- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

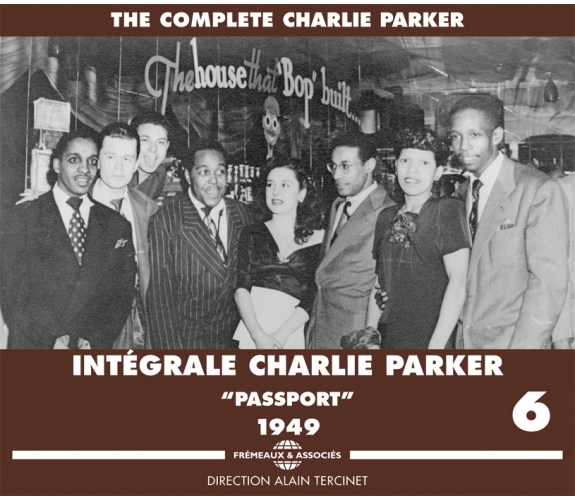

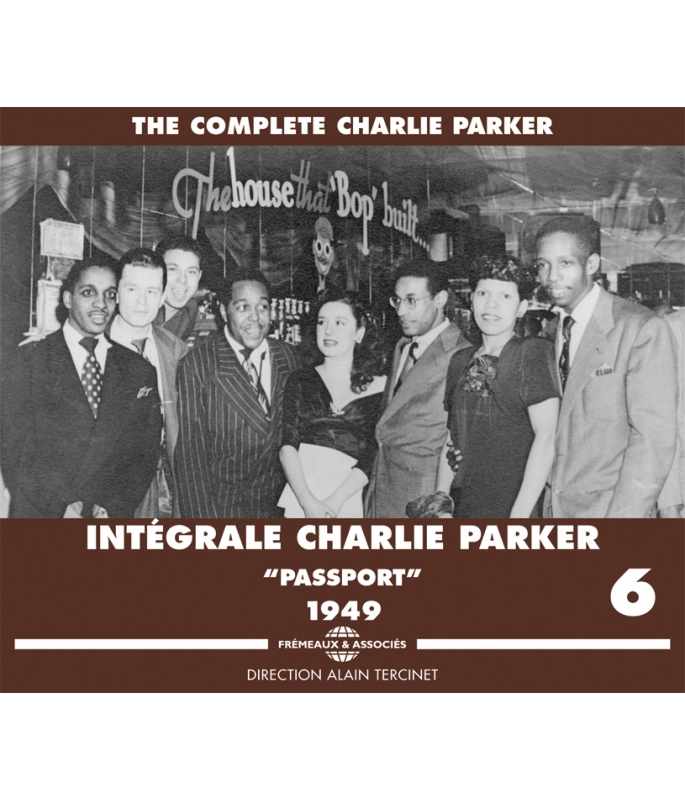

“PASSPORT” 1949

Ref.: FA1336

Artistic Direction : ALAIN TERCINET

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Total duration of the pack : 3 hours 36 minutes

Nbre. CD : 3

“PASSPORT” 1949

“PASSPORT” 1949

“You really have to be blind to all the evidence if you refuse to see that Parker’s calibre was at least as prodigious as that of the greatest musicians of earlier generations.” Boris VIAN

The aim of 'The Complete Charlie Parker', compiled for Frémeaux & Associés by Alain Tercinet, is to present (as far as possible) every studio-recording by Parker, together with titles featured in radio-broadcasts. Private recordings have been deliberately omitted from this selection to preserve a consistency of sound and aesthetic quality equal to the genius of this artist.

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Announcer ICharlie Parker All-Stars00:00:591949

-

2Scrapple From The AppleCharlie Parker All-Stars00:04:111949

-

3Announcer IICharlie Parker All-Stars00:00:261949

-

4Be-BopCharlie Parker All-Stars00:03:191949

-

5Announcer IIICharlie Parker All-Stars00:00:151949

-

6Hot HouseCharlie Parker All-Stars00:05:141949

-

7Announcer IVCharlie Parker All-Stars00:01:141949

-

8Oop Bop Sh BamCharlie Parker All-Stars00:04:561949

-

9Announcer VCharlie Parker All-Stars00:00:401949

-

10Scrapple From The Apple IICharlie Parker All-Stars00:04:331949

-

11Announcer VICharlie Parker All-Stars00:00:221949

-

12Salt PeanutsCharlie Parker All-Stars00:04:071949

-

13Announcer VIICharlie Parker All-Stars00:00:381949

-

14Announcer VIIICharlie Parker All-Stars00:00:571949

-

15Groovin HighCharlie Parker All-Stars00:03:441949

-

16Announcer IXCharlie Parker All-Stars00:00:231949

-

17Announcer XCharlie Parker All-Stars00:01:001949

-

18Scrapple From The Apple IIICharlie Parker All-Stars00:03:251949

-

19Announcer XICharlie Parker All-Stars00:00:231949

-

20BarbadosCharlie Parker All-Stars00:03:511949

-

21Announcer XIICharlie Parker All-Stars00:00:081949

-

22Salt Peanuts IICharlie Parker All-Stars00:03:341949

-

23Announcer XIIICharlie Parker All-Stars00:01:301949

-

24OkiedokeCharlie Parker with Machito And His Afro-Cuban Orchestra00:03:101949

-

25Leap HereJazz At The Philarmonic00:11:271949

-

26IndianaJazz At The Philarmonic00:11:211949

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Lover Come Back To MeJazz At The Philarmonic00:15:371949

-

2Announcer XIVCharlie Parker All-Stars00:00:071949

-

3Scrapple From The Apple IVCharlie Parker All-Stars00:04:331949

-

4Announcer XVCharlie Parker All-Stars00:00:161949

-

5Barbados IICharlie Parker All-Stars00:03:531949

-

6Announcer XVICharlie Parker All-Stars00:00:131949

-

7Be-Bop IICharlie Parker All-Stars00:03:191949

-

8Announcer XVIIICharlie Parker All-Stars00:00:051949

-

9Groovin' High IICharlie Parker All-Stars00:04:451949

-

10Announcer XVIIICharlie Parker All-Stars00:00:051949

-

11ConfirmationCharlie Parker All-Stars00:03:321949

-

12Announcer XIXCharlie Parker All-Stars00:00:121949

-

13Salt Peanuts IIICharlie Parker All-Stars00:03:451949

-

14Announcer XXCharlie Parker All-Stars00:00:091949

-

15Half NelsonCharlie Parker All-Stars00:03:321949

-

16Announcer XXICharlie Parker All-Stars00:00:151949

-

17A Night In TunisiaCharlie Parker All-Stars00:04:381949

-

18Announcer XXIICharlie Parker All-Stars00:00:241949

-

19Scrapple From The Apple VCharlie Parker All-Stars00:04:401949

-

20Announcer XXIIICharlie Parker All-Stars00:00:231949

-

21DeedleCharlie Parker All-Stars00:02:081949

-

22Announcer XXIVCharlie Parker All-Stars00:00:301949

-

23What ThisCharlie Parker All-Stars00:01:361949

-

24Announcer XXVCharlie Parker All-Stars00:01:251949

-

25CherylCharlie Parker All-Stars00:03:511949

-

26Announcer XXVICharlie Parker All-Stars00:00:271949

-

27AnthropologyCharlie Parker All-Stars00:05:091949

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Announcer XXVIICharlie Parker All-Stars00:01:101949

-

2Hurry HomeCharlie Parker All-Stars00:02:241949

-

3Deedle IICharlie Parker All-Stars00:02:021949

-

4Royal Roost BopCharlie Parker All-Stars00:02:121949

-

5Announcer XXVIIICharlie Parker All-Stars00:00:071949

-

6Cheryl IICharlie Parker All-Stars00:03:211949

-

7Announcer XXIXCharlie Parker All-Stars00:00:211949

-

8On A Slow Boat To ChinaCharlie Parker All-Stars00:03:381949

-

9Announcer XXXCharlie Parker All-Stars00:01:141949

-

10Chasin The BirdCharlie Parker All-Stars00:06:331949

-

11CardboardCharlie Parker and His Orchestra00:03:111949

-

12VisaCharlie Parker and His Orchestra00:03:021949

-

13SegmentCharlie Parker and His Orchestra00:03:221949

-

14Diverse SegmentCharlie Parker and His Orchestra00:03:191949

-

15Passport ICharlie Parker and His Orchestra00:02:571949

-

16Passport IICharlie Parker and His Orchestra00:03:031949

-

17Moose The MoocheCharlie Parker Quintet00:05:341949

-

18Hot House IICharlie Parker Quintet00:05:451949

-

19Allen S AlleyCharlie Parker Quintet00:04:291949

-

2052nd Street ThemeCharlie Parker Quintet00:04:561949

-

21Salt Peanuts IVCharlie Parker Quintet00:03:441949

-

22Blues FinalCharlie Parker Quintet00:05:001949

Intégrale Charlie Parker vol. 6 FA1336

THE COMPLETE Charlie Parker

INTÉGRALE Charlie Parker

“PASSPORT” 1949

Volume 6

DIRECTION ALAIN TERCINET

Proposer une véritable «?intégrale?» des enregistrements laissés par Charlie Parker est actuellement impossible et le restera longtemps. Peu de musiciens ont suscité de leur vivant autant de passion. Plus d’un demi-siècle après sa disparition, des inédits sont publiés et d’autres – dûment répertoriés – le seront encore. Bon nombre d’entre eux ne contiennent que les solos de Bird car ils furent enregistrés à des fins privées par des musiciens désireux de disséquer son style. Sur le seul plan du son, ils se situent en majorité à la limite de l’audible voire du supportable. Faut-il rappeler, qu’à l’époque, leurs auteurs employaient des enregistreurs portables sur disque, des magnétophones à fil, à bande (acétate ou papier) et autres machines devenues obsolètes, engendrant des matériaux sonores fragiles??

Aucun solo joué par Charlie Parker n’est certes négligeable, toutefois en réunissant chronologiquement la quasi-intégralité de ce qu’il grava en studio et de ce qui fut diffusé à l’époque sur les ondes, il est possible d’offrir un panorama exhaustif de l’évolution stylistique de l’un des plus grands génies du jazz?; cela dans des conditions d’écoute acceptables. Toutefois lorsque la nécessité s’en fait sentir stylistiquement parlant, la présence ponctuelle d’enregistrements privés peut s’avérer indispensable. Au mépris de la qualité sonore.

Durant quatre mois furent enregistrées les prestations assurées au Royal Roost par le quintette de Charlie Parker. Un véritable journal de bord rendant compte du comportement musical et personnel de Bird face au public d’un cabaret. Contrairement à ce qui se passait en studio, Parker ne lorgnait pas du côté de la postérité dans un tel environnement. Ses improvisations restent la plupart du temps très maîtrisées alors même qu’il y fasse souvent montre d’audace. On y retrouve bien sûr un certain nombre de ses tics, comme la réapparition obsessionnelle au fil des chorus - et pas seulement au Royal Roost - de certaines citations : Buttons and Bows – en français Ma guépière et mes longs jupons – , Country Gardens, un air folklorique anglais arrangé par Percy Granger, The Woody Woodpecker Song, quelquefois High Society, la Habanera de Carmen ou Jingle Bells.

Autre constat, la limitation du répertoire exploité alors que Bird connaissait un nombre impressionnant de thèmes, lui-même en ayant composé de remarquables, variations sur le blues ou extrapolations imaginées à partir des trente-deux mesures traditionnelles de standards. Au Royal Roost avaient ses faveurs Scrapple From The Apple (interprété à cinq reprises), Salt Peanuts (quatre fois), Be Bop et Groovin’ High (trois fois chaque) suivis d’Half Nelson, Cheryl et Barbados.

Parker pouvait également s’intéresser à un tube à la mode comme On a Slow Boat to China (trois versions) de Frank Loesser. Une scie dont l’omni-présence sur les ondes, dans les juke-boxes ou même sur les lèvres des passants, conduisait The Spirit, héros de la bande dessinée de Will Eisner, au bord de la dépression nerveuse. Quant à White Christmas, reproduit dans le précédent volume, il s’agissait purement et simplement d’une pièce de circonstance.

La plupart du temps, le déroulement des interprétations en club respecte le schéma suivi en studio. L’alto et la trompette exposent le thème - à l’unisson ou à l’octave - puis le réexposent en conclusion avant une éventuelle coda. Un façon de procéder susceptible d’être amendé par de brèves introductions de piano - plus rarement de basse - ou par un break initial de batterie. Sur disque, alto et trompette se partagent la majorité des solos, le pianiste n’ayant droit généralement qu’à un demi-chorus. En public, ses interventions, tout comme celles de la basse et de la batterie, peuvent s’étendre sans tomber pour autant dans la logorrhée : Parker estimait qu’un musicien devait être capable d’exposer ce qu’il avait à dire dans le cadre conventionnel des trois minutes imposé par le 78 t.

Les retransmissions depuis le Royal Roost reflètent fidèlement la vie d’une formation tributaire des humeurs de son chef. D’esprit badin le 15 janvier, Parker déploie sa panoplie de grand séducteur. Parfaitement absent le 29, après un exposé pour le moins douteux de Groovin’ High suivi d’un lambeau de phrase incohérent, il passe sans crier gare le témoin à un Kenny Dorham médusé. Il restera silencieux jusqu’à une réexposition difficultueuse du thème, suivie d’une coda tout autant erratique. À l’opposé, le Hot House du 15 janvier, Scrapple from the Apple joué la semaine suivante, Be Bop servi le 12 février, surpassent les meilleures versions de studio. Quant au Groovin’ High du 19 février l’improvisation qu’y sert Bird illustre le propos de Lennie Tristano : «?On peut comparer ses interprétations à un puzzle dans lequel les pièces peuvent être assemblées de centaines de manières différentes, découvrant chaque fois un dessin final qui, dans ses aspects généraux, diffère de tous les autres dessins possibles (1).?» Lee Konitz exprima une opinion voisine : «?Je ne pense pas à la musique de Parker comme à quelque chose d’improvisé sur l’instant. J’estime que c’était un homme tellement brillant qu’il était capable de pré-composer une musique parfaite et qui, assuré de savoir ce qu’il allait jouer, transportait toute sa formidable énergie dans la mise en place de sa musique et dans son expression (2).?» La semaine suivante, curieusement, Parker rate son fameux break de A Night in Tunisia. Brian Priestley fera remarquer que le manque de coordination qui se fait sentir à cette occasion ramène quelque peu à la fameuse «séance Lover Man».

En cabaret, Parker ne refusait jamais les invités. Dans le volume précédent, il avait célébré le réveillon en compagnie de l’ensemble dirigé par Charlie Ventura venu au grand complet rejoindre sa propre formation. Cette fois, à deux reprises, les vocalistes Dave Lambert et Buddy Stewart, monteront sur scène. Le premier connaîtra par la suite une certaine célébrité au sein du trio Lambert, Hendricks et Ross?; le second disparaîtra en 1950 dans un accident de la circulation.

À l’occasion des trois dernières transmissions radiophoniques, le quintette de Bird s’était métamorphosé en septette par l’adjonction de deux complices, le vibraphoniste Milt Jackson et le ténor Lucky Thompson, au mieux de sa forme sur Cheryl. Les soirées du Royal Roost se terminèrent le 12 mars 1949 par un Chasin’ the Bird de plus de six minutes?; un parfait point d’orgue.

Alors même qu’il se produisait sur Broadway, Parker poursuivait ses aventures musicales. Avant même la commercialisation des fruits de leur collaboration précédente, il retrouva Machito et son orchestre afro-cubain. Les réactions favorables entraînées par l’écoute des épreuves de Mango Mangue avaient, semble-t-il, incité Norman Granz à remettre rapidement le couvert. En baptisant Okiedoke une composition de Rene Hernandez et de Machito lui-même, Bird cultivait l’ambiguïté. Suivant la prononciation adoptée – O-ki-do-ki ou O-ki-dok (Parker utilisait les deux) -, le sens en était fort différent. La première signalait que tout allait bien, la seconde faisait allusion à… de la fausse monnaie. Quoiqu’il en soit, Bird se montra de nouveau très à l’aise. À tel point que le 11 février à Carnegie Hall, au cours d’un concert du Jazz at the Philharmonic, Parker, accompagné de Flip Phillips, rejoignit Machito. De conserve ils interprétèrent No Noise, Mango Mangue étant réservé à Bird et Tanga à Flip Phillips. N’en subsistent que des enregistrements privés quasi inaudibles laissant tout de même deviner l’enthousiasme d’un public particulièrement déchaîné, alors qu’une partie du concert – radiodiffusée ou télévisée, les avis divergent – bénéficia d’une prise de son tout à fait correcte.

Bird ne participa qu’au concert new yorkais marquant le début de tournée de printemps du JATP comptant dans ses rangs l’un de ses disciples californien les plus affirmés, Sonny Criss. Les premiers chorus d’alto reviennent à Parker dont on peut d’ailleurs se demander ce qu’au fond de lui-même il pensait d’une telle confrontation… Parmi ses autres interlocuteurs de Parker figuraient Fats Navarro, le troisième membre du triumvirat de la trompette bop, Shelly Manne profitant d’une vacance de l’orchestre Stan Kenton, le tromboniste Tommy Turk alors membre de la formation du ténor Flip Phillips lui aussi présent?; quelqu’un que l’on retrouvera souvent au côté de Bird. Pour l’occasion furent choisis des thèmes fédérateurs comme Leap Here, Lover Come Back to Me et une extrapolation d’Indiana, proche du Ice Freezes Red que Fats Navarro avait gravé avec Tadd Dameron deux ans plus tôt (les progressions d’accords du dit Indiana figuraient d’ailleurs dans le Donna Lee de Miles Davis qu’il avait interprété avec Bird). Cette même soirée, Ella Fitzgerald fit sa toute première apparition au sein de la troupe du Jazz At The Philharmonic?; sans Parker.

Les prestations retransmises depuis le Royal Roost avaient rendu compte de l’évolution du partenariat Bird/Kenny Dorham. Paradoxalement, alors qu’il figure sur nombre de transcriptions radiophoniques et d’enregistrements privés, Kenny Dorham ne participa qu’à deux séances dirigées par Parker pour le compte de Verve ou de Mercury. Grand amateur de mélanges divers et variés, Norman Granz laissait rarement les formations dans l’état. Ainsi au printemps 1949, il imposa à Bird la présence de Tommy Turk - un bon tromboniste si l’on en croît son confrère Carl Fontana - qui n’avait pas grand chose à faire là. Pour ne pas être en reste, Parker exigea la présence d’un joueur de conga, l’ex-kentonien Carlos Vidal… Deux morceaux seulement furent mis en boîte, Cardboard et Visa. Des titres liés à l’actualité.

«?Le Bird était dans sa meilleure forme ce soir-là. Comme toujours immobile, l’air indifférent, l’œil fixe, presque absent?; et son jeu qui contraste si singulièrement avec son attitude, scintillait de mille feux, de trouvailles inattendues, incessantes, abruptes à première vue sans liaison aucune mais construites, organisées avec une logique magistrale.?» Dans le numéro 31 de Jazz Hot daté mars 1949, Charles Delaunay décrivait Parker tel qu’il l’avait vu au Royal Roost. Le mois suivant, il ajoutait : «?Au cours de cette émission je remis officiellement la plaque d’honneur du référendum Down Beat à Charlie Parker. Le moment le plus sensationnel du programme fut la jam session de clôture pendant laquelle Parker et Bechet jouèrent ensemble.?» Down Beat et non Metronome ainsi que l’indique la quasi totalité des discographies.

En tant que saxophoniste alto, Bird n’avait pas remporté le référendum, toutefois la coutume voulait que soient récompensés les trois premiers élus dans chaque catégorie. En conséquence, Parker participa le 21 février à une émission télévisée - une grande première pour lui - au cours de laquelle Charles Delaunay lui remit son «?Award?». Une plaque de bois portant son nom et son classement, ornée d’une croche métallique en relief. Bird, Charles et Chubby Jackson échangèrent quelques mots avant que le récipiendaire n’attaque Now’s the Time avant d’accompagner le danseur à claquettes Teddy Hale sur Lover. Un blues servit de base pour la jam-session finale où, d’autorité, Sidney Bechet prit les choses en main. Avec une telle furia que Bird est quasiment inaudible. Dans ses souvenirs, Charles Delaunay donna une version édulcorée des propos de Bechet qui, nous raconta-t-il, aurait en fait proclamé fièrement «?Je l’ai bien eu, le jeunôt !?»

Quoi qu’il en soit, à l’initiative de Delaunay, conseiller artistique du «Festival International de Jazz» organisé à Paris par Franck Bauer, Parker et Bechet allaient bientôt partir de conserve pour la capitale. Est-ce cette échéance proche qui interpella Norman Granz ? Toujours est-il que fut mise en boîte, dans la précipitation la plus totale, une séance regroupant en studio le quintette tel qu’il s’apprêtait à franchir l’Atlantique. Conséquence : au moment de leur publication furent édités sous les noms de Segment et Diverse, deux versions d’une même composition qui, attribuée à Parker, sonnait plutôt comme un thème de Kenny Dorham. En sus, il n’existe aucun rapport thématique entre Passport I et Passport II, l’un étant un blues – Charles Mc Pherson l’enregistrera en 1964 sous le titre Variations on a Blues by Bird -, l’autre basé sur I Got Rhythm. Un même morceau fut donc publié sous deux titres différents et deux morceaux différents sous un même titre…

Le 7 mai 1949, escorté de Kenny Dorham, Al Haig, Tommy Potter et Max Roach, Bird s’envola pour Paris. Pour la première fois, il quittait le continent américain, expérience qui ne se renouvellera qu’une fois. De tous les musiciens de sa génération, Bird aura été celui qui voyagea le moins.

À la tête de son quintette, Parker se produisit Salle Pleyel concurremment à Hot Lips Page, Sidney Bechet qui, pour l’occasion, entamera une seconde carrière, Miles Davis flanqué de Tadd Dameron et une palanquée de formations françaises et européennes. Une programmation audacieuse à une époque où la querelle des anciens et des modernes – «?figues moisies?» contre «raisins aigres» - battait son plein. Sous le titre «?Jazz-Men?», Claude Baignères écrivit dans le Figaro : «?Partisans du «Be bop?» et du style «?New Orleans» se livrent une lutte sans merci et les spectateurs ne sont pas les derniers à prendre bruyamment part à la bataille : coups de sifflet et applaudissements ont, les uns et les autres, dans le monde du jazz, la valeur d’un éloge : comment interpréter la réaction de ce fanatique qui actionnait désespérément une trompe d’auto ? (3)?» Et ce soir là, Parker n’était pas sur scène… Il se produisit seulement les 8, 9, 14 et 15 mai (en matinée et en soirée) date à laquelle le festival s’acheva sur un Farewell Blues réunissant la troupe au grand complet. Ou presque.

Dans une époque affligée par une disette de papier journal, Combat faisait la part belle au Festival, annonçant quotidiennement les programmes. La rédaction de la plupart des compte-rendus avait été confié à Boris Vian : «?Enfin, le moment capital de la soirée, Charlie «?Zoizeau?» Parker. À la batterie, Max Roach. Messieurs les batteurs, chapeau bas. À la basse, Tommy Potter. Même remarque. Kenny Dorham (trompette) a fait d’incroyables progrès. Quand au Zoizeau… on n’est vraiment pas dans le coup. Ces petits-là, ils ont quatre ou cinq cerveaux, nous n’en avons qu’un… hélas !… Mais tout de même cela suffit pour comprendre que ça laisse derrière soi pas mal de choses (4).?» Dans Jazz News, il ajouta : «?Enfin Charlie le Zoizeau, qui s’amène sur scène l’œil vitreux comme un zombie… et puis c’est le déluge. On est soufflé, ahuri, bavant (noblesse oblige)… On compte et on se fout dedans. Mais pas lui… (5)?»

Reçu dans les familles de musiciens français, choyé, comblé de petits cadeaux, considéré et traité en artiste, Parker n’en revenait pas. Du coup il mena grand train, dépensant pas moins de 350 000 francs de l’époque – soit approximativement 10 000 € - en un peu plus d’une semaine. L’un de ses grands plaisirs rapporta Tommy Potter, consistait à lancer un retentissant «?Garçon ! Champagne !?» à la façon d’Adolphe Menjou dans un film Hollywoodien se déroulant dans la capitale. Cigarette aux lèvres, souriant, entouré de jeunes amateurs, il posa même pour un cliché utilisé comme publicité par «?Maud?», un disquaire sis 4 avenue de Villiers.

Non content de se produire à la Salle Pleyel, Bird se rendit à son habitude dans divers clubs. Lionel Bouffé, saxophoniste et témoin : «?Un certain soir, le bruit avait en effet couru qu’il viendrait peut-être au Club Saint-Germain. Je m’y précipitai, car pour rien au monde, je n’aurais voulu rater ça. Lorsque j’arrivai, la salle, ou plutôt la cave, était bourrée de musiciens. Charlie Parker était effectivement là, assis, sur un tabouret, devant une petite table située en bas et à droite de l’estrade sur laquelle des musiciens étaient en train de jouer. Il était évidemment très entouré. Tous le suppliaient d’aller jouer avec les autres. Mais il faisait toujours «?non?» de la tête, tout en jetant à la ronde des regards inquiets en direction de l’estrade. Finalement, après au moins une heure de supplications, il commença à déballer son alto. Il s’était enfin décidé à jouer mais refusait obstinément de monter sur l’estrade ! Il s’installa devant celle-ci, juché sur un haut tabouret qu’on avait été cherché exprès […] Une fois installé, il joua… superbement ! Il joua même beaucoup et longtemps, manifestement pour son plaisir mais surtout pour le nôtre (6).?»

Bien que Bird se soit conduit d’une manière que l’on pourrait qualifier de «?décalée?» aux dires des témoins, aucun scandale majeur ne marqua son séjour parisien à l’exception de celui qu’il déclencha Salle Gaveau en manifestant bruyamment son approbation durant un concert donné par Andres Segovia. Le guitariste s’arrêta même de jouer, sans se douter un instant que le perturbateur n’était autre que Charlie Parker.

Il en alla tout autrement le 12 mai. Débarquant à la gare de Roubaix peu avant le début du concert prévu dans cette ville, Bird aurait manifesté, selon une «?figue moisie?», des exigences gastronomiques peu compatibles avec le lieu et l’heure. D’après un «?raisin aigre?», les dites «?figues moisies?» avaient prémédité un sabotage de la soirée… en faisant boire Parker. Peut-être… la guerre du jazz ne reculait alors devant aucun coup bas mais une telle hypothèse démontre que les comploteurs faisaient bon marché des capacités de résistance à l’alcool de Bird.

Parker souleva l’enthousiasme de spectateurs qui avaient patienté durant un laps de temps suffisant pour que l’orchestre amateur jouant en première partie ait commencé à ré-attaquer son répertoire, assez réduit il faut le dire. Un enregistrement réalisé par l’un des musiciens de cette formation montre que le répertoire servi à Roubaix restait éminemment classique, à l’exception toutefois de la présence de Lover Man, thème que Parker ne jouait plus depuis la fameuse séance californienne.

Par contre, sous le titre «?Jazz au Colisée ou le triomphe du chahut?», la presse locale tira à boulets rouges sur Bird auquel il était reproché de n’avoir joué qu’une quarantaine de minutes. «?Sur le plateau, quatre noirs et un blanc, élégants, indolents, en f…. le moins possible (7).?» La veille à Marseille, le concert avait été beaucoup plus calme car il n’avait guère drainé les foules, les deux tiers seulement de la salle du cinéma Rex étant occupés… Les finances du Hot Club de Marseille eurent bien du mal à s’en remettre. Charlie Parker avait-il le pressentiment de ce demi-échec ? Toujours est-il qu’il affiche un air particulièrement désabusé sur la photo prise par Maurice Ploton, reproduite dans le livre de Michel Samson et Gilles Suzanne «?À fond de cale - 1917-2011, un siècle de jazz à Marseille?».

Un certain nombre des prestations de Bird avaient été transmises sur les ondes en direct. Ce qui en fut conservé provient majoritairement de sources artisanales. Il faut le regretter encore que, dans leur majorité, les concerts de Pleyel ne semblent pas s’être élevés au-dessus d’une bonne moyenne. À l’occasion d’une version de Salt Peanuts, il remplace les dernières interjections par «?la même chose, la même chose?» pour la plus grande joie des spectateurs qui, tous, n’étaient pas venus là par hasard : sa reprise du break de A Night in Tunisia fut acclamée par la salle, tout comme les 4/4 échangés avec Max Roach sur Moose the Mooche. Jean Berdin raconta qu’après un après-midi passé en compagnie d’Hubert et Raymond Fol à écouter chez eux Le Sacre du Printemps de Stravinsky, Bird en joua une longue phrase le soir même à Pleyel.

Tous les membres du quintette se montrèrent à la hauteur de leur tâche à l’exemple de Kenny Dorham qui, sur la seule version ayant survécu de Hot House, sert un chorus exemplaire de ce «?running style?» qui était sa marque de fabrique. Une curiosité : sous le titre de Prince Albert fut publié un 78t reprenant une version de All the Things You Are interprétée à Pleyel mais tronquée et amputée du chorus de Bird?; Max Roach était censé en être le leader…

Ce que Parker avait trouvé à Paris lui donna à réfléchir. Des exilés comme Don Byas ou Kenny Clarke l’incitaient à rester là où il était apprécié à sa juste valeur. Sur le coup il envisagea de s’installer six mois par an à Paris pour étudier. Un vœu pieux, il n’y reviendra qu’une seule fois. En coup de vent.

Alain Tercinet

© 2013 Frémeaux & Associés

(1) Robert Reisner, «?Bird, la légende de Charlie Parker?», trad. François Billard et Catherine Weinberger-Thomas, Belfond, Paris, 1989.

(2) «?Lee Konitz talks to Mike Baillie?», Jazz Journal International vol. 40, n°5, mai 1985.

(3) Le Figaro, 14/15 mai 1949.

(4) Combat, 10 mai 1949.

(5) Jazz News, n°6, juin 1949.

(6) Lionel Bouffé «?Aventure Jazz…?», publié par souscription aux dépens de l’auteur, Neuilly, 1991.

(7) Nord Éclair, 14 mai 1949.

BIRD Vol. 6 – NOTES DISCOGRAPHIQUES

Down Beat Award Show of 1949

Présent à la cérémonie, Charles Delaunay donne Ralph Sutton comme pianiste et non Joe Bushkin dont le nom figure dans l’ensemble des discographies.

Le show télévisé comprenait :

Shorty Sherock (tp)*?; Benny Morton (tb)*?; Sol Yaged (cl)*?; Sidney Bechet (ss)*?; Charlie Parker (as) : Ralph Sutton (p)?; Chubby Jackson (b, mc)?; George Wettling (dm)?; Teddy Hale (tap dance-1)?; Charles Delaunay (mc).

Station WPIX, NYC, 21/2/1949

NOW’S THE TIME (C. Parker) 3’22

LOVER – 1 (R. Rogers, L. Hart) 2’57

I CAN’T GET STARTED /BLUES*

(V. Duke, I. Gershwin/trad) 5’37

La très mauvaise qualité sonore de ce qui subsiste de ce show nous a contraint à l’écarter. Pour la même raison, nous avons fait également l’impasse sur une seconde prestation télévisuelle :

Adventures in Jazz CBS-TV, NYC, 4/3/1949

Miles Davis (tp)?; Charlie Parker (as)?; Mike Colucci (p)?; unknown (b)?; Max Roach (dm)?; W. B. Williams (mc).

ANTHROPOLOGY (C. Parker, D. Gillespie) 2’52

Miles Davis, Max Kaminsky (tp)?; Kai Winding, Will Bradley (tb)?; Joe Marsala (cl)?; Charlie Parker (as)?; Joe Sullivan-1 (p)?; unknown (b)?; Specs Powell (dm)?; Ann Hathaway (voc)*.

I GET A KICK OUT OF YOU* (C. Porter) 2’59

BIG FOOT/JAM BLUES (C. Parker) 5’53

Festival International de Jazz – Paris.

Les enregistrements du quintette de Parker effectués par des amateurs de façon artisanale ont été publiés à diverses reprises bien qu’ils frisent souvent l’inaudible et souffrent de coupes. Nous ne publions ici que cinq interprétations complètes venues d’autres sources dont la qualité sonore reste acceptable, compte tenu des circonstances et de leur valeur historique. Le concert de Roubaix a été lui aussi édité :

Charlie Parker Quintet – Cinéma Colisée, Roubaix, 12/5/1949

Ornithology (4’20) – Out of Nowhere (3’44) – Cheryl (2’46) – 52nd Street Theme (1’12) – Lover Man (4’24) – Groovin’ High (4’31) – Half Nelson (4’32) – 52nd Street Theme (2’54)

Farewell Blues

Le morceau terminant le Festival International de jazz - toujours incomplet - a été publié avec des durées différentes. On trouvera ici la version la plus complète existant. S’y font entendre à la suite de Sidney Bechet, Miles Davis et Charlie Parker. La seule occasion où ils jouèrent ensemble à Paris.

A genuine “complete” set of the recordings left by Charlie Parker is impossible today and will remain so for a long time to come. Few musicians aroused so much passion during their own lifetimes and today, more than half a century after his disappearance, previously-unreleased music is published, and other titles – duly listed – will also come to light. A good many contain only solos by Bird, as they were recorded – privately – by musicians wanting to dissect his style. Regarding their sound-quality, most of them are at the limit: barely audible, sometimes almost intolerable, but in fact understandable: those who captured these sounds used portable recorders that wrote direct-to-disc, or wire-recorders, “tapes” (acetate or paper) and other machines now obsolete. Obviously they all produced sound-carriers that were fragile.

Of course, no solo ever played by Charlie Parker is to be disregarded. But a chronological compilation of almost everything he recorded – either inside a studio or on radio for broadcast purposes – does make it possible to provide an exhaustive panorama of the evolution of his style (Parker was, after all, one of the greatest geniuses in jazz), and to do so under acceptable listening-conditions. However, since we refer to style, the occasional presence here of some private recordings is indispensable, whatever the quality of the sound.

THE COMPLETE CHARLIE PARKER

STUDIO & RADIO VOLUME 6

“PASSPORT” 1949

For four months, the performances of the Charlie Parker Quintet at the Royal Roost were recorded; the results provided a detailed logbook of the way Bird behaved – both musically and personally – in front of a club audience. Contrary to his behaviour in the studios, Bird wasn’t keeping an eye on posterity when he worked in a club environment. Most often, his improvisations remained under control even though he showed daring, and one could notice a number of his quirks, like his obsession with repeating certain quotes throughout his choruses – and not only at the Royal Roost –, quotes such as Buttons and Bows, Country Gardens (an English folk song arranged by Percy Granger), The Woody Woodpecker Song, sometimes High Society, or else the Habanera from “Carmen”, even Jingle Bells…

Another observation one can make is that the repertoire exploited by Bird was limited, even though he knew scores of tunes that included not only a number of his own remarkable compositions, but also variations on blues pieces and extrapolations which sprang from his imagination and were based on the traditional thirty-two bars of a standard. At the Royal Roost, the tunes which found particular favour with Bird were Scrapple From The Apple (played five times), Salt Peanuts (four times), Be Bop and Groovin’ High (three times each), followed by Half Nelson, Cheryl and Barbados.

Parker could also show interest in fashionable hits, like Frank Loesser’s On a Slow Boat to China for example (three versions), a somewhat hackneyed tune whose omnipresence – you could hear it on radio, jukeboxes, even the lips of people in the street – drove Will Eisner’s comic-strip hero The Spirit to the verge of depression. As for White Christmas (it appears in Vol. 5), Bird included it just because it suited the tune.

Club performances unfolded mostly according to the same schema observed in the studios: the alto and trumpet would state the theme either in unison or on the octave, and then restate it in conclusion before a possible coda. The way things happened in a club was open to change: there were brief piano introductions (more rarely on bass), or with an initial drum break. On records, the alto and trumpet shared most of the solos, with the pianist generally entitled to just one half-chorus. In front of an audience, Parker’s interventions, like those of the bass and drums, could stretch out, although they stayed on the right side of logorrhoea: Parker decreed that a musician ought to be capable of saying what he had to say within the three-minute limit imposed by 78rpm records.

The Royal Roost broadcasts faithfully reflect the life of a group which was reliant on the moods of its chief. Parker was in a jocular frame of mind on January 15th and deploys all his tools of seduction. He was totally absent on the 29th and, after a rather dubious statement of Groovin’ High (to say the least), followed by a shred of an incoherent phrase, he hands over to Kenny Dorham without warning, leaving his trumpeter dumbstruck. Bird keeps silent until an awkward restatement of the theme, followed by a coda which is just as erratic. Conversely, there’s the Hot House dated January 15th, Scrapple from the Apple played the following week, and the Be Bop from February 12th, which surpass even the best studio versions of those pieces. As for Bird’s Groovin’ High of February 19th, his improvisation serves to illustrate Lennie Tristano’ observation: “This may be compared to a jig-saw puzzle which can be put together in a hundred of ways, each time showing a definite picture in which the general character differs from all the other possible pictures.”1 The opinion of Lee Konitz was in the same ball-park: “I don’t think of Parker’s music as being instantly improvised. I think he was a very brilliant man who was able to pre-compose perfect music, and who was secure in the knowledge of what he was going to play, and so could put all his enormous energy into the placement of the music and his expression.”2 Curiously enough, the following week saw Parker miss his famous break on A Night in Tunisia. Critic Brian Priestley would point out that the lack of coordination you can feel on this occasion somehow takes you back to that famous “Lover Man” session.

In a club, Parker never refused a guest. In the previous volume of this series you can hear him celebrating the New Year with a group led by Charlie Ventura; they’d all come over to join Parker & Co. This time, on two occasions, vocalists Dave Lambert and Buddy Stewart are the guests who step up onstage. The former later found fame as part of the Lambert, Hendricks & Ross trio, while the second would die in a traffic accident in 1950.

For the three final radio broadcasts, Bird’s quintet metamorphosed into a septet with the addition of two accomplices: Milt Jackson on vibraphone and tenor-player Lucky Thompson, who’s in top form on Cheryl. The evenings they all spent at the Royal Roost came to an end on March 12th 1949 with a version of Chasin’ the Bird lasting over six minutes; a perfect note on which to close.

At the same time as he was appearing on Broadway, Parker pursued his musical adventures. Even before the results of their previous collaboration were released, Parker met up again with Machito and His Afro-Cuban Orchestra. It seems that Norman Granz reacted so favourably to test-pressings of Mango Mangue that he encouraged other experiments of the same kind. Parker gave the name Okiedoke to a composition written by Rene Hernandez and Machito, and the title seems ambiguous depending on its pronunciation: Parker would say “Okie-dokie” to mean “OK”, and “Okie-doke” to mean “not OK” [an “Okie-doke” was the name given to a wooden nickel, and even the kind of bad weed Parker wouldn’t want to buy…) Whatever he was up to with words, Parker showed himself to be completely at ease with the music, and at Carnegie Hall on February 11th – it was a JATP concert – Parker, accompanied by Flip Phillips, played with Machito again. They played No Noise together while Mango Mangue was reserved for Bird and Tanga for Flip Phillips. The only remains of that concert are almost inaudible private recordings, yet they allow you to glimpse the enthusiasm of a wild, noisy audience; other parts of the concert – either televised or aired by radio, opinions differ – have perfectly correct sound.

Bird only took part in the New York concert which marked the beginning of the spring JATP tour, and in the band’s ranks was a Parker disciple who’d come to the forefront: Sonny Criss. Parker takes the first alto choruses, and you wonder what he had at the back of his mind during their confrontation… Parker’s other partners included Fats Navarro (the third member of the bop trumpet triumvirate), Shelly Manne (momentarily on vacation from Stan Kenton’s orchestra), and trombonist Tommy Turk, who was then with the band of tenor-player Flip Phillips (the latter was also there on the night, and later he would often find himself alongside the Bird). A few federative themes were chosen for the occasion, like Leap Here, Lover Come Back to Me, and an extrapolation of Indiana which was close to the Ice Freezes Red piece recorded by Fats Navarro with Tadd Dameron two years previously. The chord progressions of that Indiana, incidentally, also appear in Miles Davis’ Donna Lee, which he’d played with Parker. That same evening, Ella Fitzgerald made her very first appearance with the JATP troupe… without Parker.

The Royal Roost broadcasts translated the way Bird’s partnership with Kenny Dorham was evolving. Given that Dorham appears on a number of radio transcriptions and private recordings, it’s a paradox that the trumpeter appears on only two of Parker’s sessions for Verve or Mercury. Norman Granz was a great fan of mixed associations, and he rarely left bands as he found them: in the spring of 1949 he imposed Tommy Turk on Parker – Tommy was a good trombone-player according to his colleague Carl Fontana – even if he had no reason at all to be there. Never one to be left behind, Parker demanded the presence of a conga player, a Kenton alumnus named Carlos Vidal… They only recorded two tunes, Cardboard and Visa, but they were up to date.

In Jazz Hot’s March ‘49 issue (N°31), Charles Delaunay described the Parker he’d seen at the Royal Roost: “The Bird showed his best form that night. Motionless, as always, looking indifferent, his eye fixed on something distant, he was almost absent... But his playing [was in] singular contrast with his attitude, sparkling with a thousand lights and constant unexpected discoveries which at first seemed abrupt and totally unrelated, but they were constructed and organized with masterful logic.” A month later Delaunay added, “During the course of that programme I gave Parker the official plaque honouring his place in the Down Beat poll. The most sensational moment was the closing jam session in which Parker and Bechet played together.” And yes, it was indeed Down Beat, not Metronome as most discographies have it.

Bird hadn’t won the alto poll; it was customary for an award to be given to the first three in each category, which explains Parker’s presence on February 21st in a television show – a first for Parker – during which Delaunay handed him his “Award”: a wooden plaque bearing his name and his place in the poll, complete with the famous metal quaver. Bird, Charles and Chubby Jackson exchanged a few words, and the award-winner jumped into Now’s the Time before accompanying tap-dancer Teddy Hale on Lover. The blues served as a warm-up for the final jam in which Sidney Bechet showed his authority by taking matters into his own hands. He did it in such a rage that Bird is almost inaudible. In his memoirs, Charles Delaunay gives a diluted version of what was actually said by Bechet: apparently he proudly proclaimed, “I got that youngster!”

Delaunay was the artistic adviser for the International Jazz Festival which Franck Bauer organized in Paris, and his advice in this case was to have Parker and Bechet make the trip to the French capital. Did the approach of that event give Granz food for thought? Maybe, because a record-session was precipitated in order to bring together the same quintet which was preparing to cross the Atlantic. One of its direct consequences was the release of Segment and Diverse, actually two versions of the same composition (attributed to Parker, they actually sound rather like a Kenny Dorham theme); another result was Passport I and Passport II, which have no single theme to link them: one is a blues – Charles McPherson would record it in 1964 under the title Variations on a Blues by Bird –, the other a piece based on I Got Rhythm. So one piece was recorded and released under two different titles, and two different pieces were released under one title…

On May 7th 1949, accompanied by Kenny Dorham, Al Haig, Tommy Potter and Max Roach, the Bird flew to Paris. He was leaving American soil for the first time, and would only do it again on one more occasion. Of all the musicians of his generation, Parker was the one who travelled the least.

Fronting his quintet, Parker appeared at the Salle Pleyel at the same time as Hot Lips Page, Sidney Bechet (who seized the occasion to begin a second career), Miles Davis flanked by Tadd Dameron, and a whole bunch of French and European bands. The bill was quite daring for a period when the quarrel between old and new/ancient and modern was at its height (the French refer to those quibbles as “rotten figs versus sour grapes”). The French daily paper Le Figaro carried an article by Claude Baignères under the banner “Jazz-Men”; part of it said, “Partisans of ‘Be bop’ and the ‘New Orleans’ style are doing merciless battle, and spectators aren’t the last ones to join in: blowing whistles and applauding, in the jazz world, are both signs of praise, but how do you interpret the reaction of that fanatic who was desperately leaning on his car-horn?” 3 And Parker wasn’t even onstage that night… He only made appearances on May 8, 9, 14 and 15 (matinee and evening concerts), the last being the night the Festival ended with a Farewell Blues featuring the entire cast. Or almost.

At a time when there was a serious shortage of paper for printing the news, the journal Combat devoted a lot of space to the Festival, carrying the full programme every day. Most of the reviews were written by Boris Vian: “Finally, the evening’s capital moment: Charlie “Birdie” Parker. On drums, Max Roach. Drummers and gentlemen, hats off. On bass, Tommy Potter. Same observation. Kenny Dorham (trumpet) has made incredible progress. As for the Birdie… we aren’t really in the same league. Those kids have four or five brains, while we only have one… Alas! But all the same, it’s enough of a brain for us to realize that quite a few things have left us behind.”4 In Jazz News he added, “Finally we have Charlie the Birdie, who drags himself onstage with the glassy eye of a zombie… and then, a deluge! We’re blown away, flabbergasted, blabbing about it (noblesse oblige)… We count, and really screw up… But not he.”5

Parker couldn’t get over it: French musicians invited him home; he was pampered, showered with gifts, considered and treated like an artist… So Bird lived it up: he spent some 350,000 French Francs (around $13,000 of today’s money) in just over a week. According to Tommy Potter, one of his greatest pleasures was yelling “Garçon! Champagne!”, sounding like a loud Adolphe Menjou in some Hollywood movie. With a cigarette dangling from his lips, wearing a big grin and surrounded by young fans, he even posed for a photograph that was used as an ad by “Maud’s” record-shop at N°4, avenue de Villiers.

Bird didn’t content himself with his Salle Pleyel appearance; as was his habit, he went out to the clubs. Saxophonist Lionel Bouffé gave this eye-witness account: “One night there was a real rumour that he might come down to the Club Saint-Germain. I rushed over there because I wouldn’t have missed that for the world. When I got there, the room or rather the cellar was jam-packed with musicians. And Charlie Parker was right there, sitting on a stool at a little table to the right below the stage where the musicians were playing. Of course, there were people all round him. Everyone was begging him to get up and play with the others. But he always shook his head as a “no”, with a worried glance at the stage now and then. Finally, when all this had gone on for over an hour, he began unpacking his alto. He’d finally decided to play, but he was stubbornly refusing to climb onstage! He went over in front of the stage and perched on a high stool that someone had fetched for him […] and once he was ready, he played… it was superb! He even played for a long time, obviously for his own pleasure but especially for ours.”6

Although Bird behaved in a way that was “weird” (as some who saw him said), no major scandal disrupted his stay in Paris, except for the one he caused at the Salle Gaveau, that is, when he loudly showed his approval of Andres Segovia. The guitarist even stopped playing at one point: he didn’t have a clue that the nuisance was none other than Charlie Parker.

Things were quite different on May 12th. When he got off the train in Roubaix shortly before the concert he was due to play there, Bird (according to one “rotten fig”) seems to have made some gastronomic demands that were hardly suitable, given the place and time. One of the “sour grape” clan said that some “rotten figs” had premeditated sabotage: they’d manoeuvred Bird into taking a drink or two. Perhaps so – the jazz war left no strategy unexplored, however low people sank – but the hypothesis at least shows that the plotters didn’t go to any great expense in testing Bird’s capacity for liquor.

Parker aroused wild enthusiasm in an audience who’d been waiting very patiently; they’d waited so long, in fact, that the amateur band playing the first half of the concert found enough time to attack its repertoire again from the beginning, admittedly a short repertoire. A recording made by one of the musicians from that band shows that the tunes which Bird delivered in Roubaix were eminently classic titles, with the exception of Lover Man, a tune which Bird hadn’t been playing since the famous California session.

On the other hand, the local press – the banner read “Jazz at the Coliseum or the Triumph of Uproar” – opened fire on Parker with all guns blazing, blaming him for staying only forty minutes onstage: “On the boards, four blacks and one white, elegant, apathetic, doing sweet f… all.”7 Or words to that effect. The night before – in Marseilles – the concert had been much quieter because the house wasn’t full: only three-quarters of the seats at the Rex Cinema were taken. The Hot Club de Marseille had great trouble balancing its books. Did Charlie Parker have a premonition of this semi-flop? He looks particularly disenchanted in Maurice Ploton’s photo inside the book by Michel Samson and Gilles Suzanne entitled “At the bottom of the hold – 1917-2011, a century of jazz in Marseilles”.

A number of Bird’s performances were broadcast live over the air, and the recordings which have been preserved come from mainly cottage-industry sources. It’s still regrettable even though most of the Pleyel concerts sound no more than average. One version of Salt Peanuts has Parker replacing the final interjections with “the same thing, the same thing”, to the great joy of the spectators, none of whom was there by chance: Parker’s reprise of the break in A Night in Tunisia was acclaimed by the whole room, as are the fours exchanged with Max Roach on Moose the Mooche. Jean Berdin said that after spending an afternoon with Hubert and Raymond Fol at their home listening to Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring, Bird played a long phrase from it the same night at Pleyel.

Every member of the quintet shows himself equal to the task, following the example of Kenny Dorham who, on the only surviving version of Hot House, plays a chorus which exemplifies the running style which was his trademark. There’s also a curiosity: under the title Prince Albert, a 78rpm disc appeared with a reprise of the version of All the Things You Are played at Pleyel, but it was shortened by the amputation of Bird’s chorus. Max Roach was supposed to be the group’s leader…

What Parker discovered in Paris gave him food for thought. Exiles like Don Byas or Kenny Clarke encouraged him to stay where he was appreciated according to his worth. So, Bird decided to live in Paris for six months every year, and study. It was a pious hope: he returned just once, and then only for a quick visit.

Adapted by Martin Davies from the French text of Alain Tercinet

© 2013 Frémeaux & Associés.

(1) Robert Reisner, “Bird: The Legend Of Charlie Parker”, Da Capo Press, 1977.

(2) “Lee Konitz talks to Mike Baillie”, Jazz Journal International Vol. 40, N°5, May 1985.

(3) Le Figaro, May 14/15, 1949.

(4) Combat, May 10, 1949.

(5) Jazz News N°6, June 1949.

(6) Lionel Bouffé, “Aventure Jazz…” published by subscription by the author, Neuilly, 1991.

(7) Nord Éclair, May 14th 1949.

BIRD Vol. 6 – DISCOGRAPHICAL NOTES

Down Beat Award Show of 1949

There for the ceremony, Charles Delaunay gives Ralph Sutton as the pianist and not Joe Bushkin whose name appears in all the discographies.

The televised show featured Shorty Sherock (tp)*; Benny Morton (tb)*; Sol Yaged (cl)*; Sidney Bechet (ss)*; Charlie Parker (as); Ralph Sutton (p); Chubby Jackson (b, mc); George Wettling (dm); Teddy Hale (tap dance-1); Charles Delaunay (mc).

Station WPIX, NYC, 21/2/1949

NOW’S THE TIME (C. Parker) 3’22

LOVER – 1 (R. Rogers, L. Hart) 2’57

I CAN’T GET STARTED /BLUES*

(V. Duke, I. Gershwin/trad) 5’37

The very bad sound-quality of what remains of this show made it necessary for us to leave it out. For the same reason we also omitted a second television performance:

Adventures in Jazz CBS-TV, NYC, 4/3/1949

Miles Davis (tp); Charlie Parker (as); Mike Colucci (p); unknown (b); Max Roach (dm); W. B. Williams (mc).

ANTHROPOLOGY (C. Parker, D. Gillespie) 2’52

Miles Davis, Max Kaminsky (tp); Kai Winding, Will Bradley (tb); Joe Marsala (cl); Charlie Parker (as); Joe Sullivan-1 (p); unknown (b); Specs Powell (dm); Ann Hathaway (voc)*.

I GET A KICK OUT OF YOU* (C. Porter) 2’59

BIG FOOT/JAM BLUES (C. Parker) 5’53

Festival International de Jazz – Paris.

The makeshift recordings of Parker’s quintet made by amateurs have been released on various occasions even though often inaudible. They also have cuts. Here you can find only five complete performances from other sources; the sound-quality remains acceptable given the circumstances and their historic value. The Roubaix concert was also released:

Charlie Parker Quintet – Cinéma Colisée, Roubaix, 12/5/1949

Ornithology (4’20) – Out of Nowhere (3’44) – Cheryl (2’46) – 52nd Street Theme (1’12) – Lover Man (4’24) – Groovin’ High (4’31) – Half Nelson (4’32) – 52nd Street Theme (2’54)

Farewell Blues

The piece closing the International Jazz Festival – still incomplete – has been released with different timings. Here you can find the most complete existing version, where after Bechet you can hear Miles Davis and Charlie Parker. It was the only time they played together in Paris…

discographie - CD 1

CHARLIE PARKER ALL-STARS

Kenny Dorham (tp)?; Charlie Parker (as)?; Al Haig (p)?; Tommy Potter (b)?; Joe Harris (dm)?; Symphony Sid (mc). Royal Roost, NYC, 15/1/1949

1. Announcer (Radio Transcription) 0’59

2. SCRAPPLE FROM THE APPLE (C. Parker) (Radio Transcription) 4’11

3. Announcer (Radio Transcription) 0’26

4. BE-BOP (D. Gillespie) (Radio Transcription) 3’19

5. Announcer (Radio Transcription) 0’15

6. HOT HOUSE (T. Dameron) (Radio Transcription) 5’11

Idem, Max Roach (dm). Royal Roost, NYC, 22/1/1949

7. Announcer (Radio Transcription) 1’14

8. OOP BOP SH’BAM (D. Gillespie, W. Gil Fuller) (Radio Transcription) 4’56

9. Announcer (Radio Transcription) 0’40

10. SCRAPPLE FROM THE APPLE (C. Parker) (Radio Transcription) 4’33

11. Announcer (Radio Transcription) 0’22

12. SALT PEANUTS (D. Gillespie, K. Clarke) (Radio Transcription) 4’07

13. Announcer (Radio Transcription) 0’35

Royal Roost, NYC, 29/1/1949

14. Announcer (Radio Transcription) 0’57

15. GROOVIN’ HIGH (D. Gillespie) (Radio Transcription) 3’44

16. Announcer (Radio Transcription) 0’20

Royal Roost, NYC, 5/2/1949

17. Announcer (Radio Transcription) 1’00

18. SCRAPPLE FROM THE APPLE (C. Parker) (Radio Transcription) 3’25

19. Announcer (Radio Transcription) 0’23

20. BARBADOS (C. Parker) (Radio Transcription) 3’51

21. Announcer (Radio Transcription) 0’08

22. SALT PEANUTS (D. Gillespie, K. Clarke) (Radio Transcription) 3’34

23. Announcer (Radio Transcription) 1’29

CHARLIE PARKER with MACHITO AND HIS AFRO-CUBAN ORCHESTRA

Charlie Parker (as) with Mario Bauzá, Paquito Davilla, Bob Woodlen (tp) : Gene Johnson, Freddie Skerritt (as)?; José Madera (ts)?; Leslie Johnakins (bs)?; René Hernandez (p)?; Roberto Rodriguez (b)?; José Mangual (bgo)?; Luis Miranda (cga)?; Umbaldo Nieto (tbl)?; Machito (marac.)?; band (voc). NYC, january 1949

24. OKIEDOKE (H. Machito) (Mercury/Clef 11017/mx. 2171-1) 3’02

JAZZ AT THE PHILHARMONIC

Fats Navarro (tp)?; Tommy Turk (tb)?; Charlie Parker, Sonny Criss (as)?; Flip Phillips (ts)?; Hank Jones (p)?; Ray Brown (b)?; Shelly Manne (dm). Carnegie Hall, NYC, 11/2/1949

25. LEAP HERE (N. King Cole) (Aircheck) 11’21

26. INDIANA (J. F. Hanley, B. McDonald) (Aircheck) 11’16

Total : 76’ 02

discographie - CD 2

JAZZ AT THE PHILHARMONIC

Fats Navarro (tp)?; Tommy Turk (tb)?; Charlie Parker, Sonny Criss (as)?; Flip Phillips (ts)?; Hank Jones (p)?; Ray Brown (b)?; Shelly Manne (dm). Carnegie Hall, NYC, 11/2/1949

1. LOVER COME BACK TO ME (S. Romberg, O. Hammerstein II) (Aircheck) 15’27

CHARLIE PARKER ALL-STARS

Kenny Dorham (tp)?; Charlie Parker (as)?; Al Haig (p)?; Tommy Potter (b)?; Max Roach (dm)?; Symphony Sid (mc). Royal Roost, NYC, 12/2/1949

2. Announcer (Radio Transcription) 0’07

3. SCRAPPLE FROM THE APPLE (C. Parker) (Radio Transcription) 4’33

4. Announcer (Radio Transcription) 0’16

5. BARBADOS (C. Parker) (Radio Transcription) 3’53

6. Announcer (Radio Transcription) 0’13

7. BE-BOP (D. Gillespie) (Radio Transcription) 3’16

CHARLIE PARKER ALL-STARS

Kenny Dorham (tp)?; Charlie Parker (as)?; Al Haig (p)?; Tommy Potter (b)?; Max Roach (dm)?; Symphony Sid (mc). Royal Roost, NYC, 19/2/1949

8. Announcer (Radio Transcription) 0’05

9. GROOVIN’ HIGH (D. Gillespie) (Radio Transcription) 4’48

10. Announcer (Radio Transcription) 0’05

11. CONFIRMATION (C. Parker) (Radio Transcription) 3’32

12. Announcer (Radio Transcription) 0’12

13. SALT PEANUTS (D. Gillespie, K. Clarke) (Radio Transcription) 3’39

CHARLIE PARKER ALL-STARS

Kenny Dorham (tp), poss. Miles Davis (tp) add. on *?; Charlie Parker (as)?; Lucky Thompson (ts)?; Al Haig (p)?; Milt Jackson (vib)?; Tommy Potter (b)?; Max Roach (dm)?; Dave Lambert, Buddy Stewart (voc), Symphony Sid (mc). Royal Roost, NYC, 26/2/1949

14. Announcer (Radio Transcription) 0’09

15. HALF NELSON (M. Davis) (Radio Transcription) 3’32

16. Announcer (Radio Transcription) 0’15

17. A NIGHT IN TUNISIA *(D. Gillespie, F. Paparelli) (Radio Transcription) 4’38

18. Announcer (Radio Transcription) 0’24

19. SCRAPPLE FROM THE APPLE (C. Parker) (Radio Transcription) 4’40

20. Announcer (Radio Transcription) 0’23

21. DEEDLE (Radio Transcription) 2’08

22. Announcer (Radio Transcription) 0’30

23. WHAT THIS ? (Radio Transcription) 1’36

CHARLIE PARKER ALL-STARS

Kenny Dorham (tp)?; Charlie Parker (as)?; Lucky Thompson (ts)?; Al Haig (p)?; Milt Jackson (vib)?; Tommy Potter (b)?; Max Roach (dm)?; Dave Lambert, Buddy Stewart (voc), Symphony Sid (mc).

Royal Roost, NYC, 5/3/1949

24. Announcer (Radio Transcription) 1’23

25. CHERYL (C. Parker) (Radio Transcription) 3’51

26. Announcer (Radio Transcription) 0’27

27. ANTHROPOLOGY (C. Parker, D. Gillespie) (Radio Transcription) 5’16

Total : 69’42

discographie - CD 3

CHARLIE PARKER ALL-STARS

Kenny Dorham (tp)?; Charlie Parker (as)?; Lucky Thompson (ts)?; Al Haig (p)?; Milt Jackson (vib)?; Tommy Potter (b)?; Max Roach (dm)?; Dave Lambert, Buddy Stewart (voc), Symphony Sid (mc).

Royal Roost, NYC, 5/3/1949

1. Announcer (Radio Transcription) 1’10

2. HURRY HOME (Radio Transcription) 2’24

3. DEEDLE (Radio Transcription) 2’09

4. ROYAL ROOST BOP (Radio Transcription) 2’09

Kenny Dorham (tp)?; Charlie Parker (as)?; Lucky Thompson (ts)?; Al Haig (p)?; Milt Jackson (vib)?; Tommy Potter (b)?; Max Roach (dm)?; Symphony Sid (mc). Royal Roost, NYC, 12/3/1949

5. Announcer (Radio Transcription) 0’07

6. CHERYL (C. Parker) (Radio Transcription) 3’21

7. Announcer (Radio Transcription) 0’21

8. ON A SLOW BOAT TO CHINA (F. Loesser) (Radio Transcription) 3’39

9. Announcer (Radio Transcription) 1’14

10. CHASIN’ THE BIRD (C. Parker) (Radio Transcription) 6’30

CHARLIE PARKER AND HIS ORCHESTRA

Kenny Dorham (tp)?; Tommy Turk (tb)?; Charlie Parker (as)?; Al Haig (p)?; Tommy Potter (b)?; Max Roach (dm)?; Carlos Vidal (bgo) NYC, spring 1949

11. CARDBOARD (C. Parker) (Norgran MGN 1035/mx. 292-3) 3’09

12. VISA (C. Parker) (Mercury/Clef 11022/mx. 293-4) 2’59

CHARLIE PARKER AND HIS ORCHESTRA

Kenny Dorham (tp)?; Charlie Parker (as)?; Al Haig (p)?; Tommy Potter (b)?; Max Roach (dm).

NYC, 5/5/1949

13. SEGMENT (C. Parker) (Verve MGV 8009/mx. 294-3) 3’20

14. DIVERSE /SEGMENT (C. Parker) (alternate) (Verve MGV 8009/mx. 296-3) 3’17

15. PASSPORT I (C. Parker) (Clef 11022/mx. 295-2) 2’55

16. PASSPORT II (C. Parker) (Verve MGV 8000/mx. 295-5) 3’00

CHARLIE PARKER QUINTET

Kenny Dorham (tp)?; Charlie Parker (as)?; Al Haig (p)?; Tommy Potter (b)?; Max Roach (dm), prob. Maurice Cullaz (mc ).

Festival International de Jazz, Salle Pleyel, Paris, 8, 9, 14, 15/5/1949

17. MOOSE THE MOOCHE (C. Parker) * (Radio Transcription) 5’34

18. HOT HOUSE (T. Dameron) * (Radio Transcription) 5’45

19. ALLEN’S ALLEY (D. Best) * (Radio Transcription) 4’29

20. 52nd STREET THEME (T. Monk) * (Radio Transcription) 4’54

21. SALT PEANUTS (D. Gillespie, K. Clarke) (15/5) (Radio Transcription) 3’41

* Inédit

JAM SESSION

Hot Lips Page, Miles Davis, Bill Coleman, Aimé Barelli (tp)?; Russell Moore (tb)?; Sidney Bechet, Pierre Braslavsky (ss)?; Hubert Rostaing (cl)?; Charlie Parker (as)?; Don Byas, James Moody (ts)?; Bernard Peiffer (p)?; Hazy Osterwald (vib)?; Toots Thielemans (g)?; Tommy Potter (b)?; Max Roach (dm).

Festival International de Jazz, Salle Pleyel, Paris, 15/5/1949, second concert

22. BLUES FINAL (trad.)

(Radio Transcription, Jazz Sélection/

Intégrale Sidney Bechet cof. 21 A) 5’00

Total : 71’35

«?Il faut vraiment être aveugle à l’évidence pour refuser de voir en Parker un musicien d’une envergure aussi prodigieuse que celle des plus grands des générations précédentes.?»

Boris Vian

“You really have to be blind to all the evidence if you refuse to see that Parker's calibre was at least as prodigious as that of the greatest musicians of earlier generations.”

Boris Vian

CD The Complete Charlie Parker Intégrale Charlie Parker 6 Passport 1949 © Frémeaux & Associés 2013.