- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

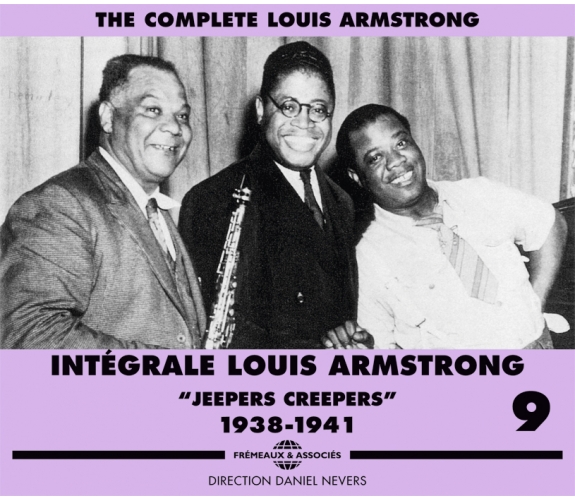

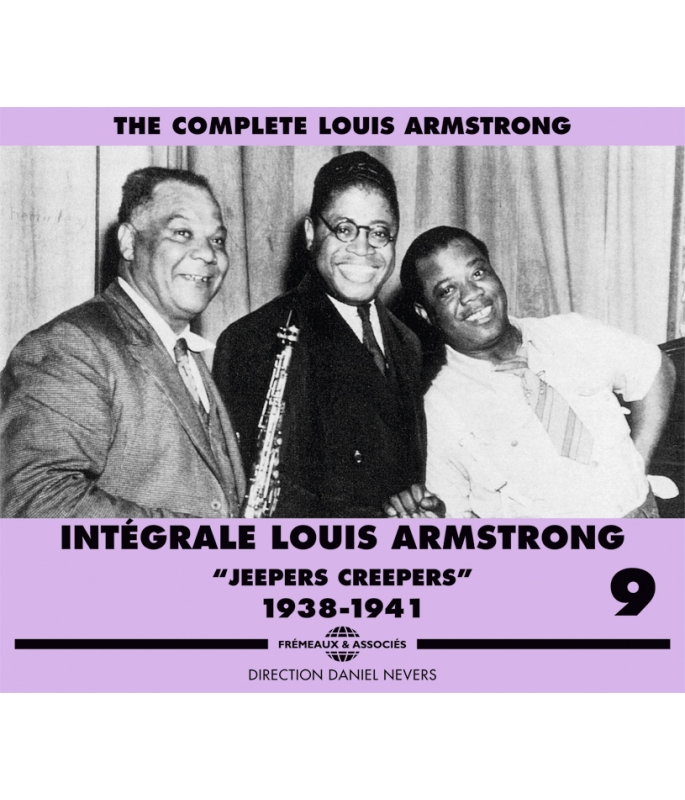

JEEPERS CREEPERS - 1938-1941

Ref.: FA1359

Artistic Direction : DANIEL NEVERS

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Total duration of the pack : 3 hours 29 minutes

Nbre. CD : 3

JEEPERS CREEPERS - 1938-1941

JEEPERS CREEPERS - 1938-1941

“As changing and colourful as life itself, the artistry of Louis Armstrong goes straight to the heart in its audacity and truthfulness (…) His dynamic lyricism, that of a genius, sends us far back into ourselves to where great mysteries are formed, mysteries of flame and passion.” Carlos de RADZITZKY

The Frémeaux & Associés Complete Series usually feature all the original and available phonographic recordings and the majority of existing radio documents for a comprehensive portrayal of the artist. The Louis Armstrong series is an exception to the rule in that the selection of titles by this American wizard is certainly the most complete as published to this day but does not comprise all his recorded works. Patrick FREMEAUX

WITH FATS DOMINO, JOHN KIRBY, LOUIS JORDAN, T BONE...

PUBLIC MELODY N°1 - 1937-1938

ARETHA FRANKLIN • CAMILLE HOWARD • SHIRLEY HORN •...

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Swing That MusicArmstrong Louis00:02:341938

-

2Twelfth Street RagArmstrong Louis00:02:011938

-

3The Flat Foot FloogieArmstrong Louis00:02:141938

-

4Jeepers Creepers (1)Armstrong Louis00:02:011938

-

5Mutiny In the NurseryArmstrong Louis00:06:041938

-

6Jeepers Creepers (2)Armstrong Louis00:02:271938

-

7Say It With a KissArmstrong Louis00:01:291938

-

8Honeysuckle RoseArmstrong Louis00:01:191938

-

9On the Sunny Side of the StreetArmstrong Louis00:05:211938

-

10Tiger RagArmstrong Louis00:04:331938

-

11Jeepers CreepersArmstrong Louis00:02:471938

-

12I'Ve Got RhythmArmstrong Louis00:03:561938

-

13BluesArmstrong Louis00:04:161938

-

14ShadrackArmstrong Louis00:03:061938

-

15Nobody Knows the Trouble I Ve SeenArmstrong Louis00:03:441938

-

16Jeepers CreepersArmstrong Louis00:02:411939

-

17What Is This Thing Called SwingArmstrong Louis00:03:071939

-

18Rockin ChairArmstrong Louis00:03:171939

-

19Lazy BonesArmstrong Louis00:03:161939

-

20Heah Me Talkin to YaArmstrong Louis00:03:061939

-

21Save It Pretty MamaArmstrong Louis00:02:591939

-

22West End BluesArmstrong Louis00:03:121939

-

23Savoy BluesArmstrong Louis00:03:121939

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1ConfessinArmstrong Louis00:03:151939

-

2Our Monday DateArmstrong Louis00:02:291939

-

3If It S Good Then I Want ItArmstrong Louis00:02:361939

-

4Me And Brother BillArmstrong Louis00:02:451939

-

5Happy Birthday to BingArmstrong Louis00:02:031939

-

6Baby Won T You Please Come HomeArmstrong Louis00:03:181939

-

7Poor Old Joe (Version 1)Armstrong Louis00:02:581939

-

8Shanty Boat On the MississippiArmstrong Louis00:03:221939

-

9Theme Old Man MoseArmstrong Louis00:03:271939

-

10What Is This Thing Called SwingArmstrong Louis00:05:081939

-

11Ain T MisbehavinArmstrong Louis00:02:331939

-

12Poor Old Joe (Version 2)Armstrong Louis00:03:041939

-

13You're a Lucky GuyArmstrong Louis00:03:181939

-

14You're Just a No AccountArmstrong Louis00:02:541939

-

15Bye And ByeArmstrong Louis00:02:341939

-

16Harlem StompArmstrong Louis00:02:441939

-

17Hep Cat's BallArmstrong Louis00:03:181940

-

18You' ve Got Me Voodoo DArmstrong Louis00:02:581940

-

19Harlem StompArmstrong Louis00:03:011940

-

20Wolverine BluesArmstrong Louis00:03:181940

-

21Lazy Sippi SteamerArmstrong Louis00:03:181940

-

22W P AArmstrong Louis00:02:471940

-

23Boog ItArmstrong Louis00:02:341940

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1CherryArmstrong Louis00:02:481940

-

2MarieArmstrong Louis00:02:211940

-

3Sweethearts On ParadeArmstrong Louis00:02:521940

-

4You Run Your Mouth I Ll Run My BusinessArmstrong Louis00:03:011940

-

5Cut Off My Legs And Call Me ShortyArmstrong Louis00:02:321940

-

6Cain And AbelArmstrong Louis00:03:011940

-

7Perdido Street BluesArmstrong Louis00:03:021940

-

82:19 BluesArmstrong Louis00:02:511940

-

9Down In Honky Town (Tk A)Armstrong Louis00:03:041940

-

10Down In Honky Town (Tk B)Armstrong Louis00:03:041940

-

11Coal Cart BluesArmstrong Louis00:02:561940

-

12Everything's Been Done BeforeArmstrong Louis00:03:061941

-

13I Cover the WaterfrontArmstrong Louis00:03:141941

-

14In the GloamingArmstrong Louis00:03:001941

-

15Long Long AgoArmstrong Louis00:02:541941

-

16Hey Lawdy MamaArmstrong Louis00:03:011941

-

17I'l Get Mine Bye And ByeArmstrong Louis00:03:061941

-

18Do You Call That A BuddyArmstrong Louis00:03:201941

-

19Yes SuhArmstrong Louis00:02:211941

-

20Basin Street BluesArmstrong Louis00:03:231941

-

21Leap FrogArmstrong Louis00:03:511941

-

22Exactly Like YouArmstrong Louis00:03:581941

LOUIS ARMSTRONG - Volume 9

INTÉGRALE LOUIS ARMSTRONG

“JEEPERS CREEPERS” 1938-1941

DIRECTION DANIEL NEVERS

Après l’importante parenthèse européenne (été 1933 - début 1935) et son épuisante succession de tournées, la reprise, à l’heure du retour au pays, ne fut pas si facile pour Louis Armstrong. Joe Glaser, son nouvel impresario, tout aussi mêlé que ses prédécesseurs aux trafics des gangs mais plus subtil malgré une brutalité affichée, sut le prendre mieux en main et lui imposa, durant la plus grande partie de l’an 35, un repos salvateur. Il l’incita à adopter une technique moins fatigante, lui fit soigner des lèvres terriblement abîmées, lui trouva au début des engagements assez tranquilles, lui dénicha de gentilles panouilles dans quelques films à succès (Pennies From Heaven, Everyday’s a Holiday…), sans oublier de lui faire signer un contrat d’enregistrement de longue haleine avec la très jeune, très britannique, très agressive maison Decca (à l’effigie de Ludwig van Beethoven dirigeant une de ses œuvres débutant par ré-mi-do-do-la), récemment implantée aux USA et déjà en train de grignoter férocement le territoire des vénérables vieilles boîtes malmenées par la Crise…

Côté lèvres, les choses iront s’améliorant peu à peu, mais Louis connaîtra toujours, tout au long de sa carrière, de permanentes et douloureuses épreuves. Quant à la vitesse de croisière, elle sera atteinte en 1937, grâce à un beau contrat radiophonique avec un puissant fabricant de farine et de levure, sponsor d’une série de transmissions hebdomadaires en direct sur les antennes de la NBC : première fois sans doute qu’un artiste noir devenait ainsi le Maître de Cérémonies d’émissions lourdes programmées sur l’un des deux réseaux les plus importants du pays. Louis en fut tout à fait conscient, qui considéra cette date comme capitale dans le déroulement de sa carrière. La chose, aussi harassante soient-elle, aurait aussi bien pu durer des années. Malheureusement, Louis ne fit danser qu’un seul printemps ! Dès l’été 37, l’animateur titulaire, le crooner Rudy Vallée, récupéra son poste et Armstrong ne fut plus que l’un de ses invités parmi d’autres – comme avant. Tout cela se déroulant en direct, on pensait ces prestations à jamais évanouies dans l’azur. Néanmoins, la firme enregistrait parfois, sur laques, des témoins “en simultané”. Quelques uns, miraculeusement retrouvés, ont été repris dans les volumes 7 et 8 (Frémeaux FA-1357 & 1358)…

Ensuite, le trompettiste retrouva une sorte de routine alternant prestations en public, travail de radio, tournages hollywoodiens, enregistrements pour le commerce chez Decca… De ces derniers, nous avons fourni l’intégralité pour l’année 1938 dans le précédent recueil, les deux rares sermons du 11 août sortis en 78 tours 30 centimètres inclus. Il restait cependant à reprendre quelques extraits de radio, parfois d’une indéniable importance, et des fragments de films réalisés au cours de cette année-là. Ce sont eux que l’on découvre dans la première partie du CD 1, de juin à décembre 38. A propos de cinéma, il existe cette année-là chez Paramount, un Doctor Rhythm de quatre-vingts minutes, dirigé par Frank Tuttle, offrant la vedette à Beatrice Lillie et Bing Crosby et permettant, dit-on, d’entendre Louis Armstrong interpréter The Trumpet Player’s Lament. Aucune copie n’a pu être visionnée, mais il semble bien que la séquence en question fut purement et simplement coupée au montage… On se contentera donc de la version disque et aussi de cette photo de plateau donnant à voir Bing (en flic !) et Satch’ trompette en main, devisant gaiement. Cette pratique consistant à en tourner plus qu’il n’en faut puis à supprimer des scènes entières à l’arrivée afin de reserrer l’action, était depuis belle lurette monnaie courante dans les studios d’Hollywood et d’ailleurs. On en trouvera ici un autre exemple : le bref Say It with a Kiss que chantent, accompagnés par Louis, Maxine Sullivan et Dick Powell dans Going Places, toujours millésimé 1938. Plus guère de traces dans les copies connues. Mais ce coup-ci, au moins, le son a survécu, ce qui nous permet de le restituer ici… Armstrong en verra d’autres, notamment avec le premier Minelli, Cabin in the Sky.

Ray Enright fut probablement un director supérieur à Frank Tuttle (encore que, Alan Ladd en tueur à gages amoureux des chats et de Veronika Lake)… Longtemps attaché au studio de la famille Warner, il s’illustra surtout dans la réalisation de westerns et de polars, mais donna aussi quelques musicals avant la guerre, dont le célèbre Dames (1934), avec Ruby Keeler (Madame Al Jolson à la ville), Dick Powell, son épouse Joan Blondell et les délirants ballets de Busby Berkeley. Going Places (tourné en septembre 38), malgré cette fois encore la présence de la jolie voix du gentil et joufflu Powell, ne connut pas le même retentissement. Le scénario faisant intervenir deux turfistes abrutis et un faux jockey bien décidé à passer pour un vrai par amour, ne vole pas très haut. Mais il y a ce cheval farouche qui n’obéit qu’à Louis Armstrong lorsque celui-ci lui joue et lui chante amoureusement Jeepers Creepers (“where d’you get those eyes ?”), spécialement conçu à son intention ; et puis il y a Louis Armstrong déguisé en garçon d’écurie (comme il se doit) qui joue et chante Jeepers Creepers ; il y a aussi Maxine Sullivan (habillée en boniche, bien entendu) qui intervient joliment avec pas mal d’autres (dont Louis) dans un assez long numéro intitulé Mutiny in the Nursery, ainsi que sur Say It with a Kiss déjà mentionné. On peut entendre également une version hippique et instrumentale de Jeepers Creepers, censée stimuler le dada pendant la course finale (que, bien évidemment, il gagnera)… De quoi, tout de même, ne pas trop faire la fine bouche ! Le film sortit en fin d’année et, avec lui, l’intermède cinéma fut provisoirement clos pour Satchmo. Il lui faudra attendre le Minelli de 1942 cité plus haut pour reprendre contact et, on l’a dit, voir la plupart de ses interventions tronçonnées au montage ! L’année d’après, Louis retrouvera néanmoins par deux fois sa partenaire de Going Places, Maxine Sullivan (mais pas Jeepers Creepers) : d’abord, du 19 octobre 39 au 5 avril 40, dans ce qui devait être l’ultime revue du Cotton Club – la seule occasion, d’ailleurs, qu’il eut de se produire en ce lieu légendaire… La version radio de Harlem Stomp (18 décembre 39 – CD 2, plage 19) est l’unique témoignage de cet engagement tardif. Entretemps, en novembre 1939, tous deux participeront, au Rockefeller Center de New York, à l’adaptation jazz du Songe d’une Nuit d’Été (rebaptisé pour la circonstance Swingin’ the Dream). D’autres musiciens connus (Benny Goodman, Lionel Hampton, “Bud” Freeman) seront de la partie. L’aventure ne tiendra l’affiche que onze jours et nous n’en possédons pas le moindre écho. Louis, costumé en pompier dans le rôle de Bottom, n’y jouait dit-on qu’assez peu de trompette…

Côté radio, une émission surtout mérite le détour : celle proposée sur les antennes de CBS le 12 décembre 1938 par l’alors très prisé Martin Block, ancêtre des disc-jockeys, à qui Hampton dédiera plus tard son Martin on Every Block. Ce jour d’automne à New York, il avait décidé que c’était le printemps et avait convoqué, invité, un joyeux soleil histoire de tromper l’ennui et l’ennemi. Les éblouissants rayons avaient noms Jack Teagarden, “Bud” Freeman, “Fats” Waller, Al Casey, “Slick” Jones et, bien évidemment, Louis Armstrong. Un sextette de rêve, encore que les discographes ne soient pas tous d’accord sur l’identité du percussionniste : d’aucuns préfèrent au batteur régulier de “Fats” le Chicagoan George Wettling (avec qui Louis jouait de temps en temps à l’époque), et quelques autres citent même Zutty Singleton – ce qui, si c’est bien lui, marquerait le début des retrouvailles (brèves) des deux vieux complices de la seconde moitié des années 1920… Compositeur réputé, “Fats” avait certes déjà écrit en 1929 la partition de la revue Hot Chocolates (où figuraient Ain’t Misbehavin’ et Black and Blue), dont Armstrong fut la vedette, mais ces deux Grands n’eurent jamais l’occasion d’enregistrer “commercialement” ensemble, ce qui rend ces témoignages radiophoniques postérieurs de près de dix ans d’autant plus précieux, même si le pianiste d’ordinaire si bondissant s’y montre presque parcimonieux. Louis et Big Tea feront en revanche un bon bout de chemin ensemble une dizaine d’années plus tard. Pour l’heure, le tromboniste n’allait plus tarder à abandonner la grosse machine de Paul Whiteman afin de fonder sa propre formation. D’aucuns estiment qu’il est le musicien le plus en forme de cette jam-session du 12 décembre 38… A propos de Whiteman, “Roi du Jazz” des années 1920-30 en sérieuse perte de vitesse, c’est tout de même à lui que revint l’honneur d’animer la soirée de Noël, le 25 décembre, dans l’enceinte du légendaire Carnegie Hall, l’un des hauts lieux de la vie musicale new-yorkaise. Invité d’honneur, Louis ne pouvait faire moins, en cette sainte occasion, que d’interpréter deux de ces Spirituals qu’il avait gravés le 14 juin de cette année-là et qui avaient remporté un beau succès. Ces versions “live” de Shadrack et de Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen mettent un point final aux aventures armstrongiennes pour l’an 1938.

Comme Il fallait s’y attendre, 1939 succéda le plus logiquement du monde à 1938. Une année particulièrement dure à plus d’un titre côté européen… Pour Armstrong, 39 verra les tournées épuisantes (Baltimore, Kansas City, Buffalo, Chicago, Indianapolis, Atlanta, Madison, Miami, Columbia, Cleveland…) alterner avec des engagements new-yorkais déjà signalés (Cotton Club, Rockfeller Center…) largement aussi fatigants. On ne possède que fort peu de témoignages de tout cela, à part le Harlem Stomp du Cotton Club déjà mentionné, des fragments du concert donné à Carnegie Hall le 6 octobre 39, au bénéfice de l’ASCAP (Old Man Mose, What Is This Thing Called Swing ?) et, le même mois, un petit bout de radio (Ain’t Misbahavin’) avec l’équipe de Benny Goodman… Même remarque pour l’an 40, avec nouvelles tournées à Chicago, en Iowa, en Alabama, en Californie, en Floride, au Mississippi, alternant là encore avec prestations au cœur de la Grosse Pomme… Pas la moindre radio rescapée. Quant au cinéma, on l’a dit, il marque un temps d’arrêt… Bref, il ne nous reste guère que les galettes de la maison Decca…

On y trouvera encore ces mélanges d’artistes sous contrat auxquels aimait alors à se livrer la firme. Moins toutefois que les années précédentes, puisque cette fois, on ne subira plus guère que le “chant cornichon” (Panassié dixit) des Mills Brothers sur leurs quatre ultimes gravures en la compagnie de Satchmo (10 & 11 avril 40) : W.P.A., Boog It, Cherry et Marie. Gentilles réussites, surtout Cherry, même si W.P.A., censuré, fut rapidement retiré du commerce pour cause de coquinerie ! Sacré Libre Amérique, va !… On y trouvera aussi, comme il se doit, les nouveautés promises à l’oubli et pas mal d’autres méritant davantage que l’on s’y arrête : Jeepers Creepers (version phonographe), le charmant et émouvant You’re a Lucky Guy, You’re Just a no Account, Bye and Bye, Harlem Stomp, Lazy ‘Sippi Steamer, Hep Cat’s Ball, Wolverine Blues (composition déjà ancienne de Jelly Roll Morton qu’il grave là pour la première fois, en se taillant quatre-vingts mesures parfaitement inspirées) et aussi, bien entendu, ce chef-d’œuvre intitulé Caïn and Abel, étoilé d’un solo magnifique. Le titre suggère évidemment une parenté biblique avec les Spirituals de l’an 38, mais c’est surtout là une sorte de clin d’œil destiné à faire mousser producteurs et compositeurs à l’affût ! Un des très beaux disques de Louis Armstrong, en tous cas – l’un des meilleurs de la longue suite Decca (1935-1945)… Au rayon des machins plus ou moins drôles dont Louis s’était aussi fait une spécialité, on relève, dans la lignée de l’antique You, Rascal You, les fort oubliés sans trop de regrets If It’s Good, You’ll Run Your Mouth, I’ll Run My Business et Cut Off my Leggs and Call Me Shorty, ainsi que le délicieusement lourdingue Me and Brother Bill, œuvre de Satch lui-même (uniquement chanté, sans solo de piston), appelée à connaître une certaine longévité… Côté curiosités, signalons le Happy Birthday to Bing, gravé en quenouille en fin de séance, le 25 avril 39, juste à temps pour que le dédicataire puisse recevoir son disque-cadeau le 2 mai, jour de son trente-sixième printemps… Louis avait, dit-on, décidé d’offrir un disque de ce genre à ses partenaires de cinéma. Mae West, Dick Powell, Jack Benny en reçurent-ils un ? En tous cas, seul celui destiné à Bing Crosby nous est parvenu…

Toutefois, l’une des idées (géniales ?) des directeurs de chez Decca en 1939-40, fut de faire réenregistrer à Louis, parallèlement aux nouveautés, quelques uns de ses plus incontestables succès de la période OkeH (1925-1932) – c’est-à-dire, quelques unes de ses meilleures ventes… Certains biographes, peu versés dans les arcanes de l’art subtil de la discographie, ont affirmé que les disques de la marque OkeH étaient épuisés à la fin des années 1930, et qu’il n’était possible de les acquérir que d’occasion. Exact. De toute façon, précisent-ils encore, leur “style daté” en interdisait l’éventuelle réédition. Faux. Dans la seconde moitié de ces ambiguës années 30, près des deux tiers de la production armstrongienne pour la firme en question restaient parfaitement disponibles… mais sous d’autres étiquettes (Vocalion, Columbia) récupérées par l’American Recording Corporation. Après le rachat de l’ARC par CBS fin 1938, George Avakian, en charge du fond de catalogue et de la production d’albums, se plut même à faire paraître, cette fois sous label Columbia (série “Masterworks” rouge), nombre d’inédits dont on a déjà parlé. Quant à l’Europe, elle continuait à distribuer bravement sous étiquettes Parlophone et Odéon la plupart des matrices OkeH des années 1928-32…

En 1938 déjà, Louis, toujours accompagné par diverses grandes formations, avait “refait” Struttin’ With Some Barbecue, I Can’t Give You Anything But Love et Ain’t Misbehavin’. Ce fut ensuite le cas avec Rockin’ Chair et Lazy Bones du 20 février 39, ainsi que pour les six titres des 5 et 25 avril : Heah Me Talkin’ To Ya, Save It Pretty Mama, West End Blues, Savoy Blues, Confessin’ et Our Monday Date, alors que les versions originales de cinq de ces pièces avaient été gravées en petits comités. Certes, il s’agissait de moderniser les thèmes en question en les habillant à la mode du moment, c’est-à-dire celle du big band swing. L’orchestre, au demeurant, est loin d’être mauvais et les habituels préposés aux solos, notamment Charlie Holmes et J.C. Higginbotham, se révèlent plutôt en forme, de même que Sidney Catlett, remplaçant plus souple de Paul Barbarin à la batterie. Pourtant, l’étincelle n’est pas toujours au rendez-vous, ainsi que le note Panassié : “Dans les vieux disques, Louis était entouré de musiciens qui le comprenaient parfaitement, qui sentaient comme lui, jouaient dans le même style, principalement Earl Hines et Zutty, et une véritable inspiration collective soufflait sur le petit groupe. Dans les disques Decca, l’orchestre ne fait pas bloc avec le chef”… Le trompettiste ne reprend réellement ses anciens chorus que sur West End Blues et Savoy Blues (peut-être le plus réussi de la série) ; pour les autres titres, il joue le jeu et tente de mettre au point un autre type de musique. Pari gagné avec la superbe nouvelle version de Our Monday Date… En outre, bien qu’il n’ait point enregistré des choses comme Baby Won’t You Please Come Home ou Wolverine Blues à l’époque OkeH, Armstrong dut parfois les interpréter en public dans les années 1920, quand ces airs étaient à la mode. Leur inclusion parmi les “refaits” de 1939-40 se conçoit donc fort bien. Quant à Poor Old Joe, dont on possède deux versions (la première, du 15 juin 39, uniquement sortie en Argentine !), Fletcher Henderson l’avait enregistré dès le printemps de 1932. S’agit-il, de la part de Satchmo, d’un petit coup de chapeau ému à son vieux Maître, Joe “King” Oliver, disparu l’année d’avant sans avoir pu revoir New York, Chicago ou sa Nouvelle Orléans ?

Donc, en ce temps-là – les années 1930 et le début de la décennie suivante – le big band tenait le haut du pavé. L’Âge d’Or, en somme. Mais, en application réglementaire de la bonne vieille dialectique chère aux philosophes chers à Patrick Frémeaux, un retournement de situation se profilait. Les groupes dits “petits” (en gros, du trio au septette) regagnaient du terrain. Le mouvement revivaliste, inauguré vers 1935-36 (juste au moment où Benny Goodman se faisait couronner “Roi du Swing”), n’y fut certainement pas pour rien… Les pionniers de l’Original Dixieland Jazz Band réunis vingt ans après, avaient suscité cette soif de retour aux sources. Dans la foulée, les superbes concerts de John Hammond, From Spiritual to Swing donnés à Carnegie Hall fin 38 et 39, les disques de Tommy Ladnier réalisés par Hugues Panassié pour la jeune marque française “Swing” (soit dit en passant, le vrai premier label consacré à l’enregistrement exclusif du jazz sous toutes ses formes, avant Commodore, H.R.S., Blue Note ou Signature), les premières gravures de Sidney Bechet enfin publiées sous son nom, puis, à partir de 1939-40, les tentatives pour retrouver dans le Sud les ancêtres comme Bunk Johnson et les remettre en selle, lancèrent durablement cette nouvelle quête de l’ancien. Or, presque tous les groupes pratiquant ce type de musique étaient de petits comités. Chez Decca, dans le contexte de ce “New Orleans Revival” naissant, on envisagea de faire graver à Armstrong et à Bechet, réunis après quinze ans, quatre titres illustrant cette tendance : Perdido Street Blues, 2:19 Blues, Down in Honky Tonk et Coal Cart Blues. Ce dernier morceau, Louis l’avait déjà enregistré début octobre 1925 chez OkeH, à New York, au sein des Blue Five de Clarence Williams (voir volume 3 : FA-1353). Mais à ce moment-là Sidney, membre de l’orchestre de la future légendaire Revue Nègre, cinglait déjà vers l’Europe et n’avait pu être de la séance. Lui, Bechet (probablement l’aîné de Louis d’une petite dizaine d’ans), il avait, pour le compte de Monsieur Williams, participé au côté du trompettiste à ces magnifiques sessions de l’automne/hiver 24 et du printemps 25, que l’on trouvera aux volumes 1 et 2 (FA-1351 &1352). Perdido Street Blues, composition de Louis, aurait dû être enregistré par lui et ses Hot Five dès juillet 1926, mais sous un nom d’emprunt, car la séance était organisée chez Columbia. Il préféra finalement se faire remplacer par l’émouvant George Mitchell (voir le recueil Chicago South Side – Frémeaux FA-5031)… Down in Honky Tonk (deux “prises” connues) semble avoir été retenu pour la circonstance et 2:19 Blues est la même histoire poignante, à base de trains fantômes, de femme perdue, d’amant infidèle, que Jelly Roll Morton enregistra lui aussi, en décembre 39, sous le titre Mamie’s Blues. Le plus beau disque du crépuscule d’un dieu du jazz…

Outre Louis et Sidney, Stephen Smith et Charles Edward Smith, initiateurs de cette séance du chaud printemps 1940, avaient convoqué deux autres Néo-Orléanais, Wellman Braud à la basse et Zutty Singleton à la batterie. L’ensemble se trouva complété par le bon guitariste Bernard Addison et par Luis Russell, directeur musical du grand orchestre de Satchmo, au piano. Éditeur de Coal Cart Blues (que Louis avait déjà repris en big band en janvier 38 sous le titre Satchel Mouth Swing – voir volume 8 : FA-1358), Clarence Williams s’en était lui aussi venu faire un petit tour au studio Decca ce 27 mai, mais il ne joua pas. En revanche, il ne manqua point de se faire photographier entre les deux vedettes du jour. L’une de ces photos se trouve reproduite en première de couv. de ce livret, et l’on pourra constater que les trois compères sont tout sourire ! En réalité, les choses ne se passèrent sans doute pas aussi bien que l’on aimerait à croire. L’atmosphère fut, dit-on, tendue. Bechet affirme que le trompettiste, vilain jaloux, créa une ambiance de compétition peu favorable à l’éclosion d’une œuvre collective digne de ce nom. On sait qu’Armstrong n’aimait guère la concurrence. Le lyrique Bechet, bien que nettement moins connu que lui en ce temps-là, pouvait effectivement passer pour un sérieux rival. Toutefois, on sait aussi que Sidney – surnommé “Wild Cat”, le chat sauvage, sans doute à bon escient ! – n’était pas vraiment le doux pépère tranquille et souriant qu’il tentait de paraître dans les ultimes années – françaises – de son existence. En son jeune temps, il n’était pas le dernier à sortir le surin ou le 38 pour un oui ou pour un non ! Plus d’une fois il fut raccompagné à la frontière et tricard dans les pays d’où on l’expulsait de temps en temps (notamment la France)… On sait encore que lui non plus n’aimait pas trop la concurrence et avait la vilaine habitude de tirer, non seulement des coups de flingue à l’aube rue Lepic, mais aussi la couverture à lui (à vérifier, par exemple, dans les faces de 1932 et 1938 en compagnie de Tommy Ladnier, trop souvent réduit à la portion congrue)… Alors ? Match nul ?... Ce qui, au demeurant, n’empêche nullement les quatre faces de mai 40 (sorties sous le nom d’Armstrong) de compter parmi les plutôt belles des frères ennemis, surtout Perdido et le Blues ferroviaire de deux heures dix-neuf.

La reprise, bien que souvent fort honorable, des anciens succès n’ayant sans doute pas réalisé les ventes escomptées, l’entreprise fut abandonnée en 1941. En revanche, la formule du petit orchestre retrouvant une certaine faveur auprès du public, on continua à enregistrer Armstrong en formation réduite. Mais, contrairement au 27 mai 40, on ne chercha point à monter des groupes de studio spécifiques, se contentant d’emprunter au grand orchestre régulier quelques uns de ses membres : le tromboniste George Washington, le saxophoniste Prince Robinson, le guitariste Lawrence Lucie, le bassiste John Williams, Luis Russell et Sidney Catlett, afin de former comme par hasard un septette – les nouveaux Hot Seven, en somme… Huit faces en mars/avril 41, résultat plutôt mitigé : rien à voir avec les fabuleux Hot Seven originaux, ceux de mai 27 ! Pourtant, Everything’s Been Done Before, I Cover the Waterfront (au répertoire armstrongien dès 1933, mais jamais enregistré commercialement), Hey Lawdy Mama et Now Do You Call That a Buddy sont loin d’être sans qualités. A l’endroit du dernier cité, Panassié, qui le tient pour “un vrai chef- d’œuvre”, précise : “c’est l’un de ses disques les plus poignants”. Louis Armstrong n’enregistra pas beaucoup pour les disques du commerce en 1941, à cause là encore de ces longues et fatigantes tournées qui le menèrent jusqu’au Canada. Voilà pourquoi, du printemps, on saute à l’automne avec les trois dernières plages du CD 3. Il s’agit de fragments d’une radio datée d’octobre, recueillie sur laques par Jerry Newman, cet étudiant cinglé de jazz qui n’hésitait pas à trimbaler son lourd et fragile matériel d’enregistrement dans ces boîtes où s’élaborait la musique de demain : chez Minton’s, chez Clark Monroe’s… Mais il ne détestait pas, Newman, les grands aînés. Ici, l’état de l’original est tout bonnement épouvantable, malgré le traitement de choc que lui a fait subir François Terrazzoni. Sachez bien qu’avant, on n’entendait à peu près rien. Même pas l’ambiance. C’est dire !

Daniel NEVERS

© 2011 Frémeaux & Associés – Groupe Frémeaux Colombini

Remerciements : Jean-Christophe AVERTY, Philippe BAUDOIN, Olivier BRARD,Jean-Pierre DAUBRESSE, Irakli de DAVRICHEWI, Alain DELOT, Yvonne DERUDDER, Jean DUROUX, Pierre LAFARGUE, Clément PORTAIS, Gérard ROIG, Jean-Jacques STAUB.

english notes

LOUIS ARMSTRONG - Volume 9

After a lengthy European episode (summer 1933 to early 1935) involving one exhausting tour after another, Louis Armstrong’s return home to America wasn’t exactly easy. Joe Glaser, his new impresario – he was just as involved with the Mob as his predecessors, but more subtle beneath his rough veneer – had a better way with him and, for most of 1935, he succeeded in making Armstrong take time to recover. Glaser made Louis change his technique to make playing less tiring, and took care of his badly-damaged lips; he also found him the odd bit-part in a few box-office hits like Pennies From Heaven and Everyday’s a Holiday... but didn’t forget to have him put his name to a long-term record-contract with the very young, very British – and aggressive – label Decca, which had recently set up shop in the USA and was already chewing its way into territory that had until then been the preserve of venerable old companies now in the throes of the Depression. As for those lips, they were slowly getting better; but for the rest of his career, Louis wouldn’t be spared some permanent and painful trials. He found his cruising-speed again in 1937, when a nice radio-contract appeared in the hands of a powerful company whose specialities were flour and yeast; it sponsored a series of weekly live broadcasts on NBC, and it was probably the first time a black artist had ever been the MC of a blockbuster radio show aired by one of the two biggest networks in the country. Armstrong was well aware of its importance, and always said it was one of the capital events of his career; however harassing it may have been, it might have lasted for years if Louis hadn’t put an end to making people dance after only one (spring) season! By the summer of ‘37, the regular host, crooner Rudy Vallee, got his job back, and Armstrong was merely just another guest on the show – again. Because those shows all went out «live», it was thought that all traces of them had disappeared into thin air as well, but... as a matter of fact, some of them were recorded «simultaneously» by NBC on shellac, and some of those, miraculously recovered, appear in Vols. 7 & 8 (FA-1357 & 1358)…

The trumpeter then found a routine: his public appearances alternated with radio work, filming in Hollywood and commercial recordings for Decca… Of the latter, everything he did in 1938 appears in our preceding volume, including the two rare sermons pronounced on August 11th and released on 12” 78s. There remain the radio excerpts, however, some of them undeniably of major importance, and also fragments of films made that year: these can be discovered in the first part of CD 1 here, which deals with the period June-December 1938.

On the subject of films: in 1938 Paramount had a Doctor Rhythm lasting some eighty minutes which was directed by Frank Tuttle: it featured Beatrice Lillie and Bing Crosby and, it’s said, gave people a chance to hear Louis Armstrong playing The Trumpet Player’s Lament. We couldn’t obtain a copy of it, but apparently the Armstrong-sequence was simply cut from the film during the editing... and so we’ll have to make do with this record-version – and also the still that shows Bing on the set (dressed as a cop!) with Louis looking on genially while clutching his horn. That practice of shooting more than was needed in a film before slicing out whole scenes to speed up the action had been the Hollywood norm for ages (and also elsewhere). There’s another example here: the brief Say It with a Kiss where Louis accompanies singers Maxine Sullivan (and actor Dick Powell) in the film Going Places, another 1938 effort. There’s no trace of that song either in the copies known to exist. But this time, at least, the sound has survived, thanks to which you can hear it now... Armstrong would have to get used to it, because it happened again in his first Minnelli film, Cabin in the Sky.

Ray Enright was probably a better director than Frank Tuttle (although there was that one with Alan Ladd as a hired gun who loved cats and Veronica Lake…). For a long time Enright was under contract to Warner, making his name in westerns and thrillers, but he also directed some musicals pre-War, including his famous Dames (1934), with Ruby Keeler (Mrs Al Jolson when she wasn’t working), Dick Powell and his wife Joan Blondell, and some delirious numbers created by Busby Berkeley. Going Places was filmed that September, but despite the presence of the genteel, chubby-cheeked Dick Powell (and his nice voice) it didn’t have the same impact. The screenplay wasn’t extraordinary either: two dumb race-goers and a false jockey determined to be a real jockey for the sake of love... But the film did have a wild horse which would only listen to Louis Armstrong when he lovingly played and sang Jeepers Creepers («Where d’you get those eyes?»), a role written especially for him in which he dressed (what else?) as a stable-lad. It also had Maxine Sullivan (a maid, of course) coming in with quite a few others (including Louis) to sing a lengthy number called Mutiny in the Nursery, as well as Say It with a Kiss. You can also hear a (horsey) instrumental version of Jeepers Creepers that’s supposed to urge the horse closer to the line in the final race (which the horse wins, as you might expect). You shouldn’t turn your nose up at stuff like this! The film was released at year-end, and it brought Satchmo’s film-work temporarily to a close. People had to wait until 1942 and the above Minnelli opus before he reappeared in a movie (only to see his efforts again compromised in the same old cutting-room as before). In 1939, however, Louis did meet up (twice) with his partner from Going Places, Maxine Sullivan (although there were no Jeepers Creepers). The first of those was between October 19th 1939 and April 5th 1940, in what was to be the very last Cotton Club revue (also the only time he had occasion to perform in such legendary surroundings), and the radio-version of Harlem Stomp (December 18th 1939, CD 2, track 19) is the only trace of that late booking. In November 1939, both Armstrong and Sullivan appeared at the Rockefeller Center in New York in the jazz version of A Midsummer Night’s Dream (rechristened Swingin’ the Dream for the occasion), which also featured musicians Benny Goodman, Lionel Hampton and Bud Freeman. The bill was only on the wall for eleven days, and we haven’t been able to find a single trace; according to rumour, Armstrong, dressed as a fireman in the role of Bottom, didn’t play much trumpet anyway...

If we take a look at his radio activities, one programme in particular deserves a special mention: the show that CBS put out on December 12th 1938 with front-man Martin Block, an ancestor of the disc-jockey and a man much-in-demand (Hampton would later dedicate his tune Martin on Every Block to him). It was late autumn in New York, and Block had decided it was spring: he invited sunshine into the studio to cheer everyone up, and he probably surprised quite a few when he brought in a beaming Jack Teagarden together with Bud Freeman, Fats Waller, Al Casey, Slick Jones and, naturally, Louis Armstrong. It was a dream sextet, although discographies disagree over the drummer: some prefer George Wettling (from Chicago) with whom Louis was playing from time to time in those days, whilst others name Zutty Singleton – which, if it was indeed he, would have marked the beginning of his (brief) reunion with an old accomplice from the late Twenties... As a renowned composer, «Fats» wrote the score for Hot Chocolates (1929), the revue featuring Ain’t Misbehavin’ and Black and Blue. Its star was Armstrong, but the two Greats never had the chance to make a «commercial» record together, which makes these radio-recordings (dating from a decade later) even more precious, even if the pianist – who usually bounced up and down the keyboard – shows himself to be almost parsimonious here. Louis and Big T, however, would go a long way together some ten years hence; in the interval, the trombonist jumped ship and left Paul Whiteman to create his own group. Some people say he’s the musician who comes off best in this jam-session organized by Block. While on the subject of Whiteman – «King of Jazz» in the Twenties but now seriously losing momentum – he was the bandleader who had the honour of pumping life into the proceedings at Carnegie Hall on Christmas Day 1938. As Guest of Honour, Louis could do no less, in this holy of holies, than perform two of the spirituals he’d recorded on June 14th that year, gospels that were very successful indeed: these live versions of Shadrack and Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen put the finishing touches to Armstrong’s 1938 adventures.

As people should have been expecting, 1939 followed 1938 in a very logical fashion. In Europe, the year was particularly tough in more ways than one... For Armstrong, 1939 brought some exhausting tours (Baltimore, Kansas City, Chicago, Atlanta, Miami, Cleveland and a half-dozen other cities…), interspersed with the above New York gigs (Cotton Club, Rockefeller Center) which were just as wearing. We have only a very few traces of these, apart from Harlem Stomp, already mentioned, the Carnegie Hall fragments from the ASCAP concert dated October 6th 1939 (Old Man Mose, What Is This Thing Called Swing?) and, from that same month, a radio-snippet (Ain’t Misbehavin’) with Benny Goodman’s crew... The same goes for 1940, when Louis visited Chicago, Alabama, California, Florida etc., and also played gigs in the Big Apple. Not a single air-shot anywhere. He was still on leave from Hollywood, too, so all we have left are the discs made for Decca... Those, of course, still show Decca’s penchant for putting various artists from their stable inside the same studio at the same time. There were fewer of those records than in previous years, however, just the «pickle-songs» (Panassié dixit) that the Mills Brothers sang on their four last sides accompanied by Satchmo (April 10th and 11th 1940): W.P.A., Boog It, Cherry and Marie. They were all a handsome success, especially Cherry, even if W.P.A., which was censored, was rapidly withdrawn from outlets because it was so rude... Talk about the Land of the Free! There were also new things, some destined for oblivion and (quite a few) others more worthy of a listening: Jeepers Creepers (its phonograph version), the charming (and moving) You’re a Lucky Guy, You’re Just a No-Account, Bye and Bye, Harlem Stomp, Lazy ‘Sippi Steamer, Hep Cat’s Ball, Wolverine Blues (an already-ancient composition by Jelly Roll Morton which Louis was now recording for the first time, cutting no fewer than eighty, magnificently-inspired bars in the process), and also, of course, this masterpiece called Cain and Abel, which earns a star for its magnificent solo. The title obviously suggests a biblical kinship with the spirituals recorded in 1938, but it is in fact merely a wink whose aim was to titillate any producers and composers who might have been on the lookout! It was a beautiful Louis Armstrong record in any event, one of his best in a long series of Decca sides made between 1935 and 1945.

In other departments featuring the more (or less) humorous merchandise of which Armstrong was so fond, there were these: similar to the ancient You Rascal, You came the quite forgotten – not to everyone’s sorrow – If It’s Good, You Run Your Mouth I’ll Run My Business and Cut off my legs and call me Shorty, plus the deliciously corny Me and Brother Bill, the work of Satch‘ alone – just his voice, no piston solo – and a piece which would enjoy a long life. Yet the top brass at Decca in the years 1939-40 did have some ideas – great ones? – including the notion of Louis returning to the studio to re-record some of the OKeh hits (1925-1932) that just never went away, all of them best-sellers for Louis at the time. Some biographers, admittedly not that well-versed in the arcana behind the subtle art of discography, have stated that OKeh no longer pressed any records after the end of the Thirties, and that it was only possible to acquire second-hand copies. True. Anyway, they went on to say, their «dated style» excluded any reissues. False. During the second half of those ambiguous Thirties, almost two-thirds of Armstrong’s entire output for OKeh remained easily available... but under different labels (Vocalion, Columbia) absorbed by the American Recording Corporation, ARC. When CBS bought out ARC at the end of 1938, George Avakian, who was in charge of the back-catalogue and album-production, even enjoyed issuing (this time with the Columbia label, in the red ‘Masterworks‘ series) a number of unreleased items. As for Europe, most of the OKeh masters from 1928-1932 were still bravely being distributed by labels carrying the Parlophone or Odeon flags.

Back in 1938 already, Louis, in the company of various big bands, had «redone» Struttin’ With Some Barbecue, I Can’t Give You Anything But Love and Ain’t Misbehavin’. He went back to Rockin’ Chair and Lazy Bones in the same vein (15 or 16 musicians) on February 20th 1939, and revisited another six titles on April 5th and 25th: Heah Me Talkin’ To Ya, Save It Pretty Mama, West End Blues, Savoy Blues, Confessin’ and Our Monday Date (five of the original versions had been recorded with small groups). Yes, there was the idea of modernising the tunes in question by having them wear fashionable clothes, i.e. «big band swing» fashion. The orchestra, by the way, was far from disreputable, and the musicians who were its regular soloists, notably Charlie Holmes and J.C. Higginbotham, turned out to be in fine fettle, as was Sidney Catlett, a much more flexible drummer than the man he replaced, Paul Barbarin. Yet the spark still wasn’t there: as critic Panassié noted, «On his old records, Louis was surrounded with musicians who understood him perfectly, who felt what he felt, and who played in the same style, mainly Earl Hines and Zutty, and there was a genuine, collective inspiration that blew over the small group. On his Decca records, the orchestra isn’t united behind the chief.» The trumpeter only really takes up his old choruses on West End Blues and Savoy Blues (perhaps the best one of the lot). As for the other titles, he plays along while trying to fine-tune a new type of music. And he found it, cf. the superb new version of Our Monday Date…

Another thing: although he hadn’t recorded pieces like Baby Won’t You Please Come Home or Wolverine Blues when he was with OKeh, Armstrong sometimes had to play them in public during the Twenties when they were in fashion. So there is nothing odd about including them here amongst these «revisits» from 1939-40. As for Poor Old Joe, of which we have two versions (the first, dated June 15th 1939, was released only in Argentina!), it had been recorded by Fletcher Henderson as early as the spring of 1932. Could this have been Satchmo doffing an emotional cap to his old master Joe ‘King’ Oliver, who’d passed away the previous year without seeing New York, Chicago or his native New Orleans again?

Throughout the Thirties and into the beginning of the next decade, big bands were ruling the roost. It was their Golden Age. But if you apply the rules of those good old dialectics so dear to the philosophers dear to Patrick Frémeaux, there was a turnaround on the horizon. The so-called «small groups» – for sake of argument, say from trio to septet – were gaining ground again, and the revivalist movement (inaugurated in around 1935-36, just when Benny Goodman was crowning himself «King of Swing») obviously played a hand. The pioneers of the Original Dixieland Jazz Band, reunited after twenty years, aroused a thirst for roots: in their wake came the superb From Spirituals to Swing concerts promoted by John Hammond at Carnegie Hall at the end of ‘38 and in ‘39; there were the records that Tommy Ladnier made for Hugues Panassié and the new French label called Swing (which, by the way, was really the first label devoted exclusively to recording jazz in all its forms, before Commodore, H.R.S., Blue Note or Signature); Sidney Bechet‘s first recordings were finally released under his own name; and then from 1939-40 there were attempts to find ancestors like Bunk Johnson in the Deep South and put them back in the saddle... All of which did much to make this new search for the ancient a durable proposition. It should be noted that almost all the groups playing this kind of music were «small groups».

At Decca, in this nascent New Orleans Revival context, they mooted the idea of getting Armstrong and Bechet together again – after fifteen years – to record four titles that illustrated this trend: Perdido Street Blues, 2:19 Blues, Down in Honky Tonk and Coal Cart Blues. Louis had already recorded that last piece for OKeh in October 1925 (with Clarence Williams’ Blue Five in New York, cf. Vol.3, FA-1353). But at that time, Sidney, a member of the orchestra with the soon-legendary Revue Nègre, was heading for Europe and couldn’t make it to the session. Bechet, who was probably Louis’ elder by ten years or so, had taken part in those magnificent sessions with the trumpeter (the studio was booked for Mr Clarence Williams) in autumn/winter 1924 and in spring 1925 which you can find in Vols. 1 & 2 (cf. FA-1351 & 1352). Perdido Street Blues, a composition by Louis, was due to have been recorded by Armstrong with his Hot Five as early as July 1926 (under a borrowed name due to the fact that the session was paid for by Columbia). Louis finally stood down and was replaced by a moving George Mitchell (cf. the Chicago South Side anthology, FA-5031). Down in Honky Tonk (there are two known takes) seems to have been retained due to the circumstances, and 2:19 Blues tells the same poignant story – ghost trains, a lost woman, an unfaithful lover – that Jelly Roll Morton recorded in turn (December ‘39) as Mamie’s Blues. It was the most beautiful record from the twilight years of a jazz god.

Apart from Louis and Sidney, Stephen Smith and Charles Edward Smith, the men behind this session in the warm spring of 1940, had also summoned two other musicians from New Orleans: bassist Wellman Braud and drummer Zutty Singleton. The band was completed by the (good) guitarist Bernard Addison and by Luis Russell on piano (he was the music-director for Satchmo’s big band). Clarence Williams, who published Coal Cart Blues (which Louis had already recorded with a big band in January 1938 under the title Satchel Mouth Swing, cf. Vol.8, FA-1358), also came down to Decca’s studio on that May 27th 1940, but he didn’t play. What he did do was have his photograph taken, along with the day’s two heroes. One of the photos appears on the front cover, and from it you can see that the three of them were all smiles... Whereas the truth is different: actually, it didn’t all go down as well as they wanted, and the atmosphere was tense, shall we say. According to Bechet, the trumpeter – a nasty, jealous man – was out to compete, and the climate he created was hardly suitable to produce a collective effort worthy of the name. Yes, we all know that Armstrong didn’t take kindly to an adversary, and the lyrical Bechet – even if his reputation was much smaller than that of Louis in those days – could indeed have been seen as a serious rival. That being said, we also know that Bechet wasn’t really the old softie he claimed to be during his final years in Paris. After all, his nickname was «Wild Cat», and no doubt he’d earned it: in his younger days he’d been known to whip out a blade or a .38 at the drop of a hat, and he’d been deported more than once; he was even an outcast in some countries, France among them. He didn’t like an adversary either, and when he didn’t actually pull a gun on someone he usually hogged the limelight (take a listen to the sides with Tommy Ladnier from 1932 and 1938: Tommy gets the meanest share.) So, was it a draw, then? Put it this way: the four sides they made in May 1940 (released under Armstrong’s name) are among the better things the two rivals are known for, especially Perdido and that 2:19 train blues.

Although these new versions were often honourable, they didn’t sell quite as well as expected, and the idea was dropped in 1941. The format, on the other hand, was much appreciated by the public, and Decca continued to record Armstrong with a small group. Unlike that May 27th 1940, however, there was no further attempt to set up a specific studio-band, and the label remained content to draw on the regular big band when necessary, with the result that Armstrong found himself alongside trombonist George Washington, saxophonist Prince Robinson, guitarist Lawrence Lucie, bassist John Williams, Luis Russell and Sidney Catlett when it came to forming a «pick-up» septet: in a way, they were the new «Hot Seven». They did eight sides in March/April 1941 with mixed results: it was nothing like the fabulous, original Hot Seven of May 1927. And yet... Everything’s Been Done Before, I Cover the Waterfront (in Armstrong’s book since 1933, but never recorded commercially), Hey Lawdy Mama and Now Do You Call That a Buddy are anything but lacklustre. On the subject of Buddy, Panassié – he thought it a masterpiece – pointed out that it was «one of his most poignant records.» Louis Armstrong didn’t make that many commercial records in 1941, for the same reasons as before: long and exhausting tours, this time taking him to Canada. It explains the sudden leap from spring to autumn in the three titles which close CD 3. These are excerpts from radio broadcasts aired in October and collected on shellac by Jerry Newman, that jazz-nut of a student who lugged around all that heavy, fragile equipment to record the sounds of tomorrow’s music in the clubs where it was played, whether at Minton’s or at Clark Monroe’s place. But Newman didn’t have anything against the music played by earlier generations. The best thing you can say about the quality of these original tracks is that they are dreadful, despite the shock-treatment given to them by François Terrazzoni. You might do well to remember that before he cleaned them up, you could hear practically nothing. Not even the background noise! Be warned.

Adapted by Martin Davies from the French text of Daniel NEVERS

© 2011 Frémeaux & Associés - Groupe Frémeaux Colombini

discographie

DISQUE / DISC 1

Louis ARMSTRONG & Orchestra – dir. Leith STEVENS (Saturday Night Swing Club Broadcast)

Louis ARMSTRONG (tp, voc) ; Nat NATOLI, Russ CASE, Willis KELLY, Robert JOHNSON (tp) ; Joe VARGOS, Wilbur SCHWITCHENBURG, Roland DUPONT (tb) ; Artie MANNERS, Toots MONDELLO, Hank ROSS, George TUDOR (saxes) ; Walter GROSS (p) ; Frank WORELL (g) ; Lou SHOOBE, Ward LAY (b) ; Billy GUSSAK (dm). New York City, 25/06/1938

1. SWING THAT MUSIC (L.Armstrong-H.Gerlach) (CBS Radio Show) 2’32

2. TWELFTH STREET RAG (E.L.Bowman) (CBS Radio Show) 1’59

Louis ARMSTRONG with the MILLS BROTHERS (Saturday Night Swing Club Broadcast)

Louis ARMSTRONG (tp, voc) ; Harry, Herbert, Donald, John Sr. MILLS (voc) ; Norman BROWN (g). New York City, 25/06/1938

3. THE FLAT FOOT FLOOGIE (S.Gaillard-S.Stewart) (CBS Radio Show) 2’12

Louis ARMSTRONG,Maxine SULLIVAN, Dick POWELL (voc), Choeur/Chorus & Studio Orchestra

(Film Goin’ Places – Prod. Warner Bros.) Hollywood, 09/1938

4. JEEPERS CREEPERS (H.Warren-J.Mercer) (1) (Son optique/Film soundtrack) 1’59

5. MUTINY IN THE NURSERY (Trad.- J. Mercer) (Son optique/Film soundtrack) 6’11

6. JEEPERS CREEPERS (H.Warren-J.Mercer) (2) (Son optique/Film soundtrack) 2’25

7. SAY IT WITH A KISS (H.Warren-J.Mercer) (Son optique/Film soundtrack) 1’28

MARTIN BLOCK PROGRAM

Louis ARMSTRONG (tp, voc) ; Jack TEAGARDEN (tb, voc) ; Lawrence “Bud” FREEMAN (ts) ; Thomas “Fats” WALLER (p, voc) ; Al CASEY (g) ; Wilmore “Slick” JONES ou/or Arthur “Zutty” SINGLETON ou/or George WETTLING (dm). New York City, 19/10/1938

8. HONEYSUCKLE ROSE (T.Waller-A.Razaf) (Radio Show) 1’17

9. ON THE SUNNY SIDE OF THE STREET (J.McHugh-D.Fields) (Radio Show) 5’19

10. TIGER RAG (D.J.LaRocca) (Radio Show) 4’31

11. I’VE GOT RHYTHM (G.& I. Gershwin) (Radio Show) 2’45

12. BLUES (Trad.) (Radio Show) 3’54

CARNEGIE HALL CHRISTMAS CONCERT

Louis ARMSTRONG (voc) ; poss. Roy BARGY (p), Allen REUSS (g), Art SHAPIRO (b) & choeur/chorus. New York City (Carnegie Hall), 25/12/1938

13. SHADRACK (R.McGimsey) (Radio) 4’14

14. NOBODY KNOWS THE TROUBLE I’VE SEEN (Trad.) (Radio) 3’06

LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND HIS ORCHESTRA

Louis ARMSTRONG (tp, voc) ; Henry “Red” ALLEN, Otis JOHNSON, Shelton HEMPHILL (tp) ; Wilbur De PARIS, J.C.HIGGINBOTHAM, George WASHINGTON (tb) ; Rupert COLE (cl, as) ; Charlie HOLMES (as) ; Albert NICHOLAS, Bingie MADISON (cl, ts) ; Luis RUSSELL (p, ldr, arr) ; Lee BLAIR (g) ; George “Pops” FOSTER (b) ; Sidney CATLETT (dm). New York City, 18/01/1939

15. JEEPERS CREEPERS (H.Warren-J.Mercer) (Decca F 6990/mx.64907-A) 2’39

16. WHAT IS THIS THING CALLED SWING ? (L.Armstrong-H.Gerlach) (Decca F 6990/mx.64908-A) 3’05

LOUIS ARMSTRONG with the CASA LOMA ORCHESTRA

Louis ARMSTRONG (tp, voc) ; Frank ZULLO, Grady WATTS, Sonny DUNHAM (tp) ; Murray McEACHERN (tb, as) ; Russell RAUCH, Walter “Pee Wee” HUNT (tb) ; Art RALSTON, Clarence HUTCHINRIDER (as) ; Pat DAVIS, Dan d’ANDREA (ts) ; Kenny SARGEANT (bar sax) ; Howard HALL (p) ; Jack BLANCHETTE (g) ; Stanley DENNIS (b) ; Anthony BRIGLIA (dm). New York City, 20/02/1939

17. ROCKIN’ CHAIR (H.Carmichael) (Decca F 7158/mx.65045-A) 3’15

18. LAZY BONES (H.Carmichael-J.Mercer) (Decca F 7158/mx.65046-A) 3’14

LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND HIS ORCHESTRA

Formation comme pour 15 & 16 / Personnel as for 15 & 16. New York City, 5/04/1939

19. HEAH ME TALKIN’ TO YA (L.Armstrong-D.Redman) (Decca F 7110/mx.65344-A) 3’05

20. SAVE IT, PRETTY MAMA (D.Redman) (Decca F 7110/mx.65345-A) 2’57

21. WEST END BLUES (J.Oliver-C.Willams) (Decca MU60455/mx.65346-A) 3’11

22. SAVOY BLUES (E.Ory) (Decca F 7177/mx.65347-A) 3’13

DISQUE / DISC 2

LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND HIS ORCHESTRA

Formation comme pour 15 & 16, disque 1 / Personnel as for 15 & 16, disc 1. Bernard FLOOD (tp) & Joe GARLAND (ts, bar sax, arr) remplacent/replace Otis JOHNSON & Albert NICHOLAS. New York City, 25/04/1939

1. CONFESSIN’ (Neiburg-Reynolds-Dougherty) (Decca F 7213/mx.65460-A) 3’13

2. OUR MONDAY DATE (L.Armstrong-E.Hines) (Decca F 7213/mx.65461-A) 2’27

3. IF IT’S GOOD THEN I WANT IT (A.Hirsch-J.B.Marks) (Decca F 7127/mx.65462-A) 2’34

4. ME AND BROTHER BILL (L.Armstrong) (Decca F 7177/mx.65463-A) 2’43

5. HAPPY BIRTHDAY TO BING (Hill) (Decca special/mx.TNY 755) 2’00

LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND HIS ORCHESTRA

Formation comme pour 1 à 4 / Personnel as for 1 to 4. New York City, 15/06/1939

6. BABY WON’T YOU PLEASE COME HOME (C.Williams-C.Warfield) (Brunswick A.505247/mx.65824-A) 3’16

7. POOR OLD JOE (version 1) (H.Carmichael) (Odéon 284649/mx.65825-A) 2’56

8. SHANTY BOAT ON THE MISSISSIPPI (J.Shand-E.Eaton) (Brunswick A505247/mx;65826-A) 3’20

LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND HIS ORCHESTRA

Formation comme pour 1 à 4 / Personnel as for 1 to 4. New York City (Carnegie Hall), 6/10/1939

9. THEME & OLD MAN MOSE (L.Armstrong-Z.Randolph) (Concert) 3’25

10. WHAT IS THIS THING CALLED SWING ? (L.Armstrong-H.Gerlach) (Concert) 5’06

LOUIS ARMSTRONG with the BENNY GOODMAN ORCHESTRA

Louis ARMSTRONG (tp, voc) ; “Ziggy” ELMAN, Jimmy MAXWELL, Johnny MARTEL (tp) ; S. “Red” BALLARD, Vernon BROWN, Ted VESELY (tb) ; C. “Bus” BASSEY, B. “Buff” ESTES, Jerry JEROME, “Toots” MONDELLO (saxes) ; Benny GOODMAN (cl, ldr) ; Fletcher HENDERSON (p) ; Arnold COVEY (g) ; Artie BERNSTEIN (b) ; Lionel HAMPTON (vibes) ; Nick FATOOL (dm). New York City, 14/10/1939

11. AIN’T MISBEHAVIN’ (T.Waller-A.Razaf) (Radio) 2’31

LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND HIS ORCHESTRA

Formation comme pour 1 à 4 / Personnel as for 1 to 4. New York City, 18/12/1939

12. POOR OLD JOE (version 2) (H.Carmichael) (Decca 3011/mx.66984-A) 3’02

13. YOU’RE A LUCKY GUY(S.Kahn-S.Chaplin) (Decca F 7567/mx.66985-A) 3’16

14. YOU’RE JUST A NO ACCOUNT (S.Kahn-S.Chaplin) (Decca F 7567/mx.66986-A) 2’52

15. BYE AND BYE (Trad.) (Decca 3011/mx.66987-A) 2’32

LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND HIS ORCHESTRA

Formation comme pour 1 à 4 / Personnel as for 1 to 4. New York City (Cotton Club), 18/12/1939

16. HARLEM STOMP (J.C.&I.Higginbotham) (Radio) 2’41

LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND HIS ORCHESTRA

Formation comme pour 1 à 4 / Personnel as for 1 to 4. New York City, 14/03/1940

17. HEP CAT’S BALL (L.Armstrong-C.Palmer) (Decca 3283/mx.67321-A) 3’16

18. YOU’VE GOT ME VOODOO’D (L.Armstrong-L.Russell-E.Lawrence) (Decca F 7598/mx.67322-A) 2’56

19. HARLEM STOMP (J.C.& I.Higginbotham) (Decca F 7598/mx.67323-A) 3’02

20. WOLVERINE BLUES (F.Morton-Spikes Br) (Decca F8099/mx.67324-A) 3’16

21. LAZY ‘SIPPI STEAMER (L.Armstrong-L.Russell-H.Selman) (Decca 3283/mx.67325-A) 3’16

LOUIS ARMSTRONG with the MILLS BROTHERS

Louis ARMSTRONG (tp, voc) ; John, Donald, Herbert, Harry MILLS (voc) ; Norman BROWN (g). New York City, 10/04/1940

22. W.P.A. (J.Stone) (Decca 03151/mx.67519-A) 2’45

23. BOOG IT (C.Calloway-Ramirez-Palmer) (Decca 03150/mx.67520-A) 2’35

DISQUE / DISC 3

LOUIS ARMSTRONG with the MILLS BROTHERS

Louis ARMSTRONG (tp voc) ; John, Donald, Herbert, Harry MILLS (voc) ; Norman BROWN (g). New York City, 11/04/1940

1. CHERRY (D.Redman) (Decca 03065/mx.67530-A) 2’46

2. MARIE (I.Berlin) (Decca 03065/mx.57531-A) 2’19

LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND HIS ORCHESTRA

Louis ARMSTRONG (tp, voc) ; Henry “Red” Allen, Bernard FLOOD, Shelton HEMPHILL (tp) ; Wilbur de PARIS, J.C. HIGGINBOTHAM, George WASHINGTON (tb) ; Rupert COLE (cl, as) ; Charlie HOLMES (as) ; Bingie MADISON (cl, ts, bar sax) ; Joe GARLAND (ts, bar sax, arr) ; Luis RUSSELL (p, ldr, arr) ; Lee BLAIR (g) ; George “Pops” FOSTER (b) ; Sidney CATLETT (dm). New York City, 1/05/1940

3. SWEETHEARTS ON PARADE (C.Lombardo-C.Newman) (Decca MU60442/mx.67648-A) 2’50

4. YOU RUN YOUR MOUTH, I’LL RUN MY BUSINESS (L.Armstrong) (Decca F 7849/mx.67649-A) 2’59

5. CUT OFF MY LEGS AND CALL ME SHORTY (H.Raye) (Decca F 8099/mx.67650-A) 2’30

6. CAIN AND ABEL (T.Fenstrock-A.Loman) (Decca F 7849/mx.676651-A) 2’59

LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND HIS ORCHESTRA

Louis ARMSTRONG (tp, voc) ; Claude JONES (tb) ; Sidney BECHET (cl, as) ; Luis RUSSELL (p) ; Bernard ADDISON (g) ; Wellman BRAUD (b) ; A. “Zutty” SINGLETON (dm). New York City, 27/05/1940

7. PERDIDO STREET BLUES (L.& L.Armstrong) (Decca 03164/mx.67817-A) 3’00

8. 2:19 BLUES (M.Desdume) (Decca 03164/mx.67818-A) 2’49

9. DOWN IN HONKY TOWN (C.Smith-C.McCarron) (Decca MU30558/mx.67819-A) 3’02

10. DOWN IN HONKY TOWN (C.Smith-C.McCarron) (Decca 18091/mx.67819-B) 3’02

Mêmes lieu, date & formation / Same place, date & personnel. Moins/minus JONES, RUSSELL & SINGLETON.

11. COAL CART BLUES (L. & L.Armstrong) (Decca MU30558/mx.67820-A) 2’55

LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND HIS HOT SEVEN

Louis ARMSTRONG (tp, voc) ; George WASHINGTON (tb) ; Prince ROBINSON (cl, ts) ; Luis RUSSELL (p, arr) ; Lawrence LUCIE (elg) ; John WILLIAMS (b) ; Sidney CATLETT (dm). New York City, 10/03/1941

12. EVERYTHING’S BEEN DONE BEFORE (Knopf-King-Adamson) (Decca 3825/mx.68796-A) 3’04

13. I COVER THE WATERFRONT (J.Green-D.Heyman) (Decca BM30719/mx.68797-A) 3’13

14. IN THE GLOAMING (Trad.) (Decca BM30681/mx.68798-B) 2’58

15. LONG, LONG AGO (Haynes-Bayley) (Decca BM30719/mx.68799-A) 2’52

LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND HIS HOT SEVEN

Formation comme pour 12 à 15 / Personnel as for 12 to 15. New York City, 11/04/1941

16. HEY LAWDY MAMA (A.Easton) (Decca MU60503/mx.68997-A) 2’59

17. I’LL GET MINE BYE AND BYE (J.Davis) (Decca MU60503/mx.68998-A) 3’04

18. DO YOU CALL THAT A BUDDY ? (C.Wilson-De Raye) (Decca 04297/mx.68999-A) 3’18

19. YES SUH ! (E.Dowell-A.Razaf) (Decca 04297/mx.69000-C) 2’19

LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND HIS ORCHESTRA

Louis ARMSTRONG (tp, voc) ; Frank GALBREATH, Shelton HEMPHILL, Gene PRINCE (tp) ; Henderson CHAMBERS, Norman GREENE, George WASHINGTON (tb) ; Rupert COLE (cl, as) ; Carl FRYE (as) ; Prince ROBINSON (cl, ts) ; Joe GARLAND (cl, ts, bass sax, arr) ; Luis RUSSELL (p) ; Lawrence LUCIE (elg) ; Hayes ALVIS (b) ; Sidney CATLETT (dm). New York City, 21/10/1941

20. BASIN STREET BLUES (S.Williams) (Radio – acetate) 3’24

21. LEAP FROG (J.Garland) (Radio – acetate) 3’51

22. EXACTLY LIKE YOU (J.McHugh-D.Fields) (Radio – acetate) 3’59

CD INTÉGRALE LOUIS ARMSTRONG “JEEPERS CREEPERS” 1938-1941 © Frémeaux & Associés (frémeaux, frémaux, frémau, frémaud, frémault, frémo, frémont, fermeaux, fremeaux, fremaux, fremau, fremaud, fremault, fremo, fremont, CD audio, 78 tours, disques anciens, CD à acheter, écouter des vieux enregistrements, albums, rééditions, anthologies ou intégrales sont disponibles sous forme de CD et par téléchargement.)