- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

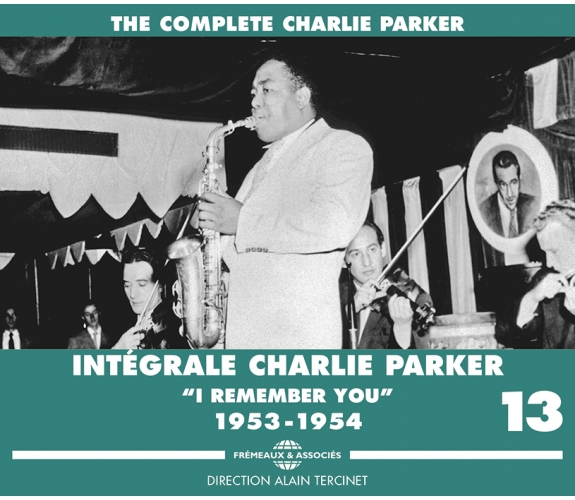

CHARLIE PARKER

CHARLIE PARKER

Ref.: FA1343

Artistic Direction : ALAIN TERCINET

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Total duration of the pack : 4 hours 56 minutes

Nbre. CD : 4

CHARLIE PARKER

CHARLIE PARKER

“Bird would throw his genius out of every window. And then one day, his instrument. And then on another day, the instrument of that instrument, this man full of candour and enigma who talked to the birds.” Alain GERBER

The aim of 'The Complete Charlie Parker', compiled for Frémeaux & Associés by Alain Tercinet, is to present (as far as possible) every studio-recording by Parker, together with titles featured in radio-broadcasts. Private recordings have been deliberately omitted from this selection to preserve a consistency of sound and aesthetic quality equal to the genius of this artist.

MARY LOU WILLIAMS • THE INTERNATIONAL SWEETHEARTS OF...

GROOVIN' HIGH - 1940-1945

“LAIRD BAIRD” 1952-1953

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1In The Still Of The NightCharlie ParkerCole Porter00:03:271953

-

2Old FolksCharlie ParkerW. Robinson00:03:371953

-

3If I Love AgainCharlie ParkerB. Oakland00:02:301953

-

4Announcement 1Charlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:00:391953

-

5Cool Blues 1Charlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:05:361953

-

6Announcement 2Charlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:00:101953

-

7Scrapple From The Apple 1Charlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:07:021953

-

8Announcement 3Charlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:00:571953

-

9LauraCharlie ParkerD.Raskin00:06:331953

-

10Closing AnnouncementCharlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:00:341953

-

11Ornithology 1Charlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:05:011953

-

12Out Of Nowhere 1Charlie ParkerJ. Green00:05:451953

-

13My Funny Valentine 1Charlie ParkerR. Rogers00:06:371953

-

14Cool Blues 2Charlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:06:531953

-

15Chi-Chi 1Charlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:03:081953

-

16Chi-Chi 2Charlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:02:451953

-

17Chi-Chi 3Charlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:03:051953

-

18I Remember YouCharlie ParkerV. Schertzinger00:03:051953

-

19Now's The Time 1Charlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:03:031953

-

20ConfirmationCharlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:02:571953

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Now's The Time 2Charlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:04:181953

-

2Don't Blame MeCharlie ParkerJ. McHugh00:05:001953

-

3Dancing In The CeilingCharlie ParkerR. Rodgers00:02:301953

-

4Cool Blues 3Charlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:04:501953

-

5Groovin' High 1Charlie ParkerDizzy Gillespie00:05:091953

-

6Ornithology 2Charlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:02:541953

-

7BarbadosCharlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:04:031953

-

8Cool Blues 4Charlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:05:421953

-

9Announcement 4Charlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:00:141953

-

10Ornithology 3Charlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:07:511953

-

11Introduction 1Charlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:00:281953

-

12My Little Suede Shoes 1Charlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:07:161953

-

13Introduction 2Charlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:00:291953

-

14Now's The Time 3Charlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:07:051953

-

15Groovin' High 2Charlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:06:101953

-

16Announcement 5Charlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:00:211953

-

17CherylCharlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:05:471953

-

18Introduction 3Charlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:00:041953

-

19Ornithology 4Charlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:06:291953

-

2052nd Street ThemeCharlie ParkerThelonius Monk00:01:321953

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Announcement 6Charlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:00:211954

-

2Ornithology 5Charlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:06:471954

-

3Announcement 7Charlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:00:191954

-

4Out Of Nowhere 2Charlie ParkerJ. Green00:09:321954

-

5Announcement 8Charlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:00:321954

-

6Cool Blues 5Charlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:06:521954

-

7Announcement 9Charlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:00:451954

-

8Scrapple From The Apple 2Charlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:04:371954

-

9Now's The Time 4Charlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:09:101954

-

10Announcement 10Charlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:00:491954

-

11Out Of Nowhere 3Charlie ParkerJ. Green00:05:431954

-

12My Little Suede Shoes 2Charlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:05:051954

-

13Jumpin With Symphony Sid 1Charlie ParkerLester Young00:01:111954

-

14Cool Blues 6Charlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:06:221954

-

15Announcement 11Charlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:01:021954

-

16Ornithology 6Charlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:07:351954

-

17Announcement 12Charlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:01:221954

-

18Out Of Nowhere 4Charlie ParkerJ. Green00:04:221954

-

19Jumpin' With Symphony Sid 2Charlie ParkerLester Young00:02:341954

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Night And DayCharlie ParkerCole Porter00:03:031954

-

2My Funny Valentine 2Charlie ParkerR. Rodgers00:03:201954

-

3CherokeeCharlie ParkerR. Noble00:02:591954

-

4I Get A Kick Out Of You 1Charlie ParkerCole Porter00:04:531954

-

5I Get A Kick Out Of You 2Charlie ParkerCole Porter00:03:351954

-

6Just One Of Those ThingsCharlie ParkerCole Porter00:02:431954

-

7My Heart Belongs To DaddyCharlie ParkerCole Porter00:03:211954

-

8I've Got You Under My SkinCharlie ParkerCole Porter00:03:351954

-

9What Is This Thing Called LoveCharlie ParkerCole Porter00:02:161954

-

10RepetitionCharlie ParkerNeal Hefti00:02:441954

-

11Easy To LoveCharlie ParkerCole Porter00:02:131954

-

12East Of The SunCharlie ParkerB. Bowman00:03:431954

-

13The Song Is YouCharlie ParkerJ. Kern00:04:411954

-

14My Funny Valentine 3Charlie ParkerR. Rodgers00:02:021954

-

15Cool Blues 7Charlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:03:011954

-

16Love For Sale 1Charlie ParkerCole Porter00:05:311954

-

17Love For Sale 2Charlie ParkerCole Porter00:05:331954

-

18I Love Paris 1Charlie ParkerCole Porter00:05:071954

-

19I Love Paris 2Charlie ParkerCole Porter00:05:071954

CLICK TO DOWNLOAD THE BOOKLET

Parker vol.13 FA1343

INTÉGRALE Charlie Parker

“I REMEMBER YOU”

1953-1954

Volume 13

DIRECTION ALAIN TERCINET

Proposer une véritable « intégrale » des enregistrements laissés par Charlie Parker est actuellement impossible et le restera longtemps. Peu de musiciens ont suscité de leur vivant autant de passion. Plus d’un demi-siècle après sa disparition, des inédits sont publiés et d’autres – dûment répertoriés – le seront encore. Bon nombre d’entre eux ne contiennent que les solos de Bird car ils furent enregistrés à des fins privées par des musiciens désireux de disséquer son style. Sur le seul plan du son, ils se situent en majorité à la limite de l’audible voire du supportable. Faut-il rappeler, qu’à l’époque, leurs auteurs employaient des enregistreurs portables sur disque, des magnétophones à fil, à bande (acétate ou papier) et autres machines devenues obsolètes, engendrant des matériaux sonores fragiles ?

Aucun solo joué par Charlie Parker n’est certes négligeable, toutefois en réunissant chronologiquement la quasi-intégralité de ce qu’il grava en studio et de ce qui fut diffusé à l’époque sur les ondes, il est possible d’offrir un panorama exhaustif de l’évolution stylistique de l’un des plus grands génies du jazz ; cela dans des conditions d’écoute acceptables.

Toutefois lorsque la nécessité s’en fait sentir stylistiquement parlant, la présence ponctuelle d’enregistrements privés peut s’avérer indispensable. Au mépris de la qualité sonore.

L’intégrale CHARLIE PARKER

STUDIO & RADIO VOL. 13

“I REMEMBER YOU” 1953-1954

«J’aimerais faire une séance avec cinq ou six bois, une harpe, un chœur et une section rythmique au complet. Quelque chose dans la veine de la Kleine Kammermusik de Hindemith. Pas une copie, je ne veux jamais copier, mais quelque chose de similaire (1). » Le 25 mai, Parker aurait pu croire que son rêve se réaliserait grâce à Gil Evans. Un ami de longue date qui, quelques années auparavant, avait conçu pour lui le nonette que, finalement, Miles Davis rendra célèbre.

Norman Granz détestant les répétitions, les séances devaient être menées tambour battant. L’exact contraire des habitudes de Gil Evans qui travaillait ses partitions sur le vif, multipliant corrections, repentirs et variantes. « Ce qui survint ce jour ne m’a pas fait ranger Norman Granz parmi mes personnages favoris. Nous avions assez de musique pour faire un album entier mais il fallait que nous répétions. J’avais un quintette de bois, Dave Lambert un ensemble vocal et, en sus, la section rythmique de Charlie… aussi il aurait fallu répéter un petit peu les morceaux. En plus, à la date de la séance, Max Roach devait participer à un concert. Il lui fallut donc s’éclipser pour aller jouer une heure quelque part, ce qui rendait indispensable le recours à un remplaçant jusqu’à son retour. Ce détail énerva Norman Granz, déjà aux prises avec un matériel déficient ; il arrêta tout - en plein milieu de la séance – nous disant seulement « OK, ça suffit… Bonne nuit » (2). »

Certes le manque de répétitions entraîna la désintégration d’un beau projet mais en fut tout autant responsable une erreur de casting dénoncée par Hal McKusick : « Les parties vocales étaient d’une certaine façon trop compliquées. Les partitions de Gil étaient magnifiques et complexes comme à l’habitude, ses arrangements vous obligeaient à vous dépasser, musicalement parlant. Les partitions vocales de Dave, elles, étaient trop denses et lorsque tout le monde s’en rendit compte, il était trop tard. La séance d’enregistrement était lancée (3). » Hal McKusick se demandait d’ailleurs pourquoi les parties vocales n’avaient pas été, elles aussi, confiées à Gil Evans qui aurait utilisé seulement un quatuor. Les prises publiées – composites - contiennent cependant quelques beaux moments, ainsi le cheminement de Bird au milieu des voix de Old Folks ou l’introduction de If I Love Again. Sur In the Still of the Night, Parker s’envole en prenant appui sur des parties vocales somme toute banales.

Lorsque Gil Evans et Dave Lambert écoutèrent les épreuves, ils constatèrent que l’ingénieur du son s’était trompé dans la balance : les voix submergeaient orchestre, soliste et rythmique. Après avoir consulté Parker, ils proposèrent de refaire gratuitement la séance. Granz refusa, laissant ainsi à l’état de brouillon ce qui promettait d’être un moment rare dans l’œuvre enregistrée de Parker.

Au mois de juin, Parker fut engagé une nouvelle fois au Hi-Hat Club à Boston. Un établissement bruyant qui, contrairement à son concurrent le Storyville, ne s’inquiétait guère d’assurer les meilleures conditions d’écoute à ses clients. Cette fois le trompettiste Herb Pomeroy remplacerait Joe Gordon indisponible. Par son goût de la mélodie et sa sensibilité, il entrait dans la catégorie de trompettistes chers à Bird, allant de Miles Davis à Chet Baker en passant par Tony Fruscella et Don Joseph. « Je me souviens de la première fois que j’ai travaillé au Hi-Hat avec Charlie Parker. Évidemment, avant de jouer avec lui, j’étais déjà venu l’écouter. Le club était en étage, au deuxième, et je me rappelle qu’en montant l’escalier mes genoux tremblaient. Ils tremblaient vraiment. Juin 1953… c’était l’année, la semaine même, où j’aurais dû recevoir mon diplôme si j’étais resté à Harvard (4). » Au piano, Dean Earl chargé alors des interludes musicaux au Hi-Hat, à la basse Bernie Briggs, l’un des piliers de la scène jazzistique bostonienne, tout comme le batteur Bill « Baggy » Grant. Efficace, attentive, une formation qui fournissait à Parker le soutien adéquat pour qu’il put exercer son imagination sur des thèmes mille fois joués comme Cool Blues, Scrapple from the Apple ou Ornithology. Seules nouveautés, Laura jusque-là réservé à l’orchestre à cordes et My Funny Valentine que Gerry Mulligan et Chet Baker avaient remis au goût du jour l’année précédente.

Durant cet engagement, John McLellan réalisa une interview de Bird accompagnée d’une écoute de disques. Parker exprima son admiration pour My Lady qui mettait en valeur Lee Konitz chez Stan Kenton et salua ce dernier pour les innovations qu’il avait introduites dans le jazz. Interprété par Stan Getz au Storyville, Cherokee recueillait également ses suffrages.

L’exactitude n’avait jamais été la vertu cardinale de Bird. Le début d’une nouvelle séance en quartette était fixé à midi. Il arriva à deux heures et quart. Pour ne pas s’attarder. Quarante-cinq minutes plus tard, les quatre morceaux de rigueur étaient en boîte : Chi-Chi, une composition offerte par Parker à Max Roach qui l’avait gravée trois mois plus tôt, Confirmation, I Remember You un standard, et Now’s The Time dans une nouvelle version.

Journaliste et occasionnellement organisateur de concert, Bob Reisner avait inauguré, le 26 avril, les « Jazz Nights » du dimanche soir à l’Open Door situé à Greenwich Village. Bird s’y produira. Quelques enregistrements privés d’une qualité plus que médiocre ont été réalisés au cours de son passage en juillet. En septembre, il s’y fera accompagner par Thelonious Monk, Charles Mingus et Roy Haynes. Sans laisser la moindre trace enregistrée, semble-t-il.

Comme convenu avec George Wein, Parker revint au Storyville de Boston en compagnie cette fois de Kenny Clarke. Tous deux retrouvaient Herb Pomeroy, Sir Charles Thompson, un pianiste sous la houlette duquel Bird avait enregistré en 1945 et Jimmy Woode à la basse. Au cours de la seule soirée retransmise, la WDHD éprouva le besoin d’interrompre Dancing in the Ceiling pour donner les ultimes estimations concernant une élection locale.

George Wein jouait au Mahagonny Hall situé sous le Storyville en compagnie de Doc Cheatham, Vic Dickenson et Al Drootin. À l’occasion de la jam traditionnelle du dimanche, tous vinrent se joindre à Parker. « Rien ne nous avait préparé à cette puissance. Bird réinventait le blues sans s’éloigner de son essence. Quant à sa force rythmique, elle était prodigieuse ; assis sur mon tabouret derrière le piano, je pouvais le sentir se dégager du rang à la manière d’un pur-sang. Ce Royal Garden Blues fut la seule occasion que j’ai eu de jouer avec Bird et cette expérience reste gravée dans ma mémoire (5). »

Durant une dizaine de jours, Bird partit en Californie participer, en compagnie des quartettes de Chet Baker et de Dave Brubeck, à la série de concerts « West Coast in Jazz ». L’accompagneraient Jimmie Rowles, Carson Smith et Shelly Manne, en fait la rythmique de Chet. Ravi de retrouver ce dernier, Parker l’invitait régulièrement à le rejoindre sur scène. La tournée fut émaillée d’incidents divers et Bird emprunta plus d’une fois l’alto de Paul Desmond pour avoir mis le sien au clou. Seule en subsiste une dizaine de minutes tirées d’un concert donné à l’Université d’Oregon. Barbados - un thème que Parker ne reprenait plus guère - débute de façon inhabituelle par un solo de Shelly Manne. Malgré les coupes, les fragments de Cool Blues méritent d’être entendus en raison de la série de 4x4 partagés entre Bird, Chet et Shelly.

À l’issue de divers engagements à Chicago, Baltimore et Philadelphie, Parker retrouva le Hi-Hat en décembre 1953 et janvier 1954. Ont survécu un certain nombre de retransmissions radiophoniques affligées, dès l’origine, d’une prise de son approximative que les copies successives n’ont en rien amélioré y ajoutant même diverses coupures. Comme l’avaient fait les radios réalisées en 1948/49 depuis le Royal Roost, elles montrent Bird en action durant un laps de temps réduit. Pour le meilleur et, disons-le, pour le moins convaincant. Contrairement à ce qu’il avait fait précédemment en ce même lieu avec Joe Gordon, Dick Twardzik ou Herb Pomeroy, Bird n’entame jamais un véritable dialogue avec ses nouveaux interlocuteurs : Herbie Williams, un trompettiste à l’imagination limitée, Rollins Griffith, Jimmy Woode et Marquis Foster, venus de la scène du jazz bostonien. Rarement au mieux de sa forme, Parker les laisse s’exprimer longuement. À Doris, son épouse légitime venue le voir au Hi-Hat, il avoua rencontrer des difficultés à créer.

Interviewé par John McLellan et Paul Desmond, Bird avait exprimé son désir de retourner étudier à Paris, racontant ses rencontres avec Edgar Varèse : « Il était très gentil avec moi et acceptait de me servir de professeur. Il voulait composer quelque chose qui me serait destiné. » Malheureusement le compositeur quitta alors les USA pour retourner en France à l’occasion de la création de son œuvre, Déserts (6).

Une fois l’engagement au Hi-Hat terminé, Charlie Parker rejoignit la tournée « Festival of American Jazz » rassemblant l’orchestre de Stan Kenton, le trio d’Erroll Garner, June Christy, Dizzy Gillespie et Candido. Bird y remplaçait à la dernière minute Stan Getz sous le coup d’une inculpation pour usage de stupéfiants : sur certaines affiches figurait toujours le nom de ce dernier. En tant qu’invité de l’orchestre Kenton, Parker se produisait à trois reprises sur My Funny Valentine arrangé par Bill Holman, Night and Day transposé à partir de la partition conçue par Joe Lippman pour l’orchestre à cordes et Cherokee. Un rattrapage de dernière minute, Parker ayant refusé d’annexer Zoot destiné à Zoot Sims. Les trois enregistrements venus du Civic Auditorium de Portland donnent à entendre Bird à nouveau au sommet de son art.

La tournée achevée, Bird fit scandale au Tiffany Club où il devait se produire en compagnie du trio de Joe Rotondi. Soupçonné d’usage de substances illicites, il sera alors mis en examen par le LAPD (Los Angeles Police Department). L’ineffable John Edward O’Grady, patron de la brigade des stupéfiants d’Hollywood, écrira dans ses mémoires : « J’ai viré de Los Angeles le grand saxophoniste Charlie « Yardbird » Parker. J’aurais pu le coincer. Ses bras étaient couverts de piqûres. Mais il était trop vieux et c’était un alcoolique. J’ai décidé que ça ne valait pas la peine de perdre son temps à le coffrer pour que la ville de Los Angeles l’entretienne (7). »

Ce ne fut pas O’Grady qui poussa Bird à retourner à New York, mais l’annonce du décès de sa fille Pree. Contraint d’emprunter 500 $ à l’impresario Billy Shaw pour régler ses funérailles, Parker se trouvait aux prises avec d’insolubles problèmes financiers. D’autant plus que le Syndicat venait de lui infliger une amende en raison de son attitude au Tiffany Club.

Bouleversé par la disparition de sa fille, Bird entamera, lentement mais sûrement, une descente aux enfers. En raison de son manque de fiabilité et de ses foucades, les engagements se raréfiaient. Parker devait enregistrer en quartette la première partie d’un album consacré aux compositions de Cole Porter. Croisant sur son chemin le guitariste Jimmy Darr, sur un coup de tête il l’amena au studio avec lui. I Get a Kick Out of You accumula faux départs, prises partielles ou insatisfaisantes ; deux versions complètes seront cependant publiées. Parker batailla sans conviction avec My Heart Belongs to Daddy plaçant une citation mal venue de Woody Woodpecker Song et démonta I’ve Got You Under My Skin sans pour autant le reconstruire de façon irréfutable. Mal à l’aise avec Just One Of Those Things, il stoppa brutalement son premier chorus.

À partir du 14 août, Parker fut engagé pour une semaine à l’Apollo Theatre. De la grande formation qui l’accompagnait, il ne reste qu’une photo où figurent Benny Harris, Charlie Rouse, Sahib Shihab, Bennie Green et Gerry Mulligan. Ce dernier dira : « Il était en train de sombrer. J’en ai pleuré. Son jeu était au mieux exhubérance, au pire vélocité gratuite ; toujours contrôlé cependant. Ce qui manquait, c’était cette sorte de gentillesse qu’il savait irradier (8). » Bird multiplia les esclandres. Au Birdland, la station WABC diffusait le 27 août un set de sa prestation en compagnie de son orchestre à cordes. Répertoire inchangé, interprétations habituelles. Deux jours plus tard, il annonce East of the Sun et attaque… Dancing in the Dark. Panique dans les rangs. Après les avoir insultés, Parker licencia ses musiciens devant une assistance médusée.

Rentré chez lui, il aurait avalé le contenu d’un flacon de teinture d’iode. Vrai ou faux suicide ? Al Cotton : « Charlie a ainsi expliqué sa tentative de suicide à l’acide iodique après qu’il eut été viré du Birdland : il me fallait avoir recours à une solution extrême pour sortir de mon marasme financier. J’allais perdre mon métier ; au plan légal, ils pouvaient avoir ma peau. Je n’aurais jamais pu rembourser toutes mes dettes ; mais, si on me considérait comme fou, je ne pouvais pas être tenu pour responsable. J’ai donc enduit mes lèvres et ma langue d’un peu d’acide iodique, j’ai mis de l’eau savonneuse dans ma bouche, j’ai joué à fond la comédie, et j’ai été reconnu inadapté mental. Je ne pouvais donc être tenu pour légalement responsable (9). » Rodomontade ou aveu ?

Transporté à l’hôpital de Bellevue, il en sortira rapidement pour y retourner trois semaines plus tard, de son propre chef cette fois, pour soigner son alcoolisme. Entre temps, il s’était produit sur la scène de Carnegie Hall, à l’occasion d’un concert donné par le « Birdland All Stars of ’54 ». Accompagné par les trois quarts du Modern Jazz Quartet, il y livra une courte prestation qui n’ajoutera ni ne retirera rien à sa gloire.

Pensant sincèrement s’en sortir, Bird décida de s’installer avec Chan à la campagne, à New Hope. Dans les coulisses de Town Hall, il parlera à Leonard Feather de ce nouveau départ. Las, bientôt il quitta Chan pour une vie d’errance dans New York sans même un instrument à lui. Afin de se joindre au trio d’Al Levitt à l’Arthur’s Tavern, il empruntait l’alto de Jackie McLean, le ténor de Brew Moore ou la clarinette de Sol Yaged. Phil Woods accompagnait un spectacle de strip-tease en interprétant sans relâche Harlem Nocturne. Au cours d’une pause, il découvrit Parker aux prises avec le saxophone baryton du peintre Larry Rivers. Il lui passa alors son alto et, dira-t-il, Bird montra que, jusqu’au bout, il pouvait rester égal à lui-même.

Le 2 décembre, Parker devait terminer l’album consacré à Cole Porter. D’excellente humeur, il arriva en avance au studio, sans doute pour croiser Lester Young qui y enregistrait avant lui. Billy Bauer qui remplaçait heureusement Jimmy Darr dira : « Il utilisait les premières prises en guise de répétitions, d’explication musicale de ce qu’il voulait. Il nous dirigeait, il nous apprenait. Une fois content de Love for Sale, il nous a expliqué I Love Paris : il avait en tête la façon dont il voulait que ce soit présenté (10). » Rien de commun avec la séance précédente.

Leonard Feather : « Je le revis parmi le public du Basin Street, il vint à notre table, s’agenouilla près de moi et resta au moins dix minutes dans cette position de prostration, refusant de s’asseoir, ne cherchant rien d’autre que l’attention de quelqu’un qu’il considérait comme un ami. C’est alors que j’ai compris que Charlie Parker voulait mourir (11). »

Le 4 mars 1955, la direction du Birdland décida de lui redonner une chance. L’affiche annonçait « Exceptionnellement ce soir, en supplément de programme : Charlie Parker, Bud Powell, Charlie Mingus, Art Blakey et Kenny Dorham. » Marcel Zanini : « Charlie Parker est arrivé (Kenny Dorham était déjà en place). Puis Mingus qui a accordé sa basse. Et Bud Powell qui semblait totalement absent. Il était devant son piano mais ne le touchait pas… Tout se passait dans l’indifférence générale. Il y avait beaucoup de monde car c’était un samedi. Mais personne ne s’intéressait à ce qui se passait sur scène. Parker lança un titre à Bud Powell. Ce dernier joua l’introduction de Little Willie Leaps puis s’arrêta. Mingus posa sa basse par terre. Parker le vit partir, et, tout en jouant d’une seule main, le rattrapa et lui fit signe de continuer à jouer. Là dessus arriva Blakey qui s’installa à la batterie. Finalement Bud Powell se retourna vers le public, tournant le dos au piano, les coudes sur le clavier, le regard « out of this world ». Un drame se passait ; le public était toujours indifférent. Parker, Mingus et Blakey ont joué seuls. Ils ont joué le blues. Avec un volume… comme des dingues. Moi, je prenais des photos… (12) » Nat Hentoff ajouta que Bud Powell et Parker échangèrent une bordée d’injures et que, au départ du pianiste, penché sur le micro Bird psalmodia un long moment le nom de Bud Powell. C’est alors que Mingus se désolidarisera de ses partenaires, les traitant publiquement de « malades »…

George Wein : « La dernière fois que j’engageais Bird appartient à l’histoire. Sa troisième apparition devait être l’affaire d’un week-end qui aurait débuté le 9 mars 1955 […] Il ne lui était pas inhabituel de faire sauter un engagement, sans avertissement ni excuse. Aussi, lorsque arriva au Storyville le premier soir du passage de Bird sans Bird, j’étais embêté. Nous avions une salle pleine de clients, une section rythmique, et pas d’attraction. « Bon, je me suis dit, résigné, Bird a déconné une fois de plus » (13). »

S’apprêtant à partir pour Boston la veille, Parker s’était arrêté à l’hôtel Stanhope où habitait l’amie et mécène de nombreux musiciens, la baronne Pannonica de Kœnigswarter (14). Il se plaignit de douleurs à l’estomac mais refusa d’être hospitalisé. Son hôtesse fit venir un médecin qui, interrogeant Bird sur ses habitudes concernant la boisson, s’attira comme réponse « Je m’autorise parfois un petit verre de sherry avant le dîner »…

Nica décida de garder Parker chez elle le temps qu’il se remette. Le 12 était diffusé à la télévision le show de Tommy Dorsey, musicien qu’admirait Bird. Il s’installa face au poste et, devant un numéro d’acrobates comiques, partit d’un éclat de rire qui lui fut fatal.

Le médecin appelé attribua la raison du décès à une pneumonie, affirmant qu’il se trouvait devant la dépouille d’un homme âgé d’environ cinquante-trois ans. Bird en avait trente-cinq. Son corps fut transporté anonymement au Bellevue Hospital car, ignorant l’adresse de Chan, Nica de Kœnigswarter ne voulait pas qu’elle apprit la nouvelle par la presse. Ce qui n’empêcha pas le New York Mirror de titrer : « Le Roi du Bop décède dans l’appartement de l’héritière ».

Un service funèbre fut célébré à la New York Abyssinian Baptist Church et le 2 avril, de minuit à trois heures du matin, se déroula à Carnegie Hall un concert à la mémoire de Bird. S’y produisirent Lester Young, Thelonious Monk, Horace Silver, Kenny Dorham, Art Blakey, Kenny Clarke, Oscar Pettiford, Gerry Mulligan, Dizzy Gillespie, Mary Lou Williams, Billie Holiday, Stan Getz, Sammy Davis Jr., Charles Mingus, entre autres… Particulièrement ambigüe, la situation matrimoniale de Parker fut la cause d’un imbroglio conjugal et familial. Contre sa volonté selon Chan mais conformément au désir de sa mère, il fut inhumé à Kansas City.

Le 27 mars 1999, y sera inauguré, à proximité de l’American Jazz Museum, le « Charlie Parker Memorial Plaza ». Un monument dont la stèle supportant une tête en bronze de plus de trois mètres due au sculpteur Robert Graham, ne comporte qu’une phrase : « Bird Lives ». Une évidence qui, au fil des ans, déborda les limites étroites du monde du jazz. Dès 1964, un ancien étudiant en art graphique devenu le batteur des Rolling Stones, Charlie Watts, rédigea et dessina « Ode to a Flying Bird ». Un album pour enfants, dédié à Charlie Parker, racontant l’histoire d’un oiseau saxophoniste de génie.

En 1988, Clint Eastwood tourna « Bird » dans lequel Forest Whitaker incarnant Parker, le faisait connaître à des spectateurs qui, jusque là, ignoraient même son nom. « Bird Lives ! » sera le titre même d’une pièce de Willard Manus jouée en 2014 au Chromolume Theater at the Attic de Los Angeles. L’année suivante, au mois de juin, fut représenté à l’Opéra de Philadelphie « Yardbird », un opéra en un acte pour quinze interprètes composé par Daniel Schnyder. Pour ne rien dire des hommages – innombrables et parfois surprenants – rendus par ses pairs. Et, soixante années plus tard, l’ensemble de son legs enregistré ne semble pas encore avoir été épuisé.

Alain Tercinet

© 2017 Frémeaux & Associés

(1) Nat Hentoff, « Counterpoint », Down Beat, 20 janvier 1953.

(2) Ken Vail, « Bird’s Diary », Chessington, Castle Communications, 1995.

(3) Hal McKusick, « Charlie Parker and Voices, part 1 », JazzWax, internet.

(4) Richard Vacca, « The Boston Jazz Chronicles », Troy Street Publishing, LLC, Belmont, Massachussets, 2012.

(5) George Wein with Nate Chinen, « Myself Among Others – A Life in Music », Da Capo Press, 2003.

(6) En 1957, Edgar Varèse s’intéressa aux jam sessions organisées par Teo Macero et le compositeur Earl Brown auxquelles participèrent Art Farmer, Hal McKusick, Hall Overton, Charles Mingus. Des enregistrements donnent à entendre Varèse discutant avec les musiciens.

(7) John O’Grady & Nolan Davis, « O’Grady : the Life and Times of Hollywood n°1 Private Eye », J. P. Tarcher Inc. L.A., 1974.

(8) Gary Giddins, « Celebrating Bird – Le triomphe de Charlie Parker », NYC 1987 – trad. Alain-Pierre Guilhon, Denoël, Paris, 1988.

(9) Robert Reisner, « La légende de Charlie Parker », trad. François Billard et Catherine Weinberger-Thomas, Pierre Belfond, 1989.

(10) Livret de « The Complete Charlie Parker on Verve ».

(11) Leonard Feather in « Charlie Parker intime », Jazz Hot n°261, mai 1970.

(12) Alex Dutilh, « New York, 1954-58, Marcel Zanini se souvient », Jazz Hot n° 328, juin 1976.

(13) comme (5)

(14) Apparentée à la famille Rotschild, épouse d’ambassadeur, ambulancière dans les Forces Françaises Libres en Afrique, la baronne Pannonica « Nica » de Koenigswarter (1913-1988) consacra une partie de sa fortune à venir en aide aux musiciens de jazz afro-américains en difficulté. Dans sa maison de Weehawken, elle hébergea Thelonious Monk durant les dernières années de sa vie. Un ouvrage conçu par sa petite fille Nadine de Koenigswarter réunissant les photos polaroïd que Nica avait prises à son domicile constitue un document exceptionnel (Pannonica de Koenigswarter, « Les musiciens de jazz et leurs trois vœux », Buchet Chastel, Paris, 2006 - « Three Wishes – An Intimate Look at Jazz Greats », Harry N. Abrams Inc., NYC, 2008.)

NOTES DISCOGRAPHIQUES

BIRD AT THE HI-HAT

La répartition et la datation des interprétations venues des passages radiodiffusés de Charlie Parker au Hi-Hat Club de Boston varient selon les discographies. L’ordre proposé ici n’a pas la prétention d’être définitif.

Ornithology / Out of Nowhere / My Funny Valentine / Cool Blues (Hi-Hat, juin 1953)

Ces quatre interprétations conservées sans aucune annonce ont été datées faussement du 18 janvier 1954. La présence d’Herb Pomeroy à la trompette les situent entre le 8 et le 14 juin 1953 car en janvier 1954, il était en tournée hors de Boston. La présence de Dean Earle au piano est évidente mais il est plus difficile d’identifier le bassiste et le batteur.

Cheryl / Ornithology / 52nd Street Theme (Hi-Hat,18 & 20 Décembre 1953)

Certaines éditions rattachent de façon erronée ces trois morceaux à la diffusion radiophonique du 14 juin 1953 alors que le trompettiste est Herbie Williams et non Herb Pomeroy et que le pianiste n’est pas Dean Earle. De plus la citation faite par Bird de Santa Claus is Coming to Town durant son solo d’Ornithology incite à les dater du mois de décembre.

Dans la deuxième version d’Ornithology, une saute de sillon présente dans toutes les copies survient durant le solo de Rollins Griffith.

Hi-Hat (24 Janvier 1954)

A été interprétée également une version de My Little Suede Shoes. Dans toutes les copies manquent l’exposé du thème et l’essentiel de l’improvisation de Parker. Pour cette raison, ce morceau n’a pas été retenu ici.

A genuine “complete” set of the recordings left by Charlie Parker is impossible today and will remain so for a long time to come. Few musicians aroused so much passion during their own lifetimes and today, more than half a century after his disappearance, previously-unreleased music is published, and other titles – duly listed – will also come to light. A good many contain only solos by Bird, as they were recorded – privately – by musicians wanting to dissect his style. Regarding their sound-quality, most of them are at the limit: barely audible, sometimes almost intolerable, but in fact understandable: those who captured these sounds used portable recorders that wrote direct-to-disc, or wire-recorders, “tapes” (acetate or paper) and other machines now obsolete. Obviously they all produced sound-carriers that were fragile.

Of course, no solo ever played by Charlie Parker is to be disregarded. But a chronological compilation of almost everything he recorded – either inside a studio or on radio for broadcast purposes – does make it possible to provide an exhaustive panorama of the evolution of his style (Parker was, after all, one of the greatest geniuses in jazz), and to do so under acceptable listening-conditions. However, since we refer to style, the occasional presence here of some private recordings is indispensable, whatever the quality of the sound.

THE COMPLETE CHARLIE PARKER

STUDIO & RADIO VOLUME 13

“I REMEMBER YOU” 1953-1954

“Now, I’d like to do a session with five or six woodwinds, a harp, a choral group, and a rhythm section; something on the line of Hindemith’s ‘Kleine Kammermusik’. Not a copy or anything like that. I don’t want ever to copy. But that sort of thing.” (1) On May 25th Parker might have thought his dream was being fulfilled thanks to Gil Evans. Gil was an old friend, and a few years earlier he’d conceived a nonet for Parker that would finally become famous with Miles Davis.

Norman Granz used to hate rehearsals and so the sessions had to be conducted briskly. This was the exact opposite to Gil Evans’ customary practise: he used to work on his scores on the spot, multiplying his corrections, variations and changes of mind complete with emendations. “What happened that day made Norman Granz not one of my favourite people, because we had enough music for an album but we had to rehearse the music. I had a woodwind quintet, and Dave Lambert had a vocal group, and then Charlie’s rhythm section… so we had to rehearse the numbers a little bit. Also, during the record date, Max Roach had a concert. He had to dash off and play a one-hour concert somewhere, so there was a substitute drummer while that was going on, and Max came back. Well, Norman was so impatient with it and had such poor musical equipment that he cancelled us out – right in the middle of the thing – he snapped the thing. He said, OK, that’s all… goodnight.” (2)

Of course, the lack of rehearsal led to the disintegration of a fine project, but just as responsible was the casting error that Hal McKusick denounced: “The voice parts were way too complicated. Gil’s charts were beautiful and complex, as always. His arrangements always could push your buttons, musically. But Dave’s vocal charts were heavy, and by the time everyone realized this, it was too late. The recording session was already underway.” (3) McKusick, by the way, was wondering why the voice parts hadn’t been entrusted to Gil Evans as well; he would have used a mere quartet. The takes that were released, however – composite ones – nevertheless have some beautiful moments, like Parker advancing in the midst of the voices in Old Folks or the introduction of If I Love Again. On the tune In the Still of the Night, Bird takes flight with assistance from voice parts that are rather ordinary in other respects.

When Gil Evans and Dave Lambert listened to the test pressings they noticed that the sound engineer had made a mistake when balancing the sound: the voices were drowning the orchestra, the soloist and the rhythm section. After consulting Parker, they offered to do the session again for free. Granz refused. The result was that what promised to be a rare moment in Parker’s recorded work remains a rough draft.

In June Parker was given another booking at the Hi-Hat in Boston. It was a noisy establishment and, contrary to practice at its competitor, the Storyville, the club paid hardly any attention to providing its customers with the best listening conditions. This time, trumpeter Herb Pomeroy would replace Joe Gordon, who was unavailable. Pomeroy sensibilities, and his taste for melody, had earned him a place in the category reserved for people dear to Bird’s heart, along with trumpeters ranging from Miles Davis to Chet Baker, and including Tony Fruscella and Don Joseph. “I remember working with Charlie Parker for the first time at the Hi-Hat. I probably heard Bird there several different times before I worked with him. The club was upstairs on the second floor, and I can remember walking up the stairs, and my knees were shaking, literally shaking, that I was going to work with Charlie Parker, June of ’53. It was the very month, the very week that I would have graduated if I had stayed at Harvard.” (4) On piano there was Dean Earl, who was at the time in charge of musical interludes at the Hi-Hat; on bass there was Bernie Briggs, a cornerstone of the jazz scene in Boston, as was the drummer, Bill “Baggy” Grant. They made up an efficient, attentive formation and they provided Parker with adequate support for him to exercise his imagination on pieces he’d already played a thousand times, like Cool Blues, Scrapple from the Apple or Ornithology. The only new ones were Laura, previously reserved for the string orchestra, and My Funny Valentine, which Gerry Mulligan and Chet Baker had brought up to date the previous year. It was during the Hi-Hat gig that John McLellan did an interview with Bird, and they listened to some records. Parker expressed his admiration for My Lady, a feature for Lee Konitz with the Kenton orchestra, and he praised the latter for the innovations he’d introduced into jazz. Stan Getz playing Cherokee at the Storyville also garnered praise from Bird.

Exactitude was never Bird’s cardinal virtue. With the beginning of a new quartet session fixed for noon, Parker turned up at a quarter past two. But once he was there he didn’t dither. Forty-five minutes later the mandatory four titles were in the can: Chi-Chi, a composition given to Max Roach by Parker (Roach had recorded it three months earlier), plus Confirmation, the standard I Remember You, and a new version of Now’s The Time.

On April 26th, journalist and sometime concert-promoter Bob Reisner inaugurated the “Jazz Nights” held on Sunday evenings at NYC’s Open Door club in Greenwich Village. Bird was due to appear there. A few recordings deprived of less than average quality were made during his visit in July, and in September he returned in the company of Thelonious Monk, Charles Mingus and Roy Haynes, apparently without leaving any trace on record. But in agreement with George Wein, Parker went back to Storyville in Boston, this time with drummer Kenny Clarke. They both met up with Herb Pomeroy again, plus Sir Charles Thompson, a pianist who’d led a record session with Bird in 1945, and lastly bassist Jimmy Woode. In the course of a set on the only evening that went out as a broadcast, radio station WDHD felt it necessary to interrupt Dancing on the Ceiling in order to give listeners the latest estimates in a local election…

George Wein was playing at Mahogany Hall (located under the Storyville) in the company of Doc Cheatham, Vic Dickenson and Al Drootin, and for the traditional Sunday jam they all came to join Parker. “Nothing could have prepared us for that power. Bird was reinventing the blues, but without stripping away their essence. And his rhythmic drive was enormous; from my perch behind the piano, I could feel him surging ahead on the homestretch like a thoroughbred horse. ‘Royal Garden Blues’ was the only time I played with Bird and the experience is etched in my memory.” (5)

Bird had gone to California for ten days in order to take part in the concert series called “West Coast in Jazz” along with the quartets of Chet Baker and Dave Brubeck. Accompanying Parker were Jimmie Rowles, Carson Smith and Shelly Manne, who were actually Chet’s rhythm section. Delighted at meeting up with Chet again, Parker regularly made a point of bringing him up onstage to play. Various incidents studded the tour, and more than once Bird had to borrow Paul Desmond’s alto saxophone because his own was in hock. All that remains of those concerts is the ten minutes of music taken from a concert they gave at the University of Oregon. Barbados — a theme that Parker would hardly ever pick up again — begins unusually, on a solo from Shelly Manne. Despite the cuts, the fragments of Cool Blues deserve a hearing because of the series of fours exchanged between Bird, Chet and Shelly Manne.

With various bookings in Chicago, Baltimore and Philadelphia behind him, Parker returned to the Hi-Hat in December 1953 and January ‘54. A certain number of radio broadcasts have survived, but they are all afflicted by the approximate sound of the original takes; subsequent copies didn’t make the situation any better, as there were even new cuts. Like the broadcasts that went out from the Royal Roost in 1948-49, these survivors show Bird in action for only a limited amount of time. So much the better or, at least, they show Bird more convincingly let’s say. Contrary to what he did before in the same surroundings (alongside Joe Gordon, Dick Twardzik or Herb Pomeroy), Bird never gets involved in any real dialogue with his new partners Herbie Williams (a trumpeter of limited imagination), Rollins Griffith, Jimmy Woode and Marquis Foster, all of them from the Boston jazz scene. Rarely in top form, Parker lets them express themselves at some length. When his legal wife Doris went to see him at the Hi-Hat, he admitted to her that it was becoming difficult for him to create… In an interview with John McLellan and Paul Desmond, Bird talked about his desire to go back to Paris and study music, and referred to his encounters with Edgar Varèse saying, “He was very nice to me. He’s willing to teach me. He wants to compose something for me.” Unfortunately, the composer left America and returned to France for the first performance of his piece Déserts. (6)

Once the gig at the Hi-Hat was over, Parker went back to join the “Festival of American Jazz” tour (the Stan Kenton Orchestra, Erroll Garner and his trio, June Christy, Dizzy Gillespie and Candido.) Bird was a last-minute replacement for Stan Getz, who’d been indicted on drug charges, and some of the tour’s posters still carried Getz’ name. As the guest of the Kenton orchestra, Parker played three times on a Bill Holman arrangement of My Funny Valentine, a transposition of Night and Day based on Joe Lippman’s score for strings, and Cherokee. The latter was also a last-minute change: Bird didn’t want to play the tune Zoot intended for Zoot Sims. The three recordings that came out of the Civic Auditorium concerts in Portland allowed listeners to hear Bird back at his artistic peak again.

At the end of the tour, Bird caused a scandal at the Tiffany Club (where he was due to appear with the trio led by Joe Rotondi.) The Los Angeles Police Department — the notorious LAPD — suspected him of using illegal substances and Bird was again arraigned. John Edward O’Grady, the incredible chief of the Hollywood drug squad, would write in his memoirs, “I ran Charlie ‘Yardbird’ Parker, the great saxophonist, out of town. I could have nailed him. His arms were covered with track-marks from heroin needles. But he was too old and too drunk, and I decided it wasn’t worth wasting time nailing Parker just so the City of L.A. could pay for his keep.” (7) O’Grady didn’t send Parker anywhere: Bird returned to New York after hearing his daughter Pree had died. He had to borrow 500$ from impresario Billy Shaw to cover the cost of the funeral because of his insoluble money problems. And then the Syndicate gave him a fine due to his behaviour at the Tiffany Club.

The loss of his daughter overwhelmed Parker and, slowly but surely, he began his descent into hell. His outbursts, plus his total unreliability, were leading to fewer and fewer bookings. When the time came to make a quartet recording for the first part of an album devoted to Cole Porter tunes, he was on the way to a session when he bumped into guitarist Jimmy Darr; on a whim, Bird brought him into the studio. I Get a Kick Out of You was stricken with false starts and takes that were either incomplete or unsatisfactory, but somehow two complete versions found their way onto a release. Parker battles with My Heart Belongs to Daddy without any conviction (placing an inappropriate quote from the Woody Woodpecker Song), and he dismantles I’ve Got You Under My Skin but does nothing to reconstruct the tune convincingly. Not feeling at home on Just One Of Those Things, he brutally pulls the plug on his first chorus.

Beginning on August 14, Parker was booked into the Apollo Theatre for a week. Only one photo remains of the big band that accompanied him there, and it shows Benny Harris, Charlie Rouse, Sahib Shihab, Gerry Mulligan and Bennie Green. Mulligan later commented, “He was faltering. I cried. His playing had exuberance at best, at worst a manic velocity, but always a musical control. What was missing was the kind of gentleness he could project.” (8)

Bird was going from one scandal to another. On August 27 at Birdland, radio station WABC aired one set with Bird and a string orchestra: same repertoire, usual performance. Two days later Parker announced East of the Sun and launched into… Dancing in the Dark. Panic in the ranks. After insulting his musicians, Bird fired them on the spot in front of a stunned audience.

Rumour has it that, once he got home, he swallowed a bottle of iodine. Did he really want to end his life? According to Al Cotton, “Charlie had this to say about his attempted suicide with iodine after the Birdland firing incident: ‘I had to go to some extreme to get out of this financial mess I was in. They would find me out of business; they could hang me legally. I could never pay all I owed, but if I was judged insane at the time, I couldn’t be held responsible. So I daubed a few drops of iodine on my lips and tongue, put a little soapsuds in my mouth, did a lot of play-acting, and I was committed as a mentally unadjusted person who could not be held responsible legally.’” (9) Was it a confession or was he just being boastful? He was taken to Bellevue Hospital and quickly released, only to return some three weeks later, this time on his own initiative to try and stay sober. In the interval he’d paid a visit to Carnegie Hall for a concert by the “Birdland All Stars of ’54”. Accompanied by three-quarters of the Modern Jazz Quartet, Bird put in a brief appearance that, while adding nothing to his prestige, did nothing to detract from it either.

In the sincere belief that he was going to leave his problems behind, Bird decided to move to the country and went with Chan to New Hope. In the wings at Town Hall, he talked to Leonard Feather about this new start. Alas, it wouldn’t be long before he left Chan for a down-and-out existence in New York without even a saxophone to his name. To join Al Levitt and his trio at Arthur’s Tavern, Bird borrowed Jackie McLean’s alto, Brew Moore’s tenor, or even the clarinet belonging to Sol Yaged. Once, when Phil Woods was playing in a band at a strip-show — non-stop versions of Harlem Nocturne — he found Bird struggling with a baritone belonging to painter Larry Rivers. So Woods lent him his own alto and, he said, Bird showed him that Bird could play like Bird to the very end.

On December 2nd Parker was due to finish his Cole Porter album and, in an excellent mood, he arrived at the studio early for once, no doubt hoping to bump into Lester Young who was inside recording before Bird’s session. According to Billy Bauer, who was replacing Jimmy Darr to advantage, “I think Parker was using the early takes as a rehearsal, a musical explanation of what he wanted, and at those unsteady moments he’s leading us and teaching us. After he was satisfied with Love for Sale, he explained I Love Paris to us because he had something in mind as to how he wanted it presented.” (10) It had nothing in common with the previous session.

Leonard Feather: “I saw him once more in the audience at Basin Street. He came over to our table, knelt down beside me and stayed at least ten minutes in that position of prostration, refusing to take a seat and looking for nothing other than attention from someone he considered a friend. That was when I realized that Charlie Parker wanted to die.” (11)

On March 4th 1955 Birdland’s management decided to give Bird another chance. The bill announced, “For one night only, as an addition to the program: Charlie Parker, Bud Powell, Charlie Mingus, Art Blakey and Kenny Dorham.” French jazzman Marcel Zanini remembers that, “Charlie Parker came on (Kenny Dorham was already onstage), then Mingus, who tuned his bass, and Bud Powell, who seemed totally absent. He was sitting at his piano but not touching it… everything was happening amidst a general indifference. There were a lot of people because it was a Saturday. But nobody was taking an interest in what was happening onstage. Parker called out a title to Bud Powell, who played the introduction to Little Willie Leaps and then stopped. Mingus laid his bass on the floor. Parker saw him leave and, still playing with one hand, grabbed him and indicated that he should carry on playing. At that point, Blakey came in and sat down behind his kit. Finally, Bud Powell turned to the audience with his back to the piano, his elbows resting on the keyboard; his eyes had an ‘out of this world’ look. A drama was playing out. The audience still didn’t care. Parker, Mingus and Blakey played on their own. They played the blues. And the volume… it was crazy. I just took some photos…” (12) Nat Hentoff would add that Bud Powell and Parker were hurling insults at each other and that when the pianist quit, Bird leaned on the microphone for a long while, chanting the name of Bud Powell. It was then that Mingus dissociated himself from his partners, announcing over the microphone, “These are sick people…”

George Wein: “History was made the next time I booked Charlie Parker for his third Storyville appearance. It was to be a weekend affair, beginning on March 9, 1955 […] It wasn’t unusual for him to blow off a commitment without warning or excuse. So, when the first night of Bird’s Storyville gig arrived, but with no Bird, I was annoyed. We had a roomful of patrons, a rhythm section, and an absentee attraction. Well, I thought to myself resignedly, ‘Bird goofed again.’” (13)

The day before, Parker was getting ready to go to Boston and he stopped off at the Stanhope Hotel to see his friend Nica (Baroness Pannonica de Kœnigswarter, a patron of the arts and a friend to many musicians). (14) Parker complained of stomach pains but refused to go into hospital. His host Nica called a doctor who, when he questioned Bird about his drinking habits, drew the following reply, “Well, Doc, just an occasional glass of sherry before dinner…” Nica decided that Bird should stay with her until he recovered. On the 12th, the Tommy Dorsey Show was playing on the television and Parker, an admirer of the musician, sat down in front of the TV to watch. A comedy routine by acrobats made him laugh so much that it proved fatal. The doctor they summoned gave the reason of death as pneumonia, stating that he was examining the body of a man aged around fifty-three. Bird was thirty-five. His body was taken to Bellevue Hospital anonymously because Nica de Kœnigswarter, not knowing where Chan lived, didn’t want her to learn of Bird’s death from the newspapers… That didn’t prevent the “New York Mirror” from going to press with the headline, “Bop King Dies in Heiress Flat.”

A funeral service was held at New York Abyssinian Baptist Church and on April 2nd, from midnight until three in the morning, a concert took place at Carnegie Hall in Bird’s memory. Among those who played were Lester Young, Thelonious Monk, Horace Silver, Kenny Dorham, Art Blakey, Kenny Clarke, Oscar Pettiford, Gerry Mulligan, Dizzy Gillespie, Mary Lou Williams, Billie Holiday, Stan Getz, Sammy Davis Jr. and… Charles Mingus, among others. There was also an imbroglio of a family nature: Parker’s matrimonial situation was particularly ambiguous and, according to Chan, it was against his own will but in keeping with his mother’s wishes that Bird was buried in Kansas City.

On March 27th 1999, “Charlie Parker Memorial Plaza” was inaugurated close to the American Jazz Museum. A monumental plinth bearing a bronze head of Parker measuring nearly fourteen feet high, it was the work of sculptor Robert Graham and it carried only one sentence: “Bird Lives.” It was self-evident, and over the years, that statement has gone beyond the narrow limits of the world of jazz. As early as 1964, a former graphic-arts-student-turned-drummer with the Rolling Stones, Charlie Watts, drafted and designed “Ode to a Flying Bird”, a children’s album dedicated to Charlie Parker that told the story of a saxophone-playing bird who was a genius.

In 1988, Clint Eastwood made the film “Bird” in which Forest Whitaker incarnated Parker, thereby introducing Bird to thousands who had never heard of him before. “Bird Lives!” would even be the title of a play by Willard Manus that was staged in 2014 at the Chromolume Theater at the Attic in Los Angeles. The following year, in June, the Philadelphia Opera staged “Yardbird”, a one-act opera for fifteen participants composed by Daniel Schnyder. Not to mention the countless tributes — some of them surprising — that have been paid to Parker by his peers. And today, sixty years later, the entirety of his legacy still doesn’t seem to have been exhausted.

Adapted by Martin Davies

from the French Text of Alain Tercinet

© 2017 Frémeaux & Associés

(1) Nat Hentoff, “Counterpoint”, Down Beat, January 20, 1953.

(2) Ken Vail, “Bird’s Diary”, Chessington, Castle Communications, 1995.

(3) Hal McKusick, “Charlie Parker and Voices, Part 1”, JazzWax, Internet.

(4) Richard Vacca, “The Boston Jazz Chronicles”, Troy Street Publishing, LLC, Belmont, Massachusetts, 2012.

(5) George Wein with Nate Chinen, “Myself Among Others – A Life in Music”, Da Capo Press, 2003.

(6) In 1957, Edgar Varèse took an interest in the jam sessions organized by Teo Macero and composer Earl Brown. In them participated Art Farmer, Hal McKusick, Hall Overton and Charles Mingus, and recordings allow you to hear Varèse talking with the musicians.

(7) John O’Grady & Nolan Davis, “O’Grady: the Life and Times of Hollywood’s N°1 Private Eye”, J. P. Tarcher Inc., Los Angeles, 1974.

(8) Gary Giddins, “Celebrating Bird – The Triumph of Charlie Parker”, revised edition, University of Minnesota Press, 2013.

(9) Robert Reisner, “Bird, The Legend of Charlie Parker”, Da Capo Press, 1977.

(10) Cf. booklet, “The Complete Charlie Parker on Verve”.

(11) Leonard Feather, “Charlie Parker intime”, Jazz Hot N°261, May 1970.

(12) Alex Dutilh, “New York, 1954-58, Marcel Zanini se souvient”, Jazz Hot N° 328, June 1976.

(13) Cf. (5)

(14) Baroness Pannonica “Nica” de Kœnigswarter (1913-1988) was related to the Rothschild family. She was the wife of an Ambassador, an ambulance attendant in the Free French Forces in Africa, and she devoted part of her fortune to aiding Afro-American jazz musicians in difficulty. At her home in Weehawken, she provided Thelonious Monk with a roof during his final years. A book conceived by her granddaughter Nadine de Koenigswarter (based on Polaroid photographs that Nica had taken at her house) constitutes an exceptional document. Cf. “Three Wishes – An Intimate Look at Jazz Greats,” by Pannonica de Kœnigswarter, publ. Harry N. Abrams Inc., NYC, 2008.

DISCOGRAPHICAL NOTES

BIRD AT THE HI-HAT

The composition and the dates of these performances by Charlie Parker broadcast over radio from the Hi-Hat Club in Boston can vary, depending on the discography consulted. The order in which they are compiled here does not pretend to be definitive.

Ornithology / Out of Nowhere / My Funny Valentine / Cool Blues (Hi-Hat, June 1953).

These four performances preserved without announcements have been wrongly dated at January 18th 1954. The presence of Herb Pomeroy on trumpet puts them at between June 8 and June 14, 1953, because Herb was away from Boston on tour in January 1954. The presence of Dean Earle on piano is obvious, but it is more difficult to precisely identify the bassist and drummer.

Cheryl / Ornithology / 52nd Street Theme (Hi-Hat, December 18th and 20th 1953).

Some releases mistakenly attach these three pieces to the radio broadcast dated June 14th 1953, whereas the trumpeter is Herbie Williams, not Herb Pomeroy, and the pianist is not Dean Earle. In addition, Bird’s quote from Santa Claus is Coming to Town during his solo on Ornithology makes it more likely that they date from December. In the second version of Ornithology, during the solo from Rollins Griffith, every copy of the record contains a groove jump.

Hi-Hat (January 24, 1954)

Also played was a version of My Little Suede Shoes. In all copies of the recording, the statement of the theme and the essential part of Parker’s improvisation are missing. It is for that reason that this piece has not been included here.

discographie - CD 1

CHARLIE PARKER AND HIS ORCHESTRA

Charlie Parker (as) with Junior Collins (frh) ; Al Block (fl) ; Hal McKusick (cl) ; Tommy Mace (oboe) ; Manny Thaler (bassoon); Tony Aless (p) ; Charles Mingus (b) ; Max Roach (dm) ; Dave Lambert Singers (voc) ; Dave Lambert (arr-voc) ; Gil Evans (arr, cond). NYC, 25/5/1953

1. IN THE STILL OF THE NIGHT (C. Porter) (Clef 11100/mx. 1238-7) 3’25

2. OLD FOLKS (W. Robinson, D. Lee Hill) (Clef 11100/mx. 1239-9) 3’35

3. IF I LOVE AGAIN (B. Oakland, J. P. Murray) (Verve MGV80091240-9) 2’27

CHARLIE PARKER AND HIS ALL-STARS

Herb Pomeroy (tp) ; Charlie Parker (as), Dean Earle (p) ; Bernie Griggs (b) ; Bill Grant (dm) ; Symphony Sid (mc).

WCOP Radio Hi-Hat Club, Boston 14/6/1953

4. Announcement (Radio Transcription) 0’39

5. COOL BLUES (C. Parker) (Radio Transcription) 5’36

6. Announcement (Radio Transcription) 0’10

7. SCRAPPLE FROM THE APPLE (C. Parker) (Radio Transcription) 7’02

8. Announcement (Radio Transcription) 0’57

9. LAURA (D. Raskin, J. Mercer) (Radio Transcription) 6’33

10. Closing Announcement (Radio Transcription) 0’31

CHARLIE PARKER AND HIS ALL-STARS

Herb Pomeroy (tp) ; Charlie Parker (as), Dean Earle (p) ; poss. Bernie Griggs (b) ; poss. Bill Grant (dm).

WCOP Radio Hi-Hat Club, Boston between June 8 – 14 1953

11. ORNITHOLOGY (C. Parker, B. Harris) (Radio Transcription) 4’59

12. OUT OF NOWHERE (J. Green, E. Hayman) (Radio Transcription) 5’43

13. MY FUNNY VALENTINE (R. Rogers, L. Hart) (Radio Transcription) 6’35

14. COOL BLUES (C. Parker) (Radio Transcription) 6’49

CHARLIE PARKER QUARTET

Charlie Parker (as) ; Al Haig (p) ; Percy Heath (b) ; Max Roach (dm). NYC, 30/7/1953

15. CHI-CHI (C. Parker) (Verve MGV 8005/mx. 1246-1) 3’06

16. CHI-CHI (C. Parker) (Verve MGV 8005/mx. 1246-3) 2’43

17. CHI-CHI (C. Parker) (master) (Clef 89138/mx. 1246-6) 3’03

18. I REMEMBER YOU (V. Schertzinger, J. Mercer) (Clef 89138/mx. 1247-3) 3’03

19. NOW’S THE TIME (C. Parker) (Clef MGC 517/mx. 1248-1) 3’01

20. CONFIRMATION (C. Parker) (Clef MGC 517/mx. 1249-3) 2’57

discographie - CD 2

CHARLIE PARKER AND HIS ALL-STARS

Herb Pomeroy (tp) ; Charlie Parker (as) ; Sir Charles Thompson (p) ; Jimmy Woode (b) ; Kenny Clarke (dm) ; John McLellan (mc). WDHD Radio, Storyville Club, Boston, 22/9/1953

1. NOW’S THE TIME (C. Parker) (Radio Transcription) 4’17

2. DON’T BLAME ME (J. McHugh, D. Fields) (Radio Transcription) 4’59

3. DANCING IN THE CEILING (R. Rodgers, L. Hartz) (Radio Transcription) 2’29

4. COOL BLUES (C. Parker) (Radio Transcription) 4’49

5. GROOVIN’ HIGH (D. Gillespie) (Radio Transcription) 5’06

CHARLIE PARKER AND HIS ALL-STARS

Chet Baker (tp) ; Charlie Parker (as) ; Jimmie Rowles (p) ; Carson Smith (b) ; Shelly Manne (dm).

University of Oregon, Portland, 5/11/1953

6. ORNITHOLOGY (C. Parker, B. Harris) (inc.) (Private recording ?) 2’53

7. BARBADOS (C. Parker) (inc.) (Private recording ?) 4’03

8. COOL BLUES (C. Parker) (inc.) (Private recording ?) 5’39

CHARLIE PARKER AND HIS ALL-STARS

Herbie Williams (tp) ; Charlie Parker (as) ; Rollins Griffith (p) ; Jimmy Woode (b) ; Marquis Foster (dm).

WCOP/WBMS radio broadcast, Hi-Hat Club, Boston, Mass., 18 & 20 /12/1953

9. Announcement (Radio Transcription) 0’14

10. ORNITHOLOGY (C. Parker, B. Harris) (Radio Transcription) 7’51

11. Introduction (Radio Transcription) 0’28

12. MY LITTLE SUEDE SHOES (C. Parker) (Radio Transcription) 7’16

13. Introduction (Radio Transcription) 0’29

14. NOW’S THE TIME (C.Parker) (Radio Transcription) 7’04

15. GROOVIN’HIGH (C. Parker, D.Gillespie) (Radio Transcription) 6’08

16. Announcement (Radio Transcription) 0’21

17. CHERYL (C. Parker) (Radio Transcription) 5’47

18. Introduction (Radio Transcription) 0’04

19. ORNITHOLOGY (C. Parker, B. Harris) (Radio Transcription) 6’29

20. 52nd STREET THEME (T. Monk) (Radio Transcription) 1’32

discographie - CD 3

CHARLIE PARKER AND HIS ALL-STARS

Herbie Williams (tp) ; Charlie Parker (as) ; Rollins Griffith (p) ; Jimmy Woode (b) ; Marquis Foster (dm)

WCOP radio broadcast, Hi-Hat Club, Boston, Mass., 18 /1/1954

1. Announcement (Radio Transcription) 0’21

2. ORNITHOLOGY (C. Parker, B. Harris) (Radio Transcription) 6’47

3. Announcement (Radio Transcription) 0’19

4. OUT OF NOWHERE (J. Green, E. Hayman) (Radio Transcription) 9’32

5. Announcement (Radio Transcription) 0’32

6. COOL BLUES (C. Parker) (Radio Transcription) 6’52

7. Announcement (Radio Transcription) 0’45

8. SCRAPPLE FROM THE APPLE (C. Parker) (Radio Transcription) 4’34

CHARLIE PARKER AND HIS ALL-STARS

Herbie Williams (tp) ; Charlie Parker (as) ; Jay Migliori (ts) ; Rollins Griffith (p) ; Jimmy Woode (b) ; George Solano (dm) ; Symphony Sid Torin(mc). WCOP/WBMS radio broadcast, Hi-Hat Club, Boston, Mass., 23/1/1954

9. NOW’S THE TIME (C. Parker) (Radio Transcription) 9’12

10. Announcement (Radio Transcription) 0’33

11. OUT OF NOWHERE (J. Green, E. Hayman) (Radio Transcription) 5’43

12. MY LITTLE SUEDE SHOES (C. Parker) (Radio Transcription) 5’05

13. JUMPIN’ WITH SYMPHONY SID (L. Young) (Radio Transcription) 1’08

CHARLIE PARKER AND HIS ALL-STARS

Migliori out, Marquis Foster (dm) Same place, 24/1/1954

14. COOL BLUES (C. Parker) (Radio Transcription) 6’20

15. Announcement (Radio Transcription) 1’02

16. ORNITHOLOGY (C. Parker, B. Harris) (Radio Transcription) 7’35

17. Announcement (Radio Transcription) 1’22

18. OUT OF NOWHERE (J. Green, E. Hayman) (Radio Transcription) 4’22

19. JUMPIN’ WITH SYMPHONY SID (L. Young) (Radio Transcription) 2’34

discographie - CD 4

CHARLIE PARKER with STAN KENTON AND HIS ORCHESTRA

Charlie Parker (as) with Sam Noto, Vic Minichelli, Buddy Childers, Stu Williamson, Don Smith (tp) ; Milt Gold, Joe Ciavardone, Frank Rosolino, George Roberts (tb) ; Charlie Mariano, Dave Schildkraut (as) ; Mike Cichetti, Bill Perkins (ts) ; Tony Ferina (bs) ; Stan Kenton (p) ; Bob Lesher (g) ; Don Bagley (b) ; Stan Levey (dm) ; Joe Lippman*, Bill Holman** (arr).

Civic Auditorium, Portland, OR, 25/2/1954

1. NIGHT AND DAY* (C. Porter) (Private Recording) 3’01

2. MY FUNNY VALENTINE** (R. Rodgers, L. Hart) (Private Recording) 3’18

3. CHEROKEE** (R. Noble) (Private Recording) 2’56

CHARLIE PARKER QUINTET

Charlie Parker (as) ; Walter Bishop (p) ; Jerome Darr (g)* ; Teddy Kotick (b) ; Roy Haynes (dm). NYC, 31/3/1954

4. I GET A KICK OUT OF YOU (C. Porter) (Verve MGV 8007/mx. 1531-1) 4’51

5. I GET A KICK OUT OF YOU* (C. Porter) (Verve MGV 8007/mx. 1531-7) 3’33

6. JUST ONE OF THOSE THINGS* (C. Porter) (Verve MGV 8007/mx. 1532-1) 2’41

7. MY HEART BELONGS TO DADDY* (C. Porter) (Verve MGV 8007/mx. 1533-2) 3’19

8. I’VE GOT YOU UNDER MY SKIN (C. Porter) (Verve MGV 8007/mx. 1534-1) 3’32

CHARLIE PARKER AND STRINGS

Charlie Parker (as) unknown oboe and strings ; Walter Bishop (p) ; Teddy Kotick or Tommy Potter (b) ; Roy Haynes (dm).

WBC Radio Broadcast, Birdland, NYC, 27/8/1954

9. WHAT IS THIS THING CALLED LOVE ? (C. Porter) (Radio Transcription) 2’14

10. REPETITION (N. Hefti) (Radio Transcription) 2’42

11. EASY TO LOVE (C. Porter) (Radio Transcription) 2’11

12. EAST OF THE SUN (B. Bowman) (Radio Transcription) 3’40

CHARLIE PARKER QUARTET

Charlie Parker (as) ; John Lewis (p) ; Percy Heath (b) ; Kenny Clarke (dm). Carnegie Hall, NYC, 25/9/1954

13. THE SONG IS YOU (J.Kern, O. Hammerstein II) (Roulette RE 127) 4’41

14. MY FUNNY VALENTINE (R. Rodgers, L. Hart) (Roulette RE 127) 2’02

15. COOL BLUES (C. Parker) (Roulette RE 127) 2’58

CHARLIE PARKER QUINTET

Charlie Parker (as) ; Walter Bishop (p) ; Billy Bauer (g) ; Teddy Kotick (b) ; Art Taylor (dm). NYC, 10/12/1954

16. LOVE FOR SALE (C. Porter) (Verve MGV 8007/mx. 2115-4) 5’29

17. LOVE FOR SALE (C. Porter) (master) (Verve MGV 8001/mx. 2115-5) 5’31

18. I LOVE PARIS (C. Porter) (Verve MGV 8007/mx. 2116-2) 5’05

19. I LOVE PARIS (C. Porter) (master) (Verve MGV 8001/mx. 2116-3) 5’07

Les étoiles * relient la présence ponctuelle d’un musicien ou d’un orchestre dans un ou plusieurs morceaux d’une séance

« Bird jette son génie par les fenêtres. Et puis un jour son instrument. Et puis un autre jour, l’instrument de cet instrument ; cet homme plein de candeur et d’énigme qui parlait aux oiseaux. »

Alain Gerber

“Bird would throw his genius out of every window. And then one day, his instrument. And then on another day, the instrument of that instrument, this man full of candour and enigma who talked to the birds.”

Alain Gerber

CD 1 : CHARLIE PARKER AND HIS ORCHESTRA - NYC, 25/5/1953 : 1. IN THE STILL OF THE NIGHT 3’25 • 2. OLD FOLKS 3’35 • 3. IF I LOVE AGAIN 2’27 • CHARLIE PARKER AND HIS ALL-STARS - WCOP Radio Hi-Hat Club, Boston 14/6/1953 : 4. Announcement 0’39 • 5. COOL BLUES 5’36 • 6. Announcement 0’10 • 7. SCRAPPLE FROM THE APPLE 7’02 • 8. Announcement 0’57 • 9. LAURA 6’33 • 10. Closing Announcement 0’31 • CHARLIE PARKER AND HIS ALL-STARS - WCOP Radio Hi-Hat Club, Boston June 1953 : 11. ORNITHOLOGY 4’59 • 12. OUT OF NOWHERE 5’43 • 13. MY FUNNY VALENTINE 6’35 • 14. COOL BLUES 6’49 • CHARLIE PARKER QUARTET - NYC, 30/7/1953: 15. CHI-CHI 3’06 • 16. CHI-CHI 2’43 • 17. CHI-CHI 3’03 • 18. I REMEMBER YOU 3’03 • 19. NOW’S THE TIME 3’01 • 20. CONFIRMATION 2’57.

CD 2 : CHARLIE PARKER AND HIS ALL-STARS - WDHD Radio, Storyville Club, Boston, 22/9/1953 : 1. NOW’S THE TIME 4’17 •

2. DON’T BLAME ME 4’59 • 3. DANCING IN THE CEILING 2’29 • 4. COOL BLUES 4’49 • 5. GROOVIN’ HIGH 5’06 • CHARLIE PARKER AND HIS ALL-STARS - University of Oregon, Portland, 5/11/1953 : 6. ORNITHOLOGY 2’53 • 7. BARBADOS 4’03 • 8. COOL BLUES 5’39 • CHARLIE PARKER AND HIS ALL-STARS - WCOP/WBMS radio broadcast, Hi-Hat Club, Boston, Mass., 19 - 20 /12/1954 :

9. Announcement 0’14 • 10. ORNITHOLOGY 7’51 • 11. Introduction 0’28 • 12. MY LITTLE SUEDE SHOES 7’16 • 13. Introduction 0’29 • 14. NOW’S THE TIME 7’04 • 15. GROOVIN’HIGH 6’08 • 16. Announcement 0’21 • 17. CHERYL 5’47 • 18. Introduction 0’04 • 19. ORNITHOLOGY 6’29 • 20. 52nd STREET THEME 1’32.

CD 3 : CHARLIE PARKER AND HIS ALL-STARS - WCOP radio broadcast, Hi-Hat Club, Boston, Mass., 18 /1/1954 : 1. Announcement 0’21 • 2. ORNITHOLOGY 6’47 • 3. Announcement 0’19 • 4. OUT OF NOWHERE 9’32 • 5. Announcement 0’32 • 6. COOL BLUES 6’52 • 7. Announcement 0’45 • 8. SCRAPPLE FROM THE APPLE 4’34 • CHARLIE PARKER AND HIS ALL-STARS - WCOP/WBMS radio broadcast, Hi-Hat Club, Boston, Mass., 23/1/1954 : 9. NOW’S THE TIME 9’10 • 10. Announcement 0’49 • 11. OUT OF NOWHERE 5’43 • 12. MY LITTLE SUEDE SHOES 5’05 • 13. JUMPIN’ WITH SYMPHONY SID 1’08 • CHARLIE PARKER AND HIS ALL-STARS - Same place, 24/1/1954 : 14. COOL BLUES 6’20 • 15. Announcement 1’02 • 16. ORNITHOLOGY 7’35 • 17. Announcement 1’22 • 18. OUT OF NOWHERE 4’22 •

19. JUMPIN’ WITH SYMPHONY SID 2’34.

CD 4 • CHARLIE PARKER with STAN KENTON AND HIS ORCHESTRA - Civic Auditorium, Portland, OR, 25/2/1954 : 1. NIGHT AND DAY 3’01 • 2. MY FUNNY VALENTINE 3’18 • 3. CHEROKEE 2’56 • CHARLIE PARKER QUINTET - NYC, 31/3/1954 : 4. I GET A KICK OUT OF YOU 4’51 • 5. I GET A KICK OUT OF YOU 3’33 • 6. JUST ONE OF THOSE THINGS 2’41 • 7. MY HEART BELONGS TO DADDY 3’19 •

8. I’VE GOT YOU UNDER MY SKIN 3’32 • CHARLIE PARKER AND STRINGS - Birdland, NYC, 27/8/1954 : 9. WHAT IS THIS THING CALLED LOVE ? 2’14 • 10. REPETITION 2’42 • 11. EASY TO LOVE 2’11 • 12. EAST OF THE SUN 3’40 • CHARLIE PARKER QUARTET - Carnegie Hall, NYC, 25/9/1954 : 13. THE SONG IS YOU 4’41 • 14. MY FUNNY VALENTINE 2’02 • 15. COOL BLUES 2’58 • CHARLIE PARKER QUINTET - NYC, 10/12/1954 : 16. LOVE FOR SALE 5’29 • 17. LOVE FOR SALE 5’31 • 18. I LOVE PARIS 5’05 • 19. I LOVE PARIS 5’07.

L’intégrale Charlie Parker, réalisée par Alain Tercinet pour Frémeaux & Associés a pour mission de présenter la quasi-intégralité des titres gravées en studio ainsi que des oeuvres diffusées sur les ondes. Des enregistrements privés ont été écartés de la sélection pour respecter une cohérence sonore et un niveau de qualité esthétique à la hauteur du génie de Charlie Parker.

The aim of ’The Complete Charlie Parker’, compiled for Frémeaux & Associés by Alain Tercinet, is to present (as far as possible) every studio-recording by Parker, together with titles featured in radio-broadcasts. Private recordings have been deliberately omitted from this selection to preserve a consistency of sound and aesthetic quality equal to the genius of this artist.