- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

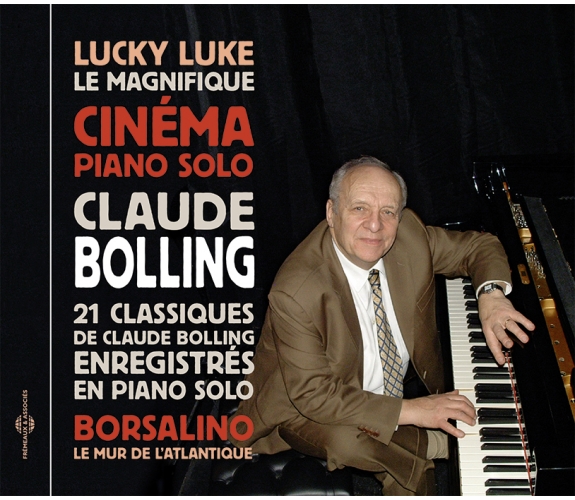

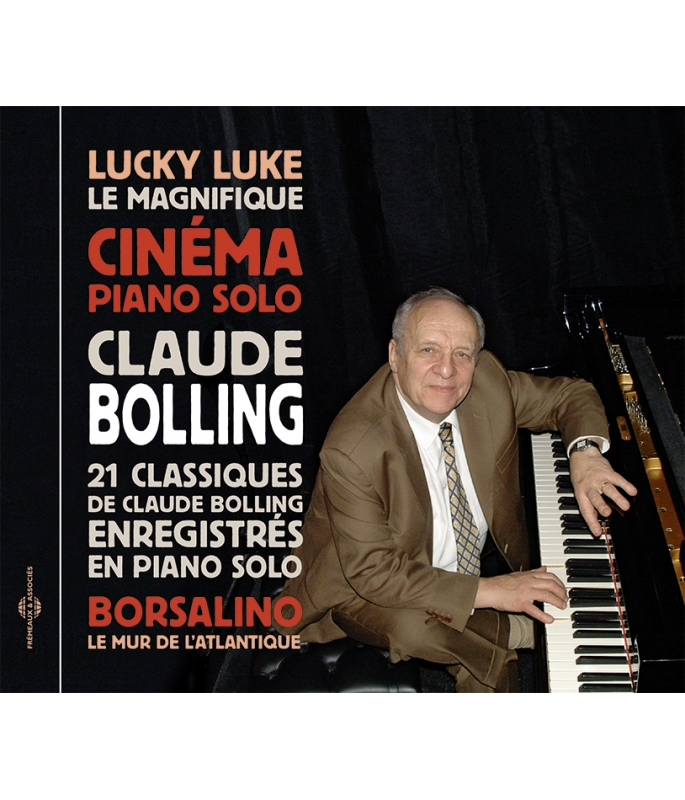

CLAUDE BOLLING(Borsalino, le magnifique...)

CLAUDE BOLLING

Ref.: FA8508

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Total duration of the pack : 1 hours 7 minutes

Nbre. CD : 1

CLAUDE BOLLING(Borsalino, le magnifique...)

CLAUDE BOLLING(Borsalino, le magnifique...)

“Music is like a small flame placed under the screen to help warm it’, said the American symphonic composer Aaron Copland, defining the role that music played in films. It’s an opinion shared by Claude Bolling, a major figure in European jazz and a man whose highly original scores have left an indelible mark on the collective memory: Borsalino, Lucky Luke, Le Magnifique, Les Brigades du Tigre… Fifty years after writing the music for his first short film, the great Bolling jumped at the idea of this retrospective, an entertaining project that would associate his twin statures as a pianist and film-composer within the same album.” Stéphane LEROUGE

Claude Bolling is the great ambassador of big-band jazz and one of the greatest film-music composers of the 20th century. He’s also the man behind the term “crossover” designating the music-genre which mixes jazz with classical music, thanks to a dozen duo records which paired Bolling with trumpeter Maurice André, guitarist Alexandre Lagoya, cellist Yo-Yo Ma or flautist Jean-Pierre Rampal... Claude Bolling’s “Suite for Flute and Piano” with Rampal remained in the U.S. sales-charts of “Billboard” magazine for more than ten years. Patrick FRÉMEAUX

CLAUDE BOLLING BIG BAND

CLAUDE BOLLING - ALAIN DELON - JACQUES DERAY

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Flic Story ThemeClaude Bolling00:03:412011

-

2Trois hommes à abattreClaude Bolling00:02:492011

-

3Prends-moi MatelotClaude BollingJean-Claude Carrière00:02:532011

-

4La réussiteClaude Bolling00:02:182011

-

5Borsalino ThemeClaude Bolling00:04:132011

-

6La Complainte des ApachesClaude Bolling00:02:202011

-

7La MandarineClaude Bolling00:04:322011

-

8Louisiana WaltzClaude Bolling00:04:542011

-

9Old New OrleansClaude Bolling00:03:592011

-

10Dors bonhommeClaude Bolling00:03:562011

-

11Far West Cho ChoClaude Bolling00:02:252011

-

12I'm a Poor Lonesome Cow BoyClaude Bolling00:03:072011

-

13Daisy Town SaloonClaude Bolling00:02:182011

-

14TatianaClaude Bolling00:02:302011

-

15RanerClaude Bolling00:03:182011

-

16ChristineClaude Bolling00:03:172011

-

17NostalgieClaude Bolling00:03:172011

-

18God Bless RugbyClaude Bolling00:03:052011

-

19Le LabyrintheClaude Bolling00:02:172011

-

20ClaudineClaude Bolling00:02:272011

-

21Fiancées en folieClaude Bolling00:03:392011

Piano solo FA8508

CLAUDE BOLLINGCINÉMA PIANO SOLO

21 CLASSIQUES DE CLAUDE BOLLING ENREGISTRÉS EN PIANO SOLO

Claude Bolling

Cinéma Piano Solo

« La musique de film est une petite flamme placée sous l’écran pour l’aider à s’embraser. » Voilà les mots avec lesquels le symphoniste américain Aaron Copland définissait le rôle de la musique à l’image. Un avis partagé par Claude Bolling, haute figure du jazz européen, dont les bandes très originales ont marqué au fer rouge la mémoire collective : Borsalino, Lucky Luke, Le Magnifique, Les Brigades du Tigre… Cinquante ans après son premier court-métrage, le grand Bolling se lance dans un projet ludique et rétrospectif, à savoir associer sur un même album son statut de pianiste à celui de compositeur pour l’image. « L’idée était simple, résume-t-il. Il s’agissait de replonger dans mon propre passé cinémato-graphique, en sélectionner plusieurs titres emblé-matiques, les relire et retraiter au piano solo. D’une certaine façon, je me suis mis à revivre une situation-clé, celle de la confrontation au cinéaste, ce moment décisif où vous lui soumettez au clavier le (ou les) thèmes potentiels de son film. Le principe de cet album, c’est donc un aller-retour. J’ai d’abord composé ces thèmes au piano, sur deux lignes. Une fois validés par le metteur en scène, je les ai orchestrés. Et aujourd’hui, des années plus tard, je les reprends dans leur version originelle. C’est une sorte de retour aux sources, à la première étape de l’écriture. »

Pendant plusieurs semaines, Claude Bolling s’est donc amusé à repenser au piano solo un large éventail de thèmes de son répertoire : souvent aisé (Claudine, Fiancées en folie, Les Brigades), l’exercice s’est parfois révélé plus acrobatique. « Pour être honnête, avoue Claude, j’ai davantage souffert sur Old New Orleans, Le Mur de l’Atlantique ou encore Trois hommes à abattre : il faut redoubler d’invention pour condenser à un clavier de piano ce que font cinquante musiciens. Le résultat fonctionne vraiment comme une réduction, pas comme une simplification. Après la réécriture est venu l’enregistrement. Je me suis retrouvé seul en studio. Quand ce n’était pas satisfaisant, je ne pouvais m’en prendre qu’à moi-même. La coopération avec d’autres musiciens m’a parfois manqué. Mais, en même temps, cette solitude a insufflé au projet une grande liberté : si nécessaire, je pouvais reprendre tel ou tel morceau, sans aucune contrainte de temps. A l’arrivée, c’est un disque conçu pour être écouté de près, une confidence, un objet intime. Comme si on me demandait de jouer mes thèmes de cinéma lors d’une soirée entre amis. » C’est aussi une façon de refaire connaissance avec des œuvres que l’on pensait connaître par cœur… et qui brillent d’un nouvel éclat, celui du dépouillement, de l’épure. Comme le soulignait Lalo Schifrin à Stravinski, après avoir découvert en concert la version piano du Sacre du printemps : « C’est une femme magnifique avec sa toilette et ses bijoux. Mais nue, elle est encore plus belle ! » L’image se confirme au gré de ce voyage libre et sensible dans le cinéma de Claude Bolling. Visite guidée en compagnie du compositeur qui, pour l’occasion, déroule le ruban de ses souvenirs.

Seven chances / Fiancées en folie (1925-1968)

Un film de et avec Buster Keaton

« Dans le domaine de la comédie, j’ai eu la chance de travailler avec des personnalités comme Philippe de Broca, René Goscinny, Pierre Tchernia. L’une de leurs références communes, c’est évidemment Buster Keaton, père du burlesque moderne. A la fin des années soixante, grâce à Jacques Robert, j’ai pu mettre en musique trois classiques de Keaton : La Croisière du Navigator, Cadet d’eau douce et… Fiancées en folie. Avec ses rebondissements incessants (au propre comme au figuré), la poursuite diabolique de Fiancées m’a imposé une composition très technique, calquée sur le mouvement, la gestuelle, la vélocité de Keaton. Très vite, Fiancées en folie s’est naturellement inscrit au programme de mes concerts de piano.

Borsalino (1970)

Un film de Jacques Deray

Avec Alain Delon, Jean-Paul Belmondo, Nicole Calfan…

C’est le film de ma double rencontre avec Jacques Deray et Alain Delon, deux hommes déterminants dans mon itinéraire cinématographique. Deray m’avait appelé avant même le premier tour de manivelle, à Marseille, en me demandant de lui faire parvenir certaines de mes compositions. Un thème lui a accroché l’oreille, Il pleut toujours quelque part, enregistré courant 1969 pour un disque de jingle-piano, appellation anglo-saxonne du piano bas-tringue. Pour dissuader Deray d’employer une œuvre préexistante, je lui ai écrit une proposition alternative, La Réussite. Sa réaction a été sans appel : « Très bien également… Je l’utiliserai… mais je garde le premier ! » [rires]. Très vite, j’ai convaincu Jacques Deray et Alain Delon d’opter pour une musique originale évoquant les années vingt-trente, plutôt que de reprendre des succès d’alors. A moi d’éviter de faire du « faux-vieux »... en étant dans l’esprit de l’époque mais avec un regard, une sensibilité d’aujourd’hui. En outre, je n’ai pas cherché à surenchérir dans la dimension sombre, inquiétante des intrigues. Au contraire, le côté spirituel de La Réussite ou du Thème Borsalino apporte une légèreté en contrepoint avec la violence des personnages ou des situations. Le succès du film et de sa bande originale auront une grande influence sur la suite de ma carrière et Alain Delon sera le comédien que j’aurai le plus l’occasion de mettre en musique.

Le Mur de l’Atlantique (1970)

Un film de Marcel Camus

Avec Bourvil, Terry-Thomas, Sophie Desmarets, Jean Poiret

C’est l’une des pièces les plus périlleuses du présent album : réduire au piano une marche anglaise, orchestrée à l’origine pour fanfare, chœur d’hommes et sifflets ! C’était ma deuxième collaboration avec Marcel Camus, autour d’une histoire scénarisée par Marcel Jullian, celle d’un résistant malgré lui incarné par le grand Bourvil, pour son ultime apparition à l’écran. Camus m’a demandé une marche de rugbymen énergique et musclée, à caractère totalement britannique, dans l’esprit du Pont de la rivière Kwaï. Je dois avouer que le texte du parolier anglais Jack Fishman m’a beaucoup aidé… Cette marche servait de fil conducteur au récit, à travers différentes variations et déclinaisons. Au départ, c’est un pur exercice de style… dont on parvient à s’échapper, notamment par l’orchestration.

Lucky Luke, Daisy Town (1971)

Un dessin animé de René Goscinny et Morris

Dès ma première lecture d’un Lucky Luke, j’ai été fasciné par cette transposition parodique du western et, en particulier, par les interventions parlées du cheval Jolly Jumper, témoin et commentateur ironi-que des aventures de son maître. J’ai lancé à ma femme, Irène : «J’ignore si on tournera un jour un film de cette BD mais, en tout cas, j’entends déjà la musique comme si j’y étais ! » Or, peu après, Irène a interviewé René Goscinny qui entamait alors avec Morris et Pierre Tchernia l’écriture de Daisy Town, le premier Lucky Luke au cinéma. Dès lors notre collaboration semblait inévitable. Lucky Luke a donc été ma première grande expérience dans le film d’animation. Pour un compositeur, le dessin animé requiert une technique particulière. Par exemple, la plupart des thèmes ont été enregistrés avant la réalisation des séquences correspondantes. J’ai composé en sachant uniquement que, de 1’14 à 1’16, les Dalton montent à cheval, à 1’17 Averell se prend les pieds dans ses étriers, à 1’20 il se mettent à galoper etc. Puis, dans un second temps, l’image a été dessinée et animée, sur le rythme de la musique, sa dynamique, ses inflexions. A l’arrivée, la partition est très éclatée au niveau esthétique. J’y lance aussi bien des clins d’œil au western hollywoodien qu’au western-spaghetti, sans compter les chansons de saloon avec piano-bastringue (Daisy Town saloon song), des thèmes de poursuite en train (Far-west choo-choo) et évidemment le fameux final, I’m a poor lonesome cow-boy, rythmiquement calqué sur le pas de Jolly Jumper. Je ne peux penser à cette aventure sans nostalgie : par son humour et sa générosité, René Goscinny a éclairé huit années de ma vie.

La Mandarine (1972)

Un film d’Edouard Molinaro

Avec Annie Girardot, Philippe Noiret, Madeleine Renaud, Murray Head

C’est ma première collaboration avec Edouard Molinaro… et notre seul long-métrage en commun. Par la suite, nous nous sommes assidûment retrouvés sur des séries télévisées. Notre rapport de confiance est tel qu’Edouard n’assistait pas forcément aux séances d’enregistrement. La Mandarine, c’est un thème romantique pour voix féminine soliste… qui fonctionne comme la voix intérieure d’Annie Girardot. Plus tard, je l’ai réutilisé et développé pour l’un des mouvements (Intime) de la Suite pour flûte No II, interprétée par mon complice, le grand flûtiste Jean-Pierre Rampal. Ce thème est né des images d’Edouard Molinaro et s’en est émancipé, jusqu’au présent album.

Le Magnifique (1973)

Un film de Philippe de Broca

Avec Jean-Paul Belmondo, Jacqueline Bisset, Vittorio Caprioli...

Ma rencontre avec Philippe de Broca s’est scellée autour du Magnifique, film de ses retrouvailles avec son comédien fétiche, Jean-Paul Belmondo. C’était une réflexion spirituelle sur les rapports entre fiction et réalité. Avec un écrivain médiocre qui transpose son quotidien dans ses romans, en prenant le visage de son héros, l’agent secret Bob Saint-Clar. Philippe avait joué sur toutes les interactions possibles entre le réel et l’imaginaire, en trouvant toujours une solution originale pour passer d’un univers à un autre. C’était aussi la mission de la musique : personnaliser chaque monde. Un pan de la partition est orienté vers l’évasion et l’exotisme, un autre vers le quotidien. Une sorte d’équilibre entre le réalisme et le rêve. Précisément, Christine et Tatiana sont deux versants, deux facettes d’un seul et même thème illustrant la dualité du personnage : Tatiana, l’espionne de charme dans l’imaginaire ; Christine, l’étudiante en sociologie dans la vraie vie. De facture romantique, Tatiana colle au caractère sensuel de la voluptueuse aventurière. Avec une forme d’exagération ironique dans les suspensions, notamment quand Belmondo saute au ralenti par-dessus la portière de sa décapotable. Cette comédie à l’humour dévastateur a désormais atteint le statut de classique.

Les Brigades du Tigre (1974-1983, TV)

Une série télévisée de Victor Vicas

Avec Jean-Claude Bouillon, Pierre Maguelon, Jean-Paul Tribout

Les Brigades du Tigre, c’est certainement l’une des séries françaises les plus abouties, avec une ambition comparable à celle des romans d’Alexandre Dumas : divertir tout en portant un regard original sur une époque. L’aventure a démarré par un coup de fil du producteur Bob Velin : « Claude, écrivez-nous quelque chose d’aussi fort que Borsalino ! » Sur la simple lecture des scénarios de Claude Desailly, j’ai donc élaboré une proposition de générique évoquant les caractères et l’époque des Brigades (Thème Valentin), aussitôt retenue par le réalisateur, Victor Vicas. Velin, lui, s’est exclamé : « Finalement, c’est encore mieux que Borsalino ! » [rires] D’ailleurs, la démarche musicale était la même que celle du film de Deray : je me suis appliqué à mettre au point une écriture moderne à l’intérieur d’un parfum rétro. S’il avait été écrit en 1907, le Thème Valentin n’aurait jamais comporté des quintes diminuées ou des septièmes majeures. Ce qui prouve une évidence : Les Brigades du Tigre, c’est d’abord un point de vue du présent sur le passé. Sincèrement, avec trente-cinq ans de recul, cette série représente un pan entier de ma vie de compositeur. Sa pérennité me fait penser à un lieu commun : contrairement au crime, la qualité paie.

Flic story (1975)

Un film de Jacques Deray

Avec Alain Delon, Jean-Louis Trintignant, Marco Perrin, André Pousse

Dès que j’ai découvert les premières images de Flic story, j’ai été frappé par la force du sujet et de son traitement : un polar sans fioritures, à la mise en scène acérée, bâti sur l’opiniâtreté de Borniche-Delon traquant impitoyablement l’ennemi public numéro un, Buisson-Trintignant. La partition reflète la grisaille du Paris pluvieux de l’après-guerre, utilisant le timbre populaire de l’accordéon, dans un registre un peu mystérieux. C’est vraiment la musique qui m’est venue spontanément à l’issue de la projection de travail… J’ai traduit au clavier les impressions que le film m’avait communiquées. Un responsable de la production a simplement relevé, non sans humour, que les trois premières notes du thème de Flic story étaient celles de Borsalino… mais à l’envers ! De mes treize partitions pour Jacques Deray, Flic story était sa préférée.

Les Passagers (1977)

Un film de Serge Leroy

Avec Jean-Louis Trintignant, Mireille Darc, Bernard Fresson

C’est mon unique collaboration avec le cinéaste Serge Leroy, autour d’un thriller sombre et nerveux. A l’époque, à cause de mes partitions pour Jacques Deray, certains décideurs m’avaient catalogué comme « le spécialiste du polar ». La relation des deux personnages (Trintignant–Darc) avec un enfant de dix ans m’a donné l’idée d’un thème en forme de berceuse… mais une berceuse qui se développe en balade nonchalante, au caractère bluesy. D’où son titre : Dors bonhomme. Par la suite, ce thème a intégré le répertoire du big band.

L’Homme en colère (1978)

Un film de Claude Pinoteau

Avec Lino Ventura, Angie Dickinson, Laurent Malet, Donald Pleasence

Claude Pinoteau est un metteur en scène très précis, très méticuleux, ancien assistant de René Clément sur Le Jour et l’heure, mon premier long-métrage avec partition symphonique. Dans L’Homme en colère, il retrouvait un ami commun, Lino Ventura, sa vedette du Silencieux et de La Gifle. Pour ma part, j’avais envie de clore ce polar non pas sur une musique à suspense mais plutôt sur un thème entêtant, en l’occurrence un trois temps, une sorte de valse lente au lyrisme étrange, avec une mélodie généreuse troublée d’harmonies qui frottent. Mais il a fallu sortir l’artillerie lourde pour vaincre les réticences de l’ami Claude, qui se braquait sur une note aigue, à la troisième phrase du thème ! Il a fini par l’admettre… et ce générique fin, Le Labyrinthe, est aujourd’hui considéré comme l’une de mes réussites pour le cinéma.

Claudine (1978, TV)

Une série télévisée d’Edouard Molinaro

Avec Marie-Hélène Breillat, Jean Desailly, Georges Marchal

Pour cette adaptation des romans de Colette par Edouard Molinaro et Danièle Thompson, il n’y avait pas mille directions possibles. Le sujet appelait obliga-toirement une valse 1900, comme un équivalent moderne à Fascination, avec les mêmes ralentis. Il fallait une sorte de fraîcheur, d’innocence qui fasse du thème un portrait de Claudine, incarnée par Marie-

Hélène Breillat. Là encore, j’explore le début du XXe siècle une époque qui est également celle des Brigades.

L’Etrange monsieur Duvallier (1979, TV)

Une série télévisée de Victor Vicas

Avec Louis Velle, Sabine Azema, Guy Grosso

C’est une série d’aventures policières que je perçois comme un prolongement moderne à mon travail avec Victor Vicas sur Les Brigades du Tigre. Au pré-générique de chaque épisode, on découvre un vieillard cacochyme, le monsieur Duvallier du titre, rejoindre un antre secret, enlever ses postiches… et prendre alors le visage de Louis Velle. Musicalement, l’introduction devait être mystérieuse, intrigante puis, à l’apparition du thème, il fallait jouer la complicité avec le téléspectateur. D’où ce côté enlevé et espiègle, collant au personnage de Raner, le gentleman-justicier. Avec Vicas, nous pensions à tort que Duvallier se développerait sur plusieurs saisons. A l’inverse, nous imaginions que Les Brigades serait une série de deux fois six épisodes… et elle a duré dix ans et trente-six épisodes ! C’est la part de hasard, d’imprévu, inhérente à notre métier.

Trois hommes à abattre (1980)

Un film de Jacques Deray

Avec Alain Delon, Dalila Di Lazzaro, Michel Auclair, Jean-Pierre Darras

Le sujet de Trois hommes à abattre (le destin qui s’empare d’un homme normal) m’a inspiré une partition qui casse le moule, qui va à l’encontre de ce que l’on peut imaginer a priori sur un thriller moderne et urbain. En l’occurrence, je me suis orienté vers une écriture à caractère néo-classique, presque mahlérienne, au lyrisme grave et douloureux. Jacques a été séduit, avec un bémol pour la fugue destiné à la séquence de poursuite automobile. Ce type de dissension est inévitable sur une collaboration aussi longue : avec Jacques, on s’est beaucoup apprécié, souvent compris, malgré deux ou trois gros orages. Il était attentif à la musique et, en même temps, elle l’effrayait : il avait le sentiment qu’un élément de mise en scène lui échappait. Mon rôle était de l’écouter, de l’accoucher… et de lui faire des propositions en conséquence.

Louisiane (1983)

Un film de Philippe de Broca

Avec Margot Kidder, Ian Charleson, Victor Lanoux, Andrea Ferreol

Dix ans après Le Magnifique, Louisiane marque le deuxième acte de ma collaboration avec Philippe de Broca. Le sujet m’enthousiasmait : depuis l’enfance, je suis passionné par l’Amérique du XIXe siècle, celle des bateaux à roue et des premiers chemins de fer. Pour moi, il y avait un vrai pari à relever : s’exprimer à travers la musique romantique de l’époque, la recréer avec ma sensibilité, sur des images de la Nouvelle-Orléans, berceau historique du jazz. A la fin du XIXe, la Louisiane vivait au son des quadrilles et valses européennes. En voyant les images de Philippe, j’ai eu envie de faire sentir et ressentir les prémices du jazz. Ecoutez par exemple Old New Orleans : rythmiquement, la “syncopation“ du jazz est déjà là. Comme un avant-goût de cette révolution musicale issue du Nouveau Monde. Quant au thème principal, Louisiana waltz, c’est une valse romantique, pour orchestre et voix, en l’occurrence celle de Dee Dee Bridgewater. L’idée était de marier une forme très européenne, très française, avec une voix noire américaine, sur un texte anglais. Une illustration symbolique de la fusion des cultures. J’ai essayé d’en retrouver l’esprit dans la version piano de ce disque, en hommage à l’ami de Broca. C’était un homme attachant et cultivé, parfois imprévisible, souvent impatient, dont la vie et les films ressemblaient à une course sans fin. Des pyramides aztèques aux rives du Mississipi, j’ai fait grâce à lui mes plus beaux voyages, réels ou imaginaires.

Le Clan (1988, TV)

Une série télévisée de Claude Barma

Avec victor Lanoux, Jeane Manson, Marie-Josée Nat, Daniel Duval

Le Clan, c’est sans doute le sommet de ma colla-boration avec Claude Barma, pionnier de la fiction télévisée. Claude était un homme très intelligent mais compliqué dans le travail : il n’était pas aisé de cerner son attente tant il avait de difficultés à exprimer l’idée qu’il se faisait de la musique… Il fallait tâtonner, creuser différentes directions et, par élimination, nous finissions par arriver au résultat. Dans Le Clan, le thème Nostalgie, c’est le versant sentimental de cette série policière, le thème d’amour entre Victor Lanoux et Jeane Manson. Polar, Marseille, ambiance rétro : une fois encore, le syndrome Borsalino me rattrapait. Il m’est arrivé de reprendre Nostalgie en concert, ce qui confirme le vieil adage : la bonne musique de film doit autant servir le film que la musique. En résumé, écrire pour l’image est un exercice passionnant. Le cinéma fonctionne comme un détonateur à idées qui m’amène à explorer des territoires que, sans le prétexte du film, je n’aurais jamais abordés. En soi, chaque film ou série représente une nouvelle gageure : le compositeur ne doit pas renoncer à sa personnalité, simplement l’ajuster à celle du metteur en scène, pour faire œuvre commune. »

Propos recueillis par Stéphane Lerouge

© Frémeaux & Associés 2014

Claude Bolling

Cinéma Piano Solo

“Music is like a small flame placed under the screen to help warm it,” said the American symphonic composer Aaron Copland, defining the role that music played in films. It’s an opinion shared by Claude Bolling, a major figure in European jazz and a man whose highly original scores have left an indelible mark on the collective memory: Borsalino, Lucky Luke, Le Magnifique, Les Brigades du Tigre… Fifty years after writing the music for his first short film, the great Bolling jumped at the idea of this retrospective, an entertaining project that would associate his twin statures as a pianist and film-composer within the same album. “It was a simple idea,” he says, “diving back into my own past in films, choosing several symbolic titles, and going over them again with a solo piano version in mind. In a way, I was reliving a key-situation: confronting a filmmaker. It’s that moment of decision when you sit down at the keyboard and play him a theme that’s potentially right for his film. So the principle behind this album is a return-visit. Originally, I composed these themes on the piano in a couple of lines; then, once the director had given his approval, I orchestrated them. And today, years later, I’m picking them up again in their original version. It’s a sort of return to the roots, to the first stages of composition.”

And so for several weeks Claude Bolling enjoyed himself, rethinking a wide range of tunes from his repertoire with a view to making a solo piano album: the choice was often easy (Claudine, Fiancées en folie, Les Brigades), but the exercise sometimes turned out to be more acro-batic. “To be honest,” confesses Claude, “doing ‘Old New Orleans’, ‘Le Mur de l’Atlantique’ or ‘Trois hommes à abattre’ caused me a lot more effort: I had to be twice as inventive in reducing a score intended for fifty musicians down to a solo keyboard-piece. And it really functions like a reduction, not a simplification. After the rewriting came the recording and I found myself all alone in the studio. If I wasn’t satisfied I only had myself to blame. Cooperating with other musicians was a thing I sometimes missed. But at the same time, that solitude breathed great freedom into the project: if necessary, I could go over a piece again and again without time being a problem. Finally, this is a record that’s meant to be listened to closely, like something confidential or an intimate object; it’s like being asked to play my film-tunes for some friends one evening.” The record is also a way for us to renew our acquaintance with tunes we thought we knew by heart... tunes that shine with a new sparkle, the brilliance associated with the sparseness of a working drawing. After hearing the piano version of Rite of Spring at a concert, Lalo Schifrin said to Stravinsky: “This woman’s magnificent in her dress with all her jewellery... but naked, she’s even more beautiful!” You get the picture when you take this free and sensitive voyage through the filmography of Claude Bolling. It’s a guided visit in the company of the composer, and this time the guide rewinds his own memories for us.

Fiancées en folie/Seven chances (1925-1968)

dir. et w. Buster Keaton

In comedy I was lucky to work with characters like Philippe de Broca, René Goscinny or Pierre Tchernia. Obviously Buster Keaton was a reference they had in common: he was the master of modern burlesque. At the end of the Sixties, thanks to Jacques Robert, I wrote the music for three Keaton classics: The Navigator, Steamboat Bill Jr. and Seven Chances, which was called Fiancées en folie in France. There were sudden new developments at every turn, both in the literal as well as the figurative sense, and the frantic chase-scenes in Fiancées imposed a very technical composing-style that exactly copied the speedy way Keaton moved and gesticulated. Seven Chances was a natural choice for my concert piano-repertoire.

Borsalino (1970)

Dir. Jacques Deray

w. Alain Delon, Jean-Paul Belmondo, Nicole Calfan…

This was the film where I met both Jacques Deray and Alain Delon, two men who were decisive in my film-career. Deray called me from Marseilles even before he started shooting, and he asked me to send him some of my compositions. One tune caught his ear, Il pleut toujours quelque part, which had been recorded at some point in 1969 for a jingle-piano record, the English name for honky-tonk. To dissuade Deray from using a piece that already existed, I wrote an alternative proposal for him, La Réussite. There was no appeal against his decision: “That’s very good, too; I’ll use it! But I’m keeping the first one!” (Laughter.) I quickly convinced Jacques and Alain Delon to opt for an original score that recalled the Twenties and Thirties, instead of using hits from the period. This meant that now I had to avoid writing fake “old music”: I had to keep to the spirit of the era, but look at it with a contemporary eye using today’s feel. Above all, I didn’t try to up the ante regarding the dark, troubling dimension of the plot; on the contrary, the tongue-in-cheek side of La Réussite or the Thème Borsalino brings a light feel that acts in counterpoint to the violence of the characters or situations. The success of the film and its original soundtrack would greatly influence the rest of my career; and Alain Delon would become the actor I most often set to music.

Le Mur de l’Atlantique/Atlantic Wall (1970)

Dir. Marcel Camus

w. Bourvil, Terry-Thomas, Sophie Desmarets, Jean Poiret

This is one of the most perilous pieces on the album: a piano reduction of an English march that was originally orchestrated for a brass band, chorus and whistles! It was the second time I’d worked with Marcel Camus, and Marcel Jullian wrote the screenplay for this story of an unwilling member of the Resistance played by the great Bourvil (his last screen role). Camus asked me for a virile march that suited a muscle-bound rugby-team, an “absolutely British” piece with a Bridge on the River Kwai feel. I have to confess that the English lyrics by Jack Fishman helped me... This march was the story’s principal motif, with different variations and declensions. It starts as a pure exercice de style… from which we manage to escape, notably in the orchestration.

Lucky Luke, Daisy Town (1971)

Dir. René Goscinny et Morris

As soon as I read a Lucky Luke comic-book I was fascinated by the way it transposed the western as a parody, and I particularly liked the comments made by his horse, Jolly Jumper, the witness who provides a running commentary on all his master’s adventures. I said to my wife Irène, “I don’t know if they’ll ever make a film of this comic-strip but I can hear the music already; I feel like I’m right there!” As it happened, Irène was a journalist and one day she went to see René Goscinny... who was just starting to get busy with Morris and Pierre Tchernia on the screenplay for Daisy Town, the first Lucky Luke story to be made into a film. It was all a coincidence, but it just seemed inevitable that we’d all work together on it! So Lucky Luke was my first great experience of a cartoon-film. For a composer, cartoons require a special technique. Most of the tunes, for example, were recorded before the corresponding scenes were filmed. So I had to compose the music knowing just that the Daltons mount their horses between 1’14” and 1’16”, that Averell gets his foot caught in the stirrups when you get to 1’17”, and at 1’20” the horse gallops off, etc. The second thing is that the scenes are drawn and animated according to the rhythm of the music, its dynamics and inflexions. In the end, the score was all over the place in the aesthetic sense. When I was composing it I also slipped in a few veiled references to both the spaghetti-westerns and the ones that came out of Hollywood, as well as writing some honky-tonk songs—Daisy Town saloon song—and tunes for the railroad chase-scenes—Far-west choo-choo—plus the famous finale, of course, I’m a poor lonesome cow-boy, where the rhythms are based on Jolly Jumper’s gait. My memories of this adventure are filled with nostalgia: René Goscinny’s humour and gene-rosity brought sunshine to eight years of my life.

La Mandarine/Sweet Deception (1972)

Dir. d’Edouard Molinaro

w. Annie Girardot, Philippe Noiret, Madeleine Renaud, Murray Head

This was the first film on which I worked with Edouard Molinaro… the only feature-film we did together, in fact. After this one, our association continued in films made for television. There was so much trust in our relationship that Edouard didn’t necessarily come down to the recording-sessions even. The tune La Mandarine is a romantic theme for a solo female voice... something like Annie Girardot’s inner voice. I used it again later, developing it for one of the movements (Intime) in my Suite pour flûte N° II for my old friend Jean-Pierre Rampal, who’s a great flautist. The tune was inspired by Edouard Molinaro’s scenes but it went on to a new lease of life in other contexts, until the present album.

Le Magnifique (1973)

Dir. Philippe de Broca

w. Jean-Paul Belmondo, Jacqueline Bisset, Vittorio Caprioli...

The film Le Magnifique put the seal on my meeting with Philippe de Broca, and it also represented his reunion with the actor Jean-Paul Belmondo, his lucky-mascot. The film was a witty reflexion on the relationship between fact and fiction: the story of a mediocre writer who translates his own mundane existence in his novels by assuming the traits of his hero, the secret agent Bob Saint-Clar. Philippe had used every possible connection between reality and the imagination, always finding an original solution to switch from one universe to the other. That was also what the music had to do: personalize each world. One section of the score has an escape/exoticism orientation, and another belongs to daily life, providing a kind of balance between realism and the dream-world. Take Christine and Tatiana: two aspects, two facets of a single theme illustrating the character’s dual personality. Tatiana is the seductive female spy in the imagination, with Christine a real-life sociology student. Tatiana is a Romantic tune that keeps to the sensual persona of the voluptuous adventuress, although there’s a kind of ironic exaggeration in the suspensions, particularly when Belmondo jumps into his convertible in slow motion. The devastating humour of this comedy has made it a movie classic.

Les Brigades du Tigre (1974-1983, TV)

Dir. Victor Vicas

w. Jean-Claude Bouillon, Pierre Maguelon, Jean-Paul Tribout

Les Brigades du Tigre is definitely one of the most accomplished series made for French television. It had as much ambition as the novels of Alexandre Dumas: the episodes were meant to entertain and, at the same time, they brought an original focus to a whole era. The Brigades adventure started with a simple phone-call from the producer, Bob Velin: he said, “Claude, write me something as strong as ‘Borsalino’!” So I read Claude Desailly’s screenplays and came up with a proposal for the main-title that recalled the characters of the Brigades era (Thème Valentin), and the series’ director Victor Vicas immediately liked it. As for Velin, his first comment was, “Well, it’s even better than ‘Borsalino’!” (Laughter.) In passing, the way I approached the music was the same as for Deray’s film: I got down to finding a writing-style that was modern inside but with a retro flavour. If it had been written in 1907, the Thème Valentin would never have had diminished fifths or major sevenths. All of which goes to show that the Brigades du Tigre series was most of all a view of the past, seen from the present. Looking at it now, with some thirty years’ hindsight, I can honestly say that the series represented a whole section of my life as a composer. The fact that it’s still remembered makes me think of a commonplace-idea: unlike crime, quality pays.

Flic story (1975)

Dir. Jacques Deray

w. Alain Delon, Jean-Louis Trintignant, Marco Perrin, André Pousse

As soon as I saw the first scene in Flic story I was struck by the solidness of its subject-matter and the way it was treated: a no-frills detective-story with very sharp directing, based on the stubborn willpower that Borniche/Delon showed when he was hunting down the N°1 public enemy, Buisson/Trintignant. The score reflected the rainy greyness of post-war Paris, using the popular tones of an accordion in a rather mysterious register. That really was the music which sprang to mind when I came out of the projection--room... For the piano, I translated the impressions that the film had given me, and someone from the production department jokingly pointed out that the first three notes of the Flic story theme were actually the same as Borsalino… but played backwards! I wrote thirteen scores for Jacques Deray but Flic story was his favourite.

Les Passagers/The Intruder (1977)

Dir. Serge Leroy

w. Jean-Louis Trintignant, Mireille Darc, Bernard Fresson

I only worked with filmmaker Serge Leroy once, and the film was a dark and edgy thriller. At the time, because of my scores for Jacques Deray, some of the powers-that-be had catalogued me as “the thriller specialist”... The relationship between the Trintignant- Mireille Darc characters and a ten-year-old child gave me the idea to write a lullaby... but the tune had to develop into a carefree ballad with a bluesy feel. Hence the “Go to sleep, little man” idea in its title, Dors bonhomme. The tune later went into my big-band’s repertoire.

L’Homme en colère/Jigsaw (1978)

Dir. Claude Pinoteau

w. Lino Ventura, Angie Dickinson, Laurent Malet, Donald Pleasence

Claude Pinoteau is a very precise film-director; he’s very meticulous, and he was René Clément’s assistant on Le Jour et l’heure, the first feature-film I did with a symphonic score. With L’Homme en colère, Pinoteau was once again working with Lino Ventura, a mutual friend who’d starred in Le Silencieux and La Gifle. I didn’t want to close this thriller using music that was filled with suspense; I wanted a giddy theme, actually in three, which was this kind of slow, strangely lyrical waltz, with a generous melody upset by grating harmonies. But I had to use some big guns to persuade Claude: my old friend Pinoteau was very reticent, and he had a thing about a shrill note in the tune’s third phrase! Anyway, he finally gave in... And today they say that this end-title, Le Labyrinthe, is one of the best things I did in films.

Claudine (1978, TV)

Dir. Edouard Molinaro

w. Marie-Hélène Breillat, Jean Desailly, Georges Marchal

There weren’t that many ways to go for this screen-adaptation of Colette’s novels by Edouard Molinaro and Danièle Thompson. The subject made a 1900’s-style waltz mandatory, like a modern equivalent to Fascination, with the same slow motions. It needed a kind of freshness and innocence to turn this theme into a portrait of Claudine, played by Marie-Hélène Breillat. This piece is another of my explorations of the early 20th century, the same era as the Brigades.

L’Etrange monsieur Duvallier (1979, TV)

Dir. Victor Vicas

w. Louis Velle, Sabine Azema, Guy Grosso

I see this detective-series as a modern extension of my work with Victor Vicas on the Brigades du Tigre. In each episode, before the main credits, viewers see an old dodderer, the Monsieur Duvallier in the title, returning to his secret lair where he takes off his disguise... to reveal the face of actor Louis Velle. The musical introduction had to be mysterious and intriguing, and when the theme for the main-title came in, there had to be some form of collusion with the viewers. So that’s where the spirited, roguish side of the tune comes from, in keeping with the character of Raner, the gentlemanly avenger of justice. Vicas and I were quite wrong when we thought that Duvallier would continue for a long time... On the other hand, we also thought that Brigades was only going to be two series of six episodes each, and in fact it lasted for ten years, thirty-six episodes in all! It just goes to show that fate, the unex-pected, is an inherent part of our business.

Trois hommes à abattre/Three Men to Kill (1980)

Dir. Jacques Deray

w. Alain Delon, Dalila Di Lazzaro, Michel Auclair, Jean-Pierre Darras

The subject of Trois hommes à abattre, destiny taking control of an ordinary man, made me think of writing a score that broke the mould: music that went against the trend of most people’s ideas on what a modern, urban thriller should be like. As a result, I chose a neo-classical style in composing the music: almost like Mahler, with serious, aching lyricism. Jacques liked the whole score, although he did show some reserve about the fugue I’d written for the car-chase. Dissension like that was inevitable in any partnership as long as ours; but Jacques and I had great respect for one another, and we always had a mutual understanding, even if there were two or three stormy moments in our relationship. Jacques was very attentive to the music, and it frightened him at the same time: he had the feeling that he was missing something in his directing. My job was to listen to him and deliver his baby... by proposing music that would do just that.

Louisiane/Louisiana (1983)

w. Philippe de Broca

w. Margot Kidder, Ian Charleson, Victor Lanoux, Andrea Ferreol

Ten years after Le Magnifique, the second act in my association with Philippe de Broca came along in the shape of Louisiana. I was very enthusiastic about the subject: I’ve had a passion for 19th century America ever since I was a child, and I love those paddle-wheel steamers and the first railroads. There was a real challenge in this for me: to express myself through the romantic music of the period, and recreate that era with my own sensibilities... all against the background of New Orleans, the historic cradle of jazz. At the end of the 19th century Louisiana was vibrating to the sound of quadrilles and European waltzes. When I saw Philippe’s film I wanted to make spectators feel what jazz was like in its infancy. Listen to Old New Orleans for example: the syncopated rhythms of jazz are already there, like a foretaste of the musical revolution that came from the New World. As for the main theme, Louisiana waltz, it’s a romantic waltz for voice and orchestra, with Dee Dee Bridgewater singing. The idea was to marry a very European form with an Afro-American voice singing English lyrics: a symbolic illustration of the fusion between these different cultures. I tried to bring back those intentions in the piano version for this record, as a tribute to my good friend de Broca. He was quite endearing; a cultivated man who was sometimes unpredictable and often impatient. His life and films resembled an endless race. I travelled from the pyramids of the Aztecs to the banks of the Mississippi with him; thanks to Philippe, it was the best voyage of my life, real or imaginary.

Le Clan (1988, TV)

Dir. Claude Barma

w. victor Lanoux, Jeane Manson, Marie-Josée Nat, Daniel Duval

Without a doubt, Le Clan was the highest point in my collaboration with Claude Barma, a pioneer in television-fiction. Claude was extremely intelligent but complicated to work with: it wasn’t easy to get a precise idea of what he wanted, because he had so much trouble explaining his own conception of music. We had to feel our way along, exploring different directions, and in the end we arrived at a result by elimination. In Le Clan, the Nostalgie tune is the sentimental side of this detective-series, the love-theme between the characters played by Victor Lanoux and Jeane Manson. Thriller, Marseilles, retro atmosphere... once again, the Borsalino syndrome had caught up with me. I’ve played Nostalgie in concerts from time to time, which confirms an old saying: good film-music should serve not only the film, but also music. Writing music for films is a thrilling exercise. A film works like a detonator for ideas, making me explore territory that I’d never have touched without the film as a pretext. Each film or serial represents a new challenge: the composer mustn’t renounce his personality, just adapt it to the director’s in order to accomplish a work in common.

Stéphane LEROUGE Adapted into English by Martin DAVIES

© FRÉMEAUX & ASSOCIÉS 2014

1. Flic Story Theme [Flic Story - 1975] (Claude BOLLING © CAID MUSIC) 3’42

2. Trois hommes à abattre [Trois hommes à abattre - 1980] (Claude BOLLING © MUSIQUES & SOLUTIONS) 2’48

3. Prends moi matelot [Borsalino - 1969] (J. Claude CARRIERE / Jacques DESRAYAUD © SONY ATV MUSIC PUBL.) 2’52

4. La réussite [Borsalino - 1969] (Claude BOLLING © SONY ATV MUSIC PUBL.) 2’16

5. Borsalino Theme [Borsalino - 1969] (Claude BOLLING © BLEU BLANC ROUGE) 4’12

6. La complainte des Apaches [Les Brigades du Tigre - 1974] (Henri DJIAN © INTERSONG / WARNER CHAPPELL) 2’19

7. La Mandarine [La Mandarine - 1972] (Claude BOLLING © CAID MUSIC) 4’32

8. Louisiana Waltz (Louisiane - 1983] (Félix LANDAU © HORTENSIA / EMI MUSIC PUBL.) 4’52

9. Old New Orleans (Louisiane - 1983] (Claude BOLLING © HORTENSIA / EMI MUSIC PUBL.) 3’58

10. Dors bonhomme [Les Passagers - 1977] (Claude BOLLING © P.E.C.F. / WARNER CHAPPELL) 3’55

11. Far West Choo Choo [Lucky Luke - 1971] (Claude BOLLING © DARGAUD MUSIC) 2’23

12. I’m a Poor Lonesome Cow Boy [Lucky Luke - 1971] (Jack FISHMAN ©DARGAUD MUSIC) 3’05

13. Daisy Town Saloon [Lucky Luke - 1971] (Nicole CROISILLE © DARGAUD MUSIC) 2’17

14. Tatiana [Le Magnifique - 1973] (Claude BOLLING © PEMA & HORTENSIA/EMI MUSIC PUBL.) 2’29

15. Raner [L’Etrange Mr Duvallier - 1979] (Claude BOLLING © EDITION DES ALOUETTES / TECHNISONOR) 3’16

16. Christine [Le Magnifique - 1973] (Claude BOLLING © PEMA & HORTENSIA/EMI MUSIC PUBL.) 3’17

17. Nostalgie [Le Clan - 1988] (Ralph BERNET © COQUELICOT & MCT/UNIVERSAL) 3’15

18. God Bless Rugby [Le Mur de l’atlantique - 1970] Jack FISHMAN © BLEU BLANC ROUGE) 3’03

19. Le Labyrinthe [L’Homme en colère - 1978] (Claude BOLLING © CAID MUSIC) 2’16

20. Claudine [Les Claudine - 1978] (Claude BOLLING © INTERSONG / WARNER CHAPPELL) 2’26

21. Fiancées en folie [Fiancées en folie / Seven Chances - 1925] (Claude BOLLING © CAID MUSIC) 3’40

Claude Bolling piano /direction / arrangements

Enregistré au Studio Cordiboy

à Cherisy entre avril et mai 2011

Ingénieur du son et mixage : Vincent Cordelette

Mastering : Didier Périer - Dip Music

Textes : Stéphane Lerouge

Traduction anglaise : Martin Davies

Photos Cinéma : Serge Darmon / Christophe L Collection

Photo Claude Bolling : S. Croisiard © Claude Bolling

Fabrication et distribution : Frémeaux & Associés

« “La musique de film est une petite flamme placée sous l’écran pour l’aider à s’embraser”. Voilà les mots avec lesquels le symphoniste américain Aaron Copland définissait le rôle de la musique à l’image. Un avis partagé par Claude Bolling, haute figure du jazz européen, dont les bandes très originales ont marqué au fer rouge la mémoire collective : Borsalino, Lucky Luke, Le Magnifique, Les Brigades du Tigre… Cinquante ans après son premier court-métrage, le grand Bolling se lance dans un projet ludique et rétrospectif, à savoir associer sur un même album son statut de pianiste à celui de compositeur pour l’image.»

Stéphane LEROUGE

Claude Bolling est le grand ambassadeur du jazz en big band et l’un des plus grands compositeurs de musique de film du XXe siècle. D’autre part, il est à l’origine du crossover (genre musical mélangeant jazz et musique classique) grâce à une dizaine de disques en duo avec le trompettiste Maurice André, le guitariste Alexandre Lagoya, le violoncelliste Yo-Yo Ma, ou encore le flûtiste Jean-Pierre Rampal, dont le « Suite pour flûte et piano » est resté classé plus de 10 ans au Billboard américain (meilleures ventes aux USA).

Patrick FRÉMEAUX

“‘Music is like a small flame placed under the screen to help warm it’, said the American symphonic composer Aaron Copland, defining the role that music played in films. It’s an opinion shared by Claude Bolling, a major figure in European jazz and a man whose highly original scores have left an indelible mark on the collective memory: Borsalino, Lucky Luke, Le Magnifique, Les Brigades du Tigre… Fifty years after writing the music for his first short film, the great Bolling jumped at the idea of this retrospective, an entertaining project that would associate his twin statures as a pianist and film-composer within the same album.” Stéphane LEROUGE

Claude Bolling is the great ambassador of big-band jazz and one of the greatest film-music composers of the 20th century. He’s also the man behind the term “crossover” designating the music-genre which mixes jazz with classical music, thanks to a dozen duo records which paired Bolling with trumpeter Maurice André, guitarist Alexandre Lagoya, cellist Yo-Yo Ma or flautist Jean-Pierre Rampal... Claude Bolling’s “Suite for Flute and Piano” with Rampal remained in the U.S. sales-charts of “Billboard” magazine for more than ten years.

Patrick FRÉMEAUX

CD Cinéma piano solo : 21 classiques de Claude Bolling enregistrés en piano solo, Claude Bolling © Frémeaux & Associés 2014.