- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

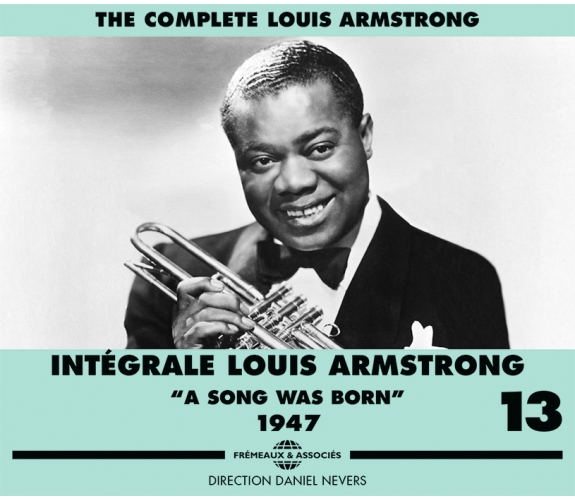

A SONG WAS BORN - 1947

LOUIS ARMSTRONG

Ref.: FA1363

Artistic Direction : DANIEL NEVERS

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Total duration of the pack : 3 hours 53 minutes

Nbre. CD : 3

A SONG WAS BORN - 1947

A SONG WAS BORN - 1947

“It is safe to say that among performing artists of the 20th century, only Charlie Chaplin was as universally recognized as Louis Armstrong.” Dan MORGENSTERN, Director, Institute of Jazz Studies, Rutgers University

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Way Down Yonder In New OrleansLouis Armstrong and OrchestraH. Creamer00:02:371947

-

2When The Saints Go Marchin InLouis Armstrong and OrchestraTraditionnel00:03:001947

-

32:19 BluesLouis Armstrong and OrchestraDesdoune00:04:201947

-

4Do You Know What It Means To Miss New OrleansLouis Armstrong and OrchestraE. De Lange00:04:121947

-

5Dippermouth BluesLouis Armstrong and Orchestra00:02:391947

-

6Basin Street BluesLouis Armstrong and OrchestraSp. Williams00:02:531947

-

7High SocietyLouis Armstrong and OrchestraP. Steele00:03:081947

-

8You Rascal YouLouis Armstrong and OrchestraS. Theard00:04:461947

-

9Theme Way Down Yonder In New OrleansLouis Armstrong and OrchestraH. Creamer00:01:491947

-

10Presentation By Fred Robbins/Cornet Shop SueyLouis Armstrong's QuartetLouis Armstrong00:03:361947

-

11Our Monday DateLouis Armstrong's QuartetE. Hines00:03:021947

-

12Dear Old SouthlandLouis Armstrong & Dick CaryH. Creamer00:03:371947

-

13Big Butter And Eggs ManLouis Armstrong's QuartetVenable00:04:101947

-

14Struttin' With Some BarbecueLouis Armstrong and His OrchestraL. Hardin00:03:351947

-

15Sweethearts On ParadeLouis Armstrong and His OrchestraNewman00:04:361947

-

16St Louis BluesLouis Armstrong and His OrchestraW.C. Handy00:03:211947

-

17Pennies From HeavenLouis Armstrong and His OrchestraBurke00:03:391947

-

18On The Sunny Side Of The StreetLouis Armstrong and His OrchestraD. Fields00:04:421947

-

19I Cant Give You Anything But LoveLouis Armstrong and His OrchestraD. Fields00:03:071947

-

20Back O'Town BluesLouis Armstrong and His OrchestraL. Russell00:04:091947

-

21Ain'T MisbehavinLouis Armstrong and His OrchestraA. Razaf00:03:511947

-

22Muskrat RambleLouis Armstrong and His OrchestraEd Ory00:02:111947

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Tiger RagLouis Armstrong and His OrchestraD.J. La Rocca00:05:251947

-

2Rockin' ChairLouis Armstrong and His OrchestraH. Carmichael00:05:061947

-

3Save It Pretty MamaLouis Armstrong and His OrchestraD. Redman00:04:251947

-

4St James InfirmaryLouis Armstrong and His OrchestraJ. Primerose00:03:331947

-

5Royal Garden BluesLouis Armstrong and His OrchestraC & Sp. Williams00:04:381947

-

6Do You Know What It Means To Miss New OrleansLouis Armstrong and His OrchestraE. De Lange00:03:391947

-

7Jack Armstrong BluesLouis Armstrong and His OrchestraLouis Armstrong00:04:361947

-

8PanamaLouis Armstrong and OrchestraW.H. Tyers00:01:251947

-

9When The Saints Go Marchin InLouis Armstrong and OrchestraTraditionnel00:02:231947

-

10Jack Armstrong BluesLouis Armstrong and His All-StarsLouis Armstrong00:03:011947

-

11Rockin ChairLouis Armstrong and His All-StarsH. Carmichael00:03:061947

-

12Some Day You'll Be SorryLouis Armstrong and His All-StarsLouis Armstrong00:03:121947

-

13Fifty Fifty BluesLouis Armstrong and His All-StarsB. Moore Jr00:02:591947

-

14Presentation And Way Down Yonder In New OrleansLouis Armstrong and His Original All-StarsH. Creamer00:03:231947

-

15Basin Street BluesLouis Armstrong and His Original All-StarsSp. Williams00:04:111947

-

16Muskrat RambleLouis Armstrong and His Original All-StarsEd Ory00:02:171947

-

17Dear Old SouthlandLouis Armstrong and His Original All-StarsH. Creamer00:03:191947

-

18Do You Know What It Means To Miss New OrleansLouis Armstrong and His Original All-StarsE. De Lange00:03:361947

-

19Some Day You'll Be SorryLouis Armstrong and His Original All-StarsLouis Armstrong00:04:301947

-

20Tiger RagLouis Armstrong and His Original All-StarsD.J. Larocca00:03:271947

-

21Goldwyn StompLouis Armstrong and Orchestra00:01:261947

-

22A Song Was BornLouis Armstrong and Orchestra00:04:131947

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1A Song Was Born (Version II)Louis Armstrong and Orchestra00:04:541947

-

2Muskrat RambleLouis Armstrong and The All-StarsEd Ory00:06:151947

-

3Black And BlueLouis Armstrong and The All-StarsA. Razaf00:04:141947

-

4Royal Garden BluesLouis Armstrong and The All-StarsC & Sp. Williams00:05:021947

-

5Stars Fell On AlabamaLouis Armstrong and The All-StarsParish00:05:181947

-

6I Cried For YouLouis Armstrong and The All-StarsG. Arnheim00:04:351947

-

7Since I Fell For YouLouis Armstrong and The All-StarsJohnson00:04:061947

-

8Tea Fot TwoLouis Armstrong and The All-StarsI. Caesar00:04:441947

-

9Body And SoulLouis Armstrong and The All-StarsSour00:05:321947

-

10Mahogany Hall StompLouis Armstrong and The All-StarsSp. Williams00:03:531947

-

11Steak FaceLouis Armstrong and The All-StarsTraditionnel00:07:111947

-

12On The Sunny Side Of The StreetLouis Armstrong and The All-StarsD. Fields00:06:491947

-

13High SocietyLouis Armstrong and The All-StarsP. Steele00:03:301947

-

14That's My DesireLouis Armstrong and The All-StarsL. Loveday00:04:441947

-

15Baby Won't You Please Come HomeLouis Armstrong and The All-StarsC. Warfield00:02:491947

-

16Bof Bof Mop MopLouis Armstrong and The All-StarsC. Hawkins00:05:071947

CLICK TO DOWNLOAD THE BOOKLET

Intégrale Louis Armstrong volume 13

THE COMPLETE louis armstrong 13

INTÉGRALE LOUIS ARMSTRONG 13

“A SONG WAS BORN”

1947

Louis ARMSTRONG – volume 13

Décidément, ce samedi 26 avril 1947 laissera certainement longtemps encore planer l’ombre du mystère sur la carrière de Louis Armstrong ! Normalement, il aurait dû se trouver en sa bonne vieille home town de La Nouvelle Orléans (Louisiane), afin d’assister au Saenger Theatre à la Première de ce film justement intitulé New Orleans, tourné l’automne d’avant et dont il avait été, en compagnie de ses copains du cru et de Billie Holiday, la vedette (enfin, presque…) (voir volume 12 – FA 1362). Eh bien non : il semble à peu près établi, après une longue et difficile enquête faisant intervenir d’aigües questions d’ADN, qu’il n’y alla pas, soit qu’il ne fût point invité, soit qu’il n’éprouvât guère l’envie de se replonger dans cette galère pelliculaire… Tout porte donc à croire que ce jour-là, il était tout bonnement du côté de chez la Grosse Pomme : New York… Et même qu’il y était plutôt actif, puisque qu’à cette date, on ne relève pas moins de deux émissions de radio différentes, théoriquement transmises en direct sur deux réseaux concurrents. L’ennui, c’est que les diffusions eurent lieu à peu près en même temps ! Moralité : l’une, au moins, n’était pas en direct !...

On pouvait supposer qu’il s’agissait de celle, venant en conclusion de notre volume 12 (CD 3, plages 19 à 21 – une malencontreuse coquille typographique sur le livret, à corriger sans délai, date ce broadcast du 26 février 47 et non du 26 avril), Saturday Night Swing Show, présentée par Art Ford pour la chaîne WNEW (585 Fifth Avenue 46th Street), dont plusieurs extraits furent édités sur V-Disc. Mais si c’était plutôt de l’autre, en provenance de la légendaire collection This is Jazz, qui occupa pacifiquement les antennes de la WOR Broadcast Co. de Manhattan et de la Mutual, (associée à la Canadian Broadcasting Commission), durant trente-cinq samedi après-midi, du 18 janvier au 4 octobre de ce lointain an 47 ? Le pianiste Art Hodes, participant de la seconde, était sûr, lui, après consultation en 1981 de son agenda d’époque, que tout cela s’était déroulé le vendredi 25 avril et avait donc été enregistré sur laques…

Au tout début, la série s’intitula d’abord ˮFor your Approvalˮ, avant de trouver son titre définitif, This is Jazz, produite par Don Fredericks, également responsable des annonces de début et de fin, et présentée par Rudi Blesh, dans le rôle du Maître de Cérémonies. Auteur d’un livre remarqué (mais toujours pas traduit en français !), Shining Trumpets, « traditionaliste intransigeant » – Boris Vian dixit – celui-ci avait décidé de laisser les gentils modernistics, boppers et assimilés, à ses collègues (dont son ennemi intime Leonard Feather), pour ne convier que des « Anciens » encore en activité (et même souvent fort actifs, comme Louis ou Bechet). Un petit orchestre de base assurait l’accompagnement des invités, réunissant souvent les mêmes vrais pros (Wild Bill Davison, George Brunies, Albert Nicholas…) capables d’accomplir de jolies prouesses. Car les émissions avaient (volontairement) ce côté informel, apparemment improvisé, auquel les responsables tenaient beaucoup. Elles connurent un succès quasi immédiat et purent revendiquer une belle indépendance, autorisant à se passer de sponsors et d’annonces commerciales – chose suffisamment rare dans ce pays pour être signalée. En revanche, Blesh se montra dit-on plutôt autoritaire, voire dictatorial, obligeant nombre de musiciens (à l’exception bien sûr des vedettes) à se présenter dans les boîtes où ils jouaient sous la bannière de ses émissions. Le cornettiste ˮMuggsyˮ Spanier, notamment, refusa tout net et ne fut plus jamais invité… Quant à Armstrong, il ne vint qu’une seule fois, le 26 (ou le 25 !) avril. Mais la raison est probablement tout autre… On ne sait pourquoi la série à succès fut interrompue assez brutalement le 4 octobre. Néanmoins, en guise de chant du cygne, le 17 février 1948 on diffusa sur les mêmes antennes un American Music Festival réunissant quelques anciens de This is Jazz (Davison, Brunies, Garvin Bushell…). Prélude à une nouvelle série peut-être ? Si c’est le cas, cela ne se concrétisa point.

Reste cette histoire de date. Pas très grave, dirons-nous. Certes. Mais quand même… Art Hodes affirmait donc que cela fut enregistré le 25. Or dans le dernier morceau, You, Rascal You, le tromboniste néo orléanais George Brunies, ancien des légendaires New Orleans Rhythm Kings puis du Jazz Band de Ted Lewis, très en verve ce jour-là, se permet un cri du cœur parfaitement graveleux, vers la fin de l’interprétation, quand Louis demande ˮwhat is it that you got, that make my wife think you’re so hot ?ˮ, l’autre clame ˮa glorified frankfurterˮ (on peut vérifier) ! Laissons-là la question de l’élégance, il reste évident que si l’émission avait été enregistrée, il eût suffi de refaire le morceau. Donc, on est bien le 26 avril et c’est bien du direct – théoriquement … Brunies fut mis au piquet et ne revint presque plus dans This is Jazz, alors que, pourtant, il se révèle tout à fait remarquable au cours de cette émission (Frankfort non comprise). Louis, en très grande forme lui aussi, n’avait jusqu’ici guère enregistré en sa compagnie. En revanche, il avait longuement eu comme partenaires Albert Nicholas et Pops Foster au temps de Luis Russell. Quant à ˮBabyˮ Dodds, il fallait remonter au temps des Hot Seven (1927), voire à l’époque du King Oliver’s (Creole) Jazz Band (1922-23). Satch’ paraît tout content de ce petit retour vers le passé, comme le prouve son enthousiasme à interpréter High Society, vieille baderne militaire transfigurée, et surtout Dippermouth Blues, fameuse composition du Roi et de son dauphin datant de ces jours tranquilles à Chicago. Évidemment, le film sortant juste à ce moment-là, il ne pouvait être question d’oublier Do You Know What It Means to Miss New Orleans. On s’en est donc souvenu à point nommé… Et puisqu’il est ici question de la Cité du Croissant, signalons que cette composition nettement plus ancienne d’Henry Creamer et Turner Layton (celui-là même qui fit, avec Johnston, un malheur en Europe dans un suave numéro de duettistes chantant), Way Down Yonder in New Orleans, servait d’indicatif à toutes les émissions, histoire d’annoncer la couleur, interprétée chaque fois par les invités et l’orchestre-maison.

1947, c’est aussi, surtout, un tournant décisif, irréversible, dans le parcours de Louis Armstrong. On en a déjà parlé (voir texte du volume 12) : la crise du grand orchestre, qui menaçait jusqu’aux plus fameux (Ellington, Basie, Goodman, Cab Calloway…), amena Satchmo à réduire ses effectifs et à se produire désormais en petit comité. Le film, déjà, fit avec succès la part belle à une de ces formations rappelant les années 1920. Le concert du 8 février 47 à « Carnegie Hall », donné en partie avec le sextette du clarinettiste Edmund Hall et en partie avec le big band, vint confirmer l’engouement du public pour la première formule (voir vol. 12). Les jeux étaient faits, mais Louis – et même son impresario peu enclin à la charité Joe Glaser – répugnaient à mettre sur le sable dix-huit ˮcats̏. On continua donc pendant quelques mois, jusqu’à ce que les choses se compliquent encore davantage… Finalement, durant l’été, la formation est dissoute et Satch’ prend la tête d’un ˮAll-Stars ˮ qu’il gardera, malgré nombre de changements, jusqu’à la fin de sa carrière.

C’est au « Billy Berg’s Club » d’Hollywood que, le 13 août, le nouveau groupe fera ses débuts officiels, sous les applaudissements de Johnny Mercer, Hoagy Carmichael, Woody Herman et bien d’autres, note Dan Morgenstern. Le pianiste Dick Cary, le jeune contrebassiste Arvell Shaw rescapé du grand orchestre, Sidney Catlett, batteur préféré d’Armstrong, et Barney Bigard, partenaire de Louis dans New Orleans, font partie de l’équipe. Le clarinettiste a quitté l’orchestre d’Ellington en 1942 parce que les tournées l’épuisaient. Le ˮAll-Stars ̏ se révèlera bientôt encore beaucoup plus fatiguant, qui fera si souvent le tour du monde – bien plus de trois fois! Au trombone et au chant, c’est Jack Teagarden qui s’est tout naturellement imposé. Lui et Louis ont enregistré ensemble dès 1929 (Knockin’ a Jug – voir vol. 5) et se sont retrouvés plusieurs fois, notamment fin 1938, en compagnie de Fats Waller, dans le programme radiophonique du disc-jockey Martin Block (voir vol. 9), puis le 18 janvier 44, lors du légendaire concert du « Metropolitan Opera » organisé par le magazine Esquire et, le 7 décembre de cette année-là, à l’occasion de la séance V-Disc (voir vol. 11)… ˮBig Teaˮ avait déjà une jolie carrière derrière lui : tromboniste chez Ben Pollack puis chez Paul Whiteman durant la seconde moitié des années 1920 et presque toute la décennie suivante, il avait lui aussi monté son big band. Mais à présent, en 46-47, plus rien ne tournait rond et le patron, couvert de dettes, fut ravi qu’Armstrong fasse appel à lui. En vérité, n’en déplaise aux racistes à-rebours, c’est le seul tromboniste – capable de lui donner aussi la réplique vocalement de sa voix superbement lazy – qu’il souhaitait réellement engager, un véritable frère comme il le disait lui-même, partenaire aussi idéal qu’Earl Hines avait su l’être aux jours de Chicago… A propos de Hines, on remarquera que pour réunir le vrai ˮAll-Stars ̏ définitif (du moins, jusqu’en 1951), ce dernier manque encore à l’appel. Il faudra attendre 1948 et le premier Festival de Nice…

Ce n’est pas tout à fait un hasard si le nouveau groupe fit ses débuts en Californie. Tout comme l’année d’avant à pareille époque, Louis s’y trouvait pour participer au tournage d’un film. Pas quelque chose comme le désespérant New Orleans, mais une amusante comédie réalisée par Howard Hawks, A Song is Born (en vf Si bémol et fa dièse !). En réalité, il s’agit d’une sorte de remake d’une autre comédie, Ball of Fire (1941), tournée par le même Hawks avec Gary Cooper, Barbara Stanwick et l’orchestre de Gene Krupa. Simplement ici, en 47, au lieu d’un sérieux linguiste/grammairien désireux de se mettre au slang quitte à fréquenter des gens pas très en règle avec la justice, on se trouve en présence d’un tout aussi sérieux professeur de musique (Dany Kaye), estomaqué par l’évolution de la chose et cherchant à tout prix à comprendre et apprendre le jazz. D’où une prolifération de chefs d’orchestres fameux, musiciens et chanteurs dans cette production de Samuel Goldwyn : Benny Goodman, Tommy Dorsey, Charlie Barnet, Mel Powell, Lionel Hampton, Louie Bellson, le Golden Gate Quartet, la chanteuse Jeri Sullivan, doublure-voix de Virginia Mayo, et bien entendu Louis Armstrong. Et il y a tout de même encore des gangsters pour rire… Certains morceaux sont malheureusement couverts par les bruits divers et le dialogue, mais on a pu récupérer quelques pré-enregistrements (comme pour New Orleans), nettement plus audibles. C’est le cas de Goldwyn Stomp (qui n’est point sans rappeler un certain Flying Home, cheval de bataille hamptonien) et surtout de deux moutures assez différentes de A Song was Born. L’une (CD 2, plage 22) provient de transcriptions de la chaîne radiophonique WOR, certainement gravées à des fins promotionnelles pendant les répétitions. On n’y entend pas les chorus chantés par le Golden Gate et Jeri Sullivan. En revanche, les solistes jouent et improvisent sur le thème en entier (trente-deux mesures) du début jusqu’à la fin, remarque Irakli qui ajoute que, dans la coda de cette version-ci, « Louis joue avec une maestria et une puissance confondantes ». La seconde mouture (CD 3, plage 1), plus longue, fut commercialisée sur un rare 78 tours, trente centimètres, de la maison Victor… au Japon ! Cette fois, l’introduction comporte bien les passages chantés, avant le vrai départ (le solo d’Armstrong). Surtout, on a considérablement raccourci (huit, ou seize, ou vingt-quatre mesures) les interventions de chaque musicien. Et la nouvelle coda se révèle moins brûlante, plus sage… C’est cette version-là qui fut insérée dans le film au montage. Pour des raisons mal connues, la RKO (Goldwyn ne fit jamais distribuer ses productions par la MGM !) ne sortit l’œuvre qu’à la fin de 1948, plus d’un an après le tournage, ce qui provoqua une série de confusions chez les discographes. Ainsi, dans leur ouvrage BG on the Record (Arlington House, 1970) D. Russ Connor et Warren W. Hicks datent-ils tout le paquet d’août 1948. Phil Schaap dans son Chronological Listing of Louis Armstrong’s Recordings (Jazz Session, 1980-87) commet la même bourde. Redisons-le : le film fut bien réalisé en août 1947 et, comme il se doit, l’enregistrement de la musique itou.

Les disques destinés au commerce ne sont, quant à eux, pas si nombreux. On a déjà croisé dans le précédent volume les cinq faces RCA du 12 mars 47 – la toute dernière séance du grand orchestre. Reste donc la séance du 10 juin que l’on trouvera sur le CD 2 (plages 10 à 13), en petite formation certes, mais quelque peu hybride, puisque faisant appel à Bobby Hackett au cornet, à deux saxophonistes non recrutés dans le futur ˮAll-Stars ̏, Peanuts Hucko et Ernie Caceres, non plus que le pianiste Johnny Guarnieri, Al Casey, ex-guitariste de Fats Waller et Cozy Cole à la batterie. L’occasion de graver enfin pour les collectionneurs de disques Jack-Armstrong Blues, titre tout autant inspiré par la complicité liant Tea et Louis (y compris dans la signature du thème) que par le titre d’un feuilleton radiophonique particulièrement populaire à l’époque), précise Alain Tercinet. Suit le beau Some Day, mais aussi le vieux Rockin’ Chair et le plus récent Fifty-Fifty Blues, où s’illustre le Teagarden chanteur, toujours totalement en phase avec Satchmo. Il y a encore, avec cette fois presque le ˮAll-Starsˮ, la session du 16 octobre : quatre pièces (dont A Song was Born) que l’on ne trouvera pas dans le CD 3, là où elles auraient chronologiquement dû se nicher. Impossible en effet de les inclure sans tronquer le concert donné au « Symphony Hall » de Boston le 30 novembre. Mieux valait conserver à celui-ci sa continuité et faire passer les titres du 16 octobre en tête du volume suivant. Ainsi soit-il…

Hackett, Hucko et Caceres ne firent pas que la séance du 10 juin. Très proches d’Armstrong en ce printemps, ils participèrent également neuf jours plus tard, le 19, à un concert tenu au « Winter Garden » de New York et diffusé à la radio – peut-être pas en direct. Le répertoire, comme il fallait s’y attendre, tend de plus en plus à se fixer sur les anciens succès : Way Down Yonder in New Orleans (en intro, dans la ligne de This is Jazz), Basin Street Blues, Muskrat Ramble, Tiger Rag, Dear Old Southland (duo trompette/piano, à la manière de 1930). Une petite place reste toutefois réservée aux nouveautés (Someday, Do You Know What it Means…). Un autre concert en date du 9 septembre, dont on n’a pas retrouvé de traces sonores, semble respecter les mêmes proportions. Et une double intervention radiophonique du 21 mai, dans le programme d’Henry Morgan, donne à entendre Panama et Oh When the Saints…, dans un arrangement identique à celui adopté par Louis et son big band pour l’enregistrement Decca du 13 mai 1938 (voir vol. 8 – FA 1358). Ici d’ailleurs (CD 2, plages 8 et 9), c’est bien aussi un big band qui l’accompagne, mais certainement pas le sien. Plutôt celui dirigé par un certain Benny Green…

Et puis surtout, trois concerts de première importance ont lieu en 1947 : celui de «Carnegie Hall» le 8 février, celui de « Town Hall » le 17 mai et celui du « Symphony Hall » de Boston le 30 novembre. Le premier, organisé par Leonard Feather avec l’accord de Joe Glaser, a déjà été évoqué et reproduit dans la présente intégrale. Le deuxième se trouve inclus ici dans sa totalité (du moins, on le suppose et on l’espère). Cette fois, c’est le publiciste Ernest Anderson, fanatique de jazz traditionnel, qui s’y colla. Glaser se montra nettement moins enthousiaste, mais un chèque (au porteur) de mille dollars permit de conclure l’affaire. Louis, pris à Philadelphie, ne pouvait s’occuper de l’intendance. Anderson s’en chargea avec l’aide de Bobby Hackett qui recruta Hucko, Dick Cary, Teagarden, le bassiste Bob Haggart, célèbre pour son duo avec le drummer Ray Beauduc sur Big Noise from Winnetka, et deux batteurs, George Wettling et Sidney Catlett. Un autre Sidney – Bechet – avait lui aussi été sollicité, mais il ne vint pas. On a ici vingt morceaux reproduits semble-t-il dans l’ordre exact de leur interprétation, y compris Do You Know What it Means… que l’on a un temps cru provenir d’un autre concert (ce que dément le petit sketch entre Louis, Tea et Fred Robbins le Maître de Cérémonies), et le dernier titre, Jack-Armstrong Blues, d’une qualité technique inférieure. Mais dans le numéro de juillet 47 de Pick-Up Magazine, Robert Sylvester en dénombre vingt-sept. R.A. Israel n’en compte, dans l’ordre, que dix-neuf, omettant Do You Know What it Means… et terminant par Jack-Armstrong…, tandis que d’autres en indiquent deux douzaines. Et se pose aussi la question de la durée réelle du concert et de son déroulement. N’y en eut-il pas plutôt deux ? C’est là ce que soutient Dan Morgenstern : un prévu initialement à minuit (ainsi que le mentionne l’affiche officielle) et un autre à vingt heures, au pied levé en somme, tant les locations étaient saturées… Dans une interview publiées des années plus tard, Anderson ne signale rien de semblable. Mais si c’est le cas, les participants furent-ils payés double? On peut rêver…

Avec deux concerts à la clef, on s’explique évidemment mieux les divergences entre témoins sur le nombre de morceaux effectivement interprétés. Quoiqu’il en soit, une fois encore le répertoire traditionnel se taille la part du lion, de Cornet Chop Suey à Royal Garden Blues, en passant par Tiger Rag, Big Butter and Egg Man, Struttin’ with some Barbecue, St. Louis Blues ou Muskrat Ramble. Portion congrue pour les choses un poil plus jeunes (enfin, presque) : Pennies from Heaven, Back O’Town Blues, Do You Know What… ou Jack-Armstrong Blues… Et c’est parti pour durer.

Les premiers titres sont joués en quartette (Louis et la rythmique – le batteur étant ici plus que probablement Catlett, reconnaissable dès les premières mesures de Cornet Chop Suey) et Dear Old Southland est donné en duo, comme d’habitude. Juste avant ce morceau, le groupe s’était attaqué à cette fameuse composition d’Earl Hines, Our Monday Date, gravée avec Louis en juin 1928. Ensuite, on est censé passer à un autre tube du temps de Chicago, Big Butter and Egg Man. Distrait, trompé par les harmonies assez proches, Dick Cary reprend sans broncher l’introduction de Monday Date et Louis, tranquillement, lui emboîte le pas !... Ce n’est qu’au bout de dix-neuf mesures qu’il s’apercevra qu’il ne joue pas Big Butter et rectifiera le tir !

A partir de Tiger Rag, la formation au complet (citée par Robbins au début du concert) prend pleinement possession de la scène. Guère besoin de souligner que toutes les interventions de Satchmo sont éblouissantes, malgré une certaine nervosité, vite domptée, due peut-être à la conscience qu’il éprouvait de se trouver à un nouveau tournant de son histoire… On ne manquera pas non plus d’admirer l’autorité superbe de ce monstre de la percussion jazz que fut Sidney Catlett, infaillible meneur de grands solistes qui travailla dans la plupart des big bands des années 1930 et participa à l’enregistrement historique des premiers disques ˮbebopˮ (1945) avec Parker et Gillespie… On n’oubliera pas non plus les belles performances de Teagarden, tromboniste et chanteur, que le purisme traîna systématiquement en dessous du niveau de la boue.

L’ultime séance de disques d’Armstrong pour la maison RCA eut lieu, on l’a signalé, le 16 octobre 1947. Toutefois, au début de l’année suivante, la firme fit l’acquisition de six titres issus du concert de « Town Hall », Ain’t Misbehavin’, Rockin’ Chair, Back O’Town Blues, Pennies from Heaven, Save It Pretty Mama et St. James Infirmary, qu’elle édita sous étiquette Victor sur trois 78 tours trente centimètres (puis réédita souvent en microsillon). Chose curieuse : Louis ne joue absolument pas dans St. James (qu’il a pourtant fréquemment interprété depuis 1928), devenu une « spécialité » de Teagarden… Ainsi déjà est prise l’habitude de faire intervenir tel ou tel soliste sans que le patron s’en mêle obligatoirement. Nous avons inclus ce titre afin de donner un (bon) exemple de cette pratique. Nous ne le ferons pas à chaque fois…

Ainsi, par exemple, dans le concert suivant, donné le 30 novembre au « Symphony Hall » de Boston et cette fois encore produit par Ernest Anderson, avons-nous exclus un certain nombre de pièces : ce long solo du bassiste Arvell Shaw sur How High the Moon, le ˮC Jam Blues de Bigard et Lover par Teagarden. En revanche, Stars Fell in Alabama chanté par le même a été gardé, ainsi que Tea for Two, autre cheval de bataille bigardien, puisque Louis intervient sur ces deux morceaux. Tout comme il se glisse aussi dans certaines « spécialités » de ses partenaires : I Cried for You (Velma Middleton), Baby Won’t You Please Come Home (Tea), Steak Face et Boff Boff (alias Mop Mop) (Catlett)…

Le concert dut être enregistré sur laques (acétates) puis transféré sur bandes magnétiques. Seules celles-ci paraissent avoir survécu, donnant naissance au printemps 1951 à un double album 33 tours 30 centimètres, édité sous étiquette Decca (DL 3087/3088). Par la suite, les morceaux furent pour la plupart également proposés en 45 tours… L’ensemble durait quatre-vingt-huit minutes, on suppose qu’il n’y eut pas d’autres morceaux et que l’ordre des pièces a été respecté. Ce qui, en revanche, a été sacrifié, ce sont les interventions parlées de Louis et son équipe entre chaque interprétation. À l’époque, la technique nouvelle de la gravure microsillon étant encore dans sa prime enfance, il fallait gagner du temps et, donc, shunter sur les applaudissements dès le morceau terminé… On a d’ailleurs à peu près le même problème avec le concert de « Town Hall », où ne subsistent que l’introduction de Robbins et un petit dialogue vers la fin. Dommage. Mais il est probable aussi, à en juger par ce qui a survécu, que la qualité sonore ne devait pas être bien fameuse. Et, à propos de menus ennuis, on peut remarquer que si Armstrong semble en cette fin novembre en bonne forme tant comme trompettiste que comme chanteur, Teagarden et Velma, de leur côté, paraissent passablement enroués. Il est vrai que l’hiver n’est plus très loin et que Boston n’est pas la plus chaude des villes américaines ! Alors un bon petit coup de froid… Ce qui n’empêcha point la salle, plutôt habituée à recevoir Koussevitsky et l’orchestre symphonique local ou les ˮpops̏ concerts d’Arthur Fiedler, d’être archi-comble. Mais ce coup-ci, il n’y eut pas de seconde chance pour les retardataires.

Ainsi, Louis Armstrong et son All-Stars se trouvaient fin prêts à s’envoler vers de nouvelles aventures…

Daniel NEVERS

© 2014 Frémeaux & Associés

Louis ARMSTRONG – Vol.13

There was a Saturday (actually April 26th 1947) that would definitely leave an aura of mystery hanging over Armstrong’s career for a long, long time… Under other circumstances, he would have been in his good old hometown of New Orleans, Louisiana, sitting in the Saenger Theatre at the premiere of his movie New Orleans (of course), a film shot the previous autumn with Louis and a few of his local buddies, plus Billie Holiday, the star of the picture (or almost… cf. Vol. 12, FA1362). But he wasn’t there: after a long and difficult probe into some acute DNA issues, it seems almost certain that Louis didn’t attend. Either he didn’t get an invitation or he didn’t feel like ever getting close to such an irritating film again… So, all the evidence points to his being in the Big Apple (New York if you prefer) on that Saturday, and even to the fact that he must have been rather busy there, because the schedules show him involved in two separate radio broadcasts (on two different stations) which went out “live”… The problem is that both shows took place at around the same time! As for the moral of the story: at least one of them must have been pre-recorded.

It’s fair to suppose that the recorded show was the one which concludes our Vol. 12 (CD3, tracks 19-21) — an unfortunate printer’s error in the booklet (to be corrected without delay) has the broadcast dated on February 26th 1947 and not April 26th —, i.e. the Saturday Night Swing Show, introduced by Art Ford for WNEW in New York (on the corner of 585 Fifth Avenue and 46th Street), several excerpts of which were issued on V-discs. But what if it was the other show? That was one of the legendary This is Jazz series, which coolly kept the transmitters busy for Manhattan’s WOR Broadcast Co. and the Mutual station (affiliated to the Canadian Broadcasting Commission), over some thirty-five Saturday afternoons between January 18th and October 4th 1947. In 1981, pianist Art Hodes, who played on the show, took a look in his diary for 1947 and was categorical: all of it went down on Friday April 25th when it was recorded on lacquers…

In the very beginning, the series was called For your Approval (before gaining its definitive title This is Jazz); it was produced by Don Fredericks (also responsible for the opening and closing announcements) and introduced by Rudi Blesh, the acting Master of Ceremonies. Rudi, the author of a remarkable book called Shining Trumpets — Boris Vian called him an “intransigent traditionalist” —, had decided to leave the genteel ’modernists’ (boppers and their like) to his colleagues, among them his nemesis Leonard Feather, and summon to the studio only the “old guys” still on the scene (and sometimes highly active guys they were, too, like Louis or Bechet). To accompany his guests he’d called in a small band which sometimes featured the same real pros (Wild Bill Davison, George Brunies, Albert Nicholas…) capable of putting in a nice little performance now and then. The fact is that these shows were — quite deliberately — informal occasions, in keeping with the seemingly-improvised aspect which the producers liked so much. The shows were an almost immediate hit with audiences, and justifiably claimed a handsome independence: it allowed them to do without sponsors and their commercials. It was a rare thing, and so it deserves a mention. On the other hand, it’s said that Rudi Blesh showed himself to be something of an authoritarian, if not a dictator, in obliging many musicians (except the stars, of course) to play gigs in clubs under his banner, to promote his programmes. Cornet-player Muggsy Spanier, notably, refused point blank, and so was never invited to do the show… As for Louis, he went just once, on April 26th (or the 25th!). But maybe that was for another reason altogether. Nobody knows why this hit series came to such an abrupt end on October 4th, but there was a swansong: the same station did a broadcast on February 17th 1948 called American Music Festival, which reunited some of the old guys from This is Jazz (Davison, Brunies, Garvin Bushell…). It could have been intended as a prelude to a new series, but the first was the only one.

There remains the problem regarding the date. Not a major issue, you might say. And you’d be right. But even so, Art Hodes, you may remember, said it was recorded on the 25th. But in the last piece, You, Rascal You, New Orleans trombonist George Brunies, an ancient alumnus of the legendary New Orleans Rhythm Kings and then Ted Lewis’ Jazz Band, shows a great deal of verve in giving vent to quite a gritty, heartfelt response towards the end of the performance: when Louis asks, “What is it that you got, that makes my wife think you’re so hot?”, George chimes in with, “A glorified frankfurter!” Check it out. Never mind the theorising about whether George was being elegant or not… It’s obvious that if the programme had been recorded, they could have done another take. So this was April 26th and the show was indeed ’live’. In theory, that is. Brunies was hung out to dry and almost never reappeared on This is Jazz, even though he plays quite remarkably throughout the whole proceedings (Frankfurt notwithstanding). Louis is in great shape, too, and until then he’d hardly ever recorded in his company. Albert Nicholas and Pops Foster, however, had been Louis’ partners for a long time, playing with Luis Russell. As for Baby Dodds, you’d have to go back to the Hot Seven (1927), or even to the days of King Oliver’s (Creole) Jazz Band (c. 1922-23). Satch’ seems quite happy about this return to the old days, as shown by his enthusiastic rendering of High Society, a transfigured old fogey in the military, and especially Dippermouth Blues, the famous composition by the King and his heir to the throne dating from those quiet days in Chicago. Obviously, in the context (the film had just reached the cinemas), they were bound to play Do You Know What It Means to Miss New Orleans. So they did that one, too. And while we’re on the subject of the Crescent City, note that this much older Way Down Yonder in New Orleans, a composition by Henry Creamer and Turner Layton (the same “Layton” who, together with “Johnston”, went down a storm in Europe singing a suave duet-number), was adopted as a signature-tune to set the tone for the whole series; it was played every time by the house-band and its guests.

1947 also marked a milestone, a decisive, irreversible turning-point in Louis Armstrong’s career. We’ve already mentioned this (cf. the booklet with Vol. 12): the big-band crisis, which was already looming over the most famous orchestras (Ellington, Basie, Goodman, Cab Calloway…), obliged Satchmo to reduce the headcount and in future appear with small-groups. Even the above-mentioned film had successfully featured one of those formations reminiscent of the Twenties. The Carnegie Hall concert on February 8th 1947 — partly with a sextet led by clarinettist Edmund Hall and the rest with the big band — was a timely confirmation of the public’s taste for the smaller format (cf. Vol. 12). The dice were down, but Louis — and even his impresario Joe Glaser, who had little inclination towards charity — drew the line at putting eighteen “cats” out to graze. So they carried on for a few more months, until things became even more complicated than they were before. Finally, during the summer, they disbanded, and Satch’ began fronting an All-Stars group; it would remain with him, despite numerous changes, until the end of his career.

The group would make its official debut at Billy Berg’s Club in Hollywood, on August 13th, to a round of applause from Johnny Mercer, Hoagy Carmichael, Woody Herman and many others, as Dan Morgenstern notes. Among the crew were pianist Dick Cary, the young bassist Arvell Shaw (a survivor from the big band), Sidney Catlett, Armstrong’s favourite drummer, and Barney Bigard, who’d been Louis’ partner in the New Orleans movie. Bigard and his clarinet had quit Ellington in 1942 because the tours were too exhausting. The All-Stars would soon turn out to be much more tiring, as they would travel all the way around the world… at least three times! On trombone and vocals, Jack Teagarden was (naturally) the man for the occasion. He and Louis had recorded together as early as 1929 (cf. Knockin’ a Jug, Vol. 5), and had got together on several occasions in the interval, notably at the end of 1938 in the company of Fats Waller, for disc-jockey Martin Block’s radio programme (cf. Vol. 9), on January 18th 1944 (at the legendary Metropolitan Opera concert set up by Esquire magazine) and on December 7th that same year, for a V-Disc session (cf. Vol. 11)… “Big T” already had a nice little career under his belt: he’d been Ben Pollack’s trombone, and also played with Paul Whiteman (in the latter half of the Twenties and for almost all of the following decade). He, too, had led his own big-band. But now, in 1946-47, everything was going haywire, and Big T, as a bandleader out of his depth in debt, was delighted when Armstrong gave him a call. To tell the truth — flying in the face of racists, whether they like it or not — Teagarden was the only trombonist (also vocally capable of giving a suitable cue to Louis’ own superbly lazy voice) whom Armstrong really wanted in his band. As he said himself, Jack was like a brother, a partner as ideal as Earl Hines had been in the Chicago days… Speaking of Hines, you might note that when the real All-Stars were formed, the definitive group (until 1951, at least), Hines was missing. People had to wait until 1948 and the first Nice Festival in France.

If this new group made its debut in California, it had nothing to do with chance. Louis was in California for the needs of a film (as he had been the previous year at the same time). Not a film like the desperate New Orleans effort, but an agreeable comedy directed by no less than Howard Hawks, A Song is Born [French viewers, by the way, went to see the same film entitled B flat and F sharp!]. The film was really a kind of remake of another Howard Hawks comedy from 1941 called Ball of Fire (it featured Gary Cooper, Barbara Stanwyck and Gene Krupa’s band). This time, however, instead of a film about a serious linguist/grammarian who wants to learn slang even if it means hanging out with people whom the law consider to be, well, undesirable, we have a remake giving us an equally serious music-teacher (Danny Kaye) who is so gobsmacked by the turn of events that his desire to understand jazz leads him on a kind of quest for the Holy Grail. Hence the abundance of famous bandleaders, musicians and singers in this new Sam Goldwyn production from 1947: Benny Goodman, Tommy Dorsey, Charlie Barnet, Mel Powell, Lionel Hampton, Louie Bellson, The Golden Gate Quartet, singer Jeri Sullivan (the voice-double for actress Virginia Mayo) and, of course, Louis Armstrong. And there are even gangsters in this one, too, just for laughs. Some of the tunes are unfortunately drowned out by background noise and chit-chat, but we’ve been able to recover a few of the pre-recordings (as with New Orleans) which are much more audible. Goldwyn Stomp for example (which clearly recalls Hampton’s battle-cry Flying Home) and, above all, two rather different versions of A Song was Born. One of them (CD 2, track 22) has radio WOR transcriptions as its source, recordings which were certainly cut during rehearsals in order to promote the movie. In these, you can’t hear the choruses sung by The Golden Gate Quartet and Jeri Sullivan. On the other hand, you can hear the soloists playing improvisations “over the whole tune (thirty-two bars) from beginning to end”, as Irakli observed. He goes on to add that in the coda of this version, “Louis plays with consummate skill and astounding power.” The second version (CD 3, track 1), much longer, was released for sale on a rare 12” 78rpm record by Victor… in Japan only! This time the introduction does include parts that are sung, before the actual start (Armstrong’s solo). Most noticeably, the contributions of each musician are considerably shortened (eight, sixteen or twenty-four bars), and the new coda turns out to be less hot, more well-behaved. For some little-known reason, RKO — Goldwyn never had his productions distributed by MGM! — didn’t issue this one until the end of 1948, more than a year after the film was made, which threw discographers into confusion: in their BG on the Record (Arlington House, 1970), D. Russ Connor and Warren W. Hicks date the whole bundle from August 1948; Phil Schaap, in his Chronological Listing of Louis Armstrong’s Recordings (Jazz Session, 1980-87), makes the same blunder. At the risk of repeating ourselves, the film was made in August 1947, and the music was recorded then also.

The commercial records Louis made were/are not that many in number. In the previous volume we dealt with the five RCA sides from March 12th 1947, which was the big band’s very last session. So there remains the June 10th session which you can find on CD2 (tracks 10-13), a small group, of course, but quite a hybrid in that it features Bobby Hackett on cornet, plus two saxophonists who weren’t recruited for the future All-Stars (Peanuts Hucko and Ernie Caceres), no more than were the pianist Johnny Guarnieri, Fats Waller’s ex-guitarist Al Casey, or Cozy Cole on drums. Alain Tercinet points out that the session was, at last, a chance to record Jack-Armstrong Blues for collectors, a title inspired just as much by the complicity between “T” and Louis (even down to the joint signature of the composition) as it was by the title of a contemporary radio show which was extremely popular. The fine tune Some Day follows it, but also the older Rockin’ Chair and the more recent Fifty-Fifty Blues, on which Teagarden shines as a singer, still totally in phase with Satchmo. There was still another session, this time with the almost-All Stars, on October 16th: four pieces (including A Song was Born) which you will not find on CD3 (where they should be, chronologically speaking). The reason being that it was impossible to fit them in without amputating part of the Symphony Hall concert in Boston dated November 30th. It seemed much better to preserve the continuity of the latter, and reserve the October 16th titles for the beginning of the next volume in this series. Amen.

The June 10th session wasn’t the only date with Hackett, Hucko and Caceres. They were very close to Armstrong that spring, and nine days later they also took part in a concert at New York’s Winter Garden which was aired on radio — but maybe not “live”. The repertoire, as might be expected, was leaning more and more towards former hits: Way Down Yonder in New Orleans (their opener, as per the This is Jazz series), Basin Street Blues, Muskrat Ramble, Tiger Rag and Dear Old Southland (a trumpet/piano duet à la 1930). They did, however, reserve a small place for newer pieces (Someday, Do You Know What it Means…). Another concert dated September 9th — there’s no trace of it for would-be listeners — seems to have respected the same ratio, and there was a double radio appearance on May 21st in Henry Morgan’s show which gave people a chance to hear Panama and Oh When the Saints… in an arrangement identical to the one adopted by Louis and his big band for the Decca recording made on May 13th 1938 (cf. Vol. 8, FA1358). While on the subject, a big band also accompanies him here (CD2, tracks 8 & 9), but not his own band: more likely the one led by one Mr. Benny Green…

Above all, there were the three major concerts which took place in 1947: Carnegie Hall on February 8th, Town Hall on May 17th and the one at Symphony Hall in Boston on November 30th. The first, organized by Leonard Feather in agreement with Joe Glaser, has already been referred to (and included in) this series of Louis’ complete works. The second can be found here in its entirety, or at least we suppose (and hope) so. This Town Hall date was set up by publicist Ernest Anderson, a traditional-jazz fanatic; Glaser showed a lot less enthusiasm over this one, but a $1000 cheque (made out to the bearer!) did most of the talking to seal the deal. Louis was busy in Philadelphia and couldn’t take care of the logistics, so Anderson took charge with the help of Bobby Hackett, who recruited Hucko, Dick Cary, Teagarden, bassist Bob Haggart (famous for Big Noise from Winnetka, a duet with drummer Ray Beauduc), plus George Wettling and Sidney Catlett on drums. Another Sidney – Bechet – had also been solicited, but he didn’t come. Here we’ve included twenty pieces in what appears to be the exact order in which they were played, including Do You Know What it Means… which for a time was thought to be from a different concert — disproved by the little skit between Louis, Big T and Fred Robbins, the MC —, and the last title, Jack-Armstrong Blues, of lesser technical quality. But in the July ’47 issue of Pick-Up Magazine, Robert Sylvester lists twenty-seven; R.A. Israel only counted, in order, nineteen, omitting Do You Know What it Means… and ending with Jack-Armstrong…, whereas other sources indicate two dozen. There’s also an issue over the real duration of the concert and the playing-order. Weren’t there rather two concerts? That hypothesis is Dan Morgenstern’s: one set planned initially for midnight (as the official bill says), and another at eight p.m., a necessary extra, you might say, given the demand for seats. In an interview published years later, Anderson doesn’t suggest anything like it, but if there really were two sets, was there a chance that the participants were paid double? You can always dream…

Two concerts would also better explain the divergences in the accounts of witnesses regarding the number of pieces that were actually played. Whatever the reality, the traditional repertoire once again takes the lion’s share, from Cornet Chop Suey to Royal Garden Blues, via Tiger Rag, Big Butter and Egg Man, Struttin’ with some Barbecue, St. Louis Blues or Muskrat Ramble. The meaner share included things a shade more recent (well, almost): Pennies from Heaven, Back O’Town Blues, Do You Know What… or Jack-Armstrong Blues… And that was how things would remain.

The first are quartet-titles (Louis and the rhythm-section, with the drummer here probably Catlett, recognizable as soon as you hear the first bars of Cornet Chop Suey) while Dear Old Southland is a duet, as usual. Just before this piece, the group has a go at Earl Hines’ famous composition Our Monday Date, which had been recorded with Louis in June 1928. Next, we have supposedly another hit from the Chicago days, Big Butter and Egg Man. Dick Cary absent-mindedly picks up the introduction to Monday Date without batting an eyelid, and Louis serenely follows suit! Nineteen bars go by before he realizes he’s not playing Big Butter and sets things straight…

From Tiger Rag onwards, the complete formation (named by Robbins at the beginning of the concert) takes full possession of the stage. There’s hardly any need to underline Satchmo’s contributions, which are all dazzling despite some nervousness, quickly tamed, that is perhaps due to his realization that he was on the verge of a brand new chapter in his own story… You also have to admire the superb authority of the jazz percussion-master named Sidney Catlett: an infallible lead for the great soloists working in most of the Thirties big bands, he also took part in the historic first bebop recordings (1945) with Parker and Gillespie… Not to be forgotten either: the beautiful performances of Jack Teagarden, Trombonist and Singer, and Victim, due to the purists who systematically dragged him under the mud.

Armstrong’s final record-session for RCA took place on October 16th 1947, as we’ve said before. However, the following year, the firm acquired six titles which came from this Town Hall concert: Ain’t Misbehavin’, Rockin’ Chair, Back O’Town Blues, Pennies from Heaven, Save It Pretty Mama and St. James Infirmary, which were released under the Victor label printed on three 12” 78s (and often reissued on LP). Curiously, Louis doesn’t play a note on St. James (even though he’d been frequently playing it since 1928): it had become a “Teagarden special”… Hence the future habit of letting one soloist or another come in without the boss necessarily being part of the proceedings. We included this title here as a (good) example of this Armstrong practice. But we won’t do that all the time…

Take the following concert, for example, played on November 30th at Boston’s Symphony Hall, and again organized by Ernest Anderson, from which we have excluded a certain number of pieces: that long solo by bassist Arvell Shaw on How High the Moon, Bigard’s C Jam Blues and Lover by Teagarden. On the other hand, Stars Fell in Alabama, sung by the same Big T, has been retained, and also Tea for Two, another old Bigard war-horse, due to Louis’ contributions on both these pieces. He also slips into some of his other partners’ “specialities”: I Cried for You (Velma Middleton), Baby Won’t You Please Come Home (T), Steak Face and Boff Boff — alias Mop Mop — (Catlett)…

The concert had to be recorded onto lacquers (acetates) before being transferred onto magnetic tape. Only the latter seem to have survived and in spring 1951 they gave birth to a double 12” LP released by Decca (DL 3087/3088). Later, most of these pieces were also put out on 45rpm records… The whole concert lasted some eighty-eight minutes, so we suppose that these were the only pieces and that the running order was respected. What have been sacrificed, on the other hand, are Louis’ spoken interventions (and those of his band) in between each title. At the time they were made, the new LP recording-technique was still in its infancy and time was of the essence, hence the shunted applause at the end of each number. In this respect, we have almost the same problem with the Town Hall concert, of which only Robbins introduction remains, together with a short bit of dialogue towards the end. What a shame! But it’s also probable, judging by what survived, that the sound quality must have left a lot to be desired. Speaking of problems, you might note that if Armstrong sounds in fine fettle towards the end of this November, both as a trumpeter and as a vocalist, Teagarden and Velma, for their part, both sound rather hoarse. It’s true that winter wasn’t so far away, and that Boston is not exactly the warmest of American cities! Maybe there was a draught. Not that it prevented the audience, more accustomed to Koussevitzky and the local Symphony Orchestra, or Arthur Fiedler and the Boston Pops, from fighting over seats. But this time, latecomers didn’t get a second chance to see Louis. He and his All Stars were already packing for their next adventure…

Adapted by Martin Davies from the French text by Daniel Nevers

© 2014 Frémeaux & Associés

DISQUE / DISC 1

“THIS IS JAZZ” (radio – New York City, 25 ou/or 26/04/1947)

Louis ARMSTRONG (tp, voc) ; William E. “Wild Bill” DAVISON (cnt) ; George BRUNIES (tb, voix/voices) ; Albert NICHOLAS (cl) ; Art HODES (p) ; Danny BARKER (g) ; George “Pops” FOSTER (b) ; Warren “Baby” DODDS (dm) ; Rudi BLESH (mc). WOR Broadcast (acetates).

1. Presentation & theme WAY DOWN YONDER IN NEW ORLEANS (H.Creamer-T.Layton) 2’37

2. WHEN THE SAINTS GO MARCHIN’ IN (Trad.) 3’00

3. 2:19 BLUES (Desdoune) 4’20

4. DO YOU KNOW WHAT IT MEANS TO MISS NEW ORLEANS ? (L.Alter-E.de Lange) 4’12

5. DIPPERMOUTH BLUES (J.Oliver-L.Armstrong) 2’39

6. BASIN STREET BLUES (Sp.Williams) 2’53

7. HIGH SOCIETY (P.Steele) 3’08

8. YOU, RASCAL YOU (S.Theard) 4’46

9. Theme : WAY DOWN YONDER IN N. O. (H.Creamer-T.Layton) 1’49

TOWN HALL CONCERT (New York City, 17/05/1947)

LOUIS ARMSTRONG’S QUARTET (10, 11, 13) : Louis ARMSTRONG (tp, voc) ; Richard “Dick” CARY (p) ; Bob HAGGART (b) ; Sidney CATLETT (dm). Louis ARMSTRONG (tp) & “Dick” CARY (p) – duo/duet (12). Louis ARMSTRONG AND HIS ORCHESTRA (14 à/to 22) : Louis ARMSTRONG (tp, voc) ; Robert L. “Bobby” HACKETT (tp) ; Jackson TEAGARDEN (tb, voc) ; Michael A. “Peanuts” HUCKO (cl) ; “Dick” CARY (p) ; Bob HAGGART (b) ; Sidney CATLETT (dm).

10. Presentation par/by Fred ROBBINS & CORNET CHOP SUEY (L.Armstrong) 3’36

11. OUR MONDAY DATE (E.Hines) 3’02

12. DEAR OLD SOUTHLAND (H.Creamer-T.Layton) 3’37

13. BIG BUTTER AND EGGS MAN (Venable) 4’10

14. STRUTTIN’ WITH SOME BARBECUE (L.Hardin) 3’35

15. SWEETHEARTS ON PARADE (Newman-Lombardo) 4’36

16. ST. LOUIS BLUES (W.C.Handy) 3’21

17. PENNIES FROM HEAVEN (Burke-Johnston) (RCA-Victor 40-4005 / mx. D8-VC-76) 3’39

18. ON THE SUNNY SIDE OF THE STREET (J.McHugh-D.Fields) 4’42

19. I CAN’T GIVE YOU ANYTHING BUT LOVE (J.McHugh-D.Fields) 3’07

20. BACK O’TOWN BLUES (L.Armstrong-L.Russell) (RCA-Victor 40-4006 / mx. D8-VC-75) 4’09

21. AIN’T MISBEHAVIN’ (T.Waller-A.Razaf) (RCA-.Victor 40-4005 / mx. D8-VC-73) 3’51

22. MUSKRAT RAMBLE (Ed.Ory) 2’11

DISQUE / DISC 2

TOWN HALL CONCERT (New York City, 17/05/1947)

LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND HIS ORCHESTRA (1 à/to 3 & 5 à/to 7) : Louis ARMSTRONG (tp, voc); Bobby HACKETT (tp) ; Jack TEAGARDEN (tb, voc) ; Peanuts HUCKO (cl) ; Dick CARY (p) ; Bob HAGGART (b) ; George WETTLING (dm).

JACK TEAGARDEN (tb, voc), acc. par/by Dick CARY (p) ; Bob HAGGART (b) ; George WETTLING (dm) (4).

1. TIGER RAG (D.J.LaRocca) 5’25

2. ROCKIN’ CHAIR (H.Carmichael) (RCA-Victor 40-4004 / mx. D8-VC-74) 5’06

3. SAVE IT, PRETTY MAMA (Don Redman) (RCA-Victor 40-4006 / mx. D8-VC-77) 4’25

4. ST. JAMES INFIRMARY (J.Primerose) (RCA-Victor 40-4004 / mx. D8-VC-78) 3’33

5. ROYAL GARDEN BLUES (C. & Sp.Willams) 4’38

6. DO YOU KNOW WHAT IT MEANS TO MISS NEW ORLEANS ? (L.Alter-E.de Lange) 3’39

7. JACK-ARMSTRONG BLUES (L.Armstrong-J.Teagarden) 3’01

LOUIS ARMSTRONG IN HENRY MORGAN SHOW (radio – station unknown)

Louis ARMSTRONG (tp, voc), L. AUTRAY (tp) & autres musiciens non indentifiés/& other unidentified musicians. Grande formation / Large big band. Benny GREEN (dir). New York City, 21/05/1947.

8. PANAMA (W.H.Tyers) 1’25

9. WHEN THE SAINTS GO MARCHIN’ IN (Trad.) 2’23

LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND HIS ALL-STARS

Louis ARMSTRONG (tp, voc) ; Bobby HACKETT (tp) ; Jack TEAGARDEN (tb, voc) ; Peanuts HUCKO (cl) ; Ernie CACERES (bars, cl) ; Johnny GUARNIERI (p, celeste) ; Albert CASEY (g) ; Al HALL (b) ; William “Cozy” COLE (dm). New York City, 10/06/1947.

10. JACK-ARMSTRONG BLUES (L.Armstrong-J.Teagarden) (RCA-Victor 20-2348/mx.D7-VB-952-2) 3’01

11. ROCKIN’ CHAIR (H.Carmichael) (RCA-Victor 20-2348/mx.D7-VB-953- ) 3’06

12. SOME DAY (YOU’LL BE SORRY) (L.Armstrong) (RCA-Victor 20-2530/mx.D7-VB-954-1) 3’12

13. FIFTY-FIFTY BLUES (B.Moore Jr.) (RCA-Victor 20-2530/mx.D7-VB-955-2) 2’59

LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND THE ORIGINAL ALL-STARS (concert – radio)

Louis ARMSTRONG (tp, voc) ; Bobby HACKETT (tp) ; Jack TEAGARDEN (tb, voc) ; Peanuts HUCKO (cl) ; Ernie CACERES (bars, cl) ; Dick CARY (p) ; Jack LESBERG (b) ; George WETTLING (dm). Louis ARMSTRONG (tp) & Dick CARY (p) – duo/duet sur/on 17. New York City (Winter Garden Theater), 19/06/1947.

14. Presentation & WAY DOWN YONDER IN NEW ORLEANS (H.Creamer-T.Layton) 3’23

15. BASIN STREET BLUES (Sp.Williams) 4’11

16. MUSKRAT RAMBLE (Ed. Ory) 2’17

17. DEAR OLD SOUTHLAND (H.Creamer-T.Layton) 3’19

18. DO YOU KNOW WHAT IT MEANS TO MISS NEW ORLEANS ? (L.Alter-E.de Lange) 3’36

19. SOME DAY (YOU’LL BE SORRY) (L.Armstrong) 4’30

20. TIGER RAG (D.J.LaRocca) 3’27

“LEADERS’ ORCHESTRA” (A Song Is Born : A Samuel Goldwyn – RKO Film)

Louis ARMSTRONG (tp, voc) ; Tommy DORSEY (tb) ; Benny GOODMAN (cl) ; Charlie BARNET (ts) ; Lionel HAMPTON (vibes) ; Mel POWELL (p) ; Al HENDRICKSON (g) ; Harry BABASIN (b) ; Louis BELLSON (dm). Hollywood, Août

/August 1947.

21. GOLDWYN STOMP (D.Raye-G.DePaul) (Acetate) 1’26

22. A SONG WAS BORN (version I) (D.Raye-G.DePaul) (WOR Transcription 3177-B) 4’13

DISQUE / DISC 3

“LEADERS’ ORCHESTRA” (A Song Is Born : A Samuel Goldwyn – RKO Film)

Louis ARMSTRONG (tp, voc) ; Tommy DORSEY (tb) ; Benny GOODMAN (cl) ; Charlie BARNET (ts) ; Lionel HAMPTON (vibes) ; Mel POWELL (p) ; Al HENDRICKSON (g) ; Harry BABASIN (b) ; Louis BELLSON (dm) ; Jeri SULLIVAN, The GOLDEN GATE QUARTET (voc). Hollywood, Août/August 1947.

1. A SONG WAS BORN (version II) (D.Raye-G.DePaul) (Victor NB-6013 / mx.M-233) 4’52

LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND THE ALL-STARS (concert)

Louis ARMSTRONG (tp, voc) ; Jack TEAGARDEN (tb) ; A. Barney BIGARD (cl) ; Dick CARY (p) ; Arvell SHAW (b) ; Sidney CATLETT (dm) ; Velma MIDDLETON (voc). Boston (“Symphony Hall”), 30/11/1947.

2. MUSKRAT RAMBLE (Ed. Ory) (Decca DL 8037 / mx.80352/80353) 6’13

3. BLACK AND BLUE (T.W.Waller-A.Razaf) (Decca DL 8037 / mx.80354/80355) 4’12

4. ROYAL GARDEN BLUES (C. & Sp.Williams) (Decca DL 8037 / mx.80356/80357) 5’00

5. STARS FELL ON ALABAMA (Perkins-Parish) (Decca DL 8037 / mx.80359/80360) 5’16

6. I CRIED FOR YOU (A.Lyman-G.Arnheim-A.Freed) (Decca DL 8038 / mx.80361/80362) 4’33

7. SINCE I FELL FOR YOU (Johnson) (Decca DL 8038 / mx.80363) 4’04

8. TEA FOR TWO (V.Youmans-I.Caesar) (Decca DL 8038 / mx.80365/80366) 4’42

9. BODY AND SOUL (Green-Sour-Heyman-Eyton) (Decca DL 8038 /mx.80367/80368) 5’30

10. MAHOGANY HALL STOMP (Sp.Williams) (Decca DL 8038 / mx.80371) 3’51

11. STEAK FACE (Trad.) (Decca DL 8038 / mx.80369/80370) 7’09

12. ON THE SUNNY SIDE OF THE STREET (J.McHugh-D.Fields) (Decca DL 8038 / mx.80372/80373) 6’47

13. HIGH SOCIETY (P.Steele) (Decca DL 8038 / mx.80374) 3’28

14. THAT’S MY DESIRE (H.Kresa-L.Loveday) (Decca DL 8038 / mx.80376/80377) 4’42

15. BABY WON’T YOU PLEASE COME HOME

(C.Williams-C.Warfield) (Decca DL 8037 / mx.80375) 2’47

16. BOFF BOFF (MOP MOP) (C.Hawkins) (Decca DL 8037 / mx.80381/80382) 5’07

Remerciements

Philippe Baudin, Jean-Pierre Daubresse, Irakli de Davrichewi, Alain Délot, Yvonne Derudder, Jean Duroux, Pierre Lafargue, Clément Portais.

« On peut sans crainte affirmer que parmi les plus incontestables artistes qu’ait produit le vingtième siècle, seul Charles Chaplin fut aussi universellement reconnu que Louis Armstrong. »

Dan MORGENSTERN, Directeur de l’Institut des Jazz Studies, Rutgers University

“It is safe to say that among performing artists of the 20th century, only Charlie Chaplin was as universally recognized as Louis Armstrong.”

Dan MORGENSTERN, Director, Institute of Jazz Studies, Rutgers University

CD The complete Louis Armstrong Intégrale Louis Armstrong vol. 13 "A song was born" 1947 © Frémeaux & Associés 2014