- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

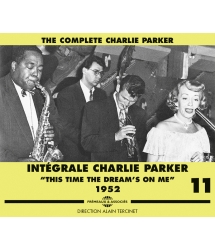

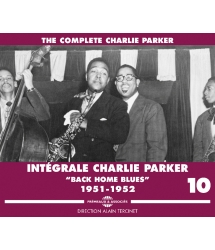

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

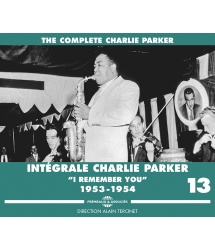

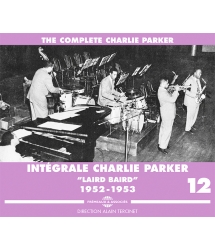

“LAIRD BAIRD” 1952-1953

CHARLIE PARKER

Ref.: FA1342

Artistic Direction : ALAIN TERCINET

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Total duration of the pack : 3 hours 38 minutes

Nbre. CD : 3

“LAIRD BAIRD” 1952-1953

“LAIRD BAIRD” 1952-1953

“Charlie Parker lifted jazz music off the dance floor and into the stratosphere !” Joe LOVANO

The aim of 'The Complete Charlie Parker', compiled for Frémeaux & Associés by Alain Tercinet, is to present (as far as possible) every studio-recording by Parker, together with titles featured in radio-broadcasts. Private recordings have been deliberately omitted from this selection to preserve a consistency of sound and aesthetic quality equal to the genius of this artist.

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1The Song Is YouCharlie Parker QuartetO. Hammerstein II00:03:011952

-

2Laird BairdCharlie Parker QuartetCharlie Parker00:02:481952

-

3KimCharlie Parker QuartetCharlie Parker00:03:011952

-

4Kim (Master)Charlie Parker QuartetCharlie Parker00:03:011952

-

5Cosmic Rays (Master)Charlie Parker QuartetCharlie Parker00:03:071952

-

6Cosmic RaysCharlie Parker QuartetCharlie Parker00:03:201952

-

7CompulsionCharlie Parker SextetMiles Davis00:05:461953

-

8Serpent's Tooth 1Charlie Parker SextetMiles Davis00:07:021953

-

9Serpent's Tooth 2Charlie Parker SextetMiles Davis00:06:191953

-

10‘Round MidnightCharlie Parker SextetTheolonius Monk00:07:081953

-

11Intro / Cool BluesCharlie Parker and Jazz Workshop All StarsCharlie Parker00:02:261953

-

12Bernie's TuneCharlie Parker and Jazz Workshop All StarsB. Miller00:03:191953

-

13Don't Blame MeCharlie Parker and Jazz Workshop All StarsD. Fields00:03:291953

-

14Wahoo / ClosingCharlie Parker and Jazz Workshop All StarsB. Harris00:03:571953

-

15OrnithologyCharlie Parker and Jazz Workshop All StarsB. Harris00:04:401953

-

16Embraceable YouCharlie Parker and Jazz Workshop All StarsG et I. Gershwin00:03:461953

-

17Your Father's MoustacheCharlie Parker with The Bill Harris/Chubby Jackson HerdB. Harris00:05:111953

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Fine And DandyCharlie Parker with The OrchestraK. Swift00:03:281953

-

2These Foolish ThingsCharlie Parker with The OrchestraJ. Strachey00:03:241953

-

3Light GreenCharlie Parker with The OrchestraBill Potts00:03:371953

-

4Thou SwellCharlie Parker with The Orchestral. Hart00:03:521953

-

5WillisCharlie Parker with The OrchestraBill Potts00:05:251953

-

6Don't Blame MeCharlie Parker with The OrchestraD. Fields00:03:161953

-

7Something To Remember You By / Taking A Chance On Love / Blue RoomCharlie Parker with The OrchestraA. Schwartz00:03:151953

-

8RoundhouseCharlie Parker with The OrchestraGerry Mulligan00:03:141953

-

9Moose The MoocheCharlie Parker QuartetCharlie Parker00:05:091953

-

10I'll Walk AloneCharlie Parker QuartetS. Cahn00:04:511953

-

11OrnithologyCharlie Parker QuartetCharlie Parker00:04:221953

-

12Out Of NowhereCharlie Parker QuartetJ. Green00:04:321953

-

13Groovin' HighCharlie ParkerDizzy Gillespie00:03:481953

-

14Cool BluesCharlie Parker QuartetCharlie Parker00:04:301953

-

15Star EyesCharlie Parker QuartetD. Raye00:05:281953

-

16Moose The Mooche / Lullaby Of BirdlandCharlie Parker QuartetB.Y. Foster00:05:551953

-

17Broadway / Lullaby Of BirdlandCharlie Parker QuartetT. McRae00:03:241953

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1PerdidoCharlie Parker with The Quintet of The YearJuan Tizol00:08:161953

-

2Salt PeanutsCharlie Parker with The Quintet of The YearDizzy Gillespie00:07:361953

-

3All The Things You Are / 52Nd Street ThemeCharlie Parker with The Quintet of The YearJerome Kern00:07:561953

-

4WeeCharlie Parker with The Quintet of The YearD. Best00:06:461953

-

5Hot HouseCharlie Parker with The Quintet of The YearT. Dameron00:09:091953

-

6A Night In TunisiaCharlie Parker with The Quintet of The YearF. Paparelli00:07:391953

-

7The Bluest BluesCharlie Parker with Bud Powell TrioCharlie Parker00:06:411953

-

8On The Sunny Side Of The StreetCharlie Parker with Bud Powell TrioJ. McHugh00:02:561953

-

9Moose The MoocheCharlie Parker with Bud Powell TrioCharlie Parker00:05:151953

-

10Cheryl / Lullaby Of BirdlandCharlie Parker with Bud Powell TrioGeorge Shearing00:08:041953

-

11Dance Of The InfidelsCharlie Parker with Bud Powell TrioBud Powell00:05:281953

CLICK TO DOWNLOAD THE BOOKLET

Parker 12 FA1342

THE COMPLETE Charlie Parker 12

INTÉGRALE Charlie Parker VOL.12

“LAIRD BAIRD”

1952-1953

DIRECTION ALAIN TERCINET

Proposer une véritable «?intégrale?» des enregistrements laissés par Charlie Parker est actuellement impossible et le restera longtemps. Peu de musiciens ont suscité de leur vivant autant de passion. Plus d’un demi-siècle après sa disparition, des inédits sont publiés et d’autres – dûment répertoriés – le seront encore. Bon nombre d’entre eux ne contiennent que les solos de Bird car ils furent enregistrés à des fins privées par des musiciens désireux de disséquer son style. Sur le seul plan du son, ils se situent en majorité à la limite de l’audible voire du supportable. Faut-il rappeler, qu’à l’époque, leurs auteurs employaient des enregistreurs portables sur disque, des magnétophones à fil, à bande (acétate ou papier) et autres machines devenues obsolètes, engendrant des matériaux sonores fragiles??

Aucun solo joué par Charlie Parker n’est certes négligeable, toutefois en réunissant chronologiquement la quasi-intégralité de ce qu’il grava en studio et de ce qui fut diffusé à l’époque sur les ondes, il est possible d’offrir un panorama exhaustif de l’évolution stylistique de l’un des plus grands génies du jazz?; cela dans des conditions d’écoute acceptables.

Toutefois lorsque la nécessité s’en fait sentir stylistiquement parlant, la

présence ponctuelle d’enregistrements privés peut s’avérer indispensable. Au mépris de la qualité sonore.

L’intégrale CHARLIE PARKER

STUDIO & RADIO VOL. 12

“LAIRD BAIRD” 1952-1953

«?Virez moi ce connard du studio ! (1)?» Norman Granz ne s’attendait pas à pareille réception. Selon Max Roach, Bird, d’une humeur exécrable, s’en prenait à tout le monde, même à Hank Jones pour on ne sait quelle raison. En bonne logique, la séance aurait dû tourner au pandémonium. Il n’en fut rien. Après une version magistrale de The Song Is You, la composition de Jerome Kern chère à Stan Getz, seront mises en boîte trois beaux thèmes originaux signés Parker : Laird Baird dédié à son fils nouvellement né, Kim composé en l’honneur de sa belle-fille et Cosmic Rays. À propos de ce dernier morceau, Hank Jones expliqua pourquoi l’interprétation se terminait quelque peu en queue de poisson : «?Il se passait souvent des choses inattendues. Peut-être espérait-on un autre solo, ou encore on pensait mettre le final, tel qu’il avait été préparé, quelques mesures plus tard. Souvent on se retrouvait à la fin du morceau avant de comprendre ce qui nous arrivait et on essayait de s’en tirer de la façon la plus élégante possible. Ce qui n’était pas toujours le cas. De plus il se passait tellement de choses quand Bird jouait qu’on en oubliait parfois les arrangements répétés (2).?»

Le numéro de Down Beat daté du 28 janvier 1953 contenait une interview de Charlie Parker conduite par Nat Hentoff. Après y avoir défendu son orchestre à cordes et parlé de musique classique, Bird évoquait ses admirations dans le domaine du jazz. «?Aussi longtemps que je vivrai, j’apprécierai l’œuvre de Thelonious Monk. Et Bud Powell qui joue vraiment. À propos de Lennie Tristano, je tiens à ce que soit mentionné sur la bande le fait que j’approuve l’intégralité de son travail, dans toute sa spécificité […] Et j’aime Brubeck. C’est un perfectioniste, ce que j’essaye d’être. Et je suis très touché par son saxophoniste alto, Paul Desmond.?» Pas un mot sur Miles Davis qu’il allait retrouver en studio deux jours plus tard.

Aux prises à une sujétion aux stupéfiants, Miles était au creux de la vague. Depuis plus d’un an il n’avait rien enregistré pour son label attitré, Prestige, gravant seulement six titres publiés par Blue Note. Une séance qui réunirait, sous sa houlette, Bird et Sonny Rollins, tous deux au saxophone ténor, devait à ses yeux marquer son retour. Elle ne se déroula pas vraiment comme il l’aurait espéré.

Déjà absent de la répétition qu’il avait réclamée une semaine plus tôt, Parker était arrivé en retard à son habitude. De fort méchante humeur de surcroît, il asticotait Miles en tuant le temps à grand renfort de bières avant de s’endormir après avoir bu pratiquement cul sec, trois quarts de litre de gin. Malgré tout, essayant toujours de dissuader quiconque de l’imiter, il avait eu le temps de sermonner Sonny Rollins assujetti lui aussi aux drogues dures.

Après que Miles eut échangé selon l’usage quelques amabilités avec Ira Gitler, le producteur, les musiciens attaquèrent. Contrairement à toute logique, le résultat de la séance fut mieux que satisfaisant. Premier soliste dans Compulsion, second sur Serpent’s Tooth – deux compositions originales d’une construction intéressante signées Miles Davis -, Parker n’est pourtant pas vraiment à l’aise avec un saxophone ténor. ‘Round Midnight fut choisi pour remplacer Well You Needn’t impossible à mettre au point. Face à un thème qu’il n’avait encore jamais gravé, Miles reste dans l’expectative. Parker joue abondamment ce qui, malgré tout, n’arrive pas à effacer une impression de brouillon. Cela malgré l’excellence d’une rythmique réunissant Walter Bishop, Percy Heath et Philly Joe Jones.

La chaîne de télévision CBFT-TV, branche de la Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, diffusait en direct le jeudi soir une émission d’une demi-heure, «?Jazz Workshop?». Parker en fut l’invité le 5 février avec, à ses côtés, Brew Moore au ténor et Dick Garcia à la guitare. Parmi les trois musiciens canadiens formant la rythmique, un jeune pianiste commençait à faire parler de lui, Paul Bley qui, plus tard, avouera avoir été frappé par la faculté d’anticipation de Bird durant un chorus. Furent interprétés Cool Blues, Don’t Blame Me, Bernie’s Tune dévolu entièrement à Brew Moore et Wahoo réunissant tout le monde. Deux jours plus tard, au cours d’un concert organisé l’après-midi au club Chez Paree, Bird rencontra une figure légendaire du jazz local, le pianiste Steep Wade qui avait été le mentor d’Oscar Peterson. Bopper convaincu au jeu inspiré par Bud Powell, il devait disparaître à la fin de cette même année 1953.

Arguant le fait que sa fille Pree, âgée d’un an et demi, était hospitalisée, Charlie Parker avait adressé à la State Liquor Authority une demande pour que lui soit rendue sa «?New York City Cabaret Identification Card?» : un engagement d’une semaine l’attendait au Bandbox, un nouveau club jouxtant le Birdland. De ce passage, il ne reste qu’une retransmission radiophonique donnant à entendre Bird déboulant au milieu de Your Father’s Moustache interprété par la formation de Bill Harris - Chubby Jackson.

Le 22 février, au Club Kavakos de Washington, était programmé en fin d’après-midi, un concert pour lequel Bird serait accompagné par The Orchestra. Dave Amram : «?À cette époque, je me suis joint quelques fois à un ensemble formidable dirigé par le regretté Joe Theimer, The Orchestra. Une des meilleures grandes formations que j’ai jamais entendu de toute ma vie. Chacun de ses membres était tout à la fois un excellent soliste et un musicien de section accompli (3).?» Marky Markowitz à la trompette, Earl Swope au trombone et le saxophoniste baryton Jack Nimitz en faisaient alors partie.

Thou Swell, arrangé par Johnny Mandel, Willis, un hommage à Lester Young signé Bill Potts, These Foolish Things revu par Joe Theimer donnent à entendre un Parker heureux, s’amusant à citer Petrouchka de Stravinsky au cours de Fine and Dandy. Malgré cela, le manque de répétition se fit parfois sentir. Après l’interlude orchestral du Roundhouse, la tonalité passe du sol au mi bémol ce qu’ignore Bird, de même l’arrivée de Taking a Chance on Love au cours du «?medley?» prend Parker au dépourvu. Il ne reprendra la parole qu’à l’arrivée du troisième thème, Blue Room. Malgré ces aléas, un tel concert montrait que, sur le plan de l’association Parker / grande formation, il existait d’autres solutions que celle choisie par Norman Granz.

Patron du Storyville, George Wein, pianiste et chanteur, pourtant guère porté sur le jazz moderne, écrira : «?Bird vint à Boston en tant que soliste. Nous avons réuni une section

rythmique comprenant Bernie Griggs à la basse, William “Red” Garland au piano et, à la batterie, Roy Haynes qui, naturellement, avait déjà joué avec Bird?; les autres se joignaient à lui pour la première fois. J’ai écouté nombre de leurs sets au long de leur engagement, et petit à petit, le message musical de Bird m’a touché. Les innombrables imitateurs que j’avais entendu à Boston et à New York n’arrivaient pas à reproduire une once de sa puissance et de sa virtuosité. Son interprétation des ballades était révélatrice. Bird pouvait improviser sur la mélodie, pas seulement sur les changements d’accords et c’est ce qui m’a convaincu. Il ne se contentait jamais de jouer seulement des notes (4).?»

La matinée du dimanche 8 mars fut retransmise sur la chaîne de radio WHDH, seule occasion d’entendre Charlie Parker en compagnie de l’un des futurs pianistes favoris de Miles Davis, Red Garland. Au programme une chanson popularisée par Dinah Shore que Parker ne grava jamais en studio, I’ll Walk Alone. «?La première apparition notoire de Bird à Boston fut un succès. Je me suis assuré que Charlie reviendrait au club en septembre à sa réouverture (5).?» Il le fera et passera à nouveau sur les ondes.

De retour à New York, Parker revint au Bandbox à l’occasion d’un concert organisé par Down Beat pour honorer les vainqueurs de son référendum 1952. Il y interprétera Groovin’ High accompagné par le trio de Milt Buckner. Une semaine plus tard, cette fois à la tête de son propre quartette, Bird est à nouveau la vedette d’une retransmission depuis le Bandbox. S’y fait entendre un Parker visiblement fatigué, au jeu souvent brouillon. Une exception car, au Birdland où il retrouvait John Lewis, Kenny Clarke et Candido sur Cool Blues, Star Eyes et Moose the Mooche, il est redevenu lui-même. Pour remplacer Jumpin’ with Symphony Sid dont le dédicataire s’est éloigné de New York, le cabaret utilise maintenant comme indicatif, Lullaby of Birdland composé par George Shearing.

Certains membres de la Toronto New Jazz Society avaient suggéré de réunir au printemps 1953 les pères-fondateurs du jazz moderne pour un seul et unique concert. Un projet qui fut loin de soulever l’enthousiasme : le déficit laissé par la venue, l’été précédent, du quintette de Lennie Tristano restait dans toutes les mémoires. Petit à petit l’idée fit pourtant son chemin et l’unanimité se fit sur les noms de Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Lennie Tristano, Oscar Pettiford et Max Roach. Tristano fit remarquer que Bud Powell serait plus à sa place que lui. Pettiford prétendit qu’il n’était pas libre et, en conséquence, après s’être fait tirer l’oreille, Mingus accepta. L’instabilité de Bud Powell, tout juste sorti du Bellevue Hospital, était connue et, trois mois plus tôt, Bird lui-même avait causé quelque scandale à Montréal. Néanmoins, il semble bien que seul ce dernier ait manifesté un quelconque enthousiasme à la perspective de cette réunion à haut risque.

À l’aéroport, il apparut que le nombre de billets d’avion retenus par les organisateurs n’était pas suffisant : Mingus emmenait son épouse et Oscar Goodstein, le propriétaite du Birdland, devait servir de chaperon à Bud Powell. Bird et Diz prirent donc le vol suivant et, arrivé à Toronto, Parker s’empressa de semer Gillespie.

Selon les réglements syndicaux en vigueur, un nombre égal de musiciens canadiens devait partager la scène du Massey Hall avec les invités. Pour faire bonne mesure, le CBC Orchestra (dix-sept membres) dirigé par le trompettiste Graham Topping, fut engagé pour assurer la première partie. Jugée superflue, aucune publicité n’avait été faite dans la presse écrite et comme l’heure du concert coïncidait avec la retransmission télévisée du match de boxe opposant pour le titre mondial, Rocky Marciano à Jersey Joe Walcott, à peine un tiers de la salle était occupé…

Le CBC Orchestra ouvrit les hostilités avec The Goof and I suivi d’une dizaine de morceaux puis «?The Quintet of the Year?» pénétra sur scène. En premier Gillespie, escorté de Mingus et de Max Roach puis Bud Powell, conduit à son piano par Oscar Goldstein et, enfin, miraculeusement réapparu, Bird avec, à la main, un alto Grafton en plastique blanc emprunté. Il était venu sans instrument.

Aucun répertoire n’ayant été défini à l’avance, après discussion Perdido réunit les suffrages. L’occasion pour Bird de prendre en main son étrange alto, encouragé par les exclamations d’un Gillespie qui avait pu constater depuis les coulisses que son favori, Jersey Joe Walcott, n’avait pas fait le poids (6).

Suivit Salt Peanuts que Parker présenta ironiquement, parodiant les déclarations de Dizzy pour qui il aurait été «?la moitié de son cœur » : «?Maintenant nous aimerions interpréter un thème composé en 1942 par celui qui représente la partie la plus respectable de moi-même, Mr. Dizzy Gillespie. Nous espérons sincèrement que vous prendrez plaisir à… Salt Peanuts.?» Une annonce qui irrita suffisamment Dizzy pour l’inciter à lancer une salve de «?Salt Peanuts?» hurlés pendant le solo de Bird. Un All the Things You Are de haute volée précéda la partie assurée par Bud Powell en trio.

À la reprise, Wee prouva que la maîtrise de Bird restait intacte alors que, durant l’entracte, il avait étanché sa soif à coups de triples whiskies au bar du King Edward Hotel tout proche. Hot House,

A Night in Tunisia annoncé par Dizzy comme «?Ce soir en Tunis?» puis le concert se termina avec une jam session sur Tiny’s Blues réunissant toute la troupe - moins Bud Powell - à l’orchestre de Graham Topping. Le “Quintet of the Year” avait fait beaucoup mieux que remplir son contrat.

Don Brown assistait au concert : «?Des rumeurs se firent jour à propos de disputes survenues dans les coulisses - entre Bird et Diz, entre Bird et les organisateurs, entre Mingus et tout le monde. Je ne sais pas si c’est vrai. Sur scène, leur amicale rivalité musicale déboucha sur un véritable feu d’artifice. Le génie avait prévalu sur l’anarchie et le chaos (7).?»

À la fin de la soirée, Mingus qui n’avait cessé de récriminer contre tout et tous, confisqua à les bandes du concert enregistré sans l’accord des intéressés. Lorsqu’un membre de la New Jazz Society, Roger Feather, émit une timide objection, il s’attira cette charmante réponse : «?Elles sont à moi, petit blanc?». S’estimant mal mis en valeur par la prise de son, dans un premier temps il déclara vouloir les détruire puis, se ravisant, enregistra en re-recording une nouvelle partie de basse sans pouvoir effacer l’ancienne. Pour une somme astronomique, il proposa les bandes à Norman Granz qui refusa. Le concert de Toronto fut donc publié sur le label de Mingus, Debut. Pour des raisons contractuelles, Parker s’y dissimulait derrière le pseudonyme de «?Charlie Chan?». On se demande bien qui s’y laissa prendre…

À l’occasion des retransmissions radiophoniques dont le Birdland s‘était fait une spécialité, Bird se joignit à deux reprises aux formations figurant à l’affiche. En premier, au quintette de Gillespie, celui-là même avec lequel Dizzy s’était produit en France en début d’année. Un ensemble qui, malgré le talent du pianiste Wade Legge trop tôt disparu, ne comptait pas au nombre de ses meilleurs. Sur The Bluest Blues était également présent Miles Davis. Une réunion au sommet à la vérité décevante, Dizzy et Joe Carroll s’amusent beaucoup, Bird un peu, Miles beaucoup moins. D’ailleurs une certaine confusion régnait, à tel point que, après le solo de Wade Legge sur On the Sunny Side of the Street, on entend Joe Carroll appeler «?Charles, Charles?» pour signifier à Parker qu’était arrivé son tour de jouer.

Une semaine plus tard, toujours au Birdland, Bird se joignit au trio de Bud Powell. Autre invité, Candido Camero dont la conga posait toujours un problème à l’ingénieur du son. Ce qui n’interdit pas d’apprécier ses échanges sur Moose the Mooche et Cheryl avec Art Taylor puis avec Parker qui multiplie les citations, de My Kind of Love à West End Blues. N’entendant pas céder un pouce de terrain, Bud Powell atteint des sommets, tout spécialement au long de Dance of the Infidels où Max Roach tient la batterie. Une rivalité qui, à cette date, débouchait encore sur le meilleur. Il en sera tout autrement moins d’un an plus tard.

Alain Tercinet

© 2016 Frémeaux & Associés

(1) Livret du coffret «?The Complete Charlie Parker on Verve?».

(2) Jazz Magazine, juin 1994.

(3) David Amram, «?Vibrations?», Paradigm Publishers, Boulder, London, 2010.

(4) (5) George Wein with Nate Chinen, «?Myself Among Others – A Life in Music?», Da Capo Press, 2003.

(6) Rocky Marciano avait expédié Joe Walcott au tapis après 2’25’’ de combat. Ce qui indisposa beaucoup Gillespie…

(7) Don Brown, «?Jazz at Massey Hall : Eyewitness?», JazzWax, 28 janvier 2009, internet.

NOTES DISCOGRAPHIQUES

CHARLIE PARKER QUARTET (30/12/1952)

Laird Baird était titré à l’origine Blues for Baird.

JAZZ WORKSHOP ALL STARS

Bien que Parker soit absent sur Bernie’s Tune, ce morceau figure ici de façon à conserver l’intégralité du programme télévisé. En 1993, le label Uptown publia une reconstitution du concert donné Chez Paree. Aux deux titres connus, venaient s’ajouter Cool Blues, I’ll Remember April, Moose the Mooche et Now’s the Time.

THE BANDBOX

Malgré sa piètre qualité sonore, Your Father’s Moustache a été inclus pour son pittoresque. Par contre l’impasse a été faite sur la retransmission radiophonique du 30 mars 1953. D’une qualité sonore au dessous de la moyenne, elle présente en sus un Parker en petite forme.

CHARLIE PARKER with THE ORCHESTRA

Un certain nombre d’éditions comporte une

version tronquée de Don’t Blame Me.

CHARLIE PARKER QUARTET

La séance réunissant au Birdland Charlie Parker et John Lewis, Curley Russell, Kenny Clarke est datée du 9 mai 1953. Cependant ces derniers s’y produisant à partir du 18 juin, on peut s’interroger sur l’exactitude de cette datation.

DIZZY GILLESPIE QUINTET

with CHARLIE PARKER

De nombreuses discographies donnent Sahib Shihab au saxophone baryton. Il s’agit en fait de Bill Graham, alors membre permanent du quintette de Gillespie.

THE COMPLETE CHARLIE PARKER

STUDIO & RADIO VOLUME 12

“LAIRD BAIRD” 1952-1953

A genuine “complete” set of the recordings left by Charlie Parker is impossible today and will remain so for a long time to come. Few musicians aroused so much passion during their own lifetimes and today, more than half a century after his disappearance, previously-unreleased music is published, and other titles – duly listed – will also come to light. A good many contain only solos by Bird, as they were recorded – privately – by musicians wanting to dissect his style. Regarding their sound-quality, most of them are at the limit: barely audible, sometimes almost intolerable, but in fact understandable: those who captured these sounds used portable recorders that wrote direct-to-disc, or wire-recorders, “tapes” (acetate or paper) and other machines now obsolete. Obviously they all produced sound-carriers that were fragile.

Of course, no solo ever played by Charlie Parker is to be disregarded. But a chronological compilation of almost everything he recorded – either inside a studio or on radio for broadcast purposes – does make it possible to provide an exhaustive panorama of the evolution of his style (Parker was, after all, one of the greatest geniuses in jazz), and to do so under acceptable listening-conditions. However, since we refer to style, the occasional presence here of some private recordings is indispensable, whatever the quality of the sound.

“Get the fuck out the studio!” (1) It wasn’t the reception Norman Granz expected. According to Max Roach, Bird was in a foul mood and gunning for everybody, even Hank Jones for some reason. Normally this would have meant pandemonium in the studio, but nothing came of it. After a masterly take of The Song Is You, the Jerome Kern composition that Stan Getz liked so much, they recorded three beautiful originals by Parker: Laird Baird, dedicated to his newborn son; then Kim, written in honour of his daughter-in-law, and Cosmic Rays. Regarding this last one, Hank Jones had an explanation for the abrupt ending to the performance: ”The unexpected often happened. Maybe we were hoping for another solo, or else we were thinking about the conclusion the way we’d planned it for a few bars later. We’d often find ourselves at the end of a piece before we realized what was happening, and then try to pull it off the most elegant way we could. Which wasn’t always the case. There would be

so much going on when Bird was playing that sometimes we forgot which arrangements we’d rehearsed.” (2)

The Down Beat issue dated January 28, 1953 had an interview with Bird by Nat Hentoff, and Parker, after defending his string ensemble and mentioning classical music, had this to say about his jazz tastes: “As long as I live, I’ll appreciate the accomplishments of Thelonious Monk. And Bud Powell plays so much. As for Lennie Tristano, I’d like to go on record as saying I endorse his work in every particular […] And I like Brubeck. He’s a perfectionist, as I try to be. And I’m very moved by his altoist Paul Desmond.” Not a word about Miles Davis. He was due to go into the studio with him only two days later.

Struggling with a drug habit, Miles had almost reached bottom. In more than a year he recorded nothing at all for his nominal label Prestige, but he did cut six titles (released by Blue Note). Miles thought that a session on which he was the leader, with Bird and Sonny Rollins, would be the one to mark his comeback. It didn’t go off as hoped. A week earlier, Parker had already missed the rehearsal he’d been calling for, and now he turned up late, as was his habit. On top of this, he was in a bad mood, and he began needling Miles while drinking a lot of beer. Then he started on the gin, and after downing three-quarters of a litre he fell asleep. But not before he’d had the time, while still trying to dissuade everyone from copying him, to give Sonny Rollins (another addict) a sermon on the dangers of hard drugs.

After Miles had insulted producer Ira Gitler, the musicians got down to business. Against all logic, the result of the session was more than satisfying. Soloing first on Compulsion, and second on

Serpent’s Tooth — both Miles Davis compositions with interesting structures —, Parker wasn’t really feeling comfortable with a tenor saxophone. ‘Round Midnight was chosen to replace an attempted Well You Needn’t that turned out to be impossible to get right. Opposite a theme he hadn’t yet had occasion to record, you can hear that Miles remains expectant. Parker plays profusely, but still doesn’t manage to avoid giving a muddled impression despite the excellent rhythm section (Walter Bishop, Percy Heath and Philly Joe Jones.)

Television channel CBFT-TV, part of the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, used to put out a thirty-minute “Jazz Workshop” programme every Thursday evening, and on February 5th Parker was its guest, along with tenor Brew Moore and Dick Garcia on guitar. The rhythm section was comprised of Canadian musicians, and the pianist was a young man who was starting to attract attention, namely Paul Bley. He later confessed he was impressed by how easily Bird seemed to anticipate things while playing a chorus. They played Cool Blues, Don’t Blame Me, Bernie’s Tune (a vehicle for Brew Moore), and then Wahoo on which everyone joined in. Two days later, at an afternoon concert organized at the “Chez Paree” club, Bird met a legendary local jazz figure, pianist Steep Wade, who’d been Oscar Peterson’s mentor. Wade was a convinced bopper whose playing was inspired by Bud Powell; he was destined to pass away at the end of that same year, 1953.

Arguing that his daughter Pree (aged eighteen months) had been admitted to hospital, Charlie Parker addressed a request to the State Liquor Authority for his “New York City Cabaret Identification Card” to be returned to him: a week-long booking was waiting for him at the Bandbox, a new club next-door to Birdland. Only a radio broadcast remains of his appearance there, and on it you can hear Bird jumping into the middle of Your Father’s Moustache in a set from the band led by Bill Harris and Chubby Jackson. On February 22nd at the Kavakos in Washington, the afternoon set was billed as a concert with Bird “accompanied by The Orchestra.” According to Dave Amram, “I sat in a few times with The Orchestra, a great band headed by the late Joe Theimer, one of the best big bands I ever heard in my life. Every member was an excellent soloist as well as a fine section man.” (3) At the time they included Marky Markowitz on trumpet, Earl Swope on trombone plus baritone saxophonist Jack Nimitz. Thou Swell, arranged by Johnny Mandel, together with Willis, a Lester Young tribute composed by Bill Potts, and These Foolish Things revisited by Joe Theimer, allow you to hear a happy Parker having fun, and he plays quotes from Stravinsky’s Petrushka in the course of Fine and Dandy. Despite this, at times you can feel a certain lack of rehearsal: after the orchestral interlude of Roundhouse, the key changes from G to E flat, which Bird totally ignores, and the arrival of Taking a Chance on Love during the medley takes Parker completely by surprise. He only gets back on the rails when the third tune arrives, Blue Room. Despite those episodes, a concert like this one shows that when it came to pairing Bird with a big band, there were other solutions to be had than those chosen by Norman Granz.

Storyville’s owner George Wein was a singer/pianist with little affection for modern jazz, yet he was moved to write, “Bird came to Storyville as a solo. We put together a rhythm section consisting of Bernie Griggs on bass, William ‘Red’ Garland on piano, and Roy Haynes on drums, who of course had worked with Bird before; the others were playing with him for the first time. I heard most of their sets during the engagement, and gradually Bird’s musical message reached me. The countless copycats I had heard in Boston and New York didn’t begin to capture his strength and brilliance. His ballad playing was especially revealing. Bird would improvise on the melody and not just the chord changes, which is what won me over. He was never just blowing notes.”(4) The matinee concert on Sunday March 4 was broadcast by radio WHDH ; it’s the only time you can hear Parker in the company of one of Miles Davis’ future favourites on piano, Red Garland. The programme contains a song made popular by Dinah Shore that Parker never recorded in the studios, I’ll Walk Alone. “Bird’s first notable appearance in Boston was a success. I made sure to invite Charlie back to the club for our reopening in September.” (5) He did, and it was aired again.

Back in New York, Parker returned to the Bandbox for a concert that Down Beat had organized to honour winners of its 1952 Poll. Bird played Groovin’ High accompanied by Milt Buckner and his trio. A week later, this time fronting his own quartet, Bird once again starred in a Bandbox broadcast; he was visibly tired, and his playing was often untidy, but it was an exception, because at Birdland, where he met up with John Lewis, Kenny Clarke and Candido again for Cool Blues, Star Eyes and Moose the Mooche, he was back to his normal self. Birdland, incidentally, was now using George Shearing’s Lullaby of Birdland as its theme-tune instead of Jumpin’ with Symphony Sid (because the man to whom it was dedicated had left New York.)

Certain members of the Toronto New Jazz Society had suggested a reunion of the founding fathers of modern jazz in the spring of 1953 for a one-off concert. It was a proposal that raised little enthusiasm: everyone remembered the deficit that had been left the previous summer after the visit of Lennie Tristano and his quintet. The idea slowly took hold however, and they reached unanimity on a list of five names: Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Lennie Tristano, Oscar Pettiford and Max Roach. Tristano pointed out that Bud Powell would be more suitable than himself, given the company, while Pettiford pretended he wasn’t available; Mingus was therefore solicited and, after a lot of persuading, he accepted. Bud Powell’s instability was no secret — he was just out of Bellevue Hospital, in fact — and three months earlier, Bird himself had created something of a scandal in Montreal. It seemed that Parker was the only one with any enthusiasm for the whole thing so the reunion was going to be a risk…

At the airport, already, the number of tickets provided by the organizers appeared to be insufficient: Mingus was taking his spouse, and Oscar Goodstein, who owned Birdland, was chaperoning Bud Powell… and so Bird & Diz took the next flight. When they arrived in Toronto, Bird pulled a fast one on Gillespie and disappeared.

There were Union Rules that applied, too: an equal number of Canadian musicians had to share the stage at Massey Hall with the invited Americans. To give good measure, the CBC Orchestra (seventeen strong), led by the trumpeter Graham Topping, was hired to play the first half. Advertising had been deemed superfluous, so there was nothing in the local press to draw attention away from another matter: Rocky Marciano was fighting Jersey Joe Walcott for the world heavyweight title, and the concert coincided with television’s coverage of the boxing. Barely a third of the seats at Massey Hall were occupied.

The CBC Orchestra opened hostilities with The Goof and I, followed by ten other titles, before “The Quintet of the Year” finally trooped onstage. Gillespie came on first, escorted by Mingus and Max Roach; then came Bud Powell, led to his piano by Oscar Goldstein; and finally, in a miraculous reappearance, on came Bird, carrying a white plastic alto saxophone made by Grafton. He had borrowed the instrument because he’d gone to Toronto without his own horn.

There was no setlist (none of the repertoire had been decided beforehand), and after some discussion they settled for Perdido. It was a chance for Bird to flex his muscles with his strange alto, encouraged by the exclamations of Gillespie, who’d learned in the wings that his favourite, Jersey Joe Walcott, hadn’t lasted long.(6)

Salt Peanuts followed, introduced with some irony by Parker; he parodied Dizzy’s earlier declarations — Parker was apparently “half of his heart” — by saying, “At this time we would like to play a tune that was composed by my worthy constituent Mr. Dizzy Gillespie in the year of 1942. We sincerely hope that you do enjoy… Salt Peanuts.” Dizzy found the announcement irritating enough to be moved to fire loud salvoes of “Salt Peanuts” during Bird’s solo. A high-flying version of All the Things You Are then preceded the part of the concert devoted to Bud Powell in trio.

When they came back on after the interval, Wee proved that Bird’s mastery was still intact, even though he’d spent most of the intermission downing triple whiskies at the bar next-door in the King Edward Hotel. They played Hot House, A Night in Tunisia (announced by Dizzy as “Ce soir en Tunis”), and then the concert ended with a jam on Tiny’s Blues where everyone joined in, including Graham Topping and his orchestra — except for Bud Powell, that is. “The Quintet of the Year” had more than fulfilled its contract.

Don Brown was there: “Rumors later emerged about the fighting that took place backstage — between Bird and Diz, between Bird and the promoters, between Mingus and everybody. I have no idea whether or not that was the case. On stage, the friendly musical rivalry sparked a melodic firestorm. Out of anarchy and chaos, musical genius prevailed.” (7) At the end, Mingus, who hadn’t stopped bitterly complaining about everyone and anything all night, confiscated the tapes recorded at the concert because no one had given his consent. Roger Feather, a member of the New Jazz Society, raised timid objections but Mingus turned on the charm: “They’re mine, white boy.” The bassist thought the sound didn’t do him justice. At first he declared he was going to destroy the tapes, and then changed his mind; he overdubbed a new bass part without being able to erase the original. He offered the tapes — for an astronomical figure — to Granz, who refused. So the Toronto concert was released by Mingus’ own label, Debut. For contractual reasons Parker hid behind the pseudonym “Charlie Chan”. It makes you wonder who might have been taken in by that…

The radio broadcasts that Birdland had turned into something of a speciality twice gave the Bird an occasion to join in with other ensembles that were featured. First, there was Gillespie’s quintet, the same one that Dizzy had taken to France at the beginning of that year; despite the talent of its pianist, Wade Legge, who died all too prematurely, this band wasn’t one of Dizzy’s best. For The Bluest Blues, Miles Davis was also present; and for a so-called summit meeting it turned out to be rather disappointing: Dizzy and Joe Carroll had a lot of fun, but Bird only a little, and Miles even less. A certain confusion reigned, too, so much so that after Wade Legge’s solo in On the Sunny Side of the Street, Joe Carroll can be heard calling, “Charles, Charles,” to draw Parker’s attention to the fact that it was his turn to play.

A week later, back at Birdland again, Parker joined Bud Powell and his trio. Another guest was Candido Camero, whose conga always gave the sound engineer problems, but that doesn’t stop you appreciating his exchanges with Art Taylor (on Moose the Mooche and Cheryl), and then with Bird, who plays quote after quote from pieces that range from My Kind of Love to West End Blues. Bud Powell had no intention of yielding an inch, and here he reaches the summits, particularly all the way through Dance of the Infidels, which has Max Roach on drums. Rivalry had by now reached the point where it led only to the best. But it would be quite a different matter less than a year later.

Alain Tercinet

Adapted by Martin Davis

from the French Text of Alain Tercinet

© 2016 Frémeaux & Associés

(1) From the booklet accompanying the box-set, “The Complete Charlie Parker on Verve”.

(2) Jazz Magazine, June 1994.

(3) David Amram, “Vibrations”, Paradigm Publishers, Boulder, London, 2010.

(4) (5) George Wein with Nate Chinen, “Myself Among Others – A Life in Music”, Da Capo Press, 2003.

(6) Rocky Marciano decked Joe Walcott after only 2’25’’. Dizzy was very upset.

(7) Don Brown, “Jazz at Massey Hall : Eyewitness”, JazzWax, January 28th 2009, internet.

DISCOGRAPHICAL NOTES

CHARLIE PARKER QUARTET (30/12/1952)

Laird Baird originally had the title Blues for Baird.

JAZZ WORKSHOP ALL STARS

Although Parker is absent on Bernie’s Tune, this piece appears here in order to preserve the entire programme that was televised. In 1993 the Uptown label published a reconstitution of the concert that was given at the Chez Paree. The two titles already known were complemented by Cool Blues, I’ll Remember April, Moose the Mooche and Now’s the Time.

THE BANDBOX

Despite its sorry sound quality, Your Father’s Moustache has been included for its colourfulness. On the other hand, we chose to overlook the radio broadcast dated March 30th, 1953. Its sound is below average, but in addition, Parker wasn’t in very good shape.

CHARLIE PARKER with THE ORCHESTRA

Certain releases contain a truncated version of Don’t Blame Me.

CHARLIE PARKER QUARTET

The date of the session at Birdland that brought Charlie Parker, John Lewis, Curley Russell and Kenny Clarke together is given as May 9th, 1953; however, the fact that the latter played there starting on June 18th allows for some doubt as to the exactitude of that first date.

DIZZY GILLESPIE QUINTET

with CHARLIE PARKER

Numerous discographies give Sahib Shihab as the baritone saxophonist; the musician is actually Bill Graham, who was then a permanent member of the Gillespie quintet.

discographie - CD 1

CHARLIE PARKER QUARTET

Charlie Parker (as)?; Hank Jones (p)?; Teddy Kotick (b)?; Max Roach (dm). NYC, 30/12/1952

?1. THE SONG IS YOU (J. Kern, O. Hammerstein II) (Clef 89144/mx. 1118-3) 2’59

?2. LAIRD BAIRD (C. Parker) (Clef 89144/mx. 1119-7) 2’46

?3. KIM (C. Parker) (Verve MGV8005/mx. 1120-2) 2’59

?4. KIM (C. Parker) (master) (Clef 89129/mx. 1120-4) 2’59

?5. COSMIC RAYS (C. Parker) (master) (Clef 89129/mx. 1121-2) 3’05

?6. COSMIC RAYS (C. Parker) (Verve MGV8005/mx. 1121-5) 3’17

MILES DAVIS SEXTET

Miles Davis (tp)?; Charlie Chan (Charlie Parker), Sonny Rollins (ts)?; Walter Bishop (p)?; Percy Heath (b)?; Philly Joe Jones (dm). NYC, 30/1/1953

?7. COMPULSION (M. Davis) (Prestige PRLP 7044/mx. 450) 5’44

?8. SERPENT’S TOOTH (M. Davis) (Prestige PRLP 7044/mx. 451-1) 7’00

?9. SERPENT’S TOOTH (M. Davis) (Prestige PRLP 7044/mx. 451-2) 6’17

10. ‘ROUND MIDNIGHT (T. Monk, C. Williams, B. Hanighan) (Prestige PRLP 7044/mx. 452) 7’05

JAZZ WORKSHOP ALL STARS

Charlie Parker (as, except Bernie’s Tune)?; Brew Moore (ts)*?; Paul Bley (p)?; Dick Garcia (g)?; Neil Michaud (b)?; Ted Paskert (dm)?; Don Cameron (mc). CBC studio TV, Montréal, 5/2/1953

11. Intro / COOL BLUES (C. Parker) (TV Transcription) 2’26

12. BERNIE’S TUNE* (B. Miller) (TV Transcription) 3’19

13. DON’T BLAME ME (J. McHugh, D. Fields) (TV Transcription) 3’29

14. WAHOO*(B. Harris) / Closing (TV Transcription) 3’54

JAZZ WORKSHOP ALL STARS

Charlie Parker (as)?; Waldo Williams (p)?; Dick Garcia (g)?; Hal Gaylor (b)?; Billy Graham (dm).

Chez Paree, Montréal, 7/2/1953

15. ORNITHOLOGY(C. Parker, B. Harris) (Private Recording) 4’40

Charlie Parker (as)?; Harold «?Steep?»Wade (p)?; Dick Garcia (g)?; Bob Rudd (b)?; Bob Malloy (dm). Same date & place

16. EMBRACEABLE YOU (G. & I. Gershwin) (Private Recording) 3’43

CHARLIE PARKER with THE BILL HARRIS / CHUBBY JACKSON HERD

(Bill Harris (tb)?; Charlie Parker, Charlie Mariano (as)?; Harry Johnson (ts)?; Sonny Truitt (p)?; Chubby Jackson (b)?; Morey Feld (dm)?; band (voc)?; Bob Garrity (mc). Radio Broadcast, Bandbox, NYC, 16/2/1953

17. YOUR FATHER’S MOUSTACHE (B. Harris, W. Herman) (Radio Transcription) 5’11

Les étoiles * relient la présence ponctuelle d’un musicien ou d’un orchestre dans un ou plusieurs morceaux d’une séance

discographie - CD 2

CHARLIE PARKER with THE ORCHESTRA

Charlie Parker (as) with Ed Leddy, Marky Markowitz, Charlie Walp, Bob Carey (tp)?; Earl Swope, Rob Swope, Don Spiker (tb)?; Jim Riley (as)?; Angelo Tompros, Jim Parker, Ben Lary (ts)?; Jack Nimitz (bs)?; Jack Halliday (p, arr)?; Mert Oliver (b)?; Joe Timer (dm, arr)?; Bill Potts, Gerry Mulligan, Al Cohn, Johnny Mandel (arr). Club Kavakos, Washington DC, 22/2/1953

?1. FINE AND DANDY (K. Swift, P. James) (Private Recording) 3’26

?2. THESE FOOLISH THINGS (J. Strachey, H. Marvell) (Private Recording) 3’22

?3. LIGHT GREEN (B. Potts) (Private Recording) 3’35

?4. THOU SWELL (R. Rodgers, L. Hart) (Private Recording) 3’50

?5. WILLIS (B. Potts) (Private Recording) 5’23

?6. DON’T BLAME ME (J. McHugh, D. Fields) (Private Recording) 3’14

?7. SOMETHING TO REMEMBER YOU BY( A. Schwartz, H. Dietz)/ TAKING A CHANCE ON LOVE (T. Fetter, V. Duke)/ BLUE ROOM (R. Rodgers, L. Hart) (Private Recording) 3’13

?8. ROUNDHOUSE (G. Mulligan) (Private Recording) 3’11

CHARLIE PARKER QUARTET

Charlie Parker (as)?; Red Garland (p)?; Bernie Griggs (b)?; Roy Haynes (dm)?; John McLellan (mc).

Radio Broadcast, Storyville Club, Boston, 10/3/1953

?9. MOOSE THE MOOCHE (C. Parker) (Radio Transcription) 5’07

10. I’LL WALK ALONE (J. Styne, S. Cahn) (Radio Transcription) 4’49

11. ORNITHOLOGY (C. Parker, B. Harris) (Radio Transcription) 4’20

12. OUT OF NOWHERE (J. Green, E. Heyman) (Radio Transcription) 4’29

CHARLIE PARKER

Charlie Parker (as)?; Milt Buckner (org)?; Bernie McKay (g)?; Cornelius Thomas (dm)?; Leonard Feather (mc).

Down Beat Poll Winners, Radio Broadcast, Bandbox, NYC, 23/3/1953

13. GROOVIN’ HIGH (D. Gillespie) (Radio Transcription) 3’45

CHARLIE PARKER QUARTET

Charlie Parker (as)?; John Lewis (p)?; Curley Russell (b)?; Kenny Clarke (dm)?; Candido (cga)*?; Bob Garrity (mc).

Radio Broadcast, Birdland, NYC, 9/5/1953 or late june 1953

14. COOL BLUES (C. Parker) (Radio Transcription) 4’30

15. STAR EYES (G. DePaul, D. Raye) (Radio Transcription) 5’28

16. MOOSE THE MOOCHE / LULLABY OF BIRDLAND (C. Parker/G. Shearing, B. Y. Foster)

(Radio Transcription) 5’55

17. BROADWAY* / LULLABY OF BIRDLAND* (H. Woods, T. McRae, B. Bird/ G. Shearing, B. Y. Foster)

(Radio Transcription) 3’24

Les étoiles * relient la présence ponctuelle d’un musicien ou d’un orchestre dans un ou plusieurs morceaux d’une séance

discographie - CD 3

THE QUINTET OF THE YEAR

Dizzy Gillespie (tp)?; Charlie Chan (Charlie Parker) (as)?; Bud Powell (p)?; Charles Mingus (b)?; Max Roach (dm).

Massey Hall, Toronto, 15/5/1953

?1. PERDIDO (J. Tizol, H. Lenk, W. Erwin Drake) (Debut DLP 2) 8’16

?2. SALT PEANUTS (D. Gillespie, K. Clarke) (Debut DLP 2) 7’36

?3. ALL THE THINGS YOU ARE (J. Kern, O. Hammerstein II) / 52nd STREET THEME (T. Monk)

(Debut DLP 2) 7’54

?4. WEE (D. Best) (Debut DLP 4) 6’46

?5. HOT HOUSE (T. Dameron) (Debut DLP 4) 9’09

?6. A NIGHT IN TUNISIA (D. Gillespie, F. Paparelli) (Debut DLP 4) 7’35

DIZZY GILLESPIE QUINTET with CHARLIE PARKER

Dizzy Gillespie (tp, voc), Miles Davis* (tp)?; Charlie Parker (as)?; Bill Graham (bs)?; Wade Legge (p)?; Lou Hackney (b)?;

Al Jones (dm)?; Joe Carroll (voc). Radio Broadcast, Birdland , NYC, 23/5/1953

?7. THE BLUEST BLUES* (C. Parker/D. Gillespie) (Radio Transcription) 6’39

?8. ON THE SUNNY SIDE OF THE STREET (J. McHugh/D. Fields) (Radio Transcription) 2’53

BUD POWELL TRIO with CHARLIE PARKER

Charlie Parker (as)?; Bud Powell (p)?; Charles Mingus (b)?; Art Taylor (dm) Candido (cga)?; Bob Garrity (mc).

WJZ Radio Broadcast, Birdland, NYC, 30/5/1953

?9. MOOSE THE MOOCHE (C. Parker) (Radio Transcription) 5’15

10. CHERYL / LULLABY OF BIRDLAND (C. Parker / G. Shearing) (Radio Transcription) 8’02

Charlie Parker (as)?; Bud Powell (p)?; Charles Mingus (b)?; Max Roach (dm). Same location and period

11. DANCE OF THE INFIDELS (B. Powell) (Radio Transcription) 5’28

Les étoiles * relient la présence ponctuelle d’un musicien ou d’un orchestre dans un ou plusieurs morceaux d’une séance