadway”, a light-night TV show, and, in the opinion that the show’s producer was “progressive”, Dick suggested that he might invite Leonard Feather onto the show, to present Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie with their Down Beat Awards and then have them play afterwards. His proposal was accepted; drummer Charlie Smith was hired, as was bass player Sandy Block. “Both Gillespie and Parker were happy to be there,” said Hyman. “Everyone was graceful. There was no coded racism. Awkwardness, perhaps, but that had more to do with the new medium of television and how to work with the cameras.”12 Bird and Diz played Hot House in the course of a short sequence that has been used in all film-documentaries devoted to Parker since, the reason being that it is indeed the only piece of film where people can actually see and hear Bird play (what remains of the second film directed by Gjon Mili, and produced by Granz, c.f. Vol. 9, has post-synchronous sound.) So, thank you to DuMont Television Network and Dick Hyman.

The next day, when the time came for the full orchestra to complete the session, not everything began as auspiciously. According to Danny Bank, “Bird came in first. It was about nine o’clock in the morning. And I came in about second. Bird was sitting at his stand ready to go. It (being on time) seems that that’s the way he did on a lot of dates. He brought the changes in on little index cards. Put the changes on the stand and did the whole date from the index cards.”13 Contesting the fact that the trumpet choruses had been attributed to Bernie Privin, a white musician, Parker clamoured for Idrees Sulieman to be summoned. He went unheeded. Next, he set such a rapid tempo for Body and Soul that Oscar Peterson was obliged to take an impromptu solo in order that the piece might reach a suitable length… The same evening, at the Loew’s Valencia Theater in Jamaica, N.Y., Parker took part in a concert that was cloned from Jazz at The Philharmonic; the organizer was Jerry Jerome. On Cool Blues his accompanist was supposedly Teddy Wilson, but when you listen to the piano, maybe it isn’t; this pianist could actually be Dick Cary, who plays on Ornithology also, a tune with contributions from both Bill Harris and Buddy DeFranco. In its May 7th issue, Down Beat published a review of Au Privave and Star Eyes in which the paper’s feelings were mixed at the least. Did Parker see that review? At the end of the month, he went to California to play a booking at the Tiffany Club in Los Angeles…

Adapted by Martin Davies

from the French text of Alain Tercinet

© 2015 Frémeaux & Associés

(1) Nat Shapiro & Nat Hentoff, “Hear Me Talkin’ To Ya”, Rinehart and C°, Inc. 1955.

(2) Chan Parker, “My Life in E-Flat”, University of South Carolina Press, 1999.

(3), (4) Gary Giddins, “Celebrating Bird – The Triumph of Charlie Parker”, Univ. of Minnesota Press, revised ed., 2013.

(5) Lawrence O. Koch, “Yardbird Suite”, Northeastern University Press, 1999.

(6) Nick Catalano, “Clifford Brown”, Oxford University Press, 2000.

(7) Usage of cabaret cards was definitively repealed in 1967 by President Kennedy after a scandal that had arisen seven years earlier: New York underground-figure Lord Buckley (Richard Myrtle Buckley), known for his satirical monologues, died of a heart-attack at the age of 54 after learning his card had been withdrawn.

(8) Gene Lees, “Leader of the Band – The Life of Woody Herman”, Oxford University Press, 1995.

(9) William D. Clancy & Audree Coke Kenton, “Woody Herman, Chronicles of the Herds”, Schirmer Books, 1995.

(10), (11), (12) Boxed-set booklet, “The Complete Charlie Parker on Verve”.

(13) Dick Hyman interviewed by Mark Myers, 5/1/2010, JazzWax, Internet.

DISCOGRAPHICAL NOTES

LEONARD FEATHER INTERVIEW

The exact date is uncertain. One source gives it as February 1951, which hardly seems likely: Parker wasn’t in New York during that period.

CHARLIE PARKER WITH WOODY HERMAN AND HIS ORCHESTRA

More Moon (entitled How High the Moon in some reissues) marks Parker’s arrival onstage. In the hubbub preceding the beginning of the performance, you can make out Woody Herman greeting Bird. Here, this More Moon has been moved to the end of the session due to its greatly inferior sound quality. This concert was originally released on an unnumbered, limited edition LP with a blank label carrying only a mention of the label-name Alamac. The source of this recording was the collection of Boris Rose, who later published this tape himself on another fantasy-name label (Mainman – La Mere d’Oiseau) under the title “Bird Flies with The Herd”. On it, The Goof and I carries the false title Sonny Speaks. The Alamac name would be picked up years later to exploit part of the Boris Rose collection on LP.

SESSIONS DATED 22/1/1952 AND 25/3/1952.

Bill Harris plays all the trombone solos, and all trumpet solos are by Bernie Privin except for Lover, where Al Porcino takes the solo.

CD1

CHARLIE PARKER ALL-STARS

Dizzy Gillespie (tp) ; Charlie Parker (as) ; Bud Powell (p) ; Tommy Potter (b) ; Roy Haynes (dm) ; Symphony Sid (mc).

WJZ Radio Broadcast, Birdland, NYC, 31/3/1951

1. BLUE ‘N’ BOOGIE (D. Gillespie, F. Paparelli) (Radio Transcription) 7’29

2. ANTHROPOLOGY (C. Parker, D. Gillespie) (Radio Transcription) 5’46

3. ‘ROUND MIDNIGHT (T. Monk, C. Williams, B. Hanighan) (Radio Transcription) 3’31

4. NIGHT IN TUNISIA/ JUMPIN’ WITH SYMPHONY SID (D. Gillespie, F. Paparelli/L. Young)

(Radio Transcription) 5’17

CHARLIE PARKER ALL-STARS

Dizzy Gillespie (tp) ; Charlie Parker (as) ; Billy Taylor (p) ; Tommy Potter (b) ; Roy Haynes (dm) ; Leonard Feather (mc).

Radio Broadcast, Birdland, NYC, spring 1951

5. HOT HOUSE (T. Dameron) (Radio Transcription) 4’23

6. EMBRACEABLE YOU (G. & I. Gershwin) (Radio Transcription) 3’42

7. HOW HIGH THE MOON(M. Lewis, N. Hamilton)/ ORNITHOLOGY (C. Parker, B. Harris)

(Radio Transcription) 5’20

CHARLIE PARKER

Charlie Parker (as) ; Bill Wellington* (ts), Wardell Gray (ts) ; Nat Pierce (p) ; Jack Lawlor (b) ; Joe McDonald (dm). Christy’s Restaurant, Framingham, Massachussets, 12/4/1951

8. SCRAPPLE FROM THE APPLE (C. Parker) (Charlie Parker PLP404) 15’16

9. LULLABY IN RHYTHM* (H. Sullivan, H. Ruskin) (Charlie Parker PLP404) 12’28

10. HAPPY BIRD BLUES (C. Parker) (inc.) (Charlie Parker PLP404) 2’52

CD2

CHARLIE PARKER WITH WOODY HERMAN AND HIS ORCHESTRA

Roy Caton, Don Fagerquist, Joseph Macombe, Doug Mettome (tp) ; Jerry Dorn, Urbie Green, Fred Lewis (tb) ; Woody Herman (cl, as, ldr, cond) ; Charlie Parker (as) ; Dick Hafer, Bill Perkins, Kenny Pinson (ts) ; Sam Staff (bs) ; Dave McKenna (p) ; Red Wooten (b) ; Sonny Igoe (dm). Municipal Arena, Kansas City, 22/7/1951

1. YOU GO TO MY HEAD (H. Gillespie, J. Fred Coots) (inc.) (Private Recording) 3’08

2. LEO THE LION I (T. Kahn) (Private Recording) 3’06

3. CUBAN HOLIDAY(R. Wooten) (Private Recording) 3’06

4. THE NEARNESS OF YOU (H. Carmichael, N. Washington) (Private Recording) 3’35

5. LEMON DROP (G. Wallington) (Private Recording) 3’44

6. THE GOOF AND I (A. Cohn) (Private Recording) 3’33

7. LAURA (D. Raskin, J. Mercer) (Private Recording) 2’56

8. FOUR BROTHERS (J. Giuffre) (Private Recording) 3’51

9. LEO THE LION II (T. Kahn) (Private Recording) 3’12

10. MORE MOON (S. Rogers) (inc.) (Private Recording) 3’18

CHARLIE PARKER QUINTET

Red Rodney (tp) ; Charlie Parker (as) ; John Lewis (p) ; Ray Brown (b) ; Kenny Clarke (dm). NYC, 8/8/1951

11. BLUES FOR ALICE (C. Parker) (Clef MGC646/mx. 609-4) 2’50

12. SI SI (C. Parker) (Mercury/Clef 11103/mx. 610-4) 2’42

13. SWEDISH SCHNAPPS (C. Parker) (Verve MGV 8010/mx. 611-3) 3’18

14. SWEDISH SCHNAPPS (C. Parker) (master) (Mercury/Clef 11103/mx. 611-4) 3’15

15. BACK HOME BLUES (C. Parker) (Verve MGV 8010/mx. 612-1) 2’39

16. BACK HOME BLUES (C. Parker) (master) (Mercury/Clef 11095/mx. 612-2) 2’51

17. LOVER MAN (R. Ramirez, J. Davis) (Mercury/Clef 11095/mx. 613-2) 3’28

CHARLIE PARKER / LENNIE TRISTANO

Charlie Parker (as) ; Lennie Tristano (p) ; Kenny Clarke (brushes). Lennie Tristano’s studio, NYC, august 1951

18. ALL OF ME (G. Marks, S. Simons) (Private Recording) 3’36

19. I CAN’T BELIEVE THAT YOU’RE IN LOVE (J. McHugh,C. Gaskill) (Private Recording) 4’23

CD3

CHARLIE PARKER BIG BAND

Charlie Parker (as) with Chris Griffin, Al Porcino, Bernie Privin (tp) ; Will Bradley, Bill Harris (tb) ; Toots Mondello, Murray Williams (as) ; Hank Ross, Art Drellinger (ts) ; Stan Webb (bs) ; unknown strings ; Verley Mills (harp) ; Lou Stein (p) ; Art Ryerson (g) ; Bob Haggart (b) ; Don Lamond (dm) ; Joe Lippman (arr, cond). NYC, 22/1/1952

1. TEMPTATION (N. H. Brown, A. Freed) (Mercury/Clef 11088/mx. 675-2) 3’32

2. LOVER ((R. Rodgers, L. Hartz) (Mercury/Clef 11089/mx. 676-3) 3’07

3. AUTUMN IN NEW YORK (V. Duke) (Mercury/Clef 11088/mx. 677-4) 3’29

4. STELLA BY STARLIGHT (V. Young, N. Washington) (Mercury/Clef 11089/mx. 678-4) 2’57

CHARLIE PARKER QUINTET

Benny Harris (tp except *) ; Charlie Parker (as) ; Walter Bishop (p) ; Teddy Kotick (b) ; Max Roach (dm) ; Luis Miranda (cga). NYC, 23/1/1952

5. MAMA INEZ (L. Wolfe Gilbert, E. Grenet) (Mercury Clef 11092/mx. 679-4) 2’54

6. LA CUCARACHA(Trad.) (Mercury Clef 11093/mx. 680-3) 2’44

7. ESTRELLITA (A. Venosa, V. Picone) (Mercury Clef 11094/mx. 681-5) 2’44

8. BEGIN THE BEGUINE * (C. Porter) (Mercury Clef 11094/mx. 682-3) 3’15

9. LA PALOMA (Trad.) (Mercury Clef 11091/mx. 683-1) 2’41

CHARLIE PARKER BIG BAND

Charlie Parker (as) with Jimmy Maxwell, Carl Poole, Al Porcino, Bernie Privin (tp) ; Lou McGarrity, Bill Harris, Bart Varsalona (tb) ; Harry Terrill, Murray Williams (as) ; Flip Phillips, Hank Ross, (ts) ; Danny Bank (bs) ; Oscar Peterson (p) ; Freddie Greene (g) ; Ray Brown (b) ; Don Lamond (dm) ; Joe Lippman (arr, cond). NYC, 25/3/1952

10. NIGHT AND DAY (C. Porter) (Mercury/Clef 11096/mx. 756-5) 2’50

11. ALMOST LIKE BEING IN LOVE (F. Lowe, A. Jay Lerner) (Mercury/Clef 11102/mx. 757-4) 2’35

12. I CAN’T GET STARTED (V. Duke, I. Gershwin) (Mercury/Clef 11096/mx. 758-1) 3’08

13. WHAT IS THIS THING CALLED LOVE ? (C. Porter) (Mercury/Clef 11102/mx. 759-5) 2’37

DOWN BEAT POLL WINNERS

Dizzy Gillespie (tp) ; Charlie Parker (as) ; Dick Hyman (p) ; Sandy Block (b) ; Charlie Smith (dm), Earl Wilson, Leonard Feather (mc). Dumont TV Network, Channel 5, NYC, 24/2/1952

14. HOT HOUSE (T. Dameron) (TV Broadcast) 4’42

JERRY JEROME ALL STARS

Charlie Parker (as) ; poss. Dick Cary (p) ; Eddie Safranski (b) ; Don Lamond (dm).

Radio Broadcast, Loew’s Kings Theatre, Brooklyn, 25/3/1952

15. COOL BLUES (C. Parker) (Radio Transcription) 4’21

Bill Harris (tb) ; Buddy deFranco (cl) ; Charlie Parker (as) ; Dick Cary (p) ; Eddie Safranski (b) ; Don Lamond (dm).

16. ORNITHOLOGY (C. Parker, B. Harris) (Radio Transcription) 8’21