- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

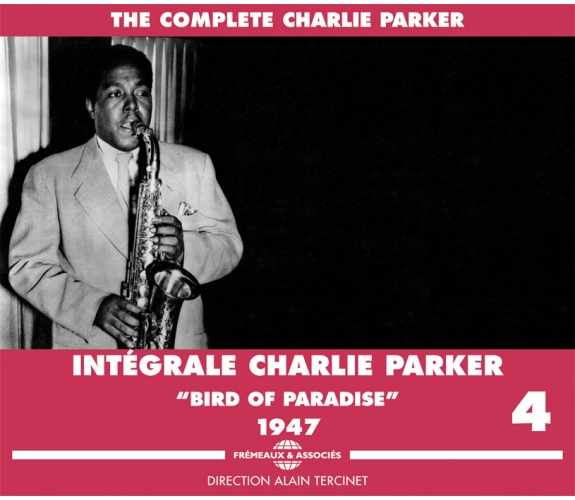

BIRD OF PARADISE - 1947

CHARLIE PARKER

Ref.: FA1334

EAN : 3561302133423

Artistic Direction : ALAIN TERCINET

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Total duration of the pack : 3 hours 27 minutes

Nbre. CD : 3

BIRD OF PARADISE - 1947

BIRD OF PARADISE - 1947

“When Charlie Parker became popular with his be-bop tunes, everybody had to change his style – the drummer, the piano player, the singer, whoever” Anita O’Day (High Times, Hard Times)

The aim of 'The Complete Charlie Parker', compiled for Frémeaux & Associés by Alain Tercinet, is to present (as far as possible) every studio-recording by Parker, together with titles featured in radio-broadcasts. Private recordings have been deliberately omitted from this selection to preserve a consistency of sound and aesthetic quality equal to the genius of this artist.

NOW'S THE TIME - 1945-1946

GROOVIN' HIGH - 1940-1945

LOVER MAN - 1946-1947

Un livre d'Alain Tercinet - Préface de Pascal...

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1MilestonesCharlie Parker00:00:101947

-

2MilestonesCharlie Parker00:02:381947

-

3MilestonesCharlie Parker00:02:471947

-

4Little Willie LeapsCharlie Parker00:00:481947

-

5Little Willie LeapsCharlie Parker00:03:121947

-

6Little Willie LeapsCharlie Parker00:02:531947

-

7Half NelsonCharlie Parker00:02:531947

-

8Half NelsonCharlie Parker00:02:461947

-

9Sippin' At BellsCharlie Parker00:00:571947

-

10Sippin' At BellsCharlie Parker00:02:241947

-

11Sippin' At BellsCharlie Parker00:00:061947

-

12Sippin' At BellsCharlie Parker00:02:311947

-

13KokoCharlie Parker00:01:101947

-

14Hot HouseCharlie Parker00:05:191947

-

15Fine And DandyCharlie ParkerSteven James00:03:311947

-

16KokoCharlie Parker00:01:101947

-

17On The Sunny Side Of The StreetCharlie ParkerDorothy Fields00:03:301947

-

18How Deep Is The OceanCharlie Parker00:03:071947

-

19Tiger Rag (O.D.J.B.)Charlie Parker00:03:551947

-

2052 Street ThemeCharlie Parker00:00:491947

-

21Night In TunisiaCharlie ParkerFranck Paparelli00:05:151947

-

22Dizzy AtmosphereCharlie Parker00:04:081947

-

23Groovin' HighCharlie Parker00:05:191947

-

24ConfirmationCharlie Parker00:05:431947

-

25KokoCharlie Parker00:04:211947

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1DexterityCharlie Parker00:02:591947

-

2DexterityCharlie Parker00:02:591947

-

3Bongo BopCharlie Parker00:02:451947

-

4Bongo BopCharlie Parker00:02:441947

-

5Prezology (Dewey Square)Charlie Parker00:03:291947

-

6Dewey SquareCharlie Parker00:03:031947

-

7Dewey SquareCharlie Parker00:03:091947

-

8The HymnCharlie Parker00:02:321947

-

9The Hymn (Superman)Charlie Parker00:02:281947

-

10Bird Of ParadiseCharlie Parker00:03:081947

-

11Bird Of ParadiseCharlie Parker00:03:101947

-

12Bird Of ParadiseCharlie Parker00:03:111947

-

13Embraceable YouCharlie Parker00:03:451947

-

14Embraceable YouCharlie Parker00:03:241947

-

15Bird Feathers (Schnourphology)Charlie Parker00:02:521947

-

16Klact-Oveeseds-TeneCharlie Parker00:03:061947

-

17Klact-Oveeseds-TeneCharlie Parker00:03:061947

-

18Scrapple From The AppleCharlie Parker00:02:431947

-

19Scrapple From The AppleCharlie Parker00:03:021947

-

20My Old FlameCharlie Parker00:03:121947

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Out Of NowhereCharlie ParkerEdward Heyman00:04:071947

-

2Out Of NowhereCharlie ParkerEdward Heyman00:03:521947

-

3Out Of NowhereCharlie ParkerEdward Heyman00:03:061947

-

4Don't Blame MeCharlie ParkerDorothy Fields00:02:501947

-

552 Street ThemeCharlie Parker00:01:421947

-

6Donna LeeCharlie Parker00:02:581947

-

7Fats FlatCharlie Parker00:02:501947

-

8Groovin' HighCharlie Parker00:03:321947

-

9Koko (C.P.) AnthropologyCharlie Parker00:06:181947

-

10Drifting On A Reed (Giant Swing)Charlie Parker00:03:011947

-

11Drifting On A ReedCharlie Parker00:02:571947

-

12Drifting On A Reed (Air Conditioning)Charlie Parker00:02:551947

-

13QuasimadoCharlie Parker00:02:581947

-

14Quasimado (Trade Winds)Charlie Parker00:02:591947

-

15Charlies WigCharlie Parker00:02:521947

-

16Charlies Wig (Bongo Bop)Charlie Parker00:02:511947

-

17Charlies WigCharlie Parker00:02:471947

-

18Bongo Beep (Dexterity)Charlie Parker00:03:031947

-

19Bongo Beep (Bird Feathers)Charlie Parker00:03:021947

-

20CrazeologyCharlie Parker00:01:021947

-

21CrazeologyCharlie Parker00:00:361947

-

22CrazeologyCharlie Parker00:03:021947

-

23CrazeologyCharlie Parker00:03:031947

-

24How Deep Is The OceanCharlie Parker00:03:261947

-

25How Deep Is The OceanCharlie Parker00:03:071947

Charlie Parker Volume 4 FA1334

THE COMPLETE Charlie Parker

INTÉGRALE Charlie Parker

Volume 4 BIRD OF PARADISE

1947

DIRECTION ALAIN TERCINET

Proposer une véritable «?intégrale?» des enregistrements laissés par Charlie Parker est actuellement impossible et le restera longtemps. Peu de musiciens ont suscité de leur vivant autant de passion. Plus d’un demi-siècle après sa disparition, des inédits sont publiés et d’autres – dûment répertoriés – le seront encore. Bon nombre d’entre eux ne contiennent que les solos de Bird car ils furent enregistrés à des fins privées par des musiciens désireux de disséquer son style. Sur le seul plan du son, ils se situent en majorité à la limite de l’audible voire du supportable. Faut-il rappeler, qu’à l’époque, leurs auteurs employaient des enregistreurs portables sur disque, des magnétophones à fil, à bande (acétate ou papier) et autres machines devenues obsolètes, engendrant des matériaux sonores fragiles??

Aucun solo joué par Charlie Parker n’est certes négligeable, toutefois en réunissant chronologiquement la quasi-intégralité de ce qu’il grava en studio et de ce qui fut diffusé à l’époque sur les ondes, il est possible d’offrir un panorama exhaustif de l’évolution stylistique de l’un des plus grands génies du jazz?; cela dans des conditions d’écoute acceptables.

Toutefois lorsque la nécessité s’en fait sentir stylistiquement parlant, la présence ponctuelle d’enregistrements privés peut s’avérer indispensable. Au mépris de la qualité sonore. Revenu à New York, Bird s’était installé au Dewey Square Hotel sur la 117ème rue Ouest en compagnie de Doris Sydnor qu’il épousera le 20 novembre 1948 à Tia Juana, durant une tournée du JATP. Après avoir répété au domicile de Teddy Reig, responsable des enregistrements chez Savoy puis à Brooklyn chez Max Roach, Parker présenta au Three Deuces durant le mois d’avril, son nouveau quintette. Le composaient Miles Davis, Duke Jordan, Tommy Potter et Max Roach?; à l’occasion d’une séance d’enregistrement pour Savoy le mois suivant, Bud Powell avait exceptionnellement remplacé Duke Jordan (cf. Charlie Parker vol. 3). Trois jours plus tôt, le 5 mai, Bird était apparu sur la scène de Carnegie Hall en compagnie, entre autres, de Roy Eldridge, Fats Navarro, Coleman Hawkins, Harry Carney, Lennie Tristano, Hank Jones et Buddy Rich. Le premier d’une série de six concerts organisés le lundi par Norman Granz grâce à qui Parker participa à beaucoup plus d’éditions du Jazz at the Philharmonic que sa discographie ne le laisse supposer. Décidément l’Oiseau était de retour, toutefois bien des choses avaient changé à New York pendant ses quinze mois d’absence.

«?La popularité du be bop avait soudainement fait un bond en avant, et mon nom s’étalait partout avec la mention de «?grand trompettiste?». Le moment était venu de remonter un grand orchestre?» raconta Dizzy dans ses mémoires. Les choses en étaient arrivées là parce que Gillespie s’était employé à en accélérer le processus. Ses années d’apprentissage dans le grand orchestre de Cab Calloway lui avaient appris que la qualité seule de la musique n’était pas garante de succès et qu’un peu de spectacle pouvait être d’une aide appréciable. D’un tempérament naturellement extraverti, Dizzy n’avait pas eu à se forcer. Avec la meilleure grâce du monde, il se prêtait au jeu, multipliant gags et mimiques en dirigeant sa formation. Béret vissé sur la tête, mouche sous la lèvre inférieure, une paire de grosses lunettes à monture d’écaille, il était devenu le modèle à imiter pour avoir l’air «?dans le coup?» et un sujet en or pour les journalistes en mal de copie. Il n’avait pas hésité à patronner une marque de «?lunettes Be Bop?» ainsi qu’une ligne de vêtements «?in?» confectionnés par la firme Fox Brothers. Toutes choses parfaitement superfétatoires aux yeux de Parker qui considérait que «?les manteaux en léopard et de chapeaux excentriques faisaient seulement partie du boulot habituel d’un manager pour faire grimper son client au box-office (1).?»

À son retour, un beau soir d’avril, Bird avait fendu la foule du Savoy Ballroom saxophone en main, pour rejoindre Gillespie qui s’y produisait à la tête de son grand orchestre. Les deux anciens partenaires ne s’étaient pas vus depuis plus d’un an… Exclamations de joie, embrassades, néanmoins rien ne serait plus pareil entre eux.

Lorsque Bird vint dans le Bronx, au McKinley Theatre, se joindre à la formation de Dizzy, les choses se passèrent fort mal. Selon Miles, Parker aurait refusé de jouer en section, alors que l’arrangeur Walter Gil Fuller prétendra qu’en état de manque, il était incapable d’émettre la moindre note. Toujours est-il que Dizzy, exaspéré, explosa : «?Fichez-moi dehors cet enfoiré?!?» Pas rancunier Bird retourna rendre visite au grand orchestre de Gillespie en août ou septembre au Pershing Ballroom de Chicago?; une rencontre probablement liée à un engagement concomitant du quintette de Parker dans la ville puisque Miles Davis fut aussi de la fête.

Teddy Reig : «?Miles était prêt. Il faut lui rendre justice, il n’avait pas la vie facile en travaillant avec Bird et, vraiment, on lui devait cette séance en raison de toutes les avanies qu’il subissait (2)?». Miles n’avait nullement l’intention de patronner une séance qui serait une variante plus ou moins réussie des sessions signées par Bird. Prenant son rôle très au sérieux, il planifia deux séances de répétitions aux studios Nola sur Broadway afin de mettre au point les arrangements basés sur quatre de ses compositions, Milestones (sans rapport avec la composition éponyme qu’il enregistrera avec Coltrane une dizaine d’années plus tard), Little Willie Leaps extrapolé de All God’s Chillun Got Rhythm, Half Nelson proche parent du Lady Bird de Tadd Dameron et Sippin’ at Bell’s.

Parker, exceptionnellement, jouerait du ténor, Max Roach tiendrait la batterie et le poste de bassiste reviendrait à Nelson Boyd, pour l’heure partenaire du pianiste-arrangeur-compositeur Tadd Dameron que Miles appréciait fort, devant le piano prendrait place John Lewis. Aux yeux du trompettiste, un indispensable partenaire en raison de son approche réfléchie de la musique. Possédant de sérieuses connaissances théoriques, il est plus que probable que John Lewis ait assisté Miles pour l’écriture des arrangements.

À son habitude, Parker arriva aux répétitions sans instrument, en empruntant un au tout dernier moment à un certain Warren Luckey. Jugeant les compositions de Miles inutilement compliquées, il prévint Lewis à propos de Milestones «?John, je ne peux pas jouer ça – trop de changements allant beaucoup trop vite. Je jouerai juste le pont (3).?» Il faut préciser à sa décharge que Bird n’aimait guère le ténor?; sur sa réserve au début de la séance, il finira par se prendre au jeu.

Ian Carr : «?Fortement marqué par la personnalité de Miles, l’enregistrement est tout à fait différent de ceux que dirige Parker?; cela est particulièrement sensible à travers une nonchalance, une détente accentuée des thèmes et de leur traitement. Le son plus coulant tient en partie à l’utilisation du saxophone ténor mais l’essence même de cette musicalité puise bien plus loin ses origines. L’esprit aérien de Lester Young plane sur cette musique (4).?» Phil Schaap : «?Ce fut aussi une des premières fois où les «?masters?» furent choisis parmi les premières prises. Jusque-là les producteurs avaient tendance à privilégier les dernières pour des raisons évidentes : elles étaient plus au point, ce qui justifiait les prises additionnelles. Vernon, son frère, me l’a confirmé. Miles choisit parmi les premières, jugeant qu’elles reflétaient mieux l’énergie et l’enthousiasme. Par la suite, les reprises ne faisaient que raboter ces qualités qui rendaient unique un enregistrement (5).?»

Dans le cadre d’une émission intitulée «?Bands for Bonds?», destinée à promouvoir la vente des Bons du Trésor auprès des auditeurs américains, fut diffusée le 13 septembre une première bataille d’orchestres mettant aux prises «?Traditionalistes?» et «?Modernistes?». Barry Ulanov, rédacteur en chef de la revue Metronome qui venait de publier un article consacré à Charlie Parker, avait mis à contribution Rudi Blesh pour qui le jazz avait atteint son apogée en… 1926. Il produisait une série d’émissions intitulées «?This Is Jazz?» durant lesquelles intervenaient les «?Rudi Blesh’s All Stars Stompers?» qui regroupait quelques valeureux représentants du jazz traditionnel. Tous acceptèrent volontiers de faire quelques heures supplémentaires ce jour-là afin de participer à l’émission diffusée juste après «?This Is Jazz?». Wild Bill Davis, Jimmy Archey, Edmond Hall, Ralph Sutton, Danny Barker, Pops Foster et Baby Dodds jouérent Sensation Rag, Save It Pretty Mama et That’s a plenty. Gillespie, Parker, John La Porta, Lennie Tristano, Billy Bauer, Ray Brown et Max Roach répliquèrent avec Koko, Hot House – Bird s’y surpasse - et Fine and Dandy. Chacune des formations avait interprété son répertoire propre. Lors de la seconde manche, les deux orchestres devaient s’affronter plus ou moins au débotté sur les mêmes thèmes. En fait, Tiger Rag constitua le seul terrain de duel - les «?Rudi Blesh’s All Stars Stompers?» n’eurent sans doute point envie de servir de précurseurs à l’«?Anachronic Jazz Band». Les boppers prirent un malin plaisir à servir Shaw ‘Nuff en introduction de Tiger Rag qu’ils achevèrent avec Dizzy Atmosphere. Pris selon la tradition sur un tempo d’enfer, le dit Tiger Rag donne à entendre un Parker survolté, prêt à toutes les audaces, aiguillonné par la section rythmique emmenée par Lennie Tristano avec lequel il entretenait une indiscutable complicité. On the Sunny Side of the Street en donne une idée, Parker inscrivant sans effort ses improvisations dans les structures harmoniques complexes nées sous les doigts du pianiste.

Pendant un mois, les auditeurs devaient voter pour élire les vainqueurs de la confrontation. Les Modernistes qui avaient remporté la palme furent conviés à célébrer sur les ondes leur victoire au début du mois de novembre. Seulement Dizzy, Ray Brown et Max Roach n’étaient plus disponibles. Fats Navarro, Tommy Potter, Buddy Rich les remplacèrent, invitant en sus le saxophoniste ténor Allen Eager. Bird ne travailla jamais de façon régulière avec Fats Navarro, ce qu’il y a lieu de déplorer à l’écoute de Koko, chef-d’œuvre de cette ultime séance radiophonique. Si Parker prend pour l’occasion un chorus d’anthologie, Fats Navarro lui succède en se tenant au même niveau. Il s’agit malheureusement de la seule interprétation au cours de laquelle Bird et Fats dialoguent car chacun des autres morceaux était destiné à mettre en valeur l’un des membres de l’équipe vainqueur. Sur Fats Flat, Parker ne se fait entendre que durant les huit dernières mesures et dans Groovin’High, il ne figure que dans les ensembles?; la qualité du jeu de Fats Navarro sur le premier morceau et le talent d’Allen Eager mis en valeur sur le second justifient l’inclusion de ces morceaux.

Entre le match et le tour d’honneur des «?Barry Ulanov’s All Stars?», Bird et Dizzy Gillespie s’étaient rencontré une nouvelle fois à Town Hall le 31 mai dans le cadre du concert «?Salute to Negro Veterans?». Une prestation qui n’a pas laissé de trace, ce qui ne fut fort heureusement pas le cas à Carnegie Hall quatre mois plus tard.

À l’affiche en première partie, le grand orchestre de Dizzy avec, en invitée, Ella Fitzgerald?; après l’entracte, le quintette Parker-Gillespie. Tout avait été loué à l’avance, des sièges les plus chers - $ 3.60 – aux moins onéreux - $ 1.00. Il ne restait guère que des places debout. Divisés en deux camps, dans un état d’excitation indescriptible, les spectateurs brandissaient des pancartes célébrant les unes les mérites de Dizzy, les autres celles de Bird. Qui, à son habitude, manquait à l’appel. Après avoir revendu à la sauvette ses billets de faveur pour payer un dealer, il avait disparu. D’après Teddy Reig, on le retrouva dans sa baignoire dont il fallut l’extirper, le sécher avant de l’habiller et le mettre dans un taxi. Après lui avoir mis entre les mains son alto, il ne restait plus qu’à le propulser sur scène. Une suite de péripéties qui ne sembla pas troubler le moins du monde Bird.

Dès l’exposé de A Night in Tunisia, il entendait bien prouver au public qu’il restait le meilleur?; avec la reprise de son fameux break saluée par les acclamations de la foule, il atteignit son but. Bien évidemment Dizzy n’entendait pas s’en laisser conter. Pris sur des tempos insensés, Dizzy Atmosphere puis Groovin’ High servirent de prétextes à une suite d’unissons et de solos étourdissants. Et Dizzy ne pût s’empêcher de ponctuer d’exclamations admiratives les chorus de Bird sur Confirmation et Koko.

À Carnegie Hall, l’association-phare du be bop montrait qu’elle n’avait rien perdu de son éclat. Parker s’était à nouveau imposé aux yeux du public new-yorkais. À la tête de son quintette, il pouvait maintenant poursuivre tranquillement l’itinéraire qu’il avait amorcé.

Entre octobre et décembre, Parker solda ses obligations envers le label Dial. Trois séances au cours desquelles un certain nombre de chefs-d’œuvre furent gravés. Embraceable You, Don’t Blame Me réalisé en une seule prise, How Deep Is the Ocean, Out of Nowhere représenteront la quintessence de ces réappropriations de standards pratiquées par Parker qui n’hésitait pas à les détrousser pour n’en conserver que la trame harmonique. Ross Russell : «?Au long des séances dans lesquelles il était partie prenante, Bird était toujours le directeur musical… Il était dans ses habitudes de continuer à enregistrer un même morceau jusqu’à ce que le résultat soit irréprochable sur tous les plans, ce qui d’ordinaire arrivait à la dernière prise. Naturellement celles qui étaient rejetées l’étaient le plus souvent en raison de fautes venant de ses partenaires (6).?»

Un témoignage qui confirmait le credo de Bird en matière d’enregistrement?: «?Il s’agit seulement de jouer proprement et de trouver les plus jolies notes?». En revanche, comme le fait remarquer Brian Priestley, il justifiait aussi la publication systématique de toutes les prises gravées par Bird. Ce que ce dernier n’aurait certainement pas approuvé, non plus d’ailleurs que la divulgation de la plupart des «?enregistrements privés?». Certes, mais l’on se souviendra que, fort heureusement, Max Brod, l’exécuteur testamentaire de Kafka, se refusa à détruire l’ensemble des œuvres et manuscrits de ce dernier ainsi que celà lui avait été imposé. Sans Dean Benedetti qui poursuivit un temps à New York ses activités d’archiviste parkérien, et quelques autres, l’incroyable prodigalité musicale de Bird resterait du domaine de la tradition orale. Le seul regret tient à ce que ces enregistrements ont été réalisés dans des conditions telles qu’un grand nombre frôlent l’inaudible. Il en est tout autrement des prises alternées malgré certains défauts sonores mineurs.

Les rejeter nous aurait privé, lors de la séance du 28 octobre, de deux versions de Bird of Paradise d’une qualité équivalente à celle du «?master?». Un même constat s’applique aux deux versions d’Embraceable You au sujet duquel Martin Williams écrivait, en parlant du modus operandi de Parker?: «?il illustre un genre d’organisation et de développement qui dépasse de loin l’écriture d’une chanson populaire. Il instaure une base compositionnelle qu’un compositeur mettrait des heures à construire de son propre chef. Parker, simplement, se lève et improvise un chorus. Et peu de temps après, durant la même séance, il se lève à nouveau et interprète un autre chorus sur le même morceau, entièrement différent du point de vue de la construction et qui, sans être tout à fait un chef-d’œuvre comme le premier, constitue néanmoins une improvisation exceptionnelle (7).?» Autres découvertes dues aux «?alternate takes?»?: lors de la première prise de Dewey Square, Bird prend deux chorus ce qui rend le morceau trop long pour un 78 t?; il n’en prendra donc plus qu’un par la suite. La même aventure se produisit à l’occasion des deux premières prises d’Out of Nowhere avoisinant les quatre minutes.

Pour sa dernière séance Dial, Ross Russell suggéra à Parker d’inviter J.J. Johnson à se joindre au quintette. «?Je me suis toujours intéressé au trombone et j’estimais que J.J. Johnson était le meilleur. J’aimais la perspective de le faire participer à une séance et Bird trouva que c’était une très bonne idée (8).?» Un ajout particulièrement bien venu car, malgré les difficultés inhérentes à un tel projet, J.J. avait réussi à transposer sur son instrument le langage bop.

Jamais encore un tromboniste ne s’était exprimé avec une semblable vélocité mise au service d’un langage usant d’une belle audace harmonique. À la seule écoute de ses disques, certains musiciens refusaient même de croire que J.J. utilisait un trombone à coulisse et non un trombone à pistons… Quasimado, Crazeology, Bongo Beep justifient largement l’intérêt que Bird manifesta à la présence de J.J. Johnson. Même si pour cela il avait fallu répéter, ce qu’il détestait.

Cette séance fut la dernière que Parker enregistra sous la houlette de Ross Russell. Leur association n’avait pas été sans nuages – la publication de la «?séance Lover Man?» (voir vol. 3) avait profondément choqué Bird -, toutefois elle fut à l’origine de quelques-unes des plus magistrales improvisations d’un génie avec lequel il n’était pas toujours facile de travailler. Indira Russell, alors l’épouse de Ross?: «?Nous étions à Los Angeles dans un ascenseur qui nous menait sur les lieux d’une séance d’enregistrement pour Dial, lorsqu’il (Parker) remarqua trois notes de musique imprimées sur la cravate de l’un des accompagnateurs de l’orchestre. Durant toute la première heure – la location du studio revenait à $ 1 000 de l’heure -, il s’amusa avec ces trois notes, à l’exclusion de toute autre. La seconde heure, tout rentra dans l’ordre. Nous avons fait un excellent disque. Bird joua magnifiquement (9).?»

Alain Tercinet

© Frémeaux & Associés 2012

(1) Ron Frankl, «?Charlie Parker?», Chelsea House Publishers, NYC, 1993.

(2) Jack Chambers, «?Milestones 1 – The music and Times of Miles Davis to 1960?», University of Toronto Press, 1983.

(3) Gary Giddins, «?Celebrating Bird – Le triomphe de Charlie Parker?», trad. Alain-Pierre Guilhon, Denoël, 1988.

(4) Ian Carr, «?Miles Davis?», trad. Catherine Collins, Coll. Epistrophy, Parenthèses, Marseille, 1991.

(5) Phil Schaap, Jazz Wax, 25 août 2010 – Internet.

(6) notes de pochette de «?Charlie Parker on Dial – The Complete Sessions?», Spotlite SPJ-CD 4-101.

(7) Martin Williams, «?The Jazz Tradition?», Oxford University Press, NYC, 1983

(8) comme (2).

(9) John Detro, «?JazzTimes Historical Notes : Bird’s Dial Sessions?», JazzTimes, janvier 1989.

BIRD Vol. 4 NOTES DISCOGRAPHIQUES

MILES DAVIS ALL STARS

Les déclarations de Phil Schaap jettent un doute sur la numérotation des prises chez Savoy. Certaines discographies mentionnent sous le titre de Wailin’ Willie une hypothétique 4ème prise de Little Willie Leaps. Il s’agit en fait de la prise 3 rebaptisée ainsi sur Savoy XP 8098 et MG 9034.

BARRY ULANOV’S ALL STAR MODERN JAZZ MUSICIANS

Plusieurs titres ont été enregistrés sans la participation de Charlie Parker?:

I SURRENDER DEAR (Lennie Tristano + rythm.) – 13/9/1947

EVERYTHING IS YOURS (Sarah Vaughan + rythm.) – 8/11/1947

DON’T BLAME ME (Tristano/Bauer/Potter) – 8/11/1947

TEA FOR TWO (LaPorta + rythm.) – 8/11/1947

SESSIONS DIAL

Il existe quantité d’erreurs - trop nombreuses pour être relevées ici - dans l’intitulé des prises d’un même morceau selon les éditions et rééditions successives. Edward M. Komara dans son ouvrage «?The Dial Recordings of Charlie Parker – A Discography?» en fait le recensement complet.

ENREGISTREMENTS PRIVÉS HORS SÉLECTION

Charlie Parker fut enregistré à New York en compagnie d’Allen Eager dans l’atelier du photographe Milton H. Greene au mois de septembre 1947. Trois titres SWAPPING HORNS, ALL THE THINGS YOU ARE, ORIGINAL HORNS figurent sur le le CD «?Allen Eager In the Land of Oo-Bla-Dee?» (Uptown 27. 49).

La rencontre entre Charlie Parker et le grand orchestre de Dizzy Gillespie à Chicago a donné lieu à plusieurs enregistrements amateurs pratiquement inaudibles (ce qui n’a pas empêché leur publication). Une fois de plus ne furent captés que les solos de Bird ce qui, dans un tel cas, n’offre qu’un intérêt limité.

THE COMPLETE CHARLIE PARKER

STUDIO & RADIO VOLUME 4

When he went back to New York, Bird moved into the Dewey Square Hotel on West 117th Street together with Doris Sydnor (they married in Tijuana on November 20th 1948, during a JATP tour). After rehearsing at Teddy Reig’s home (Reig had been in charge of Savoy’s recordings) and then with Max Roach in Brooklyn, Parker took his new quintet into the Three Deuces in April: with him were Miles Davis, Duke Jordan, Tommy Potter and Max Roach (Bud Powell stood in for Duke Jordan once, on a Savoy session held the following month; cf. Charlie Parker vol. 3). Three days earlier (May 5th), Bird had appeared onstage at Carnegie Hall with Roy Eldridge, Fats Navarro, Coleman Hawkins, Harry Carney, Lennie Tristano, Hank Jones, Buddy Rich and others, for the first in a series of six Monday concerts organised by Norman Granz, thanks to whom Parker was present at a good few more JATP gigs than his discography would lead you to believe. There was no doubt about it: the Bird was back, although a lot of things had changed in New York during his absence.

«Bebop took a great leap to popularity. My name hit the billboards as a great trumpeter before I knew it – and they had me getting ready to organize another big band,» wrote Dizzy in his memoirs. Things had gone that far because Gillespie had made sure they would; he busily accelerated their momentum: years of training with Cab Calloway’s big band had taught him that the quality of the music alone was no guarantee of success, and that a little showmanship could work wonders. As a natural extrovert, Dizzy didn’t have to work hard at that either: doing gags and impersonations while leading his band, it suited him down to the ground, and when he screwed his beret onto his head and donned a large pair of horn-rimmed glasses, he became the perfect model to imitate (if you wanted to be hip), and great copy for journalists (whatever else they had to write). Dizzy even sponsored a brand of «Be Bop» spectacles, not to mention his good work for Fox Bros. Tailors (he wore their suits). Parker, of course, thought it all supererogatory – but maybe not using exactly that word – because «leopard-skin coats and eccentric hats were just part of the job for managers wanting to push their clients at the box-office.»(1)

When Bird, clutching his saxophone, carved his way through the crowd in the Savoy Ballroom that April – he was on his way to join Gillespie, already inside with his big-band – he hadn’t seen Dizzy for more than a year. There were shouts of joy and bear-hugs, but things wouldn’t ever be quite the same between them again. It all went very badly, in fact, when Bird walked into the McKinley Theater in the Bronx to join Dizzy. According to Miles, Parker supposedly refused to play with the reeds, and arranger Walter Gil Fuller’s version was that Bird couldn’t squeeze a note out of his horn because he was in withdrawal. Dizzy, exasperated, just blew up, saying «Get that muthafucka off my stage!» Never one to bear a grudge, Bird paid another visit to the orchestra (August or September) at the Pershing Ballroom in Chicago, no doubt due to the fact that his own quintet also had a gig in town (Miles went over there with Bird, presumably anxious not to miss out on anything).

Teddy Reig: «Miles was ready. Give Miles credit, he had to put up with a lot working with Bird and really, like, we owed him this date because of all the shit he took.» (2) Miles had no intention of lending his name to a session that would be just a more-or-less satisfactory variation on the sessions done by Bird. Taking his role very seriously, he planned two rehearsals at the Nola studios on Broadway in order to fine-tune some arrangements based on four of his own compositions: Milestones (no relationship to the piece with the same name he recorded a decade later with Coltrane), Little Willie Leaps (an extrapolation of All God’s Chillun Got Rhythm), Half Nelson (a close cousin of Tadd Dameron’s Lady Bird), and Sippin’ at Bell’s.

Parker, for once, was to play tenor; Max Roach was the drummer, the bassist was Nelson Boyd, at the time one of pianist/arranger/composer Tadd Dameron’s partners (Miles was very appreciative), and stepping up to the piano was John Lewis. For the trumpeter, Lewis’ thoughtful approach to music made him an indispensable partner; given his solid theoretical skills, it’s more than likely that Lewis assisted Miles in writing the arrangements. As usual, Parker turned up for rehearsals without an instrument, borrowing one at the last minute from a certain Warren Luckey. He thought Miles’ compositions were needlessly complicated, and when they came to Milestones Bird said to Lewis, «John, I can’t play this – too many changes going by too fast. I’ll just play the bridge.» (3) In his defence it can be said that Bird didn’t care much for playing tenor; but whatever his reticence at the beginning of the session, he finally got into it.

According to Ian Carr, «The most striking feature of this session is the way Miles has imposed his own personality on it. The music is unlike Parker’s own recordings in that the themes and the way they are played are much more relaxed and laid-back. The use of the tenor sax may have something to do with the smoother sound of the ensemble, but the essence of the music goes deeper than that. The liquid spirit of Lester Young hangs over it.» (4) In Phil Schaap’s view, «It’s also one of the first times earlier-take numbers were chosen as the masters. Previously, producers tended to choose later takes for obvious reasons. They were more perfect, which is why additional takes were requested in the first place. Here, Miles picked the early takes. Vernon Davis, Miles’ brother, confirmed that for me. Miles felt earlier takes had the right energy and excitement, and that later takes only polished the edge off what made the recording special.» (5)

To boost sales of the U.S. Government’s Treasury Bonds, there was a radio show called «Bands for Bonds», and September 13th saw the staging of the first «battle» between «Traditionalists» and «Modernists». Barry Ulanov, the editor of Metronome magazine – it had just published a Charlie Parker feature – had solicited assistance from Rudi Blesh, a critic and enthusiast, and also someone for whom jazz had already reached its zenith by 1926… Blesh was producing a series of shows entitled «This Is Jazz», with contributions from «Rudi Blesh’s All Stars Stompers», a group made up of few valorous traditional-jazz stalwarts. And all of them agreed to a few hours overtime in order to play on a show that would air on the same day as «This Is Jazz». Wild Bill Davis, Jimmy Archey, Edmond Hall, Ralph Sutton, Danny Barker, Pops Foster and Baby Dodds played Sensation Rag, Save It Pretty Mama and That’s a plenty. Gillespie, Parker, John LaPorta, Lennie Tristano, Billy Bauer, Ray Brown and Max Roach riposted with Koko, Hot House – Bird surpasses himself on it – and Fine and Dandy. So in Round One each band played its own repertoire. In the second round, the two orchestras were supposed to face each other again, only this time playing the same tunes off the cuff. Tiger Rag turned out to be their only duel, probably because «Rudi Blesh’s All Stars Stompers» had little inclination to be an «Anachronic Jazz Band» before its time…. The boppers delighted in serving up Shaw ‘Nuff as an introduction to Tiger Rag, and then they finished off with Dizzy Atmosphere. Taken at breakneck speed – as was customary – Tiger Rag lets you hear a souped-up, totally-wired Parker ready for anything which has the slightest hint of daring to it, spurred on by the rhythm section led by Lennie Tristano (whose complicity with Parker was never questioned). On the Sunny Side of the Street gives you some idea of what was going on between them, with Parker effortlessly placing his improvisations inside the complex harmonic structures springing from beneath Tristano’s nimble fingers.

Listeners had a month to cast their votes to designate the winner; the Modernists walked away with the laurels, and were invited to celebrate their victory on the air at the beginning of November. There was just one problem: Dizzy, Ray Brown and Max Roach were no longer available to play. They were replaced by Fats Navarro, Tommy Potter and Buddy Rich, with an additional invitation sent out to tenor saxophonist Allen Eager. Bird never worked regularly with Fats Navarro, which makes you want to cry when you listen to what they do to Koko, the masterpiece which came from that ultimate radio session: Parker’s solo is a classic, and then Fats Navarro plays one like it without batting an eyelid. Unfortunately it’s the only piece where Bird and Fats have a conversation, because all the other tunes were features for the members of the winning team. On Fats Flat, Parker only makes himself heard during the last eight bars, and in Groovin’High he only appears in the ensemble-playing; the quality of Fats Navarro’s playing on the first, and Allen Eager’s talent on the second, are more than enough reason to justify their inclusion here.

Between the match and the lap of honour for «Barry Ulanov’s All Stars», Bird and Dizzy had met each other again – at Town Hall on May 31st – for the «Salute to Negro Veterans» concert, an appearance which hasn’t left a trace. Fortunately for us, this wasn’t the case when they appeared at Carnegie Hall four months later.

On the first half of the bill was Dizzy’s big-band with guest Ella Fitzgerald; after the intermission came the Parker-Gillespie quintet. All the seats were sold well in advance, with the best fetching $3.50 a pop and the least expensive at a buck each. The rest was standing-room only. Divided into two camps – both indescribably excited – the spectators were waving signs that vaunted the merits of either Dizzy or Bird, depending on the camp in which the sign was being waved. Bird, as usual, was missing. He’d disappeared into thin air after selling his complimentary tickets in order to pay a dealer. According to Teddy Reig, they found Bird in his bath-tub, from which they had to extricate him and then towel him dry before they could dress him and insert him into a cab. After that, once someone had put his alto into his hand, all they had to do was push him out onto the stage. The chain of events didn’t bother Bird in the least: right from the statement of A Night in Tunisia, Parker sounds as though he wants to prove he’s still the best; and once the audience starts applauding his reprise of that famous break, you know he really is still the best. Dizzy, of course, has no intention of letting Bird steal his thunder: Dizzy Atmosphere and Groovin’ High are taken at a furious clip, and they’re pretexts for a whole series of stunning solos and unison-passages. Nor can Dizzy help himself punctuating Bird’s choruses with shouts of admiration in Confirmation and Koko.

At Carnegie Hall, bebop’s most emblematic partners showed they’d lost none of their shine. Parker put another seal on his reputation with the New York public, and now, fronting his own quintet, he could calmly continue down the path he’d taken.

Between October and December, Parker settled his contractual obligations with Dial in the course of three sessions which resulted in a certain number of, yes, masterpieces. Embraceable You, Don’t Blame Me (done in a single take), How Deep Is the Ocean and Out of Nowhere represented the quintessence of Parker’s re-appropriations of standards, and Bird showed no qualms in stripping them of everything except their harmonic structure. According to Ross Russell, «On sessions involving Charlie Parker, Bird was always musical director…It was his custom to continue recording until the overall performance was satisfactory, and this usually happened on the final take of each number. However, the reason for rejecting earlier takes more often than not lay in defects of performances by sidemen.» (6)

What Russell said came to confirm Bird’s credo in the studios – «It’s playing clean and looking for the pretty notes» – but, as Brian Priestley pointed out, Russell used it to justify (systematically) issuing every take recorded by Bird. Parker certainly wouldn’t have approved, no more than he would have liked the disclosure of most of the «private recordings» that were made. But then you also have to remember that Max Brod, the executor of Franz Kafka’s will, refused to burn the writings and manuscripts and published them instead... So, without Dean Benedetti – whose N.Y. activities included Parker’s archives for a time – and a few others, Bird’s incredible musical profusion would have remained an oral tradition: something people might only describe to, rather than play for, others later... The only regret to be had is that these «private» recordings were often made in such conditions that many were almost inaudible; but that’s not the case with the alternate takes, despite a few minor sound-defects. Returning to that October 28th session, if Parker’s alternate takes had been discarded we’d have been deprived of two versions of Bird of Paradise whose quality is just as good as that of a «master take». The same goes for the two versions of Embraceable You, as Martin Williams noted when writing about Bird’s «modus operandi»: «It represents a kind of organization and development quite beyond popular song writing. It fulfills the sort of compositional premise which a composer might take hours to work out on his own. But Parker simply stood up and improvised the chorus. And a few moments later, at the same recording session, he stood up and played another chorus in the same piece, quite differently organized and, if not quite a masterpiece like the first, an exceptional improvisation nevertheless.» (7) These «alternate takes» allow for other discoveries: on the first take of Dewey Square, Bird plays two choruses, resulting in the piece being too long to fit on a single 78; so later, Bird took only one chorus. Idem the first two takes of Out of Nowhere: each adventure lasts for four minutes.

When the time came for Bird’s last Dial session, Ross Russell suggested that Parker might invite J. J. Johnson to join his quintet: «I was always interested in the trombone, and I thought that J. J. Johnson was just the end. I liked the idea of getting him into a date, and Bird thought it was a pretty good idea.» (8) The extra musician was all the more welcome, as Johnson had succeeded – despite the difficulties inherent in the task – in transposing the language of bop to his trombone. Until then, no trombonist had ever expressed himself with such velocity in a discourse featuring such wonderfully daring harmonies. On hearing his records, some musicians even refused to believe J. J. was playing a slide trombone rather than a valve trombone... Quasimado, Crazeology and Bongo Beep more than justified the interest that Bird showed in having Johnson join his group, even though he’d been obliged to rehearse... which he detested. That session was the last one Parker did for Ross Russell. It hadn’t all been sunny during their association – the release of the «Lover Man» session (cf. Vol. 3) had deeply shocked Bird – but among its fruits were some of the most masterful improvisations played by a genius, albeit a man who wasn’t always easy to work with: according to Indira Russell, who was then married to Ross, «We were in an L.A. elevator, heading up to one of the Dial sessions, when he noticed three musical notes on the necktie of a boy who followed the bands. The first hour, at $1000 per hour for studio rental, he insisted on fooling with those three notes. No others. The second hour, it all fell together for him. We made a good record. Bird played brilliantly.» (9)

Adapted by Martin Davies

from the french text of Alain Tercinet

© Frémeaux & Associés 2012

(1) Ron Frankl, «Charlie Parker», Chelsea House Publishers, NYC, 1993.

(2) Jack Chambers, «Milestones 1 – The Music and Times of Miles Davis to 1960», University of Toronto Press, 1983.

(3) Gary Giddins, «Celebrating Bird – The Triumph of Charlie Parker», Da Capo Press, 1999.

(4) Ian Carr, «Miles Davis», HarperCollins, 1999.

(5) Phil Schaap, at www.jazzwax.com, 25th August 2010.

(6) In the sleeve-notes for «Charlie Parker on Dial – The Complete Sessions», Spotlite SPJ-CD 4-101.

(7) Martin Williams, «The Jazz Tradition», Oxford University Press, NYC, 1983.

(8) See (2).

(9) John Detro, «JazzTimes Historical Notes: Bird’s Dial Sessions», JazzTimes, January 1989.

BIRD Vol. 4 DISCOGRAPHICAL NOTES

MILES DAVIS ALL STARS

Phil Schaap’s statement throws doubt on the numbering of the Savoy takes. Beneath the title Wailin’ Willie some discographies refer to a hypothetical take #4 of Little Willie Leaps. This is actually the (renamed) take #3 from Savoy XP 8098 and MG 9034.

BARRY ULANOV’S ALL STAR MODERN JAZZ MUSICIANS

Several titles were recorded without Charlie Parker:

I SURRENDER DEAR (Lennie Tristano + rhythm) – 13/9/1947

EVERYTHING IS YOURS (Sarah Vaughan + rhythm) – 8/11/1947

DON’T BLAME ME (Tristano/Bauer/Potter) – 8/11/1947

TEA FOR TWO (LaPorta + rhythm) – 8/11/1947

DIAL SESSIONS

There are many naming-errors – too numerous to list here – in the various takes of a title, according to its different editions or reissues. A complete list is provided by Edward M. Komara in his book «The Dial Recordings of Charlie Parker – A Discography» (Greenwood Publishing Group, 1998).

PRIVATE RECORDINGS NOT IN THIS SELECTION

« In September 1947 Charlie Parker was recorded with Allen Eager in New York at photographer Milton H. Greene’s studio. Three titles – SWAPPING HORNS, ALL THE THINGS YOU ARE, ORIGINAL HORNS – appear on the CD «Allen Eager In the Land of Oo-Bla-Dee» (Uptown 27. 49).

Charlie Parker’s meeting with the Dizzy Gillespie Big Band in Chicago gave rise to several amateur recordings which are almost inaudible (although that didn’t prevent them from being issued). Once again, only the solos of Bird were recorded; under those circumstances, their interest is limited.

«?Lorsque Charlie Parker atteignit à la renommée avec ses thèmes bop, chacun modifia son style. Le batteur, le pianiste, le chanteur, tout le monde.?»

Anita O’Day (High Times, Hard Times)

«?When Charlie Parker became popular with his be-bop tunes, everybody had to change his style – the drummer, the piano player, the singer, whoever ?»

Anita O’Day (High Times, Hard Times)

CD 1

MILES DAVIS ALL STARS

NYC, 14/8/1947

1. MILESTONES 0’10

2. MILESTONES 2’36

3. MILESTONES 2’45

4. LITTLE WILLIE LEAPS 0’48

5. LITTLE WILLIE LEAPS 3’10

6. LITTLE WILLIE LEAPS 2’51

7. HALF NELSON 2’51

8. HALF NELSON 2’44

9. SIPPIN’ AT BELL’S 0’55

10. SIPPIN’ AT BELL’S 2’22

11. SIPPIN’ AT BELL’S 0’06

12. SIPPIN’ AT BELL’S 2’28

BARRY ULANOV’S

ALL STAR MODERN JAZZ MUSICIANS

NYC, 13/9/1947

12. KOKO 1’10

13. HOT HOUSE 5’17

14. FINE AND DANDY 3’31

20/9/1947

13. KOKO 1’10

14. ON THE SUNNY SIDE OF THE STREET 3’28

15. HOW DEEP IS THE OCEAN 3’05

16. TIGER RAG 3’55

17. 52nd STREET THEME 0’45

A NITE AT CARNEGIE HALL

Carnegie Hall, NYC, 29/9/1947

18. NIGHT IN TUNISIA 5’15

19. DIZZY ATMOSPHERE 4’08

20. GROOVIN’ HIGH 5’19

21. CONFIRMATION 5’43

22. KOKO 4’21

TOTAL : 71’43

CD 2

CHARLIE PARKER QUINTET

NYC, 28/10/1947

1. DEXTERITY 2’57

2. DEXTERITY 2’57

3. BONGO BOP 2’43

4. BONGO BOP 2’42

5. DEWEY SQUARE (PREZOLOGY) 3’27

6. DEWEY SQUARE 3’01

7. DEWEY SQUARE 3’07

8. THE HYMN 2’30

9. THE HYMN (SUPERMAN) 2’26

10. BIRD OF PARADISE 3’06

11. BIRD OF PARADISE 3’08

12. BIRD OF PARADISE 3’09

13. EMBRACEABLE YOU 3’43

14. EMBRACEABLE YOU 3’21

4/11/1947

15. BIRD FEATHERS (SCHNOURPHOLOGY) 2’50

16. KLACT-OVEESEDS-TENE 3’04

17. KLACT-OVEESEDS-TENE 3’04

18. SCRAPPLE FROM THE APPLE 2’41

19. SCRAPPLE FROM THE APPLE 3’00

20. MY OLD FLAME 3’12

TOTAL = 60’59

CD 3

CHARLIE PARKER QUINTET

NYC, 4/11/1947

1. OUT OF NOWHERE 4’05

2. OUT OF NOWHERE 3’50

3. OUT OF NOWHERE 3’04

4. DON’T BLAME ME 2’47

BARRY ULANOV AND HIS ALL STAR METRONOME JAZZMEN

NYC, 8/11/1947

5. 52nd STREET THEME 1’42

6. DONNA LEE 2’58

7. FATS FLAT 2’50

8. GROOVIN’ HIGH 3’32

9. KOKO into ANTHROPOLOGY 6’15

CHARLIE PARKER SEXTET

NYC, 17/12/1947

10. DRIFTING ON A REED (GIANT SWING) 2’59

11. DRIFTING ON A REED 2’55

12. DRIFTING ON A REED

(AIR CONDITIONING) 2’53

13. QUASIMADO 2’56

14. QUASIMADO (TRADE WINDS) 2’57

15. CHARLIE’S WIG 2’50

16. CHARLIE’S WIG (BONGO BOP) 2’49

17. CHARLIE’S WIG 2’45

18. BONGO BEEP (DEXTERITY) 3’01

19. BONGO BEEP (BIRD FEATHERS) 3’00

20. CRAZEOLOGY 1’00

21. CRAZEOLOGY 0’34

22. CRAZEOLOGY 3’00

23. CRAZEOLOGY 3’01

24. HOW DEEP IS THE OCEAN 3’24

25. HOW DEEP IS THE OCEAN 3’07

TOTAL : 75’11

L’intégrale Charlie Parker, réalisée par Alain Tercinet pour Frémeaux & Associés a pour mission de présenter la quasi-intégralité des titres gravées en studio ainsi que des oeuvres diffusées sur les ondes. Des enregistrements privés ont été écartés de la sélection pour respecter une cohérence sonore et un niveau de qualité esthétique à la hauteur du génie de Charlie Parker.

The aim of ’The Complete Charlie Parker’, compiled for Frémeaux & Associés by Alain Tercinet, is to present (as far as possible) every studio-recording by Parker, together with titles featured in radio-broadcasts. Private recordings have been deliberately omitted from this selection to preserve a consistency of sound and aesthetic quality equal to the genius of this artist.

CD THE COMPLETE CHARLIE PARKER INTEGRALE CHARLIE PARKER VOLUME 4 BIRD OF PARADISE 1947, CHARLIE PARKER © Frémeaux & Associés 2012 (frémeaux, frémaux, frémau, frémaud, frémault, frémo, frémont, fermeaux, fremeaux, fremaux, fremau, fremaud, fremault, fremo, fremont, CD audio, 78 tours, disques anciens, CD à acheter, écouter des vieux enregistrements, albums, rééditions, anthologies ou intégrales sont disponibles sous forme de CD et par téléchargement.)