- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

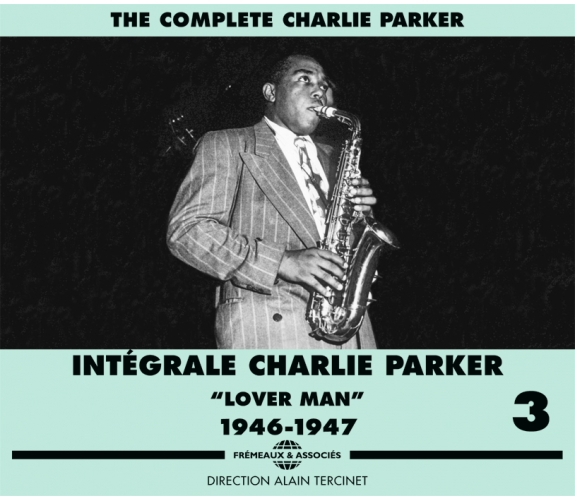

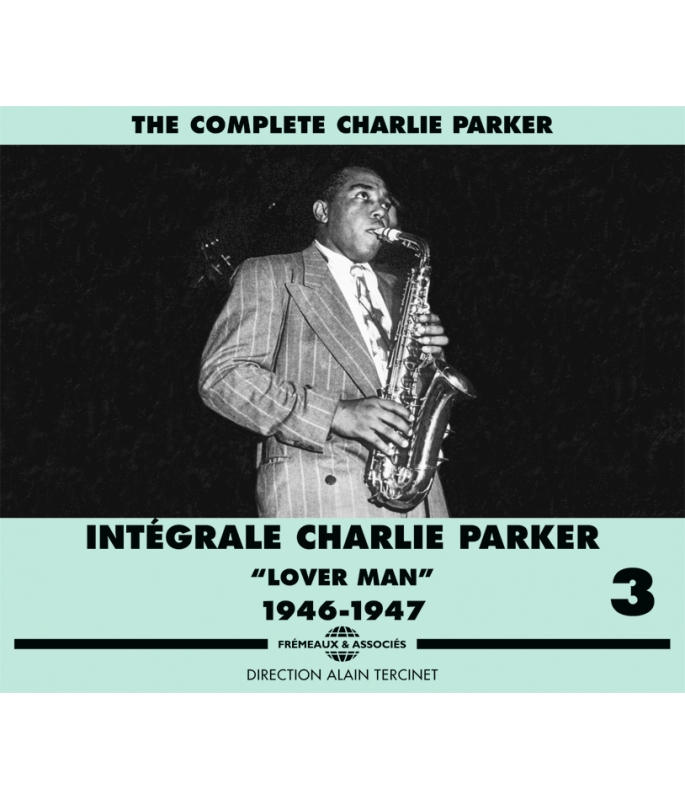

LOVER MAN - 1946-1947

CHARLIE PARKER

Ref.: FA1333

Artistic Direction : ALAIN TERCINET

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Total duration of the pack : 3 hours 26 minutes

Nbre. CD : 3

LOVER MAN - 1946-1947

LOVER MAN - 1946-1947

“When Bird left New York he was a king, but out in Los Angeles he was just another broke, weird, drunken nigger playing some strange music. Los

Angeles is a city built on celebrating stars and Bird didn’t look like no star.” M. DAVIS

The aim of 'The Complete Charlie Parker', compiled for Frémeaux & Associés by Alain Tercinet, is to present (as far as possible) every studio-recording by Parker, together with titles featured in radio-broadcasts. Private recordings have been deliberately omitted from this selection to preserve a consistency of sound and aesthetic quality equal to the genius of this artist.

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Moose The MoocheCharlie Parker Septet00:02:591946

-

2Moose The Mooche (Master)Charlie Parker Septet00:03:041946

-

3Moose The Mooche 2Charlie Parker Septet00:02:561946

-

4Yarbird SuiteCharlie Parker Septet00:02:401946

-

5Yardbird Suite (Master)Charlie Parker Septet00:02:551946

-

6OrnithologyCharlie Parker Septet00:03:011946

-

7Ornithology (Bird Lore)Charlie Parker Septet00:03:191946

-

8Ornithology (Master)Charlie Parker Septet00:03:021946

-

9Night In Tunisia (Famous also break)Charlie Parker Septet00:00:491946

-

10Night In TunisiaCharlie Parker Septet00:03:081946

-

11Night In Tunisia (Master)Charlie Parker Septet00:03:051946

-

12AnnoucementCharlie Parker - Jazz At The Philharmonic00:02:161946

-

13Japt BluesCharlie Parker - Jazz At The Philharmonic00:11:021946

-

14I Got RhythmCharlie Parker - Jazz At The Philharmonic00:13:001946

-

15Announcement MedleyCharlie Parker - Jatp All Stars00:01:201946

-

16Medley Tea For Two Body And Soul CherokeeCharlie Parker - Jatp All Stars00:08:281946

-

17Ornithology 2Charlie Parker/Nat King Cole Trio and Guest00:03:101946

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Max Is Making WaxCharlie Parker Quintet00:02:331946

-

2Lover ManCharlie Parker Quintet00:03:211946

-

3The GipsyCharlie Parker - Howard McGhee Quintet00:03:031946

-

4Be BopCharlie Parker00:02:551946

-

5Home Cooking I (S' Wonderful)Charlie Parker00:02:221947

-

6Home Cooking II (Cherokee)Charlie Parker00:02:081947

-

7Home Cooking III (I Got Rhythm)Charlie Parker00:02:271947

-

8Lullaby In RhythmCharlie Parker00:03:061947

-

9Yardbird SuiteCharlie Parker00:02:141947

-

10BluesCharlie Parker00:01:061947

-

11This Is Always MasterCharlie Parker Quartet00:03:131947

-

12This Is AlwaysCharlie Parker Quartet00:03:091947

-

13Dark ShadowsCharlie Parker Quartet00:04:071947

-

14Dark Shadows IICharlie Parker Quartet00:03:141947

-

15Dark Shadows III (Master)Charlie Parker Quartet00:03:101947

-

16Dark Shadows IVCharlie Parker Quartet00:02:591947

-

17Bird's NestCharlie Parker Quartet00:02:511947

-

18Bird's Nest IICharlie Parker Quartet00:02:501947

-

19Bird's Nest IIICharlie Parker Quartet00:02:441947

-

20Cool Blues (Hot Blues)Charlie Parker Quartet00:01:591947

-

21Cool Blues Blowtop BluesCharlie Parker Quintet00:02:231947

-

22Cool Blues (Master)Charlie Parker Quartet00:03:081947

-

23Cool BluesCharlie Parker Quartet00:02:481947

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Relaxin' At CamarilloCharlie Parker's New Stars00:03:021947

-

2Relaxin' At Camarillo II (Master)Charlie Parker's New Stars00:03:071947

-

3Relaxin' At Camarillo IIICharlie Parker's New Stars00:03:011947

-

4Relaxin' At Camarillo IVCharlie Parker's New Stars00:02:571947

-

5CheersCharlie Parker's New Stars00:03:111947

-

6Cheers IICharlie Parker's New Stars00:03:021947

-

7Cheers IICharlie Parker's New Stars00:03:021947

-

8Cheers IV (Master)Charlie Parker's New Stars00:03:031947

-

9Carvin' The BirdCharlie Parker's New Stars00:02:441947

-

10Carvin' The Bird (Master)Charlie Parker's New Stars00:02:441947

-

11Stupendous (Master)Charlie Parker's New Stars00:02:531947

-

12StupendousCharlie Parker's New Stars00:02:591947

-

13Dee Dee's DanceCharlie Parker - Howard McGhee Quintet00:03:571947

-

14Donna LeeCharlie Parker All Stars00:03:181947

-

15Donna Lee IICharlie Parker All Stars00:02:341947

-

16Donna Lee IIICharlie Parker All Stars00:02:381947

-

17Donna Lee (Master)Charlie Parker All Stars00:02:361947

-

18Chasin' The BirdCharlie Parker All Stars00:02:571947

-

19Chasin' The Bird IICharlie Parker All Stars00:03:231947

-

20Chasin' The Bird (Master)Charlie Parker All Stars00:02:471947

-

21CherylCharlie Parker All Stars00:03:011947

-

22BuzzyCharlie Parker All Stars00:03:021947

-

23Buzzy IICharlie Parker All Stars00:00:361947

-

24Buzzy IIICharlie Parker All Stars00:02:411947

-

25Buzzy IVCharlie Parker All Stars00:00:241947

-

26Buzzy (Master)Charlie Parker All Stars00:02:311947

INTÉGRALE Charlie Parker 3 “LOVER MAN”

INTÉGRALE Charlie Parker 3

“LOVER MAN” 1946-1947

Proposer une véritable “intégrale” des enregistrements laissés par Charlie Parker est actuellement impossible et le restera longtemps. Peu de musiciens ont suscité de leur vivant autant de passion. Plus d’un demi-siècle après sa disparition, des inédits sont publiés et d’autres – dûment répertoriés – le seront encore. Bon nombre d’entre eux ne contiennent que les solos de Bird car ils furent enregistrés à des fins privées par des musiciens désireux de disséquer son style. Sur le seul plan du son, ils se situent en majorité à la limite de l’audible voire du supportable. Faut-il rappeler, qu’à l’époque, leurs auteurs employaient des enregistreurs portables sur disque, des magnétophones à fil, à bande (acétate ou papier) et autres machines devenues obsolètes, engendrant des matériaux sonores fragiles ? Aucun solo joué par Charlie Parker n’est certes négligeable, toutefois en réunissant chronologiquement la quasi-intégralité de ce qu’il grava en studio et de ce qui fut diffusé à l’époque sur les ondes, il est possible d’offrir un panorama exhaustif de l’évolution stylistique de l’un des plus grands génies du jazz ; cela dans des conditions d’écoute acceptables. Toutefois lorsque la nécessité s’en fait sentir stylistiquement parlant, la présence ponctuelle d’enregistrements privés peut s’avérer indispensable. Au mépris de la qualité sonore.

Une fois son engagement au Billy Berg’s de Los Angeles terminé, Gillespie s’empressa de regagner New York. Sans Parker qui, en fait, désirait quelque peu prendre ses distances et retrouver ses galons de leader. L’occasion lui en avait été offerte au Finale Club où il dirigea un quintette dans lequel figurait son nouveau partenaire d’élection, Miles Davis (cf. vol. 2). Conséquence de ce séjour prolongé au bord du Pacifique, le 26 février, sur un coin de comptoir il signa un contrat exclusif d’enregistrement d’une durée d’un an avec Dial, le label de Ross Russell propriétaire du Tempo Music Shop. Le second du genre puisque, trois mois plus tôt à New York, il en avait paraphé un premier avec la firme Savoy. Une performance dans son genre…. Ross Russell jouera un rôle important dans la vie de Parker en lui offrant l’opportunité de graver quelques-uns de ses plus beaux disques. Il rédigera aussi sa biographie publiée en 1973 longtemps après la disparition de Bird. Ce fut la première du genre, donc précieuse encore qu’elle véhiculât nombre d’erreurs. Ross Russell y faisait aussi passer ses préjugés avant la plus élémentaire objectivité, se montrant injuste envers Miles Davis et méprisant vis-à-vis de Dean Benedetti, un bon musicien qui n’avait rien d’un parasite. Un regret toutefois : la réduction éditoriale imposée aux textes envoyés en avant-première à Charles Delaunay par Ross Russell. Publiés dans Jazz Hot de novembre 1969 à septembre 1970 sous le titre de « Yardbird in Lotus Land », ils contiennent plus de précieux renseignements sur les débuts de Parker en Californie que l’on en trouve dans « Bird Lives ! ».

L’une des clauses du contrat liant Parker à Dial l’obligeait à enregistrer au moins douze faces en douze mois. Parker pénétra le 28 mars au Radio Recorders Studios escorté de Miles, Lucky Thompson, Vic McMillan, Roy Porter et Arvin Garrison à la guitare. Au piano, Dodo Marmarosa qui remplaçait Joe Albany. Ce dernier avait terminé son engagement au Finale Club sous la houlette de Parker par un sonore « Fuck You, Bird ! » « Avec lui, je n’arrivais pas à me détendre. C’était vraiment très difficile d’affronter ces tensions tout en essayant de jouer aussi bien que j’aurais voulu le faire. Sur un plan musical je ne pouvais pas l’incriminer, il restait l’alpha et l’omega (1). » De Dodo Marmarosa, Leonard Feather avait écrit qu’il s’agissait de « l’un des plus brillants pianistes apparus avec le be bop ». Et l’un des plus originaux qui, malheureusement, disparut pratiquement de la scène du jazz au début des années 1950 pour végéter dans sa ville natale de Pittsburgh. Le solo qu’il prend au cours de la première prise d’Ornithology est le fait de quelqu’un qui, dans sa musique, entendait introduire une part au rêve. La séance se déroula de 13 à 18 heures et Ross Russell ne put s’empêcher de faire remarquer que c’était bien la première fois que Bird était à l’heure… Première composition enregistrée, Moose the Mooche. Parker l’avait écrite dans la voiture de Roy Porter durant le trajet qui séparait son hôtel du studio de Santa Monica Boulevard. Un salut adressé à Emry Byrd, l’invalide revendeur de disques et de stupéfiants devenu son fournisseur. Probablement en contrepartie de dettes passées et à venir, le 3 avril Parker ajoutera un codicille à son contrat : « Moi, soussigné Charlie Parker accorde par la présente la moitié des royalties sur tous les contrats signés avec Dial Records Company à Emry Byrd. »

Suivirent Yardbird Suite, sans doute la composition de Bird la plus célèbre - la plus reprise aussi - et Ornithology. À 15 h 30 tout fut mis en boîte bien que, à chaque fois, plusieurs prises aient été nécessaires afin de satisfaire au goût de la perfection manifesté par Parker en studio. Après une pause de vingt minutes, arriva le moment d’attaquer le quatrième morceau. Rien n’a été prévu. Ross Russell suggère alors Night in Tunisia. Il s’en mordit les doigts car il faudra deux bonnes heures pour que l’orchestre se tirât du piège tendu par un break pris d’emblée par Bird ; si exceptionnel qu’il sera publié tel quel – Parker avouera ne pas être sûr de pouvoir le rééditer dans son intégralité. Roy Porter : « Personne n’arrivait à compter pendant ce break parce que Bird doublait, triplait, quadruplait et tout ce qu’on veut lorsqu’il jouait ces quatre mesures. Il nous fichait dedans à chaque fois ! À la fin Miles Davis prit la décision d’aller se poster dans un coin, d’écouter et d’abaisser la main sur le premier temps de la cinquième mesure. C’est ainsi que la section rythmique réussit à tomber en place (2). » Une seconde séance était prévue dans un délai de soixante jours ; il fallut attendre quatre mois. Entre temps Norman Granz avait de nouveau sollicité Parker pour un concert du JATP donné à l’Embassy Theatre le 22 avril. Par sa remarquable intervention au cours de I Got Rhythm, Bird montra la distance qui séparait maintenant son univers de ceux - héritiers de la « Swing Era » en dépit de leurs audaces - liés à ses interlocuteurs, Buck Clayton, Coleman Hawkins et même Lester Young. Et cela quelle que soit la révérence qu’il manifestait à leur égard. Sur un thème aussi routinier que JATP Blues, inspiré sans aucun doute par l’introduction esquissée par Pres, Parker prit la parole et s’envola pour trois chorus magistraux. Au Streets of Paris, Norman Granz réunira, durant le mois de mai, trois saxophonistes alto - Benny Carter, Willie Smith, Charlie Parker -, le trio de Nat King Cole et Buddy Rich. Le prétexte était tout trouvé : Benny Carter venait de remporter dans sa catégorie le référendum organisé par le magazine Esquire. De leur côté, Willie Smith et Charlie Parker étaient bien placés derrière Johnny Hodges dans celui de Down Beat (Bird battra le « Rabbit » en 1948 chez Metronome mais en 1950 seulement dans Down Beat). Une confrontation aurait pu être passionnante mais, la formule du medley ayant été choisie, elle n’eut pas lieu. Parker y interpréta une belle version de Cherokee et, probablement, Ornithology qui ne fut pas retenu dans la transcription de l’AFRS Jubilee contenant le pot pourri.

Jusque-là tout allait pour le mieux dans le meilleur des mondes. Non content d’assurer ses engagements, Parker, infatigable, courrait des jam-sessions que sa seule présence réanimait. Toutefois, il allait découvrir brutalement que la Californie n’avait rien d’un paradis. Miles était reparti à New York, le Finale Club avait été fermé par la police pour une histoire de licence et Moose the Mooche était sous les verrous. Du coup, Bird essaya de pallier aux affres du manque en absorbant du gin en quantités colossales. Howard McGhee le retrouvera vivant dans un garage désaffecté. Il l’engagea sur le champ dans l’octette qu’il dirigeait au Swing Club et au Streets of Paris. Sonny Criss : « Cette façon dont Bird pouvait tenir le poste de premier alto, je ne l’ai jamais retrouvée ailleurs depuis. C’était une véritable leçon. La manière dont il phrasait… Je ne crois pas toutefois qu’il ait été complètement heureux. La formation portait le nom d’Howard McGhee et je ne pense pas qu’il appréciait ça tellement (3). » Le lundi 29 juillet à 23 heures, pénètrèrent dans les Studios McGregor sur Western Avenue, trois musiciens réunis par Howard McGhee afin de donner la réplique à Bird : le batteur de sa formation, Roy Porter, un pianiste, Jimmy Bunn, ancien partenaire de Gerald Wilson, et Bob Kesterton arrivé en scooter avec sa basse. Les supporters avaient été soigneusement tenus à l’écart et, en dehors des techniciens, n’étaient présents qu’un saxophoniste, Bobby Dukoff, le correspondant du Billboard, Elliott Grennard, Slim, chargé du transport des instruments, Ross Russell et son associé Marvin Freeman accompagné de son frère Richard, psychiatre de son état. Parker nageait en plein désarroi. Pour pallier au manque, il usait maintenant d’un substitut à base d’alcool et de benzédrine qui détruisait son système nerveux. Roy Porter : « Yard est arrivé à la séance complètement malade du fait de son problème d’héroïne. Il batailla pendant Lover Man et The Gipsy mais, lorsque arriva le tour de Bebop et de Max is Making Wax, Bird était totalement absent ; vraiment malade. Ce qu’il joua sur ces morceaux n’était rien d’autre que son âme (4). » Malgré l’absorption de phénobarbital concédé, après bien des hésitations, par Richard Freeman, Parker n’arriva pas à reprendre le dessus. Finalement Slim le raccompagna au Civic Hotel pendant qu’Howard McGhee gravait en quartette Trumpet at Tempo et Thermodynamics pour tenter de sauver la séance. Elliott Grennard y trouva l’inspiration de sa très belle nouvelle, « Sparrow’s Last Jump », qui fut publiée au mois de mai 1947 dans Harper’s Magazine (5). Parker en voulut beaucoup à Ross Russell d’avoir publié des faces qui le montraient dans un tel état de confusion mentale. Il n’en reste pas moins que Lover Man au long duquel Parker, angoissé, tente d’exorciser ses démons au travers de la musique, reste et restera l’une de ses interprétations les plus bouleversantes qui soient. Charles Mingus désigna ce Lover Man comme le disque de Parker qu’il préfèrait « pour l’émotion qu’il contient et son habileté à transcrire cette émotion (6). »

Durant la nuit, Bird s’endormit avec une cigarette allumée, mettant le feu à la literie de sa chambre d’hôtel. Arrêté, retrouvé au bout de dix jours dans une cellule appartenant à la section psychiatrique de la prison de Los Angeles, Parker sera transféré au Camarillo State Mental Hospital, situé dans le comté de Ventura, grâce à l’intervention de Ross Russell. Il y restera d’août 1946 à janvier 1947, un temps en compagnie de Joe Albany. Un séjour au cours duquel il recevait les visites de quelques musiciens et de Doris, sa troisième épouse, tout en se refaisant une santé, une fois sa cure de désintoxication achevée. Comme les médecins ne lui donnèrent l’autorisation de jouer de l’alto qu’à la toute fin de son séjour, Bird fera du jardinage et de la maçonnerie. Ce qui ne lui déplaisait pas, acceptant sans problème de troquer le saxophone contre une truelle. Plus d’une soirée de bienvenue fut organisée à sa sortie. L’une d’entre elles se déroula le 1er février, au domicile du trompettiste Chuck Kopely. Les trois fragments intitulés Home Cookin’, tout comme Yardbird Suite, Lullaby in Rhythm – ils seront publiés par Dial – et Blues donnent à entendre un musicien de nouveau en possession de ses moyens, apparemment débarrassé du sentiment de panique qui l’habitait. Buddy Collette évoqua un autre hommage rendu à Parker, cette fois au Jack’s Basket Room sur Central Avenue. « Tous les saxophonistes alto et ténor étaient présents, Sonny Criss, Wardell Gray, Dexter Gordon, Gene Phillips, Teddy Edwards, Jay McNeely (entre autres). Tous jouèrent. Bird était assis, souriant. La nuit fut longue. Finalement, il monta sur l’estrade ; je ne pense pas qu’il ait pris plus de trois ou quatre chorus pour raconter une histoire ; complète avec toutes les nuances possibles jusqu’à sa conclusion. Après lui, plus personne n’osa émettre une seule note. Chacun remballa son instrument et rentra chez lui tellement ce qu’il avait joué était irréfutable et juste (7). »

Reposé, désintoxiqué, Parker paraissait en grande forme. Au Billy Berg’s, il animait les matinées du dimanche en compagnie du trio d’Erroll Garner. Du coup, ce fut avec lui qu’il se rendit au studio pour graver une nouvelle séance Dial, en amenant avec lui à titre d’invité, Earl Coleman, un épigone de Billy Eckstine, dont il s’était entiché. Ce qui fut loin d’enchanter Ross Russell. Ironie du sort, Dark Shadows sera le titre de son catalogue qui se vendit le mieux. Shorty Rogers en orchestrera d’ailleurs le chorus de Parker pour la section de saxes de Woody Herman dans I’ve Got News for You… En l’absence du chanteur furent mis en boîte, Bird’s Nest, une intéressante paraphrase de I Got Rhythm, et un chef-d’œuvre à l’état pur, Cool Blues. Au travers des prises successives avec leurs subtiles variations apparaît le perfectionnisme que Bird recherchait lors de ses séances en studio. Le tempo médium/rapide de la première prise (Hot Blues) ne convient pas vraiment à Garner donc, dans la seconde (Blowtop Blues), le tempo ralentit avant de s’accélérer légèrement à nouveau lors de la troisième prise. Garner y est excellent ce qui ne dissuade pas Parker de reprendre une nouvelle fois Cool Blues… sur un tempo à nouveau un peu plus rapide. Pour un résultat qui tutoie la perfection. Une semaine plus tard, lors de sa dernière séance californienne, Parker dirigeait ses « New Stars », au nombre desquelles se comptaient l’excellent Barney Kessel à la guitare et Wardell Gray au ténor. Le premier morceau, un blues, Past Dues, sera curieusement rebaptisé Relaxin’ at Camarillo – un titre que Bird détestait et on le comprend - par la seule volonté de Ross Russell, obnubilé par le succès qu’avait rencontré le disque de Muggsy Spanier, Relaxin’ at Touro. Pour l’occasion, Barney Kessel avoua avoir eu quelques sueurs froides : Parker avait écrit le thème avec un crayon à mine extra dure sur un papier bon marché à gros grain, ce qui le rendait pratiquement indéchiffrable. En sus, à la moindre rature le dit papier réagissait à la façon d’un buvard…Ce qui n’empêcha pas Kessel de fort bien tirer son épingle du jeu. Les trois autres thèmes, Cheers, Carvin’ the Bird et Stupendous, tous excellents supports pour l’improvisation, sont crédités à Howard McGhee dans la formation duquel Parker va de nouveau entrer. Grâce à un enregistreur portatif, Dean Benedetti tint le journal de bord de cet engagement au Hi-De-Ho Club, ne gravant malheureusement que les chorus de Bird. Dee Dee’s Dance donne une idée du bain musical dans lequel était alors plongé Parker (8). Distraction ou conséquence d’une demande de Ross Russell qui conserva cet acétate dans ses réserves, on y entend Howard McGhee et Hampton Hawes.

Ayant accepté un engagement à Chicago, Charlie Parker quitta définitivement Los Angeles le 4 avril, en emmenant avec lui Howard McGhee. Fort de ses droits, Ross Russell va le suivre, ce qui fournira l’occasion d’un très bel imbroglio juridique, les représentants de Savoy brandissant de leur côté un contrat d’exclusivité également signé par Parker le 1er décembre 1945. Un compromis sera finalement trouvé, Bird enregistrant alternativement pour les deux labels jusqu’à l’expiration du contrat Dial. Le 8 mai, pour le compte de Savoy, il prend le chemin du Harry Smith’s Studio en compagnie de Miles Davis. Leur association s’est ressoudée le mois précédent à l’occasion d’un engagement au Three Deuces. Selon les termes de son contrat, doivent être mises en boîte deux compositions originales – Donna Lee et Chasin’ the Bird - accompagnées de deux blues, en l’occurrence Buzzy et Cheryl dédié à la fille de Miles. Bud Powell qui, cette fois, n’a pas fait faux-bond, tient le piano. Ce qui n’ira pas sans entraîner quelques escarmouches avec Bird, l’entente entre les deux hommes étant très loin d’être idéale : ainsi, au cours de la deuxième prise de Buzzy, Parker s’arrête brusquement de jouer pour réclamer « piano, piano » d’un ton peu amène. Contre toute attente, Miles semble à nouveau pétrifié devant les micros et ne trouve vraiment ses marques qu’au bout d’un certain nombre de prises. Au cours de la séance avait été mis en boîte Donna Lee qui, signé Parker, était en fait l’œuvre de son trompettiste. Un thème qui sera à l’origine d’une rencontre capitale pour Miles lorsque Gil Evans viendra lui demander l’autorisation d’en faire un arrangement pour l’orchestre de Claude Thornhill. Les deux hommes sympathiseront et, au fil de leurs échanges, Evans suggéra à Miles de composer plus qu’il ne le faisait ; en lui prodiguant quelques conseils. On connaît la suite… Au travers de cette séance, Parker montrait une fois de plus son attirance pour la formule du quintette. Une instrumentation, trompette, saxo alto, piano, basse et batterie lui paraissant être un cadre idéal pour s’exprimer. À condition d’être seul maître à bord, d’où le choix qu’il avait fait de Miles Davis comme interlocuteur privilégié : « (Bird) voulait une nouvelle approche de la trompette, un autre concept, un autre son. Il désirait exactement le contraire de ce que Dizzy avait fait, quelqu’un qui complète sa sonorité, pour la mettre en valeur. Voilà pourquoi il m’avait choisi. Dizzy et lui étaient assez semblables dans leur façon de jouer, follement rapides, ils descendaient et montaient les gammes si vite que parfois on n’arrivait plus à les distinguer. Mais quand Bird a joué avec moi, il a disposé de beaucoup d’espace pour faire son truc. Pas comme avec Dizzy. Ils étaient brillants ensemble, peut-être bien les meilleurs dans le genre. Mais moi je laissais de l’espace à Bird et après Dizzy c’est ce qu’il voulait (9). » L’absence de virtuosité spectaculaire, le lyrisme détaché, la sonorité dépourvue de vibrato de Miles engendraient un contraste idéal avec le bouillonnement parkérien qui emportait tout sur son passage. L’association Bird/Miles sera scellée pour un temps.

Alain Tercinet

© 2011 Frémeaux & Associés – Groupe Frémeaux Colombini

(1) Joe Albany Talks to Michael Shera, Jazz Journal, mai 1973.

(2) (4) Roy Porter et David Keller, There & Back, Bayou Press, Oxford, 1991.

(3) Ira Gitler, Swing to Bop, Oxford University Press, NYC, Oxford, 1985.

(5) Sparrow’s Last Jump remporta le prix O’Henry dans la catégorie « Best First Published Story ». La nouvelle d’Elliott Grennard figura dans le recueil « Best American Short Stories – 1948 ». Elle sera reprise dans « Jam Session – An Anthology of Jazz » réunie par Ralph J. Gleason. Actuellement, elle est disponible sur Internet.

(6) Ira Gitler, Jazz Masters of the Forties, NYC, 1966. nlle éd. Da Capo Press, NYC, 1984.

(7) Buddy Collette with Steven Isoardi, Jazz Generations – A life in American music and Society, Continuum, Londres & New York, 2000.

(8) Les enregistrements réalisés par Dean Benedetti ont été maintes fois copiés et recopiés à l’époque par lui-même ou d’autres musiciens. Ainsi un certain nombre en avait été publié quasi officiellement dès la fin des années 1950 sous le titre de « Bird on 52nd Street », avec une qualité sonore très au dessous de la moyenne.

(9) Miles Davis & Quincy Troup, Miles - l’autobiographie, trad. Christian Gauffre, Presses de la Renaissance, 1989.

English notes

A genuine “complete” set of the recordings left by Charlie Parker is impossible today and will remain so for a long time to come. Few musicians aroused so much passion during their own lifetimes and today, more than half a century after his disappearance, previously-unreleased music is published, and other titles – duly listed – will also come to light. A good many contain only solos by Bird, as they were recorded – privately – by musicians wanting to dissect his style. Regarding their sound-quality, most of them are at the limit: barely audible, sometimes almost intolerable, but in fact understandable: those who captured these sounds used portable recorders that wrote direct-to-disc, or wire-recorders, “tapes” (acetate or paper) and other machines now obsolete. Obviously they all produced sound-carriers that were fragile. Of course, no solo ever played by Charlie Parker is to be disregarded. But a chronological compilation of almost everything he recorded – either inside a studio or on radio for broadcast purposes – does make it possible to provide an exhaustive panorama of the evolution of his style (Parker was, after all, one of the greatest geniuses in jazz), and to do so under acceptable listening-conditions. However, since we refer to style, the occasional presence here of some private recordings is indispensable, whatever the quality of the sound.

After his appearance at Billy Berg’s in Los Angeles was over, Gillespie was quick to return to New York, this time without Parker who, to tell the truth, was wanting to put some distance between them, and lead his own group again. Bird seized the chance given to him when he went into the Finale Club fronting a quintet that featured his new favourite partner, Miles Davis (cf. Vol. 2). As a direct consequence of his prolonged stay on the Pacific coast, on February 26th he signed an exclusive recording-contract for one year with Dial, the label owned by Ross Russell, who was also the proprietor of the Tempo Music Shop. It was his second such contract within a year: three months earlier, in New York, he’d also signed his name to a similar agreement with Savoy. Now that was a real performance... Ross Russell would play a major role in Parker’s life: he provided him with the opportunity to cut some of his finest records, and Russell would also write the saxophonist’s biography, published in 1973 long after Bird’s death. The book was the first of its kind, and therefore a precious document even if it does contain a number of errors. Russell‘s prejudices also received more space than basic objectivity, and the biography showed his unfairness to Miles and his condescending attitude towards Dean Benedetti, a good musician who was anything but a parasite. One thing was quite regrettable, however: the editing-scissors that were applied to the texts which Russell sent to Charles Delaunay beforehand. Published in Jazz Hot between the November ‘69 and September ‘70 issues – under the title «Yardbird in Lotus Land» –, Russell’s notes contained much more precious information on the subject of Parker in California than the entire volume of «Bird Lives!» One of the clauses in the contract tying Parker to Dial obliged him to record at least twelve sides in as many months. On March 28th Parker went into Radio Recorders Studios escorted by Miles, Lucky Thompson, Vic McMillan, Roy Porter, and Arvin Garrison on guitar. Pianist Dodo Marmarosa replaced Joe Albany, who’d concluded his last gig with Parker at the Finale Club with a resounding «Fuck you, Bird!» «I couldn’t relax with him around. It was really difficult to face all that tension while trying to play as well as I wanted. But on a musical level I couldn’t hold it against him; he was still the alpha and the omega.»(1) Writing about Dodo Marmarosa, Leonard Feather said he was «one of the most brilliant pianists to appear in bebop». And also one of the most original ones; unfortunately, Dodo practically disappeared from the jazz scene in the early Fifties, and was left to vegetate in his native Pittsburgh. His solo on the first take of Ornithology bears the stamp of a man determined to add dreams to his music.

The session was booked for 1pm to 6pm, and Ross Russell couldn’t resist saying that it was the first time that Bird had turned up on time... The first composition they recorded was Moose the Mooche. Parker had written it in Roy Porter‘s car, on the way over from his hotel to the studio on Santa Monica Boulevard, and it was a reference to Emery Byrd, who sold records. He also peddled drugs; known as Moose the Mooche, he became Parker’s supplier. Probably in exchange for outstanding debts (and those yet to come), Parker added a codicil to his contract on April 3rd stipulating, «I, Charlie Parker do hereby sign one half (1/2) of royalties concerning all contracts with the Dial Record company over to the undersigned Emery Byrd.» The next titles recorded were Yardbird Suite, no doubt Bird’s most famous compositions – and also the most covered – and Ornithology. At 3.30pm they’d finished, even though several takes had been necessary for each tune in order to satisfy the taste for perfection that Parker showed whenever he was in a studio. After a twenty-minute break, the moment came to tackle a fourth tune. They hadn’t planned for this, and so Ross Russell suggested Night in Tunisia. He sorely regretted it later, because it took the musicians a good two hours to extricate themselves from the trap set by Bird with the break he took on the tune. It was so exceptional that it was released on its own, and Parker later confessed he wasn’t sure he could have done it again. As Roy Porter said, «Couldn’t anyone count the break, because Bird was doubling, tripling, quadrupling and everything else on what he played in those four bars. It was throwing all of us! Finally, Miles Davis said he would go in the corner and listen and bring his hand down on the first beat of the fifth bar. That’s how the rhythm section came in right on time.»(2)

A second session was planned to take place within sixty days; in fact they had to wait four months. In the meantime, Norman Granz had solicited Parker again for a JATP concert at the Embassy Theatre on April 22nd. Bird’s remarkable intervention on I Got Rhythm showed the distance that now separated his own universe from those of his new partners – heirs to the Swing Era despite their audacity – i.e. Buck Clayton, Coleman Hawkins, even Lester Young. The distance was real, however much reverence he showed towards the latter. On a theme as routine as JATP Blues, inspired, no doubt, by the introduction sketched out by Pres, Parker jumped in and flew away with three masterful choruses. At the Streets of Paris club in May, Granz reunited three altos – Benny Carter, Willie Smith, Charlie Parker –, the Nat King Cole Trio and Buddy Rich. He didn’t need much of a pretext: Benny Carter had just won his category in Esquire magazine’s poll. As for Willie Smith and Charlie Parker, they were well-placed behind Johnny Hodges in Down Beat’s referendum (Bird would beat «Rabbit» over at Metronome in 1948, but had to wait until 1950 in the columns of Down Beat). A confrontation between them would have been a thrill, but it didn’t take place because a medley formula had been chosen. Parker played a beautiful version of Cherokee and, probably, Ornithology, which wasn’t retained in the AFRS Jubilee transcription that contained the medley. Up until then, everything had been for the best in the best of all possible worlds. Not content to just honour his commitments, the tireless Parker was scouring the city playing jam-sessions, and his presence alone was enough to put life into them. However, he did make the brutal discovery that California was anything but a paradise. Miles had gone back to New York; the Finale Club had been shut down by the police (its licence had run out); and Moose the Mooche was in jail. The latter was a real problem, and Bird tried to stave off his cramps by absorbing colossal quantities of gin. Howard McGhee would find him, still alive, in a disused garage. He immediately hired him to play with the octet he was leading at the Swing Club and the Streets of Paris. According to Sonny Criss: «Whew! The way Bird could play first alto. I’ve never heard anything like that since. That was an education in itself. The way he phrased. At the time, I don’t think he was too happy, because the band was billed as Howard McGhee’s band, and I don’t think he liked that too much.»(3)

On Monday July 29th at 11pm, three musicians trooped into the McGregor Studios on Western Avenue at McGhee‘s bidding to play a session with Bird: they were McGhee’s drummer, Roy Porter, pianist Jimmy Bunn, who used to play with Gerald Wilson, and bassist Bob Kesterton, who arrived on a scooter with his instrument. Fans had been carefully kept at bay and, apart from the technicians, the only people present were: saxophonist Bobby Dukoff; Billboard-correspondent Elliott Grennard; Slim, who transported the instruments; Ross Russell; and Russell’s associate Marvin Freeman, accompanied by his brother Richard, a psychiatrist. Parker was swimming totally in confusion. To offset his habit, he was now using an alcohol- and Benzedrine-based substitute that was destroying his nervous system. According to Roy Porter, «Yard became quite ill during this record date because of his heroin problem (…) Bird struggled through ‘Lover Man‘ and ‘The Gypsy‘, but when he got to the songs ‘Bebop‘ and ‘Max Is Makin’ Wax‘ he was totally out of it. He was a very sick man. But what he did play on those tunes was nothing but soul.»(4) Even after taking the Phenobarbital that was provided – after much hesitation – by Richard Freeman, Parker still couldn’t regain control. In the end, Slim took him back to the Civic Hotel while Howard McGhee recorded Trumpet at Tempo and Thermodynamics with a quartet, to try and save the session. It was an episode that gave Elliott Grennard the inspiration to write his beautiful short-story called «Sparrow’s Last Jump», which was published in the May ‘47 issue of Harper’s Magazine (5). Parker held an enormous grudge against Ross Russell for releasing sides that showed him in such mental disarray. Nonetheless, Lover Man, throughout which Parker, in anguish, attempts to exorcise his demons through the music, remains one of the most overwhelming performances he ever produced. Charles Mingus said that this Lover Man was the Parker record he preferred above all others, «for the feeling he had then and his ability to express that feeling.»(6)

During the night, Bird fell asleep with his cigarette still alight, and he set fire to his bed at the hotel. He was arrested, and resurfaced ten days later in a cell in the psychiatric ward of Los Angeles jail; he was transferred to Camarillo State Mental Hospital in Ventura County after Ross Russell intervened, and remained there from August 1946 to January 1947; Joe Albany accompanied him for a time. During his stay, Bird received visits from a few musicians, and also Doris, his third wife; slowly he recovered his health, finishing his cure for addiction. His doctors, however, only allowed him to play his alto towards the very end of his cure, and so Bird did some gardening and masonry. He quite liked it, and didn’t mind trading his saxophone for a trowel one little bit. More than one coming-home party was organised for his return. One of them took place on February 1st at trumpeter Chuck Kopely‘s house. Fragments such as Home Cookin’, Yardbird Suite or Lullaby in Rhythm – they were released by Dial – together with Blues, allow you to hear a musician in full possession of his faculties again, and apparently freed from the panic-attacks that inhabited him. Buddy Collette has referred to another Parker tribute, this time laid on at Jack’s Basket Room on Central Avenue: «All the tenor and alto players were there – Sonny Criss, Wardell Gray, Dexter Gordon, Gene Phillips, Teddy Edwards, Jay McNeely, and on and on. They all played and Bird just sat and smiled. It was a long night. Finally, Bird got up there and I don’t think he played more than three or four choruses. But he told a complete story, caught all the nuances, tapered off to the end. Nobody played a note after that. Everybody just packed up their horns and went home, because it was so complete, so right.»(7)

Fully-rested, and out of detox, Parker seemed in great shape. At Billy Berg’s, he played matinees on Sundays with Erroll Garner’s trio, and so it was Garner who went into the studios to play piano with him at a new Dial session, together with Earl Coleman; invited along as a guest, Coleman was a Billy Eckstine-epigone to whom Bird had become quite attached. Ross Russell was less than enchanted with the idea but, ironically, Dark Shadows turned out to be the best-seller in his catalogue... Interestingly enough, Shorty Rogers orchestrated Parker’s chorus for Woody Herman’s reed-section on I’ve Got News for You… Without the singer, they taped Bird’s Nest, an interesting paraphrase of I Got Rhythm, and a 100-carat masterpiece, Cool Blues. Over the successive takes, with all their subtle variations, you can glimpse the perfectionism that Bird sought in his studio-sessions. The medium/rapid tempo of the first take (Hot Blues) didn’t really suit Garner; so in the second, (Blowtop Blues), the tempo was slowed before picking up in take three. Garner is excellent here, but it doesn’t dissuade Parker from returning to Cool Blues yet again... at a tempo that is, of course, still faster. This is as close to perfection as it gets. A week later, at his last Californian session, Parker was leading his «New Stars», amongst whom there was the excellent Barney Kessel on guitar, with Wardell Gray playing tenor. The first piece, the blues called Past Dues, would be curiously rechristened Relaxin’ at Camarillo – a title that Bird, understandably, hated – at the insistence of Ross Russell, who was obsessed with the success encountered by Muggsy Spanier’s record Relaxin’ at Touro. Barney Kessel confessed that this session had given him the shivers: Parker had written the tune on a piece of cheap, coarse-grained paper using a very hard pencil, and it was barely legible. Even worse, the slightest alteration made the notes seem as if they’d been written on a blotter... Not that any of this prevented Kessel from pulling it all off excellently. The three other tunes, Cheers, Carvin’ the Bird and Stupendous, all of them brilliant bases for improvisation, are credited to Howard McGhee, whose group Parker went back to later. Thanks to a portable recorder, Dean Benedetti kept a log of their booking at the Hi-De-Ho Club, but unfortunately he only recorded Bird’s choruses. Dee Dee’s Dance gives an idea of the musical bath in which Parker was now soaking.(8) Whether it was just distraction on the part of Ross Russell, or else due to his own request – he kept the acetates in his archives – we can hear both Howard McGhee and Hampton Hawes on these.

After agreeing to a booking in Chicago, Charlie Parker left Los Angeles for good on April 4th, taking Howard McGhee with him. With the law on his side, Ross Russell followed him, and it produced a fine legal imbroglio, with Savoy’s attorneys waving their own exclusive contract, also signed by Parker and dated December 1st 1945. They finally reached a compromise and Bird recorded alternately for both labels until the Dial contract expired. On May 8th he went into Harry Smith’s studio with Miles Davis to do a session for Savoy. Their association had been cemented again the previous month on the occasion of a booking at the Three Deuces. According to the terms of Bird’s contract, two original compositions had to be recorded – Donna Lee and Chasin’ the Bird – accompanied by two blues pieces, in fact Buzzy and Cheryl, which was dedicated to Miles’ daughter. For once, Bud Powell hadn’t left them in the lurch and he played piano on the date. This, obviously, led to some skirmishing, as the entente between Powell and Bird was far from cordiale. On the second take of Buzzy, Parker stops abruptly, calling for «piano, piano» in a barely affable tone. Against all expectations, Miles seems once again to be petrified by the microphone and it takes quite a few takes for him to find his feet. During this session, they’d recorded Donna Lee; although credited to Parker, this was in fact the work of his trumpeter, and the tune would lead to a capital encounter for Miles when Gil Evans came to him requesting permission to arrange it for Claude Thornhill’s orchestra. The two men became friends and, during their exchanges, Evans suggested that Miles should compose a little more than he did, and he gave him some advice... The rest, as they say, is history. In the course of this session, Parker showed once again his liking for the quintet-formula: the instrumentation – trumpet, alto saxophone, piano, bass and drums – seemed an ideal framework for him to express himself... on condition that the ship had only one captain, hence his choice of Miles Davis as his privileged partner: «He wanted a different trumpet approach, another concept and sound. He wanted just the opposite of what Dizzy had done, somebody to complement his sound, to set it off. That’s why he chose me. He and Dizzy were a lot alike in their playing, fast as a motherfucker, up and down the scales so fast sometimes you almost couldn’t tell one from the other. But when Bird started playing with me there was all this space for him to do his shit in without worrying about Dizzy being all up in there with him. Dizzy don’t give him no space. They were brilliant together, maybe the best ever at what they did together. But I gave Bird space and after Dizzy, that’s what he wanted.»(9) The absence of spectacular virtuosity, together with the detached lyricism and vibrato-less sound of Miles, engendered an ideal contrast to the seething Parkerisms that swept all before him. The Bird & Miles association would be sealed for a while.

Adapted by Martin Davies from the french text of Alain Tercinet

© 2011 Frémeaux & Associés – Groupe Frémeaux Colombini

(1) Joe Albany Talks to Michael Shera, Jazz Journal, May 1973.

(2) (4) Roy Porter and David Keller, There & Back, Bayou Press, Oxford, 1991.

(3) Ira Gitler, Swing to Bop, Oxford University Press, NYC, Oxford, 1985.

(5) Sparrow’s Last Jump won the O’Henry Prize in the category «Best First Published Story». Elliott Grennard‘s novella featured in the anthology Best American Short Stories – 1948, and was reprinted in Ralph J. Gleason‘s «Jam Session – An Anthology of Jazz». It’s currently available on the Internet.

(6) Ira Gitler, Jazz Masters of the Forties, NYC, 1966. New edition, Da Capo Press, NYC, 1984.

(7) Buddy Collette with Steven Isoardi, Jazz Generations – A life in American music and Society, Continuum, London & New York, 2000.

(8) The recordings made by Dean Benedetti were copied time and again during this period, both by himself and other musicians. A certain number of them were released quasi-officially as soon as the end of the Fifties under the title «Bird on 52nd Street», with well below-average sound-quality. (9) Miles Davis & Quincy Troup, Miles – The Autobiography, Simon & Schuster, 1989.

discographie

CD 1

CHARLIE PARKER SEPTET

Miles Davis (tp) ; Charlie Parker (as) ; Lucky Thompson (ts) ; Dodo Marmarosa (p) ; Arv Garrison (g)* ; Vic McMillan (b) ; Roy Porter (dm) LA, 28/3/1946

01. MOOSE THE MOOCHE (C. Parker) (Dial LP 201/mx. D1010-1) 2’57

02. MOOSE THE MOOCHE (C. Parker) (master) (Dial 1003/mx. D1010-2) 3’02

03. MOOSE THE MOOCHE (C. Parker) (Dial LP 201/mx. D1010-3) 2’54

04 YARDBIRD SUITE* (C. Parker) (Dial LP 201/mx. D1011-1) 2’38

05. YARDBIRD SUITE* (C. Parker) (master) (Dial 1003/mx. D1011-4) 2’53

06. ORNITHOLOGY * (C. Parker, B. Harris) (Dial LP 208/mx. D1012-1) 2’59

07. ORNITHOLOGY (BIRD LORE)* (C. Parker, B. Harris) (Dial 1006/mx. D1012-3) 3’17

08. ORNITHOLOGY* (C. Parker, B. Harris) (master) (Dial 1002/mx. D1012-4) 3’00

09. NIGHT IN TUNISIA (Famous alto break)* (D. Gillespie, F. Paparelli) (Dial LP 905/mx. D1013-1) 0’47

10. NIGHT IN TUNISIA * (D. Gillespie, F. Paparelli) (Dial LP 201/mx D1013-4) 3’06

11. NIGHT IN TUNISIA * (D. Gillespie, F. Paparelli) (master) (Dial 1002/mx D1013-5.) 3’02

JAZZ AT THE PHILHARMONIC

Buck Clayton (tp) ; Willie Smith, Charlie Parker (as) ; Lester Young, Coleman Hawkins (ts) ; Kenny Kersey (p) ; Irving Ashby (g) ; Billy Hadnott (b) ; Buddy Rich (dm). / Embassy Theater, LA, 22/4/1946

12. Announcement 2’16

13. JATP BLUES (Shrdlu) (Clef 101,102/mx. 101/2/3/4) 11’00

14. I GOT RHYTHM (G. & I. Gershwin) (Mercury LP MG35014) 12’57

JATP ALL STARS

Benny Carte (-1), Willie Smith (-2), Charlie Parker (-3) (as) ; Nat King Cole (p) ; Oscar Moore (g) ; Johnny Miller (b) ; Buddy Rich (dm), Ernie Bubbles Whitman (mc). / AFRS Jubilee 186, LA, may 1946

15. Announcement Medley (Radio Transcription) 1’20

16. MEDLEY 8’26

- TEA FOR TWO (I. Cæsar, V. Youmans) (-1) (Radio Transcription) 2’40

- BODY AND SOUL (J. GREEN, E. Heymann, R. Sour, F. Eyton) (-2) (Radio Transcription) 2’41

- CHEROKEE (R. Noble) (-3) (Radio Transcription) 3’05

CHARLIE PARKER with THE NAT KING COLE TRIO AND GUEST

Charlie Parker (as) ; Nat King Cole (p) ; Oscar Moore (g) ; Johnny Miller (b) ; Buddy Rich (dm) / AFRS Jubilee (?), LA, poss. may 1946

17. ORNITHOLOGY (C. Parker, B. Harris) (Radio Transcription) 3’10

Notes discographiques :

JATP All Stars : Selon “The AFRS Jubilée Transcription series” de Carl A. Hällström et Bo Scherman, cette séance aurait été organisée par Granz en vue d’un éventuel concert.

Chuck Kopely’s Home : En sus de Blues (parfois Kopely Plaza Blues) qui, malgré sa piètre qualité sonore, est intéressant, a survécu un autre fragment, Blues on the Sofa (0’46), quasiment inaudible.

Cool Blues : Il existe une grande confusion dans l’intitulé des prises A et B. La prise A fut baptisée Blowtop Blues sur LP 901 et Hot Blues sur Dial LP 202 et ses équivalents. La prise B fut également intitulée Blowtop Blues sur Dial LP 901, Hot Blues sur les LP Swing et Vogue, Cool Blues partout ailleurs.

Dee Dee’s Dance apporte un témoignage tronqué et d’une piètre qualité sonore sur le dernier engagement de Parker sur la côte Ouest. Considéré longtemps comme irrémédiablement perdu, l’ensemble – ou presque – des acétates et enregistrements divers dus à Dean Benedetti a été publié en 1987 par Mosaic dans un coffret de 7 CD. Passionnant mais d’une écoute difficile.

CD 2

CHARLIE PARKER QUINTET

Howard McGhee (tp) ; Charlie Parker (as) ; Jimmy Bunn (p) ; Bob Kesterton (b) ; Roy Porter (dm). / LA, 29/7/1946

01. MAX IS MAKING WAX (O. Pettiford) (Dial LP 201/mx. D1021-A) 2’31

02. LOVER MAN (R. Ramirez, J. Davis) (Dial 1007/mx. D1022-A) 3’19

03. THE GIPSY (B. Reed) (Dial 1043/mx. D1023-A) 3’01

HOWARD MCGHEE QUINTET

Idem

04. BE-BOP (D. Gillespie) (Dial 1007/mx. D1024-A) 2’52

CHARLIE PARKER

Charlie Parker (as) ; Russ Freeman (p) ; Arnold Fishkind (b) ; Jimmy Pratt (dm) / Chuck Kopely’s Home, LA, 1 feb. 1947

05. HOME COOKING I (S’ Wonderful) (G. & I. Gershwin) (Dial LP 905/ mx. K903) 2’20

06. HOME COOKING II (Cherokee) (R. Noble) (Dial LP 905/ mx. K904) 2’06

07. HOME COOKING III (I Got Rhythm) (G. & I. Gershwin) (Dial LP 905/ mx. K905) 2’25

08. LULLABY IN RHYTHM (E. Sampson, B. Goodman) (Dial Test /mx. D901/2) 3’04

Howard McGhee, Shorty Rogers, Melvin Broiles (tp) added

09. YARDBIRD SUITE (C. Parker) (Private Recording) 2’12

10. BLUES (trad.) (Private Recording) 1’03

CHARLIE PARKER QUARTET

Charlie Parker (as) ; Erroll Garner (p) ; Red Callender (b) ; Harold «Doc» West (dm) ; Earl Coleman (voc)* / LA, 19/2/1947

07. THIS IS ALWAYS* (J. Myrow, M. Gordon) (master) (Dial 1015/mx. D1051-C) 3’11

08. THIS IS ALWAYS* (J. Myrow, M. Gordon) (Dial LP 202/mx. D1051-D) 3’07

09. DARK SHADOWS* (S. Henry) (Dial LP 202/mx. D1052-A) 4’05

10. DARK SHADOWS* (S. Henry) (Dial LP 901/mx. D1052-B) 3’12

11. DARK SHADOWS* (S. Henry) (master) (Dial 1014/mx. D1052-C) 3’08

12. DARK SHADOWS* (S. Henry) (Dial Test/mx. D1052-D) 2’57

13. BIRD’S NEST (C. Parker) (Dial 1014/mx. D1053-A) 2’49

14. BIRD’S NEST (C. Parker) (Dial LP 202/mx. D1053-B) 2’48

15. BIRD’S NEST (C. Parker) (Dial 1014/mx. D1053-C) 2’42

16. COOL BLUES (HOT BLUES) (C. Parker) (Dial LP 202/mx. D1054-A) 1’57

17. COOL BLUES (BLOWTOP BLUES) (C. Parker) (Dial LP 901/mx. D1054-B) 2’21

18. COOL BLUES (C. Parker) (master) (Dial 1015/mx. D1054-C) 3’06

19. COOL BLUES (C. Parker) (Dial LP 901/mx. D1054-D) 2’48

CD 3

CHARLIE PARKER’S NEW STARS

Howard McGhee (tp) ; Charlie Parker (as) ; Wardell Gray (ts) ; Dodo Marmarosa (p) ; Barney Kessel (g) ; Red Callender (b) ; Don Lamond (dm). LA, 26/2/1947

01. RELAXIN’ AT CAMARILLO (C. Parker) (Dial 1030/mx. D1071-A) 3’00

02. RELAXIN’ AT CAMARILLO (C. Parker) (master) (Dial 1012/mx. D1071-C) 3’05

03. RELAXIN’ AT CAMARILLO (C. Parker) (Dial LP 901/mx. D1071-D) 2’59

04. RELAXIN’ AT CAMARILLO (C. Parker) (Dial LP 202/mx. D1071-E) 2’55

05. CHEERS (H. McGhee) (Dial LP 202/mx. D1072-A) 3’09

06. CHEERS (H. McGhee) (Dial Test/mx. D1072-B) 3’00

07. CHEERS (H. McGhee) (Dial Test/mx. D1072-C) 3’00

08. CHEERS (H. McGhee) (master) (Dial 1013/mx. D1072-D) 3’00

09. CARVIN’ THE BIRD (H. McGhee) (Dial LP 901/mx. D1073-A) 2’42

10. CARVIN’ THE BIRD (H. McGhee) (master) (Dial 1013/mx. D1073-B) 2’42

11. STUPENDOUS (H. McGhee) (master) (Dial 1022/mx. D1074-A) 2’51

12. STUPENDOUS (H. McGhee) (Dial LP 202/mx. D1074-B) 2’55

HOWARD McGHEE QUINTET

Howard McGhee (tp) ; Charlie Parker (as) ; Hampton Hawes (p) ; Addison Farmer (b) ; Roy Porter (dm). / Hi-De-Ho Club, LA, 9/3/1947

13. DEE DEE’S DANCE (D. Best) (Private Recording) 3’54

CHARLIE PARKER ALL STARS

Miles Davis (tp) ; Charlie Parker (as) ; Bud Powell (p) ; Tommy Potter (b) ; Max Roach (dm). / NYC, 8/5/1947

14. DONNA LEE (C. Parker) (Savoy LP MG 12009/mx. S3420-2) 3’16

15. DONNA LEE (C. Parker) (Savoy LP MG 12001/mx. S3420-3) 2’32

16. DONNA LEE (C. Parker) (Savoy LP MG 12001/mx. S3420-4) 2’36

17. DONNA LEE (C. Parker) (master) (Savoy 512/mx. S3420-5) 2’34

18. CHASIN’ THE BIRD (C. Parker) (Savoy LP MG 12001/mx. S3421-1) 2’55

19. CHASIN’ THE BIRD (C. Parker) (Savoy LP MG 12009/mx. S3421-2et3) 3’21

20. CHASIN’ THE BIRD (C. Parker) (master) (Savoy 977/mx. S3421-4) 2’45

21. CHERYL (C. Parker) (Savoy 951/mx. S3422-2) 2’58

22. BUZZY (C. Parker) (Savoy MG 12009/mx. S3423-1) 3’00

23. BUZZY (C. Parker) (Savoy MG 12001/mx. S3423-2) 0’35

24. BUZZY (C. Parker) (Savoy MG 12001/mx. S3423-3) 2’39

25. BUZZY (C. Parker) (Savoy LP MG 1200/mx. S3423-4) 0’23

26. BUZZY (C. Parker) (master) (Savoy 928/mx. S3423-5) 2’31

CD THE COMPLETE Charlie Parker 3 INTÉGRALE Charlie Parker 3 © Frémeaux & Associés (frémeaux, frémaux, frémau, frémaud, frémault, frémo, frémont, fermeaux, fremeaux, fremaux, fremau, fremaud, fremault, fremo, fremont, CD audio, 78 tours, disques anciens, CD à acheter, écouter des vieux enregistrements, albums, rééditions, anthologies ou intégrales sont disponibles sous forme de CD et par téléchargement.)