- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

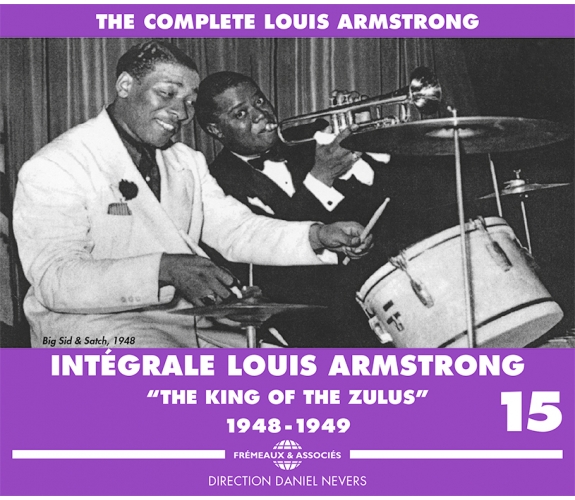

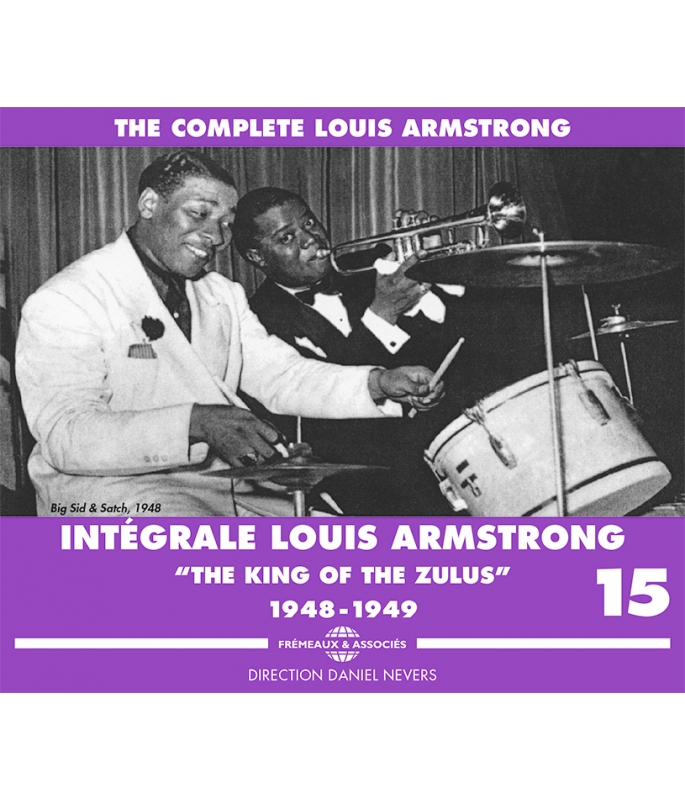

THE KING OF THE ZULUS 1948-1949

LOUIS ARMSTRONG

Ref.: FA1365

EAN : 3561302136523

Artistic Direction : DANIEL NEVERS

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Total duration of the pack : 3 hours 47 minutes

Nbre. CD : 3

THE KING OF THE ZULUS 1948-1949

THE KING OF THE ZULUS 1948-1949

“I first met Louis in Chicago, just after he left King Oliver’s band (…) Nobody could copy him. Some were trying to play the trumpet like he does, but nothing happened… It’s so simple: when he sings a sad song you cry, and when he sings a happy song, you laugh.” Bing CROSBY

The Frémeaux & Associés Complete Series usually feature all the original and available phonographic recordings and the majority of existing radio documents for a comprehensive portrayal of the artist. The Louis Armstrong series is an exception to the rule in that the selection of titles by this American wizard is certainly the most complete as published to this day but does not comprise all his recorded works. Patrick Frémeaux

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Muskrat RambleLouis Armstrong, Jack Teagarden, Earl Hines, Barney BigardEd Ory00:03:551948

-

2Do You Know What It Means To Miss New OrleansLouis Armstrong, Jack Teagarden, Earl Hines, Barney BigardL. Alter00:04:001948

-

3I Cried For YouLouis Armstrong, Jack Teagarden, Earl Hines, Barney BigardA. Lyman00:04:141948

-

4Confessin'Louis Armstrong, Jack Teagarden, Earl Hines, Barney BigardNeiburg00:04:311948

-

5Milenberg JoysLouis Armstrong, Jack Teagarden, Earl Hines, Barney BigardF. Morton00:02:411948

-

6Struttin' With Some BarbecueLouis Armstrong, Jack Teagarden, Earl Hines, Barney BigardL. Hardin00:04:561948

-

7WhisperingLouis Armstrong, Jack Teagarden, Earl Hines, Barney BigardJ. Schonberger00:04:261948

-

8St. Louis BluesLouis Armstrong, Jack Teagarden, Earl Hines, Barney BigardW.C. Handy00:03:351948

-

9Blue SkiesLouis Armstrong, Jack Teagarden, Earl Hines, Barney BigardI. Berlin00:03:161948

-

10Basin Street BluesLouis Armstrong, Jack Teagarden, Earl Hines, Barney BigardS.P. Williams00:03:261948

-

11High SocietyLouis Armstrong, Jack Teagarden, Earl Hines, Barney BigardP. Steele00:03:461948

-

12Someday You'll Be SorryLouis Armstrong, Jack Teagarden, Earl Hines, Barney BigardLouis Armstrong00:03:171948

-

13The One I Love Belongs To Somebody ElseLouis Armstrong, Jack Teagarden, Earl Hines, Barney BigardLouis Armstrong00:03:251948

-

14Jack-Armstrong BluesLouis Armstrong, Jack Teagarden, Earl Hines, Barney BigardLouis Armstrong00:03:301948

-

15TogetherLouis Armstrong, Jack Teagarden, Earl Hines, Barney BigardR. Henderson00:03:281948

-

16I Gotta Right To Sing The BluesLouis Armstrong, Jack Teagarden, Earl Hines, Barney BigardT. Koehler00:02:581948

-

17That's A PlentyLouis Armstrong, Jack Teagarden, Earl Hines, Barney BigardL. Pollack00:03:161948

-

18East Of The Sun (West Of The Moon)Louis Armstrong, Jack Teagarden, Earl Hines, Barney BigardBowman00:02:481948

-

19I Got RhythmLouis Armstrong, Jack Teagarden, Earl Hines, Barney BigardG. & I. Gershwin00:01:521948

-

20I Surrender DearLouis Armstrong, Jack Teagarden, Earl Hines, Barney BigardBarris00:04:201948

-

21Don'T Fence Me InLouis Armstrong, Jack Teagarden, Earl Hines, Barney BigardC. Porter00:03:561948

-

22St. Louis Blues 2Louis Armstrong, Jack Teagarden, Earl Hines, Barney BigardW.C. Handy00:01:381948

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Discussion And Do You Know What It Meansto Miss New OrleansLouis Armstrong, Jack Teagarden, Earl Hines, Barney BigardL. Alter00:05:101948

-

2Discussion And Struttin' With Some BarbecueLouis Armstrong, Jack Teagarden, Earl Hines, Barney BigardL. Hardin00:05:041948

-

3Little White LiesLouis Armstrong, Jack Teagarden, Earl Hines, Barney BigardW. Donaldson00:03:471948

-

4Black And BlueLouis Armstrong, Jack Teagarden, Earl Hines, Barney BigardT.W. Waller00:03:161948

-

5Shadrack When The Saints Go Marchin' InLouis Armstrong, Jack Teagarden, Earl Hines, Barney BigardTraditionnel00:04:481948

-

6Baby Won'T You Please Come HomeLouis Armstrong, Jack Teagarden, Earl Hines, Barney BigardC. Williams00:05:241948

-

7Muskrat Ramble 2Louis Armstrong, Jack Teagarden, Earl Hines, Barney BigardEd Ory00:05:551948

-

8PanamaLouis Armstrong, Jack Teagarden, Earl Hines, Barney BigardW.H. Tyers00:04:261948

-

9Maybe You'll Be ThereLouis Armstrong, Jack Teagarden, Earl Hines, Barney BigardGallop00:05:081948

-

10S Posin'Louis Armstrong, Jack Teagarden, Earl Hines, Barney BigardP. Denniker00:03:561948

-

11Royal Gaden BluesLouis Armstrong, Jack Teagarden, Earl Hines, Barney BigardC. Sp. Williams00:04:401948

-

12Lazy RiverLouis Armstrong, Jack Teagarden, Earl Hines, Barney BigardH. Carmichael00:04:101948

-

13Intro Where The Blues Were Born In N.O.Louis Armstrong, Jack Teagarden, Earl Hines, Barney BigardCappleton00:03:491948

-

14A Song Was BornLouis Armstrong, Jack Teagarden, Earl Hines, Barney BigardD. Raye00:03:301948

-

15King Porter StompLouis Armstrong, Jack Teagarden, Barney BigardF. Morton00:04:171948

-

16Black And Blue 2Louis Armstrong, Jack Teagarden, Earl Hines, Barney BigardT.W. Waller00:03:391948

-

17RosettaLouis Armstrong, Earl HinesE. Hines00:02:551949

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Entretien/Talking : B. Crosby L. Armstrong, J.Teagarden, J.VenutiLouis Armstrong, Jack TeagardenBing Crosby00:05:361949

-

2Panama 2Louis Armstrong, Jack TeagardenW.H. Tyers00:02:301949

-

3Lazy River 2Louis Armstrong, Jack TeagardenH. Carmichael00:02:041949

-

4Lazy BonesLouis Armstrong, Jack TeagardenH. Carmichael00:02:571949

-

5Rockin' ChairLouis Armstrong, Jack TeagardenH. Carmichael00:02:551949

-

6When It's Sleepy Time Down SouthLouis Armstrong, Jack TeagardenL&O René00:01:481949

-

7Panama 3Louis Armstrong, Jack TeagardenW.H. Tyers00:04:231949

-

8Back O' Town BluesLouis Armstrong, Jack TeagardenLouis Armstrong00:05:111949

-

9Pale MoonLouis Armstrong, Jack TeagardenJ.G.M. Glick00:03:511949

-

10Don'T Fence Me In 2Louis Armstrong, Jack TeagardenC. Porter00:04:491949

-

11Body And SoulLouis Armstrong, Jack TeagardenGreen00:04:511949

-

12A Song Was Born 2Louis Armstrong, Jack TeagardenD. Raye00:04:021949

-

13Whispering 2Louis Armstrong, Jack TeagardenJ. Schonberger00:03:421949

-

14Mahogany Hall StompLouis Armstrong, Jack TeagardenSp. Williams00:04:141949

-

15A Hundred Years From TodayLouis Armstrong, Jack TeagardenJ. Young00:04:421949

-

16Blue Skies 2Louis Armstrong, Jack TeagardenI. Berlin00:03:151949

-

17Rockin' Chair 2Louis Armstrong, Jack TeagardenH. Carmichael00:03:171949

-

18The Sheik Of ArabyLouis Armstrong, Jack TeagardenSnyder00:03:171949

-

19Confessin' 2Louis Armstrong, Jack TeagardenNeiburg00:04:561949

-

20Ain'T MisbehavinLouis Armstrong, Jack TeagardenT.W. Waller00:04:181949

CLICK TO DOWNLOAD THE BOOKLET

Armstrong vol 15 FA1365

THE COMPLETE LOUIS ARMSTRONG VOL. 15

INTÉGRALE LOUIS ARMSTRONG

VOLUME 15

“THE KING OF THE ZULUS”

1948 - 1949

DIRECTION DANIEL NEVERS

Louis ARMSTRONG – volume 15

1948… Certes ce n’est pas 1984, mais c’est quand même une de ces années qui, pour le meilleur et l’un peu moins bon, feront date dans la vie et la carrière de Louis Armstrong…

C’est en effet au début de cet an 48 que sa carrière internationale, brutalement interrompue autant pour raisons de santé que d’incompatibilité d’humeur au début de 1935, va prendre un nouveau départ, définitif celui-là. Désormais, il se partagera à presque égalité entre la mère Patrie et le vaste monde qui lui ouvre enfin les bras. Ainsi, au fil des jours, parcourra-t-il la vieille Europe (le seul espace lointain déjà partiellement sillonné jusque là) ; et ce morceau du continent américain situé dans l’autre hémisphère ; et cette Afrique d’où ses malheureux ancêtres furent arrachés de force ; et aussi l’Asie ; et les terres australes… Il ira même, bombardé ambassadeur, jusque de l’autre côté du miroir de fer en des heures de « guerre froide »…

Pour courir le monde et l’admirer (et s’en faire admirer !), Dom Louis Armstrong ne disposait point de quatre dromadaires comme cet autre grand voyageur prénommé Pedro, mais bien d’une solide petite formation de six musiciens (dont lui-même), plus chanteuse/danseuse, baptisée non sans quelque hésitation « All-Stars ». Certes, c’est l’année précédente que le dit groupe avait vu le jour – à la mi-août 1947, au « Billy Berg’s Club », sur le versant californien. En fait, déjà le concert du 8 février 47 à Carnegie Hall (voir volume 12 – Frémeaux FA 1362) avait servi de révélateur : présenté en deux parties, l’une en grand orchestre régulier, l’autre en petit comité, il avait fait réagir un public depuis des années saturé de big bands, en faveur de la seconde formule. Les mois suivants permirent de peaufiner l’option All-Stars, qui semblait arranger tout le monde (sauf, évidemment, les membres du grand orchestre, fatalistes, sentant arriver au triple galop les jours, non de vin et de roses, mais ceux, sombres, de vaches maigres et de chômage !). A la réflexion, on peut même faire remonter le désamour du big band au profit de la formation réduite à ce film de 1946, New Orleans. En rupture de grosse machine, Louis y retrouvait quelques vieux complices des jours tranquilles à Chicago sous la prohibition : Kid Ory, Bud Scott, Barney Bigard, Zutty Singleton, que des copains du cru – en revanche PAS le moindre Bing Crosby à l’horizon !… Evidemment, la crise du grand orchestre de jazz – qui avait tenu le haut du pavé depuis deux bonnes décennies – ne concernait pas que le seul Louis Armstrong. Ils ne mouraient pas tous, mais tous étaient frappés, Ellington, Goodman et Basie compris… Avec un terrain aussi favorable, le All-Stars jouait sur le velours…

Au vrai, les essais 47 de All-Stars étaient tâtonnants, imparfaits. Toujours une bricole qui clochait : un guitariste, un saxophoniste en trop ; un clarinettiste, ou un pianiste, ou un batteur, qui n’étaient pas tout à fait les bons, quel que fût par ailleurs leur talent… Et puis tout à coup, en janvier 48, tout se met en place comme par miracle : le « maillon faible », le sympathique pianiste Dick Cary, qui aimait tant jouer dans cet orchestre-là, doit néanmoins céder le poste au Maître, lui aussi en rupture de big band, celui qui ne faisait qu’un avec Satch’, du temps des Chicago days, Earl Hines, l’homme du « trumpet-piano style » (voir volumes 4 et 5). Et, voyez comme tout tombe à pic : juste au moment de s’embarquer pour le premier Festival de Nice, Alpes Maritimes. Comme sur du papier à musique !…

Il s’en fallut cependant de peu pour que la grande majorité du public – celle qui passe par le truchement du disque – n’entende jamais ce All-Stars initial, idéal, matrice de tout ceux à venir, pour cette simple raison qu’il ne grava aucune galette vouée à la commercialisation. La faute en incombe à la nouvelle grève des enregistrements, moins longue et dure, certes, que celle qui paralysa les studios d’août 1942 à novembre 1944, mais tombant pile au mauvais moment ! Si bien que dans les dernières faces RCA le 16 octobre 47, Hines n’est pas encore arrivé. Et que, pour la copieuse séance suivante mettant le All-Stars en vedette, fin avril 1950 chez Decca cette fois, la santé fragile du batteur Sidney Catlett l’aura contraint à se faire remplacer dès l’été précédent par Cozy Cole. Celui qui fut l’un des deux ou trois batteurs préférés d’Armstrong, grand homme du swing par excellence – qui joua et enregistra également en compagnie de Parker et Gillespie et influença Max Roach –, succomba à une crise cardiaque le 25 mars 1951…

Louis tourna bien quelques disques en 1949, après la grève – dont deux faces avec Billie Holiday en septembre – mais la compagnie préféra le faire accompagner par des groupes de studio plus volumineux, sans rapport avec le All-Stars…

En d’autres termes, si les nombreux concerts et, surtout, les émissions de radio (voire de télévision), n’avaient point judicieusement pris la relève, le sextette des débuts nous manquerait grandement. Ce qui n’est évidemment nullement le cas, puisque ces radios sont légions ! Tout commence, on l’a vu, avec Nice (22-29 février), se poursuit avec la « Salle Pleyel » (2-3 mars - volume 14) et continue après le retour au pays fin mars 48. S’il n’était pas question d’inclure la totalité de ces enregistrements dont le répertoire varie peu et qui se recoupent énormément, on a opéré un choix des plus larges, en tenant surtout compte de la qualité technique – celle de la musique demeurant quant à elle d’un niveau fort élevé. C’est ainsi le cas des copieuses sessions de Philadelphie, où le All-Stars se produisit longuement à la fin du printemps puis de l’été de cette année-là (CDs 1 et 2). Il est vrai, comme le notent certains chroniqueurs, que le public se montrait ravi de retrouver enfin Louis Armstrong, pour la première fois depuis des lustres dans un contexte de jazz… Non, on ne rêve pas : c’est bien ainsi que les choses sont formulées en Amérique à l’époque ! Mais alors, que faisait-il donc, Louis, durant toutes ces années big band ? Avait-il ignominieusement trahi la cause en se jetant à corps perdu dans le chant grégorien ? Etait-il tombé dans les rets des tendres et dangereuses sirènes du baroque ? Avait-il succombé à la pernicieuse tentation de la valse ? S’était-il mis à la remorque de l’opérette viennoise, de la mélodie française ou des Maîtres de la dodécaphonie ? Il ne nous paraît point… Voilà bien ce qui arrive quand les mots n’ont pas partout le même sens ! Et c’est précisément ce qui se passe en ces temps de chambardement, de recomposition… Songeons qu’exactement au même moment, au même endroit, un Charlie Parker (l’autre soliste de génie) affirme froidement que sa musique et celle de ses complices ne plonge point ses racines dans ce qu’il est convenu d’appeler « jazz ». Reste à savoir, évidemment, ce qu’il est convenu d’appeler « jazz »…

Avant les engagements de Pennsylvanie et un concert le 3 mai à Carnegie Hall dont nous ne possédons pas les échos, le All-Stars fit en avril un petit crochet par l’Illinois et participa à au moins une émission de la NBC dont nous sont parvenus de nouvelles versions de Muskrat Ramble et Do You Know What it Means to Miss New Orleans… Une composition bien connue de Kid Ory ayant largement le droit de vote (premiers pas sur la cire de ce facétieux rat musqué par les Hot Five, le 26 février 1926 chez OkeH – voir volume 3) et une chose nettement plus récente, spécialement conçue pour le film New Orleans (premier enregistrement commercial, le 17 octobre 1946 chez RCA – voir volume 12). Ainsi donc, cette alternance entre thèmes déjà anciens, connus de tous, et morceaux nouveaux – interprétés néanmoins dans un esprit similaire – est-elle déjà bien en place dans la démarche du All-Stars, ce que d’ailleurs prouvaient déjà les concerts de Nice et Paris. Pour être tout à fait juste, faut-il préciser que dans le dosage les bons vieux standards, ceux que le public ne manque jamais de réclamer, l’emporteront assez rapidement sur les airs plus récents, même si parfois un jeune « tube » pourra connaître un succès inespéré : voir C’est si bon ou La vie en rose…

Bien sûr les disques – surtout avec l’arrivée du microsillon et de la notion d’albums conçus autour d’un thème – offriront une plus grande variété, mais ils seront souvent réalisés avec des formations de studio, sans l’orchestre régulier. De toute façon, pour l’heure, la grève s’éternise et certaines firmes phonographiques sauront mettre à profit cette si fâcheuse inaction imposée en modernisant leur technique. Notamment en faisant l’emplette de ces belles grosses machines toutes neuves communément appelées « magnétophones », permettant de substituer avantageusement à la gravure directe l’enregistrement sur bandes dites magnétiques. Pas les dinosaures du disque évidemment, qui attendront tranquilles, cordons de la bourse hermétiquement bouclés, 1950-51. Plutôt les boîtes petites et moyennes, genre Capitol, par exemple… Dommage que Louis Armstrong n’ait guère enregistré pour Capitol ! En tous cas, au printemps de 1948, des disques, pas la peine d’y compter !

Ainsi, d’aventures en aventures, de Muskrat Ramble en Do You Know What it Means et Where the Blues Were Born (même film !), de Royal Garden Blues, High Society et Basin Street Blues en A Song Was Born et Mop Mop, de Panama ou encore Struttin’ With Some Barbecue en East of the Sun et Don’t Fence Me In, en passant par des choses un peu plus rares, telles Milenberg Joys, King Porter Stromp, Little White Lies, Whispering, Together, The One I Love Belongs to Somebody Else, S’posin’… , on ira de Philadelphie (« The Ciro’s” en juin) à Philadelphie (« The Click” en septembre), avec de petits et grands crochets par la Grosse Pomme, la Cité du Vent, celle des Anges, voire celle du Croissant, en fuyant soigneusement la ligne droite, mère de tous le vices… Quant à ces « choses un peu plus rares », il s’agit souvent – pas toujours – de « spécialités » des autres membres du groupe, Big Tea (Basin Street, Baby Won’t You Please Come Home, Maybe You’ll Be There) et Big Sid (Mop Mop), Fatha (East of the Sun, The One I Love, le superbe Pale Moon), Barney (Tea for Two, Body and Soul), Arvell (How High the Moon), Velma (I Cried for You, Together, Don’t Fence Me In, Little White Lies, Blue Skies…)… Le patron ne s’y investit qu’avec parcimonie – voire pas du tout (Pale Moon). Ce qui ne l’empêche nullement de donner magistralement la réplique à Hines sur son cheval de bataille par excellence depuis une bonne quinzaine d’années, sa composition Rosetta (CD 2, plage 17). Comme l’écho des instants de grande création, quand les deux complices jouaient avec leur fabuleux Oiseau du Temps (Weather Bird) à ne plus faire qu’un, près de vingt ans auparavant au jour près…

L’automne et l’hiver 48 se déroulèrent principalement à l’Est, côté new-yorkais, à en juger par les témoignages en notre possession. Témoignages sonores s’entend, car pour ce qui est des émissions de télévision (CBS et WPIX) des 21 et 23 novembre, l’image n’a pas suivi (CD 2, plages 13 à 15)… On note également, à partir de la mi-décembre, un engagement au « Blue Note » de Chicago, concrétisé par des passages en radio sur les chaînes ABC et WBBM (CD 2, plages 16 & 17). Par ailleurs, le 29 (ou le 30) octobre, le All-Stars avait aussi donné un concert dans le cadre des « Dixieland Jubilee » de Gene Norman, au « Civic Auditorium » de Pasadena, Californie. Ces nouvelles moutures de King Porter Stomp, Black and Blue, Royal Garden Blues, Basin Street Blues, That’s my Desire…, en leur temps transcrites sur ces grandes galettes de vinylite (33 tours, 40cm/16’) destinées à la radio militaire (AFRS), dans la série Just Jazz (n° 28, 29, 30, 36, 49, etc…), sont des plus rares et les copies à notre disposition de bien piètre qualité. Que l’on soit cependant assuré que ces versions de thèmes de base du répertoire diffèrent assez peu de celles ici reproduites des mêmes pièces.

Ce séjour à deux pas de La Mecque du cinéma, semble suggérer une nouvelle participation armstrongienne à l’ordre du septième art. En effet, la filmographie de Satchmo et quelques ouvrages traitant du couple jazz & cinéma, indiquent pour l’an 48 un mystérieux Courtin’ Trouble, réalisé par un certain Ford Beebe pour la petite firme Monogram, spécialiste des westerns fauchés, souvent employeuse le jeune John Wayne (un autre « Duke » !) vers 1933-35. On ne sait quels étaient les acteurs et les autres musiciens ni quels morceaux furent exécutés. En 1938 déjà, dans Doctor Rhythm (Paramount) de Frank Tuttle avec Bing Crosby, Louis devait paraître dans une séquence et interpréter The Trumpet Prayer’s Lament. Tout cela fut effectivement tourné, puis… coupé au montage ! A tout le moins possède-t-on quelques photos de plateau. Rien de tel avec Courtin’ Trouble. Ce film est-il seulement sorti ?

Un film qui est bien sorti, lui, à la fin de 1948, c’est A Song Is Born. Mentionné au volume 13, il avait réuni à l’été de 1947 une jolie brochette de jazzmen – Benny Goodman, Tommy Dorsey, Charlie Barnet, Mel Powell, Louie Bellson, Lionel Hampton et bien sûr Satch’ – autour du sympathique Dany Kaye, sous la houlette d’Howard Hawks et du producteur Samuel Goldwin. Pourquoi avoir attendu plus d’un an pour présenter au monde cette réjouissante et swingante pellicule ? Question de droits peut-être, ou problèmes de distribution… Quoiqu’il en soit, si l’on s’en tient à l’usage qui veut que l’on date un film par rapport à sa sortie publique et non en référence à l’époque de son tournage, alors A Song Is Born doit en effet afficher le millésime 1948. Nous avons préféré nous en tenir, comme pour New Orleans, à la chronologie réelle en replaçant les extraits musicaux là où ils doivent se trouver…

Le petit crochet par Chicago et son « Blue Note » dura jusqu’en janvier 49, puis Louis, en brève rupture de All-Stars, fit un saut en Californie, invité de Bing Crosby, ami de longue date, mentionné ci-dessus à propos d’un film de 1938 dans lequel ils avaient failli se retrouver ! Rappelons en passant qu’un autre film de cette période, Pennies From Heaven (1936), donne bien à voir les deux complices… mais pas dans les mêmes séquences (voir volume 7) ! En février 1949, c’est de radio qu’il s’agit. Le plus souvent cheminant avec son compère Bob Hope sur les Road to… – routes d’ici et d’ailleurs du monde entier ! –, fameuse et juteuse série de cinéma, Bing Crosby, aimée vedette de l’écran (malgré de grandes oreilles décollées et une calvitie précoce !), avait aussi ses entrées dans les grandes stations de radio. Maître de cérémonies, il y recevait celles et ceux à la mode du jour, tout en fredonnant lui-même au passage les derniers refrains en vogue… Louis Armstrong, on l’a noté, avait la cote auprès des crooners. Début 1937, Rudy Vallée, déjà préfacier de son livre de souvenirs Swing That Music, lui avait amicalement cédé trois mois durant les commandes de l’émission très populaire qu’il animait depuis des années sur les antennes de la NBC (voir volume 8). Crosby de son côté, ravi de papoter avec lui en toute liberté, ne manqua pas de l’inviter chaque fois qu’il le put. Les émissions antérieures ne nous étant point parvenues, celle enregistrée le 21 février 1949 (diffusion le 16 mars) dans les studio ABC de San Francisco, reste pour nous la plus ancienne. Lors de ce numéro du Philco Radio Show, Bing reçoit la chanteuse Peggy Lee, le violoniste Joe Venuti, un de ses accompagnateurs de prédilection depuis leur rencontre vers 1928-30 chez Paul Whiteman, Jack Teagarden, lui aussi ancien du « Roi du Jazz », et naturellement Louis.

L’enregistrement sur bandes, leur montage aisé, leur diffusion en différé, tout cela autorise à présent davantage de souplesse et d’aisance, de liberté de ton et d’esprit, que les émissions naguère réalisées en direct. Sans parler bien sûr de l’archivage, permettant d’y avoir encore accès aujourd’hui…

Ainsi, après la seule intervention de Peggy Lee dont nous nous passerons – que la dame de nous en veuille point – et une inévitable page de pub, on débouche sur une sympathique conversation au coin du feu entre Bing, Louis, Tea et Venuti, de près de six minutes (CD 3, plage 1). C’est long. Surtout si l’on ne comprend pas (bien) la langue ! Fallait-il pour autant exclure ce moment si décontracté de chaleureuse complicité plus qu’amicale, sous prétexte qu’une traduction simultanée n’était guère commode ? Il ne nous a pas semblé, tant les protagonistes parviennent à donner vie et spontanéité à ce qui, certainement, doit être écrit au moins dans ses grandes lignes. De toutes façons, il est toujours possible de sauter rapidement à la plage suivante ! Plages suivantes consacrées à la musique. Avec au départ Panama, bon vieux cru néo-orléanais dont nous possédons déjà plusieurs versions – deux ici même – mais que Louis n’a toujours pas enregistré commercialement début 1949. Le délicat Lazy River, il l’a en revanche confié à la cire des disques OkeH dès le 3 novembre 1931 (volume 6) et l’on en trouvera des moutures plus récentes avec le All-Stars (ici, CD 2, plage 12). Celle-ci met en valeur, plus peut-être que d’habitude, la richesse du jeu de Teagarden. L’autre « lazy », le langoureux Lazy Bones, délicieuse chanson d’Hoagy Carmichael revendiquant le droit à la paresse, était bien propre à séduire un Bing Crosby et un Louis Armstrong, gros bosseurs l’un comme l’autre. La partie de pêche par ce chaud dimanche d’été a décidément des charmes irrésistibles… Il ne reste plus qu’à tirer l’échelle en s’octroyant une sieste bien méritée au fond des chers vieux Rockin’ Chairs. Carmichael encore…

…Et pendant ce temps, alors que Louis, Bing et leurs copains se la coulent douce à l’ombre de la Golden Gate, la presse, elle, fait son travail. Ainsi ce même 21 février 1949, elle colle le nommé Armstrong Louis à la une de Time Magazine, avec un reportage sur dix colonnes ! Ici, aujourd’hui, cela n’a peut-être l’air de rien. Mais là-bas, en ce temps-là (et même peut-être encore maintenant…). Bel exploit, non ?…

Dans la foulée, le début du printemps 49 fut encore californien pour le All-Stars, avec en mars plusieurs concerts à l’« Hollywood Empire » de Los Angeles, dont de larges extraits reportés une fois encore sur les grandes transcriptions de l’AFRS, série Jubilee – l’une de celles, avec Just Jazz, où l’on glane le plus de jazz. Certaines de ces gravures composent la plus grande partie du CD 3 (plages 6 à 19). En avril le groupe joua au « State Theater » de Cincinnati (Ohio) : quatre concerts, les 21, 22, 26 et 27 avril, dont on connaît la teneur, à défaut d’en posséder les modulations – à l’exception toutefois d’un Ain’t Misbehavin’ du 27, d’une fière puissance mais à la limite de l’audible (plage 20)…

Fin du quinzième épisode ? Pas tout à fait ! En relisant ce qui précède, l’on s’aperçoit qu’il manque quelque chose. Sûrement ce petit détour par la ville natale, la home town tant aimée, New Orleans, depuis longtemps quittée, jamais remplacée dans le cœur du musicien. Il se trouve que là-bas, avec autant de pittoresque qu’à Rio, Venise ou Nice, on célèbre aussi le Carnaval. Ou, plus exactement, le Mardi gras. Les nombreux clubs de la ville organisent les réjouissances, présentent des chars préparés de longue date et sacrent une Reine. L’un d’eux, le « Zoulou » (« Zulu Social Aid and Pleasure Club »), fondé au début du vingtième siècle par des ouvriers noirs, présente lui aussi son char et ses souverains. Les titres de quelques morceaux du cru, Zulu’s Ball ou King of the Zulus, font évidemment référence à cette tradition. Et c’est bien de cela qu’il s’agit : pour l’an 1949, c’est Louis Armstrong qui est sacré Roi des Zoulous, bien qu’il soit une célébrité ne résidant plus en ville depuis des lustres ! La une de Time Magazine et le papier l’accompagnant ne sont naturellement pas sans rapport avec l’évènement, dont les photos seront publiées dans toute la presse… Ravi, prenant à cœur ce qu’il considère comme un grand honneur, Satch’ joue son rôle avec délectation, maquillé de la tête aux pieds, méconnaissable, défilant sur le char, buvant du champagne et lançant des noix de coco aux spectateurs comme le veut la coutume. Sa Reine a nom Bernice Oxley et ce jour-là, mardi 1er mars, il reçoit des mains du maire les clefs de la ville dont il est fait citoyen d’honneur. En outre, il retrouve Peter Davis, le monsieur qui, trente-quatre ans plus tôt, le poussa vers la musique en le prenant dans la fanfare des jeune détenus du « Waif’s Home », d’abord comme tambourin, puis comme… clairon ! C’est cependant sur sa trompette Selmer que le 27 février, Louis à peine débarqué, avait donné au « Booker T. Washington Auditorium » un concert diffusé sur la chaîne WDSU. Shoe Shine Boy et Royal Garden Blues étaient au programme…

Comme il se doit, cette façon quelque peu bouffonne certes, mais au fond bien innocente de se donner en spectacle, ne fut pas du goût de tout le monde. Les amateurs de jazz, musique sérieuse s’il en est, et les responsables politiques noirs, ne manquèrent point de lui tailler quelques vêtements pour l’hiver, voire de le traiter de débile ! Armstrong n’en eut cure : sans le moindre calcul, il avait réussi une remarquable campagne publicitaire, le propulsant enfin au rang de star. Et en plus, le plaisir. Surtout le plaisir d’être reconnu avec tout le tra-la-la de rigueur là où il souhaitait l’être depuis ce jour de 1922, quand il était parti conquérir la gloire ailleurs – depuis toujours au fond… Louis Armstrong Roi des Zoulous, dans la peau de cet autre qui, voici très très longtemps, clamait bien haut préférer être le Premier dans ce trou paumé du pays des Parisis que le Second dans Rome.

Daniel NEVERS

© 2018 Frémeaux & Associés

Remerciements :

Philippe BAUDOIN, Jean-Pierre DAUBRESSE, Alain DÉLOT, Yvonne DERUDDER, Jean DUROUX, Freddy HAEDERLI, Pierre LAFARGUE, Clément PORTAIS.

Remerciements très spéciaux

Irakli de DAVRICHEWI

Louis ARMSTRONG — Volume 15

1948… It wasn’t 1984, of course, but it was still one of those years that, for better or, not worse, but only slightly less than good, would stand out in the life and career of Louis Armstrong.

It was the year his international career made a new start, this time for good, after a brutal interruption in 1935 for health reasons and also some incompatible differences in temperament. From 1948 onwards, Louis would divide himself almost equally between his native country and the vast world that was finally opening its arms to him. Over the next months he travelled through old Europe (the only distant territory he’d so far visited, and then only partly); also through the part of the American continent located in the other hemisphere; and also the Africa from which his unlucky ancestors had been forcibly torn; and also Asia; and also Down Under… He would even go — once they’d given him his Ambassador’s sash — as far as the other side of the Iron Curtain during the Cold War…

To cover the world and admire what he saw (and be admired by those who saw him), Louis Armstrong did have a solid group of six musicians, himself included, plus a lady who could sing and dance. After some hesitation, they called their group the All-Stars. It’s true that this band was actually born the previous year — in mid-August 1947, at Billy Berg’s Club out on the Californian coast — and in fact, an earlier concert at Carnegie Hall on February 8, 1947 (cf. Vol. 12 released by Frémeaux, FA 1362) had lifted the veil in a two-part presentation — two halves, one a regular big band, the other a small group — in which this six-piece brought a reaction from the audience to react: after being saturated with big bands for years, they were in favour of the second format, the small-group. The next few months allowed them to polish the All-Stars option, which seemed to suit everyone except (of course) those members of the big band who, with their fatalistic vision, had seen that the time had come (at the gallop), not for days of wine and roses, but rather those darker, leaner days that were a synonym for unemployment!

When you think about it, one can even evoke a general disaffection for ‘big bands’ in favour of bands the size of the one in the 1946 movie New Orleans: severed from a large machine, Louis had the chance to play with a few old cronies, pals from the quiet days of Prohibition Chicago: Kid Ory, Bud Scott, Barney Bigard and Zutty Singleton — nothing but men of the same ilk — but, on the other hand, not a sign of Bing Crosby on the horizon! Obviously, this “jazz big-band crisis” — large formations had been holding the upper hand for two decades already — did not concern Armstrong alone. They didn’t all die, but they had all been stricken, Ellington, Goodman and Basie included. In such favourable circumstances, the All-Stars held all the aces.

In truth, the beginnings of the All-Stars in 1947 were hesitant, imperfect, ‘try-it-and-see’ affairs. There was always something going wrong: one guitar or saxophone too many; a clarinet, piano or drummer who wasn’t exactly the one for the job, whatever his talents… And then all of a sudden, as if by miracle, in January ‘48 everything clicked. The “weak link”, the agreeable pianist Dick Cary (who really liked playing in that group), had been obliged to relinquish his seat in favour of The Master, a man also severed from his big band, and who had been inseparable from Satch’ back in the old days in Chicago: Earl Hines, the man of the “trumpet & piano” style (cf. Volumes 4 and 5). Just look at how everything was falling into place for foreign audiences: Hines came just when Louis was leaving for the first Nice Festival on the French Riviera. Perfect timing!

Most of the general public, however — those who heard music on records and not onstage — came close to never hearing these initial All-Stars, the ideal group and the matrix for all those in the future, for the simple reason that the band never cut a record that went on sale. The fault lay with a new recording ban, albeit shorter and milder than the strike paralyzing studios from August 1942 to November 1944, and it came right at the wrong time. As a result, when the last RCA sides were cut on October 16, 1947, Hines hadn’t yet joined. And at the following copious session featuring the All-Stars, this time for Decca at the end of April 1950, the precarious health of drummer Sidney Catlett in the previous summer had already obliged the latter to bring in a replacement, Cozy Cole. “Big Sid”, who was one of Armstrong’s two or three favourite drummers and a swing musician par excellence – he also played and recorded with Parker and Gillespie, and influenced Max Roach – succumbed to a heart attack on March 25, 1951.

Louis would make a few records in 1949 after the strike (among them two sides with Billie Holiday in September), but the label preferred Louis to be accompanied by larger studio groups, and they bore no relation to the All-Stars. In other words, if numerous concerts and especially appearances on radio (and even television) hadn’t provided a reasonable substitute, the early sextet would have been a great loss for us. Obviously this wasn’t the case, because there were tons of these broadcasts! As we’ve said, it all started in Nice (February 22-29), and continued in Paris at Salle Pleyel (March 2-3, cf. Vol. 14), before more came along after his return home at the end of March ‘48. There was no question of including all those recordings here — there is little variation in the repertoire, hence numerous repetitions — and so we did not make an artistic choice (the music was constantly of the same high level) but focused on technical quality.

This was the case with the abundant sessions from Philadelphia, where the All-Stars were billed for a long while over the end of that spring and also in summer (CD1 and CD2). As some reviewers pointed out, it’s true that audiences were delighted to finally hear Louis Armstrong again, for the first time for ages in a jazz context… No, you’re not dreaming: that was exactly the formula they used in America at the time. So what was Louis up to during all those ‘big-band years’? Had he shamefully betrayed the cause and studied Gregorian chant? Had he fallen for the charms of baroque music thanks to some sweet and perilous sirens’ song, or succumbed to the noxious temptations of the waltz? Did Viennese operetta cart him off, or French mélodies, or the twelve-tone system perhaps? I don’t think this is quite the right time to… That’s what happens when words don’t have the same meaning everywhere. And it’s precisely what went on in those days of upheaval, re-composition etc. Just think: at the very same moment, and in the same place, a certain Charlie Parker (the other soloist of genius) was coldly asserting that his music, and that of his associates, didn’t have roots buried in what people commonly referred to as “jazz”. And yes, you would need to know also what was commonly called jazz.

Before the Pennsylvania bookings and a May 3 concert at Carnegie Hall — we don’t have all its echoes — in April the All-Stars took a little sidestep into Illinois for at least one programme for NBC that has given us new versions of Muskrat Ramble and Do You Know What It Means To Miss New Orleans… or in other words, a well-known Kid Ory composition that was well past voting-age (it was first waxed for that facetious muskrat by the Hot Five on Feb. 26, 1926, for OkeH – cf. Vol. 3), and something a lot more recent, specially conceived for the film New Orleans (with a first commercial recording on Oct. 17, 1946 for RCA – cf. Vol. 12). And so the All-Stars had already established the concept of alternating tunes that were already old (and therefore known to everyone) with other pieces that were new — but still performed in a similar spirit —, as the concerts in Nice and Paris had also demonstrated. To be absolutely fair, it must be made clear that when it came to the ratio between the two, the good old standards — those that the public constantly cried out for — soon quickly outnumbered the more recent tunes, even if a young “hit” sometimes carried off an unexpected triumph: like C’est si bon or La vie en rose, for example…

Records, of course, especially with the arrival of the LP, plus the notion of albums conceived around a theme, would offer a much wider variety of music, but they would often be made with studio groups rather than the working band. In any case, for the time being the strike was going on and on, and some record companies would manage to take advantage of this very annoying imposed inertia to modernise their technology. They notably did so by purchasing big new machines commonly called “magnetic-tape recorders”, which were advantageous substitutes for direct-to-disc recording. Buyers obviously didn’t include the dinosaurs among the labels, whose purse strings remained hermetically sealed while they waited for 1950-51. The new tape-deck owners were rather small-to-medium size companies like Capitol, for example… What a pity that Armstrong hardly recorded for Capitol at all! But then again, in the spring of 1948 nobody was counting on records anyway!

And so, from one adventure to the next, from Muskrat Ramble to Do You Know What it Means and Where the Blues Were Born (same film!), from Royal Garden Blues, High Society and Basin Street Blues to A Song Was Born and Mop Mop, from Panama or again Struttin’ With Some Barbecue to East of the Sun and Don’t Fence Me In, via things that were rarer, such as Milenberg Joys, King Porter Stomp, Little White Lies, Whispering, Together, The One I Love Belongs To Somebody Else and S’posin’, we would go from Philadelphia (“Ciro’s” in June) and back to Philadelphia (“The Click” in September), with detours of all sizes to the Big Apple, the Windy City and that of the Angels (or the Crescent), carefully steering clear of any straight line that was the mother of all vice… As for those “things that were rarer”, they were often – but not always – the “specialties” of other members of the group, Big Tea (Basin Street, Baby Won’t You Please Come Home, Maybe You’ll Be There) and Big Sid (Mop Mop), Fatha (East of the Sun, The One I Love, or the superb Pale Moon), Barney (Tea for Two, Body and Soul), Arvell (How High the Moon), Velma (I Cried for You, Together, Don’t Fence Me In, Little White Lies, Blue Skies…) The boss committed sparingly to those – if he did so at all (with Pale Moon). But that didn’t stop him from wonderfully playing stooge to Fatha Hines on his mascot theme (par excellence, and that for a good fifteen years), i.e. his composition Rosetta (CD2, track 18). This can be heard like an echo of those moments of great creation when the two partners played as one on their fabulous Weather Bird, twenty years previously to the day…

Autumn and winter ‘48 were spent mainly on the East Coast, in New York according to the sources we have. Meaning audio sources, because there were television shows (for CBS and WPIX) on November 21 and 23, but the video hasn’t come down to us (CD2, tracks 13-15)… Also to be noted was a booking from mid-December at Chicago’s Blue Note, which resulted in radio appearances on channels ABC and WBBM (CD2, tracks 16, 17). Moreover, on October 29 (or 30), the All-Stars had also given a concert in the context of Gene Norman’s Dixieland Jubilee at the Civic Auditorium in Pasadena, Calif. These new versions of King Porter Stomp, Black and Blue, Royal Garden Blues, Basin Street Blues, or That’s my Desire, which in their day appeared on large “Vinylite” discs (33rpm, 16”) destined for army radio (AFRS) in the Just Jazz series (N°s 28, 29, 30, 36, 49, etc.) were much more rare, and the quality of the copies at our disposal is miserable. But rest assured, those versions of basic themes in the repertoire hardly differ from those reproduced here.

That stay in Pasadena only a stone’s throw from the Mecca of the film industry seems to suggest another Armstrong connection with the order of the Seventh Art. And indeed, Satchmo’s filmography, plus a few works that deal with “jazz & film” as a couple, indicate for 1948 a mysterious Courtin’ Trouble, directed by one Ford Beebe for the little studio Monogram which specialized in penniless westerns and often employed the young John Wayne (another Duke!) in or around ‘33-’35. We don’t know who its actors or musicians were, nor which pieces were played. In 1938, already, in Frank Tuttle’s Doctor Rhythm (for Paramount) with Bing Crosby, Louis was to appear in one scene and play The Trumpet Prayer’s Lament: all of it was indeed filmed, and then… cut from the film during the editing! The only things we do have are a few photos taken on the set. And we don’t even have that for Courtin’ Trouble. Was that one really ever released?

There was one film that had already really been released: A Song Is Born at the end of 1948. Mentioned in Vol. 13 of this series, it appeared in the summer of 1947 and gathered a pretty collection of jazzmen – Benny Goodman, Tommy Dorsey, Charlie Barnet, Mel Powell, Louie Bellson, Lionel Hampton, and Satch’ of course – around the pleasant Danny Kaye, all of it under the aegis of Howard Hawks and producer Samuel Goldwin. Why did they wait over a year before presenting this juicy, swinging piece of celluloid to the public? Maybe a question of film rights, perhaps, or distribution problems… Whatever the reason, if you take account of the customary dating of a movie (by referring to its appearance at the box-office, rather than the period when it was filmed), then the film A Song Is Born should indeed belong to 1948. We preferred (as we did for New Orleans) to stay with its real chronology by putting the music where it belongs.

His little detour into Chicago and its Blue Note club lasted until January ‘49, and then Louis, briefly separated from the All-Stars, hopped over to California as the guest of an old friend, the above-mentioned Bing Crosby (who was in that 1938 film where they nearly appeared together!) Incidentally, another movie from that period (Pennies From Heaven, 1936) actually does have the pair of them, but still not together (they are in different scenes, cf. Vol. 7!)

But this was February 1949, and the subject wasn’t films but radio. True, Bing Crosby had most often been linked (along with his comic stooge Bob Hope) to a famous and juicy series of films collectively known as the Road To movies. Roads to all over the place, wherever… and Bing was an adored movie star, despite ears that stuck out and a premature bald patch, and his name also guaranteed him a spot on major radio stations. As a radio host, Bing’s guests on-air were anyone and everyone in fashion, and the songs to which he lent his own vocal chords were just as much in vogue… and Louis Armstrong, as we know, was a favourite with crooners. Early in 1937, in another friendly gesture, Rudy Vallée — he’d already written the preface for Armstrong’s autobiography Swing That Music — gave Louis the controls of the very popular radio show he had been presenting for years on NBC (cf. Vol. 8) And now Crosby, who was always delighted to chat with Louis, invited him to come down to the radio station whenever he could. We don’t have previous shows, so the one recorded on February 21, 1949 (broadcast on March 16) is the earliest one as far as we are concerned here. This one was recorded in ABC’s San Francisco studio, for an episode of the Philco Radio Show in which Bing was host to: singer Peggy Lee; violinist Joe Venuti; one of Bing’s favourite accompanists from the Paul Whiteman days (1928-1930) where they first met, Jack Teagarden, himself an alumnus of “The King of Jazz”; and Louis, naturally.

The sound was recorded onto tape (which also made for easier editing), and the shows were not broadcast “live” but later; these were factors that now favoured more flexibility and comfort, more freedom of tone (and even humour), than one could find in shows produced in the old days, when they went straight out over the air… not to mention the fact that tapes could be stored in a vault, so that we can access them today.

And so, after Peggy Lee’s sole contribution — which we can do without, while hoping that the lady won’t hold it against us — and after an unavoidable “a word from our sponsors”-type ad, we are privy to a lovely little fireside conversation of almost six minutes between Bing, Louis, Tea and Joe Venuti. That’s a long chat, especially when not everyone understands American. Should we have omitted such a laid-back moment of warm, more than friendly complicity, on the pretext that providing subtitles wouldn’t have been easy? We didn’t think so. The four musician-friends above are so spontaneous, and they add so much life to the proceedings, that we are not sure that subtitles could have done the job. And in any case you can always skip to the following track! The latter are devoted to the music.

They begin with Panama, a good ‘ole New Orleans-type tune of which we already have several versions – two of them right here – but Louis hadn’t recorded them for sale early in 1949. The delicate Lazy River, on the other hand, was one he’d waxed for OkeH as early as November 3, 1931 (cf. Vol. 6), and more recent versions can be heard with the All-Stars (here on CD2, track 12). The latter is a feature, perhaps more than usual, for the rich playing of Teagarden. The other “Lazyˮ, the languid Lazy Bones, a delicious Hoagy Carmichael song/manifesto claiming that indolence is one of our rights, could hardly fail to seduce a Bing Crosby and a Louis Armstrong, neither of whom ever worked less than the other. This fishing expedition on a hot summer’s day, decidedly, has an irresistible charm… And by the time they get to their amply deserved afternoon snooze deep in their old Rockin’ Chairs (Carmichael again…) they’re out of everyone’s reach. Unrivalled.

And while all this was going on, with Louis, Bing & Co. resting in the shade under the Golden Gate Bridge, the press was doing its job. On this same February 21, 1949, Time Magazine plastered Louis Armstrong across its front page and gave him a 10-column reportage! Maybe that doesn’t mean so much in this day and age, but over there, and in those days (maybe even today…), the best word to describe it would be “exploit”.

Following that Time cover, the early spring of ‘49 was one the All-Stars spent in California, with several concerts at the Hollywood Empire in L.A., large excerpts of which found their way onto AFRS transcriptions in the Jubilee series (with one of them, under the name Just Jazz, being the one with the most jazz to be gleaned.) Some of those recordings make up the majority of CD3 (tracks 6-19). In April the band went to play at the State Theater in Cincinnati, Ohio, with four concerts on April 21, 22, 26 & 27 of which we have echoes that allow us to form at least some opinion of what they were about, but not a single note on record – except for an Ain’t Misbehavin’ (made on the 27th) that is proud, potent… and very hard to listen to due to the sound quality (track 20).

And that’s the end of Volume 15…

The end? Not quite. Looking back over the above, you notice that something’s missing. It must be that detour via his beloved hometown New Orleans, abandoned for so long but never replaced inside his musician’s heart. It so happens that down there, they also celebrate carnivals with as much picaresque as in Rio, Venice or Nice. They call this Mardi Gras, and the city’s many clubs organize festivities, decorate floats that are a long time in the making… and they crown a Queen. One such club is the Zulu Social Aid and Pleasure Club, founded in the early 20th century by Black workers, and it, too, parades its own float and sovereigns. The titles of a few pieces of this kind, Zulu’s Ball or King of the Zulus, are obvious references to the tradition. And that is what this is all about: for the year 1949, Louis Armstrong was crowned King of the Zulus, a celebrity, even though he hadn’t been a New Orleans resident for ages. The cover of Time Magazine and its accompanying article naturally tied in with this event, and the press coverage was immense… Delighted, and taking to heart what he considered a great honour, Satch’ played his role licking his lips, unrecognizable in make-up from head to foot, drinking champagne on board a float and chucking coconuts to the public as the tradition would have it. His Queen was Bernice Oxley, and on that Shrove Tuesday, March 1, he received the keys of the city from the Mayor, who made Louis an honorary citizen. To cap it all, he met up with Peter Davis again, the gentleman who, thirty-four years earlier, had nudged him into a musical career by making him a member of the brass band at the Colored Waifs’ Home For Boys, first as their tambourine-player, and then on bugle! Nevertheless, it was a Selmer trumpet he was blowing on February 27 when, barely after his arrival, Louis gave a concert at the Booker T. Washington Auditorium that was broadcast on channel WDSU. Shoe Shine Boy and Royal Garden Blues were among the numbers played.

As might be expected, this clownish yet innocent way of making a fool of himself was not to everybody’s taste. Fans of jazz, a serious music if ever there was, and also Black politicians among the authorities, made a point of cutting him down to size, with some even calling him an idiot. Armstrong couldn’t have cared less; he wasn’t the calculating type, and pulled off a remarkable publicity stunt that catapulted him to stardom at last. And then there was the pleasure of it all. Especially that of being recognized with all the bells and whistles that were de rigueur… He’d wanted to be recognized ever since that day in 1922, when he’d left to find glory elsewhere – deep down he’d always wanted it.

Louis Armstrong, King of the Zulus, was finally in the skin of the man who, a long, long time ago, had made it clear he preferred to be the “First man” there (in that forgotten hole probably called Lutecia) rather than Second in Rome.

Adapted by Martin Davies

from the French text of Daniel Nevers

© 2018 Frémeaux & Associés

With thanks to:

Philippe BAUDOIN, Jean-Pierre DAUBRESSE, Alain DELOT, Yvonne DERUDDER, Jean DUROUX, Freddy HAEDERLI, Pierre LAFARGUE and Clément PORTAIS.

My very special thank you to:

Irakli de DAVRICHEWI.

DISQUE / DISC 1

LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND THE ALL-STARS

Louis ARMSTRONG (tp, voc) ; Weldon “Jack” TEAGARDEN (tb, voc) ; Albany “Barney” BIGARD (cl) ; Earl “Fatha” HINES (p) ; Arvell SHAW (b) ; Sidney “Big Sid” CATLETT (dm) ; Velma MIDDLETON (voc).

Formation identique sur tous les titres ci-dessous / Personnel as above on all titles below

- Chicago, Ill. – NBC Broadcast/Radio – 4/04/1948

1. MUSKRAT RAMBLE (Ed Ory) 3’55

2. DO YOU KNOW WHAT IT MEANS TO MISS NEW ORLEANS ? (L.Alter-E.De Lange) 4’00

- Philadelphia, PA. – KYW Broadcast/Radio – “Ciro’s Club” – 2 & 3/06/1948

3. I CRIED FOR YOU (A.Lyman-G.Arnheim-A.Freed) 4’14

4. CONFESSIN’ (Neiburg-Dougherty-Reynolds) 4’31

5. MILENBERG JOYS (F.Morton) 2’41

- Philadelphia, PA. – KYW Broadcast/Radio – “Ciro’s Club” – 4/06/1948

6. STRUTTIN’ WITH SOME BARBECUE (Lil Hardin) 4’56

7. WHISPERING (J.Schonberger) 4’26

8. ST. LOUIS BLUES (W.C.Handy) 3’35

9. BLUE SKIES (I.Berlin) 3’16

- Philadelphia, PA. – KYW Broadcast/Radio – “Ciro’s Club” – 5/06/1948

10. BASIN STREET BLUES (Sp.Williams) 3’26

11. HIGH SOCIETY (P.Steele) 3’46

12. SOMEDAY YOU’LL BE SORRY (L.Armstrong) 3’17

13. THE ONE I LOVE BELONGS TO SOMEBODY ELSE (I.Jones-G.Kahn) 3’25

14. JACK-ARMSTRONG BLUES (L.Armstrong-J.Teagarden) 3’30

15. TOGETHER (R.Henderson-J.Brown-B.G.DeSylva) 3’28

16. I GOTTA RIGHT TO SING THE BLUES (T.Koehler-H.Arlen) 2’58

- Philadelphia, PA. – KYW Broadcast/Radio – “Ciro’s Club” – 12/06/1948

17. THAT’S A PLENTY (L.Pollack-R.Gilbert) 3’16

18. EAST OF THE SUN (WEST OF THE MOON) (Bowman-Anne) 2’48

19. I GOT RHYTHM (G. & I. Gershwin) 1’52

20. I SURRENDER DEAR (Barris-Clifford) 4’20

21. DON’T FENCE ME IN (C.Porter-R.Fletcher) 3’56

22. ST. LOUIS BLUES (W.C.Handy) 1’38

DISQUE / DISC 2

LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND THE ALL-STARS

Louis ARMSTRONG (tp, voc) ; Jack TEAGARDEN (tb, voc) ; Barney BIGARD (cl) ; Earl HINES (p) ; Arvell SHAW (b) ; Sidney CATLETT (dm) ; Velma MIDDLETON (voc).

Formation identique sur titres 1 à 12 / Same personnel for titles 1 to 12

- Philadelphia, PA. – CBS Broadcast/Radio (“America Dances”) – “The Click” – 10/09/1948

1. Louis ARMSTRONG, Russ MORGAN & Fred ROBBINS : Discussion/Talking & DO YOU KNOW WHAT IT MEANS TO MISS NEW ORLEANS ? (L.Alter-E.De Lange) 5’10

2. Louis & Robbins : Discussion/Talking & STRUTTIN’ WITH SOME BARBECUE (Lil Hardin) 5’04

- Philadelphia, PA. – KYW broadcast/Radio – “The Click” – 11 (3-6) & 18 (7-12)/09/1948

3. LITTLE WHITE LIES (W.Donaldson) 3’47

4. BLACK AND BLUE (T.W.Waller-A.Razaf) 3’16

5. SHADRACK / WHEN THE SAINTS GO MARCHIN’ IN (Trad.) 4’48

6. BABY WON’T YOU PLEASE COME HOME (C.Williams-C.Warfield) & Theme 5’24

7. MUSKRAT RAMBLE (Ed Ory) 5’55

8. PANAMA (W.H.Tyers) 4’26

9. MAYBE YOU’LL BE THERE (Gallop-Bloom) 5’08

10. S’POSIN’ (P.Denniker-A.Razaf) 3’56

11. ROYAL GARDEN BLUES (C. & Sp. Williams) 4’40

12. LAZY RIVER (H.Carmichael-S.Arodin) 4’10

“TOAST OF THE TOWN” (Ed SULLIVAN SHOW)

Formation comme pour 1 à 12 / Personnel as for 1 to 12. Michael A. “Peanuts” HUCKO (cl) remplace/replaces BIGARD. Plus Ed SULLIVAN (mc).

CBS TV Show / Spectacle télévisé CBS – New York City, 21/11/1948

13. Introduction & WHERE THE BLUES WERE BORN IN NEW ORLEANS (Cappleton-Dixon) 3’49

14. A SONG WAS BORN (D.Raye-G.DePaul) 3’30

“EDDIE CONDON FLOOR SHOW”

Formation comme pour 13 & 14 / Personnel as for 13 & 14. Dick CARY (p) remplace/replaces HINES. Plus Eddie CONDON (g, mc).

WPIX TV Show / Spectacle télévisé WPIX – New York City, 23/11/1948

15. KING PORTER STOMP (F.Morton) (Jazz Society AA530 / mx. SOF 5221) 4’17

LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND THE ALL-STARS

Formation comme pour 1 à 12 / Personnel as for 1 to 12.

Chicago, Ill. – WBBM Broadcast/Radio – Dec. 1948

16. BLACK AND BLUE (T.W.Waller-A.Razaf) 3’39

“PERSONAL AUTOGRAPH SHOW”

Earl HINES (p) & Louis ARMSTRONG (tp) with bass & drums.

Chicago, Ill. – Broadcast/Radio – Fin/late 1948 ou début/or early 1949

17. ROSETTA (E.Hines-H.Woods) 2’55

DISQUE / DISC 3

“PHILCO RADIO TIME”

Louis ARMSTRONG (tp, voc) ; Jack TEAGARDEN (tb, voc) ; Joe VENUTI (vln, comments) ; Buddy COLE (p) ; Perry BOTKIN (g) ; James MOORE (b) ; Nick FATOOL (dm) ; Bing CROSBY (voc & comments).

San Francisco, CA. – ABC Broadcast/Radio (NBC Studios) – 21/02/1949

1. Entretien entre / Talking between Bing Crosby, Louis Armstrong, Jack Teagarden, Joe Venuti… 5’36

2. PANAMA (W.H.Tyers) 2’30

3. LAZY RIVER (H.Carmichael-S.Arodin) 2’04

4. LAZY BONES (H.Carmichael-J.Mercer) 2’57

5. ROCKIN’ CHAIR (H.Carmichael) 2’55

LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND THE ALL-STARS

Louis ARMSTRONG (tp, voc) ; Jack TEAGARDEN (tb, voc) ; Barney BIGARD (cl) ; Earl HINES (p) ; Arvell SHAW (b) ; Sidney CATLETT (dm) ; Velma MIDLETON (voc).

Formation identique sur titres 6 à 20 / Same personnel for titles 6 to 20

- Los Angeles CA. – “The Hollywood Empire” – Broadcast/Radio (AFRS Transcriptions) – Fin mars/Late March 1949

6. Intro & Theme : WHEN IT’S SLEEPY TIME DOWN SOUTH (L. & O.René-C.Muse) (AFRS “Jubilee” Program 339) 1’48

7. PANAMA (W.H.Tyers) (AFRS “Jubilee” Program 339) 4’23

8. BACK O’ TOWN BLUES (L.Armstrong-L.Russell)(AFRS “Jubilee” Program 339) 5’11

9. PALE MOON (J.G.M.Glick-F.K.Logan) (AFRS “Jubilee” Program 339) 3’51

10. DON’T FENCE ME IN (C.Porter-R.Fletcher) (AFRS “Jubilee” Program 339) 4’49

11. BODY AND SOUL (Green-Heyman-Sour-Eyton) (AFRS “Jubilee” Program 339) 4’51

12. A SONG WAS BORN (D.Raye-G.DePaul) (AFRS “Jubilee” Program 347) 4’02

13. WHISPERING (J.Schonberger) (AFRS “Jubilee” Program 347) 3’42

14. MAHOGANNY HALL STOMP (Sp.Williams) (AFRS “Jubilee” Program 344) 4’14

15. A HUNDRED YEARS FROM TODAY (J. & V.Young-N.Washington) (AFRS “Jubilee” Program 344) 4’42

16. BLUE SKIES (I.Berlin) (AFRS “Jubilee” Program 344) 3’15

17. ROCKIN’ CHAIR (H.Carmichael) (AFRS “Jubilee” Program 337) 3’17

18. THE SHEIK OF ARABY (Snyder-Wheeler-Smith) (AFRS “Jubilee” Program 337) 3’17

19. CONFESSIN’ (Neiburg-Dougherty-Reynolds) (AFRS “Jubilee” Program 337) 4’56

- Cincinnati, Ohio – Concert “State Theater” – 27/04/1949

20. AIN’T MISBEHAVIN’ (T.W.Waller-A.Razaf) (Bande amateur/Private tape) 4’18

« J’ai rencontré Louis pour la première fois à Chicago, quand il venait de quitter l’orchestre de King Oliver. (…) Personne n’a été capable de l’imiter avec succès. Certains essayent de jouer de la trompette comme lui, d’autres de chanter comme lui, mais rien ne se produit. Quand Louis joue, il plane. Quand il chante, il pétille… »

Bing CROSBY

“I first met Louis in Chicago, just after he left King Oliver’s band (…) Nobody could copy him. Some were trying to play the trumpet like he does, but nothing happened… It’s so simple: when he sings a sad song you cry, and when he sings a happy song, you laugh.”

Bing CROSBY

CD 1

LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND THE ALL-STARS (Radio - Chicago, 4/04/1948 : 1 & 2 // Philadelphie, juin/June 1948 : 3 - 22)

1. MUSKRAT RAMBLE 3’55

2. DO YOU KNOW WHAT IT MEANS TO MISS NEW ORLEANS ? 4’00

3. I CRIED FOR YOU 4’14

4. CONFESSIN’ 4’31

5. MILENBERG JOYS 2’41

6. STRUTTIN’ WITH SOME BARBECUE 4’56

7. WHISPERING 4’26

8. ST. LOUIS BLUES 3’35

9. BLUE SKIES 3’16

10. BASIN STREET BLUES 3’26

11. HIGH SOCIETY 3’46

12. SOMEDAY YOU’LL BE SORRY 3’17

13. THE ONE I LOVE BELONGS TO SOMEBODY ELSE 3’25

14. JACK-ARMSTRONG BLUES 3’30

15. TOGETHER 3’28

16. I GOTTA RIGHT TO SING THE BLUES 2’58

17. THAT’S A PLENTY 3’16

18. EAST OF THE SUN (WEST OF THE MOON) 2’48

19. I GOT RHYTHM 1’52

20. I SURRENDER DEAR 3’56

21. DON’T FENCE ME IN 3’56

22. ST. LOUIS BLUES 1’38

CD 2

LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND THE ALL-STARS (Radio - Philadelphie, 10, 11 & 18/09/1948 : 1 à/to 12)

1. Discussion / Talking : L. Armstrong, Russ Morgan, Fred Robins + DO YOU KNOW WHAT IT MEANS TO MISS NEW ORLEANS ? 5’10

2. Discussion & STRUTTIN’ WITH SOME BARBECUE 5’04

3. LITTLE WHITE LIES 3’47

4. BLACK AND BLUE 3’16

5. SHADRACK / WHEN THE SAINTS GO MARCHIN’ IN 4’48

6. BABY WON’T YOU PLEASE COME HOME ? + Theme 5’24

7. MUSKRAT RAMBLE 5’55

8. PANAMA 4’26

9. MAYBE YOU’LL BE THERE 5’08

10. S’POSIN’ 3’56

11. ROYAL GADEN BLUES 4’40

12. LAZY RIVER 4’10

“ED SULLIVAN SHOW” (WPTX TV - New York City, 21/11/1948)

13. Intro + WHERE THE BLUES WERE BORN IN N.O. 3’49

14. A SONG WAS BORN 3’30

“EDDIE CONDON SHOW”(WBBM TV - New York City, 23/11/1948)

15. KING PORTER STOMP 4’17

LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND THE ALL-STARS (Radio)

16. BLACK AND BLUE 3’39

“PERSONAL AUTOGRAPH SHOW”

(Radio - Chicago, Dec 1948)

17. ROSETTA 2’55

CD 3

PHILCO RADIO TIME (Bing Crosby Show)

(San Francisco, 21/02/1949)

1. Entretien / Talking : B. Crosby, L. Armstrong, J.Teagarden, J.Venuti 5’36

2. PANAMA 2’30

3. LAZY RIVER 2’04

4. LAZY BONES 2’57

5. ROCKIN’ CHAIR 2’55

LOUIS ARMSTRON AND THE ALL-STARS (Radio - AFRS “Jubilee” Transcriptions - Los Angeles, mars/March 1949)

6. Intro & Theme : WHEN IT’S SLEEPY TIME DOWN SOUTH 1’48

7. PANAMA 4’23

8. BACK O’ TOWN BLUES 5’11

9. PALE MOON 3’51

10. DON’T FENCE ME IN 4’49

11. BODY AND SOUL 4’51

12. A SONG WAS BORN 4’02

13. WHISPERING 3’42

14. MAHOGANY HALL STOMP 4’14

15. A HUNDRED YEARS FROM TODAY 4’42

16. BLUE SKIES 3’15

17. ROCKIN’ CHAIR 3’17

18. THE SHEIK OF ARABY 3’17

19. CONFESSIN’ 4’56

LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND THE ALL-STARS (Concert - Cincinnati, 27/04/1949)

20. AIN’T MISBEHAVIN’ 4’18

Les intégrales Frémeaux & Associés réunissent généralement la totalité des enregistrements phonographiques originaux disponibles ainsi que la majorité des documents radiophoniques existants afin de présenter la production d’un artiste de façon exhaustive. L’Intégrale Louis Armstrong déroge à cette règle en proposant la sélection la plus complète jamais éditée de l’œuvre du géant de la musique américaine du XXe siècle, mais en ne prétendant pas réunir l’intégralité de l’œuvre enregistrée.