- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

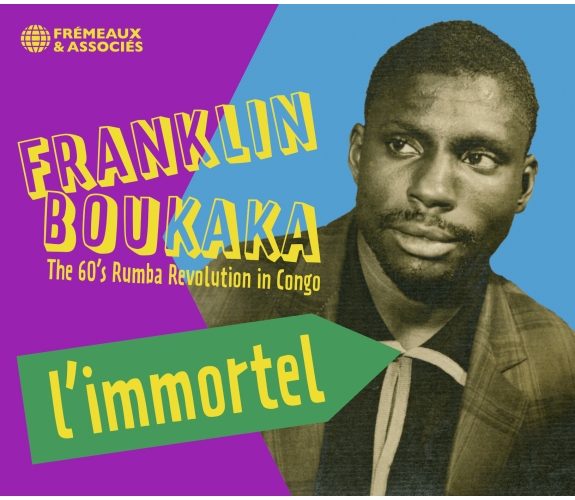

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

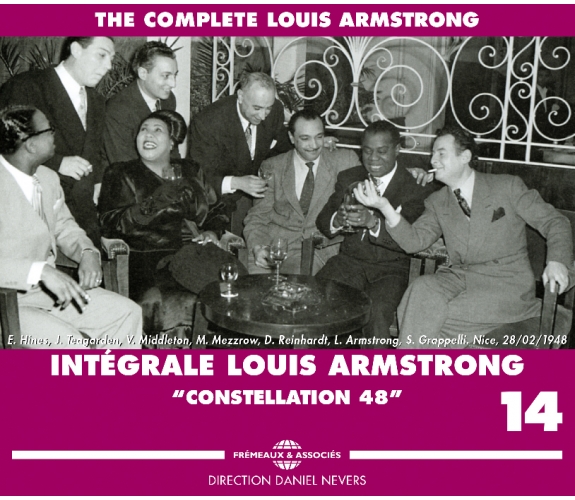

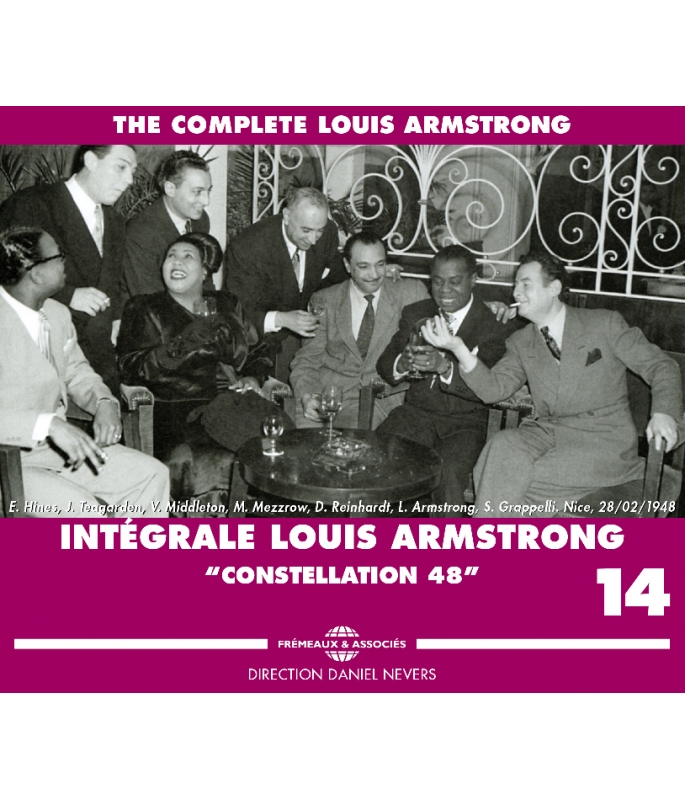

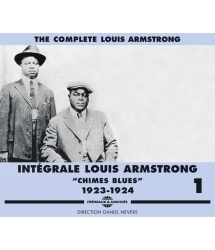

CONSTELLATION 48

LOUIS ARMSTRONG

Ref.: FA1364

Artistic Direction : DANIEL NEVERS

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Total duration of the pack : 3 hours 49 minutes

Nbre. CD : 3

CONSTELLATION 48

CONSTELLATION 48

“I like to say a few words, ha !... Ladies and gentlemen, I have the great pleasure to… telling you how much my boys and I have enjoyed our stay here in Nice… And I think this festival should become an institution, so that we can come back to your beautiful country every year. Thank you very very much…”. Louis ARMSTRONG, Nice (France), 28/02/1948

PUBLIC MELODY N°1 - 1937-1938

A SONG WAS BORN - 1947

CHIMES BLUES 1923-1924

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1A Song Was BornLouis Armstrong And The All-StarsG. Depaul00:03:211947

-

2Please Stop Playing Those BluesLouis Armstrong And The All-StarsDemetrius00:03:181947

-

3Before LongLouis Armstrong And The All-StarsC. Sigman00:02:541947

-

4Lovely Wheather We're HavingLouis Armstrong And The All-StarsJ. Devries00:03:191947

-

5Intro Back O' Town BluesLouis Armstrong And The All-StarsLouis Armstrong00:05:531947

-

6Body And SoulLouis Armstrong And The All-StarsSour00:06:081947

-

7Stars Fell On AlabamaLouis Armstrong And The All-StarsPerkins.00:05:351947

-

8High SocietyLouis Armstrong And The All-StarsP. Steele00:04:101947

-

9Basin Street BluesLouis Armstrong And The All-StarsP. Steele00:04:371947

-

10Rockin' ChairLouis Armstrong And The All-StarsH. Carmichael00:05:071947

-

11I Gotta Right To Sing The BluesLouis Armstrong And The All-StarsT. Koehler00:01:421947

-

12Duplex entre l'aéroport de New York et Le Vol Air France ConstellationRoger GoupillèreRoger Goupillère00:03:311948

-

13Duplex entre l'aéroport de New York et Le Vol Air France Constellation IILouis ArmstrongRoger Goupillère00:02:451948

-

14Arrivée à OrlyLouis Armstrong00:02:491948

-

15Festival International de Jazz de Nice - OuvertureGilles CazeneuveGilles Cazeneuve00:03:351948

-

16Muskrat RambleLouis Armstrong et son Hot Five00:01:511948

-

17Rockin' ChairLouis Armstrong et son Hot Five00:02:461948

-

18Boogie Woogie On The St Louis BluesLouis Armstrong et son Hot Five00:03:141948

-

19Rose RoomLouis Armstrong et son Hot FiveA. Hickman00:03:401948

-

20I Gotta Right To Sing The BluesLouis Armstrong et son Hot FiveT. Koehler00:03:101948

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1When It's Sleepy Time Down SouthLouis Armstrong et son Hot FiveC. Muse00:04:111948

-

2Mahogany Hall StompLouis Armstrong et son Hot FiveSp. Williams00:03:351948

-

3Royal Garden BluesLouis Armstrong et son Hot FiveC. Sp. Williams00:05:091948

-

4Them There EyesLouis Armstrong et son Hot Five00:04:221948

-

5PanamaLouis Armstrong et son Hot Five00:04:221948

-

6On The Sunny Side Of The StreetLouis Armstrong et son Hot FiveD. Fields00:06:491948

-

7Black And BlueLouis Armstrong et son Hot FiveFats Waller00:03:501948

-

8Dear Old SouthlandLouis Armstrong et son Hot FiveH. Creamer00:03:491948

-

9Royal Garden BluesLouis Armstrong et son Hot FiveC. Sp. Williams00:04:471948

-

10My Monday DateLouis Armstrong et son Hot FiveE. Hines00:06:321948

-

11When The Saints Go Marchin InLouis Armstrong et son Hot FiveTraditionnel00:03:101948

-

12That's My DesireLouis Armstrong et son Hot FiveCarroll Loveday00:04:191948

-

13I Cried Last NightLouis Armstrong et son Hot FiveLouis Armstrong00:03:341948

-

14Présentation/Steak FaceLouis Armstrong et son Hot FiveTraditionnel00:06:021948

-

15Ain'T MisbehavinLouis Armstrong et son Hot FiveA. Razaf00:02:511948

-

16I Cried For YouLouis Armstrong et son Hot FiveG. Arnheim00:04:391948

-

17Boogie Woogie On The St Louis BluesLouis Armstrong et son Hot FiveW.C. Handy00:04:391948

-

18On The Nice International Festival By Louis ArmstrongLouis ArmstrongLouis Armstrong00:00:381948

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Dear Old SouthlandLouis Armstrong et son Hot FiveH. Creamer00:03:511948

-

2Black And BlueLouis Armstrong et son Hot FiveFats Waller00:04:131948

-

3Royal Garden BluesLouis Armstrong et son Hot FiveC. Sp. Williams00:05:071948

-

4You Rascal YouLouis Armstrong et son Hot FiveS. Theard00:04:271948

-

5How High Is The MoonLouis Armstrong et son Hot FiveN. Lewis00:05:081948

-

6Someone To Watch Over MeLouis Armstrong et son Hot FiveG. And I. Gerschwin00:02:501948

-

7Honeysuckle RoseLouis Armstrong et son Hot FiveFats Waller00:02:471948

-

8Back O' Town BluesLouis Armstrong et son Hot FiveLouis Armstrong00:04:481948

-

9Steack FaceLouis Armstrong et son Hot FiveTraditionnel00:07:001948

-

10When It's Sleepy Time Down SouthLouis Armstrong et son Hot FiveC. Muse00:01:071948

-

11Mahogany Hall StompLouis Armstrong et son Hot FiveSp. Williams00:03:451948

-

12On The Sunny Side Of The StreetLouis Armstrong et son Hot FiveD. Fields00:06:501948

-

13High SocietyLouis Armstrong et son Hot FiveP. Steele00:03:381948

-

14Basin Street BluesLouis Armstrong et son Hot FiveSp. Williams00:03:501948

-

15Baby Won T Please Comme HomeLouis Armstrong et son Hot FiveC. Warfield00:02:471948

-

16I Cried Last NightLouis Armstrong et son Hot FiveLouis Armstrong00:05:351948

-

17That's My DesireLouis Armstrong et son Hot FiveCarroll Loveday00:04:451948

-

18Muskrat RumbleLouis Armstrong et son Hot FiveEd Ory00:05:491948

Intégrale Louis Armstrong volume 14 FA1364

THE COMPLETE LOUIS ARMSTRONG 14

INTÉGRALE LOUIS ARMSTRONG 14

“constellation 48”

DIRECTION DANIEL NEVERS

Louis ARMSTRONG – volume 14

Afin de ne pas tronçonner le concert donné par le All-Stars le 30 novembre 1947 au « Symphony Hall » de Boston figurant sur le troisième disque du volume 13 (FA 1363), il fut décidé de reporter au début du recueil suivant les quatre titres provenant de l’ultime séance organisée chez RCA en date du 16 octobre. Voilà pourquoi ce nouveau volume, le quatorzième de l’« Intégrale », s’ouvre sur les pièces en question. Les deux premières, A Song Was Born et Please Stop Playing Those Blues, probablement les meilleures du lot, présentent d’excellentes interventions, à la fois instrumentales et chantées, de Louis et de son complice tranquille Teagarden. A Song Was Born en particulier sonne évidemment de manière fort différente que dans la version du film d’Howard Hawks dont il est issu, A Song Is Born, réalisé au cours de l’été précédent (voir volume 13 – Frémeaux FA-1363), mais toujours pas sorti. En fait, cette production de Samuel Goldwyn (oui, le « G » de la MGM, mais qui n’avait plus alors grand-chose à voir avec la firme au lion) ne sera finalement livrée aux spectateurs des salles obscures qu’à la toute fin de l’an 48… Problèmes de distribution malgré la belle affiche ? On ne sait. Toujours est-il que Louis et son gang n’inclurent qu’assez parcimonieusement l’aria à leur répertoire. Dommage.

Armstrong ne fit point de disques pour la vénérable Victor Talking Machine C° d’avant 1930 et n’entretint avec son repreneur RCA que des relations plutôt brèves : quelques mois de décembre 1932 à avril1933 (voir volume 6 – FA-1356), puis le contrat de 1946-47 se bouclant ici. On peut le regretter, car il n’avait pas été aussi superbement enregistré depuis longtemps… Il lui arriva bien, comme nombre de ses collègues, de fréquenter les studios RCA-NBC de la Côte Ouest pendant la guerre, afin de participer à l’effort militaire du pays en offrant une abondante série de gravures aux services de l’AFN et de l’AFRS (voir volumes 10 & 11 – FA-1360 & 1361), mais ce n’était pas tout à fait pareil. Surtout quand on songe à la longue durée des contrats qu’il remplit de 1925 à 1932 avec la firme OkeH (passée il est vrai dès 1927 sous le contrôle de Columbia), puis avec la maison Decca (1935-1946) de fondation récente… De toute façon, toute nouvelle signature se trouvera différée, du fait de la grève, moins longue et dure certes que celle de 1942-44, mais qui n’en paralysera pas moins, là encore, l’industrie phonographique étatsunienne pendant la majeure partie de 1948. Quelques boîtes parmi les plus jeunes comme Capitol, faisant taire la radinerie congénitale américaine, profitèrent de ce repos forcé pour s’équiper en nouvelles technologies, notamment celle consistant à enregistrer sur bande magnétique. Mais les anciennes se contentèrent d’attendre les jours meilleurs de 1950-51… Conséquence de tout cela pour Louis Armstrong et son All-Stars tout neuf (celui que l’on donne généralement comme le vrai premier et qui durera près de deux ans avant qu’interviennent les grosses modifications) : il n’enregistrera aucun disque à l’usage des détenteurs de phonographes.

Il est exact que le nom “All-Stars”̏, lancé au cours de l’été 47, figure déjà sur les Victor et affiliés du 16 octobre, mais lors de cette session et des concerts voisins (Carnegie Hall, Symphony Hall…), le pianiste est encore le gentil Dick Cary, si content de jouer dans la cour des Grands. Earl Hines ne fera son apparition – non pas comme à Lourdes, mais plutôt comme à Nice – qu’au début janvier 1948 (théoriquement pour cette seule année-là). A l’autre bout, soit fin avril 1950 seulement (Louis ayant entretemps fait quelques nouveaux disques, mais sans son groupe régulier), c’est Sidney Catlett, le batteur, qui aura cédé son poste à Cozy Cole pour raisons de santé. Heureusement, histoire d’apprécier cette équipe exceptionnelle, il nous reste bon nombre de concerts et d’émissions radio – les uns allant d’ailleurs assez logiquement de pair avec les autres… Si bien que, à l’exception des quatre faces RCA mentionnées ci-dessus, l’ensemble du présent recueil est composé d’enregistrements de concerts, plus ou moins « retransmis en direct » (comme ils disent), bons baisers d’ici ou d’ailleurs bien entendu.

Ici sans doute, « en direct » peut-être, à l’endroit de ces fragments du 15 novembre 47, remarquablement enregistrés et diffusés probablement depuis la scène du prestigieux Carnegie Hall. D’anciennes bio-discographies indiquent plutôt, le même soir, le Town Hall de New York, où un concert s’était effectivement déjà déroulé le 17 mai (qu’on avait d’ailleurs auparavant daté d’avril – voir volume 13). Il est sûr qu’il y eut bien un second Town Hall concert, mais la date ne nous en est point parvenue – non plus que la musique… L’excellente qualité du son nous incite à pencher pour l’établissement bâti à la demande du très sage et très fortuné Mister Carnegie. Il n’est pas impossible qu’il y ait eut en réalité deux concerts, le premier donné aux heures honnêtes, l’autre après minuit.

Le répertoire ayant déjà hélas tendance à se scléroser, afin d’éviter de doublonner avec la prestation du Symphony Hall bostonien quinze jours plus tard, il a paru opportun de ne pas inclure l’intégralité du (des) dit(s) concert(s), mais de n’en conserver que certains extraits, non repris le 30 novembre (Back O’Town Blues, Basin Street Blues, Rockin’ Chair, I Gotta Right to Sing the Blues), ou comportant d’intéressantes variantes aux accents parfois plus vigoureux (Body and Soul, Stars Fell on Alabama, High Society) qu’à la fin du mois…

La suite, ce sera ailleurs, sur l’autre rive de l’Atlantique. Direction Paris puis Nice, French Riviéra, où doit se tenir, du dimanche 22 au samedi 28 février 1948, le premier festival de jazz de l’Histoire… L’Âge d’Or des festivals, ces années 1950-60-70, n’en était encore qu’à ses balbutiements. Même le cinéma n’y avait qu’à peine eu droit : la vieille biennale de Venise, fasciste, déconsidérée, était dans les choux et Cannes, après la débâcle de septembre 39, avait enfin connu une première timide en 46 – non suivie d’une seconde l’année suivante. Le théâtre venait tout juste de localiser le chemin de la Cour d’Honneur du Palais des Papes. Quant au jazz… Depuis la fin des années 1920, il avait certes conquis droit de cité sur de belles et prestigieuses scènes des deux mondes, mais il s’agissait-là de concerts solitaires donnés par l’un ou l’autre musicien ou orchestre célèbres, mais en aucune façon de festivals s’étendant sur plusieurs jours, mêlant chefs du swing les plus réputés et inconnus débutants, prometteurs ou non. De plus, ces établissements (Carnegie Hall, Town Hall, Civic Auditorium de Chicago, Symphony Hall de Boston, Hollywood Bowl, London Palladium, Salles Pleyel et Gaveau, Châtelet…), appartenant pour la plupart au privé, pouvaient de ce fait être loués par tout un chacun possédant quelque menue monnaie et désireux de produire n’importe quel spectacle (y compris la redoutable Madame Florence Foster Jenkins !), sans qu’il soit obligatoire de se référer à un ensemble cohérent de manifestations. Situation assez peu propice au montage d’un festival… Pour cela il faut toute une organisation et des arrières solidement assurés, notamment dans la sphère publique ! Il faut jouer sur la durée (l’idéal : une semaine bien remplie), sur la multiplication des lieux où se déroulent les évènements, sur les horaires, sur un savant dosage entre célébrités et moins illustres…

Nice mit toutes les chances de son côté : Haut Patronage du Président de la République (qui fit offrir un vase de Sèvres à Louis Armstrong – non Stéphane, non ! Votre mémoire vous joue des tours : celui de 48 se prénommait Vincent, pas Albert !), du Ministère des Affaires étrangères et du Secrétariat d’Etat à la Présidence du Conseil et toutes les sommités locales. Deux lieux surtout furent affectés à la chose : l’Opéra et le Casino de Nice et, pour le bouquet final du 28, les salons de l’hôtel Negresco (aujourd’hui classé) : cinq mille balles l’entrée ! Et le trio Michel de Bry, Paul Gilson, Hugues Panassié vit ainsi se matérialiser un beau rêve. De Bry et Gilson s’assurèrent le soutien actif de la Radiodiffusion Française, relayée à son tour par celles de nombreuses jungles sauvages (parfois au-delà du rideau de fer, et même – believe it or not – the BBC, yes Sir !). Ses connaissances jazziques incontestables, Panassié fut chargé de la programmation. Autrement dit : pas de Bud Powell, Charlie Parker, Kenny Clarke ou Fada Gillespie sur la Prom’ des English ! Ce dernier d’ailleurs, après une tournée en Scandinavie, se retrouva comme par miracle, lui et son big band, par trois fois sur la scène de Pleyel, les 20, 22 et 29 février : un coup avant, un coup pendant, un coup après les réjouissances niçoises. Joli pavé dans la mare des festivités azuréennes ! Imperturbables, les discographes datent du 28 février l’ultime concert pleyelo-gillespien. Or, Louis et Teagarden y assistèrent. Pourtant, ce 28-là, tous deux étaient aux prises jusqu’au petit matin blême avec la Nuit de Nice ! Dizz ne manqua évidemment pas de venir à son tour applaudir Satch’ le 2 mars. Détail charmant : les affiches de ses concerts enfoncent le clou : « ce que vous n’entendrez pas à Nice », disent-elles…

Panassié voulait du solide, du confirmé (du moins côté vedettes), du pas-bebop, du pas-trop-audacieux et du surtout-pas-révolutionnaire-pour-un-rond ! Sage programme au fond, largement approuvé par ses complices, convenant paraît-il fort bien à un public réputé moutonnier… Outre le All-Stars donc (dont Louis et Bigard étaient les seuls à avoir fréquenté le Vieux Monde avant-guerre – Teagarden ayant loupé le coche d’une tournée avec Paul Whiteman en 36), on avait réquisitionné Rex Stewart et sa bande (qui jouaient déjà en France à l’époque), quelques remarquables musiciens « free-lance », tels l’excellent saxophoniste Lucky Thompson, et des formations européennes de qualité variable : l’orchestre belge de Jean Leclère , constitué de deux formations différentes et de ce fait quelque peu hybride ; le groupe suisse de Francis Burger ; les Britanniques de Derek Neville avec Humphrey Lyttleton ; les Français enthousiastes de Claude Luter, probablement la meilleure formation traditionnelle de l’heure. Louis, Earl et Hugues leur firent visite le lundi 1er mars dans leur fief du « Lorientais » (rue des Carmes, à Paris). L’Hugues en question s’était gardé d’oublier les copains, ce qui explique la présence du camarade Mezzrow, à la tête d’un groupe plutôt honnête constitué d’Henry Goodwin (trompettiste déjà venu en 1925 avec l’orchestre de la légendaire Revue Nègre), du bon tromboniste James Archey, du jeune clarinettiste Bob Wilbur, du pianiste Sammy Price et du mythique Warren « Baby » Dodds qui, en la compagnie du Roi Oliver, de Satchmo et de son regretté grand frère Johnny, avait vingt-cinq ans plus tôt, du haut de ses fiers tambours, fait trembler sur ses bases le studio champêtre de la maison Gennett (Starr Piano C°, Richmond, Indiana), pourtant habitué aux sourds grondements des locomotives à vapeur en furie…

Ce qu’en revanche il avait malencontreusement « oublié », Monseigneur Hugues, la chose se déroulant à Nice (Alpes Maritimes – France), c’est d’inviter aussi quelques pointures du swing hexagonal, Rostaing (de Lyon) ou Barelli (natif du lieu). Sans compter un certain Reinhardt, un nommé Grappelli – bref, ce que l’on désignait ordinairement sous le nom de « Quintette du Hot Club de France » (version strings reconstituée)… Le public s’en étonna, mais pas seulement : Rex et Louis, admirateurs du guitariste fou et du violoniste sage, firent écho. On dut leur répondre que ces deux-là, trop pris par leurs engagements parisiens, avaient décliné l’offre (qu’on s’était sûrement gardé de leur faire). Les autres jazzmen français, teigneux, vexés, joignirent leurs voix au concert. Si bien que Michel de Bry rattrapa le coup en catastrophe, embarquant l’équipe à cordes chaudes dans le train de nuit juste à temps pour la Nuit de Nice. On ne les entendit donc – pas dans les meilleures conditions – qu’au cours de cette ultime soirée (voir Intégrale Django Reinhardt, vol. 16 – Frémeaux FA-316), mais ils eurent tout le temps de faire la bise à Satchmo, Hines, Bigard, Big Tea, Mezz et aux autres. Sympathiques, émouvantes, quelques photos en témoignent…

Louis, Mezz et leurs bandes respectives n’étaient point arrivés à Nice par le train de nuit. Eux, ils eurent droit à l’avion et pas n’importe lequel ! L’un des plus beaux appareils de ligne, le superbe « Constellation 48 », fleuron justement privilégié d’Air France (également partenaire du festival), les transporta d’un continent à l’autre : La Gardia (New York) – Orly en un clin d’œil. Cela se fit dans la nuit du 19 février 48, non sans déjà un sens certain de la publicité : le tout premier relai de l’histoire, en direct New York-avion-Paris, via la Radiodiffusion Française, mené de main de Maître depuis l’aéroport de départ par Roger Goupilllère. On pourra donc entendre Satch’, Mezz et les leurs prononcer quelques mots puis offrir aux auditeurs de brèves mesures tremblotantes. Liaison bien sûr pas vraiment idéale, mais il fallait bien commencer et, aujourd’hui encore, il convient de saluer l’exploit. A l’arrivée à Orly, la radio était encore là, ainsi que le trompettiste Aimé Barelli et son orchestre, pour accueillir les voyageurs. Interrogé par un monsieur qui écorche gentiment quelques noms (il ne sera pas le seul !), Armstrong chante un petit bout de Flat Foot Floogie et dit sa joie de retrouver la France, pas vue depuis treize ans, ainsi que ses amis Reinhardt et Warlop. Michel Warlop avait replié son ombrelle le 6 mars 1947 (voir le recueil à lui consacré dans la collection « Quintessence » - FA295). En somme, Louis n’était décidément pas au courant de tout…

La radio – source à peu près unique de ce qui nous est parvenu, mais il y eut en ville d’autres moments musicaux à jamais évanouis – inaugura ses diffusions le soir du 22 février sur le Programme national, entre 20h30 et 21h45, puis de 22h15 à 23h30. Beaucoup pour de la musique de sauvâââges (en admettant, bien sûr, que l’on puisse appeler cela de la « musique ») !... Non seulement la RDF, mais aussi la BBC, Radio Monte-Carlo, la RTB, Radios Genève et Lausanne, les radios suédoise, danoise, norvégienne et finlandaise, l’Autriche, la Hongrie, la Tchécoslovaquie, qui se joignent à l’ensemble presque quotidiennement – on trouvera ici un fragment de l’annonce en suédois pour la Nuit de Nice, le 28 (CD 2, début plage 14) ! Comme il se doit, tout commence avec la présentation par le réalisateur en chef, Gilbert Cazeneuve, introduisant les différentes instances responsables et le Maître de Cérémonies Roger Pigaut, avenant jeune premier alors fort à la mode, remarqué dans quelques films importants (Douce, Sortilèges, Antoine et Antoinette…). Pourquoi lui et pas Gérard Philipe (natif de Cannes), par exemple ? On ne sait. Il aimait peut-être le jazz ? Celui-ci mentionne les orchestres dans l’ordre de leur entrée en scène. Rex Stewart et Mezzrow ont droit à trois morceaux chacun ; Claude Luter, Derek Neville et Jean Leclère (avec et sans Lucky Thomson) en jouent deux ; Francis Burger n’en récupère qu’un seul. Comme il fallait s’y attendre, C’est Louis et son « Hot Five » (ainsi l’appellera-t-on tout au long du festival, plutôt que « All-Stars », sans doute pour renvoyer le public européen aux fabuleux disques de 1925-28, toujours en bonne partie disponibles) qui se taille la part du lion avec cinq morceaux choisis pour mettre le groupe et ses principaux membres en valeur : Muskrat Ramble, Rockin’ Chair, Boogie-Woogie on the St. Louis blues (cheval de bataille de Hines depuis des années), Rose Room et I Gotta Right to Sing the Blues, sur lequel Pigaut glisse sa désannonce. Ce sont évidemment ces cinq-là que l’on trouvera ici, à la fin du CD 1. Le reste est connu, mais Armstrong n’y intervient évidemment pas. Jean-Pierre Daubresse a inclus les Luter dans une intégrale 1947-49 consacrée au clarinettiste (Memories CD 13-14-15)…

En réalité, il paraît peu vraisemblable que tout cela ait été transmis en direct. Il n’est en effet guère probable de faire se succéder sur scène sept formations, avec ce que cela implique de temps de mise en place de chacune, pour n’interpréter que deux ou trois morceaux – voire un seul ! En tous cas, on ne relève sur les laques survivantes, aucun « blanc » susceptible de correspondre à de tels temps morts. Et puis, curieusement, les interprètes n’annoncent pas leurs titres, chose des plus inhabituelles… Il fut donc rapidement procédé à un montage éliminant au vol certaines pièces et les passages jugés inutiles. Dans la version 1969 de son Louis Armstrong (Nouvelles Editions Latines), Panassié précise bien que « quelques concerts furent enregistrés pour des retransmissions radiophoniques en différé ». Au fait, qu’est donc devenue la seconde partie de ce programme initial, celle allant de 22h15 à 23h30 ? Il semble qu’elle ait sauté les pistes. On sait seulement, sans connaitre le détail des titres, que Louis s’y trouvait davantage en valeur. Il est toutefois possible que certaines de ces interprétations aient été diffusées au cours des jours suivants et se retrouvent dans le CD 2. D’autres émissions avec Louis furent en effet transmises sur la chaîne parisienne (le 25) et sur Paris-Inter (le 26), mais, là encore, on ignore ce qui fut joué. On connait en revanche au moins une partie de la participation armstrongienne du lundi 23, de 23h à 23h30 (Programme National), grâce au magazine suédois Estrad qui fournit quelques titres dans son numéro d’avril 48 (CD 2, plages 1 à 6)… A noter que le When It’s Sleepy Time…(plage 1) par lequel s’ouvre l’émission figure dans sa totalité et non, selon la coutume, en court indicatif. Probable donc qu’on ait ici affaire à un extrait d’un concert plus large… Le mardi 24 le All-Stars se reposa et aucun programme radio (en différé) ne fut signalé. Le 27 il ne fut pas davantage radiodiffusé, mais on sait que Louis et Mezz se relayèrent de 22h à 1h du matin au Casino de Nice (le « Ruhl » ?)… Enfin, on possède une trentaine de minutes de la Nuit de Nice finale – pour une fois réellement envoyées en direct sur l’antenne du Poste Parisien depuis le « Negresco » le soir du 28 février, avec notamment une belle version d’Ain’t Misbehavin’ et un nouveau Boogie-Woogie on the St. Louis Blues (CD 2, plages 14 à 17). Pour l’occasion, Suzy Delair et Yves Montand étaient présents eux aussi… Chantèrent-ils ? La pétulante Suzy n’était cependant, il est vrai, pas très swing. Quant à Yves, l’intégrale Frémeaux prouve que dans ce domaine, il avait de l’avenir.

Les documents dont on dispose aujourd’hui – qu’on trouvera à partir de la plage 15 du CD 1 et dans la totalité du CD 2 – proviennent des enregistrements réalisés en public au cours des différents concerts afin d’être diffusés la plupart du temps en « différé ». Il s’agit presque toujours de copies sur laques déjà corrigées et non des originaux. Armstrong fut particulièrement gâté – plus en tous cas que ses collègues, ce qui semble assez normal. Fin 1949, l’Association Française de Gramophilie (AFG), dont Michel de Bry était l’un des animateurs, conclut un arrangement avec la radiodiffusion pour éditer sur quatre disques 78 tours 25 et 30 centimètres plusieurs extraits de ces concerts niçois (dont il avait été aussi l’un des promoteurs) : Monday Date, Royal Garden Blues (en deux parties chacun), Panama, Black and Blue, Velma’s Blues et That’s my Desire. L’association s’était fixée pour but de rééditer des enregistrements historiques souvent fort anciens et pas nécessairement du domaine du jazz. Les titres niçois, (leur origine ne fait ici aucun doute), constituent donc une exception pour cette entreprise parfaitement légale dont la réalisation (copie, pressage) fut confiée à Pathé-Marconi.

Peu de temps après – toujours à l’ère heureuse du 78 tours – d’autres galettes de 30 centimètres « sans marque » (puisque simplement ornées d’étiquettes blanches, sans le moindre repère discographique, à l’exception des titres, inscrits à la main) firent leur apparition. Nettement moins légaux que les précédents, ces disques-là mélangent allègrement les vrais concerts de Nice et celui du 2 mars à Pleyel… Les initiés surent, durant de longues années, les trouver dans une dépendance discrète du siège parisien (Xème arrondissement) d’une jeune firme phonographique appelée à connaître une vogue certaine !

Plus tard, les légaux et les autres devinrent microsillons 33 tours avec plus ou moins de bonheur. Une édition confidentielle italienne des années 1970 ajouta des versions jusqu’alors inédites. En revanche, deux LPs français sont au-dessous de tout, qui mélangent allègrement tous ces machins… Finalement, ce que l’on trouvera ici n’est sans doute pas tout à fait l’intégrale de ce qui fut capté : des laques sont plus que probablement perdues, détruites, et on connaît plusieurs titres isolés (dont deux I Cried Last Night incomplets) d’origine incertaine et de qualité médiocre. Mais on peut dire que dans l’état des connaissances à l’été de 2014, le travail de bénédictin accompli par Irakli donne accès à un panorama jamais approché jusqu’ici, plus large, de l’exercice niçois.

A la fin des festivités – et du CD 2 (plage 18) – Louis exprime, à la demande Loys Choquart pour la TSF suisse, ses impressions express sur les évènements. Ravi, il suggère que le festival devienne une institution et qu’ils puissent, lui et sa bande, revenir tous les ans dans ce beau pays… Ainsi donc, ce n’est pas à New York, ni à Newport, ni à Monteray que naquit l’idée d’un festival de jazz régulier, mais bien dans cette sale vieille Europe encore en train de panser ses horribles plaies. C’est elle déjà qui, à la fin de la première Guerre, avait reconnu le jazz comme musique nouvelle à part entière, alors que le pays natal n’y voyait qu’un vulgaire divertissement à l’usage des nègres – même s’il y eut parfois là-bas des gens un peu plus éclairés. Evidemment, les choses n’allèrent pas aussi vite que Louis et les autres l’eussent souhaité. Il n’y eut pas de festival de Nice en 1949. Ni en 1950, 1951 et 1952… Bien sûr, la grande cité accueillit par la suite encore bien des jazzmen, mais dans le cadre de concerts du type traditionnel. D’autres villes organisèrent à leur tour leurs festivals : Paris, Monte-Carlo. Mais cela ne dura jamais très longtemps. Les Américains s’y mirent enfin avec Newport. En juillet 1959, eut lieu le premier festival d’Antibes-Juan les Pins, grande rivale de Nice, qui aurait dû accueillir Sidney Bechet, mais… Plus tard encore il y eut Comblain-la-Tour en Belgique et Montreux en Suisse. Puis Vienne, non pas en Autriche, mais dans l’Isère, suivie de Marciac dans le Gers. Entretemps, dès l’été 1974, Nice avait enfin repris du service dans les jardins de Cimiez. Malheureusement, ni Louis ni Mezz ne purent s’y rendre. Ni même Duke, disparu quelques mois plus tôt. Mais parmi le gang des quarante-huitards, on entendit tout de même Bob Wilbur, Barney Bigard et surtout Earl Hines. In a Mist – en souvenir…

C’est Boris Vian qui couvrit Nice, à la fois pour le quotidien Combat et pour le mensuel Jazz Hot. Il narra de petites histoires « en marge », trouva l’exhibition de Django et Grappelli « minable », mais se garda de raconter que Luter et son équipe, en rogne contre l’organisation, avaient enregistré en douce quatre faces pour une petite firme locale ! Quant à Louis, il admit que son « orchestre, lui, était parfaitement à sa place (peut-être eût-il été meilleur avec un autre que Teagarden, bien fade) et la façon dont il a joué le 3 mars à Pleyel, prouve que ses qualités sont toujours plus que satisfaisantes… ». Comme d’habitude, c’est la fête à « Big Tea ». Le concert parisien du 3 mars inspira à André Hodeir, rédacteur en chef de Jazz Hot, quelques sympathiques petites piques à son endroit : «Je mets à part Jack Teagarden, dont je n’aime pas la fadeur de bon ton au trombone, et qui, en tant que chanteur, ne me semble pas avoir d’autre tâche que de servir de repoussoir à Louis – ce dont il s’acquitte assez bien ». En ce temps-là, 1948, la rupture entre les « raisins aigres » (les modernistes, dont Hodeir était l’un des chefs de file) et les « figues moisies » (les tenants du jazz traditionnel, dominés par la figure tutélaire de Panassié) était déjà consommée. Pourtant, Hugues aussi estime que « les spécialités de Teagarden sont fastidieuses ». Pour le coup, tous d’accord. C’est qu’il a un énorme défaut, Teagarden – son péché originel en somme : il est blanc (et texan de surcroit !). Et, comble de l’horreur, il a joué des années durant chez Paul Whiteman. Impardonnable ! Ainsi donc, Louis Armstrong aurait un goût si atroce qu’il voulait ab-so-lu-ment « Tea » et nul autre (les bons trombonistes noirs ne manquaient point) dans son All-Stars ? Si épouvantable même que quand l’abominable tromboniste-chanteur pâle et fade manifesta l’envie d’aller voir ailleurs s’il y était, Louis en fut tout retourné – bien plus que quand Earl Hines choisit d’en faire autant… Jack-Armstrong ? Un de ces duos magiques comme seul le jazz sait en inventer. N’en déplaise…

C’est le premier concert, celui du 2, qui fut diffusé (mais pas REtransmis !), cette fois en vrai direct : les nombreux cafouillages qui l’émaillent en témoignent. Toutefois, on peut sans risque affirmer que ce concert-ci et celui du lendemain se ressemblèrent comme deux jumeaux. Au reste, Hodeir dans son compte-rendu (Jazz Hot n°21, mars 1948), ne manque pas de remarquer (surtout à l’endroit des spécialités de Bigard et d’Arvell Shaw) avec un zeste d’aigreur : « …tout cela sentait le réchauffé, comme en ont pu juger ceux qui ont écouté les retransmissions de Nice et du premier concert parisien : on retrouvait les mêmes effets aux mêmes endroits. Où étaient la spontanéité, la sincérité propres aux musiciens noirs ? ». Hodeir, compositeur souvent inspiré, arrangeur intelligent et subtil, pensait-il vraiment que la « spontanéité » était la vertu cardinale du jazz ? Voulait-il faire croire que les grandes formations d’Ellington ou de Gillespie (qu’il venait d’entendre dans la même salle et dont il parle dans le même numéro de la revue) ne fonctionnent que sur le mode la stricte improvisation pure et « sincère » ?

Il n’en est pas moins vrai que tous ces concerts, niçois, parisiens, mais aussi new yorkais ou bostonien de la fin 47, sont assez désespérément coulés dans le même moule. Evidemment, si les réjouissances se passent dans des lieux différents, parfois fort éloignés les uns des autres, le public est lui aussi différent et l’on peut certes reprendre à peu près la même chose chaque fois. C’est logique, surtout si l’on dispose d’un répertoire solide, bien rodé, qu’il paraît inutile de modifier. Mais quand on joue d’abord à Nice toute une semaine, puis à Paris deux soirs de suite – le même petit pays – et qu’une bonne partie se balade sur les ondes, cela peut sembler quelque peu abusif. Quoiqu’il en soit, seule la soirée du mardi 2 mars 1948 fut radiodiffusée sur l’antenne de Paris-Inter. Les magazines spécialisés ne la mentionnent en rien, mais une brève note de Jazz Hot permet de la situer. Tout porte à croire que les choses se firent en catastrophe : l’impréparation technique, la saturation, la balance défectueuse entre la voix de Louis et les instruments, la présentation pas vraiment audible… A ce propos, notons la présence (au début) d’une double présentation : un quidam qui prononce « Armstrogne » le nom du trompettiste et une dame, Madeleine Gautier, vieille complice de Panassié, qui prononce bien, elle, mais se trouve rapidement hors-jeu. Etait-ce son baptême du feu ? N’avait-elle jamais fait de micro en direct ? Alors, elle fut joliment gâtée, couverte par la musique, coupée dans son élan, asphyxiée… Si bien que la malheureuse, au bout de quatre ou cinq essais, rendit son tablier et laissa « Monsieur Armstrogne » se dépatouiller tout seul ! C’est lui qui, après avoir doctement traduit Tea for Two par « Thé pour deux », annonce l’entr’acte après Steak Face en remerciant la ville de Nice et la radio. Dans la seconde partie, il ne manquera pas d’affirmer que High Society, vieille marche annexée par les gens du ragtime et du jazz, fut composé à La Nouvelle Orléans par Louis Armstrong en personne ! On en connait pourtant des enregistrements aux accents militaires et new yorkais dès 1910-11 ! Bizarre…

Avant toute chose, Hodeir très remontré de son côté, commence par fulminer dans son compte-rendu contre « les organisateur qui n’ont pas cru devoir inviter le rédacteur en chef de la seule revue spécialisée » et déplore que « le prix des places ait été si élevé » (mille francs pour un siège correct). D’autant que « le public des loges et des fauteuils avancés était formé de gens à la mine insolente et aux manières insupportables qui sont ordinairement celles de cette classe que la guerre et le marché noir ont enrichie. (…) Ceux-là n’aimaient ni Louis ni le jazz. Ils étaient là parce que les journaux avaient parlé d’Armstrong et que les fauteuils coûtaient mille francs. »… Il fallait que cela fût dit.

Le concert reproduit au CD 3 est incomplet. Enregistré « en simultané » selon semble-t-il le nouveau système en son optique « Philips-Miller » (rapidement balayé par la bande magnétique), il fut recopié sur laques afin d’en permettre les REtransmissions par les stations lointaines. Dommage pour le Where the Blues Were Born suivant l’indicatif et ne figurant pas parmi les thèmes les plus souvent joués. Mais la copie en la possession d’Irakli est quasiment inaudible. La suite passe mieux, à savoir le répertoire classique, avec les bonnes versions habituelles d’inoxydables standards : Royal Garden Blues, You Rascal You (Vieille Canaille chez les Gaulois), Back O’Town Blues, Mahogany Hall Stomp, On the Sunny Side of the Street, High Society, Basin Street Blues, Muskrat Ramble…

Sympathique duo vocal également sur That’s my Desire entre Louis et Velma Middleton (dont les grands écarts rigolos ne déridèrent point les musicologues sérieux). On a évité les « spécialités » dans lesquelles Satchmo intervient peu (ou pas), notamment Lover et Stars Fell on Alabama (Teagarden) ou le « Thé pour deux » bigardien. On a toutefois gardé le Steak Face de Catlett et même le How High the Moon fastidieux octroyé au bassiste. Mention particulière en revanche pour Earl Hines, si subtil et délicat sur Someone to Watch over Me de Gershwin, compositeur auquel il ne nous a guère habitué. Earl pratique certes plus volontiers ses propres compositions ou celles de Fats Waller, vieux copain trop tôt disparu, dont il interprète ici une des chansons les plus célèbres, Honeysuckle Rose, avec cette fois intervention brève mais décisive de Louis…

Ainsi, sur ces retrouvailles avec la salle Pleyel, s’achève le premier périple européen d’après guerre de Louis Armstrong. Gageons que ce ne sera pas le dernier. De notre côté, sachant qu’une intégrale des concerts ne s’impose pas, nous veillerons à ce que le contenu des prochains volumes soit peut-être davantage varié.

Daniel NEVERS

Remerciements : Philippe Baudoin, Jean-Pierre Daubresse, Alain Delot, Yvonne Derudder, Jean Duroux, Pierre Lafargue, Clément Portais.

Remerciements très spéciaux à : Irakli De Davrichewi et Annie Delahaye.

© 2015 Frémeaux & Associés

Louis ARMSTRONG – Vol.14

To avoid presenting the All Stars’ concert at Boston’s Symphony Hall (November 30th 1947) in separate parts—it appears in its entirety on CD3 of Vol.13, FA1363—we decided to carry forward the four titles from the ultimate RCA session (October 16th) and place them at the beginning of the following volume. And that’s why this new set, the 14th in the complete Louis Armstrong recordings, opens with these. The first two, A Song Was Born and Please Stop Playing Those Blues, probably the best of the four, features excellent contributions, both as instrumentals and songs, from Louis and his quiet accomplice Teagarden. A Song Was Born, in particular, evidently has a sound quite different from the version in the Howard Hawks film A Song Is Born from which it is taken (it was made in the course of the previous summer, cf. Vol. 13, Frémeaux FA1363, but still hadn’t been released.) In fact, that Sam Goldwyn production—yes, Goldwyn, the “G” in MGM, although the studio no longer bears much resemblance to the company with the roaring lion—would only be released to darkened theatres at the very end of 1948; maybe they had distribution-problems despite the fine cast, one never knows... Whatever, Louis and his gang made only parsimonious use of the tune in their repertoire, and that’s a pity.

Armstrong made no records at all for the venerable Victor Talking Machine Co. (as it was known pre-1930), and when RCA took over the reins his relations with the company were brief: just a few months, from December ‘32 to April ‘33 (cf. Vol. 6, FA1356), and then his 1946-47 contract which ended with these pieces here. And that, too, is regrettable, because he hadn’t been so superbly recorded for a long time… It did happen, of course, as with a number of his colleagues during the war, that he would spend some time in the RCA-NBC studios out on the West Coast, in order to take part in his country’s military effort: he contributed an abundant series of recordings to the AFN and the AFRS (cf. Vols. 10 & 11, FA1360, FA1361), but it wasn’t quite the same thing; especially when you consider the length of the contracts he honoured from 1925 to 1932, first with OkeH (although Columbia had a controlling interest in the label after 1927), and then with the newly-founded Decca company (1935-1946). In any case, all new signings were put back due to the strike which, although shorter and less virulent than in 1942-44, still managed to paralyze the entire recording-industry of the United States (yet again) for the best part of 1948.

A few of the younger labels, like Capitol, silenced talk of congenital American stinginess by taking advantage of that forced hiatus to equip their studios with new technology, notably machines which recorded on magnetic tape. But the old hands remained happy to wait for the sunnier days of 1950-51… The consequence of all this for Armstrong, and his brand-new All-Stars—the one generally referred to as the first “real All Stars” (which lasted for two years before major changes were made)—was that he made nothing for people with phonographs. It’s true that the name “All-Stars”, inaugurated in the summer of 1947, already appeared on the recordings for Victor and Co. dated October 16th, but for that session and the concerts around that time (Carnegie Hall, Symphony Hall…), the pianist was still the kindly Dick Cary, so happy to be playing in the older kids’ playground. Earl Hines would only make his appearance—not a Lourdes-type apparition: the band was in Nice—early in January 1948 (theoretically just for the year). At the other end of the period, i.e. only at the end of April 1950 (with Louis making a few new records in the interval, but without his working band), it was Sidney Catlett, the drummer, who left his seat to Cozy Cole for health reasons. Fortunately—providing a chance to appreciate this exceptional crew—there remain a good few concerts and radio programmes, and, incidentally, they (rather logically) go hand in hand. They link together so well, in fact, that with the exception of the four RCA sides mentioned above, the entire set here is made up of concert-recordings that were more or less “live broadcasts” (as they say), with love from here and elsewhere, naturally.

“Here”, no doubt, and “live”, perhaps, where these fragments from November 15th 1947 are concerned; they are remarkably recorded and were probably broadcast from the stage of the prestigious Carnegie Hall. Some of the old bio-discographies indicate rather that they came from New York’s Town Hall (on the same date), where a concert had already been held on May 17th (and incidentally, that one had been dated earlier as an April concert, cf. Vol.13). It’s certain that a second Town Hall concert took place, but the exact date remains unknown, as does all the music it featured… The excellent sound-quality tends to favour the establishment built at the request of the very wise (and very wealthy) Mr. Carnegie. It is not impossible that there were actually two concerts, the first held at a reasonable hour, and the second after midnight.

With the repertoire unfortunately already inclined to sclerosis, it seemed a good idea, to avoid redundancy with the performance at Boston’s Symphony Hall a fortnight later, not to include the entirety of the concert(s), but only certain excerpts, either titles which weren’t played on November 30th (Back O’Town Blues, Basin Street Blues, Rockin’ Chair, I Gotta Right to Sing the Blues), or those featuring interesting variations whose accents sometimes show more vigour (Body and Soul, Stars Fell on Alabama, High Society) than at the end of the month…

What comes after corresponds to that “elsewhere”, i.e. the other side of the Atlantic: first Paris, and then the French Riviera, in Nice, where the first jazz festival in History was to be held, from Sunday February 22nd to Saturday February 28th 1948… The Golden Age of festivals—the Fifties, Sixties and Seventies—was just taking its first tottering steps. Even the film world had barely been allowed to hold any: the old Venice Biennale, Fascistic and discredited, had been written off, and Cannes, after the debacle in September ‘39, had finally organized a timid premiere in ‘46, with none the following year. As for theatre, it had just discovered the road that led to the “Cour d’Honneur” of the Palais des Papes in Avignon.

Jazz, certainly, had become accepted, in both the old and the new worlds, on fine, prestigious stages, but that was due to isolated concerts given by one musician or another, or a famous orchestra: in no way could its acceptance be interpreted by festivals spread over several days, and which mingled the most renowned Kings of Swing with unknown newcomers, promising or not. The establishments which welcomed them—Carnegie Hall, Town Hall, the Civic Auditorium in Chicago, Symphony Hall in Boston, the Hollywood Bowl, the London Palladium, the Salle Pleyel, Salle Gaveau and Châtelet in Paris etc.—were for the most part in private hands, and could therefore be hired by anyone with enough loose change who cared to put on any kind of show (including the fearsome Madam Florence Foster Jenkins!); there was no obligation to refer to these goings-on as a coherent ensemble of public manifestations. When it came to putting on a festival, the situation was not exactly a favourable one. For that, one needed an entire organization and solid resources, particularly in official spheres! One had to toy with notions such as: duration (the ideal being a well-filled week); different venues where events could be housed; schedules and times; combinations (in skilful doses) of celebrities with those less famous…

Nice took no chances: its festival took place under the High Patronage of the President of the Republic (who gave a Sèvres porcelain vase to Louis Armstrong; no,

Stéphane, no! Your memory’s playing tricks, the name of the President in ‘48 was Vincent, not Albert!), the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and others, from the Secretary of State to the President of the Council and all the leading local bigwigs. Two venues, especially, were appointed to serve the cause: the Opera and Casino in Nice; and for the crowning piece on the 28th, the salons of the Hotel Negresco (today a registered monument) at five thousand Francs a seat! And so the trio of Michel de Bry, Paul Gilson and Hugues Panassié saw their beautiful dream come true. De Bry and Gilson enlisted the active support of Radiodiffusion Française, relayed in turn by radios in many wild jungles (sometimes beyond the iron Curtain, and even, believe it or not, the BBC, no less!) Panassié’s knowledge of jazz was unquestionable, and he was tasked with programming the event. In other words, there was no Bud Powell, no Charlie Parker, no Kenny Clarke or Nutty Gillespie to be seen on the English Promenade in Nice! Gillespie, by the way, after a tour in Scandinavia, found himself (with his big-band) by miracle onstage at Pleyel no fewer than three times that February, on the 20th, 22nd and 29th, i.e. once before, once during, and once after the fun in Nice. Boy, did that throw a nice spanner in the Riviera works! Discographers imperturbably dated the final Gillespie concert at Salle Pleyel as being on February 28th. Louis and Teagarden were even there. And yet, on that very same 28th, both of them were battling away until the wee, wan hours of the morning at the Nuit de Nice! Dizz’, obviously, didn’t miss the chance to go down and applaud Satch’ on March 2nd. Another charming detail is that the posters for his concerts rubbed it in: “What you won’t hear in Nice”, they announced.

Panassié wanted solid stuff on the programme, something confirmed (at least where the stars where concerned); he wanted the not-bebop, the not-too-daring, and especially the not-revolutionary-by-any-stretch-of-the-imagination. A sensible, obedient programme, basically: a bill widely approved by his sidekicks and eminently suitable for a reputedly sheep-like audience… So, apart from the All-Stars (among whom Louis and Bigard were the only ones to have taken the trip to the Old World before the war, with Teagarden having missed out on a tour with Paul Whiteman in ‘36), Panassié requisitioned Rex Stewart and his band (who’d already played in France in those days), a few remarkable “freelance” musicians, like the excellent saxophonist Lucky Thompson, plus European ensembles of varying quality: the Belgian orchestra of Jean Leclère, made up of two different bands and therefore somewhat hybrid; the Swiss group of Francis Burger; Derek Neville’s British band with Humphrey Lyttelton; and the enthusiastic French band of Claude Luter, probably the best traditional group around at the time (Louis, Earl and Hugues went to see them on March 1st in their Parisian stronghold, the “Lorientais” on the rue des Carmes).

Nor did the afore-mentioned Hugues forget his chums, which explains the presence on the bill of comrade Mezzrow, fronting quite an honest band made up of Henry Goodwin (a trumpeter who’d already been to France in 1925 with the orchestra of the legendary Revue Nègre), the good trombonist James Archey, the young clarinettist Bob Wilbur, pianist Sammy Price, and one legend: Warren “Baby” Dodds who, twenty-five years previously, in the company of King Oliver, Satchmo and his now deceased big brother Johnny, had loomed over his proud drums to shake the rural studio of the Gennett Company (Starr Piano C°, Richmond, Indiana) to its very foundations, even though they were used to heavy rumblings from raging steam locomotives…

What Mylord Hugues most unfortunately “forgot” when thinking about his programme—with the event being set for Nice, remember, in the south of France—was to invite also several aces on the French Swing scene, namely Rostaing (from Lyon) or Barelli (who was born in Nice). Not to mention a certain Reinhardt and Grappelli, usually abbreviated as the Quintette du Hot Club de France (in its reconstituted version with strings)… The public were amazed at the oversight, and they weren’t alone: Rex and Louis, both of them admirers of the mad guitarist and the sage violinist, echoed their astonishment. They were duly told that the pair in Paris were too busy with their bookings and had declined the offer from Nice (where pains were certainly taken not to make an offer in the first place). The other French jazzmen—cantankerously hurt—added their voices to the protests, so loudly in fact that Michel de Bry had to salvage the affair in a rush by packing all the above strings, still warm, into the night train just in time for the Nuit de Nice. So they were only heard—and not in the best conditions—in the course of that last night (cf. the complete Django Reinhardt, Vol. 16 – Frémeaux FA316); but they had all the time they needed to hug Satchmo, Hines, Bigard, Big T, Mezz and the others. It was all very nice, and moving, as shown in the photos…

Louis, Mezz and their respective crews hadn’t arrived in Nice by train at all. They came by plane, and not just any plane… their superb Constellation 48, one of the finest in the airline’s fleet (the literal pride and joy of Air France, one of the festival’s sponsors), flew them from one continent to the other: from LaGuardia in Queens to Orly in the blink of an eye. They crossed in the night of February 19th 1948, and there was already a publicity-angle in the air: it was the first relayed broadcast in history, New York-live-aeroplane-Paris, via the Radiodiffusion Française, masterfully conducted from the moment they took off by Roger Goupillère. So you can hear Satch’, Mezz & Co. say a few words before offering their listeners a couple of short, trembling bars. The radio link isn’t ideal of course, but they had to start somewhere and, even today, the exploit is worth a salute. On their arrival at Orly, radio was there again, as was Aimé Barelli (and orchestra), to welcome the passengers. Replying to questions from a gentleman who mispronounces a few names (he wouldn’t be the only one!), Armstrong sings a little bit of Flat Foot Floogie and says what a joy it is to be back in France—he hadn’t seen it for thirteen years—and to see his friends Reinhardt and Warlop. In fact, Michel Warlop had put his parasol away for good on March 6th 1947 (cf. the collection devoted to him in the “Quintessence” series, FA295). So there were some things, finally which escaped Louis after all…

Radio—the almost unique source of recordings still available to us, but some musical moments in town have gone forever—inaugurated its broadcasts on the evening of February 22nd on the national programme which went out between 8.30pm and 9.45pm, and then from 10.15pm to 11.30pm. It was a lot for wild man’s music (even if you admit that this can be called music)! Not only the RDF was there, but also the BBC, Radio Monte-Carlo, the RTB, Radio Geneva and Radio Lausanne, stations from Sweden, Denmark, Norway, Finland, Austria, Hungary and Czechoslovakia… They all joined in almost daily, and here you can even find a fragment of an announcement in Swedish dated the 28th (CD2, at the beginning of track 14). Played by the rules, it all begins with a few words from chief-producer Gilbert Cazeneuve, who introduces the various bodies responsible and the M.C. for the proceedings, Roger Pigaut, a pleasant young “leading-man” figure then quite fashionable and who had been seen in a few major films (Douce, Sortilèges, Antoine et Antoinette…). Why him and not Gérard Philipe, say (he was born in Cannes)? We don’t know. Did he like jazz, perhaps? Pigaut names the orchestras in the order they appear onstage. Rex Stewart and Mezzrow are allowed three tunes each; Claude Luter, Derek Neville and Jean Leclère (with and without Lucky Thompson) play two each; Francis Burger gets only one. As might be expected, Louis and his “Hot Five”—as they will be referred to throughout the festival, rather than the “All-Stars”, probably in order to remind the European audience of those fabulous 1925-28 records, mostly still available—receive the lion’s share, with five pieces chosen to highlight the group and its principal members: Muskrat Ramble, Rockin’ Chair, Boogie-Woogie on the St. Louis Blues (a Hines feature for years), Rose Room and I Gotta Right to Sing the Blues, over which M.C. Roger Pigaut slips his outro. Those five are obviously the ones you can hear at the end of CD1 in this set. The rest are known, but Armstrong obviously doesn’t contribute. Jean-Pierre Daubresse included the Luter tunes in a 1947-49 complete edition devoted to the clarinettist (Memories CD 13-14-15)…

In reality, it seems quite unlikely that all the above was broadcast “live”: having seven bands follow each other onstage is hardly probable, given the time necessary for each band to gear up and play two or three numbers, or even just one! You only have to look at the surviving lacquers, in fact, to see that there aren’t any blanks that might correspond to intermissions; and the performers, curiously, don’t announce their titles, which is most unusual… So there was a quick montage which eliminated certain tunes, and passages deemed unnecessary, on the fly. In the 1969 version of his book Louis Armstrong (published by Nouvelles Editions Latines), Panassié indeed makes clear that “a few concerts were recorded for radio broadcasts at a later time.” What happened to the second part of the initial programme, then, the one from 10.15pm to 11.30pm? It looks like it jumped off the track. All we know, without having detailed track-information to hand, is that Louis was featured more. It’s possible, however, that some of his playing was aired during the days that followed and can be heard on CD2. Other programmes with Louis were aired on the Parisian station (on the 25th) and on Paris-Inter (the 26th) but, there again, we don’t know what was played. We do know, on the other hand, at least a part of Armstrong’s performance on Monday the 23rd, from 11pm to 11.30pm (on the “Programme National”), thanks to the Swedish magazine Estrad which provided a few titles in its April ‘48 issue (CD2, tracks 1-6)… Note that the tune When It’s Sleepy Time (track 1), which opens the programme, appears in totality and not, as was customary, as a short “jingle”. So it’s probable that we’re dealing with an excerpt from a longer concert here… On Tuesday 24th the All-Stars had a day off and no radio programme (“at a later time”) was mentioned. It wasn’t aired on the 27th either, but we know that Louis and Mezz alternated between 10pm and 1am the next morning at the Nice Casino (the “Ruhl”?)… And we do have thirty minutes’ music from the last Nuit de Nice—for once, genuinely broadcast (by Poste Parisien radio) “live” from the Hotel Negresco on the evening of February 28th, notably with a beautiful version of Ain’t Misbehavin’ and a new Boogie-Woogie on the St. Louis Blues (CD2, tracks 14-17). For the occasion, Suzy Delair and Yves Montand were present, too. Did they sing? The vivacious Suzy wasn’t, it’s true, much of a “swing” person. As for Yves, the complete Montand on the Frémeaux label shows that he had something of a future in this area.

The sounds we have available today—from track 15 to the end on CD1, and throughout CD2—come from recordings made in front of an audience in the course of different concerts, for the most part with “later” broadcasts in mind. In almost all cases, these pieces are copies from lacquers that have already been corrected, and not the originals. Armstrong is quite pampered—more than his colleagues, in any case, which seems quite normal. At the end of 1949, the AFG (“Association Française de Gramophilie”), of which Michel de Bry was an active member, came to an agreement with the “Radiodiffusion” to release four 78rpm records (10” and 12”) featuring several excerpts from those concerts in Nice (where de Bry was also one of the promoters): Monday Date, Royal Garden Blues (each in two parts), Panama, Black and Blue, Velma’s Blues and That’s my Desire. The AFG aimed to reissue historic recordings, often ancient ones, and not necessarily jazz either. So the Nice titles (there is no doubt as to their origin here), constituted an exception for this perfectly legal enterprise, whose products were entrusted to Pathé Marconi for duplication and pressing. Shortly afterwards—but still in the happy era of 78’s—other “anonymous” 12” discs (because they had simple white labels with no official reference numbers at all, except for handwritten titles) made their appearance. Considerably less legal than the first, the latter blithely combined the real concerts in Nice with the one at Salle Pleyel on March 2nd… For many long years, initiates could obtain them from a discreet outlet belonging to the Parisian HQ (in the 10th arrondissement) of a recently-founded record-company. It was destined to be in vogue…

Later, both the legal ones and the others became 33rpm LPs of varying fortunes. One confidential Italian release (in the 70’s) added versions that hadn’t seen the light before. Two French LP’s, on the other hand, were the pits, mixing everything up any-old-how… All of which goes to say that what you can find here is probably not quite a complete set of what was recorded: lacquers have been (more than probably) lost and/or destroyed, and we know of several isolated titles (including two incomplete versions of I Cried Last Night) of uncertain origin whose quality is mediocre. But what we can say for sure, in the current state of our knowledge—summer 2014—is that the accomplishments of Irakli, a Benedictine in his patience and intellectual labours, give us an overview of the Nice episode that is broader than ever before.

At the end of the festivities—and of CD2 (track 18)—Louis delivers his impressions of events to Loys Choquart (Radio Switzerland), delightedly saying that he thinks, “This festival should become an institution, so that we can come back to your beautiful country every year.” And so it was neither in New York, nor in Newport or Monterey, that the idea of a regular jazz festival was born, but indeed in a dirty old Europe still licking its horrible wounds. That same Europe which, at the end of the Great War already, had recognized jazz as new music in its own right, whereas its native land saw it merely as vulgar entertainment for consumption by Negroes—even if there were people living there who were a little more enlightened. Obviously, things didn’t go quite as quickly as Louis and the others had hoped. There was no festival in Nice in 1949. Nor in 1950, 1951 and 1952… The great city of Nice would of course welcome many jazzmen later, but the context was different: there were concerts of the traditional type. Other cities in turn organized similar events, like Paris and Monte-Carlo, but it never lasted very long. The Americans finally got down to it in Newport. July 1959 saw the first festival in Antibes-Juan les Pins, Nice’s great rival, which ought to have welcomed Sidney Bechet, but… Still later, there was Comblain-la-Tour in Belgium, and Montreux in Switzerland. And then Vienne (not Vienna, but Vienne, south of Lyon), followed by Marciac. In the meantime, by the summer of 1974 Nice had finally started up again in the gardens of Cimiez. Unfortunately, neither Louis nor Mezz could attend; nor Duke, who’d died a few months before. But of those from that ‘48 vintage, one could still hear Bob Wilbur, Barney Bigard and especially Earl Hines. In a Mist – a souvenir…

It was Boris Vian who covered the Nice event, both for the daily paper Combat and for the monthly Jazz Hot. He narrated little stories “from the fringe” and found the exhibiting of Django and Grappelli “pathetic”, but he refrained from reporting that Luter and his crew, hopping mad at the organizers, had secretly recorded four sides for a little local label! As for Louis, Vian admitted that his “orchestra was perfectly in its place (perhaps it would have been better with someone other than Teagarden, quite dull) and the manner in which he played at Pleyel on March 3rd proves that his qualities are still more than satisfactory…” As usual, he gave Big T a hard time. That Parisian concert on March 3rd inspired some nice little barbs also aimed at the latter by André Hodeir, Editor-in-Chief of Jazz Hot, saying, “I put Jack Teagarden to one side; I don’t like the dullness proper to his trombone and, as a singer, he doesn’t seem to me to have any other task except to serve as a foil for Louis – which he accomplishes rather well.” In those days, 1948, the divorce between “sour grapes” (the modernists, one of whose luminaries was none other than Hodeir) and “mouldy figs” (the supporters of traditional jazz, dominated by the tutelary figure of Panassié), was already consummated. And yet Hugues also esteemed that, “the specialities of Teagarden are fastidious.” For once, they agreed. Teagarden had an enormous flaw, you see—his original sin, in short—because he was white (and not only that, he was from Texas!) Most horrible of all, he’d played with Paul Whiteman for years. Unforgivable! Did Louis Armstrong have such atrocious taste that he abso-lutely wanted “T” and no other for his All-Stars? There was no shortage of good black trombonists. Was his taste so dreadful that, when the abominable, pale and insipid trombonist-singer expressed the desire to be left alone and go somewhere else, it made Louis feel almost ill—even more than when Earl Hines chose to do the same? Jack & Armstrong was one of those magic duos that only jazz could invent. Too bad for those who might think otherwise…

The first concert, on the 2nd, was the one which was aired (but not at a later time; this time it was really “live”, as testified by the numerous hitches which pepper it. However, it’s safe to say that both this concert and the one the following day resemble two peas in a pod. Besides, in his review in Jazz Hot (Issue N°21, March 1948), Hodeir didn’t fail to observe, with a zest of bitterness (especially with regard to the “specialities” of Bigard and Arvell Shaw), “… it all had an ‘old hat’ feeling, as those who listened to the Nice broadcasts and the first concert in Paris could confirm: you could hear the same effects in the same places. Where did the spontaneity and sincerity of black musicians go?” Did Hodeir, an often inspired composer and an intelligent, subtle arranger, really think that “spontaneity” was the cardinal virtue of jazz? Would he have you believe that the big-bands of Ellington or Gillespie—which he’d just heard in the same venue, and to which he referred in the same issue of his magazine—functioned only in a mode of strict improvisation that was pure and “sincere”?

It remains true that all these 1947-48 concerts—Nice, Paris, but also New York and Boston—come rather desperately from the same mould. Obviously, even if the festivities went on in different places sometimes very distant from each other, the audiences were very different too, and so they could help themselves to more or less the same thing every time. It’s logical not to make changes just for the sake of it, especially when the repertoire is solid and the band has had a lot of practise. But when you play first in Nice for a whole week, and then in Paris on two nights in a row—the same little country—, and when a sizeable part of it all has been wandering over the airwaves, well, it can be excessive.

Whatever, only the night of Tuesday March 2nd 1948 was aired by the station Paris-Inter. The specialist-magazines hardly mentioned it: only a brief note in Jazz Hot confirms the date. The consensus is that everything was done at the last-minute: no technical preparation, saturated sound, the imbalance between the voice of Louis and the instruments, almost inaudible introductions… On this last point, note the presence (at the beginning) of a double introduction: an anonymous voice pronouncing the name of the trumpeter as Armstrogne, and a lady, Madeleine Gautier, Panassié’s old accomplice, whose pronunciation is correct but who finds herself rapidly sidelined. Was this her baptism by fire? Had she never used a live microphone before? So she was in for a treat: covered by the music, cut off in her élan, asphyxiated… There is so much going on that the poor creature throws in the towel after four or five attempts and lets “Monsieur Armstrogne” sort it out on his own! It’s Louis who, after learnedly translating Tea for Two as “Thé pour deux”, announces the intermission after Steak Face, thanking Nice and the radio station. In the second part, he states that High Society, an old march annexed by ragtime- and jazz-people, was composed in New Orleans by Louis Armstrong in person! But we know of some recordings of it, with military and New York accents, which date from as early as 1910/1911! Strange…

Above all, Hodeir (already singled out elsewhere), began his review by fulminating against “…organizers who didn’t think it their duty to invite the editor-in-chief of the only specialist-magazine” while also deploring that “the price of seats was so high” (a thousand Francs for a decent one). He was all the more irritated since “the audience in the boxes and the seats to the front was composed of people with those insolent looks and unbearable manners which ordinarily belong to that social class made wealthy by war and the black market. (…) Those people didn’t like Louis or jazz. They were there because the papers had talked about Armstrong and the seats cost a thousand Francs.” It had to be said.

The concert reproduced on CD3 is incomplete. Recorded “simultaneously”, and apparently using the new “Philips-Miller” optical sound system (rapidly swept by magnetic tape), it was duplicated onto lacquers so as to permit repeat-broadcasts by distant stations. Too bad for Where the Blues Were Born which followed the jingle, and which isn’t among the themes played most often. But the copy which Irakli has is almost inaudible. The rest comes over better, i.e. the classic repertoire, with the usual good versions of stainless-steel standards: Royal Garden Blues, You Rascal You (known as Vieille Canaille in ancient Gaul), Back O’Town Blues, Mahogany Hall Stomp, On the Sunny Side of the Street, High Society, Basin Street Blues, Muskrat Ramble… There’s also a nice duet on That’s my Desire sung by Louis and Velma Middleton (whose funny acrobatic splits didn’t raise any smiles with serious musicologists). We avoided including the “specialty numbers” on which Satchmo intervenes briefly (or not at all), notably Lover and Stars Fell on Alabama (Teagarden) or the Bigard version of “Thé pour deux”. But we kept Catlett’s Steak Face and even the fastidious How High the Moon bestowed on the bassist. A special mention, on the other hand, goes to Earl Hines, so subtle and delicate on Someone to Watch over Me by Gershwin, a composer he hardly ever played. But Earl was always more inclined to play his own compositions anyway, or those of Fats Waller, an old pal who died too young; here he plays one of Waller’s most famous tunes, Honeysuckle Rose, this time with a brief but decisive contribution from Louis…

And so, with this homecoming at the Salle Pleyel, Louis Armstrong’s first post-war trip to Europe comes to an end, with a good chance that it won’t be the last. For our part, in the knowledge that an exhaustive set of his concerts is no obligation, we will be taking care to see that the next volumes will perhaps show a little more variety.

Adapted by Martin Davies from the French text by Daniel Nevers

Thanks to: Philippe Baudoin, Jean-Pierre Daubresse, Alain Delot, Yvonne Derudder, Jean Duroux, Pierre Lafargue and Clément Portais.

Very special thanks to: Irakli de Davrichewi and Annie Delahaye.

© 2015 Frémeaux & Associés

DISQUE / DISC 1

LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND THE ALL-STARS (New York City, 16/10/1947)

Louis ARMSTRONG (tp, voc) ; Weldon “Jack” TEAGARDEN (tb, voc) ; Albany “Barney” BIGARD (cl) ; Richard “Dick” CARY (p) ; Arvell SHAW (b) ; Sidney “Big Sid” CATLETT (dm).

1. A SONG WAS BORN (D.Raye-G.DePaul) (RCA-Victor 20-3064/mx.D7-VB-1082-1) 3’19

2. PLEASE STOP PLAYING THOSE BLUES (Demetrius-Moore) (RCA-Victor 20-2648/mx.D7-VB-1083-1) 3’16

3. BEFORE LONG (S.Catlett-C.Sigman) (RCA-Victor 20-3064/mx.D7-VB-1084-1) 2’52

4. LOVELY WEATHER WE’RE HAVING (J.Devries-J.Bushkin) (RCA-Victor 20-2648/mx.D7-VB-1085-1) 3’17

CARNEGIE HALL CONCERT (extraits/excerpts - New York City, 15/11/1947)

LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND THE ALL-STARS

Formation comme pour 1 à 4 / Personnel as for 1 to 4.

5. Intro & BACK O’TOWN BLUES (L.Armstrong-L.Russell) 5’53

6. BODY AND SOUL (Green-Sour-Heyman-Eyton) 6’08

7. STARS FELL ON ALABAMA (Perkins-Parrish) 5’35

8. HIGH SOCIETY (P.Steele) 4’10

9. BASIN STREET BLUES (Sp.Williams) 4’37

10. ROCKIN’ CHAIR (H.Carmichael) 5’07

11. I GOTTA RIGHT TO SING THE BLUES (T.Koehler-H.Arlen) & fin/closing 1’40

DUPLEX RADIO ENTRE L’AÉROPORT DE NEW YORK (station WQO) ET LE VOL AIR FRANCE SBAZJ “CONSTELLATION 48”, AU DESSUS DE L’ATLANTIQUE (19/02/1948) / BROADCAST LIVE BETWEEN THE NEW YORK AIRPORT (station WQO) AND THE AIR FRANCE FLIGHT SBAZJ “CONSTELLATION 48” (19/02/1948)

12. Part. I : Présentation par Roger GOUPILLÈRE, à propos de la traversée menant Louis Armstrong, Mezz Mezzrow et leurs orchestres au premier Festival de Jazz de Nice / Talking (in French) by Roger GOUPILLÈRE, about the crossing of the Atlantic by Louis Armstrong, Mezz Mezzrow and their bands to the first Nice Jazz Festival 3’31

13. Part.II : Suite et fin du duplex, avec brève jam-session par Armstrong, Mezzrow et leurs musiciens (H.Goodwin, J.Archey, J.Teagarden, B.Bigard, B.Wilbur…) / Concluded of the duplex, with short jam-session by Armstrong, Mezzrow and their musicians (“Dippermouth Blues”, “Royal Garden Blues”…) 2’45

ARRIVÉE À ORLY / ARRIVAL AT THE ORLY TERMINAL (20/02/1948)

14. Louis dit sa joie de revoir la France et les jazzmen français. Il chante quelques mesures de “Flat Foot Floogie”/ Louis says his pleasure to be in France again and to meet his French musicians friends. He sings a few bars of “Flat Foot Floogie” 2’47

FESTIVAL INTERNATIONAL DE JAZZ DE NICE – OUVERTURE (“Gala Constellation 48” - Nice Opéra, 22/02/1948)

15. Présentation des participants du premier Festival de Jazz de Nice / Presentation of the participants in the first Nice Jazz Festival. Par/by Gilbert CAZENEUVE & Roger PIGAUT 3’35

LOUIS ARMSTRONG & SON HOT FIVE (= ALL-STARS) (“Gala Constellation 48” – Nice Opéra, 22/02/1948)

Louis ARMSTRONG (tp, voc) ; Jack TEAGARDEN (tb, voc) ; A. Barney BIGARD (cl) ; Earl HINES (p) ; Arvell SHAW (b) ; Sidney “Big Sid” CATLETT (dm).

16. MUSKRAT RAMBLE (Ed.Ory) (78rpm acetate) 1’51

17. ROCKIN’ CHAIR (H.Carmichael) (78rpm acetate) 2’46

18. BOOGIE WOOGIE ON THE ST.LOUIS BLUES (W.C.Handy – arr.E.Hines) (Blank lbl78t, 30cm) 3’14

19. ROSE ROOM (Williams-A.Hickman) (78rpm acetate) 3’40

20. I GOTTA RIGHT TO SING THE BLUES (T.Koehler-H.Arlen) & fin/closing (78rpm acetate) 3’10

DISQUE / DISC 2

LOUIS ARMSTRONG & SON HOT FIVE (= ALL-STARS) (Nice Opéra, poss. 22 & 23/02/1948)

Louis ARMSTRONG (tp, voc) ; Jack TEAGARDEN (tb, voc) ; A. Barney BIGARD (cl) ; Earl HINES (p) ; Arvell SHAW (b) ; Sidney “Big Sid” CATLETT (dm).

1. WHEN IT’S SLEEPY TIME DOWN SOUTH (C.&O.René-C.Muse) (Blank lbl.78rpm, 30cm) 4’09

2. MAHOGANY HALL STOMP (Sp.Williams) (Blank lbl.78rpm, 30cm) 3’33

3. ROYAL GARDEN BLUES (C.&Sp.Williams) (AFG 13/mx.Part.8057 & 8058) 5’07

4. THEM THERE EYES (M.Pinkard-Tracy-Tauber) (Blank lbl.78rpm, 30cm) 4’20

5. PANAMA (W.H.Tyers) (AFG 12/mx.Part.8055) 4’20

6. ON THE SUNNY SIDE OF THE STREET (J.McHugh-D.Fields) & fin (Blank lbl.78rpm, 30cm) 6’47

LOUIS ARMSTRONG ET SON HOT FIVE (= ALL-STARS) (Nice Opéra, prob. 22 & 26/02/1948)

Formation comme pour 1 à 6 / Personnel as for 1 to 6. Plus Velma MIDDLETON (voc).

“Dear Old Southland”, duo/duet : L. ARMSTRONG (tp) & Earl HINES (p).

7. BLACK AND BLUE (T.W.Waller-A.Razaf) (Jazz Soc.AA613 & AFG 10/mx.Part.8051) 3’48

8. DEAR OLD SOUTHLAND (H.Creamer-T.Layton) (Blank lbl.78rpm, 30cm) 3’47

9. ROYAL GARDEN BLUES (C.&Sp.Williams) (Blank lbl.78rpm, 30cm) 4’45

10. MY MONDAY DATE (E.Hines) (AFG 11/mx.Part.8053 & 8054) 6’30

11. WHEN THE SAINTS GO MARCHIN’ IN (Trad.) (Blank lbl.78rpm, 30cm) 3’08

12. THAT’S MY DESIRE (H.Kresa-I.Loveday) (AFG 12/mx.Part.8056) 4’17

13. I CRIED LAST NIGHT (VELMA’S BLUES)(L.Armstrong-V.Middleton) (AFG 10/mx.Part.8052) 4’39

LOUIS ARMSTRONG ET SON HOT FIVE (=ALL-STARS) (Nice, Hôtel Négresco, 28/02/1948)

Formation comme pour 7 à 13 / Personnel as for 7 to 13.

14. Présentation (en suédois/in Swedish) & STEAK FACE (Trad.) (Blank lbl ;78rpm, 30cm) 6’02

15. AIN’T MISBEHAVIN’ (T.W.Waller-A.Razaf) (Blank lbl.78rpm, 30cm) 2’51

16. I CRIED FOR YOU (A.Lyman-G.Arnheim-A.Freed) (78rpm acetate) 4’39

17. BOOGIE WOOGIE ON THE ST. LOUIS BLUES (W.C.Handy – arr. E.Hines) (78rpm acetate) 4’39

ON THE NICE INTERNATIONAL JAZZ FESTIVAL by L. ARMSTRONG (Nice, Hôtel Négresco, 28/02/1948)

18. Brève interview de Louis ARMSTRONG par Loys CHOQUART pour la radio suisse (enr. Privé) / Short interview of Louis ARMSTRONG by Loys CHOQUART for the Swiss radio (private recording) 0’38

DISQUE / DISC 3

LOUIS ARMSTRONG & SON HOT FIVE (= ALL-STARS) Concert Salle Pleyel, Paris, 2/03/1948.

Louis ARMSTRONG (tp, voc) ; Jack TEAGARDEN (tb, voc) ; A. Barney BIGARD (cl) ; Earl HINES (p) ; Arvell SHAW (b) ; Sidney “Big Sid” CATLETT (dm) ; Velma MIDDLETON (voc).

Diffusion en direct/Broadcast live : Paris-Inter – Présentation : Madeleine GAUTIER (début/beginning) & X (Mr. “Armstrogne” !).

1. DEAR OLD SOUTHLAND (H.Creamer-T.Layton) (Jazz Soc.AA575/mx.SOF 1813) 3’51

2. BLACK AND BLUE (T.W.Waller-A.Razaf) (78rpm acetate) 4’13

3. ROYAL GARDEN BLUES (C.&Sp.Williams) (78rpm acetate) 5’07

4. YOU RASCAL YOU (S.Theard) (78rpm acetate) 4’27

5. HOW HIGH THE MOON (N.Lewis-N.Hamilton) (78rpm acetate) 5’08

6. SOMEONE TO WATCH OVER ME (G.&I.Gershwin) (Blank lbl.78rpm, 30cm) 2’50

7. HONEYSUCKLE ROSE (T.W.Waller-A.Razaf) (Blank lbl.78rpm, 30cm) 2’47

8. BACK O’TOWN BLUES (L.Armstrong-L.Russell) (Blank lbl.78rpm, 30cm) 4’48

9. STEAK FACE (Trad.) (78rpm acetate) 7’00

§* ENTR’ACTE / INTERMISSION *§

10. WHEN IT’S SLEEPY TIME DOWN SOUTH (Theme)(L.&O. René-C.Muse) (78rpm acetate) 1’07

11. MAHOGANY HALL STOMP (Sp.Williams) (78rpm acetate) 3’45

12. ON THE SUNNY SIDE OF THE STREET (J.McHugh-D.Fields) (Jazz Soc.AA574/mx.SOF 1811-1812) 6’50

13. HIGH SOCIETY (P.Steele) (Blank lbl.78rpm, 30cm) 3’38

14. BASIN STREET BLUES (Sp.Williams) (78rpm acetate) 3’50

15. BABY WON’T YOU PLEASE COME HOME (C.Williams-C.Warfield)(78rpm acetate) 2’47

16. I CRIED LAST NIGHT (L.Armstrong-V.Middleton) (Jazz Soc.AA572/mx.SOF 1807-1808) 5’35

17. THAT’S MY DESIRE (H.Kresa-I.Loveday) (78rpm acetate) 4’45

18. MUSKRAT RAMBLE (Ed.Ory) (78rpm acetate) 5’49