- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

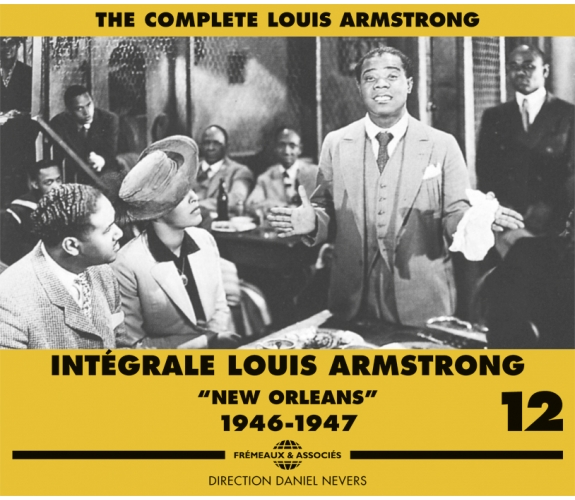

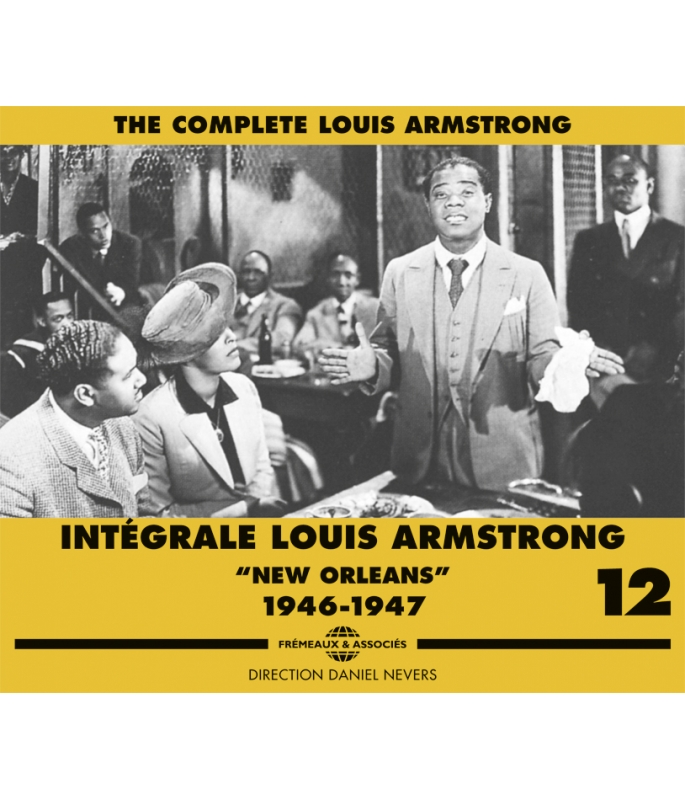

NEW ORLEANS 1946-1947

LOUIS ARMSTRONG

Ref.: FA1362

EAN : 3561302136226

Artistic Direction : DANIEL NEVERS

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Total duration of the pack : 3 hours 23 minutes

Nbre. CD : 3

NEW ORLEANS 1946-1947

NEW ORLEANS 1946-1947

“What the Hollywood people do is never authentic. They always choose the actor whose looks and acting are on the other side of the world from the character whose life-story they’re telling.” Louis ARMSTRONG

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Long Long JourneyLouis Armstrong - Esquire All-Americans Award WinnersL. Feather00:04:341946

-

2SnafuLouis Armstrong - Esquire All-Americans Award WinnersL. Feather00:04:151946

-

3You Won't Be SatisfiedLouis Armstrong - Ella FitzgeraldF. James00:02:551946

-

4The Frim Fram SauceLouis Armstrong - Ella FitzgeraldJ. Ricardel00:03:141946

-

5Linger in My Arms a Little LongerLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraH. Magdison00:03:011946

-

6Whatta Gonna Do ?Louis Armstrong and his OrchestraSkylarck00:02:581946

-

7No Variety BluesLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraLouis Armstrong00:02:561946

-

8Joseph and His BruddersLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraLouis Armstrong00:03:031946

-

9Back O' Town BluesLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraLouis Armstrong00:03:191946

-

10I Want a Little GirlLouis Armstrong and his Hot Seven/Hot SixMoll00:03:021946

-

11SugarLouis Armstrong and his Hot Seven/Hot SixM. Pinkard00:03:251946

-

12Blues for YesterdayLouis Armstrong and his Hot Seven/Hot SixL. Carr00:02:371946

-

13Blues for The SouthLouis Armstrong and his Hot Seven/Hot SixW. Johnstone00:03:031946

-

14Flee as A BirdLouis Armstrong - New Orleans (Film) Pré-enregistrementTraditionnel00:03:121946

-

15West End BluesLouis Armstrong - New Orleans (Film) Pré-enregistrementJ. Oliver00:02:531946

-

16Tiger RagLouis Armstrong - New Orleans (Film) Pré-enregistrementD. J. La Rocca00:02:251946

-

17Where The Blues Where Born in New OrleansLouis Armstrong - New Orleans (Film) Pré-enregistrementCapleton00:04:391946

-

18Buddy Bolden BluesLouis Armstrong - New Orleans (Film) Pré-enregistrementF. Morton00:01:511946

-

19Basin' Street BluesLouis Armstrong - New Orleans (Film) Pré-enregistrementSp. Williams00:04:451946

-

20Raymond Street BluesLouis Armstrong - New Orleans (Film) Pré-enregistrementLouis Armstrong00:01:251946

-

21Maryland My MarylandLouis Armstrong - New Orleans (Film) Pré-enregistrementTraditionnel00:03:011946

-

22Bramhs LullabyLouis Armstrong - New Orleans (Film) Pré-enregistrementJohannes Brahms00:00:481946

-

23Farewell to StoryvilleLouis Armstrong - New Orleans (Film) Pré-enregistrementCootie Williams00:03:151946

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Milenberg JoysLouis Armstrong - New Orleans (Film) Pré-enregistrementP. Mares00:01:561946

-

2Dippermouth Blues (Lent-Slow)Louis Armstrong - New Orleans (Film) Pré-enregistrementJ. Oliver00:01:241946

-

3Dippermouth Blues (Rapide-Fast)Louis Armstrong - New Orleans (Film) Pré-enregistrementJ. Oliver00:01:361946

-

4Shimme Sha WableLouis Armstrong - New Orleans (Film) Pré-enregistrementS. Williams00:02:071946

-

5Ballin' The JackLouis Armstrong - New Orleans (Film) Pré-enregistrementC. Smith00:02:121946

-

6King Porter StompLouis Armstrong - New Orleans (Film) Pré-enregistrementF. Morton00:02:351946

-

7Mahogany Hall Stomp (Lent-Slow)Louis Armstrong - New Orleans (Film) Pré-enregistrementS. Williams00:03:311946

-

8Mahogany Hall Stomp (Rapide-Fast)Louis Armstrong - New Orleans (Film) Pré-enregistrementS. Williams00:03:361946

-

9The Blue Are BrewingLouis Armstrong - New Orleans (Film) Pré-enregistrementL. Alter00:03:441946

-

10EndieLouis Armstrong - New Orleans (Film) Pré-enregistrementL. Alter00:02:221946

-

11Do You Know What It Means to Miss New OrleansLouis Armstrong - New Orleans (Film) Pré-enregistrementL. Alter00:01:471946

-

12EndieLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraL. Alter00:02:531946

-

13The Blues Are BrewingLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraL. Alter00:02:591946

-

14Do You Know What It Means to Miss New Orleans 2Louis Armstrong and his Dixieland SevenL. Alter00:03:021946

-

15Where The Blues Were Born in New OrleansLouis Armstrong and his Dixieland SevenCapleton00:03:101946

-

16Mahogany Hall StompLouis Armstrong and his Dixieland SevenS. Williams00:02:581946

-

17Flee As a Bird 2Louis Armstrong with Edmund Hall's SextetTraditionnel00:03:171947

-

18Dippermouth BluesLouis Armstrong with Edmund Hall's SextetJ. Oliver00:02:211947

-

19Mahogany Hall Stomp 2Louis Armstrong with Edmund Hall's SextetS. Williams00:02:541947

-

20Muskrat RambleLouis Armstrong with Edmund Hall's SextetEd Ory00:02:201947

-

21Black and BlueLouis Armstrong with Edmund Hall's SextetFats Waller00:04:181947

-

22Lazy RiverLouis Armstrong with Edmund Hall's SextetArodin00:03:311947

-

23You, Rascal YouLouis Armstrong with Edmund Hall's SextetS. Theard00:03:371947

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Save It Pretty MamaLouis Armstrong with Edmund Hall's SextetD. Redman00:03:031947

-

2Ain't Misbehavin'Louis Armstrong with Edmund Hall's SextetFats Waller00:02:561947

-

3St Louis BluesLouis Armstrong with Edmund Hall's SextetW.C. Handy00:02:551947

-

4Rockin' ChairLouis Armstrong with Edmund Hall's SextetH. Carmichael00:05:001947

-

5Tiger RagLouis Armstrong with Edmund Hall's SextetD.J. La Rocca00:04:451947

-

6Confessin'Louis Armstrong with Edmund Hall's SextetNeiburg00:04:091947

-

7Struttin' With Some BarbecueLouis Armstrong with Edmund Hall's SextetL. Hardin00:01:531947

-

8Theme and Stompin' at The SavoyLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraB. Goodman00:03:401947

-

9I Can't Give You Anything But LoveLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraJ. McHugh00:02:551947

-

10Back O' Town BluesLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraLouis Armstrong00:04:461947

-

11You Won't Be Satisfied 2Louis Armstrong and his OrchestraF. James00:03:391947

-

12Do You Know What It Means to Miss New Orleans 3Louis Armstrong and his OrchestraLouis Alter00:04:221947

-

13Roll' EmLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraM.L. Williams00:01:401947

-

14I Wonder, I Wonder I, I WonderLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraD. Huntchins00:02:341947

-

15I BelieveLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraS. Kahn00:03:011947

-

16Why Doubt My LoveLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraLouis Armstrong00:03:231947

-

17It Takes TimeLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraA. Korb00:02:391947

-

18You Don't Learn That in SchoolLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraR. Alfred.00:02:441947

-

19Reminiscin' With LouisLouis Armstrong - Saturday Night Swing ShowArt Ford00:01:221947

-

20Ain't Mibehavin 2Louis Armstrong - Saturday Night Swing ShowFats Waller00:02:551947

-

21Do You Know What It Means to Miss New Orleans 4Louis Armstrong - Saturday Night Swing ShowLouis Alter00:04:141947

Intégrale Louis Armstrong Volume 12 FA1362

THE COMPLETE louis armstrong

INTÉGRALE LOUIS ARMSTRONG volume 12

“NEW ORLEANS” 1946-1947

DIRECTION DANIEL NEVERS

Louis ARMSTRONG – volume 12

« C’était mon premier film. Et aussi mon dernier. De toute façon, le tournage fini, j’ai été heureuse de pouvoir me glisser hors de ce truc et de filer. Je l’ai vu plus tard – beaucoup plus tard. Ils avaient enregistré des tas de musiques et tourné des scènes à La Nouvelle Orléans, mais il n’en reste rien dans le film. Et si peu de moi… Je portais une robe blanche pour l’un des morceaux que je chantais dans le film. Tout ça a été coupé. Je n’ai pas fait d’autre film. Et je ne suis pas pressée?»… Ainsi parlait Billie Holiday, dans son autobiographie Lady Sings the Blues, du tournage, en 1946, de cette lamentable pellicule intitulée New Orleans. De fait, disparue en 1959, Billie ne fit plus aucun film. On peut certes l’apercevoir dans quelques courts-métrages (le premier, en compagnie de l’orchestre de Duke Ellington, remonte à 1933) et dans une bouleversante émission de télévision fin 1957, au côté de Basie et sa bande, Hawk, Prez, Ben Webster, Mulligan, Monk… Mais plus question de “grand film”… De son côté, Louis Armstrong, également “vedette” de ce chef-d’œuvre digne d’Ed Wood et Émile Couzinet réunis, il se contenta, déçu, résigné, de constater sans en rajouter : «?ce n’est jamais authentique ce que font les gens d’Hollywood?». Et lui, il n’en était pas à ses premiers pas dans les studios…

Il est vrai que, dans la plupart de ses films précédents, Louis Armstrong jouait le rôle d’un trompettiste/chanteur ressemblant beaucoup à un dénommé Louis Armstrong ! Parfois, une petite variante en fit un valeureux technicien de surface (en français archaïque, un balayeur) ou un garçon d’écurie fort attaché à ce dada du nom de Jeepers Creepers, voire un adorable et souriant diablotin malheureusement presque entièrement – déjà ! – sacrifié au montage (Cabin in the Sky). Mais toujours – c’est dans le contrat – à l’un ou l’autre moment, la trompette ne manque pas de faire sa tonitruante réapparition… Evidemment, on imagine mal Satchmo en armateur grec, en big boss de Wall Street, en chef indien, ou en sanguinaire gangster genre Scarface. Du reste, dans New Orleans aussi, il est censé interpréter un musicien, patron d’une petite formation employée dans un speakeasy de Storyville… On l’y voit et entend jouer, chanter, parler, présenter ses partenaires : c’est là l’un des très rares moments de grâce du film.

Le scénario, plutôt ambitieux pourtant, était basé sur un projet biographique qu’Orson Welles en personne, par qui le scandale Citizen Kane était arrivé, souhaitait réaliser vers 1943-44, Horn of Plenty : un film donnant à entendre le jazz le plus authentique, de sa naissance dans le Sud (surtout dans la Cité du Croissant) jusqu’au tournant des années 1940. Les séquences purement documentaires devaient alterner avec celles de fiction et les compléter. On peut de nos jours contester la réalité d’une telle naissance rêvée en un lieu unique, magique, alors que le déroulement des évènements fut sans doute bien plus complexe, mais en ce temps-là, on avait besoin de certitudes.

Repris par United Artists, le sujet fut retravaillé en dépit du bon sens et la catastrophe devint inévitable.Voici quelques années, Alain Tercinet résumait ainsi le massacre : «?Victimes de pressions de toutes sortes dans lesquelles le McCarthysme naissant n’y était pas pour rien, ils (les dirigeants de la boîte) laissèrent le scénario d’Herbert Biberman – l’un des futurs “Dix d’Hollywood” – être charcuté, édulcoré, mélodramatisé. Des interprètes de seconde zone – Arturo de Cordova, Dorothy Patrick – un metteur en scène inconsistant, l’irruption incongrue de l’orchestre Woody Herman, tout contribua à ce que, une fois achevé, New Orleans se situe aux antipodes du projet d’origine?»… L’histoire devait être centrée sur Louis, Billie, les parades de rues, la fermeture de Storyville en 1917 pour cause de guerre et de puritanisme… Au lieu de cela, Armstrong se trouve relégué et Billie, comme il se doit, devient la boniche d’une chanteuse d’opéra pas très fraîche (Dorothy P.), dont on peut se demander ce qu’elle vient foutre là et, surtout, pourquoi on lui refile tout bonnement la vedette. Même remarque à l’endroit de Woody Herman. Son orchestre de 1946 n’est pas encore celui qui connaîtra la célébrité et révélera de fameux solistes un peu plus tard, mais quoiqu’il en soit, lui non plus n’a rien à faire dans cette pellicule. “Inconsistant”, est sans doute un mot trop faible pour qualifier le réalisateur, Arthur Lubin. “Nullissime”, peut-être ? Rien dans sa filmographie (abondante) ne vient racheter ce péché mortel, surtout pas sa version, somptueusement grotesque, du Fantôme de l’Opéra. N’importe quel tâcheron hollywoodien (le lieu les sécrétait?!), modèle Sam Wood ou Henry Koster, aurait fait moins mal. Pas de danger de le voir figurer sur la liste des “Dix d’Hollywood”, Maître A. Lubin ! Rappelons qu’on désigna sous ce terme les victimes de la chasse aux sorcières, gens de cinéma interdits de studios, réduits au chômage, par le comité des activités anti-américaines que dirigeait le sénateur Joseph McCarthy. Ils s’exilèrent pour la plupart en Europe ; en faisaient partie, entre autres, Joseph Losey, Jules Dassin, John Berry, Cy Enfield, Dalton Trumbo, ainsi que Biberman cité ci-dessus comme scénariste…

Beaucoup de musique a donc été enregistrée – trop sans doute, surtout lorsque l’on sait ce qui fut finalement utilisé. Par chance, ces pré-enregistrements (non couverts par le dialogue et le bruitage), gravés sur une copieuse série de laques 78 tours trente centimètres, ont été miraculeusement conservés en plutôt bon état. Ceux qui connaissent le film retrouveront donc ici dans leur entièreté les quelques extraits que l’on estima opportun d’y inclure, non sans les avoir presque toujours tronqués (Do You Know What It Means…, Where the Blues Were Born in New Orleans, Farewell to Storyville, West End Blues, Tiger Rag, Basin Street Blues,Milenberg Joys, The Blues Are Brewin’…). Et ils auront le plaisir d’ouir nombre d’autres interprétations bêtement passées à la trappe (Buddy Bolden Blues, Raymond Street Blues interprété en quartette, Shimme-Sha-Wabble, Ballin’ the Jack, Maryland, My Maryland, King Porter Stomp, Flee as a Bird, When the Saints, et même quelques mesures de la Berceuse de Brahms…). Louis n’avait jamais encore enregistré certaines de ces pièces. On signalera également que, pour trois d’entre elles, il existe deux versions, une rapide et une lente (Buddy Bolden Blues, Dippermouth Blues, Mahogany Hall Stomp) et que l’on prit aussi la précaution de faire enregistrer au trompettiste quelques notes hautes, au cas où… Mais il semble qu’on renonça à en user.

Le grand orchestre régulier d’Armstrong ne fut que rarement mis à contribution : on peut cependant l’entendre sur Endie (le prénom de Billie dans le film) et The Blues Are Brewin’, qu’interprète Lady Day – du moins ici, car le montage final la fait tout bonnement disparaître. Ces deux morceaux ont bien sûr été soigneusement charcutés, comme à peu près tout les autres d’ailleurs…

Pour les autres, justement, les pourvoyeurs des salles obscures eurent recours à une de ces petites formations censées avoir fait naître le jazz dans les bouges de la Cité du Croissant au début du siècle. En somme, on en revint à ces groupes de studio, Hot Five et Hot Seven, exclusivement réunis pour le disque par Louis entre fin 1925 et fin 1928 (voir volumes 3 à 5 – FA 1353, 1354, 1355). Il se trouve que l’un des membres de ces Hot Five première manière, le tromboniste Edward “Kid” Ory, jouait depuis pas mal de temps sur la Côte Ouest à ce moment-là. Il y avait même fait ses premiers pas dans la cire dès 1922. Et Armstrong, de son côté, avait joué cornet dans son groupe à La Nouvelle Orléans en 1918-19. En conséquence, Ory fut tout naturellement de la partie. Il amena son banjoïste/guitariste Bud Scott, encore un enfant du pays, que Louis avait côtoyé en 1923, aux jours du Creole Jazz Band de King Oliver. C’est lui qui, dans la version OkeH de Dippermouth Blues, lance le légendaire «?Oh, play that thing !?» (voir volume 1 – FA 1351). Et ici, vingt-trois ans après, il remet ça. Cela a dû le rajeunir – mais pas pour longtemps : il disparaîtra en 1949… Barney Bigard, clarinettiste, est un pays lui aussi et lui aussi a joué chez King Oliver, mais en 1926-27, après le départ d’Armstrong. Ensuite, il est resté près de quinze ans chez Duke Ellington. Louis et Barney ont toutefois participé à une séance quasi clandestine en 1927 et, plus récemment, se sont retrouvés côte à côte sur la scène du Metroplitan Opera de New York lors du grand concert Esquire du 18 janvier 44 (voir volume 11 – FA 1361). Quant à Zutty Singleton, tout aussi Louisianais que les précédents, il fut, avec Earl Hines, l’un des compagnons de route de prédilection de Satchmo, surtout dans la seconde moitié des années 1920. C’est lui qui fournit une assise rythmique, à la fois solide et subtile, dans les gravures des Hot Five version 1928. Il fut également de la séance new yorkaise du 27 mai 1940 en petit comité, avec Bechet (voir volume 9). Retrouvailles hélas des plus brèves…

Les deux autres, le pianiste Charlie Beal et le bassiste George “Red” Callender, ne sont pas du Sud. Beal, néanmoins, travailla et enregistra avec Louis en 1933 à Chicago. Callender, le benjamin, pouvait se produire à son avantage dans tous les contextes jazziques et, à ce titre, fut un musicien de studio fort demandé, apparaissant aussi dans nombre de films californiens. Un excellent petit groupe pour un navet qui ne le méritait peut-être pas. Mais dont, avec toutes les réserves possibles, on conseillera quand même la vision : c’est encore là, malgré tout, que l’on voit et que l’on entend le plus Louis Armstrong et Billie Holiday dans le cadre du cinématographe…

A propos de Billie, souvent associée à des musiciens plus jeunes que Satchmo comme Lester Young et l’équipe de Count Basie, on s’est parfois demandé si elle était vraiment à l’aise au côté du chef de file d’une école plus ancienne. En réalité, elle-même précise que, parmi les “anciens” les plus admirés dont elle possédait les disques, deux surtout avaient sa préférence inconditionnelle, Bessie Smith et Louis Armstrong (davantage, sans doute, le chanteur que le trompettiste – bien qu’ils soient indissociables !)… Autre chose : dans sa présentation des membres de l’orchestre au début du film, sur Where the Blues Were Born…, (comme dans le vieux Gut Bucket Blues de novembre 1925), Louis affirme que son instrument est un “old cornet”.De fait, à l’image, c’est bien un cornet qu’il tient entre ses mains puis porte à ses lèvres. Mais c’est quand même une trompette que l’on entend sur la bande-son ! C’est justement avec Gut Bucket Blues qu’Armstrong semble avoir clos sa période cornet pour inaugurer l’ère trompette (voir volume 3) ! Lui-même ne se souvenait plus très bien qui avait, dès 1932-33, indiqué à Hugues Panassié que le passage se situait plutôt fin 26 ou début 27, pour revenir des années plus tard sur cette affirmation. Une chose en tous cas est sûre : une fois la trompette adoptée, Louis n’est plus jamais revenu au “old cornet” de ses débuts. Il en a gardé un en souvenir, puis a donné les autres à de jeunes apprentis musiciens…

Le 6 septembre 1946, alors même que démarrait cette imposante série de pré-enregistrements, une séance de disques se tint dans les studios RCA de Los Angelès, à la demande de la firme française “Swing” dirigée par Charles Delaunay, venu aux USA afin d’étoffer le catalogue de la marque et d’obtenir des informations concernant sa discographie du jazz… Il ne s’agissait pas d’enregistrer les morceaux spécialement composés pour le film, mais de graver quatre titres que Louis n’avait encore jamais confiés à la cire. Furent retenus deux succès de la fin des années 1920, Sugar et I Want a Little Girl, ainsi que deux blues, Blues for Yesterday et Blues in the South. Là encore en petit comité, Louis récupéra Bigard, Singleton, Beal et Callender, mais fit appel au tromboniste Vic Dickenson et au guitariste Allen Reuss ; pour les blues, Leonard Feather remplaça Beal… Ces faces furent d’abord éditées en France dans le courant de 1947 sous étiquette “Swing”, avant d’être publiées sur Victor aux USA. L’un des deux disques annonce «?Louis Armstrong and His Hot Seven?» et le second «?Louis Armstrong and His Hot Six?» : ils sont bien sept, mais dans un cas on met le chef à part, dans l’autre on compte tout le monde, patron inclus ! Des disques d’Armstrong en petite formation : voilà qui n’était pas arrivé depuis longtemps…

On récidiva le 17 octobre, cette fois pour l’enregistrement des airs (nouveaux) du film et pour le compte de RCA, ce qui n’empêcha point ces disques-là de sortir eux aussi en Europe – mais sur His Master’s Voice et Gramophone. En fait, on coupa la poire en deux : pour Endie et The Blues Are Brewin’, c’est le big band en voie d’extinction qui fut de service ; pour Do You Know What it Means… et Where the Blues Were Born…, on récupèra le petit groupe du film, de même que pour Mahogany Hall Stomp, qui n’est pas à proprement parler une nouveauté, mais qui figure aussi dans cette délicieuse fantaisie hollywoodienne. Tous les protagonistes sont présents, à l’exception de Zutty Singleton avec qui Louis s’est brouillé. Ils se réconcilieront mais ne travailleront plus guère ensemble. Pour le remplacer, on fit appel à Minor “Ram” Hall, vétéran de la batterie néo orléanaise, ancien du King Oliver’s Jazz Band et employé durant les années 1940 de Kid Ory…

New Orleans et ses suites couvrent en bonne part le second semestre de 1946. Le premier paraît légèrement plus calme. La guerre est finie (disent-ils), mais les nombreuses séries d’enregistrements effectués par l’AFRS, qui nous ont principalement servi de pâture pour la période précédente (1943-1945 – voir volumes 10 et 11), n’en continuent pas moins. Toutefois, Louis Armstrong ne semble pas y avoir participé en ce début d’année. En revanche, dès le 10 janvier, il est chez RCA à New York, en compagnie de quelques uns des vainqueurs du referendum des lecteurs de la revue Esquire : après la grève et la guerre, il est temps de retrouver les bonnes vieilles habitudes en tournant quelques faces-souvenir entre amis. Deux seulement ce jour-là, mais avec du beau monde. Louis évidemment, et aussi Ellington (qui annonce le premier morceau, Long, Long Journey, au texte soigneusement creux) et son double Billy Strayhorn, ainsi que trois autres ellingtoniens, le clarinettiste Jimmy Hamilton, Johnny Hodges à l’alto et Sonny Greer à la batterie. Plus Charlie Shavers à la trompette, “Don” Byas au ténor, Remo Palmieri à la guitare et “Chubby” Jackson à la basse. Sur Snafu, le second titre, Louis se contente de prendre un beau solo tandis que Neal Hefti, trompettiste et arrangeur, remplace Shavers. Deux autres arias seront gravées le lendemain avec à peu près les mêmes – moins Armstrong.

Celui-ci est en revanche bien présent une semaine plus tard, le 18 janvier, et là non plus il n’est pas venu seul, puisqu’il doit donner le réplique à Ella Fitzgerald sur deux chansons, You Won’t Be Satisfied et The Frim Fram Sauce, la formation de studio étant placée sous la baguette du bassiste Bob Haggart. Ainsi donc Satchmo a rencontré (sur disque) Ella avant de croiser Billie. Il est vrai qu’ils sont proches parents dans l’inspiration et auront d’ailleurs d’autres occasions de se retrouver – ce qui ne sera qu’assez rarement le cas avec Lady Day… Louis et Ella enregistraient alors en exclusivité pour Decca. Mais pour le trompettiste, c’est là son dernier disque, sous le régime de l’exclusivité s’entend : il gravera encore bien d’autres faces pour cette firme avec laquelle il avait signé en 1935, mais dorénavant, il se réservera la possibilité de traiter au coup par coup avec tel ou tel éditeur concurrent – comme de bien entendu, c’est Joe Glaser qui s’occupera de ces menus détails. En 1946-47, c’est, on l’a vu, RCA-Victor qui emporte le morceau…

La première séance officielle pour la dite marque, le 27 avril, réintroduit le grand orchestre ainsi que Velma Middleton, la dodue chanteuse parfois spécialiste du grand écart, que certains n’hésitèrent point à qualifier d’«?ennuyeuse demoiselle (qui) pousse un vocal d’une justesse douteuse pendant la moitié du disque (No Variety Blues)?». Mais apparemment, Armstrong tenait à elle… Armstrong chante aussi, bien sûr, notamment sur Whatta Ya Gonna Do et surtout sur la superbe version destinée à la vente au public de Back O’ Town Blues, dont on connaît deux moutures plus anciennes, pour l’AFRS (1943), puis lors du concert Esquire au “Met” (1944) (voir volumes 10 et 11). Deux autres titres qui laissèrent peu de souvenirs, Joseph ‘n’ his Brudders et Linger in My Arms a Little Longer, complétèrent la session. Ensuite, après la saison d’été, principalement au «?Regal?» et au «?Savoy?» de Chicago, tout le monde embarqua pour Hollywood.

Séance pour “Swing”, mise en boîte des images et des pré-enregistrements (deux bons mois), nouvelle séance chez RCA… Louis et ses équipes (la grande et la petite) ne chômèrent guère de septembre à novembre 46. D’autant que les soirées californiennes furent souvent occupées par les concerts et les dancings. Retourné dans l’Est en fin d’année avec le big band, il joua à l’Apollo et se prépara pour un très grand concert en quatre parties thématiques, programmé à partir de 17 heures 30 le samedi 8 février 1947 à Carnegie Hall, scène illustre, mythique, qu’il n’avait que fort peu fréquentée jusqu’alors.

Les quatre thèmes sont censés se référer aux villes dans lesquelles Armstrong s’illustra à l’un ou l’autre moment de sa carrière : New Orleans, Chicago, New York et Hollywood. En réalité, les organisateurs se sont quelque peu emmêlés ! Si, pour représenter La Nouvelle Orléans on peut facilement admettre les marches interprétées lors des enterrements (Flee As a Bird, Didn’t He Ramble ?), Mahogany Hall Stomp, Basin Street Blues (hauts lieux de l’endroit), voire Dippermouth Blues et Muskrat Ramble (qui auraient tout aussi bien pu illustrer les jours de Chicago), on reste plus réservé à l’endroit des trois autres cités. Pour Chicago, justement, West End Blues et Save It, Pretty Mama sont certes bien à leur place et correspondent à l’an 28 ; en revanche, Black and Blue, Lazy River, You Rascal You, évoquent davantage la Grosse Pomme, ainsi que Ain’t Misbehavin’ qui marque même le passage décisif de Louis de la Cité du Vent à New York, à l’occasion de la création en 1929 de la revue Hot Chocolates. Pour New York, St. Louis Blues ou Rockin’ Chair peuvent faire l’affaire (mais pourraient représenter n’importe quelle autre ville, tant Louis les trimballa à peu près partout, y compris à Londres, Copenhague ou Paris?!), Tiger Rag peut tout aussi bien évoquer New Orleans et Struttin’ With Some Barbecue délivre plutôt quelques senteurs chicagoanes, mais, là encore, le morceau est resté tellement longtemps au répertoire que… Quant à Hollywood (c’est-à-dire Los Angelès), on ne saisit pas très bien ce que viennent y faire Stomping at the Savoy, I Can’t Give You Anything But Love, Mop Mop, ou Roll ‘Em (alors que Confessin’ aurait mieux convenu), mais The Blue Are Brewin’ et Do You Know What It Means… sont d’actualité, puisque la Première du film est prévue le 26 avril 47 au Saenger Theatre de New Orleans… Et puis, après tout, quelle importance ce gentil méli-mélo?? Ce qui comptait c’est que Louis Armstrong ait pu évoquer ces moments forts de sa carrière, quels qu’aient été les lieux où ils s’étaient déroulés, devant le public exigeant de Carnegie Hall. Ce qui comptait aussi, c’est qu’il l’ait fait à la tête d’une petite formation comme celle du film. Car, ce qui n’est pas sans présager un grand tournant dans un avenir proche, c’est que seule la partie consacrée à Hollywood (en fait, la seconde du concert, après l’entracte) fut exécutée avec la grande formation régulière, sous la direction de Joe Garland. Pour le reste, Satchmo s’était assuré le concours du groupe régulier du clarinettiste (néo orléanais) Edmund Hall, vedette du «?Café Society Uptown?», composée d’Irving Randolph à la trompette, Henderson Chambers au trombone, Charles Bateman au piano, Johnny Williams à la basse et James Crawford, ex-batteur de Jimmie Lunceford. Earl Hines était prévu comme pianiste invité (sans doute pour intervenir sur West End Blues, Save It, Pretty Mama, Basin Street Blues, St. Louis Blues…), mais il ne vint finalement pas. Nul ne sait pourquoi.

Depuis son entrée chez Fletcher Henderson fin 1924, Louis ne s’est plus guère produit qu’au sein d’un grand orchestre (Henderson, puis Erskine Tate, le groupe du «?Sunset Café?» puis du «?Savoy», dirigé par Carroll Dickerson, celui de Luis Russell et l’équipe actuelle, souvent remaniée entre 1942 et 1945, sans parler de la formation européenne si décriée). Les légendaires petits comités des années 1925-28 n’eurent d’existence que dans le cadre des studios du phonographe. A la rigueur fera-t-on une petite exception pour l’orchestre du «?Dreamland?» de son épouse d’alors, Lil, avec lequel il se produisit en rentrant à Chicago fin 1925, puisqu’il s’agissait d’un septette calqué sur le modèle du Jazz Band de King Oliver. Mais cela ne dura que quelques mois… Or, il se trouve que le tournage de New Orleans avec son petit groupe de studio (l’équivalent ni plus ni moins des “Hot Five” et “Hot Seven” de jadis) donna à Satchmo et à son agent l’idée que c’était peut-être là que résidait la solution de leur problème : la reconquête d’un public de plus en plus lointain, fuyant.

Pour toute une série de raisons, les grands orchestres, si appréciés, si populaires, dix ans auparavant, étaient en crise en cette seconde moitié des années 1940. La guerre qui, comme tout évènement majeur et tragique, contribue à modifier les goûts des gens, n’y fut certainement pas pour rien… Il y eut l’usure de la formule et également l’irruption du “be-bop” qui se pratique plutôt en petites ou moyennes formations et passionna les plus jeunes, persuadés d’y découvrir la musique de leur temps. Toujours est-il qu’en 1946-47, les prestations du grand orchestre de Louis ne sont plus payées que 350 $ en semaine et 650 le samedi. Les anciens établissements ferment et les nouveaux se révèlent souvent trop exigus pour accueillir ces musiciens en surnombre. Résultat : les engagements se font plus rares. Difficile, dans ces conditions, de faire tourner la machine. Armstrong n’est d’ailleurs pas le seul à connaître semblables ennuis ; entre 1945 et 1950, nombre de big bands (Fletcher Henderson, Charlie Barnet, Cab Calloway, Earl Hines, Jimmie Lunceford, Don Redman, Artie Shaw, Boyd Raeburn et même Paul Whiteman et Basie) sont dissous. Duke et B.G. ont bien du mal à sauver les leurs…

Le concert de Carnegie Hall se présente donc comme un ballon d’essai : quelle formule aura la faveur du public, le big band habituel ou le septette aux accents dixieland?? A en croire Charles Delaunay présent dans la salle, «?l’orchestre ne convenait pas toujours au style de Louis et les amateurs de “vieux style”, par là ennemis de la grande formation, marquèrent leur mécontentement, avec un manque de tact digne du public de la Salle Pleyel, en quittant leur place avant la fin…» (Jazz Hot n°14). Les jeux sont faits, rien ne va plus (pour le grand orchestre) : Louis Armstrong finira sa carrière comme chef d’un petit groupe régulier. Le «?All-Stars?» est au prochain tournant. Pour nous, il est au prochain volume !

Armstrong a dû suivre scrupuleusement le programme tel qu’il a été conçu et, en compagnie d’Irakli, nous l’avons reconstitué dans sa presque totalité. Deux morceaux n’ont pu être retrouvés, Basin Street Blues (New Orleans) et West End Blue (Chicago). On raconte qu’ils n’étaient point d’une exécution parfaite. Dans la partie big band (Hollywood), nous avons éliminé If I Loved You, chanté par le tendre Leslie Scott sans la moindre intervention armstrongienne, et Mop Mop, solo de percussion par l’impressionnant Sidney Catlett, que Louis conservera comme batteur. Enfin, après You Won’t Be Satisfied chanté par Velma, était prévue l’exécution de The Blues Are Brewin’… qui n’eut pas lieu. Car, à la place, Lady Day, Billie Holiday en personne, fit son entrée et attaqua Do You Know What it Means to Miss New Orleans, accompagnée par le trompettiste. Le coup était évidemment prémédité, mais le public, non prévenu, ne la reconnut pas tout de suite et ne lui fit une ovation qu’après un léger flottement. Bien entendu, rien à voir avec de la promo !... Enfin Roll ‘Em s’en vint clore cette longue et forte manifestation, décisive pour l’avenir. Dizzy Gillespie qui y assistait déclara à Delaunay : «?Louis Armstrong est tout simplement magnifique?»…

L’ultime réunion phonographique du big band se déroula chez RCA New York le 12 mars, mais l’orchestre (seize musiciens et une chanteuse) perdurera encore jusqu’au début de l’été. Cinq titres qui, eux non plus, ne laissèrent pas un souvenir impérissable, même si Satchmo se montre très décontracté sur ces thèmes passe-partout. A noter que le premier, I Wonder, I Wonder, I Wonder, est un morceau différent du I Wonder de janvier 1945 (volume 11)…

Le samedi 26 avril, Louis participa à l’émission publique Saturday Night Swing Show, produite par la chaîne WNEW (565 Fifth Avenue 46th Street, New York City), au cours de laquelle le Maître de Cérémonies, Art Ford, interrogea le trompettiste. On trouvera ici quelques extraits de l’interview (CD 3, plage 19), édités sous le titre Reminiscin’ with Louis sur le (rare) V-Disc 784. Sur la même galette figure également une nouvelle version d’Ain’t Misbahavin’, interprétée avec le concours d’Irving “Roy” Ross, accordéoniste et directeur du petit orchestre maison. Sur le tout aussi rare V-Disc 760, on s’est (à l’époque) livré à un sauvage tripatouillage en montant la version de Do You Know What it Means… exécutée ce 26 avril avec celle du 8 février à Carnegie Hall, afin d’avoir sur la même face, en continuité, la partie Armstrong puis la partie Billie Holiday ! Le plus drôle, c’est que presque personne ne s’est aperçu de la supercherie. Nous avons préféré rétablir l’équilibre. Pour la partie Billie, prière de se reporter à la plage 12 du même CD 3 ! Ah oui : ici, on croise aussi Jack Teagarden et Sidney Catlett. Décidément, tout cela fleure bon un certain “All-Stars”?!...

Daniel NEVERS

Remerciements

Jean-Christophe AVERTY, Philippe BAUDOIN, Olivier BRARD, Jean-Pierre DAUBRESSE, Irakli de DAVRICHEWI, Alain DÉLOT, Yvonne DERUDDER, Jean DUROUX, Pierre LAFARGUE, Clément PORTAIS.

© 2012 Frémeaux & Associés - Groupe Frémeaux Colombini

Louis ARMSTRONG – Vol.12

“It was my first picture. My last, too. Anyway, the picture was finished some kind of way, and I was glad to split the hell out of there and gone. I saw it later – much later. They had taken miles of footage of music and scenes in New Orleans, but none of it was left in the picture. And very damn little of me. I know I wore a white dress for a number I did in the picture. And all that was cut out of the picture. I never made another movie. And I’m in no hurry.”

And that’s what Billie Holiday had to say, in her Lady Sings the Blues autobiography, about that miserable piece of celluloid entitled New Orleans released in 1946. Billie died in 1959 and never made another film. She can be seen in a few short films, of course – the first, in the company of Duke Ellington’s orchestra, dates back to 1933 – and in one dramatic television programme made in 1957, alongside Basie and his band, Hawk, Prez, Ben Webster, Mulligan, Monk… But there was no other “great” film… As for Louis Armstrong, another “star” of this masterpiece worthy of Ed Wood and other turnips combined, he confined himself – disappointed, resigned – to the comment: “What the Hollywood people do is never authentic.” And Louis was no newcomer to the studios…

It’s true that, in most of his previous films, Louis played the role of a trumpeter/singer closely resembling himself… Sometimes, a slight variation turned him into a “janitor” (to use a politically correct word), or a stable-boy with a weakness for a nag called Jeepers Creepers, even an adorable, smiling imp almost entirely destined (already!) to be spliced out of the final cut (Cabin in the Sky). But at least – it was in the contract – at one point or another, his trumpet would blast into the movie… Obviously it’s difficult to imagine Satchmo as a Greek shipping-magnate, a Wall Street shark, Geronimo, or some bloodcurdling gangster à la Scarface. Apart from that, it’s true that in New Orleans he was supposed to be a musician, with a little band playing in a Storyville speakeasy… You can see and hear him play, sing, talk, introduce his musicians etc., and he’s one of the film’s rare moments of grace.

The screenplay, an ambitious one at that, was based on a biographical project which Orson Welles – no less, and woe to the man through whom the Citizen Kane scandal cometh – wanted to film in 1943-44: Horn of Plenty, a film which had the most authentic jazz and dealt with the period from his birth in the South (in the Crescent City in particular), to the turn of the Forties. Purely documentary sequences were supposed to alternate with (and complement) scenes of fiction. Today you can dispute the reality of such a dream-birth in a place that is unique, magical even, considering that the way events actually happened was probably much more complex but, in those days, people needed certainty.

Picked up by United Artists, the subject was given a reworking despite all good sense, and a catastrophe became inevitable. A few years ago, critic Alain Tercinet summed up the massacre by saying: “Victims of all kinds of pressure – to which the birth of McCarthyism wasn’t entirely foreign – they (the studio’s bigwigs) allowed the screenplay written by Herbert Biberman – one of ‘The Hollywood Ten’ – to be ripped to bits, watered down and turned into a melodrama. Bit-players – Arturo de Cordova, Dorothy Patrick –, an inconsistent director, the incongruous irruption of Woody Herman’s orchestra, all contributed to ensure that, once finished, ‘New Orleans’ found itself somewhere diametrically opposed to the original project.” The story should have focused on Louis, Billie, street parades, the closing of Storyville in 1917 for reasons of war and Puritanism… Instead of which, Armstrong found himself in the background, and Billie (naturally), became a maid in the employ of a somewhat has-been opera-singer (Dorothy P.). Not only do you wonder what the devil she was doing there in the first place; you wonder even more why she was made the star. The same goes for Woody Herman: in 1946 his orchestra wasn’t yet the band that rose to fame while revealing amazing soloists. But, whatever, he shouldn’t have been in the film to start with. “Inconsistent” isn’t really strong enough a word to describe the director, Arthur Lubin. “Rubbish”, maybe? There’s nothing in his filmography (an abundant one), to compensate for this mortal sin called New Orleans, especially not his sumptuously grotesque version of The Phantom of the Opera. Any run-of-the-mill Hollywood director – they were crawling out of the woodwork, like Sam Wood or Henry Koster – would have caused less pain. There was no way “The Hollywood Ten” would include Master-Filmmaker Lubin! The “Ten”, need we remind you, was the term designating the victims of the witch-hunt, those film-people banned from the studios and out of a job thanks to the Un-American Activities Committee of Senator Joseph McCarthy. The victims went into exile all over Europe, and among them were the likes of Joseph Losey, Jules Dassin, John Berry, Cy Enfield, and Dalton Trumbo, not to mention the screenwriter Herbert Biberman…

So a lot of music was recorded – too much music, no doubt, especially when you realize the small amount preserved in the end. Fortunately, these pre-recordings (not covered by dialogue or sound-effects) were cut on a lavish series of lacquers – 12” 78s – and were miraculously preserved in rather good condition. And so people who know this film can find here – in their entirety – those excerpts which we thought it might be a good idea to include, even though they almost always tail off before the end: Do You Know What It Means…, Where the Blues Were Born in New Orleans, Farewell to Storyville, West End Blues, Tiger Rag, Basin Street Blues, Milenberg Joys, The Blues Are Brewin’… In addition, you can also lend an ear to a number of other performances which were stupidly binned during the editing: Buddy Bolden Blues, Raymond Street Blues played by a quartet, Shimme-Sha-Wabble, Ballin’ the Jack, Maryland, My Maryland, King Porter Stomp, Flee as a Bird, When the Saints, even a few bars of Brahms (Berceuse)… Louis hadn’t yet recorded some of these pieces. Also worth a mention: for three of these pieces there are two versions, one quick and one slow (Buddy Bolden Blues, Dippermouth Blues, Mahogany Hall Stomp), and someone also took the precaution of having the trumpeter record some upper-register notes just in case… But it seems someone decided not to use them.

Armstrong’s regular big band was only rarely put to contribution: you can, however, hear it on Endie (Billie’s name in the film) and The Blues Are Brewin’ sung by Lady Day – or at least you can listen to it here, because it was left out of the final cut. These two pieces, of course, have been carefully chopped to bits, like almost all the others…

Speaking of which – the other pieces –, the people responsible for darkened theatres resorted to one of those small-groups reputedly behind the birth of jazz in the dives of the Crescent City at the turn of the last century. In short, those Hot Five and Hot Seven formations exclusively set up for recordings by Louis between the end of 1925 and the end of 1928 (cf. Volumes 3-5, FA1353, 1354, 1355). It so happens that one of the musicians in those first-draft Hot Fives – trombonist Edward “Kid” Ory – had been playing quite a lot out on the West Coast in those days. He’d even made his first records there in 1922. And Armstrong had played cornet in his group in New Orleans between 1918 and 1919. So Kid Ory was consequently enrolled. With him he brought his banjo- & guitar-player Bud Scott, another local boy alongside whom Louis had appeared in 1923 in the days of King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band. He’s the one who, in the OkeH version of Dippermouth Blues, yells out the legendary words “Oh, play that thing!” (cf. Vol. 1 – FA1351). And here, twenty-three years later, he does it again. It must have rejuvenated him… But not for long: he died in 1949. Clarinettist Barney Bigard is a local boy, too, and he also played with King Oliver (but in 1926-27, after Armstrong’s departure). He went on to spend fifteen years with Duke Ellington. Louis and Barney still took part in one quasi-clandestine session in 1927 and, closer to this period, they found themselves side by side on the stage of New York’s Metropolitan Opera during the great Esquire concert on January 18th 1944 (cf. Vol. 11 – FA1361). As for Zutty Singleton – just as much a Louisiana boy as the former – he, along with Earl Hines, had been one of Satchmo’s favourite sidemen in the latter part of the Twenties. He’s the one supplying the rhythm-foundations – solid yet subtle – on these 1928 Hot Five recordings. He was also on the New York session (May 27th 1940) – a small-group date – with Bechet (cf. Vol. 9). Their renewed acquaintance was, alas, much too short…

The two others, pianist Charlie Beal and bassist George “Red” Callender – weren’t Southerners. Beal, however, worked and recorded with Louis in Chicago in 1933. Callender, the youngest, was capable of performing in any jazz context, and therefore extremely solicited as a studio musician, with many Californian films to his credit. This was an excellent little group for a turkey of a film that perhaps didn’t deserve such talent. That said, don’t miss it if you get the chance – with reserves, of course: it’s still the only place in the whole domain of cinematography where you can hear Louis Armstrong and Billie Holiday the most.

Billie. She was often paired with musicians younger than Satchmo, like Lester Young and the Basie crew, and it’s sometimes been mooted that she might not have felt totally at ease alongside the leader of an older school of jazz. As a matter of fact, Billie herself made it clear that, of all the “elders” she admired and whose records she possessed, two were unconditional favourites of hers: Bessie Smith and… Louis Armstrong (probably the singer more than the trumpeter, although they’re inseparable!) And another thing: when she introduces the band, at the beginning of the film over Where the Blues Were Born…, (as on the good old Gut Bucket Blues of November 1925), Louis states that his instrument is an “old cornet”. And on the screen, it’s indeed a cornet which he puts to his lips… even though it’s a trumpet you can hear on the soundtrack. Gut Bucket Blues seems to be the tune with which Armstrong brought his cornet-period to an end, and began a new era playing the trumpet (cf. Vol. 3). By 1932-33, Satchmo himself had no clear memories of exactly who told Hugues Panassié that the changeover dated probably from late ‘26 or early ‘27, but later (years later) he contested that statement. One thing is sure in any case: once he’d adopted the trumpet, Louis never went back to the “old cornet” of his early days. He kept one as a souvenir, and gave the others to musicians who were still learning.

On September 6th 1946, just when this imposing series of pre-recordings was beginning, a session was organized at RCA studios in Los Angeles by the French label Swing managed by Charles Delaunay; he’d gone to The States to bolster his label’s catalogue and gather information destined for his jazz discography… The session wasn’t aimed at recording pieces specially composed for the film, but held so that they could cut four titles which Louis hadn’t yet put on wax. Retained from that session were two hits from the end of the Twenties, Sugar and I Want a Little Girl, plus two blues pieces, Blues for Yesterday and Blues in the South. It was yet another small-group session, and Louis got his hands on Bigard, Singleton, Beal and Callender again, but summoned trombonist Vic Dickenson and guitarist Allen Reuss; Beal was replaced on the blues titles by Leonard Feather… These sides were first released in France in the course of 1947 (on the Swing label) before Victor published them in The United States. One of the two records carried the banner “Louis Armstrong and His Hot Seven”, and the other “Louis Armstrong and His Hot Six”: there were indeed seven of them, but the boss was named separately on the latter, while the first record just counted everyone, boss included. You could say he was numbered twice… Whatever, it was true that quite some time had elapsed since Armstrong had made a couple of records with a small group!

The studios saw Louis again on October 17th, this time for recordings of (new) songs from the film for RCA, not that it prevented these from a European release either – only this time they were dealt with by His Master’s Voice and Gramophone. In fact, the records were half and half: for Endie and The Blues Are Brewin’ the big band – on its way out of existence – was requisitioned; and for Do You Know What it Means… and Where the Blues Were Born…, the small-group from the film was summoned; the same goes for Mahogany Hall Stomp, not a new piece exactly, because it’s also to be found in the reels of this delightful Hollywood fantasy. All the protagonists are present except for Zutty Singleton, with whom Louis had had words… They would kiss and make up, but hardly worked together again. To replace Zutty, a call was sent out to Minor “Ram” Hall, a New Orleans drum-veteran and ex-alumnus of King Oliver’s Jazz Band; he also worked with Kid Ory in the Forties.

New Orleans and its consequences covered a sizeable part of the last six months of 1946. The first semester was seemingly a little calmer. The war was over (they said), but many recordings made by the AFRS – which provide the substance of the preceding period (1943-1945, cf. Vols. 10 & 11) – continued unabated. However, it does seem that Louis Armstrong didn’t take part in these early on in the year. On the other hand, he was indeed inside RCA Studios in New York as early as January 10th, together with a few of the laureates from the Esquire Readers’ Poll: after the strike and the war, the time had come to return to old habits and do a few souvenir-sides between friends. There were only two (sides, not friends) that day in January, but the line-up was quite special: Louis, naturally, Ellington (who introduces the first piece, Long, Long Journey, with carefully hollow words) and his alter ego Billy Strayhorn, three other Ellingtonians – clarinettist Jimmy Hamilton, the alto of Johnny Hodges, and drummer Sonny Greer –, Charlie Shavers on trumpet, “Don” Byas on tenor, Remo Palmieri on guitar, and bassist “Chubby” Jackson. On Snafu, the second title, Louis is happy just to take a fine solo, while Neal Hefti, the arranger-trumpeter, replaces Shavers. Two more arias would be recorded the following day with basically the same personnel – minus Armstrong.

Satchmo was very much in evidence a week later, however (January 18th), and he wasn’t alone either, because he was there to fence with Ella Fitzgerald on two songs, You Won’t Be Satisfied and The Frim Fram Sauce, with a studio band placed under the baton of bassist Bob Haggart. And so it came to pass that Satchmo met Ella (on record) before he crossed paths with Billie. You have to say that they’re close cousins in their inspiration, and indeed they would have more than one occasion to meet up again elsewhere – and you can’t say the same for Lady Day… Louis and Ella were recording exclusively for Decca at the time, but for the trumpeter it would be his last recording (on an exclusive basis, at least: he’d cut many more sides for the firm he’d signed with in 1935, but from then on he would be protecting his right to deal with different labels as and when the opportunity appeared). As you might imagine, his manager Joe Glaser was to take care of the details… and in 1946-47, as you can see, it was RCA-Victor who took the biscuit.

The first official session for the aforesaid label came on April 27th, and reintroduced the big band together with Velma Middleton, the plump chanteuse – and sometime-specialist in doing the splits – whom some people were quick to describe as an “annoying mademoiselle pushing out vocals of dubious pitch during half the record (No Variety Blues).” But Armstrong, apparently, had a thing going with her… He also sings, of course, notably on Whatta Ya Gonna Do and especially on the superb version (for commercial release) of Back O’ Town Blues, a piece with two older versions to our knowledge, for AFRS in 1943, and also at the Esquire concert at “The Met” in 1944 (cf. Vols. 10 & 11). The session was completed by two other (mostly forgotten) titles: Joseph ‘n’ his Brudders and Linger in My Arms a Little Longer. Following the session, and after the summer season (mainly spent at The Regal and The Savoy in Chicago), the whole bunch went off to Hollywood.

Between September and November 1946, Louis and his crews (large and small) were hardly out of work, thanks to sessions for Swing, filming and pre-recordings (two whole months), and a new RCA session. Their nights in California were also often taken up with concerts and dancehall-appearances. When Louis went back East at the end of the year with the big band, he played at The Apollo and got ready for a great concert – with four thematic parts – that was scheduled for Carnegie Hall at 5.30pm precisely on Saturday, February 8th 1947. Note that Carnegie Hall – albeit an illustrious, legendary stage – had only been rarely occupied until then.

The concert’s four “thematic parts” mentioned above supposedly referred to the cities in which Armstrong had made a name for himself at some point or other during his career: New Orleans, Chicago, New York and Hollywood. In reality, the organizers made something of a muddle of it all: if one admits that New Orleans can be represented by the marches played at its funerals (Flee As a Bird, Didn’t He Ramble?), plus Mahogany Hall Stomp, Basin Street Blues (unavoidable areas of the Crescent City), and even Dippermouth Blues and Muskrat Ramble (which could just as well have illustrated his Chicago days), one can have reservations about the inclusion of the three other places the organizers had in mind. Take Chicago: West End Blues and Save It, Pretty Mama are indeed in the right place, and correspond to the year 1928; on the other hand, Black and Blue, Lazy River and You Rascal You have more to do with the Big Apple, like Ain’t Misbehavin’, which even marks Armstrong’s decisive move from the Windy City to New York (on the occasion of the first performance, in 1929, of the revue Hot Chocolates.) Take New York: St. Louis Blues or Rockin’ Chair do the trick (although they could be representative of anywhere, as Louis packed them in his bags when visiting London, Paris, even Copenhagen!); Tiger Rag could just as well fit in for New Orleans, and Struttin’ With Some Barbecue smells more like Chicago, but even then, the piece was in his repertoire for so long that…. As for Hollywood (i.e. Los Angeles), you don’t really know what Stomping at the Savoy, I Can’t Give You Anything But Love, Mop Mop or Roll ‘Em have to do with it (Confessin’ would have been a better match), but The Blues Are Brewin’ and Do You Know What It Means… are topical enough, because the premiere of the film was scheduled for April 26th 1947 at the Saenger Theatre in New Orleans… What does it matter, anyway? It was important for Louis Armstrong to have the chance to recall such highlights in his career – wherever they took place – in front of Carnegie Hall’s demanding audience. It was also important that he might do so fronting a small-group like that in the film. The fact is – and it’s not unrelated to an imminent change of some importance – that only the part of the concert devoted to Hollywood (actually the second part, just after the intermission) was executed with Louis’ regular big-band, with Joe Garland conducting. As for the rest, Satchmo was assisted by the regular band of clarinettist Edmund Hall (from New Orleans, the star of the “Café Society Uptown”), with Irving Randolph on trumpet, Henderson Chambers (trombone), Charles Bateman (piano), Johnny Williams (bass), and Jimmie Lunceford’s former drummer, James Crawford. Earl Hines had been planned as guest-pianist (no doubt to contribute to West End Blues, Save It, Pretty Mama, Basin Street Blues, St. Louis Blues…), but he never showed up. Nobody knows why.

Ever since joining Fletcher Henderson at the end of 1924, Louis had hardly ever appeared without a large orchestra around him (Henderson, then Erskine Tate, the formations of The Sunset Café and The Savoy led by Carroll Dickerson, then Luis Russell, the current crop of musicians, often changing between 1942 and 1945, not to mention the European version, so often decried…) The legendary small-groups of the 1925-28 years only existed inside studios for phonographic purposes. You might make an exception of the Dreamland orchestra led by his then-wife, Lil Hardin, with which Louis appeared on his return to Chicago at the end of 1925, because it was a septet based on the model of King Oliver’s Jazz Band. But that one only lasted a few months… It so happens that the filming of New Orleans with his studio small-group – the equivalent of the Hot Five and Hot Seven of the old days, no more, no less – gave Satchmo and his agent the idea that here, perhaps, lay the solution to their problem, i.e. how to re-conquer an audience that was growing (fleeing) more distant.

For a whole host of reasons, big bands – all of them appreciated, and popular, some ten years earlier – found themselves in a crisis during this latter half of the Forties. War, like any major, tragic event, brings change in public tastes, and the war which had just ended was no different. The big band formula was wearing thin, too, and then there was also “bebop”: it was erupting everywhere, it was played by small-to-medium-sized groups, and it was thrilling young people to bits because they were convinced they were discovering the music of their times. The fact is, in 1946-1947 Louis’ big band was only being paid $350 for a weekday appearance, $650 on a Saturday. Older establishments were closing, and the new ones were too cramped for a large number of musicians… Result: bookings were scarce. Under such conditions, oiling a large machine became complicated. Nor was Armstrong the only one to feel the pinch: between 1945 and 1950, a large number of orchestras bit the dust: Fletcher Henderson, Charlie Barnet, Cab Calloway, Earl Hines, Jimmie Lunceford, Don Redman, Artie Shaw, Boyd Raeburn, even Paul Whiteman and Basie. As for Duke and Benny, they were having a hard time fighting the flames…

So the Carnegie Hall concert resembled a balloon sent up to test the wind: which formula would win favour with the public, the usual “big band”, or the septet with a Dixie accent? Charles Delaunay was in the room: “The orchestra didn’t always suit Louis’ style, and the ‘old style’ fans, by definition the enemies of large groups, showed their dissatisfaction with a lack of tact worthy of the Salle Pleyel [in Paris] by leaving their seats before the end,” wrote Delaunay in Jazz Hot N°14. The chips were down for big bands: Louis Armstrong would end his career leading a regular small-group. The solution to his problem was his “All-Stars”, his next step (and our next volume).

Armstrong had to scrupulously follow the programme as written, and together with Irakli we’ve reconstituted the concert in toto, or almost, as two pieces are still missing: Basin Street Blues (New Orleans) and West End Blue (Chicago). The story goes that they weren’t perfect performances anyway. From the big-band part (Hollywood), we’ve eliminated If I Loved You, sung by the tender Leslie Scott without any assistance from Armstrong, and Mop Mop, a percussion solo by the impressive Mr. Sidney Catlett, whom Louis kept as drummer. Finally, after Velma’s song You Won’t Be Satisfied, the programme mentioned a performance of The Blues Are Brewin’… which didn’t happen. Instead, Lady Day – Billie Holiday in person – stepped out and launched into Do You Know What it Means to Miss New Orleans accompanied by the trumpeter. Obviously a premeditated surprise, but the audience didn’t know that; nor did they recognize her at first, and only gave her an ovation after some wavering. It might cross your mind that this was a promotional stunt, of course… The lengthy, moving proceedings come to a close with Roll ‘Em, justifying the whole business as a decisive move in Louis’ future career. Dizzy Gillespie was in the audience, too, and he said to Delaunay: “Louis Armstrong is quite simply magnificent.”

The big band’s final reunion on record took place at RCA in New York on March 12th, but the orchestra – sixteen musicians plus vocalist – would hang on until the beginning of the summer. They put down five titles which, no more than the others, hardly constitute an indelible souvenir, even if Satchmo shows himself extremely relaxed on these routine titles. Note that the first, I Wonder, I Wonder, I Wonder, is a different tune from the I Wonder dated January 1945 (cf. Vol. 11).

On Saturday April 26th Louis took part in a live broadcast of the Saturday Night Swing Show produced by WNEW (565 Fifth Avenue at 46th Street, New York City), during which the MC, Art Ford, put a few questions to the trumpeter. You can find excerpts from the interview here (CD3, track 19), which were released on the (rare) V-Disc 784 under the title Reminiscin’ with Louis. The same disc features a new version of Ain’t Misbehavin’, performed with the assistance of Irving “Roy” Ross, an accordionist who led the little house-band. The just-as-rare V-Disc 760 fell victim (at the time) to some wild tomfoolery in which the version of Do You Know What it Means… (performed that April 26th), was put together with the February 8th version from Carnegie Hall, with the aim of having the Armstrong part continuing into the Billie Holiday part on a single side! And that’s not half as funny as the fact that almost nobody noticed the splice. We thought it better to straighten matters out. For the Billie part, listen to track 12 on this same CD3. Ah, I nearly forgot: you can hear Jack Teagarden and Sidney Catlett here, too. All of which, decidedly, has a certain “All-Stars” flavour!

Daniel NEVERS

© 2012 Frémeaux & Associés - Groupe Frémeaux Colombini

DISQUE / DISC 1 (1946)

ESQUIRE ALL-AMERICANS AWARD WINNERS

Louis ARMSTRONG (tp, voc)?; Charlie SHAVERS (tp sur/on 1)?; Neal HEFTI (tp sur/on 2)?; Jimmy HAMILTON (cl)?; Johnny HODGES (as)?; Carlos W. “Don” BYAS (ts)?; Duke ELLINGTON (p, pres)?; Billy STRAYHORN (p sur/on 2)?; Remo PALMIERI (g)?; Grieg “Chubby” JACKSON (b)?; William “Sonny” GREER (dm)?; Leonard FEATHER (arr).

New York City, 10/01/1946

1. LONG LONG JOURNEY (L.Feather)

(RCA-Victor 40-4001/mx.PD6-VC-5020-1) 4’30

2. SNAFU (L.Feather)

(RCA-Victor 40-4001/mx.PD6-VC-5021-1) 4’12

LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND ELLA FITZGERALD with BOB HAGGART’S ORCHESTRA

Louis ARMSTRONG (tp, voc)?; Billy BUTTERFIELD (tp)?; Bill STEGMEYER (cl, as)?; George KOENIG (as)?; Jack GREENBERG, Art DRELINGER (ts)?; Milton SCHATZ (bar sax)?; Joe BUSHKIN (p)?; Danni PERRI (g)?; Trigger ALPERT (b)?; William “Cozy” COLE (dm)?; Ella FITZGERALD (voc)?; Bob HAGGART (dir). New York City, 18/01/1946

3. YOU WON’T BE SATISFIED(F.James-L.Stock) (Decca 23496/mx.W 73285-A) 2’52

4. THE FRIM FRAM SAUCE (J.Ricardel-R.Evans) (Decca 23496/mx.W 73286-A) 3’12

LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND HIS ORCHESTRA

Louis ARMSTRONG (tp, voc)?; Ed MULLENS, Ludwig JORDAN, William “Chifie” SCOTT, Andrew “Fatso” FORD (tp)?; Adam MARTIN, Norman POWE, Al COBB, Russell “Big Chief” MOORE (tb)?; Don HILL, Amos GORDON (as)?; John SPARROW (ts)?; Joe GARLAND (ts, ldr)?; Ernest THOMPSON (bar sax)?; Ed SWANSTON (p)?; Elmer WARNER (g)?; Arvell SHAW (b)?; George “Butch” BALLARD (dm)?; Velma MIDDLETON (voc). New York City, 27/04/1946

5. LINGER IN MY ARMS A LITTLE LONGER (H.Magdison) (RCA-Victor 20-1912/mx.D6-VB-1736-1) 2’58

6. WHATTA GONNA DO? (Skylarck-Lewis) (RCA-Victor 20-1891/mx.D6-VB-1737-1) 2’54

7. NO VARIETY BLUES (L.Armstrong-Fairbanks) (RCA-Victor 20-1891/mx.D6-VB-1738-2) 2’53

8. JOSEPH AND HIS BRUDDERS (L.Armstrong-Bell) (RCA-Victor 20-2612/mx.D6-VB-1739-1) 3’01

9. BACK O’ TOWN BLUES (L.Amstrong-L.Russell) (RCA-Victor 20-1912/mx.D6-VB-1740- ) 3’15

LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND HIS HOT SEVEN (10 & 12) / HIS HOT SIX (11 & 13)

Louis ARMSTRONG (tp, voc)?; Victor “Vic” DICKENSON (tb)?; Barney BIGARD (cl)?; Charlie BEAL (p)?; Allen REUSS (g)?; Red CALLENDER (b)?; Zutty SINGLETON (dm). Los Angeles, 6/09/1946

10. I WANT A LITTLE GIRL (Moll-Mencher) (Swing 223/mx.D6-VB-2149-1) 3’00

11. SUGAR (M.Pinkard-Mitchell-Alexander) (Swing 251/mx.D6-VB-2150-1) 3’23

12. BLUES FOR YESTERDAY (L.Carr) (Swing 223/mx.D6-VB-2151-1) 2’35

13. BLUES FOR THE SOUTH (W.Johnstone) (Swing 251/mx.D6-VB-2152-1) 3’01

“NEW ORLEANS” (UA film) PRÉ-ENREGISTREMENTS / PRE-RECORDINGS

Louis ARMSTRONG (tp, voc)?; Edward “Kid” ORY (tb)?; A. Barney BIGARD (cl)?; Charlie BEAL (p)?; Arthur “Bud” SCOTT (g)?; George “Red” CALLENDER (b)?; Arthur “Zutty” SINGLETON(dm)?; plus George KENNEDY, Charles YUKL (tp)?; Ellis RONKA, Murray McEACHERN (tb)?; Robert HENNON, John HAMILTON (cl, ts)?; Phillip MURROW (bars)?; George E. GREEN (tuba)?; John BOUDREAUX (dm).

Hollywood (Studio & Artists Recorders), entre/between 5/09 & 8/10/1946

14. FLEE AS A BIRD (trad)/WHEN THE SAINTS GO MARCHIN’ IN (trad) (TMX 1-3 & 3A-5) 3’08

Septette comme pour 14 / Septet as for 14. Moins les 9 musiciens de studio / minus the 9 studio musicians.

Mêmes lieu & date / Same place & date

15. WEST END BLUES (J.Oliver) (TMX 7-3) 2’49

16. TIGER RAG (D.J.LaRocca) (TMX 33-3) 2’21

17. WHERE THE BLUES WERE BORN IN NEW ORLEANS (Capleton-Dixon) (TMX 42- ) 4’36

18. BUDDY BOLDEN BLUES (2 takes) (F.Morton) (TMX 53 G1-3&G1-4) 1’44

19. BASIN STREET BLUES (Sp.Williams) (TMX 53 S41/42) 4’42

20. RAYMOND STREET BLUES plus 4 HIGH NOTES ON TRUMPET

(L.Armstrong) (TMX 53 G2-3) 1’24

21. MARYLAND, MY MARYLAND (trad) (TMX 81 ?) 2’59

Louis ARMSTRONG (tp) & prob. Arthur SCHUTT (p)

Mêmes lieu & date / Same place & date

22. BRAHMS’ LULLABY (J.Brahms) (TMX 30 B-2) 0’45

Septette comme pour 15 à 21 / Septet as for 15 to 21. Billie HOLIDAY & chœur/choir (voc)

Mêmes lieu & date / Same place & date

23. FAREWELL TO STORYVILLE (Good Time Flat Blues)

(C.Williams) (TMX 84) 3’13

DISQUE / DISC 2 (1946-1947)

“NEW ORLEANS” (UA film) PRÉ-ENREGISTREMENTS / PRE-RECORDINGS

Louis ARMSTRONG (tp, voc)?; “Kid” ORY (tb)?; A. Barney BIGARD (cl)?; Charlie BEAL(P)?; A. “Bud” SCOTT (g)?; George “Red” CALLENDER (b)?; A. “Zutty” SINGLETON (dm). Hollywood (Studio & Artists Recorders), entre/between 5/09 & 8/10/1946

1. MILENBERG JOYS (P.Mares-L.Roppolo-F.Morton)

(TMX 62-4) 1’54

Septette comme pour 1 / Septet as for 1. Plus Thomas “Mutt” CAREY (tp) & Eli “Lucky” THOMPSON (ts).

Mêmes lieu & date / Same place & date

2. DIPPERMOUTH BLUES (lent/slow)

(J.Oliver-L.Armstrong) (TMX 120-1) 1’21

3. DIPPERMOUTH BLUES (rapide/fast) (J.Oliver-L.Armstrong) (TMX 120-4) 1’33

4. SHIMME-SHA-WABLE (S.Williams) (TMX 130-1) 2’04

5. BALLIN’ THE JACK (C.Smith) (TMX 131-2) 2’06

6. KING PORTER STOMP (F.Morton) (TMX 149-2) 2’32

7. MAHOGANY HALL STOMP (lent/slow) (S.Williams) (TMX 183-1) 3’27

8. MAHOGANY HALL STOMP (rapide/fast) (S.Williams) (TMX 182-5) 3’32

LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND HIS ORCHESTRA

Louis ARMSTRONG (tp, voc)?; Robert BUTLER, Louis GRAY, Ed MULLENS, Andrew “Fatso” FORD (tp)?; Russell “Big Chief” MOORE, Wadder WILLIAMS, Nat ALLEN, James WHITNEY (tb)?; Don HILL, Amos GORDON (as)?; John SPARROW (ts)?; Joe GARLAND (ts, dir)?; Ernest THOMPSON (bars)?; Earl MASON (p)?; Elmer WARNER (g)?; Arvell SHAW (b)?; Edmund McCONNEY (dm)?; Billie HOLIDAY (voc). Mêmes lieu & date / Same place & date

9. THE BLUES ARE BREWIN’ (L.Alter-E.de Lange) (TMX 140 ?) 3’40

10. ENDIE (L.Alter-E.de Lange) (TMX 141-A4) 2’19

Formation comme pour 2 à 8 / Personnel as for 2 to 8. Moins/minus Mutt CAREY & L. THOMPSON ; plus Billie HOLIDAY. Mêmes lieu & date / Same place & date

11. DO YOU KNOW WHAT IT MEANS TO MISS NEW ORLEANS ? (L.Alter-E.de Lange) (TMX ? ) 1’44

LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND HIS ORCHESTRA

Formation comme pour 9 & 10 / Personnel as for 9 & 10. Moins/minus B. HOLIDAY. Los Angeles, 17/10/1946

12. ENDIE (L.Alter-E.de Lange) (RCA-Victor 20-2087/mx.D6-VB-2190- ) 2’50

13. THE BLUES ARE BREWIN’ (L.Alter-E.de Lange) (RCA-Victor test/mx.D6-VB-2191- ) 2’55

LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND HIS DIXIELAND SEVEN

Louis ARMSTRONG (tp, voc)?; “Kid” ORY (tb)?; Barney BIGARD (cl)?; Charlie BEAL (p)?; “Bud” SCOTT (g)?; “Red” CALLENDER (b)?; Minor “Ram” HALL (dm). Los Angeles, 17/10/1946

14. DO YOU KNOW WHAT IT MEANS TO MISS NEW ORLEANS?(L.Alter-E.de Lange)

(RCA-Victor 20-2087/mx.D6-VB-2192-1) 2’59

15. WHERE THE BLUES WERE BORN IN NEW ORLEANS (Capleton-Dixon)

(RCA-Victor 20-2088/mx.D6-VB-2193-1) 3’06

16. MAHOGANY HALL STOMP (S.Williams) (RCA-Victor 20-2088/mx.D6-VB-2194-2) 2’55

LOUIS ARMSTRONG with EDMUND HALL and his Café Society Uptown Orchestra

Louis ARMSTRONG (tp, voc)?; Irving RANDOLPH (tp)?; Henderson CHAMBERS (tb)?; Edmund HALL (cl, ldr)?; Charles BATEMAN (p)?; Johnny WILLIAMS (b)?; James CRAWFORD (dm).

New York City (Carnegie Hall Concert), 8/02/1947

17. FLEE AS A BIRD (trad) & OH ! DIDN’T HE RAMBLE ?

(trad) (acetate) 3’10

18. DIPPERMOUTH BLUES (J.Oliver-L.Armstrong)

(acetate) 2’12

19. MAHOGANY HALL STOMP (S.Williams)

(acetate) 2’50

20. MUSKRAT RAMBLE (Ed Ory)

(acetate) 2’20

21. BLACK AND BLUE (T.W.Waller-A.Razaf)

(acetate) 4’20

22. LAZY RIVER (S.Arodin-H.Carmichael)

(acetate) 3’20

23. YOU, RASCAL YOU (S.Theard) (acetate) 3’35

DISQUE / DISC 3 (1947)

LOUIS ARMSTRONG with EDMUND HALL and his Café Society Uptown Orchestra

Louis ARMSTRONG (tp, voc)?; Irving RANDOLPH (tb)?; Henderson CHAMBERS (tb)?; Edmund HALL (cl, ldr)?; Charles BATEMAN (p)?; Johnny WILLIAMS (b)?; James CRAWFORD (dm). New York City (Carnegie Hall Concert), 8/02/1947

1. SAVE IT, PRETTY MAMA (Don Redman) (acetate) 2’55

2. AIN’T MISBEHAVIN’ (T.W.Waller-A.Razaf) (acetate) 2’55

3. St. LOUIS BLUES (W.C.Handy) (acetate) 2’51

4. ROCKIN’ CHAIR (H.Carmichael) (acetate) 4’55

5. TIGER RAG (D.J.LaRocca) (acetate) 4’34

6. CONFESSIN’ (That I Love You) (Neiburg-Dougherty-Reynolds) (acetate) 4’10

7. STRUTTIN’ WITH SOME BARBECUE (Lil Hardin) (acetate) 1’45

LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND HIS ORCHESTRA

Louis ARMSTRONG (tp, voc)?; Thomas GRIDDER, Robert BUTLER, Ed MULLENS, William “Chifie” SCOTT (tp)?; Alton “Slim” MOORE, Russell “Big Chief” MOORE, James WHITNEY (tb)?; Arthur DENNIS, Amos GORDON (as)?; John SPARROW, Eli “Lucky” THOMPSON (ts)?; Joe GARLAND (ts, dir)?; Ernest THOMPSON (bars)?; Earl MASON (p)?; Elmer WARNER (elg)?; Arvell SHAW (b)?; Sidney CATLETT (dm)?; Velma MIDDLETON (voc sur/on 11)?; Billie HOLIDAY (voc sur/on 12). New York City (Carnegie Hall Concert), 8/02/1947

8. Theme & STOMPIN’ AT THE SAVOY (B.Goodman-E.Sampson-A.Razaf) (acetate) 3’37

9. I CAN’T GIVE YOU ANYTHING BUT LOVE (McHugh-Fields) (acetate) 2’53

10. BACK O’ TOWN BLUES (L.Armstrong-L.Russell) (acetate) 4’45

11. YOU WON’T BE SATISFIED (F.James-L.Stock) (acetate) 3’40

12. DO YOU KNOW WHAT IT MEANS TO MISS NEW ORLEANS? (L.Alter-E.de Lange) (acetate) 4’16

13. ROLL ‘EM (M.L.Williams) (acetate) 1’43

LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND HIS ORCHESTRA

Formation comme pour 8 à 13 / Personnel as for 8 to 13. Plus Wadder WILLIAMS (tb) ; James “Coatsville” HARRIS (dm) remplace/replaces S. CATLETT. New York City, 12/03/1947

14. I WONDER, I WONDER, I WONDER (D.Hutchins) (RCA-Victor 20-2228/mx.D7-VB-647-1) 2’32

15. I BELIEVE (S.Kahn-J.Styne) (RCA-Victor 20-2240/mx.D7-VB-648-1) 2’58

16. WHY DOUBT, MY LOVE? (L.Armstrong-M.Mercer) (RCA-Victor test/mx.D7-VB-649- ) 3’19

17. IT TAKES TIME (A.Korb) (RCA-Victor 20-2228/mx.D7-VB-650-1) 2’37

18. YOU DON’T LEARN THAT IN SCHOOL (R.Alfred-M.Fisher) (RCA-Victor 20-2240/mx.D7-VB-651-1) 2’41

“SATURDAY NIGHT SWING SHOW” (radio/broadcast WNEW)

Louis ARMSTRONG (tp, voc)?; Jack TEAGARDEN (tb)?; Irving “Roy” ROSS (acc)?; Nicky TAGG (p)?; Al CAIOLA (g)?; poss. Jack LESBERG (b)?; Sidney CATLETT (dm)?; Art FORD (mc). New York City, 26/02/1947

19. REMINISCIN’ WITH LOUIS (Interview par/by Art FORD) (V-Disc 784/mx.JB-468) 1’27

20. AIN’T MIBEHAVIN’ (T.W.Waller-A.Razaf) (V-Disc 784/mx.JB-455) 3’00

21. DO YOU KNOW WHAT IT MEANS TO MISS NEW ORLEANS ? (L.Alter-E.de Lange)

(V-Disc 780/mx.JB-359) 4’15

«?Ce n’est jamais authentique ce que font les gens d’Hollywood. Ils ne manquent jamais de choisir le comédien avec un physique et un jeu aux antipodes du personnage dont ils retracent la vie?».

Louis Armstrong

“What the Hollywood people do is never authentic. They always choose the actor whose looks and acting are on the other side of the world from the character whose life-story they’re telling.”

Louis Armstrong

Les intégrales Frémeaux & Associés réunissent généralement la totalité des enregistrements phonographiques originaux disponibles ainsi que la majorité des documents radiophoniques existants afin de présenter la production d’un artiste de façon exhaustive. L’Intégrale Louis Armstrong déroge à cette règle en proposant la sélection la plus complète jamais éditée de l’œuvre du géant de la musique américaine du XXe siècle, mais en ne prétendant pas réunir l’intégralité de l’œuvre enregistrée.

CD THE COMPLETE LOUIS ARMSTRONG INTEGRALE LOUIS ARMSTRONG VOLUME 12 NEW ORLEANS 1946-1947, LOUIS ARMSTRONG © Frémeaux & Associés 2013 (frémeaux, frémaux, frémau, frémaud, frémault, frémo, frémont, fermeaux, fremeaux, fremaux, fremau, fremaud, fremault, fremo, fremont, CD audio, 78 tours, disques anciens, CD à acheter, écouter des vieux enregistrements, albums, rééditions, anthologies ou intégrales sont disponibles sous forme de CD et par téléchargement.)