- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

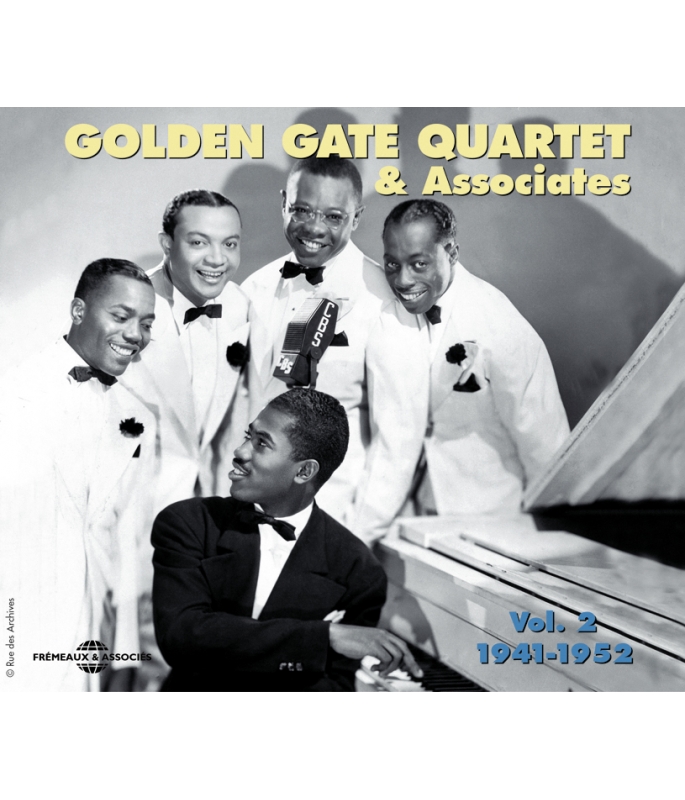

GOLDEN GATE QUARTET & ASSOCIATES 1941 - 1952

Ref.: FA5093

Artistic Direction : JEAN BUZELIN

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Total duration of the pack : 1 hours 53 minutes

Nbre. CD : 2

GOLDEN GATE QUARTET & ASSOCIATES 1941 - 1952

- -

GOLDEN GATE QUARTET & ASSOCIATES 1941 - 1952

To celebrate the 70 years existence of a major Afro-American vocal institution, still going strong and continually renewing itself, this trip back in time shows that, during these ten years packed full of history, the Golden Gate Quartet had already scaled the heights of religious music.

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1MOSES SMOTE THE WATERSOWENSTRADITIONNEL00:02:331941

-

2HANDWRITTING ON THE WALLOWENSTRADITIONNEL00:02:071941

-

3(YOU BETTER) RUN ONOWENSTRADITIONNEL00:02:441942

-

4MY TIME DONE COMEOWENSW JOHNSON00:02:451942

-

5STALIN WAS NOT STALLINOWENSW JOHNSON00:03:101943

-

6STRAIGHTEN UP AND FLY RIGHTOWENSNAT COLE00:02:251944

-

7BONES BONES BONES (EZEKIEL IN THE VALLEY)OWENS00:02:561954

-

8SWING DOWN CHARIOTOWENSTRADITIONNEL00:03:371946

-

9ATOM AND EVILOWENSH ZARET00:03:261946

-

10SHADRACKOWENSR MC GIMSEY00:02:411946

-

11HUSHOWENSTRADITIONNEL00:03:171946

-

12JOSHUA FIT THE BATTLE OF JERICHOOWENSTRADITIONNEL00:02:441946

-

13PRAY FOR THE LIGHT TO GO OUTOWENSTUNNAH00:03:071947

-

14TALKING JERUSALEM TO DEATHOWENSTRADITIONNEL00:02:471948

-

15JESUS MET THE WOMAN AT THE WELLRIDDICKJ W ALEXANDER00:02:581949

-

16JEZEBELSMITHTRADITIONNEL00:02:311943

-

17LORD HAVE MERCYBAXTERTRADITIONNEL00:03:031944

-

18I M ON MY WAYJ C GINYARDTRADITIONNEL00:03:011945

-

19THERE LL BE A JUBILEERUTH00:02:511945

-

20RUN ON FOR A LONG TIMEBILL LANDFORD THE LANDFORDAIRETRADITIONNEL00:02:371949

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1JOHN SAW THE WHEELRIDDICKTRADITIONNEL00:02:501949

-

2LORD I AM TIRED AND I WANT TO GO HOMERIDDICKTRADITIONNEL00:03:061949

-

3LORD I WANT TO BE A CHRISTIANRIDDICKTRADITIONNEL00:02:561949

-

4RELIGION IS A FORTUNERIDDICKTRADITIONNEL00:02:401949

-

5WHEN THE MOON GOES DOWNRIDDICKTRADITIONNEL00:02:291949

-

6DOWNWARD ROADRIDDICKTRADITIONNEL00:02:341949

-

7AMAZING GRACERIDDICKJOHN NEWTON00:03:091949

-

8THIS WORLD WORLD (IS IN A BAD CONDITION)RIDDICKTRADITIONNEL00:03:280

-

9HOLD ONRIDDICKTRADITIONNEL00:03:371949

-

10GIVE ME TWO WINGSRIDDICKTRADITIONNEL00:02:501949

-

11THERE S A MAN GOING ROUND TAKING NAMESRIDDICKTRADITIONNEL00:02:361950

-

12SAME TRAINRIDDICKTRADITIONNEL00:02:281950

-

13YOU D BETTER MINDRIDDICKTRADITIONNEL00:02:301950

-

14LISTEN TO THE LAMBSRIDDICKTRADITIONNEL00:02:551950

-

15I JUST TELEPHONE UPSTAIRSRIDDICKTRADITIONNEL00:02:461952

-

16LIVE A HUMBLEJOHNSONTRADITIONNEL00:02:341948

-

17JOE LOUIS IS A FIGHTIN MANJ C GINYARDJ C GINYARD00:03:011950

-

18NEW BORN AGAINJ C GINYARDTRADITIONNEL00:02:321950

-

19SORROW VALLEYBROWNA BUNN00:02:511949

-

20HONNEY ON THE ROCKMUMFORDGRAVES00:02:391950

Golden Gate Quartet FA5093

GOLDEN GATE QUARTET

& Associates

Vol. 2

1941-1952

En 1992 paraissait, sous l’égide d’une jeune maison de disques, Frémeaux & Associés, et de la Discothèque des Halles, un premier coffret de deux CD retraçant les débuts de l’histoire du Golden Gate Quartet, de ses origines et sa constitution jusqu’à sa consécration, illustré par un choix de ses meilleurs disques réalisés entre 1937 et 1941 (1). Douze années ont passé, la marque Frémeaux & Associés possède désormais un impressionnant catalogue dans lequel la musique religieuse d’origine afro-américaine occupe une place de choix, tant dans le domaine de la réédition du patrimoine historique que dans celui de la production d’enregistrements récents. Entre ces douze années, Orlandus Wilson, qui avait soutenu notre premier ouvrage, est parti vers un autre monde qu’il avait si souvent chanté, suivi de près par son vieux camarade Clyde Riddick. Mais cela n’a pas signifié la fin du Golden Gate Quartet. Paul Brembly a invité Clyde Wright à reprendre du service et le groupe a enregistré coup sur coup deux disques, l’un prenant en compte les sonorités modernes (2), l’autre, chanté a cappella, renouant avec l’expression primitive du quartette à ses débuts (3). Il convenait à présent de reprendre le cours de l’histoire au moment où nous l’avions laissé. C’est chose faite à présent avec ce parcours qui nous conduit de 1941 à 1952, date où s’arrête leur carrière phonographique américaine avant que l’Europe ne les accueille en 1955. Cette période étant celle où le personnel des Gates a connu le plus de mouvement dans ses rangs, il nous a paru intéressant de compléter ce panorama par quelques disques de quartettes voisins, frères pourrait-on dire, dans lesquels ont chanté les membres du Golden Gate Quartet. Retrouver la voix de ces hommes ailleurs c’est aussi mieux inscrire le groupe dans son histoire et dans son environnement au milieu d’ensembles qui se sont souvent inspirés de lui. Ainsi se dessine, en quelque sorte, l’arbre généalogique d’une grande famille…

Jean Buzelin & Patrick Frémeaux

Quand, durant l’été 1936, le jeune Orlandus Wilson (il est né en 1917) intègre le groupe vocal formé en 1930 par Eddie Griffin, Henry Owens, Willie Johnson et Robert Ford, celui-ci porte le nom, depuis 1934, des Golden Gate Jubilee Singers. Un an avant son arrivée, William Langford avait remplacé Griffin au poste de 1er ténor, et lui-même devient la basse de l’ensemble à la place de Ford. Basé à Norfolk, en Virginie, le quartette est alors dirigé par le baryton Willie “Bill” Johnson, arrangeur du répertoire et lead vocal principal, s’exprimant d’une manière nouvelle, un style narratif rythmique qui se présente comme une sorte de récitatif du preaching arrangé et intégré aux harmonies vocales du quartette. Ce style aura d’énormes retombées dans le domaine de l’art vocal afro-américain. Avec les Gates, le terme jubilee, qui provenait des harmonizing quartets hérités des groupes policés formés dans les collèges et les universités au moment de l’émancipation, va signifier désormais un genre de rhythmic spiritual quartets qui assimile en particulier la syncope ainsi que le rythme et le swing du jazz.

Malgré les réticences de certains ministres du culte qui trouvent leur manière de chanter, héritée en partie de la manière profane des Mills Brothers, un peu déplacée, le groupe commence à se produire à partir de 1935 dans les églises des villes voisines : Richmond, Tidewater… et, en 1936, fait une première tournée en Caroline du Sud, effectuant par là même ses débuts à la radio WIS de la ville de Columbia. Durant l’année 1937, son audience grandit après plusieurs passages dans l’émission “Magic Key Hour” de la NBC qui bénéficie d’une couverture nationale.

Alors qu’ils se trouvent à Charlotte (Caroline du Nord) en août 1937, les quatre chanteurs sont conviés à une séance d’enregistrement par la compagnie Victor qui a installé son studio itinérant dans un hôtel de la ville. Quatorze morceaux sont gravés en deux heures et, bientôt, apparaissent sur le marché les premiers disques Bluebird du Golden Gate Jubilee Quartet. Le succès du premier d’entre eux, Golden Gate Gospel Train, est considérable et les Gates, installés désormais à Charlotte, animent une émission de radio quotidienne sur la WBT, émetteur qui, en 1938, couvre cinq ou six états, de la côte Est à la Géorgie et au Tennessee. Une seconde séance marathon est organisée en janvier 38 à nouveau au Charlotte Hotel avant que le groupe ne soit convoqué à New York dans de vrais studios en août et en novembre de la même année. Puis, alors qu’ils rayonnent autour de Charlotte, leur point d’attache, ils participent à une nouvelle séance dans un hôtel, cette fois-ci à Rock Hill (Caroline du Sud) en février 1939 avant de retrouver les studios new-yorkais en octobre. Durant toute cette période, Victor sort, sous son étiquette Bluebird, un disque par mois du Golden Gate Jubilee Quartet ! Ils sont ensuite sollicités par la chaîne de radio CBS pour animer chaque jour une émission et, peu après à la demande des responsables, ils enlèvent le mot jubilee de leur nom pour devenir, à la radio, sur disques et en public, le Golden Gate Quartet.

C’est ainsi qu’ils apparaissent sur la scène du Carnegie Hall le 24 décembre 1939 pour le second concert “From Spirituals to Swing” organisé par le critique et grand découvreur de talents John Hammond (4). Après le concert, Hammond les emmènent, ainsi que Big Bill Broonzy et Ida Cox qui figuraient au même programme, au Café Society, premier club multiracial de New York où se presse la clientèle chic dans le vent et l’intelligentsia libérale. Chacun est invité à interpréter une chanson mais les Gates obtiennent un tel succès public que le patron des lieux, Barney Josephson, leur signe immédiatement un engagement pour six mois ! Deux jours plus tard, ils participent à une nouvelle séance pour Bluebird et, le lendemain, font leurs vrais débuts au Café Society.

Tandis que le quartette se produit chaque soir a cappella devant la clientèle de la boîte, le directeur de la Columbia leur demande de chanter à la radio avec un accompagnement de guitare. Déjà leur répertoire, au départ essentiellement composé de negro spirituals, s’était élargi avec l’enregistrement pour le disque de quelques standards et pop songs et, pour cela, William Langford s’était mis à jouer de l’instrument. Cette orientation était certainement due au désir des producteurs de voir les Gates concurrencer les Mills Brothers et surtout les Ink Spots, le pop group n°1 du pays.

Mais c’est sur un tout autre répertoire cette fois, celui des chants de travail issus du folklore noir, que le Golden Gate Quartet augmenté de Clyde Riddick accompagne le vieux songster Leadbelly pour une dernière session Victor/Bluebird en juin 40. En effet, déjà bien engagés chez Columbia grâce à la radio, les chanteurs vont désormais graver leurs disques pour la même maison à partir d’avril et mai 1941. Quelques mois auparavant, en janvier, ils avaient participé à la cérémonie d’investiture du Président Roosevelt au Constitution Hall. Entendus, paraît-il, par Madame la Présidente elle-même au Café Society, les Gates sont peut-être le premier groupe d’artistes noirs à être invités à la Maison Blanche (5). La même année, ils effectuent une tournée au Mexique avant de se rendre à Hollywood où ils participeront à plusieurs films : “Star-Spangled Rhythm”, “Hollywood Canteen”, “Bring on the Girls” et “Hit-Parade of 1943” retitré plus tard “Change of Hearts”.

Outre leurs disques commerciaux pour OKeh/Columbia, plusieurs séries de transcriptions radiophoniques (pour la General Electric, NBC, AFS-Jubilee) permettent d’entendre les Gates en cette période où les Etats-Unis entrent en guerre et que, par ailleurs, se profile la longue grève des enregistrements décrétée par le syndicat des musiciens. Ils gravent également un V-Disc destiné aux soldats américains partis sur le front.

Cette époque perturbée, quoique prolifique pour le groupe, occasionne quelques mouvements dans ses rangs. Ainsi William Langford, leur high tenor à la forte présence scénique (sa voix allait en fait du falsetto au baryton) les a quittés vers la fin de l’année 1940 pour rejoindre les Southern Sons.

Formé en 1935 à Newark (New Jersey), inspirés à la fois par les Mills Brothers et les Gates, les Southern Sons sont déjà réputés dans la région. Mais l’arrivée de Langford apporte rapidement au groupe une notoriété supérieure. Il devient leur manager et leur obtient un contrat avec Bluebird, le label du Golden Gate ! Ils enregistrent à partir de 1941 et obtiennent un grand succès l’année suivante avec Praise The Lord And Pass The Ammunition. Ils tournent dans le Sud en 1942 et animent régulièrement un show radiophonique à la station WBT de Charlotte (là où précisément avaient débuté les Gates). Après la mort prématurée de leur leader et guitariste James Baxter, Langford et la basse Clifford Givens quittent le groupe qui cessera peu après ses activités phonographiques.

William Langford entre alors chez les Selah Jubilee Singers où il reste plusieurs années avant de former les Landfordaires qui enregistreront quelques disques en 1949, puis le Bill Landford Quartet. Il deviendra plus tard disc-jokey de musique religieuse à Winston-Salem (Caroline du Nord) avant de s’éteindre en 1969.

Tout naturellement, c’est Clyde Riddick qui prend la place de 1er ténor. Lié au groupe depuis ses débuts, il avait brièvement remplacé Eddie Griffin avant que Langford ne prenne la place. Si ce n’est quelques remplacements temporaires, c’est donc le nouveau quartette de base, Riddick-Owens-Johnson-Wilson, qui enregistre les disques OKeh en ce début de la décennie, parfois accompagnés par une guitare. Sans doute s’agit-il de Abe Green qui a joué avec les Gates pendant environ quinze mois en 1942 et 43 avant d’être appelé sous les drapeaux. À sa libération, il passera environ neuf mois chez les Jubalaires avant de rejoindre les Dixieaires qu’il quittera vers 1950/51.

En 1943, malgré la grève dans les studios, le Golden Gate Quartet enregistre un morceau d’actualité écrit par Willie Johnson, Stalin Wasn’t Stallin’. Cette démarcation du spiritual Preacher And The Bear aura un certain retentissement sur le marché du disque des race records qu’on appellera bientôt Rhythm & Blues. Jacques Demêtre avait traduit naguère les paroles de cette histoire imagée anti-nazie :

Staline n’a pas atermoyé

Quand il a dit à la bête de Berlin

Qu’il ne cesserait jamais de lutter

Tant qu’ils ne partiraient pas de son pays.

Aussi a-t-il appelé Américains et Anglais

Et se mit-il à anéantir

Le Führer et son incendie,

C’est ainsi que tout a commencé.

Le Diable a lu

Un jour dans la Bible

Comment le Seigneur avait créé Adam

Pour suivre une voie juste.

Ceci rendit le Diable jaloux

Il en devint vert jusqu’aux cornes

Et il jura sur des choses impies

Qu’il en créerait un bien à lui,

Aussi fit-il deux valises

Pleines de douleur et de misère

Et il prit le train de minuit

Qui descendait vers l’Allemagne,

Puis il mélangea ses mensonges et mit

Le feu aux poudres

Ensuite le Diable s’assit dessus

Et c’est ainsi qu’Adolf est né. (6)

1943 est aussi l’année où est mobilisé Willie Johnson, suivi un peu plus tard par Orlandus Wilson. Le premier est remplacé d’abord brièvement par Joseph E. Johnson qui formera plus tard les Trumpeteers, puis par Alton Bradley, auparavant lead vocal du Silver Echo Quartet et qui déjà se trouvait dans la mouvance du groupe. Le second par Clifford Givens, l’une des plus grandes basses de toute l’histoire des quartettes vocaux.

Comme les Southern Sons, le Silver Echo Quartet était également un ensemble vocal bien connu dans la région de Newark, donc un de leurs concurrents directs. Ils animaient une émission de radio à Paterson (New Jersey) et feront une tournée d’un mois avec l’orchestre de Woody Herman. Ils enregistrent à plusieurs reprises en 1943 et 1944, jusqu’au moment où Alton Bradley les quitte. Ils survivront quelques années avec difficultés.

Né en 1918 à Newark (New Jersey), Clifford Givens chantait depuis 1935 avec les Southern Sons et était connu pour avoir été le premier à transposer vocalement le bourdonnement (poum, poum, poum) de la contrebasse dans la musique religieuse (sachant que John Mills utilisait déjà ce procédé d’imitation). Après avoir quitté les Southern Sons et remplacé un temps Hoppy Jones, la fameuse basse des Ink Spots qui venait de mourir, Clifford Givens assure donc l’intérim pendant que Orlandus Wilson fait son service dans la Marine. Entre le timing parfait, le sens inné du placement et la voix grasse, granuleuse et profonde de Wilson, et la souplesse plus instinctive et improvisée et la rondeur chaude de la voix de Givens, il y a deux approches très différentes du rôle de la basse. La couleur d’ensemble du quartette change donc quelque peu d’autant que Bradley, soliste, n’est pas un “narrateur“ comme Johnson. Contrairement à ce qu’indiquent habituellement les discographies, Clifford Givens ne participe à aucun enregistrement commercial, mais on peut l’entendre dans plusieurs transcriptions radiophoniques comme Straighten Up And Fly Right, le succès de Nat King Cole. En outre, suivant en cela l’exemple de nombreux pop quartets, les Gates remplacent la guitare par le piano et engagent Conrad Frederik. En juin 1946, le quartette reconstitué avec Johnson et Wilson, réalise une mémorable séance pour Columbia en compagnie d’une section rythmique de jazz. Une certaine quintessence de leur travail et un art qui atteint une sorte de perfection. Parmi les huit morceaux enregistrés, Shadrack restera peut-être leur plus grand succès et la plupart des titres figureront sur leur premier 33 tours 25 cm qui paraîtra l’année suivante en direction d’une nouvelle clientèle (blanche). Ces nouveaux disques microsillons constituent, avec la bande magnétique, une nouvelle technique promise à un bel avenir. Cette même année 1947, les Gates retournent à Hollywood pour des émissions de radio et pour participer à une grande production cinématographique de Sam Goldwin avec Danny Kaye :“A Song is Born” (en français “Fa dièse et Si bémol” !), dans laquelle apparaissent également Louis Armstrong, Benny Goodman, Lionel Hampton, Tommy Dorsey, Charlie Barnet et Mel Powell.

Au printemps 1948, les Gates voient leur so-liste principal et emblématique, Willie Johnson, les quitter définitivement pour échanger sa place avec Orville Brooks (né en 1919 dans le Maryland) chez les Jubalaires, un groupe avec lequel il collaborait déjà depuis quelque temps.

Les Jubalaires, originellement appelés les Royal Harmony Singers, avaient été réunis à Jacksonville (Floride) par J.C. Ginyard en 1936. À partir de 1941 ils résident à Philadelphie, gravent deux disques puis changent de nom et remplacent, en 1944, le Golden Gate Quartet au Café Society. Très sollicités par le radio (avec un programme régulier à la CBS), pour les soundies (petits films de juke boxes) et pour le disque de 1944 à 1949, les Jubalaires obtiennent un hit en 1946 avec I Know, accompagnés par le grand orchestre de Andy Kirk. Ils entament alors une tournée nationale avec Kirk et s’installent en Californie où ils participent à des shows ainsi qu’au film “The Joint is Jumping” entièrement interprété par des acteurs de couleur. À l’arrivée de Willie Johnson, J.C. Ginyard quitte le groupe pour former, avec deux chanteurs du Silver Echo Quartet dont les activités ont faibli, un nouveau pop/jubilee quartet, les Dixieaires. Willie Johnson restera de longues années le leader des Jubalaires qui deviendront plus tard les Jubilee Four – on les voit dans le film “Viva Las Vegas” avec Elvis Presley – avant de décéder au début des années 80.

Les Dixieaires n’auront qu’une brève existence bien que fructueuse sur le plan discographique. Constitués à New York en 1947, ils s’affirment comme les concurrents directs des Jubalaires – Ginyard a amené avec lui une partie du matériel de son ancien groupe –, enregistrent de nombreux disques dans un style narratif rythmiquement accentué entre 1947 et 1951, obtenant même un certain succès avec Go Long en 1948, et effectuent plusieurs tournées à travers le pays.

L’année 1948 marque la fin de la collaboration entre Columbia et le Golden Gate Quartet qui passe chez Mercury où plusieurs séances ont lieu l’année suivante. Tout en maintenant le genre jubilee qu’ils ont réinventé à la fin des années 30, les Gates ne peuvent rester insensibles aux évolutions, pour ne pas dire aux bouleversements, qu’engendre musicalement l’après-guerre. En plus de la présence d’accompagnateurs instrumentistes, ils ajoutent quelques touches de “modernisme” à leurs interprétations et à leur répertoire. Ainsi, Talking Jerusalem To Death comprend un récitatif différent et Jesus Met The Woman At The Well est un gospel song écrit par James W. Alexander pour les Pilgrim Travelers (7) qui enregistrent le morceau le même mois. La pièce est plus accentuée rythmiquement et fait entendre le chœur à l’unisson, ce qui est rare dans le style jubilee mais courant chez les nouveaux quartettes. Le déclin populaire des pop groups, Mills Brothers, Ink Spots, Charioteers, Deep River Boys, etc., les pousse également à délaisser quelque peu cette partie profane d’un répertoire vite daté. Enfin, la concurrence est rude avec les quartettes qui se sont inspirés d’eux, les ont imités et ont souvent gravé des reprises (covers) de leurs interprétations, surtout si celles-ci sont amenées par des Gates dissidents ! Ainsi le Siver Echo reprend Jezebel, Anyhow…, les Selah Gospel Train…, les Jubalaires I’m On My Way, The Valley Of Time…, les Lanfordaires Run On…, les Dixieaires You Better Run, My Lord Is Writing, etc. Malgré tout, leurs anciens disques Bluebird sont toujours réédités par Victor, signe que les ventes restent confortables.

En 1950, Henry Owens, le plus ancien membre des Gates puisqu’il était l’un des quatre fondateurs du premier quartette en 1930, quitte le groupe pour devenir preacher baptiste. Second ténor et parfois lead vocal, Owens apportait un côté gospel à l’ensemble et possédait une grande science de l’harmonie, s’inscrivant parfaitement entre le premier ténor et le baryton. Les spécialistes considèrent qu’il fut la voix la plus pure du Golden Gate Quartet. Il est mort en 1970. Alton Bradley glisse alors “à l’aile”, de la place de baryton à celle de ténor et le quartette se retrouve… à quatre. C’est cette formation qui enregistre une rare et superbe série de negro spirituals réunie plus tard dans un album Concert Hall. Leurs interprétations, variées, vont de traitements dans leur manière classique à une évolution vers le gospel moderne Two Wings, avec une étonnante version de l’hymne Amazing Grace comprenant un lead vocal presque hard !

Leur producteur Bob Shad a quitté Mercury pour fonder sa propre marque, Sittin’ In With, en emportant avec lui des bandes enregistrées antérieurement par les Gates. Il va les publier sur son nouveau label entre la fin décembre 1950 et le printemps 1951 (8). Tout cela signifie que les Gates sont libres de contrat et ils retournent chez Columbia. Henry Owens revient donner un coup de main pour une première séance réalisée en novembre 1950.

Mais une page est en train de se tourner, du moins si l’on en croit l’industrie phonographique qui ne s’intéresse plus guère au style jubilee. Les Dixieaires sont dissous et J.C. Ginyard rejoint les Du-Droppers en 1952, ensemble profane tourné vers le rhythm and blues. Clifford Givens reforme de nouveaux Southern Sons à Little Rock (Arkansas), un ensemble beaucoup plus brut, proche des groupes de gospel du Sud comme le Spirit of Memphis Quartet. Mais le succès n’arrive pas et, après une belle série d’enregistrements entre 1950 et 1953, Givens rejoindra les Dominoes, vedettes du R&B. Installé à Los Angeles à la fin des années 50, il travaille en soliste et prête sa voix exceptionnelle en studio auprès de chanteurs et de groupes variés. Clifford Givens est mort en 1989.

Bien que ne possédant pas la popularité des Gates, les Selah Jubilee Singers s’en sortent mieux. Ils bénéficient d’une bonne notoriété et d’une excellente réputation. Ce sont eux qui font les chœurs derrière Mahalia Jackson sur les disques (9) et souvent en concert (10). À l’origine les Selah Jubilee Six, le groupe avait été fondé dès 1927 à Brooklyn par Thurman (ou Thermon) Ruth et avait participé en 1931 à une séance demeurée inédite. Jusqu’au début des années 40, l’ensemble se produit essentiellement dans les églises sanctifiées de Brooklyn et de Harlem avant de commencer à voyager sur la côte Est (émissions de radio à la WPTF de Raleigh) et jusqu’au Texas. Ils enregistrent abondamment à partir de 1939 et entrent dans le “Top 40“ de l’année 1941 avec I Feel Like My Time Ain’t Long. Porteurs d’une tradition forte, ils ont toujours maintenu un côté expressif naturel et peuvent ainsi sans difficultés faire ressortir cet aspect que recherchent et expriment les quartettes de gospel modernes. De plus, changeant de nom comme de maison de disques, ils couvrent selon la demande un très large éventail, allant des negro spirituals et des gospel songs quand ils s’appellent, outre le Selah Jubilee Quartet, les Sons of Heaven, les Jubilators ou les Southern Harmonaires, au rhythm and blues quand ils deviennent les Four Barons, les Cleartones et surtout les Larks avec un certain succès. Malgré un trou discographique entre 1950 et 1955, les Selah accompliront une longue carrière.

En 1951, les Gates accueillent Eugene Mumford en remplacement de Alton Bradley. Ténor à la voix flexible et modulée, il vient de quitter précisément les Selah Singers. Malgré plusieurs années passées avec les Gates, on ne peut l’entendre en soliste que sur le seul disque publié sous étiquette Okeh après l’ultime séance américaine du groupe, I Just Telephone Upstairs. Il entrera ensuite chez les Dominoes et fera carrière dans la musique profane.

Ainsi s’achève, alors que Herman Flintall s’est installé au piano à la place de Conrad Frederick, notre histoire sonore du Golden Gate Quartet aux Etats-Unis. L’évolution musicale et commerciale qui favorise des formes d’expression plus brutes, débridées et spectaculaires (par exemple les quartettes de hard gospel) ou, au contraire, accentue les interprétations doucereuses (les groupes vocaux doo-wop), laisse de moins en moins d’espace, au centre, pour les jubilee quartets et le premier d’entre eux, le Golden Gate Quartet, pourtant à l’origine des formes modernes qui constituent le rhythm and blues et annoncent le rock ‘n’ roll. Mais le groupe n’arrête pas ses activités pour autant. Deux changements de personnel se produisent en 1954 avec l’arrivée du baryton Bill Bing qui remplace Orville Brooks parti chez les Larks, et surtout du ténor Clyde Wright, né en 1928 à Charlotte, qui, après avoir succédé à Mumford chez les Selah Singers, fait de même au sein du Golden Gate Quartet (10). Cinquante ans plus tard, après quelques allers-retours, Wright reste le fer de lance de l’illustre formation (2)(3). Bill Bing, bientôt, sera remplacé par Frank Todd, qui lui-même cédera sa place en 1956 à J.C. Ginyard. Né en 1910 en Caroline du Sud, le baryton Junior Caleb Ginyard a déjà une solide carrière au sein de plusieurs ensembles dont nous avons parlé plus haut (Jubalaires, Dixieaires, Du-Droppers). Quittant ces derniers, il rejoint le Golden Gate en Europe. Durant une quinzaine d’années, ce chanteur accompli reprendra parfaitement le rôle du soliste narratif qu’avait créé Willie Johnson et que n’avaient pas vraiment poursuivi ses successeurs. Il quittera le groupe pour raisons de santé en 1971, se produira en soliste à Bâle où il s’est retiré et où il mourra en 1978.

L’aventure du Golden Gate Quartet se poursuit donc en dehors des Etats-Unis. Après une tournée au Canada, elle prend un nouvel envol en Europe et, un demi-siècle plus tard, continue toujours… En novembre 1955, le quartette Riddick-Wright-Todd-Wilson, avec leur pianiste Irwin Trottman, se produit à l’Olympia de Paris en vedette américaine d’Annie Cordy et enregistre le même mois, sous l’égide de Jean-Paul Guiter, directeur artistique chez Pathé-Marconi, la matière à plusieurs 78 tours qui paraissent sous étiquette Columbia (dont Pathé possède la licence). Entrecoupées de retours périodiques sur le sol natal, les tournées s’enchaînent et le groupe triomphe dans toute l’Europe et enregistre à Paris, à Londres (en 1956), à Berlin (en 1957) avec Ginyard et en compagnie de leur nouveau pianiste Glenn Burgess et de certains des meilleurs musiciens de jazz français. En 1958, une tournée patronnée par le Département d’État américain les emmène, à partir de la Grèce, dans vingt-huit pays du Moyen et de l’Extrême-Orient. En 1959, les Gates signent un engagement de deux ans au Casino de Paris, effectuant leurs débuts dans ce célèbre lieu avec la revue “Plaisir” dont Line Renaud est la vedette ; Clyde Wright a raconté la visite que leur fit un soir Elvis Presley (2).

Installés désormais à Paris, ils enregistrent régulièrement pour Columbia/Pathé jusqu’en 1969, et s’échappent de la capitale pour donner des concerts aux quatre coins du monde. Ils effectuent notamment une nouvelle tournée avec le soutien de Département d’État qui les envoie durant six mois dans vingt-six pays africains.

En 1971, Paul Brembly, le petit neveu de Orlandus Wilson, et Calvin Williams remplacent respectivement J.C. Ginyard et Clyde Wright. Parmi leurs disques qui sortent régulièrement, en particulier sur la marque Ibach, retenons l’album “ Jubilee ” qui consacre en 1980 vingt-cinq ans de carrière en Europe et dans le monde. L’année 1984 voit le retour de Clyde Wright qui, une dizaine d’années plus tard, reprend sa liberté, laissant sa place à Charles West, tandis que Frank Davis remplace Clyde Riddick qui, fin 1994, décide de raccrocher à l’âge respectable de 81 ans, avant de nous quitter définitivement cinq ans plus tard, le 9 octobre 1999. Toujours en 1994, la “United Group in Harmony Association” de New York, introduit le Golden Gate Quartet dans son “Hall of Fame”. Cette cérémonie s’accompagne de concerts, émissions de radio et de télévision. Enfin, désireux à son tour de se reposer, le leader et arrangeur du groupe depuis la guerre, celui qui n’a jamais chanté ailleurs qu’au sein des Gates, Orlandus Wilson a le temps de former son successeur en la personne du jeune Martiniquais Terry François avant de s’éteindre le 31 décembre 1998. Ce choix montre bien que la musique du Golden Gate Quartet a, depuis longtemps déjà, acquis une dimension universelle.

Les dix années que nous venons de parcourir en compagnie de ce merveilleux ensemble ne sont pas forcément les plus connues de leur carrière. Elles regorgent pourtant d’interprétations lumineuses et magnifiques qui sous-tendent une recherche vers un absolu que bien peu de chanteurs et de musiciens ont réussi à approcher. La quintessence d’un genre majeur de l’art vocal de l’Amérique noire est ici exprimée à la fois dans une certaine perfection formelle et dans un désir de communication naturelle. C’est cet équilibre quasi magique qui fait la grandeur du Golden Gate Quartet, lequel, après 70 ans d’existence, touche encore chacun au plus profond de lui-même.

Jean Buzelin

Auteur de Negro Spirituals & Gospel Songs,

Chants d’espoir et de liberté

(Ed. du Layeur/Notre Histoire, Paris 1998)

© FRÉMEAUX & ASSOCIÉS/GROUPE FRÉMEAUX COLOMBINI SA, 2004

Notes :

(1) Golden Gate Quartet/Gospel 1937-1941 (FA 002)

(2) Voir The Golden Gate Quartet/Made in Raleigh (FA 452)

(3) Voir The Golden Gate Quartet & The Good Book (FA 465)

(4) Et non, comme nous l’avions écrit par erreur sur notre premier volume (FA 002) et comme l’indiquent la plupart des textes historiques et biographiques, au premier concert le 23 décembre 1938 ; ce que confirme l’édition récente du coffret “définitif“ From Spirituals to Swing (Vanguard 169-2)

(5) Malgré le soutien de Eleanor Roosevelt, Marian Anderson avait essuyé un refus en 1939, ce qui avait fait grand bruit

(6) In Jazz Hot n° 345/46, février 1978

(7) Les Pilgrim Travelers avaient d’ailleurs débuté sur disques en 1946 en reprenant des morceaux chantés par les Gates ; ils deviendront par la suite l’un des grands quartettes de gospel moderne

(8) Il est impossible de connaître les dates exactes de ces enregistrements car ils portent des numéros de matrice SIW, et non Mercury, donc postérieurs aux séances de studio

(9) En particulier sur l’original In The Upper Room ; voir Complete Mahalia Jackson Vol.1 (FA 1313)

(10) Clyde Wright se souvient d’avoir chanté et enregistré avec les Selah dès 1949 (cf. CD2/19 pour lequel il donne un personnel différent des discographies) ; il a souvent assuré les chœurs derrière Mahalia Jackson et Sister Rosetta Tharpe.

Dans notre premier volume (1), nous avions traité plus largement de la place du Golden Gate Quartet dans l’histoire des quartettes vocaux, des caractéristiques et de l’originalité de sa musique, et de la teneur de son répertoire, essentiellement composé de negro spirituals traditionnels. Nous n’avons pas repris ici ces chapitres spécifiques auxquels nous renvoyons le lecteur/auditeur.

Ont été consultés les textes de pochettes et de livrets de Billy Altman, Christian Bonneau, Paul Brembly, Jacques Demêtre, Ray Funk, Peter A. Grendysa, Daniel Nevers, Orlandus Wilson et Clyde Wright, ainsi que Cedric J. Hayes & Robert Laughton, Gospel Records (RIS, 1993).

Nous remercions chaleureusement François-Xavier Moulé, Étienne Peltier et Robert Sacré pour le prêt de leurs rares 78 tours, ainsi que Yvan Amar, Jacques Demêtre et Clyde Wright.

Photos et collections : X (D.R), Jean Buzelin, Ray Funk, Jean-Paul Guiter, James Kriegsmann, Gilles Pétard.

Recto : Rue des Archives (O. Wilson, W. Johnson, H. Owens, C. Riddick, C. Frederick - piano).

GOLDEN GATE QUARTET

& Associates

Vol. 2

1941-1952

In 1992 a relatively new recording company, Frémeaux & Associés, along with Discothèque des Halles, issued their first double boxed set retracing the story of the Golden Gate Quartet, from the very beginning until they were firmly established as show business stars, featuring some of the best recordings they made between 1937 and 1941 (1). Some twelve years on Frémeaux & Associés have now built up an impressive catalogue, much of it devoted to Afro-American religious music comprising both reissues of old recordings alongside more recent ones. In the intervening years Orlandus Wilson, who gave his backing to this first album, left us for that other world he had so often celebrated in song, soon followed by his old friend Clyde Riddick. But this was by no means the end of the Golden Gate Quartet. Paul Brembly invited Clyde Wright to rejoin the ranks and the group made two records, one in a more modern style (2), the other sung a cappella and recalling the style of the Quartet’s early days (3). We now take up the story where we left it in 1941 to continue it up to 1952, the year that marked their last recording date in America before Europe welcomed them with open arms in 1955.

This period saw a number of personnel changes in the group so we decided it might be of interest to add a few recordings by other quartets around at the time with which members of the Golden Gate Quartet sang. A way of situating these men within the musical environment of their time by hearing them singing with similarly inspired ensembles. A kind of musical family tree in a way…

Jean Buzelin & Patrick Frémeaux

In summer 1936, when the young Orlandus Wilson (born in 1917) joined the vocal group formed in 1930 by Eddie Griffin, Henry Owens, Willie Johnson and Robert Ford, it had been known since 1934 as the Golden Gate Jubilee Singers. A year previously William Langford had replaced Griffin as first tenor who took over bass in place of Ford. Based in Norfolk, Virginia, the quartet was now led by baritone Willie “Bill” Johnson, arranger and lead vocalist who adopted a new rhythmic narrative style of expression, the old preacher style adapted to the quartet’s vocal harmonising, which would have a huge influence on Afro-American vocal art. With the Gates the term “jubilee”, that originated with harmonising groups formed in high schools during the emancipation era, would henceforth be used to denote a new genre of spiritual quartets whose music was based not only on syncopation but also on jazz rhythms and swing. In spite of some reticence on the part of several church leaders who found their obvious debt to the secular Mills Brothers more than a little disturbing, from 1935 on the group began to sing in churches in neighbouring towns such as Richmond and Tidewater. And, in 1936, they toured South Carolina for the first time, also appearing on the local WIS radio network in Columbia. Their popularity increased even more in 1937 after they were featured several times on NBC’s “Magic Key Hour” that had national coverage.

In August 1937, when the four singers were in Charlotte, North Carolina, they were invited to a recording session in a hotel where the Victor Record Company had set up its mobile studio equipment. Fourteen titles were recorded within a couple of hours and the first Bluebird records of the Golden Gate Jubilee Quartet appeared on the market. Golden Gate Gospel Train was an immediate hit and the Gates, now settled in Charlotte, were soon appearing daily on a WBT radio programme, a station that in 1938 covered five or six states, from the East Coast to Georgia and Tennessee. A second marathon session in the Charlotte Hotel was organised in January 1938, before the group was invited to the New York permanent studios in August and November of the same year. Then, in February 1939, while their reputation continued to grow in and around Charlotte, which was still their base, they took part in another hotel session, this time in Rock Hill, South Carolina, before returning to the New York studios in October. Throughout this period, under its Bluebird label, Victor issued a record every month by the Golden Gate Jubilee Quartet! Next, CBS radio asked them to compere a daily programme. Not long after, at the request of the organisers, they dropped the word Jubilee from their name to become, on radio, on record and in public, the Golden Gate Quartet.

It was under this name that they appeared on stage at the Carnegie Hall on 24 December 1939 in the second “From Spirituals to Swing” concert organised by critic and talent scout John Hammond (4). After the concert Hammond took them, along with Big Bill Broonzy and Ida Cox who had shared the billing, to the Café Society, New York’s first multi-racial club, popular with the trendy crowd and liberal minded intellectuals. Each of them was asked to sing something but it was the Gates that brought the house down! So much so that manager Barney Josephson hired them on the spot with a six months’ contract. Two days later they did a further session for Bluebird on the eve of their debut at the Café Society. Although the quartet sang a cappella each evening at the club, Columbia’s manager asked them to sing on radio with a guitar backing. They had already widened their repertoire, originally composed of Negro spirituals, to include a few standards and pop songs with William Langford on guitar. This was certainly because record producers wanted the Gates to be in a position to rival the Mills Brothers and especially the Ink Spots, n°1 in the American hit parade.

However, it was with a completely different repertoire based on Negro work songs that the Golden Gate Quartet, plus Clyde Riddick, accompanied the veteran bluesman Leadbelly for a final Victor/Bluebird session in June 1940. Henceforth, already hired by Columbia as a result of their radio broadcasts the group would record for this company from April and May 1941. The preceding January, they had taken part in President Roosevelt’s inauguration ceremony at Constitution Hall. It seems the President’s wife had heard them play at the Café Society and the Gates were probably the first black entertainers to be invited to the White House (5). The same year they went on tour in Mexico before going to Hollywood where they appeared in several films: “Star-Spangled Rhythm”, “Hollywood Canteen”, “Bring on the Girls” and “Hit Parade of 1943”, followed later by “Change of Hearts”.

In addition to the commercial sides they cut for OKeh/Columbia at this time, there are several radio transcripts (for General Electric, NBC, AFS-Jubilee). This period saw the start of the long drawn out recording strike called by the unions and it was also the moment that the U.S. entered the war. The Golden Gate Quartet made a V-disc destined for American troops at the front.

This time of upheaval, although prolific for the group, saw some personnel changes. William Langford, their high tenor with such enormous stage presence (his range covered falsetto to baritone) left towards the end of 1940 to join the Southern Sons.

Formed in 1935 in Newark, New Jersey, influenced by both the Mills Brothers and the Golden Gates, the Southern Sons were already well known in the area. The arrival of Langford, however, quickly enhanced the group’s reputation. He became their manager and got them a contract with Bluebird, the same label as the Golden Gate Quartet! They started recording in 1941 and had a great hit the following year with Praise The Lord And Pass The Ammunition. They toured the South in 1942 and appeared regularly on a radio show transmitted by WBT in Charlotte (where the Gates had started out). After the premature death of their leader and guitarist, James Baxter, Langford and bass Clifford Givens left the group which, a short time later, stopped recording.

Then William Langford joined the Selah Jubilee Singers where he stayed for several years before forming the Landfordaires who would make several records in 1949, then the Bill Langford Quartet. He later became a disc jockey for religious music in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, before his death in 1969.

Naturally, Clyde Riddick took over the role of first tenor. Connected with the group since the very beginning, he had briefly replaced Eddie Griffin before Langford arrived. Apart from the odd temporary replacement, it was the new quartet Riddick-Owens-Johnson-Wilson that made the OKeh records in the early 40s, occasionally with guitar accompaniment. There is little doubt that it was Abe Green who played with the Gates for about fifteen months in 1942 and 43 before being drafted into the army. When he was demobbed he spent about nine months with the Jubalaires before rejoining the Dixieaires whom he left around 1950/51.

In 1943, in spite of the recording ban, the Golden Gate Quartet recorded a topical piece written by Willie Johnson Stalin Wasn’t Stallin’ (an adaptation of Preacher And The Bear) which created quite a stir on the race record market, soon to become known as Rhythm & Blues.

1943 was also the year when Willie Johnson received his draft papers, as did Orlandus Wilson a short time after. The former was briefly replaced by Joseph E. Johnson who would later form the Trumpeteers, then by Alton Bradley, previously lead vocal with the Silver Echo Quartet and who had already been an influential figure in the group. The latter was replaced by Clifford Givens, one of the greatest bass voices ever heard in vocal quartets.

Like the Southern Sons, the Silver Echo Quartet was also well known around Newark and were in direct competition with them. They presented a radio programme in Patterson, New Jersey and did a month’s tour with the Woody Herman orchestra. They made several records in 1943 and 1944, until Alton Bradley left them. They survived a few more years but it wasn’t easy.

Born in Newark, New Jersey, in 1918, Clifford Givens had been singing since 1935 with the Southern Sons and was the first to reproduce a vocal rendition of the throbbing “boom, boom, boom” sound of the double bass into religious music (although John Mills had already attempted this type of imitation). After having left the Southern Sons to replace for a while Hoppy Jones, the famous Ink Spots bass who had just died, Clifford Givens took over when Orlandus Wilson was drafted into the US Navy. Wilson’s perfect timing, innate sense of exactly where a note should go, his throaty, gravelly, deep voice is in sharp contrast to Givens warm, round tone and more instinctive, improvised approach: two very different examples of the bass role. The overall style of the quartet changed very little, especially as soloist Bradley was not a “narrator’ like Johnson. Contrary to what discographies usually indicate, Clifford Givens did not participate in any commercial recording, but he can be heard on several radio trasncriptions e.q. Straighten Up And Fly Right, the Nat King Cole hit. In addition, following the example of numerous pop quartets, the Gates replaced the guitar by the piano and hired Conrad Frederik.

In June 1946, the reformed quartet with Johnson and Wilson cut a memorable session for Columbia, backed by a jazz rhythm section, that embodied the best of their work. Among the eight sides recorded, it is perhaps Shadrack that remains their greatest hit but most of the titles would appear on their first 10 inch 33 r.p.m. which came out the following year aimed at a new white market. These new vinyl records, along with tape recorders, formed part of a new technique that appeared to have a promising future. 1947 also saw the return of the Gates to Hollywood to take part in radio broadcasts but, more importantly, to appear, alongside Louis Armstrong, Benny Goodman, Lionel Hampton, Tommy Dorsey, Charlie Barnet and Mel Powell, in Sam Goldwin’s feature film “A Song is Born” starring Danny Kaye.

In spring 1948, the Gates lost their principal soloist Willie Johnson who left them to change places with Orville Brooks (born in 1919 in Maryland) in the Jubalaires, a group with which he had already been working for some time.

J.C. Ginyard had brought the Jubalaires, originally known as the Royal Harmony Singers, together in Jacksonville, Florida, in 1936. They moved to Philadelphia in 1941 where they cut two records and then changed their name and, in 1944, replaced the Golden Gate Quartet at the Café Society. Not only in great demand on the radio (with a regular programme on CBS), but also for “soundies” (short juke box films), the Jubalaires had a hit in 1946 with I Know, accompanied by Andy Kirk’s big band. As a result they went on a nation-wide tour with Andy Kirk before settling in California where they appeared in several shows and in the film “The Joint Is Jumping” with an all black cast. After the arrival of Willie Johnson, J.C. Ginyard left the group to form, with two singers from the Silver Echo Quartet, then on the decline, a new pop/jubilee quartet, the Dixieaires. For many years Willie Johnson remained the leader of the Jubalaires, who later changed their name to the Jubilee Four – they appeared in the film “Viva Las Vegas” with Elvis Presley – before he died in the early 80s.

Although the Dixieaires’ existence was a fruitful one, it was fairly short-lived, but they did manage to make quite a few successful records. Formed in New York in 1947, they became the Jubalaires’ strongest rivals – Ginyard had brought with him some of his old group’s material – and recorded numerous records in a highly rhythmic narrative style between 1947 and 1951, even having a moderate hit with Go Long in 1948, and made several tours throughout the country.

1948 saw the end of the Golden Gate Quartet’s contract with Columbia and they moved over to Mercury where several sessions took place the following year. While still maintaining the jubilee style they had reinvented in the late 30s, the Gates could not ignore the changes that had taken place in the post-war musical world. Not only did they now include instrumental accompanists, they also added certain modern touches to their interpretations and repertoire. Hence, Talking Jerusalem To Death includes a different recitative and Jesus Met The Woman At The Well is a Gospel song written by James W. Alexander for the Pilgrim Travelers (6) who recorded it the same month. The piece has a stronger rhythmic beat and the choir sings in unison, rare for the jubilee style but current in the new quartets. The decline in popularity of pop groups like the Mills Brothers, the Ink Spots, the Charioteers, the Deep River Boys etc. also persuaded them to drop the secular aspect of what was becoming a dated repertoire. Finally, they were faced with tough competition from groups they had inspired, who had copied them and had often made cover versions, particularly those that ex-Gates brought with them! Thus the Silver Echo reprised Jezebel, Anyhow…, the Selah Gospel Train…, the Jubalaires I’m On My Way, The Valley Of Time…, the Landfordaires Run On…, the Dixieaires You Better Run, My Lord Is Writing etc. In spite of this, their old Bluebird records are still being reissued by Victor, proving that they still sell.

In 1950, Henry Owens, the oldest member of the Gates since he was one of the four founders of the quartet in 1930, left the group to become a Baptist preacher. Second tenor and occasionally lead vocal, he brought a Gospel feeling to the ensemble. He had a great sense of harmony and fitted in perfectly between the first tenor and baritone. Specialists consider him to have had the purest voice in the Golden Gate Quartet. He died in 1970. Alton Bradley then moved from baritone to tenor and the quartet again numbered four. It was this formation that recorded a rare and superb session of Negro spirituals that make up late a Concert Hall album. Their varied interpretations range from their old traditional style to a more modern Gospel treatment Two Wings, with an astounding version of Amazing Grace including a lead vocal that is almost hard!

Their producer Bob Shad had left Mercury to set up his own label, Sittin’ In With, taking with him tapes of the records the Gates had made previously. He issued these under his new label between the end of December 1950 and spring 1951 (7). This meant that the Gates had no contractual obligations so they returned to Columbia. Henry Owens returned to the studios with them for a first session in November 1950.

But a page was in the process of being turned for the recording industry seemed to have lost interest in the jubilee style. The Dixieaires broke up and, in 1952, J.C. Ginyard rejoined the Du-Droppers who were inclined more towards rhythm and blues. Clifford Givens reformed the new Southern Sons in Little Rock, Arkansas, a much cruder ensemble, harking back to Southern Gospel groups such as the Spirit of Memphis Quartet. But success proved elusive and, after an excellent series of recordings between 1950 and 1953, Givens rejoined the R&B stars, the Dominoes. After moving to Los Angeles at the end of the 50s, he worked as a soloist, lending his exceptional voice to the studios with a variety of singers and groups. He died in 1989.

Although not as popular as the Gates, the Selah Jubilee Singers did not do too badly. They were well known and able to take advantage of their excellent reputation. They provided the choral backing for Mahalia Jackson both on record (8) and often in concert (9). As the Selah Jubilee Six the group had been founded as early as 1927 in Brooklyn by Thurman (or Thermon) Ruth and in 1931 had taken part in a recording session that was never issued. Until the early 40s the group appeared regularly in churches around Brooklyn and Harlem, before touring the East Coast, even going as far as Texas. They recorded abundantly from 1939 and reached the “Top 40” in 1941 with I Feel Like My Time Ain’t Long. Rooted in a strong tradition, they had always adhered to a natural form of expression and so it was easy for them to adapt to the style of more modern Gospel quartets. In addition, changing their name as often as they did their recording companies, they were able to satisfy public demand with a range going from Negro spirituals and Gospel Songs when they were known as the Selah Jubilee Quartet, the Sons of Heaven, the Jubilators and the Southern Harmonaires, to rhythm and blues when they became the Four Barons, the Cleartones and, above all the Larks, achieving a certain success. In spite of a recording gap from 1950 to 1955 the Selah enjoyed a long career.

In 1951, the Gates welcomed Eugene Mumford in place of Alton Bradley. This flexible tenor, able to modulate his voice, had just left the Selah Singers. Although he stayed with the Gates for several years he is heard in solo just once on the only side OKeh issued after the group’s final American session, I Just Telephone Upstairs. He later teamed up with the Dominoes and made a career in non-religious music.

With Herman Flintall installed at the keyboard instead of Conrad Frederick, so ends discographic story of the Golden Gate Quartet in the United States. The musical and commercial evolution, favouring cruder, more unbridled and spectacular forms of expression (e.g. hard gospel quartets) or, on the other hand, sweetly sentimental interpretations (doo-wop vocal groups), left little room for jubilee quartets, in particular the Golden Gate Quartet although it was without doubt a definite precursor of rhythm and blues that would engender rock ’n’ roll. However, the group still continued to perform. There were two personnel changes in 1954 with the arrival of baritone Bill Bing to replace Orville Brooks who left to join the Larks and, above all tenor Clyde Wright (born in 1928) from Charlotte who replaced Mumford, whom he had previously replaced with the Selah Singers. Fifty years on, after a few comings-and-goings, Wright remained the spearhead of the Golden Gate Quartet (9). Fifty years later after several comings-and-goings, Wright remained the stearhead of the illustrious formation (2)(3). Bill Bing would soon be replaced by Frank Todd who, in turn, gave up his role in 1956 to J. C. Ginyard. Born in 1910 in South Carolina, Junior Caleb Ginyard had already enjoyed a successful career with several of the above-mentioned groups (Jubalaires, Dixieaires, and Du-Droppers). He caught up with the Golden Gate Quartet when they were already in Europe. For fifteen years, this accomplished singer assumed the narrative solo role created by Willie Johnson, one which none of his successors had ever really taken up before. Ginyard left the group for health reasons in 1971. He retired to Basle where he worked as a soloist and died in 1978.

The Golden Gate Quartet now went on to pursue their career outside the United States. After a Canadian tour, they took off for Europe and, half a century later, are still here… In November 1955 the quartet, comprising Riddick, Wright, Todd and Wilson, with their pianist Irwin Trottman, appeared at the Paris Olympia. That same month, under the auspices of Jean-Paul Guiter, Pathé-Marconi’s artistic director, they cut several 78s issued under the Columbia label (owned by Pathé). Interspersed with periodic trips back to the States, the group undertook numerous triumphal tours throughout Europe, recording in Paris, London (in 1956), Berlin (in 1957) accompanied by their new pianist Glenn Burgess and some of the best French jazz musicians. In 1958 the American State Department sponsored a tour that took them via Greece through twenty-eight countries in the Middle and Far East. In 1959 the Gates signed a two-year contract with the Casino de Paris, making their debut in “Plaisir”, a revue starring Line Renaud (Clyde Wright tells the story of the night Elvis Presley came to hear them (2). Now permanently settled in Paris, they recorded regularly for Columbia/Pathé until 1969, at the same time continuing to give concerts in the four corners of the world, including another US State Department sponsored tour through twenty-six African countries.

In 1971, Orlandus Wilson’s great nephew Paul Brembly and Calvin Williams replaced respectively J.C. Ginyard and Clyde Wright. Among the records they continued to make regularly, particularly for the Ibach label, the “Jubilee” album from 1980 stands out as a celebration of a career that had lasted twenty-five years both in Europe and throughout the world. 1984 saw the return of Clyde Wright who stayed with the group for a decade before making way for Charles West. Frank Davis then replaced Clyde Riddick who, at the end of 1994 decided to retire at the age of 81, before his death five years later on 9 October 1999. Also in 1994, the “United Group in Harmony Association” honoured the Golden Gate Quartet with a place in its “Hall of Fame”. The ceremony was accompanied by concerts and radio and TV broadcasts. Finally the time came for Orlandus Wilson, leader and arranger of the group since the Second World War and who had never sung with any other group, to retire. But, before his death on 31 December 1998, he had already designated his successor in the person of a young Martinique singer Terry François. A choice that reflects the universality that the Golden Gate Quartet had achieved.

The ten years covered by this CD are not necessarily the best known of their career. However, not only are they are packed full of magnificent interpretations revealing a striving towards a perfection that few musicians have ever attained but they also express black vocal American art at its most natural. This almost magical combination is what made the Golden Great Quartet what it is and why it still reaches out to all of us after more than 70 years.

Adapted from the French text of Jean Buzelin by Joyce Waterhouse

Jean Buzelin, author of Negro Spirituals & Gospel Songs, Chants d’espoir et de liberté (Ed. du Layeur/Notre Histoire, Paris 1998)

© FRÉMEAUX & ASSOCIÉS/GROUPE FRÉMEAUX COLOMBINI SA, 2004

Our first volume gave wider coverage to the role played by the Golden Gate Quartet in the history of vocal quartets, to the originality of its music and the contents of its repertoire, based essentially on traditional Negro spirituals. References to these earlier chapters are contained in the following notes.

Notes:

(1) Golden Gate Quartet/Gospel 1937-1941 (FA 002)

(2) See The Golden Gate Quartet/Made in Raleigh (FA 452)

(3) See The Golden Gate Quartet & The Good Book (FA465)

(4) And not, as we mistakenly noted in our first volume (FA 002) and as most historical and biographical texts indicate at the first concert on 23 December 1938; confirmed by the recent issue of the definitive boxed set of From Spirituals to Swing (Vanguard 169-2)

(5) In spite of Eleanor Roosevelt’s support, Marian Anderson was refused an audience in 1939, which created a scandal

(6) The Pilgrim Travelers had made their recording debut copying some of the titles sung by the Gates; they later became one of the best modern Gospel quartets

(7) It is impossible to establish the exact dates of these recordings for they have SIW matrix numbers, not Mercury i.e. later than the session

(8) In particular on the original In The Upper Room; see Complete Mahalia Jackson Vol. 1 (FA 1313)

(9) Clyde Wright, when he was a member of the Selah, remembers having provided a choral backing for Mahalia Jackson and Sister Rosetta Tharpe and having sung and recorded with the Selah in 1949 (cf. CD2 H19 for which he gives a different personnel to that of the discography)

Texts consulted: sleeve notes by Billy Altman, Christian Bonneau, Paul Brembly, Jacques Demêtre, Ray Funk, Peter A. Grendysa, Daniel Nevers, Orlandus Wilson, Clyde Wright, and Cedric J. Hayes & Robert Laughton, Gospel Records (RIS, 1993).

With grateful thanks to François-Xavier Moulé, Etienne Peltier and Robert Sacré for the loan of their rare 78s, to Yvan Amar, Jacques Demêtre and Clyde Wright.

Discographie CD1

01. MOSES SMOTE THE WATERS (Trad. - arr. O. Wilson) 31851-1 2’32

02. HANDWRITTING ON THE WALL (Trad. - arr. O. Wilson) 31852 2’05

03. (YOU BETTER) RUN ON (Trad. - arr. O. Wilson) 32620 2’42

04. MY TIME DONE COME (W. Johnson) 32623-1 2’44

05. STALIN WAS NOT STALLIN’ (W. Johnson) 33183-1 3’09

06. STRAIGHTEN UP AND FLY RIGHT (N. Cole - I. Mills) Jubilee 91 (Trad. - arr. Golden Gate Quartet) 4426-1 2’23

07. BONES, BONES, BONES (EZEKIEL IN THE VALLEY) (Trad. - arr. Golden Gate Quartet) 4426-1 2’54

08. SWING DOWN, CHARIOT (Trad. - arr. Golden Gate Quartet) 36387-1 3’35

09. ATOM AND EVIL (H. Zaret - L. Singer) 36389-1 3’25

10. SHADRACK (R. McGimsey - arr. O. Wilson) 36390-1 2’40

11. HUSH ! (SOMEBODY’S CALLING YOUR NAME) (Trad. - arr. Golden Gate Quartet) 36391-1 3’16

12. JOSHUA FIT DE BATTLE OF JERICHO (Trad. - arr. Golden Gate Quartet) 36392-1 2’42

13. PRAY FOR THE LIGHTS TO GO OUT (R. Tunnah - W.E. Skidmore) 37601-1 3’05

14. TALKING JERUSALEM TO DEATH (Trad. - arr. O. Wilson) 2140 2’46

15. JESUS MET THE WOMAN AT THE WELL (J.W. Alexander) 2164 2’57

16. JEZEBEL (Trad. - arr. W. Johnson) S-1065 2’29

17. LORD HAVE MERCY (Trad. - arr. C.W. Hill) D4-AB-57-1 3’01

18. I’M ON MY WAY (Trad.) 72859AA 3’00

19. THERE ‘LL BE A JUBILEE (Unknown) W 3317 2’50

20. RUN ON FOR A LONG TIME (Trad. - arr. Golden Gate Quartet) CO42504-1 2’38

Golden Gate Quartet :

(1-2) Henry Owens, Clyde Riddick (tenor voc), Willie “Bill“ Johnson (baritone, lead voc), Orlandus Wilson (bass voc), unknown (drums on 2). New York City, December 3, 1941.

(3-4) Same ; prob. Abe Green (guitar). NYC, March 25, 1942.

(5) Same ; guitar out. NYC, March 5, 1943.

(6) Henry Owens, Clyde Riddick (tenor voc), Alton Bradley (baritone voc), Clifford Givens (bass voc), Conrad Frederick (piano). Hollywood, ca. June, 1944.

(7) Same, but Orlandus Wilson (bass voc), replaces Givens. Chicago, March 16, 1945.

(8-12) Henry Owens, Clyde Riddick (tenor voc), Willie Johnson (baritone voc), Orlandus Wilson (bass voc), Conrad Frederick (piano), Al Hall (bass), James Crawford (drums). NYC, June 5, 1946.

(13) Same or similar ; guitar added. NYC, April 8, 1947.

(14) Same, but Orville Brooks (baritone voc) replaces Johnson ; guitar out. NYC, late December, 1948.

(15) Clyde Riddick, Alton Bradley (tenor voc), Orville Brooks (baritone voc), Orlandus Wilson (bass voc), Conrad Frederick (piano). NYC, January, 1949.

(16) Silver Echo Quartet : Alton Bradley (lead voc), Jimmy Smith (tenor voc), Douglas Ward (baritone voc), Bill Reeves (bass voc), unknown (guitar). Prob. Newark, NJ, January, 1943.

(17) Southern Sons : James “Kissler” Baxter (1st tenor, lead voc), William Langford (2nd tenor voc), Charles Wesley Hill (baritone voc), Clifford Givens (bass, 2nd lead voc). February 23, 1944.

(18) Jubalaires : J. Caleb Ginyard (lead voc), John Jennings (tenor voc), Orville Brooks, Theodore Brooks (baritone voc), George McFadden (bass voc), Willie Johnson (guitar), unknown (piano and bass). NYC, May 14, 1945.

(19) Selah Jubilee Quartet : Thermon Ruth (tenor, lead voc), William Langford (tenor voc, guitar), Theodore Harris (baritone voc), Jimmy Gorham (bass voc). Los Angeles, Spring 1945.

(20) Bill Landford & The Landfordaires : William Langford (tenor voc, guitar), unknown male vocal group. NYC, December 15, 1949.

Discographie CD2

01. JOHN SAW THE WHEEL (Trad. - arr. O. Wilson) 2763 2’48

02. LORD, I AM TIRED AND I WANT TO GO HOME (Trad. O. Wilson) 2764 3’04

03. LORD, I WANT TO BE A CHRISTIAN (Trad. - arr. O. Wilson) 2766 2’55

04. RELIGION IS A FORTUNE (Trad. - arr. O. Wilson) 2859 2’38

05. WHEN THE MOON GOES DOWN (Trad. - arr. O. Wilson) 2’27

06. DOWNWARD ROAD (Trad. - arr. O. Wilson) 2’32

07. AMAZING GRACE (J. Newton - arr. O. Wilson) 3’08

08. THIS WHOLE WORLD (IS IN A BAD CONDITION) (Trad. - arr. O. Wilson) 3’27

09. HOLD ON (Trad. - arr. O. Wilson) 3’36

10. GIVE ME TWO WINGS (Trad. - arr. O. Wison) 2’49

11. THERE’S A MAN GOING ROUND TAKING NAMES (Trad.) 2991 2’34

12. SAME TRAIN (Trad. - arr. O. Wilson) 2994 2’26

13. YOU’D BETTER MIND (Trad. - arr. O. Wilson) C2324 2’28

14. LISTEN TO THE LAMBS (Trad. - arr. O. Wilson) 5087 2’53

15. I JUST TELEPHONE UPSTAIRS (Trad. - arr. O. Wilson) 47724 2’44

16. LIVE-A-HUMBLE (Trad.) SRR-1288 2’32

17. JOE LOUIS IS A FIGHTIN’ MAN (J.C. Ginyard) C2080 3’00

18. NEW BORN AGAIN (Trad.) BG3 2’30

19. SORROW VALLEY (A. Bunn) 5005 2’50

20. HONEY ON THE ROCK (Graves) C2415 2’40

Golden Gate Quartet :

(1-3) Henry Owens, Clyde Riddick (tenor voc), Alton Bradley, Orville Brooks (baritone voc), Orlandus Wilson (bass voc), poss. Conrad Frederick (piano), unknown (bass and percussion on 1, 2). NYC, April, 1949.

(4) Same ; bass and percussion out. NYC, July, 1949.

(5-10) Clyde Riddick, Alton Bradley (tenor voc), Orville Brooks (baritone voc), Orlandus Wilson (bass voc), Conrad Frederick (piano). ca.1949/50.

(11-12) Same. NYC, January, 1950.

(13) Prob. same. NYC, ca. 1949/50.

(14) Same ; Henry Owens (tenor voc) added ; poss. Herman Flintall (piano). NYC, November 29, 1950.

(15) Clyde Riddick, Eugene Mumford (tenor voc), Orville Brooks (baritone voc), Orlandus Wilson (bass voc), unknown (el.guitar)(bass)(drums) cond. by Herman Flintall. NYC, March 13, 1952.

(16) Jubalaires (prob. pers.) : Willie Johnson (lead voc), John Jennings, unknown (tenor voc), Theodore Brooks (baritone voc), George McFadden (bass voc), unknown (piano). ca. 1948.

(17) Dixieaires : J. Caleb Ginyard (lead voc), Jimmy Smith (tenor voc), Joseph Floyd (baritone voc), Thomas “Johnny“ Hines (bass voc), unknown (piano and drums). ca. April/May, 1950.

(18) Southern Sons Quartette : James E. Walker (tenor, lead voc), David C. Smith, Roscoe Robinson (tenor voc), Earl Ratliff, Clarence Hopkins (baritone voc), Clifford C. Givens (bass voc). Jackson, MS, early/mid November, 1950.

(19) Selah Singers : Napoleon “Nappy” Brown (1st lead voc), Clyde Wright (tenor 2nd lead voc, guitar). Junius Parker (tenor voc), Melvin Colden (baritone voc), Jerry Gorham (bass voc). NYC, ca. 1949.

(20) Larks (Southern Harmonaires) : Eugene Mumford (tenor, lead voc), Alle Bunn (tenor, lead voc, guitar), Thermon Ruth (tenor voc), Hadie Rowe Jr, Raymond “Pee Wee” Barnes (baritone voc), David McNeil (bass voc). NYC, November 30, 1950.

Pour les 70 ans d’une institution majeure de l’art vocal afro-américain, toujours en pleine vie et qui se régénère sans cesse, ce retour aux sources montre que, durant ces dix années chargées d’histoire, le Golden Gate Quartet avait déjà rejoint les cimes de la musique sacrée.

To celebrate the 70 years existence of a major Afro-American vocal institution, still going strong and continually renewing itself, this trip back in time shows that, during these ten years packed full of history, the Golden Gate Quartet had already scaled the heights of religious music.