- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

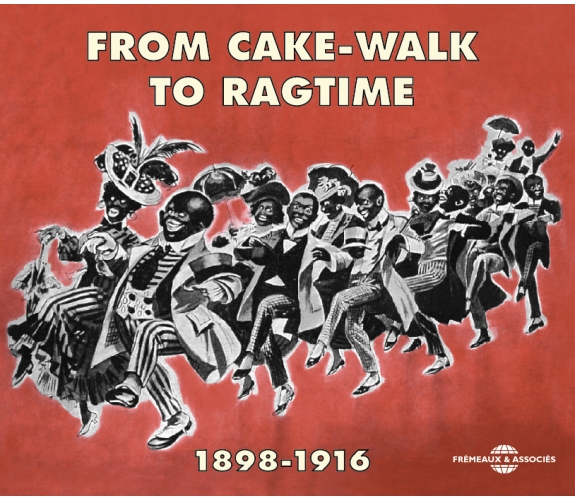

ANTHOLOGIE 1898 - 1916

Ref.: FA067

EAN : 3700368480571

Artistic Direction : OLIVIER BRARD

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Total duration of the pack : 1 hours 36 minutes

Nbre. CD : 2

ANTHOLOGIE 1898 - 1916

- - * * * JAZZMAN

- - SÉLECTION JAZZ HOT

- - SUGGÉRÉ PAR “COMPRENDRE LE JAZZ” CHEZ LAROUSSE

ANTHOLOGIE 1898 - 1916

From dance contests to speakeasies, this popular music called jazz gently evolved. This 2-CD set includes a 32 page booklet with both French and English notes.

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1ELI GREEN S CAKE WALKJOSEPH CULLENSADIE KONINSKY00:02:071898

-

2CAKE WALKORCH ANONYMETRADITIONNEL00:01:421900

-

3SMOKY MOKESMETROPOLITAN ORCHESTRAABE HOLZMANN00:01:281900

-

4WHISTLING RUFUSOLLY OAKLEYKERRY MILLS00:01:431903

-

5THE CAKE WALKTHE VICTOR MINSTRELSTRADITIONNEL00:02:441902

-

6WHISTLING RUFUSSOUSA S BANDKERRY MILLS00:02:261900

-

7(UNIDENTIFIED) CAKE WALKORCH ANONYMETRADITIONNEL00:01:431903

-

8CAKE WALK IN THE SKYVICTOR DANCE ORCHESTRABEN HARNEY00:03:421905

-

9SAINT LOUIS TICKLEOSSMAN DUDLEY TRIOBARNEY00:03:011906

-

10DIXIE GIRLOSSMAN DUDLEY TRIOLAMPE J BODEWALT00:02:111906

-

11LE VRAI CAKE WALKMUSIQUE DE LA GARDE REPUBLICAIDUQUIN00:02:181906

-

12ANONAORCH APGAVIVIAN GRAY00:03:231906

-

13A BUNCH OF RAGSVESS L OSSMANVESS L OSSMAN00:02:161908

-

14THE BUFFALO RAGVESS L OSSMANTOM TURPIN00:02:051909

-

15ALEXANDER S RAGTIME BANDARTHUR COLLINSIRVING BERLIN00:02:541911

-

16ALABAMA SKEDADDLEWILLIAM DITCHAMEDWARD HEESE00:02:331910

-

17ALEXANDER S RAGTIME BANDVICTOR MILITARY BANDIRVING BERLIN00:02:361911

-

18SLIPPERY PLACE RAGVICTOR MILITARY BANDPM HACKER00:02:471911

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1BLACK DIAMOND RAGPRINCE S ORCHESTRAHENRY LODGE00:02:471912

-

2STOMP DANCEVICTOR MILITARY BANDJ I STEWART00:02:341912

-

3THAT MYSTERIOUS RAGROBERT CARRTED SNYDER00:02:421912

-

4GRIZZLY BEARWALTER MILLERGEORGE BOTSFORD00:02:501912

-

5DILL PICKLES HOT STUFF RAGTIMEEMPIRE MILITARY BANDCHARLES L JOHNSON00:02:561912

-

6RAGTIME FROLICSR WHITETRADITIONNEL00:03:091912

-

7I LL DANCE TILL DE SUN BREAKS THROUGHJOYCE S ORCHESTRAARCHIBALD JOYCE00:03:471912

-

8OH THAT YANKIANNA RAGORCH TZIGANE DU VOLNEYMELVILLE GIDEON00:03:071912

-

9BACCHANAL RAGTHE PEERLESS ORCHESTRAANDRE LOUIS HIRSCH00:02:461912

-

10TOO MUCH MUSTARDEUROPE S SOCIETY ORCHESTRACECIL MACKLIN00:03:471913

-

11DOWN HOME RAGEUROPE S SOCIETY ORCHESTRAWILBUR C SWEATMAN00:03:191913

-

12YOU RE HERE AND I M HEREEUROPE S SOCIETY ORCHESTRAJEROME KERN00:02:341914

-

13CASTLE WALKEUROPE S SOCIETY ORCHESTRAJ EUROPE00:03:121914

-

14NOTORIETY RAGFRED VAN EPSK L WIDMER00:02:511914

-

15THAT MOANING SAXOPHONE RAGTHE SIX BROWN BROTHERSTOM BROWN00:02:051914

-

16OPERATIC RAGJOSEPH MOSKOVITZJULIUS LENZBERG00:02:281916

-

17RAGGIN THE SCALEFRED VAN EPSEDWARD CLAYPOOLE00:02:401916

-

18TWO KEY RAGCONWAY S BANDJOE HOLLANDER00:03:011916

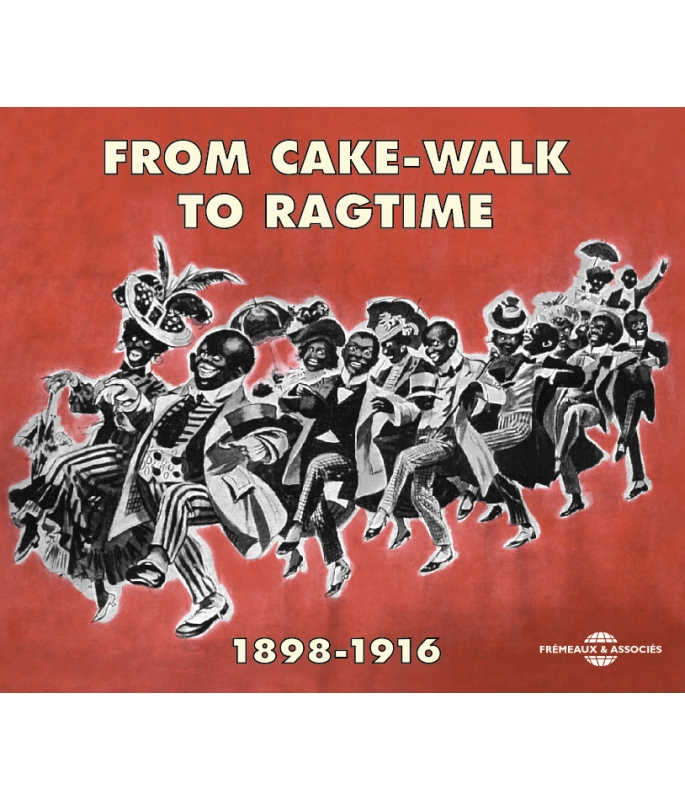

FROM CAKE-WALK TO RAGTIME

FROM CAKE-WALK TO RAGTIME

DU CAKE-WALK AU RAGTIME

1898-1916

Si le vingtième siècle est sans contestation marqué par l’apparition d’une musique rythmée, le jazz, aux accents sauvages et semble-t-il quelque peu désordonnée, du moins à ses débuts où l’on ignore l’origine même du mot (vient-il du mot français jaser, utilisé en Louisiane et dans les ports où les mélanges culturels ont apporté de nombreuses modifications à la langue des autochtones, ou d’un mot d’argot noir à connotation sexuelle?), il n’en est pas moins vrai que de nombreuses influences antérieures ont déterminé ce qu’il est convenu de nommer jass puis jazz la musique de cabarets et de rues (à la Nouvelle-Orléans notamment). Parmi ces influences, si certains conviennent, par purisme et par souci de non-racisme (ou de racisme d’ailleurs!) de trouver uniquement l’origine du jazz dans les chants africains, c’est aller un peu vite en besogne. Il ne faut pas oublier que le jazz n’est pas né à la Nouvelle-Orléans uniquement, mais partout où les populations noires et blanches se côtoyaient en grand nombre dans les grands centres urbains. Les chants religieux, négro-spirituals et gospels en tête, les fanfares, les ménestrels (minstrels), les ballades et les formes orchestrales européennes, le Cake-walk, le Ragtime, les chants créoles, les chants d’esclaves, le Blues et les rythmes africains y ont été pour beaucoup pour donner le jazz, surtout à ses débuts. Et justement, le Ragtime semble être la liaison entre la musique des blancs du XIXe siècle et celle des noirs. Comme le note E. Berendt dans son livre «Das neue Jazzbuch» en 1963: «d’autre part, le Ragtime ressemble, par sa structure, à la musique de piano du XIXe siècle européen, au menuet classique par exemple. Souvent il se compose de plusieurs unités musicales successives, à la fois juxtaposées et reliées, un peu comme dans les valses de Strauss. Tout ce qui au XIXe siècle, a compté dans la musique de piano - Schubert, Chopin, Liszt avant tout, et aussi la marche et la polka - se retrouve dans le Ragtime, mais sur un rythme plus appuyé, plus dynamique, repensé par les Noirs».L’histoire du Ragtime proprement dit a été raconté admirablement par les experts américains Rudi Blesh et Harriet Janis dans leur livre «They All Played Ragtime» publié en 1951 où ils expliquent les origines noires du vrai Ragtime dans les beuglants et autres débits de boissons de Sedalia et de Saint-Louis dans le Missouri où l’on pratiquait des danses frénétiques comme le Cake-walk pendant les années de reconstruction suivant la Guerre Civile, pendant la période des grands pionniers qui a suivi et enfin avec l’émancipation (prétendue) des américains de couleur. Ces Cake-walks étaient exécutés essentiellement d’ailleurs au banjo - celui à quatre cordes utilisé que par les Noirs - pendant les innombrables fêtes organisées surtout par les esclaves noirs, et également au piano au fur et à mesure que cette danse devenait à la mode. Car parmi les Noirs, certains, par leurs affinités, fréquentaient aussi leurs congénères de couleur qui avaient eu l’opportunité de suivre quelques études, et par là même, avaient eu accès au piano jusque-là réservé aux seuls blancs. Les Noirs ont pu, grâce aux instruments réformés de l’armée entre autres, transposer les Cake-walks sur des cornets, des trombones, des saxophones, des clarinettes, des flûtes et des piccolos, et divers hélicons, bientôt transformés en sousaphones (soubassophone en français) par John Philip Sousa d’ailleurs et se regrouper, soit au sein de formations de quartiers dans les grandes villes, soit comme Louis Armstrong, en apprendre les rudiments au sein d’orphelinats au rôle éducatif certain.

Le Ragtime a eu son heure de gloire en gros de 1897 à 1917 et, à travers les différents interprètes, connaîtra des changements de style. Dans les caractéristiques du Ragtime naissant, les musiciens noirs n’ont certes pas su apporter ce quelque chose de plus que ce que les plus cultivés d’entre-eux avaient assimilé en écoutant les concerts classiques et l’opéra. Les syncopes brutales viendront par la suite, donnant une certaine évolution au style. Finalement, il est évident que cette forme musicale typiquement négro-américaine soit devenue un style pianistique. Avec tous ces antécédents, le Ragtime est un genre extrêmement codifié aux règles rigoureusement fixées et, à l’instar de la musique dite sérieuse, n’admet ni ne supporte l’improvisation. Bien sûr, des dérapages ont pu exister et comme Jean-Sébastien Bach en son temps, il est certain que les mêmes musiciens de Ragtime ont dû donner quelques différences à leurs interprétations, au fur et à mesure que le temps s’écoulait. Il n’en ressort pas moins que, à un moment donné, la musique fut éditée dans une forme clairement définie par les compositeurs, ce qui donna lieu à sa dispersion, sa reprise par des compositeurs et des musiciens blancs, et très vite par des Européens qui, tout en gardant l’essence même des compositions, les ont progressivement changé de leur forme originelle, tout en se gardant bien d’en faire évoluer l’esthétique. Une autre conséquence est son adaptation, tout aussi rapide, à des instruments autres que le piano, à l’accordéon tout d’abord, puis au banjo et à la mandoline, tous deux marqués par une sonorité métallique bien prononcée, au xylophone et même au piccolo et au cymbalum! Des duos de banjo ont été enregistrés et le temps faisant son œuvre, le Ragtime a fini par chatouiller l’oreille des compositeurs et des chefs d’orchestres petits ou grands, noirs ou blancs d’ailleurs, qui s’en sont donnés à coeur joie pour apporter aussi leur pierre à l’édifice.

Le Ragtime était en fait dans l’air, sous forme de musiques et de danses populaires. La structure des morceaux n’était pas définie et il fallut attendre Scott Joplin pour avoir des morceaux au style bien établi (Original Rags). Il existait bien avant lui des rags populaires de plusieurs styles. Ces rags étaient chantés, joués au banjo ou sur des pianos, et étaient bien entendu, dansés. Ces rags provenaient des airs de plantations transmis oralement, mais certainement plus encore du répertoire des Minstrels. Ceux-ci étaient des artistes de variétés blancs, barbouillés de noir pour faire plus exotique. Cela est attesté depuis au moins 1827. Ce genre connut un succès et un développement considérables. L’insistance était mise sur le caractère bon enfant du «bon nègre», le «nigger» (négro), stéréotype populaire de l’esclave noir, avec un accent mis sur sa naïveté, son parler mal assuré, sur sa paresse et son goût pour la danse. Bien entendu, ces spectacles étaient insidieusement racistes, mais la bonne société ne s’en souciait guère, cela étant dans les mœurs de l’époque. On était avant la Guerre de Sécession. Ce qui n’a pas empêché plus tard le phénomène inverse de se produire: des noirs grimés en blancs se produisirent et offriront au public blanc et noir la caricature même de leur condition! Les chansons étaient en général bâties sur une stucture AABA (avec une première strophe de huit mesures doublée : A - et une seconde phrase : B - puis à nouveau la première phrase : A), structure que l’on retrouvera plus tard dans le jazz classique. La popularité des Minstrels ne s’arrêtera pas avec la fin du siècle. Bien plus tard en effet, un certain Al Jolson chantera Swanee, de George Gershwin, dans le premier film parlant et chantant en 1927, The Jazz Singer, tout en étant grimé en noir, avec les lèvres rehaussées de rouge et les yeux soulignés de blanc. Lui qui était juif russe d’origine, finalement, donna ses lettres de noblesse à un art qui n’était pas le sien.

Quant au Cake-walk, maillon indispensable au Ragtime naissant, c’était une musique extravertie et syncopée qui accompagnait les concours de danse dans les milieux plutôt noirs et de conditions modestes et dont le prıx attribué au vainqueur était évidemment un énorme et appétissant gâteau fabriqué pour l’occasion, d’où le nom de la danse. C’était en quelque sorte, la plus importante distraction visuelle qui pût donner à la musique une audience générale. Le terme Cake-walk est attesté depuis 1879 dans un journal, le «Harper’s Magazine». Originellement issu du Sud des Etats-Unis, il se répandit très vite dans les villes de l’Est et bientôt en Europe, notamment en France, par l’énorme orchestre de concert dirigé par le Roi de la Marche, le fameux John Philip Sousa dès le printemps 1900. A cette époque, le célèbre Georgia Camp Meeting (de Kerry Mills) était un succès apprécié parmi les populations noires et blanches en Amérique et suivant le succès remporté par Sousa, dont la musique était nommée en France Le Temps du Chiffon (Rag-Time), le grand compositeur impressionniste Claude Debussy mit un point d’honneur à inclure dans sa suite Children’s Corner Suite ce qu’il a appelé The Golliwog’s Cake-Walk. Il composa également une pièce nommée Ménestrels, ce qui montre de sa part un intérêt certain avec ce que lui-même a pu voir et entendre pendant les spectacles alors très populaires de Minstrels donnés par des artistes blancs à la figure noircie au bouchon brûlé. A cette époque, de tels spectacles n’éveillaient aucun sentiment de racisme : l’audience blanche les acceptait comme des spectacles joyeux, harmonieux et vivants, tandis que les Noirs les regardaient du haut des toits en tôle ondulée des théâtres ou de l’extérieur des chapiteaux avec indifférence ou mépris. Une bonne idée de ce que pouvait donner le Cake-walk américain pendant ces années 1890 peut être obtenu par l’écoute de la plus vieille cire de ce recueil «Eli Green’s Cake Walk», enregistrée en 1898 pour la compagnie Berliner par deux banjoïstes aussi célèbres comme Minstrels que comme artistes de concert, Cullen et Collins. C’était au tout début du phonographe et des disques en cire. Bien que les premiers cylindres aient vu le jour quelques années auparavant, il semble que cette musique du sud des Etats-Unis n’ait pas su éveiller l’intérêt des fabricants de ces fragiles cylindres.

Pourtant, la Nouvelle-Orléans et les états avoisinants ont bien eu leur dose de musique dans les bouges comme dans les quartiers chics d’ailleurs. Toujours est-il que la musique jouée dans la Cité du Croissant n’a pas intéressé ces fabricants de disques avant 1925. C’était peut-être trop loin des grandes villes industrielles «sérieuses» comme New York ou Chicago ou plus probablement, ces musiques de «sauvages» n’auraient pas assuré assez de ventes ailleurs que dans ces territoires du Sud profond. Quelques studios itinérants verront néanmoins le jour dans les années vingt, mais pour l’heure, nous n’avons pratiquement que des enregistrements réalisés en majeure partie dans les studios new-yorkais de la Victor Talking Machine Company. Certes, les premiers enregistrements manquent un peu de souplesse, mais faute de pouvoir avoir les témoignages d’époque de la Nouvelle-Orléans, de Saint-Louis, de Sedalia et autres centres où le Cake-walk et le Ragtime ont sévi, il faudra s’en contenter. Il faut remarquer que New York possédait également des orchestres, mais plutôt militaires qui paradaient allègrement dans les larges avenues de la ville, ainsi que des formations plus réduites qui se contentaient de donner des concerts sous les kiosques ou accompagnaient les troupes de comédiens ambulants, ces fameux Minstrels. Les parades de rues nonchalantes, colorées et non moins rythmées de la Nouvelle Orléans étaient inconnues dans les autres régions des Etats-Unis, ce qui peut expliquer l’étonnement quant à l’image que l’auditeur se fait des balbutiements du Ragtime réunis dans ce coffret. Qu’à celà ne tienne! Le Cake-walk qui finit le siècle précédent et commence le nôtre est le lien entre les rythmes ternaires d’origine européenne et explique le passage aux rythmes à deux et quatre temps. C’est vraiment la source populaire du Ragtime, voire sa source africaine, et par delà, se trouve proche parent du blues.

Les huit premières faces de cette anthologie sont des Cake-walks enregistrés entre 1898 et 1905. Présentés d’une manière chronologique, les morceaux réunis ici témoignent de la rapidité avec laquelle les compagnies anglaises se sont intéressées au Cake-walk et au Ragtime, témoins les titres enregistrés par Olly Oakley (né Joseph Sharpe, il changea son nom grâce à la loi anglaise Deed Poll) qui était banjoïste et également musicien de concert du circuit des music-halls de Londres et des environs. Il le restera d’ailleurs jusqu’à sa mort en 1943. Egalement anglais, I’ll Dance ’Till De Sun Breaks Down donne un bel exemple de composition orchestrale non-américaine par Archibald Joyce, chef d’un des premiers orchestres anglais à connaître les honneurs du phonographe. Nous avons inclus également deux autres interprétations d’origine britannique au xylophone (ou au dulcimer), Alabama Skedaddle (qui est en fait une schottisch!) et Ragtime Frolics, interprétés par William Ditcham et Mr. R. White. Cependant, une composition de l’Américain Charles L. Johnson, un des plus prolifiques auteurs de Ragtime, trouve ici dans Dill Pickles - Hot Stuff Ragtime une interprétation tout à fait intéressante par un orchestre anglais composé de militaires. Il est à noter, pour les puristes du jazz qui viendront bien après ces années glorieuses du Cake-walk et du Ragtime naissant, que l’adjectif «hot» est apparu très tôt (Hot Time In The Old Town Tonight - 1896 -, Hot-Foot Sue - 1897 -, Hot Stuff (A Negro Oddity - 1899), précision apportée par notre ami anglais Steve Walker. En France, la mode du Cake-walk dura de 1900 à 1906 environ, époque à laquelle on trouve la présence d’orchestres au célèbre Luna Park.

Bien sûr, ces orchestres ne se contentaient pas de jouer les Cake-walks à la mode, et un examen approfondi des discographies de ces orchestres nous montre que seule, la Musique de la Garde Républicaine enregistra Le Vrai Cake-Walk, composition du Français Duquin (d’après une photographie, cette formation comptait 68 membres parmi lesquels François Combelle et un certain Jacquemont qui seront les pères de deux saxophonistes célèbres dans les années 30 et 40, Alix Combelle et Georges Jacquemont, dit Brown). Selon qu’on a affaire à des orchestres militaires réguliers (Sousa’s Band), à des formations de studio (Metropolitan Orchestra, Victor Dance Orchestra) aux musiciens souvent recrutés parmi les membres des orchestres de Sousa et d’Arthur Pryor d’ailleurs, à de moyennes formations non identifiées ou à des groupes de Minstrels comprenant chanteurs et instrumentistes, les interprétations sont toutes différentes. Il est à noter cependant que l’interprétation du Cake-Walk (plage 5) par les Victor Minstrels, est l’une des plus anciennes tentatives d’enregistrement de la musique des Noirs selon la lettre et selon l’esprit. Le temps passant, le Cake-walk originel se trouve peu à peu remplacé par le Ragtime orchestral. Les orchestres réunis ici, notamment le Victor Military Band avec ses Alexander’s Ragtime Band (qui n’est d’ailleurs pas un rag quant à la structure du morceau!) et son Slippery Place Rag rendent compte de ce glissement du Cake-walk vers le Ragtime mais il faut préciser que ces formations n’étaient pas spécialisées dans le Ragtime, et émaillaient leurs prestations de two-steps, d’intermezzi, de marches, de polkas, de schottisches et de valses, témoin ce très rare Anona, enregistré sur disque monoface APGA par l’énigmatique Orchestre APGA, pseudonyme maison d’un orchestre non identité d’ailleurs. Ce morceau est intitulé «Intermède» (soit Intermezzo) et présente toutes les caractéristiques du Cake-walk/Ragtime, avec thème doublé et trio dans un autre ton. C’est bien intentionnellement que nous avons inclus ici une schottisch et un intermezzo, pour montrer dans quel état d’esprit musical les musiciens d’alors évoluaient.

Deux des grands moments de cet album sont les interprétations de l’Europe’s Society Orchestra, Too Much Mustard et surtout Down Home Rag dont les accents vigoureux, menés par le batteur Charles «Buddy» Gilmore et une mise en place musicale excellente, témoignent de ce qu’on trouvait de mieux à cette époque à New York, un Ragtime bien au point, mais à qui il manque un petit quelque chose qui en ferait du jazz. Quant à la présence de That Moaning Saxophone Rag, interprété par l’équipe de blancs The Six Brown Brothers (six saxophonistes dirigés par Tom Brown), c’est leur seul enregistrement qui puisse se réclamer du Ragtime, cet orchestre étant surtout spécialisé dans des interprétations burlesques de grands airs d’opéra.Quelques faces de Ragtime au piano ont été enregistrées à l’époque. Il ne nous reste que quelques disques et surtout des rouleaux perforés dont l’interprétation manque des nuances que seules les techniques modernes d’enregistrement auraient pu capter. Et comme ce recueil est dévolu à la musique orchestrale, c’est la raison pour laquelle on ne trouvera ici aucun solo de piano, en particulier pas un seul rouleau perforé de Scott Joplin, certainement le plus grand des compositeurs de Ragtime. Il fallait avant tout montrer que le Ragtime n’était pas uniquement issu des salons bien fréquentés comme on a tendance à penser, mais était, à travers le Cake-walk la continuation de l’expression des danses et réjouissances du peuple Noir qui nous amènera progressivement au jazz proprement dit.

© FRÉMEAUX & ASSOCIÉS SA, 1997.

english notes

FROM CAKE-WALK TO RAGTIME

1898-1916

If the twentieth century is no doubt characterized by the manifestation of a rhythmic music, jazz, with wild accents and which seems somewhat disorderly, at least at the beginning, if we do not know the very significance of the word (does it come from French word jaser - to chatter -, widely used in Louisiana and in harbours where culture brought many modifications in the local language, or from black American slang «jass or jazz», giving a certain sexual connotation?), it clearly appears that numerous previous influences determined the naming of jass or jazz, the music played in New Orleans cabarets and in the streets. Among these influences, some consider, by purism or even by racialism (or non racialism!), that the only origin of the word jazz is to be found in African songs, but this is an oversimplification. We must not forget that jazz originated not only in New Orleans, but in every place where coloured men lived next to white men. In the beginning, jazz came in the form of religious songs, negro spirituals and gospels, brass-bands, minstrels, ballads, European orchestral music, Cake-walk, Ragtime, Creole songs, work songs, Blues and African rhythm. Ragtime seems to be the precise connection between European music of the nineteenth century and the music of Negroes. As noted by E. Berendt in his book «Das neue Jazzbuch» in 1963: «on the other hand, Ragtime, by its structure, bears some resemblance to nineteenth century European piano music, the classical minuet for example. It often consists of several successive musical units, both juxtaposed and interlinked, a little as in the waltzes of Strauss. All the vital ingredients of nineteenth century piano music - as found in Schubert, Chopin, Liszt, as well as in the marches and polkas of the time - recur in Ragtime, but with a more pronounced and dynamic rhythm, as revisited by Negroes».The Ragtime Story itself was wonderfully narrated by American experts Rudi Blesh and Harriet Janis in their book «They All Played Ragtime» published in 1951 where they explain the black origin of true Ragtime in speakeasies and joints in Sedalia and in Saint-Louis (Missouri) where frantic dances like Cake-Walk were practised during the Reconstruction Days after the Civil War, during the pioneers era which followed and lastly, with the so-called emancipation of coloured Americans.

These Cake-Walks were mainly played on the banjo - those with four strings used by Negroes - during the numerous parties organized mainly by negro slaves, and also on the piano while this dance was in fashion. Because amongst the Negroes, some had friends who had the opportunity of learning music, and therefore, had the possibility of learning the piano, which was reserved for the Whites. Thanks to discarded wind instruments from the Army, the Negroes were able to transpose Cake-Walks on cornets, trombones, saxophones, clarinets, flutes, piccolos, helicons (transformed into sousaphones by bandleader John Philip Sousa), and form brass bands in town districts, or like Louis Armstrong, who learnt these instruments in children’s institutions.Ragtime was really in fashion from 1897 to 1917 and was subject to change in style through its differents interpreters. In early Ragtime, the majority of black musicians did not bring what the more erudite amongst them assimilated in hearing classical concerts or operas. The rough syncopation will come later, bringing a certain evolution in the style. Finally, it is evident that this typically Negro-American style of music became a piano style. With all this history, Ragtime is an extremely codified style, with very precise rules and, as serious music, cannot be improvised. Of course, some derogations can occur, and, like Johann-Sebastian Bach in his time, it is certain that some differences of interpretation could have been noted as time went by. Obviously Ragtime music was eventually published on music sheets, and for this reason, was easily found in different countries such as England and France, and was played in those countries. In Europe, the spirit of this music was protected, but finally some changes were made in the form. Another consequence was the adaptation to other instruments, to the accordion first, then to the banjo and mandoline, both with marked metallic sound, and to the xylophone, piccolo and cymbalum!

Banjo duets were recorded and Ragtime eventually aroused the interest of music composers and bandleaders, known or not, black or white, who themselves added their own touch.The Ragtime spirit was found in popular music and dances. The structure of the tunes was not definite and we had to wait for Scott Joplin to have consistently-built tunes (Original Rags). Before him there existed popular rags of various styles. These rags were sung, played on banjos or on pianos, and of course, were danced to. These rags originally were issued from plantation songs orally transmitted, but more surely from the Minstrels repertoire. Those Minstrels were White comedy artists, black-faced to give an exotic vision. Traces are found from as early as 1827, at least. This kind of show was very successful and had a fantastic development. The emphasis of the show concentrated on the characteristics of the «good ol’ Negro», the «Nigger», the popular stereotype of the slave, with the accent put on his naivety, his hesitant speech, his laziness and his taste for dancing. These shows were racist, but it did not occur to the gentry, because the idea was in the minds at that time. It was before the Civil War. Nevertheless, the contrary existed: White-faced Blacks were performing in shows, offering the black and white audience a burlesque imitation of their nature! The music was mainly based on the 32 bars AABA structure (first strain of eight bars doubled - A - and a second different strain of eight bars - B - and to finish, the first strain of eight bars A). This structure was to be found in classical jazz later. The popularity of Minstrels did not stop at the end of the century. Many years later, Al Jolson was to sing Swanee (by George Gershwin) in the first singing motion picture in 1927, the Jazz Singer, where he featured as a Negro, with lips coloured red and eyes underlined in white. As he was a Russian Jew, he finally gave honours to an art which was not his.

The Cake Walk was indispensably bound to the just born Ragtime and was an extroverted and syncopated music accompanying dance contests for those in a low-income in black quarters. The price given to the winner was indeed an enormous cake made for the occasion, hence the name Cake-Walk. In a way, it was the most visual and important entertainment capable of communicating the music to the general public. The term Cake-Walk itself first appeared in «Harper’s Magazine» in 1879. Originally coming from the South of the United States, the Cake-Walk spread to the Eastern towns, then to Europe, mainly to France where the enormous concert band directed by the celebrated King of the March, John Philip Sousa performed in early 1900. In those days, the famous Georgia Camp Meeting, written by Kerry Mills, was an appreciated hit amongst black and white people in America, and following the success of Sousa, whose music was called in France Ragtime, the great impressionnist music composer Claude Debussy named one of his compositions The Golliwog Cake-Walk (in Children’s Corner Suite). He also composed a tune named Ménestrels (Minstrels), which gives us the proof of what he could have seen and heard in the very popular shows given by black-faced white artists. In those days, such shows were not felt to be racialist; the white audience accepted them as joyful, harmonious and living shows, whilst Negroes saw them from the theaters’ tin roofs or from the outside of the circuses with a sentiment of indifference or defiance. A good idea of what could be heard in the nineties is represented in the oldest record of the present album «Eli Green’s Cake-Walk», cut in 1898 for the Berliner Company by two banjo players Cullen and Collins, well known both as Minstrels and concert artists. We were at the very beginning of the phonograph era. Although the first cylinders were born some years previously, it would seem that this music from the South of the United States was unable of arousing interest from the record companies. However, New Orleans and the Southern States had no shortage of music in the speakeasies and in the affluent quarters. So, it must be admitted that this music played in Crescent City did not interest record companies before 1925. New Orleans was certainly too far from the big «serious» cities such as New York or Chicago.

More probably, the music played southside was not of sufficient quality to interest Northern buyers. Some itinerant studios were to be brought down there in the twenties but, for the moment, we have only recordings made in New York for the Victor Talking Machine Company. The very first recordings are indeed lacking in bounce, but we have to put up with them, as we haven’t any musical testimony from New Orleans, Saint Louis or Sedalia, and everywhere that the Cake-Walk and Ragtime were performed. We have to remark that some bands often played in New York. These rather military bands played in large avenues, and some smaller ones played on bandstands or accompanied Minstrel shows. The nonchalant, colourful and rhythmic street parades from New Orleans were unknown elsewhere, so don’t be astonished when hearing the tunes in the present album! Anyway, the Cake-Walk of the late nineties and beginning of our century is a link between the European ternary rhythms and could explain why they became two-two and four-four beats. It is really the popular origin of Ragtime, even with its African roots, and of course, it could be considered as very close to the blues.The first eight numbers of this selection are Cake-Walks recorded between 1898 and 1905. They are presented here chronologically and show how quickly the English record companies became interested in Cake-Walk and Ragtime, as we can notice with the tunes recorded by Olly Oakley (born Joseph Sharpe, he changed his name thanks to the Deed Poll law), who was a banjo player and also a London music-hall concert musician.

He was to remain so until his death in 1943. I’ll Dance ’Till De Sun Breaks Down, an English tune composed by bandleader Archibald Joyce, gives a good example of non-American compositions. We have included in this selection two other British interpretations played on the xylophone (or dulcimer), Alabama Skedaddle (a schottische in fact!) and Ragtime Frolics, played by William Ditcham and Mr. R. White. With Dill Pickles - Hot Stuff Ragtime, a composition by the American composer Charles L. Johnson, we have an interesting example of an English military band. The jazz purists could notice that the adjective «hot» was used in the very first years of the phonograph (Hot Time In The Old Town Tonight - 1896 -, Hot-Foot Sue - 1897 -, Hot Stuff (A Negro Oddity) - 1899), as noted by our English friend, Steve Walker. In France, Cake-Walk was in fashion roughly from 1900 to 1906, a time when we found brass bands in the famous Luna Park in Paris. These orchestras didn’t always play Cake-Walks and a serious discographical research shows that only the Garde Républicaine orchestra recorded Le Vrai Cake-Walk (Real Cake-Walk), a composition by the French composer Duquin (as seen in a photograph, this band was composed of 68 musicians. Amongst them we can recognize François Combelle and a certain Jacquemont, who were to be the fathers of the celebrated jazz saxophone players Alix Combelle and Georges Jacquemont, known as Jacquemont-Brown). All the interpretations of Cake-Walks are different, either they are played by regular military bands (Sousa’s Band), or by studio orchestras (Metropolitan Orchestra, Victor Dance Orchestra), with musicians taken in Sousa’s and Arthur Pryor’s bands, or by smaller bands, or Minstrels groups. However, we can note that the interpretation of Cake-Walk (track 5) by the Victor Minstrels is one of the black music oldest ones, with all feeling and spirit. As time went by, the original Cake-Walk was gradually replaced by orchestral Ragtime.

All the bands in this album like the Victor Military Band, give a good example of that change from Cake-Walk to Ragtime, i.e. Alexander’s Ragtime Band (which is not a Ragtime) and Slippery Place Rag. These bands were not specialized in Ragtime and often played two-steps, intermezzi, marches, polkas, schottisches, and waltzes, as we can hear in the very rare item Anona, recorded on a very rare single sided record by the enigmatic band APGA, a pseudonym for the record company APGA. This item is an intermezzo and presents all the characteristics of Cake-Walk / Ragtime, with a doubled theme and trio in another key. We included these schottisch and intermezzo to show in which condition the bands played in those days.The most interesting tunes in this album are Too Much Mustard and Down Home Rag, both played by the famous Europe’s Society Orchestra, led by drummer Charles «Buddy» Gilmore. An excellent drive is given in these sides and this can testify to what was the best in those days in New York, a good Ragtime, quite jazzy. A good example of Ragtime by the white band The Six Brown Brothers (specialized in burlesque operatic music) is given by That Moaning Saxophone Rag, the only Ragtime record by this band.Some piano Ragtime sides were recorded during that period. There only remain a few records and particularly piano rolls whose interpretation shows a lack of nuances that could have been given by modern recording techniques. As this album is devoted to orchestral music, we have neither included here piano solos nor any Scott Joplin’s piano rolls, Scott Joplin no doubt being the greatest Ragtime composer. Our main intention was to show that Ragtime was not only issued from well frequented places as one may tend to believe, but was, through Cake-Walk, the continuation of the negro dances which were to give us jazz itself.

© FRÉMEAUX & ASSOCIÉS SA, 1997.

DISQUE 1 / RECORD 1

01. ELI GREEN’S CAKE-WALK (Sadie Koninsky) 2’07Duo de banjo / Banjo duet par / by Joseph Cullen & William Collins, acc. par / by un inconnu / unknown (p). New York, Mai/May 1898 (Berliner 485).

02. Cake-WALK (anonyme/anonymous) 1’42Orchestre anonyme / Anonymous orchestra. Prob. New York, 1900. (Victor test)

03. SMOKY MOKES (Abe Holzmann) 1’28Metropolitan Orchestra : 2 cnt; 1 tb; 1 flûte; 1 piccolo; 1 violon/violin; p; saxhorn-ténor/tenor-horn; sousaphone; dr. New York, 28 septembre/September 1900 (Victor 271).

04. WHISLING RUFUS (Kerry Mills) 1’43Sousa’s Band : Personnel collectif/Collective personnel : Walter B. Rodgers, Henry Higgins, Rouss Millhouse, Herman Bellstedt, Herbert L. Clarke (cnt); Arthur Pryor (tb solo, assistant conducteur/co leader); Mark Lyon; Edward Williams (tb); A.P. Strengler, Louis H. Christie (cl); Darius Lyons, John S. Cox, Marshall P. Lufsky (fl. picc); Simon Mantia (euphonium); plusieurs saxhorns-ténors/several tenor-horns; Herman Conrad (sousaphone); S.O. Pryor (dr); John Philip Sousa (cond.), prob. Philadelphia. 3 octobre/October 1900 (Victor 361).

05. THE CAKE-WALK (anonyme/anonymous) 2’44(Cake Walk In The Sky - Eli Green’s Cake Walk - At A Georgia Camp Meeting - Happy Days In Dixie). The Victor Minstrels. Master of ceremonies : Len Spencer. Unidentified personnel & singers. New York. 13 décembre/December 1902 (Victor 1828).

06. WHISTLING RUFUS (Kerry Mills) 2’26Banjo solo par/by Olly Oakley. Landon Ronald (p). Londres/London. 12 mars/March 1903 (Gramophone Concert Record GC-6374 - Matrice/Matrix 3274-b).

07. (UNIDENTIFIED) CAKE-WALK (anonyme/anonymous) 1’43Orchestre anonyme/Anonymous orchestra, ca., New York, 1903 (Zonophone U.S. test 17 cm/7”.)

08. CAKE-WALK IN THE SKY (Ben Harney) 3’42Victor (Dance) Orchestra: Walter B.?Rodgers (cnt, ldr); Emil Keneke, Walter Pryor (cnt); O. Edward Wardwell (tb); Louis H. Christie, A. Levy (cl); Darius Lyons (fl, picc); Arthur Trempte (ob); Charles D’Almaine, Theodore Levy (vn); Frank E. Reschke (as, vn); Herman Conrad (sousaphone); S.O. Pryor (dr). New York, 10 avril/April 1905 (Victor 31412 - Matrice/Matrix 2461-1).

09. SAINT-LOUIS TICKLE (Barney & Seymour) 3’01Ossman-Dudley Trio : Vess L. Ossman (bjo); Audley Dudley (mandoline); Roy Butin (harp-g).New York, 24 janvier/January 1906 (Victor 16092 - Matrice/Matrix B-3037-2).

10. DIXIE GIRL (J. Bodewalt Lampe) 2’11Ossman-Dudley Trio : même date et personnel que dessus/Same date and personnel as above.(Victor 16667 - Matrice/Matrix B-3037-2).

11. LE VRAI CAKE-WALK (Duquin) 2’18Musique de la Garde Républicaine. Personnel possible/Possible personnel : Delfosse, Bernard, Lachanaud (cnt); 2 tb; Boisne, Jacquemont, Stenosse (fl, picc); Dufay, Paradis, Pélissier (cl); Lelièvre, François Combelle (sax); 2 tenor-tubas; soubassophone/sousaphone; dr; Gabriel Parès (dir); E. Strady (cond.). Paris, ca, 1906 (G&T GC-30343 - Matrice/Matrix 1707 PI).

12. ANONA (Vivian Gray) 3’23Orchestre APGA. Personnel non identifié/Unidentified personnel : 2 cnt; 1 tb; 1 piccolo; 2 cl; alto-saxhorn; tenor sax-horn; tuba; woodblocks. Paris, ca, 1906. (APGA 150.171).

13. A BUNCH OF RAGS (V.L. Ossman) 2’16Vess L. Ossman (banjo solo), acc. par/by un inconnu/unknown (p). New York, 5 octobre/October 1908 (Victor 16667 - Matrice/Matrix 6508-1).

14. THE BUFFALO RAG (Tom Turpin) 2’05Vess L. Ossman (banjo solo), acc. par/by Theodore Morse (p).New York, 2 mars/March 1909 (Victor 16779 - Matrice/Matrix 6848-1).

15. ALEXANDER’S RAGTIME BAND (Irving Berlin) 2’54Arthur Collins, Byron G. Harlan (vcl), avec orchestre non identifié/with unidentified orchestra. New York, 7 juin/Une 1911 (Columbia-Rena 1868).

16. ALABAMA SKEDADDLE (Edward Hesse) 2’33William Ditcham (xylophone solo), avec orchestre non identifié/acc. by unidentified band. Londres/London, ca.October 1910 (Bell Disc 311 - Matrice/Matrix 2496).

17. ALEXANDER’S RAGTIME BAND (Irving Berlin) 2’36Victor Military Band : Walter B. Rodgers ou/or Theodore Levy (cnt, ldr); Emil Keneke (cnt); Frank Schrader (tb); J. Fuchs (cnt, saxhorn alto/alto-horn); Otto Winkler, H. Reitzel (saxhorn alto/alto-horn, saxhorn ténor/tenor-horn); Louis H. Christie, A. Levy (cl); Clement Barone (fl, picc); Herman Conrad (soubassophone/sousaphone); William H. Reitz (dr). New York, 27 septembre/September 1911 (Victor 17006 - Matrice/Matrix 11027).

18. SLIPPERY PLACE RAG (P.M. Hacker) 2’47Victor Military Band : même formation et date que dessus/Same personnel and date as above. New York, 27 septembre/September 1911 (Victor 17006 - Matrice/Matrix 11028-2).

DISQUE 2 / RECORD 2

01. BLACK DIAMOND RAG (Henry Lodge) 2’47Prince’s Orchestra. Charles A.?Prince (dir); Bohumir Kryl, Vincent Buono (cnt); Leo Zimmerman (tb); Thomas Hughes (cl); Marshall Lufsky (fl, picc); Charles d’Almaine, Walter Biedermann (vln); alto-horn; tenor-horn; sousaphone; Edward Rubsam, Howard Kopp (dr). New York, 12 février/February 1912. (Columbia A-1140 - Matrice/Matrix 19758-1).

02. STOMP DANCE (J.I. Stewart) 2’34Victor Military Band. Personnel comme 17-18/Personnal as for 17-18. New York, 12 mars/March 1912. Victor 17508.

03. THAT MYSTERIOUS RAG (Ted Snyder) 2’42Robert Carr, Jack Charman, Herbert Cove (vcl); avec/with Olly Oakley (bjo) et pianiste non identifié/and unidentified pianist. Londres/London. Mai/May 1912. (The Winner 2142 - Matrice/Matrix 3117 - Control 285).

04. GRIZZLY BEAR (George Botsford, Irving Berlin) 2’50Jack Charman, Walter Miller (= Stanley Kirkby) (vcl) avec/with Olly Oakley (bjo) et pianiste non identifié/and unidentified pianist. Londres/London. Mai/May 1912. (The Winner 2142 - Matrice illisible/illegible matrix - Control 285).

05. DILL PICKLES - HOT STUFF RAGTIME (Charles L. Johnson) 2’56Empire Military Band : Beka Studio orchestra. Julian Jones (dir) : W.W. Donovan (cnt); cnt; 2 tb; 2?cl; fl; picc; basson/bassoon; saxhorn alto/alto-horn; saxhorn ténor/tenor horn; soubassophone/sousaphone; dr. Londres/London. Avril/April 1912 (Beka 555 - Matrice/Matrix 41552).

06. RAGTIME FROLICS (anonyme/anonymous) 3’09Mr R. White (= Billy Whitlock) (xylophone solo), avec orchestre non identifié/with unidentified orchestra. Londres/London. Octobre/October 1910. (Favorite Records 1-64037 - Matrice/Matrix 4164-t).

07. I’LL DANCE TILL DE SUN BREAKS THROUGH (Archibald Joyce) 3’47Joyce’s Orchestra. Archibald Joyce (dir), orchestre inconnu/unidentified orchestra. Londres/London, 7 mars/March 1912 (G & T 0743 - Mx AL-6144-f).

08. OH! THAT YANKIANNA RAG (Melville Gideon) 3’07Orchestre Tzigane du Volney. Jean Lensen (vn, ldr); 2 vn; vla; vc; cymballum; p; sb; dm. Paris, ca. Septembre/September 1912 (Gramophone GC-30729 - Matrice/Matrix 15506u).

09. BACCHANAL RAG (Louis Hirsch) 2’46The Peerless Orchestra. Eli Hudson (dir) (personnel collectif/Collective personnel) : Charles Smith, Frank Kettlewell. Henry Godard (cnt); Jesse Stamp, ... Atherley, ... Mayhew (tb); Robert MacKenzie, Frank Hughes (cl); Gilbert Barton, W.E. Gordon-Walker (fl. picc); Arthur Foreman (ob); Edwin Hinchcliffe (bsn); Jean Bobbe, Ernest Lawrence (vln); Pietro Nifosi (cello); brass-bass; E.W. Rushforth (dr). Londres/London, 3 décembre/December 1912 (Zonophone The Twin 998 - Matrice/Matrix Y-16115-e).

10. TOO MUCH MUSTARD (Cecil Macklin) 3’47Europe’s Society Orchestra : William “Crickett” Smith (cnt); tb; Edgar Campbell (cl); Tracy Cooper, Georges Smith, Walter Scott (vn); Leonard Smith, Ford T. Dabney (p); 5 bjo/mandolines; Charles “Buddy” Gilmore (dr); James Reese Europe (cond). New York, 29 décembre/December 1913. (Victor 35359 - Matrice/Matrix 14246-1).

11. DOWN HOME RAG (Wilbur C. Sweatman) 3’19Europe’s Society Orchestra : même formation et date que dessus/Same personnel and date as above. (Victor 35359 - Matrice/Matrix 14247-2).

12. YOU’RE HERE AND I’M HERE (Jerome Kern) 2’34Europe’s Society Orchestra : William “Crickett” Smith (cnt); tb; Edgar Campbell (cl); non identifiés/unidentified (fl); baritone-horn; Tracy Cooper, Georges Smith, Walter Scott (vn); Charles Ford (cello); Leonard Smith, Ford T. Dabney (p); Charles “Buddy” Gilmore (dr); James Reese Europe (cond). New York, 10 février/February 1914. (Victor 17553 - Matrice/Matrix 14432-1).

13. CASTLE WALK (J. Europe - F.T. Dabney) 3’12Europe’s Society Orchestra : même formation et date que dessus/Same personnel and date as above. (Victor 17553 - Matrice/Matrix 14434-2).

14. NOTORIETY RAG (K.L. Widmer) 2’51Fred Van Eps Trio : Fred Van Eps (bjo); Felix Arndt (piano); Eddie King (dr). New York. 19 mars/March 1914. (Victor 17601 - Matrice/Matrix 14420-3).

15. THAT MOANING SAXOPHONE RAG (Tom Brown - Harry Cook) 2’05The Six Brown Brothers : Tom Brown (ss, as, ldr); Guy Shrigley (as, ts); James “Slap Rags” White (C-melody sax); Sonny Clap (ts); Harry Cook (bar-sax); Harry Finkelstein (Fink) (bass-sax). Camden, N-J, 20 novembre/November 1914. (Victor 17677 - Matrice/Matrix 15362-3).

16. OPERATIC RAG (Julius Lenzberg) 2’28Joseph Moskovitz (cymbalum solo), acc. par un pianiste non identifié/acc. by an unidentified pianist. Camden, N-J, 4 février/February 1916. (Victor 17978 - Matrice/Matrix 17117-2).

17. RAGGIN’ THE SCALE (Edward Claypoole) 2’40Fred Van Eps (bjo) avec orchestre non identifié/with unidentified orchestra. New York, 1er juin/1st June 1916. (Victor 18085 - Matrice/Matrix 17673-4).

18. TWO-KEY RAG (Joe Hollander) 3’01Conway’s Band. Personnel non identifié comprenant/Non unidentified personnel including : 3 cnt; 1 bugle/flugelhorn; Charles Randall (tb); tb; 4 cl; 1 fl; 1 piccolo, soubassophone/sousaphone; William H. Reitz (dr); Patrick Conway (cond). New York, 10 juillet/July 1916. (Victor 18106)

Remerciements à / Many thanks to : Mark Berresford, Ivan Députier, Michel Marcheteau, Daniel Nevers, Steve Walker.Les illustrations et les photos (X...) viennent de la collection de Steve Walker /. Illustrations and photos (X...) by courtesy of great collector Steve Walker.

CD From Cake-Walk to Ragtime © Frémeaux & Associés (frémeaux, frémaux, frémau, frémaud, frémault, frémo, frémont, fermeaux, fremeaux, fremaux, fremau, fremaud, fremault, fremo, fremont, CD audio, 78 tours, disques anciens, CD à acheter, écouter des vieux enregistrements, albums, rééditions, anthologies ou intégrales sont disponibles sous forme de CD et par téléchargement.)